Introduction

The massive 2015 refugee inflows represented a watershed in European politics. The arrival of more than 2 million asylum seekers in Europe in 2015—2016Footnote 1 prompted not only temporary border closures in some European countries, but also broader political debates on how to deal with the mounting refugee pressure. While much of the ensuing policy debates focused on how to distribute asylum seekers across European countries (on intra‐European Union [EU] discussions on refugee quotas, see Zaun, Reference Zaun2018), an equally important component of the EU's response to the 2015 refugee crisis was the cooperation agreement concluded with a neighbouring country, namely Turkey, in March 2016 to reduce inflows of asylum seekers and other migrants to Europe (Genschel & Jachtenfuchs, Reference Genschel and Jachtenfuchs2018; Smeets & Beach, Reference Smeets and Beach2020).Footnote 2 Though officially credited as successful in significantly reducing migrant inflowsFootnote 3, domestic publics’ views about such type of international cooperation remain little understood. How do voters in countries on different sides of the cooperation agreement view this type of policy? Which features of the cooperation agreement increase public support for the overall policy package, and how do voters navigate the inherent trade‐offs when forming opinions?

Despite its important role in addressing complex cross‐national policy problems, we know relatively little about voters’ preferences for international cooperation on migration management and refugee protection. This is all the more surprising given that such policies are also used in the United States and Central America (Fitzgerald, Reference Fitzgerald2019). One reason for the current gap in the literature is that cross‐country cooperation agreements in this policy area (as in other policy fields) are complex to analyse because they are inherently multidimensional. Thus, a comprehensive understanding of public views about such cooperation requires exploring public preferences not only across countries but also across multiple dimensions of cooperation. In particular, one has to examine: (1) how specific dimensions of cooperation affect public support for the overall policy cooperation package; (2) how these effects differ across the countries involved and affected by the cooperation; and (3) whether there are relevant interactions between dimensions of cooperation.

We begin to address this gap in existing research by examining voters’ preferences for cooperation between European countries and Turkey on irregular migration and refugee protection. To this end, we focus on the 2016 EU–Turkey deal (formally known as the 2016 EU–Turkey Statement), a key EU policy response to the 2015 refugee crisis and the most developed cooperation agreement between the EU and a non‐EU country on migration in recent years,Footnote 4 to identify the most relevant dimensions of cooperation and assess voters’ preferences.

To examine voters’ preferences, we conduct original surveys in which we embed a conjoint experiment in Greece, Turkey, and Germany, that is, the countries most involved in and affected by the 2016 EU–Turkey deal. These countries have different roles in the migration cooperation agreement. Whereas Germany was a major destination country for many migrants attempting to reach Europe, Greece and Turkey are relevant because they represent key transit countries on the different sides of the EU external border.

Theoretically, we draw on priors that we derive from several strands of the international relations literature. In particular, we build on three lines of work exploring the determinants of public preferences for international cooperation on various cross‐national issues, namely (1) perceptions of national interest, (2) altruistic considerations, and (3) perceptions of fairness and reciprocity. These strands of literature allow deriving three sets of expectations about what types of policies the public will favour. The first strand, which sees voters as mainly motivated by the pursuit of the national interest, suggests that citizens should favour those policies that minimize the national burden. The second line of work predicts that other‐regarding concerns, including humanitarianism, underpin public preferences for international cooperation. Consequently, we should find evidence that voters support those policy features that broadly provide refugee protection. Finally, to the extent that perceptions of fairness and reciprocity inform public opinion about international cooperation on cross‐national issues, we can expect that voters will hold stronger preferences for burden‐sharing between the countries involved in the agreement.

We find that voters’ preferences are informed by a combination of national interest, humanitarian protection, and reciprocity considerations. Voters appear thus to balance different considerations when navigating the trade‐offs inherent in such cooperation agreements. For instance, voters in European countries (in our study Greece and Germany) prefer stronger border controls by the non‐EU transit country (Turkey), which is indicative of both a national interest‐oriented public and a preference for burden‐sharing. Similarly, respondents in Turkey support receiving greater support from European countries to help the refugee population that their country hosts. Furthermore, we also see support for several policy features aimed at protecting refugees and asylum seekers, such as refugee resettlement, financial support for refugees, as well as a rejection of ‘pushbacks’ (i.e., the practice of sending irregular migrants back to the transit or origin country without first examining their asylum applications). Hence, the public cares about the agreement's impact on their country, but it also abides by norms of refugee protection and it pays attention to issues of reciprocity and responsibility sharing between countries on different sides of the agreement.

Understanding public policy preferences matters for the political legitimacy and the longer‐term stability of migration and refugee policy cooperation between Europe and Turkey and, more generally, between high and low‐income countries. While public policies may not always reflect public attitudes, research has shown that highly salient policies tend to be responsive to public opinion (see, e.g., Burstein, Reference Burstein2003; Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Reher and Toshkov2019), including on issues of foreign policy (e.g., Soroka, Reference Soroka2003) and migration (e.g., Böhmelt, Reference Böhmelt2019). Yet, existing research tends to concentrate on unilateral, national policies. Less is known about how policies decided at supranational levels, as a result of multinational agreements, fare in terms of responsiveness vis‐à‐vis their respective publics. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that looks simultaneously at how a multinational agreement is reflected upon the public opinion of the countries most explicitly affected by it.

Our study contributes to the literature on attitudes toward asylum seekers and other migrants by shedding light on public preferences for policies that regulate flows of migrants and asylum seekers. We also add to existing research on public views about international cooperation more generally (e.g., De Vries et al., Reference De Vries, Hobolt and Walter2021), and ongoing policy debates about the current EU‐Turkey cooperation on migration management. On the latter, we find considerable public support for the status quo in most dimensions of the EU–Turkey Statement that we analysed, with a few important exceptions and country differences.

Public preferences for refugee(s) and asylum policies

As the 2015 refugee inflows triggered political upheaval in many European countries, empirical research increasingly centred not only on voters’ attitudinal and behavioural reactions to the crisis (e.g., Dinas et al., Reference Dinas, Matakos, Xefteris and Hangartner2019; Gessler et al., Reference Gessler, Tóth and Wachs2021; Hangartner et al., Reference Hangartner, Dinas, Marbach, Matakos and Xefteris2019; Nordø & Ivarsflaten, Reference Nordø and Ivarsflaten2022; Rudolph & Wagner, Reference Rudolph and Wagner2022; Steinmayr, Reference Steinmayr2021), or their migrant admission preferences (e.g., Alrababa'h et al., Reference Alrababa'h, Dillon, Williamson, Hainmueller, Hangartner and Weinstein2021; Bansak et al., Reference Bansak, Hainmueller and Hangartner2016), but also on their preferences for asylum policies (e.g., Jeannet et al., Reference Jeannet, Heidland and Ruhs2021), including the allocation of asylum seekers across European countries (e.g., Bansak et al., Reference Bansak, Hainmueller and Hangartner2017; Heizmann & Ziller, Reference Heizmann and Ziller2020; Van Hooteghem et al., Reference Van Hooteghem, Meuleman and Abts2020).

The latter set of studies sheds light on a specific and highly divisive issue related to asylum and migration policy cooperation between EU countries in the aftermath of the 2015 refugee crisis. Yet, an equally important policy development in that context was the cooperation on irregular migration and refugee protection, negotiated between several EU Member States (including Germany and Greece) and Turkey (a country outside of and bordering the EU), and agreed upon between the European Union and Turkey in March 2016. This agreement has been a central part of the EU's response to the rapid increase in the number of asylum seekers and other migrants arriving in Europe in 2015. Most of this increase occurred along the so‐called ‘East Mediterranean route’, where migrants crossed the Aegean Sea between Turkey and Greece before quickly moving on to other EU countries, especially Germany.

The key provisions of the EU–Turkey Statement were the following.Footnote 5 First, migrants who moved irregularly from Turkey to the Greek islands and did not qualify for refugee protection in Greece could be returned to Turkey. Second, Turkey also committed to taking ‘any necessary measures to prevent new sea or land routes for illegal migration opening from Turkey to the EU’. Third, the EU agreed, in return, to support refugees in Turkey with €6 billion.Footnote 6 Fourth, it also agreed to resettle refugees directly from Turkey under a 1:1 scheme that foresees that, for each Syrian migrant returned from the Greek islands to Turkey, one Syrian refugee will be resettled from Turkey to the EU.Footnote 7 In addition to these four migration‐related provisions, the EU made several conditional commitments on other policy issues of importance to Turkey. Furthermore, although not part of the agreement between the EU and Turkey, an important supporting measure by the EU was financial and operational support for Greece, to help with the reception of asylum seekers and other migrants and to sustain the country's specific role in the agreement.

Following the 2016 agreement, the number of migrants crossing from Turkey to Greece declined significantly. The agreement thus helped the EU achieve its core political objective of drastically reducing the number of asylum seekers and other migrants arriving in Greece and then moving on to other EU countries. It has also clearly benefited many refugees and migrants in Turkey who have received support from the EU's facility for refugees in Turkey. Using this deal as our point of reference, we ask what preferences domestic publics have for cross‐country cooperation agreements aimed at regulating migrant flows and how they navigate the underlying trade‐offs. Given that we examine preferences for a particular type of international cooperation, we turn to the international relations literature to inform our expectations about drivers of public support.

Theoretical expectations

We draw on insights from international relations theory to form expectations about the patterns of public support for international cooperation on regulating migrant flows. Existing literature suggests that instrumental and moral considerations and adherence to social norms play a significant role in shaping public preferences for policy in the international realm (e.g., Heinrich & Kobayashi, Reference Heinrich and Kobayashi2020; Bechtel, Genovese et al., Reference Bechtel, Genovese and Scheve2017). Following this literature, we further decompose moral considerations into two main domains – altruism and perceptions of fairness. We build on this work to derive more specific theoretical predictions about what the publics of the three countries (Germany, Greece and Turkey) want regarding international cooperation on migration and refugee protection. In other words, we build on these individual‐level mechanisms of preference formation to identify general preferences in the three countries. Our focus on the average voter is warranted because international relations theories build expectations with nations as the unit of analysis. Moreover, as the policies that we focus on are taken at the supranational level, country averages constitute an informative summary statistic for national policymakers. In the specific case of interest, both media and pundits focused on country‐level responses to the agreement. Consequently, we prioritize country‐specific summaries in our empirical analyses.

At the same time, particular groups of voters may be more sensitive to certain types of considerations than others, depending on their political ideology, partisan support or views about immigration. For instance, right‐wing individuals or voters for right‐wing parties might be more susceptible to national interest (e.g., cost) considerations. In that case, we would observe, for instance, stronger effects of policy features that tap into national interest and burden for right‐wing or anti‐immigration respondents. Likewise, left‐wing respondents (and voters for left‐wing parties) and proimmigration respondents might be more attuned to humanitarian and empathetic considerations (e.g., Newman et al., Reference Newman, Hartman, Lown and Feldman2013; van der Brug & Harteveld, Reference Van der Brug and Harteveld2021). In that case, these respondents would support more strongly those policy features that broadly provide refugee protection. We explore such subgroup differences in our empirical section.

National interest

Different strands of literature converge toward the idea that sociotropic concerns about how various international processes affect the country as a whole are an important predictor of public views about those processes and preferences for policies to address them. For instance, research on mass attitudes toward trade reveals that individual perceptions about how trade affects the national economy guide attitudes toward trade (Mansfield & Mutz, Reference Mansfield and Mutz2009). Moreover, the literature on immigration attitudes has consistently shown that sociotropic evaluations of how immigration might affect the country as a whole, both in economic and cultural terms, can affect individual attitudes. Individuals who fear immigrants’ economic and cultural impact on their nation are more likely to harbour exclusionary attitudes and restrictive policy preferences (Hainmueller & Hopkins, Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2014, Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2015; Valentino et al., Reference Valentino, Soroka, Iyengar, Aalberg, Duch, Fraile, Hahn, Hansen, Harell, Helbling, Jackman and Kobayashi2019; Sides & Citrin, Reference Sides and Citrin2007).

Building on these theoretical insights, we can expect that perceptions of how the migration cooperation agreement might impact one's own country can inform voters’ policy preferences for such cooperation. In particular, respondents should be sensitive to calculations of costs and national burden derived from the agreement. In our context, this expectation translates into higher public support for those policy features that minimize national burden. Consequently, we should see low public agreement with policy features that entail (e.g., financial) support to other countries hosting – temporarily or over longer periods of time – asylum seekers, particularly in Germany vis‐à‐vis support for both Greece and Turkey and in Greece vis‐à‐vis support for Turkey. Similarly, we should see higher public support for policy features that minimize migrant intake. In other words, respondents in Greece and Germany should favour provisions that reduce numbers of refugees resettled from Turkey, maximize the returns of irregular migrants back to Turkey or establish stronger Turkish border controls to reduce inflows to Europe (and vice‐versa for Turkish respondents).Footnote 8

Altruism

Research on US foreign policy attitudes points to a strong relationship between policy preferences favouring cooperative internationalism (e.g., humanitarian policy, multilateralism) and moral orientations of care, which essentially build on altruism and refer to ‘a concern for the suffering of others’ (Kertzer et al., Reference Kertzer, Powers, Rath and Iyer2014, p. 829). Humanitarian concerns, which have been shown to decrease support for restrictive immigration policies (Newman et al., Reference Newman, Hartman, Lown and Feldman2013), are particularly relevant to understanding attitudes toward refugees and asylum seekers. Fraser and Murakami (Reference Fraser and Murakami2022) propose a theory of humanitarian deservingness to explain attitudes toward refugees. This echoes earlier experimental findings that humanitarian concerns about the deservingness and the legitimacy of the asylum claims are an influential factor in explaining attitudes to refugees, both in European countries and in other major refugee‐hosting countries like Jordan (Bansak et al., Reference Bansak, Hainmueller and Hangartner2016; Alrababa'h et al., Reference Alrababa'h, Dillon, Williamson, Hainmueller, Hangartner and Weinstein2021; see also Hager & Veit, Reference Hager and Veit2019; Czymara & Schmidt‐Catran, Reference Czymara and Schmidt‐Catran2017).

Considering that the instance of international cooperation that we study targeted large numbers of asylum seekers, in particular (though not exclusively) Syrians, humanitarian considerations are likely to be salient and drive policy preferences. That translates into two sets of expectations. First, in Germany and Greece, people will be more supportive of policy features that involve some resettlement as opposed to no resettlement of refugees from Turkey to EU countries. Second, in all three countries (Germany, Greece and Turkey), people will be more likely to support policy features that include financial support to refugees living in Turkey, as opposed to no financial support for this purpose.

Fairness and reciprocity

The literature on public preferences for international cooperation also underlines the importance of reciprocity and fairness considerations. For instance, Brutger and Rathbun (Reference Brutger and Rathbun2021) show that considerations of reciprocal fairness, understood as equality across countries in terms of concessions and benefits, underpin trade preferences. Reciprocity concerns also drive public support for foreign direct investment (Chilton et al., Reference Chilton, Milner and Tingley2020) or climate cooperation (Bechtel, Genovese et al., Reference Bechtel, Genovese and Scheve2017; see also Kertzer et al., Reference Kertzer, Powers, Rath and Iyer2014). Similarly, when it comes to international cooperation to deal with financial crises, both burden‐sharing, that is, the extent to which other actors are perceived to contribute their share, and certain types of conditionality, in particular the adoption of austerity measures in exchange for financial assistance, explain mass preferences for international bailouts (Bechtel, Hainmueller et al., Reference Bechtel, Hainmueller and Margalit2017). Finally, as already mentioned, on migration and asylum issues, there is evidence that European voters support an allocation of asylum seekers that is proportional to each country's capacity (Bansak et al., Reference Bansak, Hainmueller and Hangartner2017), suggesting that voters are concerned about ‘the fairness of the responsibility‐sharing mechanism’ (p. 5).Footnote 9 These theoretical insights suggest that public policy support should depend on whether other actors will reciprocate efforts to reach a common goal and on perceptions that all parties involved are doing their fair share. This leads us to expect interactions between policy features. For example, one may expect higher public acceptance of EU financial support for refugees in Turkey and/or resettlement of refugees from Turkey if coupled with stronger border controls by Turkey. At the same time, policy features establishing how each cooperation partner should contribute to the overall cooperation would tap into concerns about reciprocity and fairness as well.

Note that we do not posit that preferences are informed by one type of explanation only. Instead, we are agnostic and consider the possibility that one or multiple explanations can help us understand preference formation in this area. The existing literature on public preferences for asylum and refugee policies in Europe suggests in fact that concerns with both national interest and protection of rights underpin public preferences (Jeannet et al., Reference Jeannet, Heidland and Ruhs2021). Research on public attitudes to foreign aid, a related issue area, has also found that both moral and instrumental concerns matter for the formation of public preferences (Heinrich & Kobayashi, Reference Heinrich and Kobayashi2020).

The appeal of the status‐quo

A final note concerns the fact that policy feedback effects (Campbell, Reference Campbell2012) could also be at play. There is already some evidence in that sense. For instance, Solodoch (Reference Solodoch2021) suggests that in Germany the EU–Turkey deal generated an increased sense of leadership and competence in solving the refugee crisis (and political trust), which then resulted in reduced anti‐immigrant sentiment and lower public support for the radical right Alternative for Germany. In addition, we cannot exclude a status‐quo bias, which implies that people tend to be risk‐averse and to support the option they are more familiar with instead of uncertain alternatives (for an application and discussion of the status‐quo bias argument to electoral rules, see Plescia et al., Reference Plescia, Blais and Högström2020). This would be consistent with a finding that respondents in all three countries show greater support for the features currently included in the EU–Turkey deal.Footnote 10

Research design: Cross‐national conjoint experiments

Cross‐country cooperation on irregular migration and refugee protection clearly involves multiple dimensions of policy cooperation. Conjoint experiments are particularly suited to study public preferences for such multidimensional objects (Hainmueller et al., Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014).

Conjoint dimensions and policy features

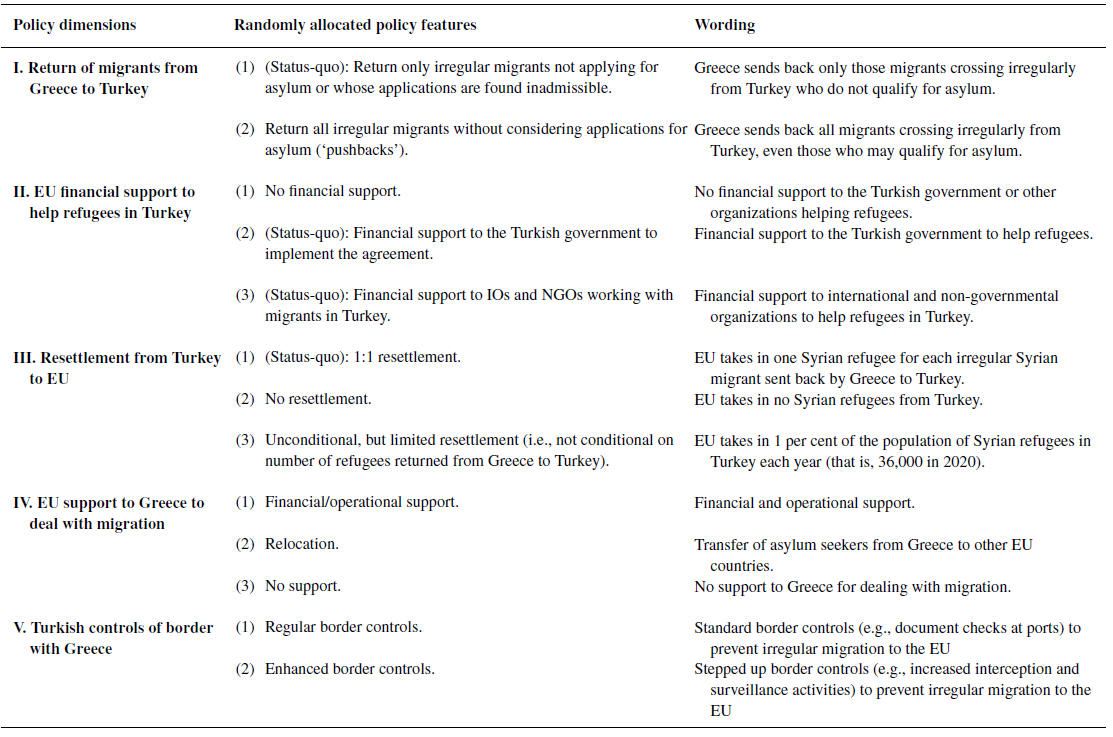

Drawing on the 2016 EU–Turkey Statement, we identified four key dimensions of cooperation between the EU and Turkey on refugee protection and irregular migration and relevant policy features. To the four dimensions, we add a fifth about the support other EU Member States offer to Greece to deal with irregular migration. Table 1 presents a summary of the five dimensions and the corresponding policy features that we identified based on the agreement itself and related policy debates (as we discuss below).

Table 1. Overview of policy features included in the conjoint experiment

Returns. As already mentioned, the 2016 EU–Turkey Statement foresees the return to Turkey of migrants crossing irregularly to Greece who do not qualify for asylum. Yet, despite the large scale of migrant arrivals on the Greek islands in 2015–2016, very few migrants have been returned to Turkey since 2016 (UNHCR, 2020). Alleged practices of ‘pushbacks’ by Greek border guards have instead been reported, although the Greek government has persistently denied these allegations (Kingsley and Shoumali, Reference Kingsley and Shoumali2020). The second potential policy feature that we include in this dimension is, therefore, the return to Turkey of migrants regardless of whether they qualify for asylum.

Financial assistance for refugees in Turkey. Under the current agreement, EU assistance for refugees in Turkey is provided primarily through cooperation with international humanitarian partner organizations such as UNHCR and the Red Cross. Some limited financial resources are provided to Turkish government departments, such as the Turkish Ministry of Education, for specific assistance to refugees. To these potential policies that vary the channel through which aid is granted (i.e., IOs and NGOs or the Turkish government), we add a third policy feature that implies no financial support.

Resettlement. Another key provision of the 2016 EU–Turkey Statement was the above‐mentioned 1:1 mechanism. Yet, while the number of Syrian refugees resettled from Turkey to EU countries since 2016 has been significantly above the number of Syrian migrants returned from Greece to Turkey, it has remained relatively limitedFootnote 11, constituting less than 0.8 per cent of Turkey's Syrian refugee population in 2020. Turkey has called for an increase in these numbers.Footnote 12 To reflect these different dynamics, we focus on three policy features: (1) the ‘1:1’ mechanism, (2) the option of resettling each year 1 per cent of the refugee population that Turkey is currently hosting (i.e., 36,000 refugees), and (3) a policy of no resettlement whatsoever.

Turkish border controls. Increased border controls are at the heart of Turkey's policies to deliver on its commitment in the EU–Turkey Statement. Turkey's implementation of stepped‐up border controls is perceived to have played an important role in reducing irregular crossings from Turkey to Greece after March 2016 (e.g., European Commission, 2021). Besides a policy feature implying enhanced border controls between Turkey and Greece, we include the option of standard border controls (e.g., document checks at ports).

Support for Greece. Although not explicitly part of the 2016 EU–Turkey Statement, we add a fifth policy dimension on EU support for Greece. Greece currently benefits from financial and operational support. Relocation of asylum seekers from Greece to other EU Member States has been very limited (European Commission, 2020b). As a result, and despite the large EU assistance received, some Greek policymakers feel that they are ‘left alone by the EU’ to deal with this issue (Lücke et al. Reference Lücke, Neidhardt, Özçürümez, Ruhs and Diez2021). Accordingly, we include three distinct policy features on EU support for Greece: (1) financial and operational support, (2) relocation, and, as a benchmark against which these two options are to be compared, (3) no support.

Our conjoint experiment was embedded in original surveys conducted in Germany, Greece and Turkey between January and February 2021. We employed national samples of the voting age population including 1,336 respondents in Germany, 1,327 respondents in Greece and 1,259 respondents in Turkey (see section A and Table A1 in the Supporting Information for further details on sampling and summary statistics). After a short introduction that explained the conjoint tasks and defined the terms ‘asylum seeker’, ‘refugee’ and ‘resettlement’ (see section B in the Supporting Information for wording), respondents were presented with five pairs of hypothetical international cooperation agreements between the EU and Turkey on refugee protection and the management of irregular migration (hereafter, policy options). The experiment randomly varied the five dimensions of policy cooperation listed in Table 1, each taking on one of multiple policy features. The order of the five dimensions in the conjoint table was also randomized for each respondent but then remained fixed within respondents across the five conjoint tasks to ease the cognitive burden (for a hypothetical example, see Figure A1 in the Supporting Information).

For each of the five pairs of policy options, we asked respondents to choose one, and to rate both policy options on a seven‐point scale. We use the choice item as our main dependent variable, and present results from robustness checks employing the rating variable as outcome variable in the Supporting Information (see section D in the Supporting Information). In our main empirical analyses, the dependent variable takes on the value of 1 if the respondent chose the policy option in the corresponding conjoint task or 0 if the respondent did not choose it. Following Hainmueller et al. (Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014), we compute first average marginal component effects (AMCEs) to estimate the treatment effects. These can be interpreted as the change in the probability of choosing a ‘policy option’ when a given policy feature is compared to the baseline (Hainmueller et al., Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014, p. 19). The estimation procedure relies on a linear regression of the outcome variable on treatment indicators, with standard errors clustered by respondent. Section C in the Supporting Information reports a series of diagnostic checks regarding the assumptions underlying conjoint analyses, and tests of row‐order effects to address potential concerns about external validity (Hainmueller et al., Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014).

In a second step, we explore heterogenous treatment effects. We begin with a set of sub‐group analyses to examine whether theoretically relevant individual‐level variables (that is, immigration attitudes, left‐right ideology and vote preferences) moderate the treatment effects. Then, we test for interaction effects between treatment variables (that is, between conjoint attributes), following the approach proposed by Egami and Imai (Reference Egami and Imai2019) to estimate average marginal interaction effects (AMIEs) whose relative magnitude is independent of the choice of baseline category.Footnote 13

Results

We begin by presenting our results for the average effects of policy features on the probability that a specific policy package is chosen.

Average effects of policy features on public preferences

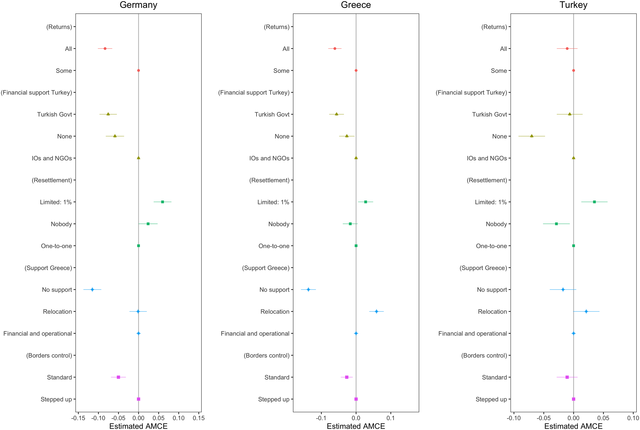

We start by analysing the average causal effects of policy features on the probability of choosing a policy option.Footnote 14 Figure 1 shows the estimated average marginal component effects (AMCEs) with 95 per cent confidence intervalsFootnote 15 separately for Germany, Greece and Turkey. The reference categories within each policy dimension, which are depicted by points without horizontal bars, broadly reflect the status quo (i.e., current provisions of the 2016 EU–Turkey deal).

Figure 1. Effects of policy features on policy choice (point estimates with 95 per cent confidence intervals). [Colour figure can be viewed in the online version of this article] [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Regarding the first dimension (returns), we find that a policy option foreseeing the possibility for Greece to return all migrants crossing irregularly from Turkey (i.e., including those who may qualify for asylum) is estimated to reduce public support by about 8 percentage points in the German sample and 6 percentage points in the Greek sample. Given that the average level of support for packages with the baseline feature is around 54 per cent in Germany, for instance, this means that the alternative is less supported by 8 per cent, yielding a marginal mean of around 46 per cent (see also Figure A2 in the Supporting Information plotting marginal means). While not particularly large, the effect sizes we uncover are similar to other studies on preferences for immigrant admission or asylum policies such as Reference Bansak, Hainmueller and HangartnerBansak et al. (2016) and Jeannet et al. (Reference Jeannet, Heidland and Ruhs2021). This feature does not affect the policy choice probability of the Turkish respondents. This suggests that respondents in Greece and Germany tend to oppose ‘pushbacks’, at least when compared to the status‐quo policy of returning only those irregular migrants who do not qualify for asylum. While this is indicative of support for status‐quo provisions among Greek and German respondents, it also underlines the importance of refugee protection norms, lending credence to the other‐regarding norms hypothesis.

The second dimension refers to financial support for refugees in Turkey. We see that, compared to a policy where such support is channelled through international organisations and NGOs helping refugees in Turkey, a policy package that implies no financial support decreases policy acceptance. The estimated AMCE ranges from −0.03 in Greece to −0.06 in Germany and −0.07 in Turkey. Moreover, policy packages that imply channelling financial support through the Turkish government negatively impact public opinion in Germany (estimated AMCE = −0.08) and Greece (estimated AMCE = −0.06), but not in Turkey. The negative reaction to a failure to provide financial support to refugees in Turkey highlights again the role of humanitarian concerns. However, as the channel seems to matter (that is, German and Greek respondents are less willing to financially support refugees in Turkey if the aid is channelled through the Turkish government), there appear to be limits to public generosity toward refugees, which seem to be grounded in evaluations of the democratic credentials of the cooperation partners.

Moving on to the third dimension, that is, resettlement from Turkey, a policy package that involves the resettlement of 1 per cent of the refugee population living in Turkey is more likely to be accepted than one foreseeing a ‘one‐to‐one’ resettlement mechanism. This is true in all countries: the estimated increase in policy support ranges from 3 per cent in Greece and Turkey to 6 per cent in Germany. Unsurprisingly, the option of no resettlement decreases policy support in Turkey (estimated AMCE = −0.03). It does not, however, affect policy support in Greece. In the German sample, the estimated AMCE is roughly 0.024 points, with a p‐value hovering around the 0.05 threshold.Footnote 16 Humanitarian concerns seem thus to be driving preferences for resettlement policy in Germany and Greece, while Turkish respondents seem to privilege the national interest. At the same time, it is also possible that Turkish respondents are driven by altruism when choosing the 1 per cent resettlement if that policy option is evaluated in light of the benefits it generates for refugees themselves.

The fourth dimension refers to support to Greece to deal with migration. Compared to the baseline category of financial and operational support, a policy feature implying no support is less likely to be preferred in Greece and Germany. It does not have a statistically significant effect in the Turkish sample. By contrast, relocation increases public support in the Greek sample (estimated AMCE = 0.06), but it does not affect public preferences in the German and Turkish samples. This is consistent with both instrumental and fairness/reciprocity concerns driving the Greek public's preferences for EU support, whereas the latter seems to be more relevant in the eyes of German public opinion. Finally, switching from enhanced border controls between Greece and Turkey to a policy feature that foresees standard border controls, decreases public support for the policy package in Greece and Germany. It has no effect among the Turkish respondents. Again, this is consistent with both instrumental (national interest) and reciprocity concerns driving German and Greek preferences for this policy dimension.

Overall, we find that public opinion in the three countries is informed by a combination of national interest and moral considerations. Generally, there is broad consensus around the status quo: changing the status quo with respect to (1) return, (2) financial support for refugees in Turkey, and (3) border controls would decrease public support for the resulting cooperation agreement (particularly in Germany and Greece). On the two remaining dimensions, however, our results highlight favourability towards more targeted reforms. First, compared to the current policy of ‘one‐to‐one’ resettlement, introducing the resettlement of 1 per cent of the refugee population currently living in Turkey would increase public support in all three countries, whereas a policy of no resettlement whatsoever would decrease public support in Turkey (but not in the other two countries). Second, compared to the current approach of granting financial and operational support to Greece, Greek respondents (but not the German respondents) tend to support relocation more.

So far, we have focused on AMCEs. However, these are less suited for direct comparisons between countries, as they are sensitive to the choice of the baseline level. Consequently, we also show marginal means, indicating levels of favourability towards each policy feature including the baseline (Leeper et al., Reference Leeper, Hobolt and Tilley2020), and differences in marginal means across pairs of countries in Figures A2 and A10, respectively. Many of the differences emerging between countries reflect national cost and burden considerations tapping into the country's position in the agreement. For instance, while public preferences are rather similar in Germany and Greece, we do find that Greek respondents are less favourable than German respondents to a policy of no support to Greece, and more favourable to a policy of relocation (which would arguably alleviate the migratory pressure). Similarly, compared to both Germany and Greece, Turkish public opinion is more favourable to channelling financial aid to refugees through the Turkish government and less favourable to a policy of zero financial aid. They are also less favourable than German respondents to enhanced border controls (as this is likely to entail not only an increased financial burden but also a lower chance of refugees living in Turkey traveling to the EU, thereby reducing the refugee pressure on Turkey) and to a policy of no resettlement whatsoever from Turkey to the EU.

Preference heterogeneity

We have focused so far on country averages for both theoretical and policy reasons. Nonetheless, as we alluded to earlier, individual‐level characteristics may act as moderators. For instance, pro‐immigration respondents and left‐wing individuals might be more attune to humanitarian considerations, whereas anti‐immigration respondents and right‐wing individuals might be more sensitive to national burden and cost calculations. Therefore, we investigate, next, whether preferences for international cooperation on migration and refugee protection vary along these individual‐level characteristics. We focus here on pre‐treatment immigration attitudes and discuss results for left‐right ideology and vote choice in section E.1. in the Supporting Information (see also below).

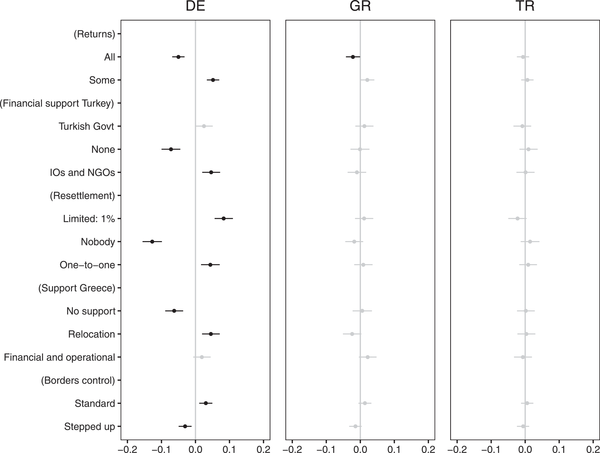

To conduct sub‐group comparisons, we split the country samples at the country‐specific median immigration attitude. Subsequently, for each country, we compute marginal means (reported in Figures A11 to A13 in the Supporting Information) and differences in marginal means (Leeper et al., Reference Leeper, Hobolt and Tilley2020), which are shown in Figure 2. The results point to significant differences between pro and anti‐immigration respondents in Germany, but less so in Greece and Turkey.

Figure 2. Differences in marginal means between pro‐ and anti‐immigration respondents.

Note: Unlike the differences shown in grey, those in black are statistically significant at p‐value < 0.05.

In Germany, pro‐immigration respondents display more support for policy features that have moral implications, as they are on average more favourable to (i) some form of resettlement, (ii) the return of irregular migrants from Greece back to Turkey on condition that they fail to qualify for asylum, (iii) relocation from Greece to other EU countries, and less favourable to a policy of no financial aid to refugees. By contrast, anti‐immigration respondents are less supportive of such policy options and more supportive of stronger Turkish border controls. These results emphasize considerable attitudinal consistency between immigration preferences and policy preferences for international cooperation on migration management. However, some exceptions notwithstanding (see for instance in Figure A11 the differences between pro and anti‐immigration respondents with regards to a policy option of zero resettlement), in many cases it is more a matter of preference intensity than direction. For instance, although we do find that pro‐immigration respondents are more favourable than anti‐immigration respondents to the conditional return of irregular migrants, both groups register higher levels of favourability to this policy compared to the alternative option of ‘pushbacks’.

By contrast, the differences between the two groups are minimal in the Greek sample, where we uncover sub‐group differences only in relation to the ‘Returns’ dimension. Finally, there are no statistically significant differences between the policy preferences of pro and anti‐immigration respondents in the Turkish sample. This points to a broad consensus among Greek and Turkish respondents regarding the preferred outlook of EU–Turkey cooperation on irregular migration and refugee protection. On the other hand, the German public appears to be more divided along pre‐existing immigration attitudes.

We also analysed how left‐right ideology and party preferences condition policy preferences in the three countries, and we uncover broadly similar patterns with some exceptions (see section E.1. in the Supporting Information for a more detailed discussion). Notably, left‐right ideology and vote choice have a strong explanatory role in Germany and, to a more limited extent, Greece. Yet, we do not uncover sub‐group differences between left‐wing and right‐wing respondents in Turkey. These country dissimilarities in how individual‐level characteristics such as immigration attitudes, ideology or party preferences condition policy preferences might reflect differences in how the refugee migration crisis and the immigration issue more generally have been politicized in the three countries, as well as more general cleavages and patterns of political competition.

In sum, we find that the three countries display different patterns of heterogeneity, which however seem consistent with what we already know in the literature about how the issue was politicized in each of them and what the prevailing cleavage structure is. For example, immigration and questions about the integration of migrants became salient in Germany after the country's decision to welcome and host a million Syrian refugees (Czymara & Schmidt‐Catran, Reference Czymara and Schmidt‐Catran2017; Rees et al., Reference Rees, Rees, Hellmann and Zick2019). This explains why attitudes towards immigrants were particularly informative in Germany compared to the other two countries. By the same token, several studies in Greece have exemplified the left‐right dimension in shaping public opinion and party competition in this country (e.g., Dinas, Reference Dinas2017). This is less the case in Turkey where the secular versus religious cleavage often crosscuts traditional ideological lines (Elçi, Reference Elçi2022; Secor, Reference Secor2001).

Finally, to rule out that our results concerning the role of other‐regarding considerations might be confounded by not‐in‐my‐backyard (NIMBY) concerns (Ferwerda et al. Reference Ferwerda, Flynn and Horiuchi2017), we used regional asylum statistics to test whether preferences differ between respondents who live in NUTS‐1 areas with above and below median per‐capita numbers of asylum seekers. The results indicate no systematic differences between the two groups (see Figure A16 in the Supporting Information).

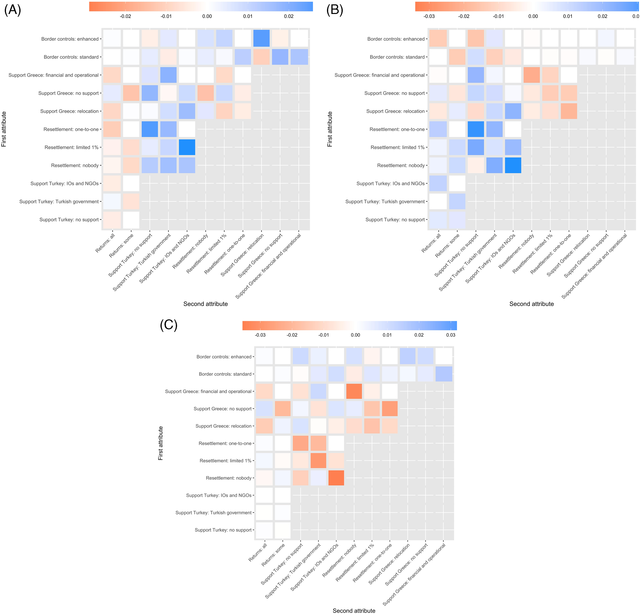

Conditionalities in policy attitudes

Next, we examine two‐way interactions between the policy dimensions to assess whether preferences for one particular policy dimension depend on the specific content of other dimensions of the overall cooperation package. The results, shown in Figure 3 Panels A–C, indicate relatively few interactions that are significant at the 95 per cent significance level.Footnote 17 The colours indicate the size of the estimated average marginal interaction effect, with red indicating negative interactions and blue indicating positive interactions.Footnote 18

Figure 3. Average marginal interaction effects between policy features in Germany (A), Greece (B) and Turkey (C). (Colour figures can be viewed in the online version of the article). [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Our ‘fairness and reciprocity’ hypothesis posits, among other things, that granting EU financial support for refugees in Turkey and/or the resettlement of refugees from Turkey to the EU should be more acceptable in the three countries if coupled with enhanced (instead of standard) border controls by the Turkish authorities. On average, we do not find strong evidence for this expectation. To the extent that concerns for burden‐sharing play a role in preference formation, they do not materialize through a preference for these particular combinations of policies.

However, a number of interactions that were not pre‐registered stand out.Footnote 19 First, we find that in Germany attitudes towards the EU supporting Greece can depend on the type of border controls implemented by the Turkish authorities. This interaction suggests the presence of reciprocity and burden‐sharing concerns in the formation of policy preferences. If enhanced controls are in place, Germans view relocation from Greece to other EU countries more favourably (AMIE = 0.03). This may suggest that the German respondents do not want to risk creating a ‘pull effect’ through relocation from Greece to other EU countries.

The second important finding is related to the interactions between policy dimensions regarding the support Turkey receives, namely resettlement and financial support, but the implications differ markedly between Germany and Greece. In Germany, resettling 1 per cent of the population from Turkey and allocating financial support to refugees in Turkey through IOs and NGOs interact positively. Either of these is the favoured option within its respective policy dimension. If both are jointly present, the policy is a further 3 percentage points more likely to be preferred by the respondents. This suggests complementarity. By contrast, Greek respondents show preferences for substitution between ways of supporting Turkey: we find positive interactions between having resettlement and no financial support and, conversely, between having financial support and no resettlement,Footnote 20 that is, Greek respondents prefer policies that include either aspect but not both.

These results seem to indicate public support for a two‐pronged EU strategy for supporting Turkey: providing EU financial support that reaches beneficiaries without the risk of directly bolstering the current (critically viewed) Turkish government, financed by contributions from all EU member states, and resettling people directly from Turkey to EU countries. In addition, there is scope to relocate people from Greece to other EU countries if the Turkish‐Greek border remains firmly controlled.

Figures A17–A19 and A20–A22 in the Supporting Information look at these interactions separately for left/right‐wing groups and groups with positive/negative views about immigration, respectively. The main takeaway is that there are differences in policy interactions by respondents’ political views and immigration attitudes. In some cases, these are differences in the strength of interactions between sub‐groups, while in others, even the effects’ signs differ. There are quite a number of statistically significant interactions between policy features within each sub‐group, but we advise some caution when interpreting them since there is the risk of false positives.

For example, left‐leaning respondents in Germany show positive interaction effects for deals that benefit both Greece and Turkey simultaneously, while we do not find this pattern among centre‐ and right‐leaning respondents. The attitudes of left‐leaning respondents in Germany thus seem to be driven more strongly by fairness or reciprocity considerations than those of their centrist or right‐leaning co‐nationals. We also find some relevant sub‐group differences in the interaction effects for anti‐immigration attitudes. Sticking to the example of Germany, respondents with more negative views of immigration, who can therefore be expected to care more about reductions in immigration, show a particular dislike for policy packages that would have Turkey enhance its border controls but not receive financial support for this. Instrumental concerns thus seem to be more relevant among the anti‐immigration respondents and this can lead to relatively greater support for packages in which Turkey receives support for its help in reducing migration.

To sum‐up, we find that some policy combinations that tap into reciprocity matter for voters in some countries (particularly Germany and Greece). We also detect some differences in how reciprocity, as captured through policy interactions, plays out for different ideological groups in some contexts (for a longer discussion, see section E.2. in the Supporting Information), although we advise caution when interpreting these results.

Discussion and conclusions

This study examined citizens’ preferences for cross‐country cooperation on irregular migration and refugee protection. Focusing specifically on the EU–Turkey ‘migration deal’ agreed in 2016, we find public support for the status quo in most dimensions of the EU–Turkey cooperation that we analysed, with a few important exceptions and country differences.

Our findings have several theoretical and policy implications. First, public preferences for cross‐country cooperation on these issues appears to be driven by a mix of moral and instrumental considerations, although altruism does seem to have more explanatory power. In the destination countries covered by our study, Greece and especially Germany, voters tend to oppose policies that involve blanket restrictions on access to asylum, such as returning anyone seeking protection without first hearing their case. They also tend to support the annual resettlement of non‐negligible numbers of recognized refugees and to prefer policies that entail aid for refugees in Turkey channelled via IOs or NGOs. Altruistic considerations related to refugee protection appear thus to shape preferences for cross‐country cooperation to a certain degree. As the effects of moral concerns are consistent across regions with varying levels of refugee arrivals (at least with reference to Germany and Turkey), we conjecture that NIMBYism does not threaten our conclusions regarding the role of altruism.

At the same time, we do find that German and Greek respondents support stronger border controls by the Turkish authorities. Unsurprisingly, Turkish respondents tend to oppose policies that fail to ensure financial aid from European countries. This suggests that instrumental considerations related to how the agreement affects the country are also at play, further shaping public preferences.

Moreover, our results also suggest that domestic publics care about reciprocity and burden‐sharing. We find that German respondents prefer the EU backing Greece either through relocation or through financial and operational support, and supporting Turkey financially. Greek respondents show a small but significant preference for policies under which Turks receive financial support for hosting refugees through NGOs and IOs and policies that involve resettlement from Turkey to the EU. In Turkey, voters find EU financial support via humanitarian organizations (rather than the Turkish government) more acceptable if there is resettlement of refugees from Turkey to the EU. We interpret these results as evidence that concerns about reciprocity and responsibility sharing underpin public preferences for cross‐country policy cooperation.

Second, our results suggest that the public also cares about the channel through which financial aid is allocated. We find that allocating aid for refugees via the Turkish government decreases public support among German and Greek respondents. This suggests that people may associate the Turkish government with actions that often characterize ‘nasty’ regimes (Heinrich & Kobayashi Reference Heinrich and Kobayashi2020), such as crackdowns on media or on the opposition, which have been found to decrease support for foreign aid, highlighting thus some voters’ reservations about cooperation with the Turkish state.

One potential criticism of our study is that by design it assumes that voters would prefer some type of cooperation, as opposed to no cooperation whatsoever. Yet, it is theoretically possible that voters might fundamentally oppose cooperation (Reference Bechtel, Hainmueller and MargalitBechtel, Hainmueller et al., 2017). While we do not find this to be the case when focusing on the average voter, our sub‐group analyses suggest that anti‐immigration and right‐wing respondents do hold more hawkish preferences, particularly in Germany. Moreover, in many instances, they discriminate less strongly between policy features within dimensions, which could potentially be indicative of fundamental (as opposed to contingent) attitudes (as we note in sub‐section E.1. in the Supporting Information). However, this pattern is – in many cases – more a matter of preference intensity rather than direction (with a few exceptions). Future research should explore this question more explicitly.

As the specific cooperation agreement that we studied in our empirical analysis has been in place for more than five years, it is unsurprising that we find positive feedback effects (De Vries et al., Reference De Vries, Hobolt and Walter2021, p. 21) on public support for (some of) its key dimensions. However, our results also suggest that there may be room for increased cooperation, particularly on the resettlement of refugees from Turkey to European countries. Resettling each year 1 per cent of Turkey's refugee population seems to be an acceptable policy in all the three countries we study. That policy goes beyond the current one‐to‐one mechanism and it reinforces the idea that citizens care about greater responsibility sharing in this particular area (Bansak et al., Reference Bansak, Hainmueller and Hangartner2017).

Finally, our study also speaks to the growing research on public backlash against international cooperation (De Vries et al. Reference De Vries, Hobolt and Walter2021). Migration is perceived as a challenge to the contemporary global order, particularly because of the nature of domestic politics on this issue (Goodman & Schimmelfennig Reference Goodman and Schimmelfennig2020). However, our results suggest that certain types of cross‐country cooperation can be appealing to domestic publics. We do not find consistent public support for policy features that imply a lack of engagement with partner countries on refugee protection and migration management, except an opposition in Germany and Greece to allocate aid for refugees via the Turkish government. If scepticism exists, it is mostly confined to a subset of the electorate (and mostly in Germany). The average voter in our EU countries appears to support several policy features of the current cooperation agreement between the EU and Turkey (including those concerning the return of irregular migrants, border controls, and financial support to refugees in Turkey via international organizations and NGOs), and to favour expanding the engagement on other dimensions like resettlement.

Acknowledgements

For their helpful comments, we would like to thank the EJPR editors and anonymous reviewers as well as Brian Burgoon, Andrew Geddes, Matthias Lücke, Saime Özçürümez, Alan Sule and Olivia Sundberg. Alsena Kokalari, Foteini Vassou and Asli Okyay provided excellent research assistance.

Funding

The research for this paper was carried out as part of the Mercator Dialogue on Asylum and Migration (MEDAM), an international research and policy initiative funded by Stiftung Mercator.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.