1. Introduction

A democracy’s decision to go to war is the result of a complex social decision-making process involving politicians, military personnel, lawyers, parliaments, experts, allies, intelligence personnel and, last but not least, public opinion.Footnote 1 It is governed by international norms, notably the prohibition of the use of force in Article 2(4) of the United Nations (UN) Charter and principles of the just war tradition (for a discussion, see, e.g., Erskine, Reference Erskine2024b, pp. 178–179; Erskine & Davis, Reference Erskine and Davis2025). Integrating Artificial Intelligence (AI)-enabled systems into such a highly complex social process does not simply increase complexity; it utterly changes the playing field.Footnote 2 It leaves us with an unprecedented situation in which a non-human entity substantially influences decision-making processes with incalculable socio-political consequences. Incalculable, because while decisions taken by humans can be morally evaluated, politically scrutinized, and legally adjudicated, decisions by machines cannot.

Currently, decisions on the resort to force are only indirectly influenced by AI-based systems (Erskine & Miller, Reference Erskine and Miller2024a, p. 138); however, the “automation boom” (McLaughlin, Reference McLaughlin2017) and “AI military race” (Garcia, Reference Garcia2024) increase the likelihood of machines playing a more direct and significant role in resort-to-force decisions, and also in target selection and engagement (for an overview, see Deeks, Reference Deeks2024; Deeks, Lubell & Murray, Reference Deeks, Lubell and Murray2018; Erskine & Miller, Reference Erskine and Miller2024a).Footnote 3 One category of AI systems relevant to resort-to-force decisions, and the focus of the present article, is decision support systems (DSS) that could assess huge amounts of data to identify imminent attacks and hostile behavior, thereby informing executive decisions on waging war. The prospect of integrating machines into the decision-making process on war initiation raises multiple ethical concerns (Chiodo, Müller & Sienknecht, Reference Chiodo, Müller and Sienknecht2024; Davis, Reference Davis2024; Erskine, Reference Erskine2024a, Reference Erskine2024b; Logan, Reference Logan2024; Renic, Reference Renic2024, Reference Renic2025; Sienknecht, Reference Sienknecht2024). In this article, I will focus on one of the key moral questions: How can we assign responsibility in cases where AI systems shape the decision-making process on the resort to force?

Questions concerning moral responsibility (see, e.g., Barry, Reference Barry and Erskine2003; Erskine, Reference Erskine and Erskine2003; Gaskarth, Reference Gaskarth2011, Reference Gaskarth2017; Hoover, Reference Hoover2012) are increasingly important given the changing nature of warfare through the integration of AI-based systems.Footnote 4 Responsibility is a normative and relational concept, which means being answerable for social acts. It involves a subject (who is responsible?), an object (to whom or what is the responsibility owed?), and a normative framework (what rules or principles govern this responsibility?). Traditionally, ultimate responsibility is placed on the leader of an organization or institution. However, this model is challenged in contexts involving human-machine collaboration, because AI-driven systems often produce outcomes through opaque processes. They further lack ethical awareness, consciousness, and moral understanding, and thus disqualify themselves as moral agents. Furthermore, decision-making processes influenced by AI are characterized by the participation of a multitude of actors from different social systems (politics, the law, economics, and the military), which makes identifying a single responsible individual problematic.Footnote 5 Thus, the opacity of AI systems on the one hand, and the “problem of many hands” (Thompson, Reference Thompson1980) on the other hand, prevent us from attributing responsibility directly to one individual. This leaves us with a socio-technical “responsibility gap” (Matthias, Reference Matthias2004), which is inherent in each decision influenced by machines. Responsibility gaps mean that “the traditional ways of responsibility ascription are not compatible with our sense of justice and the moral framework of society because nobody has enough control over the machine’s actions to be able to assume the responsibility for them” (Matthias, Reference Matthias2004, p. 177).

To address this socio-technical responsibility gap in resort-to-force decision making characterized by AI systems, I build on the concept of proxy responsibility (Sienknecht, Reference Sienknecht2024), and suggest installing a corresponding institutional structure that would support it. Proxy responsibility means that an actor takes responsibility for the decisions made by another actor or “synthetic agent” (Erskine, Reference Erskine2024a) who cannot be attributed with responsibility (in the present case, the machine). In this sense, human actors are installed to take responsibility as a substitute, thus a proxy, for the decisions of the de facto agent. In other words, when direct responsibility relations cannot be established, the type of responsibility taken by other human subjects who are part of the decision-making process is described as proxy responsibility.Footnote 6 This substitution is normatively required in situations in which synthetic agents are integrated into the decision-making process. The underlying argument is that it is morally unfeasible to potentially create devastating outcomes and large-scale human suffering without an identifiable, responsible subject.

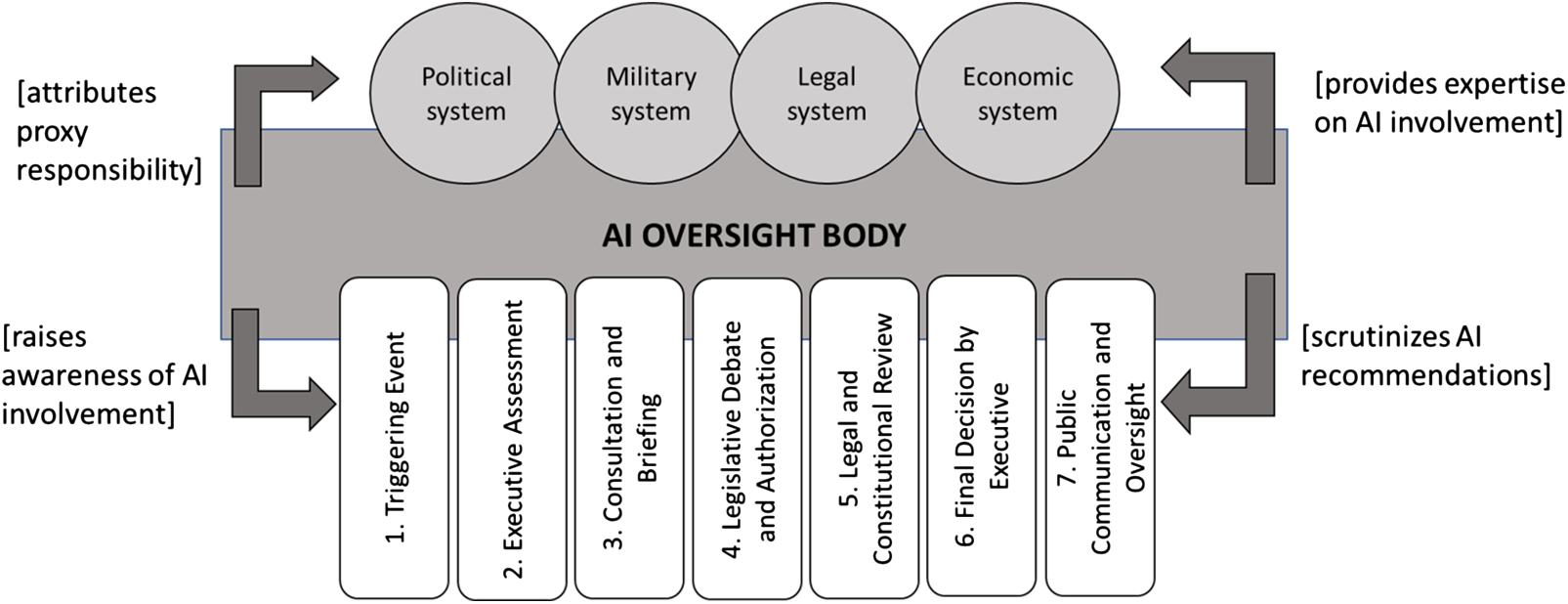

To install proxy responsibility, I suggest integrating an AI oversight body into the organizational decision-making structures on the resort to force. This oversight body would ensure the respective actors’ awareness of the integration of AI systems and their limitations on the one hand, and oversee the AI system’s impact on the decision-making process on the other hand. Situated at the nexus of the political, military, legal, and economic systems, the AI oversight body should integrate technical, political, and ethical competence and expertise, and advise the respective groups in the decision-making process on the resort to force. Such an AI oversight body would help to address responsibility gaps for decisions made by AI systems, since it would serve as a consultation body for AI-induced decisions, as well as function to raise awareness between the involved actor groups in the economic, political, military, and legal system.Footnote 7 This is especially relevant in the specific context of resort-to-force decision making, in which AI systems fulfil routine tasks and often have a dual-use character, which might make them seem less problematic compared to AI systems on the battlefield. In short, I suggest an institutional response that leads to stable structures that can address, although perhaps not overcome, the socio-technical responsibility gap and guarantee that the involved actors possess the necessary knowledge to act autonomously and intentionally, the prerequisite of responsibility attribution (Fischer & Ravizza, Reference Fischer and Ravizza1993; Nelkin & Pereboom, Reference Nelkin and Pereboom2022).

In the next step, I provide an overview of how responsibility relations change when AI systems are integrated into the decision-making process by distinguishing between the technological and organizational challenges. In Section 3, the technological specificities and the problem of many hands in regard to a potential responsibility gap will be discussed. Additionally, I scrutinize central approaches in the literature that aim to address socio-technical responsibility gaps. While central approaches in the literature have addressed socio-technical responsibility gaps and enhanced our understanding of the multidimensionality of potentially responsible actors and their relations with each other (especially in human-machine teaming contexts), most of these approaches focus on individual responsibility attribution in the context of use-of-force decisions concerning Autonomous Weapon Systems (AWS), thereby leaving aside the question of the necessary preconditions for assigning (what can only be proxy) responsibility in the first place. In Section 4, I define the concept of proxy responsibility and lay out in detail the aforementioned institutional response to responsibility gaps in the resort to force. Although similar factors are relevant in use-of-force and resort-to-force decision making, they also differ in some central aspects. For example, the individual roles and positions of soldiers and commanders are crucial in tactical (use-of-force) decision making, whereas the decision to go to war (resort-to-force decision making) consists of individuals and institutions of different social systems (political, military, economic, and legal). By referring to the literature on institutions and organizations, I discuss a potential integration of an AI oversight body into the organizational structures of the political/military system, its main task, and its composition. I argue that the integration of an AI oversight body creates the necessary preconditions for attributing proxy responsibility to individual actors. In Section 4.3, the applicability and limitations of proxy responsibility are discussed in more detail. In the conclusion, I reflect on the broader implications and applicability of the concept and discuss further avenues for research.

2. Decision making on the resort to force

“Wars do not occur by chance. They are not the result of some fanciful alignment of the planets and moons; rather, states choose to start them.” (Reiter & Stam, Reference Reiter and Stam2002, p. 10)

Wars are made up of a complex string of decisions, from determining if and how to monitor potential adversaries, over strategic decisions about whether, when, and how to go to war, to tactical decisions on the battlefield. In democracies, we expect both strategic decisions to wage war and tactical decisions to use force within a conflict setting to be carefully weighed, proportional, and in line with international norms. The legal frameworks of democratic states, therefore, detail how such decisions should be made.

2.1. Democratic decisions to wage war

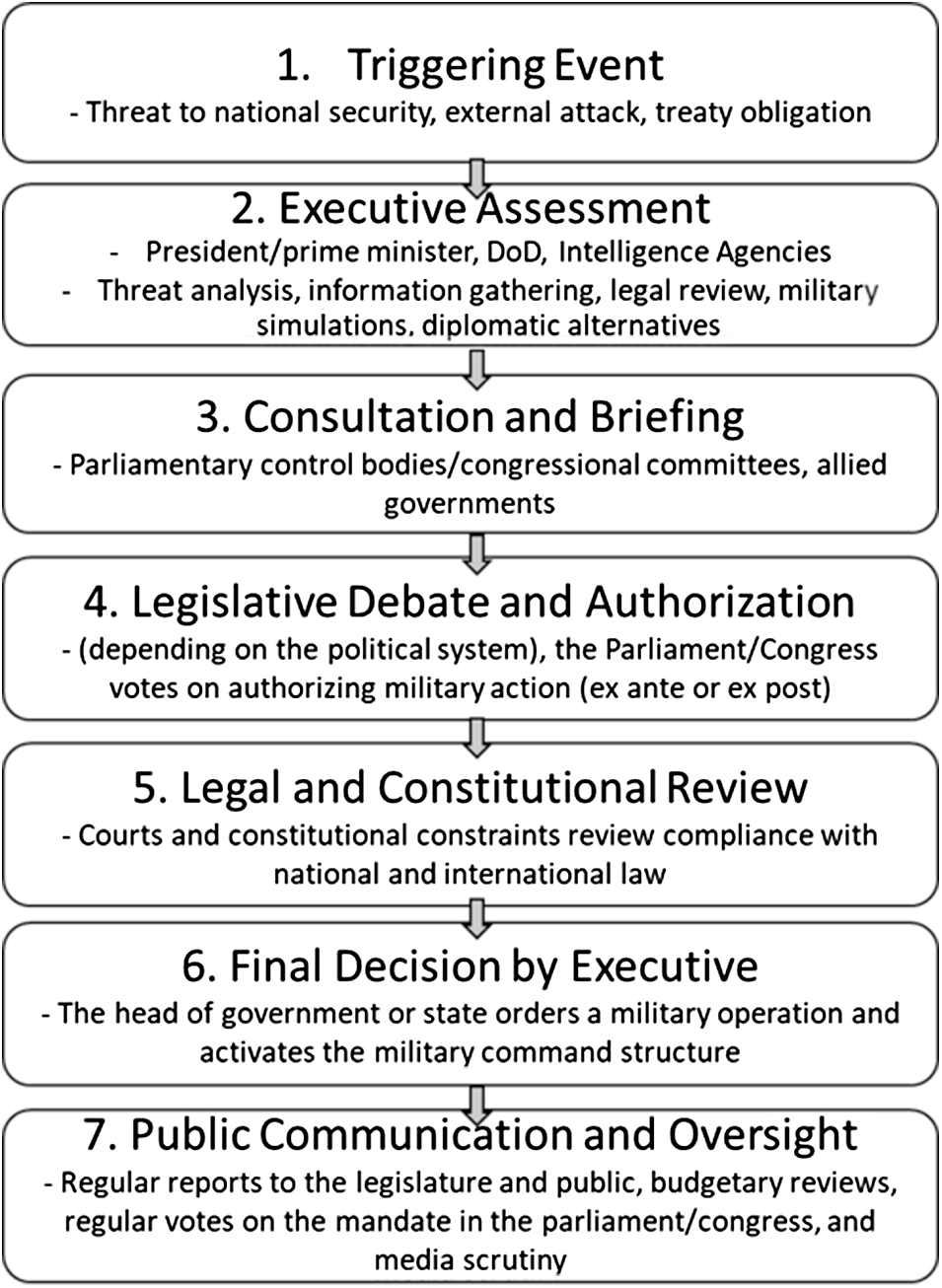

In democracies, the decision to go to war is usually made by civilian leaders, with military advisers, legal experts and political counsellors playing crucial advisory roles (Saunders, Reference Saunders2024). The political and military systems are kept separate to prevent the military from gaining undue power over democratic governance (Schulzke, Reference Schulzke2013, p. 209), but they remain closely linked to ensure their compatibility. The commander-in-chief relies on the information provided by the military system or, more precisely, the intelligence apparatus. In concrete terms, war-related decisions are based on information and interpretations of intelligence analysts, military strategists and lawyers, who predict the behavior of the adversary state, present a variety of military options, assess the prospects of military success and evaluate the legitimacy and potential legal challenges of each pathway. Democratic institutions, such as parliaments, serve as a control mechanism since they are usually required to (ex-post) confirm the government’s decision.Footnote 8 Additionally, the public plays a crucial role in the decision making because democratically elected leaders will be held to account by their constituencies and can be voted out of office (Reiter & Stam, Reference Reiter and Stam2002). Figure 1 summarizes the main steps democracies take when deciding to go to war:

Figure 1. Decision making on the resort to force in democraciesFootnote 9 (source: author).

This flowchart also demonstrates how decision-making processes on the resort to force are influenced by a variety of actors and social systems. Primarily, the political, military, and legal systems and their respective actors and institutions contribute to the decision, accompanied by the media system. Although these systems operate under different rationales, they are structurally coupled and interdependent (Luhmann, Reference Luhmann1998, pp. 92–119). This means that political decisions and media coverage can influence military operations, politically allocated military equipment and financial resources determine the range of military options, and political feasibility, conveyed through the media system, as well as legal constraints determine the extent to which the military can be utilized. This interdependency means that the decision to resort to force is always the result of the decisions of many different actors, both individual and collective, stemming from many different social systems. Given the already complex decision-making process of conducting war, the question then emerges of how the integration of AI-based systems into the decision-making process influences the process. To answer this question, I will first give some examples of AI-based technology that is likely to be integrated into the resort-to-force decision-making process, and discuss potential problems that might arise from technological specificities and the organizational structures of the decision-making process itself. Of course, a purely human decision-making process is far from being flawless (see, e.g., Jervis, Reference Jervis1976, Reference Jervis2006; Levy, Reference Levy2005). Nevertheless, the point here is that the integration of machines leads to new challenges and moral problems that need to be addressed.

2.2. AI-systems in decision making on the resort to force

In a digitalized age, the use of AI systems to analyze information on adversary behavior is highly likely, not only during an actual war situation but also in anticipation of escalation. Several AI-based systems are likely to support decisions to go to war, from forecasting tools to surveillance technology (Puscas, Reference Puscas2023). AI-based programs will likely be used across intelligence processes to extract key information from various sources, identify patterns in large amounts of data, and trace back hostile behavior, for example, troop movements. Large Language Models (LLMs) will probably be used to prepare reporting, and are already used by some as an internal generative AI-assistant for summarizing, analyzing, and producing text (e.g., in the Dutch Ministry of Defence, see example of Dutch DefGPT).Footnote 10 In contrast to weapon systems that conduct target selection and target engagement (downstream tasks), DSS in resort-to-force decision making conduct so-called upstream tasks (Grand-Clément, Reference Grand-Clément2023), which contribute to the decision process. Although not directly involved in combat, AI applications in upstream tasks can have similarly devastating effects, since they might undermine the adherence to international norms of restraint (Erskine, Reference Erskine2024b), substantively influencing decisions to go to war. Such upstream tasks “occur prior to the narrow task of target selection and target engagement” (Grand-Clément, Reference Grand-Clément2023, p. 6).

Grand-Clément distinguishes between 18 upstream tasks that are currently already conducted by AI systems and can be grouped along four different functionalities (Grand-Clément, Reference Grand-Clément2023, pp. 12–13): First, applications that serve command and control (C2) functions, which include target analysis, developing mission plans and risk mitigation, as well as impact assessment. Second, information management, which includes the processing of data, analysis of data, and the synthesis of key points from data analysis and the dissemination across the chain of C2. Third, AI systems in logistics support the planning of deployment and provide real-time monitoring. And fourth, tasks like training military personnel by developing different simulations. These are some of the main functional areas in which AI systems support or conduct military tasks in the resort to force. The strength of AI systems is the capacity to identify patterns in huge amounts of data, which are not accessible to human cognition. While the speed of analysis and the amount of processable data are unparalleled, in the future, AI-based systems will also be used to predict actor behavior and hostile activity, for example, by sentiment analysis, geolocation of images, and the monitoring of combat capabilities (Grand-Clément, Reference Grand-Clément2023). Especially the early steps (1–3) of the decision-making process (Fig. 1) lend themselves to AI-driven decision support for upstream tasks (from identifying a threat to national security, to intelligence gathering and recommendations based on military simulations).

But what does the integration of AI systems mean for the identification of a responsible subject in the chain of decision making? Can the developer be held responsible for a machine’s decisions that they could not foresee? Is the integrator responsible for not considering all possible wrongdoings by a machine, even those that are not obvious and could not have been anticipated?Footnote 11 And should the head of a state be responsible for following a machine’s recommendation to initiate war when this recommendation was based on the machine’s erroneous interpretation of intelligence data?

3. The responsibility gap and theoretical approaches to address it

The interplay between artificial and analogue elements in the decision-making process raises questions about the allocation of responsibility. To recall, responsibility is a normative and relational concept that describes the relationship between a subject of responsibility (who takes responsibility?) and an object (to whom/what is responsibility owed?), within a normative framework (by which norms or laws is a responsibility relationship constituted?). The conventional approach is to delegate ultimate responsibility to the head of an organization or institution. This approach is fundamentally challenged in a human-machine context, where outcomes of AI-enabled systems often stem from unclear and incomprehensible processes within the machine itself. As a result, autonomous systems raise profound ethical questions about who can and should be held responsible for what. Can a single human be held responsible for decisions made by a machine that he or she does not fully understand or have the time or even the mental capacity to scrutinize and verify? Can the machine be held responsible for its own decisions?

3.1. Technological specificities

AI systems, especially those based on deep learning, are different from first – and second-wave AI systems in that they are trained to adapt to varying contexts. These AI systems can autonomously shape scenarios and influence outcomes in ways that are not fully predictable, controllable, or even comprehensible. This so-called “black-box problem” (Deeks, Reference Deeks2020; Vogel, Reid, Kampe & Jones, Reference Vogel, Reid, Kampe and Jones2021) makes it difficult to trace back the logic and reasons for a machine’s recommendation. Moreover, the technical functionalities of AI systems influence and limit the horizon of possibilities they present to users, potentially restricting the scope of solutions considered feasible by humans (see for a discussion of the technological specificities, Müller, Chiodo & Sienknecht, Reference Müller, Chiodo and Sienknecht2025).

Sparrow (Reference Sparrow2007) has argued that the autonomy of the system makes it impossible to attribute responsibility for a machine’s actions to any one individual. It would simply be unfair to hold humans responsible for something they cannot control. This line of argument has provoked many responses. Some have argued that machines themselves have responsibility for their actions since they can be considered moral agents (Floridi, Reference Floridi, Kroes and Verbeek2014; Floridi & Sanders, Reference Floridi and Sanders2004; Sullins, Reference Sullins2006); others have rejected this for various reasons (e.g., Erskine, Reference Erskine2024a argues that their lack of “reflexive autonomy” disqualifies synthetic agents as moral agents). One crucial point for disqualifying machines as moral agents is their ignorance of the social practice of blame (Elish, Reference Elish2019; Miller & Bossomaier, Reference Miller, Bossomaier, Miller and Bossomaier2024b; Nissenbaum, Reference Nissenbaum1996). I follow the argumentation that machines do not qualify as moral agents. Fundamentally, machines lack ethical awareness, consciousness, and moral understanding. However, responsibility only holds meaning in social contexts where failure entails consequences like blame or punishment – concepts that are irrelevant to machines. In situations in which machines are integrated into political-military decision-making processes, those harmed by AI actions could never receive justification (Forst, Reference Forst2014) or redress by the culprit. This would leave us with an ethically unacceptable situation.

3.2. The problem of many hands

In addition, the “problem of many hands” (Thompson, Reference Thompson1980; van de Poel, Royakkers & Zwart, Reference van de Poel, Royakkers and Zwart2015) contributes to the responsibility gap. The problem of many hands refers to situations in which several actors contribute to different degrees and at different moments to a single outcome, which makes it difficult to attribute responsibility to anyone. In the present case, many different individuals or organizations stemming from different social systems are part of the development and deployment of a certain AI system. All individual actors who are involved in developing, integrating, and deploying AI-based systems thus contribute to the (potentially harmful) effects of a decision/recommendation by an AI-based system, dependent on their roles in the development and implementation process. Where the head of government is responsible for the decisions to go to war, developers and engineers are responsible for providing a functioning system that has been developed with high-quality training data and can appropriately be deployed in the given scenario (Chiodo et al., Reference Chiodo, Müller and Sienknecht2024). The integrator is responsible for properly implementing the machine into the military structures of decision making,Footnote 12 and the intelligence and military apparatus needs to specify the tasks the machine is supposed to solve and verify its recommendations, while the legal personnel aim to ensure the machine’s alignment with national and international norms.

Thus, responsibility gaps in resort-to-force decision making emerge in a collective setting. In such contexts, it is difficult to assign individual responsibility because the contributions to a given outcome are dispersed among multiple actors, and it is potentially unclear who is morally responsible for it. This complicates ethical evaluations and the attribution of responsibility, leaving us with the above-mentioned responsibility gap.

3.3. Critics of a responsibility gap

In contrast to those who assume a responsibility gap in human-machine contexts, others deny that such a gap exists (e.g., Tigard, Reference Tigard2021). Lauwaert and Oimann (Reference Lauwaert, Oimann and Smuha2025), for example, argue that the integration of AI systems does not necessarily lead to a responsibility gap. In the context of the present discussion they would maintain that, in the end, the final decision to wage war in democracies is made by a political leader. According to this line of argumentation, responsibility would still be relatively easy to attribute. These critics assume that the gap is a construct, since either responsibility can be attributed to someone who did something wrong in the AI lifecycle, or nobody did anything wrong, and then we should not talk of a gap but an accident (Oimann, Reference Oimann2023, p. 12). However, this line of argument disregards the fact that the roles of individuals and organizations participating in the development, integration and usage of autonomous systems are not static or linear. For instance, just because the development process is accomplished, the product is not “finished” when it is delivered to the customer, but continues to self-develop through machine learning.

Consequently, I assume that responsibility gaps necessarily emerge when an AI system is integrated into a decision-making process. They are emblematic of socio-technical systems in which machines are integrated into decision-making processes. In his seminal article, Matthias rightly points to the fact that “[t]he increasing use of autonomously learning and acting machines in all areas of modern life will not permit us to ignore this gap any longer” (Matthias, Reference Matthias2004, p. 183). His concern has been heeded by several researchers who have proposed responsibility concepts that endeavor to address this responsibility gap.

3.4. Approaches to socio-technical responsibility gaps in the use-of-force

In the literature, at least four solutions are discussed to close the gap: “technical solutions, practical arrangements, holding the system itself responsible, and assigning collective responsibility” (Oimann, Reference Oimann2023, p. 12). Approaches favoring a technical solution take the “black-box” character as a starting point, and focus on developing traceable and explainable AI systems, which makes it possible to trace back and identify decisive actors or actions. However, this approach reduces the problem of attributing responsibility to a technological means of identifying causality. Alternatively, representatives of a practical solution mainly refer to either voluntary or forced acceptance of ex ante responsibility (Oimann, Reference Oimann2023, p. 14). Thus, questions of legal liability are at stake; approaches in this tradition dismiss the social function of blaming an individual for harm done and limit their deliberations to material compensation. The third group focuses on the responsibility of the AI systems themselves. Tigard (Reference Tigard2021), for example, argues that AI systems can be punished by restricting their realm of action. But since a machine does not qualify for moral repercussion, this solution seems not to address the actual problem (see elaborations earlier). A fourth strand of literature refers to the concept of “collective responsibility” and discusses responsibility relations from a hierarchical perspective, as in “command responsibility.” This command responsibility describes a form of liability for omission. However, this contains the “risk of insufficiently acknowledging the influence of the system’s self-learning capacities on the hierarchical structure and, at worst, may result in the commander being unfairly held responsible solely on the basis of a particular position in the chain of command” (Oimann, Reference Oimann2023, p. 18).

This latter strand of research on collective responsibility is further differentiated into varying suggestions on how to address the problem of responsibility gaps, ranging from a “shared” (e.g., Erskine, Reference Erskine2014; Nollkaemper, Reference Nollkaemper2018; Zimmerman, Reference Zimmerman1985) or “distributed” responsibility (Conradie, Reference Conradie2023; Floridi, Reference Floridi2016; Schulzke, Reference Schulzke2013; Strasser, Reference Strasser2022), to debates about the responsibility of the developers of the AI (Chiodo et al., Reference Chiodo, Müller and Sienknecht2024; Sparrow, Reference Sparrow2009). The concept of “distributed responsibility” refers to situations in which individual actions alone are morally neutral, but in sum lead to morally good/evil outcomes. The concept of distributed responsibility reflects the entanglement of different actors (the problem of many hands) and their common contribution to a specific outcome. While this approach has furthered the understanding and conceptualization of responsibility, it is not able to provide general guidelines for “apportioning responsibility” (Schulzke, Reference Schulzke2013, p. 213). Seumas Miller’s (Reference Miller2001) approach, on the other hand, has broadened the perspective from an individual to a collective understanding of responsibility. In his view, the basis for collective responsibility is that different individuals carry out their individual actions to jointly realize a goal that each of them has (Miller, Reference Miller2001, p. 65). In the case of AWS, Miller and Bossomaier (Reference Miller, Bossomaier, Miller and Bossomaier2024a) identify collective responsibility among multiple, diverse actors, such as the design team, political and military leaders, intelligence personnel, and operators. They are all “collectively – in the sense of jointly – morally responsible for the deaths resulting from the use of the weapon, but they are responsible to varying degrees and in different ways” (Miller & Bossomaier, Reference Miller, Bossomaier, Miller and Bossomaier2024a, p. 284).

The collective responsibility approach helps us to understand the development process of AI-based systems from a collective point of view and to constructively address the problem of many hands. However, the approach does not explicitly focus on the preconditions that need to be met to attribute responsibility in the first place. Furthermore, the literature on responsibility gaps focuses mainly on decisions on the battlefield regarding the use of AWS, leaving the specificities of the resort-to-force context out of the analysis. While there are similarities, for example, regarding the involvement of different social systems and the complex interplay of actors, there are also fundamental differences in the resort-to-force dimension. In the following, I will describe the particularities of responsibility gaps in the resort to force, and introduce an institutional response to them that provides the preconditions for assigning proxy responsibility.

4. Bridge the gap – proxy responsibility in resort-to-force decision making

To recall, proxy responsibility means that an actor takes responsibility for the decisions made by another actor or by a synthetic agent who cannot be attributed with responsibility. When assigning responsibility for AI decisions to a human actor, the human actor can only be a substitute, thus a proxy, for the de facto agent (in the present case, the machine). To do this, the proxy needs to be aware of the fact that they are substituting for another human or non-human agent, and they have to understand – at least in theory – how the agent for whom proxy responsibility is assumed arrives at the decision or recommendation, and about the limitations of such knowledge in the case of self-learning systems. Since the opacity of the systems prevents us from fully understanding the course of decision making, knowing about potential pitfalls at least enables the users to take the potential flaws of AI-based decisions and recommendations into consideration – a necessary precondition for critically assessing the decisions by a machine. However, currently, we face the problem that politicians often do not understand the technological specificities, while developers do not reflect on the ethical implications of the technology. Moreover, AI systems relevant to decisions on the resort to force are often not as easily detectable as, for example, AWS. I argue that only if an awareness of the integration of AI systems and their limitations are guaranteed by an AI oversight body, can individuals like a head of state be truly responsible for their potentially flawed decision.

4.1. The responsibility gap in decisions on the resort to force

In the following, I focus on AI systems in the resort-to-force decision-making process that fulfil upstream tasks. The potential impact on international peace and security of upstream technology requires a similar amount of attention as given to AWS and appropriate regulations and guidelines for their implementation (see, for a similar claim, Simpson, Reference Simpson and Schraagen2024).Footnote 13 The international community has started to take DSS used in resort-to-force decision making into stronger consideration. Since such types of technology do not actively engage military targets, they are less visible in the decision-making structures and often not subject to public debate. It stands to reason that such AI systems will become “normalized” in the war room much faster, even though they have tremendous potential to do harm. In sum, when it comes to the military domain, upstream task solving is much less visible than downstream task solving (see also Simpson, Reference Simpson and Schraagen2024 on the attention that is attributed to “killer robots” compared to DSS). Moreover, AI systems with upstream tasks are often based on dual-use technology, so commissioning a corporation to develop an AI system can lead to developers not even knowing about the military purpose of the technology they are working on. A representative example of such a situation is Project Maven, in which Google developers were not aware that they were working on an application for military use (Crofts & van Rijswijk, Reference Crofts and van Rijswijk2020).

This “veiling” of AI systems in decision-making structures poses a specific challenge to the attribution of responsibility. To the question of who was responsible (ex post), it adds the question of how to reveal the integration of AI systems in decision-making structures, so that responsibility can be attributed at the individual or institutional level in the first place. In the following section, I argue for implementing an institutional response to address this sociotechnical responsibility gap in the resort to force.

4.2. Setting the conditions for attributing proxy responsibility – an institutionalist response to responsibility gaps in the resort to force

In situations in which machines are integrated into the chain of decision making, the gap that a synthetic agent leaves open needs to be bridged. I have argued earlier that it is morally unacceptable to leave situations with potentially devastating consequences for large numbers of people without an identifiable bearer of responsibility. Ideally, one would be able to attribute responsibility for the flawed decisions of machines to one individual, such as the head of state or the commander-in-chief. But such a direct attribution is not feasible due to the specificities of the technology and the problem of many hands (as shown earlier). Furthermore, with respect to DSS used for resort-to-force decisions, machines are framed as supporting the decision-making process, not taking decisions like in some downstream tasks, making the AI systems less visible to the final decision maker (exceptions are autonomously operating defense systems). This might lead to decision makers being unaware of the limitations of AI-informed intelligence that is presented to them. For attributing responsibility to proxy actors, one needs to set the conditions for doing so.

I suggest an institutional response, since the responsibility gap is not an isolated incident, but reappears every time a machine is involved in decision-making processes. In this sense, the problem is inherent in every AI-induced decision. Consequently, an institutional answer would guarantee a continuous response. In the following, I argue for creating an AI oversight body that guarantees that every individual participating in the decision-making process is aware of the influence, scope and specific limitations of AI systems and thus can be potentially attributed with responsibility for their actions. It would also monitor and oversee the involvement of AI systems in the decision-making process and along the entire AI lifecycle.Footnote 14 Given the different systems and organizations involved in the decision-making process – the government, the military headquarters, the intelligence services, the corporations and the courts – an institutional response that can functionally link these different entities seems to be most appropriate. The creation of an AI oversight body is an institutional response to address the socio-technical responsibility gap by raising awareness among the participating actors for each other’s role and agenda, supervising the machine’s functioning, and attributing responsibility to individual actors.

The creation of regulatory oversight bodies is a common tool to supervise and review new regulations in a specific field. Usually, such bodies are either based in the executive or legislative branch of governments (on regulatory oversight bodies, see Wiener & Alemanno, Reference Wiener, Alemanno, Rose-Ackerman and Lindseth2010). While advisory bodies mainly offer non-binding advice and expertise, oversight bodies encompass binding and non-binding advice, such as monitoring and evaluating certain processes, conducting investigations and to issue recommendations. Oversight bodies are thus more powerful in assessing the impact of certain processes and their alignment with existing rules and norms. Since, in the present case, the oversight body would also need to ensure an assessment of AI recommendations and attribute responsibility to individual actors, the respective institution needs to be quite powerful to assert itself towards the government, the military, and the respective tech companies.

There are examples of institutions that were founded to accompany the integration of AI systems into the decision-making process, such as the US Joint Artificial Intelligence Center (JAIC), which coordinated AI-related efforts of the Department of Defense (DoD) and eventually merged with other sub-branches into the Chief Digital and Artificial Intelligence Office (CDAO). However, according to the CDAO, it does not possess the function to control AI, but rather to facilitate a smooth process from commissioning to deployment.Footnote 15 In the UK, the Defence AI Centre (DAIC) is responsible for enhancing the UK’s ability to harness AI for defense purposes, ensuring ethical and effective integration of AI technologies.Footnote 16 In France, the Agence ministérielle de l’intelligence artificielle de défense (AMIAD) focuses on the development of sovereign AI algorithms to enhance the defense capabilities. Both in the UK and France, the focus of newly founded organizational units is mainly to strengthen defense capabilities and sovereignty in the digital sphere, accompanied by developing normative guidelines. In Germany, the Ministry of Defence (MoD) founded a Network on AI within the Ministry. According to the MoD, however, the unit is still being set up, so that the specific tasks and their integration are only known to a limited extent. However, the organizational chart that displays the integration of the Network on AI shows its vertical integration into the organigram of the ministry as part of the cyber/information-technology department, which might structurally restrict the visibility, contact options, and the impact of such a network (see further elaborations below).

This overview briefly demonstrates the organizational adaptation of individual states to AI systems in decision-making processes in the military domain. It shows that, according to their self-descriptions, the organizational units are mainly assigned to oversee and guarantee a smooth integration from a technological perspective. The self-presentation does not provide concrete answers to the question of who should be held responsible for decisions by a machine. Since the integration of such an AI oversight body depends on the prevailing organizational structure, in the following, I will only discuss a very general approach to how such a body might be constituted and integrated. I base my remarks on the literature on regulatory oversight bodies and discuss the necessary changes in the organizational structure of the military and political system, the composition of an AI oversight body, and its main task.

4.2.1. Composition of an AI oversight body

The composition of an AI oversight body needs to align with the actors that are involved in the overall decision-making process on the resort to force. Since it should serve as an oversight body for decisions shaped by AI systems, the AI body would need to integrate personnel with technological, legal, military, and political expertise to ensure a functioning oversight of the involved systems and the actors therein. Such an oversight body would function as an interdisciplinary center of expertise that aims to scrutinize military AI technology from different perspectives and transfer this knowledge back to the respective organizations and actors of the different social systems. In this sense, the composition requires actors who are aware of the normative conditions and parameters that are relevant to the consideration of war (e.g., the principle of proportionality), who are able to reflect on the technological prerequisites and modes of operation (e.g., how to ensure unbiased training data, how to minimize the risk of flawed outputs), and who understand the broader decision-making structures of the military and political system (e.g., how it changes the command structure). In a nutshell, the AI oversight body would need to mirror the background of the actors involved in the decision-making process to ensure that the actors in the oversight body understand system-specific challenges and speak the same language as the actors involved in the decision-making process (Singer, Reference Singer2010).

4.2.2. Integration of an AI oversight body in the organizational structure

In contrast to examples with vertical integration, a horizontal integration of an AI oversight body is highly advisable. Cross-departmental and cross-disciplinary competencies would allow such a body to provide meaningful oversight along the AI lifecycle and any given political-military decision process. Stable contact points to every involved system and the actors within are indispensable to guarantee a broad implementation, which makes task fulfilment possible (see Section 4.2.3). Such a wide-ranging implementation of an AI oversight body into the decision-making process on the resort to force requires a change in the conventional organizational structure of Western governments (Christensen, Lægreid & Røvik, Reference Christensen, Lægreid and Røvik2020, p. 130). Figure 1 describes in a general way the decision-making process to wage war. We learned already that AI systems that fulfil upstream tasks will mainly influence the first three steps in the decision-making process. Thus, the AI oversight body would need to be integrated accordingly to be able to closely monitor the threat assessment and recommendations following from this. Furthermore, the oversight body would also need to accompany the commissioning of the AI systems and the development process to guarantee (in close coordination with the military, political, and legal systems) the alignment of the algorithms with normative and legal constraints. Thus, contact points between the oversight body and the individuals in the decision-making process should be implemented to ensure exchange and monitoring. Access to information relevant to evaluating the influence of the AI systems would need to be made accessible to the AI oversight body as a matter of policy. In sum, due to the complexity of resort-to-force decision making and the involvement of so many different systems and actors, only a horizontal integration of the oversight body can address the four social systems (in contrast to vertical control within one system) and provide meaningful risk assessment and training (Christensen et al., Reference Christensen, Lægreid and Røvik2020, p. 141).

4.2.3. Tasks of an AI oversight body

There are four main tasks of the oversight body. First, the oversight body must raise awareness among all the different actors participating in the decision-making process of the degree of involvement of AI-systems in the process, tackling the problem of “invisibility” of the AI systems. The second task is to scrutinize the recommendations of (different) AI systems at every step of the process, assessing their compliance with legal norms, political requirements, and democratic standards. Third, due to the strings that connect each system to the other (“structural coupling”) and the inter-institutional settings that are relevant to the integration of AI-based technology, the AI oversight body would provide expertise on AI involvement, such as monitoring the functionality of AI-based technology in decisions to resort to force. Fourth, such an institutional response to responsibility gaps emerging from the integration of AI systems provides the basis on which responsibility can be attributed to individuals for AI-informed decisions. By institutionally linking the four different systems and addressing the problem of limited cross-disciplinary knowledge and knowledge transfer, preconditions for meaningful responsibility attribution can be established. This requires a certain level of education of the actors involved, for example, the politicians need to understand the technological functions and limitations of the respective systems, developers need to understand the ethical imperatives in the resort to and conduct of war, integrators need to understand how the integration of the machine changes the decision-making process, etc. (Chiodo et al., Reference Chiodo, Müller and Sienknecht2024; Müller et al., Reference Müller, Chiodo and Sienknecht2025). As we have shown elsewhere (Chiodo et al., Reference Chiodo, Müller and Sienknecht2024), the education of different groups of actors is a central aspect of avoiding “harmful path dependencies” and “unknown unknowns” in the case of integrating AI-enabled systems into the decision-making process. As the relevant groups of actors – developers, integrators, users and regulators – can be roughly assigned to four different systems, namely the economic, military, political and legal systems, proxy responsibility relies on overcoming the respective disciplinary language barriers. While developers and system integrators are usually trained in computer science or mathematics, and lawyers and regulators are familiar with legal terms and phrases, politicians frequently employ a language of power and values. As a result, these groups often do not have the same perspective or understanding of problems and solutions. “Whenever we cross fields or disciplines, the paths and norms of behavior that are familiar become confusing; even the very language and words we have to use become exclusionary.” (Singer, Reference Singer2010, p. 301).

Hence, it is paramount to not only increase the knowledge about the impact of AI systems and what is ethically required, but also to devise an interdisciplinary language to address problematic situations. Only through a thorough educational program is a responsible usage of AI in the military domain even conceivable. Such responsible usage would not only limit the potential for undue harm but would also make it possible to address such harm in an ethically sustainable way. In the long term, this would require a change in the training of all actors involved, either by changing the composition of their educational programs or by adding additional compulsory courses for those working in sensitive areas, such as the military. This requires further disclosure of the applications of the technology because if this is not transparent, the developers cannot properly assess the potential ethical implications (see, e.g., the aforementioned case of “Project Maven” between the Pentagon and Google).

Figure 2 summarizes the integration of such an AI advisory body into the broader context of resort-to-force decision making. It connects the different systems involved, raises awareness of and provides expertise on the AI-involvement in the process, scrutinizes AI recommendations, and attributes responsibility to individual actors within the decision-making complex.

Figure 2. The AI oversight body in resort-to-force decision making (source: author).

Thus, the result of the integration of such an AI oversight body is that humans in the economic, political, military, and legal systems are able to be attributed with responsibility for decisions taken by a machine. For such proxy responsibility to work, the oversight body has to facilitate the autonomy of the decision makers in AI-driven environments by enhancing their knowledge.

4.3. Applicability and limitations of the concept of proxy responsibility

Proxy responsibility is a type of responsibility in which the causal agent of an action cannot be held responsible, and “second-order” or indirect responsibility relations are put in place. The concept was developed with regard to attributing responsibility in human-machine contexts (Sienknecht, Reference Sienknecht2024), but can be applied to other contexts too. Another such context is when a de facto responsible actor (qua role, constitution, law) outsources a decision to another actor, but remains normatively required to take responsibility for the decision, because the fact of outsourcing does not remove them from the responsibility relation. This is also the case in scenarios in which actors who are required to take responsibility reject their responsibility and other actors fill the vacant subject position, such as in the case of governments who exclude parts of their population (e.g., ethnic minorities), and an oppositional, political or social group steps in to fill the vacancy.Footnote 17 Furthermore, in the anticipation of far-reaching technological developments, such as the integration of AI technology in various social fields, governments tend to install expert or comparable bodies to base their decisions upon. These are the “natural” habitats for proxy responsibility. By installing actors who take responsibility for decisions that they did not fully take themselves, the incomplete responsibility relationship can be addressed via a placeholder.

These deliberations raise the question, whether the concept of proxy responsibility can really rule out situations with harmful effects on societies. The answer is no, because the AI system can still wrongly assess a situation, and politicians can still base their decisions to wage war on this wrong assessment. But the concept of proxy responsibility maintains the possibility of holding someone responsible, be it the developers who did not adequately consider legal and ethical constraints, integrators who did not properly translate technical into political language, or politicians who disregarded technological limitations. Such a case-specific assignment of responsibility would then also fall under the purview of an AI oversight body. An independent review by the body might still ascertain that all constituent parts of the AI-informed decision-making process acted responsibly, and that the harm done was an “accident.” Nevertheless, the suggested AI oversight body provides the necessary conditions for attributing responsibility.

All in all, an institutional approach to responsibility gaps has many potential advantages. It can consider the different logics of the systems involved, reflect the necessary knowledge and training of actors to enable an integrated approach, and represent an adaptation of organizational structures to the new challenges posed by the integration of AI-enabled systems. However, a substitute is never as good as the original, so establishing proxy responsibility by building such an institutional oversight body could lead to consequential problems. I will briefly discuss two of these – scapegoating and the risk of an empty signifier – and then suggest possible safeguards to avoid such pitfalls.

The first risk relates to the problem of scapegoating. The creation of an AI oversight body carries the risk that individual and collective actors involved in the decision-making process will feel relieved of responsibility and will pass the buck to the AI oversight body. This is a problem that could arise as a response to the human tendency to use AI-enabled tools as scapegoats for anything that goes wrong (Erskine, Reference Erskine2024b). The scapegoating of the AI oversight body could then follow the same logic, not solving the problem but simply shifting it to another scapegoat. Therefore, an AI oversight body implemented across the social systems involved needs to be very specific about which guidelines, competencies, and rules each actor and organization must follow and what their responsibilities are. Failure to do so risks the possibility of scapegoating (Erskine, Reference Erskine2024b), “agency laundering” (Rubel, Castro & Pham, Reference Rubel, Castro and Pham2021) or abdicating responsibility by claiming that one was only part of a larger process.

The second risk is the construction of an empty signifier. In the case of problematic or challenging situations, a routinized and standardized response is to set up an institution to come up with possible solutions to a problem. However, the proposed institutional unit runs the risk of becoming a paper tiger if it is not properly empowered and integrated into existing organizational structures. Ethics committees, for example, often seem to be such an institutionalized response and attempt at legitimization in morally difficult situations (Bogner, Reference Bogner, Grunwald and Hillerbrand2021; Littoz-Monnet, Reference Littoz-Monnet2020). They are, for example, frequently established to increase ethical reflection on the development process of new weapons technologies. However, the composition of such working groups or committees is already political; that is, depending on the experts invited to participate in such a committee, a certain outcome or tendency is to be expected. So, how can we avoid the AI oversight body becoming an empty shell, a routinized institutional response to an organizational problem? The adaptation of organizational decision-making structures is crucial in this respect. Such an AI oversight body would only be effective if it had clearly specified competences, had access to all the information necessary to oversee AI-induced decisions, and was structurally integrated into the decision-making process. This would render it a place where decisions on the responsible integration of AI systems are taken and not simply a discussion circle providing a fig leaf for unpopular AI-informed decisions.

In sum, proxy responsibility seeks to address situations in which either a synthetic agent makes decisions or a responsible actor does not take responsibility for its actions, leaving us with an incomplete responsibility relation. To address this responsibility gap, a third actor (or different actors) must substitute for the vacant responsibility subject, thus taking proxy responsibility for the decisions of this subject. While one can never fully close the responsibility gap, one can address and contain it by implementing proxy responsibility relations among the individuals involved.

5. Concluding remarks

This article is both conceptual, in that it theorizes the concept of proxy responsibility, which serves as an approach to address responsibility gaps in human-machine contexts, and practical, in that it discusses the establishment of an AI oversight body as an institutional response to the aforementioned responsibility gaps. The concept of proxy responsibility differs from other approaches, such as distributed or collective responsibility, in that it focuses on establishing the conditions for attributing responsibility. It does so with a specific focus on the distinction between resort-to-force and use-of-force decision making, and the respective responsibility gaps. Proxy responsibility can only be attributed if certain preconditions are met, such as knowledge, autonomy, and intentionality. A lack of understanding of the impact of AI systems on the decision-making process makes establishing proxy responsibility difficult. Developers are not accustomed to considering the ethical issues relating to the challenging decisions involved in waging war, while politicians have limited technical knowledge of how AI systems function. Integrating such systems into the military also necessitates an in-depth understanding of both the technological and the ethical and political constraints. However, to attribute proxy responsibility, those involved need to understand the technology, the ethical constraints and the implications of the integration process. The suggested AI oversight body is responsible for establishing these preconditions. The body’s main tasks would therefore be to raise awareness of AI integration, provide expertise on AI involvement, scrutinize AI recommendations, and attribute proxy responsibility to potential actors (building on already existing responsibility relations, such as political responsibility and liability qua the different roles). Unlike other approaches that aim to address the socio-technical responsibility gap, this article focuses on the preconditions for attributing responsibility. It pays less attention to detailing the degree of responsibility that specific groups and individuals may bear. However, future research would benefit from reflecting on how to integrate existing theoretical approaches to strengthen the responsibility framework surrounding integrated AI systems. This would include providing more detail on how the AI oversight body attributes responsibility within the context of its institutional characteristics, such as its mandate, competencies and integration within broader decision-making structures.

However, as previously discussed, the responsibility gap cannot be closed due to the opacity of AI systems. No matter how many proxy relations, technical solutions or practical answers we develop to attribute responsibility, the responsibility gap will always persist to some extent. Therefore, integrating AI systems that have such a profound impact on decision-making structures will always lead to a situation in which responsibility cannot be clearly attributed to human actors. The risk of machines causing harm cannot be eliminated, only contained. One way to do so is by setting the conditions under which individuals like the head of state can take proxy responsibility for the decisions of a machine, or under which a developer understands the scope and scale of a task and its ethical implications, so that they can take proxy responsibility for faults in the programming, or under which legal advisors accept their proxy responsibility for rightfully assessing the compliance with existing norms, but also for developing new guidelines to mitigate further risks. Moreover, to guarantee that the AI integration works from a democratic perspective, the implications of such an integration must be made public and be open to public debate. In particular, it must be avoided to simply accept the military’s narrative that ethical considerations and guidelines will impede the development, integration, and deployment of AI technology and thus could hinder national security and defense capabilities. Since we cannot avoid the infiltration of society by AI-based technology, which will improve life and achieve positive outcomes in many areas, we must be aware of the policy fields that are morally contentious by default and will become even more so through the integration of AI systems.

Moreover, in future research, it would be worthwhile to compare existing regulatory bodies that aim to hedge the influence of AI systems in the military domain and identify further connections beyond the national context. These institutions play a crucial role in safeguarding public interests by preventing erroneous decisions and enabling the attribution of responsibility. As international regulation develops further, monitoring adherence to these regulations is as important as providing input to promote the responsible use of AI. However, the issue of what happens if actors do not follow recommendations or refuse to accept responsibility attributed by the oversight body has not yet been discussed. Incorporating research from the field of oversight bodies would help to detail required enforcement mechanisms, such as fines for non-compliance, investigations and assessments of AI system functionality.

Funding statement

I declare that no funding was received for the publication of the article.

Competing interests

I declare no competing interests.

Mitja Sienknecht is a Postdoctoral Researcher at the European New School of Digital Studies/European University Viadrina Frankfurt(Oder). Previously, she held positions at Bielefeld University, Berlin Social Science Center (WZB), and the University of Münster. Her research focuses on the transformation of war through AI technology, questions of responsibility in World Politics, and inter-and intraorganizational relations in security studies. She has published her work in edited volumes and journals such as International Theory, Global Constitutionalism, and the Australian Journal on International Affairs. Her research is based on the intersection of International Relations (IR), sociology, and international political theory.