The dinner I was invited to was held after the monthly meeting of the Kayseri Chamber of Industry on a pleasant summer night in 2015. The spacious dining hall on the top floor of the chamber headquarters was filled by over a hundred industrialists from large and small companies. Kayseri's nationally celebrated cuisine was lavishly represented on our table. I was in a good mood because I had been looking forward to this opportunity for the previous two years. This meeting, and especially the part closed to the press, would hopefully give me many insights into the relations among the members of the chamber.

I also was happy that I was seated with the owners of small- and medium-sized manufacturing enterprises (manufacturing SMEs). This arrangement would allow me to engage with different strata of the industrial business community and observe their interactions with each other. My plan was first to talk to those small industrialists, and then to chat with the business leaders of the city at the after-dinner reception.

Luckily, the businessmen at my table were interested in my research project and we found ourselves in a warm, yet intense conversation. Kayseri is a major industrial center and a closely studied city with regard to the relations between the rise of right-wing politics in Turkey and the late industrialization of the country, after the 1980s.Footnote 1 The primary purpose of my fieldwork was to identify the outstanding characteristics of the major manufacturing enterprises in Kayseri and the relations of local companies with their local subsidiaries. That is why I was all ears when the small industrialists began to share their perspectives on a variety of issues, such as the prospects of industrial development in the city and the potential effect of the ongoing slowdown of the Chinese economy. Generally pessimistic about the future, they were looking for a solution to a variety of challenges that followed the 2008 financial crisis. Our conversation slowly shifted to Erciyes University, the biggest and oldest in the city. They were upset with the disconnect between this institution and the business community. They sought a pragmatic approach to motivating the Erciyes faculty to collaborate with them to boost their productivity, decrease their energy costs, and expand their product spectrum; they felt that the faculty had been generally unresponsive. They had doubts (and open criticisms) about the academic qualifications of the Erciyes faculty, who, they believed, failed to keep up with the recent developments in their fields.

They were rather baffled when I asked them if they had ever invested any of their own financial resources toward any kind of academic research at Erciyes. They did not expect this question, as they tended to see themselves as the recipients of their relationship with the university, not as financial patrons of the institution. This did not particularly surprise me, though, because administrators of organized industrial districts, the semiofficial Small and Medium Industry Development Organization (KOSGEB in Turkish), and scientific research parks (in Turkish, “technoparks”) that I had interviewed earlier were similarly upset by the lack of collaboration between the academic staff of their own regional universities and the industrialists and their businesses. A year earlier at another meeting in Denizli, another major industrial center, the head of the city's technopark made it abundantly clear that this distance posed a major challenge to the future of the establishment. As an associate professor of chemical engineering, he had a good understanding of how the research process worked in academia. He also had to convince the industrialists of the city to invest in the technopark. His solution was to knock on the doors of those local industrialists and introduce them to the prospects of collaborative projects with the technopark. A second challenge was to convince the academic staff at the local Pamukkale University. As he put it, “It is hard to convince scholars at the university to take part in these projects. Many of them still ask about job security with a mentality of tenured public employees.”Footnote 2

During my field research, which I conducted between 2012 and 2015, I made many similar observations about the schism between the academic staff and those industrialists linked to the academics’ “job descriptions” and socioeconomic status. For the industrialists, the professors’ primary duty was to help them to grow their profit margins, but they believed that faculty members of their local universities played a parasitic role in their city's economy. The academics who could work for the industrialists were usually proud of what they were doing, however they dismissed the businessmen for their lack of education and etiquette. Indeed, most of the businesspersons I talked to in various Turkish cities were high school dropouts.

Notwithstanding those viewpoints that emphasize the local conditions in cities and the sociocultural traits of individuals, this divergence, I believe, points to a key dynamic behind the erosion of academic and cultural freedoms in Turkey within the last decade: the university has gradually ceased to be the leading institution of technological research in the country, whereas manufacturing companies have assumed a growing role in the guidance of such research activities both on and off university campuses. In many cases, universities let private researchers use their facilities and indirectly subsidize local companies.Footnote 3 In fact, even though the actual research takes place on university campuses, local companies set the research agenda and benefit from the results. In other words, universities have increasingly become a technology platform for manufacturing companies, rather than an autonomous space for scholarly research.

The Downfall of the University and the Rise of the Industry

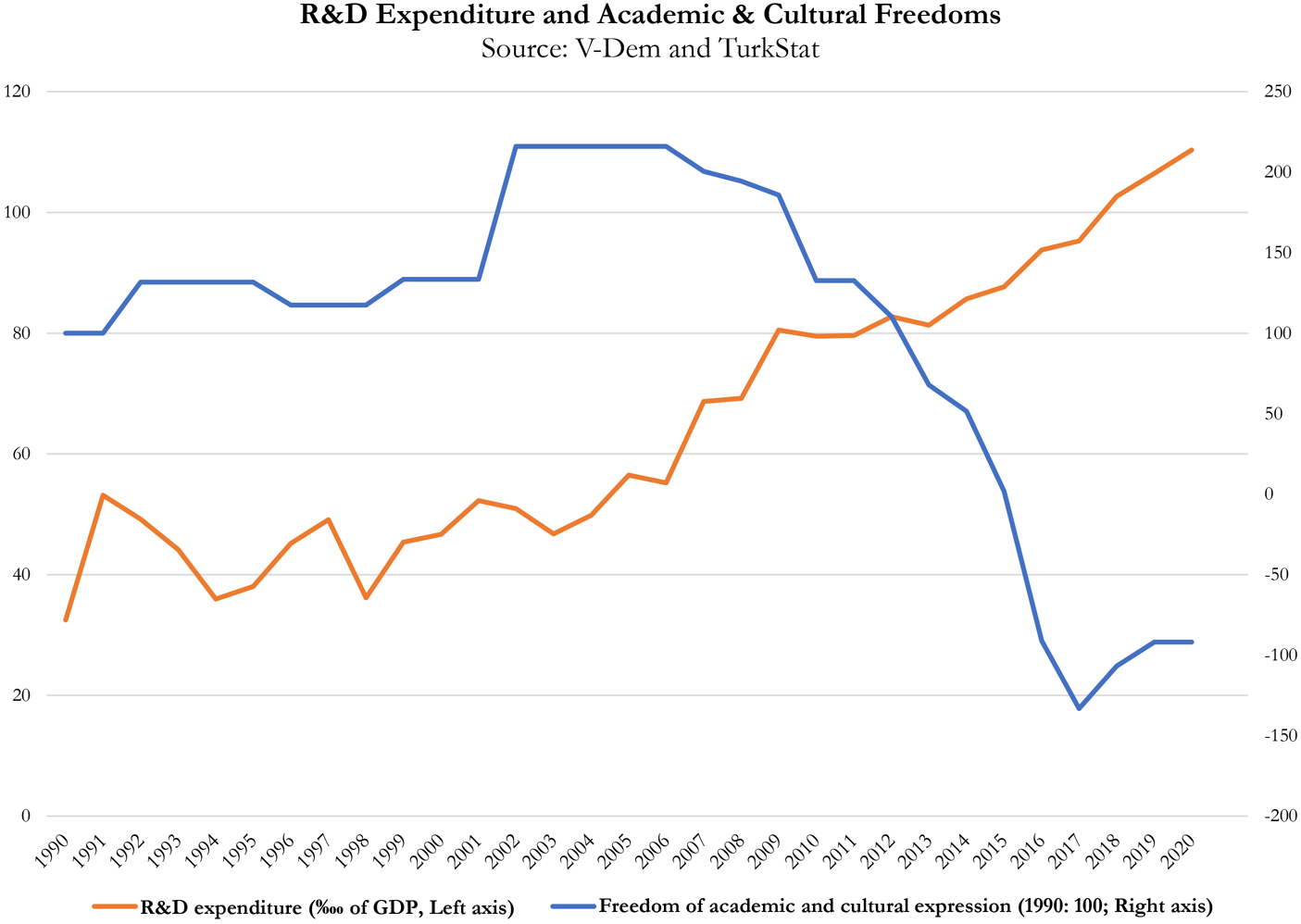

The available figures corroborate my fieldwork observations about the split in mindsets between industrialists and scholars. According to the Turkish Statistical Institute (TurkStat) data on research and development activities since 1990, the share of R&D expenditure in the Turkish GDP more than doubled between the early 2000s and the late 2010s.Footnote 4 In fact, most of the growth in the aggregate R&D expenditure took place after the (Islamist) Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi, AKP) came to power in 2002.

The freedom of academic and cultural expression scores in the University of Gothenburg's Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) data set illustrate a contrasting trend in the same period.Footnote 5 The related scores significantly improved between 1989 and 2003 and reached the highest level since the 1960s. The very year when AKP came to power overlapped with, first, a stagnation in these scores for its first three years in government, and then a dive afterward. In other words, Turkey has been investing in expanding resources in R&D activities for the last two decades under AKP rule, whereas the scholarly freedoms of academics have been severely curbed during the same period (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Research and development expenditure and academic and cultural freedoms in Turkey.Footnote 6

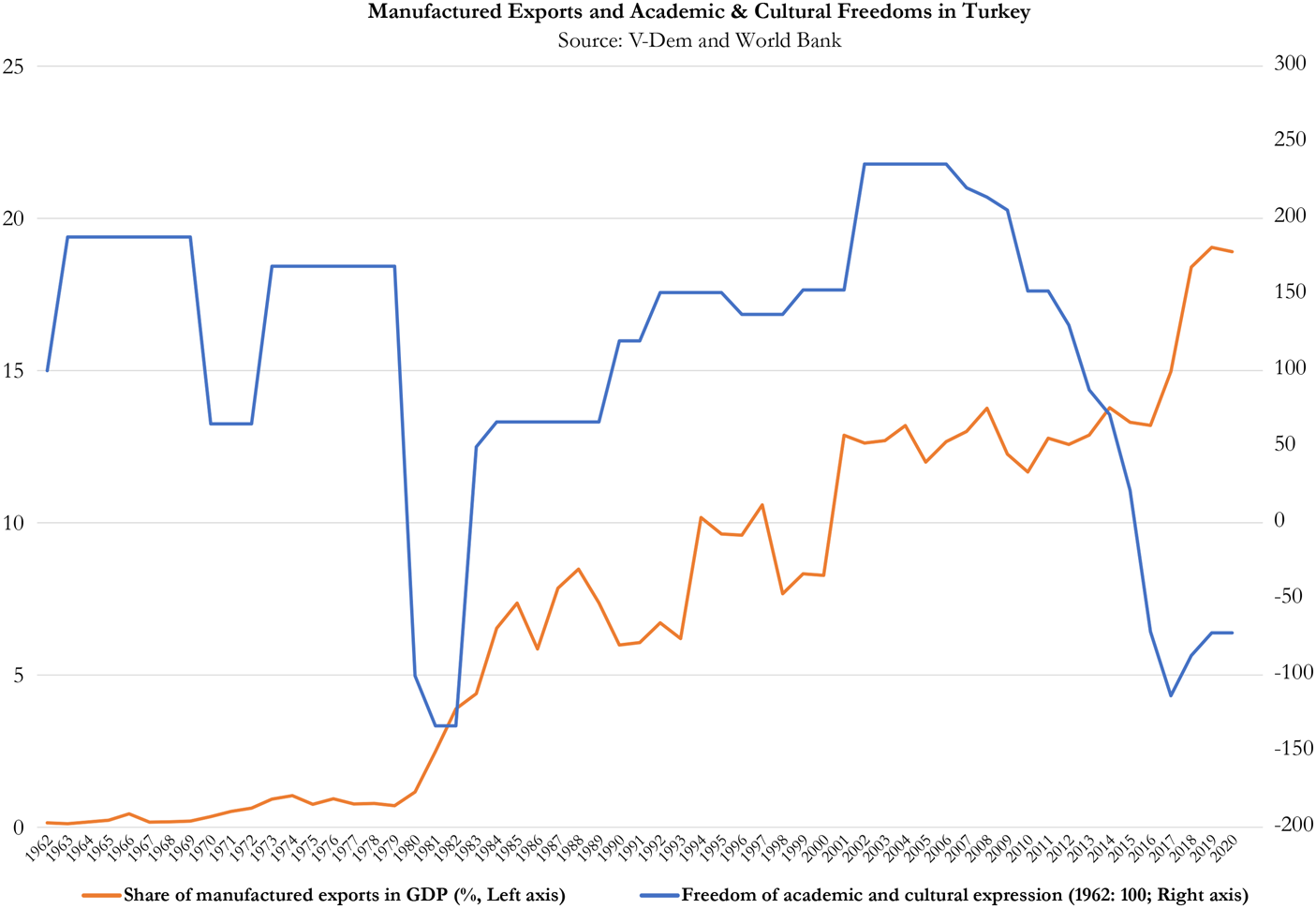

The 2010s were, however, not the first postwar decade since the 1960s when academic freedoms were severely restricted. The first major deterioration of academic freedoms during the last six decades happened in the wake of the bloody coup in 1980, which played an instrumental role in the transition from import-substituting industrialization policies to a new export-led growth strategy. This expansive strategy put a heavy emphasis on the light export–oriented manufacturing industries as the main engine of economic growth and a structural solution to the chronic foreign currency deficit, which the Turkish economy had suffered from in the 1970s.Footnote 8

The purge of progressive scholars who were skeptical of this new strategy from the university in the name of the Turkish military's war on communism was one of the factors that facilitated the transition process. The manufactured exports, then, swiftly increased their share in the GDP from 1 percent in 1980 to 10 percent in 1990 (and to roughly 20 percent by 2020). It took two decades for the academic and cultural freedoms in the early 2000s to get back to where they were in the 1970s, as manufactured exports became an even more important component of the national income. In fact, the beginning of a second surge in the manufactured export volume since the early 1980s coincided with a failed coup attempt in 2016. The AKP government used the failed putsch to justify firing thousands of public employees with unconstitutional government decrees and without due process, including roughly 400 scholars known as “the Academics for Peace,” who protested the Turkish government's military operations in the Kurdish region of the country in 2015 (Fig. 2).Footnote 9

Figure 2. Manufactured exports and academic and cultural freedom of expression in Turkey.Footnote 7

In other words, the postwar growth and decline of the manufacturing export volume and the progress and regression of academic freedoms in Turkey had a weak relationship until the 1980s, overlapped until the 2000s, and then took contrasting paths in the last two decades. Unlike the 1960s and the 1970s, when the universities played an important role in setting growth-oriented government policies through their participation in strategic plans at the national level (such as the Five-Year Development Plans), the university has been losing its influence over policymaking and its prestige for the last two decades.

Campus and Politics

The authoritarian targeting of Turkish academia rests on three broad pillars. First is the intimidation of progressive scholars and purging them from their positions whenever it is necessary or possible.Footnote 10 The second is the mushrooming of nonpublic universities with the financial and political support of the AKP government.Footnote 11 These institutions in Turkey do not provide tenure, regardless of the academic seniority or success of the scholar. Third is the derailing of research-related subsidies and funding from universities, redirecting it to private companies, which led to a split between the academic and professional interests of the academic staff.Footnote 12 Those who can secure funding from nonuniversity resources due to their disciplines or research interests, I believe, tend to support this transformation, whereas others are concerned about the growing influence of private interests on university campuses. The result is that academic staff in Turkey have been unable to unite to protect the position of the university in the pursuit scientific and technological advancement.

In fact, the declining sociopolitical status of universities is closely related to current patterns of industrial connections to the global economy. Some middle-income countries, including Turkey, have taken a labor-intensive, low-technology path to intensify their connectivity with global industrial supply chains. The Turkish case is, in this regard, exceptional: the share of high-technology exports in Turkey's total manufactured exports volume has not gone above 3 percent since the mid-2000s, whereas the related global value for 2007–20 soared to around 20 percent.Footnote 13 In this industrial topography based on low wages and technology, industrialists in general and owners of manufacturing SMEs in particular demand R&D activities that address their immediate needs regarding shopfloor dynamics and product spectra, and they have limited interest in long-term research projects that could address structural problems pertinent to their industries. One way to satisfy the needs of these entrepreneurial groups, who have a significant impact on the local politics of their cities, has been to dismantle the national university system and directly and indirectly subsidize these groups for their R&D activities—and let them use the universities’ human, technical, and financial resources as a major subsidy. The AKP has been closely following this recipe since the early 2000s.

Conclusion: Vaccines, Rockets, and Democracy

I am one of the “Academics for Peace” noted above. Along with hundreds of my colleagues, I lost my job at Ankara University, one of the biggest and most prominent higher education institutions in the country, because in 2016 I signed a petition to raise awareness of a major turning point in Turkey's recent political history. The AKP government abruptly ended peace negotiations with the Kurdish movement after it lost the majority in the parliament in 2015 and initiated a massive military operation in the Kurdish region of the country to rally its voters with feelings of nationalism and win the rerun election, in the same year that it sabotaged the coalition negotiations by capitalizing on a loophole in the constitution. According to the Human Rights Foundation of Turkey, “at least 198 civilians (including 39 children, 29 women and 27 persons over the age of 60) lost their lives” during this operation in 2015 and 2016, and the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights reported that “between July 2015 and December 2016, some 2,000 people were reportedly killed in the context of security operations in South-East Turkey. According to information received, this would . . . include approximately 1,200 local residents.”Footnote 14

I signed that petition for three reasons. The most important reason was to stop the civilian killings, especially by the government forces, which had (and have) the primary responsibility of taking all necessary measures to protect the lives of citizens. Second, as a scholar working on the modern political and economic history of Turkey, I was particularly concerned about the abrupt end of negotiations between the Kurdish movement and the Islamist government. As Kurds still have no constitutional recognition or protection of their ethnic and national identity in Turkey, the strategy of the government was not acceptable from a democratic perspective. I was (and am) convinced that this was a decisive turning point for Turkish democracy. Third, I was aware that the military operations against the Kurdish civilians were only one of the first steps in dismantling democratic institutions and, in particular, the university. Regardless of differences in political opinions, I expected a significant portion of roughly 200,000 scholars in the country to sign this petition, primarily to protect academic freedoms in the country.Footnote 15 What was at stake was the future of academia in Turkey. Unfortunately, only around 2,000 of those 200,000 scholars signed.

Our failure was “rewarded” with a series of unconstitutional government decrees in 2017 that blacklisted the signatories of the petition as terrorists. As I was away from my family due to the international travel ban (and did not want to accept the downfall of the democracy as the fate of my country before I did whatever I could), I advised the main opposition party for the next two years, with the hope that the next election in 2018 would change the power dynamics in the country.

I left the country after that election, because there were no immediate prospects for the return of democracy. Also, our exchanges with some of the high-level AKP politicians right after our dismissal convinced most of my colleagues and me that the government was determined to extend the international travel ban as long as possible, especially for those who were reluctant to repent their “sin.”

A few months after my adventurous journey to the New World, one of my old friends from college gave me a call. He was a successful researcher in hard sciences, running his own lab at a prestigious research university in the United States. We had a long history of friendship back in Turkey and I had always enjoyed his companionship, although I also was upset that he had not bothered to contact me during the most difficult period of my life, marked by the painful separation from my family. As a duty to our friendship, I felt obliged to express my feelings to him. I did my best to use the least hurtful words to share my disappointment and asked him if he was aware of what I had gone through. His response was blunt, “I thought this was about your politics.”

Even though I was aware that it would be a futile effort, I again did my best to calmly explain to him that my politics was only one (and a relatively insignificant) factor behind my decision to protest the Turkish government and that my “politics” was closely (and primarily) related to my scholarly expertise on modern Turkish history and social theory as well as my years-long research experience. More importantly, I reminded him of the consequences of what happened in 2015 and 2016 for Turkish academia. Whether he liked it or not, he had a role in this outcome as a result of his political apathy, which he probably justified with the protective layer provided by his discipline: for his entire adult life he was told that he was exempt from and above politics, as natural sciences were more important than politics. But both his informants and he, I reminded him again, were utterly wrong.

Undoubtedly, regardless of how it was expressed, my point shocked him, as he was used to being “the good guy” as long as he did his job at the lab. Maybe thanks to this entitled status, the comforts of which would be difficult for anyone to give up, he firmly held his ground: social scientists, humanists, and historians were given the task of sacrificing themselves to protect the academy, not the scholars who specialized in STEM, law, or medicine. They were assigned “nobler tasks” such as saving us from pandemics or taking us to other planets. In the meantime, others, who raised their voice in the face of a grave danger not only for democracy but also for scientific research like my friend's, and paid the price, were simply doing their job. Like many of my other my colleagues in Turkey and other parts of the world, some of whom are, of course, physicians, hard scientists, and legal scholars, I spoke up when others were silenced, and I lost many friends. I guess this is another price one has to pay when committing oneself to the protection of the academy as a part of the “job description.”

Acknowledgments

As a Marie Curie Career Integration Grant grantee, I would like to thank the European Commission for its support during my four years of field research in Denizli, Gaziantep and Kayseri between 2012 and 2015. I also would like to thank MESA Global Academy for giving me the opportunity to write this commentary. In particular, I am grateful to Mimi Kirk, Aslı Bali and Aslı Iğsız for their unconditional support, as well as Ilana Feldman for her helpful comments on the contribution.