1. Introduction

Throughout this article, we adopt the following conventions: A vacuous product is defined as the multiplicative identity. A vacuous sum is defined as the additive identity. Let

![]() $\mathbb N$

denote the set of all nonnegative integers. Assume that

$\mathbb N$

denote the set of all nonnegative integers. Assume that

![]() $\mathbb F$

is an algebraically closed field. Let

$\mathbb F$

is an algebraically closed field. Let

![]() $\mathbb F^\times $

denote the multiplicative group of all nonzero scalars in

$\mathbb F^\times $

denote the multiplicative group of all nonzero scalars in

![]() $\mathbb F$

. Fix a scalar

$\mathbb F$

. Fix a scalar

![]() $q\in \mathbb F^\times $

with

$q\in \mathbb F^\times $

with

![]() $q^4\not =1$

. Let x denote an indeterminate over

$q^4\not =1$

. Let x denote an indeterminate over

![]() $\mathbb F$

. For any

$\mathbb F$

. For any

![]() $a\in \mathbb F$

let

$a\in \mathbb F$

let

![]() $\sqrt {a}\in \mathbb F$

denote a fixed root of

$\sqrt {a}\in \mathbb F$

denote a fixed root of

![]() $x^2-a$

. For any finite-dimensional vector space V over

$x^2-a$

. For any finite-dimensional vector space V over

![]() $\mathbb F$

, let

$\mathbb F$

, let

![]() $\dim V$

denote the dimension of V. Given a left (resp. right) action of a group G on a set S, the notation

$\dim V$

denote the dimension of V. Given a left (resp. right) action of a group G on a set S, the notation

![]() $G\backslash S$

(resp.

$G\backslash S$

(resp.

![]() $S/G$

) stands for the set of all G-orbits in S.

$S/G$

) stands for the set of all G-orbits in S.

The Askey–Wilson algebras [Reference Lévy-Leblond and Lévy-Nahas35], [Reference Terwilliger41], [Reference Zhedanov49] are a family of unital associative algebras defined by generators and relations. These algebras describe the bispectral property of orthogonal polynomials in the Askey scheme [Reference Koekoek, Lesky and Swarttouw31]. Since the advent of Askey–Wilson algebras, they have been found to have applications in various fields, such as P- and Q-polynomial association schemes [Reference Bannai, Bannai, Ito and Tanaka2], [Reference Go13], [Reference Huang24–Reference Huang and Wen29], [Reference Miklavič36], [Reference Terwilliger and Žitnik47], spin models [Reference Curtin5], [Reference Curtin6], [Reference Nomura and Terwilliger39], [Reference Nomura and Terwilliger40], Leonard pairs [Reference Huang15], [Reference Leonard34], [Reference Terwilliger, Marcellán and Assche42], [Reference Terwilliger and Vidunas46], [Reference Vidūnas48], Lie algebras [Reference Alnajjar1], [Reference Bockting-Conrad and Huang3], [Reference Curtin4], [Reference Genest, Vinet and Zhedanov7], [Reference Genest, Vinet and Zhedanov10], [Reference Nomura and Terwilliger37], [Reference Terwilliger43], double affine Hecke algebras [Reference Genest, Vinet and Zhedanov12], [Reference Huang20], [Reference Huang22], [Reference Huang23], [Reference Ito and Terwilliger30], [Reference Koornwinder32], [Reference Koornwinder33], [Reference Nomura and Terwilliger38], [Reference Terwilliger45], coupling problems [Reference Granovskiĭ and Zhedanov14], [Reference Huang18], [Reference Huang19], [Reference Lévy-Leblond and Lévy-Nahas35], and superintegrable systems [Reference Genest, Vinet and Zhedanov8], [Reference Genest, Vinet and Zhedanov9], [Reference Genest, Vinet and Zhedanov11]. The universal Askey–Wilson algebra is a central extension of the Askey–Wilson algebras associated with the most general orthogonal polynomials in the Askey scheme, namely the Askey–Wilson polynomials and the q-Racah polynomials. The definition is presented as follows:

Definition 1.1 [Reference Terwilliger44, Definition 1.2]

The universal Askey–Wilson algebra

![]() $\triangle _q$

is a unital associative algebra over

$\triangle _q$

is a unital associative algebra over

![]() $\mathbb F$

defined by generators and relations. The generators are

$\mathbb F$

defined by generators and relations. The generators are

![]() $A,B,C$

and the relations assert that each of

$A,B,C$

and the relations assert that each of

$$ \begin{align} A+ \frac{qBC-q^{-1}CB}{q^2-q^{-2}}, \qquad B+\frac{qCA-q^{-1}AC}{q^2-q^{-2}}, \qquad C+ \frac{qAB-q^{-1}BA}{q^2-q^{-2}} \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} A+ \frac{qBC-q^{-1}CB}{q^2-q^{-2}}, \qquad B+\frac{qCA-q^{-1}AC}{q^2-q^{-2}}, \qquad C+ \frac{qAB-q^{-1}BA}{q^2-q^{-2}} \end{align} $$

is central in

![]() $\triangle _q$

.

$\triangle _q$

.

Let

![]() $\alpha ,\beta ,\gamma $

denote the central elements of

$\alpha ,\beta ,\gamma $

denote the central elements of

![]() $\triangle _q$

obtained by multiplying the elements in (1.1) by

$\triangle _q$

obtained by multiplying the elements in (1.1) by

![]() $q+q^{-1}$

, respectively. Equivalently,

$q+q^{-1}$

, respectively. Equivalently,

$$ \begin{align} \frac{\alpha}{q+q^{-1}} &= A+\frac{qBC-q^{-1}CB}{q^2-q^{-2}}, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \frac{\alpha}{q+q^{-1}} &= A+\frac{qBC-q^{-1}CB}{q^2-q^{-2}}, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \frac{\beta}{q+q^{-1}}&=B+\frac{qCA-q^{-1}AC}{q^2-q^{-2}}, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \frac{\beta}{q+q^{-1}}&=B+\frac{qCA-q^{-1}AC}{q^2-q^{-2}}, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \frac{\gamma}{q+q^{-1}}&=C+\frac{qAB-q^{-1}BA}{q^2-q^{-2}}. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \frac{\gamma}{q+q^{-1}}&=C+\frac{qAB-q^{-1}BA}{q^2-q^{-2}}. \end{align} $$

Proposition 1.2. The algebra

![]() $\triangle _q$

has a presentation given by generators

$\triangle _q$

has a presentation given by generators

![]() $A,B,\alpha ,\beta ,\gamma $

and the relations assert that

$A,B,\alpha ,\beta ,\gamma $

and the relations assert that

![]() $\alpha ,\beta ,\gamma $

are central in

$\alpha ,\beta ,\gamma $

are central in

![]() $\triangle _q$

and

$\triangle _q$

and

$$ \begin{align} \alpha =& \frac{B^2A-(q^2+q^{-2})BAB+AB^2+(q^2-q^{-2})^2A+(q-q^{-1})^2B\gamma} {(q-q^{-1})(q^2-q^{-2})}, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \alpha =& \frac{B^2A-(q^2+q^{-2})BAB+AB^2+(q^2-q^{-2})^2A+(q-q^{-1})^2B\gamma} {(q-q^{-1})(q^2-q^{-2})}, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \beta = & \frac{A^2B-(q^2+q^{-2})ABA+BA^2+(q^2-q^{-2})^2B+(q-q^{-1})^2A\gamma}{(q-q^{-1})(q^2-q^{-2})}. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \beta = & \frac{A^2B-(q^2+q^{-2})ABA+BA^2+(q^2-q^{-2})^2B+(q-q^{-1})^2A\gamma}{(q-q^{-1})(q^2-q^{-2})}. \end{align} $$

Proof. The relations (1.5) and (1.6) are obtained by applying (1.4) to eliminate C from (1.2) and (1.3).

Let V denote a

![]() $\triangle _q$

-module. For any

$\triangle _q$

-module. For any

![]() $\mu \in \mathbb F^\times $

define

$\mu \in \mathbb F^\times $

define

Note that

![]() $V(\mu )=V(\mu ^{-1})$

for any

$V(\mu )=V(\mu ^{-1})$

for any

![]() $\mu \in \mathbb F^\times $

. A scalar

$\mu \in \mathbb F^\times $

. A scalar

![]() $\mu \in \mathbb F^\times $

is called a weight of V whenever

$\mu \in \mathbb F^\times $

is called a weight of V whenever

![]() $V(\mu )\not =\{0\}$

. In this case,

$V(\mu )\not =\{0\}$

. In this case,

![]() $V(\mu )$

is called the weight space of V with weight

$V(\mu )$

is called the weight space of V with weight

![]() $\mu $

and every nonzero

$\mu $

and every nonzero

![]() $v\in V(\mu )$

is called a weight vector of V with weight

$v\in V(\mu )$

is called a weight vector of V with weight

![]() $\mu $

.

$\mu $

.

Lemma 1.3. For any

![]() $\triangle _q$

-module V and any weight

$\triangle _q$

-module V and any weight

![]() $\mu $

of V, the following relations hold:

$\mu $

of V, the following relations hold:

-

(i)

$(B-\mu q^2-\mu ^{-1} q^{-2})(B-\mu q^{-2}-\mu ^{-1} q^2)A V(\mu )\subseteq V(\mu )$

.

$(B-\mu q^2-\mu ^{-1} q^{-2})(B-\mu q^{-2}-\mu ^{-1} q^2)A V(\mu )\subseteq V(\mu )$

. -

(ii)

$(B-\mu q^2-\mu ^{-1} q^{-2}) (B-\mu -\mu ^{-1}) AV(\mu )\subseteq V(\mu q^{-2})$

.

$(B-\mu q^2-\mu ^{-1} q^{-2}) (B-\mu -\mu ^{-1}) AV(\mu )\subseteq V(\mu q^{-2})$

. -

(iii)

$(B-\mu q^{-2}-\mu ^{-1} q^{2}) (B-\mu -\mu ^{-1}) AV(\mu )\subseteq V(\mu q^{2})$

.

$(B-\mu q^{-2}-\mu ^{-1} q^{2}) (B-\mu -\mu ^{-1}) AV(\mu )\subseteq V(\mu q^{2})$

.

Proof. (i): Let

![]() $v\in V(\mu )$

be given. Applying both sides of (1.5) to v, we find that

$v\in V(\mu )$

be given. Applying both sides of (1.5) to v, we find that

is equal to

![]() $(q-q^{-1})^2$

times

$(q-q^{-1})^2$

times

Since

![]() $\alpha $

and

$\alpha $

and

![]() $\gamma $

are central in

$\gamma $

are central in

![]() $\triangle _q$

, the vectors

$\triangle _q$

, the vectors

![]() $\alpha v$

and

$\alpha v$

and

![]() $\gamma v$

are in

$\gamma v$

are in

![]() $V(\mu )$

. Therefore, (1.8) lies in

$V(\mu )$

. Therefore, (1.8) lies in

![]() $V(\mu )$

. The relation (i) follows.

$V(\mu )$

. The relation (i) follows.

(ii), (iii): The relation (i) implies that

The relations (ii) and (iii) are immediate from the above equation.

Definition 1.4. A weight

![]() $\mu $

of a

$\mu $

of a

![]() $\triangle _q$

-module V is said to be marginal if there exists a weight vector v of V with weight

$\triangle _q$

-module V is said to be marginal if there exists a weight vector v of V with weight

![]() $\mu $

such that

$\mu $

such that

When q is not a root of unity, it has been shown that all finite-dimensional irreducible

![]() $\triangle _q$

-modules have marginal weights and can be constructed from the following infinite-dimensional

$\triangle _q$

-modules have marginal weights and can be constructed from the following infinite-dimensional

![]() $\triangle _q$

-modules up to isomorphism:

$\triangle _q$

-modules up to isomorphism:

Theorem 1.5 [Reference Huang16, §3]

For any

![]() $(a,b,c,\lambda )\in {\mathbb F^\times }^4$

, there exists an infinite-dimensional

$(a,b,c,\lambda )\in {\mathbb F^\times }^4$

, there exists an infinite-dimensional

![]() $\triangle _q$

-module

$\triangle _q$

-module

![]() $M_\lambda (a,b,c)$

satisfying the following conditions:

$M_\lambda (a,b,c)$

satisfying the following conditions:

-

(i) There exists a basis

$\{m_i\}_{i\in \mathbb N}$

for the

$\{m_i\}_{i\in \mathbb N}$

for the

$\triangle _q$

-module

$\triangle _q$

-module

$M_\lambda (a,b,c)$

such that where

$M_\lambda (a,b,c)$

such that where $$ \begin{align*} (A-\theta_i) m_i&=m_{i+1} \qquad \text{for all } i\in \mathbb N,\\ (B-\theta_i^*) m_i&= \varphi_i m_{i-1}\qquad \text{for all }i\in \mathbb N, \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} (A-\theta_i) m_i&=m_{i+1} \qquad \text{for all } i\in \mathbb N,\\ (B-\theta_i^*) m_i&= \varphi_i m_{i-1}\qquad \text{for all }i\in \mathbb N, \end{align*} $$

$m_{-1}$

is interpreted as any vector of

$m_{-1}$

is interpreted as any vector of

$M_\lambda (a,b,c)$

and (1.9)

$M_\lambda (a,b,c)$

and (1.9) $$ \begin{align} \theta_i &= a\lambda^{-1} q^{2i}+ a^{-1} \lambda q^{-2i} \qquad \text{for all }i\in \mathbb N, \end{align} $$

(1.10)

$$ \begin{align} \theta_i &= a\lambda^{-1} q^{2i}+ a^{-1} \lambda q^{-2i} \qquad \text{for all }i\in \mathbb N, \end{align} $$

(1.10) $$ \begin{align} \theta_i^*&= b\lambda^{-1} q^{2i}+ b^{-1} \lambda q^{-2i}\qquad \text{for all }i\in \mathbb N, \end{align} $$

(1.11)

$$ \begin{align} \theta_i^*&= b\lambda^{-1} q^{2i}+ b^{-1} \lambda q^{-2i}\qquad \text{for all }i\in \mathbb N, \end{align} $$

(1.11) $$ \begin{align} \varphi_i &=a^{-1}b^{-1} \lambda q(q^i- q^{-i})(\lambda^{-1}q^{i-1}-\lambda q^{1-i})\\&\qquad \times \, (q^{-i}- abc\lambda^{-1}q^{i-1})(q^{-i} - abc^{-1}\lambda^{-1}q^{i-1})\qquad \text{for all } i\in \mathbb N.\nonumber \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \varphi_i &=a^{-1}b^{-1} \lambda q(q^i- q^{-i})(\lambda^{-1}q^{i-1}-\lambda q^{1-i})\\&\qquad \times \, (q^{-i}- abc\lambda^{-1}q^{i-1})(q^{-i} - abc^{-1}\lambda^{-1}q^{i-1})\qquad \text{for all } i\in \mathbb N.\nonumber \end{align} $$

-

(ii) The elements

$\alpha ,\beta ,\gamma $

act on

$\alpha ,\beta ,\gamma $

act on

$M_\lambda (a,b,c)$

as scalar multiplication by (1.12)

$M_\lambda (a,b,c)$

as scalar multiplication by (1.12) $$ \begin{align} (b+b^{-1})(c+c^{-1}) +(a+a^{-1})(\lambda q+\lambda^{-1} q^{-1}), \end{align} $$

(1.13)

$$ \begin{align} (b+b^{-1})(c+c^{-1}) +(a+a^{-1})(\lambda q+\lambda^{-1} q^{-1}), \end{align} $$

(1.13) $$ \begin{align} (c+c^{-1})(a+a^{-1})+(b+b^{-1})(\lambda q+\lambda^{-1} q^{-1}), \end{align} $$

(1.14)respectively.

$$ \begin{align} (c+c^{-1})(a+a^{-1})+(b+b^{-1})(\lambda q+\lambda^{-1} q^{-1}), \end{align} $$

(1.14)respectively. $$ \begin{align} (a+a^{-1})(b+b^{-1})+(c+c^{-1})(\lambda q+\lambda^{-1} q^{-1}), \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} (a+a^{-1})(b+b^{-1})+(c+c^{-1})(\lambda q+\lambda^{-1} q^{-1}), \end{align} $$

By Theorem 1.5(i), the

![]() $\triangle _q$

-module

$\triangle _q$

-module

![]() $M_\lambda (a,b,c)$

has the marginal weight

$M_\lambda (a,b,c)$

has the marginal weight

![]() $b\lambda ^{-1}$

. In 2009, the present author conceived the initial idea for creating

$b\lambda ^{-1}$

. In 2009, the present author conceived the initial idea for creating

![]() $M_\lambda (a,b,c)$

during his work [Reference Huang15] on Leonard triples of q-Racah type. These Leonard triples provide a family of finite-dimensional irreducible

$M_\lambda (a,b,c)$

during his work [Reference Huang15] on Leonard triples of q-Racah type. These Leonard triples provide a family of finite-dimensional irreducible

![]() $\triangle _q$

-modules. In the 2015 paper [Reference Huang16], the

$\triangle _q$

-modules. In the 2015 paper [Reference Huang16], the

![]() $\triangle _q$

-module

$\triangle _q$

-module

![]() $M_\lambda (a,b,c)$

was formally introduced to classify the finite-dimensional irreducible

$M_\lambda (a,b,c)$

was formally introduced to classify the finite-dimensional irreducible

![]() $\triangle _q$

-modules when q is not a root of unity. The

$\triangle _q$

-modules when q is not a root of unity. The

![]() $\triangle _q$

-module

$\triangle _q$

-module

![]() $M_\lambda (a,b,c)$

is called the Verma

$M_\lambda (a,b,c)$

is called the Verma

![]() $\triangle _q$

-module, in analogy with the role Verma modules play in the theory of semisimple Lie algebras.

$\triangle _q$

-module, in analogy with the role Verma modules play in the theory of semisimple Lie algebras.

In this article, we focus on those finite-dimensional irreducible

![]() $\triangle _q$

-modules with marginal weights under the condition that q is a root of unity. Henceforth, we assume that q is a root of unity with order

$\triangle _q$

-modules with marginal weights under the condition that q is a root of unity. Henceforth, we assume that q is a root of unity with order

![]() $d\not =1,2,4$

and set

$d\not =1,2,4$

and set

Note that ![]() is the order of the root of unity

is the order of the root of unity

![]() $q^2$

. Dividing the argument into the cases with and without marginal weights, it was shown that the dimension of every finite-dimensional irreducible

$q^2$

. Dividing the argument into the cases with and without marginal weights, it was shown that the dimension of every finite-dimensional irreducible

![]() $\triangle _q$

-module is less than or equal to

$\triangle _q$

-module is less than or equal to ![]() [Reference Huang21]. In particular, every nonzero

[Reference Huang21]. In particular, every nonzero

![]() $\triangle _q$

-module of dimension less than

$\triangle _q$

-module of dimension less than ![]() has a marginal weight. Please see Lemma 2.3. We will see that all finite-dimensional irreducible

has a marginal weight. Please see Lemma 2.3. We will see that all finite-dimensional irreducible

![]() $\triangle _q$

-modules with marginal weights can still be constructed from the Verma

$\triangle _q$

-modules with marginal weights can still be constructed from the Verma

![]() $\triangle _q$

-modules up to isomorphism.

$\triangle _q$

-modules up to isomorphism.

There are two natural families of finite-dimensional quotients of Verma

![]() $\triangle _q$

-modules. One of the two families was first released in [Reference Huang16, §4] and the description is as follows: Pick a triple

$\triangle _q$

-modules. One of the two families was first released in [Reference Huang16, §4] and the description is as follows: Pick a triple

![]() $(a,b,c)\in {\mathbb F^\times }^3$

and any

$(a,b,c)\in {\mathbb F^\times }^3$

and any

![]() $n\in \mathbb N$

. Set the parameter

$n\in \mathbb N$

. Set the parameter

![]() $\lambda =q^n$

. Let

$\lambda =q^n$

. Let

![]() $N_\lambda (a,b,c)$

denote the subspace of

$N_\lambda (a,b,c)$

denote the subspace of

![]() $M_\lambda (a,b,c)$

spanned by

$M_\lambda (a,b,c)$

spanned by

![]() $\{m_i\}_{i=n+1}^\infty $

. By construction,

$\{m_i\}_{i=n+1}^\infty $

. By construction,

![]() $N_\lambda (a,b,c)$

is invariant under A. By (1.11), the scalar

$N_\lambda (a,b,c)$

is invariant under A. By (1.11), the scalar

![]() $\varphi _{n+1}=0$

. Combined with Theorem 1.5(i), this implies that

$\varphi _{n+1}=0$

. Combined with Theorem 1.5(i), this implies that

![]() $N_\lambda (a,b,c)$

is invariant under B. By Theorem 1.5(ii), the elements

$N_\lambda (a,b,c)$

is invariant under B. By Theorem 1.5(ii), the elements

![]() $\alpha ,\beta ,\gamma $

act on

$\alpha ,\beta ,\gamma $

act on

![]() $N_\lambda (a,b,c)$

as scalar multiplication. Thus

$N_\lambda (a,b,c)$

as scalar multiplication. Thus

![]() $N_\lambda (a,b,c)$

is a

$N_\lambda (a,b,c)$

is a

![]() $\triangle _q$

-submodule of

$\triangle _q$

-submodule of

![]() $M_\lambda (a,b,c)$

by Proposition 1.2. Moreover,

$M_\lambda (a,b,c)$

by Proposition 1.2. Moreover,

![]() $N_\lambda (a,b,c)$

is the

$N_\lambda (a,b,c)$

is the

![]() $\triangle _q$

-submodule of

$\triangle _q$

-submodule of

![]() $M_\lambda (a,b,c)$

generated by

$M_\lambda (a,b,c)$

generated by

![]() $m_{n+1}$

. Therefore,

$m_{n+1}$

. Therefore,

is an

![]() $(n+1)$

-dimensional

$(n+1)$

-dimensional

![]() $\triangle _q$

-module that has the basis

$\triangle _q$

-module that has the basis

In this article, we will prove that all irreducible

![]() $\triangle _q$

-modules with dimensions less than

$\triangle _q$

-modules with dimensions less than ![]() are contained in the first family of finite-dimensional quotients of Verma

are contained in the first family of finite-dimensional quotients of Verma

![]() $\triangle _q$

-modules up to isomorphism:

$\triangle _q$

-modules up to isomorphism:

Theorem 1.6. Suppose that V is an irreducible

![]() $\triangle _q$

-module of dimension less than

$\triangle _q$

-module of dimension less than ![]() . Then there exist a triple

. Then there exist a triple

![]() $(a,b,c)\in {\mathbb F^\times }^3$

and an integer n with

$(a,b,c)\in {\mathbb F^\times }^3$

and an integer n with ![]() such that V is isomorphic to the

such that V is isomorphic to the

![]() $\triangle _q$

-module

$\triangle _q$

-module

![]() $V_n(a,b,c)$

.

$V_n(a,b,c)$

.

Let

![]() $\{\pm 1\}$

denote the multiplicative group consisting of the integers

$\{\pm 1\}$

denote the multiplicative group consisting of the integers

![]() $1$

and

$1$

and

![]() $-1$

. There exists a unique left

$-1$

. There exists a unique left

![]() $\{\pm 1\}^3$

-action on

$\{\pm 1\}^3$

-action on

![]() ${\mathbb F^{\times }}^3$

given by

${\mathbb F^{\times }}^3$

given by

$$ \begin{align*} (-1,1,1)\cdot (a,b,c)&=(a^{-1},b,c), \\ (1,-1,1)\cdot (a,b,c)&=(a,b^{-1},c), \\ (1,1,-1)\cdot (a,b,c)&=(a,b,c^{-1}) \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} (-1,1,1)\cdot (a,b,c)&=(a^{-1},b,c), \\ (1,-1,1)\cdot (a,b,c)&=(a,b^{-1},c), \\ (1,1,-1)\cdot (a,b,c)&=(a,b,c^{-1}) \end{align*} $$

for all

![]() $(a,b,c)\in {\mathbb F^{\times }}^3$

. An irreducibility criterion for

$(a,b,c)\in {\mathbb F^{\times }}^3$

. An irreducibility criterion for

![]() $V_n(a,b,c)$

can be expressed in terms of the

$V_n(a,b,c)$

can be expressed in terms of the

![]() $\{\pm 1\}^3$

-action on

$\{\pm 1\}^3$

-action on

![]() ${\mathbb F^{\times }}^3$

:

${\mathbb F^{\times }}^3$

:

Theorem 1.7. For any triple

![]() $(a,b,c)\in {\mathbb F^\times }^3$

and any integer n with

$(a,b,c)\in {\mathbb F^\times }^3$

and any integer n with ![]() , the following conditions are equivalent:

, the following conditions are equivalent:

-

(i) The

$\triangle _q$

-module

$\triangle _q$

-module

$V_n(a,b,c)$

is irreducible.

$V_n(a,b,c)$

is irreducible. -

(ii)

$\bar {a}\bar {b}\bar {c}\not \in \{q^{n-2i+1}\,|\,i=1,2,\ldots ,n\}$

for all

$\bar {a}\bar {b}\bar {c}\not \in \{q^{n-2i+1}\,|\,i=1,2,\ldots ,n\}$

for all

$(\bar {a},\bar {b},\bar {c})\in \{\pm 1\}^3\cdot (a,b,c)$

.

$(\bar {a},\bar {b},\bar {c})\in \{\pm 1\}^3\cdot (a,b,c)$

.

Proof. The proof is similar to that of [Reference Huang16, Theorem 4.4].

Fix an integer n with ![]() . Define

. Define

![]() $\mathbf I_n$

as the set of all isomorphism classes of

$\mathbf I_n$

as the set of all isomorphism classes of

![]() $(n+1)$

-dimensional irreducible

$(n+1)$

-dimensional irreducible

![]() $\triangle _q$

-modules. Define

$\triangle _q$

-modules. Define

![]() $\mathbf P_n$

to be the set of all triples

$\mathbf P_n$

to be the set of all triples

![]() $(a,b,c)\in {\mathbb F^\times }^3$

satisfying Theorem 1.7(i), (ii). Clearly,

$(a,b,c)\in {\mathbb F^\times }^3$

satisfying Theorem 1.7(i), (ii). Clearly,

![]() $\mathbf P_n$

is closed under the

$\mathbf P_n$

is closed under the

![]() $\{\pm 1\}^3$

-action on

$\{\pm 1\}^3$

-action on

![]() ${\mathbb F^{\times }}^3$

. By analogy with the case where q is not a root of unity, Theorems 1.6 and 1.7 result in a classification of all irreducible

${\mathbb F^{\times }}^3$

. By analogy with the case where q is not a root of unity, Theorems 1.6 and 1.7 result in a classification of all irreducible

![]() $\triangle _q$

-modules of dimensions less than

$\triangle _q$

-modules of dimensions less than ![]() :

:

Theorem 1.8. For any integer n with ![]() , there is a bijection

, there is a bijection

![]() $\{\pm 1\}^3 \backslash \mathbf P_n\to \mathbf I_n$

given by

$\{\pm 1\}^3 \backslash \mathbf P_n\to \mathbf I_n$

given by

for all

![]() $(a,b,c)\in \mathbf P_n$

.

$(a,b,c)\in \mathbf P_n$

.

Proof. The proof is similar to that of [Reference Huang16, Theorem 4.7].

We now turn to the second family of finite-dimensional quotients of Verma

![]() $\triangle _q$

-modules. Pick any quadruple

$\triangle _q$

-modules. Pick any quadruple

![]() $(a,b,c,\lambda )\in {\mathbb F^\times }^4$

. Since

$(a,b,c,\lambda )\in {\mathbb F^\times }^4$

. Since ![]() , the parameters (1.9)–(1.11) satisfy the cyclic properties:

, the parameters (1.9)–(1.11) satisfy the cyclic properties:

Let

![]() $\delta \in \mathbb F$

denote an additional parameter. Define

$\delta \in \mathbb F$

denote an additional parameter. Define

![]() $O_{\lambda }^\delta (a,b,c)$

to be the subspace of

$O_{\lambda }^\delta (a,b,c)$

to be the subspace of

![]() $M_\lambda (a,b,c)$

spanned by

$M_\lambda (a,b,c)$

spanned by ![]() . Applying Theorem 1.5(i) along with the cyclic properties, it is routine to verify that

. Applying Theorem 1.5(i) along with the cyclic properties, it is routine to verify that

![]() $O_\lambda ^\delta (a,b,c)$

is invariant under A and B. By Theorem 1.5(ii), the elements

$O_\lambda ^\delta (a,b,c)$

is invariant under A and B. By Theorem 1.5(ii), the elements

![]() $\alpha ,\beta ,\gamma $

act on

$\alpha ,\beta ,\gamma $

act on

![]() $O_\lambda ^\delta (a,b,c)$

as scalar multiplication. Thus

$O_\lambda ^\delta (a,b,c)$

as scalar multiplication. Thus

![]() $O_\lambda ^\delta (a,b,c)$

is a

$O_\lambda ^\delta (a,b,c)$

is a

![]() $\triangle _q$

-submodule of

$\triangle _q$

-submodule of

![]() $M_\lambda (a,b,c)$

by Proposition 1.2. Moreover,

$M_\lambda (a,b,c)$

by Proposition 1.2. Moreover,

![]() $O_\lambda ^\delta (a,b,c)$

is the

$O_\lambda ^\delta (a,b,c)$

is the

![]() $\triangle _q$

-submodule of

$\triangle _q$

-submodule of

![]() $M_\lambda (a,b,c)$

generated by

$M_\lambda (a,b,c)$

generated by ![]() . Therefore,

. Therefore,

is a ![]() -dimensional

-dimensional

![]() $\triangle _q$

-module that has the basis

$\triangle _q$

-module that has the basis

In this article, we will prove that all ![]() -dimensional irreducible

-dimensional irreducible

![]() $\triangle _q$

-modules with marginal weights are contained in this second family up to isomorphism:

$\triangle _q$

-modules with marginal weights are contained in this second family up to isomorphism:

Theorem 1.9. Suppose that V is a ![]() -dimensional irreducible

-dimensional irreducible

![]() $\triangle _q$

-module with marginal weights. Then there exists a quintuple

$\triangle _q$

-module with marginal weights. Then there exists a quintuple

![]() $(a,b,c,\lambda ,\delta )\in {\mathbb F^\times }^4\times \mathbb F$

such that V is isomorphic to the

$(a,b,c,\lambda ,\delta )\in {\mathbb F^\times }^4\times \mathbb F$

such that V is isomorphic to the

![]() $\triangle _q$

-module

$\triangle _q$

-module

![]() $W_{\lambda }^\delta (a,b,c)$

.

$W_{\lambda }^\delta (a,b,c)$

.

There is a unique left

![]() $\{\pm 1\}$

-action on

$\{\pm 1\}$

-action on

![]() ${\mathbb F^{\times }}^4$

given by

${\mathbb F^{\times }}^4$

given by

for all

![]() $(a,b,c,\lambda )\in {\mathbb F^{\times }}^4$

. Recall that the symmetric group

$(a,b,c,\lambda )\in {\mathbb F^{\times }}^4$

. Recall that the symmetric group

![]() $\mathfrak S_4$

of degree four has a presentation with the transpositions

$\mathfrak S_4$

of degree four has a presentation with the transpositions

![]() $(1\, 2), (2\, 3), (3\, 4)$

subject to the relations

$(1\, 2), (2\, 3), (3\, 4)$

subject to the relations

$$ \begin{align*} (1\, 2)^2=(2\, 3&)^2=(3\, 4)^2=1,\\(1\, 2)(3\, 4)&=(3\, 4)(1\, 2),\\(1\, 2)(2\, 3)(1\, 2)&=(2\, 3)(1\, 2)(2\, 3),\\(2\, 3)(3\, 4)(2\, 3)&=(3\, 4)(2\, 3)(3\, 4). \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} (1\, 2)^2=(2\, 3&)^2=(3\, 4)^2=1,\\(1\, 2)(3\, 4)&=(3\, 4)(1\, 2),\\(1\, 2)(2\, 3)(1\, 2)&=(2\, 3)(1\, 2)(2\, 3),\\(2\, 3)(3\, 4)(2\, 3)&=(3\, 4)(2\, 3)(3\, 4). \end{align*} $$

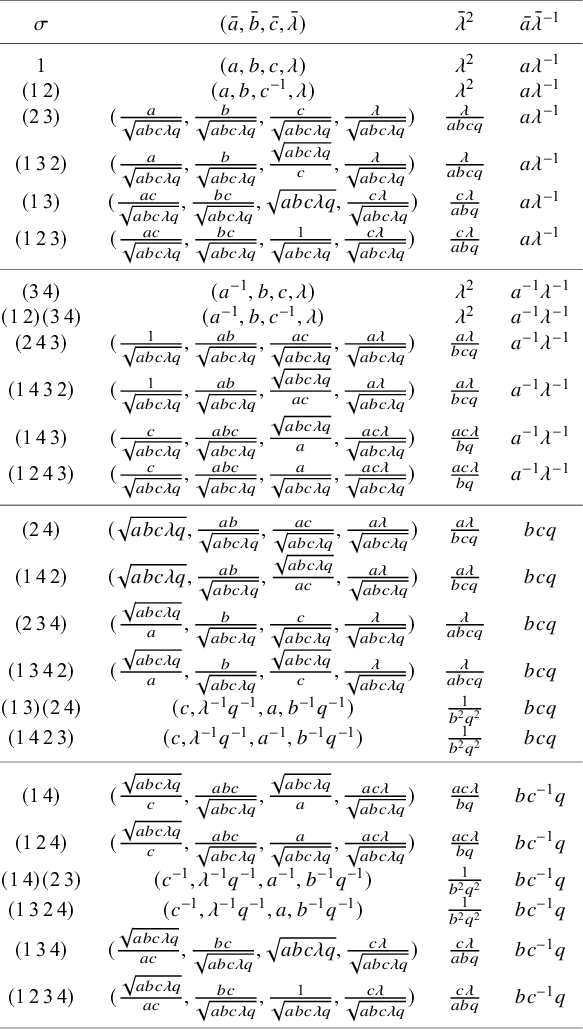

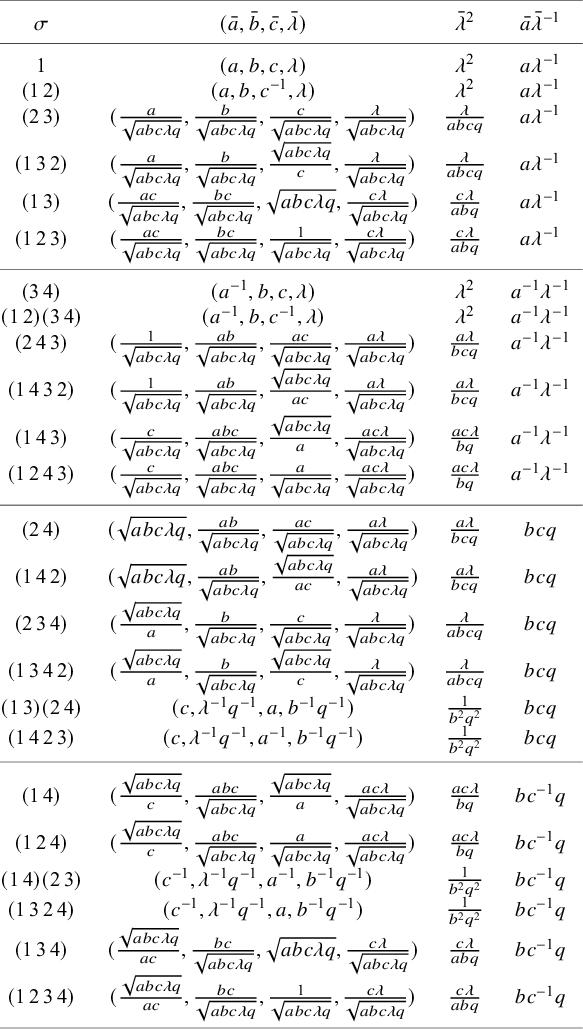

Applying the presentation, it is straightforward to verify that there exists a unique right

![]() $\mathfrak S_4$

-action on

$\mathfrak S_4$

-action on

![]() $\{\pm 1\}\backslash {\mathbb F^{\times }}^4$

given by

$\{\pm 1\}\backslash {\mathbb F^{\times }}^4$

given by

$$ \begin{align*} (\{\pm 1\}\cdot (a,b,c,\lambda))\cdot {(1\, 2)} &= \{\pm 1\}\cdot (a,b,c^{-1},\lambda), \\ (\{\pm 1\}\cdot (a,b,c,\lambda))\cdot {(2\, 3)} &= \{\pm 1\}\cdot \textstyle (\frac{a}{\sqrt{a b c\lambda q}}, \frac{b}{\sqrt{a b c\lambda q}}, \frac{c}{\sqrt{a b c\lambda q}}, \frac{\lambda}{\sqrt{a b c\lambda q}}), \\ (\{\pm 1\}\cdot (a,b,c,\lambda))\cdot {(3\, 4)} &= \{\pm 1\}\cdot (a^{-1},b,c,\lambda) \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} (\{\pm 1\}\cdot (a,b,c,\lambda))\cdot {(1\, 2)} &= \{\pm 1\}\cdot (a,b,c^{-1},\lambda), \\ (\{\pm 1\}\cdot (a,b,c,\lambda))\cdot {(2\, 3)} &= \{\pm 1\}\cdot \textstyle (\frac{a}{\sqrt{a b c\lambda q}}, \frac{b}{\sqrt{a b c\lambda q}}, \frac{c}{\sqrt{a b c\lambda q}}, \frac{\lambda}{\sqrt{a b c\lambda q}}), \\ (\{\pm 1\}\cdot (a,b,c,\lambda))\cdot {(3\, 4)} &= \{\pm 1\}\cdot (a^{-1},b,c,\lambda) \end{align*} $$

for all

![]() $(a,b,c,\lambda )\in {\mathbb F^{\times }}^4$

.

$(a,b,c,\lambda )\in {\mathbb F^{\times }}^4$

.

Definition 1.10.

-

(i) For any

$(a,b,c,\lambda ),(\bar {a},\bar {b},\bar {c},\bar {\lambda })\in {\mathbb F^{\times }}^4$

, we define whenever

$(a,b,c,\lambda ),(\bar {a},\bar {b},\bar {c},\bar {\lambda })\in {\mathbb F^{\times }}^4$

, we define whenever

$(\{\pm 1\}\cdot (a,b,c,\lambda ))\cdot \mathfrak S_4=(\{\pm 1\}\cdot (\bar {a},\bar {b},\bar {c},\bar {\lambda }))\cdot \mathfrak S_4$

in

$(\{\pm 1\}\cdot (a,b,c,\lambda ))\cdot \mathfrak S_4=(\{\pm 1\}\cdot (\bar {a},\bar {b},\bar {c},\bar {\lambda }))\cdot \mathfrak S_4$

in

$(\{\pm 1\}\backslash {\mathbb F^{\times }}^4)/ \mathfrak S_4$

. The binary relation

$(\{\pm 1\}\backslash {\mathbb F^{\times }}^4)/ \mathfrak S_4$

. The binary relation  is an equivalence relation on

is an equivalence relation on

${\mathbb F^{\times }}^4$

.

${\mathbb F^{\times }}^4$

.

-

(ii) For any

$(a,b,c,\lambda ,\delta ),(\bar {a},\bar {b},\bar {c},\bar {\lambda },\bar {\delta })\in {\mathbb F^{\times }}^4\times \mathbb F$

, we define whenever

$(a,b,c,\lambda ,\delta ),(\bar {a},\bar {b},\bar {c},\bar {\lambda },\bar {\delta })\in {\mathbb F^{\times }}^4\times \mathbb F$

, we define whenever

and (1.15)

and (1.15)

The binary relation is an equivalence relation on

${\mathbb F^{\times }}^4\times \mathbb F$

.

${\mathbb F^{\times }}^4\times \mathbb F$

.

An irreducibility criterion for the

![]() $\triangle _q$

-module

$\triangle _q$

-module

![]() $W_\lambda ^\delta (a,b,c)$

can be expressed in terms of the equivalence relation

$W_\lambda ^\delta (a,b,c)$

can be expressed in terms of the equivalence relation ![]() :

:

Theorem 1.11. For any

![]() $(a,b,c,\lambda ,\delta )\in {\mathbb F^\times }^4\times \mathbb F$

, the following conditions are equivalent:

$(a,b,c,\lambda ,\delta )\in {\mathbb F^\times }^4\times \mathbb F$

, the following conditions are equivalent:

-

(i) The

$\triangle _q$

-module

$\triangle _q$

-module

$W_\lambda ^\delta (a,b,c)$

is irreducible.

$W_\lambda ^\delta (a,b,c)$

is irreducible. -

(ii)

$\bar {\delta }\not =0$

or

$\bar {\delta }\not =0$

or  for all

for all  .

.

Define ![]() to be the set of all quintuples

to be the set of all quintuples

![]() $(a,b,c,\lambda ,\delta )\in {\mathbb F^\times }^4\times \mathbb F$

satisfying Theorem 1.11(i), (ii). Let

$(a,b,c,\lambda ,\delta )\in {\mathbb F^\times }^4\times \mathbb F$

satisfying Theorem 1.11(i), (ii). Let ![]() . It can be shown that if

. It can be shown that if ![]() , then the

, then the

![]() $\triangle _q$

-module

$\triangle _q$

-module

![]() $W_\lambda ^\delta (a,b,c)$

is isomorphic to

$W_\lambda ^\delta (a,b,c)$

is isomorphic to

![]() $W_{\bar {\lambda }}^{\bar {\delta }}(\bar {a},\bar {b},\bar {c})$

. Please see Theorem 7.4. However, the converse is not true. Extending the equivalence relation

$W_{\bar {\lambda }}^{\bar {\delta }}(\bar {a},\bar {b},\bar {c})$

. Please see Theorem 7.4. However, the converse is not true. Extending the equivalence relation ![]() by adding the following two additional rules, we will derive a classification of all

by adding the following two additional rules, we will derive a classification of all ![]() -dimensional irreducible

-dimensional irreducible

![]() $\triangle _q$

-modules with marginal weights up to isomorphism.

$\triangle _q$

-modules with marginal weights up to isomorphism.

Definition 1.12. For any

![]() $ (a,b,c,\lambda ,\delta ), (\bar {a},\bar {b},\bar {c},\bar {\lambda },\bar {\delta }) \in {\mathbb F^{\times }}^4\times \mathbb F$

, we declare

$ (a,b,c,\lambda ,\delta ), (\bar {a},\bar {b},\bar {c},\bar {\lambda },\bar {\delta }) \in {\mathbb F^{\times }}^4\times \mathbb F$

, we declare

![]() $ (a,b,c,\lambda ,\delta ) \sim (\bar {a},\bar {b},\bar {c},\bar {\lambda },\bar {\delta }) $

whenever any of the following conditions holds:

$ (a,b,c,\lambda ,\delta ) \sim (\bar {a},\bar {b},\bar {c},\bar {\lambda },\bar {\delta }) $

whenever any of the following conditions holds:

-

(i)

.

. -

(ii)

$(\bar {a},\bar {b},\bar {c},\bar {\lambda },\bar {\delta })=(a^{-1},b,c,\lambda ^{-1}q^{-2},\delta )$

and

$(\bar {a},\bar {b},\bar {c},\bar {\lambda },\bar {\delta })=(a^{-1},b,c,\lambda ^{-1}q^{-2},\delta )$

and  .

. -

(iii)

$ (\bar {a},\bar {b},\bar {c},\bar {\lambda },\bar {\delta }) = (a^{-1},b^{-1},c,\lambda ^{-1}q^{-2},\delta )$

and the following conditions hold:

$ (\bar {a},\bar {b},\bar {c},\bar {\lambda },\bar {\delta }) = (a^{-1},b^{-1},c,\lambda ^{-1}q^{-2},\delta )$

and the following conditions hold:-

(a)

.

. -

(b)

.

.

-

Definition 1.13. Define

![]() $\simeq $

to be the equivalence relation on

$\simeq $

to be the equivalence relation on

![]() ${\mathbb F^\times }^4\times \mathbb F$

generated by

${\mathbb F^\times }^4\times \mathbb F$

generated by

![]() $\sim $

.

$\sim $

.

It can be shown that ![]() is closed under

is closed under

![]() $\simeq $

. Please see Lemma 10.3. Let

$\simeq $

. Please see Lemma 10.3. Let ![]() denote the set of all equivalence classes of

denote the set of all equivalence classes of ![]() under

under

![]() $\simeq $

. Define

$\simeq $

. Define ![]() as the set of the isomorphism classes of all

as the set of the isomorphism classes of all ![]() -dimensional irreducible

-dimensional irreducible

![]() $\triangle _q$

-modules with marginal weights.

$\triangle _q$

-modules with marginal weights.

Theorem 1.14. There is a bijection from ![]() to

to ![]() given by

given by

for all ![]() .

.

The outline of this article is as follows: In Section 2, we recall some properties of marginal weights and their closely related vectors called marginal weight vectors. In Section 3, we reinterpret the universal property of

![]() $M_\lambda (a,b,c)$

and relate the property to a functional relation called the feasible relation. In Section 4, we give a proof of Theorem 1.6. In Section 5, we establish a polynomial characterization for the feasible relation; consequently, the feasible relation can be expressed in terms of the equivalence relation

$M_\lambda (a,b,c)$

and relate the property to a functional relation called the feasible relation. In Section 4, we give a proof of Theorem 1.6. In Section 5, we establish a polynomial characterization for the feasible relation; consequently, the feasible relation can be expressed in terms of the equivalence relation ![]() . In Section 6, we give a proof of Theorem 1.9. In Section 7, we characterize the equivalence relations

. In Section 6, we give a proof of Theorem 1.9. In Section 7, we characterize the equivalence relations ![]() and

and ![]() in terms of the

in terms of the

![]() $\triangle _q$

-modules

$\triangle _q$

-modules

![]() $M_\lambda (a,b,c)$

and

$M_\lambda (a,b,c)$

and

![]() $W_\lambda ^\delta (a,b,c)$

. In Section 8, we give a proof of Theorem 1.11. In Section 9, we relate the binary relation

$W_\lambda ^\delta (a,b,c)$

. In Section 8, we give a proof of Theorem 1.11. In Section 9, we relate the binary relation

![]() $\sim $

to the marginal weight vectors of

$\sim $

to the marginal weight vectors of

![]() $W_\lambda ^\delta (a,b,c)$

. In Section 10, we give a proof of Theorem 1.14. In addition, the

$W_\lambda ^\delta (a,b,c)$

. In Section 10, we give a proof of Theorem 1.14. In addition, the

![]() $\mathfrak S_4$

-action on

$\mathfrak S_4$

-action on

![]() $\{\pm 1\}\backslash {\mathbb F^{\times }}^4$

is fully displayed in Appendix A.

$\{\pm 1\}\backslash {\mathbb F^{\times }}^4$

is fully displayed in Appendix A.

2. The marginal weights and the marginal weight vectors

Recall the marginal weights of

![]() $\triangle _q$

-modules from Definition 1.4.

$\triangle _q$

-modules from Definition 1.4.

Theorem 2.1 [Reference Huang21, Theorem 6.10]

The dimension of any finite-dimensional irreducible

![]() $\triangle _q$

-module without marginal weights is equal to

$\triangle _q$

-module without marginal weights is equal to ![]() .

.

Lemma 2.2. Let V denote a

![]() $\triangle _q$

-module and W denote a

$\triangle _q$

-module and W denote a

![]() $\triangle _q$

-submodule of V. For any

$\triangle _q$

-submodule of V. For any

![]() $\mu \in \mathbb F^\times $

, the following statements are true:

$\mu \in \mathbb F^\times $

, the following statements are true:

-

(i)

$W(\mu )=W\cap V(\mu )$

.

$W(\mu )=W\cap V(\mu )$

. -

(ii) If

$\mu $

is a weight of W, then

$\mu $

is a weight of W, then

$\mu $

is a weight of V.

$\mu $

is a weight of V. -

(iii) If

$\mu $

is a marginal weight of W, then

$\mu $

is a marginal weight of W, then

$\mu $

is a marginal weight of V.

$\mu $

is a marginal weight of V.

Proof.

Lemma 2.3. Every nonzero

![]() $\triangle _q$

-module of dimension less than

$\triangle _q$

-module of dimension less than ![]() has marginal weights.

has marginal weights.

Proof. Let V denote a nonzero

![]() $\triangle _q$

-module of dimension less than

$\triangle _q$

-module of dimension less than ![]() . Then V contains an irreducible

. Then V contains an irreducible

![]() $\triangle _q$

-submodule W. Since

$\triangle _q$

-submodule W. Since ![]() , the

, the

![]() $\triangle _q$

-module W has a marginal weight by Theorem 2.1. The lemma is now immediate from Lemma 2.2(iii).

$\triangle _q$

-module W has a marginal weight by Theorem 2.1. The lemma is now immediate from Lemma 2.2(iii).

Definition 2.4. Let

![]() $\mu $

denote a weight of a

$\mu $

denote a weight of a

![]() $\triangle _q$

-module V. A weight vector v of V with weight

$\triangle _q$

-module V. A weight vector v of V with weight

![]() $\mu $

is said to be marginal whenever v is an eigenvector of

$\mu $

is said to be marginal whenever v is an eigenvector of

By Definitions 1.4 and 2.4, if a

![]() $\triangle _q$

-module V contains a marginal weight vector with weight

$\triangle _q$

-module V contains a marginal weight vector with weight

![]() $\mu $

, then

$\mu $

, then

![]() $\mu $

is a marginal weight of V.

$\mu $

is a marginal weight of V.

Lemma 2.5 [Reference Huang21, Lemma 6.1]

Assume that V is a finite-dimensional irreducible

![]() $\triangle _q$

-module. For any weight

$\triangle _q$

-module. For any weight

![]() $\mu $

of V, the following conditions are equivalent:

$\mu $

of V, the following conditions are equivalent:

-

(i)

$\mu $

is a marginal weight of V.

$\mu $

is a marginal weight of V. -

(ii) There exists a marginal weight vector of V with weight

$\mu $

.

$\mu $

.

Lemma 2.6. Assume that a finite-dimensional irreducible

![]() $\triangle _q$

-module V contains a marginal weight vector v with weight

$\triangle _q$

-module V contains a marginal weight vector v with weight

![]() $\mu $

. For all

$\mu $

. For all

![]() $i\in \mathbb N$

, the following statements hold:

$i\in \mathbb N$

, the following statements hold:

-

(i)

$ (B-\mu q^{2i}-\mu ^{-1} q^{-2i})A^i v $

is a linear combination of

$ (B-\mu q^{2i}-\mu ^{-1} q^{-2i})A^i v $

is a linear combination of

$v, Av,\ldots , A^{i-1} v$

.

$v, Av,\ldots , A^{i-1} v$

. -

(ii)

$ \prod \limits _{h=0}^i (B-\mu q^{2h}-\mu ^{-1} q^{-2h}) $

vanishes at

$ \prod \limits _{h=0}^i (B-\mu q^{2h}-\mu ^{-1} q^{-2h}) $

vanishes at

$v, Av,\ldots , A^i v$

.

$v, Av,\ldots , A^i v$

.

Proof.

-

(i): Immediate from [Reference Huang21, Lemma 6.2].

-

(ii): By Lemma 2.6(i), a routine induction on i yields (ii).

Lemma 2.7. If a finite-dimensional irreducible

![]() $\triangle _q$

-module V contains a marginal weight vector v, then the vectors

$\triangle _q$

-module V contains a marginal weight vector v, then the vectors

![]() $\{A^i v\}_{i=0}^{\dim V-1}$

are a basis for V.

$\{A^i v\}_{i=0}^{\dim V-1}$

are a basis for V.

Proof. Let W denote the subspace of V spanned by

![]() $\{A^i v\}_{i\in \mathbb N}$

. Then W is A-invariant and the vectors

$\{A^i v\}_{i\in \mathbb N}$

. Then W is A-invariant and the vectors

![]() $\{A^i v\}_{i=0}^{\dim W-1}$

are a basis for W. By Lemma 2.6(i), W is B-invariant. By Schur’s lemma, the central elements

$\{A^i v\}_{i=0}^{\dim W-1}$

are a basis for W. By Lemma 2.6(i), W is B-invariant. By Schur’s lemma, the central elements

![]() $\alpha ,\beta ,\gamma $

act on V, as well as W, as scalar multiplication. Hence W is a

$\alpha ,\beta ,\gamma $

act on V, as well as W, as scalar multiplication. Hence W is a

![]() $\triangle _q$

-submodule of V by Proposition 1.2. Since

$\triangle _q$

-submodule of V by Proposition 1.2. Since

![]() $v\in W$

and

$v\in W$

and

![]() $v\not =0$

, it follows that

$v\not =0$

, it follows that

![]() $W=V$

. The lemma follows.

$W=V$

. The lemma follows.

3. The universal property of

$M_\lambda (a,b,c)$

and the feasible relation

$M_\lambda (a,b,c)$

and the feasible relation

For the sake of brevity, the following notational agreements will be used throughout the rest of this article. Whenever the quadruple

![]() $(a,b,c,\lambda )$

is used to represent an element of

$(a,b,c,\lambda )$

is used to represent an element of

![]() ${\mathbb F^\times }^4$

, the notation

${\mathbb F^\times }^4$

, the notation

![]() $\{m_i\}_{i\in \mathbb N}$

denotes the basis for

$\{m_i\}_{i\in \mathbb N}$

denotes the basis for

![]() $M_\lambda (a,b,c)$

mentioned in Theorem 1.5(i) and

$M_\lambda (a,b,c)$

mentioned in Theorem 1.5(i) and

![]() $\{\theta _i\}_{i\in \mathbb N}$

,

$\{\theta _i\}_{i\in \mathbb N}$

,

![]() $\{\theta _i^*\}_{i\in \mathbb N}$

,

$\{\theta _i^*\}_{i\in \mathbb N}$

,

![]() $\{\varphi _i\}_{i\in \mathbb N}$

stand for the accompanying parameters (1.9)–(1.11).

$\{\varphi _i\}_{i\in \mathbb N}$

stand for the accompanying parameters (1.9)–(1.11).

We begin this section with a simplified description of [Reference Huang16, Proposition 3.2], which is called the universal property of the Verma

![]() $\triangle _q$

-module

$\triangle _q$

-module

![]() $M_\lambda (a,b,c)$

.

$M_\lambda (a,b,c)$

.

Proposition 3.1. Let

![]() $(a,b,c,\lambda )\in {\mathbb F^\times }^4$

be given. For any

$(a,b,c,\lambda )\in {\mathbb F^\times }^4$

be given. For any

![]() $\triangle _q$

-module V and

$\triangle _q$

-module V and

![]() $v\in V$

, the following conditions are equivalent:

$v\in V$

, the following conditions are equivalent:

-

(i) There exists a

$\triangle _q$

-module homomorphism

$\triangle _q$

-module homomorphism

$ M_\lambda (a,b,c)\to V $

that sends

$ M_\lambda (a,b,c)\to V $

that sends

$m_0$

to v.

$m_0$

to v. -

(ii) The following equations hold on V:

(3.1) $$ \begin{align} B v&=\theta_0^* v, \end{align} $$

(3.2)

$$ \begin{align} B v&=\theta_0^* v, \end{align} $$

(3.2) $$ \begin{align} (B-\theta_1^*)A v&=(\theta_0(\theta_0^*-\theta_1^*)+\varphi_1) v, \end{align} $$

(3.3)

$$ \begin{align} (B-\theta_1^*)A v&=(\theta_0(\theta_0^*-\theta_1^*)+\varphi_1) v, \end{align} $$

(3.3) $$ \begin{align} \beta v&=\omega^* v, \end{align} $$

(3.4)where

$$ \begin{align} \beta v&=\omega^* v, \end{align} $$

(3.4)where $$ \begin{align} \gamma v&=\omega^\varepsilon v, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \gamma v&=\omega^\varepsilon v, \end{align} $$

$\omega ^*$

and

$\omega ^*$

and

$\omega ^\varepsilon $

are the scalars (1.13) and (1.14), respectively.

$\omega ^\varepsilon $

are the scalars (1.13) and (1.14), respectively.

Proof. By Theorem 1.5, condition (i) implies (3.1), (3.3), (3.4) and the following equations:

where

![]() $\omega $

is the scalar (1.12). By [Reference Huang16, Proposition 3.2], equations (3.1) and (3.3)–(3.6) imply condition (i). Observe that (3.2) is identical to (3.5) when (3.1) holds. Applying both sides of (1.5) to v and evaluating the resulting equation using (3.1), (3.2), and (3.4), we obtain equation (3.6). Therefore (3.1)–(3.4) hold if and only if (3.1) and (3.3)–(3.6) hold. The proposition follows.

$\omega $

is the scalar (1.12). By [Reference Huang16, Proposition 3.2], equations (3.1) and (3.3)–(3.6) imply condition (i). Observe that (3.2) is identical to (3.5) when (3.1) holds. Applying both sides of (1.5) to v and evaluating the resulting equation using (3.1), (3.2), and (3.4), we obtain equation (3.6). Therefore (3.1)–(3.4) hold if and only if (3.1) and (3.3)–(3.6) hold. The proposition follows.

Since the

![]() $\triangle _q$

-module

$\triangle _q$

-module

![]() $M_\lambda (a,b,c)$

is generated by

$M_\lambda (a,b,c)$

is generated by

![]() $m_0$

, if Proposition 3.1(i) holds then the mentioned map is unique. The coefficient of v on the right-hand side of (3.2) is equal to

$m_0$

, if Proposition 3.1(i) holds then the mentioned map is unique. The coefficient of v on the right-hand side of (3.2) is equal to

![]() $q-q^{-1}$

times

$q-q^{-1}$

times

Inspired by Proposition 3.1, we study the following functional relation:

Definition 3.2. For any

![]() $(a,b,c,\lambda )\in \mathbb F^{\times 4}$

and any

$(a,b,c,\lambda )\in \mathbb F^{\times 4}$

and any

![]() $(\mu ,\varphi ,\omega ^*,\omega ^\varepsilon )\in \mathbb F^\times \times \mathbb F^3$

, we say that

$(\mu ,\varphi ,\omega ^*,\omega ^\varepsilon )\in \mathbb F^\times \times \mathbb F^3$

, we say that

![]() $(a,b,c,\lambda )$

is feasible for

$(a,b,c,\lambda )$

is feasible for

![]() $(\mu ,\varphi ,\omega ^*,\omega ^\varepsilon )$

whenever the following equations hold:

$(\mu ,\varphi ,\omega ^*,\omega ^\varepsilon )$

whenever the following equations hold:

-

(i)

$\mu =b\lambda ^{-1}$

.

$\mu =b\lambda ^{-1}$

. -

(ii)

$\varphi = (c+c^{-1})(\lambda -\lambda ^{-1})-(a+a^{-1})(b q-b^{-1} q^{-1})$

.

$\varphi = (c+c^{-1})(\lambda -\lambda ^{-1})-(a+a^{-1})(b q-b^{-1} q^{-1})$

. -

(iii)

$\omega ^{*}= (c+c^{-1})(a+a^{-1})+(b+b^{-1})(\lambda q+\lambda ^{-1} q^{-1})$

.

$\omega ^{*}= (c+c^{-1})(a+a^{-1})+(b+b^{-1})(\lambda q+\lambda ^{-1} q^{-1})$

. -

(iv)

$\omega ^{\varepsilon }=(a+a^{-1})(b+b^{-1})+(c+c^{-1})(\lambda q+\lambda ^{-1} q^{-1})$

.

$\omega ^{\varepsilon }=(a+a^{-1})(b+b^{-1})+(c+c^{-1})(\lambda q+\lambda ^{-1} q^{-1})$

.

Theorem 3.3. Let

![]() $(a,b,c,\lambda )\in \mathbb F^{\times 4}$

and

$(a,b,c,\lambda )\in \mathbb F^{\times 4}$

and

![]() $(\mu ,\varphi ,\omega ^*,\omega ^\varepsilon )\in \mathbb F^\times \times \mathbb F^3$

be given. Suppose that a

$(\mu ,\varphi ,\omega ^*,\omega ^\varepsilon )\in \mathbb F^\times \times \mathbb F^3$

be given. Suppose that a

![]() $\triangle _q$

-module V contains a nonzero vector v satisfying the following equations:

$\triangle _q$

-module V contains a nonzero vector v satisfying the following equations:

Then

![]() $(a,b,c,\lambda )$

is feasible for

$(a,b,c,\lambda )$

is feasible for

![]() $(\mu ,\varphi ,\omega ^*,\omega ^\varepsilon )$

if and only if the following conditions hold:

$(\mu ,\varphi ,\omega ^*,\omega ^\varepsilon )$

if and only if the following conditions hold:

-

(i)

$\mu =b\lambda ^{-1}$

.

$\mu =b\lambda ^{-1}$

. -

(ii) There exists a

$\triangle _q$

-module homomorphism

$\triangle _q$

-module homomorphism

$ M_\lambda (a,b,c)\to V $

that sends

$ M_\lambda (a,b,c)\to V $

that sends

$m_0$

to v.

$m_0$

to v.

Proof. Statement (i) is exactly Definition 3.2(i).

(

![]() $\Rightarrow $

): Statement (ii) is immediate from Proposition 3.1 and Definition 3.2.

$\Rightarrow $

): Statement (ii) is immediate from Proposition 3.1 and Definition 3.2.

(

![]() $\Leftarrow $

): Since (ii) holds, it follows from Proposition 3.1 that equations 3.1–3.4 hold. By (i), the scalar

$\Leftarrow $

): Since (ii) holds, it follows from Proposition 3.1 that equations 3.1–3.4 hold. By (i), the scalar

![]() $\theta _1^*$

is equal to

$\theta _1^*$

is equal to

![]() $\mu q^2+\mu ^{-1}q^{-2}$

. Since

$\mu q^2+\mu ^{-1}q^{-2}$

. Since

![]() $v\not =0$

, comparing (3.2) with (3.8) yields Definition 3.2(ii). For similar reasons, Definition 3.2(iii) and (iv) follow. Therefore

$v\not =0$

, comparing (3.2) with (3.8) yields Definition 3.2(ii). For similar reasons, Definition 3.2(iii) and (iv) follow. Therefore

![]() $(a,b,c,\lambda )$

is feasible for

$(a,b,c,\lambda )$

is feasible for

![]() $(\mu ,\varphi ,\omega ^*,\omega ^\varepsilon )$

.

$(\mu ,\varphi ,\omega ^*,\omega ^\varepsilon )$

.

We end this section with the following lemmas related to Theorem 3.3:

Lemma 3.4. Suppose that V is a finite-dimensional irreducible

![]() $\triangle _q$

-module with a marginal weight

$\triangle _q$

-module with a marginal weight

![]() $\mu $

. Then there exist a nonzero vector

$\mu $

. Then there exist a nonzero vector

![]() $v\in V$

and three scalars

$v\in V$

and three scalars

![]() $\varphi ,\omega ^*,\omega ^\varepsilon \in \mathbb F$

satisfying equations (3.7)–(3.10).

$\varphi ,\omega ^*,\omega ^\varepsilon \in \mathbb F$

satisfying equations (3.7)–(3.10).

Proof. By Lemma 2.5, there exists a marginal weight vector v of V with weight

![]() $\mu $

. Hence (3.7) follows. By Definition 2.4 and since

$\mu $

. Hence (3.7) follows. By Definition 2.4 and since

![]() $q^2\not =1$

, there is a scalar

$q^2\not =1$

, there is a scalar

![]() $\varphi \in \mathbb F$

such that (3.8) holds. By Schur’s lemma, there are

$\varphi \in \mathbb F$

such that (3.8) holds. By Schur’s lemma, there are

![]() $\omega ^*,\omega ^\varepsilon \in \mathbb F$

such that (3.9) and (3.10) hold.

$\omega ^*,\omega ^\varepsilon \in \mathbb F$

such that (3.9) and (3.10) hold.

Lemma 3.5. Let

![]() $(a,b,c,\lambda )\in {\mathbb F^\times }^4$

be given. For any

$(a,b,c,\lambda )\in {\mathbb F^\times }^4$

be given. For any

![]() $\triangle _q$

-submodule O of

$\triangle _q$

-submodule O of

![]() $M_\lambda (a,b,c)$

with

$M_\lambda (a,b,c)$

with

![]() $m_0\not \in O$

, the following statements are true:

$m_0\not \in O$

, the following statements are true:

-

(i)

$m_0+O$

is a marginal weight vector of

$m_0+O$

is a marginal weight vector of

$M_\lambda (a,b,c)/O$

with weight

$M_\lambda (a,b,c)/O$

with weight

$b\lambda ^{-1}$

.

$b\lambda ^{-1}$

. -

(ii)

$m_0+O$

is a marginal weight vector of

$m_0+O$

is a marginal weight vector of

$M_\lambda (a,b,c)/O$

with weight

$M_\lambda (a,b,c)/O$

with weight

$b^{-1}\lambda $

if and only if

$b^{-1}\lambda $

if and only if

$b\lambda ^{-1}=b^{-1}\lambda $

or

$b\lambda ^{-1}=b^{-1}\lambda $

or

$m_1+O$

is a scalar multiple of

$m_1+O$

is a scalar multiple of

$m_0+O$

.

$m_0+O$

.

Proof.

-

(i): By Theorem 1.5(i), it is routine to verify statement (i).

-

(ii): By Theorem 1.5(i), a straightforward calculation shows that

$$ \begin{align*} (B-b^{-1}\lambda q^2-b\lambda^{-1}q^{-2}) Am_0= \varphi m_0 + (q^2-q^{-2})(b\lambda^{-1}-b^{-1}\lambda) m_1 \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} (B-b^{-1}\lambda q^2-b\lambda^{-1}q^{-2}) Am_0= \varphi m_0 + (q^2-q^{-2})(b\lambda^{-1}-b^{-1}\lambda) m_1 \end{align*} $$

for some scalar

![]() $\varphi \in \mathbb F$

. Statement (ii) follows from the above equation.

$\varphi \in \mathbb F$

. Statement (ii) follows from the above equation.

4. Proof for Theorem 1.6

Lemma 4.1. There exists a unique algebra automorphism

![]() $\vee $

of

$\vee $

of

![]() $\triangle _q$

that sends

$\triangle _q$

that sends

Proof. It is routine to verify the lemma by using Proposition 1.2.

For any

![]() $\triangle _q$

-module V, the notation

$\triangle _q$

-module V, the notation

stands for the

![]() $\triangle _q$

-module obtained by twisting the

$\triangle _q$

-module obtained by twisting the

![]() $\triangle _q$

-module V via

$\triangle _q$

-module V via

![]() $\vee $

.

$\vee $

.

Lemma 4.2. Let n denote an integer with ![]() . Suppose that

. Suppose that

![]() $\{h_i\}_{i=0}^{n+1}$

is a sequence in

$\{h_i\}_{i=0}^{n+1}$

is a sequence in

![]() $\mathbb F$

satisfying the following conditions:

$\mathbb F$

satisfying the following conditions:

-

(i)

$h_{i+2} -h_{i-1} = (q^2+1+q^{-2})(h_{i+1}-h_i) $

for all

$h_{i+2} -h_{i-1} = (q^2+1+q^{-2})(h_{i+1}-h_i) $

for all

$i=1,2,\ldots ,n-1$

.

$i=1,2,\ldots ,n-1$

. -

(ii) There are three integers

$j,k,\ell $

with

$j,k,\ell $

with

$0\leq j<k<\ell \leq n+1$

such that

$0\leq j<k<\ell \leq n+1$

such that

$h_j=h_k=h_\ell =0$

.

$h_j=h_k=h_\ell =0$

.

Then

![]() $ h_i=0$

for all

$ h_i=0$

for all

![]() $i=0,1,\ldots ,n+1$

.

$i=0,1,\ldots ,n+1$

.

Proof. If

![]() $n=1$

, then the lemma is immediate from (ii). Now suppose that

$n=1$

, then the lemma is immediate from (ii). Now suppose that

![]() $n\geq 2$

. Since

$n\geq 2$

. Since

![]() $q^4\not =1$

, the roots

$q^4\not =1$

, the roots

![]() $1$

,

$1$

,

![]() $q^2$

,

$q^2$

,

![]() $q^{-2}$

of the characteristic equation for the linear homogeneous recurrence (i) are mutually distinct. Thus there are

$q^{-2}$

of the characteristic equation for the linear homogeneous recurrence (i) are mutually distinct. Thus there are

![]() $c_0,c_1,c_2\in \mathbb F$

such that

$c_0,c_1,c_2\in \mathbb F$

such that

By (ii), the following linear equations hold:

$$ \begin{align*} \left\{ \begin{array}{ll} c_0 + q^{2j}c_1 + q^{-2j} c_2 =0, \\ c_0 + q^{2k}c_1 + q^{-2k} c_2 =0, \\ c_0 + q^{2\ell}c_1 + q^{-2\ell} c_2 =0. \end{array} \right. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \left\{ \begin{array}{ll} c_0 + q^{2j}c_1 + q^{-2j} c_2 =0, \\ c_0 + q^{2k}c_1 + q^{-2k} c_2 =0, \\ c_0 + q^{2\ell}c_1 + q^{-2\ell} c_2 =0. \end{array} \right. \end{align*} $$

The determinant of the coefficient matrix for the above linear equations is equal to

Since each of

![]() $k-j$

,

$k-j$

,

![]() $\ell -k$

,

$\ell -k$

,

![]() $\ell -j$

is a positive integer less than

$\ell -j$

is a positive integer less than ![]() , none of

, none of

![]() $q^{2(k-j)}$

,

$q^{2(k-j)}$

,

![]() $q^{2(\ell -k)}$

,

$q^{2(\ell -k)}$

,

![]() $q^{2(\ell -j)}$

is equal to one. Therefore the determinant is nonzero. Since the coefficient matrix is invertible, each of

$q^{2(\ell -j)}$

is equal to one. Therefore the determinant is nonzero. Since the coefficient matrix is invertible, each of

![]() $c_0, c_1, c_2$

is zero. The lemma follows.

$c_0, c_1, c_2$

is zero. The lemma follows.

Proof of Theorem 1.6

By Lemma 2.3, there exists a marginal weight

![]() $\mu $

of the

$\mu $

of the

![]() $\triangle _q$

-module V. By Lemma 3.4, there are a nonzero vector v of V and three scalars

$\triangle _q$

-module V. By Lemma 3.4, there are a nonzero vector v of V and three scalars

![]() $\varphi ,\omega ^*,\omega ^\varepsilon \in \mathbb F$

satisfying equations (3.7)–(3.10).

$\varphi ,\omega ^*,\omega ^\varepsilon \in \mathbb F$

satisfying equations (3.7)–(3.10).

By Lemma 2.3, there exists a marginal weight

![]() $\kappa $

of the

$\kappa $

of the

![]() $\triangle _q$

-module

$\triangle _q$

-module

![]() $V^\vee $

. Let n denote the dimension of V minus one. Set

$V^\vee $

. Let n denote the dimension of V minus one. Set

and let c be the scalar in

![]() $\mathbb F^\times $

satisfying

$\mathbb F^\times $

satisfying

$$ \begin{align} c+c^{-1}=&\left\{ \begin{array}{ll} \displaystyle \frac{\omega^\varepsilon-(a+a^{-1})(b+b^{-1})}{\lambda q+\lambda^{-1}q^{-1}} \qquad &\text{if } n=0, \\ \displaystyle \frac{\varphi+(a+a^{-1})(bq-b^{-1}q^{-1})}{\lambda-\lambda^{-1}} \qquad &\text{if }n\geq 1. \end{array} \right. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} c+c^{-1}=&\left\{ \begin{array}{ll} \displaystyle \frac{\omega^\varepsilon-(a+a^{-1})(b+b^{-1})}{\lambda q+\lambda^{-1}q^{-1}} \qquad &\text{if } n=0, \\ \displaystyle \frac{\varphi+(a+a^{-1})(bq-b^{-1}q^{-1})}{\lambda-\lambda^{-1}} \qquad &\text{if }n\geq 1. \end{array} \right. \end{align} $$

Since ![]() , it follows that

, it follows that

![]() $\lambda ^2=1$

if and only if

$\lambda ^2=1$

if and only if

![]() $n=0$

. Since

$n=0$

. Since

![]() $q^4\not =1$

, it follows that

$q^4\not =1$

, it follows that

![]() $\lambda ^2 \not =-q^{-2}$

when

$\lambda ^2 \not =-q^{-2}$

when

![]() $n=0$

. Hence the denominators in the right-hand side of (4.2) are nonzero. Since

$n=0$

. Hence the denominators in the right-hand side of (4.2) are nonzero. Since

![]() $\mathbb F$

is algebraically closed, the existence of c follows.

$\mathbb F$

is algebraically closed, the existence of c follows.

We are now going to show that

![]() $(a,b,c,\lambda )$

is feasible for

$(a,b,c,\lambda )$

is feasible for

![]() $(\mu ,\varphi ,\omega ^*,\omega ^\varepsilon )$

. Apparently, Definition 3.2(i) is immediate from (4.1). Due to (4.2), we divide the argument into two cases:

$(\mu ,\varphi ,\omega ^*,\omega ^\varepsilon )$

. Apparently, Definition 3.2(i) is immediate from (4.1). Due to (4.2), we divide the argument into two cases:

![]() $n=0$

and

$n=0$

and

![]() $n\geq 1$

.

$n\geq 1$

.

![]() $(n=0)$

: In this case, v is a basis for V and

$(n=0)$

: In this case, v is a basis for V and

![]() $(a,b,\lambda )=(\kappa ,\mu ,1)$

. Definition 3.2(iv) is immediate from (4.2). Since a is a weight of

$(a,b,\lambda )=(\kappa ,\mu ,1)$

. Definition 3.2(iv) is immediate from (4.2). Since a is a weight of

![]() $V^\vee $

, it follows from Lemma 4.1 that

$V^\vee $

, it follows from Lemma 4.1 that

on V. Evaluating the left-hand side of (3.8) by using (3.7) and (4.3) yields

Definition 3.2(ii) follows. Applying both sides of (1.6) to v, we evaluate the resulting equation by using (3.7) and (4.3). It follows that

![]() $\omega ^*$

is equal to

$\omega ^*$

is equal to

$$ \begin{align*}(a+a^{-1}) \cdot \frac{\omega^\varepsilon-(a+a^{-1})(b+b^{-1})}{q+q^{-1}} + (q+q^{-1})(b+b^{-1}). \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}(a+a^{-1}) \cdot \frac{\omega^\varepsilon-(a+a^{-1})(b+b^{-1})}{q+q^{-1}} + (q+q^{-1})(b+b^{-1}). \end{align*} $$

Definition 3.2(iii) follows by substituting Definition 3.2(iv) into the above scalar. Therefore

![]() $(a,b,c,\lambda )$

is feasible for

$(a,b,c,\lambda )$

is feasible for

![]() $(\mu ,\varphi ,\omega ^*,\omega ^\varepsilon )$

when

$(\mu ,\varphi ,\omega ^*,\omega ^\varepsilon )$

when

![]() $n=0$

.

$n=0$

.

![]() $(n\geq 1)$

: Definition 3.2(ii) is immediate from (4.2). Set

$(n\geq 1)$

: Definition 3.2(ii) is immediate from (4.2). Set

By Lemma 2.7, the vectors

![]() $\{v_i\}_{i=0}^n$

are a basis for V. By Lemma 2.5, there exists a marginal weight vector w of the

$\{v_i\}_{i=0}^n$

are a basis for V. By Lemma 2.5, there exists a marginal weight vector w of the

![]() $\triangle _q$

-module

$\triangle _q$

-module

![]() $V^\vee $

with weight

$V^\vee $

with weight

![]() $\kappa $

. It follows from Lemma 2.6(ii) that

$\kappa $

. It follows from Lemma 2.6(ii) that

![]() $\prod _{i=0}^n (A-\theta _i)$

vanishes at

$\prod _{i=0}^n (A-\theta _i)$

vanishes at

![]() $\{B^i w\}_{i=0}^n$

on the

$\{B^i w\}_{i=0}^n$

on the

![]() $\triangle _q$

-module V. By Lemma 2.7, the vectors

$\triangle _q$

-module V. By Lemma 2.7, the vectors

![]() $\{B^i w\}_{i=0}^n$

are also a basis for V. Hence

$\{B^i w\}_{i=0}^n$

are also a basis for V. Hence

![]() $ \prod _{i=0}^n (A-\theta _i) $

vanishes on V. Combined with (4.4), this implies that

$ \prod _{i=0}^n (A-\theta _i) $

vanishes on V. Combined with (4.4), this implies that

Let

![]() $\varphi ^{(i)}_j\in \mathbb F$

for all integers

$\varphi ^{(i)}_j\in \mathbb F$

for all integers

![]() $i,j$

with

$i,j$

with

![]() $0\leq i,j\leq n$

such that

$0\leq i,j\leq n$

such that

$$ \begin{align} (B-\theta_i^*)v_i= & \sum_{j=0}^n \varphi^{(i)}_j v_j. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} (B-\theta_i^*)v_i= & \sum_{j=0}^n \varphi^{(i)}_j v_j. \end{align} $$

By Lemma 2.6(i), the coefficients

Applying (3.7) and (3.8) yields that

Evaluating the right-hand side of the above equation by using Definition 3.2(ii) yields that

For any integer i with

![]() $1\leq i\leq n$

, we apply both sides of (1.6) to

$1\leq i\leq n$

, we apply both sides of (1.6) to

![]() $v_{i-1}$

and evaluate the coefficient of

$v_{i-1}$

and evaluate the coefficient of

![]() $v_i$

in the resulting equation using (3.7) and (4.4)–(4.7). It follows that

$v_i$

in the resulting equation using (3.7) and (4.4)–(4.7). It follows that

Here,

![]() $\varphi ^{(0)}_{-1}=\varphi ^{(n+1)}_n=0$

and

$\varphi ^{(0)}_{-1}=\varphi ^{(n+1)}_n=0$

and

Applying (4.9) yields that

On the other hand, a direct calculation shows that

![]() $\{\varphi _i\}_{i=0}^{n+1}$

also satisfy the same recurrence. Hence the scalars

$\{\varphi _i\}_{i=0}^{n+1}$

also satisfy the same recurrence. Hence the scalars

satisfy Lemma 4.2(i). By (4.8) and since

![]() $\varphi _0=\varphi _{n+1}=\varphi ^{(0)}_{-1}=\varphi ^{(n+1)}_n=0$

, it follows that

$\varphi _0=\varphi _{n+1}=\varphi ^{(0)}_{-1}=\varphi ^{(n+1)}_n=0$

, it follows that

![]() $h_0=h_1=h_{n+1}=0$

. Applying Lemma 4.2 yields

$h_0=h_1=h_{n+1}=0$

. Applying Lemma 4.2 yields

It is now routine to verify Definition 3.2(iv) by substituting the above equations into (4.9).

For any integer i with

![]() $0\leq i\leq n$

, we apply both sides of (1.6) to

$0\leq i\leq n$

, we apply both sides of (1.6) to

![]() $v_i$

and evaluate the coefficient of

$v_i$

and evaluate the coefficient of

![]() $v_i$

in the resulting equation. It follows that

$v_i$

in the resulting equation. It follows that

Here,

![]() $\varphi ^{(0)}_{-2}=\varphi ^{(1)}_{-1}=\varphi ^{(n+1)}_{n-1}=\varphi ^{(n+2)}_n=0$

and

$\varphi ^{(0)}_{-2}=\varphi ^{(1)}_{-1}=\varphi ^{(n+1)}_{n-1}=\varphi ^{(n+2)}_n=0$

and

$$ \begin{align*} \begin{split} c_i &= (\theta_i-\theta_{i+1})\varphi_i +(\theta_i-\theta_{i-1})\varphi_{i+1} -(q-q^{-1})^2\theta_i^2\theta_i^* \\ & \qquad +\,(q^2-q^{-2})^2\theta_i^* +(q-q^{-1})^2\theta_i\omega^\varepsilon \end{split} \qquad (0\leq i\leq n), \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \begin{split} c_i &= (\theta_i-\theta_{i+1})\varphi_i +(\theta_i-\theta_{i-1})\varphi_{i+1} -(q-q^{-1})^2\theta_i^2\theta_i^* \\ & \qquad +\,(q^2-q^{-2})^2\theta_i^* +(q-q^{-1})^2\theta_i\omega^\varepsilon \end{split} \qquad (0\leq i\leq n), \end{align*} $$

where

![]() $\theta _{-1}=a q^{-n-2}+a^{-1} q^{n+2}$

. A direct calculation shows that

$\theta _{-1}=a q^{-n-2}+a^{-1} q^{n+2}$

. A direct calculation shows that

![]() $c_i$

is equal to

$c_i$

is equal to

![]() $(q-q^{-1})(q^2-q^{-2})$

times the right-hand side of Definition 3.2(iii) for each

$(q-q^{-1})(q^2-q^{-2})$

times the right-hand side of Definition 3.2(iii) for each

![]() $i=0,1,\ldots ,n$

. Combined with (4.10), this implies that the values of

$i=0,1,\ldots ,n$

. Combined with (4.10), this implies that the values of

![]() $ \varphi ^{(i+2)}_i -(q^2+q^{-2})\varphi ^{(i+1)}_{i-1} +\varphi ^{(i)}_{i-2} $

are identical for all

$ \varphi ^{(i+2)}_i -(q^2+q^{-2})\varphi ^{(i+1)}_{i-1} +\varphi ^{(i)}_{i-2} $

are identical for all

![]() $i=0,1,\ldots ,n$

. It follows that

$i=0,1,\ldots ,n$

. It follows that

Applying Lemma 4.2 yields

Definition 3.2(iii) follows by substituting the above equations into (4.10). Therefore,

![]() $(a,b,c,\lambda )$

is feasible for

$(a,b,c,\lambda )$

is feasible for

![]() $(\mu ,\varphi ,\omega ^*,\omega ^\varepsilon )$

when

$(\mu ,\varphi ,\omega ^*,\omega ^\varepsilon )$

when

![]() $n\geq 1$

.

$n\geq 1$

.

Since

![]() $(a,b,c,\lambda )$

is feasible for

$(a,b,c,\lambda )$

is feasible for

![]() $(\mu ,\varphi ,\omega ^*,\omega ^\varepsilon )$

, it follows from Theorem 3.3 that there exists a

$(\mu ,\varphi ,\omega ^*,\omega ^\varepsilon )$

, it follows from Theorem 3.3 that there exists a

![]() $\triangle _q$

-module homomorphism

$\triangle _q$

-module homomorphism

that sends

![]() $m_0$

to v. By (4.3) and (4.5), the vector

$m_0$

to v. By (4.3) and (4.5), the vector

![]() $m_{n+1}$

lies in the kernel of (4.11). Recall from Section 1 that the

$m_{n+1}$

lies in the kernel of (4.11). Recall from Section 1 that the

![]() $\triangle _q$

-submodule

$\triangle _q$

-submodule

![]() $N_\lambda (a,b,c)$

of

$N_\lambda (a,b,c)$

of

![]() $M_\lambda (a,b,c)$

is generated by

$M_\lambda (a,b,c)$

is generated by

![]() $m_{n+1}$

. Hence (4.11) induces the

$m_{n+1}$

. Hence (4.11) induces the

![]() $\triangle _q$

-module homomorphism

$\triangle _q$

-module homomorphism

that sends

![]() $m_0+N_\lambda (a,b,c)$

to v. Since

$m_0+N_\lambda (a,b,c)$

to v. Since

![]() $V_n(a,b,c)$

and V have the same dimension

$V_n(a,b,c)$

and V have the same dimension

![]() $n+1$

and by the irreducibility of the

$n+1$

and by the irreducibility of the

![]() $\triangle _q$

-module V, the map (4.12) is a

$\triangle _q$

-module V, the map (4.12) is a

![]() $\triangle _q$

-module isomorphism. The result follows.

$\triangle _q$

-module isomorphism. The result follows.

5. A polynomial characterization for the feasible relation

Theorem 5.1. Assume that

![]() $(\mu ,\varphi ,\omega ^*,\omega ^\varepsilon )\in \mathbb F^\times \times \mathbb F^3$

. For any scalars

$(\mu ,\varphi ,\omega ^*,\omega ^\varepsilon )\in \mathbb F^\times \times \mathbb F^3$

. For any scalars

![]() $\kappa ,\lambda ,c\in \mathbb F^\times $

, the quadruple

$\kappa ,\lambda ,c\in \mathbb F^\times $

, the quadruple

![]() $ (\kappa \lambda ,\mu \lambda ,c,\lambda ) $

is feasible for

$ (\kappa \lambda ,\mu \lambda ,c,\lambda ) $

is feasible for

![]() $(\mu ,\varphi ,\omega ^*,\omega ^\varepsilon )$

if and only if the following conditions hold:

$(\mu ,\varphi ,\omega ^*,\omega ^\varepsilon )$

if and only if the following conditions hold:

-

(i)

$\kappa $

is a root of the polynomial

$\kappa $

is a root of the polynomial  $$ \begin{align*}\frac{x^4}{\mu q} -\frac{\omega^\varepsilon+q^{-1}\varphi}{q+q^{-1}}x^3 +(\omega^*-\mu q^{-1}-\mu^{-1} q)x^2 -\frac{\omega^\varepsilon-q\varphi}{q+q^{-1}}x +\mu q. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}\frac{x^4}{\mu q} -\frac{\omega^\varepsilon+q^{-1}\varphi}{q+q^{-1}}x^3 +(\omega^*-\mu q^{-1}-\mu^{-1} q)x^2 -\frac{\omega^\varepsilon-q\varphi}{q+q^{-1}}x +\mu q. \end{align*} $$

-

(ii)

$\lambda $

is a root of the polynomial

$\lambda $

is a root of the polynomial  $$ \begin{align*}\kappa\mu q x^6 + \left( \kappa^{-1}\mu q -\frac{\omega^\varepsilon-q\varphi}{q+q^{-1}} \right)x^4 + \left( \frac{\omega^\varepsilon+q^{-1}\varphi}{q+q^{-1}} - \kappa\mu^{-1} q^{-1} \right)x^2 -\frac{1}{\kappa\mu q}. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}\kappa\mu q x^6 + \left( \kappa^{-1}\mu q -\frac{\omega^\varepsilon-q\varphi}{q+q^{-1}} \right)x^4 + \left( \frac{\omega^\varepsilon+q^{-1}\varphi}{q+q^{-1}} - \kappa\mu^{-1} q^{-1} \right)x^2 -\frac{1}{\kappa\mu q}. \end{align*} $$

-

(iii) c is a root of

$x^2-rx+1$

, where

$x^2-rx+1$

, where  $$ \begin{align*} r= \left\{ \begin{array}{ll} \displaystyle \frac{\omega^\varepsilon-(\kappa \lambda+\kappa^{-1}\lambda^{-1})(\mu\lambda+\mu^{-1}\lambda^{-1})}{\lambda q+\lambda^{-1} q^{-1}} \qquad &\text{if }\lambda^2=1, \\ \displaystyle \frac{\varphi+(\kappa\lambda +\kappa^{-1}\lambda^{-1})(\mu\lambda q-\mu^{-1}\lambda^{-1}q^{-1})}{\lambda-\lambda^{-1}} \qquad &\text{if }\lambda^2\not=1. \end{array} \right. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} r= \left\{ \begin{array}{ll} \displaystyle \frac{\omega^\varepsilon-(\kappa \lambda+\kappa^{-1}\lambda^{-1})(\mu\lambda+\mu^{-1}\lambda^{-1})}{\lambda q+\lambda^{-1} q^{-1}} \qquad &\text{if }\lambda^2=1, \\ \displaystyle \frac{\varphi+(\kappa\lambda +\kappa^{-1}\lambda^{-1})(\mu\lambda q-\mu^{-1}\lambda^{-1}q^{-1})}{\lambda-\lambda^{-1}} \qquad &\text{if }\lambda^2\not=1. \end{array} \right. \end{align*} $$

Proof. Let

Clearly, Definition 3.2(i) holds. Then

![]() $(a,b,c,\lambda )$

is feasible for

$(a,b,c,\lambda )$

is feasible for

![]() $(\mu ,\varphi ,\omega ^*,\omega ^\varepsilon )$

if and only if Definition 3.2(ii)–(iv) hold.

$(\mu ,\varphi ,\omega ^*,\omega ^\varepsilon )$

if and only if Definition 3.2(ii)–(iv) hold.

(

![]() $\Rightarrow $

): Suppose that Definition 3.2(ii)–(iv) hold and we show (i)–(iii). Condition (iii) is immediate from Definition 3.2(ii) if

$\Rightarrow $

): Suppose that Definition 3.2(ii)–(iv) hold and we show (i)–(iii). Condition (iii) is immediate from Definition 3.2(ii) if

![]() $\lambda ^2\not =1$

; condition (iii) is immediate from Definition 3.2(iv) if

$\lambda ^2\not =1$

; condition (iii) is immediate from Definition 3.2(iv) if

![]() $\lambda ^2=1$

.

$\lambda ^2=1$

.

Using Definition 3.2(ii) and (iv), it is routine to verify that

$$ \begin{align} \frac{\omega^\varepsilon+q^{-1}\varphi}{q+q^{-1}}&=\lambda(c+c^{-1})+b^{-1}q^{-1}(a+a^{-1}). \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \frac{\omega^\varepsilon+q^{-1}\varphi}{q+q^{-1}}&=\lambda(c+c^{-1})+b^{-1}q^{-1}(a+a^{-1}). \end{align} $$

We multiply (5.2) and (5.3) by

![]() $\lambda $

and

$\lambda $

and

![]() $\lambda ^{-1}$

, respectively. The difference between the resulting equations gives

$\lambda ^{-1}$

, respectively. The difference between the resulting equations gives

$$ \begin{align*}\lambda\frac{\omega^\varepsilon-q\varphi}{q+q^{-1}}-\lambda^{-1}\frac{\omega^\varepsilon+q^{-1}\varphi}{q+q^{-1}} =(a+a^{-1})(b\lambda q-b^{-1} \lambda^{-1} q^{-1}). \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}\lambda\frac{\omega^\varepsilon-q\varphi}{q+q^{-1}}-\lambda^{-1}\frac{\omega^\varepsilon+q^{-1}\varphi}{q+q^{-1}} =(a+a^{-1})(b\lambda q-b^{-1} \lambda^{-1} q^{-1}). \end{align*} $$

Condition (ii) follows by substituting (5.1) into the above equation.

We multiply (5.2) and (5.3) by

![]() $a^{-1}\lambda $

and

$a^{-1}\lambda $

and

![]() $a\lambda ^{-1}$

, respectively. The sum of the resulting equations gives

$a\lambda ^{-1}$