In the nineteenth century, when few women gave birth under formal medical care, many factors made infanticide the most frequently committed form of homicide and the least likely to be detected. The 1892 Criminal Code provided statutory alternatives to tackle low rates of conviction for murder. On indictment for murder, a guilty verdict for the noncapital offence of concealment of birth could follow a jury’s decision that evidence showed that the accused had secretly disposed of her infant’s dead body.Footnote 1 Although the Code set a maximum term of imprisonment of two years for concealment, it also included the offence of neglect, punishable by up to a life term, if that act caused permanent injury or death to the infant.Footnote 2 This compilation of possible charges framed the prosecution and punishment of infanticide in Canada until 1948, at which point legislators introduced a new category of culpable homicide that was not punishable by death: infanticide.

Explanations of the timing and nature of the statutory invention of infanticide have thus far followed two lines of argument. The first arose through early feminist analysis of the governance of female offenders. It defines patriarchal and psychiatric rationalizations of women’s biological and psychological disorders as the source of gendered legislation on infanticide in the twentieth century—the age of “the expert.”Footnote 3 Canada’s 1948 statute appears to fit this model, as it used a gender-specific definition of mothers’ diminished responsibility and referred to the capacity of childbirth to induce an “unbalanced mind.”Footnote 4 Yet, as Kramar asserts, this psychological terminology simply glossed over what amounted to a pragmatic response to prosecutors’ inability to convict neonaticidal mothers of murder or manslaughter. This second line of argument attributes the nature of the infanticide statute to a “sociological or cultural understanding” of accused women’s circumstances, not a psychiatric one.Footnote 5 Furthermore, the new statute sought to replace jurors’ sympathy with a noncapital offence that carried a penalty that was well short of life imprisonment.Footnote 6 Yet, this interpretation falls short of explaining the appearance of Canada’s statute in 1948 and it overlooks its connection to emergent doubts over the capacity of the death penalty to deter homicide.

By placing the invention of infanticide in the Criminal Code in the framework of the history of the death penalty, this paper illuminates a neglected nexus in Canada’s sociolegal history. The 1940s was not an intense period of abolitionism but it was a pivotal decade in the modernization of the criminal law in Canada—a campaign that was led by the Canadian Bar Association (CBA).Footnote 7 Several months after the federal government invented the infanticide statute, it appointed a Royal Commission on the Revision of the Criminal Code that began to redraft the criminal law in 1949—the same year as the British Parliament authorized a Royal Commission on the death penalty. Although the revised code removed the death penalty for rape, it did not recommend abolition; nevertheless, the commissioners advised the government to consider further possible amendments to the law governing capital punishment.Footnote 8 These legal and political changes occurred in the wake of two controversial trials of women who were convicted of killing their infants. The cases—Annie Rubletz’s in 1940 and Evelyn Dick’s in 1947—sharpened the legal profession’s and legislators’ concerns over the lack of uniformity in the prosecution and punishment of infanticide but they also opened up debates about the justifiability of the death penalty across the board.

Beginning with earlier moves to restrict capital punishment in Canada, this paper considers the factors that led England to define infanticide as a noncapital offence in the 1920s and 1930s.Footnote 9 Canadian law reformers and politicians drew on and departed from British law in the postwar period, as evidenced in parliamentary debates, professional journals and commissions. Although the government attempted effectively to replace jurors’ sentiments with a legislated means of mitigation, the passage of the 1948 infanticide statute was the first of several amendments to the Criminal Code that limited the reach of the mandatory penalty of death in modern Canada.

Precedents for paring capital punishment

Amendments to the law of homicide were infrequent and any bill to restrict capital punishment to a specific subset of offenders, offences and victims could face stiff headwinds. However, 1948 was not the first time in Canadian history that politicians proposed a gender-specific law that removed the mandatory penalty of death. After the amalgamation of the criminal law in 1869, the punishment of rape (the unlawful act of a man upon a woman who is not his wife without her consent) was modified from the mandatory penalty of death to life imprisonment or capital punishment, at the discretion of the judge. Four years later, the government removed the death penalty for attempted murder in addition to the offence of carnal knowledge (sexual contact with a girl under the age of ten).Footnote 10 The 1877 amendment that set a minimum penalty of five years and a maximum of life imprisonment for the sexual abuse of girls dissatisfied retentionists, who thought the offence deserved the same punishment as rape. Opponents wanted to allow judges the option to sentence offenders to death. However, the Secretary of State, who presented the bill, justified the amendment as a rationalizing move: first, it followed the enlightened principle that, “unless death ensues,” no offence against the person should be punishable by death; second, it would deter jury nullification by bringing “the law into conformity with public opinion and the practice of the country.”Footnote 11 Despite three days of retentionist resistance to removing carnal knowledge from Canada’s capital crimes, the government prevailed. It narrowed the scope for discretion—both jurors’ and judges’—over the punishment of a crime by male offenders against age- and gender-specified victims and it further restricted the reach of capital punishment in Canadian criminal law.

Britain’s infanticide laws of 1922 and 1938

Until 1948, no further amendments modified the scope of the death penalty in Canada but, in the UK Parliament, that change occurred earlier in the twentieth century. In England, no woman was executed for the murder of her infant after 1849, despite the subsequent prosecution of scores of women for this form of homicide.Footnote 12 Most mothers were either prosecuted for or found guilty of concealment of birth—an offence that carried a maximum of two years’ imprisonment, and this verdict could be made upon a finding of not guilty of murder or manslaughter.Footnote 13 In the hearings that were conducted by the Royal Commission on Capital Punishment (1864–66), a cleric and essayist was asked whether he thought that infanticide should be punishable by death: “Can it really now be said that it is so? In nine cases out of ten, trying women for their lives for infanticide is a cruel farce.”Footnote 14 Although the commission’s Final Report in 1866 recommended a maximum penalty of fifteen years of imprisonment for causing the death of a newborn by unlawful means, the government of the day rejected it.Footnote 15 Women who were convicted of murdering their infants remained, like those who killed adults or older children, subject to the penalty of death.

Over the next half-century, subsequent bills proposed to make infanticide a noncapital offence but each failed, until 1922. Many analysts attribute England’s passage of the Infanticide Act to growing skepticism over women’s culpability, combined with the mounting readiness of legislators to accept psychiatric accounts of postpartum mental disturbances, short of insanity, to incorporate a concept of diminished responsibility into the law.Footnote 16 The result was a new substantive offence with a partial defence to murder: women who were found not guilty of murder could be sentenced as if convicted of manslaughter, so long as they were found not to have fully recovered from giving birth. However, two other factors provide a more compelling explanation for the timing of the Act. The first was British women’s activism that followed the enfranchisement bill, the appointment of the first female magistrates and the entry of women into the legal profession, all of which occurred in the lead-up to the Act.Footnote 17 Suffragists and networks of women who were engaged in penal reform used new tools to shape public policy and their leaders had the ears of government ministers. These activists became difficult to ignore in 1921 when a young factory worker was sentenced to death in Leicester for the murder of her infant. The politicization of her case through the popular press was the second factor in spurring parliament to legislate an alternative to the death penalty for murder.Footnote 18

Outrage over the conviction of Edith Mary Roberts for the murder of her newborn generated the legislative momentum that earlier infanticide bills lacked. Prominent women, including the member of the Leicester Board of Guardians, organized monster petitions, while many others wrote letters to the editor, the Home Secretary, the attorney general and Queen Mary.Footnote 19 Despite the passage in 1919 of the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act, which had opened up jury service to women in England, petitioners protested that an all-male jury had found Roberts guilty because the judge had allowed the defence to disqualify women from the jury pool. The Home Office quickly commuted Roberts’s sentence to penal servitude for life, but her supporters kept stoking political heat to reduce it further. Female penal reformers and their male allies in the press and Parliament demanded the law be changed to prevent any other such mother from being convicted of murder. This is what Roberts’s defence lawyer had tried to do when he claimed that “whatever the girl did was done in a frenzy of agony and pain. She was probably hardly conscious of her acts at the time, and was consequently not responsible.”Footnote 20 This was not the terminology of a psychiatric expert, but a commonsense plea for sympathy that the barrister hoped his fellow men of the jury might feel.Footnote 21 Rather than relying on persuasive defence lawyers and receptive jurors, male or female, the Infanticide Act (1922) incorporated the notion of diminished responsibility and substituted life imprisonment as the maximum sentence, abolishing the death penalty for women like Roberts—distressed and unbalanced through the trauma of birth.Footnote 22

Although prosecutions for infanticide proceeded immediately in England, defects in the wording of the Act left uncertainty over the evidentiary threshold for the disturbance of the accused’s state of mind and the degree of mens rea involved in her causing the infant’s death. Disputes over the meaning of “newly born” to describe the victim also caused confusion and surfaced in appeals to the Court of Criminal Appeal. By the 1930s, feminist agitation for a revised law had dissipated but jurists’ calls for an amendment became a greater factor and this gained support in the House of Lords.Footnote 23 The amended Act of 1938 defined the offence as “any wilful act or omission” of a mother that caused the death of a child under one year of age while “the balance of her mind was disturbed by reason of her not having fully recovered from the effect of giving birth to the child or by reason of the effect of lactation.”Footnote 24 Although the amended Act retained the maximum punishment of life imprisonment (at the discretion of the judge), it extended the age limit and opened up the factor of lactation to the “effect” of childbirth, effectively encompassing a greater range of women. In Britain, no further move to consider any form of diminished responsibility to preserve persons who committed culpable homicides from the death penalty occurred until 1957, when the Homicide Act introduced the concept of diminished responsibility.Footnote 25 Canada never made that move, but it did begin to trim the scope of the death penalty in 1948, when it introduced its own infanticide statute.Footnote 26

The Canadian invention of infanticide

No legislative precedent in one jurisdiction leads directly to legislation in another and this was the case with Britain’s and Canada’s infanticide statutes.Footnote 27 First, a decade elapsed between the 1938 English law and Canada’s amendment to the Criminal Code; second, the statute differed significantly from England’s revised Infanticide Act. Furthermore, the processes that led to it and the penal politics that shaped the move against the death penalty for infanticide were distinct. As in England, a controversial capital conviction—Annie Rubletz’s in 1940—for infanticide triggered demands for a noncapital infanticide offence, as had happened in England in 1921. Yet, in Canada, the legal profession and criminal law reformers led the charge, not women’s groups or newspaper campaigns. Canada’s lawmakers also introduced a substantially lower maximum penalty for infanticide in 1948, while they ensured the death penalty could still apply if a woman who was not of unbalanced mind was intent on murder. The 1947 trial of Evelyn Dick for the murder of her infant son was a potent reminder that removing the death penalty as punishment for infanticide was applicable only to accused women whose desperate acts appeared to spring from shame and physical trauma, not the cold-hearted decision to kill their infants.

In many respects, the trial of Annie Rubletz in 1940 for the murder of her infant daughter in a Saskatchewan farmhouse followed the familiar narrative of a young, unwed mother who was overwhelmed by anxiety over the birth of an illegitimate child after giving birth unaided. Like Roberts in Leicester in 1921, Rubletz was found to have deliberately suffocated the newborn and forensic tests that were conducted on the remains determined that the infant had breathed after birth. In both trials, the jury heard the Crown argue that the accused had committed wilful murder—an offence that carried the mandatory penalty of death. When the judge in Rubletz’s trial charged the jury, he urged them to focus on the accused’s confession to police, not any sympathy that they might feel for the girl. Because Canada, unlike England, excluded women from jury service, the judge warned his fellow men to resist their impulse toward chivalry.Footnote 28 Acting on this advice, the jury found the girl guilty of murder but they strongly recommended mercy. While Rubletz’s lawyer prepared an appeal against the conviction (successfully, it transpired), the attorney general of Saskatchewan, Alex Blackwood, set out to politicize the case. Using the authority of his position, he urged the federal Department of Justice to introduce a new, noncapital offence of infanticide to ensure that no other desperate mother would face execution.

The issue that the Saskatchewan case demonstrated was not the problem of jury nullification—a complaint that appeared repeatedly in debates over the English Infanticide Act. Rather, the attorney general capitalized on Rubletz’s conviction by condemning the unpredictability, and therefore the uanjustifiability, of the death penalty for infanticide. In Rubletz’s case, the Saskatchewan Court of Appeal set aside the conviction on the basis of “the erroneous manner in which the value of the confession as evidence and the means of testing its truth were dealt with during the trial and left to the jury.” In fact, the jury had requested clearer instruction on the law. Two hours into their deliberations, the foreman asked: must they consider the accused’s statement voluntary? Was it possible for the jury to reduce the charge? The judge shut down that possibility. In his trial report to the Department of Justice’s Remissions Branch, required after capital trials that ended in convictions, the judge disclosed that he had feared “the jury was very loath to find the accused guilty.” For that reason, he decided not to charge them on concealment of birth.Footnote 29 Retried for murder early in 1941, Rubletz opted to plead guilty to concealment and the prosecution accepted the plea, which left the young woman who had spent months in the shadow of execution to serve two years in jail for her part in the infant’s death. Despite this outcome, the province’s attorney general remained committed to his conviction that Canada must “lighten the penalty for infanticide in keeping with the British law.”Footnote 30 However, Blackwood’s reform floundered until the CBA incorporated it into its broader campaign to modernize the nation’s criminal law in the mid-1940s.Footnote 31

In 1940, the ground for law reform was barren in Canada but it became more fertile after the war, not because of lobbying by medical or psychiatric experts, but as part of a wider endeavour to update Canada’s Criminal Code. Rationalizing penalties in line with criminal justice practice was a critical component in that effort. At the beginning of the decade, there was little momentum in favour of inventing an infanticide statute precisely because jurors and judges exercised discretion in response to the circumstances that surrounded individual cases. Asked to comment on his Saskatchewan counterpart’s call for a noncapital infanticide law, Ontario’s attorney general rejected it. In his professional opinion, the law as it stood “works out fairly well, and judges and juries apply it humanely,” he believed, and he backed that up by reference to the five most recent infanticide cases in his province to justify his opinion. In each case, the woman had been charged with murder but convicted of the lesser count of concealment. “That is how the court meets the exigencies of such cases.”Footnote 32 Deterrence was a more important reason to leave infanticide as punishable by death, according to the editor of the Windsor Star. Just because England had brought a “‘mercy law’ into vogue,” that did not make it desirable for Canada to follow, he warned. This move against the death penalty was also morally repugnant: “What is now suggested is the abolition of capital punishment entirely in cases of infant slaying.” Considering that infanticide was a “particularly revolting form of murder,” there was no cause to remove it from “the category of capital offences.”Footnote 33

By the mid-1940s, the CBA had begun to build a platform on which calls for an infanticide statute could be made with greater authority. The professional organization took on a formal role to advise the government on criminal legal matters and penal policy, and its overarching objective was to develop uniformity in criminal law and procedure throughout the country. At the same time, uniformity in the administration of justice was an allied objective. In 1943, the CBA set up a Criminal Law Section at its national conference and it held the first Conference of Commissioners on Uniformity of Legislation in Canada one year later.Footnote 34 Provincial chairmen were asked to identify what they considered “important matters of revision and improvement,” and Blackwood, serving as Saskatchewan’s chairman, proposed “revision of the various penalty sections of the Code with a view to removing inconsistencies and obtaining uniformity.”Footnote 35 Had Annie Rubletz been tried by a judge who was less intent on preventing the jury from acquitting the accused or finding her guilty of concealment, she would have faced the lighter penalties that were imposed on women who had recently been tried for infanticide in Ontario, and not execution. The CBA referred possible amendments to the Criminal Code to “deal with cases of infanticide analogous to The Infanticide Act of England” to Blackwood and he set to work.Footnote 36 Over the following few years, the federal government grew receptive to the CBA’s objectives and its commitment to reform the Criminal Code in its entirety.

Demands for root-and-branch reform of the criminal law had been a refrain in legal circles for two decades before Louis St-Laurent’s Liberals responded. The original code came into force in 1893 and 1927 was the last year in which a major revision to Canada’s statutes had taken place. Since then, Canada’s national character had altered significantly and modernization of the Criminal Code was overdue. The officials who were assigned the mammoth task of drafting it admitted that the existing compendium of criminal laws was “deprecated for its inconsistencies, ridiculed for its archaisms, disparaged for its verbosities and derided for its ambiguities.”Footnote 37 However, there were several “troublesome parts” of the Code that legislators, informed by the CBA, addressed prior to the prodigious undertaking that led to the adoption of a revised code and infanticide was one of them.Footnote 38 Indeed, the minister of justice chose the debate over the infanticide bill as the occasion on which to announce the government’s plan to take the reins from the CBA and to steer the country toward a full revision of the Criminal Code to make it fit for purpose in postwar Canada.

The abolition of the death penalty for infanticide

According to James Lorimer Ilsley, the minister of justice, the impetus behind Bill 337—to amend the Criminal Code by inventing a new category of culpable homicide—was to solve the problem that Rubletz’s trial judge had tried to prevent: jurors’ reluctance to find women guilty of murder or manslaughter for killing their infants. However, the Conservative member for Calgary West, Arthur Smith, was mystified by the government’s bill. What was the reason for it? “Have we been allowing parents guilty of infanticide to go free?” he asked. Was there “some interference here with the law with regard to insanity, or the rules thereto”?Footnote 39 The minister’s explanation was anecdotal:

it is useless to lay a charge of murder against the woman, because invariably juries will not bring in a verdict of guilty. They have sympathy with the mother because of the situation in which she has found herself […] crown prosecutors, and those who lay charges, if they are to obtain convictions, lay charges of concealment of birth […] [however] anyone who looks at the section will see that it is really not concealment of birth, but rather concealment of the body.Footnote 40

Ilsley added that the prosecution of women for homicides of infants was farcical, as jury nullification brought the “law into disrepute.” Sentiment supposedly overwhelmed sense in every trial and he alleged that no woman paid a high price for her crime. However, Rubletz’s murder conviction, rather than an acquittal, was the incident that had initiated efforts at law reform, and thanks to an attorney general, backed by the CBA, a murder conviction for infanticide had also brought the law into disrepute.Footnote 41

For this new category of culpable homicide, the government’s bill calibrated the punishment in relation to the requisite mitigating elements. Like the British Acts, it took death off the table, but it did not replicate the 1922 Act or its 1938 revision. In England and Wales, a woman who was found guilty of infanticide could be “punished as if she had been guilty of the offence of manslaughter of the child.” Penal servitude for life was also the prescribed maximum punishment for manslaughter in Canada, but the minister of justice proposed a far lower penalty—a maximum of three years in prison—for manslaughter. This alternative struck several members as being curious and inadequate. The strongest criticism came from Conservative E. Davie Fulton, who was a Rhodes scholar with a bachelor’s degree in jurisprudence from Oxford.Footnote 42 Early in 1948, the member for Kamloops began to wage war against crime comics that, he claimed, tended to “the lowering of morals” of minors and to induce “the commission of crime.”Footnote 43 Several months later, Fulton applied the same reasoning to the mooted punishment for infanticide. Why did Bill 337 make it “a lesser penalty and thus run the risk of encouraging persons to commit the crime?” he demanded. Awareness that the crime was subject to the death penalty acted as a deterrent at present but, if the punishment were three years in prison, then “those who might be tempted might yield to the temptation to commit the crime.” Like Ontario’s attorney general before him, Fulton argued that discretion was better left in the hands of the judge and jury; however, infanticide—a crime “which is most shocking if committed”—must remain punishable by death.Footnote 44

In the debate over the mitigation of a homicide that was otherwise covered by the Code’s definitions of murder and manslaughter, members queried the distinction between an “unbalanced mind” consequent to giving birth, on the one hand, and the criteria for a finding of not guilty by reason of insanity, on the other. Minister Ilsley clarified that the bill did not rule out a defence of insanity if the evidence supported that finding; rather, the proposed legislation was meant to apply to cases “where there is not the degree of mental derangement amounting to insanity.” The death penalty could justifiably be abolished for homicides of infants, as “a slightly deranged, distressed mother” was unlikely to consider the penalty for doing away with her infant. Yet, the minister of justice’s reference to the incapacity of the death penalty to deter infanticide opened up a Pandora’s box of questions about the defensibility of capital punishment more broadly.

From infanticide to questioning the death penalty

John Diefenbaker, a former criminal defence barrister, capitalized on the debate over the government’s infanticide bill to promote two objectives that he championed: the need for a thoroughly revised Criminal Code and an inquiry to test the notion that deterring homicide hinged on the threat of capital punishment.Footnote 45 As the Conservative MP from Lake Centre, Saskatchewan, first elected in 1940, he would undoubtedly have known about the Rubletz case and he may have had her in mind when he acknowledged “in a great number of cases in which a woman finds herself in the position of having on her hands a newborn child, [she] loses her power of control and the child dies in consequence of some act on her part.” With misgivings over tinkering with the Code rather than overhauling it, Diefenbaker supported the infanticide bill. But, if the Liberal government aimed to make punishment less severe but more certain—a principled sentencing rationale as old as Beccaria —then why stop there? Having represented accused murderers, some of them executed, Diefenbaker was buoyed by the vote in the British House of Commons in April 1948 in favour of a five-year moratorium on the death penalty.Footnote 46 Two weeks before Ilsley introduced the infanticide bill, the House of Lords slammed the door on the House’s support for abolition. Nevertheless, Diefenbaker remained optimistic, as British parliamentarians were working toward a compromise “whereby the death penalty for murder will be imposed only in certain cases; that is, where murder is premeditated or is of a particularly gross nature.” The infanticide bill provided a similar compromise, Diefenbaker observed, by inventing an “offence of homicide short of murder or manslaughter.”Footnote 47 Although he lent his support to Ilsley’s bill, the time was now ripe for the government to make further moves against the death penalty.

The debate over the infanticide bill slid quickly into uncomfortable questions about the death penalty, its administration and its justification. Ilsley tried to deflect them by commenting that capital punishment is “always a favourite topic of debating societies. College debates, inter-class debates, and inter-collegiate debates have taken place on the subject.” Diefenbaker was not the only member who took offence. Stanley Knowles, stalwart of the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation party, stated that there was “more interest by Canadians in the […] possible abolition of capital punishment than the minister realizes.” But Ilsley insisted that there was “little demand” for any change to the law. Convinced that miscarriages of justice had occurred in cases where he had defended accused murderers, including trials in which the jury had recommended mercy, Diefenbaker tried to shine a light on the government’s management of capital cases after conviction: “Where the death penalty is imposed, to what degree is there any investigation subsequently by officers of the Crown relative to the rightness of conclusion of the jury, and as to the advisability or inadvisability of granting a commutation of sentence?”

Placed on the defensive, the minister outlined the procedures that his department’s remissions branch followed and the “exhaustive” reviews that were conducted to consider “whether any circumstances would justify clemency.” Diefenbaker’s experience left him unconvinced. Aware that there was no likelihood that the Liberal government would, like Britain’s Labour government, permit a debate on the death penalty, he floated the prospect of an official study “as to the value of the death sentence in the case of murder.” Supported by Knowles, Diefenbaker challenged the government to conduct an investigation “along that line, dealing with the general problem.”Footnote 48

Despite the minister of justice’s attempt to put a lid on these pesky questions, insisting that no investigation of the sort had been conducted or contemplated, the government was in the midst of considering the justifiability of the death penalty at the very moment of the infanticide debate. In June 1948, one of Ilsley’s duties was his service as chairman of the Special Joint Committee of the Senate and the House of Commons on the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights. One of the prime concerns that emerged from the minister of justice’s point of view was the clash between the draft declaration and the right of signatory states to impose capital punishment. The principle of the right to life and liberty surely had to be limited, Ilsley insisted: everyone had that right “except those whose lives are taken away by process of law.”Footnote 49 Yet, as Ilsley admitted during the course of the infanticide bill debate, the processes that determined whether persons who were sentenced to death were executed were discretionary in nature.

The opponents to the infanticide bill objected to its erosion of the death penalty, which the Liberal minister otherwise upheld as a cornerstone of Canadian penal justice. However, Canada’s appointed senators, unlike the crusty House of Lords, were not prepared to block the noncapital designation of infanticide. Several senators expressed concern about the distinction between “disease of the mind” as a full defence (already in the Code) and the bill’s reference to the accused’s disturbed “balance of mind.” Once assured that accused offenders could be found not guilty by reason of insanity, the Senate approved the bill and no amendments were made.Footnote 50 Within months of this revision of the Criminal Code, the government followed with the appointment of a Royal Commission on the Revision of the Criminal Code, which reviewed the punishments that were prescribed for all criminal offences.

Announced in February 1949, this commission would subject the death penalty to closer scrutiny, as Diefenbaker had first urged during the infanticide bill debate. The announcement followed that of the British government, which appointed a Royal Commission late in 1948 to answer “the question whether there are practical means of limiting the death penalty.”Footnote 51 In Canada, the infanticide amendment had just imposed a limit on the reach of the death penalty; yet, the statute did not restrict prosecutors from charging neonaticidal mothers with murder if they thought there was sufficient evidence of planning and deliberation. In 1948, there was no infanticide case that conveyed that distinction more dramatically than the trial of Evelyn Dick, who was tried in the spring of 1947 for the murder of her infant son.

Immoral moron or murderous mother?

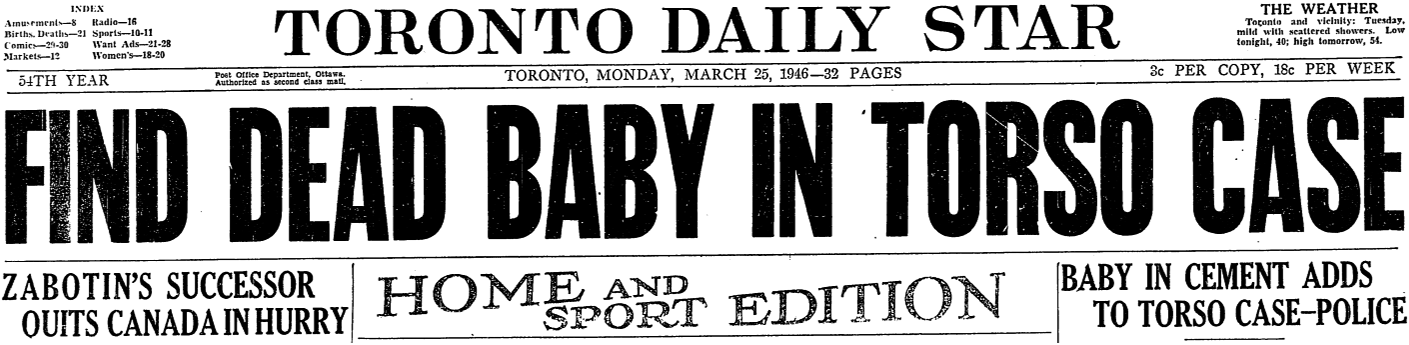

Before the bullet-pierced torso of an unidentified man was discovered on an escarpment near Hamilton in March 1946, Evelyn Dick was unknown outside of her city; one year later, the sometime sex worker and twice-tried murderer was infamous across the country and internationally.Footnote 52 At her first trial for conspiring to murder her husband, John Dick, she was convicted, but the lawyer who appealed the verdict, John J. Robinette, convinced the Court of Appeal for Ontario to set aside the conviction. When she was retried for murder in March 1947, Robinette successfully defended Mrs. Dick, but his client still faced a third murder trial for the culpable homicide of her infant son.Footnote 53 The prosecution argued that, shortly after she had given birth to a healthy baby in hospital in 1944, she had disposed of it. When the police conducted a search of her home for evidence concerning the murder of her husband, they came across a suitcase in the attic that contained the mummified remains of a baby with a cord tied around its neck, encased in concrete and wrapped in a skirt embossed with Evelyn Dick’s name. This incriminating circumstantial evidence, combined with the Children’s Aid Society’s, testimony that she did not relinquish her son for adoption, as she had claimed, provided sufficient evidence for the Crown to prosecute Dick for murder in the spring of 1947, one year before Bill 337 was introduced.

Figure 1. Charged with the ‘torso’ murder of her husband, Evelyn Dick was also charged with the murder of her infant son. Toronto Daily Star, 25 March 1946.

Robinette was paid handsomely by a mysterious donor—allegedly a lover of his client—but, in Dick’s trial for the murder of her infant son, he followed the tactics that Rubletz’s lawyer had used by focusing on cross-examining Crown witnesses and raising doubt about the cause of death. Given the notoriety of the accused, Robinette urged the all-male jury to resist assuming that she was a monster.Footnote 54 However, the adulterous widow, widely believed to be involved in her husband’s murder, was no Annie Rubletz. Robinette enlisted a psychiatrist to persuade the jury that Dick was a victim whose upbringing and mentality had reduced her culpability. According to this doctor, the accused had the mentality of a thirteen-year-old, making her a near moron. “Besides this retardation,” the psychiatrist stated, “she is a constitutional psychopathic character.” The judge, A. M. LeBel, steered the doctor away from his expert diagnostic terminology to the legal concept of criminal responsibility: “there is no question of her ability to understand right and wrong?” the judge asked, and the answer was “no.” Robinette switched tactics to elicit the psychiatrist’s prediction of the accused’s prospect of “rehabilitation and redemption.” The witness thought that they were fair, but only if the woman were to receive psychiatric treatment in prison.Footnote 55 Obviously, this was possible only if the jury found Evelyn Dick guilty of manslaughter and this was the outcome that Robinette did his best to bring about.

The closing remarks of the defence worked on the judge and the jury: Justice LeBel charged the jury that manslaughter was a possible verdict and the jury, after five hours, delivered that verdict, albeit absent a recommendation to mercy.Footnote 56 Justice LeBel (a practising Catholic, one of whose brothers was a priest) used his discretion to set Dick’s punishment at the maximum term. “I see no reason to extend mercy beyond the merciful view the jury took,” the judge opened, as he found “no mitigating circumstances.” Looking directly at the prisoner, LeBel declared: “You have committed a horrible crime,” and for that reason, he sentenced her to spend “the remainder of [her] natural life in prison.”Footnote 57 When Robinette presented his appeal against Dick’s life sentence, he made no headway before the chief justice of the Court of Appeal for Ontario, Robert S. Robertson.Footnote 58 Robinette claimed (with justification) that the sentence was unusually stiff and he accused the trial judge of pandering to the “mass desire for revenge” and of overlooking evidence that others may have been involved in the baby’s death. The court dismissed Robinette’s appeal in a matter of minutes but seventy-seven-year-old Justice Robertson took the time to disparage the prisoner’s immoral character: “The way in which [she] disposed of the child was of a callous nature.” On top of that, Robertson decided that “Mrs. Dick showed a lack of maternal instinct.” Because she had “chosen an evil way of life,” her “mental infirmities” made the “danger of her being at large” greater.Footnote 59 The maximum sentence must stand.

Did the prosecution of Evelyn Dick for the murder of her infant son and her life sentence for manslaughter make the introduction of an infanticide statute inadvisable? On this question, both abolitionists and retentionists could find room for agreement as they debated the infanticide bill, one year after Dick’s conviction. When it came to mothers of newborns, not every woman who killed her baby was wracked with shame or mentally “unbalanced”—some, like Dick, were unnatural, “evil.” Conservative MP Arthur Smith spoke from his criminal court experience, which led him to believe that judges were best placed to determine the punishment that was appropriate for lethal mothers: “we know that some murderers are extremely vicious, while others may be closer to the line.” E. Davey Fulton was against the establishment of a separate noncapital offence of infanticide. He was more comfortable with the thought that “public opinion, as reflected in the mind and action of the jury, would be the factor which determines whether you will have convictions or not.”Footnote 60 Even Diefenbaker asserted the need to retain capital punishment for murders that were particularly “gross” in nature.

Those who objected to the statute could take comfort in the fact that it did not rule out charging a woman with murder and this was exactly what had happened in Dick’s case. Thanks to her top-notch defence lawyer, the notorious woman did not face the same sentence as Annie Rubletz, but her life sentence for manslaughter was inordinately stiff for the 1940s. When Robinette advanced that argument in his appeal, he may have had the Rubletz case in mind: “If this had happened to a young girl from the country, I am of the opinion that the sentence would have been no more than two or three years.”Footnote 61 One year later, the amended Criminal Code set three years as the maximum term of imprisonment for infanticide, passed with the understanding that the death penalty would still apply if the character of the crime and the accused fit the profile of intentional murder.

Conclusion

The restriction of capital punishment to certain kinds of homicide or victims of homicide and the prospect of noncapital sentences for homicide by degree of offence—all of which animated the politics of abolition in the 1950s and 1960s—had roots in post-Confederation criminal law reform. It did not recur until 1948, when the government invented infanticide as a noncapital offence. More than a straightforward remedy for jury nullification, the amendment to the law of homicide was the precursor to the broader rationalization of criminal laws and punishments. Supported by the legal profession’s peak body, the introduction of infanticide recalibrated the law to rectify understandable but unconscionable discretion on the part of juries, judges and prosecutors. Most studies of infanticide take the minister of justice at his word and rely on his stated frustration over the “invariable” exercise of leniency to explain the law’s passage without considering the wider tilt toward modernizing the Criminal Code for postwar Canada, as the establishment of the Royal Commission on its revision in 1949 affirms.Footnote 62 Yet, it was Rubletz’s and Dick’s convictions for infanticidal murder—not acquittals or light sentences for concealment—that played significant roles in this move to limit the death penalty in 1948.

By the time the Royal Commission had delivered its final report in 1954, a new draft code was finalized, with infanticide and the mandatory death penalty for murder retained. However, growing dissatisfaction from prosecutors and judges with respect to the definition of infanticide plus rising calls for abolition prompted further government action. First, the Liberal government acted on the commissioners’ advice to appoint a special joint committee to consider evidence for and against capital punishment.Footnote 63 Second, Parliament amended the infanticide section to increase the punishment to a maximum of five years and to reduce the burden of proof that hampered prosecutions for infanticide.Footnote 64 Significantly, the revised section removed the need to prove a biomedical basis for a mother’s lethal action beyond a reasonable doubt—a change that further marginalized expert medical readings of neonaticidal motivations.Footnote 65 The Joint Committee, which delivered its final report on the death penalty in 1956, recommended its retention on the ground that Canada was not yet sufficiently “civilized” to abolish capital punishment. Although the Committee considered the prospect that all women should be exempt from the death penalty, they rejected it, and they also advised against adopting degrees of murder.Footnote 66 Yet, the invention of infanticide had moved in that very direction in 1948 by introducing a gender-specific noncapital category of culpable homicide. This precedent was followed in 1961, when Canada introduced degrees of murder—capital and noncapital—distinguished, in part, by the status of the victim. In 1967, the first death-penalty moratorium was introduced, and in 1976, Canada abolished the death penalty.Footnote 67 The infanticide statute did not lead to that outcome but its nexus with questions over the deterrent justification of capital punishment, previously overlooked, is evident and its entanglement with broader efforts to modernize criminal law underscores its relevance to the history of the death penalty.