In the wake of the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, a group of Black legislators felt empowered to create a political caucus in Congress to extend the fight for equality in the streets into the corridors of government. This small group of nine Black members of Congress began to meet to advocate on behalf of Black people and to help those among their ranks feel less isolated in an overwhelmingly White political institution (Barnett Reference Barnett1975; Stanberry Reference Stanberry2022). This group grew as the 1965 Voting Rights Act provided the opportunity for more Black people to be elected to Congress. In 1971, this informal group established the Congressional Black Caucus (CBC).

Since its inception over fifty years ago, the Congressional Black Caucus has grown in numbers and in stature. The CBC’s membership has increased over 400% from 13 members in 1971 to 62 members in 2025. The CBC now makes up over ten percent of Congress and serves the critical function of enhancing Black political representation. For instance, the CBC has played an important role in shifting the Democratic Party’s priorities to reflect the interest of Black people through the publishing of an alternative Congressional budget (Griffin and Newman Reference Griffin and Newman2019; King-Meadows Reference King-Meadows2001; Minta Reference Minta2021). The CBC has also been a key force around creating Black commemorative holidays such as Martin Luther King Jr. Day and Juneteenth (Polletta Reference Polletta1998). Recently, the CBC has been on the forefront of fighting for police reform in the era of Black Lives Matter (Hayden Reference Hayden2021; Peay and Rackey Reference Peay and Rackey2021). The size and the scope of the Congressional Black Caucus not only makes it an important player in the federal government, but an important driver of Black political representation.

While much has been written about the CBC’s role in shaping legislation through protests and coalition building (Minta Reference Minta2021; Nelson Reference Nelson2022; Pinney and Serra Reference Pinney and Serra2002; Whitby Reference Whitby2007), less has been written about how Black people view this important institution in government. Today, where a growing portion of non-BlackFootnote 1 Democrats express racially liberal values and Black Democrats express frustration with the lack of policy responsiveness, it is not known whether Black people support their racial affinity group in Congress and/or whether they support it more than non-Black people. Similarly, less is known about whether some Black people view the CBC more favorably than others. By answering these questions, we provide an important set of contributions to legislative studies and racial and ethnic politics by exploring how racial affinity groups like the CBC are viewed by those who they work to represent. Moreover, we identify whether some intersecting identities in the Black community feel more positive about the CBC.

In this study, we engage in a deep dive into Black Americans’ views of the CBC. To accomplish this goal, we begin by arguing that Black people should be the CBC’s strongest supporters because of the centrality of race among Black people and the history of Black lawmakers working to advance their interest in government. We then explore where cleavages may lie among Black people in their support for the CBC with a focus on age. We suspect that Black youth’s lower levels of linked fate and greater skepticism in elected officials should lead younger generations of Black Americans to see less value in the CBC than older Black people. This will likely manifest itself in a gap in approval for the CBC among younger and older Black Americans.

Understanding the role of age in shaping public support for the CBC is crucial for assessing how Black political representation is valued across generations. As the political priorities and identities of younger Black Americans increasingly diverge from those of older cohorts, examining support for the CBC by age helps illuminate broader shifts in how Black communities engage with traditional institutions of racial advocacy that emerged from the Civil Rights Movement. This generational lens offers insight into the future relevance of the CBC and raises important questions about how Black political leadership can adapt to the evolving values and political demands within its constituency. It is also possible that generational differences in support for the CBC may reflect broader divides in trust in electoral politics and in the Democratic Party as a vehicle for advancing racial justice.

Moreover, Black youth are a particularly special group in the current political landscape. Black youth have been integral to ongoing efforts for racial justice including the development and maintenance of the Black Lives Matter movement (e.g. Freelon, McIlwain, and Clark 2016). There is also some evidence that young Black people voted for Donald Trump at substantially higher rates than their older counterparts (though they still broke heavily for Kamala Harris).Footnote 2 Understanding the generational divide in support for an institution like the CBC can shed light on the political preferences of this group.

To test our hypotheses, we use the 2020 Collaborative Multiracial Post-Election Survey (CMPS) which is unique in that it not only includes a large number of Black respondents (∼5000) but it also asks them about their views of the Congressional Black Caucus. Our analysis confirms our expectations. Namely, Black people are the most supportive of the CBC. We also find a significant age gap among Black people in their support for the affinity group. Younger Black people are significantly and substantially less supportive of the CBC in comparison to their older co-racial counterparts. In fact, the disparities in support among the youngest and oldest Black respondents is greater than the differences between Black and White people in our analysis.

We further explore the causes of this intergenerational rift by showing that younger Black people’s lower levels of support for the organization are in part tied to their lower levels of linked fate and their perception that elected officials do not work to advance their interest in government. We conclude by discussing the implications of our results for the relationship between race and congressional affinity groups in a period where there is a growing intergenerational public opinion gap between Black people socialized before and after the Civil Rights Movement.

Who Supports the Congressional Black Caucus?

The CBC’s mission is to be a voice for Black politics in Congress (Minta Reference Minta2021; Nelson Reference Nelson2022; Tate Reference Tate2020). We anticipate that the CBC’s actions and political stances will make it so that Black voters will be the strongest proponents of the organization. Research indicates that Black people express greater support for racially progressive policies (Arora Reference Arora2025; Jones Reference Jones2023). Additionally, studies show that there has been an increase in racially progressive attitudes among Black communities following the emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement (Stout Reference Stout2020). This is true for less polarizing issues, such as voting rights and police reform, and policies which are divisive, such as reparations and affirmative action (Garcia, Stout, and Tate Reference Garcia, Stout and Tate2026). Beyond racial issues, Black people tend to be more progressive on a host of topics which disproportionately affect their racial group. For example, numerous public opinion polls show that Black people are more supportive of strengthening the social safety net, increasing the minimum wage, and increasing taxes on the wealthy.Footnote 3

The Congressional Black Caucus is more aligned with Black people’s political interests than Congress as a whole and even the Democratic Party (Griffin and Newman Reference Griffin and Newman2019, Minta Reference Minta2021, Stanberry Reference Stanberry2022). One of the founding and continuing principles of the CBC is to be a voice for Black people in government. As a result, the caucus works hard to mirror the political preferences of Black people in the country in a dynamic fashion. Some even argue that the growing moderation of Black leaders and the CBC is associated with greater moderation among Black people in the population (Tate Reference Tate2010). The purposive position-taking of the CBC to mirror the preferences of people who share their race should lead Black people to be more supportive of the Congressional Black Caucus.

The CBC’s willingness to take a stand on highly controversial issues like reparations and affirmative action likely sets them apart from even the most progressive members of Congress. Policies perceived as explicitly benefiting Black Americans over other racial groups tend to receive the least support from White people and other people of color (Parker and Barreto Reference Parker and Barreto2014; Tesler Reference Tesler2020). While proponents argue these measures are necessary to address systemic racial inequalities, some non-Black Americans view them as unfairly advantaging Black people at their expense (Gilens Reference Gilens2001; Kuklinski et al. Reference Kuklinski1997). As a result, organizations like the CBC, which advocate for these policies, may be viewed more negatively by non-Black people. In contrast, Black voters may appreciate the CBC’s commitment to addressing racial inequality, even when such policies face broader public opposition. This dynamic could contribute to a divide in support for the CBC between Black and non-Black Americans.

While centered on U.S. politics, the Congressional Black Caucus also works to advance the interests of Black people globally and for African immigrants in the United States. The CBC was one of the earliest and loudest advocates for divesting in South Africa (Demessie and Henderson Reference Demessie and Henderson2021; Tillery Reference Tillery2006). They also were strong advocates for expanding health coverage and addressing the HIV/AIDS epidemic on the continent in the early 2000’s (Rockeymoore 2000). Domestically, the CBC has been strong advocates for the broader Black diaspora. One of the CBC’s task forces is the Immigration Reform Working Group. In their statement about this group, CBC leadership speaks about needing to represent the interests of Black immigrants.Footnote 4 The CBC’s work to advance the interest of the Black diaspora domestically and internationally may further endear the group to a wide variety of Black people in the United States.

Beyond the actions taken by the CBC, their presence as a group of Black legislators may lead Black people to feel more positively about the organization. Even if a person did not know the policy portfolio of the CBC, the organization’s name should provide a shortcut for people to assess their mission. Consistent with this idea, numerous studies show that people make inferences about an organization’s mission based on very little information about the group (Kulkinski and Quirk Reference Kuklinski, Quirk, Lupia, McCubbins and Popkin2000; Lau and Redlawsk Reference Lau and Redlawsk2001). In this case, Black people’s stronger support for issues which are explicitly or implicitly tied to their race should lead them to be more supportive of an organization which has their racial group in the title.

Additionally, the CBC’s name provides clues to the public that its membership is made up of Black leaders. In general, people are more supportive of elected officials who share their racial identity (Casellas and Wallace Reference Casellas and Wallace2015). There are numerous reasons for this preference. First, it is assumed, and often correctly, that co-racial elected officials will be the most supportive of individuals who share their identity (Casellas and Wallace Reference Casellas and Wallace2015; Hayes and Hibbing Reference Hayes and Hibbing2017). In an experiment, Williams (Reference Williams2017) showed that when presented with information about the same candidate with a different racial cue, Black and White respondents viewed the Black candidate as being better at representing Black political interests. Additionally, Stout (Reference Stout2018) demonstrated that Black people view Black elected officials as being more empathetic to their position than others.

Beyond Black Americans, there is reason to believe that Latinos and Asian Americans may also have positive views of the CBC. Though confronted with differing forms of discrimination, Latinos,Footnote 5 Asian Americans and Black Americans may identify a commonality with one another rooted in their shared experiences of marginalization. This may be especially true when considering legislators in the U.S. Congress, an institution that is largely white and has a well-documented history of institutionalized marginalization (Hawkesworth Reference Hawkesworth2003). As a result, when evaluating legislators, though they may more strongly favor co-ethnic/racial legislators, they may also favor those legislators of color who have likely had similar experiences.

In Congress, Tyson (Reference Tyson2016) shows that linked political fate brings different identity-based caucuses together in pursuit of common policy interests via the Tri-Caucus. Legislators of color and those representing racial and ethnic minorities frequently find themselves as perpetual minorities within minority-run institutions. By joining forces on a common interest, the Congressional Black Caucus, Congressional Asian American Caucus, and Congressional Hispanic Caucus enhance their legislative power. For Latinos and Asian Americans in the electorate, seeing the CBC work alongside their racially/ethnically based caucus may further bolster their support for the CBC.

In contrast, the same factors which lead Black people to be more supportive of the CBC may alienate some non-Black people. For example, White voters with high levels of racial resentment are the most likely to punish candidates who they view as advancing Black politics (Arora Reference Arora2025; Tesler Reference Tesler2020). Given that Black candidates are stereotyped as favoring Black people (Piston Reference Piston2010; Williams Reference Williams2017), some White voters may view an organization made up of Black leaders negatively. Based on this research, our first hypothesis states…

H1: Black people will be the most supportive of the Congressional Black Caucus

Are Some Groups of Black People More Supportive of the Congressional Black Caucus Than Others?

While we anticipate that Black people should be more supportive of the CBC, we expect there to be significant variation within the Black community in their approval of the organization. One major cleavage among Black people is age (Cohen Reference Cohen2010; Gillespie Reference Gillespie2009; Watts Smith et al Reference Smith, Bunyasi and Carrera Smith2019). We anticipate that younger Black people will be significantly less supportive of the CBC than their older counterparts.

Younger Black people tend to have significantly lower levels of linked fate compared to older Black people (Watts Smith et al Reference Smith, Bunyasi and Carrera Smith2019). Black people with higher levels of linked fate believe that what happens to their racial group will have a large impact on their own life chances. When Black people perceive that their own future is heavily tied to the fate of the Black community, they are more likely to support groups which focus on Black centered advocacy (Tate Reference Tate1994). As a result, Black people with high levels of linked fate should display a stronger preference for the CBC because of their work to advance Black political interests.

Our own analysis of the 2020 CMPS is congruent with these studies. Young Black people are much less likely to say that their race is extremely or very important to their identity than their older co-racial counterparts. Similarly, our analysis of the linked fate measure shows a particularly large age difference–young Black people are much less likely to believe that what happens to Black people will impact their own lives. Indeed, 19–39 year-olds are twice as likely to believe that what happens to Black people will not impact their lives at all and 19 percentage points less likely to believe that it will impact their lives “a huge amount” or “a lot” relative to 60 + year-old Black people.

Why do younger Black people have lower levels of linked fate? Watts-Smith et al. (Reference Smith, Bunyasi and Carrera Smith2019) argue that Black people who were politically socialized in the era of the Civil Rights movement often view race as being an important part of their identity. While many racial barriers are still present, older Black people have first-hand experiences with de jure segregation and a more explicitly anti-Black political system. In contrast, Black people born after the 1960s Civil Rights era may perceive race as a less decisive factor in determining their life outcomes (Gillespie Reference Gillespie2009).

The Civil Rights Movement occurred over half a century ago. As time passes, the number of surviving members naturally decreases. With each passing year, the cultural and historical context of that era becomes more distant, diminishing the relevance of that history. These narratives served as a source of inspiration and strengthened group cohesion (Board et al Reference Board2020; DeSante and Watts Smith Reference DeSante and Smith2020). As direct connections to these narratives fade, it is likely that those farther away from these experiences may display lower levels of racial linked fate. Consequently, younger Black individuals may be less inclined to consider racial advocacy as a primary factor when evaluating government-related organizations.

Additionally, older Black legislators championed racial issues in their political outreach (Gillespie Reference Gillespie2009; Tate 2020). These Black leaders, many of whom had backgrounds in the Civil Rights Movement, set the tone and agenda for Black America (Gillespie Reference Gillespie2009; Tate 2020). This agenda was largely centered on turning the successes of the Civil Rights Movement into tangible improvements for Black people in society. This agenda would echo the significance of race to individuals being socialized in this period and may increase their linked fate and views that Black representation matters.

In contrast, Black people who were born a generation after the Civil Rights movement were socialized in a period where political leaders, and even co-racial politicians, emphasized color blindness (Orey Reference Orey2006; Orey and Ricks Reference Orey and Ricks2017; Perry Reference Perry1991; Stout Reference Stout2015). Tate (Reference Tate2010) argues that Black politicians’ movement into mainstream politics led Black people in the population to take more moderate positions on these issues as well. As race receded from the forefront, so too may have individuals’ belief in racial linked fate.

In addition to their lower levels of linked fate, younger Black people tend to be more skeptical of politicians in general (Lawless and Fox Reference Lawless and Logan Fox2015). According to our analysis of the 2020 CMPS, younger Black people are less likely to believe that politicians look out for their concerns and are more skeptical that their representative in the U.S. House does a very good job or good job keeping in touch with people in their district than older Black people. This is true even when the elected official is Black. This disillusionment in politicians and elected officials has been documented in other studies as well (Chanley, Rudolph, and Rahn Reference Chanley, Rudolph and Rahn2000; Jones Reference Jones2015). A lack of trust in politicians may result in younger Black people expressing reduced support for organizations made up of elected officials.

Beyond lower levels of trust in politicians in general, young Black people may also be less likely to prioritize co-racial representation. Older Black people may be more likely to remember a time when Black people were excluded from government (Tate Reference Tate2010). They might view representation itself as a significant achievement and feel less inclined to scrutinize Black elected officials for their policies (Harris Reference Harris2014). Over time, as the presence of Black elected officials has become more common, young Black people have become more critical (Cose Reference Cose2011). For older Black people, co-racial elected officials often symbolize progress, and criticism may feel counterproductive to maintaining the momentum in achieving equality and representation. Younger Black people may place a lower premium on descriptive representation given that many were socialized in a period with Black Mayors, Governors, and even a Black President.

How Government Actions/Inaction Can Diminish Support for Black Political Institutions Among Young Black People

Scholarship has looked at how interactions with government and political institutions can shape people’s attitudes. For instance, in highly policed areas, many Black Americans’ primary interactions with the state occur via the criminal justice system. As a product of these interactions, Black Americans in these areas engage in “strategic retreat from engagement with the state” (Weaver et al. Reference Weaver, Prowse and Piston2020). Considering that younger and poorer Blacks tend to disproportionately come into contact with the carceral state, their negative perception of state institutions could impact their perceptions of the CBC. Similarly, Nuamah (Reference Nuamah2021) shows that Black people impacted by school closures in Chicago, produced lower levels of trust towards policy makers and politics more broadly. Taken together, this line of work demonstrates that one’s intersectional identity can shape their experiences with the government, which in turn, can produce distinct relationships with the government and political leaders.

Intersectional analyses provide further reason to believe that younger Blacks may have lower levels of favorability towards the CBC. This line of research asserts that overlapping identities produce unique political experiences within marginalized communities, which can complicate the relationship between descriptive representation and the politically empowering and substantive benefits it can provide. For instance, policies long defined as Black interest issues, like affirmative action, school choice, and minority small business loans, tend to benefit advantaged subgroups, like African Americans of higher socioeconomic status and with greater education levels (Strolovitch Reference Strolovitch2008). Prioritizing issues like this is not an accident. In fact, scholars have shown that Black political leaders (Cohen Reference Cohen1999, Reference Cohen2010; Smith Reference Smith1996; Stephens-Dougan Reference Stephens-Dougan2021) and advocacy organizations (Strolovitch 2008) prioritize advantaged subgroups over disadvantaged subgroups, like LGBTQ individuals, the poor, and those involved in the criminal justice system.

Cohen (Reference Cohen1999) states that Black political leaders, seeking legitimacy, practice secondary marginalization by distancing themselves and other respected community members from those who defy dominant norms. Rather than advocating for those most stigmatized and disadvantaged Black Americans, through secondary marginalization Black political leaders further marginalize these individuals by reinforcing dominant narratives and stereotypes, often blaming them for their own problems. Due to the disproportionate prevalence of poverty, identification as queer, or prior interactions with the criminal justice system among Black youth, they frequently experience secondary marginalization (Cohen Reference Cohen2010).

Cohen (Reference Cohen2010) highlights that Black youth’s political interests are rarely met, even among Black political elites. Moreover, Cohen (Reference Cohen2010) outlines many instances where older Black elites publicly blame the deficits of younger Black Americans for the plight they face (see also Stephens-Dougan Reference Stephens-Dougan2021). These experiences have shaped how they engage in politics, with less of a focus on traditional avenues of engagement. Considering that the CBC, largely filled with older Black leaders whose focus on working with the government runs counter to how Black youth channel their engagement with politics (Dalton Reference Dalton2018), may help us better understand why younger Blacks view the CBC less favorably.

Based on this research, our hypothesis states…

H2: Older Black people will be more supportive of the Congressional Black Caucus because of their higher levels of linked fate and their stronger belief that Black elected officials will work on their behalf.

Data

To examine the link between race, age, and support for the Congressional Black Caucus, we analyze the 2020 Collaborative Multi-Racial Post-Election Survey (CMPS) (Frasure-Yokley et al. Reference Frasure-Yokley2020). The CMPS is focused on getting a large number of respondents from hard-to-reach populations, such as communities of color, and was collected in multiple languages. The 2020 CMPS was collected over a 4-month period from April 2021 to August 2021. The survey collected data from 17,556 respondents including a sample of 4,843 Black respondents.

We commissioned a question on the 2020 CMPS which asked respondents “How much do you approve of the performance of the Congressional Black Caucus”. This variable was measured on a scale which ranged from 1—“Strongly Disapprove” to 5—“Strongly Approve.” This variable serves as our dependent variable. Given that we expect that not everyone will be aware of the CBC, we also gave respondents the option to select “Never Heard of the Caucus.”Footnote 6 We removed these respondents from our analysis as we cannot determine their attitudes about the organization.

Given our two hypotheses, we have two independent variables of interest. The first independent variable of interest measures the race of the respondent. In particular, we create dummy variables for whether the respondent is Black or African American, Latino, or Asian American based on a CMPS question which asks “What do you consider your race or ethnicity?.” We use these variables against a White baseline category and exclude all other respondents to determine whether Black people display the greatest levels of support for the CBC as we hypothesize.Footnote 7 Second, we explore within-group differences in CBC approval levels among Black people with a focus on the age of the respondent. Age is measured in years and ranges from 18-years-old to 90-years-old.

There is good reason to suspect that our broad measures of racial identity may obscure important differences within each group. These differences may amplify or weaken the association between the race of the respondent and support for the CBC. To account for these differences, we first control for whether the respondent is mixed race or not. Mixed race Black people tend to be more conservative and display lower levels of group identity than their monoracial counterparts (Davenport Reference Davenport2018, Parker and Igielnik Reference Parker and Igielnik2020). These factors may lead mixed race people to be less supportive of the CBC. Given that this group is also disproportionately younger, it is important to account for whether the respondent is multiracial or not.

We also control for whether the respondent was born outside of the United States or whether they have at least one parent born outside of the United States. Black immigrants tend to see differences between themselves and Black people who have resided in the United States for a longer period (Clealand Reference Clealand2017; Greer Reference Greer2013; Smith Reference Smith2014).Footnote 8 This disconnect may lead newer Black Americans to view less value in organizations like the CBC which focus on what may be perceived as the Black interests of descendants of slaves. Finally, we control for the sexuality of the respondent. We do this by creating a dummy variable for whether the respondent identifies as being part of the LGBTQIA+ community. Given that Black LGBTQIA+ people often face discrimination from political elites within their own racial group and this group is disproportionately younger (see Cohen Reference Cohen1999), it is important to account for this identity.

We also control for the party and ideology of the respondent. For the former, we control for whether the respondent is a Democrat or Republican with political independents and third-party voters serving as the reference category. For the latter, we use the five-point ideology measure on the 2020 CMPS which ranges from 1— “Very Conservative” to 5—“Very Liberal.” It is important to control for these variables given that the CBC is largely made up of Democratic members of Congress who tend to be more ideologically progressive.

Additionally, we control for contextual factors which may shape Black people’s views of the CBC. First, we control for whether the respondent is represented by a Black member of Congress. We suspect that a respondent who lives in a district that elected a member of the CBC may feel that the organization better represents their interest and thus may be more supportive. Similarly, we control for whether the respondent resides in a district where the elected official is a Democrat. Given the CBC’s ties to the Democratic Party, individuals in these districts may view the organization as being more favorable if they are a partner with their selected member of Congress.

We also account for the percent of Black people in the respondent’s district. Based on the work of White and Laird (Reference White and Laird2020), it is possible that Black people who live around co-racial individuals may feel more pressure to outwardly show their support for an organization which is tied to their racial group. We control for the gender, education level, and income of each respondent. Moreover, demographic factors such as gender and socio-economic status have been increasingly tied to support for racially progressive policies (Lizotte Reference Lizotte2017). Finally, we account for an individual’s economic perceptions and their levels of external efficacy. The latter is measured by a question which asks respondents how hopeful they feel about the economy and is measured on a five-point scale which ranges from 1 = “Much less hopeful” to 5 = “Much more hopeful.” We anticipate that people who feel the most pessimistic about the economy may hold government officials accountable.

Given that not everyone is well-versed in the national legislature (Davidson et al Reference Davidson2019), we want to examine whether our results are robust to segments of the population who may be the most aware of the Congressional Black Caucus. To account for this, we replicate our analysis which includes all respondents with a separate estimation which only includes those who express at least some interest in politics. To accomplish this, we subset our full analysis to individuals who responded “Somewhat Interested” or “Very Interested” to the question “Some people are very interested in politics while other people can’t stand politics, how about you? Are you…?.” In this analysis, we remove respondents who selected “Not That Interested” or “Not at all Interested.”Footnote 9

Beyond subjective measures of political interest, we run an additional analysis which subsets the CMPS to those who know the correct percentage of African Americans in the 117th U.S. House of Representatives within 3 percentage points. The 2020 CMPS asks respondents “What percent of the members of the U.S. House of Representatives do you think are Black or African American?” Given that the correct response for this year was 13%, we coded all responses between 10% and 16% as being correct.Footnote 10 While knowledge and political interest may not perfectly ensure that the respondent is well-versed in the inner workings of the CBC, it provides more confidence that the findings we present below are not artifacts of people guessing in their opinions about the organization.

Are Black People More Supportive of the Congressional Black Caucus?

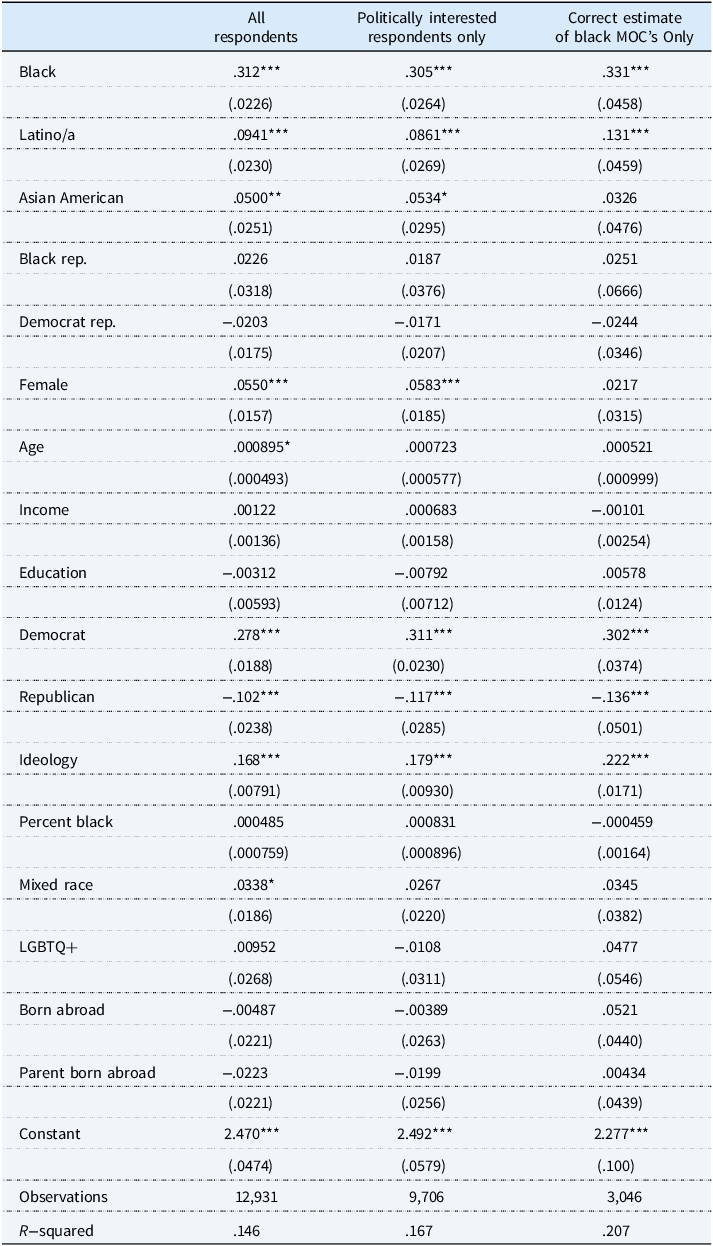

Table 1 presents three OLS regressions predicting support for the CBC on a five-point scale.Footnote 11 , Footnote 12 The first model includes all respondents. The second only includes individuals who self-describe as being at least somewhat interested in politics and the third only includes individuals who are able to guess the percent of Black people in the U.S. House of Representatives within 3

Table 1. OLS regression predicting support for the congressional black caucus

***p <.01, **p < .05, *p < .1. Standard Errors in Parenthesis.

Note: Politically interested respondents are those who state that they are at least somewhat interested in politics. Correct estimate of Black MOC’s include respondents who estimate the percent of Black members in Congress within three percentage points.

percentage points of the true value. The results of Table 1 provide support for our first hypothesis that Black voters are the most supportive of their co-racial caucus in Congress. In fact, Black respondents rate the CBC about a third of a point (.30) more favorable than White respondents on a five-point scale. This result remains consistent when we subset the analysis to those who describe paying at least some attention to politics (.30) and for those who are reasonably accurate about the percent of Black people in Congress (.32). Black people also rate the CBC .22 points more favorable than Latino/a respondents and .26 points more favorable than Asian American respondents. The only exception to these differences is among Black and Latino/a’s who can reasonably correctly estimate the percent of Black people in Congress. Among this group of individuals, Black respondents rate the CBC about .2 points more favorable than similar Latino/a respondents. All of these differences are statistically significant at the p < .01 level.

Latino/as and Asian Americans, holding all else constant, also view the CBC more favorably than White respondents. However, Asian Americans only marginally significantly (p < .1) support the CBC more than White respondents and the differences between these groups are not statistically significant when we confine our sample to only those who know the percent of Black people in Congress. Still, these results suggest that the CBC is generally more appealing to people of color than White people. This finding is not terribly surprising given that the CBC often works with both the Congressional Hispanic Caucus (CHC) and the Congressional Asian Pacific American Conference (CAPAC). Moreover, there are a few cases of overlapping membership among descriptive representatives. For example, Bobby Scott (D-VA) is a member of both the CBC and CAPAC. Similarly, Richie Torres (D-NY) is a member of both the CHC and the CBC. These partnerships may yield positive feelings toward the CBC among Latino/a and Asian American respondents.

Are Some Black People More Supportive of the CBC than Others?

In the previous section, we found strong evidence that Black people were the strongest supporters of the CBC. However, given the diversity within the Black community it is important to explore internal differences within this group. The large number of Black respondents in the 2020 CMPS gives us the opportunity to do so with sufficient statistical power. To accomplish this goal, we estimate the same three models as presented in Table 1 for only Black respondents with the addition of a control for Afro-Latino/as.Footnote 13 As a result, we control for all mixed race groups and have an additional control for Afro-Latino/as given that they make up a non-trivial portion of our data set. We also account for Black immigrants and Black people who have at least one parent born outside of the United States. It is important to account for the wide diversity of Black people in the United States as those with multiple salient racial/ethnic identities may be less likely to prioritize racial representation in government.

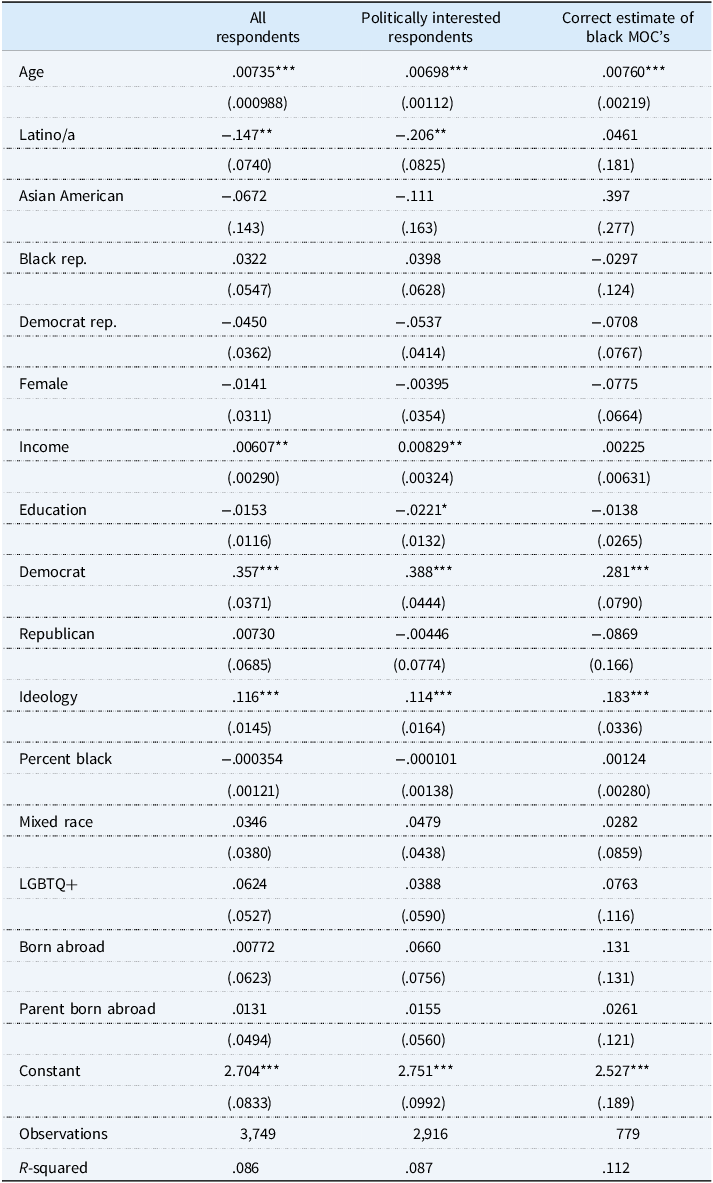

Table 2 presents three OLS regressions predicting approval for the Congressional Black Caucus with only Black respondents. Our independent variable of interest is age which is measured in years. The results in Table 2 provide support for our second hypothesis. Namely, the positive association between age and support for the CBC in the model demonstrates that older Black people are much more supportive of the organization than others.Footnote 14 For every 1-year increase in a Black respondent’s age, their support for the CBC increases by .007 points on a five-point scale. As a result, the difference between the oldest Black respondents (90 years old) in our data set and the youngest black respondents (18 years old) is over half of a point on a five-point scale. This indicates a rather substantial in-group variation among Black respondents. This disparity is greater than that of the difference between Black and White respondents indicating at least as much in-group variation as there is between racial group variation. Moreover, these results hold even when we subset our analysis among Black people who report being at least somewhat interested in politics and among those who can reasonably correctly estimate the number of Black members of the U.S. House of Representatives.

Table 2. OLS regression predicting support for the congressional black caucus among ONLY black respondents

***p <.01, **p < .05, *p <.1. Standard Errors in Parenthesis.

Note: Politically interested respondents are those who state that they are at least somewhat interested in politics. Correct estimate of Black MOC’s include respondents who estimate the percent of Black members in Congress within three percentage points.

Outside of age, a few other variables also predict changes in support for the CBC among Black respondents. Black Democrats and Black people who are ideologically liberal are more supportive of the CBC in comparison to Black people who are political independents or ideologically moderate/conservative. Income is also positively correlated with an increase in support for the CBC among Black people. This may be driven by the fact that the CBC, while an ideologically progressive organization, may take some blame for not addressing the needs of poorer Black people. Gender was not statistically significant, which is surprising since Black women tend to show stronger levels of support for the Democratic Party (Carter and Dowe Reference Carter and Ford Dowe2015).

Why Are Older Black People More Supportive of the Congressional Black Caucus?

In the theory section, we argued that older Black people were more supportive of the CBC for two primary reasons. First, older Black people display higher levels of linked fate than their younger co-racial counterparts. Second, older Black people are more likely to perceive politicians and political organizations as working to advance their political interests in government than younger Black people. If we are correct in these assumptions, the link between age and support for the CBC should be attenuated, at least slightly, with the inclusion of controls tied to linked fate and perceptions of political leaders working in the interest of the respondent.

Baron and Kenny (Reference Baron and Kenny1986) have formalized a method of exploring the mediating effects of different variables using an iterative regression approach. First, researchers run a regression exploring the relationship between their dependent variable and variable of interest with relevant controls. For us, this would be estimating the model presented in Table 2. From this estimation, researchers receive the estimated effect of their independent variable of interest, in our case age, through the correlation coefficient. Researchers then re-estimate the models, but this time include the mediating variables. In our case, linked fate and perceptions of political leaders speaking out on their behalf are included as additional controls. The researcher then compares the coefficient for their independent variable of interest in both models. If the mediating variables matter, the relationship between the dependent variable and independent variable in the second model should be weaker than it was in the initial model.

To estimate this relationship, we replicate the model presented in Table 2 but add in two additional controls that we believe encapsulate our theoretical explanations for why older Black people are more likely to support the CBC. First, we argue that younger Black people would have lower levels of linked fate. Linked fate refers to the idea that one’s identity is such a strong predictor of their political behavior, they will forgo individual benefits for the sake of the group (Dawson Reference Dawson1995; Tate Reference Tate1994). Linked fate is measured in the 2020 CMPS using the question “How much do you think what happens to the following groups here in the U.S. will have something to do with what happens in YOUR life? What happens to Black people…” with responses ranging from 1—“will have nothing to do with what happens in my life” to 5— “A huge amount to do with what happens in my life.”

In addition to linked fate, the 2020 CMPS directly asks respondents “Is there any political leader or any group or organization that you think looks out for your concerns, even if you are not a member of the organization?” This is a “yes” or “no” response. Those who answer “yes” to this question are then given a more specific list of who they are thinking about when they answered in the affirmative. One such category on this list is elected officials. Respondents who answered yes to the first question and then selected elected officials were given a 1 on our mediating variable. All others were given a score of 0. We argue that younger Black people would be less supportive of the CBC because they do not perceive elected officials as working for their interest. We believe that this measure captures this concept.

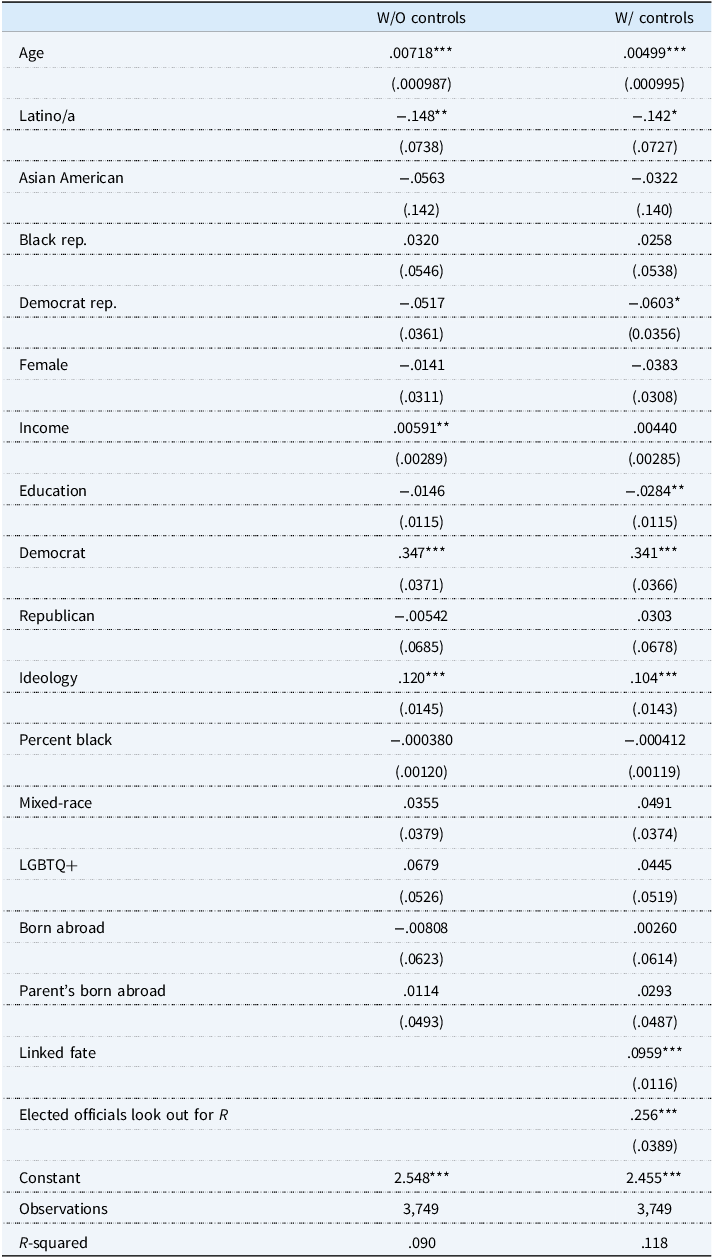

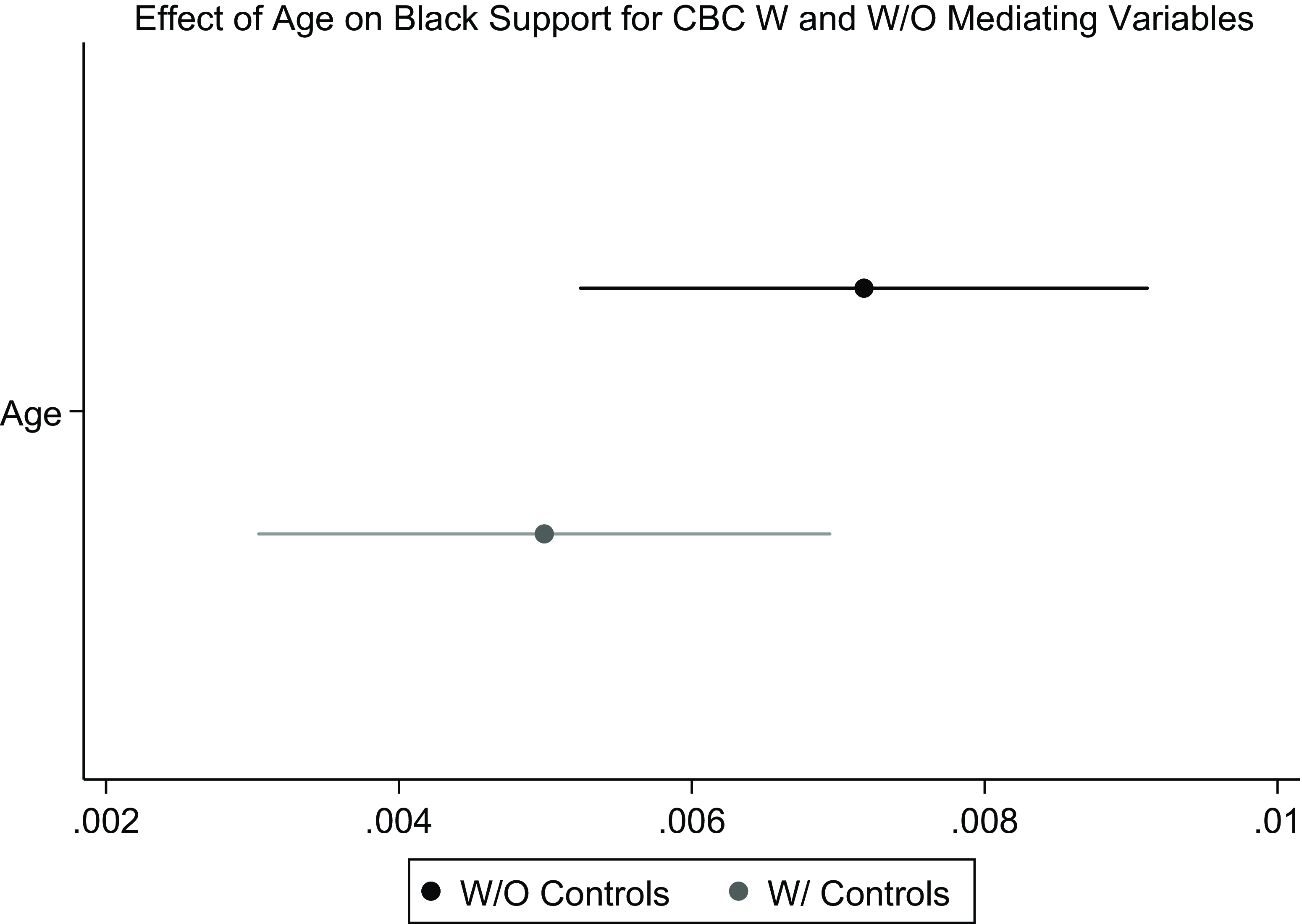

Table 3 presents two OLS regressions predicting support for the CBC on a five-point scale.Footnote 15 The first OLS regression is a replication of the one presented in Table 2 and the second is the same regression with the addition of controls for linked fate and perceptions that elected officials speak out for the respondent. Both models only include Black respondents. Figure 1 maps out the coefficients for age across both models presented in Table 3 graphically with 95% confidence intervals.

Table 3. OLS regression predicting support for the congressional black caucus among only black respondents with and without mediating controls

***p < .01, **p <.05, *p <.1. Standard errors in parenthesis.

Figure 1. Effect of age on support for the congressional black caucus among only black respondents with and without mediating controls. point estimates with 95% confidence intervals.

Both linked fate and perceptions of elected officials speaking on one’s behalf are statistically significant predictors (at p < .01) of support for the CBC.Footnote 16 Moreover, as displayed in Figure 1, the inclusion of these variables leads to a significant decrease in the strength of the relationship between age and support for the Congressional Black Caucus. With the inclusion of the controls, the relationship between age and support for the CBC declines by about 31%. While age remains a significant predictor of support for CBC, the results in Figure 1 show that lower levels of linked fate and higher levels of skepticism that elected officials are working for one’s interest are important reasons why younger Black people are less supportive of their co-racial organization in Congress.

Discussion

Our findings suggest that the age gap in Black people’s support for the CBC is driven by two main factors. The first is declining levels of linked fate among young Black people which has been identified in previous studies (Gillespie Reference Gillespie2009; Mack Reference Mack2012; Smith et al Reference Smith, Bunyasi and Carrera Smith2019). This research argues that the socialization patterns of Black people born in a period that focused on individualism and colorblindness led younger Black people to perceive race as a less defining feature of their life outcomes. In addition to finding that younger Black people have lower levels of linked fate than their older counterparts, through the analysis of other questions in the CMPS, we also find that younger Black people are less likely to list their race as their primary identity in comparison to older Black people. They are also less likely to say that their race is an important part of their identity. While this pattern may change with future generations of Black people, at the moment, Black Millennials and Generation Z’ers do not have the same levels of Black racial consciousness as their older counterparts.

With the declining salience of race, Black organizations like the CBC may no longer be able to rely on an automatic connection between themselves and younger generations of Black people. The CBC must proactively demonstrate to young Black people that they are not only a Black-centric organization, but that they also advocate for broader issues that young Black people care about. The 2020 CMPS asks respondents what issues were the most important. Young Black people, like most Black people, listed stopping racial discrimination, improving wages and income, and criminal justice and police reform as the three issues they cared most about (see Tables 15–17 in Appendix).

In the same year, the CBC put out its agenda for the 117th Congress which overlapped with the collection of the 2020 CMPS. Each of the topics that younger people cared about were listed in the CBC’s agenda for 2021.Footnote 17 Moreover, the CBC made explicit appeals to young people by stating that some of their major goals are to “mobilize the next generation of young people” and advocating for loan forgiveness, addressing rising college tuitions, and investments in training programs.Footnote 18

While the CBC does appear to advocate for the issues that young Black people care about, they may need to do more to demonstrate their value as an organization to this group of voters who may feel frustrated by the pace of change associated with these issues. This may be difficult in a system which has erected many barriers to progress. Nonetheless, drawing the support of younger Black people is a necessity for an organization who relies on the political backing of co-racial individuals to be effective. If the divide between average Black people and their representatives in Congress grows, it may slow progress toward creating a more racially just political system.

Conclusion

For over fifty years, the Congressional Black Caucus has worked to be a voice for Black people in Congress (Barnett Reference Barnett1975; Peay Reference Peay2021; Stanberry Reference Stanberry2022; Tillery Reference Tillery2020). These actions are in part meant to advance Black interests. Given the CBC’s focus it is largely assumed that Black voters would overwhelmingly approve of the organization. This is something that we confirm in this analysis. Black people not only expressed higher levels of support for the organization than White people, but also other communities of color, like Latino/as and Asian Americans.

However, support for the CBC is far from universal among Black people. In fact, this study identified a key cleavage: age. Younger Black people were significantly less supportive of the CBC than their older counterparts. In fact, the variation among Black people in support of the CBC by age was greater than the variation in support for the organization among Black and White people in our sample. This result demonstrates the importance of exploring intersectional relationships when allowed by data availability. It also indicates that not all Black people value co-racial organizations in Congress equally.

We attempted to explore why these differences among Black people exist using mediation analysis. Our additional empirical analysis revealed that some of the lower levels of support among Black youth are tied to younger Black people’s lower levels of a politicized group identity and their general distrust that politicians and elected officials work on their behalf. Overall, while Black people approve of the CBC more than others, the organization has room to grow in its appeal to segments of the Black population.

In particular, the CBC could work to expand its popularity among younger Black people. Younger Black people have come of age in a society marked by significant progress in civil rights and increased diversity in government. Growing up in an era characterized by the rhetoric of colorblindness (Tate Reference Tate2010), some younger Black people may have weaker ties to the broader Black community and see Black institutions like the CBC as less meaningful. While there is likely less that the CBC can do to change Black youths’ levels of linked fate, one way they can increase their support is by highlighting that they are fighting for the issues that younger Black people care about.

As detailed in the discussion section, the CBC advocates for the issues that young Black people are concerned with. However, the CBC does not appear to be making connections with younger black people. This could largely be driven by young Black people’s skepticism with politicians. In fact, as many Black youth in the 2020 CMPS thought that celebrities paid attention to their needs as elected officials. Members of the CBC need to do more work to build trust with younger Black people. This may be accomplished by highlighting the work of younger members who share multiple salient identities with Black people born around the same time. By showcasing the work of younger members of the CBC like Maxwell Frost (D-FL), Erica Lee Carter (D-TX), and Shomari Figures (D-AL) the CBC may appear as being more than their “parent’s Black organization.” Enos and Hersh (Reference Enos and Hersh2015), for example, demonstrate that even if recipients approve of an organization’s message, they are less likely to receive it positively if there is an incongruence in identity between the recipient and the messenger. Even if the CBC is advocating for the issues that young Black people care about they may not be successful in getting their message across unless they alter the face of the organization.

While this study advances our understanding of people’s attitudes about the Congressional Black Caucus, more work is necessary in this area of research. First, the focus of this study was on a single affinity group in Congress, the CBC. There are a wide number of caucuses which work to advance the policy interests of different groups. Future work should explore co-racial support for affinity groups that represent different identities. In the appendix (see Table 10), we show some evidence that Asian American and Latino/a respondents are more supportive of their racial/ethnic affinity group in Congress than White people.

Second, we found evidence that younger Black people’s lower levels of support for the CBC was tied to their lower levels of linked fate and skepticism that politicians will follow through on their promises. Race consciousness is not about agreement with a particular political strategy. Black conservatives and radicals can both have strong racial identities. However, there are higher expectations among the young for leadership that is bold and transformative, rather than symbolic. There is frustration with status quo politics. Having less race consciousness, young Black people find the CBC less relevant to their lives.

Another reason for this difference may be that the CBC and its most visible members are older than the average person in the population. In fact, the average age of a CBC member is more than 60 years old. As a result, young people may not view the CBC as being representative of their interests; and may even view the CBC as being out of touch with the needs and preferences of young Black Americans. With that said, our own analysis exploring the difference between the respondent’s age and the elected official’s age interacted with descriptive representation yields insignificant results (see Table 9 in appendix). Thus, having a Black elected official closer to one’s age does not improve perceptions of the CBC. While statistically we do not find support for this relationship, more qualitative work probing why these disparities occur may be necessary to better understand why young Black people differ from their older counterparts in their views of the CBC.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/rep.2025.10054