Introduction

In this study, we present a new Ce-bearing mineral, anningite‐(Ce), with the ideal chemical formula (Ca0.5Ce4+0.5)(VO4). Discovered within a phosphate coprolite from the sand-dominated sediments of the Gara Samani Formation in Algeria, anningite‐(Ce) belongs to the xenotime group and is isostructurally related to wakefieldite-(Ce) (Deliens and Piret, Reference Deliens and Piret1977; Howard, Reference Howard1995). Wakefieldite-(Ce) is represented by the formula AVO4, where the A site is occupied by Ce3+, but this position can also be occupied by other rare earth element (REE) cations as in the minerals wakefieldite-(La), wakefieldite-(Nd) or wakefieldite-(Y) (Chakoumakos et al., Reference Chakoumakos, Abraham and Boatner1994; Witzke et al., Reference Witzke, Kolitsch, Warnsloh and Göske2008; Cadoni et al., Reference Cadoni, Ciriotti and Ferraris2011), which can be collectively referred to as wakefieldite-REEs (Metysová et al., Reference Metysová, Götze, Leichmann, Škoda, Strnad, Drahota and Grygar2016). In anningite‐(Ce), the A site is predominantly occupied by Ca2+ and Ce4+ in a 1:1 ratio. Both wakefieldite-REEs and anningite-(Ce) exhibit a xenotime-type structure, in which A cations occupy eight-coordinated structural sites, while V5+ cations reside in isolated tetrahedra sharing corners and edges with the aforementioned dodecahedra. Due to their analogous chemical properties, the possible formation of an isomorphic series between these two minerals – wakefieldite-Ce and anningite-(Ce) – is of considerable interest.

Orthovanadates containing REEs have been studied widely due to their intriguing physical properties, including luminescence and phase transitions (Hirata and Watanabe, Reference Hirata and Watanabe2001; Petit et al., Reference Petit, Lan, Cowin, Kraft and Tao2011). Consequently, intermediate phases between wakefieldite‐(Ce) and anningite‐(Ce) have been synthesized over the last two decades (Range et al., Reference Range, Meister and Klement1990; Chakoumakos et al., Reference Chakoumakos, Abraham and Boatner1994; Petit et al., Reference Petit, Lan, Cowin, Kraft and Tao2011). However, an ideal phase composition for anningite‐(Ce) has not yet been achieved. Only compositions with similar Ca and Ce contents at the A site have been obtained – (Ce0.5875Ca0.4125)VO4 (Hirata and Watanabe, Reference Hirata and Watanabe2001; Petit et al., Reference Petit, Lan, Cowin, Kraft and Tao2011). Above the Ca content of 0.4125 apfu, another phase, Ca2V2O7, started to appear in the synthetic samples (Petit et al., Reference Petit, Lan, Cowin, Kraft and Tao2011).

The substitution of Ce4+ for Ce3+, accompanied by the incorporation of Ca into the structure of synthetic wakefieldite-(Ce) analogues, has also been observed in the synthetic phase (Shen et al., Reference Shen, Huang, Zheng, Guo, Chen, Peng and Ding2011). Currently, the Ce3+VO4–(Ca0.5Ce4+0.5)VO4 solid solution is still attracting considerable industrial interest as a potential new material for sodium-ion batteries, and research on the structure and formation conditions of phases similar to anningite-(Ce) is ongoing (Liang et al., Reference Liang, Xiong, Yang, Liu and Che2021). Therefore, we believe that the discovery of a xenotime-structured phase with a 1:1 Ca:Ce ratio is highly significant for the development of new synthetic materials.

The name anningite-(Ce) was chosen in honour of Mary Anning (1799–1847), an English fossil collector and pioneering palaeontologist. Among many of her achievements, she was the first to recognise that the so-called ‘bezoar stones’ were actually fossilised excrements, now known as coprolites. As the mineral was found in a coprolite, it is fitting to name it after Mary Anning, as her pioneering work on coprolites laid the foundation for this discovery.

Anningite-(Ce) was approved by the Commission on New Minerals, Nomenclature, and Classification of the International Mineralogical Association (IMA2024-060; Środek et al., Reference Środek, Juroszek, Cametti, Benyoucef, Bouchemla, Krzykawski and Salamon2025) with the symbol Aig-Ce. The type material was deposited in the mineralogical collection of the Natural History Museum in Mainz under the catalogue number NHMMZ M 2024/1 LS.

This article provides a detailed description of the new mineral anningite-(Ce) from the type locality of the Gara Samani Formation in Algeria. It also includes a comparison of the obtained results with literature data on phases with similar structure and chemical composition, such as wakefieldite-(Ce).

Methods of investigation

Fossils containing Ce-bearing minerals were collected in 2020 during fieldwork conducted in the sedimentary rocks of the Gara Samani Formation, Algeria. The aim of this work was to collect faunal and coprofaunas specimens for further palaeontological analysis.

Preliminary studies of the morphology and optical properties of anningite-(Ce) were carried out using an Olympus BX51 optical microscope. Detailed analyses of the morphology and chemical composition of Ce-bearing phases and associated minerals were performed using a Phenom XL scanning electron microscope (Institute of Earth Sciences, Faculty of Natural Sciences, University of Silesia, Poland) and a Cameca SX100 electron microprobe (Institute of Geochemistry, Mineralogy and Petrology, University of Warsaw, Poland). Analyses were performed on polished, carbon-coated surfaces under high vacuum conditions. Analyses were carried out using output settings: 15 kV, 12 nA and concentrated beam (diameter ∼1 μm), with the following lines and standards: CaKα, SiKα – wollastonite; CeLα – synthetic CePO4; VKα – synthetic V; PKα – synthetic Ca5P3O12Cl; SKα – synthetic ZnS; ZrLα – zircon; UMα – synthetic UO2; AlKα – orthoclase; YLα – YAG; LaLα – synthetic LaPO4; NdLα – synthetic NdPO4; SmLα – synthetic SmPO4; GdLα – synthetic GdPO4; and DyLα – synthetic DyPO4. The contents of other measured elements (F, Cl, Fe, Na, Al, Mg, Mn, Ba, Ti, Cr, K, Zn, Sr and As) were below the detection limit of the electron microprobe.

Raman spectroscopy of anningite-(Ce) was performed using a WITec CRM alpha 300 R confocal Raman microscope (Institute of Materials Science, University of Silesia, Poland) equipped with an air-cooled solid-state laser (λ = 532 nm) and a CCD camera operating at –61°C. An air Olympus MPLAN 100x/0.9NA objective was used to collect the Raman spectra of anningite-(Ce). The Raman scattered light was focused onto a multi-mode fibre (50 μm diameter) and a monochromator with a 600 line/mm grating. An integration time of 1.5 s per spectrum and the accumulation of 70 scans were used to collect the spectra. The accuracy and resolution of the measurements were ±1 cm–1 and 3 cm–1, respectively.

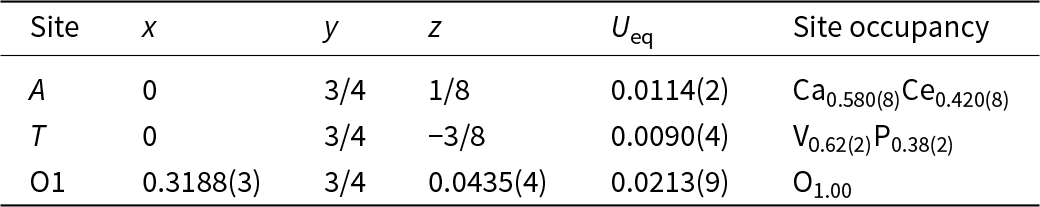

Structural studies of anningite-(Ce) were performed on a four-circle XtaLAB Synergy R diffractometer equipped with a micro-focused sealed X-ray tube and a HyPix-Arc 100 detector (Institute of Geological Sciences, University of Bern, Switzerland). The measurement was conducted under ambient conditions at 293 K and the data were collected using MoKα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å). Data reduction and determination of unit-cell parameters were performed using CrysAlisPro software (Rigaku Oxford Diffraction, 2023). The structure of anningite-(Ce) was solved by direct methods (SHELXS, Sheldrick, Reference Sheldrick2008) in the I41/amd space group and refined using SHELXL-2014 (Sheldrick, Reference Sheldrick2015). Mixed scattering curves were used to refine both the A and T sites. The A site was refined with Ca and Ce (0.58 Ca + 0.42 Ce), while the T site was refined with V and P (0.62 V + 0.38 P) scattering factors, respectively. The final structure refinement converged to R = 2.07%. Further details of the data collection and crystal structure refinement are given in Table 1.

Table 1. Parameters for X-ray data collection and crystal-structure refinement for anningite-(Ce)

*wR 2 (Weighting scheme): w = 1/[σ2(Fo2) + (0.0122P)2 + 0.7121P], where P = (Fo2+2Fc2)/3

Occurrence, mineral association and physical properties of anningite-(Ce)

Anningite-(Ce) has been found in sand-dominated sediments of the Gara Samani Formation, Algeria (29°41’31.14”N; 1°56’20.62”E). This formation is located ∼40 km east of the Meguidene village, 2 km southeast of the RN 51 national road linking the towns of Timimoun and El Menia. At the foot of the Gara Samani, within a 100–300 m wide strip, is the upper part of the Intercalary Continental outcrops (‘Continental Intercalaire’ series sensu Kilian, Reference Kilian1931). Its basal part is sand-dominated and preserves one of the most diverse continental vertebrate fauna and coprofauna of the latest Albian-early Cenomanian age known from North Africa (Benyoucef et al., Reference Benyoucef, Pérez-García, Bendella, Ortega, Vullo, Bouchemla and Ferré2022). As a result, palaeontological research is actively conducted in this area, focusing on the excavation and study of fossil remains.

Anningite-(Ce) was identified in one of the collected coprolites, whose matrix consists mainly of fine-crystalline fluorapatite with accessory baryte, calcite, quartz and hematite (Fig. 1a). This fossil exhibited an outer layer of much darker colour, composed of low-temperature Fe-oxides and hydroxides, mainly limonite, in which rounded quartz grains are interbedded together with smaller grains of pyrite, ilmenite and K-feldspar. Additionally, accessory micrometric (1–2 μm in diameter) spherical unidentified phases containing REEs, mainly Ce and Nd, are present in this layer. This coprolite was characterised by high porosity, with voids of oval shape and ∼2–3 mm in diameter (Fig. 1b). A thin layer of calcite crystallised on the walls of the voids. Anningite-(Ce) was found only in the voids within the fossil and was not detected in the matrix forming the coprolite. In addition to anningite-(Ce), other Ce-bearing minerals forming spherical clusters were also present in the voids. However, their small size (1–2 μm in diameter) prevented their identification.

Figure 1. Photograph of a coprolite containing anningite-(Ce). (a) Overview of the entire fossil; (b) close-up of pores containing aggregates of anningite-(Ce).

Anningite-(Ce) forms small crystals (30–40 μm in length and ∼6–8 μm in width) with a tetragonal columnar habit. The crystals typically occur in compact divergent or radial aggregates up to 100 μm in size (Fig. 2a,b). Anningite-(Ce) is green in colour with a white streak and vitreous lustre. No cleavage was observed, only an uneven or conchoidal fracture. Due to its small size, it was not possible to measure microhardness, however based on comparison with other members of the xenotime group, hardness was estimated to be ∼4–5 on the Mohs scale. Based on structural data and the empirical formula, the density of anningite-(Ce) was calculated to be 3.887 g/cm3.

Figure 2. (a,b) BSE (back-scattered electron) images of anningite-(Ce) crystals and associated minerals within the pores. Abbreviations: Agi-Ce – anningite-(Ce); Cal – calcite; Ce-O – unidentified Ce-bearing phase; Fap – fluorapatite.

Results

Chemical composition

The analysed anningite-(Ce) crystals were homogeneous in terms of chemical composition, which can be expressed by the formula: (Ca0.52Ce4+0.47Y3+0.01)Σ1.00[(VO4)0.88(PO4)0.05(SO4)0.06(SiO4)0.01]Σ1.00, which can be simplified to (Ca,Ce4+)[(V,P,S)O4] (Table 2). On this basis, the end-member formula was determined as: (Ca0.5Ce4+0.5)(VO4). The presence of REEs with 3+ valency was also investigated during the chemical composition analyses of anningite-(Ce). However, their amounts were negligible and not considered meaningful to include in the end-member chemical formula.

Table 2. Chemical data (in wt.%) for anningite-(Ce)

Crystal structure

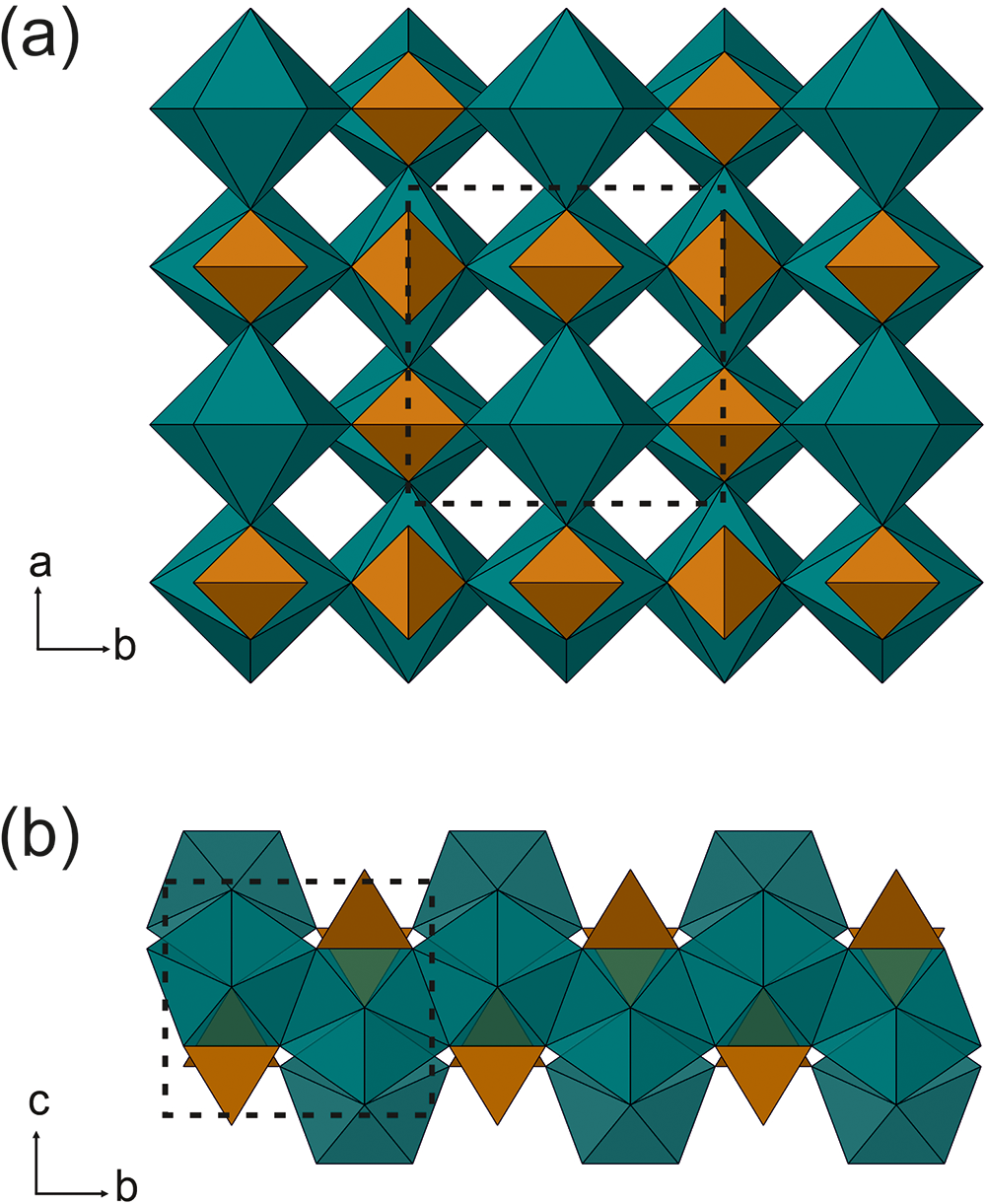

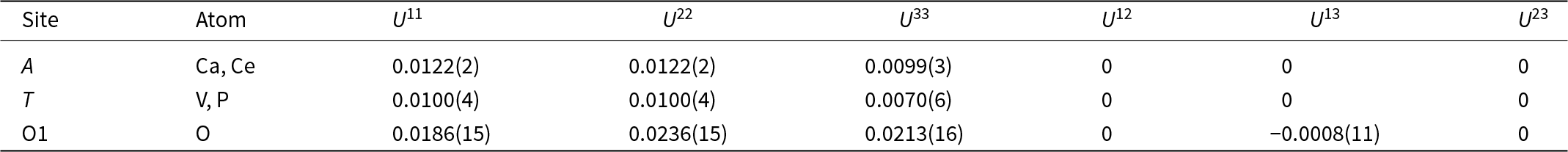

Atomic coordinates, site occupancies, equivalent displacement parameters and selected bond distances are given in Tables 3, 4 and 5. The results obtained confirm that anningite-(Ce) has a xenotime-type structure, which is also the case for the crystal structures of wakefieldite-REEs, members of the xenotime group (Deliens and Piret, Reference Deliens and Piret1977, Reference Deliens and Piret1986; Miles, Reference Miles, Hogarth and Russell1971; Witzke et al., Reference Witzke, Kolitsch, Warnsloh and Göske2008; Moriyama et al., Reference Moriyama, Miyawaki, Yokoyama, Matsubara, Hirano, Murakami and Watanabe2010). This crystal structure shows a polyhedral framework consisting of corner- and edge-sharing TO4 tetrahedra and AO8 triangular dodecahedra (Fig. 3). The presence of interstitial cavities forming channels parallel to the c-axis is a feature of wakefieldite-REEs (Fig. 3a). Along the c-axis the AO8 polyhedra are separated by TO4 edge-shared tetrahedra, whereas along the a/b plane they form AO8 edge-shared zigzag chains (Fig. 3b).

Figure. 3. Xenotime-type crystal structure of anningite-(Ce), visualized using the CrystalMaker software. (a) Polyhedral framework with AO8 dodecahedra (green) and TO4 tetrahedra (brown) and empty channels parallel to the c-axis; (b) a fragment of the structure with AO8 edge-shared zigzag chains along the b-axis. The unit cell is shown as a dotted line.

Table 3. Atomic coordinates (x,y,z), equivalent displacement parameters (U eq, Å2), and site occupancies of anningite-(Ce)

Table 4. Anisotropic displacement parameters (Å2) of anningite-(Ce)

Table 5. Selected interatomic distances (Å) and bond-valence sum (BVS*) of anningite-(Ce)

In the anningite-(Ce) structure, the A site shows a mixed occupancy with Ca partially substituted by Ce and surrounded by eight O atoms. The occupancy refinement of this site converges to [Ca0.580(8)Ce0.420(8)]. The interatomic distances for the dodecahedron (AO8) range from 2.337(2) Å to 2.467(3) Å. A similar observation is made for the TO4 site when the partial substitution of V by P is considered. For this tetrahedrally-coordinated site the refined site occupancy is [V0.62(2)P0.38(2)], corresponding to an electron density of 21.46 e – and a mean T–O distance of 1.678 Å. Such a high phosphorus enrichment and the difference between the ionic radii of P5+ (0.17 Å) and V5+ (0.355 Å) (Shannon, Reference Shannon1976) reduces the T–O compared to pure Ce3+VO4, 1.712 Å (Petit et al., Reference Petit, Lan, Cowin, Kraft and Tao2011).

Due to the small size of the anningite-(Ce) crystals and the presence of overgrowths of other minerals within the agglomerates, reliable powder diffraction analysis could not be performed. As a result, powder diffraction data were generated from the structural information obtained from single-crystal analysis (Supplementary Table S1).

Raman spectroscopy

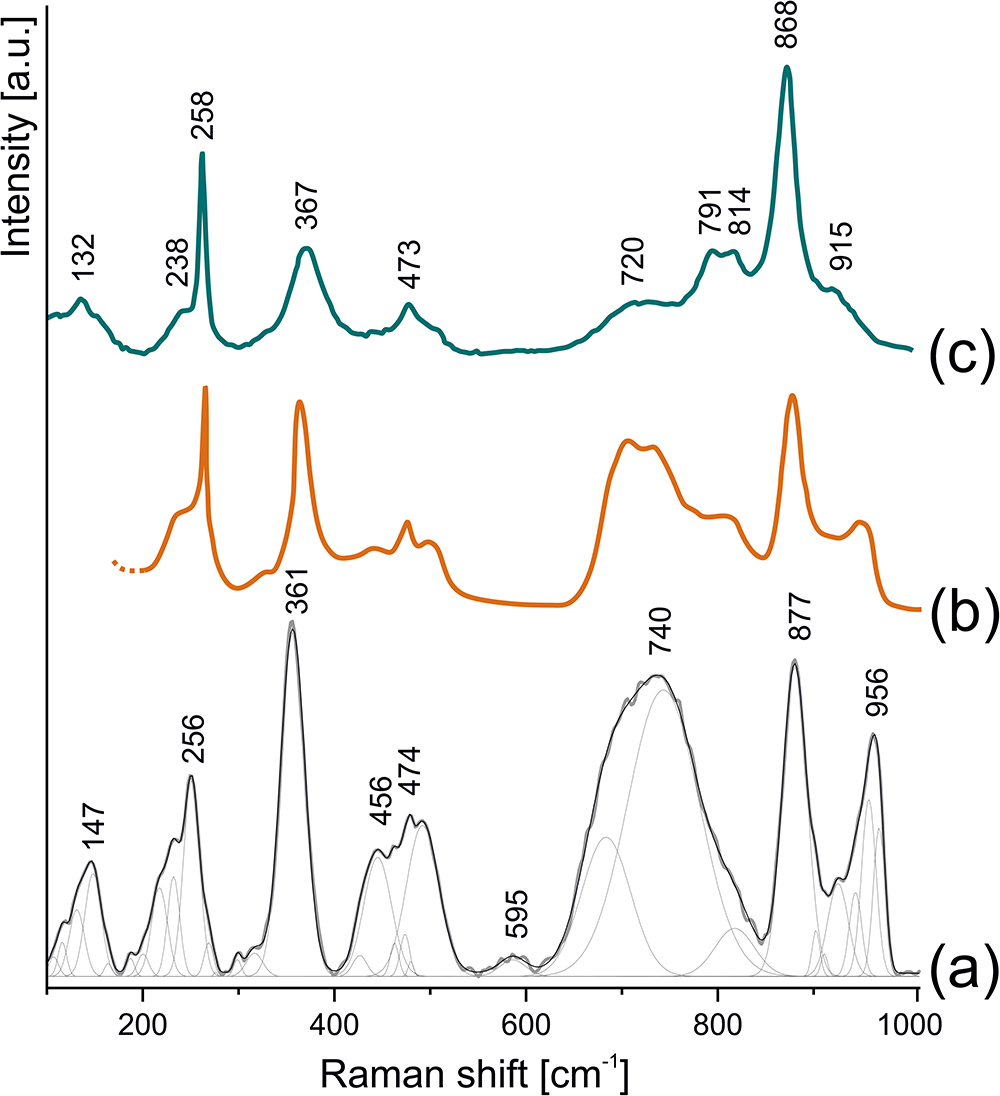

The Raman spectrum of anningite-(Ce) shows several intense bands in the 100–1000 cm–1 spectral region (Fig. 4a). The main bands are attributed to the vibrations of the VO4 group located at 877 cm–1 (ν1), 474 cm–1 (ν4), and 361 cm–1 (ν2). The ν3 vibration appears as a shoulder of the broad band at 790 cm–1. In addition, a band at 256 cm–1 is attributed to CeO8 stretching modes, as indicated by theoretical calculations (Shen et al., Reference Shen, Huang, Zheng, Guo, Chen, Peng and Ding2011). Three broad bands with maxima at 740, 456–474, and 956 cm–1 are also observed. Their presence is related to the substitution of Ce3+ by Ce4+ and Ca2+ ions, which causes lattice shrinkage and shortens V–O bond lengths within the VO4 tetrahedra. These structural changes alter the vibrational frequencies, leading to the appearance of the broad bands mentioned above (Shen et al., Reference Shen, Huang, Zheng, Guo, Chen, Peng and Ding2011). No Raman bands corresponding to O–H stretching were detected in the range of 3000 to 3500 cm–1.

Figure 4. Collected Raman spectra of (a) anningite-(Ce), compared with (b) synthetic phase Ce0.6Ca0.4VO3.8 (Hirata and Watanabe, Reference Hirata and Watanabe2001), and (c) natural wakefieldite-(Ce) (Tumiati et al., Reference Tumiati, Merlini, Godard, Hanfland and Fumagalli2020).

The Raman spectrum of anningite-(Ce) closely resembles that of its synthetic analogue with comparable chemical composition (Ce0.6Ca0.4VO3.8) (Fig. 4b; Hirata and Watanabe, Reference Hirata and Watanabe2001; Shen et al., Reference Shen, Huang, Zheng, Guo, Chen, Peng and Ding2011). A comparison of our data with the Raman spectrum of wakefieldite-(Ce) reveals shifts in the 877, 361 and 256 cm–1 bands (Fig. 4c; Tumiati et al., Reference Tumiati, Merlini, Godard, Hanfland and Fumagalli2020). In particular, the ν1 band in wakefieldite-(Ce) appears at lower frequencies, while the ν2 and CeO8 stretching bands are observed at slightly higher frequencies. Similar trends have been reported for synthetic wakefieldite-(Ce) and transitional compositions between CeVO4 and Ce0.6Ca0.4VO3.8 (Hirata and Watanabe, Reference Hirata and Watanabe2001; Shen et al., Reference Shen, Huang, Zheng, Guo, Chen, Peng and Ding2011). These observations indicate that the Raman spectrum of anningite-(Ce) shows the systematic shift of bands associated with VO4 group vibrations as Ce3+ is substituted by Ce4+ and Ca2+. This substitution distorts the VO4 tetrahedra, changes the vibrational frequencies and provides clear evidence for the incorporation of Ce4+ into the anningite-(Ce) structure (Shen et al., Reference Shen, Huang, Zheng, Guo, Chen, Peng and Ding2011).

Discussion

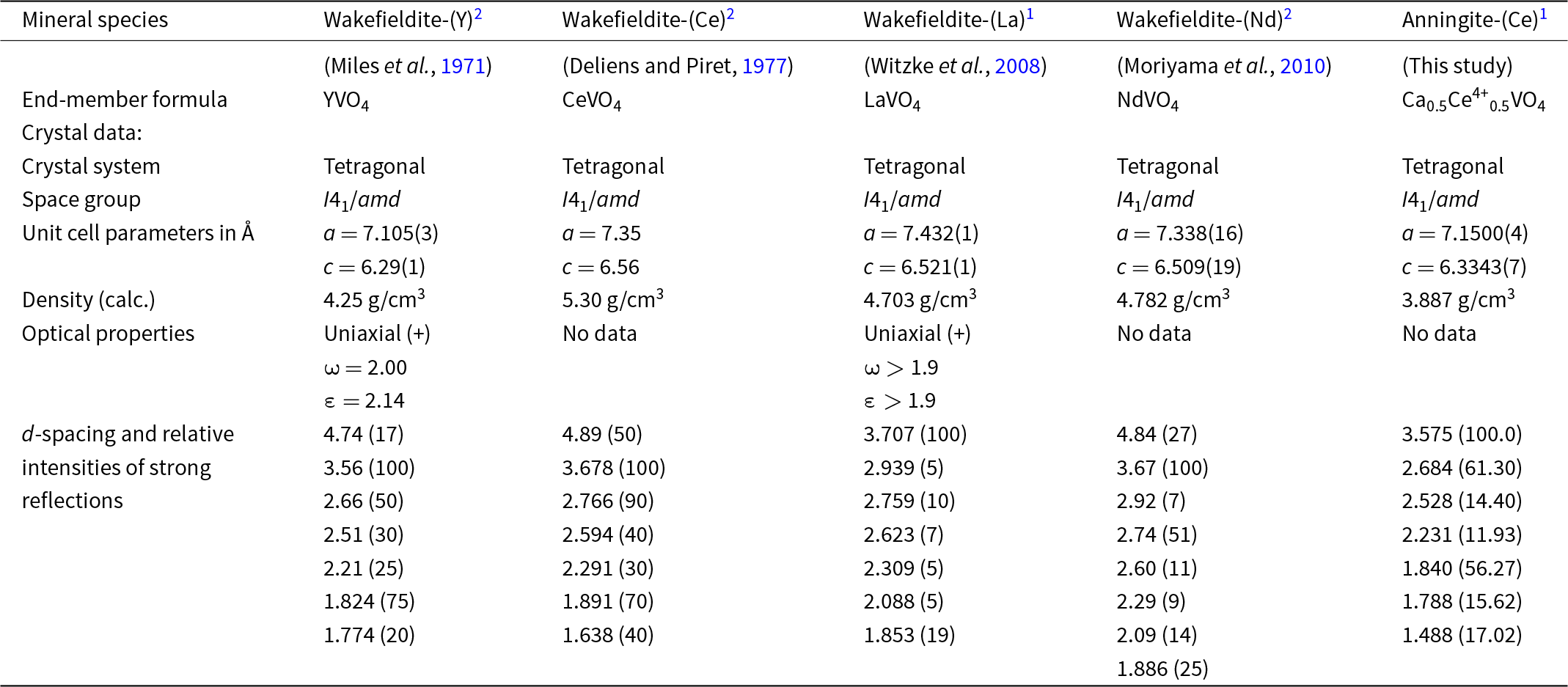

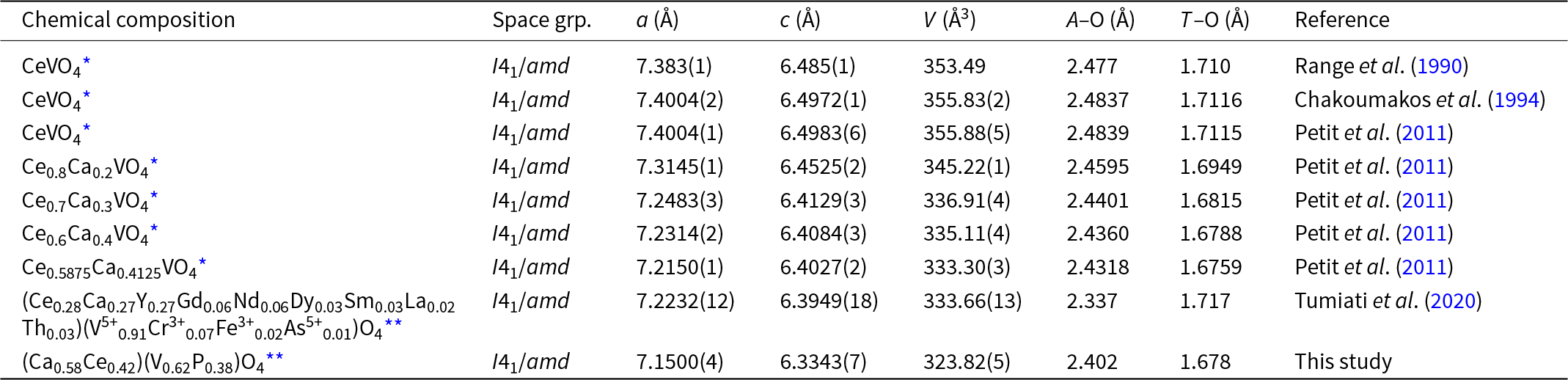

Anningite-(Ce) and wakefieldite-(Ce) are isostructural minerals. Interestingly, in the structure of wakefieldite-(Ce) the substitution 2Ce3+ → Ca2+ + Ce4+ can occur. As smaller cations replace Ce3+ at the A site, a corresponding change in the unit-cell parameters is observed (Table 6). A gradual decrease in these parameters with the substitution of Ce4+ and Ca2+ for Ce3+ has been documented in synthetic solid solutions with the formula Ce1–xCaxVO4 (0 < x < 0.4124) (Table 7) (Range et al., Reference Range, Meister and Klement1990; Chakoumakos et al., Reference Chakoumakos, Abraham and Boatner1994; Petit et al., Reference Petit, Lan, Cowin, Kraft and Tao2011). Anningite-(Ce) follows this trend, exhibiting the smallest unit-cell dimensions among both natural wakefieldite-REEs (with the exception of wakefieldite-(Y) (Table 6) and synthetic analogues (Table 7). Moreover, anningite-(Ce) has a significantly lower density compared to other wakefieldite-REEs (Table 6). These results suggest that a continuous anningite-(Ce)–wakefieldite-(Ce) solid-solution series may occur naturally.

Table 6. Comparison between anningite-(Ce) and other natural wakefieldite-REEs or members of the xenotime group

Notes:

1 single-crystal X-ray data;

2 powder X-ray diffraction data

Table 7. Comparison between anningite-(Ce) and other Ce/Ca-bearing synthetic and natural orthovanadates

Notes:

* – synthetic material;

** – natural sample

It might be questioned whether the oxidation state of cerium was correctly determined during the conducted studies. In this context, the decrease in unit-cell parameters with increasing Ca2+ content in the structure of anningite-(Ce) is a significant observation. As the ionic radius of Ca2+ (1.12 Å) is only slightly smaller than that of Ce3+ (1.14 Å), the Ce3+ → Ca2+ substitution alone should not cause a significant contraction of the unit-cell. However, the observed reduction in cell dimensions (Table 7) suggests the additional presence of smaller cations, such as Ce4+ (0.97 Å). Literature data (Table 6) indicate that only wakefieldite-(Y) has unit-cell dimensions comparable to those of anningite-(Ce). Given the ionic radius of Y3+ (1.019 Å), this supports the assumption that cations with a diameter close to 1.00 Å are present in the structure of anningite-(Ce). Furthermore, Raman spectroscopy analyses clearly confirm the incorporation of Ce4+ into the crystal lattice. Based on this evidence, anningite-(Ce) can be distinguished as a mineral distinct from wakefieldite-(Ce), in which cerium is in the trivalent oxidation state.

Among the REE, cerium is unique in that it occurs in both the tetravalent and trivalent states. The presence of Ce3+ or Ce4+ depends on the oxygen activity in the environment, so the distribution of Ce3+ and Ce4+ in minerals is strongly related to redox conditions (Xu et al., Reference Xu, Miller and Claiborne2024). In most environments, cerium exists predominantly as Ce3+, except under strongly oxidising conditions (Burnham and Berry, Reference Burnham and Berry2012, Reference Burnham and Berry2014). The occurrence of Ce4+ substitutions in mineral structures is rare, but it is known, for example, from the structure of cerianite-(Ce), (Ce4+,Th)O2 (Graham, Reference Graham1955). More importantly, the recent discovery of the new mineral stetindite-(Ce), Ce(SiO4) has shown that tetravalent Ce can also occupy cationic positions in a xenotime structure under natural conditions (Schlüter et al., Reference Schlüter, Malcherek and Husdal2009). Both minerals form in a strongly oxidising environment (Chakrabarty et al., Reference Chakrabarty, Mitchell, Ren, Sen and Pruseth2013; Schlüter et al., Reference Schlüter, Malcherek and Husdal2009). Therefore, it is most likely that anningite-(Ce) requires such an environment to form. However, fresh excrements represent a reducing environment, which would not facilitate the formation of anningite-(Ce), therefore, its crystallisation is most likely to be related to processes that occurred after the lithification of the fossil. Additionally, the restriction of anningite-(Ce) to porous spaces suggests that the mineral is associated with processes occurring after the formation of the coprolite matrix. Therefore, the crystallisation of anningite-(Ce) is most likely associated with solutions containing light REEs and weathering processes.

Supplementary material

The following supplementary materials are included: cif and check-cif files of anningite-(Ce), and Table S1: Calculated powder X-ray diffraction pattern for anningite-(Ce). The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1180/mgm.2025.10110

Competing interests

The authors declare none.