Introduction

Palaeolithic art offers a unique window into understanding prehistoric societies. Thus, the iconography, techniques and stylistic features of the Upper Palaeolithic form the basis of research and are potentially valuable sources of information about cultural and knowledge exchange networks (Garate et al. Reference Garate, Rivero and Rios-Garaizar2023); Jaubert & Barbaza Reference Jaubert and Barbaza2005; Petrognani & Robert Reference Petrognani and Robert2019; Sauvet Reference Sauvet and Clottes1990; Sauvet & Rivero Reference Sauvet and Rivero2016; Sauvet et al. Reference Sauvet, Fortea, Fritz and Tosello2008; Utrilla & Martínez-Bea Reference Utrilla and Martínez-Bea2008; Villaverde Reference Villaverde, Bueno-Ramírez and Bahn2015).

Hand stencils occupy a singular position within the corpus of Palaeolithic cave art due to their dual nature as both biological traces and symbolic images (Fernández Navarro & Garate Reference Fernández-Navarro, Garate, Bea, Domingo, Mazo, Montes and Rodanés2021). Unlike figurative representations of animals or abstract signs, stencils are direct bodily impressions, created by placing a human hand against the wall and applying pigment. As such, they are both fossil evidence of the physical presence of individuals and deliberate graphic expressions. This dual identity grants them exceptional potential: on the one hand, they offer biometric and morphological data that can inform us about the age, sex and lateralization of their makers; on the other, they function as symbolic acts that reflect cognitive, social or ritual dimensions of Upper Palaeolithic communities. Despite their limited geographic and numerical distribution, this capacity to bridge biological and cultural domains makes hand stencils one of the most revealing and significant elements of early symbolic behaviour.

However, despite their relevance as a link to prehistoric communities and their universal significance in rock art over thousands of years in different cultures, there is no study that offers a comprehensive evaluation of this phenomenon in European Upper Palaeolithic art. Furthermore, the historical absence in Europe of a systematic catalogue that compiles and classifies hand representations in different caves has hindered a global understanding of their distribution and characterization. In fact, we have only one inventory of hands (Fernández-Navarro & Garate Maidagan Reference Fernández-Navarro and Garate Maidagan2023) dedicated to cataloguing and characterizing hands at the European level and another focused solely on the Spanish case (Collado Giraldo Reference Collado Giraldo2018).

Background

The history of the discovery of hand representations in Palaeolithic art dates back to the first expedition to the Altamira cave (Spain) in October 1902, conducted by É. Cartailhac and H. Breuil, although its famous polychrome ceiling was discovered in 1879. Breuil and Cartailhac published a detailed study comparing the hand representations of Altamira with Australian and American rock art (Cartailhac & Breuil Reference Cartailhac and Breuil1905). This work was immediately expanded with an even more extensive comparison, highlighting the stylistic and thematic connection with Aboriginal Australian and American art (Cartailhac & Breuil Reference Cartailhac and Breuil1906).

The discovery of hand representations in the Castillo cave in 1903 by H. Alcalde del Río, and the subsequent study of the 44 recorded in 1911, continued to increase the corpus of Palaeolithic art and emphasized the importance of an anthropometric study of these figures (Alcalde del Río Reference Alcalde del Río1906). In 1906, F. Regnault discovered the hands in the Gargas cave (France), revealing the largest number of hand stencils with missing fingers, a finding that immediately sparked debates about their meaning (Cartailhac & Breuil Reference Cartailhac and Breuil1906; Régnault Reference Régnault1906).

Throughout the twentieth century, the discoveries of caves with hand representations multiplied. New cavities were discovered, such as the Maltravieso cave (Spain) in 1956, which revealed a large number of hands with missing little fingers in most of them (Ripoll López et al. Reference Ripoll López, Ripoll Perelló, Collado Giraldo, Mas Cornélla, Jordá Pardo and de Estudios Paleolíticos1999), or the Chauvet cave in 1994, with 11 negative and positive handprints in red pigment (Clottes Reference Clottes2001). In 1995, the La Garma cave (Spain) was added to the list, standing out for its unusual use of yellow pigment (Arias & Ontañón Reference Arias, Ontañón and Ontañón2008).

Currently, discoveries continue to expand into less explored areas, with recent findings in the south of the Iberian peninsula (Collado Giraldo et al. Reference Collado Giraldo, Bea and Ramos Muñoz2019; Salvador Fernández-Sánchez et al. Reference Salvador Fernández-Sánchez, Collado Giraldo and Vijande Vila2021; Simón-Vallejo et al. Reference Simón-Vallejo, Cortés-Sánchez and Finlayson2018). In this context, new technologies have allowed the detection of hand representations in previously known cavities and new regions, expanding the map of Palaeolithic art and enriching our understanding of this form of artistic expression.

Catalogue and geographical distribution

It is difficult to know the complete corpus of Upper Palaeolithic hand stencils due to several inherent challenges. The available information is widely dispersed, and in many cases, it is of ancient origin, which has contributed to a lack of comprehensive graphic documentation. Many of these existing records lack detailed descriptive information and a current review with new systems and tools that facilitate the visualization and documentation of rock-art motifs. Additionally, their interpretations regarding dating and significance are uncertain, complicating the task of consolidating precise and updated knowledge about these representations.

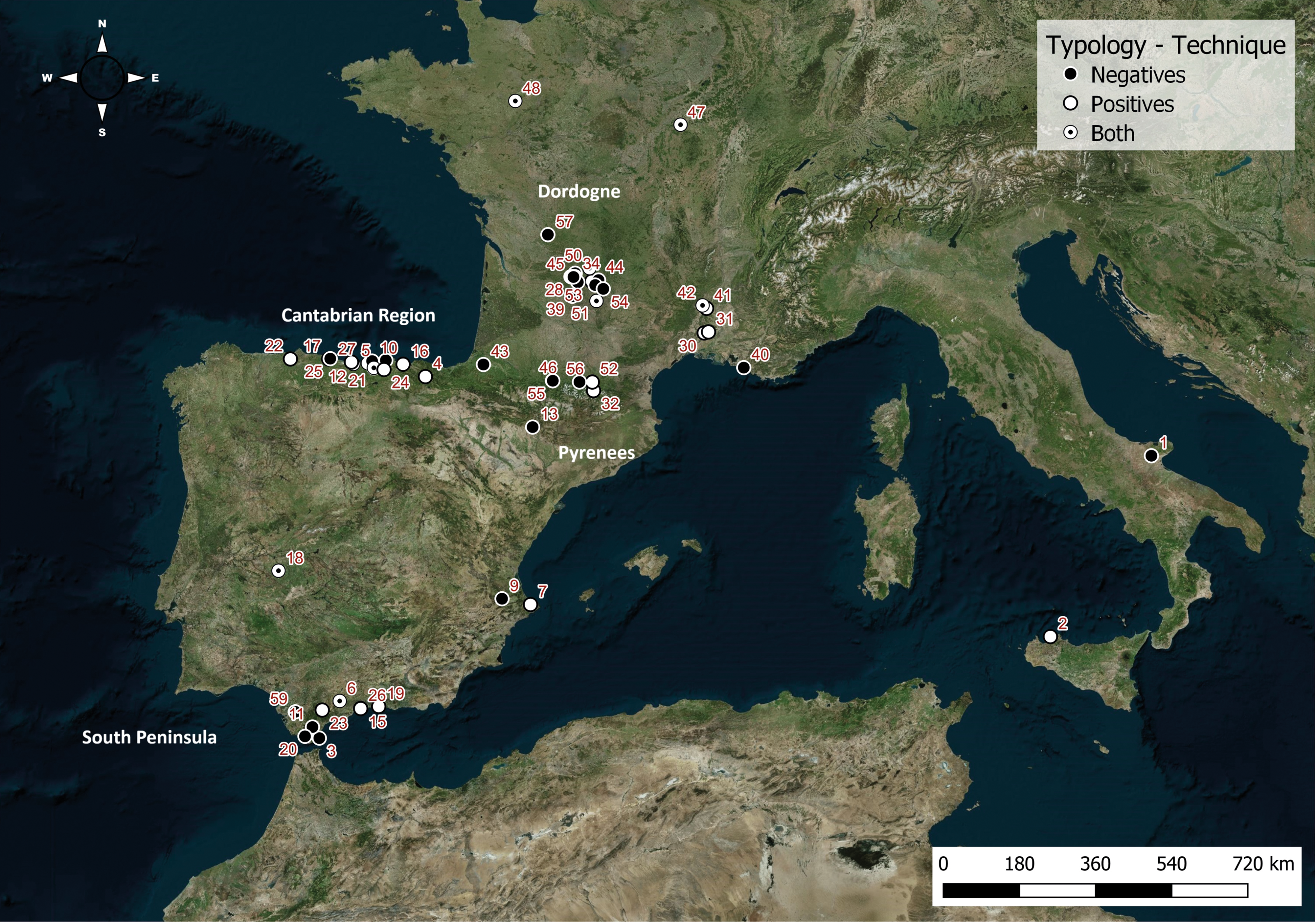

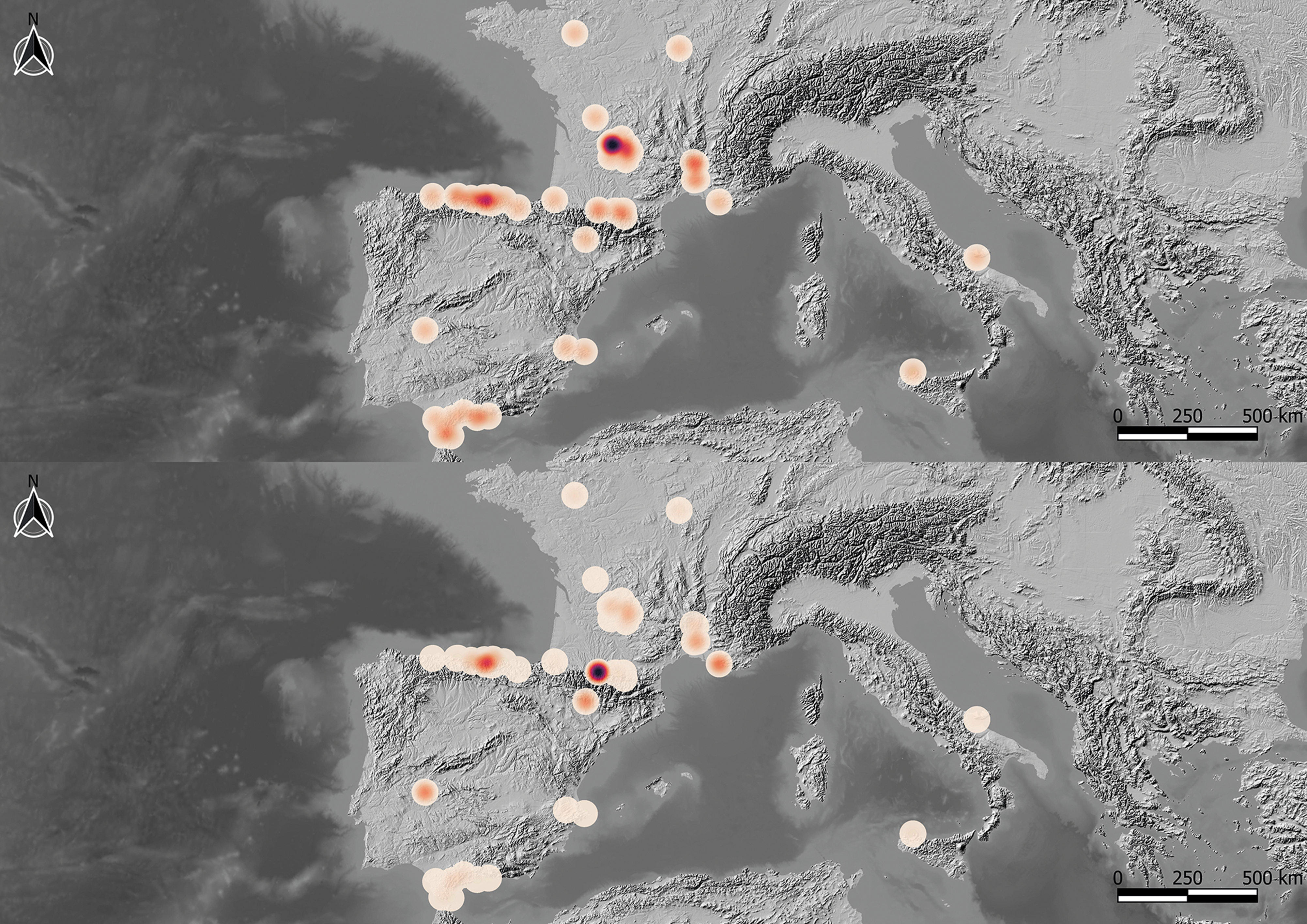

After intensive study of the data published to date, it has been possible to establish and contextualize the geographical framework of the archaeological phenomenon that occupies our work. To compile the catalogue, we conducted an intensive bibliographical search using a variety of sources. These included printed and digital publications such as peer-reviewed articles, monographs and conference proceedings, alongside reliable online archaeological databases. We also accessed bibliographic databases including JSTOR and Scopus to ensure comprehensive coverage. Additionally, the catalogue incorporates data obtained through our own direct fieldwork, which has allowed us to verify and complement existing published information. In total, we have counted 59 caves and shelters in what today constitute France (31), Spain (25), Italy (2) and the United Kingdom (1). This translates to 775 hand representations unevenly distributed among the different archaeological sites. Thus, in decreasing order, France records 447 hand representations, Spain 317 (one in Gibraltar) and Italy 11 (Fig. 1; Supp. 1). Some of these representations are under study pending verification of their originality/chronology, such as the caves of Mosseguellos, Pindal, Calaveras, or Pileta (discussion in Sanchidrián et al. Reference Sanchidrián, Medina Alcaide, Romero, de las Heras, Lasheras, Arrizabalaga and De la Rasilla2012).

Figure 1. Hand representations attributed to the Upper Palaeolithic. Positive, negative, or mixed technique. (1) Paglicci; (2) Perciata; (3) Gorham; (4) Askondo; (5) Altamira; (6) Ardales; (7) Calaveras; (8) Castillo; (9: Mosseguellos; (10) Cudón; (11) Estrellas; (12) Fuente del Salín; (13) Fuente del Trucho; (14) La Garma; (15) Higuerón o Tesoro; (16) La Lastrilla; (17) Les Pedroses; (18) Maltravieso; (19) Nerja; (20) Palomas IV; (21) Pasiega; (22) Peña Candamo; (23) Pileta; (24) Salitre; (25) Tito Bustillo; (26) Victoria: (27) Pindal; 28) Abri du Poisson; (29) Abri Labattut; (30) Baume-Latrone; (31) Ebbou; (32) Bayol; (33) Bernifal; (34) Beyssac/Commarque; (35) Bison; (36) Bourgnetou; (37) Chauvet; (38) Combarelles; (39) Combe-Negre; (40) Cosquer; (41) Ebbou; (42) Emilie; (43) Erberua; (44) Les FIeux; (45) Font de Gaume; (46) Gargas; (47) Grande Grotte d’Arcy; (48) Margot; (49) Merveilles; (50) Moulin de Laguenay; (51) Pech-Merle; (52) Portel; (53) Roc de Vezac; (54) Rocadour; (55) Tibiran; (56) Trois-Fréres; (57) Villhonneur; (58) Archammbeau (Les Eyzies); (59) Montera del Torero.

Globally, two main areas of concentration can be observed: the first, on the Cantabrian coast of the Iberian peninsula; and a second grouping in the Dordogne, north of the Pyrenees (Fig. 2). Both are classic areas in the study of rock art with a research tradition dating back to the very origins of the discipline. However, in recent years, the south of the Iberian peninsula stands out, where more caves and hand representations are progressively being added to the catalogue, due to the intensive work of systematic prospecting of caves and shelters such as the sites of Pileta, Gorham, Nerja, Estrellas, Palomas IV and Ardales (Collado Giraldo et al. Reference Collado Giraldo, Bea and Ramos Muñoz2019; Salvador Fernández-Sánchez et al. Reference Salvador Fernández-Sánchez, Collado Giraldo and Vijande Vila2021; Simón-Vallejo et al. Reference Simón-Vallejo, Cortés-Sánchez and Finlayson2018; Reference Simón-Vallejo, Parrilla-Giráldez, Macías Tejada, Cortés Sánchez, Bea, Domingo, Mazo, Montes and Rodanés2021).

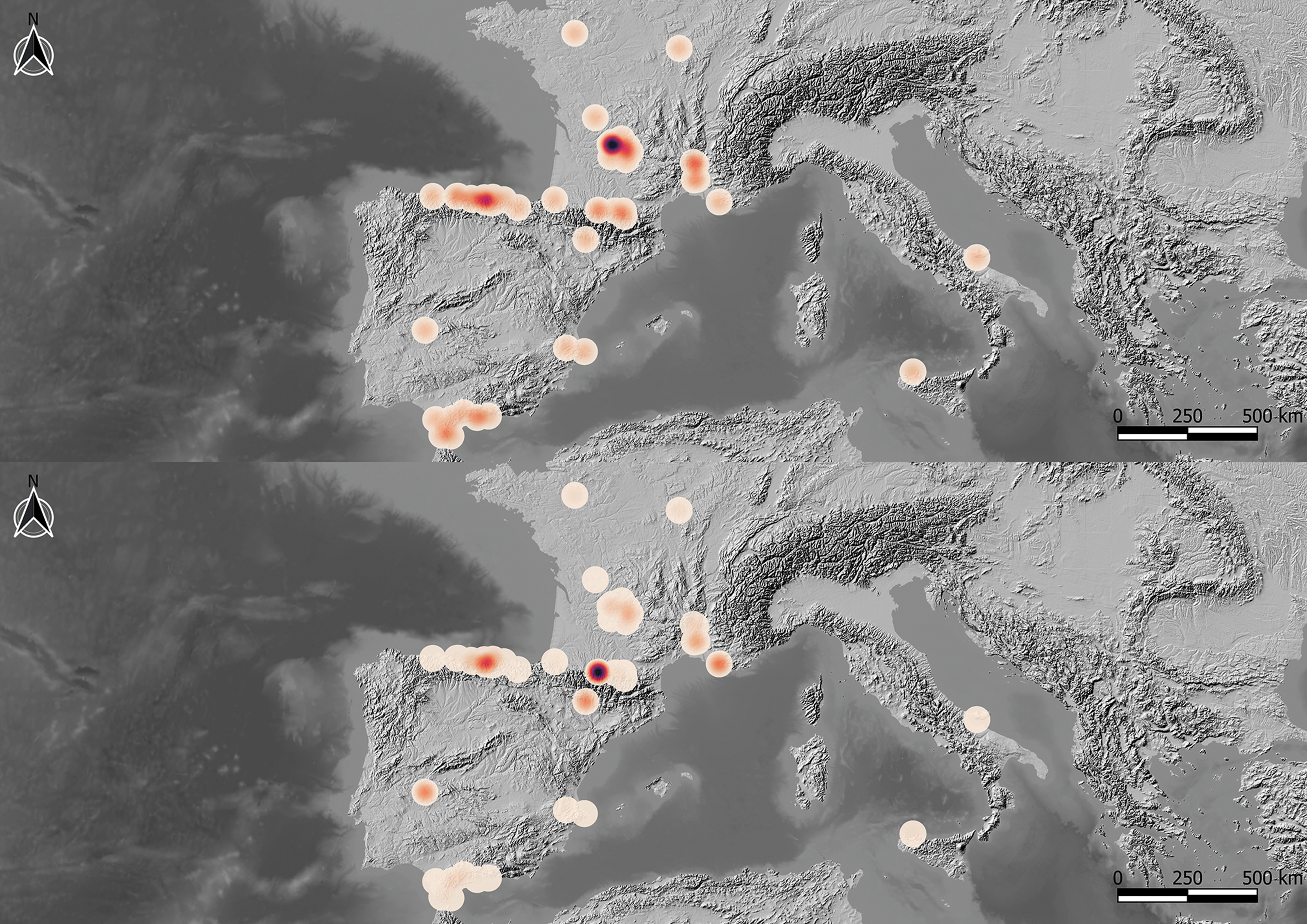

Figure 2. Geographical distribution of Palaeolithic hand stencils. Kernel heat map. (a) density of caves with hands; (b) density of number of hands per cave.

To offer a broader comparative framework, it is worth highlighting that the Cantabrian region includes sites such as El Castillo or Fuente del Salín, where hand stencils are relatively numerous but still far from the exceptional concentration seen in Gargas (Hautes-Pyrénées). In this latter region, despite having several decorated caves, the number of hand representations per site is often below 10, with the remarkable exception of Gargas itself. In contrast, the Pyrenean sites tend to show intermediate values, combining multiple caves with small to moderate groups of hands. In the south, however, we do not find large concentrations of hands, most of them being grouped in small sets or even individually. The interior of the Iberian peninsula represents a real void, partly due to its geological and climatic characteristics that prioritize the presence of open-air rock-art sites where painting is not present or has not been preserved.

It is important to highlight the difference between the density of caves or shelters with hand representations and the number of hands documented in each of these sites. In terms of the number of caves, the Cantabrian coast and southwestern France concentrate the largest number of sites with these graphic representations (Fig. 2a). However, when analysing the number of hands per site (Fig. 2b), it is observed that the density decreases on the Cantabrian coast and in southern France, while the Gargas cave stands out with the highest concentration of these representations (231 hands). A relevant fact is the low density of hands per cave in the south of the Iberian Peninsula, northern France and Italy; despite having several sites, they show a reduced number of such graphics. Equally significant is the case of the Dordogne, where, although it presents a considerable concentration of caves with hands, all of them contain a very low number of representations (<10).

Technical features

Analysis of the techniques used to represent hands in rock art reveals two main methods of applying the pigment: the negative hand stencil, which represents 88.52 per cent of the total, consists of projecting pigment over a hand placed on the wall, creating an outline when the hand is removed; the positive hand stencil, with only 10.45 per cent of the hands, involves applying pigment directly to the palm and then pressing it against the wall; and the mixed technique, with only 0.52 per cent, which combines both techniques to achieve a high contrast between the white pigment of the hand and the background.

In general terms, red is the most predominant colour, with 499 representations, as in the El Castillo cave where only this colour is used in its 78 cases. Black, derived from manganese or charcoal, appears in 245 hands, while brown—clay—is less frequent (7). According to Barrière (Reference Barrière1976), the choice between iron oxide and manganese can influence the final colour due to their different solubility and coverage properties. Colours such as yellow (24) and white (5) are less common and are found in specific caves such as Fuente del Trucho and La Garma for yellow and Maltravieso and Gargas for white, suggesting the use of minerals from the nearby environment for the creation of pigments (Menu & Walter Reference Menu and Walter1992).

Leroi-Gourhan (Reference Leroi-Gourhan1967) observes that the distribution of colours in the Gargas cave seems to follow a systematic pattern. He notes that the density of figures increases from the entrance towards the deeper areas of the cave, which does not seem accidental. He also identifies a progression in the proportion of red hands in relation to black ones, which also increases as one moves deeper into the cave. According to him, in most cases, the series of hands begin with black hands located in concavities, and then a transition of colours is observed, with a placement pattern not found in other caves.

It must be clarified that it is possible the artists responsible for these paintings used their non-dominant hand to place on the wall, thereby freeing their dominant hand to hold the projection tools and pigment container, assuming the artist performed the activity alone. On the other hand, if we consider that two people were involved in this action—the hand stenciller and the one spraying the pigment—it would be more logical to think that the subject placed their dominant hand on the wall. Without archaeological evidence to identify the exact execution process, drawing definitive conclusions about the meaning of the laterality of the represented hands remains a complicated task.

In this study, we start from the premise that the artists responsible for the hand representations used their dominant hand to perform the main action of stencil production. In the case of positive stencils, this involves placing the dominant hand directly on the surface to transfer pigment; for negative stencils, it implies that the dominant hand was used to spray the pigment while the non-dominant hand was placed on the wall. Although these manual operations differ, in both cases the dominant hand would be actively involved in the process and thus is likely to be more frequently represented on the wall.

The orientation of the hands in the stencils—specifically whether they were placed palm-down or palm-up—is a relevant aspect, particularly in discussions of handedness. It is generally assumed that most hands were positioned with the palm facing the wall. This inference is based on anatomical features visible in the silhouettes, especially the arrangement of the fingers and thumb, which typically correspond to the dorsal (back) view of the hand. Moreover, our experimental studies have shown that placing the palm against the surface is more ergonomic and provides greater stability when blowing pigment, supporting this interpretation.

If we consider that all the hands were made with the palm placed on the wall or ceiling of the cave—based on our own experiments (Fernández-Navarro et al. in press) their laterality can be analysed. In many cases, especially in French caves, laterality has not been recorded or identified during their study, so a considerable number of hands have unknown laterality. The proportion of 50.45 per cent right-handed versus 23.74 per cent left-handed is higher compared to data collected in contemporary society, where between 8 and 13 per cent of the population are documented as left-handed. The remaining percentage corresponds to cases where handedness could not be determined due to unclear indicators or insufficient sample quality and is therefore classified as undeterminable.

Chronological data

As with the rest of Palaeolithic rock art, direct dating of hand paintings is extremely limited, leading researchers to contextualize them based on other spatially related remains. This topic has been the subject of a prolonged debate that continues to this day, with new data gradually adding to the discussion (see Pettit et al. Reference Pettitt, Arias, García-Diez, Bueno-Ramírez and Bahn2015).

The first synthesis of rock art in the Cantabrian region (Alcalde del Río & Breuil Reference Alcalde del Río and Breuil1911) suggested an ancient chronology for the hands, considering them contemporary with the first graphic representations based on superimpositions. Breuil and Obermaier (Reference Breuil and Obermaier1935) maintained this opinion, describing them as ‘very archaic’ and associating them with red disks, placing these images in the Aurignacian–Perigordian artistic cycle, based on parietal stratigraphy and the lack of association with other representations.

Leroi-Gourhan (Reference Leroi-Gourhan1967; Reference Leroi-Gourhan1968) recognized the ambiguity of these chronologies due to the lack of data, but proposed that the motifs were concentrated in periods prior to the Magdalenian, suggesting some representations in his early Style IV. Although it was difficult to assign a precise chronology in some caves, such as Les Combarelles, Font-de-Gaume and El Castillo, he linked them to an early Style III or earlier, from the Solutrean or early Magdalenian.

This position was widely accepted, and subsequent studies placed this phenomenon in the Gravettian or stages prior to the Magdalenian (Barrière & Suères Reference Barrière and Suères1993; Clottes & Courtin Reference Clottes and Courtin1996; Foucher et al. Reference Foucher, Foucher and Rumeau2007; González-Sainz Reference González Sainz1999; Lorblanchet Reference Lorblanchet1995; Reference Lorblanchet2010; Von Petzinger & Nowell Reference Von Petzinger and Nowell2011).

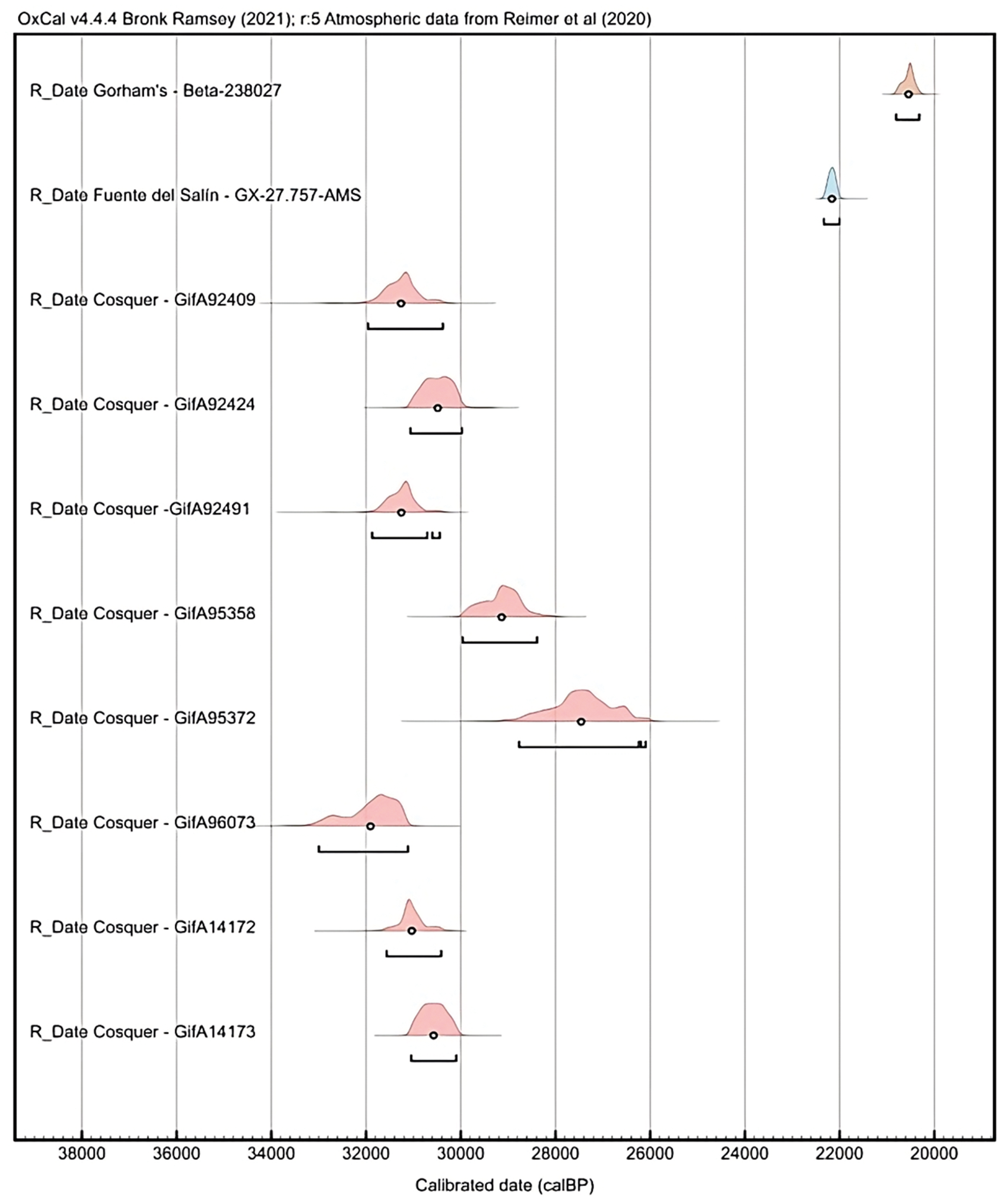

Recently, García-Díez et al. (Reference García-Díez, Garrido, Hoffmannn, Pettit, Pike and Zilhao2015) carried out a critical review regarding the antiquity of these images in the context of the new Uranium-Thorium minimum age results for the hand stencils in El Castillo cave. Based on technique and colour, together with a critical assessment of the available chronological data, the author concludes that these representations can generally be considered as a diachronic phenomenon—likely corresponding to an initial, non-figurative phase (Aurignacian or earlier) of European Palaeolithic cave art. Unfortunately, we do not have many direct dates of hand representations (Fig. 3). In the Cosquer cave (Clottes et al. Reference Clottes, Beltrán, Courtin and Cosquer1992), we have several results for the hands MR7 (27,110±430; 27,110 ± 400 and 26,180±370 bp); M12 (24,840±340; 23,150±620 bp) and M19 (27,740±410 bp). Alongside, the sample from Fuente del Salín (González Morales & Moure Romanillo Reference González Morales, Moure Romanillo and Ontañón2008) provides a somewhat more recent date of 18,200±70 bp, although the authors doubt its validity due to the amount of sample analysed. The most recent hand that has been directly dated is the only one documented in Gorham’s cave with an age of 16,990±90 bp (AMS) (Simón-Vallejo et al. Reference Simón-Vallejo, Cortés-Sánchez and Finlayson2018).

Figure 3. Direct dating for European Upper Palaeolithic hand stencils.

Additionally, we have dates resulting from indirectly dating Palaeolithic hand paintings, using physicochemical analyses, associations, linkages and superimpositions of other evidence or speleothems (Jaubert Reference Jaubert2004) (Supp. 2).

A notable example is the El Castillo cave. The calcite formed over one of the hands of the Gallery of Hands (O-64, O-65 and O-58) has allowed establishing minimum ages of more than 20,600, 22,150 or 24,200 years, while another, belonging to the Ceiling of Hands, could be older, with ages over 24,730 or 37,300 years (O-90 and O-82) (Pike et al. Reference Pike, Hoffmann and García-Diez2012). In the Fuente del Trucho cave (Spain), the same procedure was followed, allowing the dating of six cases through the U/Th technique on calcite crusts. The oldest date obtained exceeds 27,000 years (Hoffmann et al. Reference Hoffmann, Utrilla and Bea2017; Utrilla et al. Reference Utrilla, Baldellou, Bea, Montes and Domingo2014). In Maltravieso, five samples were dated from carbonates extracted from different areas of the same red negative hand. The oldest date (MAL 13) establishes a minimum age of 66.7 kya for this hand (Hoffmann et al. Reference Hoffmann, Standish and García-Diez2018). Additionally, in the La Garma cave, the datings have provided dates of more than 33,000 years for a negative hand (Arias & Ontañón Reference Arias, Ontañón and Ontañón2008; González Sainz Reference González Sainz, de Balbín Behrmann and Bueno Ramírez2003).

Indeed, some of the results have been questioned by other researchers due to methodological problems presented by the uranium series dating system and the lack of control in the protocol used (Aubert et al. Reference Aubert, Brumm and Huntley2018; Hoffmann et al. Reference Hoffmann, Standish and García-Diez2018; Pearce & Bonneau Reference Pearce and Bonneau2018; Pike Reference Pike, David and McNiven2017; White et al. Reference White, Bosinski and Bourrillon2020). The authors of this last paper (White et al. Reference White, Bosinski and Bourrillon2020) argue that, despite previous claims suggesting that Neanderthals were the creators of parietal art in Europe, there is no conclusive archaeological evidence to support this hypothesis.

On the other hand, we have dates resulting from dating not the hand itself but associations, linkages and superimpositions of other organic remains such as charcoal or bone. In Fuente del Salín, charcoals recovered from hearths near a set of hands near the original entrance were dated to approximately 22,340±510 bp, suggesting a relationship between the combustion structure and the creation of the paintings (Moure Romanillo & González Morales Reference Moure Romanillo and González Morales1992). The appearance of processed ochre and shells with residues of that mineral processing reinforces this hypothesis (Cuenca-Solana et al. Reference Cuenca-Solana, Gutiérrez-Zugasti and González-Morales2013; Reference Cuenca-Solana, Gutiérrez-Zugasti and Ruiz Redondo2016). In the Labattut cave, a detached block with a hand representation corresponds to the Gravettian period, according to its stratigraphic context. However, this chronology has been questioned (Ucko & Rosenfeld Reference Ucko and Rosenfeld1967).

In Moulin de Laguenay (France), the dating of charcoal associated with one of the hearths under the hand stencil offered an age of 26,770 years bp (Pigeaud & Primault Reference Pigeaud and Primault2007). In Vilhonneur, the human anthropological remains derived from the individual found within the cavity are dated between 27,000 and 26,000 years bp according to radiometric dating of human rib fragments (Human rib n 18 27,110±210 bp; Human rib n 19 26,790±190 bp). This individual is associated with the same phase of the creation of the hand stencil. In Pech-Merle, a measure of 24,640±390 bp (Gif A 95357) was obtained on charcoal from the panel of the dotted horses, significantly associated with six hand representations, based on both the compositional phases of the panel and pigment analysis of several figures, including two hands and the horses themselves (Lorblanchet Reference Lorblanchet1995). At the entrance of ‘galerie Rouzaud’ in the Chauvet cave, the study of the humid fraction of a black mammoth superimposed on a red negative hand was dated to 29,300±1300 bp, making the hand older (Quiles et al. Reference Quiles, Valladas and Bocherens2016).

In the case of the Grande Grotte de Arcy-sur-Cure, a date of 26,700±410 bp was obtained on a bone recovered at the foot of a panel that included a partial hand representation (Baffier & Girard Reference Baffier and Girard2007; Girard et al. Reference Girard, Baffier, Valladas and Hedges1995 ). We have the dating of a bone embedded in a crack in a wall near the Panel of Hands in Gargas, with a result of 26,860±460 bp (Foucher et al. Reference Foucher, Foucher and Rumeau2007).

In summary, the chronology of Palaeolithic hands continues to be a challenge due to the lack of direct datings and the methodological complexity involved in their analysis. It is crucial to advance in systematic dating of caves that still lack precise dates, using combined techniques and consistent parameters to improve our understanding of the temporal context in which these representations were created. Even so, the available data are situated in a range that has the Gravettian at its central point, with some cases slightly earlier and later.

Interpretations

The diversity of interpretations in the study of hands in rock art has generated intense debate among researchers, revealing the complexity and scope of these representations in different contexts and historical periods. From the earliest attempts to decipher the meaning of hands on the walls of Upper Palaeolithic European caves to contemporary explorations covering other geographies and periods, analysis of these images has been a constant challenge. Interpretations of the meaning and function of the represented hands have ranged from symbolic, cultural, medical and communicative approaches. In this context, the search for parallels in other historical periods and ethnography has been crucial to shed light on the function and meaning of hands in Palaeolithic rock art.

a) Signatures/autographs

Gregg (Reference Gregg2008), supported by Taçon et al. (Reference Taçon, Tan and O’Connor2014), proposes that hand marks on cave walls could serve as signatures or autographs of the artists, leaving their personal mark and identity in the rock-art space. This idea suggests that the hands were a way for artists to identify and recognize themselves in the context of their art. In the Vilhonneur cave (France), a partial skeleton of a young adult was found just below a handprint, leading to the hypothesis that this print could symbolize a form of personal identity and individualization (Henry-Gambier et al. Reference Henry-Gambier, Beauval, Airvaux, Aujoulat, Baratin and Buisson-Catil2007).

In Australia, the concept of ‘signature’ in rock paintings is also used to describe hand marks as a record of identity. According to Basedow (Reference Basedow1925), Australian Aboriginals could recognize the hand marks of their family members and tribe members, even if they were not present when they were made. These prints are interpreted as a ‘record of individuality’ and a form of deep connection with spirits and tribal identity.

b) Substitutes for animals/female signs

Leroi-Gourhan (Reference Leroi-Gourhan1968) from his structuralist perspective, understood these images as possible symbols of the feminine, as were others like vulvas or open signs. This researcher found that hands were often accompanied by alpha or male signs and were found in situations where beta signs reached their maximum frequency. Additionally, he suggested that in some cavities like Gargas and Tibiran, hands could be substitutes for animals, while in others, such as Pech-Merle in particular, they could replace female signs.

c) Symbols of power or possession

The handprint would be the means by which individuals in these societies would mark a place, location, or cave as their own. It has also been proposed that the act of leaving a handprint on the wall surface indicated the power of that individual within the group, thus debarring a large part of the group from this pictorial activity (Clottes & Lewis-Williams Reference Clottes and Lewis-Williams1996).

d) Elements within the shamanic world

An alternative conception of painted hands in caves is to see them as a way to connect with the beyond or magical worlds. According to Clottes and Lewis-Williams (Reference Clottes and Lewis-Williams1996), the crucial aspect was not simply the image of the hands on the walls, but the ritual process of connecting with the divine or spiritual that this act implied. In this context, covering hands and cave surfaces was considered a significant act in itself, and bent fingers could have additional symbolic value, reinforcing the ritual nature of the act.

Additionally, it is suggested that the amputation of phalanges may have been an essential component in shamanic initiation rites, similar to practices observed in different tribes in South Africa (Drennan Reference Drennan1937). The theory is that the pain caused by finger mutilation could induce an altered state of consciousness, facilitating contact with the spirit world. Printing the mark of a mutilated hand on the wall could have been a way to establish a direct and deep connection with the beyond.

In parallel, the literature on groups from the southwestern Cape of South Africa, as described by Manhire (Reference Manhire1998), suggests that adult hand stencils may have been created during healing ceremonies, while smaller stencils, possibly of young individuals, may have been made during initiation ceremonies. This theory has also been proposed for Palaeolithic art (Guthrie Reference Guthrie2005), suggesting that painted hands may have had similar ceremonial purposes in the palaeolithic context.

e) Space indicators

In Cosquer, as Clottes and Courtin (Reference Clottes and Courtin1996) pointed out, the distribution of hands seems to create a path leading to a large, 24 m deep pit, which could have been either a threat to these societies or a place with high symbolic content (Rouillon Reference Rouillon2006). This theory of the function of hands (or punctuation marks) as topographical markers is also shared with other authors (Collado Giraldo Reference Collado Giraldo2018; Foucher Reference Foucher and Cuisenier1991; Groenen Reference Groenen1990; Reference Groenen2011; Reference Groenen2013; Pigeaud Reference Pigeaud, Vialou, Renault-Miskowsky and Patou-Mathis2005). It has also recently been suggested that these figures seem to have been deliberately placed in association with specific features of the walls or geological features, indicating that the topography of the cave walls may have been important (Pettitt et al. Reference Pettitt, Castillejo, Arias, Ontañón Peredo and Harrison2014).

f) Communication system or language

The repetition of certain hand positions over a wide geographical area has led some researchers to consider that these representations could constitute a symbolic code or language. Leroi-Gourhan (Reference Leroi-Gourhan1967) proposed that bent fingers could form a gestural code and studied how hands were associated between panels and within the same panel in caves. This approach suggests that prehistoric hunter-gatherers may have used a non-verbal communication system where gestures were used to describe the type of prey sighted, as in the tribes of Botswana or Kalahari (Mohr Reference Mohr2014; Mohr & Fehn Reference Mohr and Fehn2013; Mohr et al. Reference Mohr, Fehn and de Voogt2019).

Leroi-Gourhan identified five basic combinations in the Gargas cave, which he tried to correlate with five animal species based on their frequency of appearance (Leroi-Gourhan Reference Leroi-Gourhan1967). However, other researchers, such as Courtin (Clottes & Courtin Reference Clottes and Courtin1996) and Pradel (Reference Pradel1975), found up to 16 different combinations in Gargas. In contrast, Clottes and Courtin (Reference Clottes and Courtin1996) observed only five prominent combinations in the Cosquer cave. Rouillon (Reference Rouillon2006) proposed that in the Cosquer cave, hands could have been used for counting, with each finger representing a number from 1 to 5.

g) Mutilations

Since the discovery of incomplete hand representations in the caves of Gargas and Tibiran, the hypothesis of finger mutilation has been a recurring issue in the historiography of prehistoric art. Luquet (Reference Luquet1926) proposed a classification of mutilations into two types: ritual (linked to propitiatory rites or ceremonies) and profane (related to tribal identification or punishment). This view was supported by Cartailhac, Breuil, Casteret (Reference Casteret1930) and Verbrugge (Reference Verbrugge1970), who associated ritual mutilations with practices seen in contemporary archaic cultures, such as amputations used to appeal to deities, express mourning, or signify civil status (McCauley et al. Reference McCauley, Maxwell and Collard2018). Breuil (Reference Breuil1952) connected the amputations to hunting activities, while Casteret (Reference Casteret1930) and Lundborg (Reference Lundborg2014) linked them to sacrificial and initiation rites.

In the Tibiran cave, nearly all the hand stencils are incomplete, and similar patterns are found in Gargas and Maltravieso. In the latter, the missing finger is most commonly the pinky, which led Sahly (Reference Sahly1966) and Delluc and Delluc (Reference Delluc and Delluc1991) to interpret these absences as the result of ritual surgical operations.

In contrast, Luquet (Reference Luquet1926) and Leroi-Gourhan (Reference Leroi-Gourhan1967) rejected the mutilation hypothesis, suggesting instead that the fingers were bent, not severed—though without providing a definitive explanation. Leroi-Gourhan also argued that amputations were unlikely in the Upper Palaeolithic, as losing fingers would impair essential survival skills. This view is echoed by Ripoll López et al. (Reference Ripoll López, Ripoll Perelló, Collado Giraldo, Mas Cornélla, Jordá Pardo and de Estudios Paleolíticos1999), who pointed out the absence of skeletal evidence supporting widespread amputations.

Another line of interpretation posits that the missing fingers may reflect natural causes such as frostbite, inbreeding, hunting accidents, or other mechanical injuries. This theory relates the visible mutilations to extreme climatic conditions, such as those during the Upper Palaeolithic crossing of the Pyrenees (Utrilla Reference Utrilla, Hernández and Soler2005; Utrilla & Bea Reference Utrilla, Bea, Bueno-Ramírez and Bahn2015).

Finally, several authors, mainly with medical backgrounds, have proposed a pathological origin. Sahly (Reference Sahly1966), building on earlier suggestions by Cartailhac and Breuil (Reference Cartailhac and Breuil1910) and later Barrière (Reference Barrière1976), argued that the absences might be due to diseases rather than intentional gestures or finger bending. He noted that some apparent cuts occur mid-phalange rather than at interphalangeal joints, which would be expected if the fingers were simply flexed. Based on his medical training, Sahly compiled a catalogue of potential diagnoses, identifying Raynaud’s disease—affecting blood flow in the fingers—as the most plausible cause for the loss of phalanges under cold environmental conditions.

According to recent studies, and as we will see in more detail below, hand representations appear to play a cohesive role within rock art. Spaey et al. (Reference Spaey, Garate and Irurtzun2024; Reference Spaey, Arriolabengoa and Intxaurbe2025) have emphasized that many of these images are located in accessible and visible areas of the caves, suggesting a clear public dimension in both their placement and function. Fernández-Navarro et al.2025) (Reference Fernández-Navarro, Camarós and Garate2022; have pointed out that both adults and children, of both sexes, participated in their creation, indicating a collective and fundamental role played by various members of the group in these graphic manifestations. Additionally, studies by Etxepare and Irurtzun (Reference Etxepare and Irurtzun2021) have proposed that these hands may have formed part of a non-verbal language, used as a means of symbolic communication within Palaeolithic communities. Taken together, these investigations reinforce the idea that the hands not only represent individual identities, but also shared social bonds, communal dynamics and possible forms of codified expression within the symbolic space of rock art.

New insights in hand stencils study

Currently, analysis of hand representations is being approached from multiple and novel perspectives, yielding very interesting results and opening new avenues of research. Firstly, there is an approach to the variability in the arrangement of fingers by observing their behaviour at a geographical level. Alongside this, technical analysis of the operational chain offers a complete characterization of the process of creating hand representations. Additionally, morphometric analysis of these representations helps clarify the sex and age of the individuals involved in creating these motifs. Finally, macro- and micro-scale spatial analysis offers a new perspective on the role these figures played, their arrangement within the cavities and their relationships with other motifs.

Finger/hand combination

The repetition of similar hand combinations in caves located far apart, along with their apparent arrangement, has led to the hypothesis of a possible non-verbal communication system. Leroi-Gourhan (Reference Leroi-Gourhan1967), through a semiotic analysis of the Gargas cave, proposed a gestural code based on the folding of certain fingers, identifying five frequent combinations and suggesting that the hands occupied a central position on the panels, potentially replacing the so-called beta signs.

Several authors have documented the different ‘modes of amputation’ in Gargas (Barrière Reference Barrière1976; Casteret Reference Casteret1930; Sahly Reference Sahly1966. Similarly Clottes and Courtin, (Reference Clottes and Courtin1996) studied the Cosquer cave and identified five main combinations, which led Rouillon (Reference Rouillon2006) to propose a numerical counting system from 1 to 5, comparable to those seen in modern societies.

In line with this idea, Etxepare and Irurtzun (Reference Etxepare and Irurtzun2021) recently analysed the hands in Gargas and found that all the observed combinations can be reproduced in the air without the need for wall support. This finding supports the hypothesis that such hand stencils may be part of an alternative sign language. Similar gestural systems have been documented among Australian First Nations (Kendon Reference Kendon and Poyatos1988), Native American Plains peoples (Davis & McKay-Cody Reference Davis and McKay-Cody2010) and San (Bushmen) of the Kalahari Desert (Pradel Reference Pradel1975).

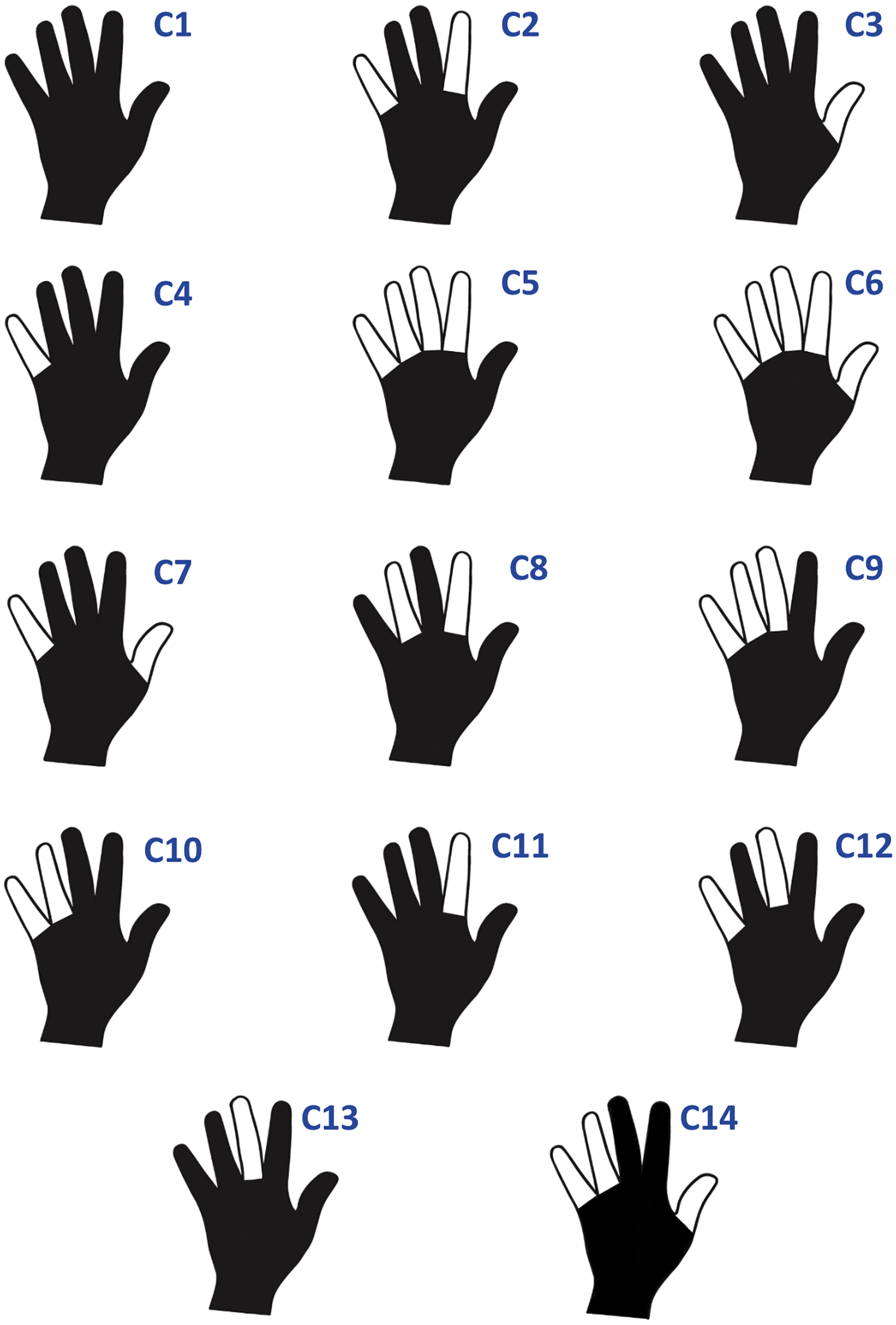

As we have observed, incomplete hands, those showing the absence of phalanges or entire fingers, have sparked various interpretations and theories. This section analyses the variability and distribution of missing finger combinations in incomplete hand representations in Palaeolithic rock art, with a special focus on the Iberian record.

The documentation of hands in France presents significant deficiencies compared to Spain, with complete records for only a few caves like Cosquer or Gargas and a lack of consistency in classifications among authors. While in France classifications are made by complete and half phalanges, in Spain only the presence or absence of phalanges or fingers is considered. This lack of standardization generates inconsistencies in data interpretation and hinders comparative analyses, highlighting the need to unify criteria and reevaluate the archaeological record. Thus, it has been decided to characterize the hands belonging to Spain in this work as it is the best-documented region (Figs 4–5). The different interpretations available for French caves are provided in the supplementary information (Supp. 3).

Figure 4. Finger combinations in the semiotic analysis. (V. Fernández Navarro.)

Figure 5. Geographical distribution of the semantic analysis of hand representations. Top: analysis of the combinations in the Iberian Peninsula. Combinations <2 per cent representativeness; bottom: graphical representation of the peninsular combinations.

Following analysis of the combinations established for the Iberian peninsula, the Cantabrian region shows a clear predominance of the complete hand, representing 92.2 per cent of the cases, indicating that this is the most common combination in the analysed set. In contrast, the other combinations present extremely low frequencies, with percentages ranging between 0.7 and 2.13.

In the Pyrenean region, represented on the southern slope by the Fuente del Trucho cave, the C1 combination, complete hand, again stands out as the most common, although with a lower frequency (46.34 per cent) compared to the previous case. This indicates that, although it remains the predominant combination, there is greater diversity in the presented combinations. The C5 combination, with 24.39 per cent, is the second most frequent, suggesting a certain preference for this particular configuration. The C3, C4, and C6 combinations have intermediate frequencies (between 7.32 and 9.76 per cent), reflecting greater variety in representations compared to the first case. The C8 and C9 combinations are the least common, with only 2.44 per cent each, indicating they are much rarer.

In the southern peninsula, represented by the Maltravieso cave, the C4 combination, missing little finger, overwhelmingly predominates. This suggests a clear preference for this configuration in the analysed set. In contrast, the C1 combination, which was the most frequent in other cases, here only represents 7.69 per cent, showing a change in the usual distribution. The C7, C11 and C12 combinations are rare, with frequencies ranging between 1.92 and 3.85 per cent, suggesting these configurations are much less common in this case. The predominance of C4 over the other combinations reinforces the idea that certain patterns may be more relevant in specific contexts or places.

Finally, in the southern peninsula, the C1 combination shows a significant frequency of 45.45 per cent, indicating it is one of the most common configurations in the analysed data set. The C4 combination, missing the little finger, is also notable, with 31.82 per cent. The C2 combination, missing little finger and index, has a modest presence of 9.09 per cent, while C6 and C23 are even less frequent, with 8.70 per cent and 4.55 per cent respectively. Regarding the missing fingers mainly documented in a few caves, these represent a limited number of individuals, and thus the phenomenon could be considered an epiphenomenon within the wider corpus of hand stencils.

Factorial correspondence analysis (Fig. 6) translates the previously presented data into a series of groups differentiated by their combinations, identified from the original variables. These factors represent sets of variables that are highly correlated with each other and, therefore, group together. Generally, in the first dimension of this analysis, which explains 78.1 per cent of the variability, hands are divided by their laterality, left or right. Thus, in the negative values of the graph, left hands are grouped, and in the positive values, right hands.

Figure 6. Factorial correspondence analysis of the combinations of missing fingers. The total number of hand representations composing each factorial group is in parentheses.

Firstly, for the group of left hands, four subgroups are distinguished. The first corresponds to complete hands and complete hands with forearm. The second also includes complete hands but highlights the absence of the wrist. These first two groups include most of the hands corresponding to the north of the Peninsula, the Cantabrian coast. The third group includes hands with absence of the little finger, and the index and little finger. Notably, this set groups all the southern hands and Maltravieso. Finally, the fourth group includes a greater diversity of hands with missing fingers. Thus, in this category, we observe hands with only the thumb or with two and three missing fingers, highlighting the Fuente del Trucho cave.

Secondly, right hands are divided as follows. The fifth group again includes hands with missing fingers related to the southern peninsula and the Maltravieso cave. The sixth group is associated with complete hands, while the last group includes complete hands with the start of the forearm and a more developed forearm.

In order to validate the grouping obtained through our morphometric analysis, we conducted additional statistical tests, including a hierarchical cluster analysis and the construction of a dendrogram. These independent methods confirmed the existence of the same seven distinct groups identified previously. Furthermore, we applied both the chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test to assess the significance of the associations within our dataset. In all cases, the p-values obtained were below 0.05, supporting the statistical relevance of the observed groupings (Supp. 6).

The recurring patterns of finger–hand combinations across geographically distant Palaeolithic sites suggest more than mere artistic convention—they point to a shared system of visual communication or symbolic language among prehistoric groups. The regional differences observed, with some combinations dominant in specific areas, might reflect distinct social identities, group affiliations or culturally meaningful gestures. The clear organization by finger absence hints at a deliberate and meaningful coding system rather than random variation. Understanding them as part of a broader communicative repertoire invites us to reconsider the social complexity and symbolic sophistication of Palaeolithic communities, highlighting their capacity for abstract expression and shared cultural codes.

Technology and application

This subsection presents the results of the experimental programme developed to replicate pigment recipes and application techniques used in the creation of hand representations in rock art (Fig. 7). This experimental protocol evaluated a total of 14 different techniques (Supp. 5), selected based on archaeological evidence as well as their morphological similarity to documented traditional techniques. Those with very disparate results were immediately discarded, while those with similar outcomes were repeated in an experimental cave for detailed analysis.

Figure 7. Process of creating a blown hand as part of the experimental programme. (A) Colourant material processing; (B) Blowing technique; (C) Resultant hand stencil; (D) In detail macrophotography.

Regarding the recipes, several combinations were designed to evaluate the manageability and effectiveness of different proportions of pigment and binders. Seven experimental mixtures were prepared, using mainly pigments combined with water, egg, animal fat and resins. The latter two proved unsuitable for blowing techniques due to their high viscosity and the need for a continuous heat source to manipulate them.

It was found that a proportion of 10 g pigment to 20 ml water was optimal for handling and application by blowing. Mixtures with higher pigment content produced blends that were too dense to be effective, while those with higher water content resulted in insufficient coverage and dripping on the wall, a phenomenon not documented archaeologically.

For pigment preparation, possible tools used for transforming and pulverizing the colouring material were analysed, such as marine shells and flint implements (Chalmin et al. Reference Chalmin, Menu and Altuna2002; Couraud Reference Couraud1988). Recent studies indicate that limpet shells were used to obtain pigment powder in caves such as Fuente del Salín and Altamira (Cuenca-Solana et al. Reference Cuenca-Solana, Gutiérrez-Zugasti and González-Morales2013; Reference Cuenca-Solana, Gutiérrez-Zugasti and Ruiz Redondo2016). Microscopic wear analysis of 57 limpet shells from Altamira evidenced their use as tools for ochre processing in 51 of the cases studied.

Our experiments confirmed that the percussion technique for pulverizing pigment is the most efficient in terms of time and yield. Additionally, during scraping with Patella shells, a tendency for edge fracture was observed, so we recommend future microscopic analyses of the pulverized material to detect micro-residues indicative of the type of tool (shell or flint), following the proposal by de Balbín Behrmann & Alcolea González (Reference de Balbín Behrmann and Alcolea González2009).

Regarding the application of pigment onto the surface, various techniques were tested, such as the use of brushes, hollow tubes for projection, and blowing liquid or dry pigment (Barrière & Suères Reference Barrière and Suères1993; Carden & Blanco Reference Carden, Blanco, Carden and Blanco2016; Casteret Reference Casteret1930; Leroi-Gourhan Reference Leroi-Gourhan1967; Luquet Reference Luquet1926; Sahly Reference Sahly1966; Verbrugge Reference Verbrugge1970). The most systematic research is based on the work of Lorblanchet (Reference Lorblanchet1980; Reference Lorblanchet1993; Reference Lorblanchet1995), Groenen (Reference Groenen1988) and Vaquero-Turcios (Reference Vaquero Turcios1995), who evaluated the effectiveness of these techniques. Noteworthy are the studies by Santos da Rosa on Levantine art technology (Reference Santos da Rosa2019), which provide valuable information on experimental protocols to follow and on working with post-Palaeolithic societies.

The experimental analysis concluded that the most likely technique for projecting liquid paint is the use of tubes positioned at an approximate 90 degree angle, ruling out blowing dry pigment due to its inability to reproduce the diffuse halos characteristic of archaeological negative handprints (Barriere & Suères Reference Barrière and Suères1993). This finding is supported by the discovery of bird-bone fragments filled with ochre in Altamira, interpreted as possible tubes for paint application, analogous to the modern technique of airbrushing (Gradin Reference Gradin1981; Montes-Barquín et al. Reference Montes-Barquín, Lasheras, de las Heras, Rasines del Río, Fatás Monforte, Baquedano and Jara2004).

Each of the 14 techniques was evaluated using specific parameters such as the shape of the halo, the location of droplets and the distribution of pigment on walls and floors. The tests were conducted in an experimental cave and digitized in 3D through photogrammetry (Structure from Motion, SfM), using a Nikon D850 camera and Agisoft Metashape Pro© software. This allowed the generation of detailed 3D models with high-resolution textures, complemented by macrophotographs for rigorous morphometric analysis and comparison with the archaeological record.

Four techniques stood out for their ability to reproduce the diffuse halo typical of archaeological negative handprints: the use of an airbrush applying the Venturi technique, projection of dry pigment onto a wet wall, projection of dry pigment with a single tube onto a dry wall, and direct projection by mouth blowing.

Nonetheless, the morphological variability of some archaeological hands suggests the use of multiple techniques, highlighting the need for systematic and detailed documentation for future research.

Morphometrical study

The morphological variability in the shape of the hand in Homo sapiens has been extensively documented in various disciplines, including biology, Palaeoanthropology, ergonomics, sports and archaeology (Bolstad et al. Reference Bolstad, Benum and Rokne2001; Fernandez-Navarro et al. Reference Fernández-Navarro, Garate and García Martínez2024b; Karakostis et al. Reference Karakostis, Hotz, Scherf, Wahl and Harvati2018; Kivell et al. Reference Kivell, Baraki, Lockwood, Williams-Hatala and Wood2023; Mandahawi et al. Reference Mandahawi, Imrhan, Al-Shobaki and Sarder2008; Nag et al. Reference Nag, Nag and Desai2003; Nanayakkara et al. Reference Nanayakkara, Cotugno, Vitzilaios, Venetsanos, Nanayakkara and Sahinkaya2017). These studies have revealed that hand morphometry can offer valuable information about the individual, such as their age, sex, weight, height and identification.

Several biometric methods have been proposed to estimate age and biological sex based on the size and shape of archaeological handprints (Chazine & Noury Reference Chazine and Noury2006; Fernández-Navarro et al. Reference Fernández-Navarro, Camarós and Garate2022; Gunn Reference Gunn2006; Guthrie Reference Guthrie2005; Rabazo-Rodríguez et al. Reference Rabazo-Rodríguez, Modesto-Mata, Bermejo and García-Díez2017; Snow Reference Snow2013) as well as to estimate height (Manhire Reference Manhire2018) and laterality (Cashmore et al. Reference Cashmore, Uomini and Chapelain2008; Faurie & Raymond Reference Faurie and Raymond2004; Gunn Reference Gunn2006; Uomini Reference Uomini2009) of the corresponding individuals. The reliability of morphometric studies on Palaeolithic hand representations has often been limited by methodological constraints. Early analyses were conducted with tools available at the time and frequently relied on direct measurements taken in caves or from printed 2D photographs, often using only a small number of metric parameters (Flood Reference Flood1987; Gradin Reference Gradin1981; Groenen Reference Groenen1988). This lack of precision, combined with a high potential for measurement error, compromises the validity of their conclusions. Furthermore, a crucial yet frequently overlooked issue concerns the comparability of archaeological and contemporary datasets. Since statistical comparisons between these datasets underpin most technical approaches, both must share the same nature and format. For instance, a carved hand on a rock surface cannot be directly compared to a digital 2D scan obtained with modern equipment unless both datasets are standardized under equivalent conditions. Only a few previous studies (Carden & Blanco Reference Carden, Blanco, Carden and Blanco2016; Gradin Reference Gradin1981; Gunn Reference Gunn2006; Reference Gunn2007) have addressed this issue explicitly, yet correcting for such disparities is essential to ensure meaningful and robust interpretations.

The possible participation of children in rock art through hand representations is an interesting and prominent topic within this study. Several authors visually identified hand representations that appear to be childlike in different caves, such as in Maltravieso (Ripoll López & Muñoz Ibañez Reference Ripoll López and Muñoz Ibañez2019), Fuente del Trucho (Ripoll López & Muñoz Ibañez Reference Ripoll López and Muñoz Ibañez2019; Utrilla et al. Reference Utrilla, Baldellou, Bea, Viñas, de las Heras, Lasheras, Arrizabalaga and De la Rasilla2013), Fuente del Salín (González Morales & Moure Romanillo Reference González Morales, Moure Romanillo and Ontañón2008), Bayol (Leroi-Gourhan Reference Leroi-Gourhan1968), Gargas (Sahly Reference Sahly1966), Cosquer (Clottes et al. Reference Clottes, Courtin and Vanrell2005), or Grande Grotte Arcy-sur-Cure (Baffier & Girard Reference Baffier and Girard2007). In this regard, a study focused on children’s participation in rock art through the morphometric analysis of hand representations using univariate and multivariate morphometry has been developed (Fernández Navarro et al. Reference Fernández-Navarro, Camarós and Garate2022).

Regarding sex, several researchers have concluded that it is impossible to differentiate between the hands of biological women and men in the archaeological sample (Flood Reference Flood1987; Gradin Reference Gradin1981; Gunn Reference Gunn2006; Henneberg & Mathers Reference Henneberg and Mathers1994). However, those who observed sufficient differences for attribution noted an apparent mixed sexual participation in the creation of these representations (Chazine & Noury Reference Chazine and Noury2006; Groenen Reference Groenen1988; Guthrie Reference Guthrie2005; Mackie Reference Mackie2018; Rabazo-Rodríguez et al. Reference Rabazo-Rodríguez, Modesto-Mata, Bermejo and García-Díez2017; Snow Reference Snow2006; Reference Snow2013; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Ge, Snow, Mitra and Giles2010) (Fig. 8). In addition to hand stencils, other forms of hand-related marks such as finger flutings have also been studied morphometrically. These linear traces, created by dragging fingers across soft cave surfaces, provide complementary information about manual gestures and potentially about the individuals involved in cave-art production (Van Gelder & Nowell Reference Van Gelder, Nowell, Davidson and Nowell2021; Van Gelder & Van Gelder Reference Van Gelder and Van Gelder2005).

Figure 8. Main biometric measurements developed by palaeodemography-related studies based on hand representations in the archaeological record. (a) Groenen Reference Groenen1988; (b) Guthrie Reference Guthrie2005; (c) Gunn Reference Gunn2006; (d) Snow 2006; Reference Snow2013; (e) Wang et al. Reference Wang, Ge, Snow, Mitra and Giles2010; (f) Pettit et al. Reference Pettitt, Arias, García-Diez, Bueno-Ramírez and Bahn2014; (g) Mackie Reference Mackie2015; (h) Rabazo-Rodríguez et al. Reference Rabazo-Rodríguez, Modesto-Mata, Bermejo and García-Díez2017; (i) ‘Manning index’.

Geometric morphometry, a well-established tool in various disciplines, is beginning to show its potential in the field of rock art, with promising results highlighting its applicability in archaeological studies (Charlin & Hernández Llosas Reference Charlin and Hernández Llosas2016; Hayes & van den Bergh Reference Hayes, van den Bergh, O’Connor, Bulbeck and Meyer2018). This methodology has been valued for its ability to provide a detailed and quantitative analysis of shapes and morphological variations, and its usefulness in the archaeological context has been evaluated (Fernández-Navarro et al. Reference Fernández-Navarro, Godinho, García Martínez and Garate Maidagan2024a,Reference Fernández-Navarro, Garate and García Martínezb; Nelson et al. Reference Nelson, Hall, Randolph-Quinney and Sinclair2017). Thus, today, a single study effectively implements this methodology in the archaeological record (Fernández-Navarro et al. Reference Fernández-Navarro, Fidalgo Casares, García Martínez and Garate2025). Within a sample of nine Palaeolithic caves, we analysed 124 negative and positive hand stencils using a 32-point measurement system, located at key biological landmarks. The results point to a homogeneous participation of children, men and women in the creation of hand representations in different caves of the Iberian peninsula, which has been conceived as a reflection of collective inclusion in Palaeolithic symbolic practices, where different social groups actively participated in artistic production, reinforcing the idea of a shared and significant cultural expression in the communities of the time.

Finally, deep learning tools are being applied in the field of rock art (Jalandoni et al. Reference Jalandoni, Zhang and Zaidi2022; Kowlessar et al. Reference Kowlessar, Keal and Wesley2021; Monna et al. Reference Monna, Rolland and Magail2022; Perenleilkhundev et al. Reference Perenleilkhundev, Batdemberel, Battulga and Batsuuri2019). These novel approaches are focused on optimizing artistic documentation, including the detection and identification of motifs, as well as their description and classification. Although machine learning (ML) applications are more advanced in the study of petroglyphs (Horn et al. Reference Horn, Green, Skärström, Lindhé, Peternell and Ling2022; Tsigkas et al. Reference Tsigkas, Sfikas, Pasialis, Vlachopoulos and Nikou2020; Zhu et al. Reference Zhu, Wang, Keogh and Lee2009), their use in the analysis of painted rock art remains limited. While recognition and classification systems focused on human hands are common in the literature for various applications (Amayeh et al. Reference Amayeh, Bebis, Erol and Nicolescu2007; Miguel-Hurtado et al. Reference Miguel-Hurtado, Guest, Stevenage, Neil and Black2016; Wu & Yuan Reference Wu and Yuan2014), only one previous study attempted to analyse the sex of prehistoric hands using similar methodologies (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Ge, Snow, Mitra and Giles2010). This study highlighted the challenges in distinguishing the contours of archaeological hands, leading to the manual application of markers instead of automatic recognition. Although the methodological protocol for contemporary populations was detailed, the archaeological results were not fully developed. In this regard, Fernández-Navarro et al. (Reference Fernández-Navarro, Fidalgo Casares, García Martínez and Garate2025) have developed a deep learning study based on image recognition for sex identification through hand stencil masks, training the program beforehand with contemporary scans and experimental negative hand stencils. The final results indicate a success rate of up to 81.03 per cent for experimental negative hand stencils and 95.08 per cent for contemporary hand scans. Importantly, these results support and complement those previously obtained through traditional morphometrics and geometric morphometrics, showing a high percentage of success.

Spatial distribution

Space is a thorny issue in the study of cave art (Spaey et al. Reference Spaey, Garate and Irurtzun2024). Sometimes at the centre of major theories of meaning (Laming-Emperaire Reference Laming-Emperaire1962; Leroi-Gourhan Reference Leroi-Gourhan1965; Raphaël Reference Raphaël1986), sometimes ignored in the execution of drawings (Breuil Reference Breuil1952), it is a subject that generated a great deal of interest when it came to motifs such as animal figurations or signs. However, in the case of hand stencils, it is interesting to note that, as Pettitt et al. points out, ‘Wider research has concentrated entirely on the identity of hand stencils rather than their context’ (Pettitt et al. Reference Pettitt, Castillejo, Arias, Ontañón Peredo and Harrison2014, 49).

When we mention spatial analysis of hand stencils, in the context of rock art, we refer to the exploration of how representations of hands are distributed and organized within the spaces of caves or archaeological sites. This type of analysis seeks to understand not only the physical location of the hands, but also how their arrangement can offer clues to cultural and social aspects of the Palaeolithic communities that created them. This analysis is carried out at the macro scale, which is the geographical distribution within the caves (grouping, dispersion, choice of sectors and specific areas and walls, topographical characteristics, etc.) and at the micro scale, which includes orientation, positioning and relationship to other motifs and to the wall itself. Although it did not receive the attention it deserved, the issue of the distribution of hand stencils was not entirely ignored. Early on, some authors stated that they were preferentially concentrated at the entrance or in the anterior parts of cavities (Barrière Reference Barrière1977; Delluc Reference Delluc2006; Djindjian Reference Djindjian, Collado Giraldo and García Arranz2015; Leroi-Gourhan Reference Leroi-Gourhan1965). A number of authors also note their grouped distribution, in large sets or in series of two or three, as well as the isolation of certain hand figurations (Barrière Reference Barrière1977; Clottes Reference Clottes2008; Collado Giraldo Reference Collado Giraldo2018; Delluc Reference Delluc2006; Foucher et al. Reference Foucher, Foucher and Rumeau2007; Groenen Reference Groenen1990; Reference Groenen2011; Reference Groenen2016; Leroi-Gourhan Reference Leroi-Gourhan1967; Reference Leroi-Gourhan1992).

Some works have addressed the question of hand stencils in relation to space in a more specific way. It is worth noting the pioneering work of Leroi-Gourhan, who attempted an initial analysis of the organization of these motifs. In 1967, he wrote about the Gargas cave: ‘Au terme de l’analyse d’ensemble, on constate que les mains de Gargas se présentent par groupes de densité croissante, groupes dans lesquels la fréquence relative des mains rouges croit également, de l’entrée vers le fond. Les mains sont fréquemment disposées par couples de même nature, parmi lesquelles se distribuent des mains, noires ou rouges, disposées horizontalement.’ [The overall analysis shows that the hands at Gargas appear in groups of increasing density, groups in which the relative frequency of red hands also increases, from the entrance to the end of the cave. The hands are frequently arranged in pairs of the same type, among which black or red hands are distributed horizontally.] (Leroi-Gourhan Reference Leroi-Gourhan1967, 118). The author also argues that this distribution is organized in the form of a series of panels forming a chain, with isolated hands forming the link between them.

Groenen’s analysis of the Gargas and El Castillo caves is also noteworthy. In the case of the Gargas cave, the author proposes a presentation of six distinct topographical groups (Groenen Reference Groenen1990), while in the case of the El Castillo cave, he notes that the hand stencils are located in the right-hand part of the network, and argues that there is a coherent logic in the distribution of the motifs, which seem to constitute a singular graphic device (Groenen & Groenen Reference Groenen and Groenen2019). Groenen also points out that these figures are unevenly represented in the spaces, and may be linked to openings, arranged in concavities, be the subject of staging or linked to isolated locations. He observes that these motifs can be located both close to areas of access and in difficult-to-access zones involving the crossing of obstacles (Groenen Reference Groenen1990; Reference Groenen2011; Reference Groenen2016).

We should also mention González García’s study of a series of Cantabrian Palaeolithic caves (González García Reference González García1987; Reference González García1990, Reference González García2001) and the work of Collado Giraldo (Reference Collado Giraldo and Clottes2012) in the Maltravieso cave, where he proposes a model of spatial organization based mainly on animal figures.

More recently, as mentioned above, research has been carried out by Pettitt et al. (Reference Pettitt, Castillejo, Arias, Ontañón Peredo and Harrison2014) on the context of the hand stencils in the caves of La Garma and El Castillo, which place the notion of ‘palpation’ and the touching of the wall at the centre of its study. However, this analytical work focuses more on the question of support in a very localized way, rather than on the situation of the hands in the overall structure of the cave.

Although these works represent a first step forward, they face significant methodological limitations. Indeed, it should be pointed out that, until now, the discipline has been confronted with the scarcity of available analytical tools, which limit the possibilities of spatial study to two-dimensional description and representation. Furthermore, the absence of obvious and identical distribution patterns in the different cavities (combined with their morphological variety) has not allowed the development of substantial theories on the organization of hand stencils.

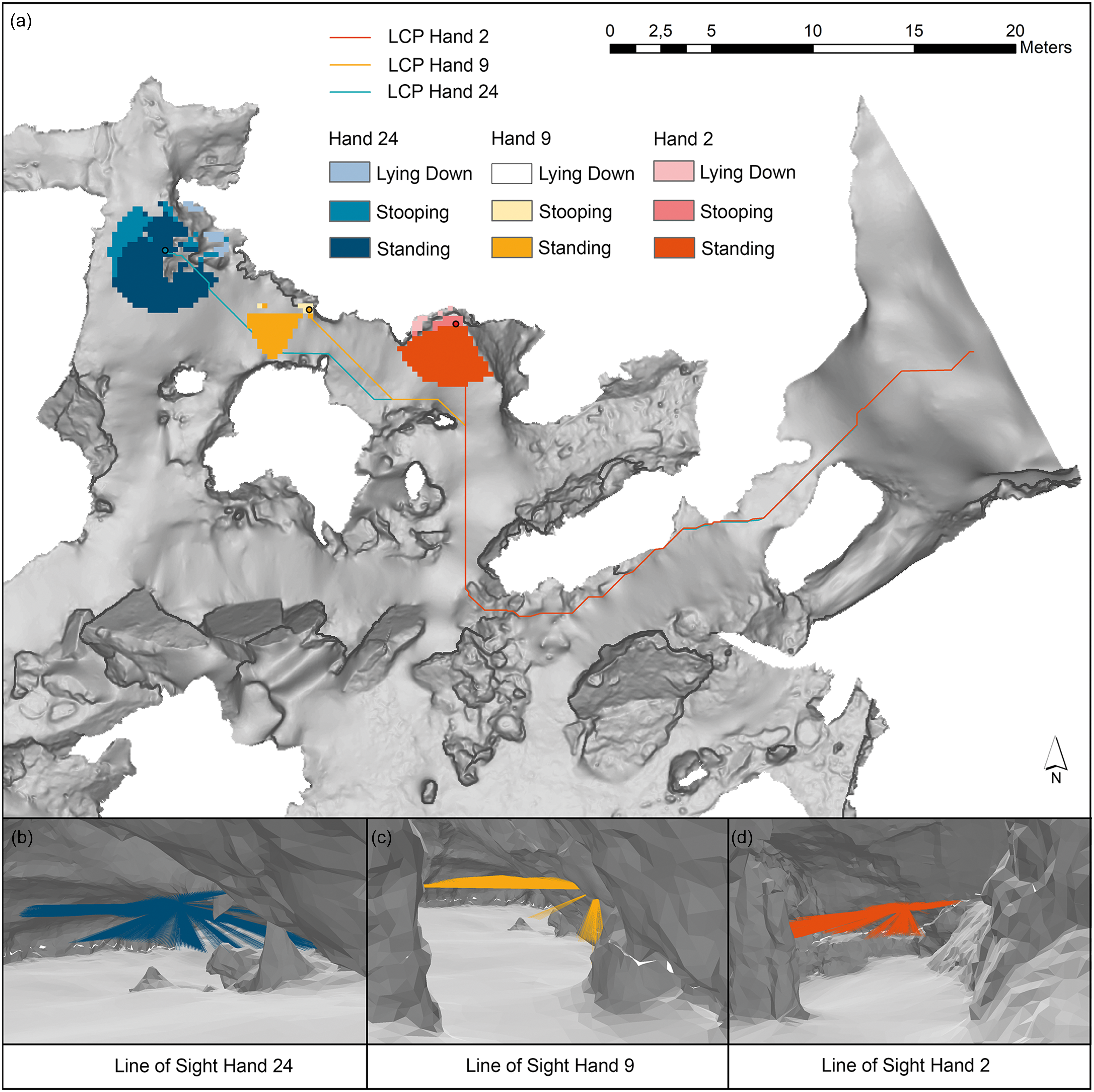

The advent of new technologies offers an opportunity to overcome these problems, as demonstrated by several studies (Intxaurbe et al. Reference Intxaurbe, Garate, Arriolabengoa and Medina-Alcaide2022; Reference Intxaurbe, Arriolabengoa, Garate, Cheng and Pérez-Mejías2023; Reference Intxaurbe, Garate and Arriolabengoa2024), which have proposed working on the basis of quantifiable and objectifiable data, using 3D models and the combined use of GIS and statistics. The use of 3D in the GIS environment makes it possible to perform calculations that cross-reference various types of information, for example, measurements from experimental archaeology, such as the average range of a torch (Medina-Alcaide et al. Reference Medina-Alcaide, Garate and Intxaurbe2021) or the average rate of progression depending on the slope of the ground (Intxaurbe et al. Reference Intxaurbe, Arriolabengoa and Medina-Alcaide2021). This information can be combined with other data, such as archaeological sources (Cox et al. Reference Cox, Ruff, Maier and Mathieson2019; Holt Reference Holt2003; Shackelford Reference Shackelford2007) and estimations (Neufert Reference Neufert1951; Ochoa & García-Diez Reference Ochoa and García-Diez2018; Pastoors & Weniger Reference Pastoors and Weniger2011; Ruiz-Redondo Reference Ruiz-Redondo2014; Villeneuve Reference Villeneuve2003) about the average height and area occupied by an individual. All those can then be cross-referenced with the exact location of each pattern in relation to the overall shape of the cavity. A similar methodological proposal was applied to the El Castillo cave (Cantabria), to analyse the distribution of hand stencils along its network (Spaey et al. Reference Spaey, Arriolabengoa and Intxaurbe2025). To avoid errors relating to the cave’s current morphology (that can differ from its Palaeolithic state), this research carries out an archival and geomorphological analysis and presents a reconstruction of the cave’s shape as encountered by Palaeolithic peoples. On this basis, the method enables addressing issues of visibility (considering an average height of 159.9 cm) and differentiated by posture (standing, stooping, lying down), intervisibility (between motifs), capacity (available volume for potential spectators), accessibility (Least Cost Path, access difficulties) and spatial organization in general (distribution of the motifs within the space and arrangement of the figures in relation to each other) (see examples, Fig. 9).Although they involve a significant degree of complexity, these promising new methods mark the advent of a new chapter in the study of space, one that could enhance our understanding of the palaeolithic social groups that invested the cave during ancient times.

Figure 9. Examples of space analysis of hand stencils on the Ceiling of the Hands in El Castillo cave through GIS. (a) Visibility of hand stencils 2,9 and 24 in function of the public position, in the diameter of a torch, following the data of Medina-Alcaide et al. (Reference Medina-Alcaide, Garate and Intxaurbe2021). These figures are based on occupancy estimates used by Holt (Reference Holt2003) and Intxaurbe et al. (Reference Intxaurbe, Garate, Arriolabengoa and Medina-Alcaide2022 and Reference Intxaurbe, Arriolabengoa, Garate, Cheng and Pérez-Mejías2023), following Neufert (Reference Neufert1951), Pastoors & Weninger (Reference Pastoors and Weniger2011) and Ruiz-Redondo (Reference Ruiz-Redondo2014). They consider that a standing person needs a height greater than 1.599 m and occupies an area of 0.77 m2, while a seated person, needing a height between 0.71 and 1.599 m, occupies 0.90 m², and a person lying down occupies 1.75 m² in areas with a height between 0.24 and 0.71 m. (b) View in ArcScene® of the Line of Sight of hand stencil 24, counting a maximal potential audience of 23 people. (c) View in ArcScene® of the Line of Sight of hand stencil 9, counting a maximal potential audience of 6 people. (d) View in ArcScene® of the Line of Sight of hand stencil 2, counting a maximal potential audience of 13 people.

Discussion and conclusion

The comprehensive study of hand representations in European Palaeolithic rock art has opened new avenues for understanding prehistoric societies from multiple perspectives: biological, cultural and technological. Thus, this research stands as the first systematic attempt to integrate methodological, technological, spatial and semantic approaches in the analysis of Palaeolithic hand representations, offering a holistic view of the phenomenon.

The chronological placement of Palaeolithic hand stencils remains one of the most debated aspects of European rock-art research. Despite early attributions by pioneers like Alcalde del Río and Breuil (Reference Alcalde del Río and Breuil1911) and Breuil and Obermaier (Reference Breuil and Obermaier1935), who proposed a very ancient origin for these motifs based on superimpositions and stylistic associations, the lack of direct dating has long hindered a definitive temporal framework. Leroi-Gourhan (Reference Leroi-Gourhan1967; Reference Leroi-Gourhan1968) also emphasized their antiquity, placing them within his early Style III or even earlier, prior to the Magdalenian. More recent syntheses have generally supported a Gravettian attribution or earlier (e.g. Barrière & Suères Reference Barrière and Suères1993; Clottes & Courtin Reference Clottes and Courtin1996; González-Sainz Reference González Sainz1999; Lorblanchet Reference Lorblanchet1995), yet the emergence of direct Uranium-Thorium dating has challenged and refined these assumptions. Studies by Pike et al. (Reference Pike, Hoffmann and García-Diez2012), García-Díez et al. (Reference García-Díez, Garrido, Hoffmannn, Pettit, Pike and Zilhao2015) and Hoffmann et al. (Reference Hoffmann, Standish and García-Diez2018) have shown that some hand stencils may date back to the Aurignacian or even earlier phases, suggesting a diachronic and persistent tradition. However, these interpretations have been met with scepticism due to methodological critiques (Aubert et al. Reference Aubert, Brumm and Huntley2018; Pearce & Bonneau Reference Pearce and Bonneau2018; White et al. Reference White, Bosinski and Bourrillon2020), particularly regarding protocols and the implications of these dates for Neanderthal authorship. Indirect datings based on charcoal, bones and stratigraphic associations (e.g. Lorblanchet Reference Lorblanchet1995; Moure Romanillo & González Morales Reference Moure Romanillo and González Morales1992; Pigeaud & Primault Reference Pigeaud and Primault2007; Quiles et al. Reference Quiles, Valladas and Bocherens2016) have provided additional support for a Gravettian temporal focus.

Experimental analysis of the techniques used to produce and apply hand representations has revealed a remarkable technological diversity, suggesting a detailed knowledge of the materials and methods employed. This study evaluated 14 different techniques, combining various pigment recipes and application methods—including direct blowing, assisted blowing, manual stamping with wet or dry pigment, and the use of stencils or intermediate supports—highlighting a technical and symbolic intentionality that is more complex than previously assumed. Building on the pioneering works of García-Díez et al. (Reference García-Díez, Garrido, Hoffmannn, Pettit, Pike and Zilhao2015), this approach was complemented by new tests carried out in a controlled experimental setting, discarding those techniques whose results did not faithfully replicate the patterns observed in the archaeological record. The variety of replicated techniques partially aligns with what has been documented by authors such as Carden and Blanco (2018), and methodologically follows a systematic experimental logic similar to that proposed by Santos da Rosa (Reference Santos da Rosa2016), whose protocol stands as a key reference for experimental archaeology applied to rock art. The controlled reproduction of these techniques not only enabled a closer approximation to the material conditions of the graphic gesture, but also suggests the existence of a shared and transmitted technical tradition within these communities, reinforcing the idea that these practices were socially meaningful rather than merely spontaneous.

A further issue that warrants consideration is the number of individuals represented through hand stencils and the dynamics of their production. Although it is commonly assumed that the same person both placed their hand on the wall and applied the pigment, this scenario may not be universal. In some cases, the positioning of the stencils—such as in elevated or awkward locations—suggests the possible involvement of more than one individual, where one served as as stencil and another as the pigment blower. This raises the prospect of collaborative or performative acts, perhaps even ritualized, in the creation of these images. In this study, we have not attempted to determine whether some of the hand stencils may correspond to the same individual. Our focus lies instead on the broader question of human participation in the production of Palaeolithic cave art. While it is often assumed that the same person who placed their hand also applied the pigment, we acknowledge that alternative scenarios involving multiple participants cannot be ruled out and may hold relevance for understanding the social dimensions of these practices.

The semantic study of incomplete hands in Palaeolithic rock art reveals a complex network of interpretations that transcends the mere graphic gesture. The repeated absence of phalanges or entire fingers has traditionally been interpreted as the result of ritual amputation practices (Leroi-Gourhan Reference Leroi-Gourhan1965), although this hypothesis has been questioned by more recent studies that emphasize their potential symbolic or communicative dimension (Bednarik Reference Bednarik2007). The spatial distribution of these hands, along with their intentional placement in specific areas of the caves, suggests a possible visual code or non-verbal sign system, in line with manual languages documented in ethnographic contexts from Oceania, Africa, or North America (Etxepare & Irurztun Reference Etxepare and Irurtzun2021). The identification of recurrent finger combinations—with certain phalanges systematically missing—reinforces this interpretation, especially when these patterns appear in distant caves, suggesting a possible shared or interconnected graphic tradition. Moreover, statistical analysis of these combinations has revealed significant regional patterns that may be linked to specific cultural or territorial identities.