Introduction

‘This is a parliamentary democracy. Therefore the budget right is a core right of parliament. To this extent we will find ways to shape parliamentary co‐decision in such a way that it is nevertheless also market‐conforming, so that the respective signals emerge on the market.’(Merkel, Reference Merkel2011)Footnote 1

In this often‐quoted remark, made during a joint press statement with the then Portuguese Prime Minister Pedro Passos Coelho, Angela Merkel seemed to suggest that pressures emanating from bond markets necessitate restricting the political discretion of elected parliaments. Financial markets trump democracy, she implied in the eyes of her critics (Bofinger et al., Reference Bofinger, Habermas and Nida‐Rümelin2012; Streeck, Reference Streeck2016a).

While Merkel's technocratic language makes it difficult to understand what exactly she intended to say, it is a common assumption that fiscal pressure puts the political systems of developed democracies under stress. As these countries are confronted with an era of ‘permanent austerity’ (Pierson, Reference Pierson1998, Reference Pierson, Levin, Landy and Shapiro2001), and against the backdrop of a decade of harsh austerity programs, political scientists have started to ask whether ‘politics in the age of austerity’ (Schäfer & Streeck, Reference Schäfer and Streeck2013) differs systematically from politics in fiscally more permissive times. As these authors have argued, fiscal pressure threatens to make politics less democratic, as governments have to balance the demands of voters against the demands of bondholders or rating agencies (Hager, Reference Hager2016). Growing fiscal pressure may thus be an important reason why political actors find it increasingly difficult to be both responsive to the preferences of their voters and responsible with regard to the necessities imposed by external constraints (Mair, Reference Mair2009).

Against the backdrop of these arguments, a large literature analyses the policy consequences of fiscal pressure: Which policies do governments pursue when interest burdens increase or the resources available for discretionary spending decline? While several studies investigate the strategic timing of the policy response (Hübscher &Sattler, Reference Hübscher and Sattler2017; Strobl et al., Reference Strobl, Bäck, Müller and Angelova2021), others focus on the design of this response: which types of expenditure do governments cut first (Breunig & Busemeyer, Reference Breunig and Busemeyer2011; Jacques, Reference Jacques2020; Streeck & Mertens, Reference Streeck and Mertens2011), and which expenditure areas are relatively protected? In these studies of policy choices, however, constituents’ demands are typically not investigated. Instead, most studies implicitly assume that voters tend to demand expansionary policies and dislike contractionary measures. General policy responsiveness – meaning the positive relationship between constituents’ preferences and the actions of their representatives (Pitkin, Reference Pitkin1967, p. 233) – is thus expected to be lower in times of tight budgets, since policymakers are forced to adopt unpopular policies.

In addition, studies in this tradition typically assume that ‘the voters’ hold homogenous preferences that governments under fiscal pressure can no longer address (Schäfer & Streeck, Reference Schäfer and Streeck2013, p. 2).Footnote 2 As the recent literature on unequal responsiveness has shown, however, different parts of the population differ substantially in their political demands – and policymakers tend to respond more strongly to the preferences of affluent citizens than to the demands of poorer members of society (Bartels, Reference Bartels2008; Gilens, Reference Gilens2012; Schakel, Reference Schakel2021). Bridging these literatures thus raises the question of how fiscal pressure affects government decisions and whether policy responsiveness declines equally for different social groups when governments are faced with external constraints.

Despite its importance, however, the role of fiscal constraints has remained largely unexplored in discussions of potential mechanisms causing unequal responsiveness. Instead, the debate has mainly focused on money‐based explanations or pointed to participation gaps in politics (see Rosset, Reference Rosset, Machin and Stehr2016 for an overview). Money‐based explanations stress parties’ and policymakers’ dependence on private donors (Gilens, Reference Gilens2015; Lessig, Reference Lessig2011) or the disproportionate influence of business interest groups on policy decisions (Gilens & Page, Reference Gilens and Page2014; Hacker & Pierson, Reference Hacker and Pierson2010). Scholars focusing on participation, in turn, point to both the growing vote abstention of lower social classes and the unequal social make‐up of legislative bodies (Pontusson, Reference Pontusson2015) – in particular the numerical underrepresentation of parliamentarians from the working class (Carnes, Reference Carnes2013; O'Grady, Reference O'Grady2019). While these mechanisms focus mainly on actors or institutions, they tend to ignore the broader structural context in which policymakers operate and take decisions.Footnote 3

In this paper, we emphasize the role of fiscal constraints as a particularly important example of such a structural factor. Specifically, we seek to bring the insights from the literature on ‘permanent austerity’ (Pierson, Reference Pierson1998) into the debate about mechanisms behind unequal responsiveness. We investigate whether fiscal pressure, operationalized as an increase in the interest burden, reduces policy responsiveness, both to average public opinion and towards different sub‐constituencies. Moreover, we analyze whether responsiveness differs for different types of fiscal policy proposals: contractionary proposals such as spending cuts or tax increases as well as expansionary proposals such as tax cuts or spending increases.

Empirically, we focus on the German case. Germany experienced very different levels of fiscal pressure over recent decades and, thus, allows us to exploit important variation on our explanatory variable. Moreover, the German public has been consistently polled on a large number of policy issues since the 1980s. We draw on the database ‘Responsiveness and Public Opinion in Germany’ (ResPOG) (Elsässer et al., Reference Elsässer, Hense and Schäfer2021), which contains public opinion data on about 450 fiscal policy proposals between 1980 and 2016. Based on a case‐by‐case coding of whether these proposals were enacted or not, we find that the general level of policy responsiveness indeed varies over time: Public policy on fiscal issues is more responsive to the preferences of the public when fiscal pressure decreases than when it increases.

Responsiveness is also highly unequal along class lines, which is not surprising, given that opinion differences are more pronounced on fiscal policy issues than on others, and particularly high when it comes to spending cuts. Somewhat surprisingly, though, responsiveness is not more equal in fiscally more permissive times. Whereas in times of maximum fiscal pressure, policy is simply non‐responsive towards all social groups, it is responsive to higher occupational groups when the interest burden decreases. That being said, the main policy type adopted under high fiscal pressure are spending cuts. This is the policy type that disproportionally hurts – and is most strongly opposed by – the working class. Thus, while the general pattern of unequal responsiveness is not driven by high budgetary pressure, the policy implications of unequal responsiveness vary substantially between different fiscal contexts.

In order to develop our argument systematically, we first explain in greater detail why fiscal pressure may reduce policy responsiveness and how this effect may be expected to vary over time and under different types of governments. Afterwards, we describe the dataset and explain our methodological approach. In the empirical section, we estimate the effect of citizens’ preferences on political decision‐making under different levels of fiscal pressure, both for different types of proposals and different subgroups of the population. We conclude with a discussion of the implications of our findings.

Theory

Against the background of rising social inequality in most advanced democracies, there is a renewed interest in the old question whether and how socio‐economic differences translate into unequal political power. Focusing on different dimensions of representational inequality, a growing body of literature has empirically demonstrated that those with less economic resources are (increasingly) excluded from political representation across many liberal democracies. Not only do the poor participate increasingly less in elections and other forms of political activities – people from lower socio‐economic strata are also rarely present in legislative bodies (Best, Reference Best2007; Evans & Tilley, Reference Evans and Tilley2017).

With regard to the (unequal) substantive representation of interests, one important research strand focuses on (unequal) policy responsiveness (Bartels, Reference Bartels2008; Gilens, Reference Gilens2012; Gilens & Page, Reference Gilens and Page2014; Shapiro, Reference Shapiro2011). This literature has extensively analyzed to what extent policy decisions correspond to the preferences of the population and, more recently, to the preferences of different social groups.Footnote 4 Whereas earlier studies have found a fairly strong link between general public opinion and overall policy decisions (see Shapiro, Reference Shapiro2011 for an overview), studies focusing on differential responsiveness have shown that high‐income citizens have much better chances to see their preferences translated into policy change than citizens with lower incomes. Low and even middle‐income groups seem to have no influence once their preferences diverge from those of top income groups. These biases in policy responsiveness have been demonstrated both for the United States and several European countries (Persson & Gilljam, Reference Persson and Gilljam2017; Peters & Ensink, Reference Peters and Ensink2015; Schakel, 2021).

Apart from pointing to the implications of social inequality for democracy, these findings have triggered a lively debate about potential causes underlying this pattern of unequal responsiveness. Up to now, this debate has mainly focused on two types of potential causes (Rosset, Reference Rosset, Machin and Stehr2016). The first type focuses on the political strength of the upper classes and/or business and emphasizes the direct influence of money in politics, both through the financing of parties, candidates and elections (Page & Gilens, Reference Page and Gilens2017) and through the disproportionate influence of business group lobbying (Hacker & Pierson, Reference Hacker and Pierson2010). The second type focuses on the political withdrawal of lower classes. Here, scholars have pointed to the growing social gaps in political participation, political knowledge and other kinds of political involvement (Rosset, Reference Rosset, Machin and Stehr2016; Schäfer & Schwander, Reference Schäfer and Schwander2019). In particular, the descriptive (mis‐)representation of the working class has been discussed as a potential driver of unequal responsiveness (Carnes, Reference Carnes2013; Pontusson, Reference Pontusson2015). While these discussions of different groups’ political resources have identified important factors underlying representational inequalities along class lines, they hardly ever consider the role of structural economic constraints under which policymakers operate. This is also reflected in the methodological approaches in most empirical studies, which – at least implicitly – assume that policymakers always have the same policy options at their disposal.

In this paper, we add to this literature by studying the role of fiscal constraints as a structural factor influencing the potential for responsiveness. Why would fiscal constraints have an effect on political responsiveness?

As the literature on ‘permanent austerity’ (Pierson, Reference Pierson1998) argues, fiscal pressure has steadily increased over the last decades, due to the structural pressures emanating from demographic change and globalization.Footnote 5 In this account, the ageing of societies and the resulting demands on the welfare state have created a permanent upward pressure on the expenditure side of developed democracies’ budgets. At the same time, their capacity to tax has become restricted by the increased mobility of capital and high‐skilled labour and by growing tax resistance among large parts of their populations (Genschel & Schwarz, Reference Genschel, Schwarz, Schäfer and Streeck2013). These processes have been captured by the idea that developed democracies experience a decline of ‘fiscal democracy’ (Steuerle, Reference Steuerle2014; Streeck & Mertens, Reference Streeck and Mertens2010).

According to this literature, structural budgetary pressures have caused a steady increase in the share of public budgets used for mandatory spending (which is removed from political decision making), whereas the share of discretionary spending (which is available for political decision making) has declined. This development restrains fiscal democracy, since the potential impact of elections declines if elected politicians can only re‐allocate ever‐smaller portions of the budget. Hence, it also restricts politicians’ capacity to respond to public demands (Schäfer & Streeck, Reference Schäfer and Streeck2013).

Underlying these accounts is the assumption that proposals for increasing public expenditure or lowering the tax burden should generally be popular and allow for a policy of credit claiming (Weaver, Reference Weaver1986). Contractionary policies, such as spending cuts or tax increases, by contrast, are usually highly unpopular, as the literature on the electoral effects of austerity policies demonstrates (Fetzer, Reference Fetzer2019; Talving, Reference Talving2017).

Recent public opinion research further supports this line of reasoning. When confronted with budgetary trade‐offs, citizens strongly dislike cuts in government spending and tax increases (except for top income taxes), while they care less about public debt (Bremer & Bürgisser, Reference Bremer and Bürgisser2021). Enacting contractionary policies to reduce deficits is thus often considered as a form of responsiveness towards markets instead of citizens (Streeck, Reference Streeck2014). Similar trade‐offs can be observed with regard to different types of social spending. When governments face fiscal pressure, they might be forced to finance a popular expansion by imposing unpopular cutbacks. As recent research on welfare state preferences shows, while support for new policy initiatives in the field of social investment (e.g., spending on education or childcare) is generally high, citizens are not willing to accept cutbacks in traditional social insurance programs in order to finance them (Busemeyer & Garritzmann, Reference Busemeyer and Garritzmann2017; Neimanns et al., Reference Neimanns, Busemeyer and Garritzmann2018).Footnote 6

Summing up, the literature on the effects of permanent austerity suggests that fiscal pressure may indeed be an important constraint on policy responsiveness, since it restrains the fiscal space that is available for policy initiatives. When fiscal space declines, this will either directly prevent (likely popular) new policy initiatives or necessitate (unpopular) cuts/revenue increases in other areas in order to free up fiscal space for new policy initiatives. Such cuts may become particularly pressing when policymakers anticipate (but not necessarily experience) a loss of trust in financial markets and, thus, a further escalation of the interest burden. If fiscal space increases by contrast, that is, if resources become available which have not yet been allocated to specific purposes, this allows governments to pursue an increasing number of new initiatives. Hence, governments will find it much easier to be responsive to citizens’ preferences when structural fiscal pressure is low than when it is high.

Based on the literature on permanent austerity, we thus emphasize the role of structural constraints for political responsiveness. In contrast to this literature, however, we do not draw a direct link from budgetary pressures to societal outcomes but analyze the level of political decision‐making. Specifically, we derive our hypotheses on the level of decisions on individual policies. In doing so, we focus on policies with fiscal consequences. These are policies that either affect the level of government expenditure or of government revenue. After all, it is unlikely that policies without fiscal consequences are affected by changes in fiscal pressure. Our first hypothesis is that changes in fiscal pressure are an important mechanism behind changes in policy responsiveness with regard to these policies.

H1: The effect of public support for a fiscal policy proposal on the likelihood of policy adoption is weaker [stronger], when fiscal pressure is high [low].

However, the effect of fiscal pressure may not be the same for all types of government but rather depend on the ideology of the government coalition. The classical literature on partisanship leads us to expect that left‐wing governments are more restrained by fiscal pressure. First, these governments would usually aim to pursue expansionary fiscal policies, in particular through generous public spending on social protection and the avoidance of welfare retrenchment (Allan & Scruggs, Reference Allan and Scruggs2004; Korpi & Palme, Reference Korpi and Palme2003). The Right, by contrast, may pursue some of these contractionary policies for ideological reasons, even in the absence of fiscal constraints. Second, and more importantly, right and conservative parties are usually considered to be the issue owner of ‘sound public finances’, which means that left‐wing governments are in stronger need to signal fiscal competence to compensate for their bad fiscal reputation, in particular when deficits are politically salient (Barta & Johnston, Reference Barta and Johnston2018; Kraft, Reference Kraft2017). High fiscal pressure may thus be a heavier constraint on the Left's political room for manoeuvre and may thus illicit stronger reactions in terms of contractionary policies from left‐wing governments. In other words, the difference between fiscal policies in a low‐pressure context and a high‐pressure context should be bigger for left governments than for right governments. If the reaction to a deficit reduces responsiveness (as posited in H1), and if this reaction is bigger for left parties, the reduction in responsiveness should thus also be bigger.

H2: The effect of public support for a fiscal policy proposal on the likelihood of policy adoption is reduced more strongly by fiscal pressure under left‐wing governments than under right‐wing governments.

While these hypotheses concern responsiveness towards the general population, we are also interested in its potential inequality towards different social classes. Indeed, there is good reason to believe that fiscal pressure structurally reduces the political capacity to respond to the preferences of the poor more strongly than the capacity to respond to the rich, since the less privileged are more in need of public social protection and a strong fiscal state. Since the lower classes are most dependent on this spending, they will be most fervently opposed to cutting such spending. People with higher income and higher social status can much more easily rely on private markets and do not necessarily need public expenditure. Hence, they will be less opposed to cutting such expenditure. As has been shown by several authors, workers and lower income groups indeed show stronger preferences for re‐distribution and state intervention than the better‐off (Beramendi et al., Reference Beramendi, Häusermann, Kitschelt, Kriesi, Beramendi, Häusermann, Kitschelt and Kriesi2015) – and preference differences become even more pronounced when people are confronted with fiscally induced trade‐offs (Busemeyer & Garritzmann, Reference Busemeyer and Garritzmann2017; Häusermann et al., Reference Häusermann, Pinggera, Ares and Enggist2021). What is more, people with lower incomes and low subjective economic well‐being tend to oppose fiscal consolidation measures more strongly than the better‐off (Hayo & Neumeier, Reference Hayo and Neumeier2017; Stix Reference Stix2013). Following this line of reasoning, fiscal constraints should structurally reduce responsiveness to the poor more strongly than responsiveness to the rich. Accordingly, we hypothesize that

H3: The effect of lower‐class support for a fiscal policy proposal on the likelihood of policy adoption is reduced more strongly by fiscal pressure than the effect of upper class support.

Before we empirically test these hypotheses, we explain our case selection and the structure of our data.

Data and case selection

Case selection: Germany under varying fiscal pressure

We test our hypotheses about the relationship between fiscal pressure and (unequal) responsiveness with the help of the ResPOG dataset (Elässer et al., Reference Elsässer, Hense and Schäfer2021) covering public opinion on policy proposals and information on its implementation in Germany between 1980 and 2016.

Ideally, our empirical case for studying the effects of fiscal pressure on political responsiveness should have experienced substantial variation in fiscal pressure over the period of investigation. At the same time, this pressure should not have reached the level of a dramatic crisis, which could have fundamentally transformed the public's attitudes toward fiscal policies. Otherwise, there would be a risk that budgetary pressures would not just be a constraint on policymakers but would directly affect people's fiscal preferences.

Germany fits this description very well. While the country never had to impose acute austerity measures at the behest of financial markets, it experienced wildly different levels of structural fiscal pressure. This pressure was intense enough to require tough budgetary trade‐offs, but never reached the level of a dramatic crisis.

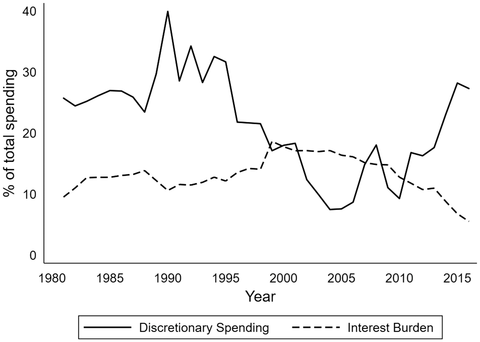

Using the interest burden as our main indicator of fiscal pressure, we can roughly distinguish three periods with different degrees of fiscal pressure. These periods lasted from 1980 to about 1989, from about 1990 to about 2005 and from about 2006 to 2020. This periodization is also supported by the share of discretionary spending, which captures the fiscal room that is available for new policy initiatives.

Before reunification, Germany experienced intermediate, but slowly increasing levels of pressure (Figure 1, dashed line). Since interest rates were very high, the interest burden crept up from about 10 per cent of federal spending in 1980 to about 15 per cent in 1989. The government thus had still some room for new policy initiatives, but considerably less than in the 1960s and 1970s.

Figure 1. Indicators of German public finances, 1980–2016. Notes: Source for interest burden: IMF. Source for discretionary spending: Own calculation based on Streeck and Mertens (Reference Streeck and Mertens2010).

After reunification, fiscal pressures increased quickly and heavily for about 15 years. The costs of integrating the Eastern states into the West German economy and its welfare state imposed a huge burden on public budgets (Zohlnhöfer, Reference Zohlnhöfer2001). Despite steep increases of tax rates and social security contributions, the fiscal costs of reunification let the interest burden increase to almost 20 per cent of federal expenditure. When these problems were exacerbated by an expensive tax reform and the fallout of the new economy bubble, Germany became the first Euro member to breach the 3 per cent deficit criterion of the Stability and Growth Pact in 2003. In this period, the share of discretionary spending in the budget declined from around 30 per cent to less than 10 per cent (Figure 1, solid line), signalling strong pressures on fiscal democracy. Thus, this period was characterized by high and increasing fiscal pressure and governments had hardly any room left for new policy initiatives. Moreover, political discourse about the public finances also turned sharply towards fiscal conservatism, a turn that culminated in the introduction of a ‘debt brake’, a constitutional limit on public deficits, in 2009 (Haffert, Reference Haffert2016, p. 40–42).

Interestingly, the turnaround of German public finances already began before the introduction of this constitutional rule. In particular, the effect of the great recession on public finance was quite ambivalent. While the financial crisis first caused a substantial increase of public debt in 2009 and 2010, the super‐low interest rates still reduced the interest burden. Consequently, the interest burden has consistently been declining since the mid‐2000s and Germany has even been running budget surpluses between 2014 and 2019. Thus, this final period was characterized by a declining level of fiscal pressure, which allowed governments to pursue new policy initiatives without having to impose cuts on existing programs.

Taken together, the level of fiscal pressure in Germany fluctuated quite substantially over our period of analysis. This allows us to analyze whether the level and inequality of responsiveness indeed vary with the strength of fiscal pressure. Moreover, there is also substantial variation in the partisanship of governments. After the end of the Social‐Liberal coalition in 1982, Germany was governed by a centre‐right coalition of Christian Democrats and Liberals throughout the 1980s and during the period of increasing fiscal pressure in the 1990s. During the peak years of fiscal pressure around the turn of the century, the country had a centre‐left government of Social Democrats and Greens (1998–2005). Finally, during the period of declining fiscal pressure after 2005, there were both centre‐right governments (2009–2013), and so‐called ‘grand coalitions’ of Christian Democrats and Social Democrats (2005–2009, 2013–2021). Thus, both the Left and the Right were involved in governments that faced high or low levels of fiscal pressure, even if the Left never controlled a government under fiscally favourable circumstances.

Data

The ResPOG database used for our analyses includes information on public opinion and respective policy decisions for 823 federal policy proposals between 1980 and 2016, derived from two major German representative surveys, the Politbarometer and DeutschlandTrend (see Elsässer et al., Reference Elsässer, Hense and Schäfer2020 for a detailed description of the dataset). The former covers the period from 1980 to 2016 and the latter from 1998 to 2016 (Table A‐1 in the online Appendix shows the number of policy proposals per year in the dataset). Survey questions usually deal with political decisions that were high on the political agenda at the time or that are of general public interest. Issues were thus salient enough that we can reasonably expect the public to hold preferences on them, which is an important criterion for assessing responsiveness to public opinion (Gilens, Reference Gilens2012, p. 50–53). At the same time, this high salience makes it relatively more likely that policy will respond to public opinion on these issues. If we also had data on low salience issues, we might find even weaker responsiveness to public opinion.

The questions included in the data ask about respondents’ agreement with a specific policy proposal. Since the proposals formulate potential policy changes, they allow for analyzing whether policymakers respond to public opinion, thus capturing responsiveness rather than congruence. In this way, we can also capture responsive behaviour in cases of non‐action: If the public prefers the status quo to a policy change, policymakers are responsive if they do not adopt a certain proposal. Finally, the proposals cover a wide array of topics from different policy fields, ranging from the introduction of a minimum wage or cuts in pension benefits, to the use of nuclear energy or changes in child adoption laws.Footnote 7

For each policy proposal, we coded whether the policy would affect the public budget (e.g., tax reforms, pension reforms, disaster relief) or not (e.g., same‐sex marriage, foreign policy, regulatory policies). All questions were separately coded by the two authors.Footnote 8 In total, 442 proposals had a potential budgetary effect, whereas 370 proposals were coded as non‐budgetary.Footnote 9 This underlines the potential importance of fiscal constraints for a full understanding of political responsiveness. The 442 budget‐related proposals form the basis of our core analyses. Fifty‐nine per cent of these proposals were adopted within the 2‐year period after the survey question was asked.

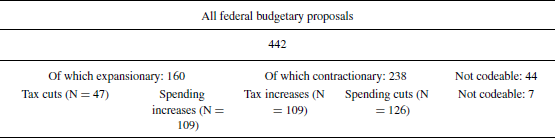

In addition, we coded all budgetary proposals on whether they concern the revenue side or the expenditure side of the budget, and whether they aim for a contraction or an expansion of the role of government. Based on this coding, four types of policies can be distinguished: spending increases, tax cuts, spending cuts and tax increases (see Table 1). Both spending increases and tax cuts are costly for the state and are thus expansionary policies which reduce fiscal space as defined in the theory section. Spending cuts and tax increases, by contrast, serve the aim of reducing fiscal pressure and are thus coded as contractionary. Importantly, ‘tax cuts’ and ‘tax increases’ not just include taxes in the narrow sense of the word, but also other types of public revenues, such as increases in social security contributions.

Table 1. Number of budget‐related proposals

There is a clear majority of contractionary proposals: 60 per cent of those policies that we can code on the expansion–contraction dimension propose spending cuts or tax increases.Footnote 10 While contractionary proposals are roughly equally balanced between expenditure – (54 per cent) and revenue‐related (46 per cent) measures, spending proposals (70 per cent) clearly outweigh tax‐related proposals (30 per cent) among the expansionary proposals.

To allow a systematic analysis of the link between public preferences and political decisions, the database contains information on whether the specific policy proposal was enacted within 2 years after the question was asked in the survey. This information was obtained by researching legislative documents from the German Federal Legislative online archive,Footnote 11 newspaper articles and an academic web archive on social policy legislation in Germany.Footnote 12 Using this variable, we can thus evaluate political responsiveness by comparing the decision on the policy proposal over this 2‐year period with the preferences expressed in the respective survey.

To evaluate political responsiveness towards different social classes, we use the share of support within different occupational groups for each policy proposal. These support shares are the main independent variables of our analyses. We believe that occupational groups are best suited for our analysis, since political preferences are strongly influenced by an individual's position in the labour market (Häusermann & Kriesi, Reference Häusermann, Kriesi, Beramendi, Häusermann, Kitschelt and Kriesi2015; Kitschelt & Rehm, Reference Kitschelt and Rehm2014). As has been shown repeatedly, workplace experiences and its related political socialization processes play an important role in the formation of preferences, which cannot be captured equally well by other measures such as income or education (Carnes, Reference Carnes2013; Kitschelt & Rehm, Reference Kitschelt and Rehm2014; Manza & Brooks, Reference Manza, Brooks, Lareau and Conley2010). Based on the class schemes developed by Erikson and Goldthorpe (Reference Erikson and Goldthorpe1993) and Oesch (Reference Oesch2006), the database contains information on policy support in six different occupational groups: Unskilled workers, skilled workers, lower‐grade employees, higher‐grade employees, civil servants and business owners. We deviate from the Erikson–Goldthorpe scheme by treating civil servants as a separate category, since their employment relations are distinct in terms of social security benefits and duration of contract. Both civil servants and business owners are treated as the ‘highest’ social classes in the dataset. Unfortunately, the differences between occupational groups are not always as sharp as one would hope. For example, business owners include both large‐scale entrepreneurs and individuals in a precarious labour market position, such as freelancing journalists. Despite this heterogeneity, however, the highest occupational groups are also those with the highest average incomes (Statistisches Bundesamt, 2015), thus capturing vertical social stratification.

In line with theoretical expectations, occupational status and political preferences are meaningfully related in the data. Average disagreement over policy proposals grows with the social distance between occupational groups and is higher on proposals with a potential impact on public finances than on those without budgetary implications. In addition, average opinion differences between lower and higher social classes are higher on proposals concerning contractionary measures than on those proposing a fiscal expansion (see Figures A‐1 and A‐2 in the online Appendix).

Fiscal pressure has been operationalized differently in the literature. One important measurement challenge is its endogeneity to political decisions. Measures like the budget deficit and discretionary spending are clearly endogenous to the policy decisions we study. This is less problematic for the interest burden. After all, in relatively highly indebted countries (like Germany in the period under investigation), changes in the interest burden are mainly driven by changes in the interest rate on the existing debt (of which a substantial share needs to be refinanced every year), and less by changes in the budget deficit. The interest burden is thus relatively (though not fully) exogenous to the policy decisions that we study. Moreover, interest payments are the most mandatory type of public spending, since refusing to pay them would mean a government default. Following other studies (Breunig & Busemeyer, Reference Breunig and Busemeyer2011) we thus use the change in the interest burden as our preferred measure of fiscal pressure. We use the change since it best captures whether fiscal space for new policy is freed up (because mandatory expenditure declines) or whether fiscal space declines (because mandatory expenditure increases). It is this change in fiscal space which determines whether governments are in a position to enact new policy proposals. More concretely, we average the change in the interest burden in the survey year and the year thereafter, thus capturing the period in which the policy proposals are decided upon. Since we study policy responsiveness on the federal level, we use interest payments of the federal government.

Results

General responsiveness

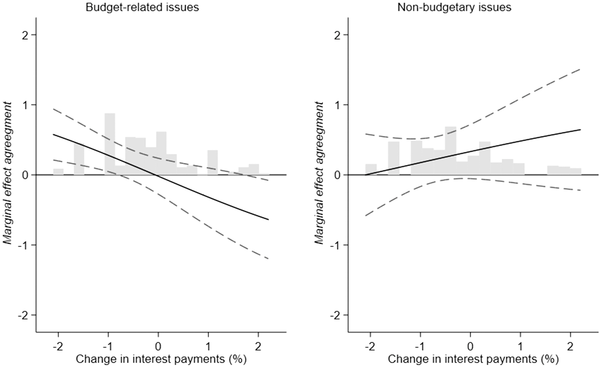

We now use this data to study the development of policy responsiveness in Germany and its relationship to fiscal pressures since 1980. Our first hypothesis was that levels of political responsiveness vary with the degree of fiscal pressure. More specifically, we expect responsiveness on budget‐related proposals to decrease when the fiscal room for manoeuvre is shrinking. To test this hypothesis, we estimate a logistic regression in which we regress the policy output (proposal adopted or not within 2 years) on the average support for the proposal, the change in the interest burden over the relevant period and an interaction between the two. Including the interaction allows us to estimate the effect of public opinion on policy change at different degrees of fiscal pressure. Since we want to estimate the effect of fiscal pressure on policies affecting the budget, only budget‐related proposals are included in the regression (N = 442). We cluster standard errors by year.Footnote 13

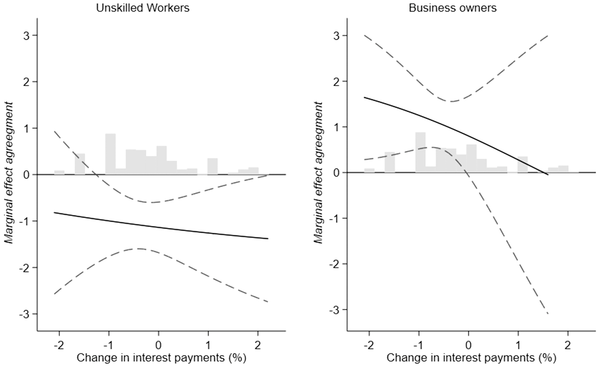

The left panel of Figure 2 shows the main result of our analysis: The share of agreement in the population is positively related to the likelihood that a policy proposal is adopted when fiscal pressure is low. However, it is negatively related to policy change when fiscal pressure is high. Thus, in periods of high fiscal pressure, the more popular a policy is, the less likely it is to be adopted. This pattern is in line with our first hypothesis and provides strong evidence for the importance of the structural context for policy responsiveness. Resonating with the arguments about declining fiscal democracy, governments are only able to respond to public demands if the fiscal conditions leave room for policy choice. The effect of fiscal pressure is quite substantial. In a year in which the interest burden decreases by 1 percentage point, a policy that has 60 per cent support in the population is 6 percentage points more likely to be adopted than a policy that has only 40 per cent support. In a year in which the interest burden increases by 1 percentage point, by contrast, the same policy has a 6‐percentage point lower chance of being implemented than the less popular policy.

Figure 2. Marginal effect of public opinion on policy change at different degrees of fiscal pressure. Note: Full regression results are displayed in Table A‐2 in the online Appendix.

In order to check for the robustness of this finding, we carry out a number of further analyses. First, since fiscal pressure should only affect policy decisions that have an impact on the public budget, we should not see similar effects of fiscal pressure on responsiveness regarding non‐budgetary policies. To test this, we ran the same model as above for all non‐budgetary proposals (N = 370).

As expected, there is no systematic relation between the change in the interest burden and policy responsiveness on these issues (see right panel of Figure 2). If anything, non‐budgetary policymaking becomes more responsive when fiscal pressure is high, which could suggest that policymakers seek to compensate for the lack of budgetary responsiveness by becoming more responsive on other issues. However, we refrain from putting too much weight on this possibility, since the relationship is not statistically significant. In any case, these results validate our coding of policy proposals as budgetary or non‐budgetary.

Second, we examine whether our results are driven by the types of proposals asked at different levels of fiscal pressure. After all, the types of proposals that are publicly and politically discussed, and thus make it to the agenda of the survey institutes, may systematically change over time (Barabas, Reference Barabas2016). In particular, there may be more contractionary proposals in times of high fiscal pressure.

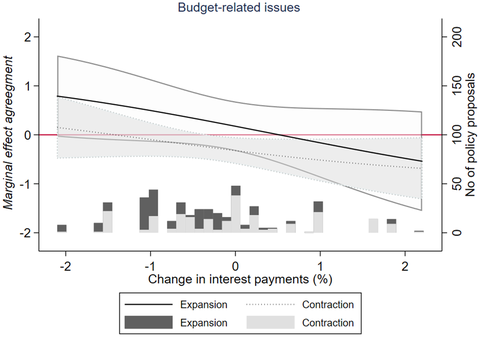

If policy decisions were generally more responsive with regard to expansionary proposals than with regard to contractionary proposals, the effect of fiscal pressure could thus be driven by compositional effects. To test for this possibility, we extend our logistic regression model by including a triple interaction. We regress the policy output (proposal adopted or not) on the average agreement to the proposal, whether the proposed policy was contractionary or expansionary and the level of fiscal pressure, and interact the three explanatory variables with each other. Including this interaction allows us to estimate whether fiscal pressure moderates the effect of public opinion on policy choices separately for different types of proposals.

Figure 3 shows the marginal effect of public opinion at various levels of fiscal pressure, both for contractionary and expansionary proposals. The underlying histogram gives a sense of the share of proposals related to fiscal expansion (fiscal contraction) that were asked about at different levels of budgetary pressure.Footnote 14 Three points are worth noting. First, it is indeed the case that proposals related to expansionary measures were predominantly discussed when fiscal pressure was decreasing. Conversely, contractionary proposals are dominating when the fiscal room for manoeuvre is shrinking. Second, responsiveness towards expansionary proposals is consistently higher across all levels of fiscal pressure. At first sight, these findings could strengthen the point that the lower responsiveness under high fiscal pressure is caused by the types of proposals that make it to the agenda. As the figure also shows, however, responsiveness declines with growing fiscal pressure for both types of proposals. Hence, our finding is not caused by the composition of the available survey questions alone. Instead, fiscal pressure generally reduces policy responsiveness when decisions have budgetary implications.

Figure 3. Marginal effect of public opinion on policy change for contractionary and expansionary policies, depending on fiscal pressure. Note: Full regression results are displayed in Table A‐3 in the online Appendix. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Nevertheless, these results suggest that growing fiscal pressure affects the political process at different stages, influencing not only the decision making but also the agenda setting process. This is suggested by the higher share of contractionary proposals in times of fiscal pressure and seems plausible, given that changing fiscal conditions likely affect the perceptions of what initiatives are politically feasible. That said, the pool of survey questions is not necessarily equal to the programmatic agenda of political parties or representative of all bills in parliament (Barabas, Reference Barabas2016). Gaining a better understanding of this ‘agenda effect’, however, goes beyond the scope of this article, but points to a promising avenue for future research.

In a next step, we investigate the effect of partisanship. Since we are interested in whether fiscal pressure affects the policy responsiveness of different governments differently, we cannot simply add a partisanship measure to the regression. Instead, we again use the triple interaction setup and interact government partisanship with fiscal pressure and public preferences. We measure government partisanship by using the left cabinet share as provided by Armingeon et al. (Reference Armingeon, Wenger, Wiedemeier, Isler, Knöpfel, Weisstanner and Engler2020). Again, we average this share over the survey year and the year afterwards.

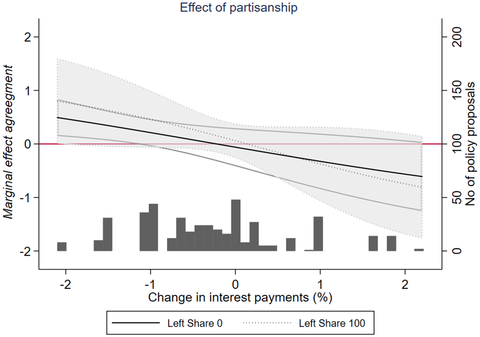

Figure 4 shows the estimated effect of fiscal pressure for a pure left (SPD‐Green) and a pure right (CDU‐FDP) government. As the graph shows, even for a right‐of‐centre government, fiscal pressure significantly constrains the level of responsiveness. Right‐wing governments are responsive to public opinion when fiscal pressure decreases, but not when it is constant or increases. The same relationship is slightly more pronounced for left‐wing governments, but the difference between different government types is not statistically significant. We thus cannot reject the null of hypothesis 2.

Figure 4. Marginal effect of public opinion on policy change for left and right governments, depending on fiscal pressure. Note: Full regression results are displayed in Table A‐4 in the online Appendix. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

However, we should emphasize that the triple interaction asks a lot from the data, given the natural constraints on the partisanship measure. Effectively, there are only three government types in the dataset: SPD‐Green, CDU‐FDP and the ‘grand coalition’.Footnote 15 Accordingly, these results are strongly influenced by individual years or even individual questions. In the online Appendix, we show that by removing just the single most influential question, we obtain a marginally significant effect for left partisanship. Hence, we are careful not to overinterpret these findings. While we cannot really say whether the Left is more constrained by fiscal pressure than the Right, we can confirm that even the Right becomes less responsive when fiscal pressure increases.

Responsiveness to different social groups

So far, we have demonstrated that responsiveness on fiscal issues is systematically related to the level of fiscal pressure, and that this relationship is moderated by what kind of fiscal policy proposals make it to the agenda. However, we are not just interested in responsiveness towards the average public opinion, but also in its potential inequality towards different social groups. Above, we hypothesized that responsiveness would also be unequal regarding fiscal issues and that this inequality would be particularly high if fiscal pressure was intense.

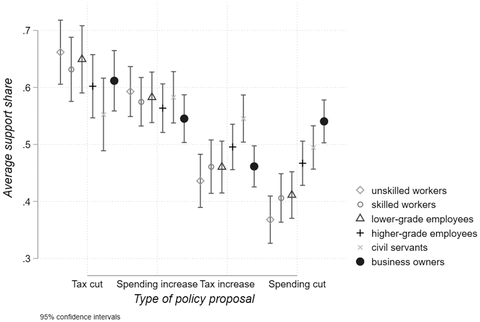

For responsiveness to be unequal, preferences of different social groups need to differ. As we have elaborated above, preferences gaps are generally bigger on budgetary issues than on non‐budgetary issues. Moreover, there are also substantial opinion differences within the group of budgetary policies, as Figure 5 shows. This figure displays, for the different occupational groups, the average share of agreement to our four types of budgetary proposals: tax cuts, spending increases, tax increases and spending cuts. Two points deserve particular attention. First, and as expected from the theoretical argument, expansionary policies (tax cuts and spending increases) are generally more popular than contractionary policies and are supported by a majority within all occupational groups. Differences between the occupational groups are thus mainly differences in the intensity of support.

Figure 5. Average agreement to different types of policy proposals, by occupational group.

The pattern is, second, very different for contractionary policies. While lower occupational groups (skilled and unskilled workers, lower‐grade employees) generally oppose these policies, higher occupational groups sometimes support them. Indeed, of all four policy types, gaps in support between lower and higher occupational groups are largest when spending cuts are concerned. Whereas spending cuts are mostly rejected by the working class, they will often be in line with the preferences of business owners. Tax increases, on the other hand, are most strongly supported by civil servants, but opinion differences among all other occupational groups are relatively small.Footnote 16

Taken together, this preference pattern suggests that analyzing inequality in responsiveness requires particular attention to contractionary proposals, and in particular spending cuts, since disagreement is highest in these policy areas.

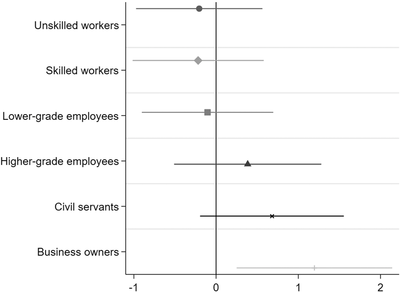

To test whether responsiveness is indeed unequal, and whether this inequality is moderated by fiscal pressure, we repeat the logit regression once more but do not use aggregate support among all citizens but group‐specific support for a proposal as independent variable. Figure 6 presents the results. As the figure demonstrates, responsiveness on fiscal issues is indeed highly unequal: While the preferences of business owners significantly affect fiscal policy choices, and the effect for civil servants only narrowly misses significance, there is no such effect for the preferences of the working class or low‐skilled service class members. The familiar finding of unequal responsiveness thus also holds for fiscal policy issues.

Figure 6. Marginal effects of public support for reform proposals on reform implementation, by occupational group. Note: Full regression results: Table A‐5 in the online Appendix.

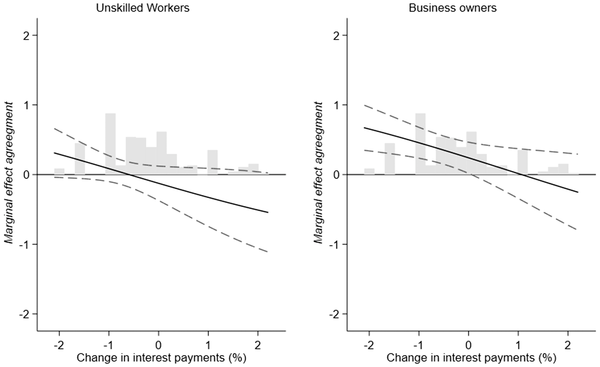

But does representational inequality depend on the fiscal situation? To test this, we again interact group specific rates of agreement with the change in the interest burden. Figure 7 presents the results for two exemplary occupational groups who stand for the lowest and highest social class in our data: workers and business owners (see Table A‐6 in the online Appendix for the full regression results for all occupational groups). As the figure shows, responsiveness is indeed strongly driven by the degree of fiscal pressure, but increasing fiscal pressure reduces fiscal responsiveness for all social groups. In fact, when fiscal pressure is very high, policy is not responsive to any social group anymore.

Figure 7. Public opinion and policy change depending on fiscal pressure, occupational groups. Note: Full regression results: Table A‐6 in the online Appendix.

This does not mean that the economic context has no consequences for representational inequality. For business owners (and civil servants, not shown here), there is a systematic positive relationship between their preferences and policy decisions when fiscal pressure is low, but this vanishes when the interest burden increases. Responsiveness towards workers also becomes significantly worse when fiscal pressure increases, but even in the fiscally most permissive times, the relationship between their preferences and policy decisions is not significantly different from zero (the same holds for other lower occupational groups). Contrary to what we expected, inequality is thus most pronounced when fiscal pressure is low, not when it is high.

To better understand this surprising pattern, we restricted our analysis to policy proposals that workers and business owners disagree upon. Figure 8 shows the results of logit regressions that include only cases in which one group favoured the proposal (support > 50 per cent), whereas the other group opposed it (support < 50 per cent). Due to the lower number of cases (N = 101), we must interpret the results with some caution. However, they seem to strengthen our previous findings. There is no – or even a negative – relationship between workers’ political demands and policy change, independent of the fiscal situation. The relationship for business owners, by contrast, is positive under conditions of low fiscal pressure.Footnote 17

Figure 8. Public opinion and policy change depending on fiscal pressure, including only contested proposals. Note: Full regression results: Table A‐8 in the online Appendix.

Moreover, this analysis also makes clear why the overall degree of responsiveness towards lower social groups varies with the degree of fiscal pressure. As the figure demonstrates, policy is always unresponsive to the lower classes when social groups disagree, even in the fiscally most permissive circumstances. The negative relationship between fiscal pressure and responsiveness in Figure 7 is thus entirely driven by proposals on which workers and the affluent agree. In other words: lower social groups sometimes experience a form of ‘coincidental’ representation under conditions of low fiscal pressure, when a policy that is responsive to the preferences of the affluent is also in their interest.

Taken together, these findings show that the budgetary situation of the state has an important role for understanding processes of (unequal) representation. Somewhat differently from what we had expected, though, fiscal pressures do not increase the inequality of responsiveness. Instead, increasing fiscal pressure seems to be such a powerful constraint on policy responsiveness that no occupational group has a systematic influence on policy choices. Differences between groups mainly occur when fiscal pressure recedes. Upper social groups seem to be able to profit from lower fiscal pressure. Lower social classes, by contrast, remain without influence on policy choices.

The finding that representational inequality mainly occurs under permissive fiscal conditions, however, does not necessarily mean that the social consequences of contractionary policies are the same across social groups. After all, there is good reason to believe that contractionary policies – in particular spending cuts – hit those groups hardest who depend most strongly on an interventionist state. This is also suggested by our data, since the majority of the proposals dealing with spending cuts concern social security programs such as old age pensions. Thus, while responsiveness as such may not be more unequal when fiscal pressure is high, the perceptible consequences of unequal responsiveness may even be worse.

One potential concern for our findings could be that people's preferences might be endogenous to changes in fiscal pressure. This would be particularly problematic if disagreement between social groups systematically increased or decreased with varying fiscal pressure. Häusermann et al. (Reference Häusermann, Enggist, Ares and Pinggera2019) argue, for example, that support for welfare retrenchment increases among more privileged social classes when they perceive fiscal pressure to be high. This could affect the interpretation of our results, since greater inequality in the responsiveness of policy decisions can either occur because policy becomes less responsive to some groups, or because preference gaps become bigger.Footnote 18

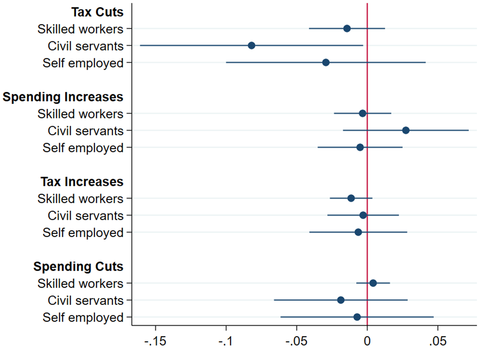

In order to test whether political disagreement systematically changes with the budgetary situation, we analyzed preference gaps between different occupational groups. Figure 9 shows the coefficients of 12 regressions that each regress the preference gap between unskilled workers and the respective occupational group on our measure of fiscal pressure, separated by policy type. For ease of presentation, we include those groups with the biggest preference gaps and leave out the two middle groups. Positive (negative) coefficients mean that the preference gap increases (decreases) when fiscal pressure increases. As the figure shows, the size of the preference gap does not significantly vary in almost all cases. The only exception is civil servants’ and unskilled workers’ attitudinal gaps towards tax cuts, but this may be simply an artifact of the low number of observations for this policy type (n = 47).

Figure 9. Effect of fiscal pressure on preference gaps between workers and other occupational groups, four different policy types. Note: Full regression results: Table A‐10 and A‐11 in the online Appendix. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Based on this analysis, we conclude that our findings are unlikely to be driven by the endogeneity of preferences to fiscal pressure. If policy becomes more responsive towards the upper classes when fiscal pressure declines, this is not because the preferences of these classes become more distinct from the preferences of other groups. Instead, the way that newly available fiscal resources are being used seems to correspond to the preferences that these groups already have.

Discussion

In this paper, we have studied the relationships between pressures for fiscal austerity and political responsiveness. We have argued that fiscal pressure is an important constraint on responsiveness in many advanced democracies. Moreover, we have analyzed to what extent fiscal pressure drives inequality in responsiveness towards different social groups.

Our analysis of German politics between 1980 and 2016 has generated substantial evidence that fiscal pressure indeed reduces policy responsiveness. Specifically, the Bundestag has been much less responsive regarding budgetary proposals in periods when fiscal pressure increased than in periods when it decreased. Whereas German policy was almost completely unresponsive on the fiscal dimension in the period of high fiscal pressure until about 2005, responsiveness seems to have recovered since then. Moreover, fiscal pressure seems to constrain the responsiveness of both left‐of‐centre and right‐of‐centre governments.

While fiscal pressure is thus clearly related to the general level of policy responsiveness, the evidence with regard to inequality of responsiveness is more mixed. While budgetary proposals, and contractionary measures in particular, generate big disagreement between different occupational groups, we did not find that inequality of responsiveness systematically increased when fiscal pressure went up. In fact, responsiveness decreases for all groups when the fiscal room for manoeuvre is shrinking – in the years with the highest fiscal pressure, German budgetary policy was non‐responsive towards all social groups. In years with a more permissive fiscal environment, by contrast, we see a clear gap in responsiveness. In these periods, German public policy was much more responsive to the preferences of the upper classes than to the preferences of the lower classes.

This pattern suggests that improving the budgetary situation of the state will not necessarily reduce inequalities in political representation as might be expected based on a ‘progressive consolidation view’ (Haffert & Mehrtens, Reference Haffert and Mehrtens2015). To the contrary, it seems that the use of new‐won fiscal space corresponded more closely to the preferences of the upper social groups.

At the same time, the fact that policy was unresponsive towards all social groups during periods of maximum fiscal pressure does not mean that all social groups were equally affected by the policy measures enacted. Since different types of policy proposals are being discussed in times of high fiscal pressure, unequal responsiveness has different policy implications in this context. Budgetary policy during periods of high fiscal pressure mainly consisted of contractionary measures, and in particular spending cuts. Lower social classes did not only oppose these policies more strongly than the more privileged social classes, but there is good reason to believe that they were also disproportionately hit by them. This is especially true for retrenchment in social security programs, such as old age pensions or unemployment benefits.

Our findings contribute to the literature on policy responsiveness by highlighting how structural economic constraints can affect responsiveness, independently of political actors or institutions. Moreover, we offer an important addition to the literature on the political effects of austerity by studying the specific policy measures that link fiscal pressures and societal outcomes. This raises an interesting new question for this literature. If it finds that voters punish incumbents electorally for the negative effects of austerity, is this punishment only triggered by the societal outcomes or perhaps also by the lack of responsiveness, independently of the outcome?

An obvious limitation of our analysis is that we have only studied a single country. This makes it difficult to evaluate whether we can generalize our findings to other rich economies. At the same time, there are at least two reasons why our findings are relevant to other countries as well. First, Germany has never been subjected to financial market pressure, one of the most important channels through which fiscal pressure may affect political responsiveness. If we do find such an effect in Germany, we are likely to find even stronger effects in market‐pressured countries like Spain or Greece. Second, the German political system has a number of powerful veto players that tend to induce a status quo bias. Hence, the adoption of both unpopular contractionary and popular expansionary measures should be less likely than in other countries. If fiscal pressure induces variation in responsiveness under these constraints, it should have even stronger effects in a less institutionally constrained environment. Nevertheless, similar studies beyond the German context could further advance our understanding of the link between fiscal pressure and political responsiveness in contemporary democracies.

Acknowledgements

Earlier versions of this paper have been presented at the Meeting of the German Political Science Association in Frankfurt in 2018, at the ‘Unequal Democracies’ workshop in Geneva in June 2019 and at the ‘Unequal representation and its underlying mechanisms’ workshop in Amsterdam in November 2019. We thank all participants of these workshops for constructive feedback. In addition, we would like to thank Björn Bremer, Svenja Hense, Armin Schäfer and the two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments.

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Supplement Material

Supplement Material