Highlights

-

• Being exposed to CM, especially emotional abuse and emotional neglect is associated with impaired resilience in adults.

-

• Age, sample size, study quality, and country/region moderate the association between CM and resilience.

-

• Self-compassion, self-concept, emotional intelligence, social support, parental/peer relationship quality, attachment style, PTSD, and mood symptoms mediate the association between CM and resilience outcomes.

Introduction

Child maltreatment (CM), that is, sexual, physical, and emotional abuse, and physical and emotional neglect, including witnessing domestic violence and bullying exposure under 18 years of age (Cowley et al., Reference Cowley, Lamela, Drabarek, Rodrigues, Ntinapogias, Naughton, Debelle, Alfandari, Jud, Otterman, Laajasalo, Christian, Stancheva-Popkostadinova, Caenazzo, Soldino, Vaughan, Kemp, Nurmatov and Hurt2025; Fares-Otero & Seedat, Reference Fares-Otero and Seedat2024), is one of the most potent and preventable risk factors for the development of physical and mental illnesses throughout the lifespan (Baldwin et al., Reference Baldwin, Wang, Karwatowska, Schoeler, Tsaligopoulou, Munafò and Pingault2023; Mehta et al., Reference Mehta, Kelly, Laurens, Haslam, Williams, Walsh, Baker, Carter, Khawaja, Zelenko and Mathews2023) and is further associated with a multitude of negative psychosocial outcomes in both clinical (Fares-Otero, Alameda et al., Reference Fares-Otero, Alameda, Pfaltz, Martinez-Aran, Schäfer and Vieta2023; Fares-Otero, De Prisco et al., Reference Fares-Otero, De Prisco, Oliva, Radua, Halligan, Vieta and Martinez-Aran2023) and non-clinical populations (Pfaltz et al., Reference Pfaltz, Halligan, Haim-Nachum, Sopp, Åhs, Bachem, Bartoli, Belete, Belete, Berzengi, Dukes, Essadek, Iqbal, Jobson, Langevin, Levy-Gigi, Lüönd, Martin-Soelch, Michael and Seedat2022). However, outcomes of CM vary widely, and not all individuals exposed to CM experience the same level or range of negative health issues or psychosocial consequences. This suggests resiliency in some individuals exposed to CM.

Resilience is the capacity of an individual to adapt successfully to highly adverse events and, by harnessing resources, maintain healthy functioning (Southwick et al., Reference Southwick, Bonanno, Masten, Panter-Brick and Yehuda2014). Resilience can be defined as a personal characteristic (or trait) captured by personal and psychosocial resources, and it can also be perceived as a process comprising bouncing back and growth (Ayed, Toner, & Priebe, Reference Ayed, Toner and Priebe2019). Resilience may also enhance perceptions about one’s personal qualities, such as self-confidence, adaptability, and the ability to endure stress (Choi et al., Reference Choi, Stein, Dunn, Koenen and Smoller2019). As a dynamic system (Liu & Duan, Reference Liu and Duan2023), resilience refers to the ability to function competently and face future challenges or adversities successfully, and can thus be regarded as both the process of returning to pre-exposure health and well-being and an outcome of one’s reaction to a stressful event (Bhatnagar, Reference Bhatnagar2021).

To date, previous systematic reviews have reported on factors that promote adaptive functioning and positive mental health (Fritz et al., Reference Fritz, de Graaff, Caisley, van Harmelen and Wilkinson2018; Meng et al., Reference Meng, Fleury, Xiang, Li and D’Arcy2018) but were not able to draw firm conclusions on resilience factors contributing to improved psychosocial outcomes in adults with CM (Latham, Newbury, & Fisher, Reference Latham, Newbury and Fisher2023). One meta-analysis examined associations between violence exposure and protective factors for resilience in children, showing that self-regulation and social support demonstrated significant additive and/or buffering effects in longitudinal studies (Yule, Houston, & Grych, Reference Yule, Houston and Grych2019). A multivariate meta-analysis found that trait resilience mediated the association between childhood trauma and depression (Watters, Aloe, & Wojciak, Reference Watters, Aloe and Wojciak2023). An umbrella synthesis of meta-analyses on CM antecedents and interventions found that resilient individuals were characterised by lower susceptibility to changes in the environment and that these associations between resilience and susceptibility were moderated by constitutional (e.g. easy temperament) and contextual protective factors (e.g. parent intervention) (van IJzendoorn, Bakermans-Kranenburg, Coughlan, & Reijman, Reference van IJzendoorn, Bakermans-Kranenburg, Coughlan and Reijman2020).

Although the association between CM and resilience has been widely recognised, available reviews (Fritz et al., Reference Fritz, de Graaff, Caisley, van Harmelen and Wilkinson2018; Latham et al., Reference Latham, Newbury and Fisher2023; Meng et al., Reference Meng, Fleury, Xiang, Li and D’Arcy2018) and meta-analyses (van IJzendoorn et al., Reference van IJzendoorn, Bakermans-Kranenburg, Coughlan and Reijman2020; Watters et al., Reference Watters, Aloe and Wojciak2023; Yule et al., Reference Yule, Houston and Grych2019) have focused on broader concepts of childhood adversity and protective factors that promote resilience. It remains unclear whether CM and its specific subtypes are differentially associated with resilience in adulthood using a multi-domain definition and approach for resilience (Fares-Otero, O et al., Reference Fares-Otero, O, Spies, Womersley, Gonzalez, Ayas, Mossie, Carranza-Neira, Estrada-Lorenzo, Vieta, Schalinski, Schnyder and Seedat2023). Furthermore, analyses of potential moderating (e.g. age, sex, mental condition) or mediating factors (e.g. personality, mood symptoms) in the association between CM and resilience have seldom been undertaken.

This systematic review and meta-analysis sought to address these gaps by determining whether overall CM and its subtypes are associated with global/trait resilience and distinct resilience domains (coping, self-esteem, emotion regulation, self-efficacy, and well-being) in adults. The review also explored potential moderators that may modify the strength and/or direction of the association between CM and resilience, and mediators that may explain the association. Understanding CM-resilience associations can guide clinical decision-making or policy development. Collectively, this information can inform clinical practice guidelines and strategies for improving prediction, early identification, and targeted interventions.

Methods

Protocol

The study protocol was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42023394120) and published elsewhere (Fares-Otero, O et al., Reference Fares-Otero, O, Spies, Womersley, Gonzalez, Ayas, Mossie, Carranza-Neira, Estrada-Lorenzo, Vieta, Schalinski, Schnyder and Seedat2023) before the completion of the study. This review follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (Moher et al., Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman2009; Page et al., Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann, Mulrow, Shamseer, Tetzlaff, Akl, Brennan, Chou, Glanville, Grimshaw, Hróbjartsson, Lalu, Li, Loder, Mayo-Wilson, McDonald and Moher2021) (see ST1 and ST2 in the Supplement), the Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE; Stroup et al., Reference Stroup, Berlin, Morton, Olkin, Williamson, Rennie, Moher, Becker, Sipe and Thacker2000) checklist (see ST3 in the Supplement), and the Enhancing the Quality and Transparency of Health Research (EQUATOR) (Altman et al., Reference Altman, Simera, Hoey, Moher and Schulz2008) reporting guidelines. For a comprehensive glossary of terms used in this work, see SA1 in the Supplement.

Search strategy and selection criteria

A systematic search using multiple medical subject headings (MeSH), terms, and keywords related to (1) ‘childhood maltreatment’ and ‘resilience’ (domains) using the Boolean operator ‘AND’ adapted according to database thesauruses (see the search strategies and terms appended in SA2 in the Supplement) was implemented on PubMed (Medline), PsycINFO, Embase, Scopus, and Web of Science (core collection) to identify relevant studies on 18 April 2023 and updated on 12 June 2024. No language or date limits were applied. To identify additional eligible studies, references of studies of relevance were cross-referenced manually. This backward and forward citation searching was carried out in PubMed and Google Scholar (NEF-O).

Four independent reviewers (NEF-O, JC-N, JSW, GS) screened the titles and abstracts according to the pre-specified eligibility criteria and discrepancies were resolved through consensus. Articles, that appeared eligible from the abstract, or were of unclear eligibility, were full-text screened (NEF-O, JC-N, JSW, GS). Any disagreements over study eligibility were discussed and an independent senior researcher (SS) was consulted if a consensus could not be reached among the reviewers. Rayyan QCRI software (https://rayyan.qcri.org/) was used to manage citations, remove duplicates, and screen titles and abstracts.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Only original research articles published in peer-reviewed journals were included. Eligible studies reported quantitative associations between at least one CM subtype (exposure variable; i.e. sexual, physical, or emotional abuse; physical or emotional neglect, domestic violence, bullying) and at least one resilience domain (outcome variable; i.e. global/trait resilience, coping, self-esteem, emotion regulation, self-efficacy, well-being) in adults (see the definition and operationalisation of exposure and outcome variables in SA3 in the Supplement). When more than one published study used the same subjects and outcomes, the study with the larger sample size was chosen to maximise power.

Studies were excluded if they: (1) were reviews, meta-analyses, clinical case studies, abstracts, conference proceedings, study protocols, letters to the editor not reporting original data, editorials, commentaries, theoretical pieces, books, book chapters, preprints, theses, or grey literature; (2) only included children and/or adolescents; (3) were studies that exclusively assessed trauma experienced in adulthood (≥ 18 years); (4) were qualitative studies; (5) aimed to conduct or evaluate an intervention and/or to assess treatment outcomes and did not provide baseline data.

According to the PECOS (Population, Exposure, Comparator, Outcomes, Study design) framework (Morgan, Whaley, Thayer, & Schünemann, Reference Morgan, Whaley, Thayer and Schünemann2018), studies were included if they: (1) (P) were conducted on human adults (≥ 18 years) with or without current/past mental or any medical condition and who were exposed to CM; (2) (E) assessed the presence of CM (< 18 years) and measured overall (total) or specific CM subtypes with validated measures or through clinical interviews/reports; (3) (C) compared individuals with and without CM within the same sample; (4) (O) evaluated resilience with validated instruments; (5) quantitatively examined and reported associations between CM and resilience or data that allowed correlations to be calculated or provided these data on request; (6) (S) were cross-sectional, or longitudinal (providing baseline data).

Study outcomes

The selection of resilience (outcome) domains was based on resilience outcomes examined in the included studies, and categorisations used in the trauma and resilience research fields (Rutten et al., Reference Rutten, Hammels, Geschwind, Menne-Lothmann, Pishva, Schruers, Schruers, Hove, Kenis, Os and Wichers2013; Southwick et al., Reference Southwick, Bonanno, Masten, Panter-Brick and Yehuda2014). After study selection, we categorised the study outcomes into: (I) Global or trait resilience : conceived as a relatively stable, personal innate characteristic that is marked by psychological hardiness, and ego resilience (Connor & Davidson, Reference Connor and Davidson2003); and (II) Five separate domains of resilience, including: (1) Coping: conscious, volitional efforts to regulate emotion, cognition, behaviour, physiology, and the environment in response to stress (Bonanno, Romero, & Klein, Reference Bonanno, Romero and Klein2015; Bonanno, Westphal, & Mancini, Reference Bonanno, Westphal and Mancini2011); (2) Self-esteem: one’s overall sense of self-worth or personal value that represents a comprehensive evaluation of oneself, including positive and negative evaluations (Brown, Dutton, & Cook, Reference Brown, Dutton and Cook2001); (3) Emotion regulation: the process by which individuals influence the occurrence, timing, nature, experience, and expression of their emotions (Kok, Reference Kok, Zeigler-Hill and Shackelford2020); (4) Self-efficacy: sense of perceived self-efficacy to cope with daily hassles and stresses and adapt after experiencing all kinds of stressful life events, including a person’s belief in their ability to complete a task or achieve a goal (Bandura, Reference Bandura1982); (5) Well-being: biological and psychological qualities of well-being and mental health that enable successful adaptation or swift recovery from life adversity, such as optimism, a sense of coherence, the experience of positive emotions, having a purpose in life, and a sense of mastery (Ruggeri et al., Reference Ruggeri, Garcia-Garzon, Maguire, Matz and Huppert2020; Rutten et al., Reference Rutten, Hammels, Geschwind, Menne-Lothmann, Pishva, Schruers, Schruers, Hove, Kenis, Os and Wichers2013).

Appendix SA4 in the Supplement provides a complete definition and operationalisation of each outcome domain and ST4 provides a complete overview of assessments of each outcome domain.

Data extraction and study quality assessment

Data from eligible studies were extracted and tracked in Microsoft Excel by two groups of independent reviewers in the initial (NEF-O, JC-N, JSW, and GS) and updated search (NEF-O, JC-N, JSW, AS, and GS) using a structured coding form.

Descriptive variables extracted comprised demographics, and measurement instruments for CM, and resilience domains (see a detailed description of the extracted variables in SA3 in the Supplement). Correlation coefficients (r) were extracted as measures of effect size index. If not reported in the original publication, information was calculated from available statistics using established formulas (Lenhard & Lenhard, Reference Lenhard and Lenhard2017; Lipsey & Wilson, Reference Lipsey and Wilson2001) or was requested from the authors.

The included studies were assessed for study quality by two groups of independent reviewers for the initial (JN-C, JSW, and GS) and updated search (JN-C, JSW, AS, IS, and GS) using a modified version of the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for non-randomised studies as used in previous meta-analyses in the field (Fares-Otero, Alameda et al., Reference Fares-Otero, Alameda, Pfaltz, Martinez-Aran, Schäfer and Vieta2023; Fares-Otero, De Prisco et al., Reference Fares-Otero, De Prisco, Oliva, Radua, Halligan, Vieta and Martinez-Aran2023). When using the NOS, studies are rated depending on sample selection, comparability of groups, and assessment of exposure or outcome, and the adapted version contains additional items to assess sample size, confounders, and statistical tests as recommended by the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins et al., Reference Higgins, Altman, Gøtzsche, Jüni, Moher, Oxman, Savović, Schulz, Weeks and Sterne2011) (see ST5 in the Supplement).

Any disagreements over data extraction and/or study quality were discussed, and the lead researcher (NEF-O) was consulted if a consensus could not be reached, with discrepancies resolved through general consensus.

Statistical analysis

Random-effect meta-analyses were conducted when a minimum of five studies (Jackson & Turner, Reference Jackson and Turner2017) were available. If the number of available effect sizes did not allow random effects meta-analysis, study findings were summarised and appraised qualitatively in a narrative synthesis (Popay et al., Reference Popay, Roberts, Sowden, Petticrew, Arai, Rodgers, Britten, Roen and Duffy2006). For those studies not reporting correlation coefficients, information was transformed from available statistics (e.g. mean and standard deviations between groups comparisons, regression coefficients) (Lenhard & Lenhard, Reference Lenhard and Lenhard2017). Pearson correlation coefficients (effect sizes) were Fisher’s Z transformed to stabilise the variance and calculate reliable confidence intervals (CIs) and back transformed after pooling to allow for clearer interpretation, as per procedures used in previous meta-analyses (Fares-Otero, Alameda et al., Reference Fares-Otero, Alameda, Pfaltz, Martinez-Aran, Schäfer and Vieta2023; Fares-Otero, De Prisco et al., Reference Fares-Otero, De Prisco, Oliva, Radua, Halligan, Vieta and Martinez-Aran2023). Thus, all pooled effects were reported as correlation coefficients.

For the studies conducting separate analyses for emotion regulation subscales (i.e. acceptance, refocus on planning, positive reappraisal, expressive suppression, rumination, and experiential avoidance) (Güler, Demir, & Yurtseven, Reference Güler, Demir and Yurtseven2024; Mohammadpanah Ardakan, Khosravani, Kamali, & Dabiri, Reference Mohammadpanah Ardakan, Khosravani, Kamali and Dabiri2024; Musella et al., Reference Musella, DiFonte, Michel, Stamates and Flannery-Schroeder2024; Peng et al., Reference Peng, Liu, Liu, Chu, Zheng, Wang, Wei, Zhong, Ling and Yi2021; Sistad, Simons, Mojallal, & Simons, Reference Sistad, Simons, Mojallal and Simons2021), results were pooled using correction estimates (Olkin & Pratt, Reference Olkin and Pratt1958) before inclusion in the meta-analysis.

The heterogeneity of effect estimates was investigated using Cochran’s Q-test and I 2 statistics (Higgins, Thompson, Deeks, & Altman, Reference Higgins, Thompson, Deeks and Altman2003). The between-study variance of the underlying distribution of true effect sizes were reported using the tau square (τ 2) statistic. Alongside the 95% CIs and the mean pooled effect provided, the prediction intervals estimating the extent to which effect sizes vary across studies (Borenstein, Reference Borenstein2022b) were displayed as part of the forest plots (marked in red).

Additionally, the heterogeneity and content of studies were qualitatively described and possible reasons for the variability were considered by analysing the characteristics of the studies included. Meta-regressions for pre-defined continuous variables were conducted, including age (mean years), sex (% males), and the influence of sample size and study quality (NOS rating). Individual subgroup analyses were conducted for categorical variables, that is, western (EU and Scandinavian countries, the United Kingdom, Iceland, the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand) versus non-western countries (Asia, Africa, Latin America, Eastern Europe, Middle East), clinical samples (the presence of any diagnosis of mental disorders, according to DSM (Bell, Reference Bell1994; Kübler, Reference Kübler, Gellman and Turner2013) or ICD (World Health Organisation, 2019) criteria, versus non-clinical samples (subjects recruited from the community and who were not diagnosed with a disorder). Subgroup analyses used a mixed-effects model (a random-effects model within subgroups and a fixed-effect model across subgroups). Other evidence of confounders and effect moderators and mediators on associations between CM and resilience outcomes was narratively synthesised (Popay et al., Reference Popay, Roberts, Sowden, Petticrew, Arai, Rodgers, Britten, Roen and Duffy2006).

One-study-removed sensitivity analyses were conducted to determine whether a particular study or a set of studies were contributing to potential heterogeneity and to determine the robustness of the meta-analyses (Higgins & Thompson, Reference Higgins and Thompson2004).

For any meta-analysis with ≥10 studies, funnel plot asymmetry (Egger, Smith, Schneider, & Minder, Reference Egger, Smith, Schneider and Minder1997) was visually evaluated and possible explanations for the asymmetry were considered (small-study effects, publication bias). Publication bias was also assessed and quantified by Egger’s linear regression asymmetry test (Sterne, Gavaghan, & Egger, Reference Sterne, Gavaghan and Egger2000). Given that these tests might be underpowered if only a small number of studies are available, the non-parametric trim-and-fill method (Duval & Tweedie, Reference Duval and Tweedie2000) was used to examine the extent to which publication bias may contribute to the meta-analysis results if the search yielded few studies. Risk of bias analyses used a random-effects model, while a fixed-effect model was used to determine missing studies.

Statistical significance was evaluated two-sided at the 5% threshold (two-tailed). Interpretation of correlation coefficients was based on pre-defined cut-offs as follows: r values between 0 and 0.3 indicate small, values between 0.3 and 0.7 indicate moderate, and values above 0.7 indicate strong associations (Ratner, Reference Ratner2009).

All quantitative analyses were performed using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis v4.0 (CMA, version 4-meta-analysis.com) (Borenstein, Reference Borenstein2022a) and R version 4.1.2 (RStudio Team, 2020). The figure illustrating the results of the meta-analytic synthesis was created using the ggplot2 package.

Results

Study selection

From 15,262 identified records (15,240 through databases and 22 studies through manual searches), 482 were full-text screened, and 203 studies were included in the qualitative synthesis, of which 183 were included in the quantitative synthesis, contributing to 557 effect sizes pooled in meta-analyses (see the process of study selection in detail in Figure 1, the full list of included studies in SA5, and the full list of excluded studies with reasons in SA6 in the Supplement).

Figure 1. PRISMA 2020 flowchart outlining the study selection process.

Characteristics of the included studies

The 203 included studies were published between 1994 and 2024 and were conducted in North America (n = 64), Asia (n = 45), Europe (n = 39), Turkey (n = 22), Middle East (n = 14), Oceania (n = 5), Latin America (n = 4), and Africa (n = 1), with a total of 101 (49.75%) studies conducted in western-countries, 93 (45.81%) studies conducted in non-western countries, and nine studies conducted in multiple countries/regions.

Most of the included studies were cross-sectional, except for 15 (7.39%) studies (Armitage et al., Reference Armitage, Wang, Davis, Bowes and Haworth2021; Billen et al., Reference Billen, Garofalo, Schwabe, Jeandarme and Bogaerts2023; Chen, Shen, & Dai, Reference Chen, Shen and Dai2021; Daniels et al., Reference Daniels, Hegadoren, Coupland, Rowe, Densmore, Neufeld and Lanius2012; Dereboy, Sahin Demirkapi, Sakiroglu, & Safak Ozturk, Reference Dereboy, Sahin Demirkapi, Sakiroglu and Safak Ozturk2018; ElBarazi, Reference ElBarazi2023; Guo et al., Reference Guo, Gu, Gaskin, Yin, Zhang and Wang2023; Herrenkohl et al., Reference Herrenkohl, Klika, Herrenkohl, Russo and Dee2012; Jones, Marsland, & Gianaros, Reference Jones, Marsland and Gianaros2023; Kong, Homan, & Goldberg, Reference Kong, Homan and Goldberg2024; Kumar et al., Reference Kumar, Brockdorf, Jaffe, Church, Messman and DiLillo2022; S. Liu et al., Reference Liu, Ahemaitijiang, Xu, Liu, Chen and Han2023; Martin et al., Reference Martin, Renshaw, Mauro, Curby, Ansell and Chaplin2023; Salles et al., Reference Salles, Stephan, Molière, Bennabi, Haffen, Bouvard, Walter, Allauze, Llorca, Genty, Leboyer, Holtzmann, Nguon, D’Amato, Rey, Horn, Vaiva, Fond, Richieri and Yrondi2024; Sexton et al., Reference Sexton, Hamilton, McGinnis, Rosenblum and Muzik2015) with a longitudinal design.

The total sample of the included studies comprised 145,317 (range = 30–25,113) adults, of which 34.96% were males. The mean age was 29.62 (range = 18.25–72.24) years. Of the 2023 included studies, 78 (38.42%) studies were carried out in clinical samples, of which 55 (27.09%) reported the presence of any diagnosis of mental disorders according to DSM (Bell, Reference Bell1994; Kübler, Reference Kübler, Gellman and Turner2013) or ICD (World Health Organisation, 2019) criteria. Three (1.48%) studies were conducted in samples with physical conditions (Artime & Peterson, Reference Artime and Peterson2012; Crosta et al., Reference Crosta, De Simone, Di Pietro, Acanfora, Caldarola, Moccia, Callea, Panaccione, Peris, Rinaldi, Janiri and Di Nicola2018; Kızılkurt, Demirkan, Gıynaş, & Güleç, Reference Kızılkurt, Demirkan, Gıynaş and Güleç2021).

Overall CM was examined in 122 (60.09%) of the included studies, while 91 (44.83%) studies examined emotional abuse, 89 (43.84%) studies examined physical abuse, 97 (47.78%) studies examined sexual abuse, 66 studies (32.51%) examined emotional neglect, while 53 (26.11%) studies examined physical neglect. Bullying (or peer victimisation) was examined in 13 (6.40%) studies, and domestic violence exposure was examined in 11 (5.42%) studies.

Most of the included studies included retrospective assessments of CM. The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) short-form (28 items) was used in 141 (69.46%) studies, including shortened (25 items) or translated versions; while structured clinical interviews were used in seven (3.45%) studies and official case record reviews were used in three (1.48%) studies.

Forty-eight (23.65%) studies controlled for confounders in their analysis with a wide range of confounders being considered, including sex/gender, age, race/ethnicity, household characteristics, health measures, additional traumas, substance abuse, and mood symptoms. See further descriptive characteristics of the included studies in Table 1.

Table 1. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the included studies

Note: See the full list and complete publication details of the included studies in SA5 in the Supplementary Material.

Abbreviations: AAQ-II, The Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II; ABS, The Affect Balance Scale; ACE-Q, Adverse Childhood Experiences Questionnaire; ADHD, Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder; ALSPAC, Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children; AMS, Academic Motivation Scale; AnxNOS, Anxiety Disorder Not Otherwise Specified; ARM, Adult Resilience Measure; ASD, Acute Stress Disorder; ATQ, Adult Temperament Questionnaire-Short Form; AUD, Alcohol Use Disorder; BD, Bipolar Disorder; BERQ, Behavioural Emotion Regulation Questionnaire; BFIS-9, Bullying and friendship interview schedule-9; BPD, Borderline Personality Disorder; BPNSS, Basic Psychological Needs Scale; Brief-COPE, The Brief Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced Inventory; Brief RCOPE, The Brief Religious Coping Activities Scale; BRS, The Brief Resilience Scale; BSCS, The Brief Self-Control Scale; BSE, The Beck Self-Esteem Scale; BSI, Brief Symptom Inventory; CAP, Child Abuse Potential Inventory; CAQ, Childhood Abuse Questionnaire; CAs, College Adjustment Scale; CAS, Childhood Abuse Scale; CASRS, The Child Abuse and Self Report Scale; CATS, The Child Abuse and Trauma Scale; CCHS-MH, Canadian Community Health Survey-Mental Health; CCMS, Comprehensive Child Maltreatment Scale; CD-RISC, The Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale; CEDV, Child Exposure to Domestic Violence; CERQ, Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire; CERQ-Short, Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire-Short Version; CEVQ, Childhood Experiences of Violence Questionnaire; CFSEI-2, Culture-Free Self-Esteem Inventory; CIDI, Composite International Diagnostic Interview; CISS, Coping Inventory for Stressful Situation; CM, Childhood Maltreatment; CMIS, Childhood Maltreatment Interview Schedule; CMIS-SF, Child Maltreatment Interview Schedule – Short Form; COPE, Coping Orientations to the Problems Experienced; CSAQ, Childhood Sexual Abuse Questionnaire; CSEI, Coopersmith Self-Esteem Inventory; CSI, Coping Strategies Inventory; CSI-SF, Coping Strategies Inventory–Short Form; CTI, Childhood Trauma Interview; CTQ, Childhood Trauma Questionnaire; CTQ-SF, Childhood Trauma Questionnaire-Short Form; CTs, Conflict Tactics Scale; CTS, Childhood Trauma Screener; CTS-33, Childhood Trauma Scale-33; CTs Form-R, Conflict Tactics Scales Form R; CTs-PC, Parent–Child Conflict Tactics Scales; CW, Coping Wheel; DD-NOS, Depressive Disorder Not Otherwise Specified; DEQ-SC, Depressive Experiences Questionnaire Self-Criticism; DERS, Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale; DERS-SF, Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale–Short Form; DSM, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; DSQ, The Defense Style Questionnaire; DTS, Distress Tolerance Scale; DUKE, The Duke Health Profile; DV, Domestic Violence; EA, Emotional abuse; EAIA, Child Abuse Scale for Adults; EDS, Emotional Dysregulation Scale; EN, Emotional neglect; ERDS, Emotion Regulation Difficulty Scale-Short Form; ER, Emotion Regulation; ERPS, Emotion Regulation Process Scale; ERQ, Emotional Regulation Questionnaire; ERQ-CA, Emotion Regulation Questionnaire-modified version; ERS, Emotion Regulation Scale; ETISR-SF, Early Trauma Inventory Self-Report-Short Form; FAM, Feelings and Me Questionnaire; FCVQ, Finkelhor Childhood Victimisation Questionnaire; FFMQ, Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire; FSHQ, Family and Sexual History Questionnaire; GAD, General Anxiety Disorder; GHQ, General Health Questionnaire; GSAD, Generalised social anxiety disorder; GSES, General Self-Efficacy Scale; HCs, Healthy controls; HFS, The Heartland Forgiveness Scale; HIV, Human immunodeficiency virus; HOPES, Hunter Opinions and Personal Expectations Scale; IBS, Impulsive Behaviour Scale; ICAST-R, The ISPCAN Child Abuse Screening Tools Retrospective-Version; ICES, Invalidating Childhood Environments Scale; ID, Identification; IPV, Intimate Partner Violence; LOC, The Locus of Control of Behaviour; LOCS, Levels of Self Criticism Scale; LOT-R, Life Orientation Test-Revised; LSC-R, Life Stressor Checklist-Revised; MASQ, Mood and Symptoms Questionnaire; MDD, Major Depressive Disorder; MEMS, Multidimensional Existential Meaning Scale; MHC-SF, Mental Health Continuum-Short Form; MIDUS, Midlife in the United States study; MLQ, Meaning in Life Questionnaire; MPLS, Meaning and Purpose of Life Scale; MPQ, Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire; NA, Not Available; NMR, General Expectancy for Negative Mood Regulation Scale; OBVQ, Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire; OCD, Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder; OCPD, Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorder; OUD, Opioid Use Disorder; PA, physical abuse; PANAS, The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule; PD, Personality Disorder; PDS, Post-Traumatic Stress Diagnostic Scale–Part I; PECK, Personal Experiences Checklist; PLEs, Psychotic-like experiences; PMQ, Psychological Maltreatment Questionnaire; PMR, The Psychological Maltreatment Review; PMS, Pearlin Mastery Scale; PN, Physical neglect; PSI, Personal Style Inventory; PTGI, Post-traumatic Growth Inventory; PTGI-SF, Post-traumatic Growth Inventory-Short Form; PTM, Prosocial Tendencies Measure; PTSD, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder; PVS, Personal View Survey; RBQ, Retrospective Bullying Questionnaire; RES, Resilience; RLOC, Rotter’s Locus of Control Scale; RESE, Regulatory Emotional Self-Efficacy Scale; RPS, Religious Practice Scale; RS, Resilience Scale; RSA, The Resilience Scale for Adults; RSES, Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale; RSQ, Response Style Questionnaire; SA, Sexual abuse; SACQ, Student Adaptation to College Questionnaire; 3S, Self-Satisfaction Scale; SAS, Severity of Abuse Scale; SCC, Self-Concept Clarity Scale; SCRS, Self-Critical Rumination Scale; SCS, Self-Compassion Scale; SCSQ, The Simplified Coping Style Questionnaire; SCS-SF, The Self-Compassion Scale-Short Form; SD, Standard deviation; S-DERS, State Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale; SDS-R, Self-Disgust Scale Revised; SE, Self-esteem; SEQ, Sexual Events Questionnaire; SES, Socioeconomic status; SESBW, Self-Efficacy Scale for Battered Women; SES-SFV, Sexual Experiences Survey–Short Form Victimisation Revised; SHS, Subjective Happiness Scale; SLCS, Self-Liking/Self-Competence Scale; SOCS, Sense of Coherence Scale; SPRS, Short Psychological Resilience Scale; SPSI-R, The Social Problem-Solving Inventory-Revised Short Form; SRI-25, Suicide Resilience Inventory-25; SRQ, Sibling Relations Questionnaire; SSHH, Stress, Spirituality, and Health Questionnaire; STI, Sexually transmitted infection; STS, The Spiritual Transcendence Scale; SUBI, Subjective Well-being Inventory; SUD, Substance use disorder; SVCQ, Sexually Victimised Children Questionnaire; SWBS, Spiritual Well-Being Scale; SWLS, Satisfaction with Life Scale; SWS, Subjective-Well-being Scale; TADS, Trauma Distress Scale; TCAQ, The Cognitive Avoidance Questionnaire; THS, The Hope Scale; TRD, Treatment-resistant depression; TSCS, Tennessee Self-Concept Scale; TSEI, Taylor Self-Esteem Inventory; TSES, The Self-Efficacy Scale; TSPWB, The Scales of Psychological Well-Being; TSS, The Self Scale; UPPS-P, Urgency, Premeditation, Perseverance, Sensation seeking, and Positive urgency; USA, United States of America; WB, Well-being; WCQ, Ways of Coping Questionnaire; WEMWBS, Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale; WHO-5, The World Health Organisation-Five Well-Being Index; WSHQ, The Wyatt Sexual History Questionnaire.

a Studies with asterisk and row marked in grey signify not included in meta-analysis but fulfilling inclusion criteria and included in the systematic review (see also a description of main results and qualitative synthesis in SA7 in the Supplement).

b Studies with a cross signify carried by same authors and involving the same sample, but assessing different outcomes and included in separated meta-analyses.

Among the 203 studies reviewed, 20 studies were only included in the systematic review. For a description and qualitative synthesis of the main results of CM and resilience domain associations that provided insufficient data for meta-analyses, see SA7 in the Supplement.

Study quality

The mean quality rating (range = 0–8) of the included studies was 5.48 (range = 4–8). Overall, 52 (25.62%) studies were rated as ‘poor’ (NOS score = 3 or 4), 55 (27.09%) studies were rated as ‘fair’ (NOS score = 5), 45 (22.17%) studies were rated as ‘good’ (NOS score = 6), and 51 (25.12%) studies received a rating considered as ‘high’ (NOS score > 6) (see further details of the study quality assessment in ST5 in the Supplement).

Meta-analytic results of associations between CM and resilience in adulthood

Separate meta-analyses with random-effects estimates were calculated to quantify associations between CM, separated by overall and subtypes, global/trait resilience (n = 90, k = 98), and five resilience domains: (1) Coping (n = 23, k = 26), (2) Self-esteem (n = 133, k = 154), (3) Emotion regulation (n = 192, k = 192), (4) Self-efficacy (n = 34, k = 34), and (5) Well-being (n = 52, k = 53). The main results are presented in Table 2 and illustrated in Figure 2. Forest plots of each analysis can be found in SF1 in the Supplement.

Table 2. Meta-analyses of associations between CM and resilience outcomes in adulthood

Note: *Different populations from the same study were included in meta-analysis; statistical significance p < 0.05.

Figure 2. Overall results of the meta-analytic synthesis.

Global/trait resilience

Overall CM and all subtypes were negatively associated with global/trait resilience (r = −0.091 to −0.305; p = .002 to <.001). Emotional neglect showed the largest magnitude of effect (n = 12, k = 13, r = −0.305, p < .001).

Resilience domains

Coping

Overall CM (n = 9, k = 10; r = −0.156, p = .018) and physical abuse (n = 6, k = 7; r = −0.143, p = .003) were negatively associated with coping but unrelated to sexual abuse.

Self-esteem

Overall CM and most subtypes were negatively associated with self-esteem (r = −0.110 to −0.303, p < .001), except for physical abuse and physical neglect. Emotional abuse showed the largest magnitude of effect (n = 21, k = 24; r = −0.303, p < .001).

Emotion regulation

Overall CM and all subtypes were negatively associated with emotion regulation (r = −0.150 to −0.272, p < .001). Emotional abuse (n = 38, k = 38; r = −0.272, p < .001) and emotional neglect showed the largest magnitude of effect (n = 24, k = 24; r = −0.272, p < .001).

Self-efficacy

Overall CM and all subtypes were negatively associated with self-efficacy (r = −0.081 to −0.330, p = 0.048 to < .001). Emotional neglect showed the largest magnitude of effect (n = 5, k = 5; r = −0.321, p < .001).

Well-being

Overall CM and all subtypes were negatively associated with well-being (r = −0.142 to −0.310, p < .001). Emotional neglect showed the largest magnitude of effect (n = 6, k = 6; r = −0.310, p < .001).

Heterogeneity, meta-regressions

Of the 33 meta-analyses completed, heterogeneity was high for most results (see results on heterogeneity in Table 2).

Meta-regressions were conducted by overall CM and CM subtypes. The following continuous variables were explored: (1) mean age; (2) proportion of males; (3) sample size; and (4) study quality (NOS score).

Global/ trait resilience

The magnitude of the association between sexual abuse and global/trait resilience decreased with sample size (n = 12, k = 12, B = −0.000, 95% CI [−0.021; 0.002], p = 0.018) and increased with study quality (n = 12, k = 12, B = 0.161, 95% CI [0.073; 0.249], p < 0.001).

Resilience domains

Coping: the magnitude of the association between overall CM and coping increased with sample size (n = 7, k = 7, B = 0.001, 95% CI [0.000; 0.001], p < 0.001) and decreased with age (n = 7, k = 7, B = −0.001, 95% CI [−0.000; −0.000], p = 0.003) and study quality (n = 7, k = 7, B = −0.091, 95% CI [−0.164; −0.018], p = 0.014). The association between physical abuse and coping decreased with age (n = 7, k = 7, B = −0.000, 95% CI [−0.000; −0.000], p = 0.002).

Emotion regulation: the association between sexual abuse and emotion regulation decreased with study quality (n = 33, k = 33, B = −0.034, 95% CI [−0.063; 0.005], p = 0.021). The association between emotional neglect and emotion regulation increased with age (n = 20, k = 20, B = 0.014, 95% CI [0.005; −0.022], p = 0.002) and sample size (n = 20, k = 20, B = −0.000, 95% CI [−0.000; −0.000], p = 0.003). The association between physical neglect and emotion regulation increased with age (n = 6, k = 6, B = 0.010, 95% CI [0.000; −0.095], p = 0.040).

No moderation effects of mean age, percentage of males, sample size, or study quality were found for the associations between overall or any subtype of CM and self-esteem, self-efficacy, or well-being. For a detailed description of meta-regression results see SF2 in the Supplement.

Subgroup analyses

Subgroup analyses were conducted by overall CM and subtypes. The following categorical variables were explored: (1) western versus non-western countries; (2) clinical versus non-clinical samples.

Global/trait resilience

No differences were found for the associations between overall or any subtype of CM and global/trait resilience in western versus non-western countries, or in clinical versus non-clinical samples.

Resilience domains

The association between emotional abuse and emotion regulation was stronger in western (n = 21, r = −0.321, [−0.364; −0.277]) versus non-western countries (n = 16, r = −0.215, [−0.282; −0.1545), p = 0.010 (see Figure a in the Supplement). The association between emotional abuse and self-esteem was weaker in western (n = 9, r = −0.213, [−0.321; −0.098]) versus non-western countries (n = 15, r = −0.352, [−0.407; −0.296]), p = 0.025 (see Figure b in the Supplement).

No differences were found for the associations between overall or any subtype of CM and any resilience domains in clinical versus non-clinical samples. For a detailed description of subgroup analyses results see SF3 (Figures a, b) in the Supplement.

Sensitivity analysis

To further assess possible causes of heterogeneity and the robustness of findings, a one-study-removed sensitivity analysis (Borenstein, Reference Borenstein2022a) was conducted. Removal of single effect sizes did not change the patterns of results with a few exceptions (see SF4 in the Supplement).

Publication bias

The visual inspection of the funnel plots (see SF5 in the Supplement) and Egger’s test suggested publication bias for the associations between overall CM and self-esteem (z = −0.375, p = 0.005), and between emotional neglect and emotion regulation (z = −0.214, p = 0.036). The trim-and-fill corrected random-effect estimate changed relative to the uncorrected estimate, yet both associations remained significant (see Table 2).

Narrative synthesis of moderators and mediators reported in the included studies

Three (Arslan & Genç, Reference Arslan and Genç2022; Shen & Soloski, Reference Shen and Soloski2024; Somers, Ibrahim, & Luecken, Reference Somers, Ibrahim and Luecken2017) of the 203 reviewed studies investigated effect moderation, and 17 studies investigated effect mediation between CM and resilience outcomes.

Moderators

One study found that heart rate reactivity moderated the effects of CM on depressive symptoms and positive affect (well-being) in young adults (Somers et al., Reference Somers, Ibrahim and Luecken2017).

Another study in college students found that positive perception moderated the adverse impact of emotional maltreatment on emotional but not social well-being (Arslan & Genç, Reference Arslan and Genç2022).

Childhood attachment significantly predicted adult attachment, psychological distress, and self-esteem in adulthood and moderated the relation between child sexual abuse and anxious adult attachment. In addition, secure attachment at least partially protected against a negative long-term effects of child sexual abuse and fostered intra- and interpersonal adjustment in survivors (Shen & Soloski, Reference Shen and Soloski2024).

Mediators

Two studies found that intrapersonal strength (Kapoor et al., Reference Kapoor, Domingue, Watson-Singleton, Are, Elmore, Crooks, Madden, Mack, Peifer and Kaslow2018) and perceived burdensomeness (Allbaugh et al., Reference Allbaugh, Florez, Render Turmaud, Quyyum, Dunn, Kim and Kaslow2017) mediated the relationship between CM and suicide resilience, especially in African American females. Another study found that resilience and coping strategies mediated the association between childhood abuse and PTSD severity and that lower resilience and dysfunctional coping strategies may accentuate the detrimental effects of childhood abuse on PTSD (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Hong, Kim, Song, Lee, Joo, Kim and Yoon2021).

A study found that negative religious coping related positively to all forms of CM other than emotional neglect, while positive religious coping related negatively only to child physical neglect. Furthermore, PTSD symptoms acted as a mediator between abuse and negative religious coping among low-income, African American women with a history of intimate partner violence and suicidal behaviours (Bradley, Schwartz, & Kaslow, Reference Bradley, Schwartz and Kaslow2005).

Two studies found that parental and peer relationship quality mediated the relationship between dual violence exposure to interparental violence and child physical maltreatment and self-esteem in young adulthood (Shen, Reference Shen2009), while authenticity in close relationships partially mediated the relation between emotional maltreatment and negative self-esteem in college women (Theran & Han, Reference Theran and Han2013).

In a cross-national investigation, perceived negative (but not positive) impact of bullying mediated the relationship between adolescent bullying and self-esteem. In addition, perceived negative impact of adolescent bullying victimisation partially mediated, while perceived negative impact of adolescent bullying victimisation fully mediated the relationship between bullying and life satisfaction (Pabian, Dehue, Völlink, & Vandebosch, Reference Pabian, Dehue, Völlink and Vandebosch2022).

One study found that disorganised attachment, including fear, distrust, and suspicion of attachment figures, as well as odd and disoriented behaviours, mediated the relationship between CM and difficulties in emotion dysregulation above what is captured by anxious and avoidant attachment in emerging adulthood in the context of emerging adult romantic relationships (Whittington, Reference Whittington2024).

In a serial mediation model, one study found that anxiety and emotional dysregulation mediated the effect of childhood emotional abuse on pain resilience among individuals with alcohol use disorder (Zaorska et al., Reference Zaorska, Kopera, Trucco, Suszek, Kobyliński and Jakubczyk2020).

Self-concept was shown to mediate the relationship between specific forms of CM and abstinence motivation, and self-concept mediated the relationship between CM and abstinence motivation, as well as self-efficacy among drug addicts (Lu, Wen, Deng, & Tang, Reference Lu, Wen, Deng and Tang2017).

Self-compassion mediated and mitigated the association between CM severity and later emotion regulation difficulties in individuals with substance use (Vettese, Dyer, Li, & Wekerle, Reference Vettese, Dyer, Li and Wekerle2011). Another study concluded that self-compassion, while not a full mediator between CM and psychological well-being, served as a partial mediator for male survivors of CM (Tarber et al., Reference Tarber, Cohn, Casazza, Hastings and Steele2016). In contrast, researchers using serial mediation analysis found that self-critical rumination was a partial mediator, and self-compassion was not a mediator in the relationship between child emotional maltreatment, and self-satisfaction and well-being (Cecen & Gümüş, Reference Cecen and Gümüş2024).

Another study found that emotional maltreatment was negatively associated with life satisfaction through self-esteem and through the pathway from self-esteem to self-compassion, suggesting that self-processes are more vulnerable to emotional maltreatment than to other maltreatment types in emerging adulthood (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Cao, Lin, Zhou and Chi2022).

In a chain mediation model, positive affect, negative affect, and emotional intelligence mediated the link between CM and life satisfaction. In addition, CM influenced life satisfaction through the sequential intermediary of ‘emotional intelligence-positive affect’ and ‘emotional intelligence-negative affect’ (Xiang, Yuan, & Zhao, Reference Xiang, Yuan and Zhao2021). Another study, using a two-step structural equation modelling approach, found an association between childhood psychological maltreatment and spiritual well-being, and that this relationship is mediated by both intolerance of uncertainty and emotion regulation in a Turkish sample (Yilmaz & Satici, Reference Yilmaz and Satici2024).

Finally, in a prospective cohort study, although adolescent bullying was a significant risk factor for the onset of depression and poor well-being in adulthood, no mediating or moderating effects of depression were found on the relationship between bullying and well-being (Armitage et al., Reference Armitage, Wang, Davis, Bowes and Haworth2021).

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis investigated associations between overall and different subtypes of CM, global/trait resilience, and domains of resilience in adults. Across the identified studies, we confirmed overall CM was associated with resilience in adulthood. Specifically, overall CM was associated with poorer global/trait resilience, coping, self-esteem, emotion regulation, self-efficacy, and well-being. We also found associations between different CM subtypes and impairment in both global/trait resilience and most resilience domains. However, overall associations were small in magnitude, and findings differed depending on the subtype of CM and resilience domain considered, suggesting differential and specific effects.

Given the vast evidence that CM increases the likelihood of developing physical and mental health problems (Baldwin et al., Reference Baldwin, Wang, Karwatowska, Schoeler, Tsaligopoulou, Munafò and Pingault2023; Mehta et al., Reference Mehta, Kelly, Laurens, Haslam, Williams, Walsh, Baker, Carter, Khawaja, Zelenko and Mathews2023) and that resilience deficits are a core component of adaptive functioning (Barton et al., Reference Barton, Ehring, Reinhard, Goerigk, Wüstenberg, Musil, Amann, Jobst, Dewald-Kaufmann and Padberg2023), it is possible that a larger effect is being constrained by methodological limitations in the literature. It should also be considered that some of the significant results found in this review may be affected by confounding variables not addressed by most of the included studies (e.g. education level, intelligence, socioeconomic status) and that there could be other, non-causal explanations, such as poverty that may increase risk of CM exposure and impairment in resilience outcomes. Future prospective studies should examine whether a bidirectional relationship between CM and resilient functioning exists.

The associations with CM found in this meta-analysis were weak, suggesting that impairments in resilience in adults are likely influenced by additional biological factors, such as brain structure and functions (Fares-Otero, Verdolini et al., Reference Fares-Otero, Verdolini, Melero, Andrés-Camazón, Vilajosana, Cavone, García-Bueno, Rapado-Castro, Izquierdo, Martín-Hernández, Mola Cárdenes, Leal, Dompablo, Ortiz-Tallo, Martinez-Gras, Muñoz-Sanjose, de Lapuerta, Rodriguez-Jimenez, Díaz Marsá and Radua2024). Future research should explore how the timing of CM (Fares-Otero & Schalinski, Reference Fares-Otero and Schalinski2024), especially during sensitive neurodevelopmental periods affects resilience, and preferably employ multimodal approaches, including neuroimaging and clinical assessments (Demers et al., Reference Demers, Hunt, Cicchetti, Cohen-Gilbert, Rogosch, Toth and Thomas2022; Fares-Otero, Halligan, Vieta, & Heilbronner, Reference Fares-Otero, Halligan, Vieta and Heilbronner2024) to capture the role of neurobiological factors (Ioannidis, Askelund, Kievit, & van Harmelen, Reference Ioannidis, Askelund, Kievit and van Harmelen2020; Zhang, Rakesh, Cropley, & Whittle, Reference Zhang, Rakesh, Cropley and Whittle2023) and psychosocial influences, such as cognitive reserve (Fares-Otero Borràs et al., Reference Fares-Otero, Borràs, Solé, Torrent, Garriga, Serra-Navarro, Forte, Montejo, Salgado-Pineda, Montoro, Sánchez-Gistau, Pomarol-Clotet, Ramos-Quiroga, Tortorella, Menculini, Grande, Garcia-Rizo, Martinez-Aran, Bernardo and Verdolini2024). Despite the relevance of CM in health (Lawrence et al., Reference Lawrence, Hunt, Mathews, Haslam, Malacova, Dunne, Erskine, Higgins, Finkelhor, Pacella, Meinck, Thomas and Scott2023; Telfar et al., Reference Telfar, McLeod, Dhakal, Henderson, Tanveer, Broad, Woolhouse, Macfarlane and Boden2023), studies examining its effects on resilience outcomes are limited, particularly in those with mental and physical conditions. Further research on the role of CM exposure, especially neglect, on resilience outcomes, including coping abilities, and in larger male samples (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Masters, Casey, Kajumulo, Norris and George2018; Fares-Otero et al., Reference Fares-Otero, Schäfer, Vieta, Seedat and Halligan2025), is crucial to inform interventions and improve outcomes in adulthood. See also Table 3 for a summary of methodological issues and further recommendations for future studies.

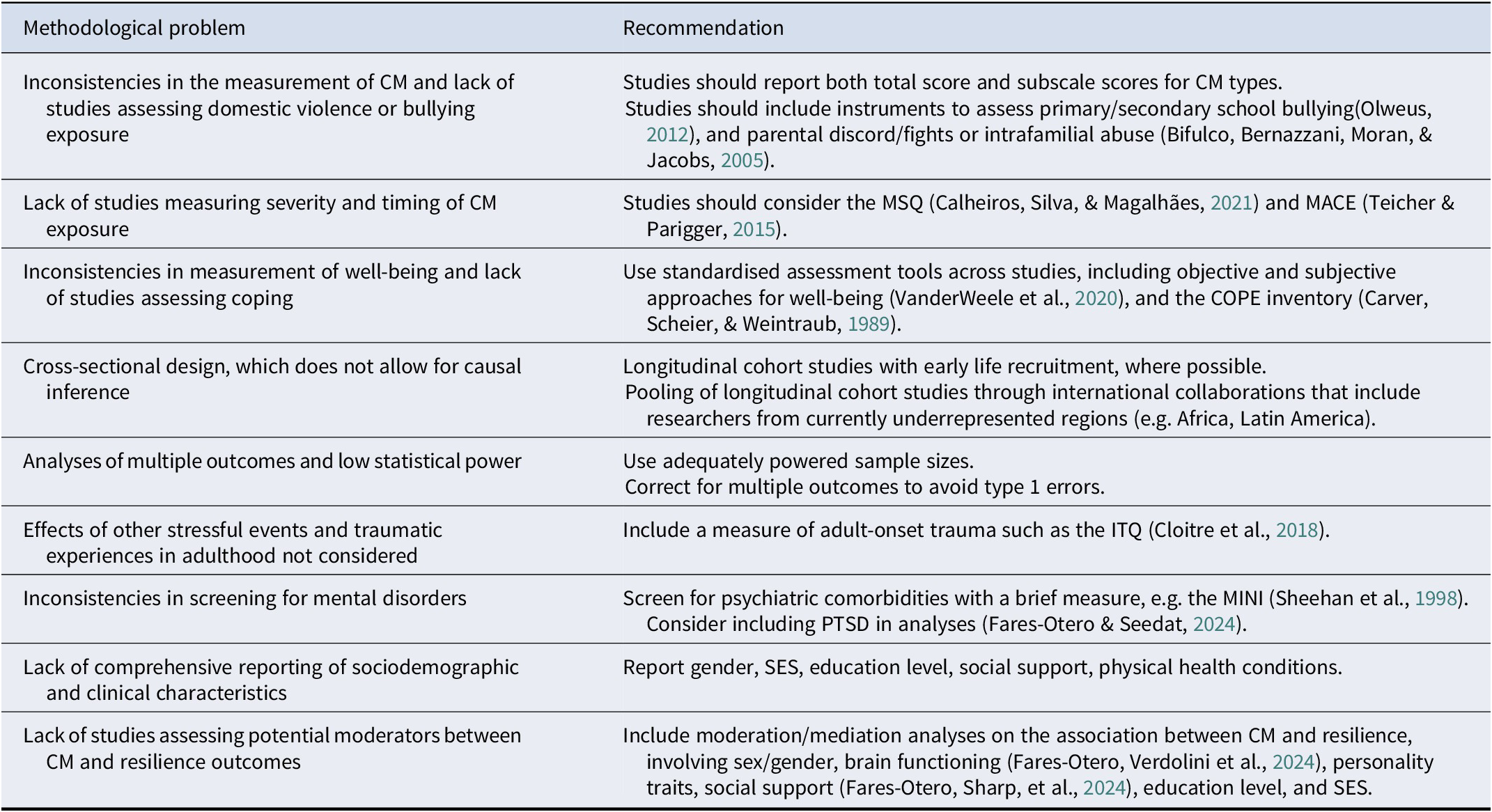

Table 3. Methodological problems identified in the included studies and recommendations for future research

Abbreviations: CM, Childhood Maltreatment; COPE, Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced; ITQ, International Trauma Questionnaire; MACE, Maltreatment and Abuse Chronology of Exposure; MINI, Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview; MSQ, Child Maltreatment Severity Questionnaire; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; SES, Socioeconomic status.

Interestingly, the emotional types of CM showed the strongest associations with impaired resilience. This is in line with previous meta-analysis on CM and social functioning (Fares-Otero De Prisco et al., Reference Fares-Otero, De Prisco, Oliva, Radua, Halligan, Vieta and Martinez-Aran2023) and a substantial body of evidence demonstrating that emotional maltreatment may be more strongly associated with high levels of affective instability (Palmier-Claus et al., Reference Palmier-Claus, Golby, Stokes, Saville, Velemis, Varese, Marwaha, Tyler and Taylor2025) and depressive symptoms (Hutson et al., Reference Hutson, Dan, Brown, Esfand, Ruberto, Johns, Null, Ohashi, Khan and Du2024), factors that may mediate the relationship between CM and resilience outcomes. Taken together, our findings indicate that emotional abuse and emotional neglect represent an important potential (early) intervention target for adults.

Clinical implications

Clinically, our findings of poorer resilience in people with CM histories align with and inform a growing body of research suggesting that CM should be routinely considered during assessment, diagnosis, and treatment. Assessing CM and resilience systematically in clinical and community settings could support early intervention, mitigate detrimental effects on resilience, and may even contribute to more accurate diagnoses. While some institutions already include CM in standard assessments, broader adoption of this practice across mental health settings would strengthen preventive and supportive care, particularly by addressing impairment in CM-related resilience early in the illness.

Our findings suggest that early interventions promoting resilience, such as trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapy-based resilience training (Zalta et al., Reference Zalta, Tirone, Siedjak, Boley, Vechiu, Pollack and Hobfoll2016), therapeutic processes that encourage social ties and therapeutic alliance (Burton, Cooper, Feeny, & Zoellner, Reference Burton, Cooper, Feeny and Zoellner2015; Snijders et al., Reference Snijders, Pries, Sgammeglia, Al Jowf, Youssef, de Nijs, Guloksuz and Rutten2018), and psychotherapy founded on the Trauma Resiliency Model (Grabbe & Miller-Karas, Reference Grabbe and Miller-Karas2018) might be useful in helping adults with CM experience by focusing on maintaining global and functional health. Moreover, psychotherapeutic approaches should target self-compassion and self-concept, secure attachment, emotional intelligence, PTSD and mood symptoms, and advance training to help individuals to cope with life stressors that may be preventing them from achieving or maintaining recovery.

Strengths and limitations

This study builds on the well-established evidence base for the role of CM as a risk factor for adverse health and psychosocial outcomes and reinforces that experiences of CM could be related to impaired resilience in survivors. We performed a comprehensive and up-to-date systematic review, allowing the inclusion of a large number of studies. This is by far the first meta-analysis in the field of CM and resilience with a multi-domain approach. This study also benefitted from the wide range of pooled subjects, which constitutes a geographically diverse sample. Although there was some variability in which subtypes of CM were reported, most studies used the same standard and validated instrument to assess CM (CTQ). Other strengths of this study include the rigorous methodology of the systematic search, study selection, and data extraction performed by independent researchers.

Our work also includes some limitations. First, the number of studies available for some meta-analysis was small, meaning that analyses may not have been sufficiently powered for detecting small effects (Jackson & Turner, Reference Jackson and Turner2017). The capacity to identify heterogeneity and moderators was also substantially limited, and extra caution is needed for conclusions in meta-regressions when there are <10 studies. Second, it was impossible to account for all the possible variations across populations with different social environments, health conditions, and diagnoses, as well as variations across measurement instruments utilised (and conditions of administration) in the included studies, although most assessed resilience outcomes with robust tools. A sensitivity analysis confirmed that omitting one study at a time did not change the overall findings. Third, CM was retrospectively reported through assessments that may be biased, though retrospective self-reports of CM have shown sufficient reliability (Badenes-Ribera, Georgieva, Tomás, & Navarro-Pérez, Reference Badenes-Ribera, Georgieva, Tomás and Navarro-Pérez2024). Finally, we did not include unpublished work. However, the inclusion of data from unpublished studies could also introduce bias (Boutron et al., Reference Boutron, Page, Higgins, Altman, Lundh and Hróbjartsson2023).

Conclusions

In conclusion, overall CM and its subtypes are linked to lower global/trait resilience and more resilience impairments across several domains, particularly coping, self-esteem, emotion regulation, self-efficacy, and well-being in adulthood. While the associations are weak, exploring socioeconomic status, education level, and the timing and severity of CM, as well as moderators such as attachment, mood symptoms, and personality features, may clarify these relationships. This knowledge may reduce the burden associated with negative health and psychosocial consequences in adulthood and increase the likelihood that maltreated individuals receive appropriate and/or optimal treatment.

Prospective and interventional studies are needed to address the limitations of the current evidence, which mainly comprises cross-sectional studies with retrospective reporting of CM. Our findings nonetheless support CM as a key predictor of resilient functioning in adulthood, underscoring the potential value of trauma-informed interventions and approaches founded on trauma resiliency models. Also, early interventions for at-risk children and adolescents may help improve resilience and quality of life outcomes long-term, including those with mental disorders.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291725001205.

Data availability statement

NEF-O has full access to all data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analyses. The data that support the findings of this study and/or codes are available on request.

Acknowledgements

We thank Jose Manuel Estrada Lorenzo for his assistance in the search strategies design, literature searches, and full-text retrieval. We also thank Jiaqing O, Carolina Gonzalez, Görkem Ayas, and Tilahun Belete Mossie for their help with a preliminary screening, and the Global Collaboration on Traumatic Stress.

Author contributions

Protocol registration, Term: NEF-O. Data collection and curation: NEF-O, JCN, JSW, AS, IS, GS. Writing – original draft: NEF-O, SS. Writing – reviewing and editing: NEF-O, JCN, JSW, GS, SS. Methodology, Formal analysis, Validation, Visualisation: NEF-O. Investigation: NEF-O, JCN, JSW, AS, GS. Resources, Funding acquisition: NEF-O, IS, EV. Supervision: NEF-O, EV, SS. All authors revised and approved the final version of the submitted manuscript.

Funding statement

This study was supported in part by DAAD (ID-57681229 – Ref. No. 91629413). The funder had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. This article was published Open Access thanks to the transformative agreement between the University of Barcelona and Cambridge University Press.

Competing interests

EV has received grants and served as a consultant, advisor, or CME speaker for the following entities: AB-Biotics, AbbVie, Angelini, Biogen, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Celon Pharma, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Ferrer, Gedeon Richter, GH Research, Glaxo-Smith Kline, Janssen, Lundbeck, Novartis, Orion Corporation, Organon, Otsuka, Sage, Sanofi-Aventis, Sunovion, Takeda, and Viatris, outside the submitted work. SS has received educational grants and travel support from Lundbeck, Cipla, and Sanofi-Aventis outside of the submitted work. The other authors report no financial relationships with commercial interests.