Taiwanese politics is typically divided into two camps: the “blue” camp, which supports the Chinese Nationalist Party (Kuomintang 國民黨, KMT hereafter) and is more sympathetic to the People’s Republic of China (PRC), and the “green” camp, which supports the Democratic Progressive Party (Minchu chinpu tang 民主進步黨, DPP hereafter) and is more sceptical of the PRC. However, not everyone in Taiwan falls into one of these two camps. Since 2017, the number of non-partisan independent voters who do not identify with either major party has drastically increased in Taiwan to between 30 per cent and 40 per cent of Taiwan’s voter base.Footnote 1 This phenomenon is not unique to Taiwan; around the world voters in democracies have increasingly moved away from specific political parties or partisan candidates.Footnote 2 Yet, little is known about Taiwan’s independent voters, their feelings on contemporary political issues and the extent to which the blue and green camps influence their political attitudes. Despite the growing polarization in democracies worldwide, this substantial non-partisan independent voting bloc warrants empirical investigation.

Independent voters in Taiwan are significant for two key reasons. First, owing to Taiwan’s contested status and the dominance of the cross-Strait political cleavage in electoral politics, independent voters play an important yet understated role in deciding the future direction of Taiwan.Footnote 3 Second, third-wave Asian democracies are not immune to the growing challenges and decline of democracy around the world.Footnote 4 As the largest and fastest growing voting bloc in Taiwan, the sentiments of independent voters regarding democracy and the changing landscape of Taiwanese politics have important implications for the future of democracy in Taiwan and East Asia.

In this study, we empirically examine independent voters and their support for contemporary Taiwanese domestic issues through the lens of the Bluebird movement. These mass protests, which erupted in May 2024, represent the largest form of civil unrest in Taiwan since the 2014 Sunflower movement. The Bluebird movement began with a series of mobilized protests against a proposed legislative reform that would grant Taiwan’s Legislative Yuan the power to question and interrogate senior-level politicians, including the president. Protestors viewed the reform as an attempt to undermine democratic principles by infringing on civil liberties. Despite this, the legislative reform and subsequent social protests were framed in dramatically different ways by Taiwan’s now three main political parties. While the KMT and the Taiwan People’s Party (Taiwan minchungtang 台灣民眾黨, TPP hereafter) supported the reform as a necessity, the DPP deemed it to be unconstitutional. These clashing positions sent different messages to voters in Taiwan.Footnote 5

Although the Bluebird movement and legislative reform were not directly about the PRC or Taiwan’s future, the movement was intensely partisan. The DPP and green-leaning Taiwanese voters backed the protests and criticized the reform, while the KMT and TPP took an opposing stance. Both sides claimed to be the defenders of democracy, denouncing the other camp, along with its supporters, as anti-democratic. This highly partisan event presents a unique opportunity to study non-partisan, independent voters and interrogate the following questions. How did partisan framings by each political party in Taiwan influence independent voters? How effective were these different frames in swaying public opinion among voters, including independents? How do independent voters feel about the reform and the subsequent protests, especially in comparison to partisan voters?

To preview our results, our empirical findings indicate which party won the framing contest: independent voters tended to align with the KMT and blue-leaning framings of the protests rather than with the DPP and green-leaning framings of the movement. Contrary to both parties’ claims of representing a silent majority of Taiwanese voters, our data suggest that independent voters are more likely to be “feeling blue” regarding the Bluebird movement. However, unlike KMT and TPP supporters, independent voters in Taiwan are less supportive than blue voters of undemocratic practices. Our findings suggest that although the KMT and TPP managed to win over independent voters on this set of issues, independent voters remain more supportive than their blue counterparts of democratic practices. Given the electoral share and growing number of independent voters in Taiwan, this has positive implications for the future of Taiwanese democracy. This study contributes to our understanding not only of the relationship between contemporary social movements and political parties in Taiwan but also of the role of independent and third-party voters in the future of Taiwanese democracy.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Next, we review the literature on how and why independent voters matter for democracy and democratic health. We then briefly explore framing theory and articulate why this theoretical approach is particularly relevant for studying independent voters and the Bluebird movement as a whole. We also review the controversial bill, its history and the subsequent political context that led to the rise of the Bluebird movement. Additionally, we identify the key frames and counter-frames presented by each party surrounding the protests and analyse two waves of original representative public opinion data that explicate public support for both the legislative reform and the protests. We conclude by discussing the implications of these reforms and what these results mean for Taiwan’s democratic health.

Independent Voters and Democracy in Taiwan

Broadly defined, independent or non-partisan voters are individuals who do not identify with, or consistently support, a specific political party. Although often overlooked in the scholarship on political ideology and partisanship, they constitute a distinct and influential segment of the electorate.Footnote 6 This is in part because party identification is widely recognized as the most powerful predictor of voting behaviour, yet independents show electoral unpredictability.Footnote 7 They are more likely to base their decisions on particular issues, candidate qualities or salient events, and through this, their votes are more fluid. Because independent voters are free from partisan constraints, they are pivotal in swinging election outcomes and, in some cases, hold the “balance of power.”Footnote 8

Despite their crucial role in politics, independent voters remain understudied, in part because they defy traditional political classifications.Footnote 9 Scholars have suggested that some may be “closet partisans,” “undercover partisans” or “independent leaners” who consistently favour one party without formally affiliating with it, distinguishing themselves from openly partisan voters.Footnote 10 Others contend that their reluctance to publicly identify with a party may stem from political disengagement, dissatisfaction with existing party options, or a desire to avoid being labelled in general. Additionally, independent voters tend to exhibit greater volatility in their electoral behaviour. This volatility may be attributable to various factors, including political apathy, distrust in political elites, or even an elevated level of political knowledge that complicates their decision making. Psychologically, they may also differ from partisans by resisting group-based identification, which poses further challenges for scholars attempting to study this multifaceted group as a general entity.Footnote 11

Scholars have increasingly noted a global rise in the number of individuals identifying as independent voters, a shift that reflects broader transformations in political engagement and voter behaviour, particularly as party loyalty weakens across many democracies.Footnote 12 This growth in independent voters can have significant consequences for democracy itself.Footnote 13 On the one hand, independent voters can function as a check on party dominance. Because they are not bound by rigid partisan loyalties, they are less susceptible to affective polarization.Footnote 14 On the other hand, some independent voters exhibit lower levels of political interest, political knowledge and political activity.Footnote 15 Moreover, their unpredictable nature can lead to political instability.Footnote 16 As such, independent voters hold crucial implications for the health of democracy, serving as a critical group that can either promote democratic stability or contribute to democratic fragility.Footnote 17

Independent voters in Taiwan

The rise of independent voters in Taiwan has become particularly notable, mirroring trends observed in many other democracies. Rather than aligning with the DPP or KMT, many of these voters describe themselves as issue-oriented, making electoral decisions based on specific policies, candidate attributes, or salient social and economic concerns. According to the Pew Research Center, Taiwan’s independent voters tend to be younger, more educated and urban residents who exhibit a strong identification with a Taiwanese national identity, rather than a Chinese one.Footnote 18 Empirical research has also shown that the number of non-partisan voters has grown significantly in Taiwan since 2017.Footnote 19 These voters have swung back and forth on the independence–unification scale over time, and in many ways are electorally unpredictable, especially in comparison to partisan blue and green voters.

The emergence of independent voters in Taiwan is making its mark in several ways. Since 2014, growing dissatisfaction and frustration with the major political parties (the DPP and KMT) have led many independents to distance themselves from these institutions and explore third-party alternatives. According to recent survey data from the Taiwan Election and Democratization Study (TEDS), there is a decline in party identification and an uptick in support for third parties, such as the TPP, among independents.Footnote 20 Additionally, independents have shown a declining interest in politics and are less attentive to political affairs.Footnote 21 Notably, there are stark differences in voting behaviour among individuals with different levels of education, as well as between pure independents and partisan “leaners.”Footnote 22 Independent voter behaviour has become increasingly unpredictable, as partisan attachment is often a key predictor of voting choices. Even within the independent voter segment, significant differences exist, leading to crucial implications for Taiwan’s political and partisan environment and democratic health.Footnote 23 This unpredictable behaviour, stemming from a lack of partisanship, has become even more critical in recent times.

Political Context: Political Parties, the Legislative Reform Bills and the Bluebird Movement

The 2024 general election in Taiwan resulted in the DPP forming a minority government. Although the party achieved an unprecedented third-term presidency, it was unable to secure a majority in the Legislative Yuan, winning only 51 seats, while the newly founded TPP won 8. The KMT, with 52 out of 113 seats (or 54 if 2 pro-KMT independents are included), emerged as the largest party in the Legislative Yuan but fell short of an absolute majority, which requires 57 seats. As a result, the necessity of forming political coalitions placed the TPP in a pivotal position, granting it the power to act as a “kingmaker.” Against this backdrop, the KMT quickly formed a coalition with the TPP, thereby dominating the legislative agenda in the Legislative Yuan.

Partisan fight over legislative reform bills

Just two months into the legislative session, the KMT–TPP coalition proposed a series of legislative reform bills. These included amendments to various laws and contained several key elements.Footnote 24 First, the bills sought to expand legislators’ investigative powers beyond mere document review, which is the current level of authority.Footnote 25 Second, the legislature would gain the right to conduct investigations, hold hearings and approve official appointments. Third, the reform would require the president to submit a “State of the Nation” report and address the Legislative Yuan on national affairs. Legislators would be allowed to ask questions, and the president would be obligated to respond promptly and in order.Footnote 26 Overall, the proposed legislative reform would significantly expand legislative power and curb the authority of the executive branch.

The means by which the KMT–TPP coalition attempted to pass the legislation were controversial. For one, the coalition leveraged its majority advantage to procedurally block the DPP’s proposals multiple times. For instance, the KMT–TPP coalition rejected the DPP’s request for more public hearings and refused to incorporate the DPP’s proposals into the review process. Additionally, during the article-by-article review, the KMT–TPP coalition technically bypassed substantive discussion by calling for the reserving of articles for cross-party negotiation.Footnote 27 However, when cross-party negotiations finally took place, there was no discussion on the proposed legislative reform bills. As a result, only the draft bills proposed by the coalition were passed for a second reading after the negotiations. On 17 May 2024, the Legislative Yuan attempted to pass a second reading of the bills; however, “new versions” were introduced to be voted on. On the day of the second reading, a physical fight broke out among legislators, leaving some injured. Moreover, recorded voting, an established legislative practice since Taiwan’s democratization, was changed to anonymous voting, with only the total vote counts being presented in the second reading.

The rise of the Bluebird movement

This series of events, labelled as “black box” politics owing to the non-transparent and non-democratic nature of the process, prompted significant criticism from the public and sparked protests. One concern centred on the unconstitutionality of the proposed bills. Under Taiwan’s current system, the authority to audit, investigate and impeach officials rests with the Control Yuan. The semi-presidential system also does not require the president to answer questions during national addresses. Critics argued that the proposed reform would alter the balance of executive–legislative relations and risk unconstitutionally expanding legislative power under the current framework.

Protests began late on 17 May 2024, the day of the fight in the Legislative Yuan. Initially, only a few hundred people gathered to protest outside the Legislative Yuan, but by 21 May, the day of the second reading and just one day after President Lai Ching-te’s inauguration, the crowd had swollen to 30,000. By 24 May, more than 100,000 demonstrators had gathered around the legislature.Footnote 28 On 28 May, an additional 70,000 people took to the streets. Altogether, along with supportive protest events around the globe, this became known as the “Bluebird movement.”

The protests themselves were not affiliated with the DPP. The organizers, speakers and key figures involved in the protests were either unaffiliated with a political party, members of NGOs or from smaller third parties. Although the DPP had a presence at the protests, it maintained a distance from the formal organizing efforts.Footnote 29 President Lai himself never directly endorsed the movement and called for unity across the political spectrum during his inauguration speech, which took place as the protests were ongoing.

Despite the controversy and subsequent protests, the bills were passed by the Legislative Yuan on 28 May 2024. In response, the executive branch returned the bills to the legislature for reconsideration at the end of June, a move which ultimately failed due to the opposition’s majority. Subsequently, in July, the DPP administration filed a petition with the Constitutional Court to determine the constitutionality of the passed bills and temporarily froze their implementation. Taiwan’s Constitutional Court heard the case and issued its ruling in October 2024. The verdict affirmed that most of the bills included in the legislative reform package were unconstitutional, while some were deemed constitutional only if interpreted in a specific manner.

Partisan Framing and Its Effects on Partisans and Non-partisans

Due to the highly controversial nature of the reform bills, each political party attempted to dominate the narrative surrounding the controversy. Framing allows different parties, whether political groups or social movement organizations, to present an issue to the broader public with the aim of increasing or reducing support for their position by promoting their own interpretations. Various actors, including movements and parties, compete not only in how they present the issue but also in how they respond to other frames through counter-frames, which seek to “rebut, undermine, or neutralize a person’s or group’s myths, versions of reality, or interpretive framework.”Footnote 30 In this way, framing is not simply a matter of one party proposing how an issue is framed but rather a contested process of framing, counter-framing and re-framing.

In the case of Taiwan, prior to the passage of the controversial bills, the different political parties had already framed the legislative reform issue differently, each emphasizing their ideas and intentions. The three main political parties presented diverse interpretations of the legislative reform and the subsequent Bluebird movement, competing with their distinct frames to influence public opinion, which in turn signalled which frames were more successful at shaping public sentiment.Footnote 31

Framing theory, combined with public opinion data, helps to ascertain which party’s frames were more successful in the recent legislative proposals and Bluebird movement in Taiwan. Long-term scholars of Taiwan politics hypothesize that public support should simply follow the partisan framings of the protests and the legislative proposals. What is missing, however, is an understanding of how independent voters – Taiwan’s largest voting bloc – feel about the different party frames. While we may accurately anticipate how partisans will feel about these issues, independent voters are a much more enigmatic group. If the DPP’s framing of these events is more successful, we should see its message resonate beyond its base of support. Conversely, if independent voters are more likely to oppose the protests and the policy changes, then this may indicate that the KMT was more successful in shaping the public debate with its framing.

Three frames of the legislative reform

We identify three key frames used by political parties during the legislative reform period: democratic health, balance of power and protest legitimacy. Table 1 summarizes all competing frames proposed by different political parties.

Table 1. Frames by Party and Issue

First, each party contended that its actions regarding the reform bills were in the best interests of Taiwan’s democratic health and that the actions of other parties were detrimental to the island’s democratic progress. The KMT–TPP alliance framed the reform as a “necessary measure” to curb executive power and enhance the system of checks and balances within Taiwan’s political structure to strengthen Taiwan’s democracy. The alliance argued that the reform was crucial for establishing a more robust checks and balances system that would protect democracy.Footnote 32 For an example, during an international press conference on 23 May, the KMT stated that “to consolidate and deepen Taiwan’s democracy, parliamentary reforms in the Legislative Yuan are imperative.”Footnote 33

The KMT–TPP alliance further criticized the DPP for violating democratic principles, arguing that democracy relies on the minority respecting the majority and checks on power. According to the KMT, the DPP disregarded these principles in the Legislative Yuan while inciting anti-China sentiment to block the reform.Footnote 34 The KMT claimed that the proposed bills would promote transparency and hold the government more accountable.

The KMT also questioned the legitimacy of the protests, arguing that it had followed proper democratic procedures. It accused the DPP of misleading the youth by framing the reform as “black box legislation,” a term that has been commonly used in criticism of blue-leaning politics since the 2014 Sunflower movement.Footnote 35 The KMT stated that the reform bills went through three public hearings, two committee reviews, one special report and four cross-party negotiations. Additionally, 49 experts provided their insights during the public hearings. During the review process, the KMT accused DPP legislators of engaging in slander while avoiding any substantive discussion of the bills.Footnote 36

Meanwhile, on the other side of political aisle, the DPP strongly opposed the reform, viewing it as a threat to democratic norms and effectively a separation of powers among branches of government. It argued that the bill would grant legislators excessive power, encroaching on the authority of the executive branch.Footnote 37 Additionally, the DPP criticized the manner in which the draft bills were handled, asserting that the process was undemocratic and constituted an abuse of power. It supported calls for more democratic procedures and, by extension, the protests against the bills.

Like the KMT–TPP coalition, the DPP portrayed itself as the true defender of Taiwan’s democracy. Accordingly, the protests were subsequently framed by the DPP as a grassroots movement in defence of Taiwan’s democracy. The DPP expressed explicit and total support for the protests, repeatedly emphasizing that the protests themselves were a sign of the Taiwanese public’s dissatisfaction with the KMT–TPP alliance and the legislative reforms.

Neither side has altered its framing of the protests or how it portrays the other party since the launch of the Bluebird movement, and all major parties doubled down on their representations of each other as the protests continued. To this day, the DPP frames the KMT and TPP as key violators of democratic safety in Taiwan, while the KMT and TPP portray the DPP as overly powerful and anti-democratic. These frames remain the dominant narratives both parties use against each other. During both waves of surveys conducted for this study, neither party meaningfully changed or varied its framing

Framing effect on partisan and non-partisan voters

Following on from the above discussion on each party’s key frames and platforms on the issue of the legislative reform bills and protests, we can expect that these frames had different effects on public support for both the bills and the subsequent protests. We predict a partisan divide in how Taiwanese people viewed the proposed reform and the protests. Partisanship and polarization along party identity lines have become enduring features of Taiwan’s elections, as voters with a partisan identity tend to align with their own party while strongly opposing the opposing party.Footnote 38

Subsequently, we expect to see a partisan divide that has become typical in Taiwanese politics. Specifically, we contend that DPP supporters are likely to oppose the bill, have lower tolerance for undemocratic procedures and express greater support for the protests. In contrast, KMT and TPP supporters are expected to have the opposite preferences, i.e. greater support for the reforms and lower support for the protests. However, since the KMT–TPP coalition framed the legislative reform as a means to enhance democracy, it is unclear whether the supporters of those parties would report greater tolerance for undemocratic procedures; they may have supported the reform while simultaneously rejecting undemocratic practices.

While partisanship plays a critical role in shaping preferences regarding the reform bills, a significant proportion of voters remain unsure about their partisan identification or do not identify with a particular party (i.e. independents). As mentioned above, examining independents is especially important because approximately 30–40 per cent of the Taiwanese electorate lacks any clear party identification, despite the presence of three major parties. Such a large bloc of independent voters can significantly swing public opinion. As a result, a key question of this study concerns which framing resonated with independents and to what extent they expressed acceptance of undemocratic procedures.

Hypotheses

With the growing dissatisfaction with major parties, independents are increasingly casting their ballot based on their frustration and scepticism towards the incumbents.Footnote 39 This negative sentiment is particularly evident regarding incumbents, who are often assessed through a retrospective lens due to the low partisan attachment of these voters.Footnote 40 As independents evaluate incumbents based on their past performance, they may hold more negative views of the incumbent leader than of the opposition leader. Consequently, independent voters tend to be more susceptible to anti-incumbent messaging.

In the case of Taiwan, the weakening of party identification and the lack of a strong loyalty to a party among independent voters can make them more sceptical of incumbents. They are more likely to criticize the past performance of the incumbent party and to be swayed by anti-incumbent messaging. Based on previous studies of non-partisan voters and Taiwanese voting behaviour, we subsequently offer the following hypotheses:

H1: In line with the KMT’s framing, independent voters are more likely to support the legislative reform and oppose the Bluebird movement protests

If independent non-partisan voters align with the KMT regarding the Bluebird movement and legislative reform, does this indicate that their politics overlap with Taiwan’s pan-blue coalition? This warrants an investigation into how similar or different independent voters are from the pan-blue coalition. We test similarities in politics between independent voters and the pan-blue and pan-green camps by asking a series of questions about Taiwan’s democracy, democratic health and features of Taiwan’s political system.

H2: Independent voters are likely to have the same levels of support as pan-blue voters for democracy, democratic practices and defending democracy

Data and Methods

We conducted two waves of a nationally representative survey: the first on 12–14 July 2024 and the second on 25–28 November 2024. The first survey was conducted as the ruling and opposition parties were engaged in a political fight over the legislative reform through institutional channels, including the reconsideration process and petitions for constitutional interpretation. The second survey took place after the Constitutional Court ruled that major parts of the legislative reform were unconstitutional. One empirical question we sought to answer was whether independent voters’ attitudes persisted or were altered by the constitutional hearing results. By conducting two waves, we were able to investigate whether public opinion changed following the constitutional hearings and ruling. Both waves were facilitated by National Cheng Chi University and included a total sample size of 1,500 respondents for each wave.

The survey included three key questions regarding the legislative reform bills, the Bluebird movement and attitudes towards undemocratic procedures.Footnote 41 First, we asked respondents about their support for legislative reform: “The legislative reform bills concerning the powers of the Legislative Yuan were passed in their third reading at the end of May 2024. Do you support the proposed congressional reform legislation?” Second, we inquired about their stance on the ongoing street protests: “There has been a lot of public discussion and street protests regarding the parliamentary reform bills. Do you support these civil political gatherings and protests?” Finally, we assessed respondents’ views on undemocratic procedures by asking them to what extent they agreed with the following statement: “As long as the content of a bill is beneficial to the country, whether the review process adheres to democratic procedures is not that important.” The last survey item was designed to measure and gauge respondents’ willingness to accept undemocratic procedures if the end goal of a reform is perceived as desirable. For all three questions, respondents were asked to answer using a five-point Likert scale, ranging from strong opposition to strong support.

In the second wave, in addition to the original three questions, we included a fourth question asking whether the respondents believed that the Constitutional Court ruling was fair. We were very cautious in wording the question to avoid any potential partisan cues and followed the neutral language used in the ruling documents. Moreover, because not all citizens were familiar with the event, we included a summary of the ruling results to ensure that all respondents were equally informed. The question was worded as follows:

The legislative reforms concerning congressional powers – amendments to the Laws Governing the Legislative Yuan’s power and the Criminal Code – were passed in their third reading at the end of May 2024. Following the Executive Yuan’s failed request for bill reconsideration and a temporary injunction issued by the Constitutional Court, the Constitutional Court delivered its ruling on 25 October. The decision found most provisions of the reform package unconstitutional, while some articles were deemed constitutional upon interpretation. Provisions related to the President’s state of the nation address, interpellation of executive officials by legislators, the Legislative Yuan’s confirmation powers, its investigatory powers, and the holding of public hearings were partially ruled unconstitutional. The offence of contempt of Congress was declared entirely unconstitutional. Do you believe this ruling was fair?

We are primarily interested in identifying whether a clear partisan divide exists in public opinion, whether the distribution of opinions aligns with how different political parties have framed the ongoing controversy, and whether such a divide has continued after the Constitutional Court ruling. We also aim to re-examine whether there is a consistently clear partisan divide regarding the acceptance of undemocratic norms. In addition to gauging partisan differences, we seek to examine the opinions held by independents. To this end, we created dummy variables for supporters of the KMT, DPP, TPP, and Independents. Our model also includes a standard set of control variables, such as views on relations with China (pro-unification/pro-independence), nationalist sentiment, political interest, gender, age, education and income.

Empirical Results

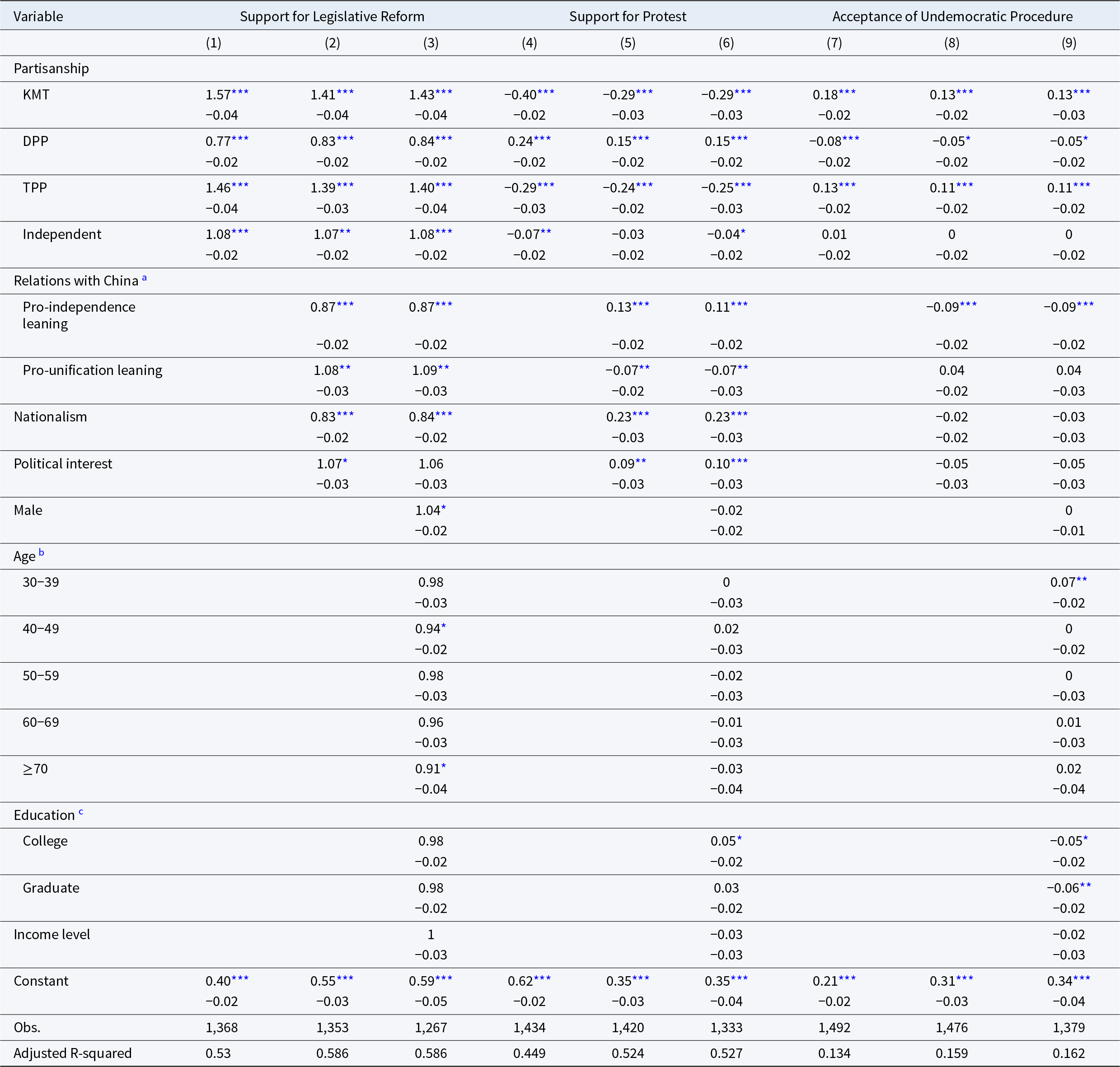

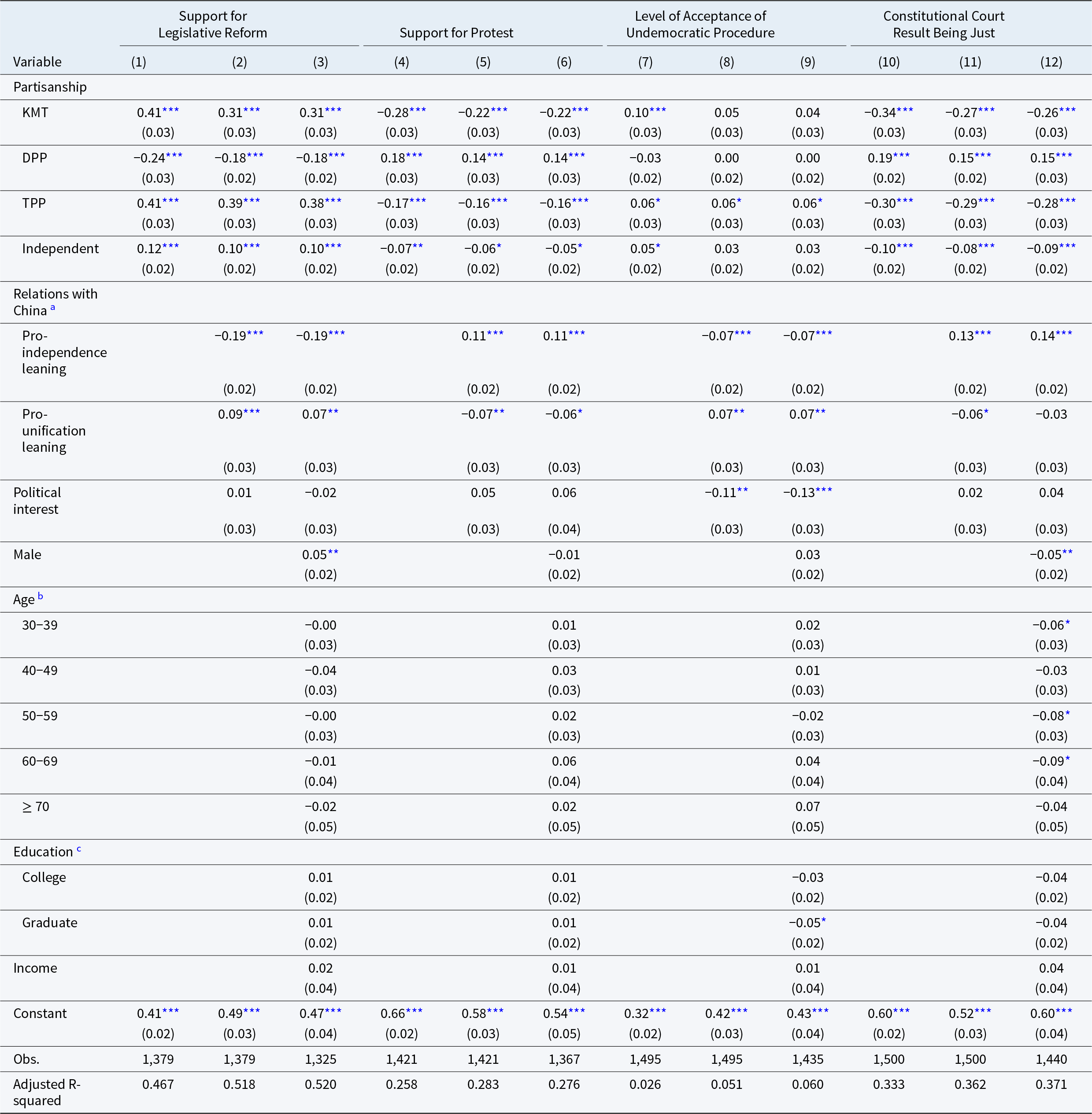

Tables 2 and 3 show the empirical results for the first and second waves, respectively. For each dependent variable, we estimated three models. The first is a baseline model, followed by a second model that incorporates key control variables, and a third model that includes the full set of control variables.

Table 2. Regression Results of July 2024 Data

Notes: Standard errors in parentheses. aBaseline: status quo; bbaseline: 20–29; cbaseline: high school/vocational and below.

* p < .05. **p < .01. ***p< .001.

Table 3. Regression Results of November 2024 Data

Notes: Standard errors in parentheses. aBaseline: status quo; bbaseline: 20–29; cbaseline: high school/vocational and below.

* p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Support for legislative reform

Columns (1) to (3) in both tables show the regression results of support for the legislative reform. Given that the legislative reform was initiated by the KMT and supported by the TPP, it is unsurprising that DPP supporters were significantly less supportive, while KMT and TPP supporters were more supportive. In addition, individuals who were more pro-independence and exhibited stronger Taiwanese nationalist sentiment tended to be less supportive of the reform. This is as expected, as these people tend to be the core supporters of the DPP. These findings are consistent across both waves of the survey.

Our most important and novel finding, however, is that individuals without party affiliation (independents) also reported significantly higher levels of support for the legislative reform even after accounting for all control variables. This may indicate that independents view the reform as introducing greater checks and balances within the political system and, on this particular issue, they may be more likely to support the KMT and TPP. Interestingly, those with a stronger interest in politics were more likely to support the reform. Additionally, men were also significantly more supportive of the legislative reform compared to women, and younger (20–29 years old) age groups were more likely to support the reform while older people (aged 40–49) were notably less supportive. Education and income appear to have no significant impact on attitudes towards legislative reform.

Support for the protests and Bluebird movement

In contrast to support for the legislative reform, the results regarding support for the protesters in the Bluebird movement show the opposite pattern (Columns (4) to (6) in both tables). Only DPP supporters were significantly more likely to support the street protests, while KMT supporters, TPP supporters and independents were generally less supportive of the movement. This division between the DPP and the other groups is similar to that observed for the first question regarding support for legislative reform.

One intriguing, yet puzzling, finding is that individuals with a strong interest in politics were simultaneously supportive of both the reform and the protests, suggesting a complex relationship between political engagement and these contentious issues. Unlike support for the legislative reform, gender and age do not show any significant association with attitudes towards the protests. However, education does play a role, with higher-educated individuals, particularly those with a college education, being more supportive than those with lower levels of education of the protests.

Accepting undemocratic procedures

When asked about the extent to which citizens would accept undemocratic procedures, the distribution of opinions is skewed to the left, with both the median and mean scores at 0.25 (on a 0–1 scale), indicating that most people in Taiwan are generally less tolerant of undemocratic practices. However, we also examined whether partisanship significantly influences levels of tolerance for undemocratic procedures. Columns (7) through (9) in both tables display the regression results, where we observe a clear distinction between independents and KMT or TPP supporters. While KMT and TPP supporters were significantly more likely to support the statement that undemocratic procedures are acceptable if the end goal is desirable, independents did not show a similar level of support. However, independents were also not as strongly opposed to undemocratic behaviour as DPP supporters.

It is possible that individuals with weaker democratic values are more likely to support the KMT and TPP, or that these parties have persuaded their supporters to be more accepting of undemocratic procedures. In either case, the results of our third analysis suggest a partisan association with adherence to democratic principles. Additionally, pro-independence individuals were significantly less tolerant of undemocratic behaviour. Education is also a significant predictor, with more educated individuals displaying significantly lower support for undemocratic procedures. Interestingly, younger individuals were not necessarily more opposed to undemocratic practices, and neither were those with a higher interest in politics.

Finally, one important variation between the two waves is the KMT’s and TPP’s relative support for undemocratic behaviour. In our first wave, which was conducted in July during the height of the protest’s saliency, both KMT and TPP supporters were significantly more likely to tolerate undemocratic behaviour. In November, however, KMT supporters were no longer significantly more likely to tolerate undemocratic behaviour. TPP voters, meanwhile, were still significantly more likely to support undemocratic practices. These findings demonstrate a particularly strong acceptance of undemocratic behaviour by the TPP, which is unique – even among KMT respondents.

Considering the development of the constitutional ruling, we followed up with a second wave to assess whether people’s opinions had changed. This survey wave included a question asking respondents if they found the Constitutional Court ruling just or not. Ultimately, Columns (10) through (12) of Table 3 indicate that people’s perception of the constitutional ruling was also partisan: DPP supporters found the ruling just, while KMT and TPP supporters did not. Independent voters, however, again aligned with the KMT–TPP coalition and were significantly more likely to perceive the ruling as unjust, further highlighting that independent voters were more likely to align with the KMT–TPP coalition on this issue and not the DPP.

Discussion and Conclusion

There are two key takeaways to our study. First, independent voters in Taiwan are more closely aligned with the KMT regarding the Bluebird movement and legislative reform. Data suggest that the KMT’s framing is more effective than the DPP’s framing in appealing to independent voters. While partisan frames can effectively mobilize party support, they may have long-term implications for Taiwanese democracy. Those who identify with the frames of the KMT–TPP coalition are more likely to accept undemocratic practices compared to those who identify with the DPP’s frames.

Second, independent voters are different from KMT–TPP supporters, particularly regarding non-democratic practices. Although they aligned on the issues investigated in this paper, there are still meaningful differences between independent voters and partisan voters, whether they are aligned with the KMT, TPP or DPP. At the height of the legislative reform protests, our data indicate that KMT and TPP supporters were more likely to accept undemocratic practices. Although this significance diminished for KMT supporters in the second wave of the survey, it remained consistent for TPP supporters. Our findings suggest that, under certain conditions, KMT voters are more likely to accept undemocratic practices – for example, during moments of legislative uncertainty or with regard to large-scale protests supported by the DPP. This effect is seemingly temporary; at other times, KMT voters are not supportive of undemocratic practices. In contrast, independent voters do not exhibit the same levels of acceptance as either TPP or KMT voters in either wave of our study.

Our findings raise a concern for the future of Taiwanese democracy. TPP supporters were significantly more likely to accept undemocratic practices across both waves. This suggests that those who support the TPP may pose challenges for the future health of Taiwan’s democracy. Although the TPP framed itself and the KMT as the defenders of democracy, our survey data indicate that it may be supporting democracy in name but not necessarily in practice. While scholars have already highlighted that the TPP may represent a populist turn within Taiwan politics, its policies, politics and how much the party may change remain unclear.Footnote 42 This suggests that TPP voters may embody a more anti-establishment voice within Taiwan’s electorate, setting them apart from supporters of the traditional political parties. Beyond the Bluebird movement, Taiwan may not be immune to the rise of the populist forces that have begun to emerge in mature or maturing democracies. In fact, Taiwan may be more similar to democracies worldwide in that it, too, faces an internal anti-establishment backlash.

Finally, these domestic challenges to democratic consolidation are further exacerbated by Taiwan’s contested status and the PRC’s claims over the island. While China and the PRC were not the focus of any party’s framing during the protests, the growing division in Taiwan over which democratic values are worth upholding will make it easier for the PRC to create ways to undermine Taiwan’s democratic system. Although all parties believe they are promoting democracy, the subsequent gridlock they have imposed upon Taiwan’s political landscape has placed the island in a precarious position similar to other democracies that are being undermined by authoritarian powers.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741025101756.

Funding

This project was generously funded by the Republic of China (Taiwan) National Science and Research Council Grant No: 111-2410-H-004 -227 -MY3.

Competing interests

None.

Appendix Table 1. Descriptive Statistics

Appendix Table 2. Timeline of the Legislative Reform

Source: “2024 nian ‘lifaweiyuan xiufa wei ziji kuoda quanli’ shijian bu” (2024 Legislative Yuan: “legislators amending laws to expand their own power”). TBO Taiwan, https://tbotaiwan.com/timeline-no-discussion-not-democracy-2024/.

Lev NACHMAN is an assistant professor in the Graduate Institute of National Development at National Taiwan University. His research focuses on political participation in Taiwan and Hong Kong, US–Taiwan relations and cross-Strait politics.

Wei-Ting YEN is an assistant research fellow at the Institute of Political Science at Academia Sinica. She is a political economist, with a focus on democratic governance and welfare state development in Asia.

Hannah June KIM is an associate professor at the Graduate School of International Studies at Sogang University. Her research examines public opinion, democracy and gender in East Asia.