Introduction

Food, beyond its role in sustaining life, is central to human existence and holds great cultural, regional, and religious significance. In addition to its gastronomic value, the method of preparation, the raw materials used, the way of serving,Footnote 1 and the events associated with it make food valuable. Food links people and places. The association of food with the identity of people or communities also leads to its diversity.Footnote 2 One of the reasons for food diversity is the different ways in which humans have interacted with their environment and adapted to geo-climatic conditions. Food has been an integral part of social, economic, and traditional status.

The Asian continent is rich in aborigines with a great diversity of culture, tradition, and food habits. While there are shared socio-cultural practices in Asia, there is a striking diversity of food practices. Food habits are so enormously diverse that their regular practice in the community over centuries has led to their adaptation into culture (commonly known as food culture). Invasions, colonial rule, and the introduction of new regulations and laws, world wars, natural calamities, and other events have all influenced food practices in Asian countries.Footnote 3 This diversity is not just confined to disparities between countries, it also manifests within their boundaries.Footnote 4 Notably, food culture in Asia involves standardisation of traditional knowledge passed down from one generation to another. The adaptation of food reflects various factors such as a place's topography, climatic conditions, and people's customs and traditions. India is one such example, where the profession of the people in a particular topography shapes the immense diversity of their cuisine.Footnote 5

Ecological and economic necessities have led to innovations in the food sector. This was prevalent among the local communities in specific topographies. For example, the inhabitants of the mountainous areas of Europe used hard cheese-making to preserve summer milk production.Footnote 6 High-value foods like wines and cheese, as well as essential products like fish and salt, also attracted the attention of trade. The circulation of food products with an extensive geographical history in the trade circle is more prominent than that of agricultural and craft productions based mainly on local resources.Footnote 7 The ‘Geographical Indications (GI)’ product tag represents a well-drafted and safeguarded Code of Practice (CoP). It stands as a symbol of quality that attracts a large number of consumers.

Many countries, including India, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, and Thailand, have negotiated the extension of GI protection to products beyond wines and spirits. They included a broader definition of ‘goods’ in their sui generis legislation. Agricultural products, foodstuffs, and handicrafts are popular classes of goods in addition to wines and spirits that have been recognised for protection by most countries. Apart from the European Union (EU) countries, Asian countries like India, Japan, Bangladesh, Cambodia, Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore have expressly included foodstuffs and agricultural goods in substantive laws and/or practice. This article aims to analyse the scope of protection of foodstuff GIs and their significance in the selected Asian countries, ie, India, Bangladesh, Japan, Malaysia, Cambodia, Indonesia, Thailand, and Singapore. These countries were selected because they have a sui generis system and specifically recognise foodstuffs for GI protection. The scope of protection of processed GI foodstuffs includes sweets, syrups, meat, fish, eggs, and other food products that are readily consumable by humans.

Although the need for studies on the impact of GI registration in developing countriesFootnote 8 has been highlighted, research on GI laws of South Asian countries is very little; in particular, only one comparative study is available.Footnote 9

The existing narrative focuses on the significance of GIs in developing and least-developed countries.Footnote 10 The effects of GI registration has been analysed through a few country-specific (Asian) case studies,Footnote 11 and the socio-economic significance of GI protection in these countries has been discussed.Footnote 12 GIs, as club goods, balance the market by helping consumers to make informed choices.Footnote 13 Agricultural and handicraft GIs have been studied to protect traditional knowledge and local communities. Some of these studies are on Pokkali rice and Navara rice from Kerala, India;Footnote 14 Jasmine rice from Thailand; Gayo coffee and Toraja coffee from Indonesia;Footnote 15 Indian handicraft products like Aranmula Kannadi mirrors, Kondapalli toys, Thanjavur paintings,Footnote 16 and Chhauumasks; Jamdani saree from Bangladesh;Footnote 17 and Batik woven fabrics from Indonesia.Footnote 18 The effect of GI registration of products has been studied in Japan for Miyagi Salmon, Jusanko san Yamato Shijimi clams, Yonezawa beef, Maesawa beef, Higashine cherry, Aomori cassis, and Odate Tonburi fruit.Footnote 19 The impact of GI protection on Japan's Mishima potato demonstrates the potential of GIs to enhance sustainable development.Footnote 20 The post-registration impact studies in IndonesiaFootnote 21 relate either to general registered products or specifically to the coffee sector.Footnote 22 Studies from countries like Malaysia,Footnote 23 Thailand,Footnote 24 India,Footnote 25 and Bangladesh do not discuss the impact of GI registration (including the challenges). Some studies on the governance mechanism of GIs are available for Indonesia, Bangladesh, Japan, and India. Nevertheless, community governance of GIs and post-registration quality control factors are not analysed. The need for promotional management and fluidity of economic chains in Bangladesh for GIs to survive in the marketFootnote 26 has been highlighted. Indian studies have dealt with the GI governance of handicraft products like Benarasi saree,Footnote 27 Aranmula Kannadi mirrors, Pochampally Ikat saree, and Swamimalai bronze icons.Footnote 28 Indian agricultural GIs have also been discussed in existing studies on GI governance.Footnote 29

Although there is a large body of work dealing with the origin of foodstuffs in the EU, foodstuffs of Asia remain to be explored. The present study highlights the evolution of foodstuff GI protection in Asia, including registration requirements, scope of protection, application requirements, and quality control measures in Asian countries. It also examines the post-registration aspects, focusing on quality control measures and the authorised users’ recognition in the respective domestic legislation.

The paper is structured as follows: the first part discusses the Asian food culture, the relation between foodstuffs and GI, and the existing gaps. The second part discusses the evolution and scope of protection of foodstuffs GI in the selected countries, followed by the substantive and procedural pre-registration requirements for foodstuff GI registration. The third part of the paper reviews the post-registration quality control and recognition of the authorised users or producers’ communities. The critical aspects identified in the study are discussed in the conclusion, together with the policy implications.

Methodology

A comparative qualitative analysis method has been utilised in this study. The qualitative data were collected from primary and secondary sources like statutes and scholarly works for the selected countries. The parameters of the study include the definition of the term ‘foodstuff GIs’, the scope of protection of foodstuffs as GI in the selected countries, and the similarities and differences in the registration requirements for food products from the statutory perspective. The evolution of the GI protection of foodstuffs is identified on the basis of the enactments in the different countries in two stages, ie, the laws prior to accession to the World Trade Organisation (WTO), and the legislative approaches adopted for foodstuffs GI protection in compliance with the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS).Footnote 30 The pathway towards sui generis protection of GI, especially foodstuffs GIs, post TRIPS is analysed on the basis of information available on the intellectual property websites of the respective countries.

The post-registration management of GI products is analysed in terms of the information on quality control of foodstuff GIs provided by producers, the recognition of producers, and the registration of authorised users. Legislations were studied in detail to understand the requirements for quality control of registered foodstuffs. Published works on the recognition of authorised users’ recognition and the further impact of GI registration on the quality of the products were analysed.

Results

Evolution of Protection of Foodstuff GIs

Member states to WTO either continued with their existing system of protection (like the US and Australia) or enacted a sui generis system to comply with TRIPS. However, the selected countries created their respective specific laws to protect GIs after their ratification of TRIPS. Countries like Japan and Indonesia, however, are exceptions, as they extended the protection of GIs under their domestic trademark laws before switching to the sui generis system. TRIPS compliance began immediately in India and Malaysia, which enacted sui generis GI legislations in 1999 and 2000 respectively. Thailand drafted its GI legislation in 2003. In response to its accession to the WTO in 2004, Cambodia framed the procedural laws for registering and protecting GIs in 2007, and later, in 2014, developed a full-fledged substantive law. In the same year, Indonesia developed its own sui generis provisions for GI protection as extended protection under its trademark system. On the other hand, Bangladesh, Singapore, and Japan commenced their sui generis systems in 2013, 2014, and 2015 respectively.Footnote 31 Figure 1 shows a timeline of the evolution of foodstuffs protection under the sui generis GI system in the selected countries.

Figure 1. Evolution of foodstuff GI protection in selected Asian countries

Although Article 22 of TRIPS provides a minimum GI protection standard for all goods, the enhanced GI protection under TRIPS was only extended to wines and spirits under Article 23.Footnote 32 Post TRIPS, at the 2001 Doha Ministerial Conference, many countries came together with a more explicit mandate to negotiate for GI protection in TRIPS and the General Council. These countries, called ‘GI friends’,Footnote 33 discussed among themselves the extension of GI protection under Article 23 of TRIPS to all products. In their view, the GI register under Article 23 of TRIPS should be extended to all products other than wines and spirits. It will be pertinent to note here that the main intention behind this proposal was to protect other traditional products and the communities associated with their production. As TRIPS sets up minimum standards of protection, the protection of other products by the member countries should be available for expansion.

Article 22 of TRIPS does not define ‘goods’; hence the member states have interpreted it as per their respective national policy considerations. In the present study, the selected Asian countries are broadly classified into three categories. Countries in the first group expressly includes foodstuffs in the definition of ‘goods’, such as India, Bangladesh, Indonesia, and Japan. The second group consists of countries like Malaysia and Thailand, which do not expressly include the term ‘foodstuffs’ under the ambit of ‘goods’, but in practice protect processed foodstuffs. Singapore falls into the third and final category, where neither the definition of the term ‘goods’ mentions foodstuffs nor foodstuffs are protected. Obviously, where the scope of protection of foodstuffs as GIs under the law is expressly defined, there is less chance of ambiguity. In such cases, foodstuffs with a proper classification available in the domestic laws will not be left unprotected or overlooked for protection.

By December 2023, Cambodia has registered four local products – GI Kampot pepper, Kampong Speu palm sugar, Mondulkiri wild honey, and Koh Trung pomelo – as well as two foreign products that include Champagne and Scotch Whisky. In some culinary and tourism studies, these are referred to as foodstuffs. Bangladesh has registered nine products, of which Hilsa and Black Tiger prawns can be considered foodstuffs (according to the Indian standards of food GIs registered, comparable to Jhabua Kadaknath black chicken meat from India). However, without a list of classes of goods or a definition of foodstuffs, it is unclear whether they fall under the foodstuff category. Indonesia, which has foodstuffs mentioned in statute, effectively protects the four domestic foodstuffs eel, milk, horse milk, and milkfish, as well as seven foreign foodstuffs (mainly wines and spirits, cheeses, and hams) as GIs.

Article 2(1) of the GI Act of Japan Footnote 34 defines ‘foodstuffs’ as all food and drinks, excluding items that fall under the Liquor Tax Act 1953, or any medicines or quasi-pharmaceutical products. The main objectives of protecting foodstuffs as GIs under this Act are:

a) protecting the regional brand and revitalising the rural villages,

b) protecting the traditional food culture and practices and ensuring that these practices are continued, and

c) consumer welfare.Footnote 35

The Japanese Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF) classification of goods for GI protection can be considered as one of the more systematic classifications among the countries. This categorisation expressly distinguishes the protection of processed foodstuffs from vegetables/cereal grains/pulses, fruits, meat, fish, and shellfish. However, the classification of the products is an administrative initiative, and the GI statute does not include such a broad grouping of goods. Currently, Japan has twenty national products registered in the processed foodstuffs class.Footnote 36

The Indian Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration and Protection) Act 1999 (Indian GI Act) expressly includes foodstuffs within the scope of GI protection, as section 2(f)Footnote 37 stipulates that the term ‘goods’ means ‘any agricultural, natural or manufactured goods or any goods of handicraft or of industry and includes foodstuff’. In India, products protected as ‘foodstuffs GI’ mainly belong to Classes 29 and 31 of the Fourth Schedule under the GI Rules 2002.Footnote 38 Unlike Japan, India does not distinguish between processed foodstuffs, meat, fish, and shellfish. The Indian foodstuff GI covers sweet preparations, savoury foods, and raw meat. Seventeen domestic and three foreign products are protected in India under the foodstuff categories. The foreign foodstuffs registered in India mainly include different cheese varieties from Italy.

It is interesting to note that although Malaysia does not include foodstuffs in the scope of protection, in practice it has protected processed foodstuffs like Kek Lapis Sarawak (Sarawak layered cake), Sarawak Sesar Unjur dried shrimp, Sarawak Umai raw fish salad, and Biskut Dan Dan from Sungai Lembing. It also covers foreign products like Parmigiano Reggiano, a type of cheese from Italy. As in Malaysia, Thailand's statute – ie, the Act on Protection of Geographical Indications 2003Footnote 39 – does not explicitly include ‘foodstuffs’ in its sui generis system. However, in practice, the Department of Intellectual Property (the competent authority for GI registration in Thailand) has granted GI protection to various foodstuffs in Thailand. Trang Roast pork, Surat Thani oysters, and Chaiya salted eggs are popular foodstuffs with GI tags. The GI law in Thailand aims for multifaceted benefits of GI registration, like enhancing food quality, opening up market demand for Thai traditional and GI products, and encouraging GI tourism. For example, there is a great demand among tourists for Surat Thani oysters, which are clean and white, with thick, creamy textures. When consumed with lime juice, garlic, fresh chilly, fried onion, and local sprigs, it gives a delicious taste and, in turn, generates enormous revenue for the place.

The foreign GIs protected in Asia are mainly from EU countries. The recent international trade negotiations between the EU and other countries are possibly the main reason for the successful protection of EU GIs in some of the selected countries, such as Japan and Singapore.Footnote 40 However, foodstuffs from non-EU countries, like the United Kingdom and Peru, have also acquired their position in the GI registers of selected Asian countries like India. Such implementation will provide a firm ground for the selected countries to obtain better national treatment from their trading partners.Footnote 41

It is observed that although some countries do not mention foodstuff GIs in the substantive part of the law, in practice the foodstuffs are registered as GIs. Table 1 provides a brief comparative overview of the protection of foodstuffs under the national laws of these jurisdictions.

Table 1. Comparative analysis of the protection of foodstuffs under the GI legislations of the selected countries

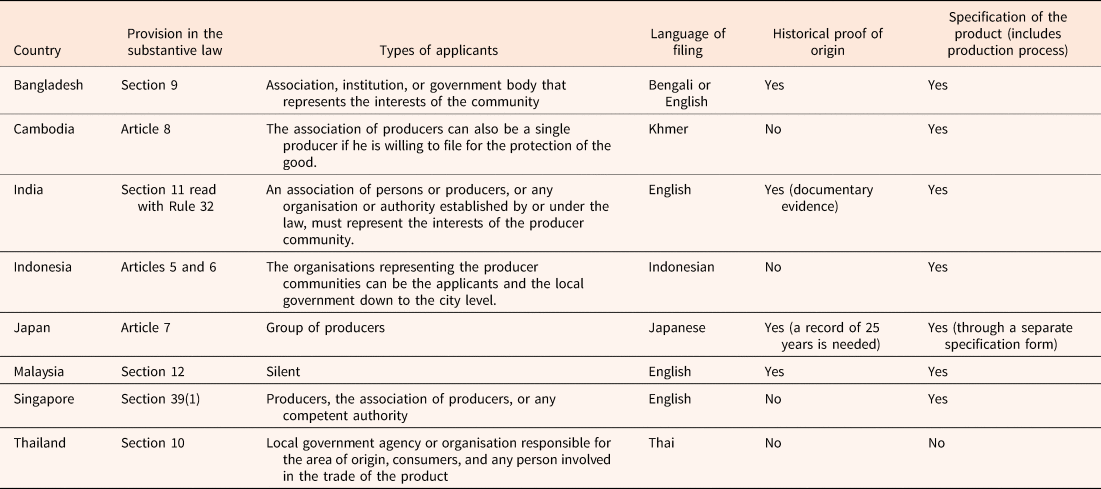

Registration is an important aspect of recognising a potential product as GI. Registration of GIs not only acknowledges the product, but also confers legal protection and remedies to the places and communities associated with it to prevent inappropriate use. Understanding the definition of an applicant is the first step in registering a GI. Unlike a trademark, a GI is a community right. Therefore, the GI legislations of the selected countries define ‘applicants’ to endorse the welfare and development of the community, as will be seen below. Once the applicant is determined, the process of filing an application with the relevant authority is commenced by the eligible applicants. The examination, advertisement, opposition (if any), hearing of the opposition, and the final entry in the respective GI registers complete the whole registration process. The procedure is similar in all the selected jurisdictions. However, some countries have different application requirements, mainly in terms of supporting documents, quality control requirements, and the available language options for filing applications. A detailed comparison of the application requirements of the selected jurisdictions is provided in the subsequent sections of this study.

The Varied Nature of the Applicant Category Benefits the Registration of a GI

As GI is a community right, the applicant can be the communities themselves. This is acknowledged by law or by an organisation or governmental agency representing a community. In most of the selected countries, the substantive GI laws are flexible in defining the term ‘applicant’. Associations of producers, legal entities, and organisations representing producers or the communities, including the government institutions, are eligible to file GI applications. However, in countries like India, Thailand, and Malaysia, public authorities or government institutions are the predominant parties filing GI applications.

On the other hand, in countries like Indonesia, Cambodia, and Japan, only the producer's community can file applications. Indian law upholds the interests of producer communities. Hence, in the Indian statute, the applicant must be an association of persons or producers, or any organisation or authority established by or under the law, and must represent the interests of the producer community. For foodstuff GIs in India, it has been observed that the producer's community forms a trust or society and submits the application for registration along with the government institutions, either jointlyFootnote 42 or independently. In most of the registered foodstuff GIs, the producers’ welfare associations are the applicants. Foodstuff GIs such as Joynagar Moa and Dharwad Pedha stand as exceptions, where the community had formed the society or trust and filed the application independently. Nonetheless, Odisha Rasagola, Bardhaman Sitabhog, and Bardhaman Mihidana are examples where the government body and the producers’ association jointly applied for registration. Bangladesh's GI laws also provide for an association, institution, or government body representing the community's interests to be an applicant.

The Indonesian GI lawFootnote 43 expressly allows the local government up to the city level and an organisation or association of producers and cooperative agencies established for the producers to apply for registration.Footnote 44 An association can be under the leadership of a municipal or city-level government that includes the producers, members from outside the community that may involve a lawyer, academic expert, or other person associated with skills-training institutions.Footnote 45 However, government agencies are not directly involved in the registration process as applicants. Unlike Indonesia, the GI laws of India and Bangladesh are silent on the association's constitution.

The definition of ‘applicants’ in the GI law of ThailandFootnote 46 is more comprehensive than in other countries. There are three categories of applicants under the GI Act. First, any local governmental agency or organisation with a distinct legal identity that has been responsible for the place of origin of the goods can be an applicant. Second, a natural person or a group of persons can be an applicant, provided that there is a connection with the product's trade and that they are resident in the geographical area of the goods produced. Third, a consumer of the ‘good’ with the GI tag can also be an applicant. Consumers and governmental agencies need to be related to the GI good as users or as those responsible for the product's place of origin, respectively.

The GI statute of Japan states that only a ‘group of producers’ can be the applicant. The statute defines a ‘group of producers’ as a group comprised of producers as direct or indirect members, as provided by the order of the Japanese Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries.Footnote 47 Cambodia defines ‘applicants’ expressly as an association,Footnote 48 but there is an exception: it recognises a single producer or operator as an association if it is the only one willing to apply for GI registration of the product.Footnote 49 The GI Act of SingaporeFootnote 50 follows the general definition provided in the laws of the other selected countries (except Malaysia). Producers, associations of producers, or any competent authority can be applicants in Singapore, including a single producer who produces the product in the geographical area specified in the application for registration. The competent authority can only be an applicant if it is responsible for the GI. The Malaysian Act,Footnote 51 one of the oldest GI legislations amongst the selected countries, does not elaborate on the definition of ‘applicant’. In practice, however, the majority of GIs in Malaysia are filed by government agencies.Footnote 52 However, the new Malaysian GI Act promulgated in 2022 states in Article 8(1) that any person can be an applicant.Footnote 53

Differences in Application Requirements for GI Registration

The GI legislations of the selected countries specify the application requirements. The specification of the product and a map of the geographical area of production highlighting the link between the product and the place are two standard documents required. The comparison of the documents relating to the historical proof of origin, the accounts, the statutes, and the association regulations revealed differences from one jurisdiction to another.

The Indian GI lawFootnote 54 expressly mentions the supporting documents to be submitted with the application for registration. The requirements include historical proof of the product's origin, specifications, the product's class according to the law, and quality control mechanisms. However, the application form also contains other requirements that go beyond the provisions of the law and which are in consonance with the GI rules, such as the structure of the inspection body and the uniqueness of the product. The uniqueness of the product varies in many ways apart from the product's place of origin. For example, Dharwad Pedha encompasses traditional knowledge safeguarded by the family. Banglar Rasogolla, Bardhaman Sitabhog, and Bardhaman Mihidana exhibit uniqueness through a combination of geo-climatic factors and human craftsmanship. Certain food GIs, like Hyderabad Haleem, Palani Panchamirtham, and Tirupati Laddu carry religious significance. The historical origin of the product and the specification must include the product-place linkage along with its inherent natural and human factors. The application requirements in BangladeshFootnote 55 are similar to those in India, but additional information is required. In addition to the historical proof of origin, the application must include the period of usage of the product and details of the product's users.Footnote 56 Bangladesh has fewer registered GIs than India, and no registered foodstuffs.

The application requirements for Cambodia are set out in both the procedural law and the substantive part of the GI law. The application requirements in the Cambodian system expressly state that the meaning of the phrase ‘other documents’ in the substantive law should be read on a par with the ministerial declaration.Footnote 57

The Japanese GI lawFootnote 58 covers a wide range of goods, with processed foodstuffs being a distinct category expressly defined in the substantive law, mirroring similar provisions in the other selected countries. Although Japan has a processed foodstuff category distinct from meat, fish, shellfish, and other consumable goods, it lacks specific application requirements for this category. However, the standards set by MAFF provide some of the general guidelines for the application. Similarly, in the other selected jurisdictions, the applicant is required to submit the characteristic features and specifications of the product. Nonetheless, Japan maintains its inclusive list of characteristics, disallowing the use of abstract terms like ‘delicious’, ‘wonderful’, and ‘very nice’ when describing the quality of the product. Japan requires historical proof of production or origin. In contrast to the other countries, applicants in Japan must provide documentary evidence of a specific number of years of production, which is explicitly stated by MAFF: twenty-five. The twenty-five years of production should be consistent. This consistency includes the maintenance of specific characteristics of the products that distinguish the product from others of the same breed or variety throughout the period. Conversely, in cases of discontinuation, the law strictly stipulates that the applicants (the group of producers) must state the period and the reason for discontinuation in their application.

Unlike Japan, India, and Bangladesh, the Cambodian system is flexible regarding the period of use or historical proof of origin. In Cambodia, documentation requirements include evidence of the product-place link, a product description, information on the production method, and information on the labelling of GI products. The filing process is more straightforward, as the producer's community need not prove the historical linkage of the people to the product and place.Footnote 59

In a typical scenario, the community either finds the missing historical data or indicates that the historical data is undocumented. The latter is a hindrance that delays the filing process or discourages the producers of the potential products from applying for registration. In some countries, such as India, it is also a ground for abandoning applications; Hyderabadi Biryani (Application No 168), Agra Petha (Application No 223), and Agra Dalmoth (Application No 222) are some examples of abandoned applications on this ground. Although Cambodia has ratified the Geneva Act of the Lisbon Agreement 2015,Footnote 60 it has yet to register a processed foodstuff GI.

Unlike Cambodia, the application requirements of Thailand are part of the substantive law. Documents relating to the sustenance of quality, reputation, or other characteristics of the goods, and the linkage with the geographical origin must be attached to the application. Only a few requirements are stipulated in the statute, the rest being derived from the ministerial regulations.Footnote 61 However, the regulation is silent on the accompanying documents. Thailand's application requirements are more flexible than those of India, Japan, Cambodia, and Bangladesh. Historical proof of origin, a statement of case including production or manufacturing mechanism, is optional for registration. The Malaysian GI legislation, similar to that of Thailand, provides a general mandate on the application requirements. The details of the applicant, the goods, the geographical area, and the documents proving the quality, reputation, characteristics, and association of the product with its geographical location of origin should be provided.Footnote 62 The description of the product, other product characteristics, and proof of origin, the link between the product and the place, and the inspection body are additional information to be submitted.

The application requirements in Indonesia are mentioned in the government regulation.Footnote 63 The provisions relating to application requirements are identical to those in Cambodia. Indonesian law is silent on the submission of historical proof of origin. Nonetheless, there is a requirement to submit product-place links and product characteristics (for foodstuffs).

One of Asia's most recent GI legislations is Singapore's Geographical Indications Act 2014, which regulates the submission of supporting documents similarly to all other countries except Japan and Cambodia. However, the description of quality, reputation, and other characteristics is required. For example, the definition of goods includes the principal physical, microbiological, and chemical characteristics of the goods, as well as their organoleptic features. When describing the goods/product, the applicant should also mention the difference between the potential GI product and other products in the same category. Applicants in Singapore must also demonstrate that the product's reputation is linked to its geographical area of origin through documentary evidence such as specialist books, press reports, or prestigious awards. Singapore also emphasises quality control mechanisms. It is also pertinent to mention that Singapore's local products have yet to be registered as GI. However, Singapore entered into international arrangements with the EU in 2019. Since then, the GIs registered in Singapore have mainly come from the EU, a testament to the collaboration between the two regions.

The language of the filing also holds significance in the application procedure. Some countries, such as Bangladesh, Indonesia, Japan, Cambodia, and Thailand, allow the application to be filed in English and vernacular languages. Filing in the local language makes the process easier and less rigorous, as the producer communities are well versed in it. Documents like historical proof of origin are commonly available in the local language. Translating these documents into the official language or English may present new challenges for the community. In India, the language for filing GI applications is English. This is one of the reasons for delays in the filing and registration process in cases where producers are not familiar with English.Footnote 64 Malaysia and Singapore also make it mandatory to apply in English. A brief comparative overview of application requirements in the selected countries is given in Table 2.

Table 2. Comparison of the application requirements in the selected jurisdictions

Quality Control: Structure-Function Differences

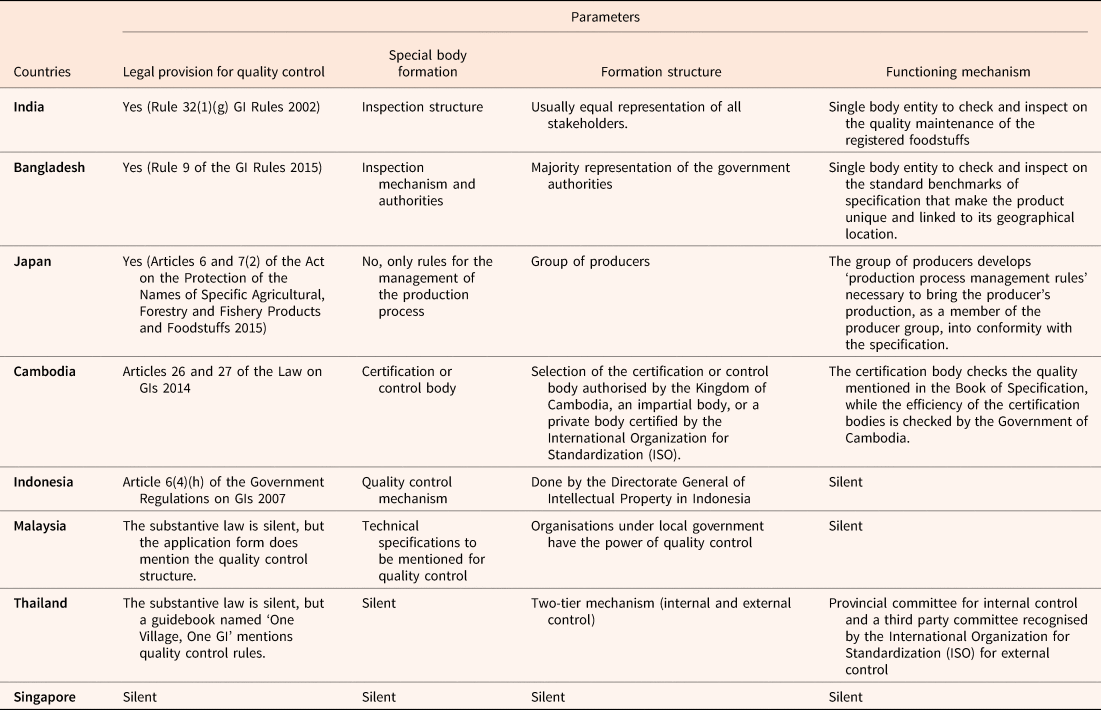

One of the essential documentary requirements of the application is to identify the quality control aspects of GI products. Quality control of a GI product starts with the standard set by the producers’ community. Quality is not a pre-defined term; it is negotiated by the producer(s) or the community. The community unanimously develops measures commonly known as CoPs (Community Protocols). A CoP includes a control plan or requirement for an inspection body that will ensure the maintenance of the quality of the GI product. Quality control through a structured CoP serves for healthy competition in the market among the community. It also builds trust among the consumers regarding the premium quality of the product. It is not only linked to the final product, but includes the process as well. Product conformity for foodstuff is checked through various measurable aspects such as composition, shape, taste, and colour. The quality control method starts with defining the quality of the products in convergence with the specifications mentioned in the application for registration. A significant step for quality control is to verify that the CoP is followed by each producer and that the product meets the specification standards. A comparative analysis has been carried out to understand the quality control system in the selected countries, which is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Process and impact of quality control of the registered productsFootnote 65

Table 3 illustrates the scope and management of quality control in the selected countries. Countries like India, Bangladesh, and Cambodia expressly set out the formation and function of quality control bodies or have established rules governing them. However, the nomenclature varies from country to country. In Japan, for example, such rules are called ‘management rules’.

Table 3. Comparative study on quality control of food GIs in the selected countries

While the formation of an inspection body is not part of the main text of the GI Act 1999 in India, the GI Rules 2002 make it mandatory to form an inspection body.Footnote 66 Inspection bodies carry out inspections only in some cases, with community members commonly doing this instead.Footnote 67 There is also no particular structure in the law to encourage the formation of an inspection body for Indian foodstuff GIs. For example, Dharwad Pedha, India's first registered foodstuff GI, has a standard and quality committee under a trust (Thakur's Dharwad Pedha Manufacturer's Welfare Trust). The standard and quality committee constitutes the inspection body for Dharwad Pedha, and committee members must be family members. GIs like Banglar Rasogolla and Joynagar Moa have an inspection body comprising representatives of all stakeholders, such as administrative and government representatives, academic experts from reputed institutes, and members of the producer association or communities. The inspection body of Hyderabad Haleem constitutes only one organisation, namely the National Research Centre on Meat, Hyderabad. The primary function of this body is to oversee the adherence to standards of raw materials, especially meat, which is the main ingredient of this foodstuff. The provisions are theoretical and far from practical, unlike the EU GI system where quality control is at the core of GI registration.

BangladeshFootnote 68 also emphasises the formation of an inspection body at the time of application. Japan,Footnote 69 Cambodia, and MalaysiaFootnote 70 emphasise the documents that describe the control plan and technical specifications, respectively, alongside the application for registration. Cambodia's two-tier quality control mechanism, resembling the French system in the EU,Footnote 71 involves producers carrying out internal control, while external control is executed by a certification body approved by the Ministry of Commerce.Footnote 72 The IndonesianFootnote 73 government regulation mandates applicants to form a quality control mechanism and submit it along with the application. As observed in all selected countries except Thailand and Singapore, the quality control body or rules are generally formed during or before the application is filed. The respective statutes of Thailand and Singapore are silent on the quality control mechanism of the GIs, but quality control mechanisms have to be presented along with the application. However, the quality checks start only once the product gets the GI tag. Regrettably, there is no available literature to date on the quality control bodies and their functions in the above-mentioned Asian countries.

Discussion and Policy Implications

The comparative study of the selected jurisdictions provides several insights into the evolution and scope of foodstuff protection, eligible applicants, application requirements, and quality control. There are similarities and differences in GI laws among the countries. Public policies must contribute to enhance and foster the potential of GI goods. Although Asia's processed food sector is yet to succeed in making use of this vital intellectual property rights tool, supportive policy would help the nations to grow their food heritage. The forth coming or existing GI policy should encourage the registration and promotion of foodstuff GIs to preserve and promote food heritage. The key factors that have policy implications are discussed below.

The contrasts in the scope of protection provide an insight into the express or implicit inclusion of foodstuff in the definition of ‘goods’ that can be protected as GIs. Our findings suggest that the ambit of GI protection varies across the selected countries. The GI statutes of Singapore and Japan are among the most recent GI legislation of the selected countries. However, the extent of registration of foodstuffs is different. All the selected countries, except Malaysia, Singapore, and Thailand, specifically recognise and protect foodstuff GIs under their legislation. The inadequate public policies to protect foodstuffs as GIs are dangerous for the community and the product. In the absence of specific laws for traditional knowledge and traditional cultural expressions, GI protection can be a solution. Hence, the express protection of gastronomic heritage is necessary to preserve the specialised knowledge, skills, and traditions of a specific region and people.

The diverse pre-registration requirements primarily involve state intervention and controls. The absence of producers in the GI implementation system demonstrates the need for greater management at the local level. A recent study has shown that one of the main reasons for state intervention is to demonstrate the state's sovereignty over the territory recognised by the GI tags on the product.Footnote 74 Existing work has also highlighted that state intervention has an intention of achieving a greater good, apart from simply claiming sovereignty.Footnote 75 The preservation of national heritage, the support to producers, and the coverage of costs of GI enforcement are some of the examples of such greater goods.Footnote 76 The absence of local producers in the policy measures also raises concerns. The public-private partnership structure of GI protection should be maintained, ie, the protection of producers’ rights and the common heritage. The states should play an active role in ensuring a valid authorisation of the producers’ community. Registration of authorised users will protect producers from counterfeiting and unauthorised exclusion from the use of geographical names. The detailed requirements under the GI laws in the selected countries and the lack of facilitation mechanisms limit the critical outcomes of interest, ie, GI registration and authorised user registration. Simplification of filing language requirements and documentary evidence would be beneficial for enhancing registration. This implies targeted registration of food products, thereby recognising the socio-economic rights of the specific communities.

Quality control is one of the key post-registration activities that should be taken care of to ensure continued relevance in the market. In practice, therefore, the actors in the value chain must be present in the quality control and management structures that carry out the inspection. The state is seen as the appropriate authority to monitor producers, rather than the producer association. State interference in the selected countries shows weak self-governance and collective action as a community. Producer representation is essential for product quality control. While the existing top-down model of producers involved in GI quality maintenance is necessary, a more local approach is crucial. Some studies suggest that a policy covering the entire GI identification and value chain process is required.Footnote 77 Such a policy maximises the positive effects and minimises the negative ones and is called a ‘proactive GI policy’.Footnote 78 A balanced and appropriate mix of public and private initiatives is necessary to manage the GI system and promote rural development. The findings of this paper indicate the need to involve different levels of stakeholders in the definition of public policy for foodstuff GIs. Policy considerations at various levels are required for the promotion and protection of foodstuffs GI. The key factors for studying policy implications that help to support a GI system are: first, the recognition and impact of GI registration in improving GI productivity; second, the trade policies of countries to foster food GIs; and finally, strengthening linkages at national, regional, and local levels, ie, mechanisms for supply chain, quality maintenance, and livelihood support.

In order to achieve the sustainable development of GI products, it is necessary to develop a consolidated policy that encourages the concept of ‘local to global’ and supports local and rural development. This policy should take into account different levels of production and quality circles. It must be a part of the local governance system. Figure 3 provides an illustrative policy diagram focusing on the local governance system.

Figure 3. Policy implications for enhancing foodstuff GIs

Conclusion

It is suggested that institutions that are involved in local governance should be empowered to support and enforce the sustainable framework for GIs. Among the various factors that need to be considered are awareness programmes at different stakeholder levels, the need to promote fair trade, the encouragement of value redistribution along the food chain or supply chain for the entire territory, and the protection of public interest. Above that, the approach needs to be environmentally sound and to respect and uphold cultural values. Policies should consider possible actions such as preventing distress migration of future generations of communities, and encourage sustainable production practices in local GI production systems. GI has a virtuous circle involving four steps or phases: identification, qualification, remuneration, and reproduction of resources.Footnote 79 Stakeholders must be encouraged to participate and contribute effectively to the development of such a system. The state should be proactive in ensuring adequate quality certification of products and in promoting local governance. A sound legal policy framework that achieves the collective interest and defines the responsibilities of the stakeholders will be an ideal way forward for a sustainable food policy.