Introduction

The increasing intensification of pig (Sus scrofa domesticus) farming systems led to major concerns regarding animal welfare, particularly in the final phases of production, such as transport and pre-slaughter conditions (Robert & Martineau Reference Robert and Martineau1994). These procedures are considered among the most stressful experiences in a pig’s life, impacting physiological responses, immune function, and meat quality. Thus, identifying objective, non-invasive biomarkers that reflect acute stress under these conditions could support both animal welfare and production quality (Martínez-Miró et al. Reference Martínez-Miró, Tecles, Ramón, Escribano, Hernández, Madrid, Orengo, Martínez-Subiela, Manteca and Cerón2016).

Saliva is commonly used as a biological sample to evaluate stress because it has numerous advantages over serum, since it is easy to obtain, and its sampling is stress-free and painless for pigs (Nunes et al. Reference Nunes, Brenzikofer and Macedo2011). In the context of stress assessment in pigs, cortisol is arguably the most frequently measured analyte in saliva (Ott et al. Reference Ott, Soler, Moons, Kashiha, Bahr, Vandermeulen, Janssens, Gutiérrez, Escribano, Cerón, Berckmans, Tuyttens and Niewold2014) due to its role in representing the activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis (Oyola & Handa Reference Oyola and Handa2017). In addition to cortisol, the levels of other salivary proteins may be affected by stress. These include chromogranin A and alpha-amylase, which are related to the sympathoadrenal-medullary (SAM) axis; S100A12, which is linked to the immune system; and oxytocin, among others (Escribano et al. Reference Escribano, Soler, Gutiérrez, Martínez-Subiela and Cerón2013; Contreras-Aguilar et al. Reference Contreras-Aguilar, Escribano, Martínez-Subiela, Martínez-Miró, Cerón and Tecles2018; Valros et al. Reference Valros, Lopez-Martinez, Munsterhjelm, Lopez-Arjona and Ceron2022; Botía et al. Reference Botía, Ortín-Bustillo, López-Martínez, Fuentes, Escribano, González-Bulnes, Manzanilla, Martínez-Subiela, Tvarijonaviciute, López-Arjona, Cerón, Tecles and Muñoz-Prieto2023). Consequently, saliva can be regarded as a biological sample containing analytes that have the potential to serve as biomarkers of stress, thereby facilitating a more comprehensive evaluation of animal welfare. Indeed, a recent study has described the presence of biomarkers in saliva that can differentiate between varying degrees of well-being at slaughterhouses (Botía et al. Reference Botía, Escribano, Ortín-Bustillo, López-Martínez, Fuentes, Jiménez-Caparrós, Hernández-Gómez, Avellaneda, Cerón, Rubio, Tvarijonaviciute, Martínez-Subiela, López-Arjona and Tecles2024). Therefore, identifying new biomarkers that allow us to differentiate between levels of stress could be very useful for assessing the welfare of animals and improving their management.

Proteomics facilitates the identification of potential biomarkers due to its capacity for simultaneously analysing numerous proteins (Bilić et al. Reference Bilić, Kuleš, Galan, Gomes de Pontes, Guillemin, Horvatić, Festa Sabes, Mrljak and Eckersall2018). The application of proteomics to saliva samples from different stress models allows the changes associated with these situations to be revealed by studying a complete protein profile of the samples. One type of mass spectrometry (MS)-based proteomics analysis utilises isobaric labels, such as tandem mass tags (TMT), which facilitate the relative quantification of proteins in biological samples. This, in turn, enables the interpretation and protein identification through hyphenated analytical techniques, such as liquid chromatography-tandem MS (LC-MS/MS) (Baeumlisberger et al. Reference Baeumlisberger, Arrey, Rietschel, Rohmer, Papasotiriou, Mueller, Beckhaus and Karas2010). Previously, this proteomic technique has been used in a study of a salivary proteome of pigs after stressful situations, such as immobilisation with nose snaring and lameness (Escribano et al. Reference Escribano, Horvatić, Contreras-Aguilar, Guillemin, Cerón, Tecles, Martinez-Miró, Eckersall, Manteca and Mrljak2019).

The aim of this study was to identify and evaluate potential new biomarkers in pigs’ saliva to differentiate between different levels of stress under two pre-slaughter conditions: one designed to minimise stress at pre-slaughter, and the other involving a more stressful process at pre-slaughter. This was done through: (1) a proteomics study to identify significantly altered salivary between the two groups; and (2) an analytical validation experiment for two of the significantly altered salivary proteins identified.

Materials and methods

Study animals and saliva samples

Animals and sampling procedures were described previously (Botía et al. Reference Botía, Escribano, Ortín-Bustillo, López-Martínez, Fuentes, Jiménez-Caparrós, Hernández-Gómez, Avellaneda, Cerón, Rubio, Tvarijonaviciute, Martínez-Subiela, López-Arjona and Tecles2024). The surplus samples from this experiment were utilised in the present report.

Briefly, 30 male pigs (Large White × Duroc) at the end-fattening period (5–6 months of age and an approximate bodyweight of 116 kg) were included in this study. The animals were housed in a farm in southern Spain in groups of 14 animals with a minimum space of 0.65 m2 per animal and provided ad libitum access to a balanced diet and water. The experiment took place in February 2022. At the end of the fattening period, all pigs were transported the same day to a commercial slaughterhouse. The animals were then separated into two distinct groups:

-

• Group A (improved pre-slaughter conditions; n = 15): The animals were transported and accommodated at the slaughterhouse at low density (1.25 m2 per animal) without mixing with unfamiliar animals throughout the entire process.

-

• Group B (stressful pre-slaughter conditions; n = 15): The animals were transported and housed in conditions of high density (0.55 m2 per animal) mixing with unfamiliar animals.

All saliva samples used in this study were collected after 4 h in the slaughterhouse by allowing the pigs to chew on a polyurethane sponge for 1 min. When sufficiently wet, the sponges were placed in plastic tubes (Salivette; Sarstedt, Aktiengesellschaft & Co, Nümbrecht, Germany) and stored at 4ºC until further processing. The Salivette tubes were centrifuged in the laboratory (3,000 g for 10 min, 4 °C), and the supernatant collected and stored at –80°C until analysis.

All animals were visually inspected during sampling to assess their physical condition with particular attention paid to the presence of external injuries, bite marks, or signs of fighting. Additionally, a post mortem examination was performed after slaughter to evaluate the integrity of the carcases. No visible lesions or tissue damage were detected in any of the animals (Botía et al. Reference Botía, Escribano, Ortín-Bustillo, López-Martínez, Fuentes, Jiménez-Caparrós, Hernández-Gómez, Avellaneda, Cerón, Rubio, Tvarijonaviciute, Martínez-Subiela, López-Arjona and Tecles2024).

For the proteomic discovery phase, three animals per group were randomly selected from the experimental cohort for TMT-based LC-MS/MS analysis, in line with standard guidelines regarding biological replicate numbers (Westermeier et al. Reference Westermeier, Naven and Höpker2008). The selection was performed among samples that met pre-defined quality criteria (sufficient saliva volume and absence of visible contamination).

For the protein validation phase, an independent set of twelve animals per group (different from those selected for the discovery phase) was randomly chosen from the same cohort to measure cystatin-C and vimentin via immunoassays. No sample overlap occurred between the discovery (TMT) and validation sets.

The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of the University of Murcia, Spain (Comité de Ética en Experimentación Animal protocol code 717/2021) and the Regional Government of the Murcia Region, Spain (CARM protocol A13180601).

Sample preparation for proteomic analysis

The protein concentration of each saliva sample was measured using the BCA Protein Assay (71285-3, Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany). Following this, the samples underwent reduction, alkylation, and digestion, and were labelled with 6-plex TMT reagents following the manufacturer’s protocol (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), with slight adjustments as previously described (Martinez-Subiela et al. Reference Martinez-Subiela, Horvatic, Escribano, Pardo-Marin, Kocaturk, Mrljak, Burchmore, Ceron and Yilmaz2017). Specifically, 35 μg of protein per sample was reduced using 200 mM 1,4-dithiothreitol (DTT) (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA), alkylated with 375 mM iodoacetamide (Sigma-Aldrich), and precipitated overnight with cold acetone (VWR Corp, Radnor, PA, USA). The precipitated samples were centrifuged, and acetone discarded. Protein pellets were reconstituted in 50 μL of 100 mM TEAB buffer and digested overnight at 37°C using trypsin (1 μg per 35 μg of protein; Promega Corp, Madison, WI, USA). The TMT reagents were prepared by equilibration at room temperature, dissolved in 256 μL of acetonitrile (LC-MS grade, Thermo Fisher Scientific), and 19 μL was added to each sample. Labelling was performed for 1 h at room temperature and stopped by adding 5% hydroxylamine (Thermo Scientific) for 15 min. Equal volumes of labelled samples were pooled, and 5 μg aliquots were vacuum dried and stored at –80°C until LC-MS/MS analysis.

Liquid Chromatography — Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) and data processing

The LC-MS/MS analysis was carried out using the Dionex Ultimate 3000 RSLS nano flow system (Dionex, Camberley, UK) in conjunction with the Orbitrap Q Exactive Plus mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific), following the method described by Horvatić et al. (Reference Horvatić, Guillemin, Kaab, McKeegan, O’Reilly, Bain, Kuleš and Eckersall2018). Protein identification and relative quantification were conducted using Proteome Discoverer software (version 2.3, Thermo Fisher Scientific), utilising the SEQUEST search engine to analyse Sus scrofa FASTA files (2024) obtained from the Uniprot/Swissprot database (03/04/2024). Identification criteria included a minimum of two unique peptides per protein and a false discovery rate (FDR) threshold of 1%.

Statistical analysis of proteomic data and Gene Ontology (GO) analysis

All statistics were performed with R v3.2.2 (R Core Team 2015). Proteins with fewer than two unique peptides and those with 100% missing values were excluded from the dataset. For exploratory multivariate visualisation only, data were square-root transformed to stabilise variance and Pareto-scaled to enhance the contribution of medium-variance features while preserving overall data structure. These transformed values were not used for differential abundance testing. For differential analysis, fold-change (FC) values were calculated from normalised but untransformed protein intensities. The FC between the two groups was computed as the ratio of the mean intensity in Group A to the mean intensity in Group B. A threshold of FC ≥ 2 or ≤ 0.5 and a raw P-value < 0.05 were applied to identify proteins showing biologically relevant differences between groups. Raw P-values for differential abundance were generated using Welch’s two-sample t-test, which does not assume equal variances and is appropriate for small sample sizes. To account for multiple testing, a Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) correction was applied. Given the exploratory nature of the study and the limited statistical power (n = 3 per group), an FDR < 0.1 was selected to reduce the risk of type II error and avoid prematurely excluding potentially relevant proteins. Volcano plots were generated using FC values derived from untransformed normalized intensities and their corresponding raw and FDR-adjusted P-values. Protein GI accession numbers were converted to official gene symbols using the DAVID conversion tool (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/conversion.jsp), UniProtKB ID mapping (https://www.uniprot.org/uploadlists/).

Functional classification of the differentially abundant proteins was performed using the PANTHER classification system (http://www.pantherdb.org/). The identified proteins were categorised according to their Gene Ontology (GO) annotations in the three main ontologies (Biological Process, Molecular Function, and Cellular Component) as well as by Pathway.

The functional distribution of proteins within each category was expressed as the percentage of proteins associated with each term, and the results were visualised graphically using the PANTHER functional classification tool.

Proteins quantification validation (cystatin-C and vimentin)

Following the proteomic results, vimentin and cystatin-C were selected for analytical validation. The concentrations of vimentin and cystatin-C were measured in an additional set of 12 saliva samples per group.

Cystatin-C was analysed using an immunoturbidimetric assay based on latex particles coated with an antibody against human cystatin-C (Gentian Diagnostics ASA, Moss, Norway) previously validated (Llamas-Amor et al. Reference Llamas-Amor, Goyena, González-Bulnes, García Manzanilla, Cerón, Martínez-Subiela, López-Martínez and Muñoz-Prieto2024). Six ready-to-use calibrators provided with the commercial kit were employed to establish the standard curve. The assay consumes 5 μL and showed intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation of 3.2 and 4.5%, respectively. Furthermore, the low limit of quantification was set at 0.24 mg L–1 and the limit of detection could not be determined since all measurements with ultrapure water provided negative values.

Vimentin concentrations were measured using a commercial ELISA immunoassay designed for pigs following the manufacturer’s instructions (Pig VIM [vimentin] ELISA kit, orb1088228, Biorbyt, Cambridge, UK). A standard curve was generated with seven calibrators (serially diluted from 100 to 1.57 ng mL–1) and a blank. This assay spends 100 μL of saliva and showed an intra- and inter-assay imprecision less than 8 and 10%, respectively, and a detection limit of 0.61 ng mL–1.

Statistical analysis of cystatin-C and vimentin data

Statistical analysis and graphs of the results obtained were performed using Graph Pad software (GraphPad Prism, version 9 for Windows®, Graph Pad Software Inc, San Diego, USA). The normality of the data was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test, showing a non-normal distribution for both proteins. Therefore, group comparisons were performed using the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test and the results were reported as median and the 25–75th percentiles. Results were expressed as μg mL–1 of cystatin-C and vimentin with significance set at P < 0.05.

Results

Proteomic changes

A total of 288 proteins were identified in saliva. Thirteen proteins showed significant differences in abundance between groups (Table 1). Nine of them showed significantly higher protein abundance in the group in which pigs had more stressful pre-slaughter conditions (Group B) compared to the group for whom pre-slaughter conditions were improved to minimise stress (Group A), namely: small heat shock protein domain-containing protein (HSPB), fructose-biphosphate aldolase (ALDOA), fibrinogen gamma chain, elongation factor Tu, transketolase, fibrinogen alpha chain, alpha-actinin 4, triosephosphate isomerase, and cystatin-C. Conversely, four proteins showed a significant decrease in Group B relative to Group A, namely: follistatin-related protein, IF rod domain-containing protein, aminopeptidase, and prosaposin. Boxplots illustrating the distribution of both original and normalised abundance values for each of these proteins are provided in Figure S1; see Supplementary material.

Table 1. Changes in the salivary proteome of pigs (Sus scrofa domesticus) exposed to two different pre-slaughter conditions (A: improved pre-slaughter conditions, B: stressful pre-slaughter conditions)

Functional classification and GO analysis of differentially abundant proteins

The identified proteins were categorised according to their Gene Ontology (GO) annotations into Biological Process, Molecular Function, and Pathway categories (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Functional classification of differentially abundant pig (Sus scrofa domesticus) salivary proteins identified according to Gene Ontology (GO) using the PANTHER classification system showing categorisation into (a) Biological Process, (b) Molecular Function and (c) Pathway.

Within the Biological Process ontology (Figure 1[a]), the largest proportion of proteins were classified under cellular process (GO:0009987) (30.3%, composed by proteins from TUFM, FSTL1, IF, TKT, ACTN4, HSPB, FGA, PSAP, ALDOA, TPI1 and ANPEP) and metabolic process (GO:0008152) (18.2%, TUFM, TKT, HSPB, FGA, ALDOA, TPI1, ANPEP), followed by biological regulation (GO:0065007) (15.2%, FSTL1, HSPB, FGA, PSAP, CST3), response to stimulus (GO:0050896, HSPB, FGA, PSAP) (9.1%), developmental process (GO:0032502, FSTL1, ACTN4, PSAP) (9.1%), multicellular organismal process (GO:0032501) (9.1%, FSTL1, ACTN4, PSAP), reproductive process (GO:0022414) (3.0%, PSAP), reproduction (GO:0000003) (3.0%, PSAP), and growth (GO:0040007) (3.0%, PSAP).

For Molecular Function (Figure 1[b]), proteins were mainly associated with binding (GO:0005488) (35.7%, TUFM, TKT, ACTN4, HSPB, ANPEP) and catalytic activity (GO:0003824) (28.6%, TKT, ALDOA, TPI1, ANPEP), followed by structural molecule activity (GO:0005198) (14.3%, IF, FGA); while molecular adaptor activity (FGA), translation regulator activity (TUFM), and molecular function regulator activity (CST3) each accounted for 7.1% of the total.

Regarding Pathway (Figure 1[c]), proteins were primarily related to glycolysis (18.2%, ALDOA, TPI1), plasminogen activating cascade (18.2%, FGG, FGA), and blood coagulation (18.2%, FGG, FGA), followed by integrin signalling pathway (P00034) (9.1%, ACTN4), Wnt signalling pathway (P00057) (9.1%, FSTL1), fructose galactose metabolism (P02744) (9.1%, ALDOA), Alzheimer disease-presenilin pathway (P00004) (9.1%, FSTL1), and Cadherin signaling pathway (P00012) (9.1%, FSTL1).

Vimentin and cystatin-C as possible salivary biomarkers of stress

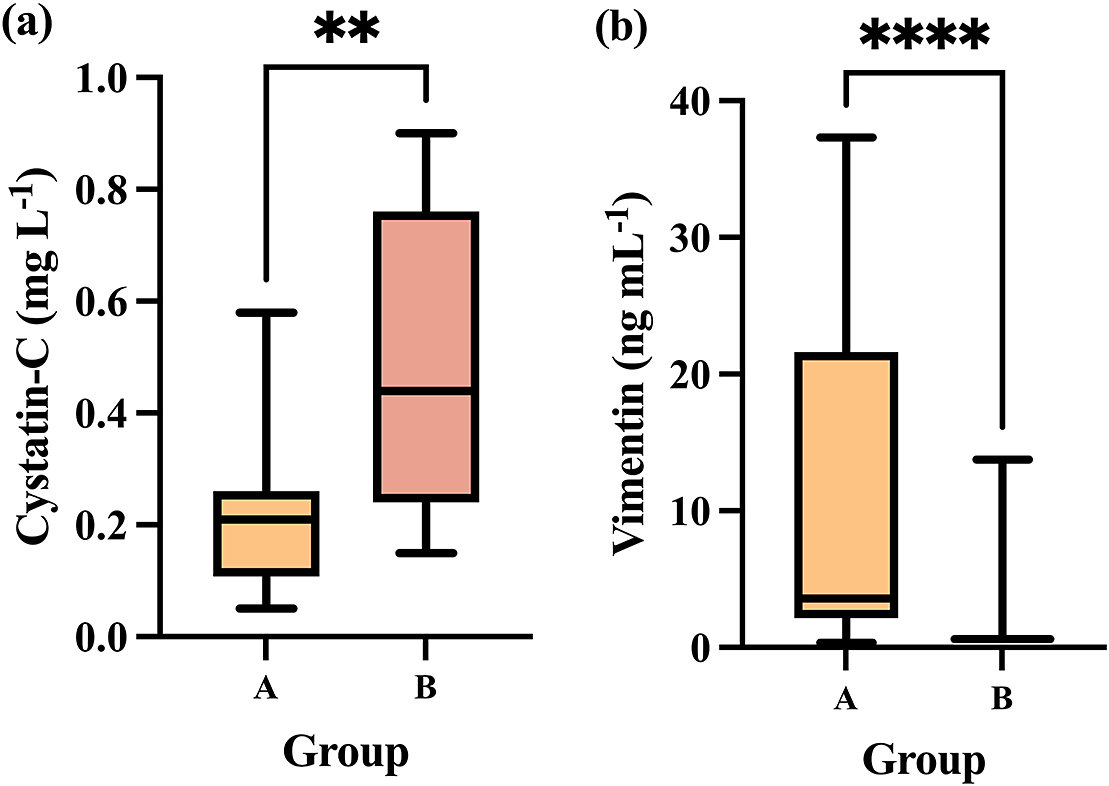

Differences in cystatin-C and vimentin levels between the group in which animals had more stressful pre-slaughter conditions (Group B) compared to Group A in which pre-slaughter conditions were improved to minimise stress are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Showing (a) cystatin-C and (b) vimentin concentrations in Group A (n = 12) compared to Group B (n = 12). The plot shows median (line within box), 25th and 75th percentiles (box) and 5th and 95th percentiles (whiskers). Asterisks indicated significant differences between groups whereby **P < 0.01 and ****P < 0.0001.

Group B showed a significant increase in salivary cystatin-C levels (median, 0.44 μg mL–1; 25–75th percentiles, 0.24–0.76 μg mL–1) compared to Group A (median, 0.21 μg mL–1; 25–75th percentiles, 0.10–0.26 μg mL–1) (P = 0.0065; Figure 2[a]).

In the case of salivary vimentin, the median levels in Group B were significantly lower (median, 0.61 μg mL–1; 25–75th percentiles, 0.61–0.61 μg mL–1) than in Group A (median, 3.58 μg mL–1; 25–75th percentiles, 2.15–21.63 μg mL–1) (P < 0.0001; Figure 2[b]).

Discussion

This study presents a preliminary exploration into salivary proteomic changes in pigs under two pre-slaughter conditions, with the aim of identifying candidate biomarkers indicative of acute stress. Using TMT-based proteomics, 13 differentially expressed proteins were detected, several of which are functionally associated with known stress-response pathways, including inflammation, oxidative stress, energy metabolism, and cytoskeletal regulation. Of these, nine proteins showed a significantly higher concentration in the group subjected to stressful pre-slaughter conditions (Group B), namely: HSPB, ALDOA, fibrinogen gamma chain, elongation factor Tu, transketolase, fibrinogen alpha chain, alpha-actinin 4, triosephosphate isomerase, and cystatin-C.

Collectively, these proteins may serve as indicators of the activation of pivotal physiological systems in response to stress. ALDOA is a ubiquitous metabolic enzyme involved in both glycolysis and gluconeogenesis pathways, playing a key role in energy metabolism (Yu et al. Reference Yu, Liu, Hua, Qiu, Zhang, Wei, Gan, Feng, Shao and Xiong2018). Although ALDOA has been identified as a potential stress-related protein in this study, this elevation could also be associated with greater energy expenditure and muscle activity due to aggressive interactions (fighting) between animals prior to slaughter. Such behaviour-induced metabolic activation may contribute to the observed differences in ALDOA abundance, consistent with its key role in glycolytic energy turnover (Snaebjornsson et al. Reference Snaebjornsson, Poeller, Komkova, Röhrig, Schlicker, Winkelkotte, Chaves-Filho, Al-Shami, Caballero, Koltsaki, Vogel, Frias-Soler, Rudalska, Schwarz, Wolf, Dauch, Steuer and Schulze2025).

Transketolase and triosephosphate isomerase, two additional enzymes related to catalytic processes and glycolysis, also participate in protecting cells from oxidative stress (Henderson & Toone Reference Henderson and Toone1999; Katebi & Jernigan Reference Katebi and Jernigan2013). Stress exposure is known to increase reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and disturb antioxidant defences, which could lead to an increase in these protector proteins (Spiers et al. Reference Spiers, Chen, Sernia and Lavidis2015). The fibrinogen gamma and alpha chains contribute to fibrin polymerisation and cross-linking, and are also involved in the initiation of fibrinolysis, highlighting their role in the coagulation progress (Farrell et al. Reference Farrell, Thiagarajant, Chung and Davie1992; Mosesson Reference Mosesson2003).

During the sampling process and post mortem examination, animals showed no observable lesions or wounds. This observation indicates that stress itself can activate haemostatic pathways and promote hypercoagulability, as has been previously described in the literature (Obeagu Reference Obeagu2025). Alpha-actinin 4, a cytoskeletal protein, facilitates the migration of various cell types involved in the immune response (Kikonomou et al. Reference Kikonomou, Zachou and Dalekos2011). This is consistent with evidence that stress induces the release of hormones and neurotransmitters that modulate the function and movement of immune cells (Alotiby Reference Alotiby2024). In addition, small heat shock proteins (HSPB) act as ATP-independent molecular chaperones that assist in protein folding and are known to play protective roles in diseases characterised by protein aggregation, such as neurodegenerative and neuromuscular diseases, and in stress situations (Boelens Reference Boelens2020; Albinhassan et al. Reference Albinhassan, Alharbi, AlSuhaibani, Mohammad and Malik2025).

Overall, it cannot be completely ruled out that some of the observed protein increases, particularly those related to coagulation and immune modulation, could also be influenced by microinjuries or aggressive interactions (fighting) occurring prior to slaughter. Further experimental evidence would be needed to verify this hypothesis.

The selection of cystatin-C for clinical validation was made based on its status as the most significantly upregulated protein. This protein can be quantified using an automated immunoturbidimetric assay that is commercially available and has previously been validated for porcine saliva (Llamas-Amor et al. Reference Llamas-Amor, Goyena, González-Bulnes, García Manzanilla, Cerón, Martínez-Subiela, López-Martínez and Muñoz-Prieto2024), giving a potential applicability in ‘short-term’ practice. Moreover, to the authors’ knowledge, this is the first report to document salivary cystatin-C alterations in pigs exposed to acute stress. In our study, levels of cystatin-C were approximately 50% higher in Group B compared to Group A, a difference comparable to or greater than that observed for other stress-related biomarkers, such as cortisol or creatine kinase in the same experimental model (Botía et al. Reference Botía, Escribano, Ortín-Bustillo, López-Martínez, Fuentes, Jiménez-Caparrós, Hernández-Gómez, Avellaneda, Cerón, Rubio, Tvarijonaviciute, Martínez-Subiela, López-Arjona and Tecles2024).

Although cystatin-C has not been previously associated with acute stress in pigs, human studies have reported elevated serum levels in individuals with chronic stress, including major depressive disorders (Sun et al. Reference Sun, Chen and Li2021). The relationship between cystatin-C levels and the stress response may be attributed to the fact that this protein can stimulate the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and tumour necrosis factor (TNF), which are known to modulate the HPA axis via effects on central neurotransmitter systems (Zi & Xu Reference Zi and Xu2018; Sun et al. Reference Sun, Chen and Li2021).

Conversely, four proteins showed a significant decrease in relative abundance in the group subjected to more stressful pre-slaughter conditions (Group B), namely: follistatin-related protein, IF rod domain-containing protein (vimentin), aminopeptidase, and prosaposin.

Follistatin is a glycoprotein with hepatokine-like activity, implicated in the regulation of diverse physiological processes such as reproduction, muscle development, cancer progression and metabolism (Jensen-Cody & Potthoff Reference Jensen-Cody and Potthoff2021). Aminopeptidase N (ANPEP) is a multifunctional membrane-bound enzyme involved in antigen processing, immune modulation and the regulation of bioactive peptides (Luan & Xu Reference Luan and Xu2007). Research has shown that lower concentrations of this enzyme in acute stress situations, as found in other species such as rats and bees, may indicate suppressed protective responses, whereas other proteins can be upregulated to compensate for this situation (Gandarias et al. Reference Gandarias, Irazusta, Echevarria, Lagüera and Casis1993; Ferrari et al. Reference Ferrari, Caccia and Polidori2024). Prosaposin is a remarkable, multifunctional protein that operates both intracellularly, where it regulates lysosomal enzyme activity, and extracellularly, acting as a secreted neurotrophic factor with neuroprotective and glioprotective properties (Meyer et al. Reference Meyer, Giddens, Coleman and Hall2014), and which has been observed to decrease in rats subjected to restraint stress (Scaccianoce et al. Reference Scaccianoce, Mattei, Del Bianco, Gizzi, Sorice, Hiraiwa and Misasi2004). Overall, collectively, the downregulated proteins in the high-stress group appear to participate in mechanisms of cellular regulation, protection and homeostasis. Their reduction may reflect impaired or suppressed regulation and protective responses under acute stress conditions, potentially contributing to tissue vulnerability and altered systemic regulation. Nevertheless, further investigation is required to elucidate the mechanism by which these proteins are reduced in situations of stress.

Among the proteins reduced under stress, the intermediate filament (IF) rod domain-containing protein showed the greatest fold change, with a 40.85-fold decrease in Group B, suggesting its potential as a positive indicator of welfare. Intermediate filament proteins are classified into six types with distinct tissue distributions and biological functions. Types I and II (keratins) are expressed exclusively in epithelial cells, where they provide mechanical protection and structural stability (Jacob et al. Reference Jacob, Coulombe, Kwan and Omary2018). Type III proteins, such as vimentin, form the cytoskeletal framework of mesenchymal cells and play fundamental roles in maintaining cell integrity, facilitating cytoskeletal reorganisation, and mediating adaptive responses to cellular stress (Biskou et al. Reference Biskou, Casanova, Hooper, Kemp, Wright, Satsangi, Barlow and Stevens2019). Type IV proteins are neurofilaments found in mature neurons, and type V proteins (lamins) are structural components of the nuclear envelope (Cooper Reference Cooper2000). Finally, type VI proteins, such as nestin, are mainly expressed in progenitor and developing cells, being largely absent from differentiated adult tissues (Guérette et al. Reference Guérette, Khan, Savard and Vincent2007). Type III IFs could be considered as the group of IF more involved in stressful conditions, as they are broadly expressed in tissues directly affected by stress (including muscle, endothelial, and immune cells) and are known to undergo dynamic reorganisation in response to mechanical, oxidative, and endocrine stressors (Cooper Reference Cooper2000; Danielsson et al. Reference Danielsson, Peterson, Araújo, Lautenschläger and Gad2018).

Although vimentin was not specifically quantified in the TMT analysis, it was prioritised for validation as a potential stress-responsive biomarker. It is the predominant type III intermediate filament in mesenchymal tissues and functions as a cytoskeletal ‘stress protein’, rapidly remodelling under oxidative/electrophilic challenge (Toivola et al. Reference Toivola, Strnad, Habtezion and Omary2010; Pattabiraman et al. Reference Pattabiraman, Azad, Amen, Brielle, Park, Sze, Meshorer and Kaganovich2020; Martínez-Cenalmor et al. Reference Martínez-Cenalmor, Martínez, Moneo-Corcuera, González-Jiménez and Pérez-Sala2024). In terms of function, vimentin has been demonstrated to enhance mechanoprotection and resilience to compressive load, while also supporting stress-granule/aggregate handling during periods of cellular stress (Mendez et al. Reference Mendez, Kojima and Goldman2010). Furthermore, an ELISA specific to porcine was available, thus enabling reliable quantification in saliva. This selection does however introduce some interpretative limitations. Since proteomic data alone cannot exclude the involvement of other IF proteins, validating vimentin allowed the examination of a biologically meaningful and analytically feasible marker. Future studies employing higher-resolution proteomics and broader immunoassay coverage will be needed to assess the potential contribution of additional IF proteins to stress responses in pigs.

Quantitative analysis confirmed a statistically significant reduction in vimentin concentrations in pigs exposed to stressful pre-slaughter conditions, with an average decrease of approximately 85% compared to the low-stress group. Notably, this magnitude of change exceeds that observed for other salivary biomarkers previously studied in the same experimental model, including oxytocin (Botía et al. Reference Botía, Escribano, Ortín-Bustillo, López-Martínez, Fuentes, Jiménez-Caparrós, Hernández-Gómez, Avellaneda, Cerón, Rubio, Tvarijonaviciute, Martínez-Subiela, López-Arjona and Tecles2024). One plausible explanation for the observed reduction in vimentin is increased cellular utilisation or degradation of this protein under stress. Recent biomechanical studies have demonstrated that vimentin acts as a mechanical damper of actin-mediated contractility, stabilising cellular tension and reducing variability in stress generation. Therefore, a decrease in vimentin under pre-slaughter stress could compromise this buffering capacity, leading to increased cellular contractility and reduced resilience to physiological stressors (Mendez et al. Reference Mendez, Restle and Janmey2014; Van Loosdregt et al. Reference Van Loosdregt, Weissenberger, Van Maris, Oomens, Loerakker, Stassen and Bouten2018). Alternatively, lower vimentin expression may predispose animals to enhanced sensitivity to stress. Vimentin is known to interact with β3-adrenergic receptors and facilitate lipid mobilisation, including cholesterol transport to mitochondria for glucocorticoid synthesis. Consequently, diminished vimentin levels may attenuate steroidogenesis and weaken the stress response (Shen et al. Reference Shen, Zaidi, Patel, Cortez, Ueno, Azhar, Azhar and Kraemer2012). The elevated vimentin levels observed in the Group A suggests its potential as a ‘positive’ biomarker of welfare, similar to other analytes such as oxytocin, which has also been associated with reduced stress in pigs (López-Arjona et al. Reference López-Arjona, Escribano, Mateo, Contreras-Aguilar, Rubio, Tecles, Cerón and Martínez-Subiela2020). To our knowledge, this is the first report describing vimentin dynamics in porcine saliva under acute stress conditions, and these results support further investigation into its dual role as a structural and regulatory component of the porcine stress response.

The functional classification of the differentially abundant proteins revealed that the main biological processes affected by pre-slaughter stress were cellular and metabolic, together with biological regulation and response to stimulus. These categories are consistent with the physiological activation of energy metabolism and homeostatic control mechanisms under acute stress. In particular, the overrepresentation of proteins associated with blood coagulation and glycolysis pathways suggests a coordinated activation of haemostatic and metabolic systems, which are known to respond rapidly to stress exposure by increasing energy availability and promoting tissue readiness (Obeagu Reference Obeagu2025).

The abundance of proteins with binding and catalytic activity functions, as identified in the GO Molecular Function ontology, also reflects enhanced enzymatic and structural activity in response to stress. Many of these proteins, such as transketolase, triosephosphate isomerase, and fructose-bisphosphate aldolase, are central to energy metabolism and redox balance (Katebi & Jernigan Reference Katebi and Jernigan2013). Furthermore, the presence of cytoskeletal proteins (e.g. actinin, intermediate filament-related proteins) within the most represented functional classes highlights the importance of cytoskeletal reorganisation and cellular resilience in stress adaptation.

Altogether, the GO classification supports the proteomic evidence that pre-slaughter stress alters multiple biological systems, including metabolic, structural, and coagulation-related pathways. These findings emphasise the complex and systemic nature of the stress response, which extends beyond neuroendocrine activation to include immune and oxidative mechanisms detectable in saliva.

Study limitations

First to consider is that the salivary biomarkers were assessed at a single time-point, which may restrict the ability to generalise the results to dynamic or long-term stress responses. Second, the exclusive use of male animals limits the extrapolation of results to female or mixed populations. Third, the proteomic analysis was performed on a relatively small sample size (n = 3 per group), which may reduce statistical power and increase the risk of false positives. Nonetheless, this number aligns with the minimum biological replicates recommended for exploratory proteomic studies (Westermeier et al. Reference Westermeier, Naven and Höpker2008). Fourth, the TMT-based proteomic analysis used in this study provides relative rather than absolute abundance values. This limits the direct interpretation of the results in terms of clinically applicable thresholds. While relative differences are useful for identifying candidate biomarkers, further studies with larger sample sizes and absolute quantification methods are required to establish cut-off values that could reliably indicate stress levels in pigs under pre-slaughter conditions. Additionally, no formal lesion scoring system was applied, and behavioural data and broader environmental conditions were not evaluated, which could provide complementary insights into the physiological findings. However, all pigs were visually inspected during sampling and post mortem examination, and no evident injuries or tissue damage were observed. Despite these limitations, this study offers novel preliminary evidence supporting the potential use of salivary cystatin-C and vimentin as biomarkers of stress in pigs. To our knowledge, this is the first report documenting their behaviour in response to pre-slaughter conditions, laying the groundwork for future validation in more diverse and controlled settings.

Animal welfare implications

The findings of this study highlight the potential of saliva as a non-invasive and practical matrix for assessing stress and welfare in pigs, especially under critical conditions such as those occurring pre-slaughter. By identifying salivary proteins like cystatin-C and vimentin that respond differentially to varying levels of pre-slaughter stress, this research provides novel biomarkers that could be implemented for real-time welfare monitoring on farms or at slaughterhouses. The ability to detect stress-induced physiological alterations without invasive procedures represents a significant advancement in animal welfare science. These biomarkers may support the development of improved pre-slaughter management protocols, contributing to reduced stress, enhanced welfare, and potentially better meat quality outcomes.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that pre-slaughter stress in pigs is associated with distinct changes in the salivary proteome and identifies thirteen proteins with potential as candidate stress biomarkers. These findings were confirmed using commercially available immunoassays in the case of cystatin-C and vimentin, supporting their potential as practical, non-invasive biomarkers. Cystatin-C and vimentin, along with the other eleven candidate proteins, represent valuable potential tools for assessing animal welfare during critical stages of production, although further research is needed to validate these markers across diverse contexts and populations.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/awf.2025.10055.

Acknowledgements

MBG and AOB were funded by Fundación Séneca (Grant reference 21789/FPI/22 and 21603/FPI/21), Región de Murcia, Spain. DE and AMP have postdoctoral fellowships ‘Ramón y Cajal’ (Grant numbers RYC2022-037873-I and RYC2021-033660-I).

Competing interests

None.