“Only the BLACK WOMAN can say ‘when and where I enter…then and there the whole Negro race enters with me’.” – Anna Julia Cooper

“There’s always someone asking you to underline one piece of yourself—whether it’s Black, woman, mother, dyke, teacher, etc.—because that’s the piece that they need to key in to. They want to dismiss everything else.” – Audre Lorde

Introduction

During the fall of 2020, a colorful mural that read “Trust Black Women. Vote” was unveiled on a main thoroughfare in the historically African American community of Booker T. Washington Heights in Columbia, South Carolina (Rogers Reference Rogers2020). Sentiments that suggest Black women are uniquely positioned to steer American political thinking and behavior toward a more just, equitable, and democratic polity (Harris-Perry Reference Harris-Perry2011; Michener, Dilts, and Cohen Reference Michener, Dilts and Cohen2012) were a common refrain in progressive political circles, as Black women were pivotal to 2020 Democratic electoral victories (Igielnik, Keeter, and Hartig Reference Igielnik, Keeter and Hartig2021). Such a refrain was also echoed in the 2024 election with the Democratic presidential candidacy of Vice President Kamala Harris. As Black feminist political theorizing informs us, when we are mindful of the complexities of differing political and social identities (Collins Reference Collins2022), broader intersectional ideologies that center Black women as well as other marginalized groups provide even greater potential to advance a more progressive Black politics (Bunyasi and Smith Reference Bunyasi and Smith2019).

Research on American public attitudes toward same-sex marriage and LGBTQ+ communities often highlights how African Americans are consistently less supportive of LGBTQ+ rights when compared to Whites (Adamczyk, Boyd, and Hayes Reference Adamczyk, Boyd and Hayes2016; Glick and Golden Reference Glick and Golden2010; Lewis Reference Lewis2003). However, in this paper, we do not retread these important but well-worn lines of research inquiry to examine when and where African Americans are complicit in marginalizing LGBTQ+ communities. Instead, we ponder the opening quotes from proto-feminist educator and activist-scholar Anna Julia Cooper as well as queer feminist activist and poet Audre Lorde. Our unique aim is to examine how the intersections of varied dimensions of identity determine when and where African Americans stand in solidarity with LGBTQ+ communities. We lean into, rather than rail against, the ways “identity politics” can build mutually beneficial policy as well as electoral coalitions in Black and other communities (Nash Reference Nash2018). Our central question is: How do intersectional ideologies and experiences affect the extent to which African Americans support or oppose the marginalization of LGBTQ+ communities, including Black LGBTQ+ communities? This is a unique question in that we are not arguing that all intersectional lenses are the same, for such a claim would directly contradict the positionality insights of Black feminist theorizing (Aguayo-Romero Reference Aguayo-Romero2021). However, possibly due to the victories Black feminist leadership and activism have won within Black politics and political ideology, we assert that intersectional rationales are now more central to African American political thinking than may have previously been the case (Michener, Dilts, and Cohen Reference Michener, Dilts and Cohen2012). Using the Black respondent subsample of the 2016 Collaborative Multiracial Post-Election Study (CMPS), we innovate measures of intersectionality. We provide empirical assessments of the extent to which support for addressing challenges affecting Black women, broader intersectional ideologies, and experiences of marginalization explain opposition to the marginalization of LGBTQ+ communities among African Americans. While this paper does not fully employ all of the tools of the intersectionality paradigm (Hancock Reference Hancock2016; Nash Reference Nash2018), intersectionality theory greatly informs our theorizing about identity intersections and their ideological implications. In doing so, we provide an assessment of the opportunities as well as the challenges for intersectional consciousness and experiences to advance, or to impede, a more inclusive Black politics (Isoke Reference Isoke2014; Jordan-Zachery Reference Jordan-Zachery2017).

Black Politics and Marginalization Theory

In The Boundaries of Blackness (1999), Cathy Cohen demonstrates that in addition to confronting the fundamental political challenges posed by race-based intergroup marginalization—e.g., anti-Black racism and white supremacy—African American politics also contends with the elite, internal policing of intragroup behavior based upon dominant beliefs, norms, goals, and resources. Extending upon Black feminist and LGBTQ+ scholarship regarding “the politics of respectability” (Higginbotham Reference Higginbotham1992; Bunyasi and Smith Reference Bunyasi and Smith2019; Strolovitch and Crowder Reference Strolovitch and Crowder2018), Cohen argues that Black leaders overcompensate in their understandable concern with the racial marginalization of Black communities by purposefully relegating issues and constituencies within Black communities that these leaders believe will detract from a group agenda. Cohen asserts, “It is from such a conflictual position that we increasingly find traditional black elites engaging in their own indigenous form of marginalization – secondary marginalization – replicating a rhetoric of blame and punishment and directing it at the most vulnerable and stigmatized in their communities” (Cohen Reference Cohen1999, 27).

The exemplar issue Cohen examines to demonstrate her theory’s utility is Black leadership’s relegation of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Black communities, especially the “undeserving victims” of intravenous drug users and Black men who have sex with men (Cohen Reference Cohen1999, 27-28). Unlike traditional “studies of power,” Cohen explains that “the theory of marginalization…steps beyond the traditional dichotomy of powerful and powerlessness to examine the multiple sites where power is located…” (Cohen Reference Cohen1999, 36). Thus, it is possible for those who are marginalized in one dimension to marginalize others in another dimension. Cohen explains that while African Americans are marginalized by racism and white supremacy, it is also possible for LGBTQ+ persons, including those who self-identify as White, to experience the marginalization of homophobia or heterosexism by straight, cisgender, Black elected officials if these officials give wholly insufficient attention or resources toward addressing LGBTQ+ policy concerns (Cohen Reference Cohen1999, 343-345). Even though there are clear imbalances of power between Blacks and Whites, Cohen concludes “…it would be a mistake to categorize African-American communities as powerless…” (Cohen Reference Cohen1999, 345).

Scholars influenced by Cohen’s theory of marginalization (Hochschild and Weaver Reference Hochschild and Weaver2007; Fine Reference Fine2011; Shaw Reference Shaw and Georgia2011) have termed the patterns of intergroup marginalization that serve to benefit dominant groups as primary marginalization. Similarly, we refer to marginalization on the basis of sexual orientation—e.g., opposition to LGBTQ+ civil rights—as primary marginalization. We further argue that there are other, more subtle patterns of group-based thinking and behavior that underline and serve as antecedents to primary and secondary forms of marginalization.

Cohen asserts that secondary marginalization entails minoritized elites and mass publics embracing “the dominant discourse that defines what is good, normal, and acceptable” (Cohen Reference Cohen1999, 64). We contend that doing so suggests ideological distance within marginalized groups between those who promote and embrace this “dominant discourse” and groups who are marginalized (or secondarily marginalized) by it. Examples of this ideological distance include a lack of awareness of the secondarily marginalized group’s relative position in society and an accompanying unwillingness to advocate for the group’s interests—i.e., a lack of cross-group consciousness.

According to Miller et al. (Reference Miller, Gurin, Gurin and Malanchuk1981), group consciousness “involves identification with a group and a political awareness or ideology regarding the group’s relative position in society along with a commitment to collective action aimed at realizing the group’s interests” (1981, 495). Similarly, we conceive of cross-group consciousness as an awareness of a group’s social and political positionality coupled with a commitment to advocate on behalf of the group’s interests, despite not identifying with or being a member of the group. Put differently, it is akin to having linked fate with a group to which one does not belong. Just as group consciousness has long been known to bolster group-based collective action, we expect cross-group consciousness to bolster support for addressing challenges faced by marginalized groups (Hurwitz, Peffley, and Mondak Reference Hurwitz, Peffley and Mondak2015). Therefore, we posit that Black Americans who believe anti-LGBTQ+ discrimination is a significant problem and share a sense of linked fate with LGBTQ+ persons are also more supportive of LGBTQ+ civil rights and more likely to believe that Black LGBTQ+ persons merit prominent consideration within Black politics (Boykin Reference Boykin1996; Bunyasi and Smith Reference Bunyasi and Smith2019).

Motivated by Cohen’s theory of marginalization and research on group consciousness, we examine the factors that predict Black respondents’ opposition to the primary marginalization of LGBTQ+ communities as well as the secondary marginalization of Black LGBTQ+ subgroups and the antecedents of such marginalization (i.e., cross-group consciousness). To do so, we build upon research that suggests an awareness of the identity and positionality of Black women and other marginalized Black subgroups provides a useful though not singular lens through which Black Americans may embrace LGBTQ+ rights and communities.

Trust Black Women: Intersectionality and Identity Theory

Due in part to intersecting experiences of race-based and gender-based marginalization, Black feminist theorizing has long held that Black women have a unique and complex set of experiences with discrimination (Higginbotham Reference Higginbotham1992; Carby Reference Carby1987; Collins Reference Collins1989; Giddings Reference Giddings2014; Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1990). In 1977, the radical Black feminist and lesbian activists who authored the “Combahee River Collective Statement” provided the following foundational thinking, “The most general statement of our politics at the present time would be that we are actively committed to struggling against racial, sexual, heterosexual, and class oppression, and see as our particular task the development of integrated analysis and practice based upon the fact that the major systems of oppression are interlocking. The synthesis of these oppressions creates the conditions of our lives” (Collective 1983, 272). Roughly, a decade later, Kimberlé Crenshaw’s (1989; Reference Crenshaw1990, 1244) “intersectionality” theory reiterated this view that Black women’s multiple layers of identity and life chances are in part determined by the layers of systemic and structural privilege or disadvantage that power structures associate with those identities (Heard Harvey and Ricard Reference Heard Harvey and Ricard2018; Hindman Reference Hindman2011; Michener, Dilts, and Cohen Reference Michener, Dilts and Cohen2012; Crowder Reference Crowder2020). As Crenshaw asserts, “…many of the experiences Black women face are not subsumed within the traditional boundaries of race or gender discrimination as these boundaries are currently understood, and that the intersection of racism and sexism factors into Black women’s lives in ways that cannot be captured wholly by looking at the race or gender dimensions of those experiences separately” (Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1990, 1244). Similarly, Patricia Hill Collins defines intersectionality as “an analysis claiming that systems of race, economic class, gender, sexuality, ethnicity, nation, and age form mutually constructing features of social organization” (Collins Reference Collins1998, 278). Julia Jordan-Zachery reiterates the positionality imposed by power structures in stating, “Intersectionality takes into account how multiple forms of oppression, race, class, gender and sexuality inform the lived realities of Black women and women of color” (Jordan-Zachery Reference Jordan-Zachery2017, 12).

Therefore, intersectionality theory is very instructive to our thinking as it evolves out of the earlier “identity politics” formulations of the Combahee River Collective (CRC). Throughout this paper, we draw upon insights from intersectionality theory in conceptualizing and using the terms of intersectional identities, ideologies, and experiences. However, our analysis is guided much more by identity theory as opposed to intersectionality theory for two principal reasons. First, our theorizing about Black women and other intersectional identities, ideologies, and experiences directly parallels the CRC’s classic argument that those who embrace what we call cross-group consciousness are at least moderately, “committed to struggling against racial, sexual, heterosexual [and/or] class oppression,” and thus perceive that, “…the major systems of oppression are interlocking” (Collective 1983, 272).

Second, intersectionality theory is a paradigm that entails not only analyses of how complex identities or positionalities can serve as political lenses, but this theory calls for the examination of the larger power structures—e.g., policies, laws, political or economic systems, etc.—that frame these identities/positionalities. It is a framework that centers the voices of the marginalized and demands diagnoses of how communities can resist and overturn their marginalization (Nash Reference Nash2018; Collins Reference Collins2019). Our analyses center the voices of Black Americans and examine how intersectional ideologies and experiences bolster cross-group consciousness with LGBTQ+ communities and opposition to their marginalization. We believe this is a unique and vital contribution to the literature of Black politics (Bunyasi and Smith Reference Bunyasi and Smith2019). However, an analysis of the larger power structures that frame or create these identities and their positionalities exceeds the scope of our examination.

The Political Derivatives of Positionality: Intersectional Ideologies and Experiences

Hall provides the insight, “identity is not a matter of essence but of positioning, and hence there is always a politics of identity, a politics of position and positionality” (Hall Reference Hall2017, 130; Harcourt Reference Harcourt2022). Correspondingly, one of our central assumptions is that systems of hierarchy have distinct ideological outgrowths, which are the belief systems individuals derive from their positionalities (King Reference King1988; Strolovitch Reference Strolovitch2012). Identity and ideology are connected through such systems. Inspired by a wealth of multidisciplinary thinking and research on ideology (Fields Reference Fields1990; Hinich and Munger Reference Hinich and Munger2010; Smedley Reference Smedley2018; Feagin and Ducey Reference Feagin and Ducey2018; Dawson Reference Dawson2001; Carmines and D’Amico Reference Carmines and D’Amico2015), we view ideology as a belief system or worldview organized around a consistent set of principles, ideas, and beliefs that make prescriptive and proscriptive demands on thinking and behavior. Intersectional ideologies involve a person’s thinking and reasoning being influenced by intersecting marginalized identities (Nash Reference Nash2008; Strolovitch Reference Strolovitch2012); and we regard those whose thinking and reasoning are influenced by more intersecting marginalized identities as having broader intersectional ideologies than those whose thinking and reasoning are influenced by fewer. Yet, according to identity theory, a person can have a broad intersectional ideology even if they themselves do not embody certain intersectional identities (Cho, Crenshaw, and McCall Reference Cho, Crenshaw and McCall2013; Hindman Reference Hindman2011; Grabham et al. Reference Grabham, Cooper, Krishnadas and Herman2008). For example, it is possible for Black men to be Black feminists even though they do not self-identify as women (Neal Reference Neal2015)—a prospect that some activists have suggested since the late 1970s Black feminist movement (Collective 1983).

Although a person’s positionality can affect their ideology, we believe intersectional experiences of marginalization are distinct from intersectional ideology. Each can have discrete effects on political attitudes and behavior. Intersectional experiences of marginalization refer to the actual experiences of discrimination and devaluation that occur because of one’s interconnected marginalized identities. For Black women, this may at least entail compounded experiences of racism, sexism, and misogyny. For Black LGBTQ+ persons, this may at least entail compounded experiences of racism, homophobia, and heterosexism. What is most vital is that to have intersectional experiences, one must embody or be perceived to embody multiple, intersecting marginalized identities.

Social psychology research conducted among American racial/ethnic minority groups has demonstrated that interpersonal experiences of discrimination are associated with more positive attitudes toward LGBTQ+ groups (Craig and Richeson Reference Craig and Richeson2014). As stated by Craig and Richeson (Reference Craig and Richeson2014), “personal experiences of discrimination may better promote sympathy and/or perceived commonality with other disadvantaged groups” (p. 174). Hence, we expect that intersectional experiences of marginalization will be associated with increased cross-group consciousness within LGBTQ+ communities.

Conversely, interpersonal experiences with discrimination have also been shown to undermine political engagement (Oskooii Reference Oskooii2016, Reference Oskooii2020). As explained by Oskoii (2020), individuals who have experienced interpersonal discrimination, “due to persistent experiences of interpersonal rejection, may not be as enthusiastic as their counterparts to expend their limited resources on mainstream political processes.” In fact, some may “acquiesce to unjust social conditions and desist from advocating needed reforms because they assume that the majority of their peers disagree with them and that little can be gained from expressing their dissatisfaction” (pp. 872-873). Hence, one consequence of interpersonal experiences of discrimination may be increased feelings of connectedness to LGBTQ+ communities and awareness of LGBTQ+ political issues (i.e., increased cross-group consciousness with LGBTQ+ communities). Another consequence, however, is that intersectional experiences of marginalization may undermine a person’s willingness to advocate for LGBTQ+ issues and communities, possibly due to preoccupation with their own marginalization experiences.

African American Attitudes about LGBTQ+ Issues and Communities

Informed by Cohen’s marginalization theory, we regard bans against same-sex marriage as examples of primary marginalization of LGBTQ+ persons. Like Jim Crow segregation laws against African Americans, such bans are state-sanctioned forms of group-based discrimination (Cohen Reference Cohen1999, 39, 42). In 2005, ten years prior to the Obergefell v. Hodges (2015) decision, which ruled that same-sex couples have a constitutional right to marry, a Pew Research Center study found that only 36 percent of Americans overall, and 27 percent of Black Americans in particular, were in favor of allowing same-sex couples to legally marry (Pew 2015). However, after President Obama endorsed same-sex marriage in 2012, framing it as an issue of equality and fairness, increasing numbers of African Americans supported same-sex marriage or opposed constitutional bans against it, even if majorities of African Americans had personal, religious, or moral objections to homosexuality (Bunyasi and Smith Reference Bunyasi and Smith2019; Lewis Reference Lewis2003). Obama had previously expressed cross-group consciousness with LGBTQ+ persons. For example, in affirming his support for strong civil unions that provide the same rights as opposite-sex marriage while campaigning for the Democratic Party’s nomination for president, Obama commiserated, “When you’re a black guy named Barack Obama, you know what it’s like to be on the outside.” Also, in 2010, when indicating that his views of same-sex marriage were evolving, Obama invoked the experiences of friends and staff members who were in committed, monogamous same-sex marriages and were raising children. Hence, we expect that invoking cross-group consciousness with LGBTQ+ persons may have been among the mechanisms underlying Obama’s presumed influence on increased opposition to the primary marginalization of LGBTQ+ communities among Black Americans. It is also important to note that Black LGBTQ+ persons share many of the same policy goals as their cisgender, heterosexual counterparts—e.g., increased minimum wage, police accountability, affordable healthcare, and affordable housing (Lab 2020, 6-9). Hence, the secondary marginalization of Black LGBTQ+ communities also undermines the prospects for mass Black solidarity and collective action relative to policy priorities that serve the larger Black community.

Research has found that (holding socioeconomic factors constant) not only do Black women politically participate at higher levels than do Black men as well as other race-gender categories (Farris and Holman Reference Farris and Holman2014), but also Black women are ideologically more liberal than Black men on a range of social and policy questions (Lizotte and Carey Jr Reference Lizotte and Carey2021). This includes Black women’s greater acceptance of same-sex marriage as well as of lesbians and gay men (Lemelle Jr and Battle Reference Lemelle and Battle2004; Bunyasi and Smith Reference Bunyasi and Smith2019; Battle and Lemelle Jr Reference Battle and Lemelle2002). We hypothesize that these unique perspectives and experiences broaden Black women’s political lenses in ways that lead to increased support for the rights of other marginalized groups (Simien and Clawson Reference Simien and Clawson2004). In this regard, identity matters because Black women have fundamentally intersectional identities, which we believe may explain their greater support for LGBTQ+ issues compared to Black men. However, we contend that the perspectives and experiences that derive from intersecting marginalized identities are not limited to those who have intersecting marginalized identities. To reiterate, we believe that the political lenses of Black men can also be shaped by the perspectives and experiences that derive from intersecting marginalized identities, even when they themselves do not have such identities.

A Summary of our Framework

Before proceeding to our hypotheses and data analyses, we clarify our thinking on how Black opposition to primary and secondary LGBTQ+ marginalization is related to a respondent’s (1) support for Black women, (2) their embrace of broader intersectional ideologies, and (3) their intersectional marginalization experiences. Again, research reveals that Black women are more likely than Black men to have positive attitudes toward gay men and lesbians (Bunyasi and Smith Reference Bunyasi and Smith2019; Battle and Lemelle Jr Reference Battle and Lemelle2002; Lemelle Jr and Battle Reference Lemelle and Battle2004). One possible reason for this difference is that the race-gender intersections of Black women’s identities help to shape the perspectives of Black women, and, in turn, Black women are likely to be sympathetic to others who confront forms of gendered marginalization (Simien and Clawson Reference Simien and Clawson2004). Yet, identity theorists (Harnois Reference Harnois2010; Neal Reference Neal2015) find no empirical evidence for the claim that Black women are any more likely than Black men to embrace an understanding of Black women’s intersectionality. Hence, it is imperative that we examine among Black women and Black men if support for addressing the challenges faced by Black women contributes to a unique political consciousness whereby individuals are more likely to oppose the primary and secondary marginalization of LGBTQ+ communities, as well as the antecedents of such marginalization. Further, we find no compelling theoretical reason to expect that embracing an understanding of intersectionality affects the political consciousness of Black women differently than it does Black men.

Of critical importance in understanding Black receptivity to LGBTQ+ rights and communities is whether sympathy toward Black women (Gay and Tate Reference Gay and Tate 1998 ; King Reference King 1988 ) is qualitatively different from sympathy toward the intersections of multiple marginalized identities. Given the intellectual value of this distinction, we consider the differences between an additive Black intersectional ideology and an orientation that focuses only on the challenges affecting Black women. We concede that intersectionality is not simply an additive or multiplicative identity process. Again, by definition, not all intersectional lenses are the same because each is unique to the complex identities that form them. (Jordan-Zachery Reference Jordan-Zachery2017; Miller Reference Miller2018). However, our additive measure of Black intersectional ideology is composed entirely of measures of support for addressing the challenges faced by Blacks with intersecting marginalized identities—e.g., Black women, Black formerly incarcerated persons, Black undocumented immigrants, Black lesbian, gay, and transgender persons. Hence, this additive measure allows us to test whether those whom we contend have broader intersectional ideologies—i.e., those whose thinking and reasoning are influenced by more intersecting marginalized identities—are also more likely to oppose the primary and secondary marginalization of LGBTQ+ communities. We can also test whether those with broader intersectional ideologies are more likely to oppose the antecedents of such marginalization as compared to those whose thinking and reasoning are influenced by fewer intersecting marginalized identities.

We also consider the role of additive experiences of marginalization among Blacks, as in discrimination based on multiple identity dimensions. As aforementioned, we believe intersectional experiences are qualitatively different from intersectional ideology and, hence, will exert different effects on opposition to the marginalization of LGBTQ+ communities. Consistent with existing research on how interpersonal experiences with discrimination affect social and political behavior (e.g., Craig and Richeson Reference Craig and Richeson2014; Oskooii Reference Oskooii2016, Reference Oskooii2020), we expect that intersectional marginalization experiences among Black Americans will be associated with their increased cross-group consciousness with LGBTQ+ communities, yet decreased opposition to primary and secondary LGBTQ+ marginalization. Given that intersectionality theory suggests that the various components of individual identity, such as race, gender, and sexuality, cannot and should not be treated as discrete, mutually exclusive categories of experience or analysis (Crenshaw 1989), we regard experiences of marginalization on the basis of multiple marginalized identities as a proxy for intersectional experiences.

In addition to our primary independent variables (support for addressing challenges affecting Black women, Black intersectional ideology, and intersectional experiences of marginalization), other factors that may influence African American attitudes toward LGBTQ+ issues and communities include: Black linked fate (Cohen et al. 2018), education (Irizarry and Perry Reference Irizarry and Perry2018), political ideology and partisanship (Irizarry and Perry Reference Irizarry and Perry2018; Bunyasi and Smith Reference Bunyasi and Smith2019), and church attendance (Heard Harvey and Ricard Reference Heard Harvey and Ricard2018; Ledet Reference Ledet2017; Walsh Reference Walsh2016; Irizarry and Perry Reference Irizarry and Perry2018). We also anticipate that knowing a person who is LGBTQ+ and being LGBTQ+ self-identified are significant predictors of African Americans’ opinions about LGBTQ+ issues and communities (Rutledge et al. Reference Rutledge, Jemmott, O’Leary and Icard2018; Pastrana Jr Reference Pastrana2016; Harris Reference Harris2009). We control for each of these factors.

Hypotheses

Based on our theoretical narrative, we hypothesize the following relationships:

H1 Gender Differences: Black women will exhibit greater (A) cross-group consciousness with LGBTQ+ communities, (B) opposition to the primary marginalization of LGBTQ+ communities, and (C) opposition to the secondary marginalization of Black LGBTQ+ communities than Black men.

H2 Centrality of Support for Black Women: Black respondents who more strongly support addressing challenges affecting Black women will exhibit greater (A) cross-group consciousness with LGBTQ+ communities, (B) opposition to the primary marginalization of LGBTQ+ communities, and (C) opposition to the secondary marginalization of Black LGBTQ+ communities.

H3 Primacy of Intersectional Ideology: Black respondents who have broader intersectional ideologies will exhibit greater (A) cross-group consciousness with LGBTQ+ communities, (B) opposition to the primary marginalization of LGBTQ+ communities, and (C) opposition to the secondary marginalization of Black LGBTQ+ communities.

H4 Conflicting Effects of Intersectional Experiences: Intersectional experiences of marginalization will have conflicting effects on African Americans’ cross-group consciousness with LGBTQ+ communities and opposition to the primary and secondary marginalization of LGBTQ+ communities. African Americans who have had more intersectional experiences of marginalization will exhibit (A) greater cross-group consciousness with LGBTQ+ communities, yet also exhibit (B) less opposition to the primary marginalization, and (C) less opposition to the secondary marginalization of Black LGBTQ+ communities.

As stated previously, existing empirical and theoretical evidence does not suggest that Black women are more likely than Black men to embrace an understanding of intersectionality or that intersectionality affects the political consciousness of Black women and Black men differently. Hence, we do not hypothesize interactive relationships.

Data and Measures

We test our hypotheses using the 2016 CMPS, conducted by principal investigators Matt A. Barreto, Lorrie Frasure, Edward D. Vargas, and Janelle Wong. It included a sample of 10,145 respondents and was a self-administered instrument fielded between December 3, 2016, and February 15, 2017. The final sample was comprised of respondents who self-identified according to the following ethnic/racial categories: 3,003 Latinos; 3,102 Blacks; 3,006 Asians; and 1,034 White, non-Hispanics (Barreto et al. Reference Barreto, Frasure-Yokley, Vargas and Wong2017). We use only the Black subsample for these analyses.Footnote 2

Measurement, coding, and frequency distributions for all dependent variables and the primary independent variables used in the analyses presented herein appear in Tables 1 and 2. See the Supplemental Appendix for measurement, coding, and frequency distributions of control variables as well as supplemental analyses.

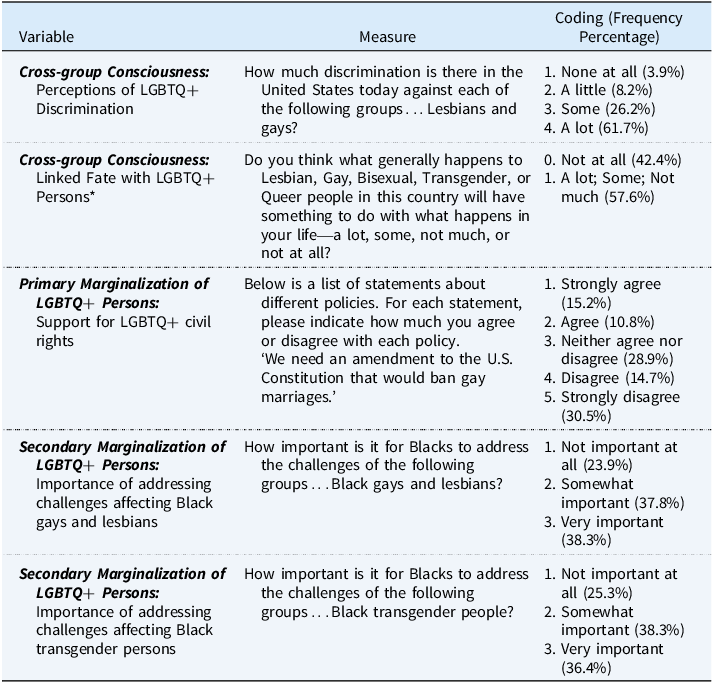

Table 1. Measurement and coding of dependent variables

* Due to its highly skewed distribution of responses, this question was recoded to a dichotomous variable, to indicate (1) having linked fate with LGBTQ+ persons versus (0) having no linked fate with LGBTQ+ persons.

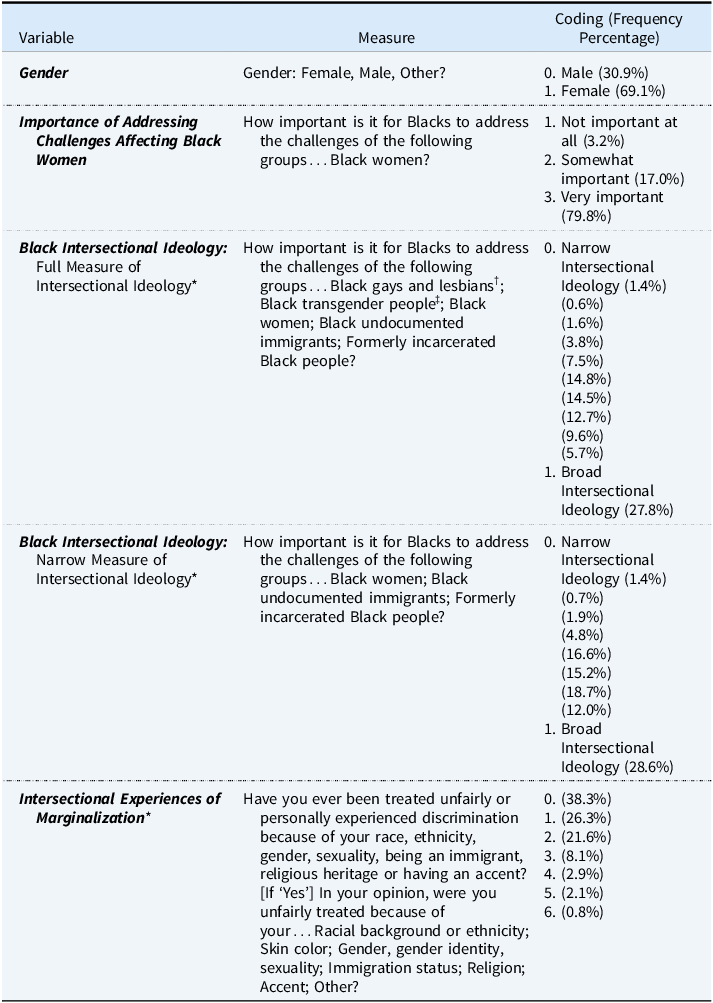

Table 2. Measurement and coding of primary independent variables

* Additive index. See Supplemental Appendix for frequency distributions of the component variables.

† Excluded from Full Measure of Intersectional Ideology in models predicting the secondary marginalization of Black gays and lesbians.

‡ Excluded from Full Measure of Intersectional Ideology in models predicting the secondary marginalization of Black transgender people.

Dependent Variables

To operationalize the extent to which African Americans exhibit cross-group consciousness with LGBTQ+ communities, we use measures of perceptions of LGBTQ+ discrimination and linked fate with LGBTQ+ persons. The CMPS contained one question that measured support for LGBTQ+ civil rights, which asked respondents whether they agreed or disagreed with the statement: “We need an amendment to the U.S. Constitution that would ban gay marriages.” This question is used to operationalize the extent of support or opposition to the primary marginalization of LGBTQ+ persons. To operationalize the extent of Black support or opposition to the secondary marginalization of Black LGBTQ+ persons, we use measures of the extent to which Black respondents feel it is important to address challenges affecting Black gays and lesbians and Black transgender persons.

Independent Variables

Importance of addressing challenges affecting Black women was measured using a question that directly asked respondents how important it is for Blacks to address challenges affecting Black women; and Black intersectional ideology was measured by creating an index of responses to questions that asked respondents how important it is for Blacks to address the challenges of five different Black intersectional identity groups—Black gays and lesbians, Black transgender people, Black women, Black undocumented immigrants, and formerly incarcerated Black people (α = 0.8004)—heretofore referred to as the full measure of intersectional ideology (FMI). Because responses to these questions ranged from one to three (1-Not important at all, 2-Somewhat important, and 3-Very important), the index of responses ranged from five to 15 but was rescaled to range from zero (narrow intersectional ideology) to one (broad intersectional ideology). We constructed a second measure of intersectional ideology that excluded the items that asked how important it is for Blacks to address the challenges of Black gays and lesbians and Black transgender people. This more restrictive index—composed only of the items measuring how important it is for Blacks to address the challenges of Black women, Black undocumented immigrants, and formerly incarcerated Black people (α = 0.7017), heretofore referred to as the narrow measure of intersectional ideology (NMI)—ranged from three to nine but was rescaled to range from zero (narrow intersectional ideology) to one (broad intersectional ideology).

In addition to the internal consistency suggested by their alpha coefficients, separate factor analyses further indicate that the items included in our measures of intersectional ideology comprise single, empirically distinct constructs. The eigenvalues and screen test results for each of the two factor analyses strongly indicate the existence of only one factor underlying the items that comprise the FMI and only one factor underlying the items that comprise the NMI.Footnote 3 We also found, however, that using these underlying derived factors as measures of the FMI and NMI in our statistical models did not yield substantively different results from the additive measures of the FMI and NMI in predicting each of our dependent variables. This provides further confirmation of the utility of our additive measures of Black intersectional ideology, which we use as predictors in each of the models presented herein.Footnote 4

Intersectional experiences were measured using a count of the number of identities for which respondents indicated having been discriminated against. We defined intersectional experiences of marginalization as having been discriminated against for two or more identity features.Footnote 5 As indicated above, in each of the models presented herein, we also controlled for factors that are known to be predictors of Black political attitudes pertaining to LGBTQ+ issues and groups, including linked fate with African Americans, political ideology, knowing someone who identifies as LGBTQ+, personally identifying as LGBTQ+, age, education, and church attendance, as well as voter registration and nativity.Footnote 6

Analyses and Results

Cross-Group Consciousness with LGBTQ+ Communities

To test our hypotheses that (H1A) African American women and African Americans who have (H2A) stronger support for addressing challenges affecting Black women, (H3A) broader intersectional ideologies, and (H4A) more intersectional experiences of marginalization would all exhibit more cross-group consciousness with LGBTQ+ communities, we estimated regression models predicting perceptions of discrimination against lesbians and gays and linked fate with LGBTQ+ persons. We estimated separate models with each of the two intersectional ideology measures to confirm that the breadth of one’s intersectional ideology is significantly related to cross-group consciousness with LGBTQ+ communities, even when LGBTQ+ identities are excluded from the measure. Also, given that we included the importance of addressing challenges affecting Black women in our measure for Black intersectional ideology, we estimated separate models to examine the effects of these measures independently and avoid multicollinearity.

As indicated in Table 3 and illustrated in Figure 1, consistent with H1A, Black women are more likely than Black men to exhibit cross-group consciousness with LGBTQ+ communities. Black women are more likely than Black men (by roughly 14 percent) to believe that gays and lesbians face a lot of discrimination, and Black women are higher in linked fate with LGBTQ+ persons than Black men, though the differences in linked fate did not achieve statistical significance in the model that includes the FMI.

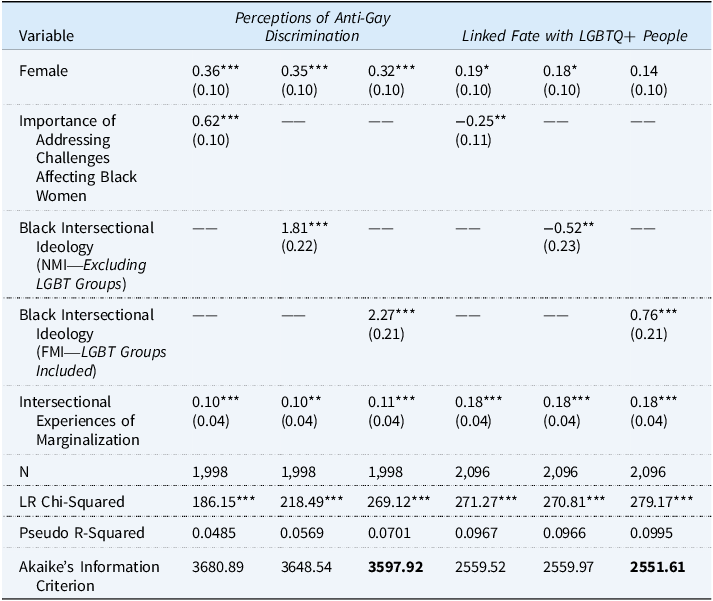

Table 3. Cross-group consciousness with LGBTQ+ communities: ordered logistic regression results predicting perceptions of discrimination against gays & lesbians and logistic regression results predicting linked fate with LGBTQ+ persons

*** p < .01 (two-tailed test) ** p < .05 (two-tailed test) * p < .10 (two-tailed test).

Note: Perceptions of Discrimination Against LGBTQ+ Persons ranges in value from 1 (none at all) to 4 (a lot). Linked fate with LGBTQ+ persons was recoded to a dichotomous variable where 1 indicates having linked fate with LGBTQ+ persons (a lot, some, and not much) and 0 indicates not having any linked fate with LGBTQ+ persons (not at all). Importance of Addressing Challenges Affecting Black Women ranges in value from 1 (not important at all) to 3 (very important). Black Intersectional Ideology ranges in value from 0 to 1, where higher values indicate having a broader Black Intersectional Ideology. All models include controls for linked fate with African Americans, political ideology, personally identifying as LGBTQ+, knowing someone who identifies as LGBTQ+, age, education, church attendance, voter registration, and nativity. Coefficients are unstandardized. Standard error estimates are in parentheses.

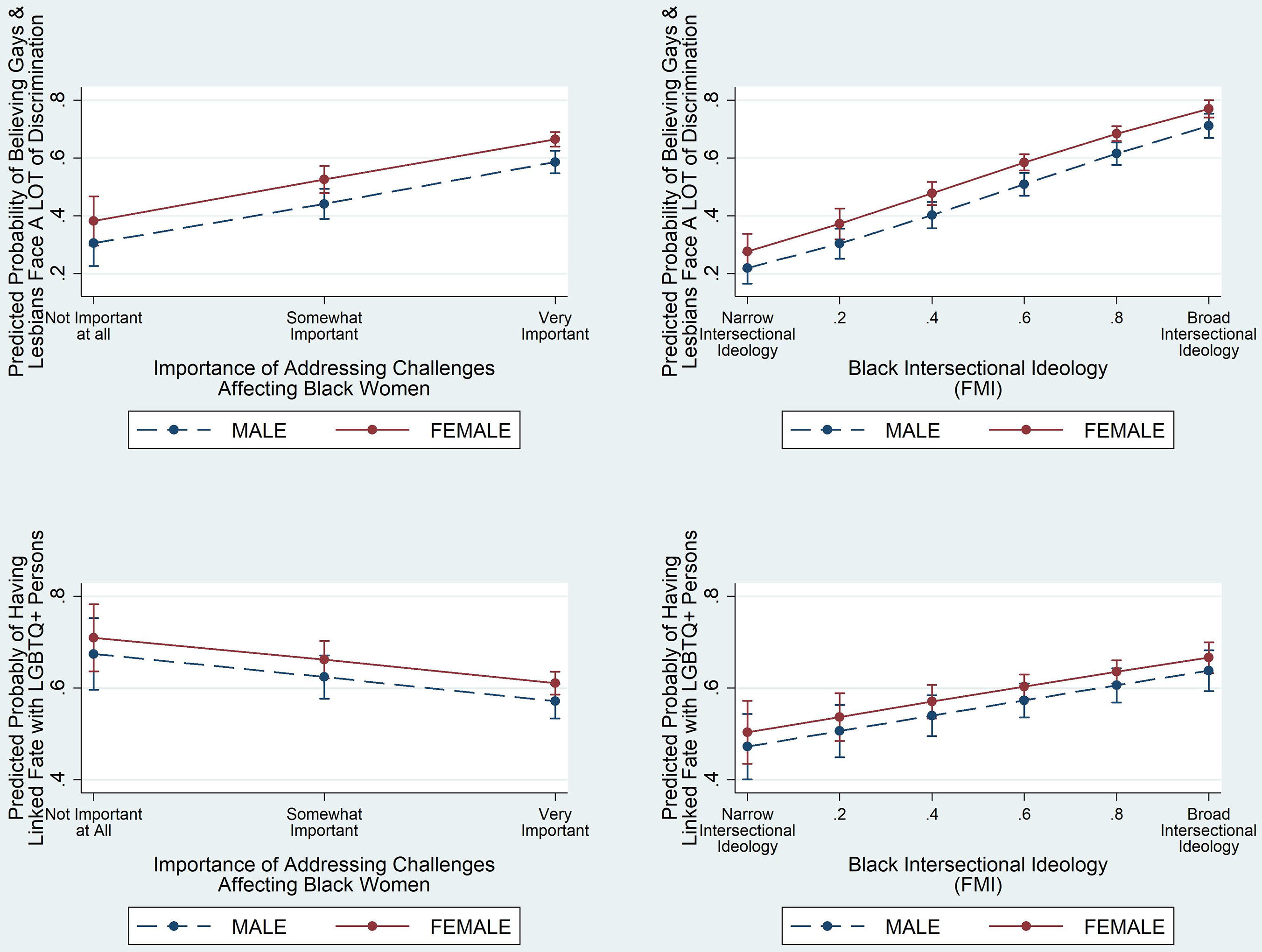

Figure 1. Cross-Group consciousness with LGBTQ+ communities by importance of addressing challenges affecting black Women and black intersectional ideology.

As illustrated in the top panels of Figure 1, respondents with stronger support for addressing challenges affecting Black women as well as those with broader intersectional ideologies were significantly more likely to report feeling that gays and lesbians face a lot of discrimination. The models that include intersectional ideology, however, were superior predictors of perceptions of discrimination against gays and lesbians when compared to the model that includes importance of addressing challenges affecting Black women only (e.g., Akaike’s Information Criterion [AIC] = 3680.885 versus AIC = 3648.544 and AIC = 3597.916, for the models including the NMI and the FMI, respectively). Black women and men who feel it is “very important” to address challenges affecting Black women were 74 percent more likely and 92 percent more likely, respectively, than those who feel it is “not important at all” to address challenges affecting Black women to say that gays and lesbians face a lot of discrimination. Yet, Black women and men with the broadest intersectional ideologies, as measured by the FMI, are more than twice as likely (177% more likely) and more than three times more likely (223% more likely), respectively, to say that gays and lesbians face a lot of discrimination, when compared to those with the narrowest intersectional ideologies. Also, Black women and men with the broadest intersectional ideologies were 15.8 percent more likely and 21.4 percent more likely, respectively, than those with the strongest support for addressing challenges affecting Black women to say that gays and lesbians face a lot of discrimination.

Interestingly, as illustrated in the bottom left panel of Figure 1, support for addressing challenges affecting Black women has a negative relationship to LGBTQ+ linked fate. Those who feel it is “very important” to address challenges affecting Black women are roughly 15 percent less likely than those who feel it is “not important at all” to address challenges affecting Black women to report having linked fate with LGBTQ+ persons. As with our previous models, however, it again appears that intersectional ideology, when measured with the FMI, is a superior predictor of linked fate with LGBTQ+ persons when compared to support for addressing challenges affecting Black women. Though the AIC is roughly the same for the models that include support for addressing challenges affecting Black women and the NMI (AIC = 2559.516 and AIC = 2559.974, respectively), the model that includes the FMI has the lowest AIC of the three models, as presented in the last column of results in Table 3. When measured with the FMI, intersectional ideology is both statistically significant and signed in the predicted direction. So Black respondents with broader intersectional ideologies are significantly more likely than those with narrower intersectional ideologies to report having linked fate with LGBTQ+ persons. As illustrated in the bottom right panel of Figure 1, Black women and men with the broadest Black intersectional ideologies are roughly 32 percent more likely and 35 percent more likely than those with the narrowest intersectional ideologies to indicate having linked fate with LGBTQ+ persons.

It is worth noting, however, that the predicted effect of intersectional ideology on linked fate with LGBTQ+ persons appears to be driven by respondents’ support for addressing challenges affecting Black gays and lesbians and Black transgender persons. If these two variables are removed from the index for intersectional ideology, as they are when intersectional ideology is measured with the NMI, then there is a statistically significant negative relationship between intersectional ideology and linked fate with LGBTQ+ persons. When measured with the NMI, respondents with the broadest intersectional ideologies are around 15 percent less likely than those with the narrowest intersectional ideologies to indicate having linked fate with LGBTQ+ persons. These results suggest that having a broader intersectional ideology that explicitly includes recognition of the importance of addressing challenges facing Black LGBTQ+ persons bolsters linked fate with LGBTQ+ persons. But having a narrower intersectional ideology that only includes recognition of the importance of addressing challenges facing other marginalized Black subgroups undermines linked fate with LGBTQ+ persons.

Intersectional experiences of marginalization are also significantly related to our two measures of cross-group consciousness—perceptions of discrimination against gays and lesbians and linked fate with LGBTQ+ persons. As indicated in Table 3, Black respondents with the highest number of intersectional experiences of marginalization were over 20 percent more likely to report that gays and lesbians face a lot of discrimination and over 30 percent more likely to report having linked fate with LGBTQ+ persons when compared to those with no intersectional experiences of marginalization, which is consistent with our predictions in hypothesis H4A.

Primary Marginalization of LGBTQ+ Persons

To test our hypotheses that (H1B) African American women and African Americans who have (H2B) stronger support for addressing challenges affecting Black women and (H3B) broader Black intersectional ideologies would be more opposed to the primary marginalization of LGBTQ+ communities, while those with (H4B) more intersectional experiences of marginalization would be less opposed, we estimated ordered logit models predicting the extent to which respondents agreed or disagreed that a Constitutional ban on gay marriage is needed. As with our previous analyses, we estimated separate models examining the effects of support for addressing challenges affecting Black women and Black intersectional ideology to assess the discrete effects of each measure and to mitigate multicollinearity. For our models predicting primary marginalization, however, we also included our measures of cross-group consciousness with LGBTQ+ communities—perceptions of discrimination against gays and lesbians and linked fate with LGBTQ+ persons—as predictors, given our contention that cross-group consciousness is an antecedent of primary and secondary marginalization. Though our previous analyses demonstrate that support for addressing challenges affecting Black women and intersectional ideology are both significant predictors of our measures of cross-group consciousness, the correlations among these variables are not strong enough to suggest severe (or even moderate) multicollinearity.Footnote 7

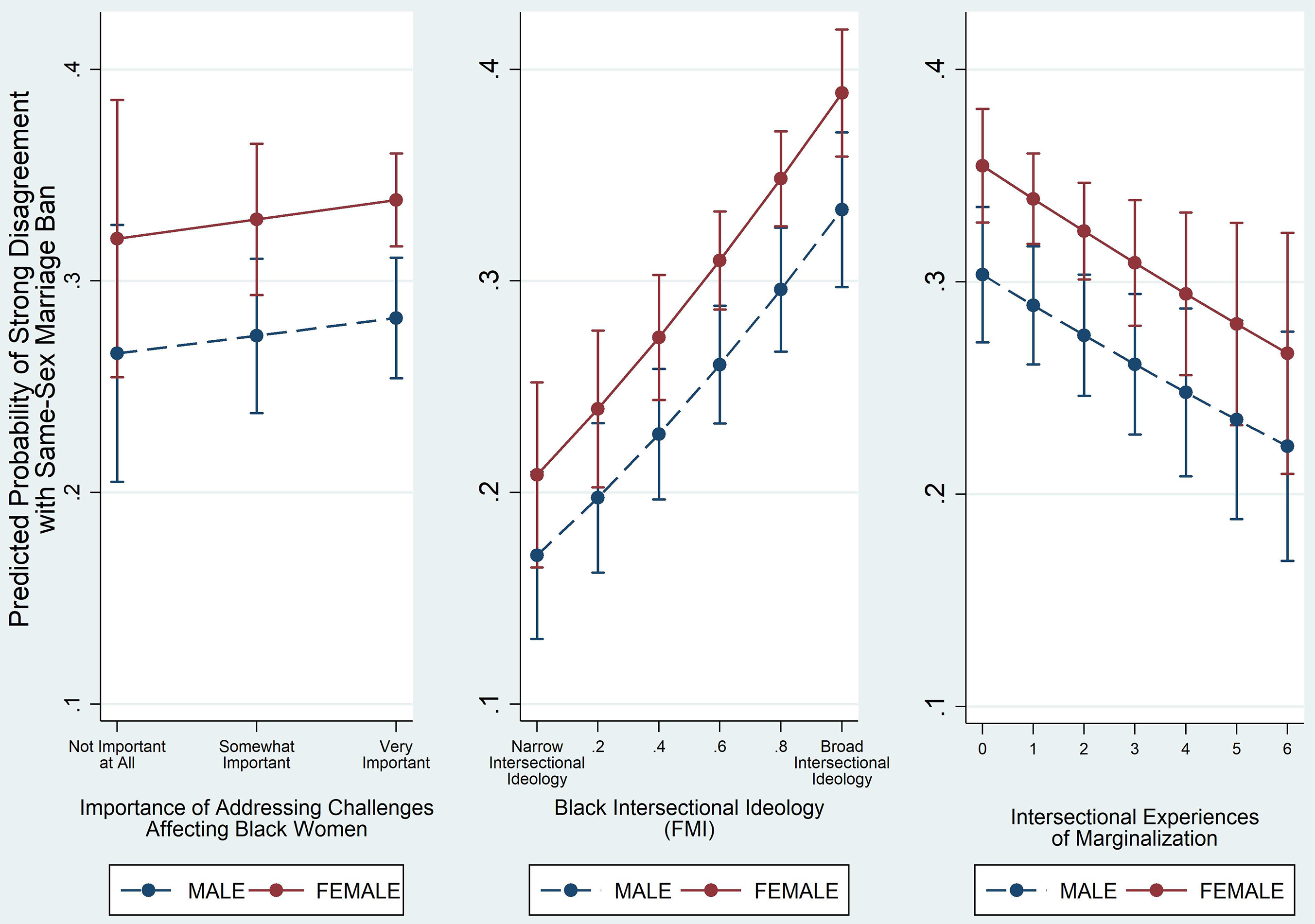

As indicated in Table 4 and illustrated in Figure 2, Black women are significantly more likely than Black men (roughly 20 percent more likely) to strongly disagree that there should be a constitutional ban on same-sex marriage (H1B). Also, illustrated in the first two panels of Figure 2, consistent with our predictions in H2B and H3B, support for addressing challenges affecting Black women and Black intersectional ideology are both positively associated with support for LGBTQ+ civil rights among Black respondents. Those with stronger orientations toward issues affecting Black women and those with broader Black intersectional ideologies are more likely to disagree that there should be a constitutional ban on same-sex marriage. Also, Black intersectional ideology is a stronger predictor of support for LGBTQ+ civil rights than support for addressing challenges affecting Black women (AIC = 5609.47 versus AIC = 5608.051and AIC = 5580.142, for the models including the NMI and the FMI, respectively). Black women and men with the broadest intersectional ideologies are both nearly twice as likely as those with the narrowest intersectional ideologies to strongly disagree that a constitutional ban on same-sex marriage is needed (87 percent and 96 percent more likely, respectively). The relationship between Black intersectional ideology and opinions about a constitutional ban on same-sex marriage is only statistically significant, however, for the FMI. Like the models predicting linked fate with LGBTQ+ persons, the predicted effect of intersectional ideology on this measure of support for LGBTQ+ civil rights appears to be driven by respondents’ support for addressing challenges affecting Black LGBTQ+ persons.

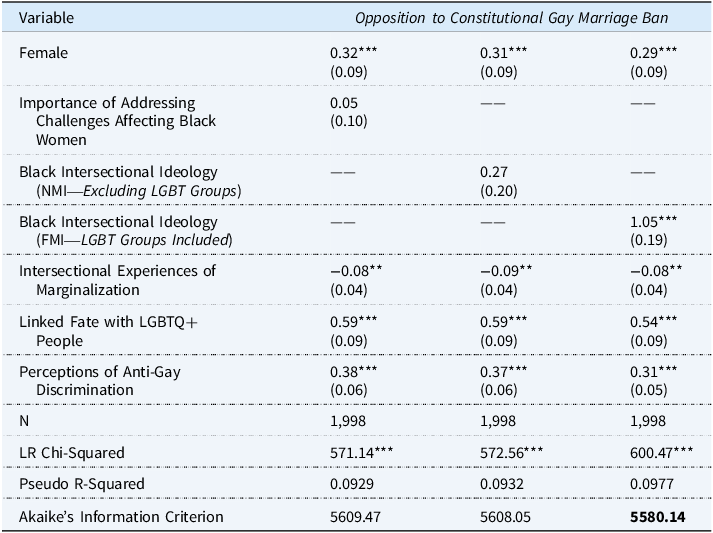

Table 4. Primary marginalization of LGBTQ+ persons: ordered logistic regression results predicting opposition to constitutional ban against gay marriages

*** p < .01 (two-tailed test) ** p < .05 (two-tailed test) * p < .10 (two-tailed test).

Note: Opposition to Constitutional Gay Marriage Ban ranges in value from 1 (‘Strongly Agree’ an amendment to the Constitution banning gay marriages is needed) to 5 (‘Strongly Disagree’ an amendment to the Constitution banning gay marriages is needed). Importance of Addressing Challenges Affecting Black Women ranges in value from 1 (not important at all) to 3 (very important). Black Intersectional Ideology ranges in value from 0 to 1, where higher values indicate having a broader Black Intersectional Ideology. All models include controls for linked fate with African Americans, political ideology, personally identifying as LGBTQ+, knowing someone who identifies as LGBTQ+, age, education, church attendance, voter registration, and nativity. Coefficients are unstandardized. Standard error estimates are in parentheses.

Figure 2. Predicted probability of strongly disagreeing that a constitutional amendment to ban same-sex marriage is needed by importance of addressing challenges affecting black women, black intersectional ideology, and intersectional experiences of marginalization.

Intersectional experiences of marginalization are also significantly related to opposition to a constitutional ban on same-sex marriage. As indicated in Table 4 and illustrated in the third panel of Figure 2, consistent with H4B, Black women and men with the most intersectional experiences of marginalization were roughly 25 and 27 percent less likely, respectively, than those with no intersectional experiences of marginalization to strongly disagree with a constitutional ban on same-sex marriage.

Secondary Marginalization of Black LGBTQ+ Persons

To examine our expectations regarding the secondary marginalization of Black LGBTQ+ persons, we estimated models regressing opinions about whether Black people should address challenges facing Black gays and lesbians as well as Black transgender persons on sex (H1C), support for addressing challenges affecting Black women (H2C), Black intersectional ideology (H3C), and intersectional experiences of marginalization (H4C). However, because the dependent variables in our models predicting support for secondary marginalization were included in our measure of Black intersectional ideology, we exclude these items from the FMI in these models. For the models predicting opinions about whether Black people should address challenges facing Black gays and lesbians, this item was excluded from the FMI; and, similarly, in our models predicting opinions about whether Black people should address challenges facing Black transgender persons, we excluded this particular item from the FMI. As with our previous analyses, both secondary marginalization variables are excluded from the NMI.

Consistent with our previous analyses, we estimated separate models examining the effects of support for addressing challenges affecting Black women and Black intersectional ideology to assess the effects of each of these measures independently and mitigate collinearity. Also, as with our models predicting primary marginalization, we included perceptions of discrimination against gays and lesbians and linked fate with LGBTQ+ persons (our measures of cross-group consciousness) as predictors as well.

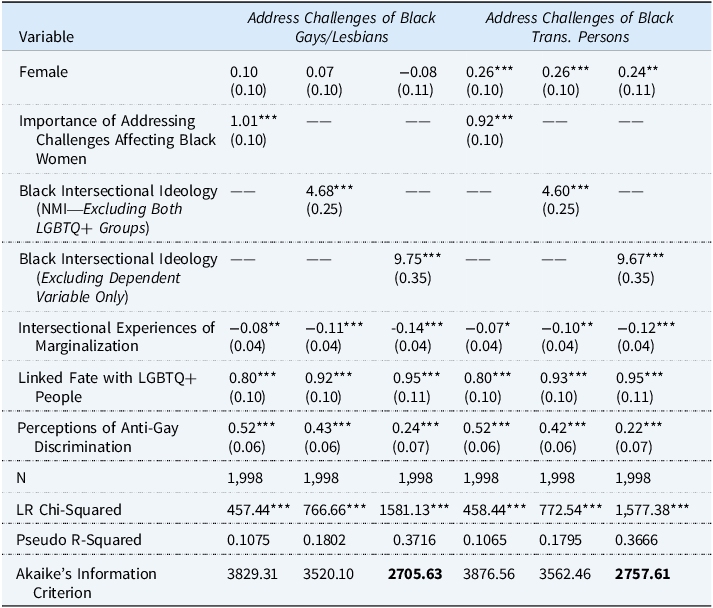

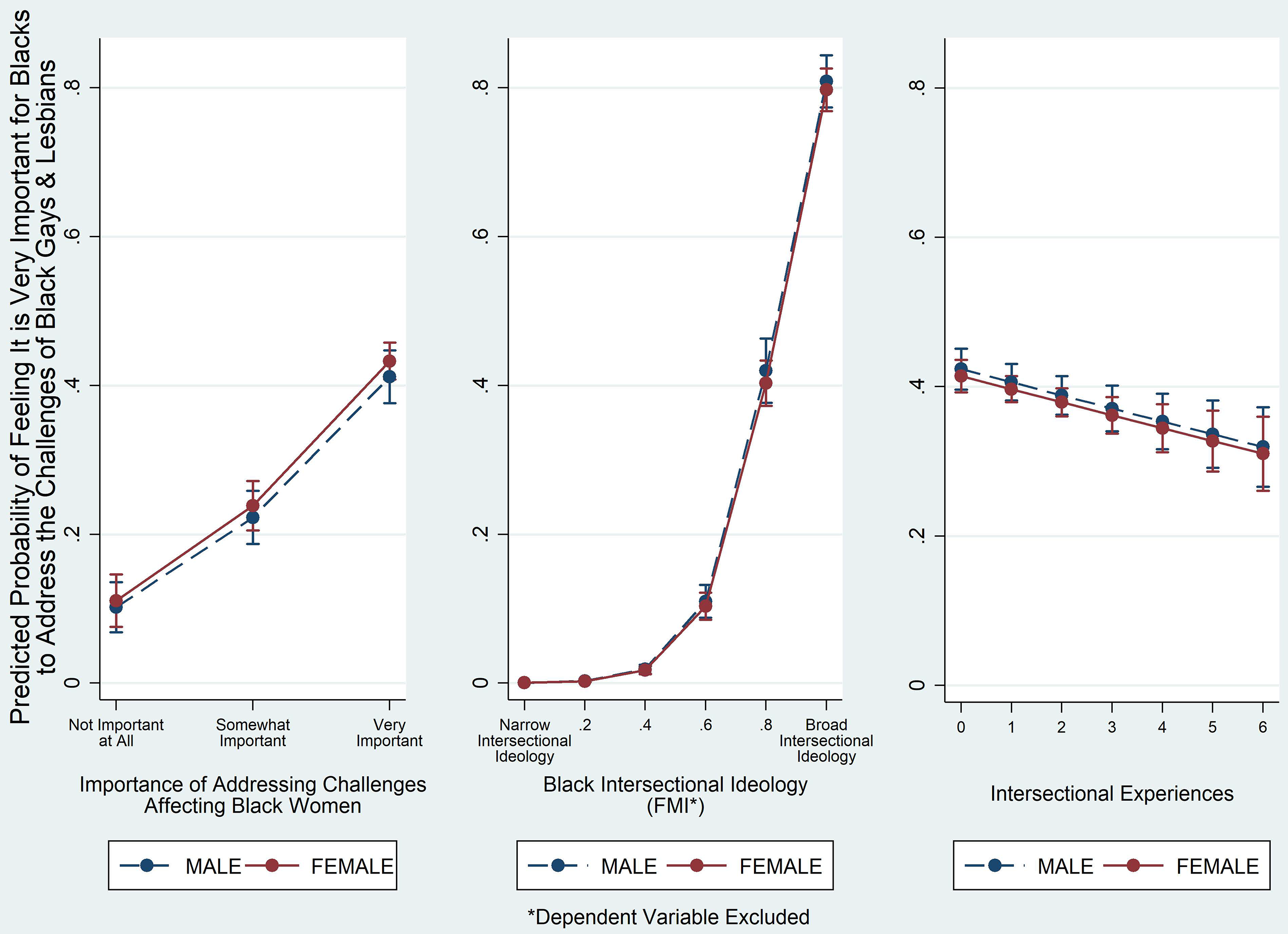

As indicated in Table 5 and Figure 3, in our models predicting the secondary marginalization of Black LGBTQ+ communities, Black women are no more likely than Black men to believe that it is important for Blacks to address the challenges faced by Black gays and lesbians. Though Black women are more supportive than Black men of addressing challenges faced by Black gays and lesbians overall (M = 2.17, SD = 0.775 and M = 2.08, SD = 0.775, respectively), t(3,011) = -2.8747, p = .004, when intersectional ideologies, intersectional experiences, and cross-group consciousness are included among our predictors, differences between Black men and women are not readily apparent.

Table 5. Secondary marginalization of Black LGBTQ+ persons: ordered logistic regression results predicting the importance of Black people addressing challenges affecting Black gays and lesbians and the importance of Black people addressing challenges affecting black transgender persons

*** p < .01 (two-tailed test) ** p < .05 (two-tailed test) * p < .10 (two-tailed test).

Note: Importance of Black People Addressing Challenges Affecting Black Gays and Lesbians and Importance of Black People Addressing Challenges Affecting Black Transgender Persons both range in value from 1 (not important at all) to 3 (very important). Importance of Addressing Challenges Affecting Black Women ranges in value from 1 (not important at all) to 3 (very important). Black Intersectional Ideology ranges in value from 0 to 1, where higher values indicate having a broader Black Intersectional Ideology. All models include controls for linked fate with African Americans, political ideology, personally identifying as LGBTQ+, knowing someone who identifies as LGBTQ+, age, education, church attendance, voter registration, and nativity. Coefficients are unstandardized. Standard error estimates are in parentheses.

Figure 3. Predicted probability of feeling it is ‘very important’ to address challenges Affecting Black Gays and Lesbians by importance of addressing challenges affecting Black Women, Black intersectional ideology, and number of intersectional experiences of marginalization.

However, Black women are consistently more supportive than Black men of addressing challenges faced by Black transgender persons. In the model that only includes support for addressing challenges affecting Black women, Black women are 15.5 percent more likely than Black men to believe that it is very important for Blacks to address the challenges facing Black transgender persons. In the model that includes intersectional ideology, Black women are 8.6 percent more likely than Black men to believe that it is very important for Blacks to address the challenges facing Black transgender persons.

Also, as predicted, support for addressing challenges affecting Black women is significantly related to both measures of secondary marginalization. Black women and men with the strongest support for addressing challenges affecting Black women are both roughly four times more likely (290 percent more likely and 303 percent more likely) than those with the weakest support to indicate it is very important to address the challenges of Black gays and lesbians; and Black women and men with the strongest support for addressing challenges affecting Black women are both several times more likely (245 percent and 272 percent more likely) than those with the weakest support to indicate that it is very important to address the challenges of Black transgender persons.

True to our models predicting cross-group consciousness and primary marginalization, however, Black intersectional ideology is a more robust predictor of our measures of secondary marginalization. The models that include Black intersectional ideology appear to explain significantly more of the variance in secondary marginalization and fit the data better than the models that only include support for addressing challenges affecting Black women, according to the respective AIC scores.

As indicated in Table 5, intersectional experiences of marginalization are also significantly, but negatively, associated with our measures of secondary marginalization across all of our models. Consistent with H4C, respondents who have had more intersectional experiences of marginalization are more likely to engage in secondary marginalization of Black gays and lesbians (illustrated in the third panel of Figure 3) and Black transgender persons. Substantively, in each of our models predicting support for addressing challenges faced by Black gays and lesbians and each of our models predicting support for addressing challenges faced by Black transgender persons, Black women and men who had the highest number of intersectional experiences of marginalization are roughly 20 percent less likely than those who have not had any intersectional experiences of marginalization to indicate that it is very important for Blacks to address challenges faced by these groups. Importantly, this suggests that Blacks who have experienced marginalization on the basis of fewer identity features are also more inclined to support addressing challenges faced by Black LGBTQ+ communities.

Discussion and Conclusions

In this paper, our purpose was to assess how intersectional ideologies and experiences affect African American support for the rights and concerns of LGBTQ+ communities. Extending upon insights from Cohen’s (Reference Cohen1999) theory of marginalization as well as identity theory (Harcourt Reference Harcourt2022), we examine opinions pertaining to the primary and secondary marginalization of LGBTQ+ communities as well as those pertaining to cross-group consciousness, which we argue underlies primary and secondary marginalization. We operationalized the insights of identity theory by distinguishing three measures of intersectionality or “interlocking oppressions” (Collective 1983, 272): support for addressing challenges affecting Black women; Black intersectional ideology; and intersectional experiences of marginalization. The picture that emerges from our results is generally consistent with our expectations and suggests that ideologies and experiences of intersecting marginalized identities can be critical to fomenting support for the rights and concerns of LGBTQ+ communities overall and of Black LGBTQ+ communities in particular. In the current era of narrow electoral margins between Democratic and Republican candidates, it is critically important to understand how to build viable electoral coalitions by drawing the support of numerous constituent communities inside of Black America (Johnson III Reference Johnson III2016). We summarize four main conclusions from our analyses and consider multiple implications.

First, as we predicted, Black women in our sample generally exhibit greater cross-group consciousness with LGBTQ+ communities and are more opposed to the primary marginalization of LGBTQ+ communities than are Black men. When intersectional orientations are taken into account, Black women do not significantly differ from Black men in their support for addressing challenges affecting Black gays and lesbians, possibly because the religiosity of some Black women still serves as a barrier to fuller acceptance (Heard Harvey and Ricard Reference Heard Harvey and Ricard2018; Walsh Reference Walsh2016). However, Black women are consistently more supportive of addressing challenges faced by Black transgender persons than are Black men. These findings are consistent with our contention that Black women’s race-gender intersectional lived experiences can, at times, lead them to be sympathetic to those experiencing aspects of gender discrimination (Gay and Tate Reference Gay and Tate1998).

Second, we found strong support for our prediction that African Americans who are more supportive of addressing challenges affecting Black women would be more opposed to the secondary marginalization of Black LGBTQ+ communities. However, support for addressing challenges faced by Black women had inconsistent relationships to cross-group consciousness and the primary marginalization of LGBTQ+ communities. Black respondents who believe it is important for Black communities to address challenges affecting Black women were significantly more likely to believe gays and lesbians face a lot of discrimination and were significantly more likely to believe in Black community support for addressing challenges affecting Black gays, lesbians, and transgender persons. Hence, this orientation toward supporting African American women—this race-gender lens—appears to be a powerful means of fostering greater sympathy with the struggles of LGBTQ+ persons. Still, to paraphrase Cohen (Reference Cohen1999), there are boundaries to this Black support for LGBTQ+ communities. Those who believe in greater Black community support for Black women were less likely to express linked fate with LGBTQ+ persons and support for addressing the challenges faced by Black women had no effect on opposition to a constitutional ban on same-sex marriage. One implication of these findings is that, since the time of the 1977 CRC Statement, Black feminism has made several, hard-won strides in not only ensuring that the interests of Black women are more readily addressed within Black politics—partly as voiced by increasing numbers of Black women candidates, elected officials, and Black women voters (Bejarano and Smooth Reference Bejarano and Smooth2022; Igielnik, Keeter, and Hartig Reference Igielnik, Keeter and Hartig2021; Philpot and Walton Jr Reference Philpot and Walton2007)—but these dynamics also help Black communities to more fully recognize the needs of Black LGBTQ+ persons as well as the presence of anti-LGBTQ+ discrimination. To reiterate, it has long been a goal of Black feminist politics for Black communities to make linkages among various forms of oppression—i.e., racial, gender, sexual, etc.—and to establish that “the major systems of oppression are interlocking” (Collective 1983, 272). However, we draw one key implication from the fact that those who support addressing challenges affecting Black women are no more likely to support same-sex marriage and are unlikely to see themselves as having linked fates with LGBTQ+ persons—neither of which directly pertain to racial oppression but are clearly pertinent to gender and sexual marginalization. Unless public officials and activists are successful in convincing Black Americans that LGBTQ+ interests and rights affect Black communities and civil rights, there may be limits to how much African American communities serve as allies in contentious public debates about LGBTQ+ rights, such as the rights of transgender persons in schools or elsewhere (Brown Reference Brown2022).

Third, we found strong support across all models for the prediction that African Americans with broader intersectional ideologies would have more cross-group consciousness with LGBTQ+ communities and be more opposed to the primary and secondary marginalization of LGBTQ+ communities. Black intersectional ideology was a consistently statistically significant predictor of each of our measures of primary and secondary marginalization of LGBTQ+ communities, providing compelling evidence that the breadth of one’s intersectional orientation can be critical to achieving a more inclusive African American politics (Shaw Reference Shaw and Georgia2011). In the 2024 election, various campaign analysts and politicos argued that “identity politics” were corrosive to the mobilization of a broad-based electoral coalition and thus the reason for Kamala Harris’s loss as the Democratic Party candidate for president (Rivers, Ketchum, and Summers Reference Rivers, Ketchum and Summers2024). While we freely concede our 2016 data is eight years prior to the 2024 election, both elections entailed highly contentious debates about issues of race, gender, and sexuality (Frey Reference Frey2024); for, of course, both elections had Donald Trump as the Republican candidate and women as the Democratic candidates. If indeed Black politics is not monolithic (Johnson Reference Johnson2020), we should not so easily dismiss the power of identity politics and intersectionality. Our findings suggest that one way to coalesce effective Black political coalitions is to micro-target various “Black communities” (plural). And such efforts will be most effectively led by Black activists and rank-and-file voters who are sympathetic to and in solidarity with various intersections of Blackness (Shelby Reference Shelby2005).

Lastly, we found that intersectional experiences of marginalization have conflicting relationships with cross-group consciousness and the primary and secondary marginalization of LGBTQ+ communities. As predicted, having a greater number of intersectional experiences of marginalization was associated with increased cross-group consciousness with LGBTQ+ communities. This was exhibited by respondents who reported being discriminated against on the basis of multiple marginalized identities, being more likely to perceive discrimination against lesbians and gays, and more likely to indicate having a sense of linked fate with LGBTQ+ persons. Yet, as also predicted, those with more discriminatory intersectional identity experiences were significantly less likely than those with fewer (or none) of such experiences to oppose a constitutional ban on same-sex marriage (primary marginalization) and to support addressing the concerns of Black LGBTQ+ communities (secondary marginalization). It is possible that some African Americans who have experienced heightened forms of discrimination resent the inference that their struggle should be aligned with those of LGBTQ+ persons, despite being aware of the marginalized social and political positionality of LGBTQ+ communities.

Mindful of the still quite present boundary lines of Blackness, Black politics, and the politics of respectability that the work of Cohen (Reference Cohen1999) and Lopez Bunyasi and Smith (Reference Bunyasi and Smith2019) examines, our findings suggest that more expansive intersectional frameworks may serve to broaden the alliances Black communities conceive as possible and necessary. Considering the persistent public health and other policy concerns that face Black women, LGBTQ+ persons, and other marginalized communities (Jones-DeWeever Reference Jones-DeWeever2005), our analysis sheds light on “When and Where [We] Enter…” there are pathways to a more inclusive and intersectional Black identity politics.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/rep.2025.10044

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Jamil Shatema Scott, Chaya Crowder, and the panelists and participants at the “Black Women and Leadership” panel at the 2020 American Political Science Association Annual Meeting as well as the University of South Carolina Department of Political Science for their thoughtful feedback on the initial draft of this work. We are also grateful to the editors and anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback, which greatly strengthened the overall quality of the final manuscript.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific financial support.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare none.