Introduction

Democratization’s opposite, autocratization – the process of political regime transformation toward autocracy and away from democracy (Lührmann and Lindberg Reference Lührmann and Lindberg2019; Cassani and Tomini Reference Cassani and Tomini2020; Møller and Skaaning Reference Møller and Skaaning2023; Croissant and Tomini Reference Croissant and Tomini2024) – is today predominant in various continents. A new research field has been thence striving to examine how it starts, unfolds, and can be prevented (Levitsky and Ziblatt Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2019; Boese et al. Reference Boese, Edgell, Hellmeier, Maerz and Lindberg2021; Diamond Reference Diamond2021; Haggard and Kaufman Reference Haggard and Kaufman2021; Bermeo Reference Bermeo2022; Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge, Edgell, Knutsen and Lindberg2022). However, while autocratization as a decline of (mainly, non-electoral) aspects of democratic quality is widespread, the current number of democratic breakdowns remains less touched, as is the global share of democracies (Skaaning Reference Skaaning2020; Ding and Slater Reference Ding and Slater2021; Brownlee and Miao Reference Brownlee and Miao2022; Treisman Reference Treisman2023).

Against this backdrop, the article advances previous investigations on different autocratization outcomes (Maerz et al. Reference Maerz, Edgell, Wilson, Hellmeier and Lindberg2024). It is obviously essential to explore the conditions under which autocratization can not lead to an autocratic regime (qualitative) change, such as democratic breakdown. In short, what can prevent democratic collapse? Why (and how) do some democracies survive autocratization episodes, while others do not? What, and who, can stop an autocratization process once it has begun, and avert democratic breakdown? These questions are normatively pressing and empirically relevant, considering that many contemporary autocratization processes in democracies are gradual, do not necessarily result in fully fledged autocratic regimes, and are sometimes reversed to original democracy levels, usually after governmental alternation.

Current research on autocratization has already turned the spotlight on democratic endurance. On the one hand, mostly large-N contributions have investigated structural conditions (democratic resilience) that can protect democracy from the very occurrence of autocratization (Schedler Reference Schedler2001; Svolik Reference Svolik2008; Boese et al. Reference Boese, Edgell, Hellmeier, Maerz and Lindberg2021; Lührmann and Merkel Reference Lührmann and Merkel2023). On the other, a recently burgeoning research concentrates on actor-centered resistance to autocratization (Gamboa Reference Gamboa2017, Reference Gamboa2022; Somer et al. Reference Somer, McCoy and Luke2023; Carothers Reference Carothers2024; N. Truong et al. Reference Truong, Ong and Shum2024; van Lit et al. Reference van Lit, van Ham and Meijers2024; Weyland Reference Weyland2024a; Williamson et al. Reference Williamson, Akor and Edgell2024; Panzano et al. Reference Panzano, Benazzo and Bochev2025; Riedl et al. Reference Riedl, Friesen, McCoy and Roberts2024a, Reference Riedl, McCoy, Roberts and Somer2024b), as ‘any activity (…) taken by a changing set of often interconnected and interacting actors who, regardless of the motivations, attempt at slowing down, stopping, or reverting the actions of the actors responsible for the process of autocratization’ (Tomini et al. Reference Tomini, Gibril and Bochev2023, p. 121).

As relevant as the findings are due to their focus on agency, democratic resistance studies remain broadly centered on small-N designs. This article systematically advances them into a broader comparative framework. This is crucial to prevent case selection bias (internal validity, misconsidering background conditions) and identify factors that may be context-dependent or generalizable (external validity, establishing clear scope conditions). We therefore employ the state-of-the-art tools of fuzzy set qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) to study 69 autocratization episodes started in democracies in the 21st century (2000–23) and examine the combinations of democratic resistance actions that are associated with democratic survival. Our analysis directly takes as unit of analysis such autocratization episodes in democracies (country-start/end-years) defined by the Episodes of Regime Transformation framework (ERT, Maerz et al. Reference Maerz, Edgell, Wilson, Hellmeier and Lindberg2024, related to the Varieties of Democracy, V-Dem, Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Altman, Bernhard and Fish2025), which we modify to include all crucial cases identified by autocratization studies – while incorporating countries with a substantial and persistent democratic decline (Pelke and Croissant Reference Pelke and Croissant2021). We then distinguish whether such episodes include a democratic breakdown, defined by the ERT as a shift to an autocratic regime followed either by an election or by a permanence in such a new regime category.

We take information on actions opposing autocratization attempts from an event-based source: the Democratic Erosion Event Dataset (DEED, Gottlieb et al. Reference Gottlieb, Blair, Baron, Arugay, Ballard-Rosa, Davidson, Gamboa, Grossman, Grossman, Kulich-Vamvakas, Lapp, McCoy, Robinson, Rosenzweig, Royer, Schneider, Stokes and Turnbull2023). The DEED reports monthly information on the occurrence of events associated with democratic erosion and resistance. We group resistance events within each autocratization episode and reorganize them into five macro-areas: checks and balances provided by institutions such as the judiciary and bureaucracy (1, institutional resistance); actions of opposition parties through electoral alliances and coalitions or within the legislature, or (with data from the Varieties of Party Identity and Organization, V-Party, Lindberg et al. Reference Lindberg, Düpont and Higashijima2022) splits within incumbent parties (2, political resistance); nonviolent and violent protests (3 and 4, social resistance); and the intervention of external actors (5, external resistance).

Our analysis unveils 4 sufficient configurations associated with democratic survival during such recent 69 autocratization processes: in short, the combinations of institutional, political resistance and nonviolent actions, as well as institutional resistance, nonviolent actions, and external pressure, are the most robust. Single conditions of resistance, such as those related to institutions and political actors, can also be effective, although they are more context-dependent. However, we also found that, absent democratic resistance, democracy is not inevitably lost. Such patterns are validated across alternative analytical choices, clusters of observations (world regions, wealth, and liberal-democracy levels, episode duration), and case selections (censoring, ERT versions, etc.). The remainder of the article assesses autocratization and democratic resistance studies. Next, it illustrates the methods, data, and results through short case-based evidence from each configuration, and further research avenues.

Democracy trends and resistance to autocratization

In line with current developments in many political regimes, studies on autocratization processes have proliferated, providing valuable insights into the causes of their beginning, progression, and different outcomes. Existing research provides us with crucial information on the factors that facilitate autocratization onset, e.g., the populist, authoritarian, illiberal, or anti-pluralist tendencies of incumbent elites (Levitsky and Ziblatt Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2019; Juon and Bochsler Reference Juon and Bochsler2020; Medzihorsky and Lindberg Reference Medzihorsky and Lindberg2024). Far from taking the executive as the only initiator of autocratization, scholars have alternatively examined economic conditions (Teorell Reference Teorell2010; Haggard and Kaufman Reference Haggard and Kaufman2012; Scheve and Stasavage Reference Scheve and Stasavage2017; Haggard and Kaufman Reference Haggard and Kaufman2018; Gerring et al. Reference Gerring, Knutsen, Maguire, Skaaning, Teorell and Coppedge2021; Lachapelle and Hellmeier Reference Lachapelle and Hellmeier2024), inequalities (Houle Reference Houle2015; Leipziger Reference Leipziger2024; Panzano Reference Panzano2024), polarization-related factors (Laebens and Öztürk Reference Laebens and Öztürk2021; Somer et al. Reference Somer, McCoy and Luke2023; Hur and Yeo Reference Hur and Yeo2024), specific subnational settings (Stenberg et al. Reference Stenberg, Rocco and Farole2022; Grumbach Reference Grumbach2023), citizens’ (un)democratic values (Claassen Reference Claassen2020; Bryan Reference Bryan2023; Frederiksen and Skaaning Reference Frederiksen and Skaaning2023; Wunsch and Gessler Reference Wunsch and Gessler2023), or triggering crises (Edgell et al. Reference Edgell, Lachapelle, Lührmann and Maerz2021).

Yet, in those contexts where autocratization is underway, our understanding of the factors that shape its resolution remains more limited. Autocratization processes are known to be to a considerable extent open-ended (Nord et al. Reference Nord, Angiolillo, Lundstedt, Wiebrecht and Lindberg2025). Consequently, the initial causes and modalities of autocratization onset do not inherently predetermine its outcome (Riedl et al. Reference Riedl, McCoy, Roberts and Somer2024b). Such an outcome can rather yield a range of potential scenarios, e.g., the failure or exhaustion of the process, a return to the initial state, a change within the regime, or an outright transition to autocracy. Using a widely accepted classification of political regimes (Regimes of the World, RoW, Lührmann et al. Reference Lührmann, Tannenberg and Lindberg2018) between liberal/electoral democracies and electoral/closed autocracies (Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky and Way2010; Schedler Reference Schedler2013), Maerz et al. (Reference Maerz, Edgell, Wilson, Hellmeier and Lindberg2024) distinguish between autocratization episodes (or time frames) depending on their starting and ending points. This approach differentiates episodes resulting in a qualitative regime change (between), e.g., democratic breakdown, from episodes terminating without (within political regimes, Edgell et al. Reference Edgell, Boese, Maerz, Lindenfors and Lindberg2022; Wilson et al. Reference Wilson, Medzihorsky, Maerz, Lindenfors, Edgell, Boese and Lindberg2023).

The recognition that autocratization can lead to different outcomes is a very significant development in the literature: shortly, not all autocratization processes necessarily result in a regime change. This specification is pivotal not only for academic discussions but also for evaluating today’s global trends in democracy. Figure 1’s top panel reports the number of countries divided by the RoW categorization under autocratization and democratization episodes using the standard ERT classification (cf. infra). While autocratization episodes clearly outnumber democratization ones (in part because there are more democratic regimes today than in the past), the proportion of democratizing, stable, and autocratizing regimes does not change dramatically (bottom panel). Such clarification, still, does not contend that autocratization is the prevailing regime development: Figure 2 plots the yearly averages of negative (downturns) and positive (upturns, Teorell Reference Teorell2010) within-country and year-to-year (between t and t-1) differences in global democracy levels from the V-Dem Electoral Democracy Index (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Altman, Bernhard and Fish2025). While autocratization as a within-regime transformation currently represents the dominant trajectory in democracy trends – downturns outnumber upturns (resulting in a net negative change, Miller Reference Miller2024) – this has not translated into a massive shift toward authoritarianism (Skaaning Reference Skaaning2020; Tomini Reference Tomini2021; Treisman Reference Treisman2023).

Figure 1. Political regimes and regime transformation (ERT, RoW, V-Dem, v.15).

Figure 2. Global averages of democratic change (V-Dem, v.15).

The key question thus becomes what factors may contribute to the spectrum of autocratization outcomes. Until recently, scholars have focused mainly on the drivers of the autocratization process that – at least in democratic regimes – most studies identified in the incumbent government (cf. the concept of ‘executive aggrandizement’, Bermeo Reference Bermeo2016). When autocratization is not driven by external or extra-institutional actors (e.g., the military), researchers have examined the party- or leadership-related characteristics, decisions, and goals of the incumbent government (Günay and Dzihic Reference Günay and Dzihic2016).Footnote 1 Others have underscored the central role of institutions, e.g., in enforcing accountability (Mechkova et al. Reference Mechkova, Lührmann and Lindberg2019; Boese et al. Reference Boese, Edgell, Hellmeier, Maerz and Lindberg2021; Laebens and Lührmann Reference Laebens and Lührmann2021; Holloway and Manwaring Reference Holloway and Manwaring2023). However, a third element was absent from these contributions: the opposition in its various forms (Wegmann Reference Wegmann2022). From this perspective, we assume that analyzing the constellation of actors who oppose autocratization is crucial for determining its outcomes: democratic breakdown or survival. The article contributes to this debate by investigating (a) whether resistance actions are systematically linked to the termination of autocratization, e.g., the absence of democratic breakdown, and (b) their specific configurations explaining democratic survival. Obviously, the relationship between the ‘autocratizing incumbent’ and ‘democratic resisters’ is cumbersome, and the conclusion discusses the limitations of our research. Yet, we argue that a comparison between autocratization processes, together with a conscious evaluation of the findings, will greatly improve our understanding of this phenomenon.

Expectations

We rely on the definition of democratic resistance to autocratization developed by Tomini et al. (Reference Tomini, Gibril and Bochev2023, p. 121): ‘as any activity, or combination of activities, taken by a changing set of often interconnected and interacting actors who, regardless of the motivations, attempt at slowing down, stopping, or reverting the actions of the actors responsible for the process of autocratization’. This definition identifies institutional, political, social, and external actors resisting autocratization. It also assumes that resistance is a collective effort that can thwart autocratization, envisioning continuous interactions among different agents. In this regard, we adopt a neutral perspective on autocratization concerning the actors driving the process. Whether autocratization’s main agents are governing parties, previously opposition parties, authoritarian leaders, the military, other state institutions, or a combination of these actors, we focus on any type of action that opposes such an autocratization attempt. We reframe the current knowledge in the mainly qualitative field within this categorization. This survey of the literature identifies specific claims, which we will evaluate through a medium-N perspective.

First, institutional resisters operate within state institutions to ensure compliance with constitutional rules and democratic norms, and enforce accountability on the executive. This category includes judges at various levels of the judicial system, top bureaucrats, and officials within independent authorities, which can constrain would-be autocratic governments. The impact of precisely judicial actions on democratic backsliding has been assessed by Gibler and Randazzo (Reference Gibler and Randazzo2011) through a relatively rare large-N analysis. Their results confirm that an independent judiciary has a positive effect on democratic survival and can prevent authoritarian reversals, especially where the judicial system has been consolidated. Such findings have been corroborated qualitatively in Latin America (Gamboa Reference Gamboa2017, Reference Gamboa2022), e.g., in Brazil during Jair Bolsonaro’s presidential term (Bogéa Reference Bogéa2024), and in Hungary, Poland, and Romania (Puleo and Coman Reference Puleo and Coman2024). Institutional resistance against autocratization can also be carried out by public officials within state bureaucracies (Bauer and Becker Reference Bauer and Becker2020; Muno and Briceño Reference Muno and Briceño2023). Gamboa (Reference Gamboa2017) highlights how institutional resistance may be the most effective in reversing autocratization compared to extra-institutional strategies (in her sample of cases). This finding is echoed by Somer et al. (Reference Somer, McCoy and Luke2023), who noted that institutional strategies of resistance ‘may serve to contain abuses by a polarizing executive’ (p. 8), and Tomini et al. (Reference Tomini, Gibril and Bochev2023), who emphasized the effectiveness of such actors especially in autocratization in liberal democracies, rather than in countries without a consolidated liberal-democratic tradition (Weyland Reference Weyland2024b). Therefore, we expect that:

1. The presence of institutional resistance, e.g., judicial and administrative actions against a would-be authoritarian government, can serve as a sufficient condition to prevent democratic breakdown during autocratization processes.

Political resisters are leaders or parties acting in opposition to the incumbent that has initiated an autocratization process. They belong to the parliamentary opposition and take initiatives within national or local institutions, e.g., by organizing legislative actions against the government, forming electoral coalitions (Obydenkova and Libman Reference Obydenkova and Libman2013; Whiting and Kaya Reference Whiting and Kaya2021), or promoting an inclusive agenda toward discriminated groups (Rovny Reference Rovny2023). Cleary and Öztürk (Reference Cleary and Öztürk2022) compare cases of democratic breakdown in Turkey, Venezuela, and Thailand with democratic survival in Bolivia and Ecuador to emphasize the crucial – and, at least in these cases, successful – decision of the political opposition to keep participating in constitutional procedures in parliament and in the elections. Gamboa (Reference Gamboa2017, Reference Gamboa2022) corroborates this, highlighting the importance for the opposition to adopt parliamentary procedures to restore legislative accountability. Similarly, Tomini et al. (Reference Tomini, Gibril and Bochev2023) note that such political resistance actions can be effective even when the space of public contestation and political participation becomes more arbitrary and repressive (Cassani and Tomini Reference Cassani and Tomini2018). The importance of electoral coalitions has also been emphasized in the Polish (Solska Reference Solska2020) and Turkish cases (Selçuk and Hekimci Reference Selçuk and Hekimci2020). Somer et al. (Reference Somer, McCoy and Luke2023) similarly suggest that political rather than institutional actions may be more effective in halting autocratization, especially when such a process is already advanced. In fact, institutional actors such as courts may backfire against the opposition, especially when polarization is high and non-elected actors are perceived as illegitimate. Still, opposition coalition-building can be challenging due to various perceptions of the autocratic threat and the interests of democratic ‘defenders’ (Nok Hin et al., Reference Nok Hin, Ka Ming and Ka Lun2024; van Lit et al., Reference van Lit, van Ham and Meijers2024).

However, the opposition is not the only political actor to be considered here. Some factions within the incumbent party or coalition may break away from a government that is becoming increasingly autocratic. Resistance studies have in fact mentioned the central role of incumbent divisions (Cleary and Öztürk Reference Cleary and Öztürk2022; Lührmann and Merkel Reference Lührmann and Merkel2023; Somer et al. Reference Somer, McCoy and Luke2023; Tomini et al. Reference Tomini, Gibril and Bochev2023). As discussed in democratization theories (O’Donnell et al. Reference O’Donnell, Schmitter and Whitehead2013[1986]), ‘soft liners’ within the incumbent can be relevant actors in blocking autocratization. Within autocracies, similarly, del Río (Reference del Río2022) has illustrated how, under certain circumstances – e.g., during a crisis or upon bottom-up social pressure – autocratic elites may defect, potentially opening the way to a regime liberalization. We therefore expect that:

2. The presence of political resistance, e.g., the use of accountability procedures within parliament, the formation of electoral coalitions and alliances among opposition parties, or divisions within the incumbent party (or parties), can serve as a sufficient condition to prevent democratic breakdown during autocratization processes.

Social resisters represent actors able to mobilize the society: non-governmental organizations, grassroots, or cultural movements. They can rally citizens in support of specific causes, organize public events, e.g., strikes, protests, marches, or demonstrations, and engage in organized dissent against the autocratizing government. These actions serve to sensitize public opinion to promote broader political change (Bermeo Reference Bermeo2003; Alemán and Yang Reference Alemán and Yang2011; Markoff Reference Markoff2015; Dahlum et al. Reference Dahlum, Knutsen and Wig2019; Tong and Cheng Reference Tong and Cheng2022). Tomini et al. (Reference Tomini, Gibril and Bochev2023) have mentioned the importance of peaceful social mobilization, especially when institutional channels are no longer viable (as in electoral autocracies). This is supported by case studies (Cleary and Öztürk Reference Cleary and Öztürk2022), e.g., in Sub-Saharan Africa, where Rakner (Reference Rakner2021) provides evidence of how democratic resistance can succeed when social mobilization is peaceful or even issue-based (cf. M. Truong Reference Truong2024). However, their rate of success depending on the identity and methods of the social resisters has been questioned by quantitative research, which suggests that while having a general positive effect, pro-democratic mobilization alone may not always be sufficient to prevent democratic collapse (Hellmeier and Bernhard Reference Hellmeier and Bernhard2023). It thence appears that social actions work more effectively when combined with actions at different levels, whether in the political, institutional, or external arenas (Sjögren Reference Sjögren2024). Others (Gamboa Reference Gamboa2017) even categorize these actions as ‘extra-institutional strategies’, underlining how they can be ineffective or counterproductive in ensuring democratic survival.

These considerations apply specifically to violent mobilizations. However, although conventional wisdom may suggest that violent protests can have detrimental effects on democracy, especially during autocratization processes, in the literature there is also a more nuanced account of violent protests and democratization (Della Porta et al. Reference Della Porta, Donker, Hall, Poljarevic and Ritter2017; Kim and Kroeger Reference Kim and Kroeger2019; Marino et al. Reference Marino, Donni, Bavetta and Cellini2020), with some contributions showing how parties formerly at the forefront of violent movements, when they institutionalize and renounce violence, may provide legitimacy to new democracies (Ishiyama Reference Ishiyama2018). We consequently anticipate that:

3. The presence of social resistance, e.g., non-violent protests against a would-be authoritarian government, can serve as a sufficient condition to prevent democratic breakdown during autocratization processes. Moreover, social resistance serves as an INUS condition, an insufficient but necessary part of a larger, jointly sufficient set of democratic resistance actions.

4. Violent protests exhibit an ambiguous impact, contributing inconsistently to the prevention of democratic breakdown.

Finally, external resisters encompass state- and non-state-based collective actors capable of supporting democratic resistance from abroad. It is well known how autocratic linkages can legitimize would-be authoritarian leaders externally (Tansey et al. Reference Tansey, Koehler and Schmotz2017; Kneuer and Demmelhuber Reference Kneuer and Demmelhuber2020). Coming from democratic actors, pro-democracy policies can leverage international influence (Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky and Way2006; Levitz and Pop-Eleches Reference Levitz and Pop-Eleches2010; Tolstrup Reference Tolstrup2013) to enforce the rule of law and promote democratic reforms through conditionality, aid to domestic NGOs (Carothers Reference Carothers2011), or direct methods, i.e., imposing sanctions (Von Soest and Wahman Reference Von Soest and Wahman2015). Such external actors can engage in various activities, e.g., fostering cultural exchanges, supporting opposition parties, advocating for democracy, and initiating cooperation projects with domestic non-state actors (Lavenex and Schimmelfennig Reference Lavenex and Schimmelfennig2011). However, when international agents intervene, their actions are often seen to complement domestic actors (Gamboa Reference Gamboa2022), rather than as a primary source of resistance. This can also explain the various effectiveness of such external pressures (Jenne and Mudde Reference Jenne and Mudde2012; Džankić et al. Reference Džankić, Keil and Kmezić2018; Carothers Reference Carothers2024). We therefore expect that:

5. External pro-democracy actors opposing a would-be authoritarian government can contribute to averting democratic breakdown during autocratization processes. Moreover, external resistance serves as an INUS condition, an insufficient but necessary part of a larger, jointly sufficient set of democratic resistance (domestic) actions.

Such studies on democratic resistance are flourishing. However, they might still suffer from serious inconsistencies. First, it remains unclear the extent to which the conclusions recapitulated earlier can be extended beyond these case studies (external), and whether such findings are to be understood as causal or descriptive arguments (internal validity). Indeed, most of these case-based analyses – while empirically rich – do not always present a well-articulated case selection strategy, which could lead to a potentially biased interpretation of the results (Geddes Reference Geddes2003) and of alternative explanations (Møller Reference Møller2013; Slater and Ziblatt Reference Slater and Ziblatt2013). Second, rather than considering one single aspect (or single type of actor) of democratic resistance, it is necessary to systematically examine the joint impact of its possible combinations. Some of the discrepancies of the aforementioned studies can be addressed by simply hypothesizing that, even if the success of a single resistance strategy can be context-dependent and difficult to consider as a ‘model’, what matters the most is that such resistance actions occur together across different arenas, maximizing relative strengths and minimizing weaknesses of a variety of institutional, political, social, and external actions. Such coordinated resistance (unity makes strength) can be more effective in protecting democracy across various contexts and stages of autocratization:

6. The combination of resistance actors across different dimensions (institutional, political, social, or external) is the most robust sufficient configuration for averting democratic breakdown during autocratization processes.

A configurational analysis

Case selection

We base our case selection on version 14 of the Episodes of Regime Transformation (ERT, Maerz et al. Reference Maerz, Edgell, Wilson, Hellmeier and Lindberg2024) framework centered on the Varieties of Democracy project (V-Dem version 14, Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Altman, Bernhard and Fish2025, with data until 2023). The ERT adopts the electoral definition of democracy of the V-Dem Polyarchy Index or Electoral Democracy Index (EDI, 0-1).Footnote

2

The ERT codebook (Edgell et al. Reference Edgell, Maerz, Maxwell, Morgan, Medzihorsky, Wilson, Boese, Hellmeier, Lachapelle and Lindenfors2024) specifies inclusion thresholds for coding as autocratization episodes those time frames with a significant and durable decline of the EDI, including the minimum annual change required to initiate an episode (

![]() $\! -$

0.01) and a cumulative inclusion score (

$\! -$

0.01) and a cumulative inclusion score (

![]() $\! -$

0.1). Using these criteria, 52 autocratization episodes (in 46 countries) can be identified in (liberal or electoral) democracies since 2000.Footnote

3

$\! -$

0.1). Using these criteria, 52 autocratization episodes (in 46 countries) can be identified in (liberal or electoral) democracies since 2000.Footnote

3

This sample contains cases that are central to democratic resistance studies, e.g., Venezuela (1998–2018), North Macedonia (2005–13), or South Korea (2008–13). However, some cases that experienced significant declines in the EDI but did not reach the

![]() $\! -$

0.1 threshold are excluded. Notable examples include the US under Donald Trump’s first administration (2016–20, EDI from 0.91 to 0.85, Levitsky and Ziblatt Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2019) or Israel under Benjamin Netanyahu (Prime Minister 1996–99, 2009–21, 2022–, EDI from 0.76 to 0.72 between 2009 and 2023; Gidron Reference Gidron2023). Following the ERT standard thresholds, such an operationalization identifies only 25 autocratization episodes without an event of democratic breakdown, which is coded by the ERT as the shift of a political regime toward (electoral and closed) autocracies (Lührmann et al. Reference Lührmann, Tannenberg and Lindberg2018), plus the occurrence of a first election in the new autocratic regime or a 5-year permanence period.Footnote

4

$\! -$

0.1 threshold are excluded. Notable examples include the US under Donald Trump’s first administration (2016–20, EDI from 0.91 to 0.85, Levitsky and Ziblatt Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2019) or Israel under Benjamin Netanyahu (Prime Minister 1996–99, 2009–21, 2022–, EDI from 0.76 to 0.72 between 2009 and 2023; Gidron Reference Gidron2023). Following the ERT standard thresholds, such an operationalization identifies only 25 autocratization episodes without an event of democratic breakdown, which is coded by the ERT as the shift of a political regime toward (electoral and closed) autocracies (Lührmann et al. Reference Lührmann, Tannenberg and Lindberg2018), plus the occurrence of a first election in the new autocratic regime or a 5-year permanence period.Footnote

4

As we focus on democratic resistance to autocratization, we remain flexible with the ERT thresholds. Although such baseline operationalization has been obtained through multiple validity tests, what is the necessary amount of decay on a democracy index to score an autocratization episode is an empirical more than a theoretical question. For instance, some successful instances of democratic resistance (resulting in a EDI decrease of 0.09 instead of 0.1) might be excluded from the analysis if we are too rigid with such a definition.

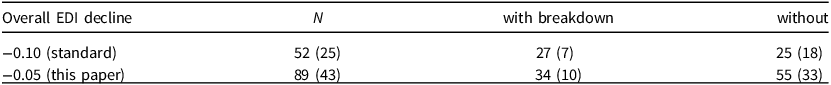

Therefore, we have re-operationalized autocratization episodes in the minimum overall decline of the EDI: with the R ERT package (Edgell et al. Reference Edgell, Maerz, Maxwell, Morgan, Medzihorsky, Wilson, Boese, Hellmeier, Lachapelle and Lindenfors2024), we have lowered the cumulative threshold to reach a more permissive

![]() $-$

0.05 of the EDI to include those cases with a significant decline in democratic quality, still higher than the minimum annual value (cf. Wiebrecht et al. Reference Wiebrecht, Sato, Nord, Lundstedt, Angiolillo and Lindberg2023). By expanding the autocratization episode pool to 89 (including 72 countries that autocratized since 2000 within democratic regimes), we have assembled a larger dataset that facilitates testing our expectations, specifically about the success of democratic resistance. This larger dataset provides a more diverse range of cases, including a larger amount of autocratization episodes without regime change (55), without omitting relevant cases – often included in the small-N studies described above – ended before the last measurement (2023, Table 1). This is our baseline case selection. However, different thresholds and ERT versions (up to 2024) are tested as well in our analysis.

$-$

0.05 of the EDI to include those cases with a significant decline in democratic quality, still higher than the minimum annual value (cf. Wiebrecht et al. Reference Wiebrecht, Sato, Nord, Lundstedt, Angiolillo and Lindberg2023). By expanding the autocratization episode pool to 89 (including 72 countries that autocratized since 2000 within democratic regimes), we have assembled a larger dataset that facilitates testing our expectations, specifically about the success of democratic resistance. This larger dataset provides a more diverse range of cases, including a larger amount of autocratization episodes without regime change (55), without omitting relevant cases – often included in the small-N studies described above – ended before the last measurement (2023, Table 1). This is our baseline case selection. However, different thresholds and ERT versions (up to 2024) are tested as well in our analysis.

Table 1. ERT autocratization episodes and outcomes since 2000

Ongoing cases (in 2023) in parenthesis, ERT v.14.

Empirical strategy

As we are interested in various patterns of resistance actions associated with democratic survival in autocratization episodes, we adopt a qualitative comparative analysis (QCA, Rihoux and Ragin Reference Rihoux and Ragin2008; Schneider and Wagemann Reference Schneider and Wagemann2012). The QCA logic espouses an outcome-centered perspective to assess the generalization potentials of case-based experiences as broader, comparative cross-case patterns. Being rooted in set theory and Boolean algebra, QCA is designed to deal with causal complexity (Schneider and Wagemann Reference Schneider and Wagemann2012), such as the absence of democratic breakdown resulting from different configurations (equifinality) of multiple resistance actions (conjunctural causation).

We set the unit of analysis at the autocratization-episode level. To measure Table 1’s last column (democratic survival or the absence of democratic breakdown), we use the ERT codification, which adopts the RoW categorization – applying a series of sequential thresholds to certain indicators from the V-Dem dataset to distinguish between liberal/electoral democracies and electoral/closed autocracies (Lührmann et al. Reference Lührmann, Tannenberg and Lindberg2018) – to which it adds a first election in the new autocratic regime or a 5-year permanence period in the new regime, as mentioned previously.Footnote 5 A binary condition is created to indicate the outcome: the presence (1) or absence (0) of democratic breakdown during the autocratization episode (‘DBR’). This coding includes shifts from liberal or electoral democracies to autocratic regimes, or sequences involving both types of regime change (from liberal to electoral democracy and then to electoral autocracy, e.g., Hungary since the second term of Viktor Orbán as Prime Minister, 2010-). Other autocratization episodes that do not correspond to this scenario (i.e., without a democratic breakdown in the episode or before the last measurement in 2023) are assigned a value of 0. As Table 1 shows, this gives us a sufficiently large set to test for cases in which resistance actions successfully reverse autocratization (even if they involve relatively small variations in democratic quality in episodes without regime change).

To measure democratic resistance, we use the Democratic Erosion Event Dataset (DEED, version 6, Gottlieb et al. Reference Gottlieb, Blair, Baron, Arugay, Ballard-Rosa, Davidson, Gamboa, Grossman, Grossman, Kulich-Vamvakas, Lapp, McCoy, Robinson, Rosenzweig, Royer, Schneider, Stokes and Turnbull2023, Baron et al. Reference Baron, Blair, Gottlieb and Paler2024). The DEED codes events of democratic resistance to autocratization based on expert codification of factual data, e.g., the occurrence of a protest against a would-be authoritarian government, from press releases. We select only such DEED indicators that are consistent with our theoretical framework and restricted to the events collected for the years that overlap with our list of autocratization episodes. Because of DEED’s limitations, we could collect events of democratic resistance in 69 of the 89 episodes between 2000 and 2023 reported in Table 1.Footnote 6 We consider ongoing autocratization episodes – if they do not involve a democratic breakdown – along with autocratization episodes that ended before the last year of measurement and without a regime change. Although autocratization may not be complete, such cases have not yet experienced a democratic collapse, which we interpret as successful resistance. The analysis is nonetheless replicated with alternative choices regarding episode duration and truncated cases.

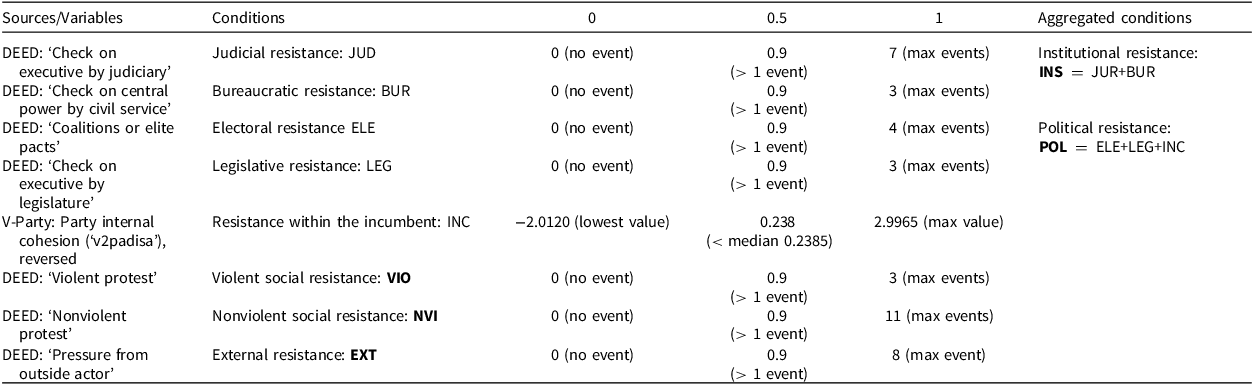

We are interested in whether such episodes include events, as coded by DEED experts, related to democratic resistance. First, we take a set of variables from the DEED indicators that encode checks on the executive by the judiciaryFootnote 7 and the civil service (e.g., autonomous bureaucratic agencies or civil servants),Footnote 8 the parliament,Footnote 9 electoral coalitions against the autocratizing government,Footnote 10 violent or non-violent protests,Footnote 11 and actions from external powers in support of democracy.Footnote 12 We also consider the extent to which the autocratizing elite is cohesive: for this, we use the internal party cohesion index from the Varieties of Party Identity and Organization dataset (V-Party, Lindberg et al. Reference Lindberg, Düpont and Higashijima2022).Footnote 13

Given the nature of our data, we use the fuzzy set (fs) direct calibration. Since the dataset is organized at the autocratization-episode level and DEED is an event format, we calculated the total number of resistance events within each autocratization episode. We then set the 0.5 qualitative anchor to 0.9 to consider the presence of one event as a manifestation of being more in than out of the set membership of the said condition. In some cases, in fact, especially in short autocratization episodes, a single significant event – e.g., a successful impeachment procedure carried out by the parliamentary opposition – may be decisive. Concerning the V-Party condition at the election-year level, for each episode we calculated the mean of those cohesion scores for incumbent parties in the elections during the autocratization episodes. We did not weight such an indicator for party seat share, as small parties are frequent defectors. We rather inverted the variable (to see the extent to which incumbent parties are not cohesive) and set our qualitative anchor of 0.5 below the median. For all conditions, the 0/1 anchors are the minimum/maximum number of resistance events or reverse cohesion index scores: we fit the data between these anchors via the logistic function (Table 2).

While the DEED provides a fine-grained categorization of such events, the number of conditions in a fsQCA setup is limited to avoid issues of limited diversity, i.e., combinations of conditions without empirical referents and, consequently, overly complex solution formulas. Hence, a further aggregation procedure is necessary. From 8 possible indicators of resistance actions (Table 2’s second column), we combine the calibrated conditions via the logical OR (Boolean addition ‘+’), as we interpret some individual conditions derived from the DEED or V-Party variables as instances of two broader dimensions of democratic resistance. The condition of institutional resistance (‘INS’) is based on whether the autocratization episode has membership in the sets of judicial (‘JUD’) or bureaucratic (‘BUR’) resistance, and political resistance (‘POL’) whether it has membership in the sets of electoral (‘ELE’), legislative (‘LEG’), or intra-incumbent (‘INC’) resistance (Table 2’s last column). We keep the two social resistance conditions as separate since we expect that there might be a divergent impact for violent (‘VIO’) and nonviolent (‘NVI’) protests. The same goes for external democratic pressure (‘EXT’). We still test individual conditions as a robustness test.

Table 2. Operationalization and calibration of the conditions

The online Appendix includes the raw and calibrated data (Tables A.1 and A.2), graphs of conditions and variables, and the calibration diagnostics (Figures A.1 and A.2). The conditions of judicial, bureaucratic, legislative, and electoral resistance have skewed membership (most autocratization episodes have very few events of such type), which further justifies their aggregation.

Results

The necessity analysis looks at conditions that are necessary (or supersets) for the absence of democratic breakdown, meaning that there is no observable case of democratic survival where such conditions are absent. We did not get any single condition above meaningful consistency thresholds (Appendix Table A.3), neither necessary disjunctions nor SUIN conditions, combined with the logical OR (Oana et al. Reference Oana, Schneider and Thomann2021).Footnote 14 This already tells us that democratic resistance to autocratization is largely context-dependent, as there is no condition (or combination of conditions) that is always present where democracy survives.

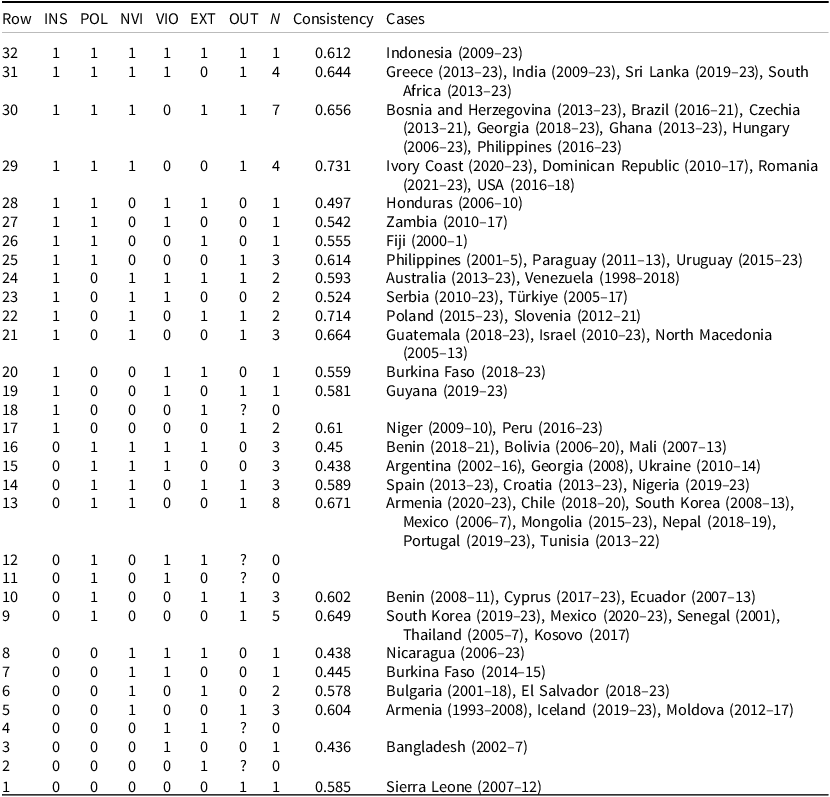

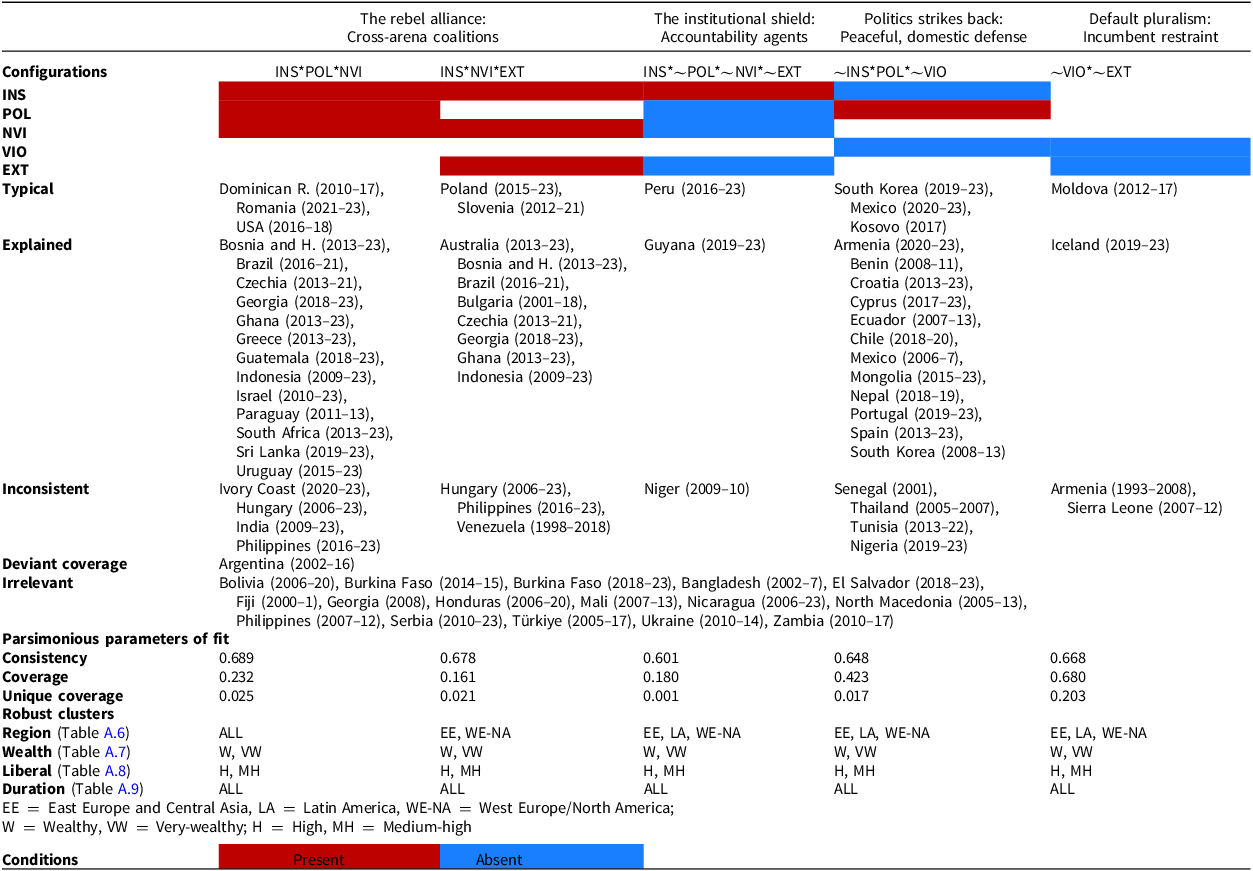

In the sufficiency analysis, the truth table (Table 3) illustrates all logical combinations and empirical references (‘?’ when missing) of democratic resistance actions for the absence of democratic breakdown (OUT = 1).Footnote 15 Simplifying such a truth table, Table 4 shows the parsimonious formula looking at whether conditions are present or absent,Footnote 16 labels specific configurations, and assigns cases. We further report the typical cases of each solution term (presenting the configurations), the others explained (by such configurations), the inconsistent ones (included in the truth table minimization even though they have democratic breakdown), and finally those cases deviant in coverage (without democratic breakdown and not covered by any solution term) and irrelevant (with democratic breakdown and not explained). The solution covers 42 out of 43 cases of democratic survival in autocratization episodes started in democracies included in the analysis.

Table 3. Truth table for the absence of democratic breakdown

Table 4. Baseline sufficiency solution: cases and clusters

At the bottom, the table is integrated with cluster diagnostics (Thiem et al. Reference Thiem, Spöhel and Duşa2016; Oana and Schneider Reference Oana and Schneider2021) – a procedure that has been developed to examine whether the QCA solutions are affected by ‘omitted variable bias’: whether specific configurations occur systematically in certain subsets of cases, hiding factors relevant for the outcome. First, we divide such autocratization episodes into six political regions (V-Dem). Second, we cluster countries depending on their GDP per capita (Fariss et al. Reference Fariss, Anders, Markowitz and Barnum2022; in V-Dem): although we concentrate on actor-based conditions, regional factors or economic structures might still be relevant to determine specific agents’ possibilities and choices. Third, we cluster on the solidity of liberal-democratic institutions at the beginning of autocratization (V-Dem liberal component index),Footnote 17 as the occurrence of a democratic breakdown can be affected by being closer to a mid-level of democratic consolidation before autocratization starts. We also cluster on episode duration, which may affect different frequencies of resistance events.

We are now able to identify four patterns of successful democratic resistance to autocratization (i.e., autocratization episodes without democratic breakdown), or combinations of conditions that are sufficient for democratic survival. We define the first pattern as The rebel alliance: Cross-arena coalitions, and observe its manifestation in the first two columns of Table 4. We interpret these two configurations together since they share core mechanisms, with 6 cases commonly explained (6 out of 16 for the first configuration ‘INS*POL*NVI’ and 6 out of 10 for the second configuration, ‘INS*NVI*EXT’, for a total amount of 20 cases explained). In the context of ‘The rebel alliance’, institutional resistance combines with non-violent protests from civil society as fundamental components, which is complemented by political resistance actions by domestic actors (Table 4’s first) or external pressure (and second column). This pattern underscores the importance of collaborative and multiple resistance for the prevention of democracy.

A notable illustration is Poland and the demise of the governments of the Law and Justice Party (2015–2023, Prawo i Sprawiedliwość, PiS; with Beata Szydło, 2015–17, and Mateusz Morawiecki, 2017–23, as prime ministers, and Andrzej Duda as president, 2015–25). Confronted with autocratizing tendencies within the government – which culminated in the restriction of judicial independence, media outlets, and reproductive rights (Przybylski Reference Przybylski2018) – the Polish example demonstrates how a broad coalition of actors successfully resisted and eventually replaced the incumbent government through free and fair elections in October 2023 and the appointment of Donald Tusk as prime minister – despite facing a tilted playing field and institutional encroachments by the PiS. Resistance by Polish judges against breaches of the rule of law (Puleo and Coman Reference Puleo and Coman2024) received support from civil society that mobilized against various fronts, including abortion rights (Korolczuk Reference Korolczuk2016), without resorting to violence. External actors such as the European Commission and the European Court of Justice contributed to putting pressure on the government on the rule of law matter (Pech et al. Reference Pech, Wachowiec and Mazur2021), while the political opposition skillfully negotiated an electoral coalition that prevented another PiS victory in 2023. Beyond such paradigmatic cases, such coalition-based resistance, resulting in two sufficient configurations, represents the most broadly applicable combination to other fundamental cases of democratic survival (e.g., the US and Brazil).

But the QCA reveals other configurations of democratic survival. We define the second pattern ‘INS*

![]() $\sim$

POL*

$\sim$

POL*

![]() $\sim$

NVI*

$\sim$

NVI*

![]() $\sim$

EXT’ as The institutional shield: Accountability agents (third column of Table 4). Here, institutional actors such as judges and bureaucrats are the main agents in a context where there are no other major actions from the side of political, social, or external actors. This configuration is the least representative, explaining only 2 cases of our sample. Nonetheless, it still sheds external validation on the centrality of institutional resistance, which is the only core condition present in the absence of all others. That is exemplified by the autocratization episode in Peru (2016–2023), under cycles of economic crises, political instability (and even would-be authoritarian leaders, such as President Pedro Castillo, 2021–2022, before a successful third impeachment attempt by the Parliament – not covered by the data collection), and social unrest (Barrenechea and Vergara Reference Barrenechea and Vergara2023). Democracy did not collapse in this case, also because of the strong actions of the judiciary, among which the DEED reports the reversal of President Pedro Pablo Kuczynski’s pardon of former (and authoritarian) president Alberto Fujimori (1990–2000).

$\sim$

EXT’ as The institutional shield: Accountability agents (third column of Table 4). Here, institutional actors such as judges and bureaucrats are the main agents in a context where there are no other major actions from the side of political, social, or external actors. This configuration is the least representative, explaining only 2 cases of our sample. Nonetheless, it still sheds external validation on the centrality of institutional resistance, which is the only core condition present in the absence of all others. That is exemplified by the autocratization episode in Peru (2016–2023), under cycles of economic crises, political instability (and even would-be authoritarian leaders, such as President Pedro Castillo, 2021–2022, before a successful third impeachment attempt by the Parliament – not covered by the data collection), and social unrest (Barrenechea and Vergara Reference Barrenechea and Vergara2023). Democracy did not collapse in this case, also because of the strong actions of the judiciary, among which the DEED reports the reversal of President Pedro Pablo Kuczynski’s pardon of former (and authoritarian) president Alberto Fujimori (1990–2000).

We label the third pattern Politics strikes back: Peaceful, domestic defense. It explains 15 cases in which democratic breakdown was prevented not through resorting to violent mobilizations and institutional resistance but rather through the decisive involvement of political actors (‘

![]() $\!\sim$

INS*POL*

$\!\sim$

INS*POL*

![]() $\sim$

VIO’). An illustrative case is South Korea during the presidency of Park Geun-hye (2013–2017). South Korea’s autocratization was primarily driven by government misuse of intelligence agencies, media manipulation orchestrated by the president, government involvement in corruption scandals, intimidation of journalists, and power abuses (Croissant and Haynes Reference Croissant and Haynes2021). Civil society took decisive action through mass peaceful protests in 2017, compelling the political opposition to initiate impeachment proceedings against the president. Faced with widespread protests and public pressure, Park’s Saenuri Party fractured, with one faction of the party ultimately voting in favor of the impeachment. President Park’s powers and duties were suspended, leading to her removal from office following the Constitutional Court’s approval of the impeachment. This case vividly illustrates the pivotal and proactive role played by civil society through non-violent protests, as well as the subsequent actions taken by pressured political actors. Interestingly, this pattern of resistance was successfully repeated by South Korea recently in response to the martial law declared by President Yoon Suk Yeol in December 2024.

$\sim$

VIO’). An illustrative case is South Korea during the presidency of Park Geun-hye (2013–2017). South Korea’s autocratization was primarily driven by government misuse of intelligence agencies, media manipulation orchestrated by the president, government involvement in corruption scandals, intimidation of journalists, and power abuses (Croissant and Haynes Reference Croissant and Haynes2021). Civil society took decisive action through mass peaceful protests in 2017, compelling the political opposition to initiate impeachment proceedings against the president. Faced with widespread protests and public pressure, Park’s Saenuri Party fractured, with one faction of the party ultimately voting in favor of the impeachment. President Park’s powers and duties were suspended, leading to her removal from office following the Constitutional Court’s approval of the impeachment. This case vividly illustrates the pivotal and proactive role played by civil society through non-violent protests, as well as the subsequent actions taken by pressured political actors. Interestingly, this pattern of resistance was successfully repeated by South Korea recently in response to the martial law declared by President Yoon Suk Yeol in December 2024.

Lastly, QCA identifies a fourth pattern that we define as Default pluralism: Incumbent restraint (Way Reference Way2015). This concept captures situations where, even in the absence of active resistance from institutional or social actors, autocratization does not culminate in the establishment of a fully autocratic regime, either because this outcome was never envisioned by the ruling elites (see Iceland, a case that is really borderline or measurement noise, as it presents really moderate democratic decline) or because they lack the capacity to implement it (see Moldova). According to Way (Reference Way2015), this outcome may occur because autocrats often lack the organization, authority, or coordination to steal elections, impose censorship, repress opposition, or keep allies in line. In such cases, the failure to consolidate authoritarian power stems not from opposition but from the lack of real authoritarian aims or internal weaknesses within the ruling elite – organizational incoherence, institutional fragmentation, or weak coercive capacity (Treisman Reference Treisman2020). Regimes thus enter a limbo, where the autocratization ambitions are present, without the means to implement them.

This dynamic aligns with the findings of our comparative analysis. In some cases, in short, the absence of organized resistance does not systematically lead to a successful regime change: authoritarian elites may lose elections, fail to control the media environment, or struggle to maintain elite cohesion, leading to stalled autocratization. This challenges the common assumption that once resistance disappears, autocratization will inevitably proceed. Instead, it highlights the contingent and non-linear nature of the process (Cianetti and Hanley Reference Cianetti and Hanley2021) and that resistance is not the only factor shaping autocratization outcomes. While we here focused on resistance, other structural or contingent variables – e.g., state capacity, economic constraints, intra-elite authoritarian politics, and international dynamics – can play a role. However, our analysis shows that an incomplete trajectory of autocratization without democratic resistance depends on two conditions: the absence of violent protest and external interventions. When opposition actors resort to political violence, regimes often find justification to intensify repression and curtail democratic freedoms, accelerating autocratization (Gamboa Reference Gamboa2022). Instead, in the absence of such violent protests, governments may lack the perceived legitimacy or incentive to escalate authoritarian measures. Also, foreign actors might have a destabilizing interference. In contrast, when no external actors intervene, governments may be more cautious or less capable of pushing through authoritarian reforms.

To what extent are these configurations robust across autocratization episodes? From Table 4’s overview of the cluster diagnostics, we can conclude that the different terms of the solution formula are consistent in some regions but less so in others. Important exceptions are countries in Asia and the Pacific and Sub-Saharan Africa (Appendix Figure A.7), with very poor GDP per capita (Appendix Figure A.8) and unconsolidated liberal-democratic institutions (Appendix Figure A.9). Although these cases warrant a more specific study, this is in line with scholarship connecting regime breakdown to situations of low income (Alemán and Yang Reference Alemán and Yang2011; Djuve et al. Reference Djuve, Knutsen and Wig2020; Mazepus and Toshkov Reference Mazepus and Toshkov2022), issues of state building and capacity (Bratton and Chang Reference Bratton and Chang2006; Fortin Reference Fortin2012), and defective democratic quality. Clearly, these are the cases where democratic resistance is the least effective, and the configurational analysis (related to democratic resistance only) cannot identify appropriate configurations. Still, our findings equally relate to autocratization episodes of various lengths (Appendix Figure A.10).

Validations

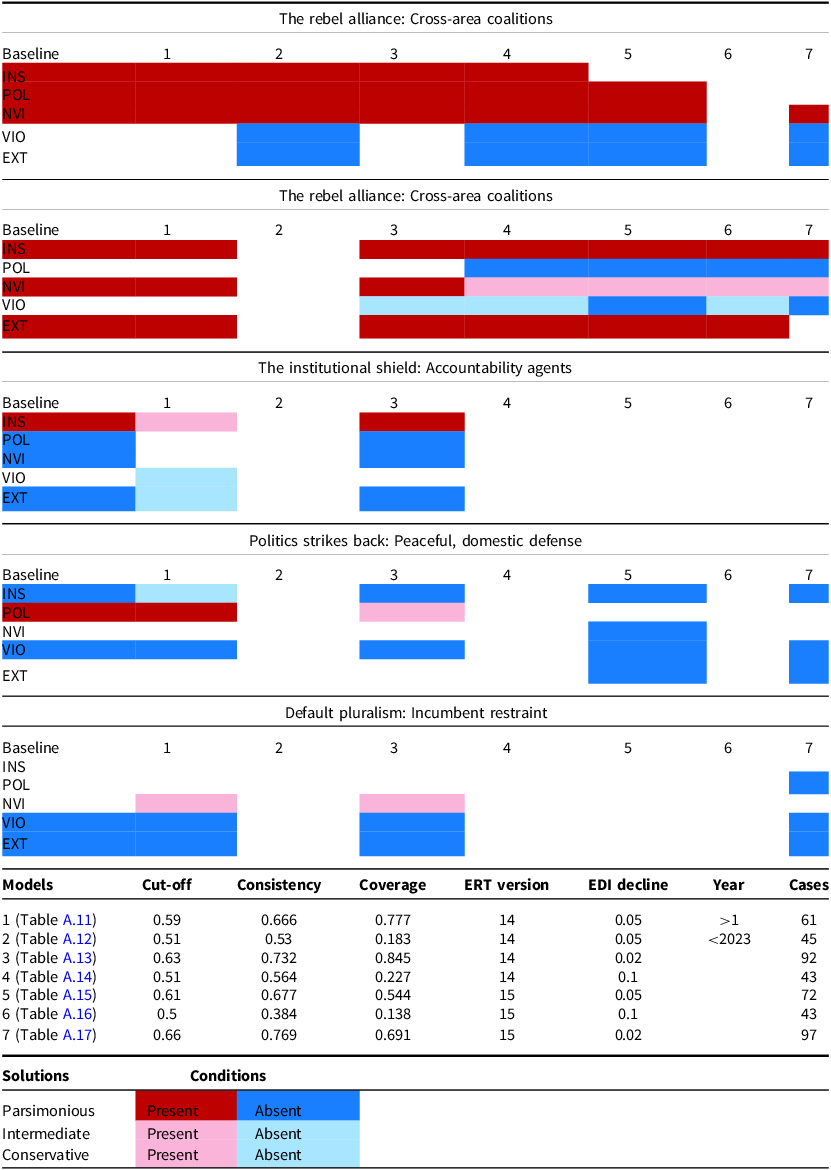

Building on previous critiques of QCA (Skaaning Reference Skaaning2011; Paine Reference Paine2016), recent techniques have been developed to make configurational analyses more transparent and robust (Oana and Schneider Reference Oana and Schneider2021; Oana et al. Reference Oana, Schneider and Thomann2021). After cluster diagnostics, our series of validations continues by illustrating how the baseline sufficiency analysis remains unchanged when adopting more restrictive rules to minimize the truth table (Enhanced Standard Analysis, Schneider and Wagemann Reference Schneider and Wagemann2012), and is comparable with a disaggregated list of institutional and political resistance conditions, e.g., emphasizing the importance of judicial institutions and the combination of incumbent resistance and external support (Appendix Table A.5). We then test whether the baseline analysis is sensitive to different operationalizations of short and truncated cases, as well as ERT thresholds and versions. Inspired by Rubinson (Reference Rubinson2019) and Haesebrouck (Reference Haesebrouck2023), Table 5 reports the parsimonious, intermediate, and conservative solutions (the latter adding contextual elements to core associations, cf. Baumgartner Reference Baumgartner2015), simplifying truth tables resulting from multiple case selections. The table compares the results to the configurations of the baseline analysis, following the so-called Fiss logic (Ragin and Fiss Reference Ragin and Fiss2008; Fiss Reference Fiss2011): conditions from parsimonious solutions (core) are in full, and those from intermediate and conservative formulas (contributory) are in lighter colors.

Table 5. Alternative case selections (parsimonious parameters of fit)

We examine numerous alternative case selections. First, we test whether the baseline analysis is robust if we exclude cases that lasted only one year, to avoid having cases that did not involve a democratic breakdown because they could simply have been too brief – and not because of the impact of democratic resistance actions. In this case (Table 5’s model 1, Appendix Table A.11), the configurations are broadly comparable. Second, to avoid issues with censored data (the ERT version 14 is censored in 2023), we replicate the analysis excluding ongoing autocratization episodes without democratic breakdown (before 2024), which yields robust results for the first combination on cross-arena coalitions (Table 5’s model 2, Appendix Table A.12). Third, we further lower the ERT inclusion threshold to

![]() $-$

0.02 to increase our sample and include more autocratization episodes with DEED recorded events (Table 5’s model 3, Appendix Table A.13): the results are convergent for the first two configurations, while the other configurations are retrieved in intermediate and conservative solutions. Fourth, we redo the analysis with the ERT standard thresholds (

$-$

0.02 to increase our sample and include more autocratization episodes with DEED recorded events (Table 5’s model 3, Appendix Table A.13): the results are convergent for the first two configurations, while the other configurations are retrieved in intermediate and conservative solutions. Fourth, we redo the analysis with the ERT standard thresholds (

![]() $-$

0.1 of EDI) and a reduced set of cases to concentrate on episodes with a really severe democratic decline: despite a lower coverage, we retain similar configurations to the first configuration of the baseline analysis (Table 5’s model 4, Appendix Table A.14). Equivalent considerations apply to parallel analyses performed comparing our analysis with ERT version 15 (on comparing ERT versions, cf. Pelke and Croissant Reference Pelke and Croissant2021; McGuire Reference McGuire2024), available since spring 2025 (Table 5’ models 5-6-7, Appendix Tables A.15, A.16, and A.17), where the validity of ‘The rebel alliance’ is the most robust. Finally, we test whether the baseline analysis is consistent with different cut-offs. With the R SetMethods package (Oana and Schneider Reference Oana and Schneider2018), we found that our solution is sensitive to the cut-off choice; however, parsimonious solutions with other (higher/lower) cut-offs broadly confirm the first configurations (Appendix Table A.10).Footnote

18

$-$

0.1 of EDI) and a reduced set of cases to concentrate on episodes with a really severe democratic decline: despite a lower coverage, we retain similar configurations to the first configuration of the baseline analysis (Table 5’s model 4, Appendix Table A.14). Equivalent considerations apply to parallel analyses performed comparing our analysis with ERT version 15 (on comparing ERT versions, cf. Pelke and Croissant Reference Pelke and Croissant2021; McGuire Reference McGuire2024), available since spring 2025 (Table 5’ models 5-6-7, Appendix Tables A.15, A.16, and A.17), where the validity of ‘The rebel alliance’ is the most robust. Finally, we test whether the baseline analysis is consistent with different cut-offs. With the R SetMethods package (Oana and Schneider Reference Oana and Schneider2018), we found that our solution is sensitive to the cut-off choice; however, parsimonious solutions with other (higher/lower) cut-offs broadly confirm the first configurations (Appendix Table A.10).Footnote

18

Discussion and conclusion

What can prevent democratic collapse? Why do some democracies survive autocratization episodes, while others do not? This article has applied the most developed QCA tools to advance the literature on democratic resistance to autocratization. It has done so by strengthening the validity of previous case studies and illustrating successful patterns of democratic survival in a mid-size sample of autocratizing democracies. This is a highly topical and fundamental research question: even though autocratization (in its various forms, but particularly as a gradual decline of democratic quality) affects many countries worldwide, qualitative regime changes such as democratic breakdown remain overall rare. We have therefore gathered evidence from 69 autocratization episodes started in democracies in the 21st century and evaluated which conditions of institutional, political, social, and external resistance actions can be systematically related to patterns of democratic survival.

The article shows consolidated evidence that the success of democratic resistance actions against autocratization is, to a certain extent, context-dependent. There is no single or combination of necessary factors that can prevent democracies, when they enter an autocratization episode, from collapsing. The autocratizing project of the incumbent elites is rather reverted by a variety of actions, such as the activism of the judiciary, or the political opposition forces, or even social movements. Our results thus corroborate most assumptions of previous small-N research and their internal and external validity. First, our examination confirms and extends to a larger sample of autocratization episodes those claims on the positive impact on democracy of institutional resistance (expectation 1). Such a factor is a core sufficient condition in two patterns out of four (present also in isolation in what we call ‘The institutional shield’). When judges or high bureaucrats speak out against the dangers for democracy of autocratizing elites, and when they take direct actions to face breaches of the rule of law, they can contribute to avoiding the most dangerous effects of autocratization, especially (but not only) if this is combined with resistance from political, social, and external actors. Second, we find evidence for those studies emphasizing the importance of political resistance. Coalition-making and electoral politics, e.g., a cordon sanitaire against the incumbent, legislative actions by the parliament, or elite defections, play a role as a sufficient factor in two out of four resistance patterns (expectation 2), if combined with institutional, nonviolent resistance, and alone, in the absence of violent protests (‘Politics strikes back’).

Third, related to social resistance, we find a positive impact of nonviolent protests (expectation 3). However, nonviolent protests always act in conjunction with other political or institutional actions, and they can also be absent in cases of successful resistance. Therefore, even though we are inclined to confirm their sufficient role in averting breakdown, we observe that their impact is somewhat weaker. Consequently, we have evidence of the detrimental impact of violent protests on autocratization. Even though of great symbolic impact, their absence is among the sufficient conditions related to two out of four patterns of democratic survival (expectation 4). Fourth, our analysis shows that the influence of external actions matters, but only when this pressure supports internal actors (expectation 5). Nonetheless, the absence of international resistance might be part of two sufficient patterns of democratic survival – a finding that reinforces previous mixed accounts. Fifth, our results point to the conclusion that what really matters for democratic survival is the occurrence of democratic resistance actions across a combination of different arenas (expectation 6 – ‘The rebel alliance: Cross-arena coalitions’). Overall, this finding suggests that, while there is no one-size-fits-all explanation for democratic survival during autocratization, resistance stemming from the collective efforts of various actors across different dimensions (institutional, political, social, and external) is sufficient to ensure democratic survival when democracy starts to deteriorate. This pattern relates to two possible configurations, as underlined in the baseline sufficiency analysis.

Nevertheless, a broader perspective on these findings serves as a significant caveat in their interpretation. First, following our examinations of various clusters’ diagnostics, we confirmed previous evidence that the success of democratic resistance is inevitably linked to the same factors that help democratic consolidation, such as high or medium-high wealth levels or already consolidated liberal-democratic institutions. While integrating both structural factors of democratic resilience and agency-based factors of democratic resistance is key to enhancing autocratization research, democratic resistance literature in particular should more consistently examine cases outside the regions of (West and East) Europe and (North and South) America to become really global in its scope. Second, still, alternative case selections have demonstrated that, even though changing, enlarging, or reducing the sample of cases included in the analysis, it is the unity (in diversity) that really makes the strength of the two patterns in the first configuration. ‘The rebel alliance’ is, in conclusion, the most robust and generalizable configuration, which can explain the success of democratic survival in very diverse autocratization episodes, where the strategic co-operation of institutional, political, social, and external actors prevented the would-be authoritarian elites from subverting democracy.

There is substantial room for improvement in our research, particularly regarding more precise measurements of democratic resistance. In fact, the DEED is based on a combination of factual and expert data retrieved from press releases. This can limit the precision of the measurement in cases with limited knowledge or less media coverage (Weidmann Reference Weidmann2016; Dawkins Reference Dawkins2021). Combining this source with web-scraped data would be a valuable addition to our work. Similarly, to avoid measurement errors, it is fundamental to retrieve more recent data (post-2019) on party cohesion integrating the V-Party, as well as to corroborate the V-Dem-based understanding of autocratization episodes with other democracy data. Beyond such measurement issues, another possible improvement to our work would be to combine the QCA tools implemented here with large-N statistical event data analysis and within-case studies. This would enable more thorough examinations of the generalizable and observable implications of such patterns of democratic survival in order to join different levels of explanation and incorporate factors related to autocratization onset and end.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1475676525100595.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the editors of EJPR and the anonymous reviewers for their supporting and guiding insights. We are also grateful to individual colleagues who provided extensive feedback on the manuscript, such as Daniel Bochsler, Seraphine F. Maerz, Jean-Benoit Pilet, Svend-Erik Skaaning, and Lasse Egendal Leipziger. We also thank Steven Levitsky, Theresa Gessler, and Agnieszka Kwiatkowska as discussants of our paper, respectively, in the 2023 APSA panel ‘Investigating Episodes of Autocratization’ in Los Angeles, the 2023 ECPR panel ‘Opposition Strategies Amid Democratic Backsliding: A Cross-Regional Perspective’ in Prague, and the 2023 SISP panel ‘Rethinking Regimes and Regime Change’ in Genoa, as well as others in the audience who have shared ideas and suggestions.

Funding statement

The authors received no specific grant from any public or private funding agency for this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.