Introduction

In the 2015 migration crisis in Western Europe, asylum seekers were often housed in communities – small towns and rural areas – that had not, until then, experienced significant large‐scale immigration.Footnote 1 Did the people in these communities notice the presence of asylum seekers, and what type of contact occurred, if at all? How did people in these communities react to the sudden influx of outsiders? And did reactions go beyond opinions about asylum seekers, also affecting immigration attitudes and party preferences? We study these three questions using survey data matched with municipality‐level asylum seeker information in Austria, a country strongly exposed to the crisis. To estimate the causal impact of asylum seeker presence, we exploit partly exogenous placement of asylum seekers due to the scarcity of available housing. Our findings have broader relevance as the Austrian context is similar to other European countries that received many asylum seekers in 2015, such as Germany or Sweden.

Our first contribution is to address whether contact with asylum seekers increased when they were present locally. Contact is important if attitudes towards asylum seekers become more positive for those locals who have extensive interactions with them (Allport Reference Allport1954; Pettigrew Reference Pettigrew1998; Wagner et al. 2006). However, the scope conditions laid out by Allport are broad enough that they are unlikely to be met in many cases (Paluck et al. Reference Paluck, Green and Green2019). Here, we directly examine group exposure and contact after sudden changes in out‐group presence. Importantly, our test is based on the assignment of asylum seekers to a locality. This factor is external to respondents’ prior inclinations for contact, circumventing the endogeneity problem between contact and attitudes (Hainmueller & Hopkins Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2014). We find that citizens indeed take note of asylum seekers more frequently in municipalities where they were housed, but that interaction remained largely fleeting and passive. Thus, the local presence of asylum seekers does not necessarily imply greater contact with the natives.

Our second contribution is to examine the effects of local asylum seeker housing on citizen attitudes towards asylum seekers. As actual contact was low, we expect a negative effect of asylum seeker presence. Group conflict theory suggests that in‐groups develop hostility towards out‐groups seen as threatening (Blumer Reference Blumer1958; Blalock Reference Blalock1967). Importantly, perceived threats are larger when out‐groups are rapidly increasing in size (Meuleman et al. Reference Mousa2009), specifically in the case of immigrants (Hopkins Reference Hopkins2010; Newman & Velez Reference Newman and Velez2014). Individuals react by developing more negative attitudes towards the out‐group (e.g., Schlueter & Scheepers Reference Schlueter and Scheepers2010; Marx & Naumann Reference Marx and Naumann2018). Our results show that there was indeed, on average, a backlash in areas that provided housing for asylum seekers.

Our third contribution is to test whether these negative effects on attitudes towards asylum seekers spill over to related groups (Czymara & Schmidt‐Catran Reference Czymara and Schmidt‐Catran2017; Schaub et al. Reference Schaub, Gereke and Baldassarri2020). Under such so‐called secondary transfer effects, factors that change attitudes towards one out‐group also impact on attitudes towards other groups, for instance via attitude generalization (Pettigrew Reference Pettigrew2009; Schmid et al. Reference Schmid, Hewstone, Küpper, Zick and Wagner2012). Specifically, we find that attitudes towards immigrants more generally and particularly towards Muslims are negatively affected by asylum seeker presence.

Our final contribution is to show that asylum seeker presence increased the popularity of and vote intentions for the radical right (Vertier et al. 2020; Dinas et al. 2019; Steinmayr Reference Steinmayr2020), as also has been found for immigration more generally (e.g., Lubbers et al. Reference Lubbers, Gijsberts and Scheepers2002; Arzheimer Reference Arzheimer2009; Green et al. Reference Green, Sarrasin, Baur and Fasel2016; Halla et al. Reference Halla, Wagner and Zweimüller2017; Evans & Ivaldi Reference Evans and Ivaldi2020).

Methodologically, we use entropy balancing (Hainmueller Reference Hainmueller2012) on survey data from 2017 (Wagner et al. Reference Wagner, Aichholzer, Eberl, Meyer, Berk, Büttner, Boomgaarden, Kritzinger and Müller2018) linked to municipality‐level information to ensure comparability between citizens in our ‘treatment’ group – municipalities housing asylum seekers in early 2016 – and our ‘control’ group – municipalities without asylum seekers.

Our use of detailed survey data contrasts with existing research, which mostly draws on macro‐level changes in voting behaviour (e.g., Steinmayr Reference Steinmayr2020). Other influential survey‐based work (Hangartner et al. Reference Hangartner, Dinas, Marbach, Matakos and Xefteris2018) examines a context (Greek islands) with only minimal potential interaction between the host population and refugees. We place our findings in the context of other research on the effects of the migration crisis in the conclusion.

The migration crisis in Austria

Prior to the 2015 migration crisis, Austria already had moderately high levels of immigration and asylum seekers. The influx of asylum seekers in Austria in 2015 was nevertheless large compared to previous years and to other European countries. 88,098 people sought asylum in Austria in 2015, the third‐highest per capita rate in Europe that year. For months, the crisis dominated Austrian media coverage and political debates.

The asylum seekers were housed across Austria while their applications were considered. In about 40 per cent of cases, this process took more than six months.Footnote 2 The initial processing of asylum seekers was the responsibility of national authorities, with applicants housed in seven centrally run centres. Then, the responsibility for housing asylum seekers was handed over to provincial authorities. Housing was found through a bottom‐up process, with individuals, companies, NGOs, churches, or municipalities reporting available space (Haselbacher & Rosenberger Reference Haselbacher, Rosenberger, Rosenberger, Stern and Merhaut2018). The resulting accommodation could be a private home or (more often) a larger building, for instance, guesthouses (König & Rosenberger Reference König, Rosenberger and Rosenberger2010). As this process did not initially provide enough housing, a new law in October 2015 required each municipality to provide space amounting to 1.5 per cent of its population. This quickly increased housing availability, probably even in municipalities where the population or the local executive leadership were reluctant to take in asylum seekers. Austria and other Eastern European states closed the overland transit route between Greece and central Europe in early 2016, and the influx of asylum seekers to Austria then dropped substantially again.

Data

Data on the presence of asylum seekers in a municipality in early 2016 was provided by the Austrian Association of Municipalities.Footnote 3 The data comprises all asylum seekers whose final status decision is still pending in March 2016.Footnote 4

Our survey items are taken from a multi‐wave online survey conducted in 2017 (Wagner et al. Reference Wagner, Aichholzer, Eberl, Meyer, Berk, Büttner, Boomgaarden, Kritzinger and Müller2018). The survey was fielded by the online‐access panel MarketAgent (about 100,000 members). Respondents were selected based on key demographics (age, gender, genderXage, region, education, household size, district population). The survey is representative of the Austrian population on these variables.Footnote 5 We use questions from wave 1 (2–14 June, n = 4,020), wave 2 (27 July–10 August, n = 3,141) and wave 3 (30 August–14 September, n = 2,998). Our sample size in most models is about 2,400 respondents, of which 384 live in municipalities that did not house asylum seekers.Footnote 6

Research design

The crux for causally identifying the effect of local exposure to asylum seekers on population attitudes is whether local accommodation of asylum seekers correlates with pre‐existing population attitudes. If so, the association between asylum seeker presence and attitudinal differences could be merely confounding, an actual causal effect, or a mixture of both. Hence, as with most research on observational data, causal claims require careful attention to research design.

In our case, the number of asylum seekers arriving in Austria was so high that asylum seekers were located wherever placement demand matched reported suitable empty housing. Authorities aimed for a broad distribution of asylum seekers (König & Rosenberger Reference König, Rosenberger and Rosenberger2010). For instance, each province was required by law to accept asylum seekers proportional to its overall population. Therefore, we propose that there is an exogenous element in the placement mechanism, conditional on observable covariates.Footnote 7 This would indicate that already the mere association between asylum seeker presence and attitudes has some causal interpretation, but only if the availability of suitable housing is not correlated to pre‐existing population attitudes, and if there were no loopholes in the actual placement mechanism that introduced confounding.

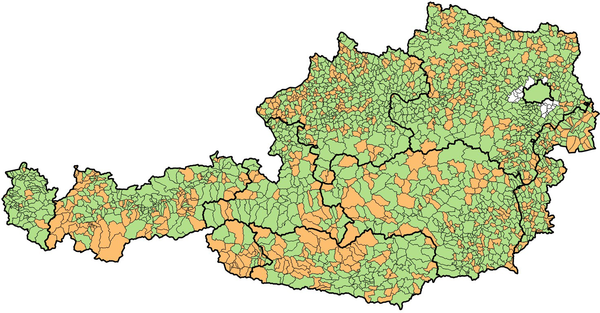

Such confounding may be present. In Appendix Section A.2 of the Supporting Information, we discuss the institutional context of placement and the potential for selection effects. In short, we cannot exclude that a correlation between placement and municipality characteristics exists. For example, Figure 1 shows that asylum seekers were present in many municipalities by 2016, but the share of municipalities with asylum seekers differs remarkably by state, hinting at non‐random elements in asylum seekers' dispersion. Also, Appendix Section A.3 of the Supporting Information shows that there are some pre‐treatment differences between respondents from municipalities that later did or did not house asylum seekers.

Figure 1. Asylum seeker presence in municipalities in Austria in 2016 (green: yes; orange: no; white: no data). [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Our setting hence is no different to most real‐world cases where we can expect the allocation of asylum seekers to be politically contested and thus not truly random. Accordingly, we follow the recent literature that tries to exploit the part of the variation in housing induced by the plausibly exogenous part of the placement mechanism (Dustmann et al. Reference Dustmann, Vasiljeva and Piil Damm2018; Hangartner et al. Reference Hangartner, Dinas, Marbach, Matakos and Xefteris2018; Steinmayr Reference Steinmayr2020). As pure experimental conditions never exist, all research on this topic has to state and justify the assumptions necessary for causal identification.

We assume that selection into treatment is a function of observable covariates (also known as the conditional independence assumption), and that we can reduce any selection bias by accounting for imbalance in pre‐treatment confounders between treated and control observations (Rudolph Reference Rudolph2018). Ideally, accounting for this imbalance is done non‐parametrically, via matching methods, to closely mimic a randomized experiment (Stuart Reference Stuart2010). We hence also rely on a binary indicator of asylum seeker presence (akin to an experimental stimulus). This is all the more sensible in our case because in the two‐step decision of whether and how many asylum seekers to house, the second step (how many) is likely more prone to endogeneity concerns than the first (whether or not); moreover, overlap for the balancing variables between treatment and control groups deteriorates quickly with fine‐grained continuous treatments.

So, we propose that if we match observations on socio‐demographic, political and economic factors at the municipality and individual level (step 1), achieving balance in the distribution of these covariates as if random, we can then approximate a causal estimation (step 2) of the effect of asylum seeker presence on the attitudes of Austrian citizens.

As our treatment takes place at the municipality level, we first draw on pre‐treatment aggregate‐level observables potentially linked to both asylum‐seeker placement and an average respondent's attitudes. 2013 turnout and Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ, Freedom Party) vote share, and their five year trends, capture the political dimension of selection. State, degree of rurality, 2015 municipality population, unemployment and their three year trends capture housing availability and economic situation (Hopkins Reference Hopkins2010). The state variable also captures whether the different schedules of state and municipality elections affected intake. 2015 immigrant share and its three year trend capture local migration exposure (Newman Reference Newman2013; Halla et al. Reference Halla, Wagner and Zweimüller2017). This should lead to a sample highly comparable in the ex‐ante probability of treatment. Secondly, we also include important individual‐level predictors of political attitudes (employment, education, gender, age, household size, religiosity, union membership, foreign birth, and self‐reported economic situation). By comparing respondents who are similar on these dimensions, we aim to address key aspects of remaining endogeneity. Appendix Table A.4.1 in the Supporting Information displays summary statistics for these variables.Footnote 8 Note that we reweight the sample to match respondents from municipalities that did not house asylum seekers.

We draw on entropy balancing (Hainmueller Reference Hainmueller2012) to implement the balancing of covariates between treatment and control group. We operationalize the treatment as a binary indicator of whether a municipality was (not) receiving asylum seekers by March 2016.Footnote 9 We reweight control‐group observations to match the distribution of first moments of our treatment group.

In Appendix Section A.5 of the Supporting Information, we show that our results are not overly sensitive to the inclusion or exclusion of one of the different dimensions of selection, that our results hold when drawing on nearest neighbour matching (with even fewer functional form assumptions) as an alternative approach, or when including survey sampling weights. In a placebo test with the (pre‐crisis) 2013 Austrian National Election Study (AUTNES) (Kritzinger et al. Reference Kritzinger, Zeglovits, Aichholzer, Glantschnigg, Glinitzer, Johann, Thomas and Wagner2017) (see Appendix Table A.3.2 in the Supporting Information) we find only small, if any, differences between our 2016 treatment and control group for a set of respondent attitudes comparable to several of our outcome measures. We conclude that our empirical strategy approximates the estimation of the average treatment effect on the treated (ATT) for asylum‐seeker placement.

Results

The results below use weighted linear regressions with standard errors clustered by municipality, controlling for the individual‐ and macro‐level variables employed in the balancing (to address as much remaining imbalance as possible).Footnote 10

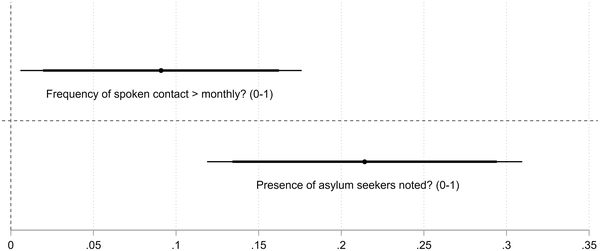

Figure 2 presents perceptions of asylum seeker presence and contact. Our first measure is self‐reported contact, where we asked respondents how often they had directly talked to asylum seekers (note that more objective measures were not available in our case). Our second measure is a statement of respondents that there were no asylum seekers in their municipality, when asked how well locals and asylum seekers live together. We find that respondents in municipalities that housed asylum seekers are more likely to state that asylum seekers were present. At 21 percentage points, this effect is substantial. This implies that our macro‐level treatment clearly affects respondent perceptions. As about 60 per cent of respondents note that asylum seekers were present, we also have a large degree of misperceptions and/or measurement error.

Figure 2. Perceived presence of and contact with asylum seekers.

Note: Coefficients from regressions of self‐reported presence perception (share of respondents noting presence of asylum seekers in their municipality) and contact with asylum seekers (self‐reported frequency of spoken contact with asylum seekers more than monthly) in 2017 on an indicator of 2016 asylum seeker housing in the respondent's municipality. Entropy balancing and control variables used as described in the research design section. 90 and 95 per cent confidence intervals shown. Full results: Appendix Table A.4.2. Question texts: Appendix Section A.1 of the Supporting Information.

But does the increasing presence of asylum seekers relate to actual inter‐group contact? The probability of reporting spoken interaction with asylum seekers at least several times per month is around 9 percentage points higher when asylum seekers were housed in the municipality. This is only around half the effect size of the presence effects. Levels of this variable in the control municipalities are low, with a mean of 28 per cent reporting at least this frequency of spoken interaction.Footnote 11

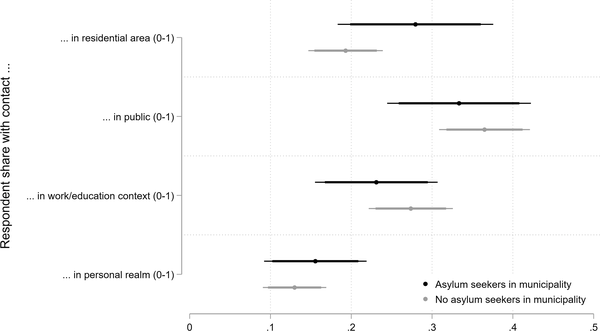

Figure 3 reports the context in which respondents report contact with asylum seekers. People in municipalities that housed asylum seekers were more likely to report contact in residential areas (8 percentage point increase from a 19 per cent baseline, significant at the 10 per cent level). Other types of contact were of similar size in both municipality types.

Figure 3. Which type of contact with asylum seekers changes?

Note: Comparison of average reported contact (group mean) by municipalities housing/not housing asylum seekers by May 2016. Entropy balancing used. 90 and 95 per cent confidence intervals shown. Regression estimates: Appendix Table A.4.3. Question texts: Appendix Section A.1 of the Supporting Information.

Overall, interpersonal contact was low everywhere and only slightly higher where asylum seekers were housed. However, respondents with asylum seeker housing were aware of local asylum seeker presence and reported increased contact in their local neighbourhoods. These results indicate that the conditions of group threat are better met than those of contact theory in our case.

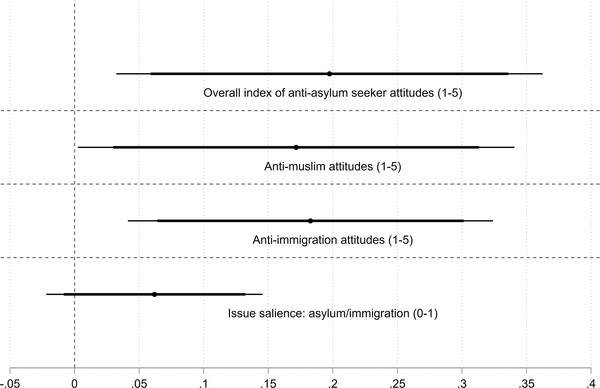

Next, we examine the effects of asylum seeker presence on attitudes. The first coefficient in Figure 4 shows that attitudes towards asylum seekers are more negative in municipalities with asylum seekers. An overall indicator of group threat constructed from four attitude questions shows a clear increase (0.2 units). Compared to the standard deviation of this index in the control group (0.96), the effect is substantial.Footnote 12

Figure 4. Attitudinal effects of asylum seeker housing

Note: Coefficients from regressions of 2017 self‐reported attitudes on an indicator of 2016 asylum seeker housing in a respondent's municipality. Entropy balancing used, control variables described in the research design section. 90 and 95% confidence intervals shown. Question texts: Appendix Section A.1. Full results: Appendix Tables A.4.4 to A.4.6 of the Supporting Information.

Importantly, these attitudinal changes go beyond asylum seekers. Composite indicators of anti‐Muslim and anti‐immigration attitudes are substantially higher in municipalities housing asylum seekers. Effects are of a similar magnitude as above (coefficients of 0.2 given a standard deviation of around 0.9 each). While the salience of asylum and immigration as a political topic is higher where asylum seekers are present, this effect is not quite statistically significant at conventional levels. The unambiguous overall picture is of greater hostility towards asylum seekers specifically and migrant out‐groups more generally.Footnote 13

Subgroup analyses (see Appendix Section A.6 of the Supporting Information) underline the plausibility of these findings. Reactions were more negative among male, older and less‐educated respondents. Municipalities with few foreigners prior to 2015 also see stronger average reactions. Municipalities where the FPÖ did better in the 2013 parliamentary elections have larger negative reactions, perhaps due to local mobilization effects by anti‐immigration politicians. Small subgroup sample sizes mean that these differences do not always reach statistical significance, but reactions are consistently more negative among the expected groups.

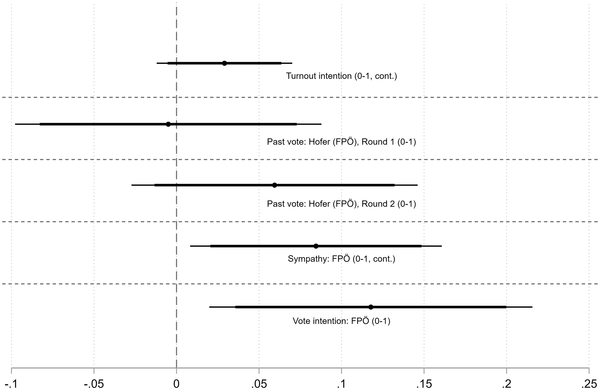

Finally, Figure 5 shows that there are also knock‐on effects on political preferences (Halla et al. Reference Halla, Wagner and Zweimüller2017). Self‐reported turnout intention is greater, though not to a statistically significant extent. While there is little effect on the recalled 2016 vote for the anti‐immigration presidential candidate Norbert Hofer in round one (April 2016) of the presidential elections, it is slightly though not significantly higher for round two (December 2016). However, current sympathy for the anti‐immigration FPÖ is higher, by 0.08 on a 0–1 scale; the currently intended parliamentary election vote for the FPÖ is also substantially larger, by over 10 percentage points. Hence, while there is no clear effect on the presidential election in 2016, it appears that local asylum seeker presence led to a larger probability of voting for the radical‐right FPÖ in 2017. Appendix Section A.8 of the Supporting Information presents indicative results that the radical right's campaign effort was greater where asylum seekers were housed, providing a potential mechanism for this effect.

Figure 5. Effects of housing asylum seekers on party preferences and voting behaviour.

Note: Coefficients of 2016 asylum seeker housing on 2017 vote recall and vote intention. Entropy balancing used, control variables as described in the research design section. 90 and 95 per cent confidence intervals shown. Full results: Appendix Table A.4.7. Question texts: Supporting Information Appendix Section A.1 of the Supporting Information.

Conclusion

The migration crisis of 2015 had wide‐ranging political consequences. Our study contributes detailed evidence on citizens' micro‐level reaction after direct exposure with asylum seekers. We find substantial and consistent negative effects of asylum seeker presence on attitudes towards asylum seekers, towards Muslims and immigrants, and on vote intention for the anti‐immigration Freedom Party. Exploratory analysis indicates that this pattern was stronger among male, older and less educated respondents, and in regions with lower prior exposure to immigration; that it got stronger over time; that backlash was stronger in municipalities with below‐median exposure, while contact increased more strongly in municipalities with above‐median asylum‐seeker influx; and that campaigning by the major radical right party was greater where asylum seekers were housed locally.

The extent of contact provides an explanation for this backlash. Residents noted the local presence of asylum seekers, so an attitudinal effect of asylum seeker presence is plausible. However, there was no clear increase in substantive contact, lessening the likelihood of a positive impact. These findings provide important micro‐level foundations for our macro‐level results. Our research is consistent with recent findings on low‐level, involuntary intergroup contact (Enos Reference Enos2014) and on local immigrant presence as a driver of negative out‐group attitudes and radical‐right voting (e.g. Arzheimer Reference Arzheimer2009; Halla et al. Reference Halla, Wagner and Zweimüller2017). Importantly, our findings do not provide evidence against potential effects of contact, whose study has recently received renewed attention (Paluck et al. Reference Paluck, Green and Green2019; Mousa Reference Mousa2020). Instead, the preconditions for such positive effects were likely not present for the general Austrian population.

A limitation of our study is that we report an average treatment effect on the treated and that the group of treated is not fully representative of the country's population. While respondents from treatment municipalities are fairly similar for many individual‐level characteristics, including education (see Appendix Table A.4.1 in the Supporting Information), they are generally from smaller, rural municipalities. Arguably, such municipalities (without large foreign populations) are key to understanding backlash against asylum seekers. For instance, the Freedom Party increased its vote share in 2017 by over 8 percentage points in rural areas but only 2 percentage points in large cities.Footnote 14 Nevertheless, we cannot provide insights into how respondents in urban areas with large migrant populations reacted to asylum seeker presence.

Our research adds to existing work on the migration crisis. We provide further weight to findings of increased hostility to the local housing of asylum seekers (Sekeris & Vasilakis Reference Sekeris and Vasilakis2016; Hangartner et al. Reference Hangartner, Dinas, Marbach, Matakos and Xefteris2018), though not all studies show these effects (Schaub et al. Reference Schaub, Gereke and Baldassarri2020). The migration crisis has been found to relate to citizen attitudes, for example concerning solidarity (Basile & Olmastroni Reference Basile and Olmastroni2020). Our results also bolster findings that housing asylum seekers had electoral benefits for the radical right (Dinas et al. 2019), especially in rural areas (Dustmann et al. Reference Dustmann, Vasiljeva and Piil Damm2018). Our findings go beyond these studies by using survey questions eliciting contact, by studying medium‐term effects in a key affected country, and by using survey measures of key outcomes. We note that one limitation of our study is the use of self‐reported contact in a cross‐sectional design; future work should endeavour to use objective measures of contact where possible and to draw on longitudinal data.

Our study also relates directly to Steinmayr (Reference Steinmayr2020), who studies the short‐term response of citizens to the migration crisis in Upper Austria. He reports that exposure to asylum seekers in municipalities where these were passing through (border municipalities) led to increased vote shares of the anti‐immigration Freedom Party, in line with our findings. In contrast, exposure to asylum seekers where these were housed led to reduced levels of support for the Freedom Party compared to municipalities without asylum seekers. He argues that this might be because encounters with refugees were more positive than initially expected and/or because local authorities fostered contact between refugees and natives (see also Vertier & Viskanic Reference Vertier, Viskanic and Gamalerio2020). These results contrast with our finding of more negative attitudes arising from exposure to asylum seekers. We cannot provide a causal explanation for this difference but highlight one potential mechanism: time of exposure. While Steinmayr (Reference Steinmayr2020) draws on data a few months into the 2015 crisis, we use data from 2017. Vote recall questions hint at potential changes in attitudes. In our case (see Figure 5), anti‐immigrant party/candidate support does not differ based on exposure in April 2016 but is mildly higher in December 2016 and substantially higher in mid‐2017. Future research could analyze why time of exposure might play a role here.

Finally, our findings have important consequences for tackling an influx of asylum seekers or other potential out‐groups. Future research should examine how local interventions, for example by local officials and civil society initiatives, may influence contact intensity and attitudinal reactions. Overall, we need to study what moderates negative reactions to out‐groups in order to best design asylum policies.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for comments from Eva Fernandez, Dominik Hangartner, Miriam Haselbacher, Judith Kohlenberger, Moritz Marbach, Liam McGrath, Guido Ropers, Susumu Shikano, Jeremias Stadlmair, Andreas Steinmayr, Rocío Titiunik and audiences at LMU Munich, ETH Zurich, University of Vienna, University of Konstanz and at the EPSA and DVPW annual conferences 2018 and the Dreiländertagung 2019. We would like to thank the Austrian National Bank and the Austrian Ministry for Science for funding the survey used in this paper. We also thank Daniel Kosak and the Österreichischer Gemeindebund for sharing data on asylum seekers in Austria. Jan Menzner provided valuable research assistance. Replication material to reproduce the figures and tables presented in this article is available in the Harvard Dataverse, at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/EWVXXL.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Supplementary material