Concerns about negative attitudes toward democracy, such as declining political trust, are growing in Europe and the United States (Jennings et al. Reference Jennings2017; OECD 2019). A fundamental concern is that low levels of political trust undermine the capacity to govern effectively (see, for example, Citrin and Stoker Reference Citrin and Stoker2018; Marien and Hooghe Reference Marien and Hooghe2011). Moreover, citizens hit by the negative consequences of globalization generally have negative attitudes toward established political institutions, which make them more inclined to support populist actors (for example, Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi2012; Torcal and Montero Reference Torcal and Montero2006). To illustrate the implications of low political trust, the tendency to vote ‘Leave’ concerning Brexit was higher among citizens who felt left behind either economically or culturally by the political establishment (Abrams and Travaglino Reference Abrams and Travaglino2018; Clarke, Goodwin, and Whiteley Reference Clarke, Goodwin and Whiteley2017; Fetzer Reference Fetzer2019; Hobolt Reference Hobolt2016).

Multiple studies have examined whether there is a link between government competence and political trust. Such efforts have primarily been directed at government performance through a heavy focus on the strength of the economy (for example, Citrin and Green Reference Citrin and Green1986; Hetherington and Rudolph Reference Hetherington and Rudolph2008; Keele Reference Keele2007; Van Erkel and Van der Meer Reference Van Erkel and Van der Meer2016) or the delivery of tangible outcomes such as high-quality public services (for example, Van Ryzin Reference Van Ryzin2011). Other related work on government competence and outcomes ties political trust to the adoption of favourable policies and bureaucratic decisions or whether the government, in general, is considered to be wasteful (for example, Allen and Birch Reference Allen and Birch2015; Hansen Reference Hansen2023; Hibbing and Theiss-Morse Reference Hibbing and Theiss-Morse2002; Nye, Zelikow, and King Reference Nye, Zelikow and King1997; Popkin Reference Popkin1991).

However, how political trust relates to government competence in achieving promised policy objectives has received little attention. Extending the current literature on competence-related explanations of political trust, the novel idea that government competence also involves how efficiently promised policy objectives are achieved is introduced. The question of efficiency is arguably relevant to cases where the policy objective is polarizing and consensual. This article argues that in the case of polarizing political issues, the link between efficiency and political trust is conditioned by whether citizens support or oppose the specific objective. In this article, the link between process efficiency and political trust in the context of Brexit is investigated, which entailed the polarizing promise to leave the European Union (EU).

Fulfilling such promises often take time; decision-makers engage in a policy process that can be efficient if systematic and substantial progress towards achieving the objective is made and inefficient if the process is dragged out. This article uses high-quality data from the British Election Study and a difference-in-differences (DiD) model to compare the political trust of Remain and Leave voters in response to (in)efficiency in achieving the promised objective of leaving the EU. In accordance with expectations, the findings suggest that Leave voters increased their political trust more than Remain voters in response to efficiency and decreased their political trust more than Remain voters in cases of inefficiency. This implies that political trust is influenced by how efficient government is in achieving promised policy objectives and also that government, through efficiency, only can increase trust among supporters of the objective. In sum, findings contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the consequences of Brexit and reveal innovative insights into the complex link between government competence and political trust.

Government Efficiency and Political Trust

Political trust is a relational concept (Van der Meer and Hakhverdian Reference Van der Meer and Hakhverdian2017) constituting the willingness of citizens to be vulnerable to the political regime, institutions, and actors (Mayer, Davis, and David Schoorman Reference Mayer, Davis and David Schoorman1995; Weinberg Reference Weinberg2022). This article is concerned with political trust as an overarching set of general attitudes toward democracy. Political trust consists of different aspects as it refers to objects ranging from specific political institutions to more diffuse attitudes toward the regime (Easton Reference Easton1975; Van der Meer and Hakhverdian Reference Van der Meer and Hakhverdian2017). Promised policy objectives are defined as statements concerning unequivocal support for a specific action that can be clearly determined to have occurred or not (Thomson et al. Reference Thomson2017). Building on this definition, research suggests that two dimensions are particularly important for citizens to consider statements as promises: commitment and whether the policy content of the promise concerns an output that politicians have control over (Krishnarajan and Jensen Reference Krishnarajan and Jensen2021).

While current evidence ties political trust to certain aspects of government competence, it is argued that competence manifests itself in how efficient government is in achieving promised policy objectives in the policy process. Thus, efficiency is aligned with competence and involves procedures. Efficiency concerns the ratio of output to input and is a continuum of the ability to provide a promised objective using the least amount of input. The political decision-making process is efficient if politicians use their time and effort to make progress toward achieving the promised objective. The process is inefficient when politicians use their time and effort on discussions that do not contribute to reaching an agreement on the promised policy objective. The argument lies between a pure outcome focus and a pure emphasis on the process. While the argumentcentres around how politicians perform in the policy-making process, it also focuses on whether politicians are closer to an outcome.

When citizens perceive a statement as a promise, they generally follow the basic idea of democratic accountability (Krishnarajan and Jensen Reference Krishnarajan and Jensen2021; Thomson et al. Reference Thomson2017). Citizens reward the government for keeping their promises, but when pledges are not fulfilled, they are less likely to vote for the governing party and have less positive government evaluations (for example, Elinder, Jordahl, and Poutvaara Reference Elinder, Jordahl and Poutvaara2015; Matthieß Reference Matthieß2020; Matthieß Reference Matthieß2022, Naurin, Soroka, and Markwat Reference Naurin, Soroka and Markwat2019). It is argued that efficiency influences political trust because it changes the perceived likelihood of pledge fulfillment in the eyes of citizens. That is, efficiency leads to a perceived increase in the likelihood of pledge fulfillment, while inefficiency leads to an increased perceived likelihood of non-fulfillment. Therefore, citizens are expected to hold the political institutions that made the promise (for example, the government or politicians in general) accountable by adjusting their political trust according to whether the responsible institutions are efficient or inefficient in achieving promised objectives. Since pledge fulfillment can be considered a cornerstone to how citizens perceive a well-functioning democracy, it is expected that government efficiency in achieving promised objectives influences not only trust in political institutions but also the aspect of political trust, referring to more diffuse attitudes toward the functioning of the regime.

However, the relationship between pledges and accountability is heavily contingent on citizens' prior (ideological) beliefs. Due to motivated reasoning, citizens respond to government efficiency and inefficiency in achieving promised policy objectives to fit their pre-defined interests (Kunda Reference Kunda1990; Taber and Lodge Reference Taber and Lodge2006; Tilley and Hobolt Reference Tilley and Hobolt2011). This implies that the character of the promised policy objective is central to political trust responses. In cases where there is consensus on the objective, efficiency is generally preferred over inefficiency since the objective set forth in the promise fits with all citizens' pre-defined views. When the objective is polarizing, supporters prefer efficiency because it is in accordance with prior beliefs. In contrast, opponents of the objective are likely to be more accepting of inefficiency since the objective is against their prior beliefs. Opponents may still diminish their trust due to inefficiency, although to a lesser degree than supporters, since inefficiency, even in achieving undesirable outcomes, could suggest inefficiency in achieving any objective.

Hypothesis 1a: When government is efficient in achieving a promised policy objective, citizens who support the objective increase their political trust more than citizens who oppose the objective.

Hypothesis 1b: When government is inefficient in achieving a promised policy objective, citizens who support the objective decrease their political trust more than citizens who oppose the objective.

Methods and Research Design

Case: Brexit

This article utilizes the case of Brexit, a striking example of a political promise (BBC 2013). Citizens are expected to consider leaving the EU (that is, Brexit) as a promise because politicians were committed to honouring the result of the referendum no matter the outcome (Conservatives 2015). Furthermore, the policy content of the pledge is about an output the government, to a large extent, has direct control over. Efficiency is expected to be essential in this case, as leaving the EU consists of a sequence of highly visible and salient political events that either facilitated or impeded the achievement of this political promise. Finally, as the policy objective is polarizing, Brexit provides a suitable case to investigate the hypothesized difference in responses to process efficiency among citizens who support and oppose the objective. In particular, Leave voters are expected to desire efficiency and support the objective of exiting the EU. In contrast, efficiency is less desirable for Remain voters who are expected to be in opposition to that objective. Between Leave and Remain voters, this is expected to result in different political trust responses to efficiency in achieving an exit from the EU.

Data

To assess the relationship between process efficiency and political trust, this article uses unique, high-quality data from the British Election Study (BES) (Fieldhouse et al. Reference Fieldhouse2020) consisting of multiple survey waves fielded in Great Britain (19 waves covering the period from February 2014 to December 2019). The BES is designed to be cross-sectionally representative in each wave (N ≈ 30,000 British citizens in each wave). Waves covering the whole period from the referendum to when the UK officially withdrew from the EU are used (that is, the period covering the Brexit negotiations). This provides a unique opportunity to study how citizens evaluate political trust based on real-world process efficiency. Furthermore, the detailed data from large representative survey waves strengthen external validity and provide statistical power to detect small effect sizes.Footnote 1

The Political Decision-Making Process Following the Brexit Referendum

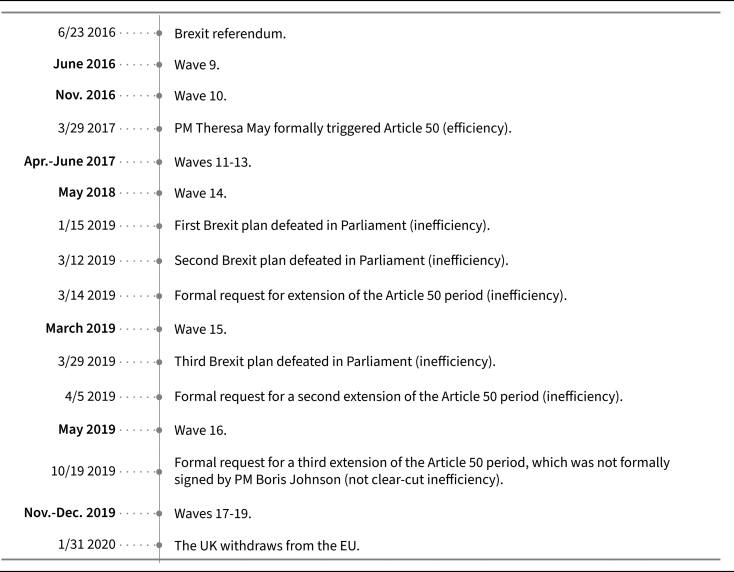

Table 1 provides a simplified timeline highlighting political events signalling efficiency or lack of efficiency in achieving Brexit and the timing of the waves in the BES. Criteria for events are formal decisions concerning Brexit, which are decided on at the highest institutional level (that is, in parliament). In the table, it is identified when the political decision-making process signalled efficiency or inefficiency in fulfilling the promise of leaving the European Union.Footnote 2

Table 1. Timeline of events reflecting efficiency or inefficiency in achieving Brexit

Note: Based on Walker (Reference Walker2020). The table shows the timing of BES-waves, the Brexit referendum, when the UK left the EU, and events reflecting efficiency or inefficiency in achieving Brexit. Waves 1–8 of the BES were conducted before the referendum and are not a part of the analysis.

The first major step toward leaving the EU arguably happened when UK Prime Minister Theresa May set out a formal strategy for leaving the EU and triggered Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union on 29 March 2017 (which was authorized by parliament). This event set an official date for leaving the European Union and started a two-year negotiation period, with the UK set to leave the EU on 29 March 2019. Thus, this event in the decision-making process signalled efficiency in achieving the promised policy objective of leaving the EU, which was expected to influence trust (based on hypothesis 1a).

Operational expectation 1: When Article 50 was triggered, Leave voters increased their political trust more than Remain voters.

After triggering Article 50, the Brexit negotiations began in June 2017 and concluded with the UK and EU negotiation teams reaching an agreement on withdrawal in November 2018. However, the Brexit negotiations were in a major deadlock in the following months. Theresa May and her Conservative government faced two votes of no confidence alongside suffering huge defeats in three votes on a proposed Withdrawal Agreement (Brexit Plan) in Parliament. In relation to these defeats, she asked for two extensions of the Article 50 period. Such Brexit plan defeats and extensions of the Article 50 period signalled inefficiency in achieving the promised policy objective of leaving the EU, which was expected to decrease trust among Brexit supporters (based on hypothesis 1b).

Operational expectation 2: When the Brexit plan was defeated in Parliament and extensions of the Article 50 period had been requested, Leave voters decreased their trust more than Remain voters.

As pointed out in the timeline, in October 2019, there was a request for a third extension of the Article 50 period. However, this request was not formally signed by Prime Minister Boris Johnson, who sent a second letter to the president of the European Council, Donald Tusk, explaining that he did not want a further extension. In addition, the request did not follow the defeat(s) of the Brexit plan in parliament. Instead, the UK government and the European Commission agreed on a revised withdrawal agreement earlier in October 2019, which would be discussed in Parliament later that autumn and at the beginning of 2020. Therefore, citizens were not expected to perceive the third request to extend the Article 50 period as a clear-cut event of inefficiency.

Measures

Prior work on political trust has used measures of both trust in specific political institutions or politicians in general and broader system measures (for example, satisfaction with democracy) to capture different aspects of the broad concept of political trust (for example, Marien Reference Marien, Zmerli and Hooghe2013; Van der Meer and Hakhverdian Reference Van der Meer and Hakhverdian2017). Accordingly, this article captures two outcome measures. First, a single item covering trust in Members of Parliament in general taps into trust in politicians (1 = no trust; 7 = a great deal of trust). While this item might not directly capture trust in a political institution, it was used because citizens might hold all politicians responsible for executing the promise of Brexit. Furthermore, the survey question asks about politicians in general, and thus it is arguably a good proxy for trust in parliament in this case (a specific political institution).Footnote 3 Second, satisfaction with democracy indicates more diffuse attitudes towards the political system (1 = Very dissatisfied; 4 = Very satisfied). Both measures are included as outcomes to investigate whether government efficiency influences both aspects of political trust. The outcome measures were recoded 0–1.

Remain and Leave voters were identified by vote intention, which was asked in wave 8 (just before the referendum).Footnote 4 To ensure a valid measure of ex-ante Remain/Leave status, data from wave 8 was used to determine vote status in all waves (see also Online Appendix B for results using other measures of Leave/Remain identification).

Estimation Strategy

To estimate the effect of process efficiency on political trust, changes from pre- to post-events reflecting either efficiency or inefficiency in the decision-making process were tracked. The analysis is structured so that pre- and post-waves (waves before and after events indicating efficiency or inefficiency) are chosen to use the narrowest window possible around these events, given the timing of survey waves. When the outcome measure is unavailable in the wave that would have been ideal for the analysis, the wave in closest proximity is used (the closest earlier wave for pre-measurement and the closest wave collected after the event for post-measurement).

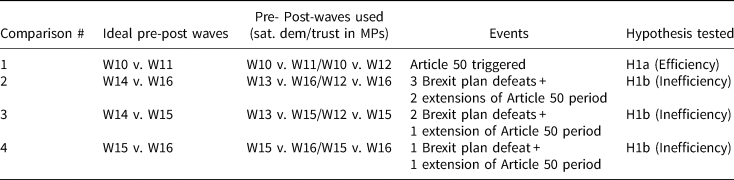

Table 2 provides an overview of the pre- and post-waves used in the analysis and how they differ from the waves that would have been ideal for the study (if data on the outcomes had been available). As Article 50 was triggered on a specific date, only a single comparison (comparison #1 in Table 2) was used to investigate the first operational expectation and hypothesis 1a. However, multiple comparisons (comparisons #2–4) were used to investigate the second operational expectation and hypothesis 1b, as the Brexit Plan defeats and extensions to the Article 50 period occurred over a longer period of time (as illustrated in Table 1). Therefore, rather than only investigating the effect of all defeats and extensions in a single estimation (as done in comparison # 2), multiple relevant time periods were analyzed to employ a more robust test of the hypothesis.

Table 2. Overview of ideal and used pre-post waves

Sat. dem, satisfaction with democracy; MPs, Members of Parliament.

Note: The table shows the waves that would be ideal for the analysis alongside the waves used in the analysis (due to data availability on the dependent variable; see also Online Appendix C). Thus, the pre-waves and post-waves used in the analysis vary across the outcome measures.

To examine whether Leave voters (compared to Remain voters) reacted more strongly to events related to process efficiency, a DiD identification strategy was used (Angrist and Pischke Reference Angrist and Pischke2009). This empirical strategy gives an estimate that takes account of the initial difference between the two groups at the aggregate level (that is, time-invariant characteristics). At the same time, the DiD strategy takes account of the general time trend (that is, the general trend in political trust across all citizens in that time period). Specifically, the DiD model estimated whether the effect of process efficiency on political trust was moderated by vote choice in the referendum by comparing pre-to- trends in political trust between Remain and Leave voters.

To perform significance tests, linear interaction models (OLS) were run with an interaction term between vote choice (0 = Remain; 1 = Leave) and a time dummy (0 = pre-event; 1 = post-event). δ is the DiD estimate of the divided response to the given event in the decision-making process between Remain and Leave voters.

Results

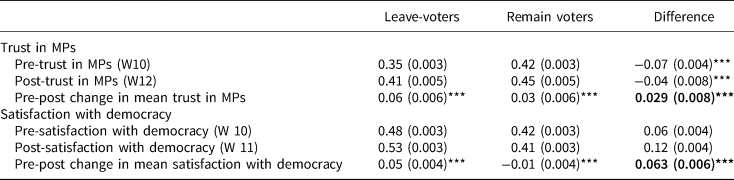

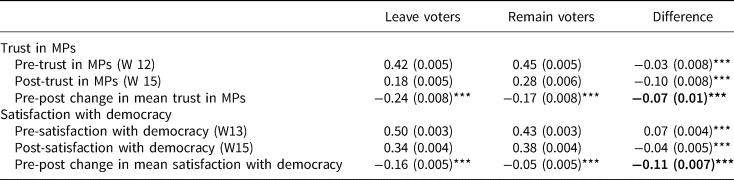

The main results are provided in Tables 3–6. In accordance with expectations, the results suggest that when the decision-making process reflects efficiency in achieving the promised policy objective of leaving the EU, Leave voters increased their political trust more than Remain voters. As shown in Table 3, the DiD estimate is significant and positive (0.029; p < 0.001) when examining trust in members of Parliament, although the effect size is small. Moreover, in line with H1a, results reveal that satisfaction with democracy increased by 6.3 percentage points more among Leave voters compared to Remain voters (p < 0.001) in response to government efficiency (that is, triggering Article 50).

Table 3. Average trust in MPs and satisfaction with democracy pre-post triggering Article 50 (comparison #1)

Note: ***p < 0.001. Means with standard errors in parentheses. Two-sided t-tests. DiD estimates are marked in bold. Nsatdem. = 35,842; Ntrustmp. = 23,213.

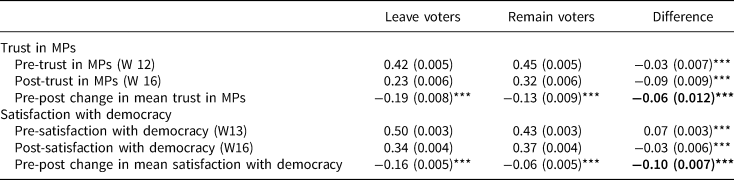

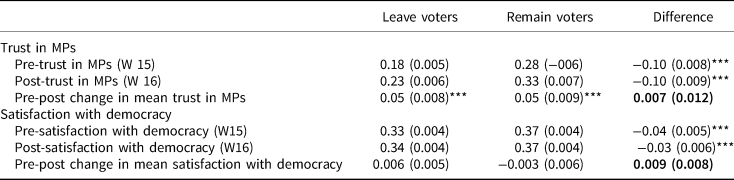

Table 4. Average trust in MPs and satisfaction with democracy pre-post three Brexit Plan defeats and two extensions of the Article 50 period (comparison #2)

Note: ***p < 0.001. Means with standard errors in parentheses. Two-sided t-tests. DiD estimates are marked in bold. Nsatdem. = 29,280; Ntrustmp. = 7,708.

Table 5. Average trust in MPs and satisfaction with democracy pre-post two Brexit Plan defeats and one extension of the Article 50 period (comparison #3)

Note: ***p < 0.001. Means with standard errors in parentheses. Two-sided t-tests. DiD estimates are marked in bold. Nsatdem. = 31,982; Ntrustmp. = 8,479.

Table 6. Average trust in MPs and satisfaction with democracy pre-post one Brexit plan defeat and one extension of the Article 50 period (comparison #4)

Note: ***p<0.001. Means with standard errors in parentheses. Two-sided t-tests. DiD-estimates are marked in bold. Nsatdem = 24,302; Ntrustmp = 6,179.

Turning to events reflecting inefficiency in achieving Brexit, the results generally demonstrate that Leave voters reacted more negatively in terms of political trust than Remain voters. Table 4 shows how Remain and Leave voters responded to an inefficient process, indicated by three Brexit Plan defeats and two extensions of the Article 50 period. When examining trust in members of Parliament, the DiD estimate is negative (−0.06; p < 0.001). The findings are even more clear-cut in favour of H1b in the case of satisfaction with democracy. Initially, satisfaction with democracy was slightly higher among Leave voters than Remain voters (compare 0.50 to 0.43 in Table 4). However, this gap reversed after citizens were exposed to the inefficient events of the three Brexit plan defeats and two extensions of the Article 50 period. In wave 16, the estimated mean satisfaction with democracy was 0.34 for Leave voters and 0.37 for Remain voters, indicating that Remain voters were now more satisfied with democracy than Leave voters. Thus, Leave voters became 16 percentage points (p < 0.001) less satisfied with democracy, while satisfaction with democracy only decreased by 6 percentage points (p < 0.001) for Remain voters. Although both groups of voters lowered their satisfaction, the DiD estimate of −0.10 (p < 0.001) suggests that Leave voters responded significantly more negatively to the inefficient process.

The same pattern of results emerges when investigating the effect of two Brexit Plan defeats and one extension of the Article 50 period in isolation (see Table 5). The DiD estimates are significantly negative, indicating that pre-to-post changes in political trust were more negative for Leave voters than Remain voters. In substantial terms, Leave voters lowered their political trust by 7–11 percentage points more than Remain voters.

Finally, Table 6 compares political trust before the inefficient events concerning the final Brexit Plan defeat and the third extension of the Article 50 period with political trust after these inefficient events. In isolation, the DiD estimates are insignificant, which are against the expectations of a more negative effect of government inefficiency in achieving Brexit for Leave voters. One potential explanation is that political trust had just dropped substantially (partly due to other events related to government inefficiency), and the subsequent inefficient events had no additional effects on political trust. Another explanation could be the timing of the post-wave (wave 16), which entailed that the time period between waves 15 and 16 also included other events, such as Theresa May stepping down as prime minister (partly because she could not deliver on Brexit). This could even out the negative effect of the inefficient events in the analyzed time period.

Regarding effect sizes, the general pattern of results indicates that events signalling (in)efficiency substantially affect political trust compared to other differences between waves (shown in Fig. 1). Only two DiD estimates stood out. These were related to a referendum (W8 v. W9) or a general election (W17/18 v. W19), which are strong predictors of political trust (see, for example, Dahlberg and Linde Reference Dahlberg and Linde2017). However, the effects are the largest and most consistently support the hypothesis concerning inefficiency when examining satisfaction with democracy. The results were generally supported by robustness checks such as alternative measurements, different regression models, and tests for potential violations of the identifying assumption (see Online Appendix B).

Figure 1. Trends for Remain and Leave voters.

Note: The two upper plots show the trends in mean satisfaction with democracy and mean trust in Members of Parliament across all waves for Leave voters (black) and Remain voters (grey) separately. The two plots in the lower panel estimate the difference in outcome between two waves conditional on Leave/Remain status with associated 95 per cent confidence intervals. The vertical dotted lines indicate the following: (1) triggering Article 50, (2) two Brexit Plan defeats and one extension of the Article 50 period, and (3) one Brexit Plan defeat and one extension of the Article 50 period.

Concluding Discussion

Extensive prior work has carefully studied the role of government competence in explaining political trust (for example, Citrin and Stoker Reference Citrin and Stoker2018; Hansen Reference Hansen2022; Hetherington and Rudolph Reference Hetherington and Rudolph2015; Keele Reference Keele2007; Van Erkel and Van der Meer Reference Van Erkel and Van der Meer2016). The findings contribute to the literature by proposing a new competence dynamic focusing on government efficiency in achieving promised policy objectives. Generally, citizens become more trusting when the government is efficient and less trusting in cases of government inefficiency, but this tendency is clearly strongest among those supportive of the objective.

This article examined government efficiency in achieving the polarizing policy objective of Brexit using multiple representative cross-sectional surveys from the British Election Study over time. In line with expectations, the effect of government efficiency on political trust depends on citizens' status as Remain or Leave voters. In cases of efficiency, Leave voters increased their trust more than Remain voters, and inefficiency generally led to larger decreases in trust among Leave voters than among Remain voters. These findings follow the proposed motivated reasoning explanation, where citizens update their trust according to whether they support (Leave voters) or oppose (Remain voters) the promised objective.

The effect sizes also suggest that government inefficiency matters more for political trust than efficiency. This fits well with political psychology literature, suggesting that individuals react more strongly to negative rather than positive information (Naurin, Soroka, and Markwat Reference Naurin, Soroka and Markwat2019; Soroka Reference Soroka2014). Yet, this interpretation is speculative as this article did not examine events of efficiency and inefficiency of the same magnitude. It could also be the case that the results reflect a lagged effect, meaning that the inefficient events carried more weight and thus prompted a stronger reaction because it happened late in the process.

The findings also contribute to other strands of literature, with insights into the consequences of Brexit and how citizens' political attitudes were influenced by the negotiation process regarding the historic decision to leave the EU (for example, Hobolt, Leeper, and Tilley Reference Hobolt, Leeper and Tilley2021; Schwartz et al. Reference Schwartz2021). At the same time, the findings speak to studies on election pledges. In particular, whether citizens hold the government accountable for achieving promised policy objectives (for example, Krishnarajan and Jensen Reference Krishnarajan and Jensen2021; Naurin and Oscarsson Reference Naurin and Oscarsson2017; Thomson et al. Reference Thomson2017). More specifically, given that inefficiency leads to a larger likelihood of non-fulfillment in the minds of citizens, the findings align with other studies that found citizens reacting negatively to the non-fulfillment of pledges (Matthieß Reference Matthieß2022).

Although this article consistently reveals evidence of the importance of government efficiency in the Brexit negotiation process, questions remain about generalizability to other cases. The Brexit case is a polarizing objective, but the dynamic in question is of broader generality. It could be relevant to theoretically comparable cases where the policy objective is more or less consensual (for example, regarding climate or unemployment) or other polarizing objectives such as police reforms. However, important assumptions are that the process is both highly visible and salient to citizens. Thus, although no other country has left the EU, the findings are arguably relevant for other cases where the government is clearly efficient or inefficient in achieving promised objectives.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123423000388.

Data availability statement

Replication Data for this article can be found in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/XKNPBO.

Acknowledgement

I want to thank the three anonymous reviewers and the editor for their helpful suggestions, which greatly improved the paper.

Financial support

None.

Competing interests

None.