Introduction

On May 29, 2022, in the Louvre Museum in Paris, a 36-year-old man, dressed as an old woman in a wheelchair, smashed a pie against the Mona Lisa portrait as an act of protest against the institutional inertia vis-à-vis the climate crisis. It soon proved not to be an isolated case, but rather the beginning of a series of similar actions echoing that act of protest, as activists in several other countries targeted mostly famous artworks in popular and crowded museums or squares (Kinyon, Dolšak and Prakash, Reference Kinyon, Dolšak and Prakash2023), aiming to draw attention to the climate crisis. As a reaction, besides becoming a target of the authorities, who issued harsh legislation to penalize their actions (see e.g. Visconti, Reference Visconti2024 for the case of Italy), those activists inevitably grabbed the notice of public opinion and the media on the way. They became liable to the criticism of the many bystanders who did not appreciate the act of targeting valuable pieces of art, and faced widespread criticism in global media, which often portrayed them as vandals staging blitzes in museums, and their actions as counterproductive to the environmental cause (López and Davis, Reference López and Colin2024).

A few years into the new wave of climate protests, this study addresses the question: How does the public react to a controversial climate protest tactic targeting cultural heritage? Specifically, it investigates whether such actions are truly generating more criticism than support among the public and whether this backlash negatively affects citizens’ environmental concern and willingness to engage in pro-environmental behaviors. Existing research suggests that the primary target of these protests is no longer the public, but governments, with activists aiming to pressure policymakers to follow scientific recommendations and take urgent climate action (De Moor et al., Reference De Moor, Michiel, Katrin and Wahlström2021; Zamponi et al., Reference Zamponi, Ferro and Cugnata2024). Indeed, due to government short-termism, these institutions often fail to implement long-term policies on climate change (Improta and Mannoni, Reference Improta and Mannoni2024). As a result, activists resort to direct action against governments, aiming to pressure decision-makers into overcoming short-term incentives and committing to long-term environmental policies. However, even though public opinion is not their main target of interest, popular approval is nevertheless a relevant asset for protesters (Lipsky, Reference Lipsky1968; Giugni, Reference Giugni1998; Wouters, Reference Wouters2019), and the success or failure of protests may primarily depend on their impact on public opinion (Thomas and Louis, Reference Thomas and Louis2014). When backed by a sympathetic public, protesters stand higher chances to bring forward the desired policy change as public opinion might amplify their demands and exert further pressure on the legislators (Agnone, Reference Agnone2007). Even from a psychological perspective, shared grievances enhance perceived collective efficacy, which, in turn, keeps the collective action going (van Stekelenburg and Gaidyte, Reference van Stekelenburg, Gaidyte, Huddy, Sears, Levy and Jerit2023). In light of that, this research builds on the assumption that studying how climate protests targeting artwork affect public opinion holds relevance even when the protesters were not primarily aiming to get the public to side with them in the very first place.

Measuring the impact of exposure to those protests on pro-environmental attitudes and behavior is not easy for at least two reasons. First, public opinion on the environment is influenced by many factors (see e.g. Kemmelmeier et al., Reference Kemmelmeier, Krol and Kim2002; McCright, Reference McCright2010; Kvaløy et al., Reference Kvaløy, Finseraas and Listhaug2012; Brough et al., Reference Brough, Wilkie, Ma, Isaac and Gal2016; Vázquez, Reference Vázquez and Lorenzo2020), making it difficult to isolate the impact of art-targeting protests from the rest. Second, measuring pro-environmental behavior is a challenge in itself (Lange and Dewitte, Reference Lange and Dewitte2019). Under the label pro-environmental behavior fall dozens of different possible behaviors. The vast majority is barely observable and can only be measured by asking individuals to report them – which poses serious challenges, in terms of reliability of data, due to social desirability bias (Fisher and Katz, Reference Fisher and Katz2000). Finally, environmental attitudes are also heavily affected by social desirability bias nowadays. In light of that, I conducted a pre-registeredFootnote 1 survey experiment to test whether priming individuals to think about climate protests targeting artwork negatively impacts their pro-environmental attitudes and behavior. As detailed below, instead of asking to self-report pro-environmental behavior, I actually measured it as the choice made by participants within the study to turn down a monetary bonus offered to them to donate it to one of the environmental organizations proposed. By making the protest salient only to the treated group, I could measure whether these demonstrations and the alleged criticism they aroused are potentially detrimental to the cause, as the interpretation of some early public opinion surveys would suggest (Mann, Reference Mann2022).

The experiment mostly revealed null treatment effects: while respondents broadly disapproved of the protest tactics, exposure to the treatment did not significantly alter environmental attitudes, voting intentions, or behavioral choices.

By leveraging two original data collections, this study offers novel insights into the occurrence, perception, and impact of climate protests targeting artwork. It contributes to emerging research on disruptive climate activism by empirically assessing public responses to a highly visible and controversial protest tactic: the targeting of cultural heritage. While media and political discourse often presume a backfire effect, systematic evidence remains scarce. By combining a pre-registered survey experiment with a theoretically informed design, the study advances current debates on the effectiveness and risks of radical protest in shaping public opinion. The findings contribute to research on protest and public opinion, as well as to broader literatures on environmental concern and pro-environmental behavior. They also carry relevance beyond the academic community – especially for those interested in understanding the wider public impact of increasingly frequent acts of climate protest.

Impact of protests on public opinion

Protests have long been recognized as a powerful agent of societal change through their impact on public opinion (Louis, Reference Louis2009). However, it is not always the case that protests manage to be effective in garnering support among the general public. Scholars have documented both instances where protest actions successfully shifted public attitudes (Sawyer and Gampa, Reference Sawyer and Gampa2018) and even voting behavior (Wasow, Reference Wasow2020). Indeed, regarding the climate issue, recent evidence from Germany found an increase in concern about climate change in the aftermath of disruptive climate protests (Brehm and Gruhl, Reference Brehm and Gruhl2024), as well as an increase in electoral support for the Greens in municipalities more exposed to Fridays for Future (FFF) protests (Valentim, Reference Valentim2023). However, the literature also reports how protesters may struggle to engage key sectors of the public, alienating audiences and ultimately failing (Mudrov, Reference Mudrov2021).

Indeed, according to the extant literature, a key factor in determining protesters’ success or failure is the type of protest tactics they employ (Mudrov, Reference Mudrov2021; Shuman et al., Reference Shuman, Goldenberg, Saguy, Halperin and van Zomeren2024). Non-violent tactics, such as peaceful protests or acts of civil disobedience, are generally more likely to elicit attitudinal change (Thomas and Louis, Reference Thomas and Louis2014; Orazani and Leidner, Reference Orazani and Leidner2019; Feinberg et al., Reference Feinberg, Willer and Kovacheff2020). Violent demonstrations, on the other hand, seem to work better than non-violent on policy-related outcomes (Tompkins, Reference Tompkins and Coy2015). However, protests do not occur in a vacuum, but rather in a setting where the media plays a pivotal role. Media coverage can amplify the voice of protesters but often does so in a selective fashion, framing events in ways that shape public perceptions. Violent protests are more likely to attract media attention compared to non-violent protests (Feinberg et al., Reference Feinberg, Willer and Kovacheff2020). That, however, can be detrimental for violent protesters (Baranauskas, Reference Baranauskas2022) as the media tend to depict them as deviant, delegitimizing their actions in the eyes of the general public (McCluskey et al., Reference McCluskey, Stein, Boyle and McLeod2009). On the other hand, non-violent protests, which are more likely to be perceived as legitimate, struggle more to gain high media coverage, significantly limiting their reach. This creates a tension for activists known as the activist's dilemma (Feinberg et al., Reference Feinberg, Willer and Kovacheff2020), wherein the same actions that can guarantee higher visibility and broader reach are also those that are most likely to erode support and alienate the public. Yet, under certain conditions, this same dynamic can yield indirect benefits for the broader movement. The presence of more extreme or disruptive activists may make moderate actors appear more reasonable and legitimate by contrast – a process known as the radical flank effect (Simpson et al., Reference Simpson, Willer and Feinberg2022). In this sense, while radical tactics may alienate part of the public, they might also shift the boundaries of acceptable discourse, expanding support for non-radical groups or demands.

Whether protesters garner public support also depends on individuals’ ideology. Studies have shown that individuals are more inclined to support protests in areas that align with their existing values or political affinity (Olsen, Reference Olsen1968; McCright and Dunlap, Reference McCright and Dunlap2008). Moreover, right-wing individuals are reported to be less supportive of protests in general compared to left-wing-oriented individuals, suggesting an ideological asymmetry in protest support. This may stem from the fact that liberals tend to advocate for social change, while conservatives are generally more focused on defending the status quo (Jost et al., Reference Jost, Becker, Osborne and Badaan2017).

One could argue that because protests and civil disobedience are predominantly undertaken by progressive movements, they are naturally more susceptible to criticism from conservatives who may oppose not just the means but also the substantive claims of the protesters. However, recent experimental evidence suggests that conservative individuals disapprove of both conservative and liberal protests, whereas liberals show significantly greater support for non-conservative protests than for conservative ones (Barker et al., Reference Barker, Nalder and Newham2021). Furthermore, the assumption that conservatives uniformly defend the status quo is not entirely accurate. Research indicates that more radical right-wing individuals also advocate for social change, albeit in a reactionary direction (Becker, Reference Becker2020). This strengthens the argument that support and opposition to protests may not always be rooted in the nature of the tactics but rather in disagreement with the ideological goals of the movement. Yet regarding climate protests, a study conducted on the US American public (Bugden, Reference Bugden2020) found that Republicans were the least supportive of them, regardless of the protest tactic adopted; Independents were supportive only of peaceful marches, while Democrats were supportive of both peaceful marches and acts of civil disobedience. These findings seem to be in line with the literature on polarization of public opinion on the issue of climate change (McCright and Dunlap, Reference McCright and Dunlap2011), and the role of ideology in predicting more pro-environmental political preferences (Mannoni, Reference Mannoni2025), with more left-wing individuals being usually more likely to stand for environmental protection.

Finally, a protest’s impact may also vary depending on what they are measured to have an effect on. Compared to attitudinal outcomes, behavioral outcomes are typically more resistant to short-term influences, as they involve a higher personal cost and commitment. To account for this, this study includes attitudinal, intentional, and behavioral items to test the effect across a diverse range of outcomes (see below for a detailed description of each dependent variable).

Climate protests targeting artwork

Since 2018, new central actors have emerged in the landscape of protests for environmental protection, the most popular being FFF and Extinction Rebellion (XR) – the former mostly adopting strikes as its main protest tactic and the latter relying more on acts of civil disobedience. In 2021, XR activists launched a permanent civil disobedience campaign called Last Generation (“Ultima Generazione,” UG) (Zamponi et al., Reference Zamponi, Ferro and Cugnata2024), and when a new network labeled A22 was founded in April 2022, UG soon split from XR to join it – as did other teams in several European countries, the United States, and New Zealand (Kinyon et al., Reference Kinyon, Dolšak and Prakash2023). In May 2022, the first act of art pseudo-vandalism occurred in Paris, targeting the Mona Lisa, and since then, different teams of the A22 Network in various countries have engaged in similar acts of civil disobedience for the climate.

Although often framed as irrational or attention-seeking in media commentary, these protest actions are informed by an internal strategic rationale. As reported in the study conducted by Zamponi et al. (Reference Zamponi, Ferro and Cugnata2024), activists explicitly distinguish between horizontal conflict, which engages ordinary people and aims to trigger discussion or confrontation among peers (as in road blockades), and vertical conflict, which directly targets symbols of institutional power, including ministries, parliaments, or, in a more symbolic variation, artistic heritage. From this perspective, actions such as smearing artworks are seen as hybrid forms that pursue confrontation with institutional power, while simultaneously causing outrage and strong emotional reactions among the public. These forms of symbolic confrontation are meant to disrupt normality to dramatize the existential urgency of the climate crisis and its stakes (Zamponi et al., Reference Zamponi, Ferro and Cugnata2024). This resonates with Salamon's (Reference Salamon2019) notion of “emergency mode,” whereby activists must first enter a state of existential urgency themselves to communicate and spread that sense of crisis to the broader public. Even if the general public may not be their primary target, provoking conversation and emotional engagement is part of a broader strategy aimed at amplifying visibility and institutional pressure via these actions.

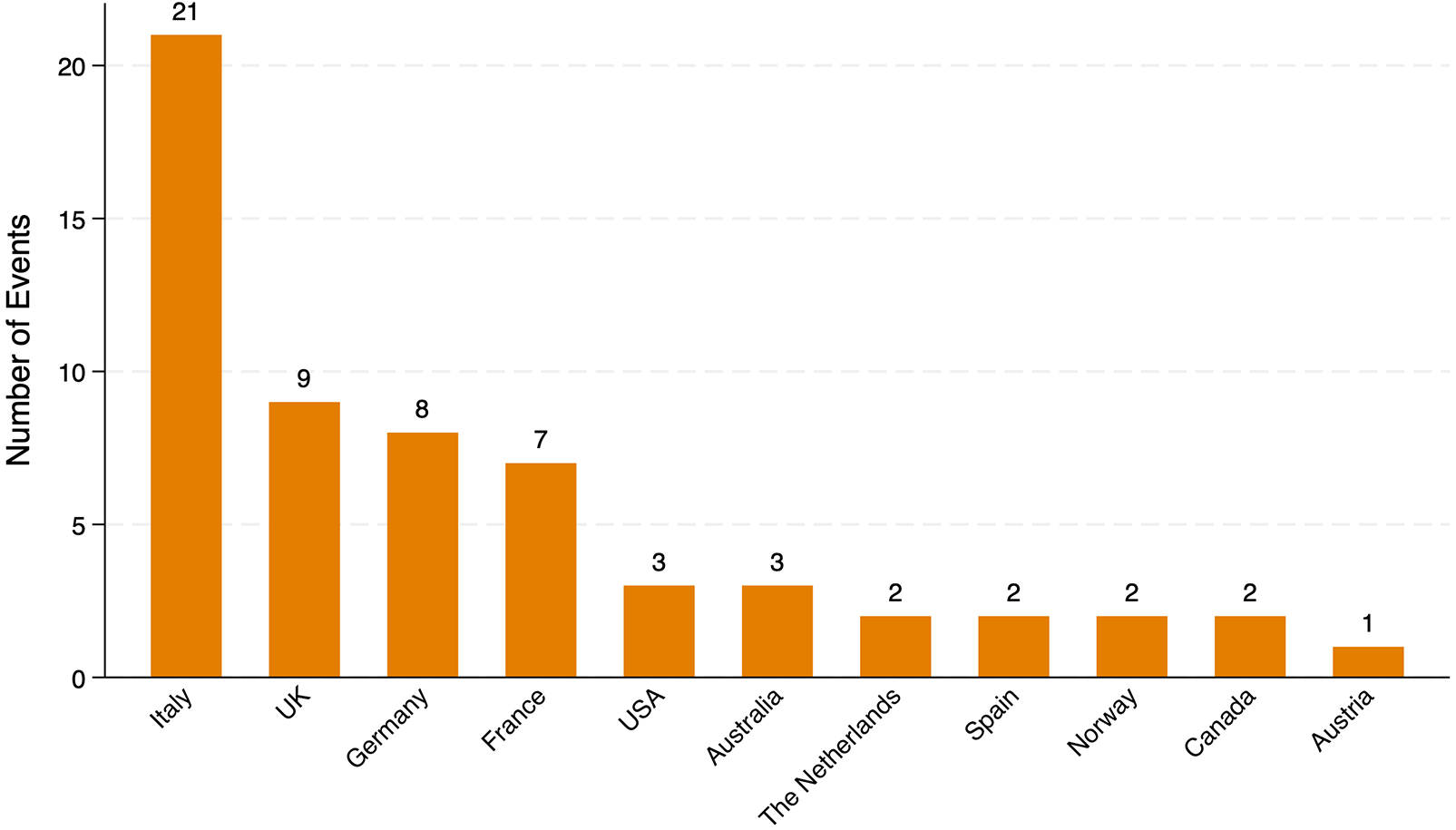

Between May 2022 and August 2024, 60 of those events occurred worldwide. From Figure 1, which shows the distribution by country, Italy emerges as a particularly relevant context for analysis due to the frequency of such events and, therefore, expected intensity of related media coverage. In January 2024, a new law was passed in Italy, upon a proposal of the Meloni government, to sanction the “destruction, dispersion, deterioration, defacement, defiling, and unlawful use of cultural or landscape assets,”Footnote 2 setting very harsh administrative fines ranging from 10,000 to 60,000 euros and likely violating the European principle of ne bis in idem Footnote 3 (Visconti, Reference Visconti2024), suggesting an intention of the legislator to swiftly suppress the protest wave.

Figure 1. Number of art pseudo-vandalism events by country.

Existing survey data suggests that climate protests targeting artwork have not been well received by the Italian public. According to a CATI survey conducted in May 2023 (IPSOS, 2023), 54% of respondents considered the protests by eco-activists who deface monuments or block roads as “unacceptable,” while only 35% found them “excessive but understandable given the importance of the issues addressed.” The remaining 11% either did not express an opinion or did not respond. More recent data confirmed the general trend: a February 2024 poll reported that only 22% of Italians supported climate activists, highlighting widespread public skepticism toward their actions (Diamanti, Reference Diamanti2024). Interestingly, a simultaneous survey comparison found that 77% supported the contemporaneous farmers’ roadblocks, suggesting that the low support for climate activists may reflect not only the controversial nature of their tactics but also the more prolonged and recurrent character of their protest campaign (Biancalana and Mancosu, Reference Biancalana and Mancosu2025). Moreover, the skepticism toward climate protest targeting artwork is consistent with broader trends in Italian public opinion, which tends to value cultural heritage highly, as a source of national pride (IPSOS, 2023).Footnote 4

As displayed in Figure 2, while the first year after May 2022 saw an initial boom of art pseudo-vandalism events organized by climate activists overall, followed by lower frequencies in the following periods, the trend in Italy (solid line in the graph) seems to be relatively more constant over time, including the aftermath of the new legislation passed in January 2024. While not clearly unique, the Italian case offers a useful setting to study public responses to this protest tactic. Importantly, the salience of these protests in Italy is not only a function of their frequency but also of the significant media attention they have received. As a result, even a minimal prime, such as a brief article and image, may plausibly activate pre-existing opinions or emotional responses, rather than introducing new information. This makes Italy a suitable case for studying the potential effects of symbolic, nonviolent protest tactics on public opinion.

Figure 2. Number of art pseudo-vandalism events by month.

This study examines whether climate protests involving art pseudo-vandalism are counterproductive, generating more backlash and antipathy than sympathy among the public. Such an expectation would resonate with the literature on backfire effects, according to which exposing conservatives to pro-environmental stimuli (such as pro-environmental protests) actually decreases their support for the cause (Hart and Nisbet, Reference Hart and Nisbet2012; Zhou, Reference Zhou2016; Dixon et al., Reference Dixon, Bullock and Adams2019). It has been suggested that backlash effects might be rather rare in the context of climate protests (Bugden, Reference Bugden2020), and that under some circumstances, such actions might even increase climate concern (Brehm and Gruhl, Reference Brehm and Gruhl2024); yet, the potential influence of repeated exposure to negative media framing – portraying art-targeting climate activists in particular as vandals – should not be underestimated. In fact, by systematically referring to these protests in the news as acts of vandalism, global media portrayed them as de facto violent demonstrationsFootnote 5 and that likely influenced their perception in the eyes of the general public. Indeed, echoing the terminology frequently employed by global media, the term of museum vandalism was adopted even in the scholarly community (Kinyon et al., Reference Kinyon, Dolšak and Prakash2023) in the earliest phase of this phenomenon. Here, connotating these protests as disruptive (as in Mann, Reference Mann2022; Shuman et al., Reference Shuman, Goldenberg, Saguy, Halperin and van Zomeren2024) but also seconding the concerns raised by Araya Lopez and Davis (Reference López and Colin2024) regarding the suitability of labeling them as acts of vandalism, I refer to them as climate protests targeting artwork and adopt the definition provided by Zamponi et al. (Reference Zamponi, Ferro and Cugnata2024). In their article on the evolution of the climate movement in Italy, they introduce the concept of art pseudo-vandalism to describe actions that mimic damage to art or monuments but, as they use washable paint or non-permanent glue, cause no actual harm to the artwork (Zamponi et al., Reference Zamponi, Ferro and Cugnata2024, p. 258).

Causal mechanisms and hypotheses

Drawing on the literature presented earlier on protest perception, media framing, and ideological predispositions, and following Beach and Littvay (Reference Beach and Littvay2020), I propose two causal mechanisms through which climate protests targeting artwork may affect public opinion. The first mechanism leads from the climate protests targeting artwork to a backfire effect via disapproval of the tactic. The second leads from the climate protests targeting artwork to polarization, via selective receptivity based on ideological predisposition. In particular, as displayed in Figure 3, art pseudo-vandalism, as a disruptive tactic, gets high media coverage (McCluskey et al., Reference McCluskey, Stein, Boyle and McLeod2009), and the media tends to frame it in a negative, delegitimizing way (Baranauskas, Reference Baranauskas2022). As a consequence of the fact that they get higher media coverage than non-disruptive protests, individuals are likely to be exposed to that information. Furthermore, as a consequence of the fact that the media coverage is negative and delegitimizing, the public develops what we may call tactic disapproval. When protest tactics are perceived as too radical or misdirected, they risk generating criticism more than sympathy (Feinberg et al., Reference Feinberg, Willer and Kovacheff2020). Indeed, it is likely that the public does not limit its disapproval to the protesters but extends it to the broader movement or aim they represent. Given that climate protests targeting artwork have been systematically framed as acts of vandalism by major media outlets (including the more neutral news agencies like the one used for the experiment in this study) (López and Colin, Reference López and Colin2024), their exposure may provoke negative emotional responses, leading to decreased pro-environmental concern and engagement.

Figure 3. Causal processes leading from climate protests targeting artwork to backfire or polarization effects.

The second mechanism, illustrated in Figure 3, suggests that individuals interpret climate protests targeting artwork through the lens of their ideological predispositions. While media coverage plays a role in shaping public discourse, individuals do not passively absorb information but filter it based on their existing political beliefs. Research indicates that conservatives tend to favor pragmatic, rigid, and authoritarian approaches to problem-solving (see the rigidity-of-the-right hypothesis, e.g. Jost et al., Reference Jost, Glaser, Kruglanski and Sulloway2003). Contrary to left-wing people, they tend to prefer stability, order, familiarity, and loyalty to their opposites – e.g. change, novelty, or rebellion (Jost, Reference Jost2009). And, as mentioned earlier, they prefer to protect the status quo rather than advocating for social change (Jost et al., Reference Jost, Becker, Osborne and Badaan2017), which leads right-wing individuals to usually be less supportive of protests in general, compared to left-wing individuals. Moreover, recent evidence indicates increased politicization of environmental issues: environmental protection, once broadly supported across parties, has become a divisive issue in Italian politics and party competition. Opposition to climate-related policies has gained traction among radical right parties, while left-leaning actors remain the main supporters of ambitious climate action (De Sio et al., Reference De Sio, Boldrini, Cataldi, Crulli, Emanuele, Gatti, Mannoni and Riggio2025). Consistent with this, in the Italian context, reactions to the climate protests targeting artwork were such that center-right and radical right-wing representatives strongly condemned the acts; center-left representatives were rather ambiguous in their responses; and radical left representatives expressed support. These elite cues are relevant factors to understand how different ideological groups may interpret the protests and their legitimacy. Right-wing individuals (perhaps even confirming their views thanks to elite’s cues) are likely to perceive the protests as radical and disruptive, reinforcing skepticism toward both the activists and the broader environmental cause. Conversely, those more radical left-wing may interpret the protests as a legitimate, even necessary, form of civil disobedience, aligning with their broader ideological commitment to environmental protection. This process, which we may call selective receptivity, is expected to result in polarization: right-wing individuals react negatively, distancing themselves further from environmental activism, while radical left-wing individuals may become more sympathetic or engaged. Unlike the backfire effect, which predicts a general negative response across the public, polarization implies a selective backfire: right-wing individuals become more alienated from environmental activism, while left-wing individuals might react more favorably (radical leftists) or remain unaltered in their stances (center-leftists). Table 1 summarizes the hypotheses to be tested for the expected outcome and the relative mechanism. While analytically distinct, tactic disapproval and selective receptivity are not mutually exclusive. Disapproval of the protest tactic may emerge independently of ideology, yet ideological predispositions can reinforce or attenuate such reactions. Both mechanisms are particularly plausible in the Italian context. First, Italy has witnessed a high frequency of climate protests targeting artwork, often accompanied by intense media coverage and condemnation by elites. This suggests that public attitudes toward the tactic may already be formed (and possibly polarized) prior to experimental exposure, making it an ideal setting to expect priming strategies to be effective in eliciting opinion retrieval. Second, as mentioned above, Italy's party system offered clear ideological cues: the governing right-wing coalition has consistently condemned these protests (and even issued ad hoc legislation to contrast them), while support has been more ambiguous or internally divided on the left – and even among voters of the radical left, some are strongly supportive for these protests, while others are quite skeptical (Improta and Mannoni, Reference Improta and Mannoni2025). These dynamics create a fertile ground for testing whether ideological predispositions condition how individuals interpret and respond to protest actions, in line with the selective receptivity hypothesis.

Table 1. Pre-registered hypotheses on the effect of climate protests targeting artwork on pro-environmental attitudes, intentions, and behavior

Data and methodology

The study relies on evidence from an original online survey experiment conducted in Italy between August 28 and September 11, 2024 (n = 1,004)Footnote 6, representative for gender, age, and regionFootnote 7. To the best of the author's knowledge, during the period of data collection, no climate protest targeting artwork took place (in Italy or elsewhere), which might have somehow biased the results. The data collection mode was CAWI (computer-assisted web interview). Measuring attitudes toward environmental protection is likely subject to social desirability bias, which makes respondents overreport behaviors or attitudes deemed as socially more acceptable and underreport those considered more undesirable or controversial (Fisher and Katz, Reference Fisher and Katz2000). While avoiding such bias altogether in interview-based social science research is not realistically possible, CAWI is usually considered less subject to it since respondents feel less pressured by the presence of the (virtual) interviewer, compared to CATI (computer-assisted telephone interview) or face-to-face interviews (Kreuter et al., Reference Kreuter, Presser and Tourangeau2008).

To estimate the effect of exposure to climate protests targeting artwork on public opinion, I performed OLS regressions for continuous dependent variables and logistic regressions for binary outcomes. Baseline models include only the treatment indicator, while additional specifications incorporate socio-demographic controls (e.g. gender, age, education, and financial hardship) and political predispositions (i.e. ideological self-placement) to assess robustness. To test whether the effect of protest exposure varies across political ideology, interaction models include an interaction term between treatment and ideological self-placementFootnote 8. All models use robust standard errors. The next sections clarify the experimental design, providing details on the treatment and outcome variables, as well as all other relevant variables included in the full models.

Treatment

In the study, participants were randomly assigned to either one of two conditions: treatment (T) or control (C). The experiment did not involve deception. Treated participants were exposed to a short piece of news reporting an act of protest targeting a rather famous piece of artwork – the Mona Lisa – by then targeted twice within less than two years. The treatment consisted of priming the respondents who would see the short text (173 words) of the article, as well as the reported image showing two activists in action (see Figure 1 in the Appendix). The news article shown to treated participants was taken from a real, non-manipulated, published article from a non-ideologically characterized Italian news agency - i.e. AGI (Bianchini, Reference Bianchini2024). The chosen article reported an event that occurred at the Louvre Museum in January 2024, targeting the Mona Lisa.Footnote 9 The article directly quoted the activists and neither explicitly criticized nor endorsed their actions. However, consistent with the frame adopted by Italian media on the issue, the act was labeled as an instance of vandalism. As such, the treatment was not intended to simulate novel exposure or introduce new information to shift respondents’ priors, but rather to serve as a salience prime by reactivating existing associations and attitudes. Rather than expecting large opinion shifts, the experiment aimed to test whether a minimal and realistic prime could still trigger measurable differences in attitudes and behavior. The participants in the control group did not see the article or the picture, nor were they asked whether they approved that strategy to raise awareness on climate change; instead, they were directly taken to the next set of questions.

The rationale behind the treatment design relates to the role that media framing and coverage play in shaping public opinion (Scheufele, Reference Scheufele1999) and public perceptions of protests (Brown and Mourão, Reference Brown and Mourão2021). When making judgments, individuals do not accurately assess all the information they have ever encountered, but rather rely on the information that media coverage makes readily available and easier to recall (Iyengar, Reference Iyengar1994). After prolonged exposure to a consistent media frame, individuals tend to retrieve the narratives they have stored when primed to think about a related event or topic (Matthes, Reference Matthes2007). Applying that to the specific case here examined, the consistent negative framing of climate protests targeting artwork by Italian media should influence the information retrieved by respondents who are primed to think about these events.

Furthermore, by the time the survey experiment was conducted, no incidents of climate-related art pseudo-vandalism had occurred for a few months, in Italy or abroad. The timing strengthens the quality of this research design and further supports the interpretation of the treatment as a salience prime, as it allows to assert with more confidence that participants in the control group – who were not prompted to think about climate protests targeting artwork – had little reason to retrieve their prior views on these events when answering questions on the broader issue of environmental protection and climate change. Consequently, this should minimize the risk of contamination and enable us to observe a cleaner effect of the treatment on the measured outcomes.

To ensure that treated participants engaged with the priming stimulus, respondents in the treatment group were asked their opinion on the protest tactic as a strategy to raise awareness about climate change immediately after being exposed to the news article. While it is not, strictly speaking, a formal manipulation check due to the absence of a comparable measure for the control group, this measure effectively confirms that the treatment group processed the protest-related information, offering valuable insight into their engagement with the stimulus. Following this, respondents in both groups answered questions aimed at measuring their attitudes toward environmental protection, their intention to engage in political participation for the environment, and their pro-environmental behavior. Depending on the outcome variable examined, the analysis employs linear or logistic regression analysis to test the significance of between-group differences.

Outcome variables

Table 2 reports the exact question wording for each item included in the final part of the survey, after the treatment, to measure the outcome variables.

Table 2. Outcome variables

Environmental concern

Environmental concern is a multidimensional concept comprising three components: a cognitive dimension, consisting of awareness that environmental harm is caused by human activities; an affective dimension, usually expressed through emotional reactions to the threat of environmental destruction; and a conative dimension, which can be understood as the readiness or intention to take action to address the issue (Franzen and Bahr, Reference Franzen and Bahr2024). This study includes measures for all three aspects of environmental concern. The affective dimension was covered by two items. A question asked, “How worried are you about climate change?” and had a four-point answer scale, with the options being “not at all worried,” “a little worried,” “very worried,” or “extremely worried.” Then, a statement reading, “It's pointless to do what I can for the environment if others don't do the same,” was presented, which respondents could either select if they agreed or leave unselected if they did not.Footnote 10 To measure the cognitive dimension, two items read “Much of what is said today about environmental threats is exaggerated,” “Climate change is not dependent on human action.” Respondents could either agree or disagree with each. Finally, the conative aspect was covered by two sets of items. First, the statements “I feel a moral responsibility to contribute to protecting the environment” and “The government should protect the environment even at the cost of increasing taxes,” which respondents could select if they agreed. Then, three questions measuring the intention to engage with political participation for environmental protection: “Would you ever join a protest for the environment?,” “Would you ever sign a petition for the environment?,” and “Would you ever share on your social media a post to spread awareness on the issue of climate change?”; all three items had a four-point answer scale, ranging from “definitely no” to “definitely yes.” Table 2 summarizes, for each item, both the dimension of environmental concern it falls under and the specific indicator it measures.

Pro-environmental behavior

Besides pro-environmental attitudes, the study tests the effect of climate protests targeting artwork on pro-environmental behavior. Measuring pro-environmental behavior is challenging, as self-reported pro-environmental behavior may be subject to reporting biases, including social desirability (Kormos and Gifford, Reference Kormos and Gifford2014). Measuring it right after a treatment in a survey experiment design is even more challenging, given that the behavior – even if self-reported – needs to take place after the exposure to the treatment. To overcome these issues, in this study I attempt to use two proxies for two instances of political pro-environmental behavior – namely, pro-environmental voting and donating money to a pro-environmental organization.

As for the former, based on Mannoni (Reference Mannoni2025), I consider pro-environmental voting as an instance of pro-environmental behavior, following an outcome-oriented rather than motivation-based criterion. Hence, I calculate the greenness of each vote choice by linking the survey responses to data from the party-level expert survey CHES, multiplying for each party its salience score on environmental protection by the distance between its position on the environment and the average position of all parties in the system on the same issue (Mannoni, Reference Mannoni2025). However, since the aim of this study is to test the impact of the treatment on pro-environmental voting, it is not possible to look at past vote choice. Hence, I here rely on a common proxy for voting behavior – i.e. vote intention. While it is technically not an observed pro-environmental behavior, it is the best proxy that might possibly be used for pro-environmental voting in this case. The pro-environmental voting score calculated for each party is linked to the party selected by each respondent as they answer the question, “If there were elections tomorrow, which party would you vote for?” In the case of Italy, this translates into a variable with values ranging from −6 (in the case of the League) to 22 (in the case of the Greens and Left Alliance). To facilitate interpretation and reduce the impact of extreme values and very large confidence intervals, the variable was then recoded into an ordinal one, ranging from score 1 for the least pro-environmental party to 6 for the most pro-environmental option.

Regarding observed pro-environmental behavior, I measured it as the respondents’ final choice to either keep the 1 euro monetary bonus for themselves or else donate it to one of three pro-environmental organizations listed (Legambiente, WWF, or Greenpeace)Footnote 11. Since participation in the protest cycle by these environmental organizations was not prominent (Zamponi et al., Reference Zamponi, Ferro and Cugnata2024), they should represent a good measure of commitment to contributing to pro-environmental organization, whose reputation is not directly linked with that of protesters engaging with art pseudo-vandalism.

Overall, the outcome variables included in this study range from attitudinal to intentional and behavioral items. Since donating money is clearly more costly than declaring concern about climate change, it is reasonable to expect that some items may be more resistant to any treatment effect. However, outcome variables that were so diverse in terms of cost were deliberately included to assess how far the effect – if at all – could extend beyond attitudes to more tangible forms of engagement.

Other relevant variables

The analysis includes models controlling for socio-demographic variables and ideology. Gender is measured by asking the respondent whether they are a woman, a man, non-binary, or prefer not to say. Based on their birth year, respondents were assigned to cohorts: Silent generation (1930–1945), Babyboomers (1946–1964), Generation X (1965–1980), Generation Y, also known as Millennials (1981–1996), and Generation Z (1997–2006)Footnote 12. Regarding the financial condition of the respondent, the survey included a question on perceived economic hardship – i.e. how they manage to make ends meet at the end of the month, ranging from “with great difficulty” to “with great ease.” The level of education was operationalized as low (up to middle school completion), medium (high school completion), and high (holding a university degree). Finally, as a proxy for ideology, the models include the respondent's self-placement on the left–right axis, originally measured in the survey on a 10-point scale where higher values indicate more right-wing self-placement.

Results

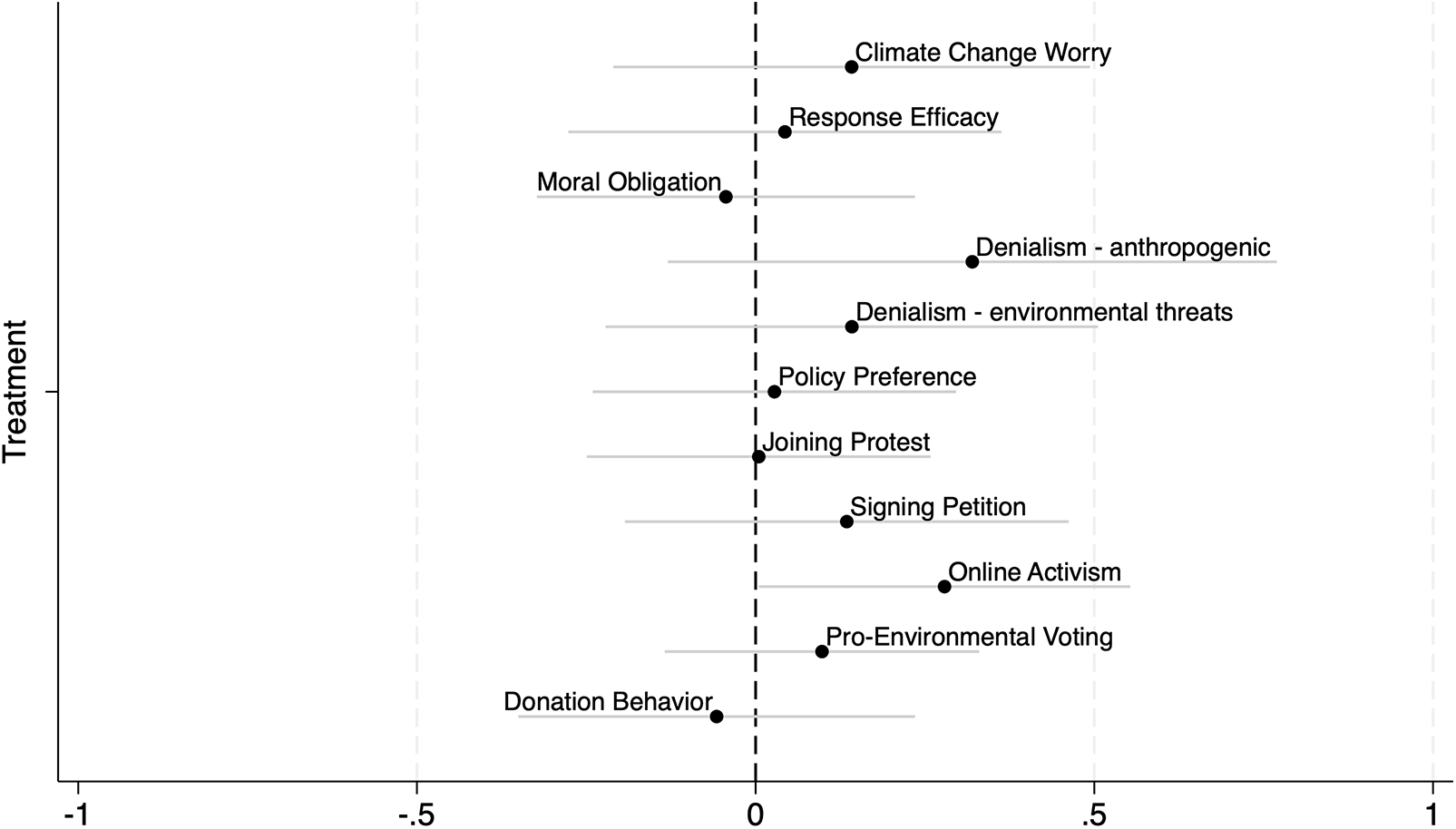

The findings presented in Figure 4 consistently show null effects across all tested dependent variables. The treatment, which exposed participants to a controversial climate protest targeting a piece of artwork, does not appear to significantly influence pro-environmental attitudes or behaviors. These results suggest that exposure to such protests does not provoke a measurable backlash in support for environmental action. Given that this study was sufficiently powered to detect medium effects ≥10%, the consistent null results across all models provide strong evidence against medium or large impacts of climate protests on public opinion. This suggests that such protests are unlikely to meaningfully shift public opinion, either positively or negatively.

Figure 4. Coefficient plotting of treatment effects on each dependent variable. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Full regression models can be found in the Appendix (Tables A1–A11) and include, for each dependent variable, robustness tests controlling for socio-demographic variables and ideology. In the baseline model, only including the treatment variable (see Figure 4), the treatment seems to have a slightly statistically significant positive effect on the item labeled as online activism – i.e. the willingness to share social media content to raise awareness on climate change. However, Table A9 in the Appendix shows that the significance of this effect diminishes when controlling for socio-demographic factors and ideology.

Interestingly, despite not being hypothesized ex ante, this small positive effect on willingness to engage in online climate activism could plausibly reflect a radical flank dynamic. As mentioned earlier, according to this mechanism, exposure to radical protest tactics may increase the perceived legitimacy or attractiveness of more moderate forms of activism (Simpson et al., Reference Simpson, Willer and Feinberg2022). In this case, while the protest tactic depicted was highly controversial, it may have indirectly increased participants’ willingness to engage, by contrast, in less disruptive behaviors, such as sharing pro-climate content online. Future research could more explicitly examine these cross-tactical dynamics within the environmental movement.

The first hypothesis anticipated a backfire effect, whereby exposure to the protest would negatively affect pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors. However, across all models, the treatment effect consistently fails to achieve statistical significance, providing no evidence to support this hypothesis. These results challenge the widespread assumption that protests targeting artwork alienate the public or undermine support for environmental causes. This suggests that media-driven narratives portraying such protests as counterproductive or socially disruptive may be overblown and that, rather than harming pro-environmental attitudes or discouraging behaviors, these protests may leave public opinion rather unchanged.

The analyses presented in Table 3 delve into the moderating role of participants’ attitudes toward the protest tactic. Specifically, they distinguish between those who endorsed or were uncertain about the tactic (“I endorse it/DK”) and those who outright rejected it (“I do not endorse it”), comparing both groups to those in the control group, who were not primed to the protests. These results offer a nuanced look into whether antipathy toward the protest tactic influences the effects of the treatment on pro-environmental outcomes. The results suggest that endorsement of the tactic influences some responses to the protest but also leaves room for further reflection on its broader implications.

Table 3. Regression results of tactic disapproval

Standard errors in parentheses.

* p < 0.10, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

For climate change worry, the treatment effect is statistically significant and positive among those who endorsed or were unsure about the tactic. In contrast, no significant effect on worry is observed among those who affirmed they did not endorse the tactic. This asymmetry suggests that protests targeting artwork might deepen existing convictions among those already sympathetic, while failing to sway those with unfavorable preconceptions.

The most pronounced effects emerge in the conative environmental concern – i.e. the dimension that concerns the intention to do something good for the environment. Those endorsing or undecided about the tactic reported a higher willingness to join protests and, to a lesser extent, engage in online activism. These findings suggest that climate protests targeting artwork may have mobilized sympathizers, providing them with a sense of urgency or shared purpose. However, no such effects are observed among those who rejected the tactic, who seemed to have remained rather unaffected across those measures. This polarization might suggest a selective resonance of these acts of civil disobedience, which have the potential to activate engagement among some while leaving others indifferent.

Across most attitudinal outcomes, including moral obligation and support for climate policies, the treatment effect is not significant for either group. This null result suggests that these protests, while potentially capable of mobilizing behavior among sympathizers, do not necessarily alter fundamental attitudes toward environmental protection or policy support. Similarly, the lack of significant effects on donation behavior, regardless of endorsement, indicates that the protest tactic may not translate into changes in pro-environmental actions.

With regard to the hypothesis on selective receptivity, the combined graph below (Figure 5) presents the interaction between ideology and treatment across all dependent variables. Each graph displays predicted probabilities derived from logit regressions, except for pro-environmental voting, which is treated as a continuous variable and is therefore represented by linear predictions from an OLS regression model. As illustrated in the graphs, there is no evidence that individuals respond to the treatment differently based on their ideological predispositions. While ideology, measured by the left-right scale, consistently emerges as the single most significant predictor across models (see Tables A1–A11 in the Appendix), the interaction terms between treatment and ideological positioning remain statistically insignificant throughout.

Figure 5. Effect of treatment by ideological self-placement. The thin dashed grey line refers to the control group; the thick solid black line indicates the treatment group. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

These results suggest that selective receptivity does not operate in this context, meaning that being exposed to climate protests targeting artwork neither amplifies nor diminishes pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors among individuals with different ideological orientations. The next section discusses the limitations and implications of these findings.

Conclusion

This paper investigates the impact of climate protests targeting artwork on public opinion, specifically on environmental concern and pro-environmental behavior. Using data from an original survey experiment conducted in Italy, the study examines whether exposure to these protests generates backlash, mobilizes support, or has no significant impact at all. The findings are quite consistent. Across all models, the treatment coefficients were statistically insignificant. Whether examining affective, cognitive, or conative environmental concern or pro-environmental behaviors, there was no evidence to suggest that exposure to climate protests targeting artwork influenced these outcomes. These results remained consistent across alternative specifications, including those controlling for socio-demographic variables and ideology. While left–right self-placement emerged as the most significant predictor of pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors, its role was independent of the treatment, and interaction terms between ideology and treatment consistently failed to reach statistical significance. This reinforces the conclusion that the treatment effect is null, regardless of individuals’ political alignment.

Overall, these findings challenge the assumption that art-targeting protests have widespread detrimental effects on public support for environmental causes, while also failing to substantiate claims that they mobilize greater support. However, there is some evidence suggesting that the effectiveness of these protests might depend on prior attitudes. For those who do not antagonize the protesters and their tactics, exposure to climate protests appears to increase environmental concern and willingness to act. Conversely, the protests do not seem to either engage or shift the perspectives of those already opposed. Thus, no evidence in this study supports the idea of a polarizing potential of such contentious demonstrations. In this light, the results suggest that while these protests may deepen the commitment of a subset of supporters, they might be unlikely to broaden the movement's base by earning sympathizers, or further alienate skeptics, as hypothesized in this paper.

Finally, although that was not the main aim of this analysis, this research provides once more strong evidence to support the idea of the politicization of the issue of environmental protection. Among the socio-demographic factors considered, predictors such as gender, generation, education, and financial hardship were relevant in some models but not consistently so. In contrast, a right-wing ideological self-placement emerged as a persistent and robust predictor of less pro-environmental stances, regardless of experimental group, dependent variable, or social subgroup. These findings suggest that environmental protection should not be framed by scholars as a valence issue, i.e. a universally shared priority, but rather as a positional one, strongly and mainly characterized by ideological divides.

What can we learn from this main null? Following the framework proposed by Alrababa'h et al. (Reference Alrababah, Williamson, Dillon, Hainmueller, Hangartner, Hotard, Laitin, Lawrence and Weinstein2023), it is useful to assess whether the absence of significant effects can be attributed to limitations in measurement, treatment design, statistical power, or to spillover and contamination across groups, and to reflect on what can be learned from this evidence as part of a cumulative scientific effort in political behavior research.

Measurement issues can be reasonably ruled out. The dependent variable was operationalized through a wide range of indicators covering attitudinal, intentional, and behavioral dimensions, and the absence of significant differences holds virtually across all of them, suggesting that the null is not driven by measurement error or construct validity problems. Issues of treatment strength and implementation also seem unlikely explanations. The stimulus was a real news article deliberately chosen because it referred to the protest as “vandalism” – reflecting the substantively negative media coverage of such events in Italy – while maintaining a relatively neutral, factual tone typical of a non-politicized news agency. Although the article included the activists’ quotations, over four in five treated respondents reported disapproving of the protest, confirming that the prime reactivated existing associations without inducing positive bias. As for spillover and contamination, these risks appear limited. The last major protest occurred months before fieldwork, and no comparable events received media attention during that period, when other issues – such as the reopening of schools and workplaces, the beach concessions controversy, and the rising cost of living – dominated the national news agenda. While it is nowadays nearly impossible to identify a period entirely detached from climate-related reporting, any overlap concerns background salience on the climate issue rather than on climate protests. A more plausible explanation lies in statistical power. Due to budget constraints, the design was powered to detect larger effects, so it is possible that smaller effects went undetected due to limited statistical power. Finally, the null results might be a consequence of the fact that, due to widespread visibility and repeated occurrence of such protests in Italy, many respondents had already updated their attitudes toward the environmental cause based on their perception of this tactic. Or else, an additional explanation for the null results may lie in the broader political context. The increased politicization of the climate issue in Italy may have crystallized citizens’ stances to the point that they have become less susceptible to external stimuli. Future studies should consider larger sample sizes to test for smaller effects or, better, test these hypotheses through longitudinal data – e.g. a panel spanning the 2022–2023 protest peak. By contrast, geographically bounded natural experiments would be less suited to this case: unlike street demonstrations or road blockades, art-targeting protests are brief, spatially isolated, and primarily experienced through national media coverage rather than direct local exposure, making it difficult to identify exogenous spatial variation in treatment intensity.

Despite these limitations, this research contributes to cumulative knowledge on the effects of climate protests on public opinion by documenting under which conditions exposure to such actions may not largely alter public opinion.

Funding

The research has been funded by the Field and Archival Research grant for doctoral candidates from Central European University (CEU).

Data

The replication dataset is available at https://thedata.harvard.edu/dvn/dv/ipsr-risp. This study was preregistered prior to data collection on the Open Science Framework (OSF). The preregistration is available at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/EPN4Z.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/ipo.2025.10087.

Acknowledgements

The author gratefully acknowledges Central European University, where this research was developed as part of her doctoral dissertation.

Competing interests

The author declares none.