The Weather Extremes in England's Little Ice Age database is part of a larger research project that investigates how early modern English people understood and related to the weather during the period of global cooling now known as the Little Ice Age. My preliminary research revealed that historical chronicles, including Raphael Holinshed's and John Stow's, could provide a wealth of information about extreme and unusual weather. Recognizing the time it would take to scour these tomes for weather records, and believing that this research could be of use to others, I sought and received funding to create an open access ArcGIS database that would map narrative weather records from England between 1500–1700. While these parameters reflect my own research field and provide a manageable focus, they also echo temporally what historians have identified as the height of the Little Ice Age.Footnote 1 What has become clear over the last five-and-a-half years of data collection is that the early modern English were at least as fascinated with the weather as we are today. The database quickly expanded beyond the chronicles to collect material from extreme weather pamphlets sensationalizing floods, snowstorms, lightning strikes, high winds, and earthquakes, as well as from personal diaries, including those of John Dee, John Evelyn, Ralph Josselin, Samuel Pepys, and Anthony Wood.

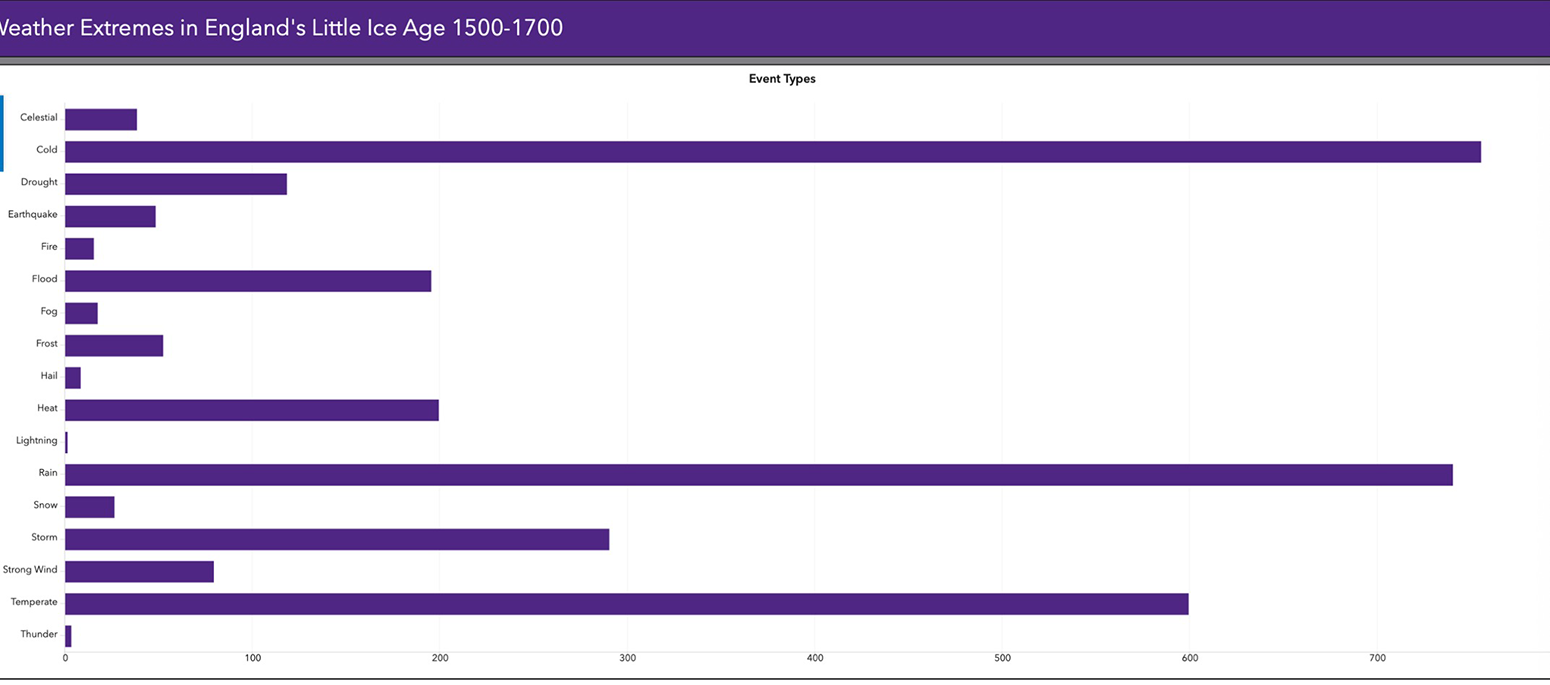

By collecting multiple records from multiple sources, we hope to offer a substantive database of English weather during this period of climate change. A significant overall finding, which complicates the Little Ice Age nomenclature supplied by glaciologist François Matthes in 1939 as a way of recognizing the period's glacial expansion, is that the experiences of global cooling and global warming are not dissimilar. While scientific proxy records such as ice core, tree ring, and pollen samples have been used primarily to identify the period's overall drop in temperature, narrative proxy records illuminate the full range of weather, including extreme heat, drought, rain, damaging storm systems, and changing seasonal patterns. The records we collect also include what we call “middling,” or temperate weather, which help to provide a fuller sense of how both weather and climate were changing. Including over three thousand notations, the mapping application allows users to narrow searches by event types, year, location, source, and effects (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Weather Extremes Mapping Application: https://weather-extremes-in-englands-little-ice-age-westernu.Hub.Arcgis.Com.

In the rest of this short article, I would like to focus on what is, at present, the sole manuscript source in the database: the “Commonplace book of the Shann family of Methley, co. York,” 1611–32 (Figure 2).Footnote 2 Compiled and written largely by Richard Shann (1561–1627), a Catholic copyholder, herbalist, and orchardist in Methley, West Yorkshire, this manuscript is a fascinating source that deserves more attention. Most of Shann's records are local or regional, with an occasional anecdotal report from elsewhere. But his weather notations reflect a steady increase in extreme weather events in the seventeenth century, which correspond with the national trend. They also show us that cold weather is not the only story of the Little Ice Age, as Shann experienced a series of extreme weather events similar to those endured globally today (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Records from the “Commonplace book of the Shann family,” BL Add. MS 38599, (BL).

Figure 3. Event types collected from Richard Shann's Commonplace book.

Shann's large folio volume incorporates far more than weather events, including a survey of the Manor of Methley; court records; extracts from Camden's Britannia; an account of a parish play called Canimore and Lionley; a collection of hymns and songs; a detailed description of a local Rogation Day procession; and a list of herbs in Shann's garden.Footnote 3 Of most interest here are his records of local events, dated 1617–32 (fols. 49r–56r), and another section titled “Of Certain Extraordanarie/thinges chauncinge in my tyme/and remembrance,” dated 1586–1622 (fols. 66r–78v) (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Richard Shann, “Of Certain Extraordanarie thinges,” BL Add. MS 38599, fol. 66r, (BL). Photograph taken by author.

While some of these records recount wondrous events, such as a battle of starlings over the city of Cork in 1621, and others are of a more personal nature—cataloguing the planting of trees or his children's illnesses, for example—many of them have to do with the weather. Shann makes a total of fifty-five entries on this topic, with only nine between 1586–99, and forty-one between 1600–22. Although he observes temperate conditions, he reports principally on extremes: storms, drought, unusual heat, abnormally heavy or long-lasting rain, floods, frosts and freezes, and high wind.

I would like to provide two brief examples from Shann's notations that illuminate a discernible shift in weather patterns between the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. In the first instance, in 1591–92, Shann records not a cold snap, but a period of extended drought and mild weather.Footnote 4 This begins in the summer of 1591, when he observes that the flow of the Aire and Calder rivers, which ring the village of Methley, had so much diminished that “a man went over the forde drie shodd.” These conditions extended into the following winter, which, as Shann remarks, remained dry and remarkably mild: “A fayre winter … there was not seene anie snowe vntill/march.” This weather persisted even into the first half of 1592; Shann records an unusually “fayre & kyndlie springe … that men of fourescore yeares did/saie that they never had seene” (fol. 66v). Shann's experiences correspond with additional records in the database, including J.M. Stratton's Agricultural Records in Britain, which observes more broadly “A year of drought.”Footnote 5

In contrast to the sustained weather pattern that settled over England in 1591–92, 1615 delivered a succession of climatic swings. The year began with a great frost, which lasted between 20 January and 5 February and was followed by a devastating snowstorm whose effects lingered until mid-March.Footnote 6 Shann recalls “such monstrous driftes the like not seene before/of anie then livinge.” He adds that the snow “covered manie howses quit over, and the people/that dwelt in them could not get out but that theyr/nieghbours digged through the Snowe to let them out” (fols. 72r–v). A March thaw led to a “verie great floud,” but the snow returned at the end of April (“A foote thicke”) and in early May (“it did both Snowe & haill”). Even on 15 May, Shann reports that “I did se wyth my owne eyes of this Snowe vn/melted … lieinge vpon the west/tern hills” (fol. 73r). The late spring and summertime, however, provided a direct yet equally unwelcome contrast to the exceeding winter cold, with the end of May being “verie Sunshyne & excedinge hote” and the summer “verie drie and burninge hote Sonshine/… wherof the pastures/was excedinge Shorte & burned vp, so that Cattel/was in A manner pined to death,” and grain of all kinds, alongside beans and peas, did not grow (fols. 73r–v).

These 1615 records, with their accounts of climatic fluctuations, feel all too familiar to us in our age of global warming. Shann's records thus retrospectively allude to climatic changes as well as record specific weather events; they also corroborate and are corroborated by other contemporary sources. Alongside the many other records that continue to be collected for the Weather Extremes database, Shann's manuscript helps to provide not only a picture of the variety of extreme weather experienced in England's Little Ice Age, but also a reflection of the extreme weather patterns experienced today.

Funding statement

Funding for the database was provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, with further support from the Faculty of Arts and Humanities and the Weldon Library at Western University.

Madeline Bassnett is Professor of English and Writing Studies at Western University. She is most recently the editor of a special issue on climate change and the Little Ice Age for Early Modern Studies Journal (vol. 10, 2025). Her forthcoming monograph, Climate Change Cookery: Recipes and Resilience in England's Little Ice Age, 1550–1700, will be published by Concordia University Press in 2026.

The database is a team project, and I am honored to be working alongside Weldon Library's ArcGIS Specialist, Liz Sutherland, who conceptualized and maintains the mapping application; Research Assistants Daryl Wakunick and Matthew Rooney, who have read through thousands of pages searching for weather records; and my colleague at the University of Southern Queensland, Laurie Johnson, who generously contributed many of his own findings to the database. Thank you as well to Zack MacDonald, Map Librarian, for the map overlays and to Kristi Thompson, Research Data Librarian, for seeing the potential of this project. Please address any correspondence to m.bassnett@uwo.ca.