1 Introduction

On August 3, 2022, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), the military of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), commenced its largest-ever live-fire exercises around self-governed, democratic Taiwan. Amid the worst cross-Strait frictions in decades, with relations between the United States and the People’s Republic of China (PRC; below “China”) at a post-normalization nadir, and just six months after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and announcement of a “no limits partnership” with Beijing, China’s seemingly disproportionate response to a U.S. House Speaker’s peaceful visit to a long-standing U.S. democratic and economic partner sent shockwaves around the world.

In the two years since, Beijing’s normalization of unprecedented or previously rare military and other actions designed to “punish” Taiwan’s democratically elected leaders has undermined the decades-old cross-Strait status quo and exacerbated long-standing fears of a potential conflict. Of particular concern are the PLA’s now regular crossings of the unofficial median line dividing the Strait, large aerial and naval maneuvers around Taiwan, and simulated joint precision strikes involving China’s aircraft carriers.

Beijing’s unprecedentedly large-scale military exercises since summer 2022 – including similarly massive exercises around Taiwan in April 2023 and May 2024 – are intended not only as valuable training opportunities for the PLA and to send coercive signals to leaders in Taipei. They are also designed to demonstrate to foreign audiences the rapidly modernizing and expanding PLA’s ability to encircle Taiwan; to blockade its trade-dependent economy, potentially as the opening phase of an invasion; and to complicate potential U.S. efforts to come to the rescue. This is in addition to increasing concerns about “gray zone” coercion, including activities by China’s coast guard – the world’s largest.

More fundamentally, however, Beijing’s recent escalation of rhetoric and provocative maneuvers are intended to send a political signal: to demonstrate the seriousness of the PRC’s claim of sovereignty over Taiwan based on its self-defined “one-China principle” (yi ge Zhongguo yuanze). That signal has not been lost in foreign capitals; in 2023, U.S. CIA Director William Burns publicly confirmed that Xi Jinping, the PRC’s paramount leader, has ordered the PLA to “be ready by 2027” to seize Taiwan. Importantly, he also noted that fact alone “doesn’t mean that conflict is imminent or inevitable” (CIA.gov 2023).

In short, although the PRC has never governed Taiwan Beijing is determined to “unify” Taiwan with the mainland – by force, if necessary. In stark contrast, and although views in democratic Taiwan concerning the island’s relationship with “China” are contested (see Section 2), no major political party there accepts Beijing’s contention that Taiwan is part of, or subordinate to, the CCP-led PRC (Chen Reference Chen2022). For their parts, President Tsai Ing-wen (2016–2024) and her successor William Lai (2024–) – both from Taiwan’s left-of-center Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) – maintain that the democratic “Republic of China Taiwan” is already a “sovereign” and “independent nation.” (Zhonghua Minguo Zongtongfu Reference Minguo Zongtongfu2020; Reference Minguo Zongtongfu2024). Aware that any move toward a de jure declaration of independence could provoke a conflict, however, as president both also expressed a commitment to maintain the status quo – the preference of the overwhelming majority of Taiwan’s voters.

1.1 Internationalizing Concerns amid the Increasingly Precarious Status Quo

Since the DPP’s return to the presidency in 2016, PRC leaders have repeatedly called Taiwan’s leaders “separatists.” Beijing has employed increasingly diverse economic, diplomatic, and political tools to pressure Taiwan, including efforts to shrink its “international space.” These measures include suspending official cross-Strait communication channels, getting nine of Taiwan’s few remaining official diplomatic allies to switch recognition from the ROC to the PRC, exerting economic and diplomatic pressure on Taiwan’s international partners (even subnational governments, businesses, and civil society groups), and cutting off Taiwan’s already limited access to international organizations, even to those with which Taipei was previously able to engage (e.g., the World Health Organization).

In short, the global headline-generating, unprecedentedly large-scale PLA maneuvers each of the past three years are but the most conspicuous evidence of a new, more potentially incendiary normal in Beijing’s efforts to assert its 75-year-old sovereignty claim, and to weaken international support for Taiwan. Summing up the years-long trend in the weeks after the PLA’s August 2022 exercises, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken highlighted a “change in the approach from Beijing toward Taiwan,” including “a fundamental decision that the status quo was no longer acceptable and that Beijing was determined to pursue reunification on a much faster timeline” (Washington Post 2022). This assessment came nearly a year after Biden’s Pentagon had already identified “a Taiwan contingency” as its “pacing scenario” (Ratner Reference Ratner2021). Against this precarious backdrop and following the DPP’s victory in January 2024’s presidential election – its third in a row – the possibility of a peaceful, uncoerced resolution of the cross-Strait dispute appears increasingly remote.

Recognizing this reality, as well as the changing balances of power across the Strait and wider region, an important feature of the Biden administration’s Asia policy has been an unprecedentedly proactive effort to enlist key democratic U.S. allies and partners in a coordinated campaign to publicly emphasize “the importance of peace and stability across the Taiwan Strait as an indispensable element in security and prosperity in the international community,” and to call for both “peaceful resolution of cross-Strait issues” and Taiwan’s “meaningful participation” in international organizations (e.g., G7 2023a). This effort is consistent with Biden’s more general emphases on the importance of U.S. alliances – which he identified in his first major foreign policy speech as the U.S.’ “greatest asset” – and the need “to rally the nations of the world to defend democracy globally [and] to push back … authoritarianism’s advance” (White House 2021a). It also reflects a sober judgment that the global fallout from any conflict across the Taiwan Strait would be profound. As an early signal to even geographically distant allies and partners of the wide-ranging stakes, the U.S. National Security Council’s top Indo-Pacific official stressed that a conflict would “broaden quickly and … fundamentally trash the global economy” (Nikkei Asia 2021).

1.2 High Stakes in the Taiwan Strait

From Beijing’s perspective, the question of how to settle Taiwan’s ambiguous international status and incorporate it into the PRC – the heart of the “One China” issue – has long been the most fundamental in China’s foreign and security policy. Seventy-five years after the PRC’s 1949 establishment, its leaders continue to identify Taiwan as being “at the heart of China’s core interests.” They identify “resolving the Taiwan question and realizing China’s complete reunification” as “indispensable for the realization of China’s rejuvenation” and the CCP’s “historic mission.” And they have long asserted that the cross-Strait dispute is “purely an internal matter for China,” regularly warning Washington and others that “the Taiwan question is growing into the biggest risk in China-U.S. relations,” one that “if mishandled could severely damage bilateral ties” (State Council Reference Council2022; Wang Reference Wang2022).

Global reactions to the recent worsening of cross-Strait frictions demonstrate that U.S. government is not alone in expressing its concerns about these trends, and about Taiwan more generally. As detailed in Sections 3 and 4, many other U.S. allies’ leaders – especially in the Western Pacific and Europe – have become increasingly outspoken about their nations’ interests in continued peace and stability across the Taiwan Strait, as well as their support for Taiwan’s international space. There is also more general recognition of the potentially catastrophic implications of a war or coerced resolution to the cross-Strait dispute for Taiwan’s twenty-three million people and its nearly one million foreign residents.

Also attracting unprecedented attention in foreign capitals have been the potentially immense global economic consequences of a Taiwan Strait contingency. Roughly 50 percent of global container traffic flows through the Taiwan Strait daily. Taiwan is the world’s sixteenth largest trading economy, a technological powerhouse, and the source of the vast majority of the world’s most advanced semiconductors. It is also a top-ten trading partner of the United States and a top-five trading partner of China, Japan, and South Korea. For these reasons, one widely referenced 2022 analysis estimates that even a non-kinetic blockade of Taiwan – that is, one not involving direct physical or deadly force – would cause “well over two trillion dollars” in global economic disruption, “even before factoring in international responses or second-order effects” (emphasis added). It concludes that the consequences “would be felt immediately and … difficult to reverse” (Vest, Kratz, and Goujon Reference Vest, Kratz and Goujon2022).

If the crisis were to escalate, possibly to involve direct conflict between China and the United States, the regional and global fallout could be even more catastrophic. A 2024 Bloomberg analysis estimated that the global economy would suffer a $5 trillion hit if the PRC blockaded Taiwan, whereas a shooting war would deal a $10 trillion blow – an amount equivalent to 10 percent of global GDP and which would dwarf the impact of both the 2009 Global Financial Crisis and 2020 COVID-19 pandemic (Bloomberg 2024a).

1.3 Beyond the U.S.-PRC-Taiwan “Triangle”

Behind these estimates is a widespread expectation that Washington, for many decades Taiwan’s most important international partner and de facto security guarantor, is unlikely to stand idly by if a cross-Strait crisis were to escalate. As summarized in Section 2, Washington’s long-standing official policy holds that Taiwan’s status remains “undetermined” and the cross-Strait dispute must be resolved peacefully through dialogue. Furthermore, while U.S. policy leaves ambiguous how it would respond if China attacked Taiwan, a 1979 law obligates the government to provide defensive arms to Taiwan and maintain the U.S. ability to “resist” any use of force or coercion that threatens Taiwan’s security, inter alia (“Taiwan Relations Act” 1979).

Though the United States is undoubtedly Taiwan’s most significant international partner, the urgency with which the Biden administration has sought to more robustly engage U.S. allies in support of Taiwan reflects increasingly mainstream recognition of their agency and significance, especially against the backdrop of China’s rapidly expanding military capabilities and diplomatic and economic influence. For example, Blinken warned Beijing that U.S. allies would “take action [if Beijing seeks] to use force to disrupt the status quo” (Reuters 2021a). At the 2023 G7 summit, Biden himself stated that “We’re going to continue to put Taiwan in a position that they can defend themselves. And there is clear understanding among most of our allies that, in fact, if China were to act unilaterally, there would be a response” (White House 2023a).

In response to these developments and as an apparent effort to preemptively deter such an outcome, throughout 2024 Beijing issued a series of thinly veiled threats against U.S. allies. For example, in April remarks that echoed comments in other allied capitals from Chinese diplomats, PRC Ambassador to Japan Wu Jianghao told a Japanese audience: “If Japan ties itself to the tanks plotting to split China, the Japanese people will be brought into the fire. These are painful words to hear, but they need to be clearly stated. The Japanese should not say that they were not informed in advance” (PRC Embassy Japan 2024).

Against the backdrop of a rapidly changing balance of power, high-profile assertions by U.S. leaders that U.S. allies would respond in a crisis, and the increased frequency and volume of rhetorical backlash from Beijing, it is important for academic and policy debates regarding the Taiwan Strait to move beyond the U.S.-centric bias and narrow focus on the U.S.-PRC-Taiwan triangle that has long dominated. In particular, it is necessary to devote greater attention to major democratic U.S. treaty allies’ agency and the impact that their diverse histories, positions, and policies have had on Taiwan’s international space, cross-Strait peace and stability, and the effective meaning of “One China” in international politics.

1.4 Countering the Spread of Dis/misinformation

The decades-old U.S.-centric bias is a concern not only for the academic literature but also for the health of front-burner political and policy debates in Washington and allied capitals today. As highlighted in Section 2, widespread unfamiliarity with the history and subtleties of issues related to Taiwan and the Taiwan Strait among new generations of leaders has enabled Beijing’s disinformation campaigns – which typically ignore the nuances and intentional ambiguities of the U.S. and key allies’ respective “One China” policies in favor of a narrative falsely claiming a “universal consensus” about its claim of sovereignty over Taiwan – to find strikingly fertile ground in which to take root. For example, Beijing frequently attempts to unilaterally define for the United States and its major allies what their respective positions on Taiwan’s status are, as well as what words or actions constitute a “violation” of their alleged past “commitments.” More generally, it promotes revisionist histories of United Nations Resolution 2758 (1971), which granted “China’s” seat to representatives from the PRC, falsely asserting that this resolution was somehow the final word from the international community on Taiwan’s legal status or whether it is part of China. It was not. In fact, the text of the resolution does not even mention “Taiwan” or “the Republic of China” (Drun and Glaser Reference Drun and Glaser2022).

Beyond politically motivated disinformation, many otherwise well-intentioned commentaries unknowingly spread false or misleading narratives, muddling or ignoring the intentional ambiguity baked into the U.S. and its major allies’ official positions. For example, in September 2022 the U.S.’ most prestigious, highly viewed nonpartisan news magazine show – 60 Minutes – erroneously told over ten million live broadcast viewers that “US policy since 1979 has been to recognize Taiwan as part of China.” Many millions more around the world were subsequently exposed to this misleading claim after the clip seeded global headlines for containing a statement from Biden widely interpreted to constitute a pledge to defend Taiwan if China attacks (CBS News 2022). In recent years, many analysts seem just as likely to falsely equate U.S. allies’ official positions on Taiwan’s status with Beijing’s “one-China principle” as to reiterate poorly substantiated assertions that key allies are radically transforming their positions and policies vis-à-vis Taiwan. For example, since 2021 numerous commentaries have falsely asserted that famously cautious and constitutionally constrained Japan is now more explicitly committed Taiwan’s defense than even the United States itself (Liff Reference Liff2022a).

In short, with unprecedented global attention on Taiwan and the Taiwan Strait, the noise:signal ratio about U.S. allies’ diverse approaches – past and present – is unsettlingly high. As U.S. leaders assert solidarity among allies and concerns about the Taiwan Strait have surged to the point that the 2023 G7 summit statement “call[s] for a peaceful resolution of cross-Strait issues” and (vaguely) asserts that “There is no change in the basic positions of the G7 members on Taiwan, including stated one China policies” (G7 2023b), greater clarity on what key allies’ positions and policies actually are is essential. Careful historical baselines and a well-considered analytical framework with which to assess recent developments across numerous cases are also needed.

In an earlier, more halcyon era of increasing cooperation and engagement both across the Strait and between Beijing and Washington, an insular focus on the U.S.-PRC-Taiwan triangle was understandable, though still problematic. Given highly volatile contemporary realities, however, it is increasingly ill-advised. Though the agency of and decisions by Beijing and Taipei are of course fundamental, and beyond the Strait Washington has a singularly important role to play, the agency and significance of U.S. allies have for too long been excessively discounted or ignored altogether. U.S. allies’ choices have always been, and will remain, important variables affecting Taiwan’s international space, peace and stability across the Taiwan Strait, and the course a conflict could take if deterrence fails.

1.5 Bringing U.S. Allies Back In

This Element surveys the respective origins and evolutions of the positions, effective policies, and stated interests concerning Taiwan and the Taiwan Strait of six major democratic U.S. treaty allies and the European Union. It also briefly highlights a foundational contribution from a seventh ally – Canada – and several recent related developments concerning the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), of which the United States, Canada, and other key European treaty allies are founding members. This study’s extensive empirical survey contributes to academic literatures and policy debates by highlighting the consequential but oft-overlooked roles played by U.S. allies past, present, and potentially future. Furthermore, its original comparative analysis sheds light on key issues impossible to descry from single case-centric approaches. Two contributions are particularly noteworthy:

1.5.1 Highlighting U.S. Allies’ Agency, Trailblazing, and Significance Historically and Today

Much of the decades-old U.S.-centric academic and policy-oriented literatures regarding Taiwan- and Taiwan Strait-related issues has treated the agency, positions, and policies of key U.S. allies as an afterthought, if not neglecting them entirely. This oversight matters for two primary reasons: First, Beijing’s increasingly coercive posture vis-à-vis Taipei and a rapidly changing balance of power today all but guarantee that several major U.S. treaty allies (e.g., Japan) and economic partners (e.g., the EU) are and will continue to be essential partners for Taipei and Washington in achieving core strategic and policy objectives. Accordingly, understanding where these governments stand on key issues, as well as what they have been willing to do and say over time in support of Taiwan and the cross-Strait status quo, has real-world implications for policy.

Second, overlooking the agency and significance of U.S. allies is also profoundly ahistorical. Contrary to the widespread impression today that the U.S. has always been in the lead, with allies grudgingly following (or not), throughout the post-1949 period Western Pacific and European allies made significant contributions to enabling Taiwan’s international space and cross-Strait peace and stability even as they sought to develop ties with the much larger PRC. Importantly, they have done so variably in concert with and independently from the United States – at times even over Washington’s direct opposition. At critical historical moments now often forgotten, allies’ political leaders effectively blazed trails that the U.S. would later follow.

Not only did most major U.S. democratic treaty allies switch official diplomatic recognition from the ROC to the PRC many years before Washington did. As the case studies in Sections 2–4 demonstrate, it was also a major U.S. ally – not the U.S. government – that first implemented each of several measures designed to square the difficult circle of establishing diplomatic relations with Beijing while supporting continued engagement with Taiwan and cross-Strait peace and stability. Of particular note: it was a U.S. ally that first (1) recognized the PRC government without endorsing Beijing’s sovereignty claim over Taiwan and (2) negotiated a bilateral communique with Beijing that avoided any mention of Taiwan. And it was also a U.S. ally that, even after switching official diplomatic recognition from the ROC to the PRC, first (3) linked recognition of Beijing to “peaceful resolution” of the cross-Strait dispute; (4) implemented the “do not endorse, do not challenge” framework that later became the heart of the U.S. position on “One China”; (5) insisted on a de facto representative office in Taipei; (6) initiated robust engagement with KMT leaders through legislative exchanges that functioned as stand-ins for direct high-level government-to-government engagement; (7); sent a cabinet-level official to Taipei; (8) allowed a visit by a sitting ROC foreign minister.

1.5.2 Highlighting the Politically Contingent Variability of Allies’ Effective Taiwan Policies

This study also adopts a unique comparative approach. It reveals important variation across and within cases concerning how political leaders have chosen to operationalize “unofficial” relations with Taiwan, including how to speak publicly about or act in support of Taiwan’s international space or cross-Strait peace and stability. This analysis helps reveal the under-appreciated ambiguity, dynamism, and political contingency at the heart of the “One China” framework that for decades has shaped the contours of the U.S. and many of its allies’ approaches. Short of a widely understood red-line – official recognition of the ROC/Taiwan as a sovereign state – the empirical record across these cases reveals that a country’s “One China policy” is, as far as official rhetoric regarding and practical engagement with Taiwan is concerned, largely whatever government leaders choose to make of it.

The diversity of effective Taiwan policies even among the United States and its closest democratic treaty allies revealed by this comparative approach throws into sharp relief the strikingly weak correlation between a government’s abstract, usually static, official position on “One China” (form) and its effective official policies and rhetoric regarding Taiwan and the Taiwan Strait (substance). In any practical sense, even after recognizing Beijing major allies’ effective policies on Taiwan-related matters have varied widely, with significant real-world implications for Taiwan’s international space and cross-Strait vicissitudes.

Importantly, this variation manifests both across and within the cases examined in this Element. Regarding the former, even ally and partner governments adopting identical – or nearly identical – official positions on “One China” have engaged in widely divergent conduct in terms of bilateral engagement with or public expressions of support for Taiwan and/or cross-Strait peace and stability. Concerning the latter, despite the general contemporary trends among major U.S. democratic allies and partners toward closer unofficial ties with Taipei and greater outspokenness regarding Taiwan’s international space and the Taiwan Strait, history suggests that these trends are not inevitably linear or unidirectional. Several case studies reveal that shifting domestic and international political winds have intermittently caused some political leaders to reevaluate the pros and cons of more robust engagement with and outspokenness concerning Taipei, and to adjust their approaches accordingly.

In aggregate, the case studies introduced in Sections 2–4 highlight the underappreciated and immense historical significance of U.S. allies’ positions and policies vis-a-vis Taiwan: for Taiwan itself, for cross-Strait dynamics, and even for the U.S.’ own positions and policies. They also highlight their practically consequential variability – across and within cases.

1.6 A New Era for U.S. Allies and the Taiwan Strait?

Concomitant with the worsening of relations between Beijing and Taipei, as well as between China and the United States and many of its allies, recent years have witnessed unprecedented multilateralization and internationalization of concerns about “peace and stability across the Taiwan Strait,” calls for “peaceful resolution of cross-Strait issues,” and support for Taiwan’s democracy and “meaningful participation” in the international community.

This contemporary trend manifests in manifold ways. Most conspicuous is the recent proliferation of official rhetoric appearing in high-level unilateral, bilateral, and multilateral statements from U.S. allied governments, resolutions passed by national parliaments, and exchanges of legislators. Several allies show newfound (or rediscovered) willingness to conduct naval transits through the international waters of the Taiwan Strait, and/or quietly share dual-use (military + civilian) and other technologies with Taiwan. Meanwhile, especially since 2022 witnessed Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine and the PLA’s massive exercises around Taiwan, various indicators suggest a sharp uptick in discussions among the U.S. and its allies about military and/or economic contingency plans in the event of a cross-Strait crisis.

Recent developments also demonstrate that many U.S. allies increasingly recognize their own national interests and agency in cross-Strait peace and stability. Regardless of each government’s ability to project substantial military power to the area surrounding Taiwan – extremely limited in most cases outside the Western Pacific – their economic and financial tools are highly salient. Not only do the United States and its democratic treaty allies account for eight of the world’s ten largest economies (China and democratic India round out the list), four of Beijing’s top five trading partners in 2022 were the EU (#1), of which the largest national economies are all U.S. treaty allies; Japan (#3); South Korea (#4); and Germany (#5). The other (#2) is the United States itself (Haiguan Zongshu Reference Haiguan2023). Accordingly, the potential to shape Beijing’s behavior of even distant U.S. European allies, and the EU itself, should not be dismissed. Even in the military domain, U.S. NATO allies could make a significant indirect contribution in peacetime or a crisis by adjusting their deployments and mission sets to make it easier for the U.S. military to prioritize the Western Pacific. In short, U.S. allies possess substantial potential capability and leverage, regardless of geography.

1.7 Overview of the Element

This Element aims to introduce readers to key issues related to U.S. allies and the Taiwan Strait, and to do so in a manner widely accessible for scholars, policymakers, students, and the public.

Section 2 gives readers a crash course in the basic history of the post-1949 disputes over “One China” and Taiwan’s status at the heart of contemporary cross-Strait frictions. It highlights the critically important but widely misunderstood distinction between Beijing’s self-defined “one-China principle,” which asserts that Taiwan belongs to the PRC, and the U.S. and other major allies’ “One China” policies, which today generally neither endorse nor challenge the PRC’s sovereignty claim. Highlighting Canada’s innovative 1970 framework and using the famously consequential case of U.S. Taiwan policy after 1979 as an illustrative example, this section also introduces the study’s basic analytical framework. This framework aims to elucidate not only allied governments’ abstract official positions on Taiwan’s status but also how their political leaders have sought to operationalize that position in practical terms: that is, through their effective policies and rhetoric vis-à-vis Taiwan and the Taiwan Strait.

Sections 3 and 4 apply the aforementioned analytical framework to an original empirical survey of the post-1949 histories and evolution of six major democratic U.S. treaty allies’ positions, perspectives, and policies vis-à-vis Taiwan/the Taiwan Strait. These case studies focus on the U.S.’ most wealthy, economically advanced and militarily capable allies in the Western Pacific and Western Europe. Not coincidentally, these are also the half-dozen U.S. allies who trade the most with China. Listed in chronological order of each government’s decision to recognize the PRC, the former cases are Japan (1972), Australia (1972), and South Korea (1992). The latter cases are the United Kingdom (1950)Footnote 1, France (1964), and Germany (1972). Section 4 additionally examines two important, but unique, non-nation-state cases: the EU (1975) and NATO.

Collectively, these case studies demonstrate the diversity and variability of U.S. allies’ approaches to Taiwan, past and present. They reveal their significant historical agency, as well as the extent to which Beijing’s increasingly coercive posture and assertion of its preferred narrative on “One China” today are generating an unprecedented international reaction and alignment of allied rhetoric and policy, even in far-off Europe, the long-term implications of which remain to be seen.

Each ally/partner case study first introduces the government’s foundational position on “One China” – including on the critical question of whether upon recognizing the PRC the government endorsed Beijing’s claim of sovereignty over Taiwan.Footnote 2 It then briefly summarizes post-normalization approaches to Taiwan and the Taiwan Strait, with a particular focus on (a) the extent and nature of engagement with Taiwan and support for its international space and (b) official statements and policies as it relates to cross-Strait frictions.

These eight brief case studies aim to cut through the U.S.-centrism and abstract and often misleading talk of “principle” that permeates the discourse. Instead, they highlight the practical reality of significant variability and dynamism in major democratic U.S. treaty allies’ policies toward Taiwan both across cases and within them (i.e., over time). Collectively, they demonstrate that a government’s effective Taiwan policy can be, but is not necessarily, dynamic – even if its official decades-old position on “One China” is frozen in time. It can shift subtly and/or significantly in response to the vagaries of PRC policies toward Taiwan or its leaders’ evolving assessments of national interests and domestic and international political dynamics.

Sections 5 and 6 summarize major takeaways. In aggregate, this study’s findings challenge conventional understandings of a key issue in East Asian international relations. Although Washington has always been and is almost certain to remain both Taiwan’s most important international partner and the primary external player in cross-Strait deterrence, major democratic U.S. allies (and the EU) have long had, and continue to have, major roles to play. Looking ahead, a rapidly changing balance of power and influence ensures that U.S. allies’ policy choices will remain crucial variables affecting Taiwan’s and U.S. policy options in both peacetime and a potential crisis.

Recent developments make clear that today, arguably for the first time, peace and stability across the Taiwan Strait are widely considered a common challenge for the United States and its major democratic treaty allies in the Western Pacific and Europe. As such, it is critically important that scholars, policymakers, students, and citizens better understand the past and present evolution of U.S. allies’ intentionally nuanced positions and policies vis-à-vis Taiwan and the “One China” question.

2 “One China” and the Taiwan Strait: The Distinction between Beijing’s “Principle” and the U.S. and Allies’ “Policies”

In the United States’ relations with both China and Taiwan, the verbal formulations used to describe policy are more important than perhaps in any other foreign policy relationship. Indeed, words themselves become policy.

The ostensible trigger for the PLA’s unprecedentedly large-scale August 2022 military exercises – a long-postponed and mostly symbolic visit to Taipei by outgoing U.S. Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi – was revealing on multiple levels. As important as the advanced military capabilities Beijing demonstrated were the assumptions outside the PRC that gave the crisis its meaning internationally: above all, that many believed Beijing might risk a catastrophic war over its claim to Taiwan.

As told by Beijing, the PRC’s furious response was due to Pelosi’s alleged violation of past U.S. commitments to its “one-China principle.” As detailed below, an essential component of this “principle” – as Beijing defines it – is that self-governed, democratic Taiwan, which the PRC has never ruled, belongs to it. Accordingly, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) called Pelosi’s visit to “China’s Taiwan region … a serious violation of the one-China principle and … a seriously wrong signal to the separatist forces for ‘Taiwan independence’” [emphasis added]. Beijing further asserted its unilateral interpretation of U.S. policy, stating that “Congress, as a part of the U.S. Government, is inherently obliged to strictly observe the one-China policy of the U.S. Government and refrain from having any official exchanges” (MFA(PRC) 2022). Beijing frequently makes similar claims about U.S. allies. For example, following each of a series of recent visits to Taipei by German parliamentarians, the PRC Embassy in Berlin asserted: “The German side is not allowed to have any official contacts with Taiwan, and that also applies to German parliamentarians. This principle is part of the One China policy” (e.g., Anadolu Agency 2023).

Beijing has for decades also claimed that the U.S. and all other foreign governments having diplomatic relations with the PRC “recognize that there is only one China and that the government of the People’s Republic of China is the sole legal government of China and Taiwan is part of China” (State Council Reference Council1993). Today, it frequently asserts that a “universal consensus” exists in the international community in support of Beijing’s “one-China principle” (MFA(PRC) 2020).

Yet, such claims are best understood as self-interested and misleading propaganda, not historical fact. For starters, no leader in Taiwan endorses Beijing’s claim that Taiwan is PRC territory. Nor do the dozen foreign governments that still recognize the ROC as a sovereign state. Most importantly for this study, and notwithstanding Beijing’s unilateral assertions to the contrary, Washington and its major democratic treaty allies did not endorse Beijing’s claim of sovereignty over Taiwan upon recognizing the PRC.

Today, as China’s frictions with the United States and its major democratic allies worsen and Beijing more brazenly tries to define for them what their “One China” policies are, both Taiwan’s status and the very “rules” governing the “One China” framework’s operation in international politics are becoming increasingly contested, and publicly so (Liff and Lin Reference Liff and Lin2022). Rare public pushback from the German Foreign Office in 2022 against Beijing’s repeated misrepresentations of German policy was one remarkable demonstration that the distinction between the PRC’s “principle” and other foreign governments’ policies is not a matter only for U.S.-China relations. Rather, it is also fundamental to major U.S. allies’ approaches. In strikingly candid prepared remarks, a senior German Foreign Office official stated, “We steadfastly reject [Beijing’s term “one-China principle”] and the notion behind that. [sic] We have our One China policy … But, it is us who have devised this policy and it is us who interpret this policy – no one else” (Thümmel Reference Thümmel2022).

This section has two primary goals: (1) to concisely summarize for readers the history of the “one-China principle,” its international contestation, and the broad contours of U.S. Taiwan policy, and (2) to introduce the study’s analytical framework that the latter inspires. In service of these objectives, the remainder of this section is divided into four sections: The first section summarizes the “One China” idea as it has manifested across the Taiwan Strait since Chiang Kai-shek and his Nationalist Party (KMT) in 1949 fled the mainland for Taiwan after their defeat in the Chinese Civil War. The next section introduces the concept of the “One China” framework and its significance in international politics. The penultimate section reviews key pillars of the U.S.’ famously ambiguous “One China” policy to highlight for the reader two major points: First, the U.S.’ position regarding Taiwan’s status is fundamentally distinct from Beijing’s “one-China principle,” which the U.S. government does not endorse. Second, this ambiguity has granted U.S. political leaders considerable latitude to support both cross-Strait stability and “robust unofficial relations” with Taiwan – despite the absence of official diplomatic relations with Taipei since 1979. Using the best-known U.S. case as inspiration, the section closes by introducing the two-step analytical framework employed in the allied case studies in Sections 3 and 4.

2.1 The “One-China Principle(s)” and the Post-1949 Cross-Strait Dispute

Scholars have long considered the question of how to settle Taiwan’s ambiguous international status the most fundamental question in China’s foreign and security policy. China’s leaders agree. For instance, the PRC’s ambassador to the UK repeated a common refrain when he warned in August 2022 that Beijing’s “one-China principle” is the “political foundation for the development of relations between China and all countries in the world” (The Guardian 2022a). As this statement makes clear, the issue is not merely of concern to the governments on both sides of the Taiwan Strait. Rather, it has been a defining issue in both the PRC’s and Republic of China’s (ROC) foreign relations since 1949 – especially in dealings with the United States and its major democratic treaty allies.

The 1949 CCP victory in the Chinese civil war led to three major outcomes most relevant to this study. First, Mao Zedong declared the establishment in Beijing of a new CCP-led People’s Republic that believed itself to have “replaced the previous KMT regime” as the sole legal successor state of the ROC and “the only legitimate government of the whole of China,” including Taiwan (State Council Reference Council2022). Second, after fleeing to Taiwan, Chiang proclaimed Taipei the ROC’s new “provisional” capital, while simultaneously declaring his intent to eventually reestablish ROC control over the mainland. Third, the KMT’s authoritarian government denied the Taiwan-born majority living in Taiwan at the time a chance at self-determination. From 1949 until the 1980s, the period during which the United States and most major allies formalized their official positions on “One China,” the KMT used its fear of a communist insurgency and claim to be the government of all of China to justify martial law and at times brutal oppression in Taiwan.

In short, after 1949 the cross-Strait status quo was effectively frozen, with a KMT-led ROC government in Taipei and a CCP-led PRC government in Beijing. Each side considered the other illegitimate and vowed to “reunify” Taiwan and the mainland under their party’s control. The net result was single-party authoritarian governments on both sides of the Taiwan Strait – both run by elites born on the mainland and both making mutually irreconcilable claims to be the sole legitimate government of a China that included the mainland and Taiwan.

2.1.1 Origins and Cold War Manifestations of “One China” across the Taiwan Strait

Although some historical records suggest that key CCP and KMT leaders did not even consider Taiwan part of China before the 1940s, by 1949 the political meaning and significance of Taiwan for both sides had fundamentally changed. The idea that Taiwan was “inherent Chinese territory” had become nonnegotiable (Hsiao and Sullivan Reference Hsiao and Sullivan1979; Wachman Reference Wachman2007, chaps. 4–5).

The concept of “One China” originated internationally in opposition to two alternatives for resolving the post-1949 cross-Strait dispute, both anathema to PRC and ROC leaders during the Cold War: “two Chinas” (liang ge Zhongguo), which envisioned the international community recognizing the legitimacy of both the PRC and ROC, and “one China, one Taiwan” (yi Zhong yi Tai), which envisioned the international community recognizing Taiwan as an independent state disconnected from both the PRC or ROC regimes.

In theory, Taiwan’s legal status could have been resolved after 1945 during the negotiations over a peace treaty with Japan – Taiwan’s colonial occupier from 1895 to 1945. However, different views among the allies concerning which to invite meant neither the PRC nor the ROC government was represented at the 1951 San Francisco Conference. The text of the resulting treaty stated only that “Japan renounces all right, title and claim to Formosa and the Pescadores.” Critically, it said nothing about to which entity sovereignty over them was subsequently transferred (“Treaty of Peace with Japan” 1951). Nor was this ambiguity explicitly resolved in Japan’s subsequent peace treaties with the ROC (“Treaty of Peace”1952) and PRC (“Treaty of Peace and Friendship” 1978).

After North Korea’s (PRC-supported) invasion of South Korea in June 1950 threw into sharp relief the risk of a hot war of unification in East Asia, U.S. President Truman stated that Taiwan was not yet part of China and should be considered an issue of continuing international concern, and that the people on Taiwan should have some say in their future. The U.S. continued to recognize the ROC government – a UN founding member state – but, importantly, did not recognize its “ownership of the island” (Bush Reference Bush2004, 95). Generally speaking, the United States, the UK, and other key U.S. allies either judged that Taiwan’s status remained “undetermined” or avoided publicly taking any explicit legal position on Taiwan’s relationship to the PRC. Unsurprisingly, both the PRC and ROC governments took issue with these positions, instead claiming sovereignty over Taiwan for themselves.

Although in policy discourse today the “one-China principle” is generally associated with the PRC’s claim of sovereignty over Taiwan, to understand how the contemporary status quo came to be one must not forget that throughout the Cold War the ROC government in Taipei also enforced its own version of the “one-China principle.” In the view of Chiang’s KMT, it was the ROC, not the PRC, that was the sole legitimate government of a single “China” including both Taiwan and the mainland.

Given the two sides’ irreconcilable “one-China principles,” throughout the Cold War all foreign governments had to make a choice: recognize either the PRC or the ROC as China’s sole legal government. Accordingly, and of profound historical and contemporary significance, both Beijing and Taipei repeatedly rejected efforts before 1971 by the United States, the UK, Japan, Canada, and other foreign governments to explore possibilities for a “two Chinas” or a “one China, one Taiwan” solution. As Bush points out, the world will never know whether, if the KMT had been more receptive to the U.S. and others’ efforts to facilitate dual presence in the UN for both the PRC and ROC, Taiwan “might still be represented in international organizations today” (Reference Bush2004, 120).

Two major turning points in the history of the “one-China principle” were particularly consequential internationally. The first – in the 1970s – witnessed a cascade of foreign governments switching official recognition from the ROC to the PRC. Two major catalysts were U.S. President Richard Nixon’s surprise July 1971 announcement of his intent to visit the PRC, which signaled a historic rapprochement between Washington and Beijing, and, three months later, a resolution granting PRC representatives seats in the UN Security Council and General Assembly and expelling “the representatives of Chiang Kai-shek.” Between 1970 and 1973, dozens of foreign governments recognized the PRC, including U.S. allies Canada, Italy, Japan, (West) Germany, Australia, and New Zealand. (The UK, which had recognized the PRC in 1950 but not yet established full diplomatic relations, also exchanged ambassadors with Beijing for the first time.) The consequences for the ROC’s international recognition were profound: in accordance with the two sides’ irreconcilable “one-China principles,” all these foreign governments either severed, or saw Taipei sever, diplomatic relations.

2.1.2 Taiwan’s Democratization and Its Impact

The second major turning point occurred in the late 1980s and 1990s, a period which witnessed both the Cold War’s end (1989–1991) and Taiwan’s rapid democratization after four decades of martial law and single-party KMT rule. Democratization gave the long-oppressed Taiwan-born majority a central role in Taiwan’s politics, including greater influence over Taiwan’s complicated relationships with both the mainland and the “One China” concept itself. The consequences for cross-Strait relations were profound.

The first breakthrough occurred under KMT President Lee Teng-hui (1988–2000) – the ROC’s first Taiwan-born, first post-martial law, and, after 1996, first democratically elected leader. In 1991, the ROC government declared the end of the Period of Mobilization against Communist Rebellion, effectively ending the Chinese civil war from Taipei’s perspective and identifying the PRC as an “equal political entity” with which it could engage. It also recognized that the government in Taipei effectively controls only the islands of Taiwan, Penghu, Kinmen, and Matsu, while the PRC government exercises authority over mainland China (Chen Reference Chen2022, 1031–32; Somers Reference Somers2023, 693). This facilitated cross-Strait contacts and economic linkages, as well as massive investment from Taiwan into the mainland. Later, as a clear indication of generational change and increasingly open political contestation within rapidly democratizing Taiwan regarding “One China,” in 1999 Lee publicly referred to Taiwan and the mainland as having “special state-to-state relations.” His successor, Taiwan’s first DPP president, Chen Shui-bian (2000–2008), took such rhetoric even further. Chen, who was also Taiwan-born, referred to “one country on each side” (of the Strait) (Chen Reference Chen2022, 1033). He even pursued a controversial referendum on Taiwan’s UN membership. Such moves, widely seen as flirting with a unilateral declaration of de jure independence – a potential casus belli for Beijing – generated significant blowback, including from the United States and key allies. Based in part on this experience, Taiwan’s second DPP president, Tsai Ing-wen (2016–2024), adopted a more moderate, status quo–oriented stance. Her successor, William Lai (2024–), says that he plans to follow suit.

Beyond the consequences for cross-Strait relations, the implications of Taiwan’s democratization for more flexible engagement with foreign governments were also significant. The era of Taipei’s rigid assertion of the KMT’s version of the “one-China principle” internationally was effectively over. In 1989, the ROC for the first time allowed a foreign government (Grenada) to normalize diplomatic relations without requiring it to sever diplomatic ties with the PRC (Mengin Reference Mengin1997, 240).

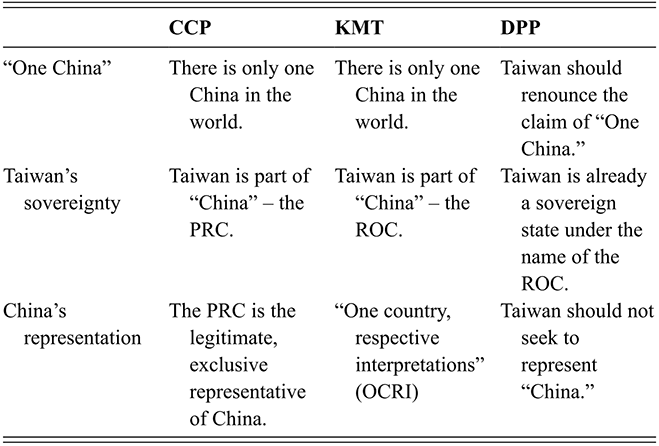

Thus, when reflecting on the origins of the U.S. and its allies’ decades-old positions on “One China,” one should not forget that throughout the Cold War both the PRC and ROC governments actively enforced their respective positions that Taiwan is part of one “China.” Both considered any proposal to treat it as anything but unacceptable, thereby forcing a choice on all foreign governments. In contrast, today, only the PRC actively enforces a version – its version – of the “one-China principle” internationally. Though differences today between Taiwan’s major political parties on cross-Strait issues are significant, none accepts Beijing’s contention that the ROC/Taiwan is part of, or subordinate to, the CCP-led PRC (see Table 1).

| CCP | KMT | DPP | |

|---|---|---|---|

| “One China” | There is only one China in the world. | There is only one China in the world. | Taiwan should renounce the claim of “One China.” |

| Taiwan’s sovereignty | Taiwan is part of “China” – the PRC. | Taiwan is part of “China” – the ROC. | Taiwan is already a sovereign state under the name of the ROC. |

| China’s representation | The PRC is the legitimate, exclusive representative of China. | “One country, respective interpretations” (OCRI) | Taiwan should not seek to represent “China.” |

Although under KMT President Ma Ying-jeou (2008–2016) Taiwan significantly deepened cooperation with Beijing based on the KMT’s and CCP’s shared conviction that there is only one “China” and Taiwan belongs to that “China,” the fundamental disagreement between the two parties regarding to which “China” (ROC vs. PRC) Taiwan belongs persists. Whereas the KMT openly acknowledges this reality based on the formula of “one country, respective interpretations,” the PRC does not (Chen Reference Chen2022, 1034–35; Somers Reference Somers2023, 695–96). As noted earlier and summarized in Table 1, the party of Ma’s DPP successors has a very different view, even as both Presidents Tsai and Lai have adopted a moderate stance in office.

Beyond the Strait, one major consequence of Taiwan’s democratization and its leaders’ post–Cold War shifts toward greater flexibility and pragmatism on “One China” was to further expand space for the U.S. and its democratic treaty allies to, in the words of Klintworth, “stretch the principle of one China into the reality of a one China, one Taiwan policy” (Reference Klintworth1993, 87–90). The past three decades have witnessed deepening economic and other ties across the Taiwan Strait, an increasingly robust “Taiwanese” identity within Taiwan, and a major expansion of foreign governments’ “unofficial” engagement with Taipei. Even so, support for the “status quo” remains widespread (Election Study Center 2024).

2.2 The Contested “One China” Framework Internationally: Intentionally Ambiguous and Politically Contingent

Upon recognizing the PRC as the “sole legal government of China,” neither the United States nor any major democratic U.S. ally endorsed Beijing’s claim of sovereignty over Taiwan. In the decades since, each country’s leaders have made a series of political decisions about how to operationalize their intentionally vague position on the sovereignty question in terms of concrete policies and bilateral engagement with Taipei and on cross-Strait issues. Not based upon any explicit commitment to Beijing, the effective bounds of “appropriate” policies have always been conditioned on international and domestic political vicissitudes, interpreted through political leaders’ complex and evolving calculus of national interest, including the risks of instability.

The events of August 2022 are a case in point. PRC disinformation to the contrary, under its “One China” policy the United States does not commit to “prevent” a sitting Speaker of the house from visiting Taiwan. In fact, Pelosi’s trip was not even the first by a sitting Speaker. Even so, President Biden reportedly discouraged her from making the trip based on the Pentagon’s judgment that “it’s not a good idea.” Pelosi herself even suggested Beijing might shoot her plane down (UPI 2022). Biden’s alleged effort to discourage Pelosi’s visit is an extremely high-profile example of how concerns about Beijing’s reactions – or anticipated reactions – to bilateral engagements with or rhetoric/policies in support of Taiwan often lead to political judgments that are, in effect, self-imposed restrictions. Where the “line” exists is difficult to judge and politically contingent.

2.2.1 The “One China Framework”

Informing this Element’s analytical approach is the idea that the “One China” framework functions in international politics as something akin to what political scientists call an “informal institution” (Liff and Lin Reference Liff and Lin2022). Put simply, U.S. allies’ effective policies toward Taiwan and the Taiwan Strait are contingent on leaders’ interpretations of largely unwritten, socially constructed, and domestically and internationally contested rules that shape “many of the ‘real’ incentives and constraints that underlie [leaders’] political behaviour” (Helmke and Levitsky Reference Helmke and Levitsky2003). Short of the widely understood red line of formal recognition of the ROC/Taiwan as a sovereign state, U.S. allies’ respective “One China” policies are largely what their leaders choose to make them. The caveat, of course, is that certain actions have consequences, and certain moves may elicit Beijing’s wrath. But where even that line is, or how likely Beijing is to back up its often fiery rhetoric with costly punishment, is often unclear.

Far from being based on any legally binding, clearly articulated, or explicit commitment to Beijing, it is subjective and politically conditioned interpretations of what “One China” means in principle and practice – and what their government’s interests are – that determine how political leaders choose to operationalize their respective positions in terms of actual policies vis-à-vis Taiwan. Judgments about where the “appropriate” or “acceptable” bounds on engagement with Taiwan and on cross-Strait issues lie and what policies best serve national interests effectively define the “rules of the game.” Political leaders must decide how proactive (or passive) their respective Taiwan policies should be, and in which domains – economic, cultural, political, military, etc. – they can or should engage Taipei.

No case better illustrates the flexible, politically conditioned bounds of a foreign government’s “One China” policy than that of the United States, Taiwan’s closest international partner and the ROC’s erstwhile treaty ally.

2.3 The Most Famous Case in Point: U.S. “One China” Policy 101

Frequent disinformation and misinformation in contemporary discourse to the contrary, the difference between Beijing’s self-defined “one-China principle” and the U.S. “One China” policy is well-established. In the U.S. case, the term “One China policy” is best understood as encapsulating not only the U.S. official position on “One China” (read: Taiwan’s status), but also how the U.S. engages Taiwan sans official diplomatic ties and in support of Washington’s long-standing position that cross-Strait differences should be resolved peacefully (Bush Reference Bush2017, 18).

Although in the interest of stable relations the U.S. government generally avoids highlighting the distinction between its position and Beijing’s “one-China principle” publicly, there are exceptions – typically in response to PRC disinformation campaigns. In a 2020 speech, for example, Trump administration Assistant Secretary of State David Stilwell criticized Beijing for “distorting” history. He noted that the U.S. “one-China policy … is distinct from Beijing’s ‘One China principle’ under which the Chinese Communist Party asserts sovereignty over Taiwan,” adding that “The U.S. takes no position on sovereignty over Taiwan” (Stilwell Reference Stilwell2020). Following another round of disinformation from Beijing after Pelosi’s 2022 visit, Biden’s State Department released the following statement: “The PRC continues to publicly misrepresent U.S. policy. The United States does not subscribe to the PRC’s “one China principle” – we remain committed to our long-standing, bipartisan one China policy, guided by the Taiwan Relations Act, Three Joint Communiques, and Six Assurances” (@StateDeptSpox 2022).

As this response demonstrates, the U.S. “One China” policy is not defined in a single document or any bilateral agreement or treaty with Beijing. Rather, it is the effective culmination of decades of unilateral statements, modified contact guidelines, three bilateral communiques with Beijing, domestic legislation such as the 1979 Taiwan Relations Act, presidential decisions such as the recently declassified 1982 Six Assurances, and various policies developed and implemented long after the United States officially switched diplomatic recognition from Taipei to Beijing in 1979 (CRS 2015). Far from being static, beyond the abstract question of “One China,” in any practical sense U.S. Taiwan policy has evolved significantly since the 1970s. Indeed, as Bush (Reference Bush2004, 121) noted twenty years ago, “U.S. relations with Taiwan today are far more robust in substance than they are in form … Washington has richer ties with Taipei on an unofficial basis than it does with many countries with which it has diplomatic relations.” Bush’s point is even more compelling today.

An extensive academic literature on U.S. Taiwan policy already exists. So, too, do manifold government documents describing U.S. policy and strategic objectives vis-à-vis Taiwan (American Institute in Taiwan 2022). Accordingly, the following summary serves only to highlight for unfamiliar readers key features of U.S. Taiwan policy and to clarify the basis for the analytical framework applied in Sections 3 and 4 to the lesser-known cases of major U.S. treaty allies.

Of fundamental importance is the following: Upon normalizing relations with Beijing in 1979, the U.S. government recognized the PRC as China’s “sole legal government.” Critically, however, Washington never endorsed the second essential element of Beijing’s “one-China principle”: its claim that Taiwan is part of the PRC. Instead, in the 1979 communique the U.S. government merely “acknowledges the Chinese position that there is but one China and Taiwan is part of China” [emphasis added] (AIT 1979).

In adopting this intentionally ambiguous position, the U.S. embraced a version of the 1970 “Canadian formula.” The rationale for this formula warrants a brief aside, especially because (1) it is the most direct inspiration for the U.S. and many other governments’ official positions on “One China,” and (2) the basic “acknowledge but do not recognize” framework in the 1972 and 1979 U.S.-PRC communiques is widely – but wrongly – considered a U.S. invention.

2.3.1 The “Canadian Formula” (1970)

After becoming prime minister in 1968, Pierre Trudeau launched normalization negotiations with Beijing – over Washington’s opposition. Consistent with Ottawa’s 1950s-era position that Taiwan’s status remained “an undetermined international issue,” however, Canadian diplomats were tasked by Trudeau with “avoid[ing] any commitment that would deny Canada the possibility of recognizing Taiwan as an independent state at some time in the future if circumstances should make that feasible” (Cabinet 1969; Simon Reference Simon2023, 4). Though initially hoping to avoid severing official ties with Taipei altogether, Canada eventually agreed to end de jure recognition of the ROC government. Even so, Canadian negotiators repeatedly rejected Beijing’s demands to recognize the PRC’s sovereignty claim (Frolic Reference Frolic2022, Ch. 2).

In the landmark October 1970 Canada–PRC normalization communique, Ottawa “recognizes” the PRC “as the sole legal government of China” but merely “takes note of” Beijing’s position on Taiwan. As Mitchell Sharp, then Canada’s foreign secretary, explained to the House of Commons, Ottawa intentionally neither “endorsed” nor “challenged” the PRC’s position. Sharp’s contemporaneous exchanges with opposition party leaders elucidate both how the ROC government’s insistence that it represented “all” of China tied Ottawa’s hands and that, despite that fact, Canada still did not endorse Beijing’s sovereignty claim. Asked whether recognition of the PRC meant Ottawa would break off relations with “the government of Taiwan,” Sharp replied, matter-of-factly, that “there is no government of Taiwan.” He added that Ottawa and Taipei agreed that it is “not possible to recognize simultaneously more than one government as the government of China.” A comment from the New Democratic Party’s leader drove home the broad political support for Canada’s non-endorsement of Beijing’s “one-China principle.” After volunteering that he was “very glad” to support Canada’s diplomatic relations with “mainland China,” he added that “when the government of Taiwan is prepared to state that it is the government of that area, and of that area only, it will be time for the Canadian government to negotiate with that government for diplomatic recognition” (House of Commons (Canada) 1970, 49–51).

Thus, in 1970 Canada became the first democratic U.S. ally to mention “Taiwan” explicitly in a normalization communique – a condition imposed by Beijing to avoid a repeat of what happened with France in 1964 (see Section 4). Even so, even the fairly China-friendly Trudeau government refused to endorse Beijing’s sovereignty claim. Thenceforth, the “Canadian Formula” would become the basis for the U.S. and other democratic allies’ future, similarly ambiguous, positions on “One China.” The long-term consequences for Taiwan’s international space and the cross-Strait status quo were profound.

2.3.2 The 1979 U.S. Position

The U.S. government’s limited acknowledgment (and non-endorsement) of the PRC position in its own normalization communique with Beijing nearly nine years after Canada’s amounted to a political (but not legal) commitment not to actively support a “One China, One Taiwan” or “Two Chinas” framework, or a declaration by Taiwan of de jure independence. Importantly, however, the U.S. formula neither endorsed as a goal nor ruled out the possibilities of either (1) eventual unification with the mainland or (2) independence for and U.S. recognition of Taiwan as a sovereign state. It is a policy statement implying that Washington is officially neutral on the negotiated outcome, provided it is reached peacefully by the two sides (Romberg Reference Romberg2003, 35).

Accordingly, core pillars of U.S. policy were (and remain) opposition to the use of force and any unilateral change to the status quo – by either side. In 1982, the Reagan administration reaffirmed that “the United States government takes no position on Taiwan’s sovereignty. We regard this as a matter to be determined by the Chinese people on both sides of the Strait” (Bush Reference Bush2004, 121). More than forty years later, at a November 2023 meeting, Biden reportedly conveyed a similar message directly to Xi Jinping, noting, “We do not take a position on the ultimate resolution of cross-Strait differences, provided they are resolved peacefully” (Lawrence Reference Lawrence2024). In short, and as noted later, U.S. administrations of both parties have long considered Taiwan’s current status undetermined and take no position on what its future status should be.

2.3.3 The U.S.’ Effective Taiwan Policy: Substance over Form

In candid moments, even high-ranking U.S. officials such as Biden’s National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan admit that U.S. Taiwan policy is “not a model of clarity” and is “built on a series of internal tensions.” Yet the U.S. government’s vague position is by design. It has in practice enabled significant policy flexibility in support of what Sullivan defines as the long-standing “practical objective” of U.S. “One China” policy: to “ensure that there are no unilateral changes to the status quo from either side and that we maintain that peace and stability across the Taiwan Strait” (CNN 2023).

Given Beijing’s long-standing refusal to forswear the use of force or coercion to realize what it calls “reunification,” to achieve these objectives the 1979 TRA authorized “defensive” arms sales to Taiwan and declared it U.S. policy “to consider any effort to determine the future of Taiwan by other than peaceful means, including by boycotts or embargoes, a threat to the peace and security of the Western Pacific area and of grave concern to the United States” (“Taiwan Relations Act” 1979).

Meanwhile, the U.S. declaration of an “abiding interest” (Department of State 2022) in the peaceful resolution of cross-Strait differences not only suggests the possibility of U.S. intervention if Beijing were to use “other than peaceful means” against Taiwan, it also suggests that PRC aggression could be a game-changer in other ways. For instance, after what were then the largest-ever PLA military exercises around Taiwan in March 1996, Secretary of State Warren Christopher stated not only that the United States remains committed to “robust unofficial relations” with Taiwan but also that “our ‘one China’ policy is predicated on the PRC’s pursuit of a peaceful resolution of issues between Taipei and Beijing” (Christopher Reference Christopher1996).

2.3.4 Defining Unofficiality

To say U.S. relations with Taiwan are “unofficial” is one thing; to define what “unofficial” – or “robust” – means in practice, and where the effective bounds on “appropriate” policy are, is something entirely different. As Bush notes, “In between the clearly official and clearly unofficial, there are a lot of grey areas.” He highlights four factors that affect U.S. decision-making: consideration of national interests, expected reaction from Beijing, Taiwan’s own policies, and domestic political pressures. (Bush Reference Bush2017, 15–18) As Sections 3 and 4 attest, the same basic logic applies to major U.S. democratic allies.

Early examples of U.S. efforts to preserve what Bush refers to as “the façade of unofficiality” included the decision to set up the American Institute in Taiwan (AIT) in 1979 as a private, nongovernmental organization – rather than an official embassy – and the facts that AIT employees for many years had to formally separate from their government agencies before taking up their posts and had to meet their Taiwan counterparts outside government offices (Bush Reference Bush2017, 15). Although by most measures U.S.-Taiwan engagement has become far more robust and transparent over the past forty-five years, efforts are still made to keep up the officially “unofficial” nature of exchanges. For example, recent high-level meetings involving Taiwan’s sitting foreign minister and national security advisor were held not in the U.S. capital of Washington, D.C. but a few miles outside it (Financial Times 2024).

Within the broad and amorphous framework of the U.S.’ post-1979 “One China policy,” U.S. leaders have had ample room to decide practical policies toward Taiwan and the Taiwan Strait. These decisions are fundamentally political. They have been shaped by an unavoidable tension between a desire to support Taiwan’s effective autonomy internationally on the one hand, and the twin strategic imperatives to maintain stable ties with the nuclear-armed PRC – today the world’s largest trading state, second-largest economy, second-most powerful military, and a U.S. top-three trading partner – while also reducing the risk of Beijing taking destabilizing actions across the Strait on the other.

Analytically, therefore, one must distinguish between the “form” of the U.S.-Taiwan relationship, whereby in officially recognizing only the PRC government the U.S. government since 1979 has adhered to a “One China” policy, and its “substance,” whereby U.S. “unofficial” relations with Taiwan have become increasingly robust over time (Bush Reference Bush2004, 121–22).

In short, U.S. recognition of the PRC in 1979 as the “sole legal government of China” was not tantamount to a U.S. commitment to silence or disinterest about Taiwan or cross-Strait stability; nor did it lock in a particular level or type of engagement with Taipei. On the contrary, over time successive U.S. administrations – often with significant pressure from Congress – have chosen to deepen practical cooperation, including militarily. Seen from Washington, these effective shifts generally have been aimed at maintaining a precarious status quo amid some profound changes, including Taiwan’s democratization, a rapidly changing military balance of power, and Beijing’s increased coercive pressure against Taipei – especially during periods of DPP rule.

The cumulative effect of irregular internal policy reviews, ad hoc executive decisions, and legislation spearheaded by the U.S. Congress, inter alia, is that U.S. efforts to support Taiwan’s international space and peace and stability across the Strait are demonstrably more extensive today than in 1979, 1999, or even 2019. Especially since the 1990s, so, too, are the frequency, level, and nature of bilateral exchanges between government officials and the depth and breadth of military, security, and intelligence cooperation.

Unfortunately, what the overwhelmingly U.S.-centric academic and policy discourse often misses is that key U.S. allies have played a critical support, and at times even leading, role in engaging Taiwan, bolstering its international space, and contributing to peace and stability across the Taiwan Strait.

2.4 The Basic Two-Step Analytical Framework

Inspired by the U.S. case, this study’s analytical framework is based on the following judgment: a U.S. ally’s (or any foreign government’s) effective policy toward Taiwan and the Taiwan Strait is best understood as the combination of two factors: (1) its official position on “One China”; and (2) how the allied government’s political leaders have subsequently chosen to operationalize that position in practical terms in the absence of official diplomatic relations with Taiwan. This conceptualization inspires the following straightforward two-step analytical framework:

2.4.1 Step 1: Identify the Government’s Official Position on Taiwan’s Status

What is the allied government’s official position on “One China” as it relates to the sovereignty question? Most fundamentally: upon recognizing the PRC, did the allied government endorse Beijing’s claim of sovereignty over Taiwan?

Given Beijing’s frequent assertions that the U.S. and its major democratic treaty allies are violating past commitments to the PRC’s “one-China principle,” whether each government actually endorsed Beijing’s claim of sovereignty over Taiwan upon recognizing the PRC is fundamental to any objective analysis of U.S. allies’ positions and policies. Indeed, the U.S. case demonstrates how an ambiguous position can be a key enabler of “robust unofficial” relations with Taiwan and how Washington pursues its “practical objective” vis-à-vis the Taiwan Strait. It may also have potential legal implications if China were ever to openly aggress against Taiwan.

In most cases examined in Sections 3 and 4, the allied government’s official position on “One China” is formalized in a unilateral declaration or joint communiqué with the PRC. Regardless of the form, the positions themselves are unilateral statements of policy; that is, they are political positions, not consensus or legally binding agreements with or commitments to Beijing. This matters not only in the abstract or when thinking about potential futures, but also because a few cases reveal subtle but noteworthy shifts – even decades after recognizing Beijing.

2.4.2 Step 2: Identify How Leaders Have Chosen to Operationalize That Official Position

In the absence of official diplomatic relations with Taipei, to what extent and how have subsequent generations of political leaders in the allied government developed unofficial relations with Taiwan in terms of concrete policies and official rhetoric, the nature, degree, and extent of bilateral or multilateral engagement and cooperation, and as measured in statements/actions in support of Taiwan’s international space and the cross-Strait status quo?

The second step entails a significantly higher empirical hurdle: examining the historical and contemporary record in each case to identify the practical substance of the allied government’s rhetoric and effective policies toward Taiwan and the Taiwan Strait.

The U.S. example is again illustrative of why this second step is also essential. Though in terms of having major domestic legislation (the TRA) at the heart of official policy the U.S. case is sui generis, Washington’s evolving approach across successive administrations nevertheless provides a useful baseline and menu of candidate metrics upon which to assess variability in allies’ approaches. Though each ally’s approach has unique features, in the interest of space, policy relevance, and analytical tractability – especially, the importance of comparing apples to apples – this study’s analysis privileges several key indicators (Table 2).

Table 2 Key indicators for assessing operationalization in practical policy

Vis-à-vis Taiwan

“Rhetorical policy” regarding Taiwan itself; that is, the extent to which and how relations with Taiwan, its importance, and its international space feature in official government rhetoric (including speeches and diplomatic white papers).Footnote 3

The existence, nature, frequency, and level of seniority of (de facto) diplomatic and political exchange, including the creation, staffing, and function of representative offices in Taipei

The issue areas and policy domains in which the government meaningfully engages Taiwan (e.g., is engagement actually limited to strictly economic and cultural exchange, as Beijing prefers and official rhetoric often suggests?)

The extent of security cooperation/signaling (e.g., security dialogues; arms sales)

Vis-à-vis the Taiwan Strait

“Rhetorical policy” regarding the cross-Strait dispute, e.g., official expressions of concern regarding “peace and stability,” calls for “peaceful resolution,” and/or opposition to “unilateral changes to the status quo” and “use of force/coercion”

Whether the government deploys naval vessels to transit the Taiwan Strait

Given the extreme sensitivities in Beijing regarding what its leaders consider to be “at the heart of China’s core interests,” intentional ambiguity and subtlety permeate U.S. positions and policies vis-à-vis Taiwan and the Taiwan Strait. Unsurprisingly, the same is generally true to even greater degree for U.S. allies and partners – almost all of whom can today be considered objectively “weaker” relative to Beijing in terms of material power and, in several cases, have far deeper economic interests vis-à-vis China than the United States. Empirical clarity is further frustrated by the unique circumstances of each case, widely varying domestic politics, the strong preference of all U.S. allies to avoid unnecessarily provoking Beijing on the extremely sensitive “issue” of Taiwan, the tendency of some governments to quietly do more than they are willing to say on-the-record, and the not infrequent public statements by politicians at odds with official policy. Given these challenges, the scholar can only do their best, inevitably imperfect though it may be. Simply put, Step 2 is an inherently messy, but necessary, business.

2.4.3 The Necessity of Both Steps

To enable a complete understanding of U.S. allies’ effective policies toward Taiwan and the Taiwan Strait, both steps of the analytical framework are necessary. In this and future studies of these or additional cases, it is extremely important to treat the second question as analytically distinct from the first.

Conflating the two would be problematic in both principle and practice. As the evolution of effective U.S. engagement vis-à-vis Taiwan and the Taiwan Strait after 1979 shows, the form a static, decades-old official position on “One China” takes can be a poor predictor of the future substance of actual policy. Accordingly, scholars should not “prebake” into the analytical framework an assumption of direct or consistent correlation – much less causation – between an allied government’s abstract, decades-old official position on Taiwan’s status and the extent of its willingness (or lack thereof) to develop robust “unofficial” and practical ties with Taiwan, support its international space, or assert an interest in peace and stability across the Taiwan Strait.

As Sections 3 and 4 demonstrate, some allied governments maintain an official position on “One China” similarly vague to that of the U.S. but choose to severely limit practical engagement with and support for Taiwan. Conversely, some allied governments have shifted official rhetoric on Taiwan’s status closer to Beijing’s preferences than the United States has but nevertheless adopt relatively forward-leaning policies and rhetoric in support of Taiwan. In short, neglecting either of the two steps risks potentially erroneous prejudgments about a determinative causal link between official position (form) and effective policy (substance) that risks inappropriately skewing the analysis.

3 Indo-Pacific Allies: Japan, South Korea, and Australia

This section examines the significance for Taiwan’s international space and cross-Strait dynamics, past and present, of the positions and policies of Japan, the Republic of Korea (below, “ROK” or Korea), and Australia: the U.S.’ three politically closest, most militarily capable, and wealthiest democratic treaty allies in the Western Pacific. All three have significant economic and geopolitical stakes in peace and stability across the Taiwan Strait, as well as important potential roles to play in shaping the peacetime environment and deterring or, potentially, responding to a contingency. Reasons are manifold but generally include: each government’s extremely close ties with Washington; geographical proximity to and reliance on commercial trade routes around Taiwan; extensive economic linkages with both China and Taiwan; and, especially for nearby Japan and South Korea, tens of thousands of forward-deployed U.S. military forces on allied soil.Footnote 4