1. Introduction

Anti-elitist partiesFootnote 1 have become a key feature of European parliamentary politics. Relatively limited attention has been spent on how these parties operate in parliament, in particular when they are in opposition. This lacuna is even more striking when we realize that they spend most of their existence in opposition (De Lange and Böckmann, Reference De Lange and Böckmann2025). Moreover, the existing evidence on how anti-elitist parties vote in parliament is contradictory: on the one hand, Otjes and Louwerse (Reference Otjes and Louwerse2015) have argued that there is no major overlap in the voting patterns of anti-elitist parties as their left- or right-wing ideology is more important in guiding their behavior than their shared anti-elitism. On the other hand, the exact same pair of authors argue that populist parties are more likely to vote against government bills in parliament (Louwerse and Otjes, Reference Louwerse and Otjes2019). The key underlying notion here is that anti-elitist parties are more likely to use parliament as a bully pulpit to express their dissatisfaction with the government instead of as a marketplace to build majorities to influence policy (Otjes and Louwerse, Reference Otjes and Louwerse2021). Anti-elitist parties swim against the stream in many parliaments by voting against legislation, unlike many other parties (De Giorgi and Ilonszki, Reference De Giorgi and Ilonszki2018).

Specifically, Otjes and Louwerse (Reference Otjes and Louwerse2021) argue that anti-elitist opposition parties are more likely to vote against legislation than other opposition parties to show that they are not just opposed to the sitting government and their policies, but also the mainstream political elite and their way of doing politics. In contrast, other opposition parties will show their constructive attitude, their willingness to compromise and cooperate with other parties by voting for legislation. In this article, our goal is to find out to what extent and under what conditions anti-elitist parties vote the same (and differently from other parties).

The lack of consistent findings in this field is the result of a methodological problem. So far, there is no method of analyzing parliamentary voting behavior that does the following three things at the same time: first, test hypotheses (as opposed to an explorative method); secondly, evaluate different possible explanations at the same time (e.g., robustly control for alternative explanations); thirdly, compare patterns for different types of votes. That is: we lack a method that allows one to incorporate multiple party- and vote-level variables. Yet, the simple reality is that parties voting in parliament vote on different issues. Parties with particular characteristics are likely to vote differently on some documents (e.g., bills) than other parties or than they would on other documents (e.g., motions). For instance, anti-elitist parties are likely to vote differently on legislation than on other votes. The most important methods used in the field are dimension-reduction methods like NOMINATE (Poole and Rosenthal, Reference Poole and Rosenthal2011): they produce a map of which parties tend to vote the same often and which do not. From this, one can infer which are the one or two most important lines of conflict. Such a method cannot be used to test how important specific lines of conflict are. Bräuninger et al. (Reference Bräuninger, Müller and Stecker2016) and Clinton et al. (Reference Clinton, Jackman and Rivers2004) offer innovations that allow one to incorporate vote characteristics. These are still methods that deliver a map of party positions instead of a statistical model that allows one to evaluate the importance of different lines of conflict. The alternatives are focused approaches such as Louwerse’s phi (Van Aelst and Louwerse, Reference Van Aelst and Louwerse2014) or measures of Congressional polarization (Theriault, Reference Theriault2008): they allow one to test the importance of a specific line of conflict, but do not allow for the inclusion of control variables. Building on the work of Van der Veer (Reference Van der Veer2018), we introduce the proposal-specific dyadic method. We build on his dyadic method that allowed one to test the relative importance of different party-characteristics for voting behavior but did not allow for the inclusion of vote-specific characteristics. This proposal-specific dyadic method offers a crucial innovation in the study of parliamentary voting because it allows for testing the importance of both proposal and party characteristics for a large number of votes. This method looks at to what extent parties vote the same on specific votes. Specifically, it looks at to what extent pairs of parties vote the same on each individual vote (e.g., whether the Liberal and the Freedom Party vote the same on the education budget). This method also informs how we formulate our hypotheses: they specify conditions under which parties are more or less likely to vote the same. Because our method allows us to take into account many characteristics of votes and parties, we do not just focus on anti-elitism but also examine patterns of coalition–opposition voting and ideological considerations.

This article studies voting in the Dutch parliament. As we will detail below, the Netherlands has a number of characteristics that make it relatively attractive to study party-level voting patterns (high levels of party unity, unrestricted floor access).

2. Anti-elitism and parliamentary voting

Previous research suggests that a substantial share of government bills is supported by parliamentary opposition parties all over Europe (De Giorgi and Ilonszki, Reference De Giorgi and Ilonszki2018), including in the United Kingdom House of Commons (Rose, Reference Rose1984), the Spanish Congress of Deputies (Mújica and Sánchez-Cuenca, Reference Mújica and Sánchez-Cuenca2006), the Swedish Riksdag (Loxbo and Sjölin, Reference Loxbo and Sjölin2017), the Italian Chamber of Deputies (Giuliani, Reference Giuliani2008), and the Dutch Second Chamber (Visscher, Reference Visscher1994). Parties vote in favor of legislation to signal their constructive attitude toward the other parties, voters, and interest groups (Rose, Reference Rose1984; Mújica and Sánchez-Cuenca, Reference Mújica and Sánchez-Cuenca2006). In multiparty systems, in particular opposition parties may have an interest in fostering warm relations with the coalition because they may govern with them in the future. They might have governed with the parties currently in the coalition, perhaps even working to prepare the very bill they are voting for now while in opposition (Andeweg, Reference Andeweg, Müller and Narud2013). Yet, even in the House of Commons with two effective parties, Rose (Reference Rose1984) found that opposition parties tended to vote in favor of most legislation, which he relates to the “consensus model”: legislation is often the result of lengthy negotiations between government and interest groups. Voting against that legislation may upset the interest groups that helped shape it (Kerr, Reference Kerr1978; Rose, Reference Rose1984). Moreover, opposition parties may have proposed improvements for the bill themselves, which the government has adopted (Van Mechelen and Rose, Reference Van Mechelen and Rose1986; Andeweg, Reference Andeweg, Müller and Narud2013; Loxbo and Sjölin, Reference Loxbo and Sjölin2017).

Our study focuses on how anti-elitist parties vote on legislation. In order to understand the term anti-elitism, we need to briefly discuss its more well-known sibling, populism.Footnote 2 Mudde (Reference Mudde2007) understands populism as centering on four key claims: the first is that government actions should derive from the will of the people; the second is that the people are inherently virtuous and homogeneous; the third is that the current elite is corrupt and acts as one to undermine the people’s right to govern; and the fourth is that populist leaders will restore this power to the people. Populism distinguishes between an elite it opposes and a people it claims to represent. Both elements—anti-elitism and popular sovereignty—are essential for a party to be considered populist. Yet, one can be anti-elitist without supporting more direct influence for the people: a party representing an ethnic minority can be very critical of the current government for pursuing what it considers racist policies but does not necessarily believe that the populace is homogeneous or support uncontrolled popular sovereignty. Anti-elitism and pro-people attitudes are conceptually and empirically distinct (Meijers and Zaslove, Reference Meijers and Zaslove2021). Many authors see anti-elitism as a scale with parties differing in usage of anti-elitist rhetoric (Polk et al., Reference Polk, Rovny, Bakker, Edwards, Hooghe, Jolly, Koedam, Kostelka, Marks, Schumacher, Vachudova and Zilovic2017; Meijers and Zaslove, Reference Meijers and Zaslove2021).

Louwerse and Otjes (Reference Louwerse and Otjes2019, Reference Otjes and Louwerse2021) propose that it is populists’ anti-elitism that fuels how they behave as opposition parties. It is that element of populism, which sets them against the ruling elites, including the sitting government. Opposition parties that score high on anti-elitism use parliament as a bully pulpit to express popular dissatisfaction with the government, its policies, and mainstream politics more generally. These opposition parties will use their parliamentary tools to voice dissent. Voting against legislation may be an important signaling tool (Tuttnauer, Reference Tuttnauer2018): anti-elitist parties can use their vote to mark clearly that they are opposed to the government and its policies, but by bucking the existing consensus, they also signal that they are opposed to the mainstream elite (whether in the coalition or the opposition) and their way of doing politics. The weak relationship between anti-elitist parties and interest groups (Berkhout et al., Reference Berkhout, Hanegraaff and Statsch2021) may also make them less likely to support corporatist bargains. Parties that score lower on anti-elitism approach parliament as a marketplace where they work together constructively with other parties to influence policy. They seek to deliver for their constituents even from the opposition benches. This leads us to the following hypothesis:

Anti-elitism: the more similar parties are in their level of anti-elitism, the more likely they are to vote the same on legislation.

3. Alternative explanations

When examining parliamentary voting, it is crucial to take into account alternative explanations of voting patterns, in particular where it comes to anti-elitist parties, which often are also quite particular in other respects. For instance, anti-elitist parties are often opposition parties. It might be that the pattern we see for anti-elitist parties is due to them being in opposition. This is particularly relevant because Louwerse and Otjes (Reference Louwerse and Otjes2019) look specifically at opposition parties. Anti-elitist parties also tend to have extreme ideological positions; it might be that the pattern that we see for anti-elitist parties is due to them being extremist. Therefore, we will account for coalition participation and ideological positioning in our analyses. Our proposal-specific dyad method allows for a more advanced analysis of these factors than the existing literature.

3.1. Coalition–opposition division

One of the most well-established findings in legislative behavior is that coalition and opposition parties differ strongly in how they behave in parliament (Andeweg et al. Reference Andeweg, De Winter and Müller2008; Landi and Pelizzo, Reference Landi and Pelizzo2013; Bräuninger et al., Reference Bräuninger, Müller and Stecker2016; Hix and Noury, Reference Hix and Noury2016; Louwerse et al., Reference Louwerse, Otjes, Willumsen and Öhberg2017; Tuttnauer, Reference Tuttnauer2018). Parliament in many ways is an arena for the fight between coalition and opposition parties. As Laver (Reference Laver, Weingast and Wittman2006, p. 137) describes, “since members of [majority coalition] cabinets are bound together by constitutional rules of collective cabinet responsibility, it is likely that all parties in the executive coalitions will vote in the same way, despite having different policy positions.” Dewan and Spirling (Reference Dewan and Spirling2011) and Bräuninger et al. (Reference Bräuninger, Müller and Stecker2016) suggest that opposition parties have an interest in operating cohesively. As the British Whig politician George Tierney is supposed to have said, “the duty of an Opposition [is] very simple […] to oppose everything, and propose nothing” (cited by Lord Stanley in Hoyt and Roberts, Reference Hoyt and Roberts1922).

Yet, the actual voting patterns appear to be more complex. Under different conditions, the coalition–opposition division matters more or less: coalition parties have strong expectations about the behavior of their partners (Otjes and Louwerse, Reference Otjes and Louwerse2024). They continually coordinate with each other in coalition meetings (Timmermans and Andeweg, Reference Timmermans, Andeweg, Müller and Strom2000). When a new issue comes up, coalition parties first check whether something has been arranged in the coalition agreement. Coalition parties will not accept their coalition partners sponsoring or voting for something that goes in against the agreement (Holzhacker, Reference Holzhacker2002). If an issue is not included in the agreement, coalition parties first look at possibilities within the coalition. If a party’s plans run into a veto within the coalition, they will not pursue it, because that may risk a cabinet crisis. When an issue risks the stability of the coalition, the coalition parties are likely to form a united bloc, independent of their policy differences (Huber, Reference Huber1996; Diermeier and Feddersen, Reference Diermeier and Feddersen1998). Only when a proposal is outside of the coalition agreement and not vetoed by other parties, can a coalition party examine a proposal freely. Of course, sometimes coalition parties purposefully deviate from the compromises in the coalition agreement and risk a breakdown of the coalition. In contrast, opposition parties do not operate in such a coordinated fashion. An opposition party is not constrained by considerations of coalition stability when making proposals. They use their parliamentary tools to destabilize the coalition in order to provoke new elections (Tuttnauer, Reference Tuttnauer2018). They have an interest in sponsoring proposals that drive a wedge between coalition parties (Van de Wardt et al., Reference Van de Wardt, De Vries and Hobolt2014). Their proposals are likely to go against the coalition agreement or run into vetoes from coalition parties and therefore are likely to be rejected by the coalition en-bloc (Bräuninger et al., Reference Bräuninger, Müller and Stecker2016).

The proposals sponsored by coalition parties or opposition parties are thus likely to elicit different reactions from coalition and opposition parties. Opposition parties are likely to undermine coalition stability; therefore, proposals made exclusively by opposition parties are more likely to elicit a unified, negative response from the coalition parties. Such tactical considerations are absent for proposals made by coalition parties (pace Bräuninger et al., Reference Bräuninger, Müller and Stecker2016). All in all, we expect that:

Coalition–opposition hypothesis: Coalition parties are more likely to vote the same on proposals made by opposition parties than on other proposals.

3.2. Ideological considerations

In addition to the division between coalition and opposition parties, programmatic differences play a key role in parliamentary votes (Hix and Noury, Reference Hix and Noury2016; Louwerse et al., Reference Louwerse, Otjes, Willumsen and Öhberg2017). Left-wing parties are likely to vote in the same way and differently from right-wing parties. The division between left and right in parliamentary voting is found in the US Congress (Crespin and Rohde, Reference Crespin and Rohde2010; Poole and Rosenthal, Reference Poole and Rosenthal2011; Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Smith and Haptonstahl2016), the Swedish Riksdag (Clausen and Holmberg, Reference Clausen, Holmberg and Aydelotte1977), and the South Korean National Assembly (Hix and Jun, Reference Hix and Jun2009). Studies on the European Parliament, a parliament where the coalition–opposition division is weaker than in national parliaments, suggests than on specific issues, specific dimensions matter. Here, the economic dimension matters on votes on economic issues (Lindberg, Reference Lindberg2008, but see Otjes and Van der Veer, Reference Otjes and Van der Veer2016), the environmental dimension matters on environmental and trade issues (Tsebelis and Kalandrakis, Reference Tsebelis and Kalandrakis1999; Otjes et al., Reference Otjes, Van der Veer and Wagner2023), the division between interventionist and pacifist parties matters on foreign policy votes (Otjes et al., Reference Otjes, Van der Veer and Wagner2022), etc. (see also Kreppel, Reference Kreppel1999; Kreppel and Tsebelis, Reference Kreppel and Tsebelis1999). The notion that policy positions related to the issue of the proposal are associated with voting patterns has been observed for some national legislatures as well (Clausen and Holmberg, Reference Clausen, Holmberg and Aydelotte1977; Crespin and Rohde, Reference Crespin and Rohde2010).

In this paper, we focus on four policy areas that encompass a large share of votes: the economic dimension relating to economic votes, the environmental dimension on environmental votes, the cultural dimension on votes that touch on cultural issues, such as migration and safety, and the European integration dimension for votes on European affairs. The first two form the bulk of voting in parliaments. We add the third and fourth because anti-elitist parties tend to be Eurosceptic (Otjes and Louwerse, Reference Otjes and Louwerse2015; Call and Jolly, Reference Call and Jolly2020) and are more conservative on cultural issues. These cultural issues include migration and civic integration but also the position of Islam in society and national identity as well as crime and privacy (Otjes, Reference Otjes and Lisi2018).

Economic Hypothesis: The closer parties are on the economic dimension, the more likely that they vote the same on economic issues.

Cultural Hypothesis: The closer parties are on the cultural dimension, the more likely that they vote the same on cultural issues.

Environmental Hypothesis: The closer parties are on the environmental dimension, the more likely that they vote the same on environmental issues.

EU Hypothesis: The closer parties are on the EU integration dimension, the more likely that they vote the same on EU-related issues.

4. Country selection and description

We study how anti-elitist parties vote in parliament. We focus on the Netherlands for three reasons: agenda control, strength of party unity, and the presence of both left- and right-wing anti-elitist parties. As we show in Table A1 in the Online Appendix, there is no country in Europe that scores as high on all these criteria as the Netherlands. Control of the agenda is a central criterion in the view of Hix and Noury (Reference Hix and Noury2016): If the government sets the agenda, the issues that are voted upon are likely to be less diverse and the opposition parties will behave in a more cohesive way than when agenda control is not monopolized. Given that we are interested in how the diversity of proposals affects voting behavior, we want a system that can offer us the greatest mix of proposals and the lowest possible level of government agenda control. As we detail in Table A1 in the Online Appendix, the Netherlands has the least centralized control over the agenda in Europe. The coalition–opposition division is likely to be weaker here than elsewhere.

Party unity is a practical criterion. As we seek to analyze party characteristics, we want to apply our method to parties and not to individual members of parliament (as Van der Veer, Reference Van der Veer2018 did). Therefore, we want party unity to be as high as possible: as Table A1 in the Online Appendix details, the Netherlands has almost perfect levels of voting unity. This high level of party unity allows us to account for all parliamentary votes and not just roll calls. Including all votes solves the bias in sampling that is inherent to analyzing roll call votes (Høyland, Reference Høyland2010).

Finally, we want to study where we can look at anti-elitism separate from party ideology. That means we would want to have a system where we have both left- and right-wing anti-elitist parties, as is the case in the Netherlands (as we detail in Table A1 in the Online Appendix).

The Dutch parliamentary system has a number of characteristics that are relevant for our discussion. The Netherlands has a bicameral system, but our focus is on the lower house. The upper house, composed of partisan senators, cannot amend legislation, focuses on legislative review, and tables motions far less often than the lower house. We examine the parties that are in parliament at the start of each parliamentary term, because there are no data on the ideology of splits that form during the term. Our analysis looks at 15 different parties. Table A2 in the Online Appendix details the diversity of their ideological positions and stints in the coalition. In this paper, we focus on the period 1998–2021 due to reasons of data availability.

5. Methods

This paper studies parliamentary voting in the Netherlands between 1998 and 2021 using data from the Dutch Parliamentary Voting Database (DPVD). We use vote characteristics from the DPVD and party positions from the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES) and from textual analysis.

Different methodologies could be applied to studying parliamentary voting behavior. We identify three methodsFootnote 3: the dimension-reduction approach, the focused approach, and the dyadic approach. We detail the advantages and disadvantages of these methods below.

5.1. Dimension-reduction approaches

Dimension-reduction approaches, such as NOMINATE (Poole and Rosenthal, Reference Poole and Rosenthal2011), are commonly used. These methods reduce a large number of votes to a “map” of the political space with one or two dimensions. These methods take all votes and identify which are the main lines or main lines of conflict (Van der Veer, Reference Van der Veer2018). This aggregate view makes these methods a good theory-generating approach, but not a good theory-testing one (Van der Veer, Reference Van der Veer2018). They are well fitted to answer explorative research questions like “what are the main lines of conflict in legislature x?” If the goal is to determine to what extent a particular line of conflict plays a role in legislative voting, these methods are less apt (Van der Veer and Otjes, Reference Van der Veer and Otjes2021): the algorithms prioritize the dominant patterns and treat smaller patterns as error (Voeten, Reference Voeten and Thomassen2009). If the map is multidimensional, one can only provide “suggestive evidence” (Hix and Noury, Reference Hix and Noury2016) about the importance of ideological dimensions or other divisions for voting. One can potentially look at different maps of different kinds of votes side by side to determine whether the dominant line of conflict for one kind of vote is also the dominant line of conflict for another kind of vote, but one cannot directly compare the distances from different maps. This is because they are scaled independently (Hix and Noury, Reference Hix and Noury2016). All in all, if the goal is to test to what extent a particular dimension matters in parliamentary voting, these data-reduction methods are not ideal, in particular not if one seeks to determine under what conditions particular dimensions matter more or less, if this is not one of the main lines of conflict, and if one wants to robustly control for alternative explanations.

While NOMINATE is the dominant dimension-reduction approach in the field, it is not the only one. Two notable alternatives are offered by Clinton et al. (Reference Clinton, Jackman and Rivers2004) and Bräuninger et al. (Reference Bräuninger, Müller and Stecker2016). While Clinton et al. (Reference Clinton, Jackman and Rivers2004)’s method could potentially be used to include features of legislation, the goal of this method is still to estimate ideal points of legislators: the goal is to map where individual legislators stand if their positions are not known. This can, for instance, help answer the question whether Elizabeth Warren has a more liberal voting record than Bernie Sanders. Bräuninger et al. (Reference Bräuninger, Müller and Stecker2016) likewise offer a method for ideal-point estimation where they can remove some patterns (e.g., coalition/opposition division or the effect of being an anti-system party) to ensure that the map they show reflects party’s ideal points and not their strategic considerations. One can remove specific patterns from the spatial maps by hardcoding them into the spatial mapping algorithm. Both approaches do not apply to our current study, as we detail below there are reliable estimates of party positions. Our goal is to evaluate precisely under what conditions which lines of conflict become more or less important. That is: our goal is not to map the previously unknown positions of legislators but to see under what conditions which set of known positions of parties is most predictive of their behavior.

5.2. Focused approaches

The focused approaches examine the importance of one particular division for voting behavior. Probably the most common focused approach is Louwerse’s phi, which is used to examine the importance of the opposition–coalition divide (Van Aelst and Louwerse, Reference Van Aelst and Louwerse2014; Louwerse et al., Reference Louwerse, Otjes, Willumsen and Öhberg2017; Tuttnauer, Reference Tuttnauer2020; Vos et al., Reference Vos, Otjes, van Kalken and Boogaard2024). One can use this to examine under what conditions the division between coalition and opposition is stronger or weaker. A number of studies take a similar approach: Mújica and Sánchez-Cuenca (Reference Mújica and Sánchez-Cuenca2006) look at whether in specific votes opposition parties supported the coalition parties; Tuttnauer (Reference Tuttnauer2018), Hohendorf et al. (Reference Hohendorf, Saalfeld and Sieberer2021), and Benedetto and Hix (Reference Benedetto and Hix2007) examine whether in specific votes, specific opposition parties or MPs vote the same as the coalition parties. The biggest drawback of these methods is that it is difficult to differentiate between patterns that are highly correlated: consider a situation where all the left-wing parties are in the coalition and all the right-wing parties are in the opposition. If all votes divide the coalition parties from the opposition parties, is that because of coalition discipline or because these are motivated by substantial considerations (Louwerse et al., Reference Louwerse, Otjes, Willumsen and Öhberg2017)?

Another approach that focuses on one outcome is the research that looks into the level of party polarization in the U.S. Congress (Lee, Reference Lee2008; Theriault, Reference Theriault2008): this measure reflects how predictive partisanship is for how individual Congresspeople vote. In turn one can use this to assess how vote characteristics affect partisan polarization, e.g., to show that partisan polarization is stronger for procedural votes (Theriault, Reference Theriault2008) or votes on economic issues (Lee, Reference Lee2008) but one cannot include alternative explanations for the same voting behavior (e.g., whether the urban–rural divide is not a better explanation of the same outcome). All in all, the focused approaches allow one to test to what extent a particular pattern is present but they do not allow one to control robustly for alternative explanations.

5.3. Proposal-specific dyadic method

The proposal-specific dyadic method allows one to compare the importance of different potential explanations while examining different conditions under which they matter. We build on the dyadic approach developed by Van der Veer (Reference Van der Veer2018). This approach examines parliamentary behavior as a relational characteristic. In other words, rather than studying whether a party votes in favor of or against a proposal, the dyadic approach examines pairs of parties and the extent to which they vote similarly. Combining this with party characteristics allows one to assess the degree to which these differences are reflected in voting and to assess the relative importance of these factors while controlling for alternative explanations. The dyadic method aggregates all votes in one parliamentary term together to get a ratio variable representing to what extent a pair of parties votes together. That is: this method does not allow us to take vote characteristics into account. We follow the lead of earlier studies that take into account vote characteristics (e.g., Kerr, Reference Kerr1978). We do so by looking at whether each pair of parties votes the same on a specific vote and pool all these distances together into one data set, allowing us to take into account differences between the two parties as well as vote characteristics.

Compared to the dimension-reduction approaches, the proposal-specific dyadic method allows us to rigorously assess the importance of different potential explanations and to directly compare voting under specific conditions. Compared to the focused approach, it also allows us to control for alternative explanations. Like any method, the proposal-specific dyadic method does have drawbacks. The most important drawback is that one can only evaluate how differences between parties affect differences in voting behavior instead of looking at how parties’ characteristics affect vote choices. On the basis of our analysis, one cannot say whether anti-elitist parties vote against legislation, only whether anti-elitist and other parties vote differently on legislation. The wording of our hypotheses reflects this.

5.4. Dependent variable

The proposal-specific dyadic approach works in the following way. The first step is that all possible pairs of parties are created. We identify for each vote whether parties vote the same (yea-yea, nay-nay). If a party was not present for a vote, it gets a missing value.Footnote 4 We gathered these data from the DPVD (Louwerse et al., Reference Louwerse, Otjes and Van Vonno2018) for the period 1998–2021. The number of cases for every vote is nearly equal to half the square of the number of parliamentary parties at the time of vote. The voting similarity score is a binary variable. Table A3 in the Online Appendix shows the descriptives of our variables.

5.5. Proposal-level variables

We include six sets of independent variables. Three of these are at the proposal level: first, to test the Anti-elitism Hypothesis, we need information about whether a vote concerns a bill or not. This is also listed in the DPVD. One category is bills (including treaties and budgets).Footnote 5 The remaining votes are amendments, motions, and a minute segment of other, mainly procedural votes.

Secondly, to test the Coalition–Opposition Hypothesis, we check who sponsored the vote. For each vote, this is listed in the DPVD. We identify proposals with only coalition sponsors, proposals with only opposition sponsors, and mixed proposals. For the purpose of this paper, we define “coalition parties” as those parties who have members in the cabinet and “opposition parties” as those who do not. This is more complex when we consider the possibility of support parties of minority governments, in particular the radical right-wing populist Freedom Party (Party voor de Vrijheid, PVV) in 2010–2012. In the main text, we treat the PVV as an opposition party in this period, but in the Online Appendix, we treat it as a coalition party.Footnote 6

Thirdly, we look at the four ideological hypotheses (Economic Hypothesis, Cultural Hypothesis, Environmental Hypothesis, and EU Hypothesis). The office of the clerk of parliament has included subjects for every vote. Every vote gets at least one subject, but there can be more than one subject per vote. We classify these into economic, environmental, cultural, and European. Table 1 shows how large these categories are and gives examples of the subcategories included. Table A4 in the Online Appendix gives a complete overview. In analyses in the Online Appendix, we divide this further into a larger number of categories: we split the economic category up into public sector issues (where the issue is the size of the government) and private sector issues (where the issue is the level of regulation). We add issues related to democracy, the relationship between the central and subnational governments, morality, and defense. Table A6 in the Online Appendix shows the correlations between the vote characteristics.

Table 1. Vote categories and CHES

5.6. Party-level variables

We include three sets of variables at the party-level: First, to test the Anti-elitism Hypothesis, we need information about anti-elitism. Anti-elitism is not consistently available in the CHES for the entire period. Therefore, we use the dictionary of Pauwels (Reference Pauwels2011), who developed a list of words to measure the populist character of a party, which almost exclusively concerned anti-elitism (listed in Table A5 in the Online Appendix). This approach has been validated by comparing it to more precise hand coding in Rooduijn and Pauwels (Reference Rooduijn and Pauwels2011). The party scores correlate strongly with the measure of anti-elitism in the CHES for the available waves.Footnote 7 We apply this dictionary to the election manifestos of the parties for every election between 1998 and 2017.Footnote 8 We show scatter plots between anti-elitism and other variables in Figures A1–A5 in the Online Appendix. This shows that most parties are not anti-elitist, while the radical right PVV scores high and some parties on the left and center in between (e.g., SP). Given the structure of our data, we look at the absolute difference in anti-elitism of each of the party pairs.

Secondly, to test the Coalition–Opposition Hypothesis, we need information about whether the two parties are in the coalition or not. We use the same information as above to classify whether pairs of parties are both in the coalition, both in the opposition (with mixed pairs as the reference category).

Thirdly, to test the ideological hypotheses (Economic Hypothesis, Cultural Hypothesis, Environmental Hypothesis, and EU Hypothesis), we look at programmatic positions from the CHES (Jolly et al., Reference Jolly, Bakker, Hooghe, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2022) and, where this is not available, the expert survey of Benoit and Laver (Reference Benoit and Laver2006). We calculate the difference between every dyad on the general left-right dimension, on the economic left-right dimension, on the environmental dimension, and on the immigration dimension (for cultural issues).Footnote 9 In the Online Appendix, we also look at smaller issue categories introduced above to specific dimensions: on spending versus taxation and deregulation for the separate economic categories, the social lifestyle dimension for moral issues, the international security dimension for defense, the decentralization dimension for the issues related to subnational governments, and both anti-elitism and the GALTAN dimension for issues related to democracy.Footnote 10 Given the structure of our data, we look at the absolute difference between the two parties on each of these issues. Table A7 in the Online Appendix shows the correlations between the vote characteristics.

5.7. Modeling

We use multilevel logistic regression to study under what conditions parties vote the same in parliament. We include levels for both the two parties in every pair and for each vote. Model A1 in Table A8 in the Online Appendix is an empty model that shows that most of the variance is at the vote level. We examine the different dynamics on different votes using interactions. These allow us to see whether specific dimensions matter more or less for specific kinds of votes: our hypothesis is about the relative importance of anti-elitism for voting on legislation. One should also note that the dependent variable is similarity in votes, while the variables for policy positions on economics, migration, the environment, and anti-elitism reflect distance.

6. Results

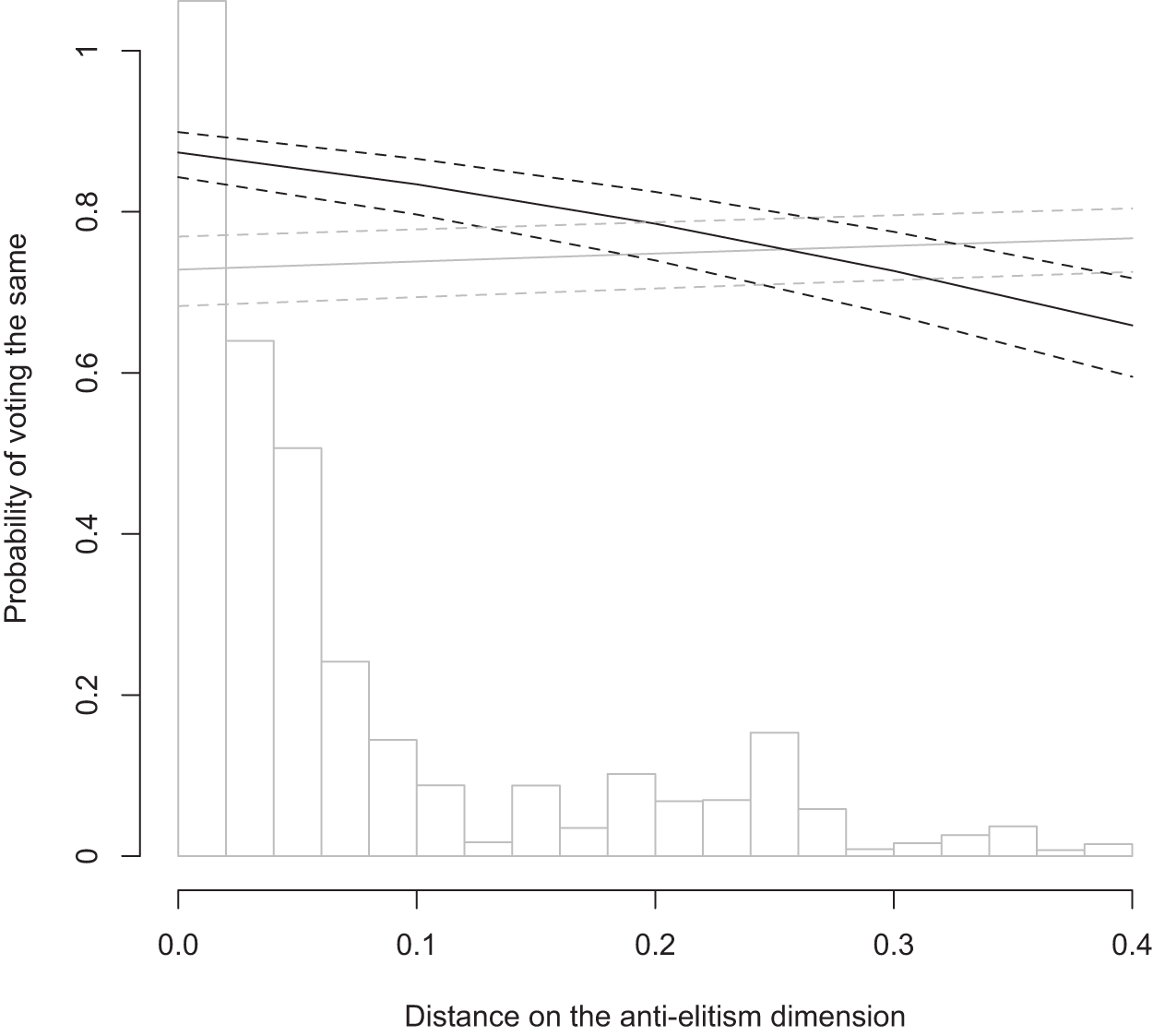

Our key regression is shown in Table 2. We ran a number of alternative models in the Online Appendix. The Anti-elitism Hypothesis proposes that on bills, anti-elitist parties vote in another way than other parties. Anti-elitist parties challenge the consensual political culture of law-making by established parties. Figure 1 shows the pattern for bills and anti-elitism. A pair of parties with identical positions on anti-elitism vote the same on 87% of the bills. Two parties with completely opposite positions on anti-elitism vote the same on 66% of the bills. This is a substantial and significant decline. It also differs substantially from all other votes; we see a nonsignificant increase from 73% to 77%. That means that anti-elitism plays no role on nonlegislative votes (when we control for alternative explanations). All in all, this corroborates our hypothesis. But we cannot see whether including anti-elitism increases the predictive power of the model: Model A2 in Table A8 in the Online Appendix drops anti-elitism from the model. We can compare the AIC in Model 1 and Model A2 to see whether adding this variable increases the predictive power substantively. Adding this variable reduced the AIC by more than 10 points, a clear indication that a model with anti-elitism has stronger explanatory power than the model without (Burnham and Anderson, Reference Burnham and Anderson2004, p. 271).

Figure 1. Voting similarity, anti-elitism, and bills.

Table 2. Multi-level logistic regressions

Note:

*** p < 0.001;

** p < 0.01; *p < 0.05.

In the Online Appendix, we test the robustness of this relationship in three ways, by dropping the left-right dimension, by changing the definition of coalition party and by looking at more types of votes. First, Model A3 in Table A8 in the Online Appendix drops the left-right dimension. This would allow us to see to what extent the extremist positions of these parties affect the results. Excluding this variable does not affect the predictive power of the anti-elitism dimension or the interaction with legislation on the likelihood of voting the same. In Model A4, we make an alteration to one of the control variables (coalition participation). One of the most anti-elitist parties (the PVV) was a support party for a minority government, which we can see as an opposition party, but one could argue that it effectively operated as a coalition party. This may affect the relationship between voting patterns and anti-elitism. We do not find that this is the case. Model A5 adds a variable whether the vote is an amendment. This may matter because we look at the difference between votes on bills and other votes. However, including this variable does not affect our interpretation of the interaction relationship between anti-elitism and legislation.

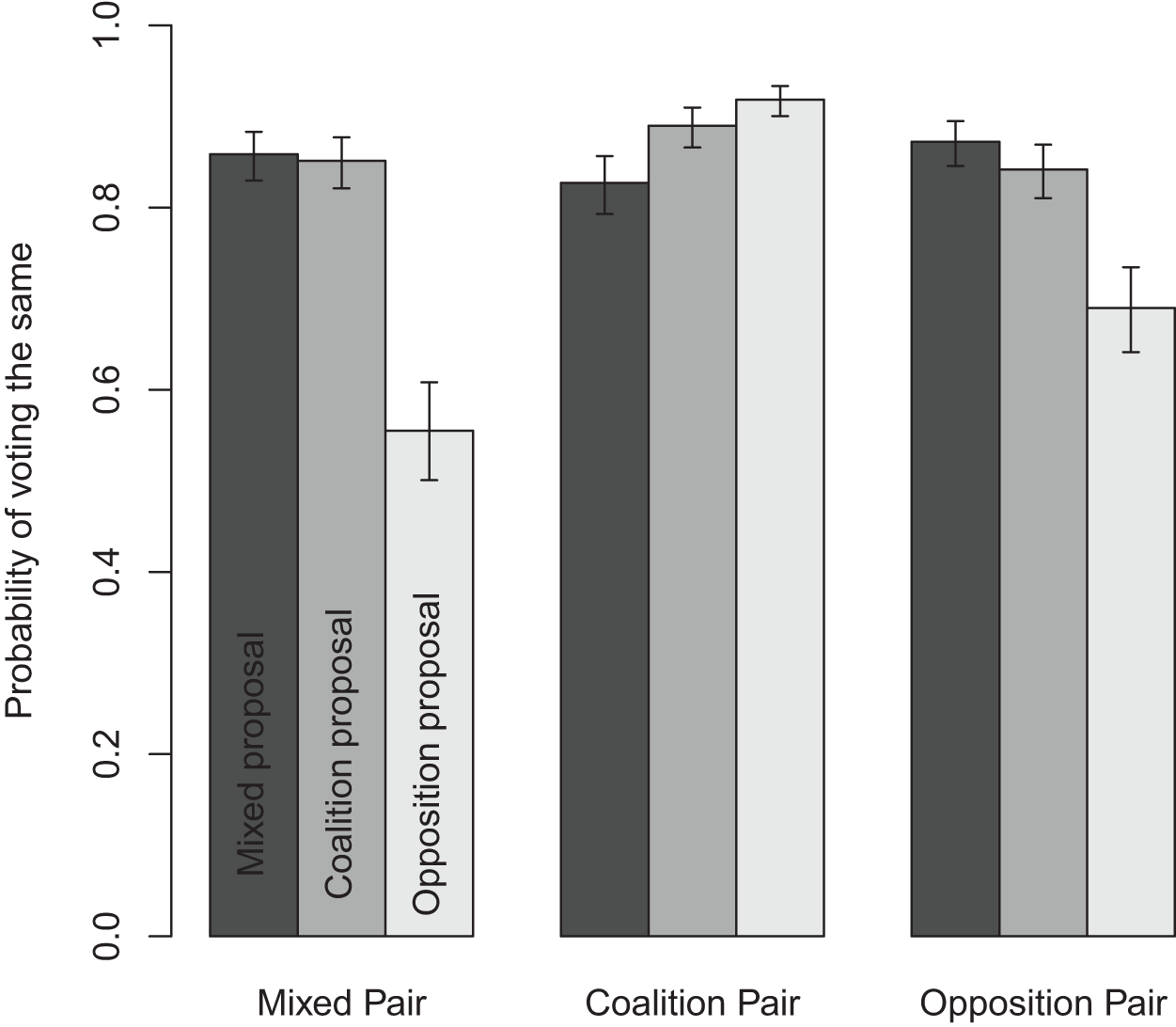

Next, we turn to the Coalition Hypothesis: Figure 2 shows to what extent different pairs of parties vote the same on proposals made by different parties. The underlying idea is that the proposals of opposition and coalition parties are qualitatively different. Coalition party proposals operate within the space allowed by the coalition agreement, while opposition party proposals likely seek to drive a wedge between coalition parties. Coalition parties will operate in a united fashion to dismiss the opposition proposals, while such coordination will not play a role for coalition party proposals. Therefore, we first focus on coalition pairs. As expected, coalition parties are most united on proposals made by opposition parties. They vote the same on 92% of them. This is more than on proposals sponsored by coalition parties (89%) or proposals signed by a mix of coalition and opposition parties (83%). The low voting similarity on the latter can be explained: issues where one coalition party works with an opposition party are likely to be those issues where the coalition accepts to agree to disagree. For opposition and mixed pairs, we see the opposite pattern: the highest level of agreement on proposals involving at least a coalition party and lower agreement on proposals from opposition parties. The low level of agreement among opposition parties on proposals from opposition parties likely reflects the diversity among the opposition parties: if opposition parties can freely introduce their pet projects, mainly for position-taking purposes, it is not unreasonable that other opposition parties often do not agree with those.Footnote 11 As noted above, in Table A8 in the Online Appendix, we examine an alternative operationalization of the coalition/opposition division, changing the PVV from opposition to coalition party in 2010–2012 (Model A4). If we include the PVV as a coalition party when it was a support party, the patterns remain the same.

Figure 2. Voting similarity, coalition and opposition proposal, and pairs.

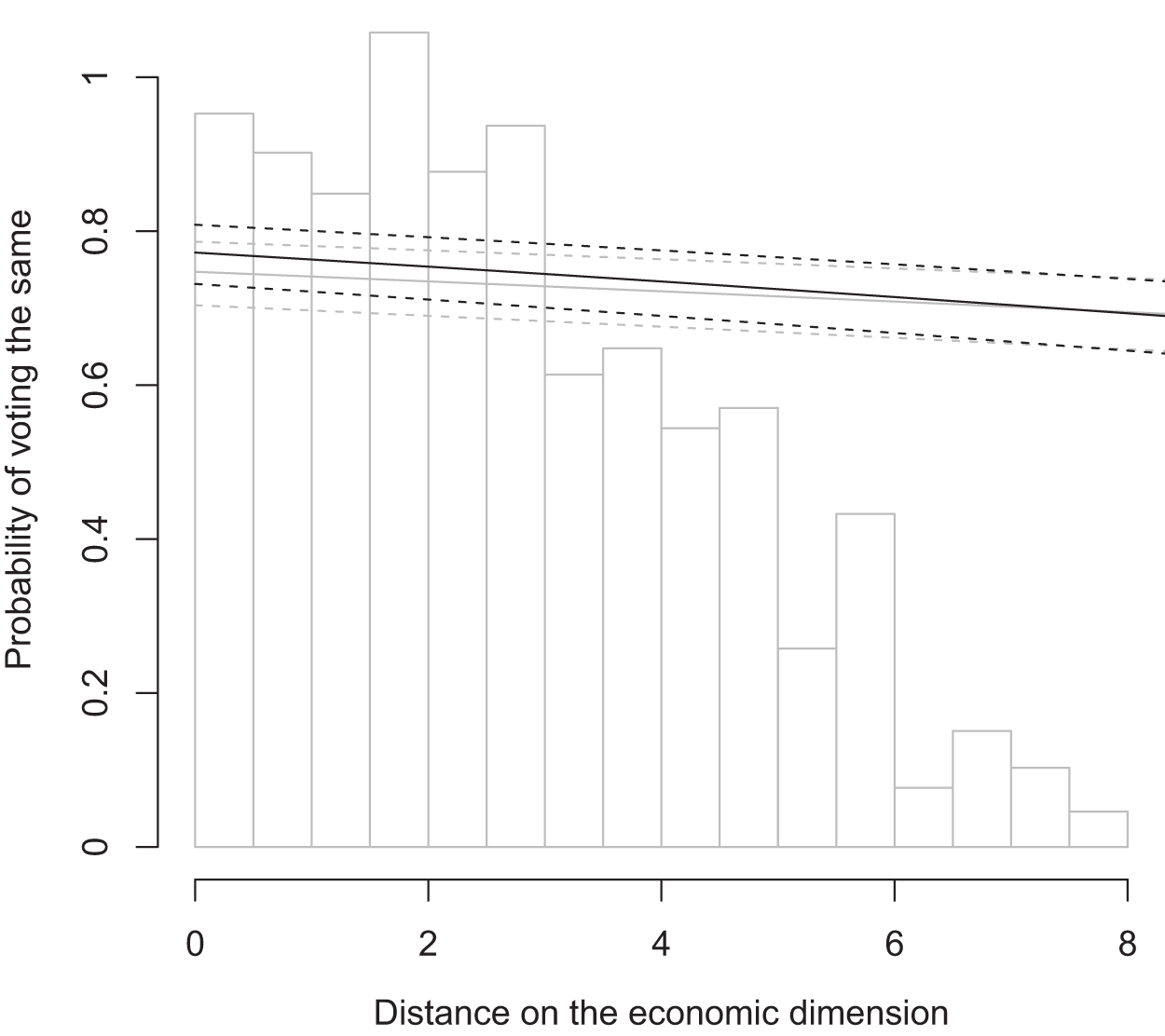

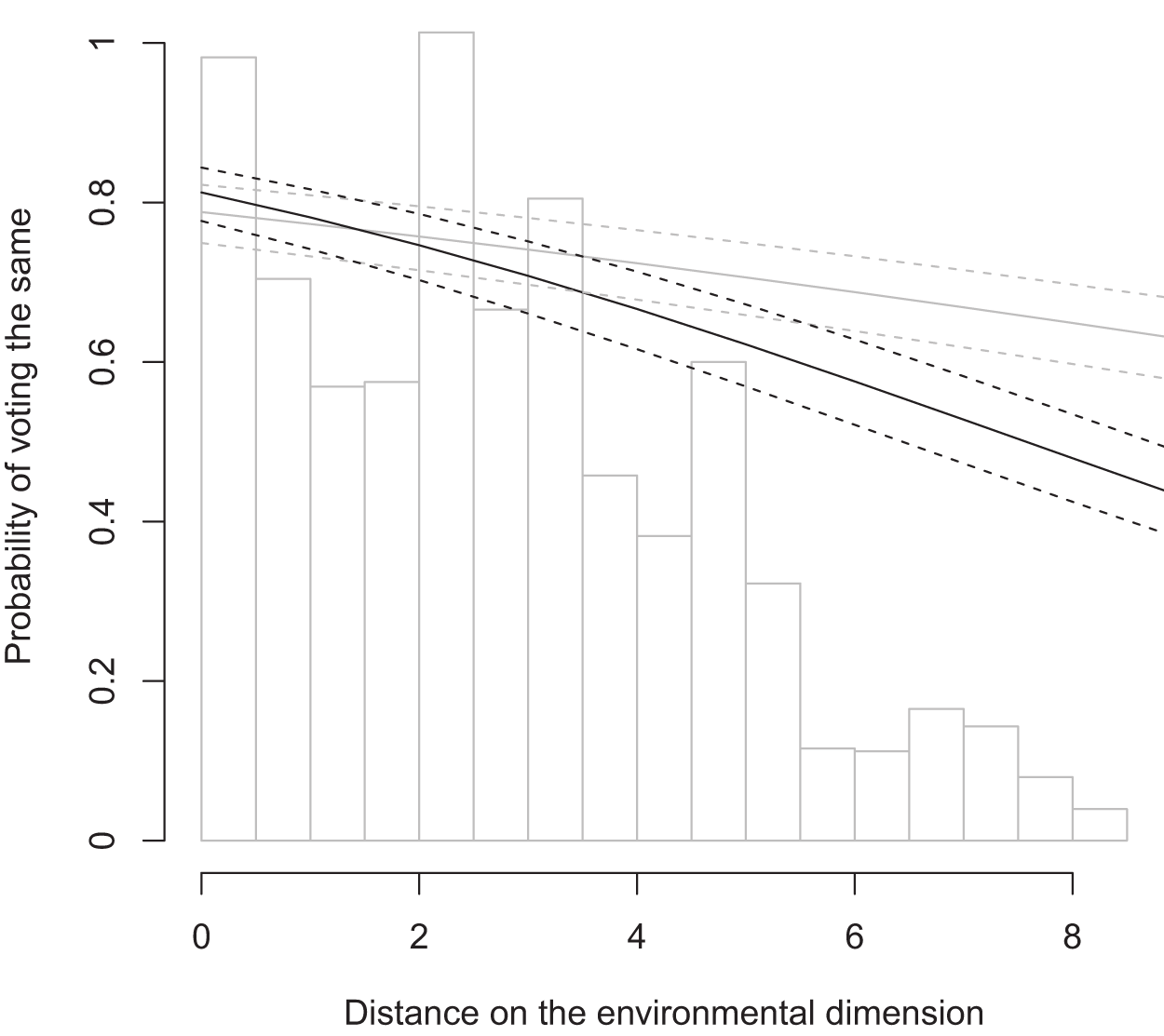

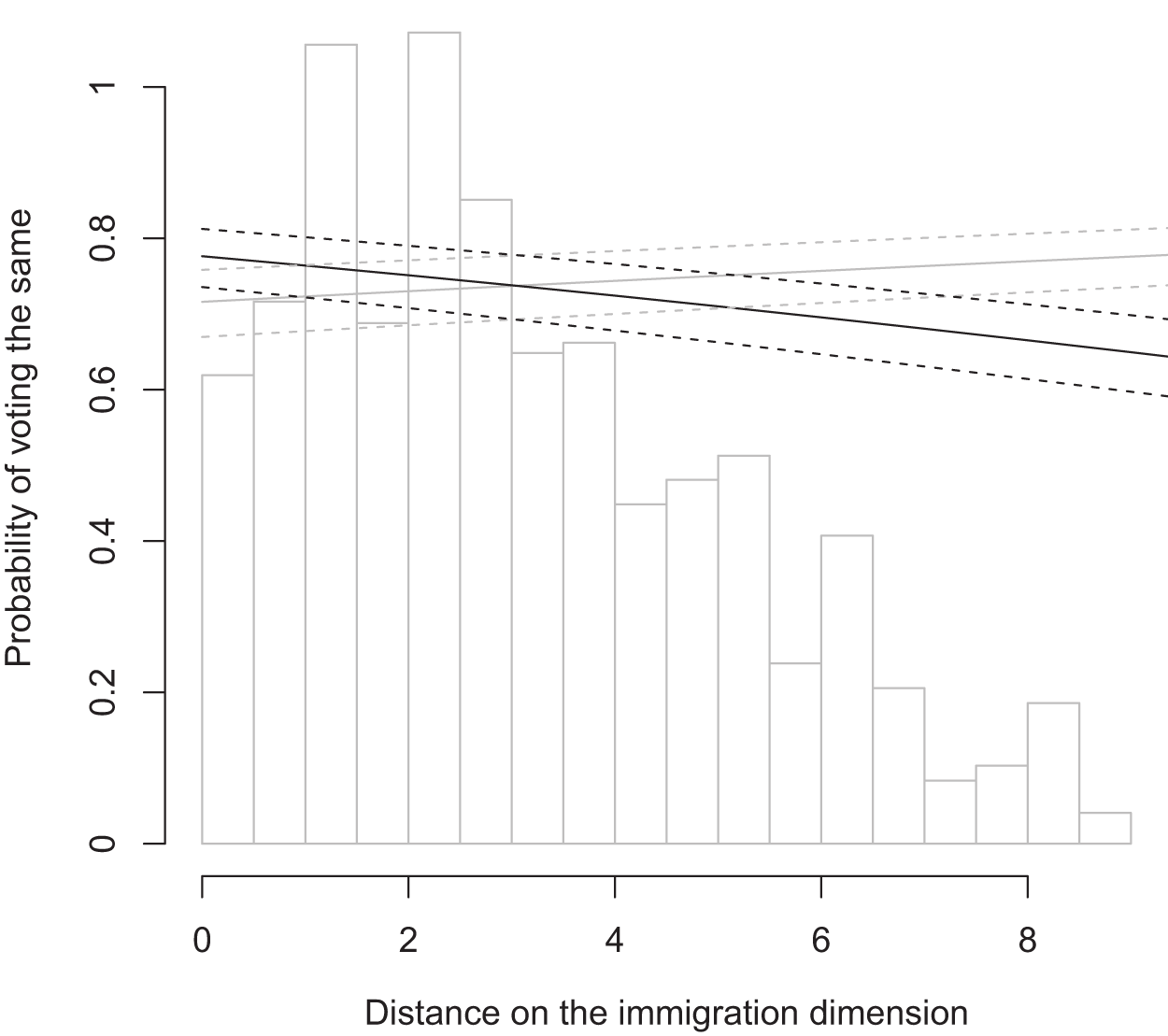

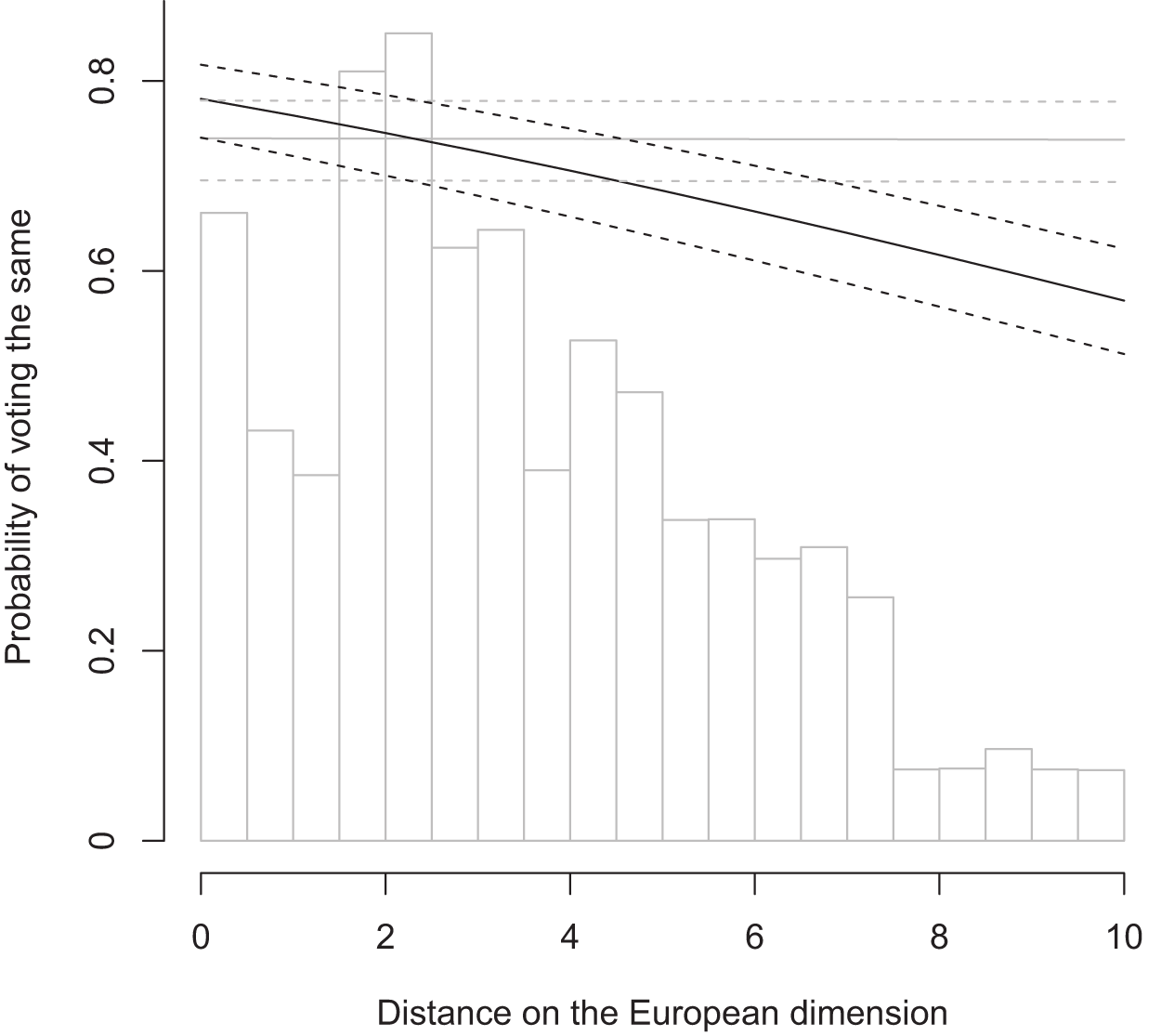

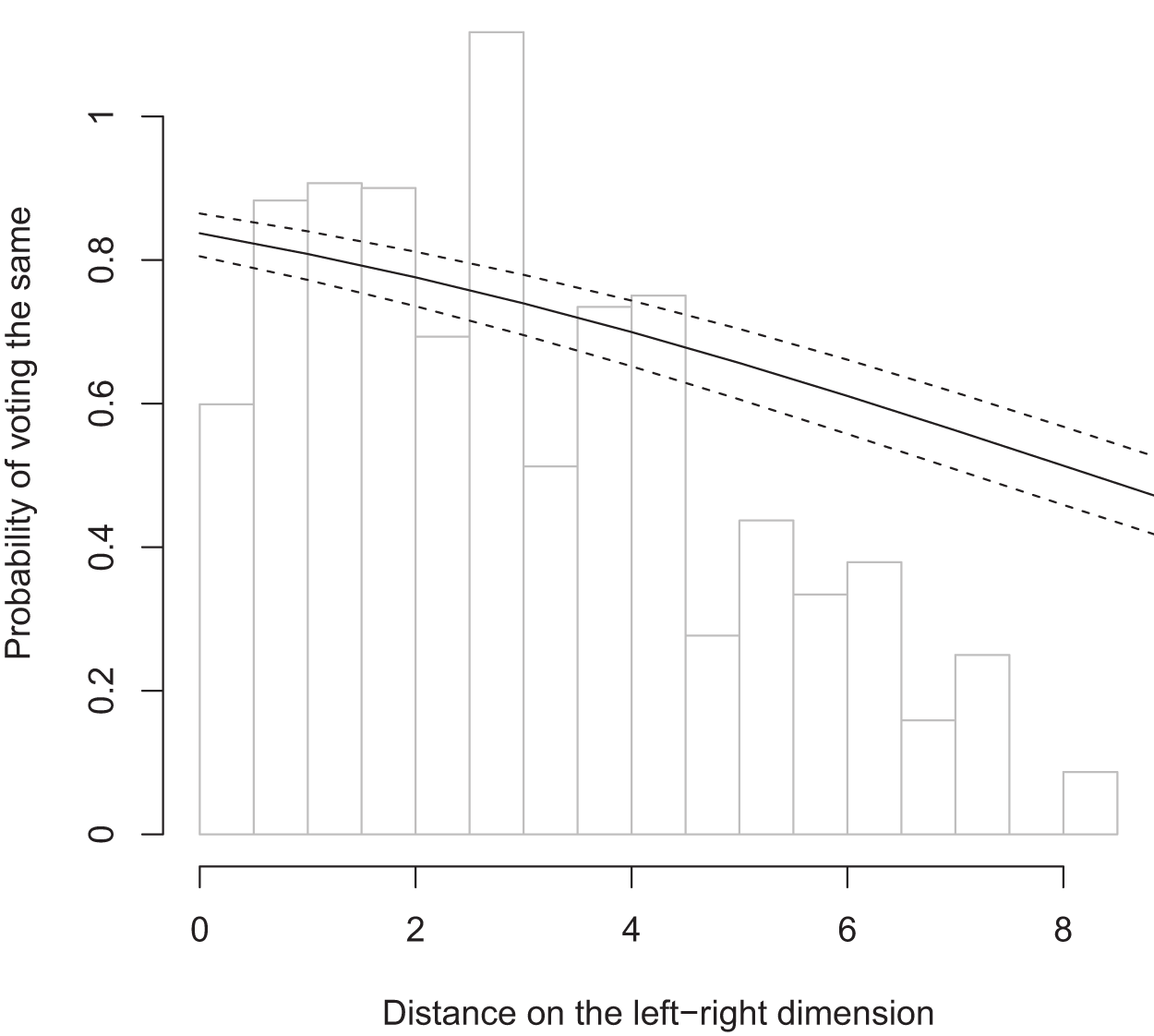

Finally, we turn to the four hypotheses related to ideology. The general idea is that distances on specific dimensions matter more on specific issues: that is on economic issues we expect the economic left-right dimension, which divides socialists from economic liberals to matter (Economic Hypothesis); on cultural issues (e.g., migration), we expect the cultural left-right dimension, which divides patriotic parties from cosmopolitan parties, to matter (Cultural Hypothesis); and on environmental issues, we expect the dimension which divides pro-growth from pro-environmental issues to matter (Environmental Hypothesis); and finally on EU issues, we expect the pro-/anti-EU dimension to matter (EU Hypothesis). Figure 3 shows the pattern for economic issues. It shows that on economic issues, two parties that have the exact same position on the economic dimension vote the same on 77% of the votes. Two parties that have completely opposite positions on the economic dimension vote the same on 67% of economic votes. This is a marked decline. But it does not differ substantially from all other votes, where the decline is from 75 to 68%. Figure 4 illustrates the pattern for environmental issues. Two parties that have an identical position on the environmental dimension vote the same on 81% of environmental votes. A pair of parties with completely opposite environmental positions vote the same on 38% of environmental votes. This is the largest decline we observed. It differs substantially from all other votes, where the decline is from 79% to 61%. Figure 5 displays the pattern for the cultural issues. On these cultural issues, a pair of parties that have the same position on the immigration dimension vote the same on 78% of the votes. Two parties with completely opposite migration positions vote the same on 63% of the cultural votes. This is a marked decline. It also differs substantially from all other votes, where we instead observe an increase: that is, the migration dimension (when we control for the left-right dimension) only matters for cultural issues. Figure 6 concerns the EU integration dimension. If two parties completely agree on EU integration, they have a 78% chance to vote the same on EU issues. Two parties that completely disagree on EU integration vote the same on 57% of the votes. On non-EU issues, parties vote the same in 74% of the votes, independent of their agreement on EU integration: that is, the EU dimension only matters for European issues. When considering these patterns, it is important to note that we also control for the general left-right dimension (Figure 7). This is a strong explanation of voting behavior: if we move from a pair with complete agreement on the left-right to a pair with complete disagreement, the share of votes in favor declines from 84% to 42% in a model with all programmatic differences. Dropping the general left-right dimension increases the explanatory power of the economic dimension outside of economic issues and the migration dimension outside of cultural issues.

Figure 3. Voting similarity, economic left-right dimension, and economic votes.

Figure 4. Voting similarity, environmental dimension, and environmental votes.

Figure 5. Voting similarity, immigration dimension, and cultural votes.

Figure 6. Voting similarity, European integration dimension, and European votes.

Figure 7. Voting similarity and left-right dimension.

In Table A9 in the Online Appendix, we also investigate six additional smaller issue categories and issue dimensions. Specifically, we look at more specific economic dimensions (testing the economic dimension in greater detail); we look at the possibility that the GALTAN or the anti-elitism dimension matters for votes related to democratic reform (looking at different mechanisms that may play a role for anti-elitism); and we add dimensions on specific issues such as decentralization, morality, and international security as one may argue that the selection of four issues and dimension above did not cover all possibilities. Half of these clearly matter: the decentralization dimension clearly matters to issues related to decentralization, the social lifestyle dimension matters for issues related to morality, and the international security dimension has a marked effect on defense issues. When it comes to issues related to democracy, both the GALTAN and the anti-elitism dimension show some effect but substantially these are smaller than the previous three. Splitting the economic dimension into one concerning public sector spending and one concerning private market regulation does not substantively improve our understanding because neither dimension matters substantially more in their respective domains than the economic left-right dimension does for the economic issues in general. All in all, including these different ideological dimensions does not substantively affect our interpretation of the key expectations.

7. Conclusion

We looked at the importance of anti-elitism for parliamentary voting. We find clear evidence that anti-elitist parties vote differently on legislation from other parties. Where most parties in the Dutch parliament cooperate in consensual work on legislation and vote for most legislation, anti-elitist parties take a much sharper stance on legislation. We find strong evidence that on legislative votes anti-elitism matters, while it has no predictive power on nonlegislative votes. There are also indications that differences in anti-elitism matter more on issues related to democratic reform.

We also looked at the division between opposition and coalition and four ideological dimensions. This gives us a unified understanding of voting in parliaments, taking into account both party and proposal characteristics. We see that who proposes a vote affects how parties vote: opposition party proposals get a unified response from coalition parties, while they vote in a more divided way on proposals that one of them sponsored. This likely reflects the liberty opposition parties can take in their proposals (countering the compromises in the coalition agreement), while proposals involving coalition parties reflect issues where parties agree to disagree. Future research may want to examine more precisely how constraints of coalition governance affect not just the voting behavior of coalition parties but also what they propose.

We find that the substance of a proposal also matters: different proposals fall in different domains and activate different dimensions. We find strong evidence that for cultural issues (migration and security), European and environmental issues voting patterns are different than on other issues. We find little evidence that this is the case for economic issues. The absence of an effect here may be explained that voting on many issues has economic implications and involves choices on government spending.

What do these results say beyond the borders of the Netherlands? We believe that our results speak to a wider set of countries that share characteristics of the Dutch system, such as parliamentary government, the presence of multiparty coalitions, and the ability of opposition parties to influence the agenda. We believe that our results speak to the study of voting behavior in parliaments more generally and in particular to countries where parties of the left and right often govern together, such as Germany, Austria, Belgium, and Finland. It is likely that in the systems anti-elitist parties disrupt consensual voting patterns, that programmatic differences on specific issues structure voting behavior, and that proposals by the coalition and opposition elicit different reactions from coalition and opposition parties. In systems with stronger government control of the agenda, the coalition–opposition division may matter more.

Our method, the proposal-specific dyadic method, is an important methodological innovation. It allows for a far more complete analysis of parliamentary voting beyond the spatial methods that are commonly used, which do not allow one to observe nuanced patterns in the data. Specifically, it allows us to compare the strengths of different drivers of voting behavior concurrently. This allows us to see the importance of other factors other than the left-right and the coalition–opposition dynamic, such as anti-elitism. Moreover, by means of interactions, it allows us to get a far more precise grasp about the conditions under which specific factors matter.

One dimension that this paper so far has overlooked is time. It may be useful to distinguish how the majority status of the government affects voting patterns: is the division between coalition and opposition parties weaker when the coalition does not have a majority in the lower house (because at least one opposition party is necessary for a majority)? Or is it actually stronger (because a nay-vote of the opposition parties now has more than symbolic value)? Does it matter when the coalition does not have a majority in the upper house (Ganghof and Bräuninger, Reference Ganghof and Bräuninger2006; Hohendorf et al., Reference Hohendorf, Saalfeld and Sieberer2021)? What do voting patterns look like in periods of caretaker government (Van Aelst and Louwerse, Reference Van Aelst and Louwerse2014)? Future research may want to delve further into the temporal dimension.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2026.10090. To obtain replication material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/MOO2A9.

Acknowledgements

This article is based on Luc Vorsteveld’s master’s thesis that he wrote under supervision of Simon Otjes at the Institute of Political Science at Leiden University. We are grateful for constructive comments of Tim Mickler, who acted as the second supervisor. The paper has previously been presented at the Annual Conference of the Dutch and Flemish Political Science Associations in 2023 and at the Lunch Seminar of the Institute of Political Science of Leiden University. We are grateful to all the participants of those sessions, the anonymous referees, and Nathalie Giger, as editor of PSRM, for their careful comments and suggestions and to Parushya Parushya, the replication analyst of PSRM, for their keen eye for detail.