Introduction

Erythrocytes, also known as red blood cells (RBCs), are the most abundant type of cell in the human body, accounting for nearly 25% of the total cells in the body (Ref. Reference Bianconi, Piovesan, Facchin, Beraudi, Casadei, Frabetti, Vitale, Pelleri, Tassani and Fiva1). They are responsible for delivering oxygen to every tissue and organ and for removing carbon dioxide waste. At any moment, they are created by stem cells at an astonishing rate of ~2 × 106 per second (Ref. Reference Sackmann2), and then undergo an ageing process in circulation until the end of their lifespan, which is around 120 days (Ref. Reference Kurata, Suzuki and Agar3). At the same time, a similar number of senescent cells in the blood would go to the end of their life and be removed from the blood at the same rate as they are produced. Since erythrocytes are crucial for human life and lack nuclei and organelles when they become mature, they are considered as a good model of single-cell ageing (Ref. Reference Kaestner and Minetti4). Their ageing process is of keen scientific and clinical interest in cell research and has been attracting great concern from researchers (Refs Reference Kaestner and Minetti4–Reference Remigante, Spinelli, Straface, Gambardella, Russo, Cafeo, Caruso, Falliti, Dugo and Dossena10). However, the intriguing primary mechanism responsible for their ageing in circulation remains unclear.

Accordingly, we attempt to explore the mechanism underlying human erythrocyte ageing with a new approach. We will delve into the cell properties and membrane structure, followed by the main findings regarding the interactions of the cells with the environment, the age-related changes in the cells’ mass and energy and physical and chemical properties. We will then discuss the cellular and molecular events occurring in the erythrocyte ageing process and identify the main factors related to erythrocyte ageing from different aspects according to the incidence and strength of the interactions. With the main events as our guide and by analysing the causation and consequences of the events and their correlations, we will depict the framework of the possible pathways and mechanisms of erythrocyte ageing. Our focus is mainly on human erythrocytes in vivo ageing. Thus, unless specially denoted, all the RBCs described in this review are human erythrocytes, and the ageing is in vivo during circulation but not in vitro or blood bank storage.

Cell character of erythrocyte

RBCs, also known as erythrocytes, are generated by stem cells in response to a hormone called erythropoietin (EPO) at a rate of approximately 2 million per second (Ref. Reference Sackmann2). The kidneys produce EPO when there is a drop in blood oxygen. Unlike other cells in the human body, RBCs do not have nuclei. However, in their immature forms, RBCs do have nuclei. An intermediate form of RBC called a normoblast sheds its nuclei as the amount of haemoglobin accumulates in the developing blood cell. The RBC then progresses through various stages in the circulation, starting with a short period as a reticulocyte. During this stage, the cells lose all other cellular organelles, such as their mitochondria, Golgi apparatus and endoplasmic reticulum. Then, the cells become mature and remain so for a long period. Finally, they are senescent for a short duration (Ref. Reference d’Onofrio, Chirillo, Zini, Caenaro, Tommasi and Micciulli11). Without nuclei, RBCs do not contain DNA or RNA and cannot divide or repair themselves. They can neither reproduce nor replenish cellular machinery because of lacking organelles. Therefore, the cells cannot produce new structure or repair proteins or enzymes and their lifespan is limited to an average of 120 days. Compared with the erythrocytes of other mammals, the life span of human erythrocytes is not short. Erythrocytes in small animals such as mice and gerbil have a shorter life span (about 10–50 days) (Ref. Reference Siegel and Walton12), whereas in larger domestic species like horse and cattle, their RBCs have life spans as long as about 140–160 days (Ref. Reference Kurata, Suzuki and Agar3).

By losing their nucleus and many other organelles, RBCs attain their biconcave shape. Circulating RBCs are biconcave discoid disks, 7.8 μm in diameter and 1.8 μm in thickness, but only 1 μm thin in the middle (Refs Reference Turgeon13, Reference Huang, Wu, Mehrishi, Huang, Chen, Zheng, Liu and Luo14). The biconcave shape allows them to have a much larger surface area than a spherical cell of similar volume, which enables them to accommodate maximum space for haemoglobin and absorb oxygen more efficiently. This shape also optimizes the flow properties of blood in the large vessels, such as maximization of laminar flow and minimization of platelet scatter (Ref. Reference Uzoigwe15). Since the cells possess unique flexibility and deformability, they can squeeze through capillaries as narrow as 1.8 μm and maximize their apposing surface by assuming a cigar shape, where they efficiently release their oxygen load. However, they can resume their biconcave shape when they enter a larger vessel.

After losing its nucleus, the RBC also loses its genetic information. As a result, some argue that mature RBCs are no longer living cells. Instead, they become carriers of haemoglobin, with a plasma membrane serving as a container for haemoglobin, allowing them to transport oxygen to tissues and carbon dioxide from tissues to the lungs for elimination. However, RBCs can still produce energy (ATP) through fermentation, which involves glycolysis of glucose followed by lactic acid production. Furthermore, they can enzymatically produce nitric oxide (NO) through functional RBC-NO synthase (Ref. Reference Kleinbongard, Schulz, Rassaf, Lauer, Dejam, Jax, Kumara, Gharini, Kabanova and yaman16). Despite lacking a nucleus and any other major organelle, the internal proteins of RBC can respond to and even communicate sensitively with their environment, serving as both recipients and producers of extracellular stimuli. For example, when they undergo shear stress in constricted vessels, they release ATP and hydrogen sulphide to relax the vessel walls (Refs Reference Wan, Ristenpart and Stone17, Reference Benavides, Darley-Usmar, Mill, Patel, Isbell, Patel, Darley-Usmar, Doeller and Kraus18). When their haemoglobin molecules are deoxygenated, the cells can release S-nitrosothiols to dilate the vessels (Ref. Reference Diesen, Hess and Stamler19), and direct more blood to areas with low oxygen levels. Moreover, the cells can regulate sodium and potassium concentrations and maintain an ionic gradient between the intracellular and extracellular environments. They do this using a pumping mechanism driven by enzymes within the cell. When RBCs are lysed by pathogens such as bacteria, they release free radicals that play a role in the body’s immune response (Ref. Reference Minasyan20). Therefore, by having the mechanisms for energy metabolism and exchanging information and substances, RBCs are still justified as living cells in the conventional view. As a living cell, RBC maintains a series of cellular functions, not only the aforementioned abilities of anaerobic glycolysis, the pentose phosphate shunt and cellular signalling but also ageing and senescence.

Membrane structure and properties of erythrocyte

Molecular construction of erythrocyte membrane and candidate components for cell ageing

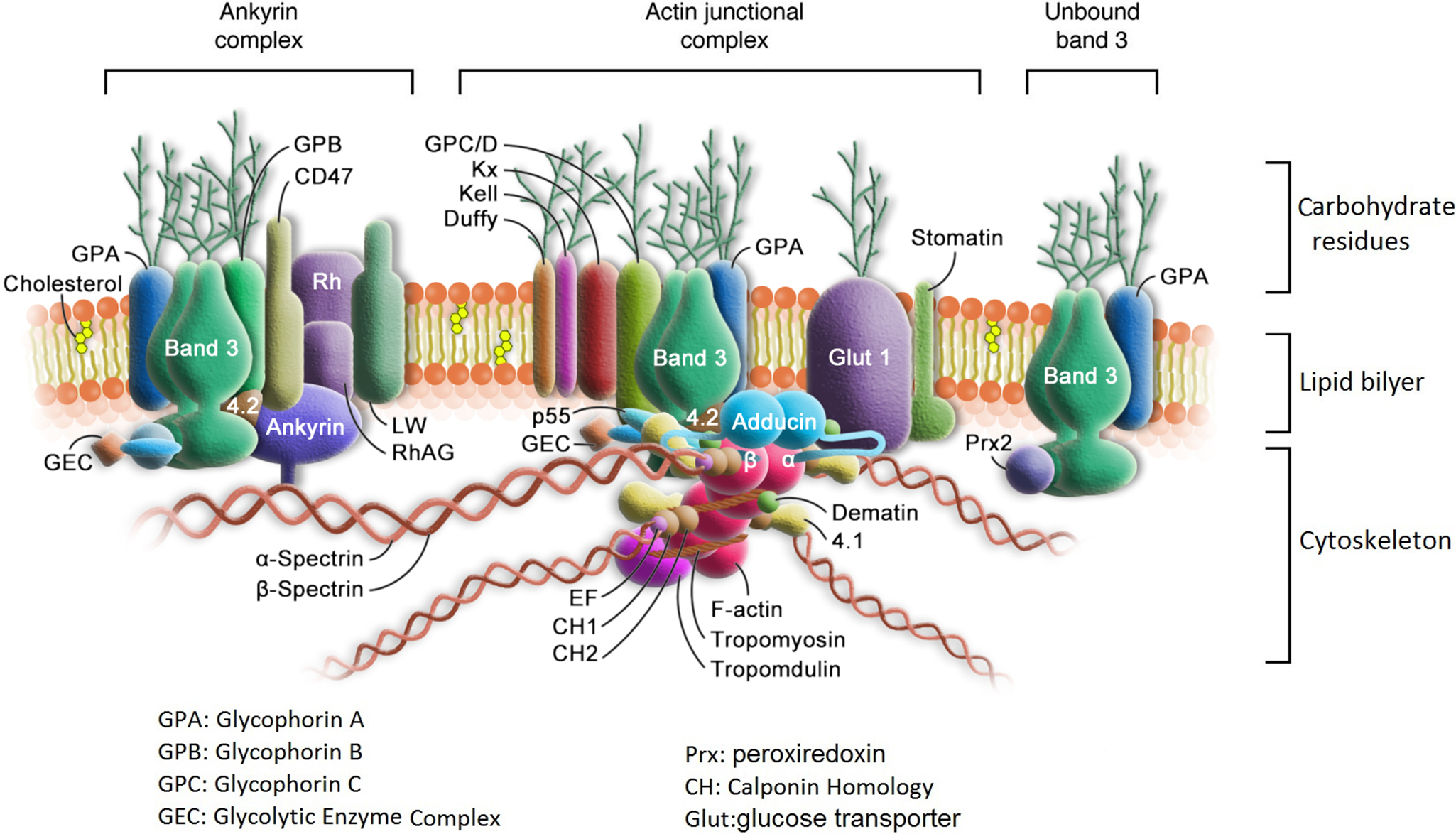

As shown in Figure 1, the erythrocyte membrane comprises two domains: a lipid bilayer and the membrane skeleton (Refs Reference Lux21, Reference Mohandas and Gallagher22). The membrane contains almost equal amounts of proteins and lipids (Ref. Reference Ballas and Krasnow23). The latter are mainly phospholipids and cholesterol. The lipid bilayer is a semipermeable, incompressible two-dimensional liquid crystal that is asymmetric in composition and serves as a boundary with a surface area of about 140 μm2 to separate the cytoplasm in the cell from the extracellular medium (Ref. Reference Ballas and Krasnow23). Glycolipids, phosphatidylcholine (PC) and sphingomyelin are more abundant in the extracellular surface, while phosphatidylinositols, phosphatidylserines (PS) and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) are dominant on the inner leaflet of the lipid bilayer. Cholesterol is intercalated among the phospholipid molecules and distributed between the two leaflets of the bilayer. Changes in the membrane molecular construction and distribution, such as exposure of the internal amino phospholipids to the plasma, alterations in the molar ratio of cholesterol to phospholipid and the PC–sphingomyelin ratio, are at all times correlated with functional changes or even severe consequences of the cell.

Figure 1. Structure of erythrocyte membrane.

Membrane proteins have an asymmetric orientation within the lipid bilayer and can be categorized into three functional sets: structural proteins in the internal hydrophilic portion, catalytic proteins in the membrane-spanning hydrophobic portion and receptor proteins with attached carbohydrates in the external hydrophilic portion. Spectrin and actin are the main structural proteins. Together with protein 4.1, they form a filamentous network under the lipid bilayer. This network is responsible for the viscoelastic property of the erythrocyte membrane to maintain the erythrocyte shape, flexibility and lipid organization. Band 3 is a glycoprotein that exists in a dimer/tetramer equilibrium. It is the major transmembrane protein that works as a multispanning ion transport channel and is responsible for the transport of water and anions. It is also a carrier of the blood group I antigen. Glycophorins are the major receptor membrane polypeptides that have a single-spanning alpha helix and contribute the major portion of glycosylation at the extracellular domain. They are rich in sialic acid, a component of carbohydrates, which gives the RBCs a very hydrophilic-charged coat. This coat affects the immune reactions, apoptosis, receptor function, growth and cell ageing. Glycophorin A (GPA) is the major sialoglycoprotein of the human red cell and is partially associated with band 3. Together with Glycophorin B, it bears the antigenic determinants for the MN and Ss blood groups. At least 35–40 enzymes are confined to the erythrocyte membrane and play a vital role in maintaining the regular structure and function of the cell (Ref. Reference Ballas and Krasnow23).

Biophysical properties of the membrane

As previously described, the erythrocyte membrane is composed of a lipid bilayer and the membrane-skeleton. The membrane-skeleton cooperates with the integral proteins and the bilayer lipids to maintain the erythrocyte shape, flexibility and lipid organization (Refs Reference Lux21, Reference Mohandas and Gallagher22). The plasma membrane envelope is anchored to the membrane-skeleton by tethering sites on cytoplasmic domains of transmembrane proteins in the lipid bilayer. The individual membrane phospholipid molecules in the intact membrane are always in a dynamic state and can move along the lateral plane of the bilayer at a significant rate. Therefore, the lipid bilayer is of fluidity, which is determined by various factors, including the molar ratio of cholesterol to phospholipid, the degree of unsaturation of phospholipid acyl chains and the PC–sphingomyelin ratio.

Although the lipid bilayer is purely viscous, due to the spectrin-based skeletal network, the membrane achieves its elasticity from the unfolding and refolding of distinct spectrin repeats, thus having viscoelastic properties. On the other hand, the spectrin dimer–dimer interaction and the spectrin–actin protein 4.1R junctional complex play significant roles in regulating the membrane mechanical stability and preventing deformation-induced membrane fragmentation when the cell experiences high fluid shear stresses in circulation. Additionally, the binding of spectrin to PS further enhances the membrane’s mechanical stability. At the same time, the membrane mechanical function is also adjusted by the interactions of PS and phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate with skeletal proteins, spectrin and protein 4.1. With such a composite structure, the erythrocyte membrane exhibits unique material properties. It is highly elastic (100-fold softer than a latex membrane of comparable thickness), stronger than steel in terms of structural resistance and can rapidly respond to applied fluid stresses with time constants in the range of 100 ms (Ref. Reference Mohandas and Gallagher22).

The apparent viscoelastic property of the erythrocyte membrane is its deformability (Ref. Reference Chien24). Deformability refers to the ability of erythrocytes to change shape under a given applied stress without haemolysis and then revert to their normal biconcave-discoid shape when the applied deforming force is removed. This deformability is a unique feature of mammalian erythrocytes, as no other cells in mammalian organisms possess comparable deformability. Non-mammalian erythrocytes are not deformable to an extent comparable with mammalian erythrocytes. Besides the viscoelastic properties of erythrocyte membrane, deformability is also determined by the geometry of erythrocytes (Ref. Reference Huang, Wu, Mehrishi, Huang, Chen, Zheng, Liu and Luo14). The biconcave-discoid shape of erythrocytes provides an extra surface area for the cell, which enables shape change without increasing the surface area. Additionally, intracellular viscosity or the cytoplasmic haemoglobin concentration also contributes to deformability.

The membrane of erythrocytes not only confers their viscoelastic behaviour but also affects their electrokinetic behaviour. That is because the sialylated glycoproteins on the membrane’s surface create a negatively charged surface, which produces a repulsive electric zeta potential between cells. Sialic acid is a nine-carbon sugar typically found as the outermost unit of glycan chains in cell surface glycoproteins and glycolipids (Refs Reference Traving and Schauer25, Reference Angata and Varki26). These molecules account for 74–94% of the negative surface charge of the erythrocyte membrane (Ref. Reference Eylar, Madoff, Brody and Oncley27). The charge carried by sialic acids and other ionizable chemical groups provides a significant component of negative charge repulsion between cells. It helps to prevent agglutination between erythrocytes and other cells, such as endothelial cells, during circulation. Sialic acids also play a significant role in various molecular and cellular interactions that affect immune reactions, apoptosis, receptor function, growth, differentiation and ageing (Refs Reference Huang, Wu, Mehrishi, Huang, Chen, Zheng, Liu and Luo14, Reference Schauer28, Reference Seaman and DMacN29). They govern the morphology, membrane deformability, oxygenation capacity and even the structure and distribution of the intracellular haemoglobin (Hb) molecules in human erythrocytes (Refs Reference Huang, Wu, Mehrishi, Huang, Chen, Zheng, Liu and Luo14, Reference Huang, Tuo, Wang, Kang, Chen and Luo30, Reference Durocher, Payne and Conrad31).

Interactions of erythrocytes with environment

During their 120-day lifespan, erythrocytes travel approximately 240 km, experiencing constant mechanical stresses. The most common of these stresses are shear stress from blood flow and aspiration stress when the cells compress through narrow capillaries. The repeated shear stress during blood flow affects the cell membrane’s surface tension, causes a decline in its mechanical properties, such as deformability and fragility (Ref. Reference Tarasev, Chakraborty, Light and Davenport32) and even makes the membrane become mechanically compromised or suffer from fatigue fractures (Ref. Reference Yasuda, Funakubo, Miyawaki, Kawamura, Higami and Fukui33). Apart from mechanical interactions, erythrocytes interact with numerous other cells in the bloodstream, such as leukocytes, platelets and vascular endothelial cells, as well as various molecules and electrolytes, in different ways of physical and chemical interactions.

Erythrocytes are sensitive to their environment and can communicate with and respond to it. They act as both the recipients and producers of extracellular stimuli. The components of the cell that engage in signalling with other cell types include NO, ATP/ADP, adenosine, CD47, complement receptors, cytokine receptors and a wide variety of ectoenzymes. These ectoenzymes include endothelin endopeptidase 11, cyclic ADP ribose hydrolase, adenosine deaminase and acetylcholinesterase (Ref. Reference Chu, McKenna, Krump, Zheng, Mendelsohn, Thein, Garrett, Bodine and Low34).

The erythrocyte membrane is freely permeable to water, oxygen, carbon dioxide, glucose, urea and several other substances, but it does not allow haemoglobin to pass through. Some proteins in the cell membrane are responsible for transporting substances in and out of the cell in response to the environment (Ref. Reference Mohandas and Gallagher22). These proteins include band-3 protein, which is responsible for anion transport; aquaporin, which facilitates water transport; Glut1, which helps with glucose and l-dehydroascorbic acid transport; Kidd antigen protein, which aids in urea transport; RhAG, which assists in gas transport, specifically of carbon dioxide. Additionally, other proteins, such as Na+-K+-ATPase, Ca++ ATPase, Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter, Na+-Cl− cotransporter, Na+-K+ cotransporter, Na+-Cl− cotransporter and Gardos channel, help in transporting substances in and out of the cell. Other membrane proteins that perform an adhesive function include ICAM-4, which interacts with integrins, and Lu, the laminin-binding protein. Enzymes within the cell drive a pumping mechanism that maintains the concentrations of the cell’s substances, such as sodium and potassium.

However, during circulation, the most important role in the interaction of erythrocytes with other cell types and environmental factors (such as polycations) is played by its sialic acids. As terminal components of glycoproteins and glycolipids on the outermost surface of the cell and by having their electronegative nature accompanied by their bulky, hydrophilic chemical structure, sialic acids are exposed to the cellular environment playing the roles of intrinsic and extrinsic communication and defence.

Sialic acid is one of the main physicochemical drivers of various molecular and cellular interactions that affect erythrocytes’ immune reactions, apoptosis, receptor function, growth and ageing (Refs Reference Huang, Wu, Mehrishi, Huang, Chen, Zheng, Liu and Luo14, Reference Schauer28) (Ref. Reference Seaman and DMacN29). Sialic acids provide high charge density (~107 electron charges/144 μm2) (Refs Reference Seaman and DMacN29, Reference Mehrishi35, Reference Huang, Zheng, Kang, Chen, Liu, Huang and Wu36) on the membrane of erythrocyte. The charges and the induced zeta potential keep the erythrocytes apart from high charge-bearing monocyte-subsets or macrophages (Refs Reference Passlick, Flieger and Ziegler-Heitbrock37–Reference Varol, Yona and Jung39). They also prevent aggregation between erythrocytes (Refs Reference Simmonds, Meiselman and Baskurt7, Reference Huang, Tuo, Wang, Kang, Chen and Luo30) and with the other cells to influence the cell–cell affinity and cellular adhesiveness of RBCs, thus determining whether the cells would flow separately with each other or aggregate as rouleaux or rosettes (Refs Reference Simmonds, Meiselman and Baskurt7, Reference Huang, Tuo, Wang, Kang, Chen and Luo30, Reference Jan and Simchon40, Reference Ermolinskiy, Lugovtsov, Yaya, Lee, Kaestner, Wagner and Priezzhev41), or adhere to vascular endothelium in circulation (Ref. Reference Varki and Gagneux42).

Besides the effects of their electric charges, sialic acids also manage the cell’s morphology and membrane deformability and affect the structure and oxygenation capacity as well as the distribution of intracellular haemoglobin molecules (Ref. Reference Durocher, Payne and Conrad31) (Refs Reference Huang, Wu, Mehrishi, Huang, Chen, Zheng, Liu and Luo14, Reference Huang, Tuo, Wang, Kang, Chen and Luo30). They play the role of molecular frontier in the cell’s interaction with environments. On the one hand, by shielding recognition sites such as glycans and other receptor molecules of the cell membrane, they act as a biological mask or anti-recognition agent. On the other hand, they are biological recognition sites for a great number of molecules, such as hormones, lectins, antibodies and inorganic cations (Ref. Reference Schauer28). Therefore, sialic acids alter the biophysical properties of cellular interactions and govern the interactions (Refs Reference Huang, Wu, Mehrishi, Huang, Chen, Zheng, Liu and Luo14, Reference Seaman and DMacN29, Reference Mehrishi35, Reference Abramson43).

The oxidative reaction is another crucial interaction of erythrocytes with the environment, for erythrocytes are constantly exposed to endogenous and exogenous reactive oxygen species (ROS) during circulation. On the one hand, the cells can take up ROS in the plasma released from neutrophils, macrophages and endothelial cells in microcirculation. On the other hand, they continuously generate endogenous ROS by the slow autoxidation of their Hbs and by some other oxidases (Refs Reference Mohanty, Nagababu and Rifkind44, Reference Orrico, Laurance, Lopez, Lefevre, Thomson, Möller and Ostuni45).

The primary targets of various reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in erythrocytes are the proteins and lipids of the erythrocyte membrane, as well as the intracellular haemoglobin. These reactions result in changes in the structure of proteins and lipids in the membrane, increased cross-linking among membrane skeletal and integral proteins, lipid peroxidation, oxidation of amino acid residue side chains, formation of protein–protein cross-linkages and oxidation of the protein backbone, leading to protein fragmentation (Refs Reference Berlett and Stadtman46, Reference Qiang, Liu, Dao and Du47).

Among these, Band 3 proteins (B3p) are the most abundant RBC membrane proteins and serve as the major link between the cytoskeleton and the lipid bilayer, playing essential roles for erythrocytes. Therefore, the impact of oxidative stress on these proteins is critical. When exposed to oxidative stress caused by ROS, RBCs rapidly react through intense Tyr phosphorylation at the cytoplasmic domain of band 3 (Refs Reference Minetti, Mallozzi and AMMD48, Reference Mladenov, Gokik, Hadzi-, Gjorgoski and Jankulovski49). Phosphorylation of band 3 on the erythrocyte membrane reduces binding to anchor proteins, increases the mobility of band 3 and its phosphorylation and promotes the dissociation of band 3 from anchor proteins and its aggregation (Ref. Reference Yang, Chen, Li, Liu and Wang50), which seriously damages the stability of the skeleton network and reduces the deformability of erythrocytes.

Oxidative stress likewise causes sialic acid decomposition from erythrocyte membrane (Ref. Reference Mehdi, Singh and Rizvi51). It was reported that oxidative stress strongly affected GPA, a major sialoglycoprotein of the human erythrocyte membrane (Ref. Reference Hadengue, Del-Pino, Simon and Levenson52). The sialic acid content of the glycoproteins is decreased with oxidative stress (Ref. Reference Cho, Christine, Malicdan, Miyakawa, Nonaka, Nishino and Noguchi53). For ROS would specifically cleave the terminal sialic acid residues of the glycoproteins (Ref. Reference Rajendiran, Lakshamanappa, Zachariah and Nambiar54), thus leading to detachment and degradation of sialic acids from the RBC membrane (Ref. Reference Shahvali, Shahesmaeili, Sanjari and Karami-Mohajeri55).

As mentioned in ‘Cell character of erythrocyte’ section, an erythrocyte is a sack of haemoglobin. Haemoglobin accounts for about 96% of the RBCs’ dry content and about one-third of the total content. Hb is the prime target of oxidative attack during circulation. Since the binding of oxygen to Hb leads to a charge migration from the heme iron to the oxygen, oxy-Hb would slowly auto-oxidize to metHb at a rate of ~0.5–3% per day, with around 1% of haemoglobin being in this form at any one time (Refs Reference Umbreit56, Reference Welbourna, Wilsona, Yusofb, Metodieva and Cooper57). Besides metHb, O2-, the second product of Hb autoxidation, is also an ROS. Under normal circumstances, erythrocytes possess an efficient enzymatic machinery to protect against ROS damage through their endogenous antioxidants, such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase, glutathione peroxidase (GPx) and pentose phosphate cycle enzymes (Refs Reference Bartosz8, Reference Takeuchi, Shishino, Bando, Murase, Go and Uchida58). However, in certain conditions, such as cell senescence, changes in the cell reducing power (e.g., the depletion of endogenous antioxidants), hypoxia and erythrocyte pathologies, the rate of Hb autoxidation is promoted (Ref. Reference Kanias and Acker59). As a result, the oxidative interactions initiated by haemoglobin autoxidation with the cell membrane become particularly significant under these circumstances. Moreover, during the human ageing process, the increased circulating chronic inflammation and oxidative stress caused by ageing tend to decline the activity of the aforementioned key antioxidant enzymes and some nonenzymatic antioxidants, such as glutathione (GSH) and vitamin C. It can accelerate RBC membrane lipid peroxidation and protein autoxidation. Therefore, the RBCs in elderly individuals age more rapidly and have a shorter life span (Refs Reference Yadav, Deepika and Maurya60, Reference Kyriacou and Shibeeb61).

All the interactions mentioned above can induce time-dependent structural and molecular changes in the cell to varying degrees and in different ways. The type and intensity of these interactions also change over the life span of the erythrocytes, depending on variations in their environment. As mentioned above, human ageing and chronic health problems would increase oxidative stress on the RBCs in circulation. In contrast, nutritional, pharmacological and antioxidant interventions, as well as exercise and physical activity, can improve the environmental antioxidant conditions for the cells. For instance, adopting antioxidant-rich diets can help reduce oxidative stress in RBCs by elevating catalase (CAT) expression, decreasing ROS production, improving ATPase activity and increasing 2,3-DPG levels in the cells (Refs Reference Spinelli, Straface, Gambardella, Caruso, Falliti, Remigante, Marino and Morabito62–Reference Remigante, Spinelli, Basile, Caruso, Falliti, Dossena, Marino and Morabito64). Physical activity can also enhance RBC resilience to oxidative stress through upregulated antioxidant defence mechanisms (Ref. Reference Mairbäurl65).

Physical and chemical changes during ageing

As described in the last section, because of the interactions with the environment, matured erythrocytes experience tremendous physical and chemical stress every moment during their life span in circulation, thereby progressively undergoing a series of changes with age.

The changes are not only in mass and energy but also in physical and chemical properties. As aforementioned, mature erythrocytes, lacking nuclei and organelles, cannot generate new structural or repair proteins and enzymes. Consequently, their components decrease with time. The most massive substance change in the cell components is its outermost surface membrane carbohydrate components. As erythrocytes squeeze through narrow capillaries, some of their surface sialic acids and other carbohydrates are sheared off. The increased oxidative stress during ageing also promotes the decomposition of sialic acid from the cell membrane (Ref. Reference Alves-Rosa, Tayler and Spadafora66), so the amount of membrane sialic acid in an old erythrocyte aged from 90 to 120 days is 20–30% less than that of a young cell (Ref. Reference Huang, Wu, Mehrishi, Huang, Chen, Zheng, Liu and Luo14). For the cells stored in blood bank condition, the reduction in sialic acid content can be as high as 47% after 21 days due to acidification of the storage solution (Ref. Reference Tuo, Wang, Liang and Huang67). As surface sialic acid is lost, the surface charges/zeta potential of erythrocytes decrease by 20–30% when the cell becomes senescent (Refs Reference Huang, Wu, Mehrishi, Huang, Chen, Zheng, Liu and Luo14, Reference Huang, Zheng, Kang, Chen, Liu, Huang and Wu36, Reference Tuo, Wang, Liang and Huang67–Reference Danon and Marikovsky69).

At the same time, there are also some subtle changes in cholesterol, phospholipids and in the content of linoleic acid residues and arachidonic acid residues of the membrane (Refs Reference Winterbourn and Batt70, Reference Gastel, Berg, Gier and Deenen71). For the intracellular substances, about 20% of haemoglobin is lost from circulating erythrocytes (Ref. Reference Willekens, Roerdinkholder-Stoelwinder, Groenen-Döpp, Bos, Bosman, Bos, Verkleij and Werre72). There is a loss of potassium (Ref. Reference Lew, Daw, Etzion, Tiffert, Muoma, Vanagas and Bookchin73) while the Na+ content increases. The changes in intracellular electrolyte content are not balanced, for the K+ loss is higher than the Na+ gain. The net electrolyte content decrease brings about osmotic water loss during cell ageing and induces a decline in the transmembrane electric potential, thus further influencing the membrane’s passive permeability and active transport (Ref. Reference Grzelinska and Bortosz74). The membrane transport rates for both electrolytes and glucose, therefore, decrease.

The activities of multiple enzymes, such as Na+-K+-ATPpase, Ca++-ATPpase, declined with cell age too. The decreases of these enzyme activities and the intracellular ATP as well as 2,3-DPG level in old cells (Refs Reference Huang, Tuo, Wang, Kang, Chen and Luo30, Reference Tuo, Wang, Liang and Huang67) due to the effect of metabolism and oxidative stress suggest that the cells are losing some of their energy and oxygen releasing capability during ageing. Meanwhile, the activities of the protective enzymes against ROS also decrease (Ref. Reference Ogiso, Iwaki, Takagi, Hirai and Kashiyama75). The protective enzymes include SOD, catalase GPx and pentose phosphate cycle enzymes (Ref. Reference Bartosz8). The concentrations of low-molecular-weight ROS scavengers such as reduced glutathione and tocopherol also decrease in aged erythrocytes. Therefore, the defensive capabilities of the cell against ROS are impaired with time.

In detail information, alterations in membrane structure and composition during erythrocyte ageing include:

Membrane structural alternations induced by sialic acid loss or desialylation

As aforementioned, sialic acid decreases with cell ageing due to the actions of shear stress and oxidative stress. This loss leads to topological structural changes in the membrane. On the one hand, it induces exposure of d-galactosyl residues (Ref. Reference Dhermy, Simeon, Wautier, Boivin and Wautier76), the possible recognition signals by which senescent erythrocytes may be sequestered by reticuloendothelial macrophages; on the other hand, it leads to a decrease in the ability of mucin to protect against oxidants, which function as hydroxyl radical scavengers (Ref. Reference Ogasawara, Namai, Yoshino, Lee and Ishii77).

Formation of band 3 clusters

Multiple machineries induce the formation of band 3 cluster: loss of sialic acid carboxyl-related charge not only induces the conformation and aggregation status changes of band 3 proteins but also affects the distribution of the proteins and the intracellular Hb molecules (Refs Reference Huang, Wu, Mehrishi, Huang, Chen, Zheng, Liu and Luo14, Reference Kang, Huang, Liu, Zheng, Wu and Luo78); the oxidative denaturation of Hb produces inactive haemoglobin aggregates and promotes band 3 clusters due to the binding of hemichromes to the cytoplasmic domain of band 3 (Ref. Reference Mannu, Arese, Cappellini, Fiorelli, Cappadoro and Tuuuini79). During cell ageing, band 3 molecules lose their ability to bind ankyrin as a consequence of the oxidation of cysteine 201 or cysteine 317 (Ref. Reference Thevenin, Willardson and Low80), which cause destabilization of band 3-cytoskeleton interaction then further facilitates their clustering.

Formation of microvesiculation and loss of membrane asymmetry

The modification and breakdown of band 3 proteins lead to the lateral diffusion of band 3 fragments and their aggregation, disturb the lipid organization and affect the lipid fluidity by loss of lipid anchorage, thus increasing the membrane curvature and thereby inducing vesiculation (Refs Reference Huttner and Zimmerberg81–Reference Yastrebova, Vyacheslav, Nekrasov, Gilev, Strokotov, Chernyshev, Karpenko and Maltsev83). By the effect of cell vesiculation and oxidative stress, PS is exposed on the extracellular surface, and the asymmetry of membrane lipids decreases (Refs Reference Shiga, Maeda, Suda, Kon and Sekiya84–Reference Goia, Cazzolab, Tringalia, Massaccesia, Volpeb, Rondanellic, Ferraric, Herreraa, Cestarob and Lombardoa86).

Caspase 3 activation

Under oxidative stress, caspase 3 is activated in the lipid raft membrane micro-domain (Ref. Reference Manda, Baudin-Creuza, Bhattacharyya, Pathak, Delaunay, Kundu and Basu87), thus leading to some serious consequences, such as band 3 degradation (Ref. Reference Miki, Tazawa, Hirano, Matsushima, Kumamoto, Hamasaki, Yamaguchi and Beppu88), uncoupling of the bilayer from the underlying spectrin-based skeleton, PS externalization (Ref. Reference Mandal, Moitra, Saha and Basu89) and modulation of glucose metabolism.

4.1a/4.1b ratio increases

As shown in Figure 1, band 4.1 protein is a key component of the cytoskeletal network in human erythrocytes. It enhances this network by forming a stable ternary complex with spectrin and actin, anchoring these skeletal proteins to the lipid bilayer or to intrinsic membrane proteins, such as B3p and glycophorin. Band 4.1 protein consists of two polypeptides, known as 4.1a and 4.1b, with apparent molecular weights of 78 and 80 kD, respectively. The difference in molecular weight arises from the deamidation of asparagine 502 to aspartate during cell ageing. Both 4.1a and 4.1b are phosphoproteins that bind directly to spectrin (Ref. Reference Inaba, Gupta, Kuwabara, Takahashi, B. and Maede90). They share a close relationship in their primary structure and function. As cells age, more band 4.1b proteins are converted to 4.1a through post-translational deamidation (Ref. Reference Mueller, Jackson, Dockter and Morrison91). This process is likely induced by oxidative stress (Ref. Reference Ingrosso, D’Angelo, Carlo, Perna, Zappia and Galletti92) caused by the products of Hb oxidative denaturation. Although the functional consequences of the deamidation of protein 4.1b to 4.1a are not yet clear, the ratio between 4.1a and 4.1b increases with the cell age and serves as an index of erythrocyte ageing.

Cell-bound immunoglobulins increase and CD47 decreases

More cell-bound immunoglobulins (Ig) progressively accumulate on the cell surface mainly because of band 3 clustering, which is triggered by the binding of denatured haemoglobin to the cytoplasmic domain of the protein (Refs Reference Kay93, Reference Magnani, Papa, Rossi, Vítale, Fornaíni and Manzoli94). Senescent erythrocytes have more than 10-fold enrichment of surface-bound IgG over young cells (Refs Reference Lutz and Stringaro-Wipf95–Reference Badior and Casey97). Meanwhile, CD47 undergoes a conformational change that switches the molecule from an inhibitory signal into an activating one by the effects of oxidative stress and the conformation change of band 3 complex so that less active CD47 are expressed in aged erythrocytes to perform their function of anti-phagocytosis (Refs Reference Oldenborg, Zheleznyak, Fang, Lagenaur, Gresham and Lindberg98, Reference Burger, Hilarius-Stokman, Korte, Berg and Bruggen99).

There are also a variety of changes in physical properties. Cell deformability, cell size and the area-to-volume ratio decrease (Refs Reference Huang, Wu, Mehrishi, Huang, Chen, Zheng, Liu and Luo14, Reference Huang, Tuo, Wang, Kang, Chen and Luo30), while cell density, cell fragility and the viscosity of Hb solution increase (Refs Reference Huang, Wu, Mehrishi, Huang, Chen, Zheng, Liu and Luo14, Reference Chien24, Reference Huang, Tuo, Wang, Kang, Chen and Luo30, Reference Lutz, Stammler, Fasler, Ingold and Fehr100–Reference Huang102). Old cel1s are more likely to aggregate with each other to form rouleaux or rosettes and adhere to endothelial cel1s (Refs Reference Ermolinskiy, Lugovtsov, Yaya, Lee, Kaestner, Wagner and Priezzhev41, Reference Tuo, Wang, Liang and Huang67, Reference Baskurt and Meiselman103). Some cells transform their regular biconcave disk shape to spherocyte and reduce their stability because of losing band 3 content (Refs Reference Huang, Wu, Mehrishi, Huang, Chen, Zheng, Liu and Luo14, Reference Tuo, Wang, Liang and Huang67). These property changes probably are induced by several factors simultaneously in several parallel pathways. We will discuss it in detail in the next section.

Cellular behaviours and molecular mechanism of erythrocyte ageing

In ‘Physical and chemical changes during aging’ section, we have outlined the age-dependent changes in erythrocytes. Most of these changes are adverse, including decreases in mass, energy and physical and chemical properties. Mature erythrocytes cannot synthesize new proteins, so no more components appear. Instead, existing molecules decrease or change their molecular construction/conformation and distribution during ageing. Therefore, all the changes, such as metabolic activity decline, cell shape transformation, lower deformability, membrane remodelling, oxidative injury, microvesiculation and exposure of surface recognition markers, must result from modifications in the existing molecules. They are likely induced by several factors and come from various signalling pathways due to different interactions between erythrocytes and the environment (Ref. Reference Antonelou, Kriebardis and Papassideri5). However, the interactions of erythrocytes with the environment and the induced age-related alterations described in the last two sections have provided information about the factors influencing erythrocyte ageing and some insight into the molecular mechanisms associated with ageing. Therefore, by analysing the incidence and strength of the interactions, the magnitude of induced age-related alterations, and their influence on cell ageing, we can identify the critical factors in erythrocyte ageing. With these factors as the mainline to track the sequence of the induced events to understand the primary and the secondary causes, we may be able to elucidate the possible framework for the ageing mechanism of erythrocytes.

As described previously, the three components of the cell, the surface sialic acid, membrane protein band 3 and intracellular haemoglobin, have the most opportunity to interact with the environment during the cell’s circulation. The abundance and location of sialic acids on the cell surface make them interact with the environment frequently and suffer a significant loss (20–30%) with age due to the impact of both oxidative and mechanical stresses. Sialic acids govern many cellular and molecular behaviours of erythrocytes. They also affect the action of some hormones, the recognition of different compounds, the catalytic properties of enzymes, the transport process and antigenicity (Ref. Reference Schauer104). Sialic acids serve as the component of binding sites for various pathogens and toxins (Ref. Reference Ilver, Johansson, Miller-Podraza, Nyholm, Teneberg and Karlsson105) (Ref. Reference Lehmann, Tiralongo and Tiralongo106). The variation in the membrane sialic acid and surface charge would lead to a collinear change of all these properties and induce a series of events.

Upon desialylation of the cell membrane, the immediate effect is a loss in the cells’ surface charge or a zeta potential reduction. This reduction in surface charge diminishes the electric repulsion between cells, altering the biophysical properties of cellular interactions and weakening the electrostatic barrier that monocytes/macrophages must overcome. As described in ‘Interactions of erythrocytes with environment’ section, the sialic acid loss would expose the underlying glycans that can be recognized by other endogenous receptors. It also reduces the ability of mucin to protect the cell against oxidants.

As the most abundant RBC membrane protein and the main link between the cytoskeleton and the lipid bilayer, B3p is a vital protein affecting the properties of cell membranes (Ref. Reference Wang107). When RBCs age and under increasing oxidative stress, B3p undergoes a series of changes, such as clustering and conformational change (Refs Reference Lutz and Stringaro-Wipf95, Reference Lutz and Bogdanova108). These changes lead to various alterations in cell properties, including morphological, rheological and biochemical properties (Refs Reference Chen, Huang, Liu and Yuan109–Reference Rudenko111). The changes reduce the affinity of B3p to ankyrin, destabilize band 3-cytoskeleton interaction, increase the lateral mobility of B3p within the membrane and induce vesiculation (Ref. Reference Ferru, Giger, Pantaleo, Campanella, Grey, Ritchie, Vono, Turrini and Low112). They also cause lateral protein redistribution (Ref. Reference Low, Waugh, Zinke and Drenckhahn113), cytoplasmic haemoglobin cross-linking (Ref. Reference Sayare, Fikiet and Paulus114), membrane protein oxidation (Ref. Reference Beppu, Mizukami, Nagoya and Kikugawa115) and opsonization, such as degradation or proteolysis (Ref. Reference Kay and Bennett116). When B3p clustering occurs, it allows for antibody binding, resulting in an increase in the number of cell-bound immunoglobulins (Ig) on the cell surface, promoting the elimination of erythrocytes by the immune system through macrophage-mediated phagocytosis (Ref. Reference Schluter and Drenckhahn117). On the other hand, B3p deficiencies also lead to a loss of protein content, causing spherocytosis and decreased cell stability of the erythrocytes, ultimately leading to haemolysis and anaemia (Refs Reference Inaba, Yawata, Koshino, Sato, Takeuchi, Takakuwa, Manno, Yawata, Kanzaki, Sakai, Ban, Ono and Maede118, Reference Southgate, Chishti, Mitchell, Yi and Palek119).

Inside the cell, haemoglobin, the main component of erythrocytes, is the particular attacking target of oxidative stress. During the interaction with oxidative stress at every moment in circulation, Hb is auto-oxidized to become metHb at approximately 0.5–3% per day (Ref. Reference Umbreit56). This oxidation leads to the production of inactive haemoglobin aggregates, increasing the internal viscosity of the cell, while the hemichromes bind to the cytoplasmic domain of B3p, resulting in severe cellular consequences (Ref. Reference Mannu, Arese, Cappellini, Fiorelli, Cappadoro and Tuuuini79). Moreover, Hb molecules are also undergone considerable loss (~20%) during the erythrocyte ageing by vesiculation (Ref. Reference Willekens, Bosch, Roerdinkholder-Stoelwinder, Groenen-Döpp and Werre120). This significant loss of intracellular proteins reduces the RBC volume and affects the cell’s survival.

Both ours and some other studies found previously (Refs Reference Huang, Wu, Mehrishi, Huang, Chen, Zheng, Liu and Luo14, Reference Lutz and Bogdanova108) that the loss of sialic acid likely causes changes in cell properties by altering the B3p due to the change in NANA carboxyl-related charge. This alteration leads to conformational changes and aggregation of intracellular Hb, causing the proteins to distribute around the cell membrane (Refs Reference Huang, Wu, Mehrishi, Huang, Chen, Zheng, Liu and Luo14, Reference Kang, Huang, Liu, Zheng, Wu and Luo78). Additionally, the autoxidation of Hb molecules further stimulates aggregation and binding to the cell membrane. Consequently, more intracellular Hb molecules aggregate and attach to the inner surface of the cell membrane (Refs Reference Huang, Wu, Mehrishi, Huang, Chen, Zheng, Liu and Luo14, Reference Kang, Huang, Liu, Zheng, Wu and Luo78), specifically at the cytoplasmic domain of B3p (Ref. Reference Demehin, Abugo, Jayakumar, Lakowicz and Rifkind121). This binding not only reduces membrane flexibility (Ref. Reference Hiroshi122) (Ref. Reference Salhany and Cassoly123) but also affects the oxidation of Hb, as it prevents efficient neutralization of ROS generated during autoxidation by cellular antioxidant enzymes (Refs Reference Rifkind, Zhang, Heim and Levy124, Reference Rifkind, Zhang, Levy and Manoharan125). The binding of deoxy-Hb to the cytoplasmic domain of B3p also inhibits the activity of glycolytic enzymes, affecting erythrocyte metabolism (Refs Reference Messana, Orlando, Cassian, Pennacchietti, Zuppi, Castagnola and Giardina126, Reference Galtieri, Tellone, Romano, Misiti, Bellocco, Ficarra, Russo, Rosa, Castagnola and Giardina127).

In ‘Membrane structure and properties of erythrocyte’ and ‘Interactions of erythrocytes with environment’ sections, we discussed the interactions of erythrocytes with the environment and the age-related changes in mass, energy and properties due to these interactions and all the factors presently known to be responsible for causing the changes in different aspects. The comparison of the incidence and strength of the interactions, the magnitude of the changes and the resulting consequences led us to suggest that the loss of surface sialic acid, deficiencies of B3p and Hb oxidation are the three main events in erythrocyte ageing. We inferred this because, compared with other cell components, the surface sialic acid, the membrane protein band 3 and the intracellular Hb have the highest incidence and strength in interacting with environmental factors such as oxidative and mechanical stresses. Furthermore, they undergo the most changes during cell ageing in circulation. Therefore, coupled with their significant roles and the severe consequences induced by their alterations in the cell, they should be considered vital factors for cell ageing, one on the exterior, one on the membrane and the other inside the cell. We can also see from ‘Interactions of erythrocytes with environment’ section that the three factors are involved in almost all age-related physical and chemical changes of erythrocytes in different ways.

After analysing the main events and their sequences that lead to erythrocyte ageing, we can propose the following possible mechanisms of erythrocyte ageing. Since the cell has no nuclei and cannot synthesize new proteins or any more components, its ageing is induced mainly by external stresses: oxidative and mechanical stresses. Especially oxidative stress, which is involved in all three main events of cell ageing, is the crucial cause of erythrocyte ageing. The two external stresses, accompanied by the effect of metabolism, lead to a series of events that trigger the ageing process.

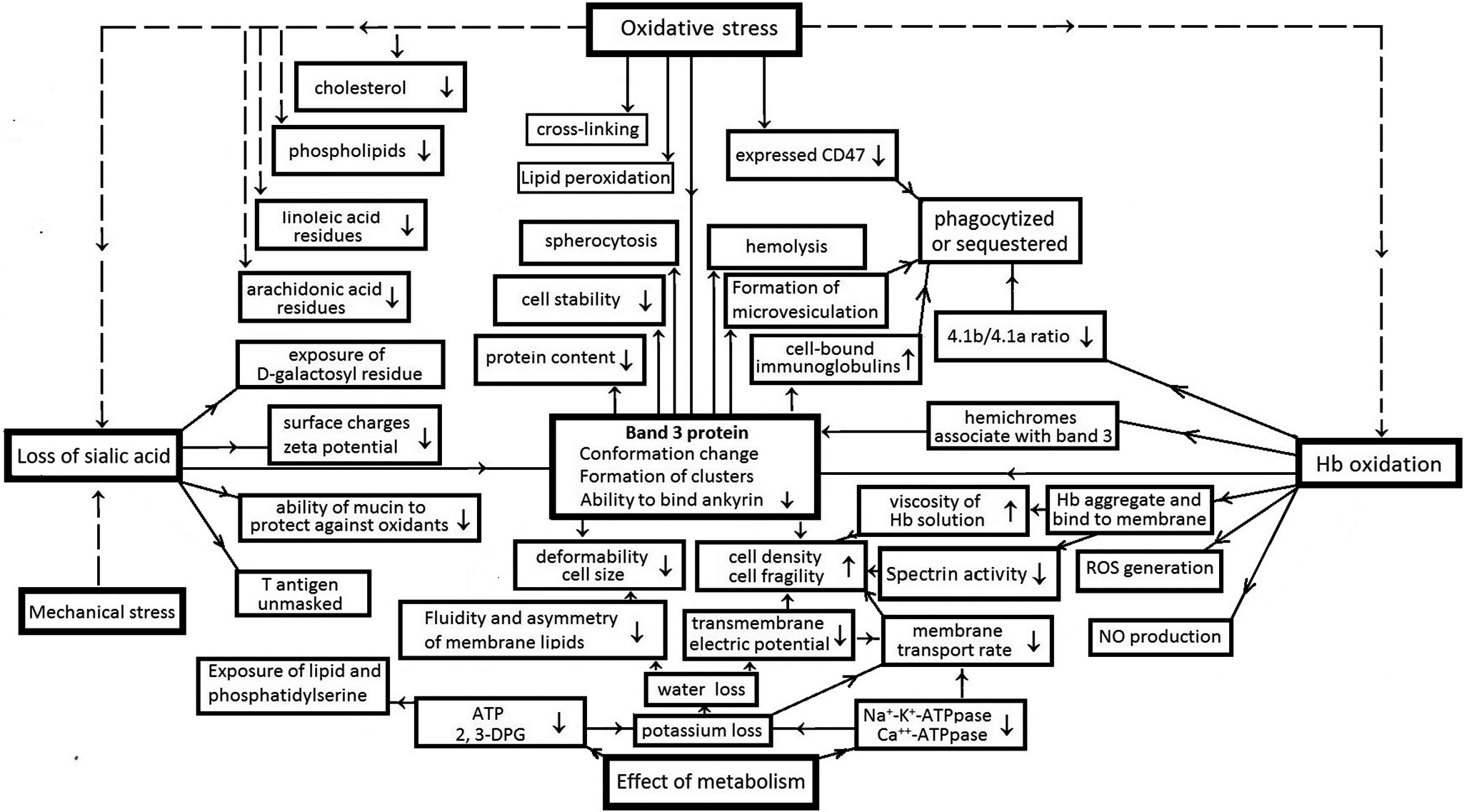

To provide readers with a better understanding of the events and pathways in erythrocyte ageing and the link between cellular behaviours and the molecular basis of ageing, Figure 2 illustrates the framework for the causes and consequences of the events in the erythrocyte ageing mechanism. Erythrocyte ageing is primarily initiated by interactions between the cell and environmental factors, mainly oxidative and mechanical stress and accompanied by metabolic effects. Oxidative and mechanical stresses chiefly result in three primary events in the cell: loss of sialic acids, deficiencies of B3p and haemoglobin oxidation. These events then serve as the key factors, directly or through B3p, induce a series of consequences in the cell through different pathways.

Figure 2. The events and pathway of erythrocyte ageing. The order about the cause and consequence is indicated by the arrows between the boxes. The detail information of the events please refers to the corresponding descriptions in the text and the cited references there.

In the sialic acid loss pathway, the loss of sialic acid directly induces decreases in surface charge/zeta potential (Ref. Reference Huang, Wu, Mehrishi, Huang, Chen, Zheng, Liu and Luo14) and the ability of mucin to protect against oxidation (Ref. Reference Ogasawara, Namai, Yoshino, Lee and Ishii77); the exposure of d-galactosyl residues and T antigen (Refs Reference Schauer28, Reference Varki and Gagneux42). The decline of surface charge reduces the electric repulsion of erythrocytes with other cells and weakens the electrostatic barrier for the awaiting monocytes/macrophages. The exposures of d-galactosyl residues and T antigen also encourage the cell to be identified by macrophages and appeal to macrophages for phagocytosis. On the other hand, the loss of sialic acid induces conformation changes and cluster formation of band 3 proteins.

As shown in Figure 2, oxidative stress can also directly induce the conformation change and cluster formation of B3ps. No matter whether the deficiency of B3p is directly induced by oxidative stress or through the sialic acid loss or Hb oxidation pathway, as described in the last section, it causes a series of events. Including reduction of their ability to bind Ankyrin, declines in cell deformability and stability (Refs Reference Huang, Wu, Mehrishi, Huang, Chen, Zheng, Liu and Luo14, Reference Ferru, Giger, Pantaleo, Campanella, Grey, Ritchie, Vono, Turrini and Low112), increases of cell fragility and cell-bound immunoglobulins (Refs Reference Lutz and Stringaro-Wipf95, Reference Xia, Liu and Zhou128–Reference Orbach, Zelig, Yedgar and Barshtein130) and formation of microvesiculation (Refs Reference Ferru, Giger, Pantaleo, Campanella, Grey, Ritchie, Vono, Turrini and Low112, Reference Gallagher131) so that the cell size and protein content decreases. The consequence of these events is the sequestration or phagocytosis of the cell. The alteration and loss of B3p content can also directly result in spherocytosis of the cell and decreased RBC stability, leading to its haemolysis (Ref. Reference Inaba, Yawata, Koshino, Sato, Takeuchi, Takakuwa, Manno, Yawata, Kanzaki, Sakai, Ban, Ono and Maede118).

In the Hb oxidation pathway, Hb oxidation not only triggers band 3 cluster formation (Ref. Reference Mannu, Arese, Cappellini, Fiorelli, Cappadoro and Tuuuini79) and affects the ability of B3p to bind ankyrin (Ref. Reference Ferru, Giger, Pantaleo, Campanella, Grey, Ritchie, Vono, Turrini and Low112) but also leads to NO production, ROS generation (Ref. Reference Mohanty, Nagababu and Rifkind44) and the 4.1b/4.1a ratio decrease (Ref. Reference Mueller, Jackson, Dockter and Morrison91). Moreover, it can promote the aggregation of Hb molecules and their binding to the membrane (Ref. Reference Huang, Wu, Mehrishi, Huang, Chen, Zheng, Liu and Luo14) and the association of hemichromes with B3p (Ref. Reference Mannu, Arese, Cappellini, Fiorelli, Cappadoro and Tuuuini79). The aggregation of Hb molecules then leads to an increase of Hb solution viscosity and a decrease in spectrin activity (Ref. Reference Antonelou, Kriebardis and Papassideri5) so that the cell deformability decreases and fragility increases.

By the effects of metabolism, the activities of multiple enzymes, such as Na+-K+-ATPpase and Ca++-ATPpase, declined with cell age. The intracellular ATP and 2,3-DPG levels also decrease (Ref. Reference Tuo, Wang, Liang and Huang67). They lead to a loss of potassium and water, thus reducing the transmembrane electric potential and the membrane transport rate of the cell (Ref. Reference Bartosz8). On the other hand, they cause PS exposure (Ref. Reference Bevers and Williamson132), thus decreasing the fluidity and asymmetry of membrane lipids (Ref. Reference Shiga, Maeda, Suda, Kon and Sekiya84). These events also promote the decline of cell deformability and increase of cell fragility, causing the cell to be sequestered or phagocytosed.

As shown in Figure 2, erythrocyte ageing is also affected by some other factors that are directly induced on the membrane by oxidative stress, such as lipid peroxidation, cross-linking of integral proteins (Ref. Reference Berlett and Stadtman46), caspase-3 activation (Ref. Reference Manda, Baudin-Creuza, Bhattacharyya, Pathak, Delaunay, Kundu and Basu87), PS externalization (Ref. Reference Mandal, Mazumder, Das, Kundu and Basu133), decrease of membrane linoleic acid residues, arachidonic acid residues and expressed CD47 (Ref. Reference Burger, Hilarius-Stokman, Korte, Berg and Bruggen99) and increase of cholesterol to phospholipid ratio (Ref. Reference Bartosz8) and so forth. These factors may take effect via B3p or other pathways or even directly lead to the sequestration or phagocytosis of the cell. Nevertheless, according to the strength of the alterations induced by the factors, the loss of sialic acids, the deficiency of B3p and Hb oxidation are the main pathways of erythrocyte ageing. Among them, B3ps are the pivot proteins in erythrocyte ageing. All the events induced by different interactions and through various pathways are mainly via the proteins affecting the erythrocyte ageing, thus making the cell reduce deformability and stability, increasing the cell fragility and density and then leading the cell to either haemolysis or spherocytosis.

The focus of this article is on the ageing mechanism of erythrocytes. We have not delved into the mechanisms for removing senescent erythrocytes from circulation, as these are still under debate and not fully defined. Several authors have discussed these removal mechanisms (Refs Reference Antonelou, Kriebardis and Papassideri5, Reference Badior and Casey9, Reference Lutz and Bogdanova108, Reference Kay134–Reference Thiagarajan, Parker and Prchal137), and interested readers may refer to the related references. It is important to note that the ageing process described here applies specifically to human RBCs in circulation and should not be generalized to other cell types, for most biological cells are nucleated or have organelles and can generate new structure or repair proteins and enzymes during ageing. However, understanding the mechanism of human erythrocyte ageing can provide insights into the significance of factors other than genetic regulation on the ageing of different cell types.

Summary

Based on the physical and chemical changes in erythrocytes during their ageing, and by analysing the main factors inducing the changes and the sequence and correlation of the events occurring in the ageing process, we proposed the molecular mechanism of human erythrocytes ageing. However, as we pointed out earlier, erythrocyte ageing is probably driven by multiple factors and may progress with steps of more than one signalling pathway, working in a sophisticated context of molecular interplays. The current data on human erythrocyte ageing is insufficient to let us have a clear and complete picture of erythrocyte ageing due to lacking information about the genetic basis of erythrocyte ageing, despite recently a study reporting the difference in phenotypic heterogeneity found between normal human RBC and the aged one (Ref. Reference Jain, Yang, Wu, Roback, Gregory and Chi138). Therefore, our proposed mechanism is a fundamental framework that needs to be supplemented and improved by further experimental findings. Nevertheless, it helps readers understand the vital factors and events in the ageing process of human erythrocytes to get insight into the molecular basis of the ageing mechanism. At the same time, it reveals the cell’s ageing would be strongly affected by altering the factors so that remodelling the factors may help slow down the ageing process and extend the lifespan of the cells or even promote recovery of old cells or some dysfunctional cells.

Based on this perception, some researchers have conducted studies to restore the youth of old erythrocytes and extend their lives (Refs Reference Remigante, Spinelli, Straface, Gambardella, Russo, Cafeo, Caruso, Falliti, Dugo and Dossena10, Reference Huang, Tuo, Wang, Kang, Chen and Luo30, Reference Spinelli, Straface, Gambardella, Caruso, Falliti, Remigante, Marino and Morabito62, Reference Yang, Hsu, Wu, Hsu and Chien139–Reference Dumaswala, Wilson, Wu, Wykle, Zhuo, Douglass and Daleke141). As a recent example, in an experiment of remodelling the membrane sialic acids, we successfully restored the youth of old human erythrocytes aged about 90–120 days, and the blood bank-stored human and rabbit old erythrocytes and even recovered some unhealthy cells (Ref. Reference Huang, Tuo, Wang, Kang, Chen and Luo30). Besides their cellular morphological, rheological and viability properties, the structure and functions of their intracellular protein Hb also recovered to almost the same as that of young normal cells. The survival time of the reinjected sialic acid-restored erythrocytes in circulation was extended nearly twofold compared to the aged cells without sialic acid remodelling (Ref. Reference Huang, Tuo, Wang, Kang, Chen and Luo30). These facts demonstrated from another aspect that the alteration of the surface sialic acids is indeed one of the main factors affecting erythrocyte ageing.

The other two vital components, Hb and B3p, are also the primary focus of the remodelling efforts. Recent findings indicate that the molecules derived from the diet of flavonoid-rich foods, such as Hydroxysafflor yellow A, can neutralize ROS and inactivate pro-oxidant molecules, thus improving the structural/functional changes of RBCs and preventing pathological events attributable to oxidative stress-related ageing and other oxidative injuries (Refs Reference Spinelli, Straface, Gambardella, Caruso, Falliti, Remigante, Marino and Morabito62–Reference Remigante, Spinelli, Basile, Caruso, Falliti, Dossena, Marino and Morabito64). Flavonoids can enter RBCs through passive diffusion and then simultaneously bind to Hb and B3p (Ref. Reference Fiorani, Accorsi and Cantoni142). Our recent study found that the binding of flavonoids to the two vital proteins enhanced their antioxidation and anti-glycation ability and helped restore their conformations. As the remodelled proteins regained their proper molecular structure, distribution and functionality, the aged cells could recover their viability properties and become rejuvenated. Besides the effect of rejuvenating old cells, this method offers advantages over the previous way of resuming sialic acid, because pretreating the cells with flavonoids can also prevent RBCs from ageing or various biochemical and mechanical damages, such as those caused by acid–base imbalances and hypoxia (Refs Reference Spinelli, Straface, Gambardella, Caruso, Falliti, Remigante, Marino and Morabito62–Reference Remigante, Spinelli, Basile, Caruso, Falliti, Dossena, Marino and Morabito64, Reference Revin, Gromova, Revina, Prosnikova, Revina, Bochkareva, Stepushkina, Grunyushkin, Tairova and Incina143). This approach also suggests several medical applications. For instance, adopting antioxidant-rich diets, such as foods and drinks with flavonoids, carotenoids and oleoresins, could help alleviate RBC ageing or even rejuvenate aged RBCs in circulation. Moreover, incorporating flavonoids into RBC storage solutions would prevent RBCs from accelerated ageing caused by storage lesions and rejuvenate the aged ones, potentially leading to the development of an ideal long-term RBC storage solution. Our upcoming research article will provide detailed information on this study.

The key finding is that enhancing and remodelling the Hb and B3p proteins with flavonoids can restore the youthfulness of old RBCs, prevent them from ageing or damage due to oxidative and mechanical stress. This further confirms the aforementioned point of view that addressing the three vital factors of RBC ageing – the loss of sialic acids, the deficiency of B3p and Hb oxidation – would help slow down the cells’ ageing process and extend their lifespan. We hope it will inspire more researchers to adopt this promising strategy for rejuvenating aged RBCs, protecting them from ageing and damage, or even treating diseased cells.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Dr. Yue-Ming Zha for the drawing of Figure 1.

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Author contribution

Y.-X.H. conceived and wrote the manuscript.

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests exist.