Although many mental illnesses are linked to increased mortality, with the exception of dementia, few are fatal in their own right. Reference Pizzol, Trott, Butler, Barnett, Ford and Neufeld1 Deaths of individuals receiving mental health care have attracted significant public, media and government attention in the UK. 2 This has prompted multiple independent inquiries, some of which are ongoing, into service provision and safety. 3 These investigations are tasked with revealing important lessons, such as failures in providing safe and therapeutic in-patient care, shortcomings in staff practices and weaknesses in organisational governance, but are often centred on single institutions. Reference Walshe and Offen4,5

Prevention of Future Death reports

In England and Wales, an important source of insight into preventable deaths is coroners’ statutory duty to issue Prevention of Future Death reports (PFDRs, also known as Regulation 28 reports). These are issued when coroners believe that specific actions should be taken to prevent further similar deaths. The statutory duty and procedural details for coroners to issue a report are established under the Coroners and Justice Act 2009 and the Coroners (Investigations) Regulations 2013. 6,7 A revised Chief Coroner’s Guidance No. 5, issued on 16 July 2013, further introduced a standardised reporting template and set out a publication on the judiciary website. 8 However, while the Chief Coroner tries to publish as many PFDRs as possible, some may not be published if they are believed to be unnecessary. As of 1 June 2025, a total of 5707 PFDRs were available online, with the earliest published on 30 July 2013.

Each report contains carefully considered information, normally including the report type (e.g. mental health-related death, child death, railway-related death), the date of report, details of the deceased, the coroner’s name and affiliated area, the intended recipients (one or more), the circumstances of the death, the coroner’s concerns and the recommended actions, making them a publicly accessible and unique source for identifying issues across different domains. 9 PFDRs have been used in various healthcare contexts, including hospital care, care home and community settings, highlighting recurrent themes such as organisational process, access to services, insufficient staff training and inter-agency communication. Reference Leary, Bushe, Oldman, Lawler and Punshon10–Reference Wallace, Revie, Schneider, Mais and Sharland12

Study objectives

Despite their potential, little has been published analysing PFDRs relating to mental health. To address this gap, this study aims to provide a comprehensive view of those PFDRs concerning mental health in England and Wales, with the following specific objectives:

-

(a) to describe the overall profile of these reports, including their temporal and geographical distribution, the demographic characteristics of the deceased and the extent to which recipient responses are publicly available;

-

(b) to examine the relational patterns emerging from these reports, including the categories of deaths most frequently reported alongside mental health-related deaths, the recipients most often addressed and the relationships among these recipients;

-

(c) to identify the key concerns and preventive actions highlighted by coroners, and how these have evolved over time.

Method

Study design

This study was a retrospective analysis of all publicly available PFDRs related to mental health deaths in England and Wales up to 1 June 2025. The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation, and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 as revised in 2013. All procedures involving human subjects/patients were approved by the Human Biology Research Ethics Committee of the University of Cambridge (no. HBREC.2025.22). The study design is summarised in Supplementary Fig. 1 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2025.10528.

Data acquisition and preprocessing

A Python script was used for automatic collection of publicly available reports categorised as ‘mental health-related deaths’ according to the official classification system on the UK Courts and Tribunals Judiciary website (N = 584). All files were downloaded in portable document format. For scanned documents without embedded text, optical character recognition was then applied within the Python workflow to convert page images to machine-readable text for further analysis. During manual checking, we identified two reports that each described two deceased individuals; these were then split into separate case records, resulting in a final data-set of 586 cases.

Field extraction and quality assurance

For each report, structured variables – including the original uniform resource locator (URL), report date, reference identifier (Ref), coroner’s name and area, category and recipients of the report – were extracted from the hypertext mark-up language page structure. Contextual variables were extracted from the texts using the large language model (LLM; GPT-4o, OpenAI, 2024; San Francisco, California, USA; https://platform.openai.com/docs/models/gpt-4o). These included the deceased’s age and gender, death setting (during hospital admission or outwith the hospital), specific concerns raised by the coroner, recommended actions, response deadline and response availability mentioned in the narrative. The description of included variables is detailed in Supplementary Table 1.

Manual review was used to calibrate and refine the LLM prompts, to maximise the accuracy of automated extraction; specifically, this calibration was performed iteratively. In each round, a 10% random sample (n = 50) of reports was manually checked against the original text to identify extraction errors. The prompt was refined after each round until all extracted variables in the validation sample were accurate, at which point the prompt was finalised. The initial and final prompts used for data extraction are provided in Supplementary Table 2. The LLM outputs of coroner’s concerns and actions were subsequently reviewed by the researcher to identify recurring concepts and candidate themes, serving as an initial aid to theme generation. Final themes were coded manually through iterative review and discussion to ensure conceptual consistency. A detailed coding framework for concerns and actions, including thematic descriptions and the corresponding examples, is provided in Supplementary Table 3. Finally, a human quality assurance was undertaken by a single researcher to further ensure data integrity, and the human-adjusted data-set was used for analysis.

Statistical analyses

We conducted three analytic modules corresponding to our core research aims. We performed a series of descriptive analyses to address our first aim. Temporal trends were examined by summarising annual and monthly counts of reports. Spatial distributions were then assessed by plotting annual counts across the top 20 coroner areas and 9 English regions. Demographic characteristics of the deceased were described by distributions of age, gender, death setting and further categorisation of deaths occurring outwith hospital. Response availability was determined by whether the report included one or more attached response files from recipients.

For our second aim we constructed co-occurrence networks, a method commonly used to visualise how items tend to appear together in a data-set, to explore patterns of co-occurrence in the reports. Reference Newman13 Specifically, we analysed how deaths classified as mental health may overlap with other death categories, and how different recipients were jointly addressed in the same report. In these networks, the size of each node represents the frequency with which a category or recipients appeared, while the thickness of the edges indicates how often two nodes co-occurred in the same report. To identify broader structures, we applied community detection algorithms that group nodes into clusters based on how strongly they are connected. Reference Girvan and Newman14 In our context, the resulting clusters highlight sets of categories and recipients that consistently appear together across multiple reports.

Finally, to address our third aim, we used thematic analysis to visualise the evolution of concerns from 2013 to 2025. We divided the period into three phases (2013–2018, 2019–2022 and 2023–2025) based on the volume of reports issued. Within each period, coroners’ concerns were mapped to a set of themes and the frequency of each theme was calculated to determine its proportional representation. Topic similarity between themes was assessed using term frequency–inverse document frequency vectorisation with cosine similarity. Each vertical column represents the distribution of concern themes, with block height proportional to frequency. Flow between columns represents thematic similarity and continuity across periods. We then constructed networks linking each concern to the recommended actions that appeared in the same report, thereby mapping systemic linkages between coroners’ observations and their proposed interventions. Node size was weighted by how frequently a concern or action was mentioned in the reports, and edge thickness was determined by how often they appeared together. All analyses were conducted using Python (version 3.9.13 for macOS; Python Software Foundation, Wilmington, Delaware, USA; https://www.python.org/) in Jupyter Notebook (version 6.4.12 for macOS; Project Jupyter; https://jupyter.org/).

Results

Descriptive statistics

Spatiotemporal distribution

A total of 568 reports were identified between August 2013 and June 2025. Figure 1(a) shows the annual trend in the total number of PFDRs, the number of mental health-related PFDRs and their proportion relative to all PFDRs between August 2013 and June 2025. Overall, the total number of PFDRs fluctuated over time, with notable peaks in 2014 (N = 601) and again in 2019 (N = 585), as well as in 2024 (N = 706). The number of mental health-related PFDRs also increased over the decade, increasing steadily from 9 in 2013 to a peak of 127 in 2021, before declining to 40 in the first half of 2025. The proportion of mental health-related reports relative to all reports rose sharply during the COVID-19 pandemic period (approximately late 2019 to 2022), reaching its highest level in 2021 (26.68%).

Fig. 1 Temporal and geographic patterns of reports from 2013 to 2025. (a) Annual trend in the total number of PFDRs, mental health-related PFDRs (bar) and their proportions (line). (b) Annual PFDR counts in the top 20 coroner areas. (c) Annual PFDR counts by region. (d) Cumulative geographic distribution of PFDRs by region. PFDRs, Prevention of Future Death reports.

Figure 1(b) displays annual counts within the top 20 coroner areas, showing that some local jurisdictions, such as Manchester South, East Sussex and East London, consistently reported higher numbers across the study period. Figure 1(c) aggregates data by official regions, indicating that North West (103), South East (95), London (76) and West Midlands (59) collectively accounted for the largest share of reports. The cumulative geographic distribution in Fig. 1(d) further underscores regional disparities in these mental health reports.

Demographic and contextual characteristics

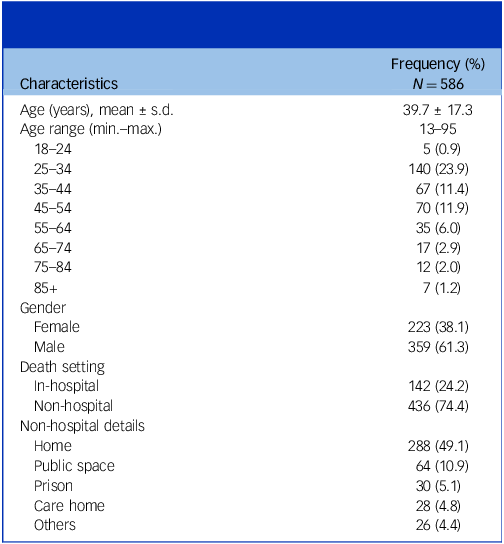

Table 1 summarises the demographic and contextual profiles of individuals recorded in the reports. The mean age was 39.7 years (s.d. 17.3). The largest proportion of cases fell within the 25- to 34-year age group (n = 140, 23.9%), followed by those aged 45–54 years (n = 70, 11.9%) and 35–44 years (n = 67, 11.4%), with a smaller representation in younger adults aged 18–24 years (n = 5, 0.9%) and adults aged 85+ years (n = 7, 1.2%). Most individuals were identified as male (n = 359, 61.3%), with 38.1% as female.

Table 1 Demographic and contextual profiles of individuals recorded in the reports

Regarding death setting, the majority were classified as non-hospital at the time of death (n = 436, 74.4%), while 24.2% were in-hospital (n = 142). Among those outwith hospital care, deaths occurred most frequently at home (n = 288, 49.1%), followed by public spaces such as train stations, parks or rivers (n = 64, 10.9%), prisons (n = 30, 5.1%) and care homes (n = 28, 4.8%).

Overall, these findings suggest that those mental health-related deaths under coroners’ review and which prompted a PFDR often involved relatively young men who were outwith hospital settings at the time of death.

Response availability

Under the current statutory framework, recipients of a PFDR are generally under a duty to provide a response within 56 days of the date of the report. 15 Among the 586 reports, 78.0% (n = 457) included at least one attachment containing a formal written response from recipients. Most responses included structured, concern-by-concern replies, often accompanied by proposed and planned improvement, although a significant minority used a free-text response. Some responses indicated clear change while others described a commitment to improving or making change in the future. However, the remaining 129 reports (22.0%) had no corresponding response files available. Among these reports, 125 had already passed their response deadlines at the time of data collection (29 June 2025).

Co-occurrence networks

A single PFDR may relate to more than one death type. Instead, a report can be assigned to multiple categories simultaneously. As shown in Fig 2(a), mental health-related deaths often co-occurred with systemic issues such as Suicide, Hospital Death, Alcohol, Drug and Medication as well as Community Health Care and Emergency Services. Community detection further revealed two major clusters. The first cluster (red nodes (dark blue in print)) linked Mental Health, Suicide, Hospital Death and deaths occurring in institutional settings such as State Custody or Care Homes. The second cluster (blue nodes (light blue in print)) predominantly involved deaths related to acute external factors, including Alcohol, Drug and Medication, Police and Emergency Services. These distinct groupings indicate differing patterns of systemic concerns identified across cases.

Fig. 2 Co-occurrence patterns of death categories and recipients. Node size and edge thickness are proportional to their frequencies of occurrence and co-occurrence, respectively. (a) Co-occurrence networks of categories within reports. (b) Co-occurrence networks of recipients. NHS, National Health Service; HM, His Majesty.

A PFDR is often sent to more than one organisation, reflecting the shared responsibility of multiple bodies in providing services. Figure 2(b) depicts the organisational co-occurrence network. The larger nodes represent organisations that were most frequently addressed in PFDRs. As shown in Fig. 2(b), the Department of Health and Social Care, National Health Service (NHS) England, Ministry of Justice, the Care Quality Commission (CQC) and the Royal College of Psychiatrists appeared most frequently as recipients. Community detection further identified three primary clusters that point to different governance nexuses. Cluster 1 (red nodes (dark blue in print)) was centred on the Department of Health and Social Care, and comprised a mix of criminal justice entities (HM Prison and Probation Service, Ministry of Justice, Home Office, Greater Manchester Police, Metropolitan Police), national and regional health governance bodies (Greater Manchester Health and Social Care Partnership, Norfolk and Suffolk NHS Foundation Trust) and an education authority (Department for Education). Cluster 2 (blue nodes (light blue in print)) was centred on NHS England, which co-occurred with a combination of regional NHS trusts (Birmingham and Solihull Mental Health NHS Trust, NHS Dorset), local government actors (Birmingham City Council, Birmingham Clinical Commissioning Group), police coordination agencies (National Police Chiefs’ Council, West Midlands Police) and a key professional organisation (Royal College of Psychiatrists). Cluster 3 (purple nodes (grey in print)) consisted of three highly connected nodes: the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, CQC and the Greater Manchester Mental Health NHS Foundation Trust.

Thematic analysis

Evolution of concerns over time

To examine how the focus of concerns in PFDRs changed over time, we constructed a thematic river chart to visualise the major concern themes from 2013 to 2025.

Period 1: 2013–2018

As shown in Fig. 3(a), prior to 2019, coroners primarily highlighted fundamental issues, particularly those related to Resource Allocation and Accessibility, including concerns about insufficient ambulance availability; high demands on emergency services; inadequate treatment pathways for individuals with co-occurring severe mental illness and substance misuse; and underfunding of mental health services leading to staff workloads and care delivery delays. A 2017 case from Nottinghamshire reported the death of a woman who had waited more than 5 months to access early intervention in psychosis services. The coroner concluded that lack of funding was the central issue contributing to closed or delayed referrals. Similarly, a PFDR concerning the death of a man with severe depressive illness in London highlighted that underfunding and insufficient qualified personnel within community mental health services had hindered continuity of care and led to missed opportunities for intervention.

Fig. 3 Evolution of concerns and actions. (a) Evolution of concerns. The size of each block represents the relative frequencies of themes; the most common theme for reports is shown as the lowest block at each time point; flows between periods represent thematic similarity and continuity. (b) Mapping of concerns to recommended actions. Node size and edge thickness are proportional to their frequencies of occurrence and co-occurrence, respectively.

Period 2: 2019–2022

During the COVID-19 pandemic period, themes became more diversified. New focus emerged around Policy and Protocol Compliance, Inter-agency Coordination and Integration and Communication and Documentation Consistency. Challenges around information-sharing and policy consistency became increasingly evident during this period. Reported concerns during this period included unclear protocols for multi-agency coordination, the absence of national guidance on transfers between care settings and inconsistencies in documentation or handover procedures. For example, in a 2020 PFDR from Lancashire & Blackburn with Darwen, the coroner reported a case with personality disorder who absconded while on compulsory detention and later died by drowning. The investigation revealed that documentation was incomplete, the absent-without-leave procedure was not followed, no handover had been undertaken between security workers and there had been no training on policy and procedure. In 2021, the PFDR described the death of a young woman admitted for treatment. Although her previous records had been sent by another NHS Trust, only part of the documentation was read and forwarded to the staff. The coroner concluded that failures in record-sharing and cross-organisational transfer had contributed to her death.

Period 3: 2023–2025

Since 2022, Risk Assessment and Management has remained one of the most frequently reported concerns, becoming a long-standing challenge. Together with issues related to Resource Allocation and Accessibility and Inter-agency Coordination and Integration, it became the core area of concern. In one case from South London, a middle-aged man repeatedly left the emergency department before his death. The coroner identified multiple risk assessment failures, including the lack of alerts about his high-risk behaviour, failure to carry out escalating risk assessments, and the absence of appropriate accurate monitoring. Another case involved a death from unintended consequences of necessary medical treatment. The coroner pointed out that the staff had failed to recognise the drugs’ side-effects and did not initiate timely face-to-face assessment, which amounted to neglect.

Mapping concerns to actions

As shown on the right side of Fig. 3(b), coroners recommended a wide range of preventive actions. Overall, each concern was often linked to more than one action, which indicates that these issues were complex and required multiple interventions. However, most concerns converged on a limited set of action nodes, such as Policy and Protocols, Monitoring and Review and Communication and Coordination, suggesting that, despite the diversity of concerns, the recommendations were most frequently focused on institutional and policy reforms. In many cases, the coroner recommended reviewing the process of conducting and recording enhanced observations for detained patients, together with the introduction of training and written guidance to ensure consistent practice across staff. Moreover, urgent reviewing of the discharge process and dual-diagnosis policies, as well as the development and implementation of clear protocols, were also highly recommended.

In addition, some concerns, such as Training and Staff Competency and Discharge and Follow-up Process, showed a more focused linkage, reflecting a more limited improvement strategy.

Discussion

Principal findings

This study provides a comprehensive examination of mental health-related PFDRs across England and Wales. Drawing on 586 reports, we captured a wide range of variables including demographic details of the deceased, coroner areas, response availability, addressed organisations, interconnected death categories, specific concerns raised and the recommended actions.

We observed a steady increase in mental health-related reports from 2013, peaking in 2021 and followed by a subsequent decline. During the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, strict social restrictions disrupted coronial practice with many activities altered or suspended, leading to delays in death reporting. A recovery phase followed and, since July 2021, coroners’ courts have operated more normally to address case backlogs. Reference Teague16 At the same time, the Coronavirus Act 2020 temporarily relaxed requirements for death certification, permitting doctors to complete the Medical Certificate of Cause of Death (MCCD) without having seen the deceased in the previous 28 days, and allowing MCCDs to be submitted electronically, thereby streamlining the process. 17 These provisions expired in March 2022, which may partly explain the change in numbers of PFDRs. In addition to these procedural factors, increases in mental health-related PFDRs during the pandemic period may also reflect a true rise in mental health crises. Evidence has shown that the pandemic was associated with rising rates of mental health problems, higher levels of psychological disorders, including depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress, and increased suicide rates. Reference Czeisler18,Reference Simon, Saxe and Marmar19 Delays in help-seeking and disruptions to mental health services may therefore have contributed to a higher number of PFDRs during this period. Reference Yonemoto and Kawashima20,21

Geographically there was an evident regional difference, with certain coroner areas such as Manchester South, East Sussex and East London consistently recording higher case counts. This difference may reflect variation in either the epidemiology of mental illness or local service provision, or indicate differing willingness among coroners in issuing PFDRs. The decision to issue such reports is made when a coroner believes that action should be taken to prevent future deaths, and only a small proportion of inquests results in a PFDR being issued. 22 This lack of consistency could limit comparability across regions and weaken the potential of PFDRs as a mechanism for nationwide learning. Addressing such variability could involve enhanced training and clear guidance for coroners, or the establishment of more systematic feedback mechanisms and review processes to ensure greater consistency. However, such regional variation may also be influenced by differences in overall publication rather than by true disparities in mental health-related deaths. Supplementary analyses (Supplementary Figs 2 and 3) showed that some areas, such as Manchester South and Inner North London, consistently published more reports across all categories. These results align with previous studies and suggest that coronial activity and reporting capacity may have contributed to these differences. Reference Zhang and Richards23

Younger and middle-aged groups were disproportionately represented in PFDRs (particularly those aged 25–34 and 45–54 years). This pattern of relatively young age is consistent with previous analyses of PFDRs related to suicides, which also reported a comparatively young median age (42 years). Reference Anthony, Aronson, Brittain, Heneghan and Richards24 In our study, males accounted for the majority of cases (61.3%), which is consistent with existing evidence showing that men are more likely to be involved in suicide and substance-related deaths. 25,26 Interrelated factors provide possible explanations for why men are disproportionately represented in mental health-related death PFDRs. Men are more likely to die by suicide and use violent methods, such as hanging, which contribute to higher likelihood of death and possibly coronial action. They may also act more impulsively on suicidal thoughts and are less likely to display warning signs, such as discussing suicidal thoughts, that may be more likely to prompt coronial investigation. Reference Tsirigotis, Gruszczynski and Tsirigotis27–Reference Chapple and Johnson29

Consistent with previous research, most mental health-related deaths triggering a PFDR occurred outwith the hospital setting, such as home, in public spaces or in custodial environments. However, nearly a quarter (24.2%) occurred in hospital settings. These cases broadly fell into three common scenarios: deaths associated with clinical procedures or hospital medical management; suicide during admission; and deaths of individuals admitted in a severely deteriorated physical condition and who died shortly after admission. However, given that in-hospital settings provide only a very small minority of total psychiatric care, deaths in hospital are probably significantly over-represented. 30 This may reflect the fact that in-hospital deaths often involve a clearly identifiable responsible entity, supported by detailed clinical records and formal incident investigations, and that some events, particularly in-hospital suicides, are viewed as more preventable and more likely to require systemic action. More importantly, deaths of patients detained under the Mental Health Act 1983 are subject to mandatory reporting and an inquest under the Coroners and Justice Act 2009, which may further increase the visibility of such cases to coroners and heighten the likelihood of a PFDR being issued. 6,31

Notably, only 78.0% of PFDRs in our data-set contained a response from recipients, leaving 22.0% without accessible evidence of follow-up. This aligns with recent developments in practice, where the Chief Coroner published a list of non-responders to strengthen transparency and accountability. 32 Whether responses have been received but are not available, or are being prepared, is not known, but it seems likely that at least some PFDRs have not received a response. This should be explored further to understand the reasons involved. We found it difficult to analyse the available responses because there is variation in the way they are provided, and some are hard to interpret. We suggest the way in which PFDRs should be written to increase the likelihood of hard outcomes, and a standard way of responding. More consideration should be given to exploring the effectiveness of actions in response to concerns in addressing the risk of future events. This would help increase the quality of both PFDRs and actions taken in response.

The co-occurrence analysis showed that mental health-related deaths seldom stem from isolated issues in care delivery. The networks highlighted that PFDRs often include interconnected systemic issues and span multiple sectors, implicating not only healthcare services but also criminal justice agencies, local authorities, professional bodies and educational institutions. This complexity aligns with the multifactorial aetiology and diverse treatment needs associated with mental disorders. By contrast, recent prosecutions of individuals involved in deaths may represent a more reductionist approach, focusing on singular accountability rather than trying to understand the complex interplay that contributes to many of these deaths. Reference Sangiorgi, Vink, Farr, Mulvale and Warwick33,Reference Lamberti34

Thematic analyses revealed that coroners’ concerns have changed over the past decade, from early focus on resource allocation and service accessibility to greater attention on inter-agency collaboration and communication during the COVID-19 period (approximately from late 2019 to 2022) and, more recently, to issues of risk assessment and management. These changes may reflect both evolving service priorities and external pressures, such as the operational disruptions caused by the pandemic and the increasing policy emphasis on proactive patient safety measures. 35–37 Additionally, the growing recommendations relating to monitoring and review, as well as changes to policy and protocols, suggests a shift towards systemic governance approaches, consistent with the complex, multi-sectoral nature of many mental health-related deaths. 38

Implications

Our work demonstrates the feasibility of using LLMs for the systematic extraction of structure context-dependent information from heterogeneous data at scale. Whereas previous PFDR studies have often been limited to small samples or traditional text-mining, Reference Zhang and Richards23 our approach combined LLM-based parsing with targeted manual validation to achieve both scalability and accuracy. This approach offers a transferable framework for the large-scale analysis of other complex, unstructured records in healthcare, legal and regulatory contexts, supporting more policy development.

Practically, the findings highlight the value of conducting regular analyses of PFDRs on a national scale to identify emerging risks that can inform positive change. Our results also reinforce the view that mental health-related deaths rarely arise from isolated errors within a single service. The cross-sectoral nature of coroners’ concerns underscores the importance of coordinated, multi-agency solutions rather than isolated institutional responses. Therefore, there may be value in considering systemic modifications to strengthen national learning. A central body, such as the Department of Health and Social Care, could be tasked with proactively reviewing PFDR trends and sending feedback across the system.

Limitations and future study

Although we are able here to describe a comprehensive analysis of mental health-related PFDRs issued in England and Wales, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the analysis was restricted to 586 publicly available PFDRs published between August 2013 and June 2025. This number is considerably lower than the actual number of deaths related to mental health across England and Wales, meaning that these cases represent only a subset of all relevant deaths during this period. In addition, our analysis was based on reports classified as ‘mental health-related deaths’ within the official category system of the Judiciary website. Although this classification has improved over time, mortality data in mental health are complex and are known to suffer from systemic inconsistencies and variability in how deaths are defined, classified and reported across organisations. Reference Aldridge, Humphrys and Corlett39,Reference Gibbons40 For example, variations in the time frame for classifying deaths, differences in reporting frameworks and the absence of national standards make collected data difficult to compare. These structural issues may affect how deaths are categorised, and thus some relevant cases might not have been included in our data-set.

Second, we acknowledge that manual checking of the extracted data and thematic coding process was conducted by a single researcher, which may have introduced minor subjectivity or human error. Although multiple rounds of checking and verification were performed to minimise potential bias, this process could be strengthened in the future by employing independent double coding and inter-rater reliability testing.

Third, although our analyses identified the spatiotemporal patterns, we were unable to fully explain factors resulting in these changes: for instance, whether changes in legislation, resource allocation or procedural management during the COVID-19 pandemic could have affected the frequency, content and scope of PFDRs. Understanding these contextual factors would allow for a clearer interpretation of the observed trends. Future research could adopt mixed-method designs to examine these relationships.

Finally, to our knowledge, while this study represents the largest and most systematic analysis of mental health-related PFDRs to date, a major gap concerns the post-issuance trajectory of PFDRs. Although many reports received responses from recipients, the format and level of detailed varied differently. Some organisations provided structured and detailed replies to each concern, while others submitted more free-form statements. This heterogeneity makes it difficult to systematically assess whether these concerns and recommendations were acted upon, and what measurable impact they had on preventing future deaths. Further development of the PFDR system could benefit from more standardised response formats and clear mechanisms for follow-up. Research that combines PFDR data with other service evaluations, or stakeholder interviews, would be essential to assess the real-world effectiveness of these recommendations.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2025.10528

Data availability

The data, analytic codes and research materials that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author (B.R.U.).

Acknowledgement

The author(s) made use of ChatGPT to assist with drafting of this article. ChatGPT-4o was accessed from the OpenAI platform and used with modification on 22 July, 19 August and 4 September 2025.

Author contributions

H.Q.: conceptualisation, formal analysis, methodology, validation, visualisation, writing – original draft; J.J.: investigation, methodology, validation, visualisation, writing – review and editing; M.B.: investigation, methodology, writing – review and editing; R.B.: investigation, methodology, writing – review and editing; M.S.: investigation, methodology, writing – review and editing; C.I.: investigation, methodology, writing – review and editing; B.R.U.: conceptualisation, investigation, methodology, supervision, resources, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre (no. NIHR203312). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. B.R.U.’s post is part-funded by a generous donation from Gnodde Goldman Sachs Gives.

Declaration of interest

B.R.U. is vice-chair of the Faculty of Old Age Psychiatry at the Royal College of Psychiatrists. He is on the editorial board of BJPsych but had no part in reviewing this paper. He is research and development director at his trust, and dementia and neurodegeneration lead for NIHR Research Delivery Network Eastern. His post is part-funded by a generous donation from Gnodde Goldman Sachs Gives. He has served on paid advisory boards for Lilly and TauRx. We also confirm that M.B. is a member of the editorial board of BJPsych but was not involved in the review or editorial decision-making for this manuscript. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Transparency declaration

H.Q. and B.R.U. affirm that the manuscript is an honest, accurate and transparent account of the study being reported. No important aspects of the study have been omitted.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.