Elections in many contemporary Latin American democracies unfold in a setting that complicates traditional political communication strategies. Indeed, many of the region’s democracies are characterized by weak political parties, high levels of institutional distrust, and growing disdain for political elites (Barozet et al. Reference Barozet, Contreras, Espinoza, Gayo and Luisa Méndez2021; González and Le Foulon Morán Reference González and Le Foulon Morán2020; Heiss and Suárez-Cao Reference Heiss and Suárez-Cao2024; Luna and Altman Reference Luna and Altman2011; Luna Reference Luna2014; Meléndez Reference Meléndez2022; Somma et al. Reference Somma, Bargsted, Pavlic and Medel2021; Disi Pavlic Reference Disi Pavlic2018). How do campaign teams seek to win over voters when they cannot rely on partisan appeals? What is the focus of political messages when large swaths of the electorate are unsatisfied with democracy? While a large body of literature has sought to explain which factors weaken parties and increase institutional distrust, less attention has been paid to the question of how these characteristics shape political communication strategies (Castro Cornejo Reference Castro Cornejo2021a, Reference Castro Cornejo2021b; Boas & Daniel Hidalgo, Reference Boas and Daniel Hidalgo2011; Greene Reference Greene2011; Lupu et al. Reference Lupu, Oliveiros and Schiumerini2019; Muñoz Reference Muñoz2018; Pallister Reference Pallister2021). Moreover, what literature does exist is focused on candidate-centered elections, with less work exploring referenda and plebiscite votes.Footnote 1 In this article, we seek to fill these holes in the literature, focusing on Chile’s 2020, 2022, and 2023 constitutional plebiscite campaigns to examine political communication in a setting of weak parties and low institutional trust.

Drawing on the content of television advertisements created for Chile’s constitutional plebiscite campaigns and original interviews with the creative and political teams that designed the ads, we explore how each side communicated with voters; which issues they focused on; and to what extent they relied on partisan, policy, generic, or emotional appeals. The analysis identifies important changes in messaging across the three different electoral contests and probes an explanation for this variation across time. We find that in the absence of partisan messages, the constitutional campaigns relied first on policy-based appeals but then transitioned to generic appeals.

Specifically, during the first plebiscite, in which voting was voluntary and the electorate was made up of mostly politically engaged citizens, campaign messaging focused on policy-based appeals. Once voting was made mandatory and the electorate expanded, high levels of alienation and frustration with the constitutional process drove the campaign teams to focus on generic appeals, ultimately settling on an antipolitics message. The results of our analysis, therefore, point to a troubling dynamic: Campaigns conducted in settings of weak and discredited democratic institutions may further deepen frustration and alienation, thereby entrenching a cycle of democratic discontent. The article also sheds light on the peculiarities of constitutional referenda and the use of emotional language in those settings. Specifically, we find that the use of emotional language varied across sectors, with the campaign that sought to defend the status quo using negative emotional language.

Do campaigns matter? The role of emotion and context

Research on election campaigns has focused on the extent to which campaigns influence outcomes (Boas Reference Boas2015; Pallister Reference Pallister2024) and the psychology of campaign communication (Crabtree et al. Reference Crabtree, Golder, Gschwend and Indriđason2020; Ridout and Searles Reference Ridout and Searles2011). Early research on these questions focused almost exclusively on how the processes worked in established democracies (Lupu et al. Reference Lupu, Oliveiros and Schiumerini2019). Following the third wave of democracy, research has incorporated a wider range of cases, highlighting the ways that cross-national differences, such as party system strength and weakness, institutional instability, and levels of development may shape the content and importance of campaigns (Aguilar and Conroy-Krutz Reference Aguilar, Conroy-Krutz, Suhay, Grofman and Alexander2020; Boas and Hidalgo Reference Boas and Daniel Hidalgo2011; Greene Reference Greene2011, Reference Greene2019; Castro Cornejo Reference Castro Cornejo2021b, Reference Castro Cornejo2021a).

The impact and importance of campaigns

Much of the early research on voting behavior focused on US elections (Campbell et al. Reference Campbell, Converse, Miller and Stokes1980). These studies identified a hierarchy of considerations that shape vote choice, including belonging to an identity group, partisanship, and policy positions. Specifically, scholars found that belonging to an identity group and partisanship were highly predictive of vote choice (Campbell et al. Reference Campbell, Converse, Miller and Stokes1980). Because of the strength of partisan identity, much of the research on US politics concluded that campaigns have only a marginal impact on election outcomes (Lazarsfeld et al. Reference Lazarsfeld, Berelson and Gaudet1944; Zaller Reference Zaller1992).

For voters with weak ties to parties, issue voting—choosing a candidate on the basis of policy positions—may better explain vote choice. Torre (Reference Torre2003), however, finds that Latin American voters who are wholly unattached to parties are more likely to rely on valence issues than policy positions when voting. Valence issues are topics that are uniformly liked or disliked by society. Prime examples are economic growth and citizen security. In a study of Guatemala, Pallister (Reference Pallister2021) identifies another type of campaign message, which he calls “generic appeals”—broad statements that any voter would agree with but that are too vague to be tied to a policy or even a valence issue.

Partisanship is weak in many Latin American democracies (Luna Reference Luna2014; Morgan Reference Morgan2011; Mainwaring and Scully Reference Mainwaring and Scully1995; Luna and Altman Reference Luna and Altman2011; Lupu Reference Lupu2014). As a result, a growing number of voters in the region are “unattached,” making elections volatile and intensely contested (Muñoz Reference Muñoz2018). In these settings, studies show that election outcomes hinge on valence issues, clientelism (Calvo and Murillo Reference Calvo and Victoria Murillo2004; Stokes et al. Reference Stokes, Dunning and Nazareno2013), postpartisan identities (Meléndez Reference Meléndez2022), and generic appeals (Pallister Reference Pallister2021).Footnote 2 In summary, a survey of the literature identifies at least four types of campaign messages that might be adopted in different types of settings. The first is rooted in partisanship, the second in policy, the third in broader valence issues, and the fourth in generic appeals.

Use of emotion in campaign advertising

Another research area that has received a great deal of scholarly attention is the use of emotion in campaigns (Groenendyk Reference Groenendyk2016; Ridout and Searles Reference Ridout and Searles2011; Zomeren Reference Zomeren2021; Yates Reference Yates, Heather and Palgrave Macmillan2016). Marcus et al. (Reference Marcus and MacKuen1993) present a theory of affective intelligence to explain how voters use emotion to manage political decision-making. Drawing on psychological research, the authors suggest that humans have two emotional systems: dispositional and surveillance. Feelings of enthusiasm and aversion guide the dispositional system. The surveillance system relies instead on anxiety, fear, and/or uncertainty. When the surveillance system is activated, the brain realizes that conscious attention is required. As a result, the authors show that when the surveillance system is activated, voters reduce their reliance on habitual practices (i.e., voting based on partisanship) and pay greater attention to policy and candidate traits. By contrast, when the disposition system is activated, voters rely on routine behavior, namely partisan cues (Marcus et al. Reference Marcus, Russell Neuman and MacKuen2000). Brader (Reference Brader2006, 182) extends this work, demonstrating that emotional appeals that elicit fear and anxiety make voters less likely to rely on prior beliefs and more likely to pay attention to news coverage.Footnote 3

While much of the literature on campaign ads and emotion is focused on traditional candidate- or party-centered elections, a handful of articles have considered the role of emotion in referenda (Black et al. Reference Black, Baines, Baines, O’Shaughnessy and Mortimore2023; Boukala and Dimitrakopoulou Reference Boukala and Dimitrakopoulou2017; Moss et al. Reference Moss, Robinson and Watts2020; Vasilopoulou and Wagner Reference Vasilopoulou and Wagner2017), highlighting the role of hope and fear in such elections. Black et al. (Reference Black, Baines, Baines, O’Shaughnessy and Mortimore2023) analyze the Scottish independence referendum, showing that campaigns focused on maintaining the status quo tend to deploy fear, whereas those that seek to persuade voters to embrace change rely on hope. In the case of Brexit, Vasilopoulou and Wagner (Reference Vasilopoulou and Wagner2017) show that the “remain” campaign used fear and anxiety, whereas the “leave” campaign deployed anger.

Political context and hypotheses

In 2019, Chileans took to the streets in massive numbers to express discontent with the country’s political system and the neoliberal economic model. Analyses of the “social explosion,” as it came to be known, reveal that protesters were motivated by a variety of concerns, including inequality, strained social services, meager pensions, discredited political parties, and distrust in political institutions (Barozet et al. Reference Barozet, Contreras, Espinoza, Gayo and Luisa Méndez2021; González and Le Foulon Morán Reference González and Le Foulon Morán2020; Jiménez-Yañez Reference Jiménez-Yañez2020; Luna Reference Luna2021; Palacios-Valladares Reference Palacios-Valladares2020; Rhodes-Purdy and Rosenblatt Reference Rhodes-Purdy and Rosenblatt2023; Sehnbruch and Donoso Reference Donoso and Sehnbruch2020; Somma et al. Reference Somma, Bargsted, Pavlic and Medel2021). The uprising lasted for nearly a month and slowed only after elites brokered the “agreement for social peace,” a pact that outlined a pathway for rewriting the constitution (Democracia Cristiana et al. Reference Democracia, Democrática, Nacional, Comunes, por la Democracia and Liberal2019).

The agreement for social peace called for a plebiscite vote to decide whether a majority of Chileans wished to rewrite the constitution. The pact also called for a ratification plebiscite to approve or reject the draft constitution. On October 25, 2020, 78 percent of voters opted to rewrite the constitution. The convention was seated in July 2021 and produced a draft constitution one year later, but in September 2022, voters rejected the draft.Footnote 4 Following months of negotiations, the country embarked on a second attempt to rewrite the constitution in March 2023, but that draft was also voted down later that year.

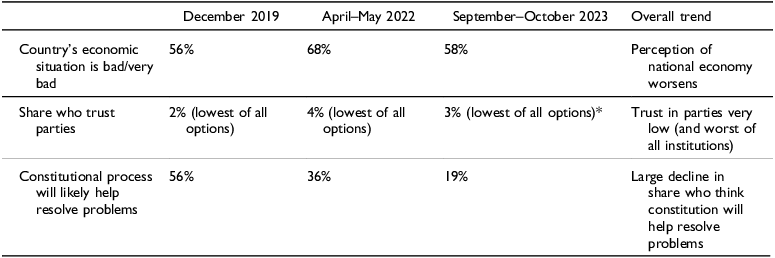

The “social explosion” and constitutional process took place in a context of weakened partisanship in Chile, with party identification reaching an all-time low of 14 percent in 2019 (Centro de Estudios Públicos [CEP] 2020). As Table 1 shows, parties were the least trusted institution listed in the CEP survey in 2019, with only two percent of respondents stating that they trusted parties (CEP 2020). That number remained low, and parties continued to be the least-trusted institution in 2022 and 2023. Because trust in parties did not vary during the period, we do not expect it to shape change in the communications strategies deployed by the constitutional campaign teams. Instead, and in line with the literature outlined earlier, we expect that weak partisanship created a situation in which campaigns could not rely on party identification to direct vote choice, so likely focused instead on policy issues (in 2020) and generic appeals in 2022 and 2023.

Table 1. Results of CEP Public Opinion Surveys

We expect this shift from policy to generic appeals because of the move from a voluntary vote in 2020 to a mandatory vote in 2022 and 2023. In accordance with Law 21524, participation in the 2020 plebiscite was voluntary, and only 50.9 percent of voting-age adults turned out (Decide Chile Reference Decide2023). In 2022 and 2023, voting was mandatory, and 85.82 percent and 84.44 percent of voting-age adults participated, respectively (Decide Chile Reference Decide2023). Keefer and Negretto (Reference Keefer and Negretto2024) show that these two electorates were different in character. The 2020 electorate was actively engaged and progressive leaning, whereas the expanded group was less engaged and more conservative (Keefer and Negretto Reference Keefer and Negretto2024). In line with the literature outlined earlier, we hypothesize that campaign teams deployed policy appeals in 2020 because voters were more politically engaged. By 2022 and 2023, the teams likely had shifted to generic appeals.

While we expect that campaign teams used broad generic appeals to reach these alienated sectors in 2022, by 2023, frustration with the constitutional process and democratic politics more generally had grown even more intense. The CEP data in Table 1 reveal that Chileans’ confidence in the ability of the constitutional process to resolve national problems plummeted between 2019 and 2023. While 56 percent of respondents believed the process could resolve the country’s problems in 2019, that number declined to 36 percent in 2022 and 19 percent in 2023 (CEP 2023). These figures underscore growing distrust in the constitutional process as time progressed. This trend was accompanied by a reinterpretation of the 2019 protests. Immediately following the social explosion in 2019, 55 percent of respondents said they supported the protests (CEP 2020); however, that number had declined to 39 percent by August 2021 (CEP 2023).Footnote 5

Research on Chile’s constitutional process provides insight into this declining support. Piscopo and Siavelis (Reference Piscopo and Siavelis2023, 146) argue that the missteps of some delegates during the 2021–2022 process—such as voting from the shower during a Zoom meeting and playing the guitar during a convention session—were amplified by right-wing media. This attention, paired with extensive coverage of scandals, contributed to a growing perception that the convention lacked expertise and seriousness (Heiss and Suárez-Cao Reference Heiss and Suárez-Cao2024). As Welp (Reference Welp2024) and Rozas-Bugueño (Reference Rozas-Bugueño2024) point out, this negatively affected the legitimacy of the 2021–2022 process and weakened public trust. This also contributed to the public’s decreased interest in the 2023 process (Heiss Reference Heiss2023). Evidence of this is the fact that 21.5 percent of voters nullified their ballot when electing the 2023 constituents (Decide Chile Reference Decide2023).

Given declining trust in the constitutional process, we expect that campaign organizers faced incentives to move to a very specific form of generic appeal: antipolitics. We define antipolitics as a focus that criticizes and undermines the actors and institutions associated with traditional politics. In summary, building on existing work and integrating specific characteristics of the Chilean context, we identify three hypotheses related to the content of campaign advertisements:

H1: The 2020 campaigns were more likely to focus on policy issues than on partisanship or generic appeals, given the relatively narrow and politically active nature of the electorate.

H2: The 2022 and 2023 campaigns were more likely to focus on generic appeals than on policy positions or partisanship, given the broad character of the electorate.

H3: The 2023 campaign likely focused on a generic “antipolitics” appeal, given the high level of distrust in the constitutional process.

Building on research about affective language in campaigns, we also derive a theoretical expectation about the use of emotion in plebiscite votes. Specifically, we expect that when the constitutional campaigns defend the status quo (i.e., “reject” in 2020 and “reject” in 2022), they will tend to use negative emotional language to activate the surveillance system and encourage voters to think critically and worry about the proposed change. We expect to see this relationship in the first two constitutional votes (2020 and 2022) but not in the third. In the first two elections, Chilean voters were focused on the question of whether they wanted to pursue a new path or stick with the 1980 constitution. By the third election, however, existing research suggests that most Chileans were disinterested and wanted to turn the page on the constitutional question (CEP 2023; Heiss Reference Heiss2023). The primary question, then, became how to put an end most effectively to the process. For that reason, we expect that the campaign teams were less interested in activating the surveillance system to defend the status quo in 2023 and instead relied on generic antipolitics appeals (as explained previously):

H4: The Reject 2020 and Reject 2022 campaigns were more likely to deploy negative emotional language than the three campaigns that supported constitutional change.

Methodology

To probe our four hypotheses, we use qualitative tools to analyze campaign television advertisements from the three constitutional campaigns. Although we recognize that not all voters viewed the advertisements, and that many Chileans engaged with campaign materials via alternative platforms, most notably social media, our focus is instructive for its cultural, historical, and political significance.Footnote 6 Since Chile’s 1988 plebiscite that ended the Pinochet dictatorship, television advertisements have garnered more interest and drawn a larger viewing public than in other Latin American countries (Matus and Echeverría Reference Matus, Echeverría, Veneti and Rovisco2023). Regulations that govern Chile’s electoral propaganda were approved before the 1988 vote and are still in place today, including the stipulation that television advertising is permitted only thirty days before the election or plebiscite and ends three days after.Footnote 7 Additionally, all free-to-access television stations are required to provide thirty minutes of broadcasting time (at no charge) for campaigns. During the 2020, 2022, and 2023 campaigns, stations paused their normal broadcasting twice a day to air the advertisements. In contrast to other countries in the region, Chile does not allow additional paid television advertising (Moke Reference Moke2006).

Surveys carried out by Chile’s National Council on Television (CNTV) confirm the importance of the television campaigns. Following the 2020 vote, 76.2 percent of survey respondents reported having watched at least some of the campaign (CNTV 2020b). In relation to the 2022 plebiscite, 61.1 percent of respondents reported that they were motivated to vote by the television ads, and nearly 20 percent stated that the ads inspired them to change their vote (CNTV 2022). In 2023, 86 percent reported having seen the campaign (CNTV 2023a). Ratings for the three campaigns were high, echoing these survey results (CNTV 2020b, 2022, 2023a).

To determine the focus of campaign messaging, we combine a qualitative analysis of interviews with ten political strategists and creatives who designed and executed each campaign, with an audiovisual discourse analysis of key advertisement segments.Footnote 8 To identify the signature spots, we use information gathered during our interviews, selecting segments that each campaign identified as exemplary for the significance (i.e., “manifesto pieces”) and salience (placement in the campaign). Given that ratings are highest on the first and last days of the campaign (CNTV 2020b, 2022, 2023a), we paid special attention to those advertisements.

To assess the emotional tone of campaign communication, we also drew on interviews with campaign creators and analyzed the audiovisual discourse of key ads. In addition, we generated transcripts for the fifty-six television spots from the 2020, 2022, and 2023 campaigns and used the Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC) software to examine the prevalence of emotive language in the ads (Boyd et al., Reference Boyd, Ashokkumar, Seraj and Pennebaker2022). LIWC is a text analysis software that uses word lists to classify content and calculate the percentage of words in a text that are “emotional” in general and “positive” or “negative,” more specifically. The Spanish dictionary that we employed was created by Ramírez-Esparza et al. (Reference Ramírez-Esparza, Pennebaker, García and Suriá2007) and has been used in a variety of political studies in Spanish-speaking countries. Because we have only six campaigns in total, we are unable to use quantitative tools to establish whether the trends we identify with LIWC are statistically significant. Still, we contend that the analysis provides interesting descriptive evidence that supports our conclusions from the semistructured interviews, in which participants emphasized the use of negative emotional language for referenda campaigns that defend the status quo.

Analysis of Chile’s constitutional campaigns

In this section, we analyze the advertisements from Chile’s three constitutional plebiscites. Drawing on interviews with the teams that designed the ad campaigns, we show that the “approve” and “reject” camps became less rooted in policy issues as time progressed. Although both campaigns focused on policy positions in 2020, they moved to generic appeals in 2022 and 2023.Footnote 9 By 2023, both campaigns relied on an “antipolitics” generic appeal. This trend is further verified in our qualitative discourse analysis of exemplar ads. The interview evidence reveals that changes in political communication resulted from two key factors: the move to mandatory voting (and the subsequent expansion of the electorate) and growing distrust in the constitutional process. Additionally, we provide evidence that the use of emotion in constitutional votes follows a predictable pattern in which actors who seek to defend the status quo deploy more negative emotional language.

The 2020 television campaigns

In response to the pandemic, the 2020 plebiscite was postponed from April 27 to October 25, 2020. The television ads ran twice a day from September 25 to October 22 on all of Chile’s free-to-air television channels. The first broadcast was from 12:45 to 1:00 p.m. and the second from 8:45 p.m. to 9:00 p.m. Each day, one of the broadcasts focused on whether to approve or reject the writing of a new constitution, and the other on whether a fully elected or mixed convention should write the constitution. The order alternated daily. During both time slots, each option was given seven minutes and thirty seconds. The allotted time for each option was distributed among the various political parties according to the percentage of the vote obtained in the 2017 Chamber of Deputies election (CNTV 2020a).

Occurring less than one year after the “social explosion,” the content of the “approve” and “reject” television campaigns of 2020 was closely tied to the context and experience of the protests. Interviews with campaign creators, as well as the discourse analysis of the ads, confirm our hypothesis that both campaigns were more likely to emphasize policy than partisanship, valence issues, or generic appeals. The “approve” campaign took an aspirational tone, arguing that a new constitution would allow Chile greater equality and better health care, education, and housing, as well as improved pensions and working conditions. The “reject” campaign, in contrast, argued that writing a new constitution would delay a response to these problems. Both campaigns recognized the population’s distrust of parties and opted for ads that relied less on political elites and instead prioritized “citizen stories.”Footnote 10

The first segment on the first day of the “reject” campaign exemplifies these themes. The segment begins with the statement, “In this ad, you will see politicians.” This is followed immediately by a rewinding sound and a revision of the statement to read, “In this ad, you will not see politicians” (T13 2020, 0:40–0:45).Footnote 11 Following this, Daniel Rosas, a social worker walking in La Pintana, a low-income municipality located in Santiago, welcomes viewers to the “reject” campaign. The camera follows Rosas inside his home, where he lists off the disqualifying terms often used to describe low-income residents who vote for the right: canuto (Evangelical), facho pobre (poor fascist), aspirational, ignorant (T13 2020, 00:56–1:00). He brushes off these characterizations, emphasizing that he lives and works in La Pintana and understands the needs of the people.Footnote 12 The camera follows Rosas as he walks through a vacant lot, alluding to a lack of adequate housing. “The state has been absent here,” he says. However, he argues that those struggling did not ask for a new constitution and that the writing of a new constitution would drain the state of resources that could be used to respond to people’s immediate needs. Rosas ends his testimony by stating that he is neither “right nor left,” that he views the constitutional process as “full of lies” (T13 2020, 01:35-01:52).

Here, the “reject” campaign moves away from partisanship, avoiding party insignias and instead using citizen testimony to articulate the importance of policy change, but not via a constitutional rewrite. The segment also relies on negative emotional appeals that generate anxiety or worry among viewers about the possible effects of a new constitution. This tone provides evidence to support our hypothesis that campaigns defending the status quo are more likely to deploy negative emotional language than those pushing for a new constitution.

Another example of the “reject” campaign’s emphasis on policy but questioning the need for a new constitution can be seen later in the first episode. The segment features voters who had planned to vote “approve” but didn’t think that Chile could afford the constitutional process; they were concerned that the same people would write the constitution as always (emphasizing distrust in the political class and parties); and they couldn’t wait two more years for policy change. The clip ends by arguing that citizens should “reject to reform.” The ad continues with a piece that uses humor to argue that the constitution would delay a response to Chile’s needs. In the clip, a woman’s car breaks down, and a mechanic tells her that what she needs to fix her car is a new constitution. The ad ends with a jingle, which appears repeatedly throughout the monthlong television campaign: “A new constitution does not guarantee you a better education. A new constitution does not even guarantee your pension. There will be a faster solution for health, pensions, and education if we come together and reject with all our heart” (T13 2020, 07:46–08:02). All this reveals a strong emphasis on policy and the downplaying of partisanship. Additionally, it reveals multiple instances of emotional appeals that tap into anxiety and worry. Political strategists who worked on the 2020 “reject” campaign told us that they knew that they could not win the plebiscite. Instead, they aimed to maintain their core electorate by ensuring that right-wing voters felt represented in the campaign. The strategists noted that their voters were disappointed in parties and held very weak attachments. In fact, they worried about losing voters to the new far-right Republican party.Footnote 13 As a result, the campaign focused on policy rather than partisanship. Interestingly, the strategists did not rely heavily on generic appeals. This was because they perceived that a voluntary vote would attract relatively engaged citizens (a “core” electorate) with at least some attachment to the system. The strategists believed these voters held defined policy positions, if not trust in parties, and wanted to see those views represented.Footnote 14

Although the content of both campaigns connects to the demands of the “social explosion,” they differ markedly in how they narrate that experience. The aesthetic of the “approve” campaign seeks to keep the hopeful spirit of the protests alive. The campaign focuses on multiple policy areas, including social rights, climate change, and diversity. The television ads include repeated images of the 2019 marches, the sounds of the banging of pots and pans, and iconic protest signs and graffiti. In this way, the campaign uses audiovisual cues to argue that voting in favor of the writing of a new constitution is the next stage of political activism for those seeking a brighter future. This tactic echoes Brader’s (Reference Brader2005, 391) observation that “enthusiasm appeals” can be deployed to “increase the desire to participate and reinforce the salience of prior beliefs.”

The “reject” campaign, by contrast, portrays the 2019 protests as an experience of violence, lawlessness, and uncertainty. As one political strategist in the “reject” campaign told us, “Approve had everything on their side…. So, we had nothing else to play with except the fear factor. The fear of jumping into the unknown.”Footnote 15 This confirms our expectation that in plebiscite votes, campaigns that seek to defend the status quo are more likely to use negative emotions than campaigns that embrace change. This is because fear appeals activate the surveillance system, encouraging voters to think carefully and critically about their choice, even if that requires abandoning previously held beliefs.

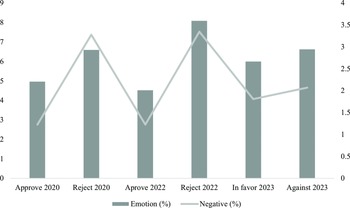

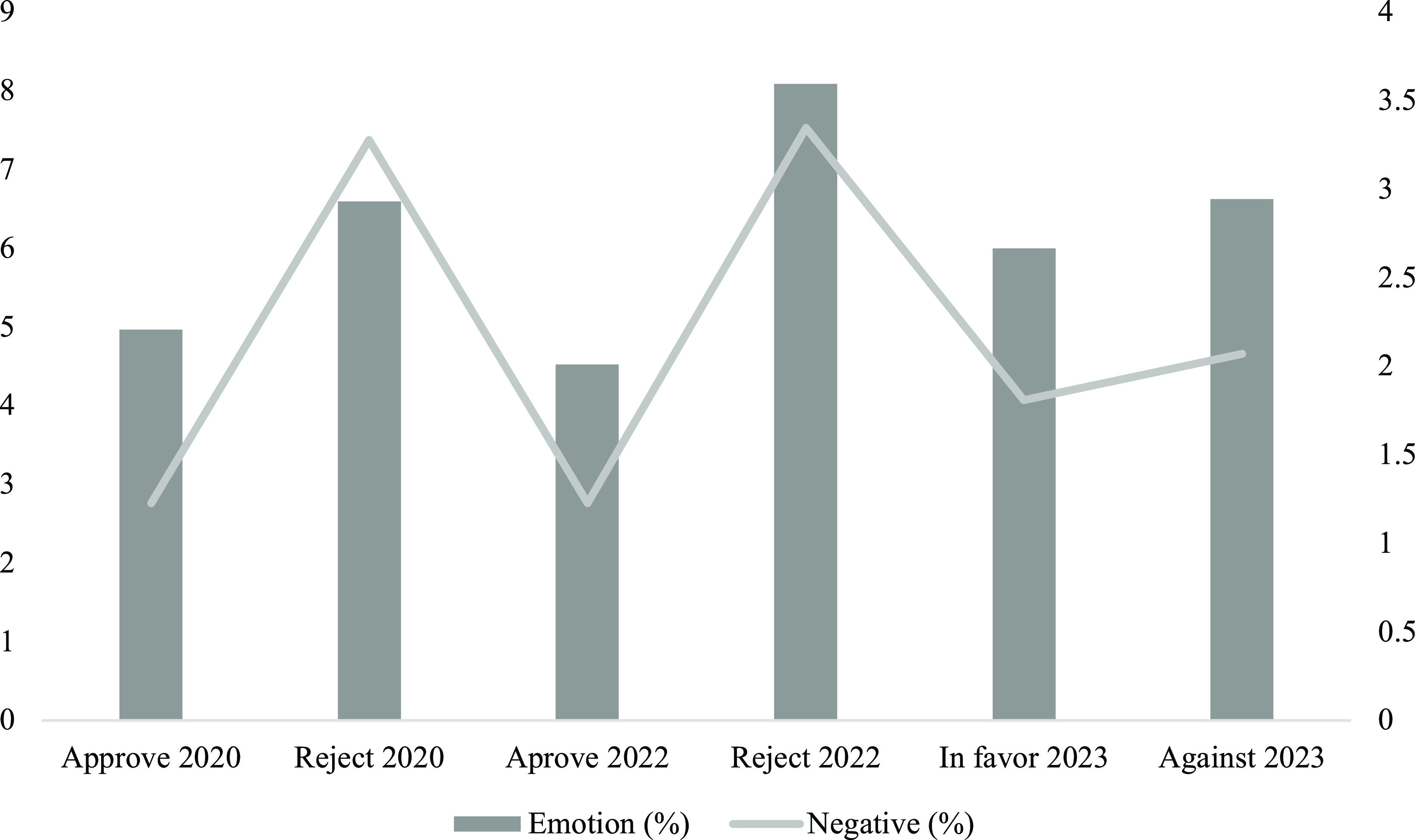

As Figure 1 shows, a LIWC analysis of the television advertisement transcripts similarly suggests that the 2020 “reject” campaign relied more heavily on emotional language than the 2020 “approve” campaign. Specifically, 6.6 percent of the reject campaign’s language was emotional in nature, while only 4.97 percent of the language in the 2020 “approve” advertisements was emotional. Moreover, 3.28 percent of the “reject” language was negative in emotional tone, compared to only 1.23 percent in the 2020 “approve” campaign. While we cannot establish whether these differences are statistically significant, the share of negative emotional language in the pro–status quo campaign nearly tripled that of the “change” campaign, suggesting that the use of negative emotion in referendum campaigns is more common when defending a status quo position.

Figure 1. LIWC analysis of campaign ads.

The 2022 Campaigns

In 2022, the campaign to “approve” the constitutional draft, which ran from July 6 to September 1, focused on calming voter anxiety. A member of the “approve” creative team said that the television ads sought to respond to the public’s frustration with the convention delegates by establishing a serious, confident, and republican tone and used a hopeful emotional appeal to promote unity. With this in mind, the team used national symbols such as the flag and the anthem to lessen anxiety.Footnote 16 To that end, they agreed on a message that centered on the generic appeal avanzar (to advance or move forward) rather than on specific policies. Members of the campaign team noted that they hoped the focus would attract new voters, who would be forced to participate because of mandatory voting.Footnote 17

A spot that exemplifies the “approve” campaign’s strategy begins with historical footage of Chileans in different time periods dancing the cueca (the national dance), marching in the streets, and holding a giant flag. A voice-over begins: “When we dare to imagine a better country, avanzamos [we move forward]. When we commit to change, avanzamos” (ApruebaxChile 2022, 0:06–0:09). As the spot continues, it points to the moments in which social movements have allowed the country to move forward on women’s rights, the return to democracy, education, and greater equality. These references are interspersed with images of national unity, such as sports triumphs, resilience in the wake of national disaster, and the response to the pandemic, all while a voice-over repeats the word avanzamos. The emblematic clip confirms our expectation that referendum campaigns that focus on change must avoid negative emotional language. Additionally, we see how the 2022 “approve” campaign moved away from a policy focus to the generic appeal of “advancement.”

The 2022 “reject” campaign was marked by a strong use of emotional appeals. The initial diagnosis of one political strategist was that “the only way to approach the campaign was to distance it from political codes, that is to say from left and right,” and to do that “following the logic of Jonathan Haidt and other social psychologists by taking it to the emotional rather than the rational plane.”Footnote 18 He noted that they pursued this path because of the mandatory nature of the vote and the expansion of the electorate. To win over voters who had never voted before and who were disgusted with politics, campaign coordinators decided to downplay references to partisanship and policy, focusing instead on “commonsense” frustration with the constitutional convention.Footnote 19 While the 2022 “approve” campaign deployed some policy-related terms and the generic issue of advancement, the “reject” campaign switched its emphasis to the generic and emotional appeal of love.

This is clear in an emblematic spot created by one of the firms hired for the campaign, Wolf Agency, which won the 2022 Reed Latino Awards for political communication. The spot begins with the following phrase: “This constitution proposal is poorly made because it was made with the wrong emotion.” This transitions to images with actors in everyday situations acting in anger and a voice-over: “Anger. It darkens everything. A cry with anger is desperation. Leadership with anger is abuse.” The voice continues with phrases like “A cause with anger is violence” and “A response with anger is vengeance.” The images alternate between representations of violent protest and looting and the faces of constitutional convention representatives who made polemic statements. The first half of the spot ends with a man holding a copy of the constitutional draft in his hand and shaking his head, with the voice-over: “A dream written with anger is a nightmare” (Ciudadanos a Favor de Chile 2022a, 00:00–00:40). The emphasis on the love-anger dichotomy, rather than partisanship or policy, confirms our expectation that in settings of low party trust, campaigns turn to commonsense and generic appeals. The spot also underscores how the “reject” team used negative emotions to generate anxiety about the proposed constitution while appealing to a commonly shared desire to feel love.

Another spot that appeared frequently during the monthlong campaign provides further evidence of the way the “reject” campaign used anxiety and fear to activate voters’ surveillance system. The spot begins with the image of a showerhead, running water, and a voice-over suggesting that this is the moment in the day when we all stop to think and clarify things. Images of different people appear, with a voice-over expressing the uncertainty that they are purportedly feeling about different aspects of the constitution. In one of these, a man appears with the voice-over, “If health care is state run, I can only imagine what the lines will be like in the doctors’ offices.” In another, a man ruminates about the pension system: “It’s all well and good to improve pensions, but I can’t leave my inheritance to my children? Even though it’s my savings?” (Ciudadanos a Favor de Chile 2022b, 00:06–00:54). Here the campaign uses anxiety to prompt voters to think carefully about the proposal, providing support for our expectation about the role of emotion in plebiscite campaigns.

Recognizing that a sizable share of the Chilean public did not trust politicians or convention delegates, the “reject” creative team used first-person testimonies to appeal to alienated voters. In an interview, one member of the creative team explained that they sought out “believable characters” with whom Chileans were more likely to identify.Footnote 20 They focused on those who “had a right to be angry” but who “had realized that anger was not the path.” One of the campaign creatives explained that they decided on this approach because they knew the “reject” message appealed to many voters, but they needed trustworthy spokespeople, and Chileans did not trust politicians.Footnote 21

In accordance with our expectations about the use of negative emotional language in plebiscite votes, we find that 3.35 percent of words from the “reject” campaign were negative, while only 1.23 percent of words in the “approve” ads evoked negative emotions. As Figure 1 shows, the gap in the use of negative emotional appeals between the two campaigns is nearly identical to that seen in 2020. While we cannot determine whether this difference is statistically significant, it does provide another datapoint in support of our assertion that campaigns defending the status quo are more likely to use negative emotional language than those trying to convince voters to change course.

The 2023 campaign

In the 2023 vote, parties of the left and center-left, as well as those of the right and center-right, switched positions. Conservative parties opted to support the draft constitution, while progressive actors encouraged voters to reject the proposal. This was because the far-right Republican Party (Partido Republicano de Chile) controlled the largest share of seats in the 2023 convention and used its power to advance a conservative proposal. Indeed, while the 2021–2022 constitutional process had been criticized for being too progressive, the 2022–2023 convention was seen as equally out of touch with Chilean voters, but this time because of its far-right tendency.

Leading up to the 2023 television campaign, which ran from November 17 to December 14, both the “in favor” and “against” campaigns realized that most voters were tired of the constitutional process.Footnote 22 As one of the political strategists from the “against” campaign told us, “For many people, the constitutional process ended on September 4…. The polls we had indicated that people didn’t want this process.”Footnote 23 In response to this political climate, both campaigns shifted to a generic appeal that was rooted in antipolitics or frustration with politics. Additionally, the election ceased to be understood in terms of defending or rejecting the status quo and became a competition about how to end the process most effectively.

The “against” campaign adopted an antipolitics frame by minimizing in-person events, avoiding the use of party symbols, and limiting the participation of political elites.Footnote 24 The campaign focused communication on three key points: The constitutional draft was divisive, it was harmful, and it would not provide closure to the ongoing process. Like the “reject” campaign in 2022, the “against” team in 2023 designed a campaign to win rather than one aimed at boosting trust in the parties. In fact, the team actively appealed to voters who were sick of politics as usual. As a member of the creative team told us, the campaign adopted a generic antipolitics frame because it was a message that virtually all voters agreed with.Footnote 25

The “against” campaign combined this antipolitics message with the use of negative emotion to activate anxiety about how the new constitution might harm Chileans’ well-being. The television campaign opens with a segment that argues the constitutional draft will rob citizens of recent gains in education, public health, and reproductive rights. This is followed by a spot featuring a long table with people shouting at each other, emphasizing that “the extremes” have failed to listen, and as a result, the constitutional draft will divide society. The first broadcast also introduces the slogan of the campaign with a spot that begins with the statement: “We are against what no one wants.” This is followed by actors who represent a diversity of voices (in terms of age, gender, social class, and so on) listing things that “no one wants”:

No one wants to be fired without reason.

No one wants Chile to do poorly.

No one wants their savings to be stolen.

No one wants a poor education for their children.

No one wants to be afraid to be in the street.

No one wants their rights to be taken away.

No one wants a few people to keep what belongs to everyone.

No one wants to feel excluded.

No one wants to be told how far their dreams can take them.

No one wants us to continue to be divided.

No one wants a text that hurts us. (CNTV 2023b, 02:38–3:40)

The “in favor” campaign also adopted a generic antipolitics message. This tactic is best captured by a polemic ad that aired one week into the television campaign and would shape the rest of the electoral process (Hermosilla Reference Hermosilla2023). The ad begins with a series of images: a Chilean flag, a family watching the news on television, a group of older men standing by a newspaper stand, and finally, a church steeple burning. The camera returns to one of the men, who says: “The ones who burned down the whole country to have a new constitution now want to keep the one we have. They want to keep everything as it is.” The ad continues, repeating the same phrasing to make a series of critiques of President Gabriel Boric’s government and associate it with the “against” option. A woman in an elementary school teacher uniform says: “The ones who became famous for demanding quality education for everyone are now in power. And what have they done?” As she speaks, footage of Boric, Camila Vallejo, and Giorgio Jackson at a student march in 2011 appears on the screen. This is followed by a woman in a nursing uniform saying: “The ones who thought that Chile was going to heal itself with fires in the streets now want to continue with the same Constitution. I tell them to send their revolution to quarantine. Thanks for nothing.” As she speaks, footage of violent protests from 2019 appears on the screen, visually linking the protests to the images of Boric in 2011. The ad ends with the same woman saying: “I’m going to vote in favor. Y que se jodan [and screw them]” (Ciudadanos a Favor de Chile 2023, 00:02–1:28).

The ad was actively debated in the days that followed (Matamala Reference Matamala2023). In response, the “against” campaign launched an ad that appropriated the term joder (to screw), connecting it to the core messages of the campaign: that the constitutional draft was harmful and divisive. The ad begins: “They said that they were going to write a constitution with love, but then they told us: screw you.” The ad continues:

The only thing this text does is to take rights away from you and from all women.

Who do they want to screw?

Just reading it, you realize that the private pension funds will continue paying miserable pensions.

Who do they want to screw?

And was it clear to you that the new text is only for them, those they consider the real Chileans?

Who do they want to screw?

A group of lawyers realized that it’s so badly done that they won’t even be able to prosecute the drug traffickers.

Who do they want to screw?

It also takes away funding from the poorest municipalities of the country.

Who do they want to screw?

The ad ends with: “Vote ‘against’ so that no one is screwed” (Latorre Reference Latorre2023, 00:00–00:48). The spot provides evidence of one way that the “against” campaign used negative emotional language to heighten anxiety about the draft constitution. In this specific instance, the “against” team used words from the “in favor” ad to directly link that anger and anxiety to the draft constitution. As Figure 1 shows, the gap in the use of negative emotional language between the “in favor” and “against” camps narrowed substantially in 2023. Whereas in the 2020 and 2022 campaigns, the pro–status quo campaign used almost triple the amount of negative emotional language, the “against” campaign of 2023 used only 13 percent more negative language. This is in line with our expectation that, by 2023, the predominant emotion about constitutional reform was exhaustion and a desire to move on. In this setting, an “antipolitics” appeal was seen by the pro–status quo camp as the most effective strategy.Footnote 26

Conclusion

This article has presented an analysis of Chile’s three constitutional plebiscite television campaigns to explore how campaign teams communicate with voters in settings of weak parties and low institutional trust. Combining in-depth interviews with the political and creative teams, an audiovisual discourse analysis of advertisements, and a LIWC language analysis of the transcripts, we identify each campaign’s central message, describe the use of emotional appeals, and explain how and why the teams used these tools to connect with voters. Specifically, we find that the 2020 campaigns focused on policy, while the two subsequent votes centered on generic appeals, with both sides ultimately pursuing an “antipolitics” message in 2023. Additionally, we show that negative emotional appeals were more likely to be deployed by the team defending the status quo.

The analysis reveals that these trends across the three campaigns were influenced by key aspects of Chile’s political-economic context, namely the expansion of the electorate (as a result of mandatory voting) and voters’ growing discontent with the constitutional process. In this way, the article advances our understanding of how campaigns work in settings where partisan appeals are no longer feasible. It also sheds light on the specific way that emotional appeals are deployed in referenda and plebiscite votes.

The article deepens our understanding of campaigns by focusing on the actors who developed the strategy. Specifically, our interviews with the political and creative teams provide insights into how and why campaigns move from policy to generic appeals and how they approach the issue of emotion. The interviews reveal that these individuals were shaped by the local political context, and they were acutely aware that, as the electorate expanded, they needed to alter messaging to account for the fact that new voters distrusted parties and did not approve of the constitutional process. In this way, the interviews confirm that campaigns may work differently in distinct democratic contexts. Moreover, the article affirms the importance of qualitative work that investigates how and why political actors formulate campaign strategies.

In addition to advancing our scholarly understanding of campaigns, this article sheds light on key aspects of Chile’s constitutional process. First, the article reveals that the 2020 campaign, which focused on whether to rewrite the constitution and sought to convince a relatively narrow and politically active electorate, was a policy-focused moment. Indeed, in the immediate aftermath of the “social explosion,” both political teams reported that they created messages aimed at addressing citizen concerns about inequality, public service quality, and employment, among other things. The campaign teams recognized that their voters were tuned in to multiple policy issues, including education, health, pensions, and labor markets. While the campaigns downplayed the role of parties, they didn’t shy away from these issues, revealing a window of opportunity in 2020 to achieve policy reform.

By 2022 and 2023, however, that window had closed. Growing discontent and an enlarged electorate drove teams on both sides to emphasize generic appeals rather than deeper policy issues. In 2022, the “approve” team focused on advancement, while the “reject” campaign focused on love. By 2023, however, both teams focused on the same generic appeal: antipolitics and the idea that things were bad in Chile. In doing this, the campaign teams further fanned the flames of distrust and alienation. Indeed, a member of the 2023 “against” creative team who had worked on previous presidential campaigns noted that he knew the antipolitics approach endangered future elections by entrenching distrust of politicians, but he said it was a “winning strategy.”Footnote 27

All this points to the ways that cycles of discontent are easily perpetuated and reinforced in settings of mandatory voting, weak parties, and high levels of anger with the political process. This happens because campaign teams face an incentive to focus attention away from parties and policy, “selling” discontent instead. This, in turn, deepens patterns of alienation and frustration. Our findings, therefore, shed new light on the way that campaigns and political advertising may contribute to the erosion of democratic trust. Future work should explore whether the same holds true in candidate-centered elections.

A final contribution of this article is linked to the findings about campaign communication in settings of referenda and plebiscites. Much of the scholarly attention about campaigns focuses on candidate-centered contests, paying little attention to referenda. We remedy that focus and provide initial evidence that suggests that in plebiscite votes for which voters see their choice through a for versus against status quo lens, campaigns that defend the status quo are more likely to deploy negative emotions than those attempting to persuade voters of the need to change. Future research should explore whether this holds true in other recent referenda votes and what that means for the ability to achieve institutional change through direct democracy.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the University of Richmond and George Mason University for funding the field research associated with this article. We are also grateful to Luai Allarakia, Dan Chen, Regis Dandoy, Dana El Kurd, Sandra Joireman, Juan Pablo Luna, Pablo Medina, Vicky Murillo, Kevin Pallister, Jennifer Piscopo, Byunghwan Son and Aleksandra Sznajder-Lee for reading and commenting on early drafts of the paper. The article also benefited immensely from the constructive feedback of three anonymous LARR reviewers.