Introduction

The ecological and agricultural significance of lepidopteran stemborers lies not merely in their presence but also in the extent of their impacts on crop productivity across diverse environments (Assefa et al. Reference Assefa, Conlong, Van Den Berg and Mitchell2010; Goftishu et al. Reference Goftishu, Assefa, Niba and Fininsa2017; Ntirenganya et al. Reference Ntirenganya, Goftishu, Sokame, Assefa and Nsengimana2025). They tunnel and cloaked inside the host plant’s stems and feed on the internal cavity of the plant (Assefa Reference Assefa2006; Goftishu et al. Reference Goftishu, Assefa, Niba and Fininsa2017; Overholt et al. Reference Overholt, Maes and Goebel2001), making them very difficult to control (Ntirenganya et al. Reference Ntirenganya, Goftishu, Sokame, Assefa and Nsengimana2025; Overholt et al. Reference Overholt, Maes and Goebel2001). More effort has been devoted to understanding stemborers’ ecological habitats and their relationships with host plants (Goftishu et al. Reference Goftishu, Assefa, Niba, Fininsa and Le Ru2018; Midega et al. Reference Midega, Bruce, Pickett and Khan2015; Ntirenganya et al. Reference Ntirenganya, Goftishu, Sokame, Assefa and Nsengimana2025; Overholt et al. Reference Overholt, Maes and Goebel2001). However, the interactions between crop and wild stemborer hosts remain poorly understood, limiting our ability to develop integrated management strategies that effectively address both pests and the full range of their host plants.

Over the past 20 years, assessments of stemborer species and their host plants were conducted (Assefa Reference Assefa2006; Goftishu et al. Reference Goftishu, Assefa, Niba, Fininsa and Le Ru2018; Le Rü et al. Reference Le Rü, Ong’amo, Moyal, Muchugu, Ngala, Musyoka, Abdullah, Matama-Kauma, Lada, Pallangyo, Omwega, Schulthess, Calatayud and Silvain2006a, 2006b; Moolman et al. Reference Moolman, Van Den Berg, Conlong, Cugala, Siebert and Le Ru2014; Ntirenganya et al. Reference Ntirenganya, Goftishu, Sokame, Assefa and Nsengimana2025; Otieno et al. Reference Otieno, Le Ru, Ong’amo, Moyal, Dupas, Calatayud and Silvain2008; Overholt et al. Reference Overholt, Maes and Goebel2001). From these studies, more than 150 lepidopteran stemborer species (families Crambidae, Noctuidae, Pyralidae, and Tortricidae) were reported (Assefa et al. Reference Assefa, Conlong, Van Den Berg and Mitchell2010; Goftishu et al. Reference Goftishu, Assefa, Niba, Fininsa and Le Ru2018; Kfir Reference Kfir1992; Khan et al. Reference Khan, Chiliswa, Ampong-Nyarko, Smart, Polaszek, Wandera and Mulaa1997; Le Rü et al. Reference Le Rü, Ong’amo, Moyal, Muchugu, Ngala, Musyoka, Abdullah, Matama-Kauma, Lada, Pallangyo, Omwega, Schulthess, Calatayud and Silvain2006a), of which more than 21 species having major effects on agricultural yield, attacking maize, sorghum, wheat, rice, sugarcane, and related cereal crops across tropical and subtropical regions (Overholt et al. Reference Overholt, Maes and Goebel2001; Sokame et al. Reference Sokame, Rebaudo, Musyoka, Obonyo, Mailafiya, Le Ru, Kilalo, Juma and Calatayud2019). The remaining species occur primarily in wild plants under the Poaceae, Cyperaceae, Typhaceae, and related vegetation families, where they play an important ecological roles as native herbivores. These vegetation serve as reservoirs for pest stemborers (Goftishu et al. Reference Goftishu, Assefa, Niba, Fininsa and Le Ru2018; Le Rü et al. Reference Le Rü, Ong’amo, Moyal, Ngala, Musyoka, Abdullah, Cugala, Defabachew, Haile, Matama, Lada, Negassi, Pallangyo, Ravolonandrianina, Sidumo, Omwega, Schulthess, Calatayud and Silvain2006b; Sokame et al. Reference Sokame, Malusi, Subramanian, Kilalo, Juma and Calatayud2022; Tefera Reference Tefera2004).

In Sub-Saharan Africa, Noctuids Buseola fusca Fuller, 1901 and Sesamia calamistis Hampson, 1910, crambids Chilo partellus Swinhoe, 1885, Chilo orichalcociliellus Strand, and the pyralid Eldana saccharina Walker, 1865 are key stemborers widely distributed (Assefa Reference Assefa2006; Assefa et al. Reference Assefa, Conlong, Van Den Berg and Mitchell2010; Ntirenganya et al. Reference Ntirenganya, Goftishu, Sokame, Assefa and Nsengimana2025; Overholt et al. Reference Overholt, Maes and Goebel2001). With the exception of C. partellus, which is native to Asia (Asmare et al. Reference Asmare, Emana, Ferdu and Amare2014; Kfir Reference Kfir1992; Kfir et al. Reference Kfir, Overholt, Khan and Polaszek2002), other species are native to Africa (Kfir Reference Kfir1992; Khan et al. Reference Khan, Chiliswa, Ampong-Nyarko, Smart, Polaszek, Wandera and Mulaa1997; Maes Reference Maes and Polaszek1998). Sesamia calamistis Hampson, 1910, Sesamia nonagrioides Lefèbvre, 1827, and other Sesamia species are widely distributed across sub-Saharan Africa, including West, Central, East, and Southern Africa, and extending to Indian Ocean islands (Madagascar, Réunion) predominantly in humid to sub-humid agroecosystems (Kanya et al. Reference Kanya, Ngi-Song, Sétamou, Overholt, Ochora and Osir2004; Le Rü et al. Reference Le Rü, Ong’amo, Moyal, Muchugu, Ngala, Musyoka, Abdullah, Matama-Kauma, Lada, Pallangyo, Omwega, Schulthess, Calatayud and Silvain2006a, Reference Le Rü, Ong’amo, Moyal, Ngala, Musyoka, Abdullah, Cugala, Defabachew, Haile, Matama, Lada, Negassi, Pallangyo, Ravolonandrianina, Sidumo, Omwega, Schulthess, Calatayud and Silvain2006b; Moolman et al. Reference Moolman, Van Den Berg, Conlong, Cugala, Siebert and Le Ru2014). Studies of dynamics of these species in their habitats reported the influence of altitude, temperature, humidity, and cropping systems, with seasonal fluctuations affecting their community structure (Gounou et al. Reference Gounou, Jiang and Schulthess2009; Ntirenganya et al. Reference Ntirenganya, Goftishu, Sokame, Assefa and Nsengimana2025; Régnier et al. Reference Régnier, Legrand, Calatayud and Rebaudo2023).

Phylogeographical studies have indicated that African maize stemborer, Busseola fusca, is natively adapted to higher altitudes commonly above 1500 m (Asmare et al. Reference Asmare, Emana, Ferdu and Amare2014; Calatayud et al. Reference Calatayud, Le Rü, van den Berg and Schulthess2014). With climate change and variation, this species was also observed expanding its range to mid and low altitudes of less than 1500 m in East Africa (Calatayud et al. Reference Calatayud, Le Rü, van den Berg and Schulthess2014; Goftishu et al. Reference Goftishu, Assefa, Niba and Fininsa2017; Mutamiswa et al. Reference Mutamiswa, Chidawanyika and Nyamukondiwa2017). Similarly, recent surveys conducted in Ethiopia indicated that Chilo partellus, naturally adapted to low altitude with warmer temperature, has widened its agroecological distribution to high altitude of 2084 m.a.s.l (Asmare et al. Reference Asmare, Emana, Ferdu and Amare2014; Goftishu et al. Reference Goftishu, Assefa, Niba, Fininsa and Le Ru2018). In contrast, a reasonable number of Sesamia calamistis was continuously reported across all altitudes in Ethiopia (Goftishu et al. Reference Goftishu, Assefa, Niba and Fininsa2017, Reference Goftishu, Assefa, Niba, Fininsa and Le Ru2018; Melaku et al. Reference Melaku, Schulthess, Kairu and Omwega2006; Tefera Reference Tefera2004; Wale et al. Reference Wale, Schulthess, Kairu and Omwega2007), with a relative increase in mid-altitude of most parts of East Africa (Kaçar et al. Reference Kaçar, Butrón, Kontogiannatos, Han, Peñaflor, Farinós, Huang, Hutchison, De Souza, Malvar, Kourti, Ramirez-Romero, Smith, Koca, Pineda and Haddi2023; Le Rü et al. Reference Le Rü, Ong’amo, Moyal, Muchugu, Ngala, Musyoka, Abdullah, Matama-Kauma, Lada, Pallangyo, Omwega, Schulthess, Calatayud and Silvain2006a, Reference Le Rü, Ong’amo, Moyal, Ngala, Musyoka, Abdullah, Cugala, Defabachew, Haile, Matama, Lada, Negassi, Pallangyo, Ravolonandrianina, Sidumo, Omwega, Schulthess, Calatayud and Silvain2006b).

Despite decades of research on lepidopteran stemborers, critical gaps persist in our understanding of their ecology, particularly regarding interactions with host plants, species-specific seasonal dynamics, and adaptive responses to climatic variability. Ecological role of wild vegetation surrounding farmlands remains contested. Some studies suggested the low stemborers abundance in wild habitats (Kankonda et al. Reference Kankonda, Akaibe, Ong’amo and Le Ru2017; Le Rü et al. Reference Le Rü, Ong’amo, Moyal, Muchugu, Ngala, Musyoka, Abdullah, Matama-Kauma, Lada, Pallangyo, Omwega, Schulthess, Calatayud and Silvain2006a, Reference Le Rü, Ong’amo, Moyal, Ngala, Musyoka, Abdullah, Cugala, Defabachew, Haile, Matama, Lada, Negassi, Pallangyo, Ravolonandrianina, Sidumo, Omwega, Schulthess, Calatayud and Silvain2006b; Ong’amo Reference Ong’amo2005), while others reported active crop–wild vegetation exchange that challenge traditional assumptions about stemborer habitat specialization and pest emergence (Assefa et al. Reference Assefa, Conlong, Van Den Berg and Mitchell2010; Goftishu et al. Reference Goftishu, Assefa, Niba, Fininsa and Le Ru2018; Khan et al. Reference Khan, Midega, Wadhams, Pickett and Mumuni2007; Midega et al. Reference Midega, Bruce, Pickett and Khan2015).

Emerging evidence also suggests that non-economic stemborer species may evolve into significant pests under changing land use and climatic conditions (Gounou et al. Reference Gounou, Jiang and Schulthess2009; Mutamiswa et al. Reference Mutamiswa, Chikowore, Nyamukondiwa, Mudereri, Khan and Chidawanyika2022; Régnier et al. Reference Régnier, Legrand, Calatayud and Rebaudo2023). These dynamics underscore the need for localized ecological assessments, particularly in understudied regions such as Rwanda, where information on stemborer community structure and agroecological functioning is limited. Addressing these knowledge gaps is essential for developing climate-resilient and ecologically informed pest management strategies.

This study aims to address critical gaps in the ecology of lepidopteran stemborers in Rwanda by (i) conducting the first assessment of stemborer species diversity and abundance across different altitudinal zones, (ii) evaluating seasonal variation in infestation patterns, and (iii) determining the role of wild host plants’ persistence of stemborers populations. We hypothesize that higher altitudes support fewer stemborers due to cold microclimates, while lower altitudes may exhibit higher overall richness driven by warmer temperatures and continuous cropping systems (Mutamiswa et al. Reference Mutamiswa, Chikowore, Nyamukondiwa, Mudereri, Khan and Chidawanyika2022; Mwalusepo et al. Reference Mwalusepo, Massawe, Johansson, Abdel-Rahman, Gathara, Njuguna, Calatayud, James, Landmann and Ru2018). Mid-altitude zone with moderate temperatures may facilitate co-existence of multiple stemborer species (Mwalusepo et al. Reference Mwalusepo, Tonnang, Massawe, Okuku, Khadioli, Johansson, Calatayud and Le Ru2015, Reference Mwalusepo, Massawe, Johansson, Abdel-Rahman, Gathara, Njuguna, Calatayud, James, Landmann and Ru2018).

Seasonal variation is expected to influence stemborers community dynamics by switching from maize to alternative host plants during the dry season when maize is absent (Khan et al. Reference Khan, Midega, Wadhams, Pickett and Mumuni2007; Ntiri et al. Reference Ntiri, Calatayud, Van Den Berg and Le Ru2019; Van Den Berg et al. Reference Van Den Berg, Van Rensburg and Pringle1991). Conversely, maize plantations are expected to show peak infestation levels during the long rainy season, with the availability of preferred host plants, and favourable humidity that support rapid larval development. Wild host plants such as Pennisetum purpureum (Napier grass) could serve as persistent reservoirs that sustain stemborer populations across seasons (Moolman et al. Reference Moolman, Van Den Berg, Conlong, Cugala, Siebert and Le Ru2014; Ong’amo Reference Ong’amo2005). Understanding these interactions is essential for developing climate-smart, and site-specific pest management strategies. The findings contribute to improved resilience in smallholder farming systems while supporting broader goals of biodiversity conservation and sustainable agriculture intensification.

Materials and methods

Study zones characteristics

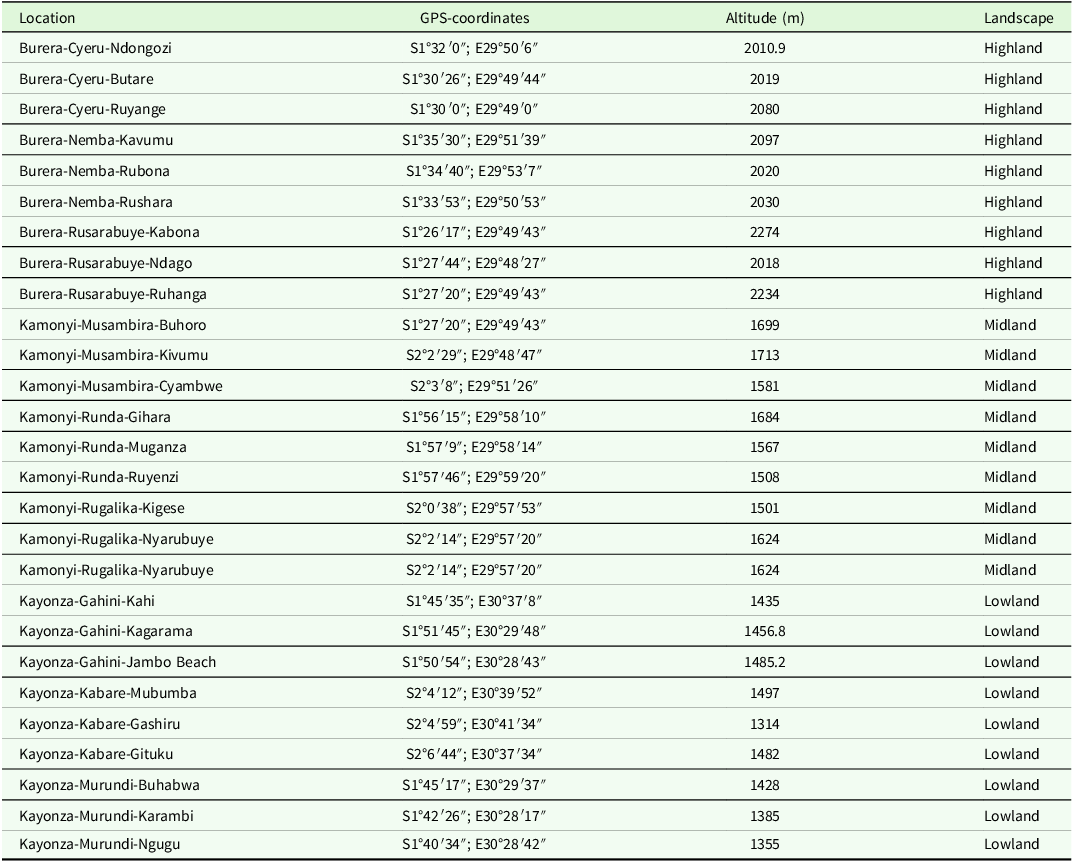

The study was conducted from 2023 to 2024 in three ecologically distinct zones of Rwanda: Eastern, Southern, and Northern provinces, each representing unique biogeographical zones and unique vegetation types (MINAGRI 2021; SANBI et al. 2022). Kayonza district (1°51′04″ S, 30°39′04″ E; ∼1324 m a.s.l.) represented eastern province. The district lies within the low altitudinal zone of Akagera sub-humid savanna region, part of the eastern savannah corridor, characterized by Cyperus papyrus, hippo grass (Vossia cuspidata), and swamp forest vegetation along floodplains and wetland valleys (Ruticumugambi et al. Reference Ruticumugambi, Kaplin, Blondeel, Mukuralinda, Ndoli, Verdoodt, Rutebuka, Imanirareba, Uwizeyimana, Gatesi, Nkurikiye, Verbeeck, Verheyen and Vancoillie2024; SANBI et al. 2022). Kamonyi district (2°00′15″ S, 29°54′19″ E; ∼1661 m a.s.l.) represented southern province. The district is located in mid altitudinal zone in montane forest region extending to the Albertine Rift, dominated by upper montane forests, and grasses (Lillesø et al. Reference Lillesø, van Breugel, Kindt, Bingham, Demissew, Dudley, Friis, Gachathi, Kalema, Mbago, Minani, Moshi, Mulumba, Namaganda, Ndangalasi, Ruffo, Jamnadass and Graudal2024; SANBI et al. 2022). Burera district (1°28′26″ S, 29°50′05″ E; ∼2182 m a.s.l.) represented northern province. The district is located in high-altitude zone encompassing Afroalpine mountain ecosystems with extensive wetlands dominated by Poaceae (Miscanthidium and Pennisetum), Typhaceae, and Cyperaceae families (Nsengimana et al. Reference Nsengimana, Rurangwa, Nsenganeza, Kayonga, Uwineza, Furaha, Niyomwungeri, Masengesho, Ruhagazi and Nsengimana2025; SANBI et al. 2022) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Map of Rwanda showing the sampling sites. The yellow colour indicates the sites located at a high-altitude zone in the northern province; the light green indicates the sampling sites at a mid-altitude zone of the southern province, the light purple colour indicates the sampling sites located at low-altitude zone of the eastern province. The map was generated from the metadata available at the Rwanda Biodiversity Information System (RBIS) using ArcGIS, 10.8.2.

Although the sampled areas of southern and central regions of Rwanda exhibit overlapping altitude ranges with parts of the eastern region due to similar geomorphological processes, they are classified into distinct altitudinal zones based on differences in elevation gradients (Table 1), vegetation structure, and microclimatic conditions (Lillesø et al. Reference Lillesø, van Breugel, Kindt, Bingham, Demissew, Dudley, Friis, Gachathi, Kalema, Mbago, Minani, Moshi, Mulumba, Namaganda, Ndangalasi, Ruffo, Jamnadass and Graudal2024; MINAGRI 2021; SANBI et al. 2022), which are key ecological factors influencing stemborers community structure (Mutamiswa et al. Reference Mutamiswa, Chikowore, Nyamukondiwa, Mudereri, Khan and Chidawanyika2022; Mwalusepo et al. Reference Mwalusepo, Massawe, Johansson, Abdel-Rahman, Gathara, Njuguna, Calatayud, James, Landmann and Ru2018; Tamiru et al. Reference Tamiru, Getu and Jembere2007).

Sampling design

Data were collected during the dry (June–August), long rainy (September–February), and short rainy (March–May) seasons in 2023 and 2024 (National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda (NISR) 2024). In each altitudinal zone, nine maize farms were selected, resulting in a total of 27 sampled farms, equally distributed across three selected sectors from representative districts. Farms were eligible for inclusion if they contained at least 0.5 hectares of maize and were separated from one another by a minimum distance of 3 km. Each farm was subdivided into five 3 m × 3 m sampling quadrants, and all maize stems within these quadrants were systematically examined for the presence of stemborer infestation. Wild vegetation was surveyed in natural habitats along the margins of maize farms, with sampling sites located within a maximum distance of 50 m from each sampled cultivated field.

Sampling was guided by a targeted selection of vegetation families known to host stemborers or closely related taxa. This purposive sampling strategy, rather than purely random selection, was adopted based on recommendations from previous studies that reported low stemborer population densities in wild vegetation (Goftishu et al. Reference Goftishu, Assefa, Niba, Fininsa and Le Ru2018; Kanya et al. Reference Kanya, Ngi-Song, Sétamou, Overholt, Ochora and Osir2004; Otieno et al. Reference Otieno, Le Ru, Ong’amo, Moyal, Dupas, Calatayud and Silvain2008). The method aimed to increase the likelihood of detecting stemborers by focusing on vegetation with higher ecological relevance to the pest.

Collection and rearing of stemborers

At each locality, both cultivated maize and farm margin’s wild vegetation were carefully checked for stemborer infestation symptoms such as wilting leaves, dry leaves, dead hearts, holes bored on stems, and fresh frass (Goftishu et al. Reference Goftishu, Assefa, Niba, Fininsa and Le Ru2018; Moeng et al. Reference Moeng, Mutamiswa, Conlong, Assefa, Le Ru, Goftishu and Nyamukondiwa2018). For wild vegetation, special consideration was given to species belonging to the Poaceae, Cyperaceae, and Typhaceae families with known records to host stemborers in cultivated and wild ecosystems (Goftishu et al. Reference Goftishu, Assefa, Niba, Fininsa and Le Ru2018; Otieno et al. Reference Otieno, Le Ru, Ong’amo, Moyal, Dupas, Calatayud and Silvain2008). Infested plants were cut, dissected, and carefully checked for the presence of stemborers. Recovered larvae were transferred to artificial diets in plastic vials (7.5 × 2.5 cm) closed with cotton and kept in the laboratory until pupation (Devi and Kaur Reference Devi and Kaur2015; Goftishu et al. Reference Goftishu, Assefa, Niba, Fininsa and Le Ru2018; Overholt et al. Reference Overholt, Maes and Goebel2001). Recovered pupae and egg colonies were kept separately in plastic vials (15 × 7 cm) closed with cotton wool until their emergence (Moeng et al. Reference Moeng, Mutamiswa, Conlong, Assefa, Le Ru, Goftishu and Nyamukondiwa2018).

Sample processing and laboratory identification

Identification of stemborers to genus and species levels was done using microscopic observations, following established morphological keys. Primary identification followed the guide for stemborers identification developed by the International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology (ICIPE) (Overholt et al. Reference Overholt, Maes and Goebel2001), the recently published Sesamia species identification key (Le Rü et al. Reference Le Rü, Hévin, Capdevielle-Dulac, Musyoka, Sezonlin, Conlong, Van Den Berg, Ndemah, Le Gall, Cugala, Nyamukondiwa, Pallangyo, Njaku, Goftishu, Assefa, Bani, Molo, Chipapika, Ong’amo, Clamens, Barbut and Kergoat2022), and the insect identification platform of Lucid Central (https://www.lucidcentral.org). To ensure taxonomic accuracy, identifications were further validated in consultation with stemborer specialists from ICIPE. Voucher specimens were deposited at the zoology laboratory, biology department, College of Science and Technology, University of Rwanda, under the stemborers collection (access code: WS2023 and WS2024).

Statistical data analysis

Stemborer communities were analysed by comparing their abundance and diversity across three altitudinal zones (low, mid, and high), seasonal conditions (dry season, long rainy season, and short rainy season), and host plant species. Abundance was quantified by counting the number of individual adult heads rather than using mean estimates. For egg colonies, each colony was considered as a single individual after adult emergence, as all individuals within a colony originated from the same oviposition event. To compare diversity across altitudes and seasons, we calculated multiple diversity indices (Shannon diversity, Simpson, and Pielou’s Evenness) and created rarefaction curves at 95% confidence intervals using bootstrap methods in iNEXT package (Morris et al. Reference Morris, Caruso, Buscot, Fischer, Hancock, Maier, Meiners, Müller, Obermaier, Prati, Socher, Sonnemann, Wäschke, Wubet, Wurst and Rillig2014). Chi‑square test was used to assess independence or differences in proportions, and when the assumptions of normality were not met, the non‑parametric Kruskal–Wallis test was applied as an alternative.

To test the influence of altitude and season on species assemblages, we performed permutation multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) and non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) to demonstrate and visualize compositional differences, providing complementary insights into community structure beyond richness alone (Hsieh et al. Reference Hsieh, Ma and Chao2016). To test whether seasonal variation reflected stemborer movement between maize and alternative hosts, we analysed community dispersion by using marginally significant permutation dispersion (PERMDISP, p = 0.055) (Anderson Reference Anderson, Kenett, Longford, Piegorsch and Ruggeri2017). All statistical data analyses were performed in R Statistics software version 4.4.0 at significance of 0.05 for all tests (R Core Team 2025).

Results

General abundance of stemborers

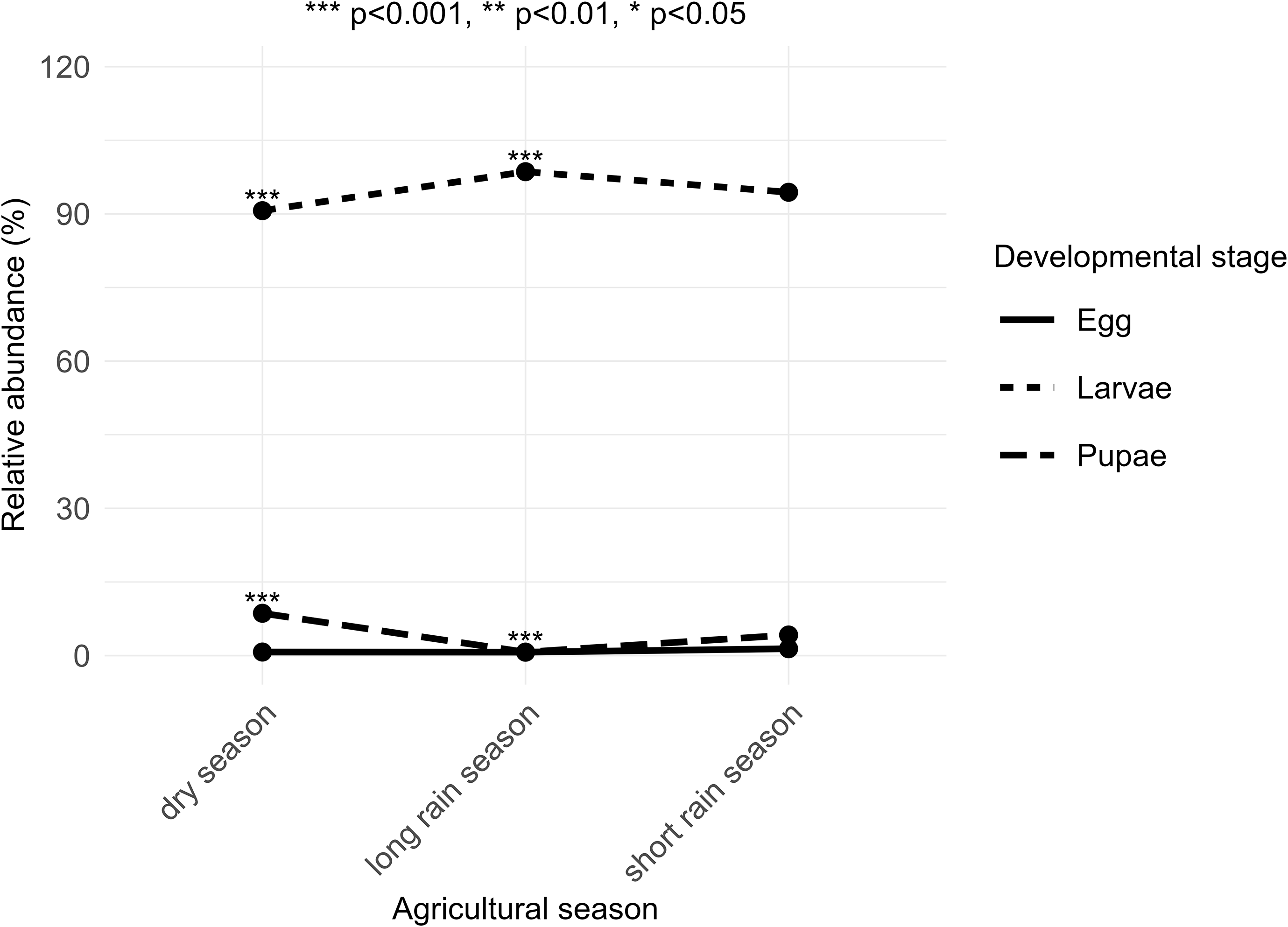

A total of 2756 stemborer individuals were collected during the study period. Of these, 2691 (97,6%) were successfully identified to species or genus levels, while 65 individuals were classified only to the family level. These unidentified individuals were included in the analyses restricted to developmental stages. Across developmental stages, the larvae were overwhelmingly abundant (n = 2604; 94.5%), followed by pupae (n = 131; 4.7%) and egg colonies (n = 21; 0.8%) (Figure 2). Species-level abundance patterns showed that Busseola fusca was the most abundant species (n = 1068; 39.68%), followed by Chilo partellus (n = 919; 34.15%), Sesamia calamistis (n = 617; 22.92%), S. nonagrioides (n = 77; 2.8%), and the least represented was Eldana saccharina (n = 9; 0.45%).

Figure 2. Relative abundance and distributions of stemborers developmental stages where ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05 show the level of significances.

Abundance varied across altitudinal zones. Higher abundance (n = 1076; 39.2%) was recorded in low altitude, followed by mid-altitude (n = 942; 34.1%) and high-altitude (n = 738; 26.7%) zones. Seasonal variations also had a notable effect: the dry season exhibited the highest abundance (n = 1302; 47.2%), compared to the long rainy season (n = 956; 34.7%) and the short rainy season (n = 498; 18.1%). The significant chi-square test (χ 2 = 67.52, df = 4, p < 0.001) confirms a strong seasonal pattern in stemborer developmental stages distribution. Larvae dominated samples during the long rainy season, whereas pupae were mainly sampled during the dry season.

Stemborers abundance across altitudinal gradients

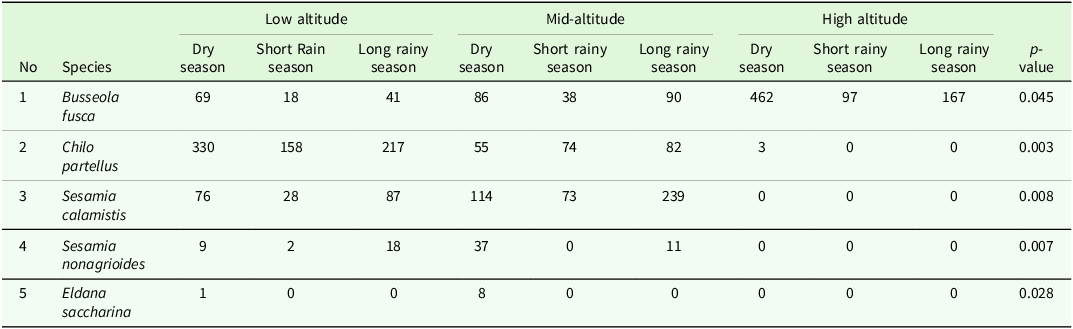

Analysis of the effect of altitude on stemborer species revealed that Busseola fusca was the most abundant species at high-altitude (n = 726; 26.97%), compared to the mid-altitude (n = 214; 7.95%) and low-altitude (n = 128; 4.75%) zones. In contrast, Chilo partellus species showed an opposite pattern with highest abundance at low altitude (n = 705; 26.2%) followed by mid-altitude (n = 211; 7.84%), and only three individuals were recorded at higher altitude zones. Sesamia sp. was the most numerous in mid-altitude (n = 474; 17.6%) compared to low altitude (n = 220; 8.17%). As expected for a species that is not strongly associated with maize cultivation, Eldana saccharina was rarely encountered, represented by eight individuals at mid-altitude and a single individual at low altitude (Table 2). Kruskal-Wallis test analysis revealed a significant difference in species distribution across the altitudinal gradients (χ² = 185.99, df = 10, p < 0.05).

Table 2. Distribution and abundance of stemborers across different altitudinal gradients (0 = Absence) where abbreviations represent genera of stemborers

Stemborers abundances across seasons

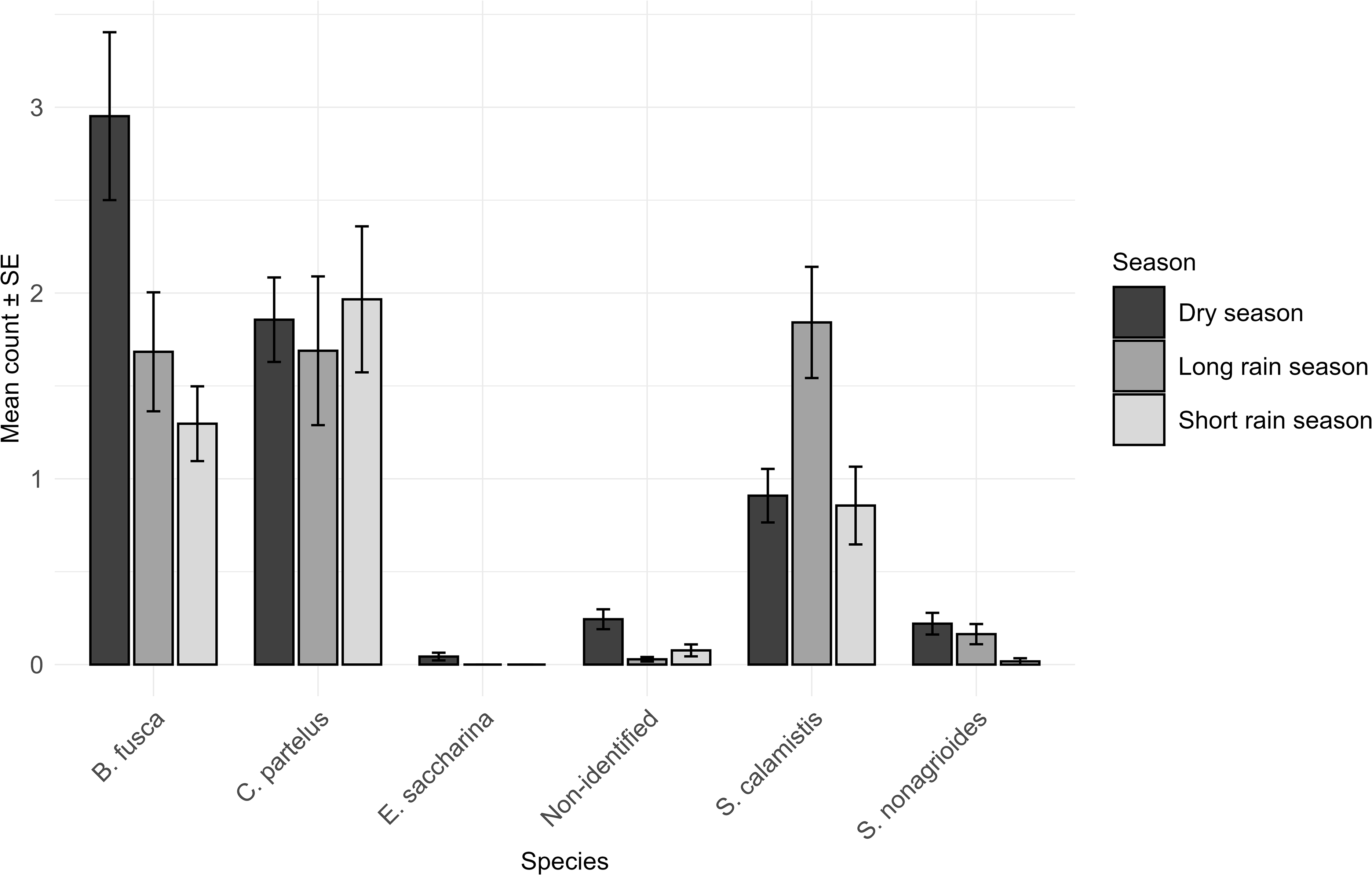

Seasonal patterns showed a clear and significant influence on stemborer abundance. Overall, dry season showed a higher number of identified stemborer individuals (n = 1251; 46.48%), followed by the long rainy season (n = 951; 35.4%) and the short rainy season (n = 498; 18.5%). Species-level responses further highlighted distinct ecological preferences. Busseola fusca peaked with 617 (49.3%) individual species during the dry season. Chilo partellus maintains relatively stable populations across dry season (n = 388; 31%) and long rain season (n = 298; 31.3%) but declines during the short rainy season (n = 153; 16%). Sesamia calamistis was abundant in long rainy season (n = 329; 34.6%). In contrast, Eldana saccharina and S. nonagrioides remain consistently low across seasons with limited association to maize plantation (Figure 3). Statistically, Kruskal-Wallis test of species abundance across agricultural seasons shows that all species exhibit a significant population variation over seasons where p-values of statistical analysis of individual species response to seasonal variation are provided in Table 2.

Figure 3. Comparative analysis of seasonal population dynamics of Stemborers where B: Busseola, C: Chilo, E: Eldana, S: Sesamia (genera names of stemborers).

Stemborers abundances across host plants

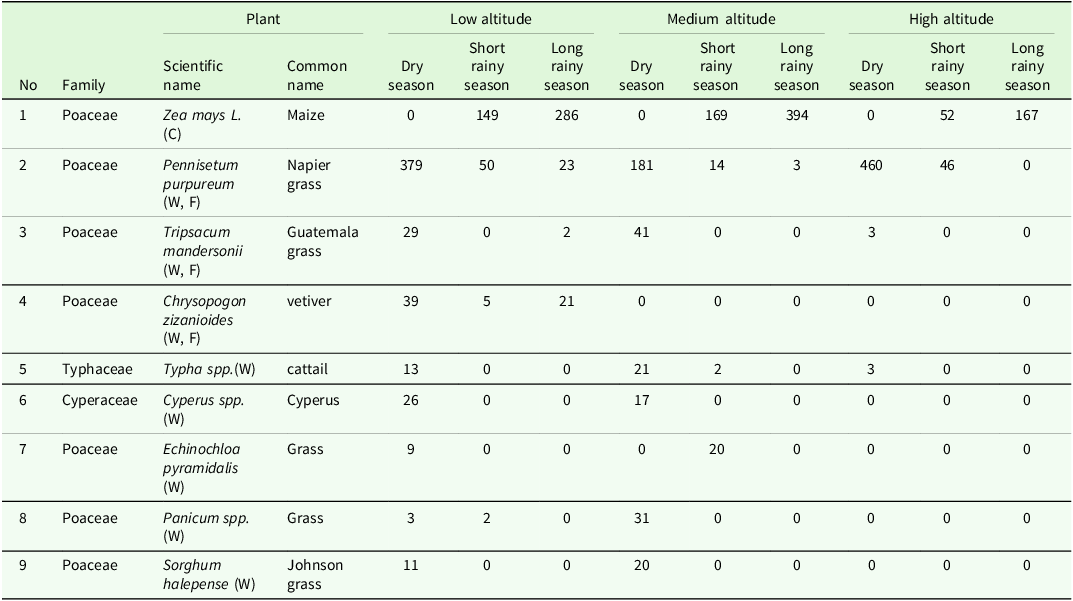

Stemborer species abundance analysis in relation to the host plants revealed nine plants serving as alternative hosts, of which seven species belong to Poaceae family, while the Cyperaceae and Typhaceae were represented by a single species (Table 3). In a total of 2691 stemborer individuals recorded, maize and Napier grass emerged as the predominant host plants (maize – 1217 individuals, 45.2%; Napier grass – 1156 individuals, 42.9%). The remaining 318 individuals (11.9%) were distributed among other wild host plants. Statistical analysis revealed a significant difference in species distribution across host plant types (χ² = 194.28, df = 14, p < 0.05). Notably, an accelerated increase in stemborer abundance on wild vegetation was observed during periods when maize was absent, particularly in high- and low-altitude zones (Table 3).

Table 3. Distribution and abundance of Stemborers by host plant across different altitudinal gradients and seasonal variations (C: Cultivated crop; F: Fodder; W: Wild; 0: Absence)

Stemborers diversity and richness

Rarefaction curves have reached asymptotes and sample coverage exceeded 95% across all assemblages, indicating adequate sampling effort to capture the majority of stemborer species present. Sample-based rarefaction confirmed a significant difference in species richness among altitudinal gradients (Figure 4a) and indicated seasonal variation as potential regulator of stemborer community structure (Figure 4b). Diversity metrics further supported these patterns. The mid-altitude zone exhibited the highest Shannon Diversity Index (H′ = 1.239), Simpson Index (D = 0.675), and Pielou’s Evenness (J′ = 0.770). In comparison, the low-altitude zone showed moderate diversity (H′ = 0.944) and evenness (J′ = 0.587). The high-altitude zone had extremely low diversity (H′ = 0.029) and evenness (J′ = 0.041). Shannon diversity declined significantly with altitude (Spearman’s ρ = −0.41, p < 0.001).

Figure 4. Rarefaction and species richness. (a) Sample-based rarefaction curve with extrapolation (dotted line segments) at 95% confidence intervals (shaded areas); (b) Altitudinal species richness in response to seasonal variations.

Altitude vs. season effects on stemborer communities

Results revealed altitude as the primary driver of community structure, explaining 16.5% of the observed variation (R² = 0.1649, F = 35.73, p < 0.001). Season also has a smaller but significant effect, accounting for 2.8% of community variation (R² = 0.0282, F = 2.61, p = 0.002). The analysis of altitude-season combined effect exhibited 21.2% of the community variation (R² = 0.1876, F = 13.78, p < 0.001) while the remaining 78.8% were attributed to unmeasured factors. Further, there was negligible shared variance between altitude and season (negligible shared variance: −0.2%).

Stemborers community structure and seasonal variation

The NMDS test indicated reliable representation of community dissimilarity patterns (Stress: 0.065, R² = 0.212, F = 9.53, p < 0.001). Environmental vector fitting assessment identified altitude as the strongest ecological driver shaping stemborers community patterns, explaining 51% of ordination variance (p < 0.001) (Figure 5a). In addition, the permutational multivariate analysis of dispersion (PERMDISP) revealed marginally significant differences in stemborer groups dispersion among seasons (F = 2.83, p = 0.055), with short rainy season, showing significantly lower dispersion (mean distance to centroid = 0.522) compared to dry season (0.577) and long rainy season (0.584) (Figure 5b). Furthermore, the assessment of host plant use has indicated seasonal host-switching. The dry season communities use seven alternative host plant species with the highest diversty (Shannon = 1.30). The rainy season, however, was characterized by high maize abundance (49–59% of samples), associated with reduced alternative host plant diversity (Shannon = 0.97–1.20).

Figure 5. Altitudinal and seasonal structures of stemborer communities. (a) Altitudinal structures of stemborer communities (R² = 0.21, p < 0.001), (b) seasonal structures of stemborer communities (F = 2.83, p = 0.055, α = 0.10).

Results have also indicated that host plant composition differed significantly among seasons (χ² = 246.74, df = 16, p < 0.001), with Pennisetum purpureum (Napier grass) serving as the primary dry season refugium sustaining 1020 stemborers across 105 samples (61% of dry season samples). Within seasons, the Bray-Curtis showed higher similarity during short rainy (0.271) compared to the long rainy (0.191). Busseola fusca was higher in dry season’s alternative hosts (49.4%) while Chilo partellus showed higher abundance during short rainy season maize plantation (47.5%).

Discussion

This study represents the first investigation of lepidopteran stemborers community in Rwanda, providing insights into species composition, distribution patterns, host associations, and seasonal switching across different agroecological zones of Rwanda. Five key stemborer species were identified, namely Busseola fusca, Sesamia calamistis, Sesamia nonagrioides (Noctuidae), Chilo partellus (Crambidae), and Eldana saccharina (Pyralidae). All these species are known for their wide distribution range and ecological adaptability in East and Southern Africa (Assefa et al. Reference Assefa, Conlong, Van Den Berg and Mitchell2010; Goftishu et al. Reference Goftishu, Assefa, Niba, Fininsa and Le Ru2018; Mutamiswa et al. Reference Mutamiswa, Chikowore, Nyamukondiwa, Mudereri, Khan and Chidawanyika2022; Overholt et al. Reference Overholt, Maes and Goebel2001). Our results showed that the larval stage was the most abundant across sites and seasons, indicating its particularly strong negative impact on cereal plants, as this is the stage that causes the greatest damage to crops (Assefa Reference Assefa2006; Goftishu et al. Reference Goftishu, Assefa, Niba and Fininsa2017; Overholt et al. Reference Overholt, Maes and Goebel2001; Sokame et al. Reference Sokame, Rebaudo, Musyoka, Obonyo, Mailafiya, Le Ru, Kilalo, Juma and Calatayud2019). Findings also demonstrated that wild vegetation plays a substantial role in sustaining stemborer populations during maize off-seasons, suggesting that non-crop habitats act as reservoirs that support the pests’ inter-seasonal persistence.

In our study, Busseola fusca was the most abundant species in the high-altitude zones but was also found in mid- and low-altitude areas, suggesting a potential expansion of its ecological niche. Sesamia spp. were concentrated in mid-altitudes, with limited presence in lowland zones, while Chilo partellus was found across both low and mid-altitudes. These patterns reflect the recent observations from Ethiopia, Kenya, Mozambique, South Africa, and the Democratic Republic of Congo, where shifts in stemborer distribution have been associated with climate change, habitats fragmentation, and resource competition (Goftishu et al. Reference Goftishu, Assefa, Niba, Fininsa and Le Ru2018; Kankonda et al. Reference Kankonda, Akaibe, Ong’amo and Le Ru2017; Le Rü et al. Reference Le Rü, Ong’amo, Moyal, Muchugu, Ngala, Musyoka, Abdullah, Matama-Kauma, Lada, Pallangyo, Omwega, Schulthess, Calatayud and Silvain2006a; Melaku et al. Reference Melaku, Schulthess, Kairu and Omwega2006; Wale et al. Reference Wale, Schulthess, Kairu and Omwega2007). The strong altitudinal structuring of stemborer communities underscores the role of altitude-dependent environmental gradients in shaping stemborers pest assemblages, consistent with broader patterns as observed in tropical herbivorous insects (Tamiru et al. Reference Tamiru, Getu and Jembere2007; Zhao et al. Reference Zhao, Gao, Liu, Liu, Li, Men and Zhang2023).

While altitude emerged as a significant driver of stemborer community structure (Mwalusepo et al. Reference Mwalusepo, Massawe, Johansson, Abdel-Rahman, Gathara, Njuguna, Calatayud, James, Landmann and Ru2018; Tamiru et al. Reference Tamiru, Getu and Jembere2007; Zhao et al. Reference Zhao, Gao, Liu, Liu, Li, Men and Zhang2023), the relatively narrow altitudinal gradient among the studied zones may have constrained the observed patterns. This limitation suggests that future research should incorporate broader elevation ranges and additional environmental variables comprising temperature, rainfall, and vegetation heterogeneity to better disentangle the effects of altitude from other ecological factors influencing stemborer distribution.

Contrary to earlier studies reporting higher stemborer abundance in cultivated cereals and limited presence in wild vegetation (Moolman et al. Reference Moolman, Van Den Berg, Conlong, Cugala, Siebert and Le Ru2014; Ong’amo Reference Ong’amo2005; Otieno et al. Reference Otieno, Le Ru, Ong’amo, Moyal, Dupas, Calatayud and Silvain2008), our data show a greater proportion in wild vegetation. This finding challenges the conventional assumption that wild grasses serve only as minor refugia during maize off-seasons (Haile and Hofsvang Reference Haile and Hofsvang2002; Moolman et al. Reference Moolman, Van Den Berg, Conlong, Cugala, Siebert and Le Ru2014; Ntirenganya et al. Reference Ntirenganya, Goftishu, Sokame, Assefa and Nsengimana2025). Instead, our results align with emerging evidence from Ethiopia, where wild grasses have been reported to support substantial stemborer populations (Goftishu et al. Reference Goftishu, Assefa, Niba, Fininsa and Le Ru2018), especially during dry periods when maize is absent (Gounou et al. Reference Gounou, Jiang and Schulthess2009). While this trend may partly reflect our purposive sampling of host-relevant plant families, as noted in the methodology, acknowledging this bias is essential to enhance transparency and strengthens the validity of ecological interpretation by distinguishing design-driven patterns from genuine biological processes (Pili et al. Reference Pili, Leroy and Zurell2025; Zvereva and Kozlov Reference Zvereva and Kozlov2019).

Seasonal host-switching patterns were also evident. During the rainy cropping season, maize plantations supported a significantly higher abundance of stemborers, while the dry season was characterized by the absence of cultivated maize, the season showed a notable shift in stemborer populations toward wild vegetation, particularly Pennisetum purpureum (Elephant/Napier grass), which harboured approximately 61% of the stemborer population P. purpureum emerged as the primary dry season refugium, harbouring approximately 61% of the stemborer population. This seasonal host-switching behaviour underscores the ecological importance of wild grasses in sustaining stemborer populations during maize off-seasons (Assefa et al. Reference Assefa, Conlong, Van Den Berg and Mitchell2010; Goftishu et al. Reference Goftishu, Assefa, Niba, Fininsa and Le Ru2018; Gounou et al. Reference Gounou, Jiang and Schulthess2009; Ong’amo Reference Ong’amo2005), suggesting that integrated pest management (IPM) strategies must consider both cultivated and wild vegetation to achieve sustainable stemborers management.

The observed dominance of stemborers, particularly Busseola fusca in Pennisetum purpureum (Napier grass) compared to maize across seasons is notable and may be explained by regional differences in Napier grass application and management. In the highland of northern province of Rwanda, Napier grass is commonly maintained to full maturity and harvested after two years for non-agronomic uses such as supporting climbing beans, constructing domestic infrastructure, and producing handcraft materials (Ayuko et al. Reference Ayuko, Lagat, Hauser, Ouko and Midamba2024; Chen et al. Reference Chen, Hein, Shi, Yang, Yang, Fu and Yang2024). In the lowland of eastern province, Napier grass is frequently harvested for livestock feed and mulching (Ayuko et al. Reference Ayuko, Lagat, Hauser, Ouko and Midamba2024; Chen et al. Reference Chen, Hein, Shi, Yang, Yang, Fu and Yang2024; Tulu et al. Reference Tulu, Gadissa, Hundessa and Kebede2023), keeping the yearly young generations in the area. These contrasting practices influence the phenological stage of the host availability to stemborers. Previous studies have shown that B. fusca exhibits a strong preference of younger Napier grass for oviposition (Assefa et al. Reference Assefa, Conlong, Van Den Berg and Martin2015; Calatayud et al. Reference Calatayud, Guénégo, Ahuya, Wanjoya, Le Rü, Silvain and Frérot2008; Khan et al. Reference Khan, Midega, Wadhams, Pickett and Mumuni2007). Therefore, the predominance of B. fusca in low altitude of eastern Rwanda may be linked to the continuous availability of younger Napier grass due to regular harvesting, creating favourable conditions for oviposition and population buildup.

Our results do not ignore other eco-socio-economic benefits of Napier grass (ICIPE 2005; Niassy et al. Reference Niassy, Agbodzavu, Mudereri, Kamalongo, Ligowe, Hailu, Kimathi, Jere, Ochatum, Pittchar, Kassie and Khan2022). The role of Pennisetum purpureum as a trap crop has been well-established within the framework of push-pull technology (ICIPE 2005; Khan et al. Reference Khan, Midega, Pittchar, Pickett and Bruce2011, Reference Khan, Midega, Wadhams, Pickett and Mumuni2007; Niassy et al. Reference Niassy, Kidoido, Mbeche, Pittchar, Hailu, Owino, Amudavi and Khan2020). When strategically planted around maize fields, it attracts ovipositing female moths, whose larvae suffer high mortality due to the grass’s physical and chemical defences, including a sticky exudate that impedes development (Abedi et al. Reference Abedi, Golizadeh, Soufbaf, Hassanpour, Jafari-Nodoushan and Akhavan2019; Calatayud et al. Reference Calatayud, Guénégo, Ahuya, Wanjoya, Le Rü, Silvain and Frérot2008; Glas et al. Reference Glas, Van Den Berg and Potting2007; Haile and Hofsvang Reference Haile and Hofsvang2002; Khan et al. Reference Khan, Midega, Wadhams, Pickett and Mumuni2007). This mechanism effectively reduces pest pressure on maize and contributes to environmentally sustainable and economically viable integrated pest management (IPM) strategies (Niassy et al. Reference Niassy, Kidoido, Mbeche, Pittchar, Hailu, Owino, Amudavi and Khan2020, Reference Niassy, Agbodzavu, Mudereri, Kamalongo, Ligowe, Hailu, Kimathi, Jere, Ochatum, Pittchar, Kassie and Khan2022). However, in East African and regional agroecosystems, fodder grasses such as Pennisetum spp., Tripsacum spp., Vetiveria spp., and Setaria spp. have historically been domesticated for livestock feed and erosion control (Ayuko et al. Reference Ayuko, Lagat, Hauser, Ouko and Midamba2024; Chen et al. Reference Chen, Hein, Shi, Yang, Yang, Fu and Yang2024; Tulu et al. Reference Tulu, Gadissa, Hundessa and Kebede2023), often without standardized spacing or integration into pest management frameworks.

However, in East African and regional agroecosystems, fodder grasses such as Pennisetum spp., Tripsacum spp., Vetiveria spp., and Setaria spp. have historically been domesticated for livestock feed and erosion control (Ayuko et al. Reference Ayuko, Lagat, Hauser, Ouko and Midamba2024; Chen et al. Reference Chen, Hein, Shi, Yang, Yang, Fu and Yang2024; Tulu et al. Reference Tulu, Gadissa, Hundessa and Kebede2023), often without standardized spacing or integration into pest management frameworks. We propose that future research should adopt a multifunctional approach to evaluate the dual role of these grasses in IPM and soil conservation, alongside improving farmers’ awareness on standard distancing/spacing between fodders and cultivated crops. Such studies are essential for redesigning sustainable push-pull or intercropping pest management strategies tailored to mountainous and terraced landscapes like Rwanda, where landslides or erosions control and pest suppression must be co-optimized.

Conclusion

This study provides the first comprehensive data on stemborer species composition and distribution across Rwanda’s agroecological zones. The findings confirm that Busseola fusca, Sesamia calamistis, Sesamia nonagrioides (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), Chilo partellus (Lepidoptera: Crambidae), and Eldana saccharina (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) are the most abundant stemborer species in wild plants. Even though altitudinal gradient and seasonal variation can independently influence stemborers community structure, our findings demonstrated that their combined effects exert a stronger and more ecologically meaningful influence on stemborer community structures. Pennisetum purpureum (Napier grass) emerged as a key alternative host, whose widespread and varied harvesting practices may contribute to stemborer persistence across different agroecological zones. Evidence of potential habitat shifts by B. fusca and C. partellus, further suggests potential niche expansion that warrants long-term monitoring under changing climatic and agricultural conditions. We recommend future research to determine the optimal spatial arrangement between crops and fodder grasses and to assess the multifunctional benefits of these grasses such as their roles in soil stabilization, erosion and landslide mitigation, and pest suppression particularly within mountainous and terraced agroecosystems common in Rwanda. Such insights will be critical for redesigning sustainable push-pull and intercropping strategies that enhance both crop productivity and ecological resilience pest management.

Acknowledgements

The authors present special recognition to the Crop Protection Program of the Rwanda Agriculture and Animal Resources Board (RAB) for transport and assistants team support; Rwanda Environmental Management Authority (REMA) for sampling and samples processing permit; The Department of Biology, School of Science in the College of Science and Technology (CST) of University Rwanda (UR) for laboratory and equipment support; The Center of Excellence in Biodiversity and Natural Resources Management (CoEB) for providing both working space and technical assistance. The authors also recognize the special contributions made by Peter Malusi (ICIPE, Nairobi, Kenya) for Stemborer sampling techniques, specimen preparation, and identification; and IDEA Wild for data collection tools provision.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: [Ntirenganya Elie, Muluken Goftishu]; Methodology: [Ntirenganya Elie, Muluken Goftishu, Venuste Nsengimana, Bonoukpoè Mawuko Sokame, Yoseph Assefa]; Formal analysis and investigation: [Ntirenganya Elie, Uwayezu Janvier]; Writing – original draft preparation: [Ntirenganya Elie]; Writing – review and editing: [Ntirenganya Elie, Muluken Goftishu]; Methodology: [Ntirenganya Elie, Muluken Goftishu, Venuste Nsengimana, Bonoukpoè Mawuko Sokame, Yoseph Assefa]; Supervision: [Muluken Goftishu, Venuste Nsengimana, Bonoukpoè Mawuko Sokame, Yoseph Assefa].

Financial support

This work was funded by the Partnership for Applied Skills in Sciences, Engineering, and Technology-Regional Scholarship and Innovation Fund (PASET-Rsif) and Carnegie Corporation of New York.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.