The literary theorist Thomas Yingling asked a haunting question after experiencing the first decade of AIDS: What might it mean “to be a person with AIDS?” What did it mean, Yingling wrote, to secure a subjectivity for the person with AIDS that was not simply an erasure of his or her previous subjectivity, that “simply did not read the illness as the end of meaning”?Footnote 1 Losing a body, losing an identity, losing collective and spatial grounds for an open sexual, political and cultural subjectivity characterized the experiences of many living with AIDS in early years, and beyond.

Grasping, defining and seeing the “person with AIDS” was the single most important way to perceive the epidemic in its first decade. It matters, of course, that this was not a random kind of person, but from a particular population. From the first official acknowledgment of the syndrome in 1981, AIDS was a disease of gay men. And, male homosexuality became the frame through which AIDS was seen as a disease.Footnote 2 In the following years, this much-discussed conflation of sexual identity with AIDS was rejected, criticized, reworked, redefined, destabilized and normalized. Even though male homosexuality is not the dominant picture of AIDS anymore, this socio-medical conflation has a fixed position in the historical narrative of AIDS. Its history is enshrined in a wide range of questions pertaining to politics of identity in the photographic archive of the epidemic.

Photography was deeply enmeshed into the complex politics of representation of the person with AIDS. The person with AIDS was perceived by the public and doctors alike as a risk to a general, heterosexual, public health.Footnote 3 A melancholy associated itself to losing the lightheartedness of a lifestyle that had – once again – been overtaken by medical categories, to the extent that, as Leo Bersani commented, the foundations of sexual identity and masculinity were in peril.Footnote 4 Prompted by this abundant visual politics, Douglas Crimp characterized the struggle of identity in times of AIDS to be torn between forces of mourning and calls to militancy; a struggle driven by repeated questioning as to whether the body of a person with AIDS can be imagined – and visualized – as “still sexual?”Footnote 5

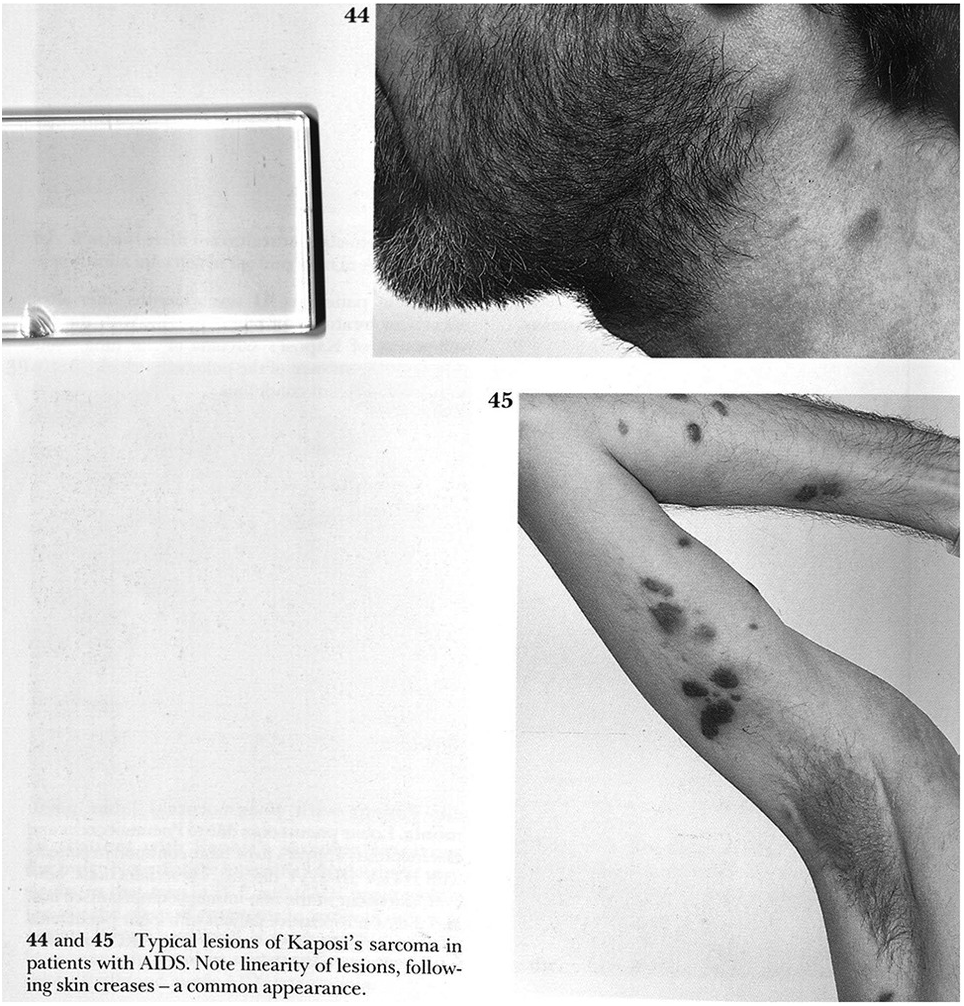

Such questions were not a guiding concern for the atlas editors who selected and laid-out photographs in the first AIDS atlas from 1986 (Fig. 1.1).Footnote 6 This page shows sections of a male body covered in pigmented patches. The photograph’s restricted views do not confide information about the identity or biography of the patient. The body’s presentation in fragments – a flexed arm, the side of a face – leaves the reader in no doubt that the pictures were not intended to deliver a portrait of a person, but rather to visualize what was happening on its surface. The position of the arm and the way it has been cropped in the second picture directs attention to the discolored patches and thus to the significant phenomenon around which the design and argument of the photographs center. The caption to both photographs calls these “typical lesions of Kaposi’s sarcoma in patients with AIDS.”Footnote 7 While the reader might have assumed they were seeing signs of a disease on different body parts of one patient, the caption’s use of the plural form asks us to believe that these pictures are from two different people with AIDS who both show typical lesions of its characteristic skin cancer. The patterned distribution of the lesions, their linearity, is described as a “common appearance,” suggesting the experience of the reading doctor’s eye.Footnote 8

Fig. 1.1 A page from Farthing’s 1986 atlas with two photographs showing “typical lesions of KS.” The photographs were used to draw attention to the morphology of clinical signs while the editors cropped out details that would allow the recognition of personal identities.

Both photographs are presented as classical examples of clinical photography. The editors included them to visualize exemplary signs of a condition, to allow for better recognition and understanding of the disease in the medical community by learning from such ideal cases. According to recent guidelines, a clinical photograph, a specific genre within the broader category of medical photography, should have two key features.Footnote 9 First, the sign of disease must be presented to enhance its recognizability in a day-to-day clinical setting. Second, the photograph should offer an analytical perspective in which irrelevancies to the task of visualizing and isolating the disease are minimized.Footnote 10 In the case of the two photographs here, we are invited to believe that these appearances of KS lesions on the two bodies resemble many, if not all, cases of the same class. This is what could tentatively be called a clinical aesthetic. Photographs of persons suffering from illness become clinical photographs when trusted as visualizations of clinical information located in an atlas, textbook or disease classification.

This chapter revisits the history of medical photography to better understand the purpose and effects of clinical photographs in the AIDS atlas.Footnote 11 I propose we think of medical photographs conceptually with an analogy to what Rheinberger has described as an experimental system.Footnote 12 I use this term to describe how photography is a medium in which uncertainty is not resolved but rather emphasized. To show AIDS, photographs are either tasked with the demonstration of a cleansed and abstracted “epistemic thing,” like a discrete disease.Footnote 13 Or, photographs persist as portraits of suffering and illness, as powerful beacons of empathy, solidarity and recognition – or the lack thereof. Through the history of AIDS, photography was always both an instrument of medical knowledge visualization and a practice of identity politics. This history questions what counts as medical photography as much as it asks how to imagine a person with AIDS.

The “camera medica,” as Erin O’Connor has written, is a medium of naming and identifying, of repeatedly raising the question: “What is it?”Footnote 14 Conversely, most photographs of AIDS have provoked the question “who is it?” or indeed, “who is at stake?” Clinical photography integrated the perception of homosexual men into clinical ways of seeing AIDS, using “who” as a frame to visualize the “what.” But artistic and journalistic photographs were also accused of falling prey to this clinical gaze by superimposing the portraits of homosexual men (“who”) with indices of disease and despair (“what”).Footnote 15 I argue that photography continuously failed to provide satisfying answers to either of these questions. Rather, photography’s key outstanding significance is to be found in its capacity to sustain the relationship of “who” and “what” in enduring uncertainty.

The chapter begins with an outline of photographic practices in the early years of AIDS. It continues with the question of how photography contributed so-called characteristic pictures of diseases to the AIDS atlas. Through the history of medical photography, the chapter’s central concern is to address how photographs acquired authority where language and extant medical categories failed to provide clarity and certainty. With rigorous interrogation of the relationship between disease morphology and patient identity, I ask how photography catalyzed to their entangled appearances. How, if at all, did the placement, arrangement and captioning of photographs in the atlas succeed in separating signs of diseases from persons and cases?

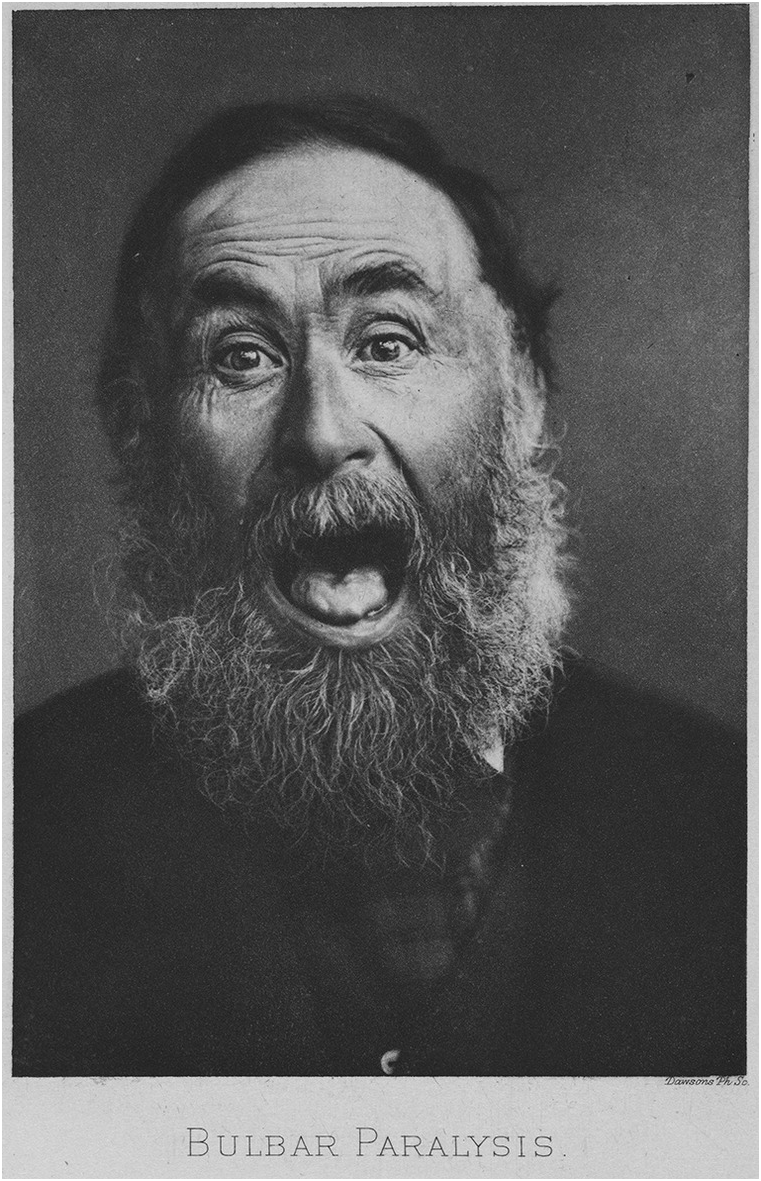

Medical photography owes its visual faculties – its authority in making diseases visible – to two different historical genealogies. On the one hand, after photography was invented in the mid-nineteenth century, when this new visual technology entered the clinic, it adapted and integrated elements of the centuries-old tradition of medical illustration.Footnote 16 Visualizing knowledge rather than mirroring observed occurrence, illustrations had provided visual abstractions, diagrams of symptoms and drawings of signs, reimagined through the eyes of the experienced physician. Illustrations and medical drawings provided exemplary visualizations in which observations from a series of cases were drawn together into a characteristic single visual reference.Footnote 17 Photography, by comparison, was perceived by physicians as a medium of mechanical objectivity and was almost exclusively attached to the single case. On the other hand, and unlike illustration, doctors used photography in the decades after its invention to document unique, spectacular and often-monstrous cases. The extant archives show how extreme appearances and bodily deformities spiked the curiosity of doctors, collectors and a fascinated public.Footnote 18 For representations to be useful to clinicians, photography had to combine an illustrative function with an expression of spectacular appearance. In photography, the visualization of pathological commonplaces was combined with the visual documentation of those appearances that seemed to have left the realms of well-known pathology.Footnote 19 Medical photographers had to prove they could make knowledge about diseases visible, while also making documentations of what was previously unseen and remained unknown and unusual.

Both genealogies of visualizing disease positioned medical photography to be a fitting medium for documenting AIDS in the mid-1980s. Photographs could usefully visualize the incidence of already-known diseases such as KS and herpes simplex, as well as commonplace signs such as lymphadenopathy. Photography married this familiarity with the notion of a radically new syndrome appearing in a highly unusual demographic and social circumstance. The two photographs introduced in the preceding text, and thousands like them, performed two simultaneous tasks in 1986: They showed a skin cancer, training the eye of the doctor or the medical student to recognize the shape of the lesion, its discoloration and specifically its diagnostic qualities. And, they presented an unusual appearance of the cancer on a previously healthy young man. Only by bringing the new and unusual habitat of the skin cancer to light, the photographs showed AIDS.

Still Sexual

In every AIDS atlas published between 1986 and 2008, photographic representations remained loyal to similar clinical aesthetics. Images appeared in series, often spread across two pages, tied together by a caption or title, to name the disease in question. Beginning with the first atlas from 1986, 137 clinical photographs filled 70 pages to catalog rare occurrences, such as a rash resulting from co-trimoxazole treatment in patients with late-stage PCP, to unusual gastrointestinal complications and oral cavity disease, while the main body of photographs was dedicated to skin diseases that seem to have appeared in patients with AIDS. Dermatitis, xeroderma, extensive folliculitis and shingles, among others, were captured in three to four pictures each, attached to a brief but far from exhaustive description of the frequency of the disease’s occurrence, with added notes about treatment experiences.Footnote 20 Among these skin diseases, the most prominent condition with its own dedicated section is KS. After the first page of this section, discussed previously, the atlas featured a further 50 photographs of this rare skin cancer. Pictures detailed lesions’ appearance on the patient’s face, in the mouth, on the tip of the nose as well as on the penis. Some photographs also show relative success and failure of treatments.Footnote 21 The atlas’s second edition in 1988 gives a similar impression, using many of the same photographs. Categories such as pediatric cases were adjusted and photographs were added where none had been available in 1986, such as in the case of bilateral parotid swelling in two little girls with HIV.Footnote 22

In the manner of a catalog of opportunistic infections, the atlas provided a long series of possible clinical appearances of patients with AIDS. To this end the body of photographed patients were never shown in their entirety. Visual references to the same signs were repeated on different, fragmented bodies, as the atlas editors seem to stress that their subject was disease and infection, not the patient. But the series of photographs hardly qualifies as a “cleansed” picture of a disease, which would be ideally presented at a remove from ambiguities, uncertainties and unsolved problems. Fragmented and scattered, distorted and anonymized, the identity of the photographed persons haunts this presentation of the range of diseases characteristic for AIDS. But was a cleansed picture of AIDS ever the aim of Farthing and his colleagues?

In the history of science and medicine objects of knowledge are often discussed as appearing through a process of cleansing. The cohesiveness of any object of inquiry in the sciences is not a given, Bruno Latour has argued, but instead emerges through practices of dividing and of organizing appearances into well-defined objects. “Sorting out the kernel of science from the chaff of ideology” was necessary to differentiate objects of nature from perspectives of culture.Footnote 23 New objects, such as a new disease or syndrome did accordingly never appear in a sudden emanation from the past. But the separation of phenomena that were considered relevant to a scientific investigation from elements which shrouded and clouded its appearance was a necessary step to arrive at a solid body of knowledge about an emerging epidemic.Footnote 24 But instead of seeking a cleansed, separated entity, it is useful here to consider the work of Karin Knorr-Cetina. Her anthropology of scientific labor unmasked rather a rationale for “making things work,” a rationale that governs the laboratory as much as the atlas production as a social space.Footnote 25

As a historian too, it is impossible to define transhistorical and globally pervasive patterns in which science or medicine make things work, intellectual and material dimensions are clearly distinguished and the physical world is separated from the world of ideas. What once counted as intellectual dispute may have become the inventory of contemporary research routines: As Donna Haraway has shown so well, the metaphors of the past are routinely transformed into the hardware of the present.Footnote 26 So too did doctors, editors and research scientists perhaps share the objective to make AIDS appear as an epistemic thing, a cleansed object observable to the sciences, redeemed of its ideological ballast, surrounding stereotypes and complicated relationship to social and sexual identities. But in the 1986 atlas, driven by clinical rather than scientific concerns, AIDS did not seem cleansed and sorted out but was still embroiled in a subject governed by metaphors, stereotypes and many unknowns. The epidemic was witnessed in actu, a yet-developing disaster far from resolution. Nonetheless, this impure and ambiguous mode of representation still seemed to make things work. Just as the Hippocratic recognition of krisis was supposed to enable a prediction of a disease’s inevitable course, the atlas allowed its readership a first sighting of the scope of what was still a rapidly developing AIDS crisis.Footnote 27

In the 1980s, the atlas was by far not the only place in which the medical visualization of persons with AIDS took place. For a time, there was no social or cultural space in which such pictures did not risk becoming medicalized. In his detailed analysis of photojournalistic coverage of the epidemic between 1981 and 2007 David Campbell mapped a shifting visual economy of AIDS. Journalistic framings in the first half of the epidemic were most concerned with capturing the disease in pictures of patients, focusing on symptoms of diseases, such as KS, and medical signs, such as emaciation. But even when a close-up zoomed onto the face of a person with AIDS, refraining to reveal immediate signs of disease and illness, the larger framing as an AIDS photograph tended, as Bethany Ogdon has argued, to “facify” the disease rather than show anything about the individual, such as his or her immediate social context or biographical experiences.Footnote 28 According to Campbell, this trail of visual representations presented the issue of AIDS to the public as a medicalized one, regardless of the publication in which they appeared, from newspapers, journals, galleries to medical publications.Footnote 29

On September 15, 1988, the photographer Nicholas Nixon opened an exhibition at the New York Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), called “Pictures of People.”Footnote 30 The celebrated curation of portraits (Fig. 1.2) gave an insight into America’s private life, bringing hidden worlds and marginalized experiences to center stage. Among the portraits was a series of pictures of people dying from AIDS: Intent on bringing individual suffering into the frame, Nixon’s black-and-white aesthetic leaves a moving impression of the hopelessness AIDS inflicted on individuals like Tom Moran, which had remained largely unseen by the American public. Nixon’s motivations were liberal and humanitarian, but his exhibition and the controversy that ensued showed the complexities of any naïve endeavor to “give AIDS a face.” The political representation of those affected by a deadly epidemic was at stake in this photography. In AIDS’s first decade, photographs of persons with AIDS became a subject in which the morally and politically astute way of seeing the person with AIDS was deliberated, exhibited, analyzed and, by some, fiercely rejected.Footnote 31

Fig. 1.2 Photograph of Tom Moran, a person with AIDS in “Pictures of People” by Nicholas Nixon from 1987. Although produced with the liberal motive of “giving AIDS a face,” the exhibition and portraits like this came under scrutiny by ACT UP and others, as they were accused of presenting the person with AIDS as isolated, desexualized and ravaged by disease.

While Nixon’s photographs were praised by the media, art critics and politicians, AIDS activists staged a protest at the exhibition’s opening. Douglas Crimp lists the criticisms raised by the activists in his analysis, when he argues that the photographs decontextualized the persons suffering from AIDS, isolated them and thus catalyzed fear of AIDS and those who carried the virus, instead of diminishing the fear. To Crimp, the exploitation of isolated and individualized personal experiences of AIDS for public spectacle was bound to the extermination of a public, social, cultural and political responsibility for the epidemic crisis. “[T]he privacy of the people portrayed is both brutally invaded and brutally maintained.”Footnote 32 In Crimp’s view, these photographs should be understood as “phobic images, images of the terror at imagining the person with AIDS as still sexual.”Footnote 33 By representing the person with AIDS as marked by traces of emaciation and cancer, their personality, history, social existence and, in particular, desires were rendered unseen. In Nixon’s photographs, Crimp argued, the person with AIDS became not only the face of the disease but also a powerless patient and a sign of the disease.Footnote 34

Sander Gilman has described the photography of patients with visible stigmata of disease as a public practice of demarcation in which the difference between health and disease is played out as a social, cultural and moral distinction. “The construction of the image of the patient,” he wrote in 1988 reflecting on AIDS photographs, “is thus always a playing out of this desire for a demarcation between ourselves and the chaos represented in culture by disease.”Footnote 35 In the mid-1980s, photographs of people with AIDS were foundational to ongoing debates about how the epidemic was to be perceived, how the problematic history of the medical politics of lifestyle were to be reconciled and how a person with AIDS was imagined and seen. In the case of Nixon’s portraits, they seem to have failed to reveal a political person as they were broadly conceived to exhibit a clinical gaze. Broadly defined as the visualization of disease rather than individual illness experience, this gaze was blamed for structuring the predominant visual regime of AIDS photography at that time. The professional practice of medical photography in turn was thought to be the origin of a way of seeing disease in which personal crisis, the social struggle and the political movements remained unseen.Footnote 36

Photography was used by doctors and by artists in and out of the clinic to craft a representation of AIDS as an embodied condition, which begs the question what it is that sets apart a photograph of a person with AIDS in an artist’s exhibition from a medical perspective applied in an AIDS atlas? To reiterate a prominent question that has been raised before, how do we decide which photograph counts as artistic representation or as an object for scientific and biomedical analysis?Footnote 37 What exactly qualifies a photograph to be bound to the ideas, practices and institutions of the clinic? If the dense entanglement of disease morphology and patient identity is to be seen as an overarching feature of all photographic representations of people with AIDS, how is a singular photograph categorized as an artistic, a journalistic or a medical picture?

The MoMA’s press statement praised Nixon’s photographs for their humanizing capacities. While his photographs sought to bring the audience closer to human suffering, “[T]hey also draw us to the person as an individual, not as an anonymous victim.”Footnote 38 Artistic as well as journalistic portraits were supposed to individualize and hint at the subject’s fate and draw an audience to the patient behind the visible stigmata of disease.Footnote 39 In contrast, the task of an AIDS atlas seems to be to bring the disease to the foreground, to isolate its repeating patterns by hiding the patient’s individuality and rendering the patient’s body an anonymous canvas for the spectacle of recurring symptoms. A first conclusion would be: While the personal and individual proved problematic for visualizing the disease, the abstract notion of pathology posed an obstacle for successful emphatic portraiture. Yet this simplified dichotomy of pictures of disease versus affected persons does not apply to the way medical photography appeared in the first decade of AIDS; to what end was this genre used in the atlas to demonstrate the characteristics of AIDS? Furthermore, one could ask, how far does such a distinction between photography of AIDS in art, journalism and medicine make sense at all, as the shared endeavor was to capture characteristic pictures of a disease in and through portraits of people with AIDS.Footnote 40

A Characteristic Picture of AIDS

Characteristic medical photographs taken to visualize common, typical and obvious signs of disease, but not the patient, comprised Farthing’s Colour Atlas of AIDS in 1986. The atlas was published as a culmination of the clinical experience of Farthing and his colleagues at Westminster Hospital in London as the epidemic was officially five years old. The number of infections had been constantly rising in the United States and the majority of Europe, while preliminary counts suggested an onset of the epidemic in the southern half of Africa.Footnote 41 The only available and partially effective treatment was AZT, approved and introduced a year later, while social profiling of risk groups was still focused on the four Hs: homosexual men, heroin users, Haitians and hemophiliacs. Disputes about the nature of the virus suspected to be the etiological agent were unresolved amongst several research teams, which argued for their chosen pathogenic candidate. Against this backdrop, the atlas editors attempted to produce the first total vision of the epidemic to date, made vivid as a characteristic rather than a definitive picture to its medical audience predominantly through photography.

In the mid-1980s, the state of knowledge about the epidemiology, immunology and virology of AIDS was sparse. Information given throughout the atlas remained vague, speculation is scattered throughout the chapters and many questions they posed remained unanswered. In this state of uncertainty, the resulting atlas appears more like bricolage than a systematized topology. But this seems to have been sufficient to fulfill the atlas’s aim to be a functional diagnostic instrument.

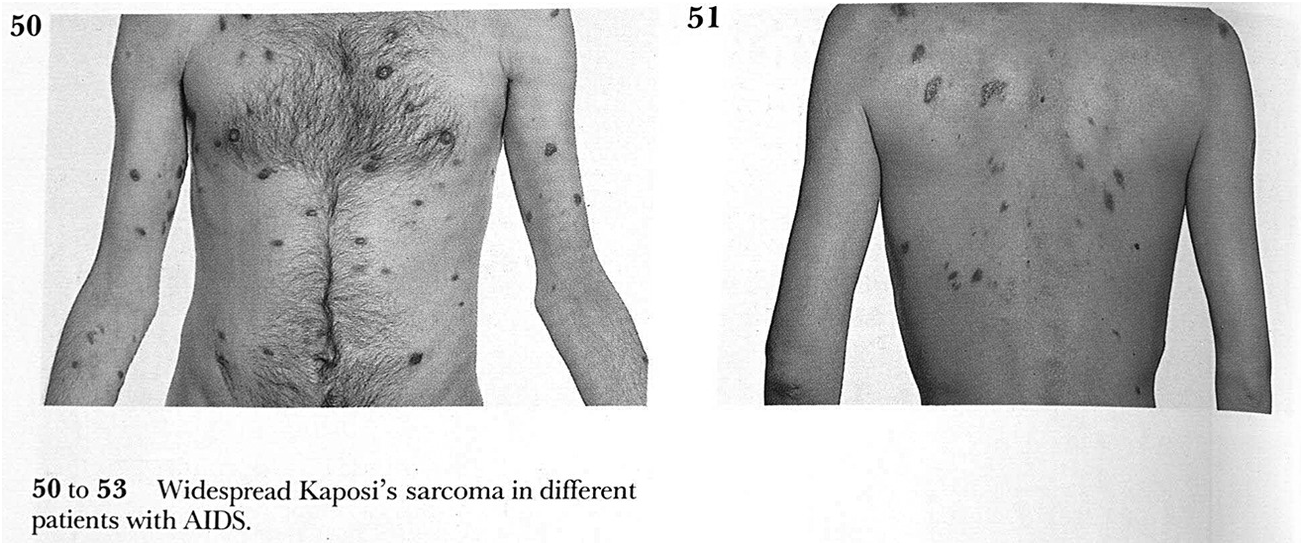

The photographs in the 1986 atlas were not included to strengthen a public empathy with persons who had developed AIDS, nor was their purpose to raise public awareness of the disastrous effects of the disease. As this example (Fig. 1.3) shows, bodies of different patients were depicted as an exchangeable canvas for similar lesions of the sarcoma. To guarantee anonymity, faces were cropped, patients were asked to assume an “anatomical position,” maximizing exposure of the body’s surface to the camera.Footnote 42 Clearly, the photographs do not follow aesthetic conventions of portrait photography: The face is absent unless it is directly affected. Where photographs showed lesions on the facial area, thick black lines were used to provide and secure anonymity for the patients. The background of almost every picture is white, the lighting even and bright and all are, as the title of the atlas promises, in color. Few of the photographs are anchored with a caption, and even if some specific background on what is seen in the photographs is given, no information is offered about the patients, their biography, their location or even their – at this stage improbable – chance for survival. Speculations about homosexual practices and lifestyles were not absent from the atlas but remained disconnected to individual photographs and could be found, for example, in the section on epidemiology.Footnote 43

Fig. 1.3 A page from the section on KS in Farthing’s 1986 atlas of AIDS. The design of the page emphasizes again the focus on a characteristic appearance of widespread KS lesions on two different bodies, each positioned in an anatomical position to maximize the visible surface.

At the time of Farthing’s atlas production, the available method of analyzing blood samples (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay [ELISA]) was complicated, expensive and sometimes unreliable.Footnote 44 Diagnosing the immunodeficiency was often done by bedside clinical methods, and the occurrence of opportunistic infections were caught by the knowing eyes of doctors. Replicating the doctor’s trained gaze, the atlas’s photographs show the reader common diseases including KS, herpes, lymphoma and PCP. All these established diseases, however, now appeared in an unusual social group of bodies, unusual circumstances and, crucially, an unusual frequency and geographical density. These diseases were tied to a milieu in which most of them had never been seen before. The atlas’s first aim was to present a series of cases in which these known diseases had appeared out of their usual place.

This presentation of AIDS was almost exclusively dermatological. It builds on a long legacy of adequate representation of discrete patterns and unique shapes of symptoms on the exterior of the skin.Footnote 45 The gaze rested, to use a Foucauldian phrase, largely on the surface of the body.Footnote 46 It replicates those occurrences that catch the eye immediately and it catalogs the signs that everyone can see. The characteristic picture is construed through series of photographs, presentations of cases to the eyes of interested clinicians and students. The picture series mirrors the structure of the early World Health Organization (WHO) classification of AIDS, published in 1985.Footnote 47 It provided a catalog of opportunistic infections and diseases, clustered into important, frequent and other signs of the immunodeficiency. Each sign was given a number, pneumopathy scored 2 while chronic or relapsing herpes were considered a 4. With several infections present reaching or exceeding a score of 12, the diagnosis of AIDS was established. According to the 1985 classification, generalized KS was counted on its own as 12. In the following years, the classification scheme was widely criticized for its shortcomings and vagueness and was replaced in 1994 with an updated international standard for the diagnosis of AIDS, now heavily reliant on serostatus.Footnote 48

But photographs did more than just replicating the contested classifications of the time. Photography promised the benefit of an impartial perspective, a sober observation of clinical signs and the maintenance of an apparent indifference to the contested terrains of theory about causes, underlying ecologies and epidemiological profiles – the at-the-time-widely-popular investigation into the idea of patient zero, for example, is absent from the atlas.Footnote 49 Contrary to Nixon’s photographs in the MoMA exhibition, the atlas’s series of clinical photographs were designed to visualize only specific aspects and effects of the syndrome. The underlying condition causing the symptoms to appear in the first place was implied as a diagnostic category; it remained a rubric that at this stage could only appear through long series of scattered signs. The clinical photographs did technically not show AIDS, but just isolated aspect of the syndromes disastrous effects.

Susan Sontag has called this absence of a unique signifier of AIDS an “inference.” Diseases like cancer and syphilis served as metaphorical reservoirs to help describe and interpret the new syndrome, indeed “the very definition of AIDS requires the presence of other diseases.”Footnote 50 Instead of appearing as a radically new disease, yielding to unknown and unprecedented symptoms, AIDS instead acquired its unique quality by being a disposition of deficiency that lays the body vulnerable to a series of infections and diseases, and therefore is only accessible as an object of knowledge through the application of a new order of these known diseases and their appearances. The AIDS atlas’s editors used photography to act out this “inference” of AIDS, turning the unseen condition into something visible through a catalog of photographs of manifestations of discrete diseases that can then be seen as references to AIDS.

Another conclusion as to what photography had to offer medical knowledge production in the epidemic’s first decade offers itself here: Through photographs, Farthing’s atlas did not only express the unique shape of AIDS, but his commitment to clinical observation also reinstated medical authority where certainty and expertise were scarce. While the atlas’s first section is about the epidemiology of AIDS, which covered virology, immunology and practical details on accessible test kits, the body of the publication was concerned with a doctor’s bedside encounter with the patient. Rather than detailed descriptions about the agent’s biomedical structure, and in the absence of sufficient epidemiological data or distribution models, photographs seemed to allow a step back from the clamor and to ask its spectator to see rather than to speculate. Photography served as a first layer of careful abstraction, in which the repeated observation of cases was captured and recorded in an emphatically neutral or, rather, clinical way.

The Clinical Close-Up

A year after Farthing’s atlas was published, Paula Treichler delivered her famous essay on the “epidemic of signification.” Confronted with an unending stream of interpretations, beliefs and accusations against the populations at risk, she used this phrase to describe the vast distribution of suggested meanings for AIDS. These conjectures circled around the figure of the hypersexual homosexual male and inscribed those affected by implicating their lifestyle in theories of causation and guilt. By focusing on the continuum between biomedical practices and popular discourses, Treichler cites numerous theories that had at one time been shored up by biomedical knowledge. From the destructive power of sperm, or female immunity against infection, to lethal bacterial cocktails, acquired through many sexual encounters, debate about the true nature of AIDS was heated, despite broad agreement on a viral cause as of 1983. “We cannot therefore look ‘through’ language,” Treichler concludes, “to determine what AIDS ‘really’ is.”Footnote 51

Yingling, by comparison, claimed that the epidemic threatened the fabric of knowledge reaching far beyond the immune systems of risk groups.

The material effects of AIDS deplete so many of our cultural assumptions about identity, justice, desire, and knowledge that it seems at times able to threaten the entire system of Western thought – that which maintains the health and immunity of our epistemology.Footnote 52

Steven Epstein subsumed his analysis of these first years of the epidemic under the header “politics of lifestyle,” as the vast majority of medical knowledge on AIDS was acquired through epidemiological analysis of those affected, while biomedical interrogation lacked convincing explanations for the full range of appearances and occurrences associated with AIDS. Epidemiologists working on AIDS in the 1980s, as Oppenheimer argues, tended to conceptualize the syndrome as complex social phenomenon, inextricably linked to vague social behavior such as “promiscuity,” relations, networks and perceptions of communities.Footnote 53 Lifestyle, sexual identity and communities became embroiled into equally vague definitions of the syndrome, exposing a toxic environment for stigmatization, exclusion and ignorant bigotry toward those considered at risk and perceived as a risk.Footnote 54

In the eyes of many critics, language had provided inadequate to grapple with the emergence of AIDS; words seemed to fall short in the face of such an extent of individual, bodily loss enfolded within a social disaster, political crisis and with little progress in medical understanding. Or as Crimp summarized the crisis in 1987: “AIDS intersects with and requires a critical rethinking of all of culture: of language and representation, of science and medicine, of health and illness, of sex and death, of the public and private realms.”Footnote 55 The perpetual crisis of AIDS led to a stream of metaphors of AIDS, which foregrounded racist stereotypes, conspiracy theories and religious angles alongside competing medical theories that rejected a viral cause.Footnote 56 Looking back, Treichler would call her own collection of AIDS essays, published in 1999, “How to Have Theory in an Epidemic?” to emphasize the complicated ethical challenges of theorizing a disease of such devastating and deadly proportion. By even daring to speak of theory, cultural constructions or explanatory frameworks in the face of those dealing with the epidemic’s overwhelming demands, the immediacy of empirical approaches was appealing in and outside medicine.Footnote 57

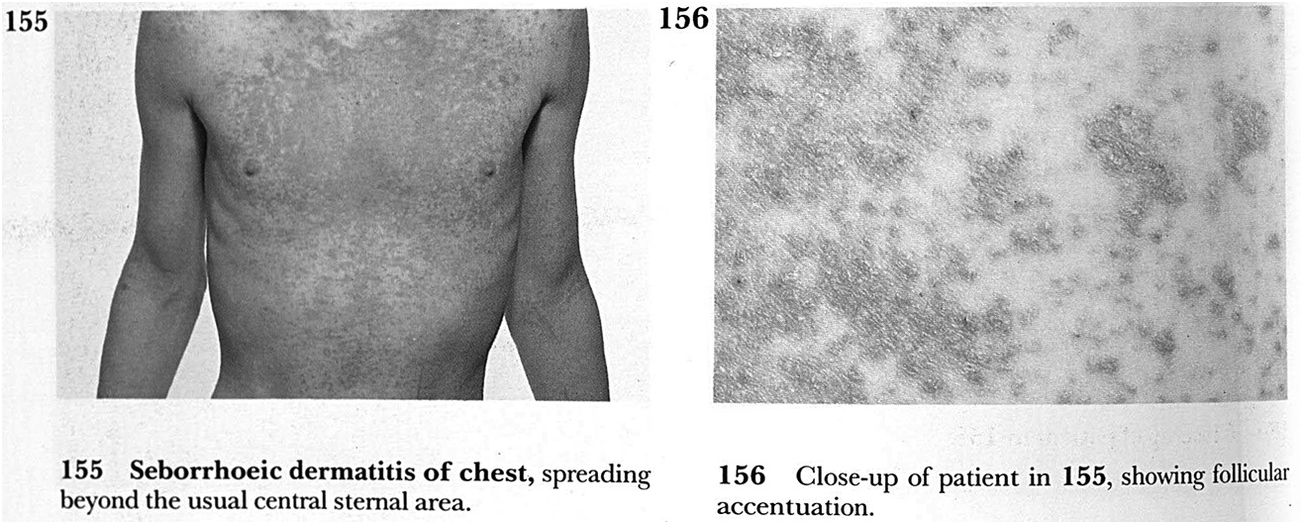

Social theory, cultural studies and literature were not the only places in which language seemed to fail grasping the epidemic. Farthing’s atlas is filled with indications and gestures of uncertainty. His captions reflect discussions about the commonality of certain symptoms and the frequency of their appearance. The reason for increased immunoglobulin production, for example, is described as “uncertain,”Footnote 58 “progressive weight loss may be extremely marked in some patients,”Footnote 59“the reason for the seborrheic dermatitis is as yet unclear”Footnote 60 and the reason for the significant prevalence of KS in homosexual men with AIDS is “unknown.”Footnote 61

Alex Preda has described the ubiquitous practice of calling the appearance of KS and PCP “unusual” and “uncommon” in the early medical publications on AIDS. But for Preda the notion of unusualness and uncommon appearance is not an indication of the authors’ perplexity. Rather he suggests these notions of doubt served as instruments to enable new explanatory models, “signaling novelty and unusualness, redirecting the production of medical knowledge.”Footnote 62 And KS was presented in almost every early report and publication as the disease, whose unusual appearance and uncommon occurrence provided the framework to assume an underlying immunosuppression as its cause. In other words, Preda makes us aware that seeing KS and PCP in these new unusual appearances was the condition under which AIDS could be seen as an “unusual usual” syndrome.Footnote 63 Photographs, which do not feature in Preda’s study of medical rhetoric, resembled this classification practice and presented the unusual appearances as a sign of AIDS.

A useful example of how photographs addressed uncertainty and unusualness is one of the many clinical close-ups from Farthing’s atlas (Fig. 1.4).Footnote 64 Displayed in a diptych conformation a first photograph demonstrated the unusual extent of seborrhoeic dermatitis, spread across the patient’s chest, who is similar to the preceding picture (Fig. 1.3) positioned in an anatomical posture, while the second picture zoomed in to detail the follicular accentuation. The closer the lens got to the patient’s body, the less the patient appears a person and becomes instead a canvas. With higher magnification the appearance of follicles seemed removed from the individual body, from a person’s experience of illness and the dramatic development of the epidemic. Where the first picture tells of a posture of a person, at least partially naked and vulnerable to a frightening disease, the second picture has erased these affective residues of the portrait. Furthermore, the spread of skin disease is captioned as unusual, having moved beyond the commonly affected areas. In the process of cropping, arrangement and caption, these two photographs seem to move successfully from the unusual and confusing appearance of this skin disease to the representation of a disease, which has been marked as indicative of AIDS through its unusual patterns. The depiction “facifies” the symptom in the way that Ogdon describes the close-up as an isolation of the enhanced detail from social, historical and cultural circumstance.Footnote 65 The closer the lens gets, the less contextualized appears the object in front of the camera.

Fig. 1.4 Two photographs of seborrhoeic dermatitis of chest from Farthing 1986. The close-up amplifies the gesture of abstraction with which clinical photography aims to arrive at characteristic representations of the unusual extent of the clinical sign of this skin disease that has been seen in patients with AIDS.

For O’Connor, clinical photography’s concern with superficial occurrences of pathology extends to a visualization practice as an “Art of Truth,” which alludes to the impression the photographs present “things as they are.” But this is less a description of the camera’s accuracy than a representation of the camera’s capacity to conflate surface and substance, to present visual clarity as the key to the deep truth of disease.Footnote 66 For cases deemed exemplary of the ongoing epidemic, photographs gave a way of seeing AIDS that made the abundance of its metaphoric meanings and the uncertainty and resistance of AIDS as an object of medical knowledge for a while unseen. In this particular sense, clinical photography offered a way of seeing AIDS that moved beyond the epidemic of signification and provided an order in which uncertainty and unusualness were sustained rather than resolved.

With this use of photography, the AIDS atlas was built on an old fantasy of medicine, which put faith in an account of pathological phenomena free from speculation, assumption and theory. These photographs appeared to be the products of pure observation as well as accurate case description. Photography as “eyewitness” had been long trusted to translate observation into publication.Footnote 67 In this way, the atlas photographs showed the clinician’s eye applied to AIDS and lent that same way of seeing to the reader. Committed to physical morphology and willfully impervious to the raging “epidemic of signification,” the atlas revealed AIDS as a series of discrete entities of medical knowledge appearing in a new order. To encounter the new epidemic through seeing familiar signs and diseases allowed for the rapid assertion of medical authority.Footnote 68

But how exactly did clinical photography acquire this capacity to assert such authority in the absence of refined categories of AIDS epidemiology or any fundamental understandings of HIV and its microbiological mechanics? The longer history of visualizing disease in illustrations and photographs offers some indication as to how photography emerged as a unique professional medical practice. While it is tempting to see photography as part of the history of the empirical gaze applied to medical phenomena, such an approach forecloses other influences on the photographic picture of disease. Particular modes of analytical and diagnostic seeing were adapted by photography from the older genre of medical illustration, and what could tentatively be called a tradition of diagrammatic reasoning in medicine.

Analytical Visualization in the History of Medicine

The rejection and condemnation of theory was a recurring topic in medical thinking throughout the long nineteenth century. Already the pathologist and atlas-producer Jean Cruveilhier was concerned about systems, concepts and theories in the minds of the physicians around him in the 1820s as he favored an empirical account of disease entities, based on observation and illustration of clinical appearances. In this spirit, Cruveilhier declared the illustrations in his epic atlas to be timeless imprints of nature, resistant to the “back and forth of systems of thinking.”Footnote 69 Instead of reading pedantic descriptions of skin rashes, he believed that seeing illustrations provided immediate and lasting impressions of the diseases in their actual state.Footnote 70

Daston and Galison discuss concern about authorial subjectivity, part of which rested in the limited capacities of language to capture the spectacle of diseases in dense descriptions. To trust descriptions as accurate translations of appearances seen on a patient’s body became contested throughout the nineteenth century. Language was seen as untrustworthy, as it was perceived of leaning toward preconceived images and theoretical abstractions such as the archetype in German Naturphilosophie.Footnote 71 Not paying due diligence to techniques of observation and shrouding the doctor’s judgment, written words were conceived as obstacles to the clinicians’ ability to see and recognize the disease before their eyes.

Cruveilhier’s introduction to his atlas in 1824 provides an interesting starting point for situating illustration in the field of pathological anatomy. His rejection of language and appreciation of illustration as inerrable representation paved the way for the epistemic obstacles photography had to address half a century later. His atlas, the by-then largest collection of illustrations of pathological anatomy was published in 40 consignments between 1829 and 1842 in a design largely influenced by the Paris School of Medicine. Its wide distribution around Europe left a profound imprint on medical visualizations. The order of diseases did not follow abstract tables and classifications but was crafted around the anatomical location of pathological specimen within the human body. The atlas thus further established a way of thinking about disease based not on clusters of disparate signs across the body, but rather on the place of each appearance within or on the body’s surface.Footnote 72

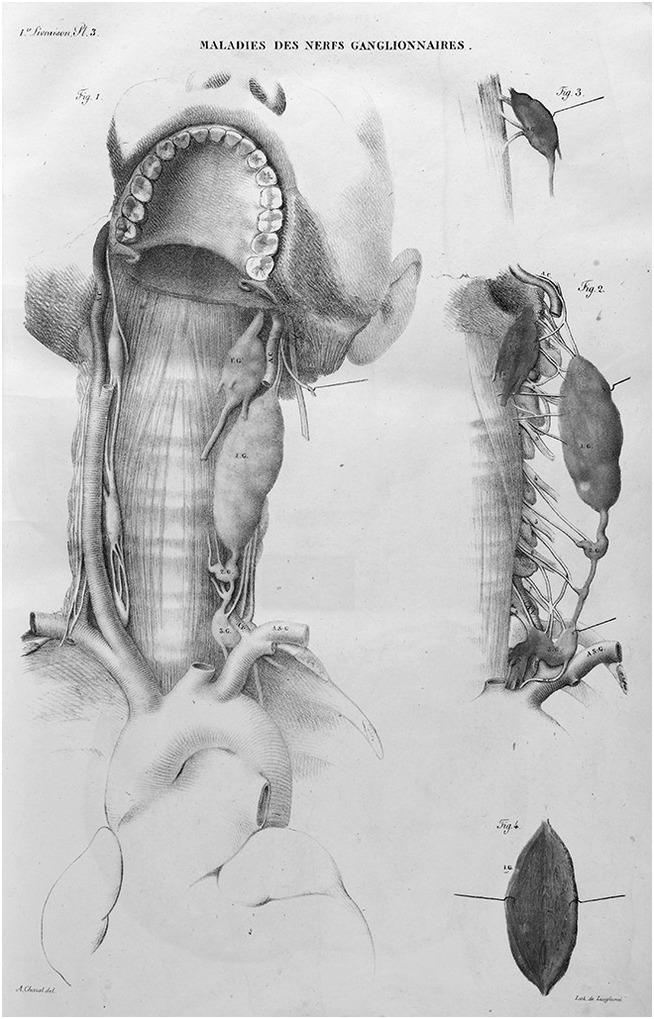

Cruveilhier’s stunning illustrations enhance their depth of meaning through weighted lines, careful coloring and exquisite detailing. Different types of melanoma, which comprised a large portion of the diseases included in the atlas, seem to almost pop out from the page, acquiring vividness and therefore achieving a lifelike truthfulness even to later audiences at the end of the twentieth century.Footnote 73 Letters and numbers were integrated into the fine lines of the drawings and provided anchor points for references in accompanying texts, which delivered detailed description of the particular case history and the diagnosis, such as the names of patients and the circumstances of their arrival at the Hôpital Hôtel-Dieu. Cruveilhier’s drawings focused on the pathological forms and appearances, in the foreground of the pictures, while the surrounding normal anatomy occasionally appeared as a faded background. The malignant tumor depicted in “Maladies des Nerfs Ganglionnaires” (Fig. 1.5) draws particular attention to the color of the tissue, the morphology of the unusual growth and the position within the anatomy of the neck. The healthy anatomy appeared generic and exchangeable, through the absence of color, faded edges and the almost unnatural viewpoint. While the disease is displayed in its figural individuality, the physiological space is brought in as a repeatable background, like a generic stage set.

Fig. 1.5 Plate from the section “Maladies des Nerfs Ganglionnaires” in Cruveilhier’s atlas of pathological anatomy from 1824. The characteristic style of Cruveilhier pulls attention to the pathological specimen by drawing it in its place within a generic human anatomy.

Cruveilhier’s illustrations were rooted in the tradition of case description as well as the long history of visual anatomy.Footnote 74 The ways in which cases have been described in medicine has been subject to much research in recent years, exposing a deep level of formalization in the translation of observation into text and illustration. Prudent observation enabled exhaustive description, which then meant the clinician could turn to systems and classes to compare practice with theory and forge new nosologies throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth century.Footnote 75 But these new empirically based techniques of observation constantly confronted the problem of distinguishing between significant and random signs. When should an observed detail be considered as pertinent to the disease described? How might this decision be made and by whom, as depictions could not always rely on classes and theories of knowledge that preexisted the observation of appearances on a particular body?Footnote 76 Cruveilhier’s visual contribution was precisely tuned to this problem. He wanted his illustrations to be concerned with capturing a characteristic impression of the disease, independent of the back and forth of the “Systèmes.”Footnote 77

The first step in Cruveilhier’s analytical drawing method derived from Philipp Pinel’s commitment to disease observation.Footnote 78 Pinel translated visible signs into exact written replica. The resulting text should be closely tied to what is seen, as if the disease could reveal itself, speaking its own, “native” language through the conduit of the describing clinical observer.Footnote 79 Pinel’s method relied on an exchangeable relation between descriptive language and visual perception of symptoms. This suggested an economy of medical language that could include everything of relevance without losing significant details in its account of the visible stigmata of a disease. This ideal appealed to a stable and exact relation between what is seen and what is said, as Foucault described it for the early-nineteenth-century medicine. Knowing and seeing had become one in this endeavor and doctors imagined themselves to be naturally equipped with a “speaking eye.”Footnote 80 Volker Hess wrote about this as the formation of a grammar of the language of diseases, in which the disease acquired a medical meaning only in the way in which it was enabled to reveal itself.Footnote 81 Reflecting on Pinel’s shortcoming, Cruveilhier criticized this analytical method as a theoretical deformation of the disease. He intervened by providing visualizations of pathological anatomy, which sought to capture nature as it really was.

Through his drawings he could address a most pressing problem of his time. Toby Gelfand described it in the following words: “Formal accounts did not (and could not if they wished to be of finite length and comprehensible) attempt a total picture of disease, replete with the multiple variations which occurred.”Footnote 82 The pathological could not be displayed by using the normative visual practice applied in anatomy atlases: The individuality of cases and appearances and their instances could not be so readily flattened into something so recognizable as a perfected “normal.” Cruveilhier used illustrations to establish the idea of a characteristic picture, a drawing that relies on a single case while it argues that this particular case should be seen as an exemplary case. Where anatomical atlases enjoyed an easy relationship to the individual bodies that might have served as models or templates to arrive at an average, the atlas of pathological anatomy needed to appreciate and integrate the notion of the single case. In its commitment to an empirical account of diseases, Cruveilhier’s drawings bore traces of mistrust to both the formal accounts of nosological tables and archetypical visual traditions of anatomy. The drawings established a way of visualizing pathology that lay somewhere in between, and Daston and Galison refer to Cruveilhier’s drawings as a unique way of arguing visually about diseases in which his approach resembled “a hybrid of the idealizing and the naturalizing modes.”Footnote 83 The pathological object was kept as an individual object but related to a class of things placed in an atlas. This reinvented depicting of pathology at Cruveilhier’s time was needed, as neither the visual tradition of anatomy with its idealistic visualizations, nor the representation of an archetype, or pure phenomena were considered appropriate modes of seeing when it came to diseases.Footnote 84 Intended to heavily supplement or even replace a language-based system, which had failed as a Grammatik of the disease, illustrations established a diagrammatical way of seeing and understanding pathological appearances.

After photography’s inception, illustration did by no means become an outdated technique of clinical visualization. It was and remained an artful diagrammatic of the pathological that embraced empirical yet structured accounts of the observed phenomenon. Similarly to how observations and descriptions were considered first orders of abstraction instead of preconditions for classification, did the art of illustration serve as a translation between the visible lesions and their systematic understanding as signs of disease.Footnote 85

Illustration foreclosed the chance of seeing the unseen in visual representations. The pictures did not include the excess, the information discarded by the clinician’s eye. The unintended, accidental and overseen elements and aspects that might perhaps relate to the disease were routinely excluded from their visualization. Consequently, the reader of these drawn images could not expect to make additional discoveries and could not use the image to interrogate the visualized disease in its multifaceted shape. The viewer had to accept the illustration as the visual representation of an analytical gaze; someone had already decided what was significant for seeing a particular disease.

The AIDS atlas, published 150 years later, was also structured by an analytical perspective comparable to Cruveilhier’s publication. Editorial decisions had been made to include prominent opportunistic infections like KS, PCP, herpes, psoriasis, but not all. Photographs were taken of patients, whose cases had been decided to be characteristic appearances; these photographs were then cropped and captioned to make only those elements visible that were necessary to see the current picture of AIDS. Finally, the comparatively brief paragraphs of text throughout the atlas gave further guidelines for readers to learn how to see and recognize the syndrome in a certain way, but refrained from engagement with larger, contested matters in any systematic way.

However, unlike the illustration, a photograph cannot be so tightly controlled. The use of photography left room for other pictures to emerge. Most importantly, it allowed inclusion of uncertainty, of the unusualness of the appearance of infections in these particular bodies, and freed up an integration of the many unseen assumptions, theories and speculations about the young epidemic, although the overall impression was apparently somber and clinically neutral. Clinical photography was well-suited to present AIDS precisely for its faculty of offering a disease both as a standardized object of knowledge and as an excess of norms, classes and theories. This visual technology emphasized AIDS as crisis of medical knowledge while indicating the stability of medical authority.

Photography and Illustration

The history of clinical photography is still widely unwritten. Studies have analyzed representations produced by the medical use of photography as examples in larger arguments about the visual history of medicine, but no scholar has engaged systematically with this genre at large. Clinical photography’s history remains overshadowed by scholarship on the representation of medicine in society, on specific photographic practices in psychiatry in the case of Charcot and on the history of photography of physiological movement.Footnote 86 Clinical photography has often been loosely included in the wider corpus of scientific photography, as researched by Tucker and others.Footnote 87 But these perspectives tend to overlook a crucial point about clinical photography: As a visualization technique it is intimately attached to the portraiture of the pathological and thus deeply bound to the history of the clinician’s gaze. This gaze is not identical with the perspective of a biologist or a chemist and must be treated within deliberation of the normal and the pathological instead of wrestling objects of nature from systems of culture.Footnote 88 Clinical photography was neither fully committed to eye-witnessing natural phenomena, nor did it work as a pure visualization of nosological knowledge, tables and categories or diseases.

Just months after the invention of the daguerreotype, the earliest form of photography in 1835, the first medical images were taken. In 1852 Berend published photographs that focused on orthopedic diseases, Squire colored photographs in 1864 to show dermatological textures and in 1893 the first comprehensive handbook for medical photography, La photographie medicale was published in France. That year the first issue of the new journal Internationale Medizinisch-Photographische Monatsschrift was published, which taught doctors and photographers alike how to take medical photographs. Photography had become a successor to earlier “visual concepts of pathology” and provided a radical new “medium of seeing” disease.Footnote 89 By the middle of the twentieth century, photography had become the most important medium for the increasingly visual basis of medical diagnostics.

However, this was not a smooth progression to prominence unhindered by resistance, critique and protest. The physician William Keiller expostulated his concern about the craze for medical photography in the 1894 issue of the New York Medical Journal that the “excellence and cheapness of the recent methods of reproducing photographs by photo-engravings has driven the majority of medical illustrators photo-mad.” He continued, “How many text-books and articles are spoiled by beautiful photo-engravings which teach absolutely nothing, where simple diagrams would have been most instructive!”Footnote 90 Similar concerns were raised in the British Medical Journal, where authors complained about the overall lack of detail in photographic visualization.Footnote 91 These outspoken photography protests were not representative of the majority of the medical profession. But many doctors, editors and publishers remained skeptic about the instructive faculty of photography. What was it about a photograph that provoked these concerns, and what ways were found to overcome the epistemic obstacles that forged clinical photography into a genre that could – as in the case of AIDS – express both the stability of medical knowledge and the appearance of a new, poorly understood and mysterious disease?

Moritz Kaposi, who identified and subsequently named the skin cancer that would become an index marker for AIDS, refused to use the new medium. As one of the best-known dermatologists of his time, Kaposi represented the dermatology school of Vienna. Between 1898 and 1900, Kaposi published the Handatlas der Hautkrankheiten für Studierende und Ärzte, which relied exclusively on watercolor illustrations, using wax moulages as templates.Footnote 92 In his preface, Kaposi claimed that the atlas not only collected all significant clinical pictures for dermatology, but visualized the different appearances of the most significant diseases, such as syphilis. He did not give explicit reason for ignoring the half-century history of medical photography, which had already been used in other dermatological atlases.Footnote 93 Instead, he expressed his admiration for the “superior art” of illustration. The atlas consists of hundreds of beautifully painted aquarelles, which depict the then-known dermatological diseases, affixed with short captions.Footnote 94 Beyond the brief preface, no textual commentary is found in the atlas. The authorial medical voice had disappeared from the text or rather taken up residence in the drawings that were fully trusted by Kaposi to transmit knowledge and his clinical perspective in the intended form.

Historically, photographs were mistrusted by physicians because they showed too much. It was not always easy to find particularly poignant cases, photograph them in the right way and crop the resulting picture in a manner that the disease can take center stage. While medical metaphors traveled to conventional portrait photography in the nineteenth century, to lend authority and professionalism to the urban studio photographer, the medical photographer was concerned that his practice would bear too much resemblance to classic portraiture.Footnote 95 The overarching presence of a person, rather than the symptom, was particularly difficult to contain when diseases appeared in the face.

When KS occurred in patients with AIDS, one of the unusual aspects was its manifestation throughout the patient’s body. Classically, in the cancer’s appearance before the time of AIDS, KS lesions were usually to be found along the lower limbs. But the AIDS related appearance of lesions in patient’s faces provided new problems for the atlas editors and photographers. As could already be seen in the first example of this chapter (Fig. 1.1), photographing lesions on and close to the face challenged not only the anonymity that was guaranteed to the volunteering patients, but in regard to the visualization of a disease, it made it significantly more difficult to make the person behind the KS lesion unseen. But KS in persons with AIDS often appeared in the face, and it was partly for that reason that it was the most visible and immediately recognizable sign of AIDS at the time. This prominence exceeded the doctor’s vision, as the facial KS lesion became a spectacle, working as AIDS’s index sign in popular culture, film and television.Footnote 96 But it was still important to draw attention to the unusual facial location, so doctors knew exactly where to look. Ethical considerations and the heated political conflicts around AIDS compelled the editors to maximize anonymity. Their answer in the 1986 atlas was to crop as much of the surrounding visage as possible, to reveal just enough to enable clinical recognition of the signs; to this end the editors were prepared to manipulate pictures extensively.

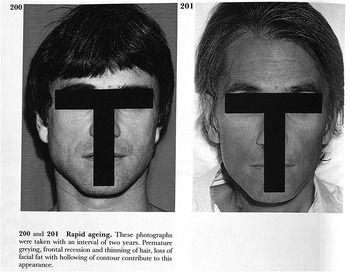

But securing a photograph’s message to be concerned with disease and not a personal portrait was far more challenging, if the disease did not present through characteristic lesions. In the photograph discussed at the beginning of this chapter (Fig. 1.1), we not only see lesions of KS at the edge of the man’s beard but also another striking feature: The facial hair around the chin has become gray.Footnote 97 Graying hair might have been indicative of another process, which was vague in its definition and even more problematic to visualize: the acceleration of appearing old. At the end of the atlas’s section on clinical presentations, the editors drew reader’s attention to AIDS-related signs of “rapid aging.” Two photographs, taken on two separate occasions with an interval of two years, demonstrate the progress of “premature greying, frontal recession and thinning of hair, loss of facial fat with hollowing of contour.”Footnote 98

The photographs look like standard portrait photographs or passport pictures, but two black lines, forming a T-shape, were intended to ensure patient anonymity while enabling the usability of the photograph (Fig. 1.6). Many facets of these pictures are puzzling. The AIDS manifestation described here as “rapid aging” is difficult to define in detail. The overall impression of aging is hard to condense into a comprehensive list of indicators. Where does aging become medical? What excess of aging is too much, and how is this measured? This overall impression is captured in the familiar arrangement of a before-and-after depiction of the person’s face. The premature graying, also present in the KS photograph in the preceding text (Fig. 1.1), the thinning of hair and absence of facial hair is captured in the second shot, but so are other features. The unusual blue background on the left picture suggests it to be perhaps an older prepathological, personal photograph, while a changing haircut hints at the movement of fashion, styles and taste and a sense of the facial expression – in both pictures serious and performing an emphatic neutrality – makes these photographs, despite the editorial gesture of anonymity, particularly vulnerable to be seen as a portrait of a person.

Fig. 1.6 Two photographs selected to demonstrate the process of rapid aging as a symptom of AIDS in the 1986 atlas by Farthing. The black lines guarantee anonymity but also turn the portrait photographs into functional representations, supposed to reveal recognizable signs of aging without compromising the privacy of this person with AIDS.

Despite the black lines’ questionable success in keeping the identity of the patient protected, they made these photographs a clinical picture. Among the practices that photographers, editors and designers applied throughout the atlas, this might be one of the most intrusive and obstructive to the readers’ gaze, hindering a recognition of the person and guiding to an analytical observation of the signs of aging listed in the caption. The black lines practice an abstraction through which the photographs were intended to become readable as a vessel of clinical information. Such practices of taming the photographs’ content have a long tradition. Draping, covering and hiding unnecessary aspects to guide the reader’s gaze to substantial features contributed to the very act of turning a photograph into a medical photograph, by establishing it as an analytical perspective.

Clinical photography adopted these practices from illustration. But it also owes much of its conventions to the wax moulage. In reverse, at the end of the nineteenth century the art of moulage became increasingly dependent on photography. The fragile wax models were photographed for distribution far beyond the hospitals that stored them for teaching purposes. The Atlas der Hautkrankheiten. Mit Einschluß der wichtigsten venerischen Erkrankungen für praktische Ärzte und Studierende, published in 1903 by Eduard Jacobi, used photography exclusively as reproduction of wax moulages, rather than as a technique to capture cases in vivo.Footnote 99 The editor of this dermatological atlas, reissued until the 1920s, gave some hints about why he chose photographed moulages. His reasons were partly based on technical problems. But he also emphasized the advantage of photographed moulages, as they maintained the idealized perspective of the doctors and artists, produced in such perfection, to exactly resemble the disease in the living patient.Footnote 100 Jacobi emphasized that he relied on photographs of moulages as representations of typical diseases, and he expressed no interest in the contemporary trend of bringing monstrous or “interesting” cases to the fore.Footnote 101 That his atlas illustrated typical clinical pictures, he saw the utmost value in guided visual representations so that the practicing physician or the student of dermatology would profit most from reading the atlas.Footnote 102

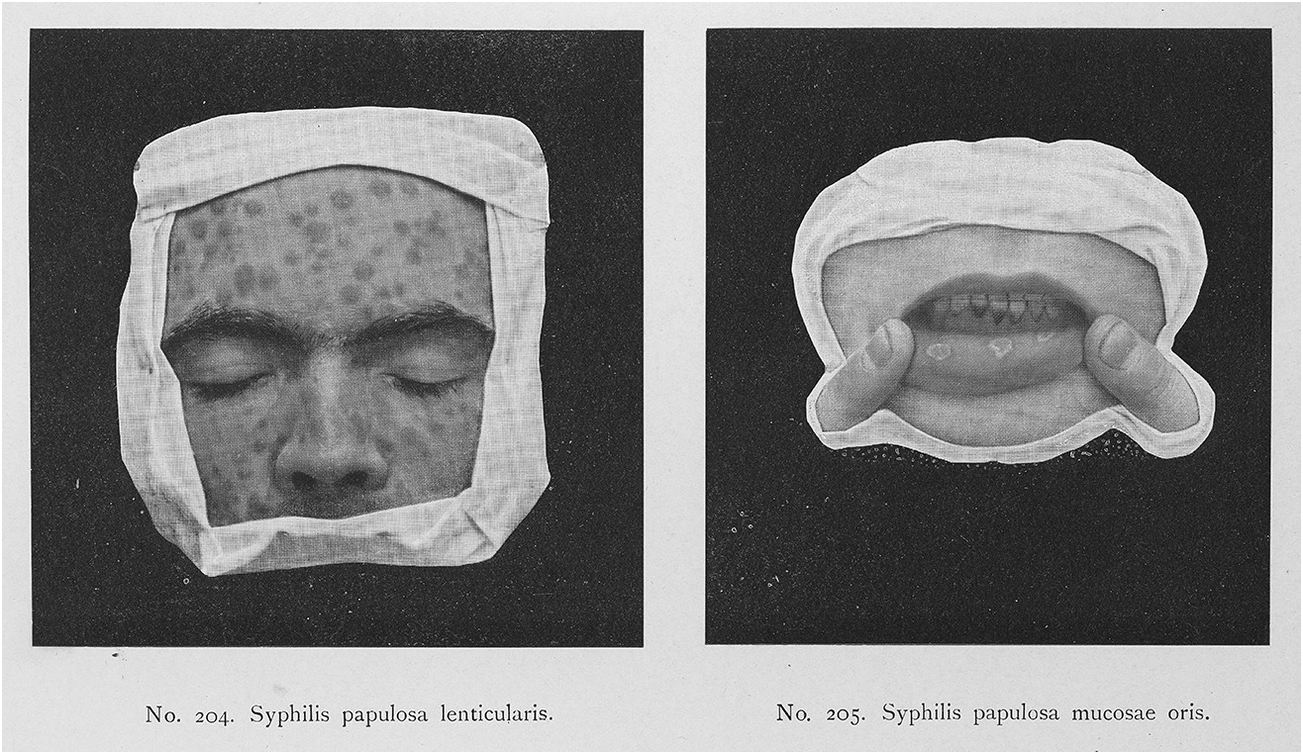

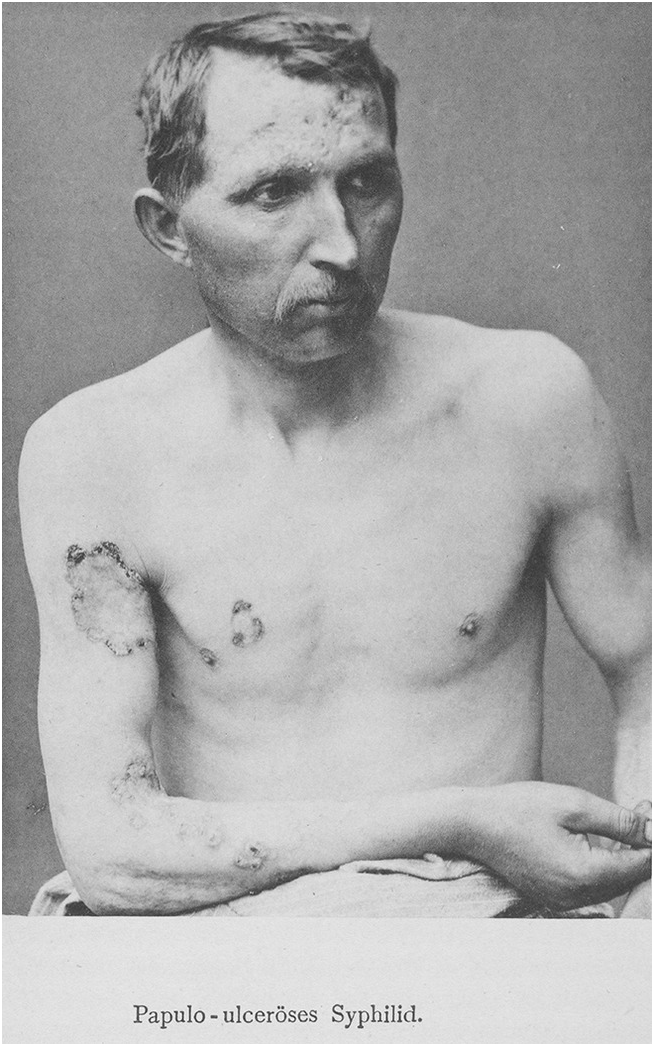

Syphilis was at that time the central topic of dermatology and venereology. Many publications used visual sources to establish a canon of referential images, and Jacobi dedicated a long chapter of his atlas to the pressing problem of a widely distributed syphilis epidemic. He recalled the history of isolating the syphilis infectious agent, the spirochaeta pallida, and listed the visible and invisible clinical signs of its presence in a patient’s body. Detailed and vivid descriptions of lesions, their characteristic appearance and their usual places on a body were briefly referenced by Jacobi in the text but were also visualized through illustrations of so-called Schleimhautpappeln (papulosa).

Two photographic reproductions of moulages (Fig. 1.7) showed the face, or rather a portion of the face. The moulage had been modeled in detail to create a lifelike appearance, emphasized by details like the fingers that pull down the lip to make the lesions visible. As with photography, lifelike impression was the key element that led many doctors to trust the moulage as a teaching instrument. As the moulages’ immobility and fragility were impractical for dissemination and expensive to reproduce and to store, their circulation through photography was of immense value. The act of cropping and draping stands in for the clinician’s analytical perspective, guiding the gaze to the significant details. Cropped into diagnostic certainty, the moulage offered standardized clinical pictures, ready to be widely distributed through photography.

Fig. 1.7 Two photographed moulages in a chapter on Syphilis in Jacobi’s dermatological atlas from 1903. While the moulages were too fragile to be widely circulated, photographic reproduction made these three-dimensional and lifelike illustrations of diseases widely accessible.

Returning to the AIDS atlas, a resemblance between the aesthetic of Jacobi’s photographed wax moulages and the persons with AIDS in, for example, the pictures of aging (Fig. 1.4) is uncanny. In both cases, we see lifelike representations of the symptoms on patient’s bodies, body parts moved to reveal the symptom in its entirety and a series of pictures of bodies juxtaposed to render the individuality of patients, the arbitrary appearance of symptoms in single cases unseen. Cropping and captioning the photograph was a practice modeled on the historical example of illustration and moulage to process diagnostic certainty, so that photographed patient bodies in the AIDS atlas would seem no more than wax models. The point of focus was artfully crafted through a doctor’s speaking eyes, the established medical authority that in turn allowed the pictures to be trusted as instruments of comparison and teaching to recognize actual cases. Drawing on the diagrammatic faculty of the illustration, photographs needed to be tamed, pictures needed to be turned into structured representations of lesions to show a disease.

It is a commonplace that a photographs’ content becomes visible through their material arrangements. “[H]ow they are printed and viewed, as albums, lantern slides, or mounted prints, is integral to their phenomenological engagement, structuring visual knowledge.”Footnote 103 But as Edwards has argued further, while arrangement makes the photograph a readable entity and structures our reading of its content, the photograph’s picture can never fully be disclosed, its meaning is never quite secure and its vision never firmly anchored: The “photograph awakens a desire to know that which it cannot show.”Footnote 104 Showing a lesion, to visualize a rash as it manifests on a person’s body, might be achieved through the material arrangement and manipulation of a photograph in an atlas. But for the photograph to work as a visualization of AIDS, it must do more. It is here where the unseen surplus of the photograph becomes important, where precisely that which illustration cannot show acquires importance and where the relationship of signs of a disease and the person depicted moves to the center.

Here, a second historical genealogy of clinical photography is apparent. Distinct from the diagrammatic capacities of illustrations and wax moulages, photography could bring something new to disease visualization: It showed disease in the contingent individual and singular shape that resisted formal account and abstraction. Skeptical to the idea of solid disease entities, classes and tableaus, the photograph contributed in the late nineteenth century to a new appreciation of disease as an excessive state of life. Precisely because photography was able to integrate the individual picture of disease into the crafting of formalized accounts, it enfolded attraction as a visual representation of pathology as both an abstract entity and a lived reality.

Morphology and Identity

Farthing’s atlas had worked through the process of what Preda had called “making up the rules of seeing.”Footnote 105 Making photographs to show AIDS required extensive framing and manipulation; photographs needed to adapt qualities usually associated with its predecessor genres, illustration and wax moulages. But using photographs could also emphasize the uncertainty and the unusualness of the appearance of diseases in the new habitat of mostly young homosexual men. According to Preda, this notion of unusualness served generally as a condition to see AIDS. And as much as photography could exert a medical authority, where language couldn’t, its key contribution was not to remove but to visualize uncertainty and unusualness as a medical characteristic of the epidemic.

Clinical photographs, I argue here, should be seen as a contribution to persistent ambiguity between the population in which the diseases appeared and the new immunodeficiency syndrome. In other words, seeing AIDS through clinical photographs had the advantage to show the vaguely disclosed, never quite visible, never fully hidden social identity of those, who were part of the demographic, perceived to be hosting AIDS at that time. Rather than aiming for a clear distinction between a disease morphology and a patient’s identity, clinical photography could present the underlying syndrome through a series of pictures of discrete diseases, bound together through the social group in which they appeared.

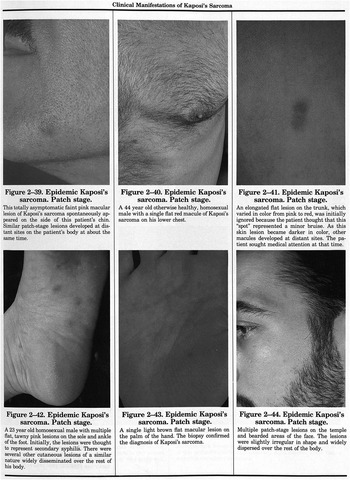

The conflation of gay male identity and KS became more than an underlying subtle theme in Friedman-Kien’s atlas. First published in 1989, this second series operated differently from its predecessor volume by Farthing and colleagues, who contributed a chapter on the history of AIDS to the new atlas. This updated and newly conceptualized book was preoccupied almost exclusively with KS, or rather with the representation of an “AIDS-related epidemic KS” as a specific disease entity. The majority of photographs in this volume either visualize the characteristic skin cancer or show “clinical simulators.” In more than 200 photographs, this AIDS atlas began with a detour, which introduced classic and African cases of KS. The first 40 photographs visualize a wide variety of cases of KS in elderly men in the United States and extreme cases of KS in Africa. These photographs presented a picture of the rare skin cancer as it might have been perceived before the emergence of AIDS. The rest of the atlas was then dedicated to visualizing the variety of KS appearances in people with AIDS, separating different stages – plaque, ocular and nodular – each with about five photographs. Of particular interest is the section on clinical “simulators,” other skin cancers and harmless rashes that share a course of appearances similar to KS but in fact might not share any relation to AIDS. The remaining portion of the atlas is concerned with microscopic and ultrastructural presentations of KS, before a final section with another 50 photographs lists other cutaneous signs of people with AIDS or AIDS-related complex (ARC). Among these conditions are those previously visualized in Farthing’s atlas with prominent presentations of shingles and candidiasis. Only the very last chapter of the 1989 atlas discusses cutaneous appearances of HIV infections, presenting three photographs among microscopic visualizations of the quite unusual and rare appearances in the syndrome’s clinical latency. Throughout the atlas, each photograph is given a short description, classification and diagnostic judgment from the editors, which points in terms of definition and depth of description well beyond Farthing’s work. These texts are significant because they effectively turn each photograph into a singular representation of a case that has been chosen as exemplary.

According to the atlas’s rationale the social identity of the patient achieved yet further significance. Photographs of classical KS, according to how the sarcoma was considered and classified before AIDS emerged, tend to be captioned by identity placeholders such as “elderly Ashkenazi Jewish male” or “75 year old Italian male.”Footnote 106 The second category of “African Endemic KS” was shown on what the editor understood to be African bodies: These are bodies of different ages, sexualities and gender and with different disease histories as far as can be gleaned, but similar only in regard to their common African heritage. The third and largest category included photographs that look similar to those used by Farthing (Fig. 1.8), which here demonstrated the epidemic AIDS-related KS in bodies of “a 44 year old otherwise healthy, homosexual male …, A 23 year old homosexual male. … A 39 year old homosexual male.”Footnote 107 What was an implicit, almost silent connection made in Farthing’s atlas two years earlier became an explicit observation deemed crucial for differentiating and classifying the AIDS-related variant of KS. In a summary of the first decade of AIDS, Friedman-Kien reflected, that: “One of the most intriguing epidemiologic observations is that 95 percent of all cases of AIDS-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma in the United States have been diagnosed among homosexual and bisexual men.”Footnote 108

Fig. 1.8 Page with photographs of people with AIDS-related epidemic KS in Friedman-Kien’s atlas from 1989. The editor disclosed the age and sexual identity of the depicted cases to point to the persistent prevalence of KS among homosexual men with AIDS. But rather than crudely conflating AIDS and sexual identity, this arrangement suggests an analytical separation.

The introduction of the atlas claimed that KS is “truly one of mother nature’s puzzle games.” AIDS was no longer understood as a primarily homosexual disease, and by 1989, as the editor notes, its prevalence among gay communities was indeed declining, the atlas aimed to teach a valuable lesson:

AIDS is not yet a common disease, and many physicians have a limited personal experience with it. The rapidly increasing incidence and spread to the heterosexual population will soon present the general physician with many diagnostic problems. This text will provide a valuable visual course on the cutaneous manifestations of AIDS.Footnote 109

The atlas was founded upon the task of visualizing this transition and expected distribution of the epidemic beyond its already familiar occurrence in homosexual men. In a way, Friedman-Kien aimed to correct the silent – and all too often quite tangible – assumption that AIDS only appeared within the confines of a particular sexual identity. As the introduction to this atlas demonstrates, the notion of unusualness, typical for AIDS’s early years, had taken on a tone of warning. Although the appearance of epidemic AIDS-related KS is shown predominantly on the bodies of homosexual males, Friedman-Kien sought to demonstrate how AIDS had become a familiar sight for some while it was still uncommon to the wider population, where it was assumed to eventually arrive. As a result, many more doctors needed to become fluent with what AIDS might look like. The threat of an impending pandemic seemed to have structured the urgency behind this edition of an AIDS atlas.

By 1989, when Friedman-Kien turned his extensive research on KS into an atlas, the epidemic had become the primary reason for death in the US population between the ages of 25 and 44. The challenge was to overcome a previously established way of seeing, which had proven catastrophic to those who were stigmatized as being the cause for the epidemic. But even according to the US Surgeon General, such outdated perception of a homosexual disease became a public health risk, as it transpired a false sense of security to the rest of the population.Footnote 110 What becomes visible, therefore, in Friedman-Kien’s atlas is an attempt to separate an abstract notion of AIDS and how it worked from the concrete appearance of KS in homosexual men. Clinical photography still contributed to the parallel presence of disease morphology and patient identity but was used in this atlas as a visualization method that aimed for distinction and comparison rather than conflation.