Introduction

Immigration is a hot topic across Western democracies and a major driver behind the emergence of a new cultural cleavage in the 2010s (Dalton, Reference Dalton2018; Green‐Pedersen & Otjes, Reference Green‐Pedersen and Otjes2019; Norris & Inglehart, Reference Norris and Inglehart2019). Nonetheless, the comparative and empirical study of media effects on the degree of importance associated with immigration as a policy issue stays limitedFootnote 1 and the results are conflicting (Bleich et al., Reference Bleich, Bloemraad and De Graauw2015; Eberl et al., Reference Eberl, Meltzer, Heidenreich, Herrero, Theorin, Lind, Berganza, Boomgaarden, Schemer and Strömbäck2018; Lecheler et al., Reference Lecheler, Matthes and Boomgaarden2019). For instance, regarding the intense attention to immigration around the so‐called ‘refugee crisis’ in 2015, Dennison and Geddes (Reference Dennison and Geddes2019, p.107) argued that ‘it would be dubious, […], to ascribe such strong causal effects to negative media coverage’. More generally, the salience of immigration is highlighted by work on the gap between policy objectives and the subsequent outcome of immigration control (often interpreted as a lack of government control; Hadj Abdou et al., Reference Hadj Abdou, Bale and Geddes2022; Hollifield et al., Reference Hollifield, Martin and Orrenius2014). Remarkably, existing accounts of the politicisation of immigration also exclude the media as a potential explanation for intense public attention to this topic, focusing almost exclusively on the agency of political parties (Grande et al., Reference Grande, Schwarzbözl and Fatke2019; Hutter & Kriesi, Reference Hutter and Kriesi2021).

By contrast, research on political communication highlights the importance of the media in shaping public opinion despite the strong variations found in its development (Harteveld et al., Reference Harteveld, Schaper, De Lange and Van Der Brug2018; Tesler & Zaller, Reference Tesler, Zaller, Kenski and Jamieson2017; Vestergaard, Reference Vestergaard2020). Within this context, we focus on agenda‐setting effects on the importance attached to immigration as an issue: how patterns of news reporting about immigration (volume of news and political claims) and its content (tone of political claims) are associated with changes across the importance attached to immigration in comparison to other policy‐related issues in seven Western European Union (EU) member states between 2002 and 2009. To reach this objective, we evaluate the indirect effects of the news environment because we cannot disentangle direct media exposure from the overall information environment. Thereby, we assume that individuals not directly exposed to media content are indirectly influenced by interpersonal communication as citizens are embedded in their social settings (Hopmann et al., Reference Hopmann, Vliegenthart, De Vreese and Albæk2010).

Drawing on the extensive media analysis by Van der Brug et al. (Reference Van der Brug, D'Amato, Ruedin and Berkhout2015), we use a continuous sample of claims‐making derived from quality newspapers and tabloids to create a comparative dataset to assess agenda setting effects. Broadly, a political claim describes any purposive political demand, proposal or comment made by or in the name of a collective group in the national public sphere that affects the interests of the claimant or another group (Koopmans & Statham, Reference Koopmans and Statham2010). The tone of political claims was distinguished between positive/expansive (open to immigration flows, support multiculturalism) and negative/restrictive claims (expressing opposition to inflows or monocultural positions). The outcome variable is the electorate's ranking of immigration among the two most important issues (MII) at the national level, as measured by Eurobarometer surveys. Hence, our study focuses on the judgements of the national importance of a particular policy issue rather than on the personal importance attached to immigration. An important issue refers to an issue that citizens care about a lot at a particular time, and higher salience means citizens are more cognitively and behaviourally engaged with a particular issue (Jennings & Wlezien, Reference Jennings and Wlezien2011; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Saunders and Farhart2016).

Our contributions to the literature in terms of research design are threefold. First, we adopt a consistent comparative dimension by focusing on seven Western EU member‐states while cross‐national evaluations of media effects on issue salience using survey data are still scarce or limited to case studies (Eberl et al., Reference Eberl, Meltzer, Heidenreich, Herrero, Theorin, Lind, Berganza, Boomgaarden, Schemer and Strömbäck2018; Lecheler et al., Reference Lecheler, Matthes and Boomgaarden2019). Second, we propose systematic and comparative analyses of media content to capture the effects on issue salience from a longitudinal perspective rather than focusing on a brief period or specific exogenous events, like the 2015 ‘refugee crisis’ or elections (Dunaway et al., Reference Dunaway, Branton and Abrajano2010; Harteveld et al., Reference Harteveld, Schaper, De Lange and Van Der Brug2018). In contrast to short‐term coverage of the news (Cinalli et al., Reference Cinalli, Trenz, Brändle, Eisele and Lahusen2021; Strömbäck et al., Reference Strömbäck, Meltzer, Eberl, Schemer and Boomgaarden2021), we do not only include periods in which migration is a priori likely to be salient. Third, our investigation focuses on the media effects of the importance the public attach to immigration rather than on public attitudes or policy preferences, which is an area of analysis still in its infancy (Hopkins et al., Reference Hopkins, Sides and Citrin2019; Kustov et al., Reference Kustov, Laaker and Reller2021).

Our research shows significant agenda‐setting effects of the media environment on public concern about immigration at the cross‐national level. We find substantial and statistically significant agenda‐setting effects regarding the transmission of object salience, but not regarding attribute salience, highlighting a distinction overlooked in most existing work. Media effects on the importance associated with immigration in Europe during the 2000s appear substantial and seem to show greater relevance than environmental factors, like gross domestic product (GDP) growth or changes in the size of the foreign population. We show that the salience of immigration in printed news was strongly associated with variations in the ranking of immigration as an important issue in the seven selected countries. Our results suggest that the media environment should be considered as an independent variable behind the variance on public concern about immigration. Looking beyond the public, our results contain important repercussions at the theoretical level, particularly on research related to the politicisation of immigration and interparty competition on this topic. Secondly, our analysis presents a challenge to basic assumptions of the policy gap thesis and thermostatic models of policymaking that support contemporary analysis of immigration policy.

Media effects on public opinion

The scope of research on the impact of the media on public attitudes or policy preferences towards immigration largely exceeds studies focusing on the public salience of the issue. Comparative research in the Netherlands and Denmark during the 2000s showed that media salience was the only relevant contextual effect on negative public attitudes in Denmark, whilst immigrant inflow and most media characteristics influenced attitudes towards immigrants in the Netherlands (Van Klingeren et al., Reference Van Klingeren, Boomgaarden, Vliegenthart and De Vreese2015). A study of the influence of the news about the 2015 ‘refugee crisis’ on public attitudes towards the EU and national institutions concluded that the number of asylum requests and the media coverage had a positive effect on levels of Euroscepticism (Harteveld et al., Reference Harteveld, Schaper, De Lange and Van Der Brug2018). The authors suggest that these effects are dependent on citizens’ prior attitudes or predispositions: the effects are stronger for right‐leaning citizens and individuals who are more negatively predisposed towards immigration.

Drawing on data from the REMINDER project, Eberl and Meltzer (Reference Eberl, Meltzer, Strömbäck, Meltzer, Eberl, Schemer and Boomgaarden2021) looked at the relationship between media texts between 2013 and 2016 with the respondents’ media use in six European countries. They found that changes in the negative and positive sentiments in the media sources used by the respondents can affect their attitudes, whilst the level of political sophistication of the audience is an important moderator of this relationship. The analysis of media effects on citizens’ overestimation of the share of the foreign‐born population in their country shows that the increase of media coverage of migration in the respondents’ media diets reduced these estimates, while frequent use of social media and television increased innumeracy (Meltzer & Schemer, Reference Meltzer, Schemer, Strömbäck, Eberl, Meltzer, Schemer and Boomgaarden2021). In this context, the different frames included in the news outlets can lead to different reactions in the public, suggesting that communication effects can vary according to the media format (Theorin, Reference Theorin, Strömbäck, Meltzer, Eberl, Schemer and Boomgaarden2021).

By contrast, research investigating media effects on public concern about immigration is limited. Studies in the United States of America suggest that an increase in media coverage of immigration is followed by an increase in public concern about this issue (Dunaway et al., Reference Dunaway, Branton and Abrajano2010). Border states see more news about immigration than non‐border states, implying greater concern about the topic. Resident voters in border states are more likely to rank immigration as the country's most important problem (Dunaway et al., Reference Dunaway, Branton and Abrajano2010). Communication factors appear to have relevant effects on public concern. Research conducted in Europe from 2002 to 2016 interpreted the policy preferences and salience of immigration as a potential thermostat of public opinion (Hatton, Reference Hatton2021). This study reported strong fluctuations in the importance of immigration in public opinion across countries, which appears to be related to short‐term environmental factors rather than with media coverage (Hatton, Reference Hatton2021). In short, the study of media effects on public concern about immigration is still scarce and reveals contradictory results.

Combining migration studies and agenda setting

We explore the theory of agenda setting to understand the cross‐national variation of public concern about immigration. Agenda setting refers to the process of mutual influence between the media and the audience's perceptions of the issues of the day (Eberl et al., Reference Eberl, Meltzer, Heidenreich, Herrero, Theorin, Lind, Berganza, Boomgaarden, Schemer and Strömbäck2018; McCombs, Reference McCombs2014). News coverage by mainstream media has an important influence on voters’ assessment of the relevance and importance of social phenomena, especially on the urgency of solving them (Roessler, Reference Roessler, Donsbach and Traugott2007). In the present case, when the mass media highlight immigration as newsworthy and increase its visibility, the audience will be more likely to consider this topic a relevant issue (Damstra et al., Reference Damstra, Jacobs, Boukes and Vliegenthart2021; Walgrave & van Aelst, Reference Walgrave and Van Aelst2006). Unlike other topics like the economy, immigration is a non‐obtrusive social phenomenon, and most people only have indirect experience of this issue (Gelman & Margalit, Reference Gelman and Margalit2021; McLaren et al., Reference McLaren, Boomgaarden and Vliegenthart2018). As personal experience is limited, this trend reinforces the media's priming effect on the electorate on this issue (McLaren et al., Reference McLaren, Boomgaarden and Vliegenthart2018). The media are necessary to inform the public, but this reliance on the media can lead to strong fluctuations in the importance attached to immigration in relation to other obtrusive political topics (McCombs, Reference McCombs2014).

Media effects are likely to affect voters, especially if we think of them as rationally ignorant about politics (Druckman, Reference Druckman2014; Kustov et al., Reference Kustov, Laaker and Reller2021). This is particularly the case with complex issues like immigration, which can be difficult even for trained political scientists and experts to fully understand: the diversity of types of inflows (labour, family reunification, asylum, irregular, student, etc.), the endogenous and exogenous causal factors supporting global migration networks, the different legal frameworks in use, as well as the distribution of costs and benefits across the host society, pose an enormous obstacle to a full comprehension of this social phenomenon (Rosenblum & Tichenor, Reference Rosenblum and Tichenor2012). Moreover, good information is rarely available (Blinder & Jeannet, Reference Blinder and Jeannet2018), and it can be difficult to distinguish immigration policy from other public policies. Since the policy of immigration control is the result of a complex bargaining process between different stakeholders (Czaika & de Haas, Reference Czaika and De Haas2013), it is also difficult to determine who is responsible for policy outcomes. Immigration is therefore a policy area where the public must rely heavily on media information (Lecheler et al., Reference Lecheler, Matthes and Boomgaarden2019), which happens on two levels.

The first level of agenda setting concerns the transmission of object salience – which topics are considered important and in search of a solution – between the media and public opinion (McCombs, Reference McCombs2014). Here, we explore the potential relationship between the volume, intensity of reporting or visibility of international migration in the print media and public opinion on the priority of immigration compared to other political topics (Harteveld et al., Reference Harteveld, Schaper, De Lange and Van Der Brug2018; McLaren et al., Reference McLaren, Boomgaarden and Vliegenthart2018; Van Klingeren et al., Reference Van Klingeren, Boomgaarden, Vliegenthart and De Vreese2015; Vestergaard, Reference Vestergaard2020). In the literature, there are two dominant approaches to capture this volume or intensity: the amount of news coverage in terms of articles on a topic, and the level of attention to the topic within these articles (Vliegenthart, Reference Vliegenthart, Weinar, Bonjour and Zhyznomirska2018), in our case, the level of claims. Following this theoretical distinction, the first expectation suggests that:

Salience of news: An increase in the amount of news about immigration leads to an increase in the proportion of respondents who rank immigration among the most important issues facing their country.

The second level of agenda setting focuses on the transmission of attribute salience – the process by which the media tell the public how to think about social phenomena by associating attributes with objects (McCombs, Reference McCombs2014). This means looking at what happens within articles: While some news articles related to immigration are purely descriptive, others also include more in‐depth analysis, reporting on the political claims by different collective actors, such as political parties or civil society associations (Van der Brug et al., Reference Van der Brug, D'Amato, Ruedin and Berkhout2015; Vliegenthart, Reference Vliegenthart, Weinar, Bonjour and Zhyznomirska2018). Political commentary included in the news is conceived as a vehicle for public opinion formation, as the frames and cues used by political actors will help citizens to define and interpret political phenomena (Cinalli et al., Reference Cinalli, Trenz, Brändle, Eisele and Lahusen2021; Kriesi, Reference Kriesi, Esser and Pfetsch2004). Elite opinion is reinforced by the political capital of actors and can have more influence on public judgements of the national importance of issues than news that has been stripped of such claims. Citizens evaluate the content and implications of a message based on its source and are more likely to agree when they support the politicians or social group proposing it. The media act as gatekeepers, deciding what is newsworthy by including information and political claims in their news, choosing which comments and voices are valuable to the public, ‘important’ or newsworthy (Bleich et al., Reference Bleich, Bloemraad and De Graauw2015; Kriesi, Reference Kriesi, Esser and Pfetsch2004).

Increased public exposure to commentary on immigration‐related topics by political actors can lead to consistent variation in the political importance associated with immigration across the electorate. In this perspective, the media are interpreted as a platform for political actors to present their political claims. Thus, the content of the news is considered more important rather than the total number of news items (Vliegenthart, Reference Vliegenthart, Weinar, Bonjour and Zhyznomirska2018), although both approaches capture salience in some form. Individuals are more likely to care about immigration as a top priority when their exposure to political claims on the subject is higher (Harteveld et al., Reference Harteveld, Schaper, De Lange and Van Der Brug2018; Zaller, Reference Zaller1992). The second expectation from our theoretical model concerns the potential effects of the volume of political claims on public concern about immigration:

Salience of political claims: An increase in the number of political claims about immigration leads to an increase in the proportion of respondents who rank immigration among the most important issues facing their country.

However, analysing the volume and intensity of news coverage or the visibility of political claims about immigration is not sufficient to explore the impact of the media on public concern about immigration. Another strand of research on media effects distinguishes the tone of media messages about immigration as a separate explanatory variable (Boomgaarden & Vliegenthart, Reference Boomgaarden and Vliegenthart2009; Damstra et al., Reference Damstra, Jacobs, Boukes and Vliegenthart2021; Van Klingeren et al., Reference Van Klingeren, Boomgaarden, Vliegenthart and De Vreese2015). The overall emphasis on a particular attribute of immigration may have greater influence on the salience of immigration than the news that is not differentiated (Cinalli et al., Reference Cinalli, Trenz, Brändle, Eisele and Lahusen2021; McLaren et al., Reference McLaren, Boomgaarden and Vliegenthart2018). For instance, using a survey experiment on immigration, research in the United Kingdom (UK) suggests that the language used in the British media influences the political cognition of the electorate, although it is difficult to assess how strong and durable such effects are outside of the lab (Blinder & Jeannet, Reference Blinder and Jeannet2018).

Competing claims have an important structuring and orienting function, providing templates, peripheral cues and heuristics for understanding politics from different perspectives (Eberl et al., Reference Eberl, Meltzer, Heidenreich, Herrero, Theorin, Lind, Berganza, Boomgaarden, Schemer and Strömbäck2018). In this case, people will receive the information and decide whether to accept the tone of the political claims selected by journalists and editors (Eveland & Garret, Reference Eveland, Garret, Kenski and Jamieson2017; Zaller, Reference Zaller1992). In this respect, the influence of the media on public opinion should be directional: greater visibility of positive claims about immigration should lead the public to care less about this topic regardless of their predispositions (Bos et al., Reference Bos, Lecheler, Mewafi and Vliegenthart2016; Vliegenthart, Reference Vliegenthart, Weinar, Bonjour and Zhyznomirska2018). By contrast, an increase in negative claims about immigration should increase the proportion of individuals who judge this issue to be a top priority at the national level (McLaren et al., Reference McLaren, Boomgaarden and Vliegenthart2018). Against this background, the third empirical expectation is:

Tone of political claims:

a) An increase in the proportion of political claims with a positive tone on immigration leads to a decrease in the proportion of respondents who rank immigration among the most important issues facing their country.

b) An increase in the proportion of political claims with a negative tone on immigration leads to an increase in the proportion of respondents who rank immigration among the most important issues facing their country.

Data and methods

We test our argument using data from seven Western EU countries: Austria, Belgium, Ireland, the Netherlands, Spain, Portugal, and the UK. This country selection follows a most‐similar systems design.Footnote 2 First, these countries are post‐industrial OECD democracies, whose wealth attracts inflows of migrants while the liberal character of their states disapproves hate speech and grants protection to foreign citizens. Second, it consists of countries with relevant immigrant populations, namely foreign populations from non‐EU countries, which is a necessary condition for intensifying media coverage of this topic (Van der Brug et al., Reference Van der Brug, D'Amato, Ruedin and Berkhout2015, p. 196). Third, it only includes EU member states because they are generally subject to the integration of their immigration policies (Boswell & Geddes, Reference Boswell and Geddes2011). Thus, the process of Europeanisation has far‐reaching effects on national legislation of EU member states, which can influence media coverage on legislative developments concerning immigration unlike in non‐EU countries like Switzerland or Norway (Van der Brug et al., Reference Van der Brug, D'Amato, Ruedin and Berkhout2015).Footnote 3 Last, the date of accession of the selected cases precedes the departing point of our analysis and the enlargement processes observed in 2004, 2007 and 2013. Thereby, the Europeanisation effects were commonly observed in the selected cases during the time of our investigation.

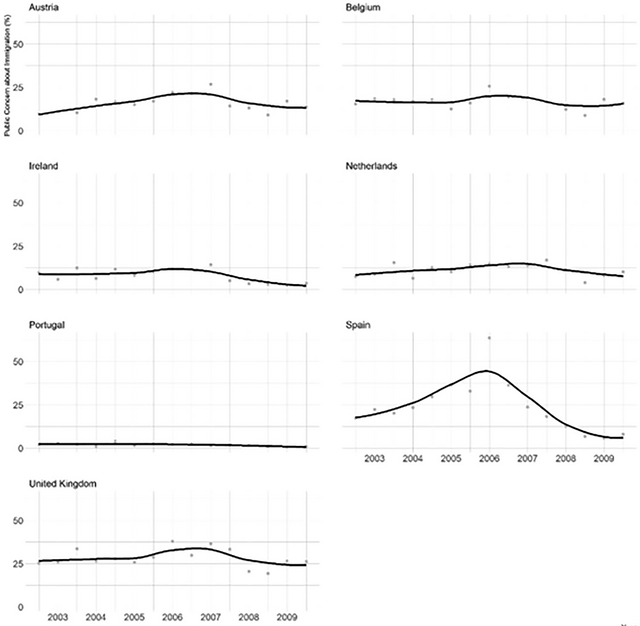

Despite these important similarities, the selected countries show different patterns of public concern about immigration (outcome variable; Figure 1).Footnote 4 Our analysis includes one country where the ranking of immigration was consistently high (over 25 per cent – the UK), two countries where it was moderate to high (12.5 to 25 per cent – Austria and Belgium), two countries where it was moderate to low (around 12.5 per cent – Ireland and the Netherlands), one where it was a latent issue (below 5 per cent – Portugal), and one country where it was a punctuated phenomenon (Spain). Similarly, in most of the countries selected there was significant variation in the importance attached to immigration at the national level. This variation is fundamental to the assessment of media effects on the outcome variable. Indeed, the country selection also includes countries where unexpected exogenous shocks related to immigration occurred during the selected period, like the assassination of Pim Fortuyn in the Netherlands, terrorist attacks in Spain and the UK, and migrant boat arrivals in the Canary Islands in Spain (see Supporting Information, Appendix A for additional details on the countries included in the analysis). In short, our country selection captures the strong heterogeneity observed across Western EU member states regarding public concern about this social phenomenon or the observation of exogenous shocks.

Figure 1. Public concern about immigration between 2002–2009.

Note: The solid line is the trend line (LOESS). The grey dots show the proportion of the population who consider ‘migration’ as one of the two most important issues facing their country. Source: European Commission, 2009.

Public concern about immigration is measured using the MII question included in the Eurobarometer surveys (question wording: ‘What do you think are the two most important issues facing [OUR COUNTRY] at the moment?’). This question was first asked in 2002 and requires respondents to select the two most important issues facing their country from a list of 14 political issues, ranging from the economy to health and education. The MII question in the Eurobarometer makes it possible to track changes in public opinion on the importance of immigration compared to other political topics every 6 months (Hatton, Reference Hatton2021).

Media data are used to measure the predictor variables. Empirically, we draw on the extensive content analyses by Van der Brug et al. (Reference Van der Brug, D'Amato, Ruedin and Berkhout2015) and Carvalho and Duarte (Reference Carvalho and Duarte2020) that systematically coded news article on migration. The content analyses included a random sample of 700 days for each country (including the two dominant language areas in Belgium) over a period of 15 years (1995–2009). For each selected country, all news articles related to immigration control and immigrant integration were extracted from two national newspapers: a quality paper and a tabloid (Supporting Information, Appendix B). The use of two different media sources should ensure a consistent analysis of the amount of news coverage on immigration and a heterogenous analysis of the political claims found in the news environment. While selection and description biases exist in the media, they are not problematic for the present analysis because we seek to measure these media effects – in terms of journalists’ ability to filter the political demands according to their journalistic criteria – on public concern about immigration.

In this analysis, the predictor variables for salience are the proportion of news, and the proportion of political claims about immigration (Supporting Information, Appendix B). Both variables correspond to the ratio between the number of news or political claims in a country in each semester, and the total number of news or political claims in a country during the total period of analysis. This operationalisation captures the variation of the salience of immigration‐related topics over time in each country (Supporting Information, Appendix C). Both the sampling of the news and the coding of the political claims were done manually by native speakers of the respective languages, using content analysis (see Van der Brug et al. (Reference Van der Brug, D'Amato, Ruedin and Berkhout2015) for the codebook).

Regarding the tone of political claims about immigration control and immigrant integration in the media, there are two separate predictor variables: the proportion of positive claims and the proportion of negative claims. Similar to the salience variable, these measures consist of the ratio between the number of positive or negative political claims and the number of claims with tone in the country and semester. Political claims with a positive or negative tone can be found in a single news report. In the original dataset, the tone of a political claim is classified as positive (showing openness towards immigrants, ranked as 1 and 0.5), neutral (0), or negative (suggesting restrictive positions, −0.5 and −1; Van der Brug et al., Reference Van der Brug, D'Amato, Ruedin and Berkhout2015; Supporting Information, Appendix C).Footnote 5

To estimate the impact of media effects on public concern about immigration, we use panel data analysis, because we have repeated observations over time. A panel can be generated by merging time‐series observations across a range of cross‐sectional units, such as countries, political parties or randomly sampled individuals. Here, we analyse seven Western EU member states over 15 semesters (2002–2009) yielding 105 observations. With the panel design, we can estimate variation both between and within countries. Considering the aim of this research and the results of the Hausman test, we assume that there is no correlation between the unique errors and the regressors in the models. Thus, the random effect model is preferred over a fixed effect model to estimate the impact of media effect on public concern about immigrationFootnote 6. Notwithstanding, fixed effects models – which account for time‐invariant omitted variables – produce comparable results to the random effects models (Supporting Information, Appendix D). Leave‐one‐out analyses show that the main results are not driven by a single case.

The outcome and predictor variables are calculated for each country‐semester. The choice of using semesterly data follows the agenda‐setting literature, which shows that media effects on the public agenda typically reflect patterns seen in the news in the preceding one or two months. Nonetheless, agenda‐setting effects are expected to be watered down in the period between 8 and 26 weeks (McCombs, Reference McCombs2014). We use a 24‐week lag, which is the shortest lag we could use given the outcome and predictor variables, and, thus, our analysis takes a conservative approach to finding media effects. In the analysis, we have selected Eurobarometer waves with fieldwork 6 months after the media data. This 6‐month lag between the volume of news and political claims of the immigration‐related topic in the media on the one hand, and with public concern about immigration on the other, allows testing the hypothesis that the former affects the latter. This strategy allows us to control for the potential problem of reverse causality and is consistent with the literature suggesting that citizens are poorly informed about immigration (Blinder & Jeannet, Reference Blinder and Jeannet2018). In the models, we use control variables to account for factors that may influence both the variation of the outcome and predictor variables. In particular, we control for the percentage of the foreign population, the number of asylum applications, general government deficit, GDP per capita, and unemployment. The data of the control variables come from the Organisation for Economic Co‐operation and Development (OECD) and, in the case of the number of asylum seekers, from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). These variables are measured annually.

Media coverage and public concern about immigration

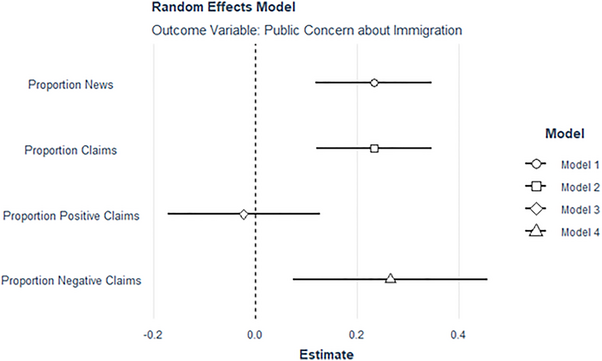

Figure 2 shows the results of the panel data analysis using random effect models (Supporting Information, Appendix D). In models 1 and 2, we examine the effect of the volume of news and political claims on public concern about immigration. The proportion of news (model 1) and claims (model 2) about immigration and integration is positively associated with immigration being ranked as an important issue. A one‐point increase of the standard deviation of the proportion of news and claims increases around 0.23 standard deviations of public concern about immigration. The substantive results are the same when using a fixed effects model (Supporting Information, Appendix D).

Figure 2. Media coverage and public concern about immigration, random effects models.

In models 3 and 4, we investigate the influence of the tone of political claims on the proportion of respondents who rank immigration among the MII facing their country. While the proportion of positive claims does not explain the variance in the importance associated with immigration by the public (model 3), the proportion of negative claims is significantly associated with a higher score for public concern about immigration (model 4). A one‐point increase in the standard deviation of the proportion of negative claims increases 0.26 standard deviations of public concern about immigration. These models do not consider other potential confounders that may influence both the dependent and independent variables under analysis.

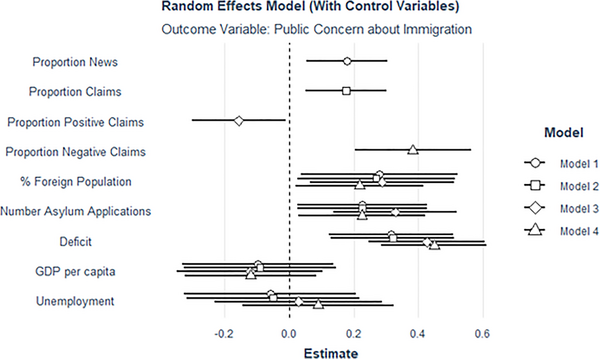

Figure 3 shows the effect of salience and tone of immigration‐related topics in the media on the electorate's ranking of immigration among the MII facing their country, controlling for other variables (Supporting Information, Appendix D). The interpretation of a significant role for the media holds after having taken into consideration other variables that may shape both the outcome and predictor variables. Notably, we include objective measures of migration stocks and economic performance – the share of the foreign population, the number of asylum applications, general government deficit, GDP per capita and unemployment rates. With the present analysis, we can clearly show that increasing media coverage of immigration is associated with an increase in the public's ranking of immigration among the MII facing the country: The media environment has agenda‐setting effects on public concern about immigration.

Figure 3. Media coverage and public concern about immigration, random effects models with control variables.

The media coverage of immigration in newspapers seems a good predictor of public concern about immigration: The volume of both news (model 1) and political claims (model 2) in national newspapers are good predictors of the electorate's ranking of immigration among the MII facing their country. In models 1 and 2, a one‐point increase of the standard deviation of the proportion of news and political claims increases by 0.18 standard deviations of the stated importance of migration. The substantive results are remarkably similar when using a fixed effects model (Supporting Information, Appendix D). These results suggest that salience of either form – object salience or attribute salience – matter for public concern about immigration.

In models 3 and 4, we estimate the effect of the tone of the political claims (positive or negative) on public concern about immigration, holding constant other variables on migration flows and the economic context. A higher proportion of positive claims is negatively associated with individuals’ perceived importance of immigration (model 3), while a higher share of negative claims is associated with the increase of the importance attached to immigration in comparison to other policy‐related issues (model 4). A one‐point increase in the standard deviation of the proportion of positive claims is associated with 0.16 standard deviations lower public concern about immigration, and a one‐point increase in the standard deviation of the proportion of negative claims with 0.26 standard deviations higher concern.

Robustness

To assess the validity and robustness of these results, we test for reverse causality (Supporting Information, Appendix E). The results indicate that changes in public concern about immigration do not predict changes in the media variables, mainly when using the proportion of news and political claims as outcome variables. Notwithstanding, public concern about immigration seems to be a good predictor of the proportion of negative claims, limiting causal interpretations in this case. We also perform a time‐reversed analysis (Supporting Information, Appendix F). The evidence shows that changes in public concern about immigration are not predicted by changes in the volume of news and claims and the proportion of positive claims. However, the results also suggest that the proportion of negative claims predicts public concern about immigration. Taken together, this evidence may indicate some drifting or measurement issues in the case of negative claims, although the general results hold.Footnote 7

We also perform leave‐one‐out analyses to ensure that the main results are not driven by one single case (Supporting Information, Appendix G). The results hold when each country is left out one at a time, except when using the proportion of positive claims as the main predictor. The main findings suggest that this variable only has a negative effect on public concern about immigration when other factors are controlled for. This effect holds when data from Belgium, Portugal, Spain and the UK are removed separately from the model. However, it becomes insignificant when each of the remaining countries (Austria, Ireland and the Netherlands) is removed one at a time (Supporting Information, Appendix G). This evidence limits the interpretation of the effect of positive claims on public concern about immigration.

Discussion and conclusion

Looking at media coverage of immigration in the 2000s, we show that the media environment appears to have a substantial influence over public concern about immigration in comparison to other topics. Notwithstanding the thesis of minimal media effects in much of the literature, the visibility of immigration in the print media was positively related to the ranking of immigration in the MII in seven Western EU countries. In our analysis, the media coverage of immigration has a relevant effect on temporal dynamics over a period of 7 years, without disaggregating the news content by issue such as crime or terrorism (McLaren et al., Reference McLaren, Boomgaarden and Vliegenthart2018). Remarkably, at an aggregate level, the effects of the media environment are very consistent across the public. Our aggregate analysis suggests that the effects of the news environment are transversal to the general electorate rather than focused on specific segments or dependent on the predispositions of the electorate (Lecheler et al., Reference Lecheler, Matthes and Boomgaarden2019).

Most existing studies focus on mass‐mediated communication to study the politicisation of immigration and simultaneously exclude the media as a potential predictor variable of public concern about immigration (Grande et al., Reference Grande, Schwarzbözl and Fatke2019; Hutter & Kriesi, Reference Hutter and Kriesi2021). Consequently, the politicisation of immigration has been strongly linked to the agency of political parties, especially radical right parties, and the patterns of interparty competition (Hadj Abdou et al., Reference Hadj Abdou, Bale and Geddes2022; Hutter & Kriesi, Reference Hutter and Kriesi2021). However, our results suggest that the media may not be a neutral actor in the politicisation of immigration. While the importance of opinion pieces by journalists and editors may be limited (Van der Brug et al., Reference Van der Brug, D'Amato, Ruedin and Berkhout2015), the work of journalists and editors in selecting articles about immigration and highlighting the topic has substantial repercussions on public concern about immigration. In this regard, further analysis should be undertaken to explain the variation in media coverage of immigration at the cross‐national level and to explore its role behind the emergence of the new ‘cultural cleavage’ at the European level.

While we cannot examine the content of the news articles included in the statistical analysis, previous research conducted in the Netherlands and Flanders (two of our cases) between 1999 and 2015 provides important insights. Jacobs et al. (Reference Jacobs, Damstra, Boukes and De Swert2018) highlighted the lack of a direct relationship between news coverage of immigration and real‐world indicators or societal developments. The media took a specific approach to immigration as a news issue, often highlighting topics related to group conflicts like crime and terrorism (Jacobs et al., Reference Jacobs, Damstra, Boukes and De Swert2018). In the UK, a national report on media coverage published in the early 2010s highlighted the recurrent negative and distorted discussion of asylum seekers in the media (Leveson, Reference Leveson2012). We believe that the development of the so‐called 2015 ‘refugee crisis’ did not alter these patterns, but our results suggest that the increased visibility of immigration in the media was most likely followed by an intensification of public concern about immigration. Since immigration is mostly a non‐obtrusive issue, the public's awareness of immigration‐related events at the national and international levels is likely to be mediated by the media coverage of the topic rather than derived from self‐experience.

In our view, the ideological characteristics of the electorate cannot be activated or influenced in the absence of cues in the media about the importance or meaning of immigration (Friedman, Reference Friedman2012). Moreover, we argue that if consistent effects can be found between media coverage of immigration and the level of public salience of this social phenomenon in general, this means that media effects can trump political predispositions towards immigration. Indeed, we focus on the importance attached to immigration rather than on public attitudes or policy preferences. The stability of political predispositions seems to diverge from the intense fluctuations in the level of public salience of immigration (Hatton, Reference Hatton2021). Indeed, in the autumn of 2006, 68 per cent of the Spanish respondents indicated immigration as the most important issue, but it seems unlikely that two‐thirds of the electorate shared ideological predispositions or agreed on why immigration was important (Ros & Morales, Reference Ros, Morales, Van der Brug, D'Amato, Ruedin and Berkhout2015).

Our results have important implications for the development of research on immigration politics and policy. Much of this political research is predicated on the gap hypothesis, which argues that a public backlash is fuelled by a significant and persistent gap between the policy inputs and outcomes of policy implementation on immigration control (Hollifield et al., Reference Hollifield, Martin and Orrenius2014). Here we suggest that variation in the importance attached to immigration relative to other policy issues is closely linked to media coverage of immigration, challenging the role of policy gaps. Put differently, our research suggests that the volume of news or political claims are perhaps more important to understand public concern about immigration than generally assumed in migration studies. From a theoretical perspective, increased media coverage of immigration and the subsequent expansion of public concern about immigration can potentially help the political parties that usually own the issue of opposition to this social phenomenon – far‐right parties (Damstra et al., Reference Damstra, Jacobs, Boukes and Vliegenthart2021; Mudde, Reference Mudde2019).

Following the thermostatic model of policy making, there are competing explanations for whether policymakers should ignore or follow public demands on immigration (Morales et al., Reference Morales, Pilet and Ruedin2015). Our finding, that public concern about immigration can be strongly related to media coverage, implies that the legislator's focus on policy developments may not capture a relevant dimension that shapes issue salience. While the implementation of restrictive legislation can have a strong influence on the nature and intensity of migration inflows (Czaika & de Haas, Reference Czaika and De Haas2013), it may still not mitigate the intense salience of immigration, because public judgments on the topic are not strongly influenced by actual migration flows – the number of asylum seekers does predict public concern about immigration, though. Our research suggests that the government's responsiveness to increasing the salience of immigration through the enactment of legislation will probably contribute to maintaining or even increasing the visibility of immigration in the media and the number of political claims with a negative tone (Van der Brug et al., Reference Van der Brug, D'Amato, Ruedin and Berkhout2015). This approach is likely to have counterproductive effects, leading to increased public concern about immigration.

We can identify three limitations of the present analysis that should be addressed in future research. First, the aggregated statistical approach prevents us from accounting for individual‐level confounding variables, such as individual social and political predispositions or voting for far‐right parties. Thus, we cannot explain variation in patterns of media coverage across the countries beyond the relatively broad control variables included, although we have little reason to believe that such predispositions change substantially over the course of a few months. Second, we note that a longer time frame may be important to confirm the overall conclusions of our study. This endeavour requires substantial effort to extend the cross‐national content analysis of the media coverage of immigration into the 2010s, although such research may need to account for the confounding influence of social media, which is now much more widespread. Third, further research is needed to explore the potential link between media coverage of immigration and the variation in behavioural measures such as the electoral support for radical right parties in Europe, hate crime or discrimination.

Our analysis suggests that an increasing volume of news and political claims about immigration in the news is associated with an expansion of the public's ranking of this social phenomenon relative to other policy‐related issues. The news environment can be an exogenous actor that can directly influence public concern about immigration – which is consistent with the top‐down elite approach – and its effects could be seen in the general electorate. Rather than following consumers’ preferences, media coverage of immigration seems to guide the electorate's perception of the importance attached to the topic. At the same time, research on the politics of international migration should explore the role of the media environment as a predictor variable, moving beyond the current exclusive focus on the agency of political parties, or the influence of policy gaps on immigration control. Future research should also explore the impact of the news environment on topics such as the emergence of the ‘cultural cleavage’, the electoral support for parties that own this issue, and the levels of hate crime.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the work and comments provided by: Erik Bleich, Elizabeth Carter, Charles Lees, Pedro Magalhães, James Deninson, Joanna Clifton‐Sprigg, Lenka Dražanová, Sabina Kubiciel‐Lodzinska, Sebastian Rinken, and the anonymous reviewers. Didier Ruedin has a secondary affiliation at the University of the Witwatersrand. Mariana Carmo Duarte was affiliated with the European University Institute when this article was submitted.

Data Availability Statement

Data and replication code available at https://osf.io/xjgny/

[Correction added on 11 May 2024, after first online publication: Data Availability Statement has been added in this version.]

Funding Information

João Carvalho was supported by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology under the grant:2021.02779.CEECIND/CP1694/CT0010

Mariana Carmo Duarte was supported by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology under the PhD grant SFRH/BD/150290/2019.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Supporting Information