Cities of the imagination and cities of memory are close cousins. I live in a small village in County Meath, which in normal times is about a twenty-kilometre commute to my office in Trinity College, in the city centre. As I began to write this book in April 2020, exiled from the city by the first waves of the COVID-19 pandemic, I began to experience particularly vivid memories of Dublin as I had first encountered it thirty-five years earlier. ‘Your first day in Dublin is always your worst,’ wrote the American poet John Berryman, when he arrived in 1966.1 It was otherwise for me when I first landed in the city in 1985 as a postgraduate student. In those initial few minutes in the city, I had a sense that there was something familiar about the address I gave to the taxi-driver on my way in from the airport: 15 Westland Row. At first I thought this was just the comforting thought that somewhere new already felt familiar. Then I remembered that I had been reading Richard Ellmann’s biography of Oscar Wilde on the plane, where he mentions the house in which Wilde had been born – 21 Westland Row, only a few doors down from where I would be living.

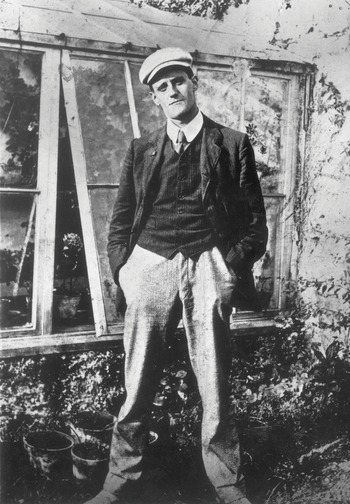

After putting my bags in my room on that first day, I set out on jet-lagged search for aspirin. The first likely source was at the end of Westland Row, on Lincoln Place: Sweny’s Chemist Shop. This, it turned out, was the setting for the ‘Lotus Eaters’ episode of James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922), the shop in which Leopold Bloom buys his wife, Molly, a bar of lemon soap. ‘Sweny’s in Lincoln Place. […] He waited by the counter; inhaling the keen reek of drugs, the dusty dry smell of sponges and loofahs.’2 From the doorway of Sweny’s I could see the brick building that had been Finn’s Hotel, where Nora Barnacle had been working when Joyce first met her on 16 June 1904, the day on which they met and which he memorializes in Ulysses.

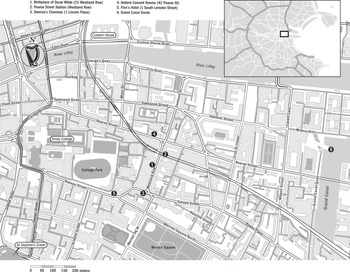

This apparently innocuous stretch of street – Westland Row – may not look particularly rich in literary associations; however, it features in works by Joyce, Beckett, Thomas Kinsella, and others; and the door of the house in which Oscar Wilde had been born, at 21 Westland Row, is just visible to the left. Photo from Fergus O’Connor Collection.

Oscar Wilde (1854–1900). Although he would later reinvent himself in the context of a parodic version of fashionable London, Wilde was born on the edge of the Trinity campus, at 21 Westland Row; the family later moved around the corner, to 1 Merrion Square, and Wilde studied at Trinity.

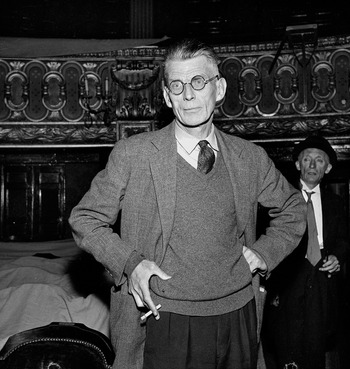

On my way back down Westland Row that morning, I decided to continue on past my building, conscious now that I was following Bloom’s fictional footsteps, past the Westland Row train station where the tracks cross above the road, and where ‘the engine departing hammered slowly overhead’,3 as the poet Thomas Kinsella puts it in a poem set on the street. The end of Westland Row brought me to Pearse Street, where I encountered Belacqua, the fictional protagonist of Samuel Beckett’s More Pricks Than Kicks (1934), who has a distaste for the parallel Nassau Street (‘beset at this hour with poets and peasants and politicians’). Instead, he prefers ‘long straight Pearse Street’ with ‘its vast Barrack of Glencullen granite [the police station], its home of tragedy restored and enlarged [the Queen’s theatre], its coal merchants and Florentine Fire Brigade Station, its two Cervi saloons, ice-cream and fried fish, its dairies, garages and monumental sculptors [where Patrick Pearse worked], and implicit behind the whole length of its southern frontage the College.’4

James Joyce (1882–1941), more than any other single writer, has shaped the literary imagining of Dublin. ‘If the city one day suddenly disappeared from the earth it could be reconstructed out of my book [Ulysses],’ he once told his friend Frank Budgen. Pictured here in the rear garden of his friend C. P. Curran’s house, at 6 Cumberland Place, Dublin, in 1904.

Continuing my walk that first morning, across Pearse Street I noticed a building of diminished glamour, which turned out to have been the Antient Concert Rooms. This was where the Irish Literary Theatre – the forerunner of the Abbey Theatre, founded by W. B. Yeats, Lady Gregory, and Edward Martyn – staged its first production, The Countess Cathleen, on 8 May 1899. Inspired by what happened on Pearse Street on that night, Yeats wrote: ‘The drama has need of cities that it may find men in sufficient numbers, and cities destroy the emotions to which it appeals, and therefore the days of the drama are brief and come but seldom.’5 Yeats’s comments on ‘the days of the drama’ have stuck with me over the years, and are not just limited to the theatre. As much as writers need somewhere quiet to write, it is the rare writer who does not also need the presence of other people – particularly other writers – and many thrive on being able to immerse themselves in the sensorium of the city, on living in a place rich with the lives of others. Precisely why Dublin might lend itself to this delicate balance of needs was something Elizabeth Bowen identified with her usual precision in 1936: ‘Dublin’s grandness, as a capital city, is anti-romantic,’ she wrote. ‘Her interest lies in her contrasts, in the expression she gives to successive different ideas of living.’ Bowen went on to make an observation that I have found not only to be true, but to be increasingly true the better I have come to know Dublin. ‘Emotional memory, here, has so much power that the past and present seem to be lived simultaneously.’6

Samuel Beckett (1906–1989) lived much of his life in Paris, and wrote some of his major works in French. However, he was born in Dublin, studied at Trinity College, and his earliest works are very much woven into the fabric of the city, while later works return to it in memory.

Going back to that morning in 1985, I realize now that before I had even had a decent sleep, Dublin as a writers’ city was taking shape for me. Many years later, when I came across Colm Toíbín’s 2018 book on the fathers of Wilde, Yeats, and Joyce, Mad, Bad, Dangerous to Know, where he too writes about recognizing Westland Row’s density of literary associations, I was not only thrown back to my own first hour in Dublin, but also felt a further accumulation of layers of association, so that my mental map now includes not just Yeats, Joyce, Wilde, and Beckett, but also Tóibín himself, and his memory of the street in the 1970s. Reading Tóibín’s book during those strange displaced months of the spring of 2020, my own memories, the books I had read, and the books about books, all assumed a vividness that I might have missed had the actual city been present to insist on its noisy reality.

Over time, of course, that reality has altered. Sweny’s stopped selling aspirin and filling prescriptions in 2009, and has since reinvented itself as a used bookstore and a place for literary readings. The Antient Concert Rooms looked like it was going to be demolished in the great property scramble of the late 1990s, but the façade was preserved, and the building has since been converted into hot-desk office space for new start-ups. And the house where Oscar Wilde was born is now part of the Trinity campus. It is, in fact, the building in which my office is located, in what is very likely the actual room in which Lady Jane Wilde gave birth. ‘Cityful passing away, other cityful coming,’ muses Leopold Bloom at one point in Ulysses; ‘passing away too: other coming on, passing on. Houses, lines of houses, streets; miles of pavements, piledup bricks, stones. Changing hands.’7

There was also, however, something about the sheer strangeness of the images of an empty city that emerged from the pandemic lockdowns in 2020 and into 20201 that brought back Dublin as I had first seen it. In the Dublin of the 1980s, almost all the shops were closed on Sundays. Even the pubs closed for a period in the afternoon for what was known as ‘holy hour’. As a result, fewer buses ran, fewer people were around, and the streets had a sense of in-drawn breath, of waiting. ‘A man should clear a space for himself,’ writes the poet Brendan Kennelly:

For me, those Sundays were a time when the hidden fabric of Dublin showed itself, and I would walk the derelict cobbles and empty quays around the Grand Canal Docks for hours, absorbing the sense of past lives lived.

Today, that area around the Grand Canal Basin where I used to walk is known as the Silicon Docks. An entirely new streetscape has emerged, and companies such as Google, Twitter, and Facebook are now based there. This is a Dublin that never existed before, mirrored across the River Liffey by the larger financial services district, zones of steel, glass, and fibre-optic cabling, in which business is not simply multinational in an older sense. It is a city within a city in which global connectivity itself is the main business. If it were possible to perform an MRI scan of twenty-first-century Dublin, showing flows of data, the docklands would radiate enough light to convince you not only that this was the new city centre but that it was a principal European data capital.

And yet, there is paradoxically a different quiet here now. This is not the quiet of dereliction of the 1980s, but the quiet of a place with no memories – or at least with no literary memories. If the writers and fictional characters who populated Westland Row chattered incessantly in my ear, this new city that has grown up in the midst of the old one – while often architecturally impressive – is strangely silent. The philosopher Edward Casey has written about what he calls ‘place-thinning’, the sense that ‘certain habitual patterns of relating to places have become attenuated to the point of disappearing altogether’.9 To walk through Dublin’s Silicon Docks today is to understand what he means; the air is somehow both brighter and thinner here than it is elsewhere in the city. This is both an unwritten city and – paradoxically – one that is denser with information than any part of Dublin has ever been before. It is a place where it only takes a small effort of imagination to see the air buzzing with the constant feed of images and data that distract us from where we are. It not only feels like elsewhere; it is home to the industries that allow our attention to be where we are not. In the literary city it is otherwise: in the literary city, we are always – insistently – present.

There is a sense, then, in which this book is a double effort of recovery. At the time it was being written, in a kind of exile, immersing myself in the literature of Dublin became a means by which the words of Dublin’s writers could become surrogates for the missing city. But this book is an act of recovery in another sense as well, stretching beyond the pandemic in which it was written. My experience of that first morning on Westland Row is constantly growing and changing: a line from a poem here, a reference there, an unexpected address from a novel. Piece by piece, over the years I have been assembling a never-to-be-completed mosaic of Dublin as a writer’s city. And as a new piece of the mosaic falls into place, another corner of the city comes alive for me, and a previously innocuous building or street corner shines out with a new significance. Little by little, my sense of place becomes a bit thicker.

The design of this book is an attempt to impose some kind of pattern on that larger mosaic by dividing the city into interlocking (and sometimes overlapping) zones of memory. Those associations are, to some extent, necessarily partial and impressionistic. For instance, it is well beyond a book of this scope to do more than nod in the direction of Dublin’s Irish-language literature, or the wealth of children’s literature set in the city. With this in mind, after an initial historical chapter to sketch an outline of the city’s history, the book moves chapter by chapter outwards from the city centre through a series of zones of varying sizes. These do not necessarily align with electoral wards or parishes and are not be found on standard maps. And yet, when you are in the city, these are areas in which you sense some definitional common quality – maybe it is the scale of the streets, or the smell of the air – that is palpable even if it escapes easy definition.

These distinctive emotional atmospheres in different parts of the city have produced writing that over the years has been in dialogue with itself – the working through of Bowen’s ‘emotional memory’ if you like. It is as if Dublin’s writers have been collectively reaching towards the elusive quality that makes the area around Huband Bridge over the Grand Canal in the south city, for instance, utterly different than that around Mayor Street Bridge over the Royal Canal in the north city, only a twenty-minute walk away. Dividing up a city in this way is not necessarily a tidy business. The zones are by no means absolute, the divisions are more pragmatic than dogmatic, and they vary considerably in territory, ranging from what is effectively the single city block occupied by Trinity College to the twenty-five-kilometre sweep from the north docks to Finglas. They also vary in historical depth, some resting on pre-Viking pathways, while others were fields within living memory. In the same way, the writers, novels, poems, and plays that I have used here to trace this provisional map are only one possible selection from the vast library of Dublin’s literature. There are many, many other ways to tell this story, and I expect that most readers will have suggestions for a favourite poem or novel that could or should have been included. In fact, I hope that they will – for those are the kinds of continuous conversations that a living city of literature has with itself.

In the end, perhaps the best way to understand Dublin: A Writer’s City is to imagine its opposite: Dublin without its literature. Here I see once again the images of Dublin’s Grafton Street during the worst of the pandemic, shops boarded up, emptied of people, with grass growing between the paving stones. This was the city that Derek Mahon evokes in one of his final poems before his death in October 2020, ‘A Fox in Grafton Street’:

This, then, is a book born out of what Mahon calls later in the poem the ‘shocked euphoria’ of the ‘enforced parenthesis’10 of the pandemic. It is an attempt to repopulate a city from a collective imagination, acknowledging that the citizenry of Dublin includes not just the living and the dead, but also the remembered and the imagined.

‘Weed-grown cobblestones / deserted by the pedestrian population,’ wrote Derek Mahon (1941–2020) in a late poem about a deserted Grafton Street (pictured here). When the pandemic that began in 2020 emptied the streets of the city, the extent to which Dublin owes its character to its people became apparent.