Introduction

Over the past quarter century, cash transfers targeting families with children have become a central tool in the fight against immediate deprivation while promoting long-term investments in human capital in Latin America. Originating in Brazil and Mexico in the late 1990s and rapidly spreading across Latin America (Borges Reference Borges2022a; Sugiyama Reference Sugiyama2011), the developing world (Brooks Reference Brooks2015) and even the Global North (Medgyesi and Temesváry Reference Medgyesi and Temesváry2013), these programs provide regular transfers to low-income children, mostly conditional on school attendance and medical checkups. By 2020, these programs reached a fifth of the region’s population (Figueroa and Holz Reference Figueroa, Holz, Robles and Holz2024).

The positive effects of these cash transfer programs on income, wellbeing, and development have been well-established (Bastagli et al. Reference Bastagli and Jessica Hagen-Zanker2016; Figueroa and Holz Reference Figueroa, Holz, Robles and Holz2024; Stampini et al. Reference Stampini, Medellín and Ibarrarán2023) and they have been backed by both domestic governments from across the ideological spectrum and by international financial institutions (Arza et al. Reference Arza, Castiglioni, Franzoni, Niedzwiecki, Pribble and Sánchez-Ancochea2022; Borges Reference Borges2022a; Garay Reference Garay2016; Sugiyama Reference Sugiyama2011). However, there is limited understanding of how public opinion supports—or constrains—these policies over time. How do citizens perceive these programs? Do people in highly unequal societies, such as those of Latin America, endorse government efforts to assist vulnerable people through cash transfers? What factors drive their preferences? Would they restrict transfers to only impoverished children or a broader group, and at what level? Responses to these questions should be highly relevant in democratic contexts, where governments are accountable to voters and public opinion can shape policy sustainability. Moreover, examining public opinion on cash transfers for children (CTCs, from here on)Footnote 1 allows us to examine social policy preferences through a concrete, well-known program—avoiding the ambiguities that plague more abstract survey questions such as those measuring support for redistribution (see Margalit and Raviv Reference Margalit and Raviv2024). Finally, public attitudes toward these programs are particularly relevant in Latin America’s dualistic welfare states, as they extend social protection to traditionally excluded labor market outsiders and are more equity-enhancing than most other social policies (Filgueira Reference Filgueira and Bryan1998; Garay Reference Garay2016; Haggard and Kaufman Reference Haggard and Kaufman2008; Lindert et al. Reference Lindert, Skoufias and Shapiro2006). Given the high concentration of poverty among children (46% versus 15% among the elderly (CEPAL 2022)), the expansion in coverage and increase in value of CTCs would be highly redistributive.

Drawing on original, nationally representative surveys of the populations of Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Mexico, and Peru conducted in mid-2022, this article investigates how people in unequal democracies evaluate three dimensions of CTCs: their existence, coverage, and value or amount of transfers. First, we show that the existence of cash transfer policies toward children has become a consensual policy issue, potentially making these programs less vulnerable to significant rollbacks. Second, we show that while the endorsement of the existence of child cash transfer policies is strong, support for the breadth and amount of these transfers varies significantly across countries. We discuss country-level public opinion in relation to existing CTC coverage and amount in each country. Third, we investigate the determinants of individual-level attitudes on cash transfers via logistic regressions on pooled data. We hypothesize that, in addition to ideology and self-interest, gendered social roles and household composition influence people’s attitudes toward child cash transfers. Specifically, we expect that individuals who live with children and care for children are more sensitized to children’s needs and thus supportive of measures to ensure their material wellbeing. Our primary findings lend support to our hypotheses: household composition and especially gender are robust predictors of attitudes toward CTCs. Compared to men, women are more likely to support the existence of these programs, their broader coverage and more generous levels. To partially tease out the potential role of sex versus gender roles, we examine the interaction of sex with other variables and find that support for transfers among women is less affected by income level than among men and women without children are just as likely to back transfers as those with children. Those living with children and of childbearing age are also more likely to favor transfers and broader coverage. Household composition, however, does not significantly affect views on transfer adequacy. Socio-economic factors and ideology also influence attitudes toward transfers, though their influence is less consistent. By showing that gender and household composition shape attitudes toward redistribution independently of self-interest or ideology, our findings contribute to theories of gendered political behavior and challenge models that rely primarily on materialist or class-based explanations of welfare-preferences. Below, we present our literature review, theory, methods, and aggregate findings and individual-level models, and conclusions.

Existing Literature on Public Opinion on Cash Transfer Programs

A growing literature has explored attitudes toward redistribution in Latin America. However, many of its findings are inconsistent across different samples and periods of study. Unlike in industrialized countries, the link between income and support for redistribution in Latin America is inconsistent (Dion and Birchfield Reference Dion and Birchfield2010). Most studies find no direct relationship (Borges Reference Borges2022a; Cramer and Kaufman Reference Cramer and Kaufman2011; Dion and Birchfield Reference Dion and Birchfield2010; Holland Reference Holland2018; Kaufman Reference Kaufman2009), while others show an inverse correlation (Blofield and Luna Reference Blofield, Pablo Luna and Blofield2011; Gaviria Reference Gaviria2007; Haggard et al. Reference Haggard, Kaufman and Long2013; Morgan and Kelly Reference Morgan and Kelly2010). Holland (Reference Holland2018) attributes these inconsistencies to the region’s truncated and regressive welfare regimes, which, by excluding informal workers, leave many of the poorest people with limited reasons to support redistribution and the taxes it may entail (see also Berens Reference Berens2015). Further, Margalit and Raviv (Reference Margalit and Raviv2024) question the usefulness of analyzing support for redistribution in the abstract as most people have a limited grasp of what policies reduce inequality. Analyzing the United States, they find across-the-board support for reducing inequality. However, support for specific redistributive policies differed significantly from abstract support in line with economic self-interest. Our focus on CTCs—a well-known policy targeting poor families with children— circumvents this limitation by assessing a concrete policy. CTCs are prominent, visible, widely known and implemented in highly unequal democracies, offering a rich terrain to study the legitimacy of targeted social assistance.

Counter to industrialized countries, where women are consistently more supportive of redistribution than men (Inglehart and Norris Reference Inglehart and Norris2003; Iversen and Rosenbluth Reference Iversen and McCall Rosenbluth2011), gender effects in the region are also mixed. Some indicate women are more supportive (Gaviria Reference Gaviria2007; Berens and Deeg Reference Berens and Deeg2024), while others suggest the opposite (Morgan and Kelly Reference Morgan and Kelly2010; Holland Reference Holland2018; Borges Reference Borges2022a), and some find no significant difference (Berens Reference Berens2015; Berens and Brady Reference Berens and Brady2024; Hauk, Oviedo, and Ramos Reference Hauk, Oviedo and Ramos2022; Morgan and Kelly Reference Morgan and Kelly2017). Ideological effects are also inconclusive (Blofield and Luna Reference Blofield, Pablo Luna and Blofield2011; Kaufman Reference Kaufman2009).

A large body of research has explored the politics behind adoption of CTCs and other equity-enhancing policies in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Growing electoral competition for low-income people excluded from traditional contributory social benefits prompted governments from across the ideological spectrum to adopt CTCs as well as basic pension programs for low-income older adults (Arza et al. Reference Arza, Castiglioni, Franzoni, Niedzwiecki, Pribble and Sánchez-Ancochea2022; de la O Reference De La O2015; Garay Reference Garay2016). The success of early Mexican and Brazilian CTCs combined with technical assistance and funding from international financial institutions then contributed to the rapid diffusion of these programs across the region (Borges Reference Borges2022a; Osorio Gonnet Reference Osorio Gonnet2020; Sugiyama Reference Sugiyama2011). The rapidity of the diffusion has also been shown to be related to presidents’ expectations of a popularity boost from such programs; presidents fast-tracked CTCs hoping for an increase in popular support (Vega Reference Vega2024).

However, there has been surprisingly little research on public attitudes toward cash transfers—and even less that is cross-national. Studies that do exist point to high levels of support. For example, Layton (2018) finds that nearly 80% of Brazilians favored maintaining or expanding the country’s Bolsa Família CTC. However, persistent negative stereotypes about recipients—such as misuse of funds or increased fertility—undermine support for program expansion (Layton Reference Layton2020). These stereotypes shape preferences for program adequacy and design. Over half of non-recipients believed that the program made recipients complacent, have more children, and that they misused stipends. Older, more educated, and male Brazilians were more likely to hold such stereotypes (Layton Reference Layton2020). These stereotypes go on to shape attitudes toward program coverage. Non-recipients who endorse negative stereotypes were significantly more likely to support reducing or ending the program than those who rejected them. While recipients were unlikely to favor cancelling the program, those who held these stereotypes were less likely to support expansion and more inclined to maintain existing coverage levels (Layton Reference Layton2020).

Gender effects are also mixed. Layton (Reference Layton2020) finds that women are no more likely than men to support expanding Bolsa Família coverage. Similarly, survey data from Mexico conducted by Berens and Deeg (Reference Berens and Deeg2024) finds that women and men were equally likely to support expanding the country’s Prospera child transfer program. These findings are puzzling, given that women, as primary recipients of cash transfers aimed at their children, would be expected to be more supportive of CTCs than men.

The only cross-national study on support for cash transfers among Latin Americans is Waltenberg’s (Reference Waltenberg, Rubén and Vuolo2013) analysis of support for basic income, which analyzes World Values Survey (WVS) data from eight countries. Consistent with economic self-interest, this study finds that support for a basic income is lowest among those with higher levels of life satisfaction, better personal finances, and greater happiness, as well as those with higher educational attainment. Notably, women were more inclined to support a basic income than men. Also in line with economic self-interest, wealthier, more educated, and older Brazilians were more likely to favor reducing Bolsa Família coverage or eliminating the program altogether (Layton Reference Layton2020).Footnote 2 In terms of ideology, voters of Brazil’s left-wing Workers’ Party (PT) were more likely to support expanding program coverage (Layton Reference Layton2020), but this could also be because the PT enacted and subsequently expanded the program.

Relatedly, a wide range of studies have indirectly probed public opinion on CTCs in Latin America by analyzing the electoral effects of these programs. In a clear example of retrospective economic voting, cross-national research utilizing diverse methodologies finds robust evidence that receiving these programs increases support for the current government (Manacorda et al. Reference Manacorda, Miguel and Vigorito2011) and electoral support for presidential candidates from incumbent parties (de la O Reference De La O2015; Layton and Smith Reference Layton and Erica Smith2015; Zucco Reference Zucco2013). At the same time, there is evidence that CTCs may have anti-incumbent effects among many non-recipients, who may be more inclined to vote for the opposition (Correa and Cheibub Reference Corrêa and Antonio Cheibub2016). We would thus expect transfer recipients to be more likely to support the programs than non-recipients.

Our Theoretical Expectations

Our study draws on three broad frameworks: ideology, self-interest, and gendered social roles and household composition:

Self-interest. We hypothesize that respondents with lower socio-economic status, those facing greater economic vulnerability, women as preferred recipients, and current recipients of CTCs and other targeted assistance will be more supportive of these programs. We also expect older, wealthier, male, non-recipient, and more educated individuals to be less supportive, consistent with Layton (Reference Layton2020) and others.

Ideology. We expect that respondents who are left-leaning, support redistribution, or back parties associated with social spending will show greater support for child cash transfers. This follows a long literature on ideological influences on welfare attitudes (Alesina and Glaeser Reference Alesina and Glaeser2004; Margalit Reference Margalit2013).

Gender and care work. Women are disproportionately responsible for unpaid care work across Latin America as elsewhere, (Daly and Lewis Reference Daly and Lewis2000; Filgueira and Martínez Franzoni Reference Filgueira and Martínez Franzoni2019; Folbre Reference Folbre1994; Iversen and Rosenbluth Reference Iversen and McCall Rosenbluth2011; UNW 2017) and are generally the main recipients of child-focused CTCs. In four Latin American countries, women in their thirties averaged 7.5 hours of unpaid work daily, while men averaged under two (UNW 2017). Based on this, we expect that they may be more sensitized than men to the needs of children and thus more supportive of cash transfers to them.

Gender, care work, and socio-economic status. Lower-income Latin American women spend significantly more time on domestic responsibilities than wealthier women or men (Filgueira and Martínez Franzoni Reference Filgueira and Martínez Franzoni2019). Women aged 26–30 in the lowest income quintile dedicate 8–9 hours daily to care work, compared to 3–5.5 hours among those in the highest quintile, while men across all income levels spend only 1–2.4 hours (UNW 2017). We expect thus that lower-income women are more sensitized to the needs of children than higher-income women and are thus more supportive of cash transfers to them. While we theorize that women—especially those with fewer resources—may be more attuned to children’s needs due to their disproportionate caregiving responsibilities, our data cannot empirically distinguish this mechanism from self-interest, since the same individuals who are more involved in care are also more likely to benefit materially from cash transfers.

Household composition. In addition to the above factors, we hypothesize that the household level may shape peoples’ views on cash transfers. Households function as units of economic cooperation and reciprocity (Blofield et al. Reference Blofield, Filgueira and Diana Deere2018; Therborn Reference Therborn2004). As such, households could be interpreted as a broader form of self-interest. In line with feminist theorists, it can also be interpreted that those living with children may develop an “us-interest” rather than a purely individual self-interest (Folbre Reference Folbre2002; Jelin Reference Jelin1998; Martínez Franzoni Reference Martínez Franzoni2008; Sen Reference Sen and Tinker1990). Living with children may enhance support for CTCs, as individuals living with children are more sensitized to children’s needs and thus supportive of CTCs.

Policy legacies. We expect policy legacies concerning government efforts around anti-poverty measures to influence people’s attitudes toward CTCs on both a national and a household level, in line with existing literature (Pierson Reference Pierson2000; Niedzwiecki and Pribble Reference Niedzwiecki and Pribble2017). We expect individuals living in countries with broader and more adequate CTCs to be more supportive of them. We also expect individuals who live in households that have recently received cash transfers to be more supportive of them. While these expectations reflect the influence of policy legacies—where prior exposure to effective CTCs may foster support—the effects are empirically indistinguishable from self-interest, as those who have benefited from such programs are also more likely to support their continuation for material reasons.

These expectations guide our empirical analysis of public attitudes toward child-focused CTCs across seven Latin American countries. We explore overall support, preferred coverage, and perceived adequacy of benefits—both regionally and within each country.

Data and Empirical Strategy

This study is based on original, nationally representative surveys of the populations of Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Mexico, and Peru conducted in mid-2022. Countries were selected with the aim of maximizing variation in level of economic development and geography (South, Central, North America) among formally democratic Latin American countries with at least a decade of CTC programs in operation.Footnote 3

The surveys were conducted via telephone due to pandemic-related constraints on face-to-face interviews. Telephone surveys are a reliable alternative during emergencies (Holt Reference Holt2010; Hoogeveen and Pape (Reference Hoogeveen and Pape2020) and were successfully used by the Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP) during the pandemic (Zechmeister Reference Zechmeister2020). Fieldwork was led by Blofield and Martínez Franzoni in collaboration with leading polling firms in each country.Footnote 4 The surveys used random stratified sampling with a 95% confidence level and a maximum +/−3% margin of error. Sample sizes ranged from 900 (Chile) to 1,503 (Guatemala), totaling 7,549 respondents across the seven countries. The survey included 37 predominantly closed-ended questions to ensure consistency. The survey questionnaire is provided in the Supplementary Material.

Our empirical analysis is twofold. We first compare the overall and national levels of support for the existence of cash transfer programs for children and three other vulnerable population groups: the elderly, the unemployed and immigrants. We then do the same for attitudes toward coverage and toward adequacy of CTCs. The findings are then put into context by comparing them with the cash transfer legacies of each country. Second, we examine individual-level determinants through logistic regressions on attitudes toward cash transfer programs across the three dimensions of support, adequacy and breadth of coverage.

Descriptive Findings

We begin by presenting the main findings of the surveys in terms of support for CTCs for children and preferences toward CTC adequacy and breadth of coverage and comparing them across countries. Full descriptive findings are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Values on Transfer Support for Population Groups in the Overall Sample and on the Dependent Variables for the Seven Latin American Countries.

Support

A broad consensus exists in favor of cash transfers targeting children. Overall, nine in ten (90.0%) respondents agree that their government should provide cash transfers to children (70.4% agreed and 19.7% strongly agreed). Cross-national variation in support is limited, ranging from 84.6% (Argentina) to 92.9% (Colombia). Support for transfers to children is minimally lower than for transfers to the elderly (92.2%). This indicates that there exists a strong social consensus across all the countries surveyed in support of the existence of cash transfer programs for both the young and the old. This support is substantially higher than that for transfers for people who are unemployed (69.2%) and especially for people who are migrants (42.3%). Notably, support for transfers to children is also substantially higher than support for redistribution in the abstract across these countries (68.6%).Footnote 5

Adequacy

Respondents were also asked what the value of cash transfers for children should be, choosing from four levels: half the cost of the basic food basket, the cost of the basket, the basket plus clothing, and the basket plus clothing and other basic needs. A basic food basket corresponds to the national extreme poverty line and the food basket plus clothing and other basic needs corresponds to the national poverty line. The results reveal overwhelming support, across all countries, for cash transfers equivalent to at least the extreme poverty line. Among those expressing support for transfers, less than 3 percent (2.9%) preferred transfers equal to half a basic food basket. A third (33.4%) favored transfers equal to a full food basket (i.e., extreme poverty line) and just over half (50.1%) preferred the most adequate option, corresponding to the poverty line. Although support for the least adequate option is minimal in every country, clear cross-national differences in adequacy preferences exist. Chileans were the most likely to support cash transfers at the poverty line (61.4%), the most generous option, while Guatemalans were the least likely (36.8%) to do so. At the other end, Mexicans were the least likely (1.3%) and Costa Ricans the most likely (4.2%) to support the most meager option.

Breadth

There is significantly more disagreement on which children transfers should cover. Interviewees were asked to pick among four coverage levels: only children living in extreme poverty, only poor children, most children, or all children. Among those who support transfers, almost half (47.2%) favor limiting transfers to those in extreme poverty. A quarter (25.5%) support universal transfers. Preferences vary substantially by country, with support for limiting transfers to children in extreme poverty ranging from 28.3% (Chile) to 57.9% (Peru) and support for universal transfers ranging from 19.3% (Colombia) to 40.6% (Chile).

In sum, public opinion in the seven countries analyzed reflects a broad social consensus on the existence of cash transfer programs for children and the elderly, reflecting the policy expansion the region has undergone over the past quarter century. This indicates that there is very little support in the region for the dismantling of these programs. Second, the surveys indicate that public opinion overwhelmingly supports adequacy levels set at least at the extreme poverty level, although there is more variation regarding support at a higher level. Finally, coverage is the most divisive dimension of child cash transfer support, with almost half supporting restricting transfers to children in extreme poverty and a quarter supporting universal transfers. Next, we explore country-level variation in existing cash transfer policies and public opinion.

Exploring Cross-National Variation on Breadth and Adequacy

We explore how national-level program features and cash transfer legacies relate to cross-national variation in public preferences. The small number of countries surveyed does not allow for the use of multi-level models that systematically analyze the impact of national-level factors on individual preferences (Stegmuller Reference Stegmueller2013). Instead, we qualitatively compare public opinion with country-specific program features.

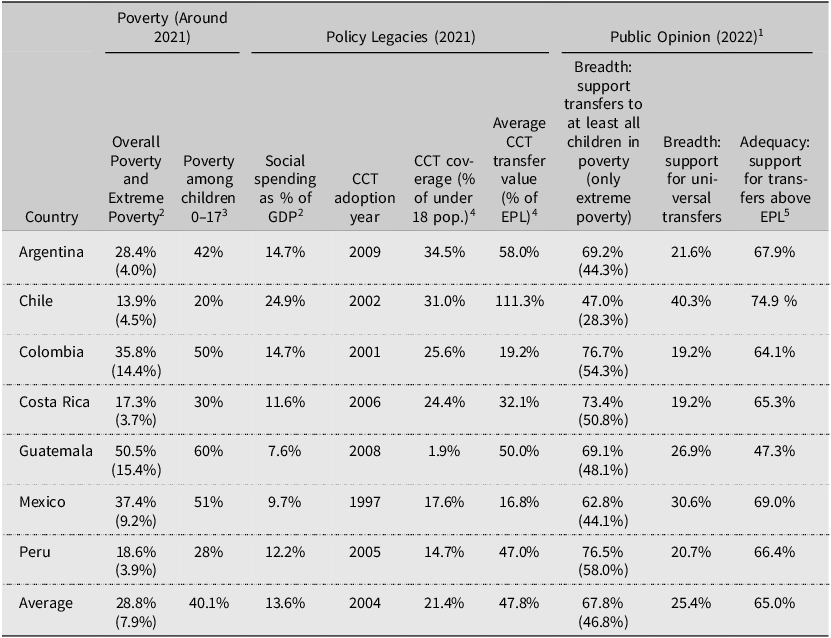

As Table 1 indicates, all seven countries had CTC programs in existence for over a decade at the time of the survey, even if most changed names and program features over time. Mexico had the longest CTC legacy, with the establishment of the national-level Oportunidades program in 1997. Current national cash transfer policies are captured through child cash transfer enrollment (as a share of the under-18 population) and adequacy (as a share of the extreme poverty line) and social policy legacies are captured via social spending as a share of GDP.Footnote 6 We also include poverty and extreme poverty rates and child poverty rates to assess current CTC coverage in relation to need.

Table 1. Poverty Rates, Policy Legacies and Attitudes Toward CCT Breadth and Generosity

Although all seven countries have CTCs, they differ greatly in terms of coverage, ranging from Chile and Argentina on the high end, with over 30% coverage among under 18-year-olds, to Guatemala on the low end, with under 2% coverage. Table 1 also indicates that, even assuming perfect targeting, in six of the seven countries CTC coverage falls short of child poverty levels. Only in Chile do CTCs reach a higher proportion of children than those living in poverty. Coverage gaps range from 5.6% of children in Costa Rica, to 7.5% in Argentina, 13.3% in Peru, 24.4% in Colombia, 33.4% in Mexico, to a whopping 58.1% in Guatemala, a very large gap between social needs and state reach.

Similarly, the value of CTCs varies significantly across countries as well, from a low of 16.8% of the extreme poverty line in Mexico to 111.3% of the extreme poverty line in Chile. The variation in values should be taken with some caution, however, as these values reflect pandemic-era boosts and thus may not reflect longer-term values; for example, the value of Chile’s CTC in 2019 was one-tenth of what it was two years later (Blofield et al. Reference Blofield, Pribble and Giambruno2023). Coverage numbers on the other hand did not fluctuate much in relation to pandemic-era boosts in assistance, as coverage increases were reflected in the creation of new emergency cash transfer programs (Blofield et al. Reference Blofield, Pribble and Giambruno2023).

We can interpret national-level public opinion in relation to these programs. In Chile, where programs are broader and more adequate, public opinion is also supportive of more adequate and, particularly, broader cash transfer programs. In the remaining countries, narrow majorities support either extending programs to at least all children in poverty or restricting them only to children in extreme poverty. In Argentina, Mexico, and, interestingly, Guatemala, narrow majorities (52–54%) support extending cash transfers to at least all children in poverty, thus supporting an expansion of coverage from current levels. In Colombia, Costa Rica, and Peru, on the other hand, narrow majorities favor restricting transfers to the extremely poor, while between 40–45% of respondents support extending cash transfers to at least all children in poverty.

In 2021, the year before our surveys were conducted, Chile had the region’s highest level of social spending, reaching nearly a quarter of GDP, and the lowest poverty rates, particularly among children. In contrast, Guatemalan social spending as a share of GDP amounted to just one-third of Chile’s level while more than half of the population lived in poverty, including 60% of minors. Despite these stark differences, respondents across all seven countries supported benefit levels in 2022 that were more generous than those in place at the time. This indicates that there is political space to increase the value of these transfers across all countries.Footnote 7

Our cross-sectional public opinion data on its own does not allow us to infer causality or directionality. What does emerge is a clear general association between policies and public support and, specifically, public opinion that is overall conducive to further boosting CTC programs, especially in terms of adequacy levels. At the same time, Table 1 reveals country-level differences in coverage that largely mirror a robust literature that has charted the different welfare regime types underpinning these policy differences, from Guatemala’s exclusionary regime (Filgueira and Filgueira Reference Filgueira, Filgueira and Huber2002; Martínez Franzoni Reference Martínez Franzoni2008) to Peru and Colombia’s dualist models; to Mexico’s pioneering legacy in establishing conditional cash transfer programs but with weaker expansion since the millennium; to Costa Rica’s historically more universalist regime but with a weaker cash transfer dimension (Huber Reference Huber and Esping-Andersen1996, 159–60); and finally to Argentina and Chile’s more extensive basic universalism (Arza et al. Reference Arza, Castiglioni, Franzoni, Niedzwiecki, Pribble and Sánchez-Ancochea2022; Filgueira Reference Filgueira and Gerardo Molina2006; Pribble Reference Pribble2013). A robust literature has also charted the determinants of these policy differences (see for example de la O Reference De La O2015; Garay Reference Garay2016; Pribble Reference Pribble2013).

Chile presents an interesting case. Three decades of incremental reforms to its neoliberal model resulted in a more inclusive welfare model in absolute terms than almost any of its regional counterparts. Yet persistent inequality and perceived lack of upward mobility culminated in 2019 in mass protests against the country’s economic model (Palacios-Valladares Reference Palacios-Valladares2020). The aftermath of this Estallido Social saw significant discussion of expansive reforms including a universal basic income and a more egalitarian pension system. Though the basic income proposals did not prosper, the protests and extensive discussions may be related to the more universalist and generous public opinion among Chilean respondents.

In the rest of the countries, coverage preferences are less universalist. Argentina has the highest CTC coverage through its Asignación Universal por Hijo (AUH) transfer program and high social spending overall. Interestingly, public opinion is not as expansive as in Chile, with only a narrow majority supporting covering at least all children in poverty, which is four out of ten children in the country. A significant plurality (44.4%) favor restricting transfers to children in extreme poverty. Argentina’s lower numbers appear to be part of a broader trend in declining support for redistribution amid that country’s severe economic crisis and the election of far-right libertarian Javier Milei as president who campaigned on promises of austerity. Whereas during 2008–12, 85.2% of Argentines surveyed by LAPOP agreed that the government should enact policies to reduce inequality (5 or higher on 7-point scale), that figure had dropped to 65.8% in 2023. Those expressing the strongest level of support (7) declined by almost half from 57.3% to 33.5% during that period while those least supportive of redistribution (1) more than quintupled from 1.4% to 7.5%.Footnote 8 The contrasting survey results for Chile and Argentina highlight the role recent domestic political events may have on social policy attitudes.

In Mexico and especially in Guatemala, existing coverage is much lower than what public opinion would support. Over one in three Mexicans support universal transfers, and 54% support transfers to at least all children in poverty. Mexicans’ more expansive attitudes may reflect the country’s pioneering legacy in establishing these programs in the late 1990s, and, more recently, a political transformation that has brought to power successive left-wing governments that campaigned on expanding social policy. Under Andrés Manuel López Obrador (2018–24) basic pensions were universalized and the country’s highly targeted conditional cash transfer program was replaced with more broadly targeted unconditional cash transfers for school-aged children (Borges Reference Borges2025). In Guatemala, despite an extremely weak social policy legacy and negligible existing CTC coverage, over half of the respondents (52.2%) support expanding CTCs to all children in poverty, which would increase current program coverage thirty-fold relative to 2021 levels. Ten years earlier, in 2012, CTC coverage had experienced a short-term boost to close to one-third of children in poverty during the presidency of Álvaro Colom (Blofield et al. Reference Blofield, Franzoni and Ángel Oviedo2024). It may be that this experience, combined with high poverty, has created unmet expectations among the population. At the same time, a slight majority of Guatemalans favors establishing the value of cash transfers at the basic food basket, extreme poverty level, which may be reflective of the much lower average living standards in Guatemala compared to the other six countries.

Respondents in Peru, Colombia, and Costa Rica favor more restrictive programs, with just over half of respondents supporting transfers only to children in extreme poverty and less than one in five supporting universal transfers. Peru and Colombia prior to 2022 were marked by restrictive and targeted social policy legacies and the absence of a significant and programmatic left, which may be reflected in their more conservative attitudes. Surprisingly, Costa Ricans’ attitudes are also more restrictive despite a more universalistic historical welfare regime legacy (Huber Reference Huber and Esping-Andersen1996, 159–60; Martínez Franzoni and Sánchez-Ancochea Reference Martínez Franzoni and Sánchez-Ancochea2016, Part 3).

Explaining Individual-Level Support

Individual-level preferences toward transfers targeting children are analyzed through binary logistic regressions. The models examine the three dimensions of support through five binary dependent variables: first, whether respondents support such programs; second, on the value of the transfer: whether they support the least adequate transfer option (half a basic food basket, equivalent to half the extreme poverty line), and whether they support the most adequate option (full basket plus the cost of clothing and other needs, equivalent to the poverty line); third, on coverage: whether transfers should be limited to children living in extreme poverty, and whether they should cover all children.Footnote 9 To account for cross-country variation, all models include country-fixed effects.

The explanatory variables seek to distinguish the impacts of gender, household composition, socio-economic status, and ideological orientation. Gender is measured as a binary variable. Household composition is captured by a binary variable measuring whether children live in the respondent’s household and three age categories: reproductive age (18–49 years), elderly (65 years and over) and middle age (50–64) as a baseline.

Regarding socio-economic status, income is measured, following LAPOP, by calculating an index of household assets and services (see Córdova Reference Córdova2009), and education is measured categorically from no formal education to university education. Further, two binary labor market variables are also included: access to social security benefits, indicating past or present formal-sector employment; and income received from a current job or pension. Finally, the models include dichotomous variables measuring whether the respondent received cash or food aid during the previous two years.

Four variables capture ideological orientation. Political affiliation is measured by asking respondents if and who they voted for in the most recent presidential election. Vote choices were then coded as left or center/right based on candidate ideology. Attitudes toward inequality and taxation are measured using five-point Likert scale variables. Respondents were asked to what extent they agreed that “the rich have too much, and the poor have too little” and to what extent they would support a new social program funded by “raising taxes on the richest people.” Prioritization of social policy is measured through a question asking whether they would give additional resources to the police or to social programs. This also taps into whether respondents support “iron fist” policies versus addressing root causes of criminality.

All models control for whether respondents live in an urban area, are a minority (not white or mestizo), and identify as an Evangelical Christian.

Support for Transfers

Figure 2 presents the results and confidence intervals of the determinants of support for CTCs. Full regression models are available in Table 1 (Supplementary Material). Model 1-1 analyzes the full sample. Models 1-2 and 1-3, respectively, restrict the sample to women and men. The analysis reveals that gender and household composition consistently impact support for cash transfers. Most notably, transfer support is greater among women, people living with children, and people of childbearing age. Ideological and socio-economic factors also shape support as predicted. However, surprisingly, having received transfers or food aid does not affect the likelihood of supporting transfers.

Figure 2. Determinants of Support for Cash Transfers for Children.

Model 1-1 finds strong support for explanations based on gender and household composition. Being a woman, living with children, and being of reproductive age all have statistically significant positive impacts on the likelihood of supporting transfers.

The impact of socio-economic status is less robust. Although the likelihood of supporting transfers declines in line with education, neither income nor labor formality influence support for transfers. People receiving labor income are less likely to support transfers, though this finding is significant only at the 0.10 level.

Notably, counter to self-interest, people whose households have received cash transfers or food aid are no more likely than non-recipients to support transfers. The shares of recipients opposed to these policies (8.7% and 7.2%, respectively) are not substantially different from the shares among non-recipients (10.7% and 11.2%). Unfortunately, our data does not allow us to dig deeper into why benefiting from these programs does not make people more likely to support transfers.

Taken together, the type of respondent most likely to benefit materially from transfers—a woman of reproductive age, living with children, with no formal education and no labor income—is practically guaranteed to support transfers (97.4%). In contrast, an older man, not living with children, who has a university education, and labor income has a 79.5% probability of supporting transfers, a 17.9 pp difference.

Ideological orientation also influences support for transfers. Support is significantly higher among those who voted for left-wing candidates, believe the rich have “too much,” support higher taxes on the rich, and who favor social to police spending. The cumulative impact of ideological orientation is larger than that of gender, household composition, and socio-economic status. A respondent least inclined toward redistribution—voted for a centrist or right-wing candidate, strongly disagrees that the rich have too much and should be taxed more, and favors police funding—has a 75.8% likelihood of supporting transfers. In contrast, the person most ideologically predisposed to redistribution has a 96.8% likelihood, a 21.0 pp difference.

To verify if these results are being driven by specific countries, we re-run model 1-1 excluding each country (see Table 3 in Supplementary Material). The most notable finding is that the impact of gender is greatly influenced by Guatemala. Gender fails to achieve statistical significance when that country is dropped from the analysis. Although a larger share of women than men support transfers in every country, that gap is particularly large in Guatemala—6.1 pp versus 2.8 pp for the entire sample. This may reflect higher gender role socialization in Guatemala compared to the other countries in the survey, but requires further research. In contrast, the impacts of living with children and being of reproductive age are robust to the exclusion of any of the countries.

Regarding ideology, the impact of voting for the left loses significance when Argentina is dropped from the sample. Although in every country left-wing voters are more likely to back transfers than centrist and right-wing voters, Argentina’s gap (16.8 pp) is almost three times larger than that among the full sample (6.1 pp).Footnote 10 Argentina’s large gap likely reflects the country’s politics, which at the time of our survey was among the world’s most polarized, with 64% of Argentines agreeing with the statement that Argentina is today more divided than before (Edelman 2023). The other variables measuring ideology are robust to the exclusion of any of the countries.

Education’s negative impact is robust to the exclusion of any country. Further, the lack of impact of receiving cash transfers or food assistance is robust to the exclusion of any of the countries.

Teasing Out the Impact of Gender Roles

The next set of models attempts to distinguish between economic self-interest and claims that women are more responsive to the needs of children independent of their economic situation. This is done in two ways. First, the prior analysis is replicated analyzing women and men separately. Second, a multiplicative interaction term between living with children and income level is added to the models presented in Figure 1. In support of the view that women’s attitudes are influenced by factors beyond economic self-interest reflecting gender roles or socialization, we find that women not living with children are as likely as those living with children to support transfers. Further, we find that, whereas the likelihood that a man will support transfers declines as his income increases, the likelihood that a woman will support transfers is barely affected by her income level.

Models 1-2 and 1-3 respectively analyze women and men separately. Their most notable finding is that the positive impact of living with children is driven entirely by male respondents. Living with children has a statistically significant positive impact only among men, indicating that women not living with children (and thus unable to benefit materially from transfers) are just as likely to support transfers as those living with children. Similarly, although education negatively affects support for transfers in both models, its impact is larger among men. Men without formal education are 7.4 pp more likely to support transfers than those with university education, compared to a difference of 4.4 pp among women (60% as large). Together, these findings lend support to our hypothesis that women, through gender role socialization, may be driven by greater responsiveness to children rather than simply self-interest. Men, on the other hand, may be less sensitized to children and their needs when they do not interact with them daily in their own households.

To further explore the impact of gender roles and socialization, we introduce multiplicative interaction terms between income level and living with children. These models find that income influences support for transfers indirectly through household composition and that this finding can be attributed primarily to men. The interactions are presented in Figure 3. Full regression models are available in Table 1 (Supplementary Material).

Figure 3. Marginal Effect of Living with Children on Support for Cash Transfers for Children across Income Quintiles.

Beginning with the full sample, the left-hand panel of Figure 3 shows that living with children has a positive impact on support for transfers, but this effect declines and ultimately disappears as income rises. Specifically, respondents in the bottom quintile with children are 5.1 pp more likely to support transfers than those not living with children. This effect declines to 3.8 pp and 2.6 pp among those in the next two quintiles and disappears entirely among the top two quintiles.

Breaking down this analysis by sex reveals that men are the primary drivers of the interaction. The right-hand panel of Figure 3 shows that bottom-quintile men with children are 6.7 pp more likely to support transfers than comparable men without children. This effect declines with income, dropping to 5.0 pp and 3.4 pp for the second and third quintiles before disappearing entirely for the top two quintiles. In contrast, the center panel of Figure 3 shows that, among women, the positive impact of living with children is only significant among those in the bottom quintile. Further, the magnitude of that impact (3.5 pp) is less than half that among men in the bottom quintile and barely statistically significant (p = 0.048).

The findings for the sample as a whole and among men are robust to the exclusion of any of the countries in the sample. Among women, the interaction is not robust, losing all significance if any of four countries are excluded.

However, some findings contradict our argument. Disaggregating by gender reveals that the negative impact of receiving income from labor is driven primarily by women. Similarly, the positive impact of being of reproductive age is significantly larger among women.

Transfer Adequacy

Figure 4 presents the results and confidence intervals for the analysis of the determinants of transfer adequacy and breadth among those who expressed support for transfers. Full regression models are available in Table 2 (Supplementary Material). Model 2-1 presents the determinants of support for the least adequate transfer option (half the cost of the basic basket). Model 2-2 presents the determinants for the most adequate option (basic basket plus the cost of clothing and other expenses).

Figure 4. Determinants of Attitudes on Coverage and Generosity of Cash Transfers Covering Children.

The analysis yields three main findings. First, compared to men, women are more generous when it comes to CTCs: they are less likely to support the least adequate transfer option and more likely to support the most adequate one. Whereas a typical man is 50% more likely than a comparable woman to support the least generous option (2.34% vs. 1.54%), the typical woman is 13% more likely to support the most generous option (54.8% vs. 48.4%). The former finding is robust to the exclusion of every country other than Colombia (Table 4 [Supplementary Material]) while the latter is robust to the exclusion of any of the countries (Table 5 [Supplementary Material]).

Second, counter to findings for support and breadth, neither living with children nor being of reproductive age influences transfer adequacy preferences. Interestingly, people over 65 are less likely than those aged 50–64 to favor the most generous transfers.

Third, the impact of socio-economic status is mixed. In line with economic self-interest, higher-income individuals are more likely to support the least adequate option but no less likely to support the most generous one.Footnote 11 Moving from the bottom to the top income quintile nearly doubles the likelihood of supporting transfers equal to half the basic basket (1.2% to 2.0%). Against the argument that the impact of self-interest is weaker among women, this finding is significant only among women and not men (Table 6 [Supplementary Material]). Counter to economic self-interest, educational attainment, though unrelated to support for the least adequate option, correlates positively with support for the most adequate one. A typical person with university education is 20% more likely to support the most adequate transfers than one with one with only primary education (60.7% vs. 50.3%). The remaining socio-economic variables—receiving labor income and formal employment—do not affect attitudes towards adequacy.

Puzzlingly, those who received food aid are more likely to favor the least adequate transfers. Further, this finding is driven primarily by women (Table 6 [Supplementary Material]). In contrast, receiving cash transfers does not influence preferences concerning adequacy. Ideology’s impact is also mixed. As predicted, those who support higher taxes on the rich are less likely to support the least adequate transfers and more likely to support the most adequate ones. An otherwise typical person who strongly disagrees that the rich pay “too little” is more than twice as likely to support transfers equal to half the basic basket than a comparable person who strongly agrees (2.4% vs. 1.2%). Conversely, people who strongly agree are almost one-fifth (18.2%) more likely to support the most adequate transfers (58.4% vs. 49.4%). Similarly, people who prioritize police spending over social spending are less likely to support the most adequate transfers, but this finding is only significant at the 0.10 level. Those prioritizing police spending are no more likely to support the least adequate transfers. Voting for the Left and attitudes on inequality do not impact either dependent variable.

Transfer Breadth

Finally, we examine breadth preferences among those who support transfers. Model 2-3 presents the determinants of support for the least expansive coverage option (only children in extreme poverty). Model 2-4 presents the determinants for the most expansive option (transfers covering all children).

The analysis of transfer breadth yields three main findings. First, women are less likely than men to support limiting cash transfers to children in extreme poverty, supporting the claim that they favor more expansive transfer programs. However, women are no more likely than men to support universal transfers. Second, consistent with prior findings on household composition, respondents of reproductive age and those living with children are more likely to support universal transfers and less likely to restrict them to those in extreme poverty.

Taken together, gender and household composition have sizable impacts. A reproductive-age woman with children is about 70% more likely to support universal transfers than a man aged 40–64 years without children (29.4% vs. 17.4%). Further, the former is only about three-quarters as likely as the latter to support targeted transfers (43.7% vs. 59.7%). The finding on gender, however, loses statistical significance if Costa Rica, Mexico, or Peru are excluded from the analysis. The household composition findings, in contrast, are robust to the exclusion of any country in the sample (see Tables 7 and 8 [Supplementary Material]).

Dividing the sample by gender provides further support for the claim that women’s preferences are less influenced by self-interest than those of men (see Table 9 [Supplementary Material]). Although significant among both genders, the negative impact of being 18–49 (versus being 50–64) years on support for targeted transfers is about a third larger among men (10.0 vs. 7.7 pp). Similarly, the positive impact on the support for universal transfers of being 18–49 years, although significant for both genders, is also larger among men (6.7 pp vs. 5.9 pp). However, counter to gendered arguments, the impact of living with children on both dependent variables is only significant among women.

Third, in line with economic self-interest, higher-income individuals are more likely to support targeted transfers and less likely to favor universal ones. Compared to those in the top quintile, respondents in the bottom quintile are 4.5 pp less likely to support targeted transfers and 4.7 pp more likely to support universal ones. Income’s impact is driven primarily by women and is not significant among men. A woman in the bottom quintile is 8.9 pp more likely to support universal transfers and 5.3 pp less likely to support targeted transfers than one in the top quintile. The latter finding, however, is only significant at the 0.10 level. Similarly, individuals with higher levels of education are less likely to support universal transfers, though they are no less likely to support targeted ones. Notably, education’s negative impact is driven primarily by men and is absent among women. Thus, counter to material interest, the transfer breadth preferences of highly educated women are no different than those of their less educated counterparts.

We observe a slight effect of being a cash transfer recipient on breadth preferences: recipients are less likely to prefer limiting transfers to those in extreme poverty (by 3.4 pp) but no more likely to support universal transfers. In contrast, receiving food aid does not affect coverage preferences.

Finally, ideology is not a consistent predictor of breadth preferences. As predicted, those favoring social over police spending and those who believe that inequality is too high are less likely to support targeted transfers but, against expectations, no more likely to support universal ones. Also counter to expectations, those more inclined to tax the rich are both more likely to support targeted transfers and less likely to support universal ones. Finally, voting choices do not influence breadth preferences.

Discussion

Taken together, the individual-level analysis highlights several interesting results. First, these findings overall reinforce the existing literature that predicts that both self-interest, as measured through socio-demographics such as gender, age, income and education, on the one hand, and ideology, on the other hand, influence attitudes toward social policy. Second, the findings overall also give support to our hypothesis that the household level—specifically living with children—may predispose individuals to be more receptive to CTCs, especially men. Third, the most striking non-finding, or, counter-intuitive finding, is that being a cash transfer or food assistance recipient has virtually no impact on transfer preferences.

All in all, the analysis reveals quite distinct sociodemographic profiles of individuals who most typically and most strongly favor broad and generous transfers, and vice versa. A typical woman of reproductive age with children in the household has a 95% likelihood of supporting transfers, 54% likelihood of supporting the most generous transfers, and a 30% likelihood of supporting universal coverage. In contrast, a typical man 65 years of age or over with no children in the household has an 88% likelihood of supporting transfers, 42% likelihood of supporting the most generous transfers, and just a 14% likelihood of supporting universal coverage.

On a national level, our findings are more tentative due to the small number of cases. They suggest that while there is some association between cash transfer legacies and public attitudes toward CTC coverage and adequacy, the relationship is not linear or uniform. In some cases, stronger legacies of inclusion—such as in Chile—are associated with robust public support for universal and generous transfers. In others, like Argentina, similar legacy strength does not correspond to equally strong support, possibly due to recent political and economic upheaval that has reshaped preferences and trust in redistribution. Conversely, we observe surprisingly strong support for expanded transfers in Guatemala and Mexico, countries with comparatively weak or highly targeted social policy legacies. In Guatemala, the near absence of CTC coverage amid high poverty and a previous short-term experience of higher coverage may have created unmet expectations. In Mexico, support may be explained by a combination of its pioneering role in CTC adoption and recent expansions under left-leaning governments. By contrast, countries with intermediate CTC coverage, like Colombia, Peru, and, to some extent, Costa Rica display more conservative public attitudes, favoring narrowly targeted transfers. Taken together, these patterns suggest a non-linear relationship between policy legacies and public preferences.

There are at least three limitations to this study. First, the survey did not ask about conditionalities due to time constraints; we therefore cannot speak directly to the literature that addresses conditionalities. Second, our study was conducted two years after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, which may have influenced people’s attitudes in ways we have not accounted for. Third, and relatedly, as our data is cross-sectional we cannot infer trends or causality. Ideally, further studies with representative surveys could build on these findings to explore attitudes over time.

Conclusions

Bringing together the national-level aggregate data and individual-level data, a few striking conclusions emerge. First, after several decades of democratic politics, and at least a decade of cash transfer programs, our original, seven-country data set shows that an overwhelming majority across a pretty representative sample of democratic countries in the region supports government action to eliminate extreme poverty among children. Almost 90% of respondents support the existence of a CTC program, and 97% support providing at least basic food basket-level transfers, thus providing a strong mandate for the eradication of extreme poverty.

Aside from being a compelling mandate for policy action, this finding is theoretically interesting. Our results show that cash transfer programs for children are ingrained in Latin America’s social policy, and their existence has achieved a high level of consensus and democratic legitimacy across material and ideational divides. It questions the literature that claims that only universal policies can create broad-based public support (see, for example, Gelbach and Pritchett (Reference Gelbach and Pritchett2002).

Beyond this, clear differences emerge in national-level and individual-level preferences on coverage and adequacy. The national-level patterns across the seven countries suggest a non-linear relationship between policy legacies and preferences on especially coverage. This calls for further research on how, in unequal democracies, legacy effects interact with current political developments. Our individual-level findings challenge existing assumptions about who supports cash transfer programs and why. Although ideology and income are indeed significant predictors, we find that gender and household composition are more robust and consistent factors. Women, especially those of working age who live with children, are substantially more likely than men to favor broader and larger transfers. These findings indicate that caregiving tasks and gendered roles may give direction to social policy attitudes beyond conventional economic theories of individual interest or class redistribution, underscoring the importance of incorporating gender and caregiving roles into welfare preference models. The gendered patterns of support point to the need for welfare state theories to more explicitly consider how the household level and social reproduction shape political preferences. Finally, strikingly, recipients themselves do not report markedly higher support for CTCs than non-recipients, a finding that calls for further investigation.

These findings have important implications for theories about social policy preferences and welfare state expansion in unequal democracies. First, they demonstrate the value in examining specific policies like cash transfers as opposed to abstract questions involving redistribution, which people may have less experience of and interpret in very different ways. Second, they indicate that public support for concrete social policies such as cash transfers for popular vulnerable groups like children and older people is strong in the region, even if coverage and adequacy preferences vary. Third, the findings point to the importance of including the household level as a variable in analyses of political preferences. From a policy perspective, given the continued increase in the share of households with children that are headed by women, and marked by the absence of adult men, the survey finding that men who do not live with children are less supportive of CTCs carries worrying implications regarding the continued support for policies addressing children’s needs. Finally, the analysis points to the need for further empirical studies on cash transfer preferences over time and across countries.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/lap.2026.10046

Data availability statement

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge research and technical assistance by Jorge Rincón and Luis Ángel Oviedo and data analysis contributions on an early draft by Daniela Osorio Michel. The authors gratefully acknowledge funding from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) for project no BL 1797/1-1, which made the research possible.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.