1. Introduction

Giant radio galaxies are among the largest single objects in the Universe, typically defined as having projected linear sizes larger than 0.7 Mpc or 1 Mpc, depending on the study (e.g. Schoenmakers et al. Reference Schoenmakers, de Bruyn, Röttgering and van der Laan2001; Kuźmicz et al. Reference Kuźmicz, Jamrozy, Bronarska, Janda-Boczar and Saikia2018; Hardcastle2020; Dabhade et al. Reference Dabhade2020b; Andernach, Jiménez-Andrade, & Willis Reference Andernach, Jiménez-Andrade and Willis2021; Saikia Reference Saikia2022; Simonte et al. Reference Simonte2022; Oei et al. Reference Oei2023). This makes even the smallest GRGs

![]() $\sim$

10–20 times larger than a typical Milky Way-like spiral galaxy and similar in size to the Local Group. GRGs give evidence to some of the most energetic processes inside their host elliptical galaxies and the morphologies of their radio lobes reflect the properties of their surrounding intergalactic medium (IGM). The presence of a host galaxy and their typically double-lobed radio morphology clearly distinguishes GRGs from other large radio sources such as cluster halos and cluster relics.

$\sim$

10–20 times larger than a typical Milky Way-like spiral galaxy and similar in size to the Local Group. GRGs give evidence to some of the most energetic processes inside their host elliptical galaxies and the morphologies of their radio lobes reflect the properties of their surrounding intergalactic medium (IGM). The presence of a host galaxy and their typically double-lobed radio morphology clearly distinguishes GRGs from other large radio sources such as cluster halos and cluster relics.

Radio galaxies can be studied in great detail when well resolved by interferometric radio continuum observations. The large extent of giant radio lobes highlights their old age while their intricate shapes inform us about the local and large-scale environment, particularly density variations in the ambient IGM (e.g. Malarecki et al. Reference Malarecki, Jones, Saripalli, Staveley-Smith and Subrahmanyan2015; Peng, Chen, & Strom Reference Peng, Chen and Strom2015). During the active phase, the expanding jets and lobes forge a path through the IGM, while being impacted by the same medium. In contrast, during their inactive phase, the old radio lobes and their surrounding IGM slowly reach a pressure balance. In over half of the known GRGs, Bruni et al. (Reference Bruni2019) find the central radio sources to be relatively young, likely linked to the episodic/re-starting activity of super-massive black holes (SMBHs); see also Jurlin et al. (Reference Jurlin2020).

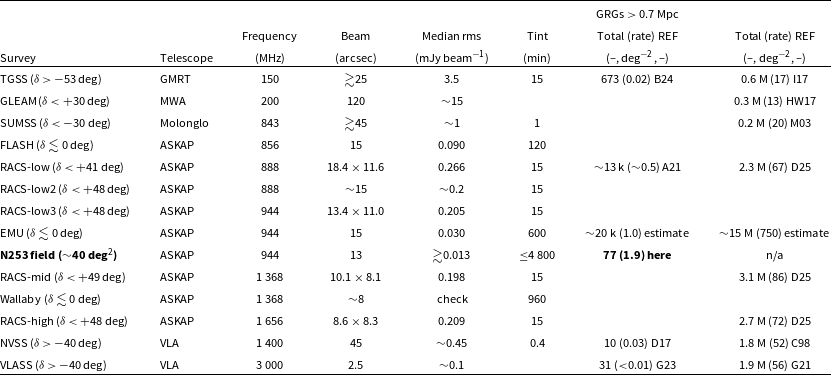

Recent large-scale radio surveys such as the ‘Evolutionary Map of the Universe’ (EMU, Norris et al. Reference Norris2011, Reference Norris2021a) and the ‘Widefield ASKAP L-band Legacy All-sky Blind surveY’ (WALLABY, Koribalski Reference Koribalski2012; Koribalski et al. Reference Koribalski2020) projects, both conducted with the Australian Square Kilometre Array Pathfinder (ASKAP, Johnston et al. Reference Johnston2008; Hotan et al. Reference Hotan2021), as well as the ‘LOFAR Two Metre Sky Survey’ (LoTSS, Shimwell et al. Reference Shimwell2019), have resulted in many new discoveries and a resurgence of GRG studies. Using LOTSS, Dabhade et al. (Reference Dabhade2020a) find a sky density of

![]() $\sim$

1.8 deg

$\sim$

1.8 deg

![]() $^{-2}$

for radio galaxies larger than 0.7 Mpc, with only seven GRGs larger than 2 Mpc (see also Simonte et al. Reference Simonte, Andernach, Brüggen, Miley and Barthel2024). Both ASKAP’s and LOFAR’s large field of view, high resolution, dynamic range, and good sensitivity to low-surface brightness structures have been essential to this research field, complemented by multi-colour optical sky surveys together with millions of photometric redshifts (e.g. Bilicki et al. Reference Bilicki, Jarrett, Peacock, Cluver and Steward2014; Bilicki et al. Reference Bilicki2016; Zou et al. Reference Zou, Gao, Zhou and Kong2019; Zhou et al. Reference Zhou2021).

$^{-2}$

for radio galaxies larger than 0.7 Mpc, with only seven GRGs larger than 2 Mpc (see also Simonte et al. Reference Simonte, Andernach, Brüggen, Miley and Barthel2024). Both ASKAP’s and LOFAR’s large field of view, high resolution, dynamic range, and good sensitivity to low-surface brightness structures have been essential to this research field, complemented by multi-colour optical sky surveys together with millions of photometric redshifts (e.g. Bilicki et al. Reference Bilicki, Jarrett, Peacock, Cluver and Steward2014; Bilicki et al. Reference Bilicki2016; Zou et al. Reference Zou, Gao, Zhou and Kong2019; Zhou et al. Reference Zhou2021).

In the wide-field ASKAP image of the Abell 3391/5 cluster (887.5 MHz, 30 deg

![]() $^2$

, rms

$^2$

, rms

![]() $\sim$

30

$\sim$

30

![]() $\unicode{x03BC}$

Jy beam

$\unicode{x03BC}$

Jy beam

![]() $^{-1}$

) Brüggen et al. (Reference Brüggen2021) found densities of 0.8 (1.7) deg

$^{-1}$

) Brüggen et al. (Reference Brüggen2021) found densities of 0.8 (1.7) deg

![]() $^{-2}$

for radio galaxies larger than 1 (0.7) Mpc, a factor 4 (3) higher than the densities given in Dabhade et al. (Reference Dabhade2020a). On the other hand, Gürkan et al. (Reference Gürkan2022) found only 63 GRGs

$^{-2}$

for radio galaxies larger than 1 (0.7) Mpc, a factor 4 (3) higher than the densities given in Dabhade et al. (Reference Dabhade2020a). On the other hand, Gürkan et al. (Reference Gürkan2022) found only 63 GRGs

![]() $\gt$

0.7 Mpc in the ASKAP GAMA23 field (887.5 MHz, 83 deg

$\gt$

0.7 Mpc in the ASKAP GAMA23 field (887.5 MHz, 83 deg

![]() $^2$

, rms

$^2$

, rms

![]() $\sim$

38

$\sim$

38

![]() $\unicode{x03BC}$

Jy beam

$\unicode{x03BC}$

Jy beam

![]() $^{-1}$

), i.e.

$^{-1}$

), i.e.

![]() $\sim$

0.8 deg

$\sim$

0.8 deg

![]() $^{-2}$

. For the EMU Pilot Survey (944 MHz, 270 deg

$^{-2}$

. For the EMU Pilot Survey (944 MHz, 270 deg

![]() $^2$

, rms

$^2$

, rms

![]() $\sim$

25–30

$\sim$

25–30

![]() $\unicode{x03BC}$

Jy beam

$\unicode{x03BC}$

Jy beam

![]() $^{-1}$

) Norris et al. (Reference Norris2021a) report a preliminary number of at least 120 GRGs

$^{-1}$

) Norris et al. (Reference Norris2021a) report a preliminary number of at least 120 GRGs

![]() $\gt$

1 Mpc (and a similar number with sizes between 0.7 and 1 Mpc) among the

$\gt$

1 Mpc (and a similar number with sizes between 0.7 and 1 Mpc) among the

![]() $\sim$

220 000 catalogued sources. Andernach et al. (Reference Andernach, Jiménez-Andrade and Willis2021) present the discovery of 178 GRGs

$\sim$

220 000 catalogued sources. Andernach et al. (Reference Andernach, Jiménez-Andrade and Willis2021) present the discovery of 178 GRGs

![]() $\gt$

1 Mpc within 1 059 deg

$\gt$

1 Mpc within 1 059 deg

![]() $^2$

, a small area within the shallow Rapid ASKAP Continuum Survey (RACS, McConnell et al. Reference McConnell2020) at 887.5 MHz (RACS-low, DEC

$^2$

, a small area within the shallow Rapid ASKAP Continuum Survey (RACS, McConnell et al. Reference McConnell2020) at 887.5 MHz (RACS-low, DEC

![]() $\lt$

+40 deg, rms

$\lt$

+40 deg, rms

![]() $\sim$

250

$\sim$

250

![]() $\unicode{x03BC}$

Jy beam

$\unicode{x03BC}$

Jy beam

![]() $^{-1}$

). In the LOTSS Boötes deep field at 150 MHz (rms

$^{-1}$

). In the LOTSS Boötes deep field at 150 MHz (rms

![]() $\sim$

30

$\sim$

30

![]() $\unicode{x03BC}$

Jy beam

$\unicode{x03BC}$

Jy beam

![]() $^{-1}$

) Simonte et al. (Reference Simonte2022) find somewhat higher sky densities of

$^{-1}$

) Simonte et al. (Reference Simonte2022) find somewhat higher sky densities of

![]() $\sim$

1.4 (2.8) deg

$\sim$

1.4 (2.8) deg

![]() $^{-2}$

GRGs with linear sizes

$^{-2}$

GRGs with linear sizes

![]() $ \gt \! 1$

(0.7) Mpc. As the survey depth, frequency, and angular resolution vary substantially, these numbers are only indicative and likely lower limits. For comprehensive overviews of the observational and theoretical progress on GRGs, see the early review by Komberg & Pashchenko (Reference Komberg and Pashchenko2009) and the more recent, broader synthesis by Dabhade, Saikia, & Mahato (Reference Dabhade, Saikia and Mahato2023).

$ \gt \! 1$

(0.7) Mpc. As the survey depth, frequency, and angular resolution vary substantially, these numbers are only indicative and likely lower limits. For comprehensive overviews of the observational and theoretical progress on GRGs, see the early review by Komberg & Pashchenko (Reference Komberg and Pashchenko2009) and the more recent, broader synthesis by Dabhade, Saikia, & Mahato (Reference Dabhade, Saikia and Mahato2023).

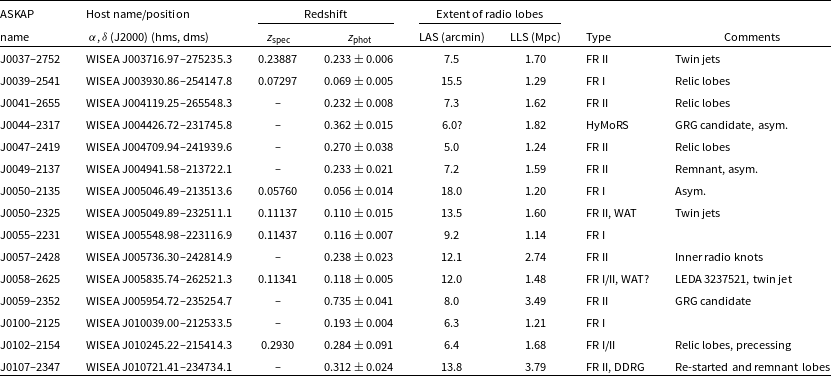

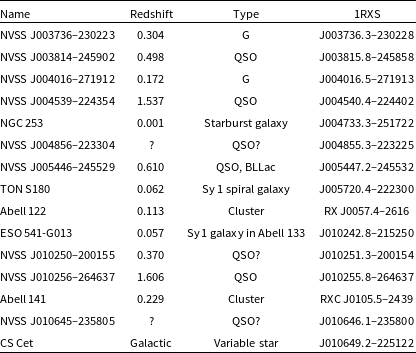

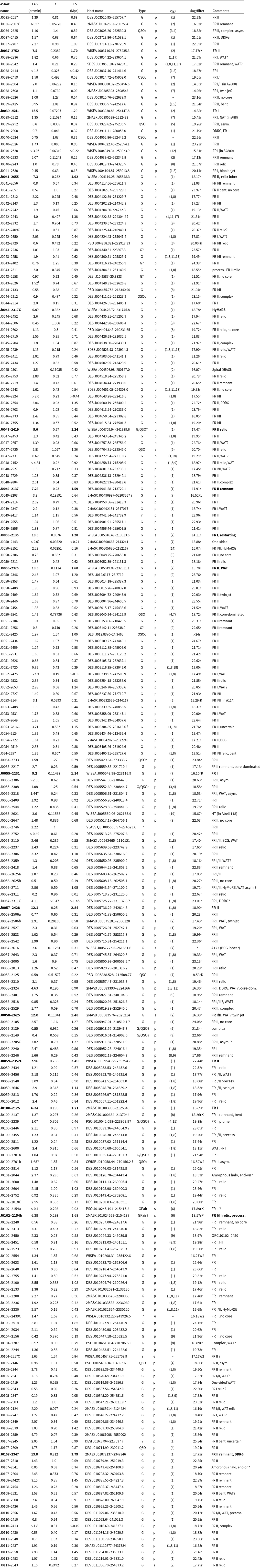

Table 1. Properties of the 15 GRGs with the largest angular sizes in the ASKAP Sculptor field and their respective host galaxies. In Col. (2), we chose the WISE names of the host galaxies, while each has numerous designations. Spectroscopic redshifts (

![]() $z_{\rm spec}$

) were obtained from 2dF (Colless et al. Reference Colless2001) or 6dF (Jones et al. Reference Jones2009) as noted in Section 3.1. Photometric redshifts (

$z_{\rm spec}$

) were obtained from 2dF (Colless et al. Reference Colless2001) or 6dF (Jones et al. Reference Jones2009) as noted in Section 3.1. Photometric redshifts (

![]() $z_{\mathrm{phot}}$

) and their uncertainties were obtained from DES-DR9 (Zhou et al. Reference Zhou2021).

$z_{\mathrm{phot}}$

) and their uncertainties were obtained from DES-DR9 (Zhou et al. Reference Zhou2021).

Radio galaxies (RGs) come in a wide range of morphologies (e.g. Banfield et al. Reference Banfield2015), the most common of which are briefly described below. We note that RG classifications can change when more detailed (higher sensitivity/resolution) images become available.

-

• Fanaroff-Riley Class I (FR I) galaxies have bright inner radio jets and fading outer radio lobes without hotspots (edge-darkened). Typical examples of this class are 3C 449 (Feretti et al. Reference Feretti, Perley, Giovannini and Andernach1999) and IC 4296 (Condon et al. Reference Condon2021).

-

• Fanaroff-Riley Class II (FR II) galaxies are characterised by prominent radio hot spots at the end of their radio lobes (edge-brightened). A typical example of this class is 3C 98 (Leahy et al. Reference Leahy1997).

-

• Hybrid Morphology Radio Sources (HyMoRS) show a mix of FR I and FR II morphology (e.g. Harwood, Vernstrom, & Stroe Reference Harwood, Vernstrom and Stroe2020; Stroe et al. Reference Stroe, Catlett, Harwood, Vernstrom and Mingo2022). Some radio galaxies, like Hercules A (3C 348) are classified as intermediate FR I/II sources (e.g. Timmerman et al. Reference Timmerman2022).

-

• X-shaped radio galaxies (XRG), like the GRG PKS 2014–55, consist of a double-lobed radio galaxy plus a set of secondary lobes, referred to as wings, likely due to backflow (e.g. Cotton et al. Reference Cotton2020).

-

• The lobes of radio galaxies are shaped by their surrounding intergalactic medium (IGM) – esp. once the jets have turned off – and therefore display a wide variety of shapes. So-called ‘bent tail’ (BT) galaxies are sometimes classified as wide-angle tail (WAT) or narrow-angle tail (NAT) radio galaxies depending on the jet opening angle. But the tail appearances (and classifications) can vary hugely with image resolution and sensitivity, as shown for example by Gendron-Marsolais et al. (Reference Gendron-Marsolais2020) for NGC 1265. A subset of head-tail (HT) radio galaxies have two highly bent inner jets forming a single tail (e.g. the Corkscrew Galaxy, Jones & McAdam Reference Jones and McAdam1996; Koribalski et al. Reference Koribalski2024a). Bent tail radio galaxies are often (but not always) found in clusters (e.g. Veronica et al. Reference Veronica2022; Ramatsoku et al. Reference Ramatsoku2020).

-

• Remnant radio galaxies typically have two diffuse (amorphous), low surface brightness (LSB) radio lobes, and a weak radio core. They have neither jets nor hot spots, and their fading lobes are recognisable by steep spectral indices (e.g. Cordey Reference Cordey1987; Tamhane et al. Reference Tamhane2015; Brienza et al. Reference Brienza2016; Randriamanakoto, Ishwara-Chandra, & Taylor Reference Randriamanakoto, Ishwara-Chandra and Taylor2020). In these galaxies, the central SMBH has been inactive for some time and will likely re-start when triggered (Jurlin et al. Reference Jurlin2020; Shabala et al. Reference Shabala2020).

-

• Double-double radio galaxies (DDRG) have two sets of double lobes, typically one outer set of remnant (old) lobes and one inner set of new (young/re-started) radio lobes (e.g. Saripalli et al. Reference Saripalli2012; Kuźmicz et al. Reference Kuźmicz and Jamrozy2017; Dabhade et al. Reference Dabhade, Chavan, Saikia, Oei and Röttgering2025).

In this paper, we focus on the 15 newly discovered GRGs in the ASKAP Sculptor field with largest angular sizes (LAS)

![]() $\ge$

5 arcmin and projected largest linear sizes (LLS)

$\ge$

5 arcmin and projected largest linear sizes (LLS)

![]() $\gt$

1 Mpc, whose properties are summarised in Tables 1–3. The projected linear sizes are lower limits to their actual sizes, as neither inclination nor curvature is taken into account. Furthermore, deeper radio images often reveal larger sizes, esp. when the lobe emission is of very low surface brightness. The full sample of catalogued RGs in the field is presented in the Appendix. – We adopt the following cosmological parameters:

$\gt$

1 Mpc, whose properties are summarised in Tables 1–3. The projected linear sizes are lower limits to their actual sizes, as neither inclination nor curvature is taken into account. Furthermore, deeper radio images often reveal larger sizes, esp. when the lobe emission is of very low surface brightness. The full sample of catalogued RGs in the field is presented in the Appendix. – We adopt the following cosmological parameters:

![]() $H_\textrm{0}$

= 70 km s

$H_\textrm{0}$

= 70 km s

![]() $^{-1}$

Mpc

$^{-1}$

Mpc

![]() $^{-1}$

,

$^{-1}$

,

![]() $\Omega_{\textrm{m}}$

= 0.3, and

$\Omega_{\textrm{m}}$

= 0.3, and

![]() $\Omega_{\mathrm{\Lambda}}$

= 0.7.

$\Omega_{\mathrm{\Lambda}}$

= 0.7.

2. ASKAP observations and data processing

ASKAP is a 6 km diameter radio interferometer consisting of

![]() $36 \times 12$

-m antennas, each equipped with a wide-field Phased Array Feed (PAF), and operating at frequencies from 700 MHz to 1.8 GHz (Johnston et al. Reference Johnston2008). The currently available correlator bandwidth of 288 MHz is divided into

$36 \times 12$

-m antennas, each equipped with a wide-field Phased Array Feed (PAF), and operating at frequencies from 700 MHz to 1.8 GHz (Johnston et al. Reference Johnston2008). The currently available correlator bandwidth of 288 MHz is divided into

![]() $288 \times 1$

MHz coarse channels; the typical field-of-view is 30 deg

$288 \times 1$

MHz coarse channels; the typical field-of-view is 30 deg

![]() $^2$

. For a comprehensive overview see Hotan et al. (Reference Hotan2021). ASKAP science highlights are presented in Koribalski (Reference Koribalski2022).

$^2$

. For a comprehensive overview see Hotan et al. (Reference Hotan2021). ASKAP science highlights are presented in Koribalski (Reference Koribalski2022).

We obtained nine fully processed ASKAP radio continuum images from the CSIRO ASKAP Science Data Archive (CASDA), observed between August 2019 and December 2020 with the band centred at 944 MHz. The ASKAP PAFs were used to form 36 beams arranged in a closepack36 formation, each delivering

![]() $\sim$

30 deg

$\sim$

30 deg

![]() $^2$

field of view. All but one of the ASKAP fields were observed for

$^2$

field of view. All but one of the ASKAP fields were observed for

![]() $\sim$

10 h and have an average rms noise of

$\sim$

10 h and have an average rms noise of

![]() $\sim$

37

$\sim$

37

![]() $\unicode{x03BC}$

Jy beam

$\unicode{x03BC}$

Jy beam

![]() $^{-1}$

. When combining the ASKAP images, we omitted the short-integration (3.5 h) field due to its larger beam size. Seven fields have the same pointing centre, while the eighth field is slightly offset to the north-east and rotated by 67.5

$^{-1}$

. When combining the ASKAP images, we omitted the short-integration (3.5 h) field due to its larger beam size. Seven fields have the same pointing centre, while the eighth field is slightly offset to the north-east and rotated by 67.5

![]() $^\circ$

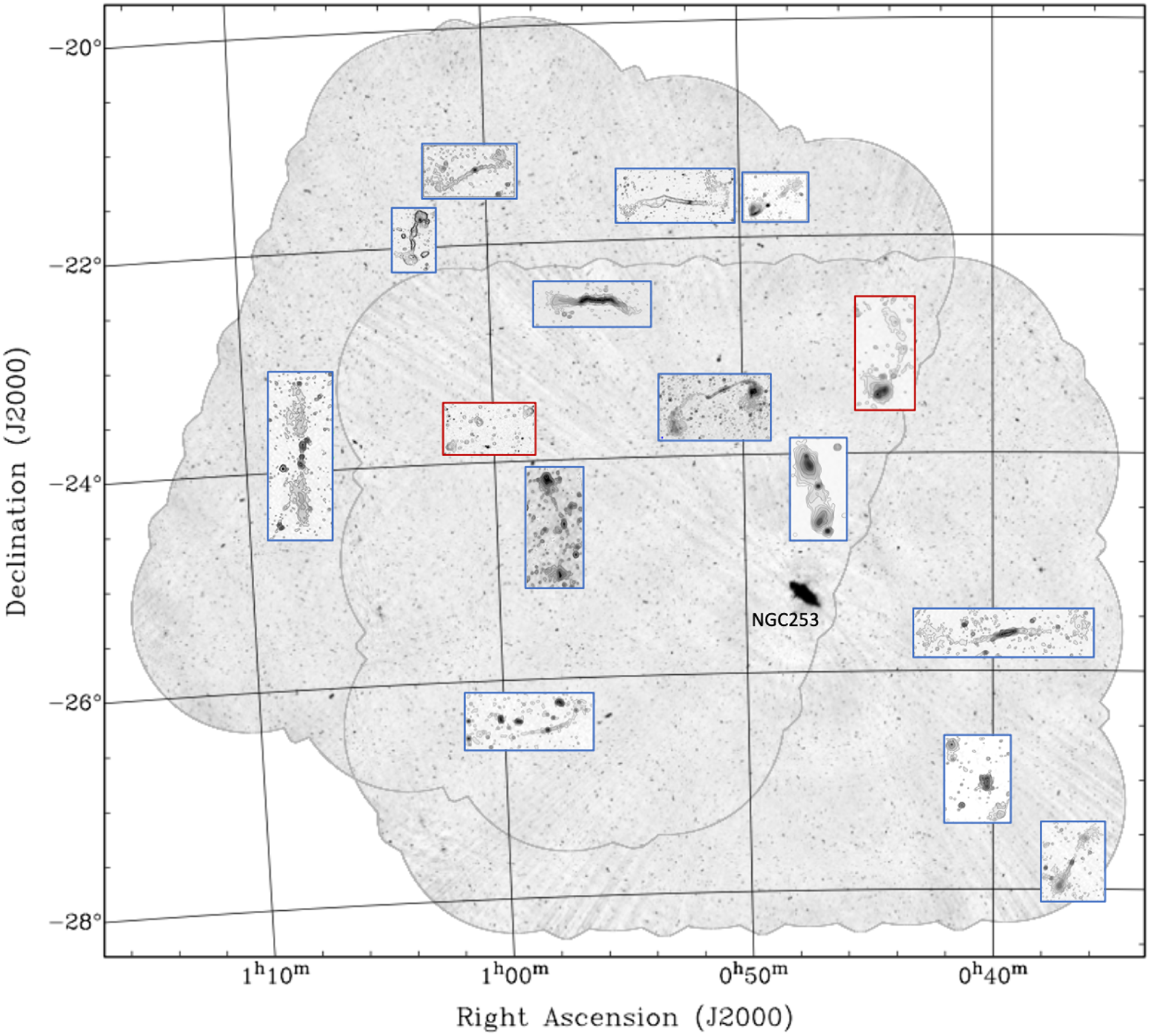

. Figure 1 shows the combined area of

$^\circ$

. Figure 1 shows the combined area of

![]() $\sim$

40 deg

$\sim$

40 deg

![]() $^2$

; the rms noiseFootnote

a

is

$^2$

; the rms noiseFootnote

a

is

![]() $\gtrsim$

10 mJy beam

$\gtrsim$

10 mJy beam

![]() $^{-1}$

. These are the same data used to analyse ORC J0102–2450 (Koribalski et al. Reference Koribalski2021). The field centres are close to the nearby (

$^{-1}$

. These are the same data used to analyse ORC J0102–2450 (Koribalski et al. Reference Koribalski2021). The field centres are close to the nearby (

![]() $v_{\rm sys}$

=

$v_{\rm sys}$

=

![]() $243 \pm 2$

km s

$243 \pm 2$

km s

![]() $^{-1}$

) starburst galaxy NGC 253 (Koribalski, Whiteoak, & Houghton Reference Koribalski, Whiteoak and Houghton1995; Koribalski et al. Reference Koribalski2004), which resides in the Sculptor Group. The radio brightness and large extent of the NGC 253 disc cause minor artifacts over part of the field. For a summary of the ASKAP observations, which were conducted to search for the radio counterpart of the gravitational wave event GW190814 (Abbott et al. 2020),Footnote

b

see Dobie et al. (Reference Dobie2022). The data processing was done with the ASKAPsoft pipeline (Whiting et al. Reference Whiting, Voronkov, Mitchell, Team, Lorente, Shortridge and Wayth2017; Wieringa, Raja, & Ord Reference Wieringa, Raja, Ord, Pizzo, Deul, Mol, de Plaa and Verkouter2020). We combined all eight

$^{-1}$

) starburst galaxy NGC 253 (Koribalski, Whiteoak, & Houghton Reference Koribalski, Whiteoak and Houghton1995; Koribalski et al. Reference Koribalski2004), which resides in the Sculptor Group. The radio brightness and large extent of the NGC 253 disc cause minor artifacts over part of the field. For a summary of the ASKAP observations, which were conducted to search for the radio counterpart of the gravitational wave event GW190814 (Abbott et al. 2020),Footnote

b

see Dobie et al. (Reference Dobie2022). The data processing was done with the ASKAPsoft pipeline (Whiting et al. Reference Whiting, Voronkov, Mitchell, Team, Lorente, Shortridge and Wayth2017; Wieringa, Raja, & Ord Reference Wieringa, Raja, Ord, Pizzo, Deul, Mol, de Plaa and Verkouter2020). We combined all eight

![]() $\sim$

10 h integration images after convolving each to a common 13′′ resolution, achieving an average rms noise of

$\sim$

10 h integration images after convolving each to a common 13′′ resolution, achieving an average rms noise of

![]() $\sim$

13

$\sim$

13

![]() $\unicode{x03BC}$

Jy beam

$\unicode{x03BC}$

Jy beam

![]() $^{-1}$

in the artifact-free parts of the overlap region.

$^{-1}$

in the artifact-free parts of the overlap region.

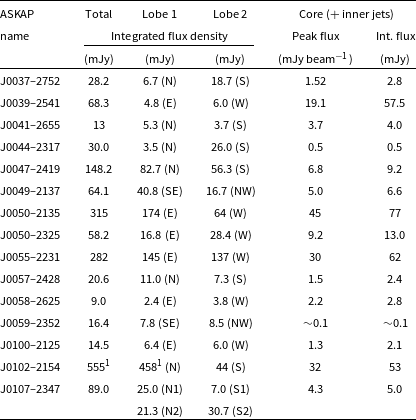

Table 2. ASKAP 944 MHz flux densities of the GRGs listed in Table 1.

![]() $^{1}$

We subtracted 50 mJy for the approximate contribution of the Abell 133 core. It is possible that most of the northern radio emission belongs to the cluster.

$^{1}$

We subtracted 50 mJy for the approximate contribution of the Abell 133 core. It is possible that most of the northern radio emission belongs to the cluster.

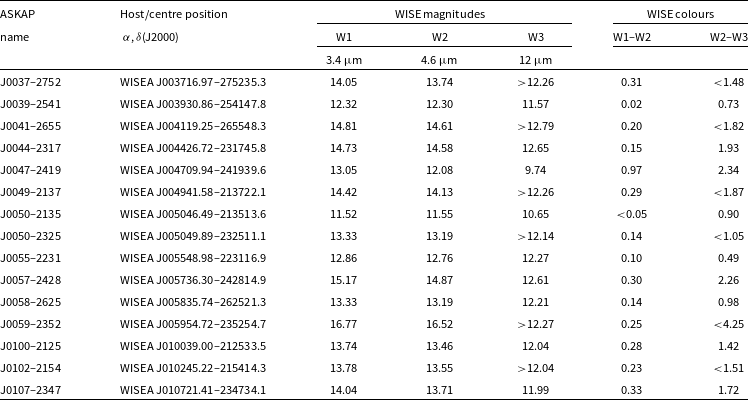

Table 3. WISE magnitudes and colours of the GRG host galaxies listed in Table 1.

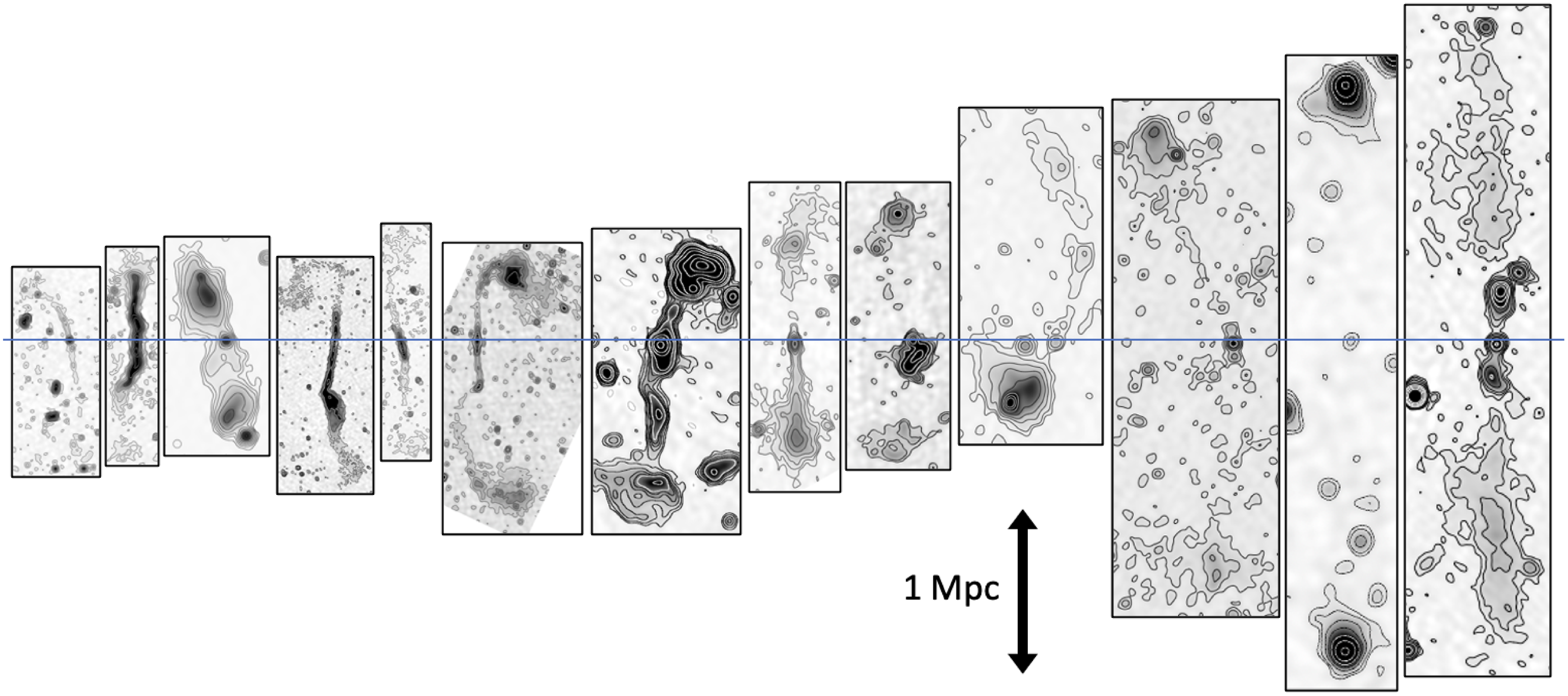

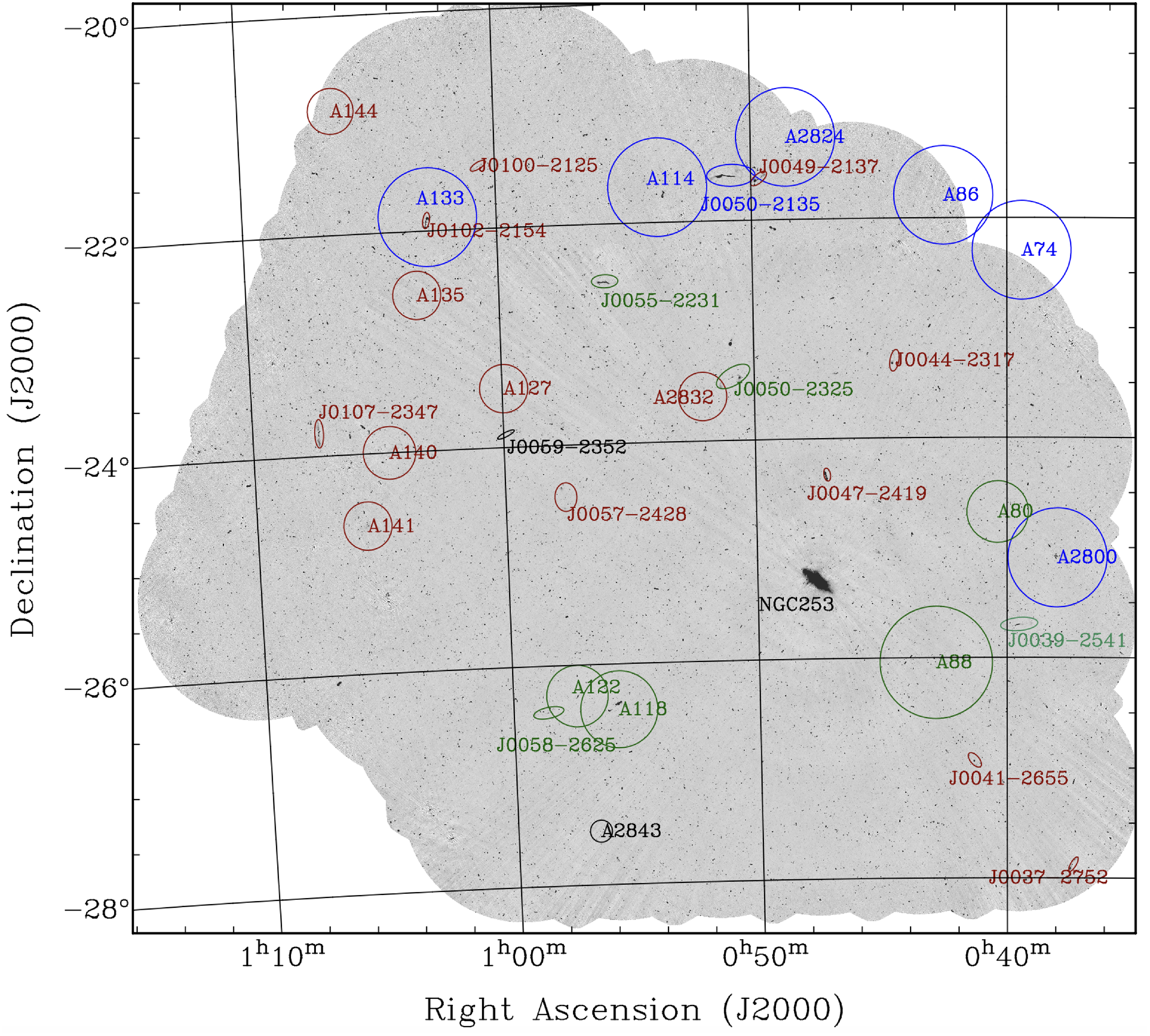

Figure 1. Overview of the ASKAP 944 MHz Sculptor field (resolution 13 arcsec), consisting of a

![]() $7 \times 10$

h square field (PA = 0

$7 \times 10$

h square field (PA = 0

![]() $^\circ$

) and

$^\circ$

) and

![]() $1 \times 10$

h rotated square field (PA = 67

$1 \times 10$

h rotated square field (PA = 67

![]() $.\mkern-4mu^\circ$

5) offset the north-east. The field borders are indicated by grey lines; see also (Dobie et al. Reference Dobie2022, their Figure 1). In the overlap region, which includes a large fraction of the GW190814 location area (Abbott, Abbott, & Abraham Reference Abbott and Abbott2020), the average rms noise is

$.\mkern-4mu^\circ$

5) offset the north-east. The field borders are indicated by grey lines; see also (Dobie et al. Reference Dobie2022, their Figure 1). In the overlap region, which includes a large fraction of the GW190814 location area (Abbott, Abbott, & Abraham Reference Abbott and Abbott2020), the average rms noise is

![]() $\sim$

13

$\sim$

13

![]() $\unicode{x03BC}$

Jy beam

$\unicode{x03BC}$

Jy beam

![]() $^{-1}$

. Residual artifacts from the bright starburst galaxy NGC 253 cause variations of the rms noise across the field. Overlaid are enlarged images of the 15 largest (in terms of angular size) giant radio galaxies in our sample listed in Table 1 (not to scale). The two candidate GRGs are indicted by red frames.

$^{-1}$

. Residual artifacts from the bright starburst galaxy NGC 253 cause variations of the rms noise across the field. Overlaid are enlarged images of the 15 largest (in terms of angular size) giant radio galaxies in our sample listed in Table 1 (not to scale). The two candidate GRGs are indicted by red frames.

We inspected the combined ASKAP fields by eye, carefully stepping through small image sections noting all extended radio galaxies. For each source, we then classify its radio morphology, identify its host galaxy, obtain its redshift, and inspect radio images at other frequencies when available. The procedures employed here are similar to those described in Andernach et al. (Reference Andernach, Jiménez-Andrade and Willis2021), Simonte et al. (Reference Simonte2022), Andernach & Brüggen (Reference Andernach and Brüggen2025) and references therein.

3. Results

Figure 1 shows the

![]() $\sim$

40 deg

$\sim$

40 deg

![]() $^2$

ASKAP field studied here. It consists of a deep field (

$^2$

ASKAP field studied here. It consists of a deep field (

![]() $\sim$

70 h) covering

$\sim$

70 h) covering

![]() $00^\textrm{h}\,37^\textrm{m} \lt$

$00^\textrm{h}\,37^\textrm{m} \lt$

![]() $\alpha$

(J2000)

$\alpha$

(J2000)

![]() $\lt 01^\textrm{h}\,04^\textrm{m}$

and –22

$\lt 01^\textrm{h}\,04^\textrm{m}$

and –22

![]() $^\circ$

25′

$^\circ$

25′

![]() $\lt$

$\lt$

![]() $\delta$

(J2000)

$\delta$

(J2000)

![]() $\lt$

–28

$\lt$

–28

![]() $^\circ$

10′, and a rotated (

$^\circ$

10′, and a rotated (

![]() $\sim$

10 h) field offset to the north-east. Our analysis of the ASKAP data is complemented by optical, infrared, X-ray, and other radio data. Specifically, we make use of the deep multi-band optical images from the Dark Energy Surveys (DES, Dark Energy Survey Collaboration et al. 2016) as well as radio continuum images from the 2–4 GHz Very Large Array Sky Survey (VLASS, Lacy et al. Reference Lacy2020), the 1.4 GHz NRAO VLA Sky Survey (NVSS, Condon et al. Reference Condon1998), the 150 MHz TIFR GMRT Sky Survey (TGSS, Intema et al. Reference Intema, Jagannathan, Mooley and Frail2017), and the 72–231 MHz GaLactic and Extragalactic All-sky Murchison Widefield Array survey (GLEAM, Hurley-Walker et al. Reference Hurley-Walker2017; Hurley-Walker et al. Reference Hurley-Walker2022).

$\sim$

10 h) field offset to the north-east. Our analysis of the ASKAP data is complemented by optical, infrared, X-ray, and other radio data. Specifically, we make use of the deep multi-band optical images from the Dark Energy Surveys (DES, Dark Energy Survey Collaboration et al. 2016) as well as radio continuum images from the 2–4 GHz Very Large Array Sky Survey (VLASS, Lacy et al. Reference Lacy2020), the 1.4 GHz NRAO VLA Sky Survey (NVSS, Condon et al. Reference Condon1998), the 150 MHz TIFR GMRT Sky Survey (TGSS, Intema et al. Reference Intema, Jagannathan, Mooley and Frail2017), and the 72–231 MHz GaLactic and Extragalactic All-sky Murchison Widefield Array survey (GLEAM, Hurley-Walker et al. Reference Hurley-Walker2017; Hurley-Walker et al. Reference Hurley-Walker2022).

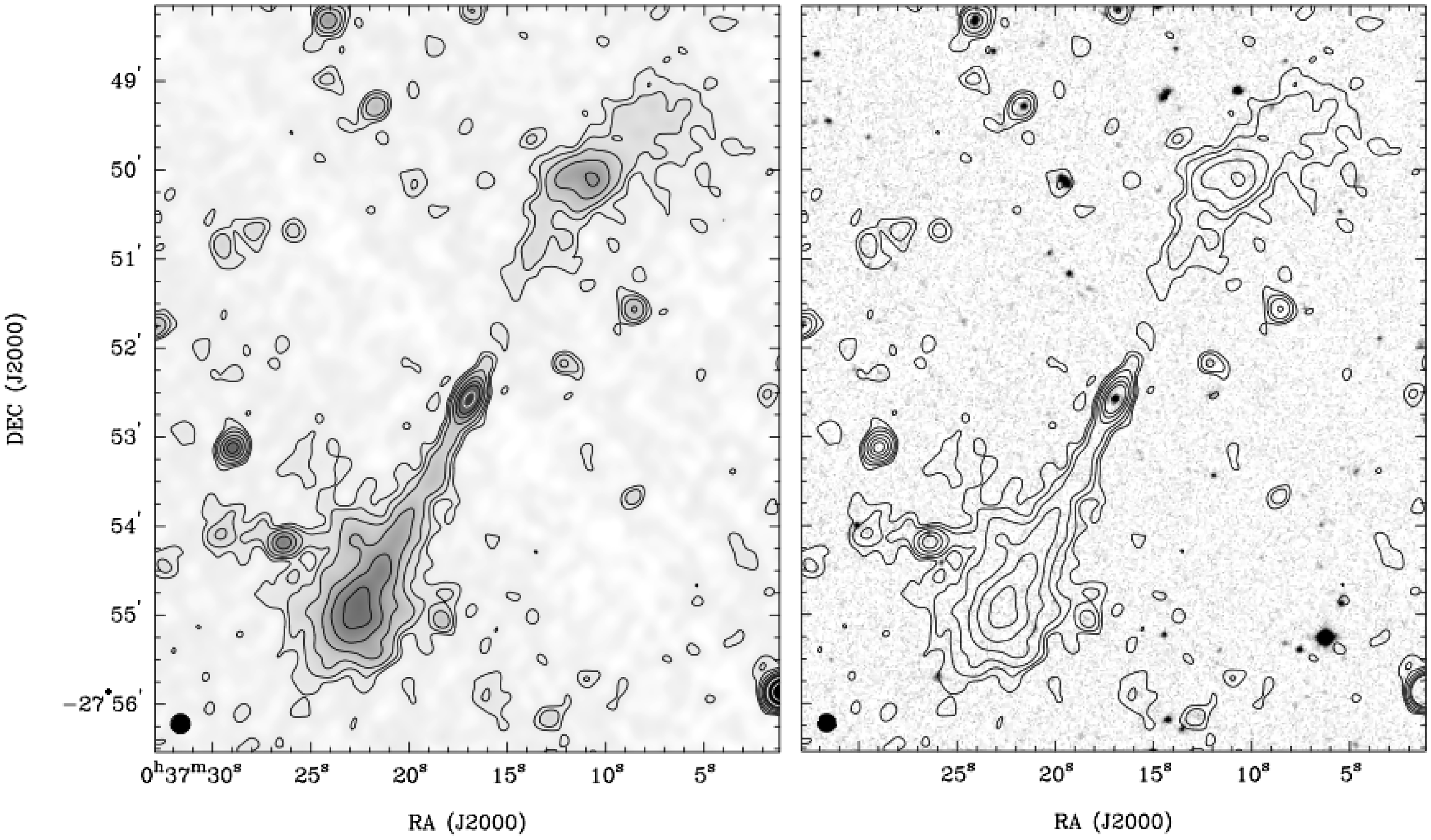

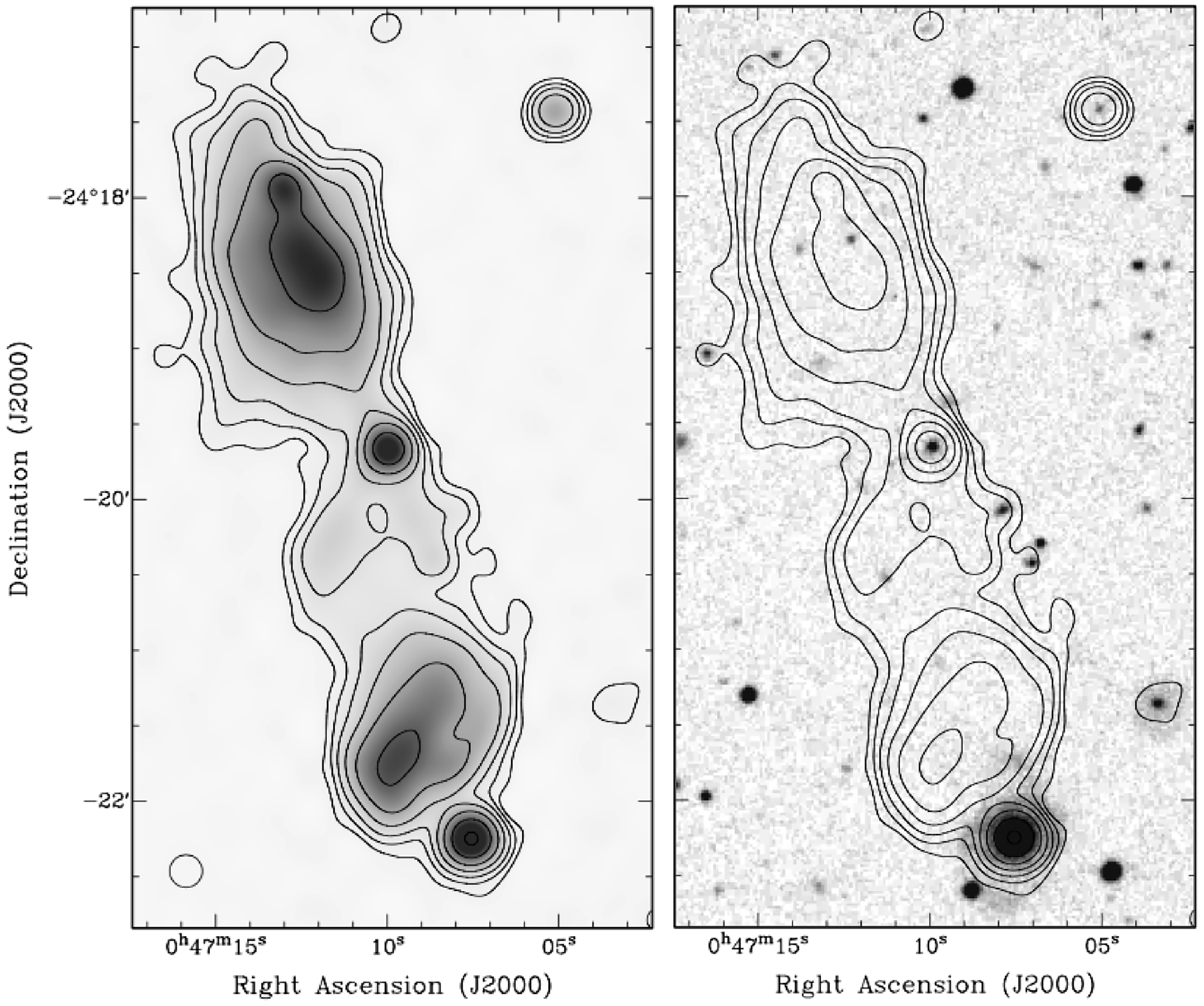

Figure 2. ASKAP J0037–2752 (FR II-type GRG). – Left: ASKAP 944 MHz radio continuum map; the contour levels are 0.04, 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.65, 0.9, 1.3, 3, and 5 mJy beam

![]() $^{-1}$

. – Right: ASKAP radio contours overlaid onto a DSS2 R-band image. The GRG host galaxy is WISEA J003716.97–275235.3 (

$^{-1}$

. – Right: ASKAP radio contours overlaid onto a DSS2 R-band image. The GRG host galaxy is WISEA J003716.97–275235.3 (

![]() $z_{\mathrm{spec}}$

= 0.2389). The ASKAP resolution of 13 arcsec is shown in the bottom left corner.

$z_{\mathrm{spec}}$

= 0.2389). The ASKAP resolution of 13 arcsec is shown in the bottom left corner.

We conducted a by eye search for radio galaxies with large angular sizes, similar to (Lara et al. Reference Lara2001, for NVSS) and (Saripalli et al. Reference Saripalli, Hunstead, Subrahmanyan and Boyce2005, for SUMSS). While our primary focus was on radio structures larger than

![]() $\sim$

5 arcmin, we tried to catalogue all radio sources larger than

$\sim$

5 arcmin, we tried to catalogue all radio sources larger than

![]() $\sim$

1 arcmin. Due to some imaging artifacts in the field, especially around NGC 253 and other bright radio sources, we did not use any source finding tools. No GRGs were catalogued by Kuźmicz et al. (Reference Kuźmicz, Jamrozy, Bronarska, Janda-Boczar and Saikia2018) in this field, and, apart from the nearby, starburst galaxy NGC 253 (Koribalski et al. Reference Koribalski, Whiteoak and Houghton1995, Reference Koribalski2018), only one bright radio galaxy (NVSS J003757–250425) was catalogued by van Velzen et al. (Reference van Velzen, Falcke, Schellart, Nierstenhöfer and Kampert2012). From our sample, only GRG J0055–2231 (LAS = 9.2 arcmin) is listed by Dabhade et al. (Reference Dabhade2020b) and Mostert et al. (Reference Mostert2024) with a LAS estimate of 6.4 arcmin (see Section 3.1).

$\sim$

1 arcmin. Due to some imaging artifacts in the field, especially around NGC 253 and other bright radio sources, we did not use any source finding tools. No GRGs were catalogued by Kuźmicz et al. (Reference Kuźmicz, Jamrozy, Bronarska, Janda-Boczar and Saikia2018) in this field, and, apart from the nearby, starburst galaxy NGC 253 (Koribalski et al. Reference Koribalski, Whiteoak and Houghton1995, Reference Koribalski2018), only one bright radio galaxy (NVSS J003757–250425) was catalogued by van Velzen et al. (Reference van Velzen, Falcke, Schellart, Nierstenhöfer and Kampert2012). From our sample, only GRG J0055–2231 (LAS = 9.2 arcmin) is listed by Dabhade et al. (Reference Dabhade2020b) and Mostert et al. (Reference Mostert2024) with a LAS estimate of 6.4 arcmin (see Section 3.1).

We paid particular attention to large LSB structures such as diffuse, extended radio lobes, cluster halos and relics, as well as odd radio circles.

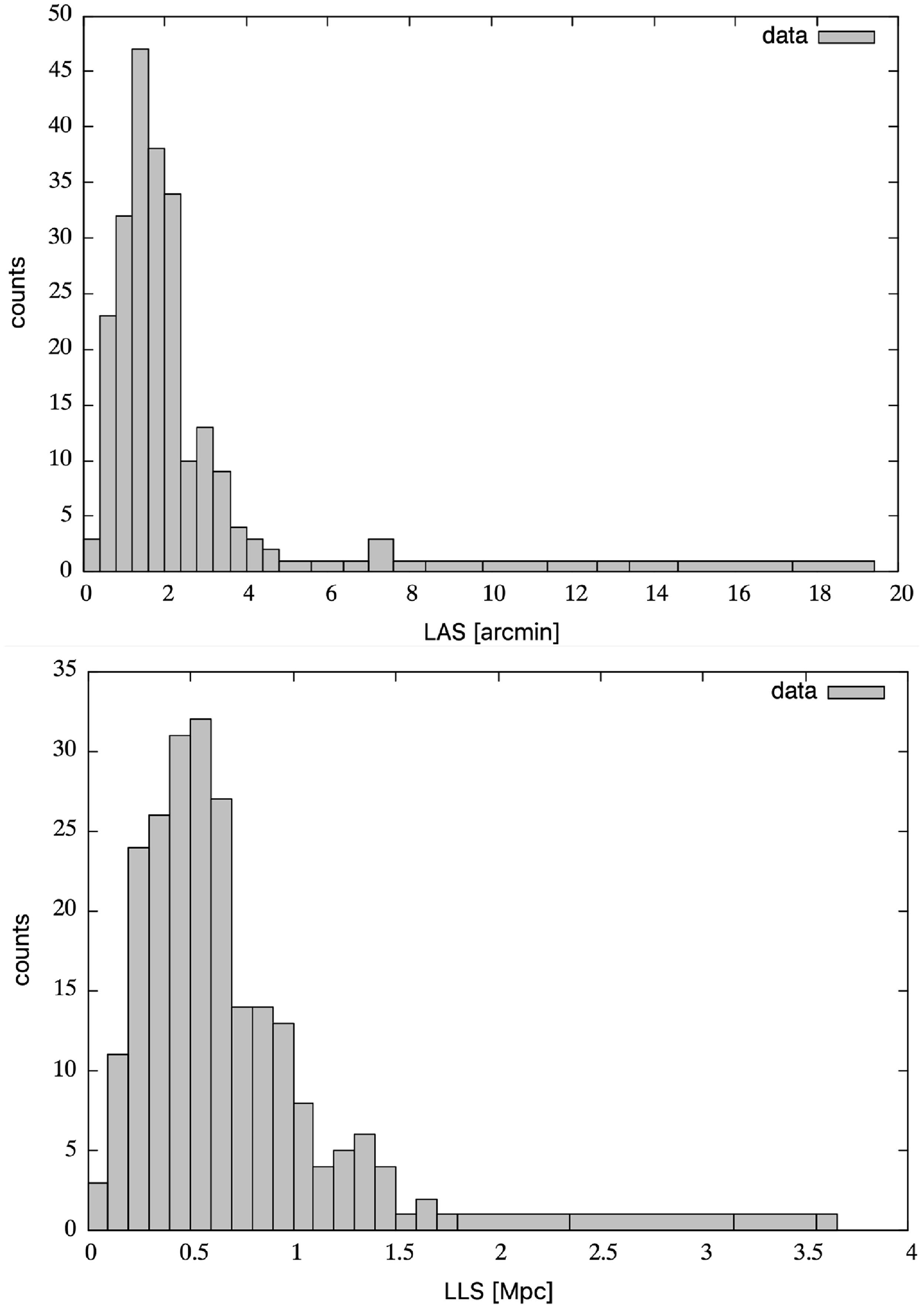

We catalogue 35 giant radio galaxies with LLS

![]() $\gt$

1 Mpc, including four candidates. Furthermore, we catalogue 42 RGs with

$\gt$

1 Mpc, including four candidates. Furthermore, we catalogue 42 RGs with

![]() $0.7 \lt$

LLS

$0.7 \lt$

LLS

![]() $\lt 1.0$

Mpc, including three candidates, and 155 RGs with LLS

$\lt 1.0$

Mpc, including three candidates, and 155 RGs with LLS

![]() $\lt 0.7$

Mpc. These numbers suggest a source density of

$\lt 0.7$

Mpc. These numbers suggest a source density of

![]() $\sim$

0.9 deg

$\sim$

0.9 deg

![]() $^{-2}$

for GRGs

$^{-2}$

for GRGs

![]() $\gt$

1 Mpc and

$\gt$

1 Mpc and

![]() $\sim$

1.9 deg

$\sim$

1.9 deg

![]() $^{-2}$

for those

$^{-2}$

for those

![]() $\gt$

0.7 Mpc. In total, we catalogue 232 RGs (listed in the Appendix), of which 164 (70%) are classified as FR II, 30 are classified as FR I/II, 29 as FR I and nine others.

$\gt$

0.7 Mpc. In total, we catalogue 232 RGs (listed in the Appendix), of which 164 (70%) are classified as FR II, 30 are classified as FR I/II, 29 as FR I and nine others.

3.1. GRGs with large angular sizes

In the following, we discuss in detail the 15 GRGs with the largest angular sizes (LAS

![]() $\ge$

5 arcmin; see Table 1) in the ASKAP Sculptor field. Figures 2–18 show ASKAP images as well as optical R-band images from the Digitized Sky Survey (DSS2), both overlaid with radio contours, as well as a few zoom-in images. For each GRG, we list the most likely host galaxy together with its redshift, the GRG’s projected angular size, its linear size, and its morphological type. Figure 19 shows DES-DR10 optical images of the GRG host galaxies as well as four others. The largest angular size (LAS) of a radio galaxy is measured along a straight line connecting opposite ‘ends’ of the radio source. For FR II sources, we measure the LAS between the centres of the two hotspots. Only for very faint/diffuse lobes do we measure LAS out to the 3

$\ge$

5 arcmin; see Table 1) in the ASKAP Sculptor field. Figures 2–18 show ASKAP images as well as optical R-band images from the Digitized Sky Survey (DSS2), both overlaid with radio contours, as well as a few zoom-in images. For each GRG, we list the most likely host galaxy together with its redshift, the GRG’s projected angular size, its linear size, and its morphological type. Figure 19 shows DES-DR10 optical images of the GRG host galaxies as well as four others. The largest angular size (LAS) of a radio galaxy is measured along a straight line connecting opposite ‘ends’ of the radio source. For FR II sources, we measure the LAS between the centres of the two hotspots. Only for very faint/diffuse lobes do we measure LAS out to the 3

![]() $\sigma$

contour. For bent-tailed sources, we measure the LAS along a straight line between the most separate diametrically opposite emission regions. Because of projection effects, bending of the tails, and surface-brightness sensitivity, the stated GRG extent is nearly always a lower limit. The WISE magnitudes and colours of the GRG hosts are given in Table 2 and the ASKAP 944 MHz total and component flux densities are listed in Table 3.

$\sigma$

contour. For bent-tailed sources, we measure the LAS along a straight line between the most separate diametrically opposite emission regions. Because of projection effects, bending of the tails, and surface-brightness sensitivity, the stated GRG extent is nearly always a lower limit. The WISE magnitudes and colours of the GRG hosts are given in Table 2 and the ASKAP 944 MHz total and component flux densities are listed in Table 3.

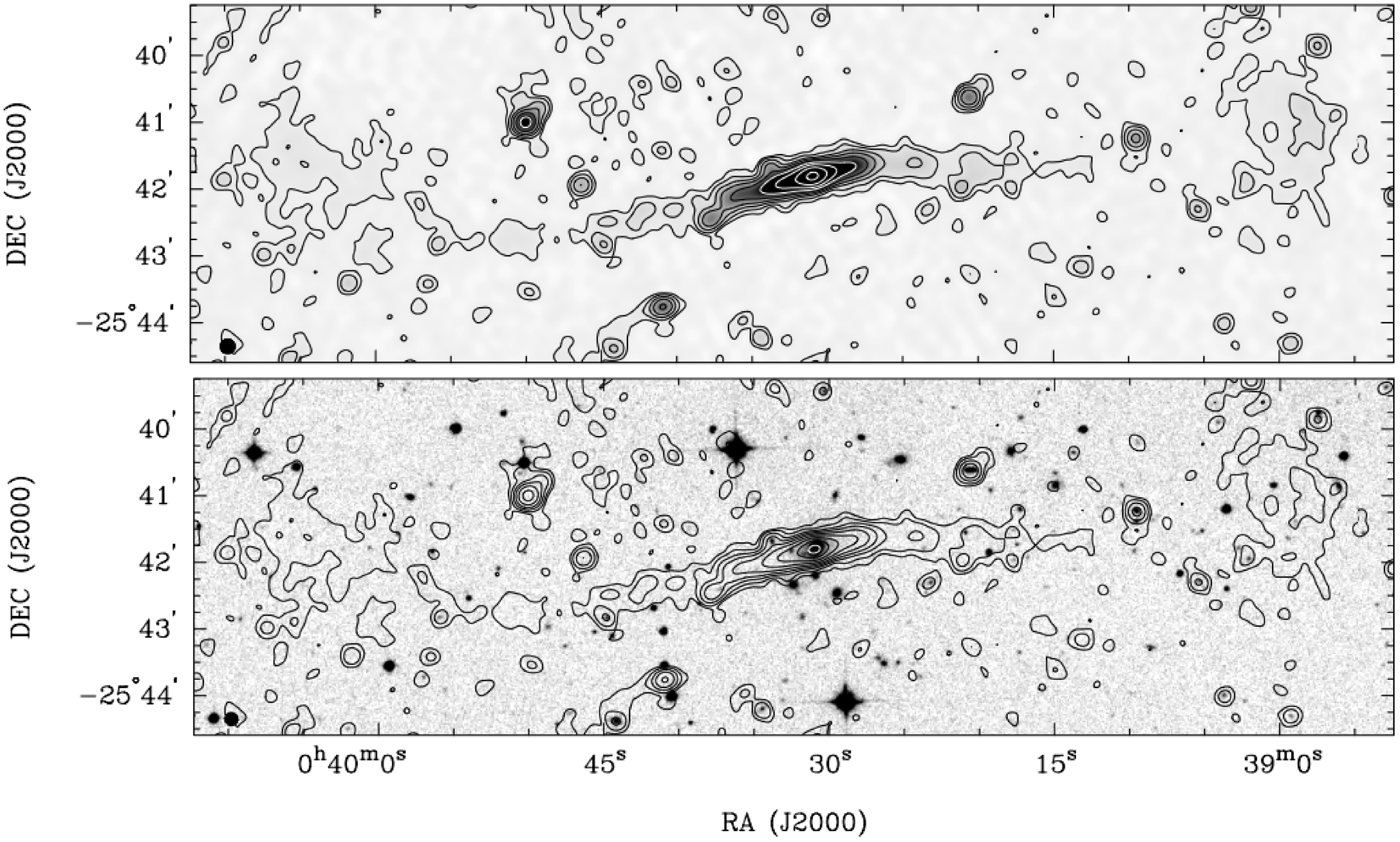

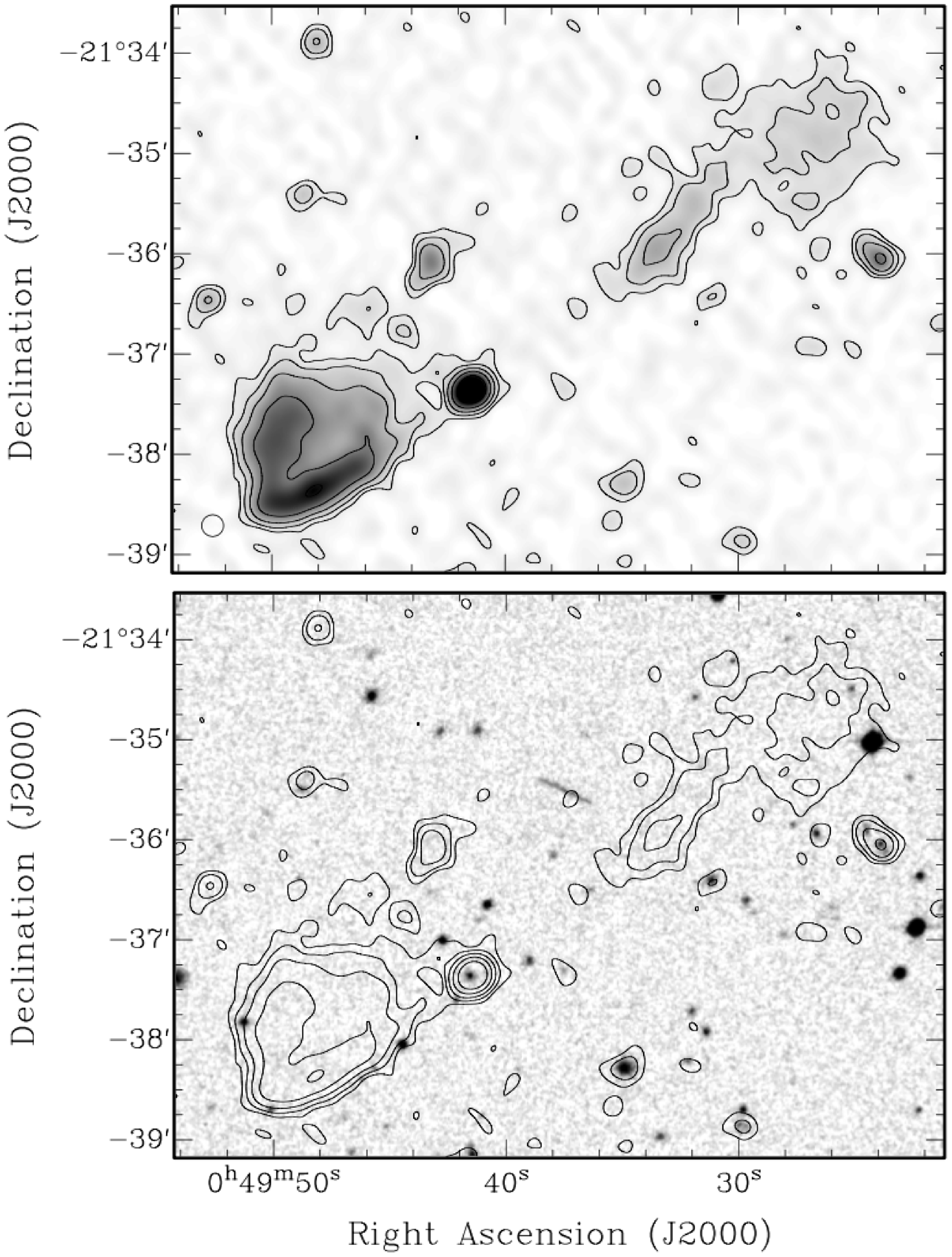

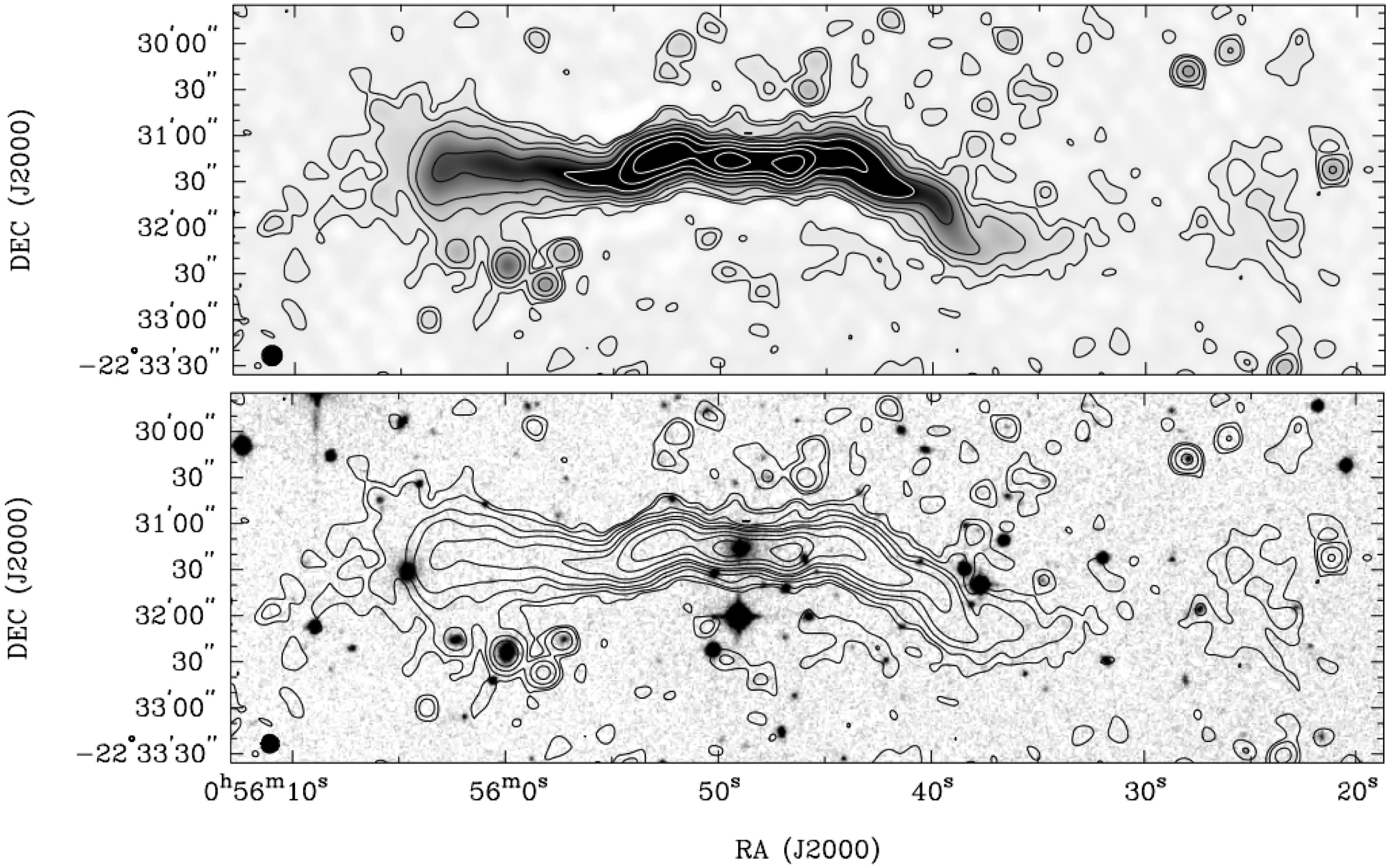

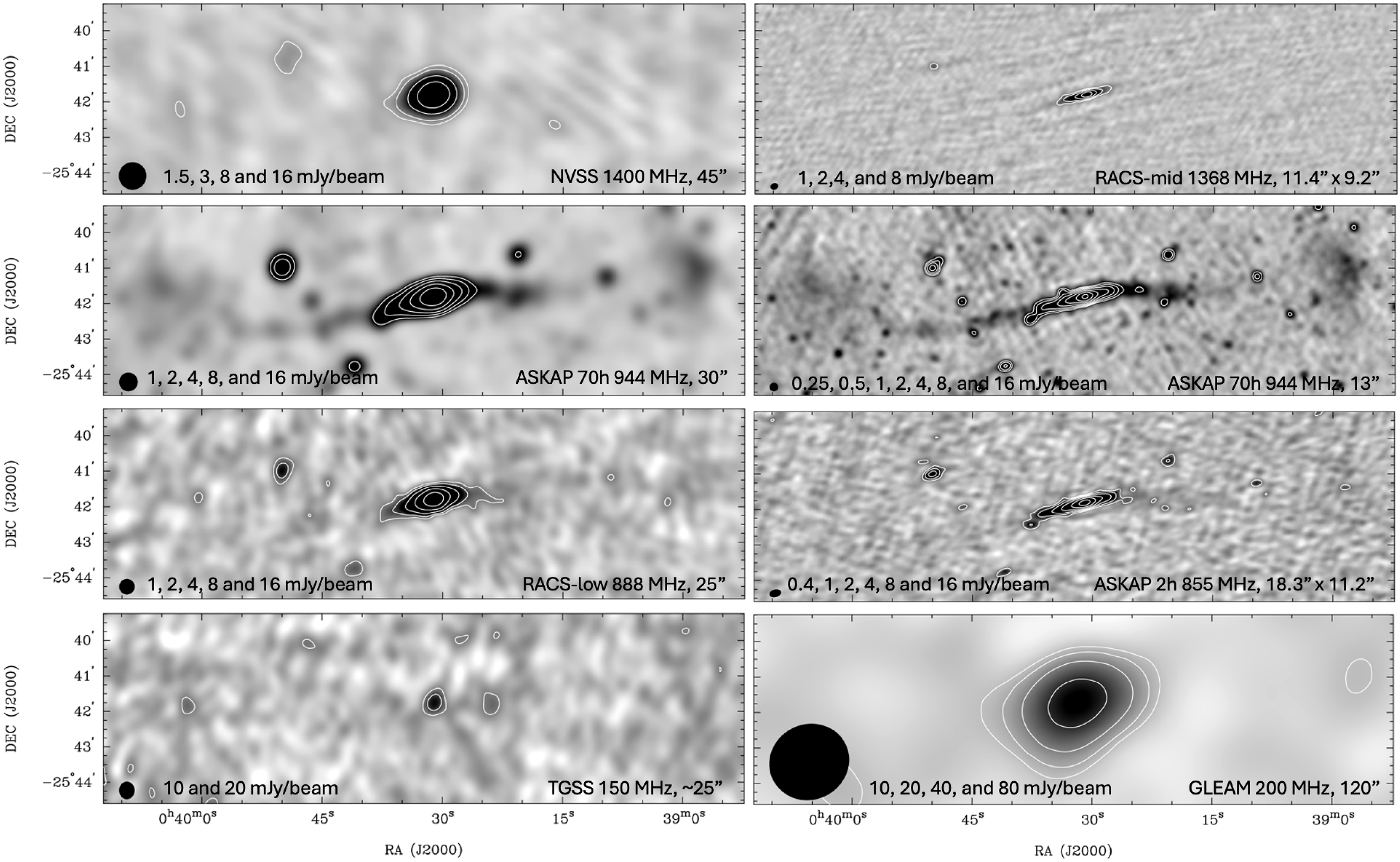

Figure 3. ASKAP J0039–2541 (FR I-type GRG). – Top: ASKAP 944 MHz radio continuum map; the contour levels are 0.03, 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8 and 16 mJy beam

![]() $^{-1}$

. – Bottom: ASKAP radio contours overlaid onto a DSS2 R-band image. The GRG host galaxy is WISEA J003930.86–254147.8 (

$^{-1}$

. – Bottom: ASKAP radio contours overlaid onto a DSS2 R-band image. The GRG host galaxy is WISEA J003930.86–254147.8 (

![]() $z_{\mathrm{spec}}$

= 0.073). The ASKAP resolution of 13 arcsec is shown in the bottom left corner.

$z_{\mathrm{spec}}$

= 0.073). The ASKAP resolution of 13 arcsec is shown in the bottom left corner.

ASKAP J0037–2752 is an FR II-type GRG with a bright core and two extended lobes (LAS = 7.5 arcmin;

![]() $PA \sim 150^\circ$

, see Figure 2). The southern radio lobe, which connects to the core, is significantly brighter than the disconnected, more diffuse northern lobe. The radio core is associated with the galaxy WISEA J003716.97–275235.3 (2MASX J00371697–2752350, LEDA 3199033; DES J003716.97–275235.4) at

$PA \sim 150^\circ$

, see Figure 2). The southern radio lobe, which connects to the core, is significantly brighter than the disconnected, more diffuse northern lobe. The radio core is associated with the galaxy WISEA J003716.97–275235.3 (2MASX J00371697–2752350, LEDA 3199033; DES J003716.97–275235.4) at

![]() $z_{\mathrm{spec}}$

= 0.23887 (2dF, Colless et al. Reference Colless2001). We estimate a linear extent of 1.70 Mpc for the system. The GRG radio core was previously catalogued as NVSS J003717–275242 (

$z_{\mathrm{spec}}$

= 0.23887 (2dF, Colless et al. Reference Colless2001). We estimate a linear extent of 1.70 Mpc for the system. The GRG radio core was previously catalogued as NVSS J003717–275242 (

![]() $2.9 \pm 0.6$

mJy at 1.4 GHz); it is also detected in VLASS. We measure an ASKAP core position of

$2.9 \pm 0.6$

mJy at 1.4 GHz); it is also detected in VLASS. We measure an ASKAP core position of

![]() $\alpha,\delta$

(J2000) =

$\alpha,\delta$

(J2000) =

![]() $00^\textrm{h}\,37^\textrm{m}\,16.95^\textrm{s}$

, –27

$00^\textrm{h}\,37^\textrm{m}\,16.95^\textrm{s}$

, –27

![]() $^\circ$

52′ 34.8″, a 944 MHz peak flux of 1.5 mJy beam

$^\circ$

52′ 34.8″, a 944 MHz peak flux of 1.5 mJy beam

![]() $^{-1}$

and an integrated 944 MHz flux of 2.8 mJy. It is likely the latter value includes radio emission from inner jets. The GRG’s northern (N) and southern (S) lobes were previously catalogued as NVSS J003712–275003 (

$^{-1}$

and an integrated 944 MHz flux of 2.8 mJy. It is likely the latter value includes radio emission from inner jets. The GRG’s northern (N) and southern (S) lobes were previously catalogued as NVSS J003712–275003 (

![]() $15.7 \pm 3.7$

mJy) and NVSS J003722–275445 (

$15.7 \pm 3.7$

mJy) and NVSS J003722–275445 (

![]() $14.7 \pm 3.6$

mJy), respectively. We obtain ASKAP 944 MHz integrated flux densities of 6.7 mJy (N), 18.7 mJy (S) and 28.2 mJy (total).

$14.7 \pm 3.6$

mJy), respectively. We obtain ASKAP 944 MHz integrated flux densities of 6.7 mJy (N), 18.7 mJy (S) and 28.2 mJy (total).

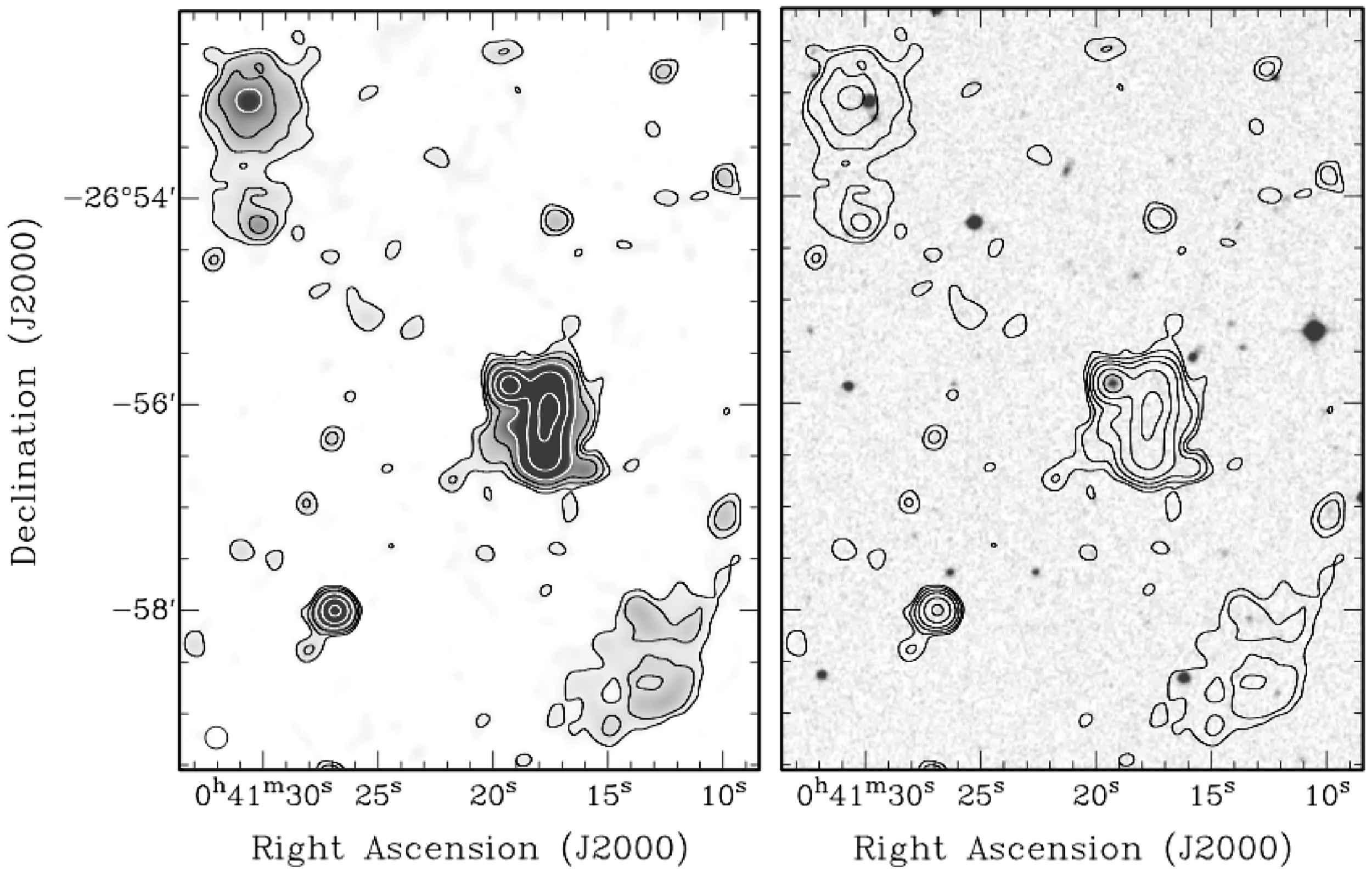

Figure 4. ASKAP J0041–2655 (FR II-type GRG). – Left: ASKAP 944 MHz radio continuum map; the contour levels are 0.06, 0.12, 0.25 mJy beam

![]() $^{-1}$

(black), and 0.5, 1, 1.2, and 2.5 mJy beam

$^{-1}$

(black), and 0.5, 1, 1.2, and 2.5 mJy beam

![]() $^{-1}$

(white). The ASKAP resolution of 13 arcsec is shown in the bottom left corner. – Right: ASKAP radio contours overlaid onto a DSS R-band optical image. The GRG host galaxy is WISEA J004119.25–265548.3 (

$^{-1}$

(white). The ASKAP resolution of 13 arcsec is shown in the bottom left corner. – Right: ASKAP radio contours overlaid onto a DSS R-band optical image. The GRG host galaxy is WISEA J004119.25–265548.3 (

![]() $z_{\mathrm{phot}}$

= 0.232). – Superimposed is another double-lobe radio galaxy (ASKAP J0041–2656, LAS

$z_{\mathrm{phot}}$

= 0.232). – Superimposed is another double-lobe radio galaxy (ASKAP J0041–2656, LAS

![]() $\sim$

1 arcmin;

$\sim$

1 arcmin;

![]() $z_{\mathrm{phot}}$

= 0.713), located south-west of the radio core of the GRG ASKAP J0041–2655.

$z_{\mathrm{phot}}$

= 0.713), located south-west of the radio core of the GRG ASKAP J0041–2655.

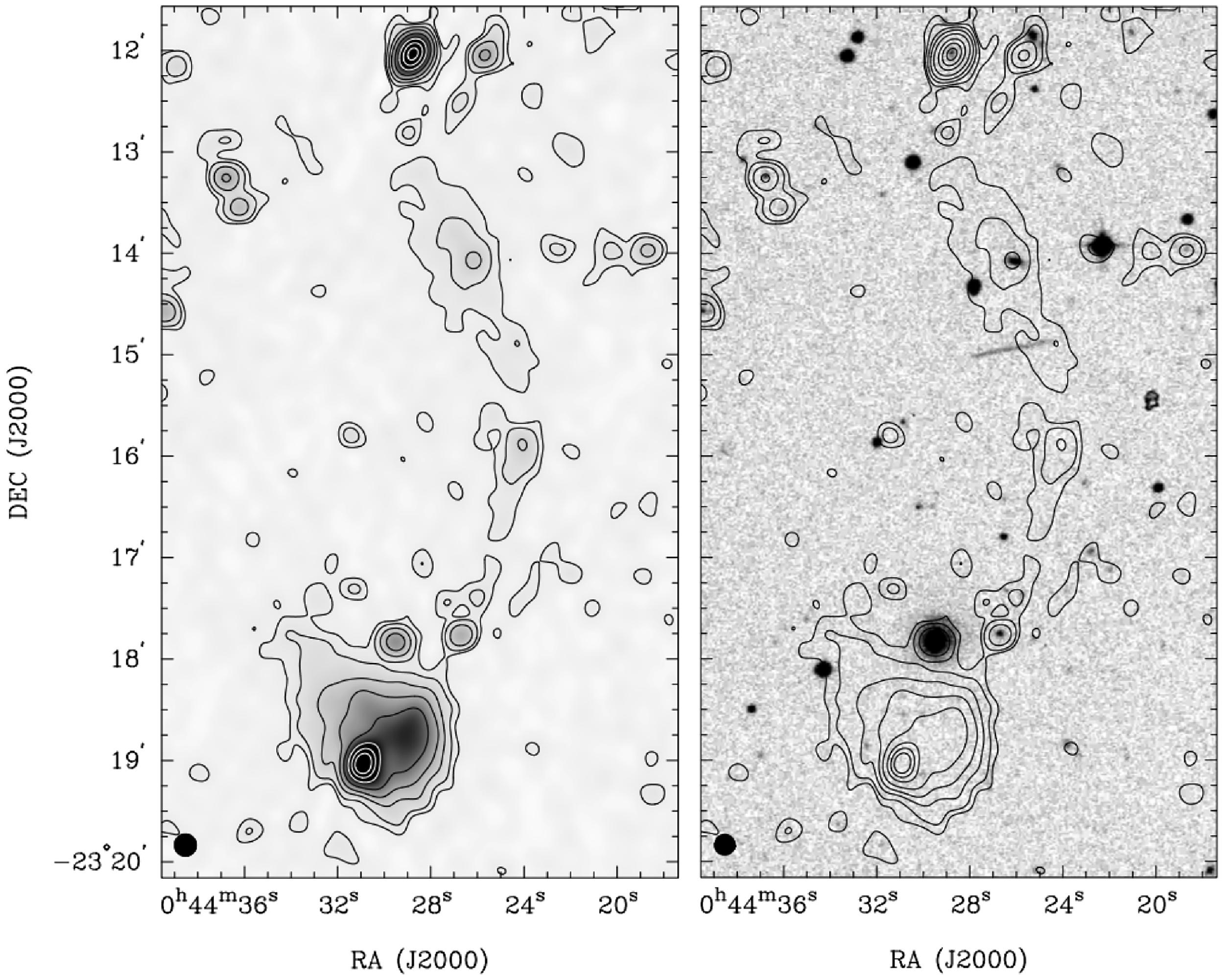

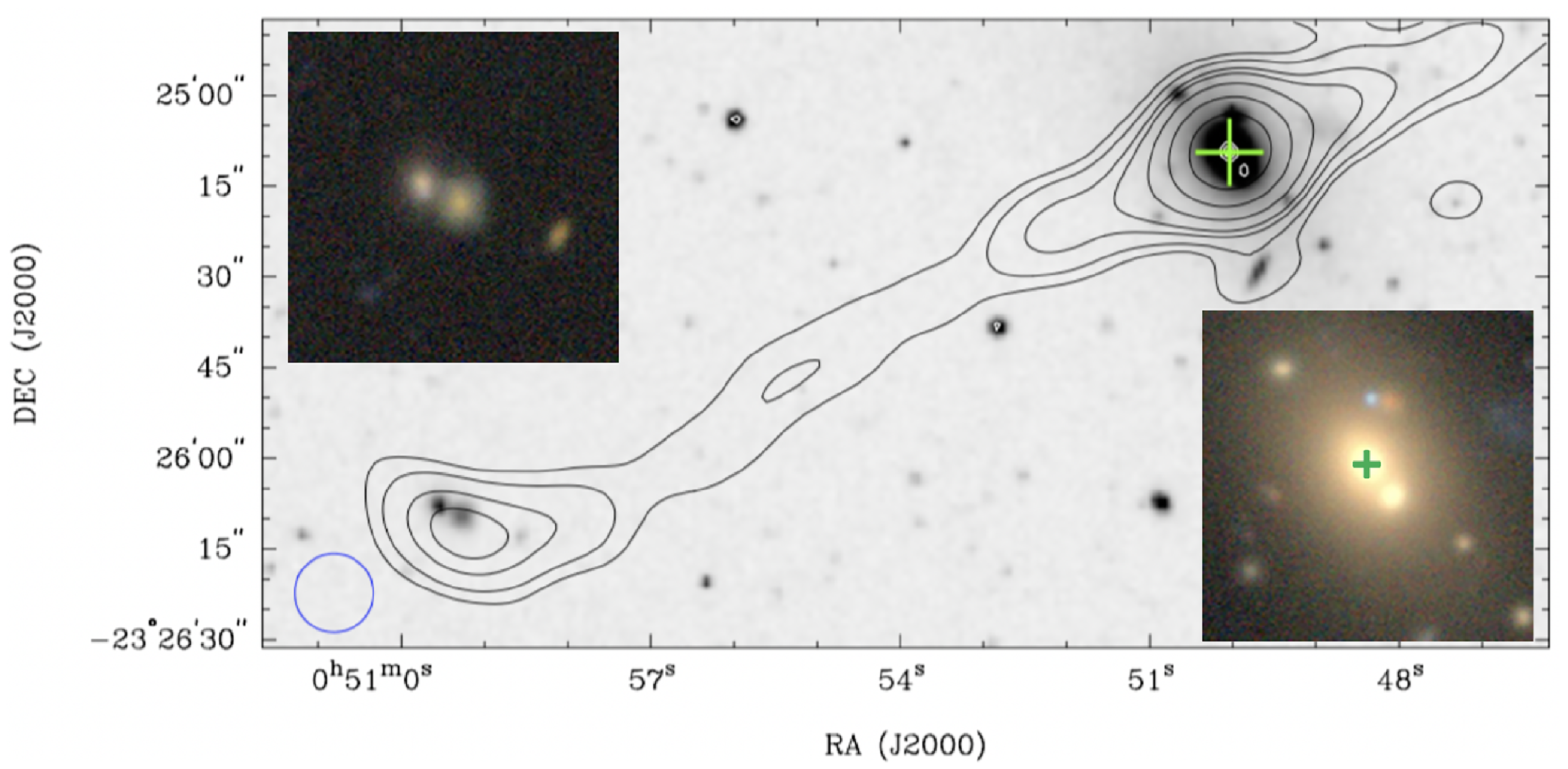

Figure 5. ASKAP J0044–2317 (highly asymmetric HyMoRS-type GRG candidate). – Left: ASKAP 944 MHz radio continuum map; the contour levels are 0.04, 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, and 4 mJy beam

![]() $^{-1}$

. The ASKAP resolution of 13 arcsec is shown in the bottom left corner. – Right: ASKAP radio contours overlaid onto a DSS2 R-band image. The likely GRG host galaxy is WISEA J004426.72–231745.8 (

$^{-1}$

. The ASKAP resolution of 13 arcsec is shown in the bottom left corner. – Right: ASKAP radio contours overlaid onto a DSS2 R-band image. The likely GRG host galaxy is WISEA J004426.72–231745.8 (

![]() $z_{\mathrm{phot}}$

= 0.362). – The prominent foreground spiral galaxy WISEA J004429.50–231749.7 (

$z_{\mathrm{phot}}$

= 0.362). – The prominent foreground spiral galaxy WISEA J004429.50–231749.7 (

![]() $z_{\mathrm{spec}}$

= 0.060), located just north of the southern lobe and east of the GRG host galaxy, is detected with 0.74 mJy.

$z_{\mathrm{spec}}$

= 0.060), located just north of the southern lobe and east of the GRG host galaxy, is detected with 0.74 mJy.

Figure 6. ASKAP J0047–2419 (FR II-type GRG). – Left: ASKAP 944 MHz radio continuum map; the contour levels are 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 mJy beam

![]() $^{-1}$

. The ASKAP resolution of 13 arcsec is shown in the bottom left corner. – Right: ASKAP radio contours overlaid onto a DSS2 R-band image. The GRG host galaxy is WISEA J004709.94–241939.6 (

$^{-1}$

. The ASKAP resolution of 13 arcsec is shown in the bottom left corner. – Right: ASKAP radio contours overlaid onto a DSS2 R-band image. The GRG host galaxy is WISEA J004709.94–241939.6 (

![]() $z_{\mathrm{phot}}$

= 0.270). – Just south of the extended radio lobes we detect a

$z_{\mathrm{phot}}$

= 0.270). – Just south of the extended radio lobes we detect a

![]() $\sim$

10 mJy radio source coincident with the merging galaxy system ESO 474-G026 (

$\sim$

10 mJy radio source coincident with the merging galaxy system ESO 474-G026 (

![]() $z_{\mathrm{spec}}$

= 0.05271). The face-on star-forming spiral LEDA 790836 (

$z_{\mathrm{spec}}$

= 0.05271). The face-on star-forming spiral LEDA 790836 (

![]() $z_{\mathrm{phot}}$

$z_{\mathrm{phot}}$

![]() $\sim$

0.08), located just west of the southern lobe, is also detected (

$\sim$

0.08), located just west of the southern lobe, is also detected (

![]() $\sim$

0.3 mJy). A DES-DR10 optical image of both galaxies is shown in Figure 7, and more details are given in Section 3.1.

$\sim$

0.3 mJy). A DES-DR10 optical image of both galaxies is shown in Figure 7, and more details are given in Section 3.1.

Figure 7. DES-DR10 optical colour image of the galaxies ESO 474-G026 (centre) and LEDA 790836 (top right). The contrast is chosen to show the newly discovered, very faint stellar tails extending to the east and west of the merging galaxy system ESO 474-G026. The ASKAP radio continuum emission of both galaxies is evident in Figure 6, which is centred on the FR II-type GRG ASKAP J0047–2419.

Figure 8. ASKAP J0049–2137 (FR II-type GRG). – Top: ASKAP 944 MHz radio continuum map; the contour levels are 0.12, 0.25, 0.5, 1 and 2 mJy beam

![]() $^{-1}$

. – Bottom: ASKAP radio contours overlaid onto a DSS2 R-band image. The GRG host galaxy is WISEA J004941.58–213722.1 (

$^{-1}$

. – Bottom: ASKAP radio contours overlaid onto a DSS2 R-band image. The GRG host galaxy is WISEA J004941.58–213722.1 (

![]() $z_{\mathrm{phot}}$

= 0.233). The ASKAP resolution of 13 arcsec is shown in the bottom left.

$z_{\mathrm{phot}}$

= 0.233). The ASKAP resolution of 13 arcsec is shown in the bottom left.

ASKAP J0039–2541 is an FR I-type GRG with a bright core, inner jets and very faint relic lobes spanning 15.5 arcmin from east to west (see Figure 3). Its radio core is associated with the galaxy WISEA J003930.86–254147.8 (2MASX J00393086–2541483, DES J003930.85–254147.8) at

![]() $z_{\mathrm{spec}}$

= 0.07297 (2dF, Colless et al. Reference Colless2001). We estimate a linear extent of 1.29 Mpc for the system. The GRG radio core was previously catalogued as NVSS J003931–254149 (

$z_{\mathrm{spec}}$

= 0.07297 (2dF, Colless et al. Reference Colless2001). We estimate a linear extent of 1.29 Mpc for the system. The GRG radio core was previously catalogued as NVSS J003931–254149 (

![]() $40.1 \pm 1.6$

mJy at 1.4 GHz); it is also detected in TGSS and VLASS. We measure an ASKAP core position of

$40.1 \pm 1.6$

mJy at 1.4 GHz); it is also detected in TGSS and VLASS. We measure an ASKAP core position of

![]() $\alpha,\delta$

(J2000) =

$\alpha,\delta$

(J2000) =

![]() $00^\textrm{h}\,39^\textrm{m}\,31.0^\textrm{s}$

, –25

$00^\textrm{h}\,39^\textrm{m}\,31.0^\textrm{s}$

, –25

![]() $^\circ$

41′ 48.6″, a 944 MHz peak flux of 19.1 mJy beam

$^\circ$

41′ 48.6″, a 944 MHz peak flux of 19.1 mJy beam

![]() $^{-1}$

and a total integrated 944 MHz flux of 68.3 mJy.

$^{-1}$

and a total integrated 944 MHz flux of 68.3 mJy.

ASKAP J0041–2655 is an FR II-type GRG with a radio core and two relic lobes (LAS = 7.3 arcmin, see Figure 4). Its likely host galaxy is WISEA J004119.25–265548.3 (DES J004119.25–265548.1) with

![]() $z_{\mathrm{phot}}$

= 0.232, suggesting LLS = 1.62 Mpc. Just south-west of its radio core is another, much smaller double-lobed radio galaxy (ASKAP J0041–2656, also catalogued as NVSS J004118–265603) with LAS

$z_{\mathrm{phot}}$

= 0.232, suggesting LLS = 1.62 Mpc. Just south-west of its radio core is another, much smaller double-lobed radio galaxy (ASKAP J0041–2656, also catalogued as NVSS J004118–265603) with LAS

![]() $\sim$

1 arcmin and host galaxy WISEA J004118.07–265601.8 (

$\sim$

1 arcmin and host galaxy WISEA J004118.07–265601.8 (

![]() $z_{\mathrm{phot}}$

= 0.713); we derive LLS = 430 kpc. We find no X-ray emission that would hint at a cluster environment. We measure the following flux densities for ASKAP J0041–2655:

$z_{\mathrm{phot}}$

= 0.713); we derive LLS = 430 kpc. We find no X-ray emission that would hint at a cluster environment. We measure the following flux densities for ASKAP J0041–2655:

![]() $\sim$

4 mJy (core), 5.3 mJy (N), 3.7 mJy (S), and 13 mJy (total). The radio core is clearly detected in VLASS, showing a possible N–S extension.

$\sim$

4 mJy (core), 5.3 mJy (N), 3.7 mJy (S), and 13 mJy (total). The radio core is clearly detected in VLASS, showing a possible N–S extension.

ASKAP J0044–2317 is a GRG candidate with LAS

![]() $\sim$

6.0 arcmin (see Figure 5). Its near circular southern lobe (S) has a bright hotspot, while its northern lobe (N) is long, narrow and bent (extending to

$\sim$

6.0 arcmin (see Figure 5). Its near circular southern lobe (S) has a bright hotspot, while its northern lobe (N) is long, narrow and bent (extending to

![]() $\delta$

=

$\delta$

=

![]() $-23^\circ$

13′ 15″), resulting in a very asymmetric appearance. We suggest it is a HyMoRS candidate with likely host galaxy WISEA J004426.72–231745.8 (DES J004426.71–231745.7). Based on

$-23^\circ$

13′ 15″), resulting in a very asymmetric appearance. We suggest it is a HyMoRS candidate with likely host galaxy WISEA J004426.72–231745.8 (DES J004426.71–231745.7). Based on

![]() $z_{\mathrm{phot}}$

= 0.362, we derive LLS = 1.82 Mpc. We measure flux densities of 26.0 mJy (S), 3.5 mJy (N), 0.5 mJy (core), and 30.0 mJy (total). The southern lobe was already catalogued as NVSS J004429–231829, but is resolved out in VLASS. The nearest known cluster is WHL J004347.8–231714 at

$z_{\mathrm{phot}}$

= 0.362, we derive LLS = 1.82 Mpc. We measure flux densities of 26.0 mJy (S), 3.5 mJy (N), 0.5 mJy (core), and 30.0 mJy (total). The southern lobe was already catalogued as NVSS J004429–231829, but is resolved out in VLASS. The nearest known cluster is WHL J004347.8–231714 at

![]() $z_{\mathrm{phot}}$

= 0.395 (Wen, Han, & Liu Reference Wen, Han and Liu2012).

$z_{\mathrm{phot}}$

= 0.395 (Wen, Han, & Liu Reference Wen, Han and Liu2012).

A faint foreground galaxy is coincident with the brightest part of the northern-most lobe (

![]() $\delta$

=

$\delta$

=

![]() $-23^\circ$

14′,

$-23^\circ$

14′,

![]() $z_{\mathrm{phot}}$

$z_{\mathrm{phot}}$

![]() $\sim$

0.15). Another prominent foreground spiral (

$\sim$

0.15). Another prominent foreground spiral (

![]() $z_{\mathrm{spec}}$

= 0.060, Jones et al. Reference Jones2009) is detected just north of the southern lobe.

$z_{\mathrm{spec}}$

= 0.060, Jones et al. Reference Jones2009) is detected just north of the southern lobe.

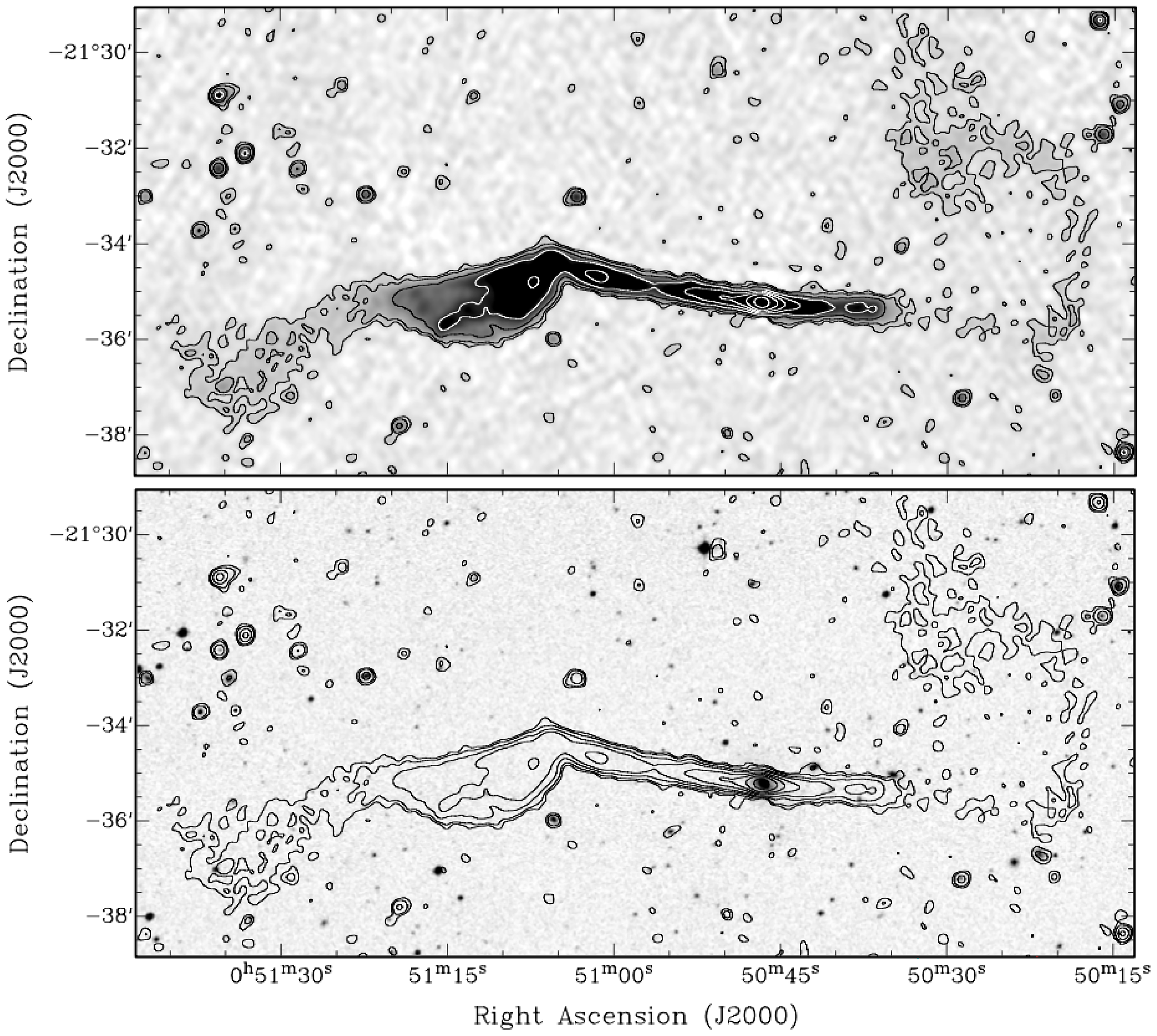

Figure 9. ASKAP J0050–2135 (FR I-type GRG). – Top: ASKAP 944 MHz radio continuum map; the contour levels are 0.1, 0.2, 0.5 mJy beam

![]() $^{-1}$

(black), 1, 2.5, 5, 10 and 25.0 mJy beam

$^{-1}$

(black), 1, 2.5, 5, 10 and 25.0 mJy beam

![]() $^{-1}$

(white). – Bottom: ASKAP radio contours (all black) overlaid onto a DSS2 R-band image. The GRG host galaxy is WISEA J005046.49–213513.6 (

$^{-1}$

(white). – Bottom: ASKAP radio contours (all black) overlaid onto a DSS2 R-band image. The GRG host galaxy is WISEA J005046.49–213513.6 (

![]() $z_{\mathrm{spec}}$

= 0.05760). The ASKAP resolution of 13 arcsec is shown in the bottom left corner.

$z_{\mathrm{spec}}$

= 0.05760). The ASKAP resolution of 13 arcsec is shown in the bottom left corner.

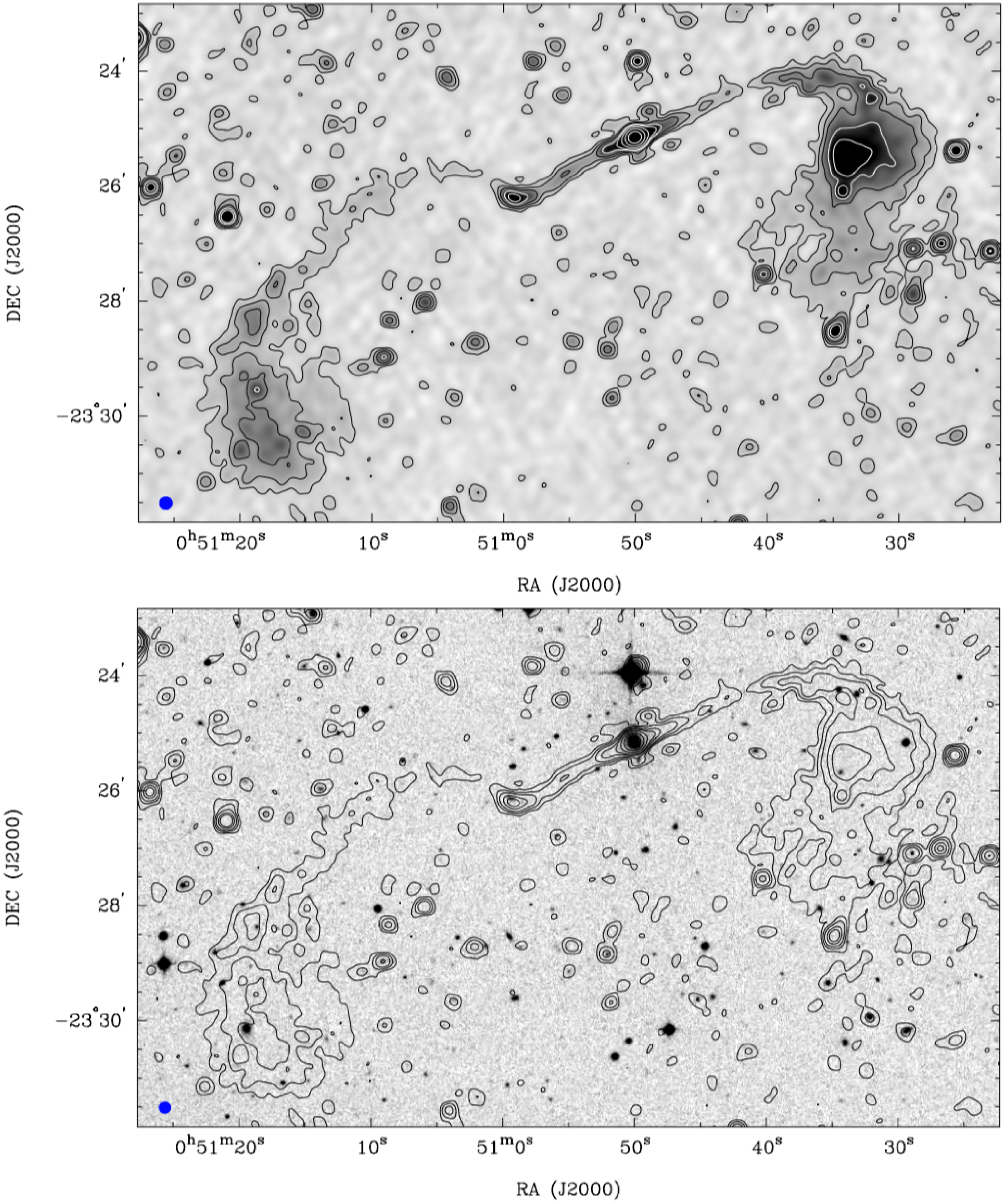

Figure 10. ASKAP J0050–2325 (FR II-type GRG). – Top: ASKAP 944 MHz radio continuum map; the contour levels are 0.03, 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 1.2, 2.5 and 5.0 mJy beam

![]() $^{-1}$

. – Bottom: ASKAP radio contours overlaid onto a DSS2 R-band image. The GRG host galaxy is WISEA J005049.89–232511.1 (

$^{-1}$

. – Bottom: ASKAP radio contours overlaid onto a DSS2 R-band image. The GRG host galaxy is WISEA J005049.89–232511.1 (

![]() $z_{\mathrm{spec}}$

= 0.11137). The ASKAP resolution of 13 arcsec is shown in the bottom left corner.

$z_{\mathrm{spec}}$

= 0.11137). The ASKAP resolution of 13 arcsec is shown in the bottom left corner.

ASKAP J0047–2419 is an FR II-type GRG with bright radio lobes extending over 5.0 arcmin (see Figure 6) corresponding to LLS = 1.24 Mpc at the adopted host galaxy (WISEA J004709.94–241939.6, DES J004709.93–241939.5) redshift of

![]() $z_{\mathrm{phot}}$

=

$z_{\mathrm{phot}}$

=

![]() $0.270 \pm 0.038$

(Zou et al. Reference Zou, Gao, Zhou and Kong2019). Faint optical tails are detected in DES-DR10 around the host galaxy, most prominent to the south-east. The galaxy’s extreme WISE colours led (Flesch Reference Flesch2015) to consider it a quasar at

$0.270 \pm 0.038$

(Zou et al. Reference Zou, Gao, Zhou and Kong2019). Faint optical tails are detected in DES-DR10 around the host galaxy, most prominent to the south-east. The galaxy’s extreme WISE colours led (Flesch Reference Flesch2015) to consider it a quasar at

![]() $z \sim 0.3$

; they also note an associated X-ray source XMMSL J004710.0–241939. The ASKAP flux measurements are listed in Table 2. VLASS 3 GHz images show a hint of radio emission from inner jets, extended approximately N–S. The radio source is also detected in TGSS at 150 MHz, and NVSS–TGSS spectral index maps are available, showing

$z \sim 0.3$

; they also note an associated X-ray source XMMSL J004710.0–241939. The ASKAP flux measurements are listed in Table 2. VLASS 3 GHz images show a hint of radio emission from inner jets, extended approximately N–S. The radio source is also detected in TGSS at 150 MHz, and NVSS–TGSS spectral index maps are available, showing

![]() $\alpha = -0.8 \pm 0.3$

. See Spavone et al. (Reference Spavone2012) for an NVSS image of the GRG.

$\alpha = -0.8 \pm 0.3$

. See Spavone et al. (Reference Spavone2012) for an NVSS image of the GRG.

South of ASKAP J0047–2419, we detect a

![]() $\sim$

10 mJy radio source coincident with the merging galaxy system ESO 474-G026 (

$\sim$

10 mJy radio source coincident with the merging galaxy system ESO 474-G026 (

![]() $z_{\mathrm{spec}}$

= 0.05271, Galletta, Sage, & Sparke Reference Galletta, Sage and Sparke1997). The deep DES-DR10 optical image (see Figure 7) highlights the merger’s spectacular stellar rings (Reshetnikov et al. Reference Reshetnikov2005; Spavone et al. Reference Spavone2012) as well as two previously unknown broad tails of extremely low-surface brightness curving to the east and west, together spanning

$z_{\mathrm{spec}}$

= 0.05271, Galletta, Sage, & Sparke Reference Galletta, Sage and Sparke1997). The deep DES-DR10 optical image (see Figure 7) highlights the merger’s spectacular stellar rings (Reshetnikov et al. Reference Reshetnikov2005; Spavone et al. Reference Spavone2012) as well as two previously unknown broad tails of extremely low-surface brightness curving to the east and west, together spanning

![]() $\sim$

3 arcmin. Reshetnikov et al. (Reference Reshetnikov2005) derive an H i mass of

$\sim$

3 arcmin. Reshetnikov et al. (Reference Reshetnikov2005) derive an H i mass of

![]() $2 \times10^{10}$

M

$2 \times10^{10}$

M

![]() $_{\odot}$

and a star-formation rate of 43 M

$_{\odot}$

and a star-formation rate of 43 M

![]() $_{\odot}$

yr

$_{\odot}$

yr

![]() $^{-1}$

for ESO 474-G026. High-resolution VLASS images reveal a radio core plus faint bi-polar jets aligned approximately N–S, hinting at a central active galactic nucleus (AGN). Within the uncertainties, the two VLASS epochs show the same source morphology and flux densities. ESO 474-G026’s location and redshift make it a possible host of GW190814. Major merger systems like ESO 474-G026 have much increased star formation rates compared to isolated galaxies (Mihos & Hernquist Reference Mihos and Hernquist1996; Hopkins et al. Reference Hopkins2013; Moreno et al. Reference Moreno2021) and contain large numbers of young star clusters, which are ideal locations for BH–BH and BH–NS mergers (e.g. Ziosi et al. Reference Ziosi, Mapelli, Branchesi and Tormen2014; Di Carlo et al. Reference Di Carlo2020; Mandel & Farmer Reference Mandel and Farmer2022). As a consequence, stellar-mass mergers detected by LIGO are more likely to occur in massive, merging galaxies than isolated galaxies. Since Dobie et al. (Reference Dobie2021) find no radio afterglow in the ASKAP data, they suggest ESO 474-G026 is unlikely the GW190814 counterpart.

$^{-1}$

for ESO 474-G026. High-resolution VLASS images reveal a radio core plus faint bi-polar jets aligned approximately N–S, hinting at a central active galactic nucleus (AGN). Within the uncertainties, the two VLASS epochs show the same source morphology and flux densities. ESO 474-G026’s location and redshift make it a possible host of GW190814. Major merger systems like ESO 474-G026 have much increased star formation rates compared to isolated galaxies (Mihos & Hernquist Reference Mihos and Hernquist1996; Hopkins et al. Reference Hopkins2013; Moreno et al. Reference Moreno2021) and contain large numbers of young star clusters, which are ideal locations for BH–BH and BH–NS mergers (e.g. Ziosi et al. Reference Ziosi, Mapelli, Branchesi and Tormen2014; Di Carlo et al. Reference Di Carlo2020; Mandel & Farmer Reference Mandel and Farmer2022). As a consequence, stellar-mass mergers detected by LIGO are more likely to occur in massive, merging galaxies than isolated galaxies. Since Dobie et al. (Reference Dobie2021) find no radio afterglow in the ASKAP data, they suggest ESO 474-G026 is unlikely the GW190814 counterpart.

ASKAP J0049–2137 is an FR II-type remnant GRG with host galaxy WISEA J004941.58–213722.1 (

![]() $z_{\mathrm{phot}}$

= 0.233) and LAS = 7.2 arcmin, suggesting LLS = 1.59 Mpc. The GRG has a very asymmetric appearance (see Figure 8). Its bright SE lobe extends

$z_{\mathrm{phot}}$

= 0.233) and LAS = 7.2 arcmin, suggesting LLS = 1.59 Mpc. The GRG has a very asymmetric appearance (see Figure 8). Its bright SE lobe extends

![]() $\sim$

2.5 arcmin from the compact core and it appears to be bent backwards, while the NW lobe is fainter and extends nearly 5 arcmin. We measure ASKAP flux densities of 7 mJy (core), 38 mJy (SE lobe), 16 mJy (NW lobe), and 61 mJy (total). The core is detected in VLASS and NVSS images, while the SE lobe is only seen in NVSS.

$\sim$

2.5 arcmin from the compact core and it appears to be bent backwards, while the NW lobe is fainter and extends nearly 5 arcmin. We measure ASKAP flux densities of 7 mJy (core), 38 mJy (SE lobe), 16 mJy (NW lobe), and 61 mJy (total). The core is detected in VLASS and NVSS images, while the SE lobe is only seen in NVSS.

ASKAP J0050–2135 is an asymmetric FR I-type GRG with LAS = 18 arcmin; see Figure 9. Bipolar jets emerge from its elliptical host galaxy, WISEA J005046.49–213513.6 (

![]() $z_{\mathrm{spec}}$

= 0.05760, Jones et al. Reference Jones2009). The eastern jet/tail is much brighter and longer, at least in projection, than the western jet/tail. It bends (

$z_{\mathrm{spec}}$

= 0.05760, Jones et al. Reference Jones2009). The eastern jet/tail is much brighter and longer, at least in projection, than the western jet/tail. It bends (

![]() $\sim$

45

$\sim$

45

![]() $^\circ$

) and broadens after

$^\circ$

) and broadens after

![]() $\sim$

4 arcmin, with remarkably sharp boundaries, before ending in a faint patch of emission. A similar kink is also seen in the Barbell GRG (Dabhade et al. Reference Dabhade2022). The short western jet of ASKAP J0050–2135 fades after 2–3 arcmin and curves to the north, then back east to form a hook. The GRG’s LLS is 1.20 Mpc. It is located between two clusters, Abell 114 and Abell 2824 at

$\sim$

4 arcmin, with remarkably sharp boundaries, before ending in a faint patch of emission. A similar kink is also seen in the Barbell GRG (Dabhade et al. Reference Dabhade2022). The short western jet of ASKAP J0050–2135 fades after 2–3 arcmin and curves to the north, then back east to form a hook. The GRG’s LLS is 1.20 Mpc. It is located between two clusters, Abell 114 and Abell 2824 at

![]() $z_{\mathrm{spec}}$

= 0.0587 and 0.0582 (Struble & Rood Reference Struble and Rood1999), respectively, which are part of a filament in the Pisces-Cetus supercluster (Porter & Raychaudhury Reference Porter and Raychaudhury2005).

$z_{\mathrm{spec}}$

= 0.0587 and 0.0582 (Struble & Rood Reference Struble and Rood1999), respectively, which are part of a filament in the Pisces-Cetus supercluster (Porter & Raychaudhury Reference Porter and Raychaudhury2005).

The radio core and eastern jet are also detected in NVSS, TGSS and GLEAM. The TGSS-NVSS spectral index mapFootnote

c

(de Gasperin, Intema, & Frail Reference de Gasperin, Intema and Frail2018) shows

![]() $\alpha \sim -0.3$

in the inner few arcminutes and slighter steeper values to the east before and after the sharp bend. VLASS reveals inner jets (

$\alpha \sim -0.3$

in the inner few arcminutes and slighter steeper values to the east before and after the sharp bend. VLASS reveals inner jets (

![]() ${\lt}$

30 arcsec in length), with the eastern jet much brighter than the western one.

${\lt}$

30 arcsec in length), with the eastern jet much brighter than the western one.

ASKAP J0050–2325 is a spectacular FR II-type wide-angle tail (WAT) radio galaxy consisting of a radio core, two inner jets and two diffuse, bent lobes (see Figure 10). The optical counterpart of the radio core is clearly identified as DES J005050.02–232509.3 (WISEA J005049.89–232511.1, 2MASX J00505000–2325097) and has a redshift of

![]() $z_{\mathrm{spec}}$

= 0.111367 (Jones et al. Reference Jones2009). We base our FR II classification on the fading hot spots in the outer, bent radio lobes, but note some similarity to 3C 288, which is classified as a transitional type by Bridle et al. (Reference Bridle, Fomalont, Byrd and Valtonen1989).

$z_{\mathrm{spec}}$

= 0.111367 (Jones et al. Reference Jones2009). We base our FR II classification on the fading hot spots in the outer, bent radio lobes, but note some similarity to 3C 288, which is classified as a transitional type by Bridle et al. (Reference Bridle, Fomalont, Byrd and Valtonen1989).

The whole structure, which spans around 13.5 arcmin, is rather asymmetric. Its projected linear size is

![]() $\sim$

1.6 Mpc. When measured along the curved trail of radio emission the lobes are

$\sim$

1.6 Mpc. When measured along the curved trail of radio emission the lobes are

![]() $\sim$

2.4 Mpc from end to end. The western radio lobe appears to be much closer (

$\sim$

2.4 Mpc from end to end. The western radio lobe appears to be much closer (

![]() $\sim$

5 arcmin) to the core and brighter than the more extended eastern lobe (

$\sim$

5 arcmin) to the core and brighter than the more extended eastern lobe (

![]() $\sim$

9 arcmin). While the inner jets are linear, each extending

$\sim$

9 arcmin). While the inner jets are linear, each extending

![]() $\sim$

2.5 arcmin towards the SE and NW, and initially symmetric, the SE jet shows enhanced radio emission when it turns North before looping back to the South connecting with the SE lobe. The brightening at the end of the jet and its abrupt turn coincide with the projected location of two background galaxies (near WISEA J005059.40–232608.4) at

$\sim$

2.5 arcmin towards the SE and NW, and initially symmetric, the SE jet shows enhanced radio emission when it turns North before looping back to the South connecting with the SE lobe. The brightening at the end of the jet and its abrupt turn coincide with the projected location of two background galaxies (near WISEA J005059.40–232608.4) at

![]() $z_{\mathrm{phot}}$

= 0.21 and 0.37, respectively (both from Zhou et al. Reference Zhou2021). Because of the difference in redshift to the GRG host, we do not consider these galaxies to be physically associated with the jet.

$z_{\mathrm{phot}}$

= 0.21 and 0.37, respectively (both from Zhou et al. Reference Zhou2021). Because of the difference in redshift to the GRG host, we do not consider these galaxies to be physically associated with the jet.

Figure 11. Zoomed ASKAP 944 MHz radio continuum map of the radio core and eastern jet of ASKAP J0050–2325 (see Figure 10). The contour levels are 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 1.2, 2.5 and 5.0 mJy beam

![]() $^{-1}$

. The ASKAP resolution of 13 arcsec is shown in the bottom left corner. – Left inset: two background galaxies associated with WISEA J005059.40–232608.4 near the enhancement at the end of the eastern radio jet. – Right inset: elliptical GRG host galaxy DES J005050.02–232509.3 (

$^{-1}$

. The ASKAP resolution of 13 arcsec is shown in the bottom left corner. – Left inset: two background galaxies associated with WISEA J005059.40–232608.4 near the enhancement at the end of the eastern radio jet. – Right inset: elliptical GRG host galaxy DES J005050.02–232509.3 (

![]() $z_{\mathrm{spec}}$

= 0.111367); the radio core centre is marked with a green cross. The galaxy to the SW, DES J005049.87–232512.4 (

$z_{\mathrm{spec}}$

= 0.111367); the radio core centre is marked with a green cross. The galaxy to the SW, DES J005049.87–232512.4 (

![]() $z_{\mathrm{phot}}$

= 0.117), is an interacting companion.

$z_{\mathrm{phot}}$

= 0.117), is an interacting companion.

We measure the ASKAP position of the GRG’s radio core as

![]() $\alpha,\delta$

(J2000) =

$\alpha,\delta$

(J2000) =

![]() $00^\textrm{h}\,50^\textrm{ m}\,50.03^\textrm{s}$

, –23

$00^\textrm{h}\,50^\textrm{ m}\,50.03^\textrm{s}$

, –23

![]() $^\circ$

25′ 09.32″ (peak flux

$^\circ$

25′ 09.32″ (peak flux

![]() $\sim$

8.8 mJy beam

$\sim$

8.8 mJy beam

![]() $^{-1}$

). The source was previously catalogued as NVSS J005049–232509 and is also detected in VLASS as a point source (

$^{-1}$

). The source was previously catalogued as NVSS J005049–232509 and is also detected in VLASS as a point source (

![]() $\sim$

7.5 mJy). The position of the associated WISE source, WISEA J005049.89–232511.1, is offset, likely due to confusion with a neighbouring galaxy (shown in Figure 11) of similar redshift.

$\sim$

7.5 mJy). The position of the associated WISE source, WISEA J005049.89–232511.1, is offset, likely due to confusion with a neighbouring galaxy (shown in Figure 11) of similar redshift.

ASKAP J0055–2231 is an FR I-type radio galaxy with LAS = 9.2 arcmin (see Figure 12). The host galaxy is WISEA J005548.98–223116.9 (

![]() $z_{\mathrm{spec}}$

= 0.11437; 6dF, Jones et al. Reference Jones2009). We derive LLS = 1.14 Mpc. This GRG has bright inner jets, fading into wider radio lobes with the western side more extended and much fainter than the eastern side. We measure flux densities of approximately 145 mJy (E lobe), 137 mJy (W lobe), and 282 mJy (total). The central radio peak (30 mJy beam

$z_{\mathrm{spec}}$

= 0.11437; 6dF, Jones et al. Reference Jones2009). We derive LLS = 1.14 Mpc. This GRG has bright inner jets, fading into wider radio lobes with the western side more extended and much fainter than the eastern side. We measure flux densities of approximately 145 mJy (E lobe), 137 mJy (W lobe), and 282 mJy (total). The central radio peak (30 mJy beam

![]() $^{-1}$

) at 944 MHz is

$^{-1}$

) at 944 MHz is

![]() $\sim$

10 east of the host galaxy. The GRG is associated with NVSS J005549–223115 (

$\sim$

10 east of the host galaxy. The GRG is associated with NVSS J005549–223115 (

![]() $176.6 \pm 6.0$

mJy at 1.4 GHz) and detected in VLASS as an E–W extended source (but affected by artifacts). The TGSS-NVSS spectral index map (de Gasperin et al. Reference de Gasperin, Intema and Frail2018) shows much steeper values on the eastern side compared to the western side. This GRG was also catalogued by Dabhade et al. (Reference Dabhade2020b) with LAS = 6.38 arcmin using NVSS where the faint western lobe is not detected.

$176.6 \pm 6.0$

mJy at 1.4 GHz) and detected in VLASS as an E–W extended source (but affected by artifacts). The TGSS-NVSS spectral index map (de Gasperin et al. Reference de Gasperin, Intema and Frail2018) shows much steeper values on the eastern side compared to the western side. This GRG was also catalogued by Dabhade et al. (Reference Dabhade2020b) with LAS = 6.38 arcmin using NVSS where the faint western lobe is not detected.

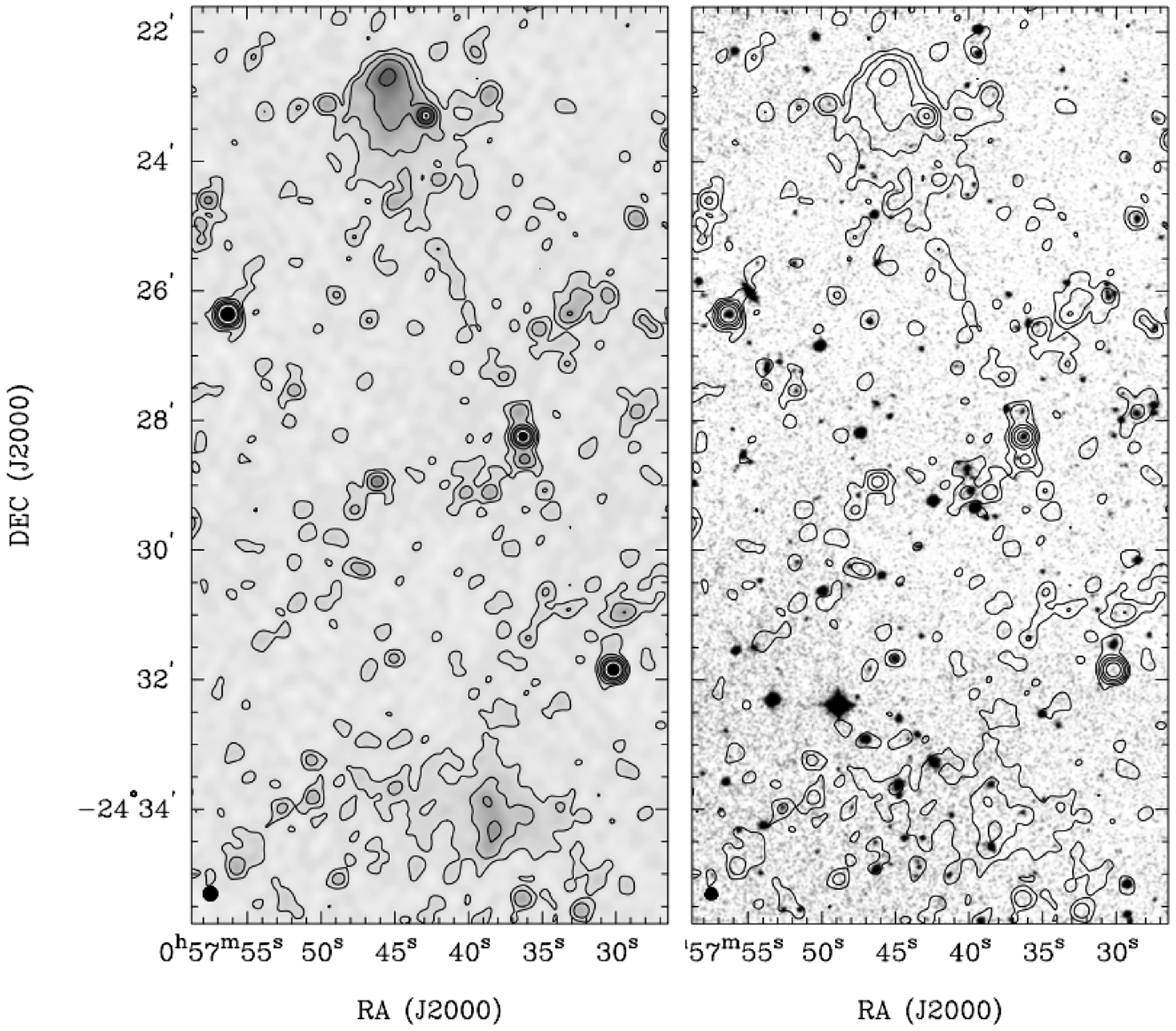

ASKAP J0057–2428 is an FR II-type GRG with inner radio knots (hotspots, separated by 43 arcsec) and slightly bent outer radio lobes extending 12.1 arcmin (see Figure 13). Its host galaxy is WISEA J005736.30–242814.9 (2MASS J00573630–2428152, DES J005736.29–242814.8) at

![]() $z_{\mathrm{phot}}$

=

$z_{\mathrm{phot}}$

=

![]() $0.238 \pm 0.023$

(Zhou et al. Reference Zhou2021), giving LLS = 2.74 Mpc. We measure the following flux densities: 2.4 mJy (core + inner jets), 11.0 mJy (N lobe), 7.3 mJy (S lobe), and 20.6 mJy (total). The radio core is at

$0.238 \pm 0.023$

(Zhou et al. Reference Zhou2021), giving LLS = 2.74 Mpc. We measure the following flux densities: 2.4 mJy (core + inner jets), 11.0 mJy (N lobe), 7.3 mJy (S lobe), and 20.6 mJy (total). The radio core is at

![]() $\alpha,\delta$

(J2000) =

$\alpha,\delta$

(J2000) =

![]() $00^\textrm{h}\,57^\textrm{m}\,36.33^\textrm{s}$

, –24

$00^\textrm{h}\,57^\textrm{m}\,36.33^\textrm{s}$

, –24

![]() $^\circ$

28′ 15″ with a peak flux of 1.5 mJy beam

$^\circ$

28′ 15″ with a peak flux of 1.5 mJy beam

![]() $^{-1}$

and also detected in VLASS.

$^{-1}$

and also detected in VLASS.

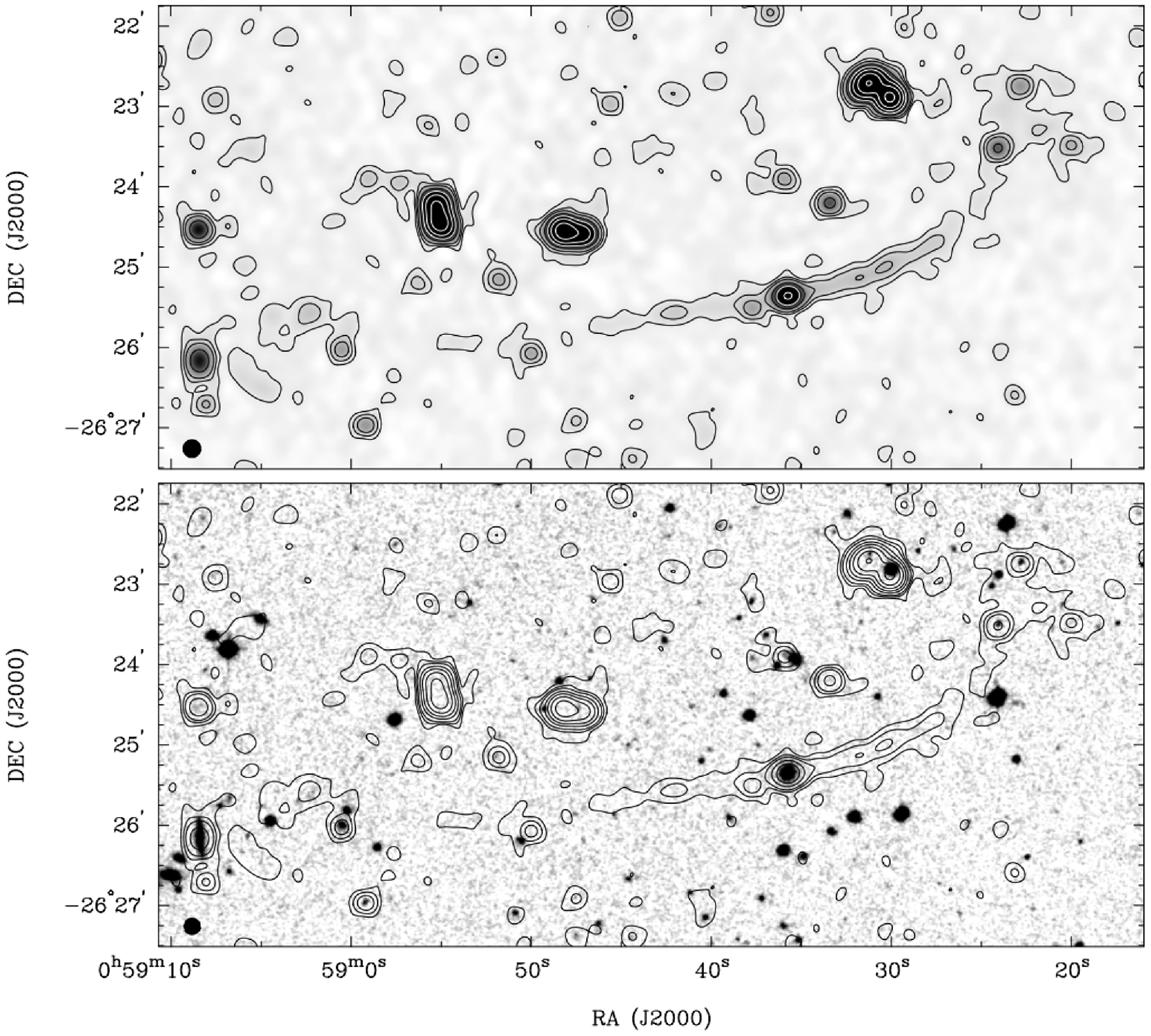

ASKAP J0058–2625 is a bent FR I/II-type GRG spanning 12 arcmin (see Figure 14). Its host galaxy is WISEA J005835.74–262521.3 (2MASX J00583576–2625214; DES J005835.73–262521.2) at

![]() $z_{\mathrm{spec}}$

= 0.11341 (Colless et al. Reference Colless2001). We derive LLS = 1.48 Mpc. While the inner jets are clearly detected, the outer radio lobes, particularly on the eastern side, are very faint. We measure approximate flux densities of 2.8 mJy (radio core), 2.4 mJy (E), 3.8 mJy (W), and 9.0 mJy (total). The radio core is at

$z_{\mathrm{spec}}$

= 0.11341 (Colless et al. Reference Colless2001). We derive LLS = 1.48 Mpc. While the inner jets are clearly detected, the outer radio lobes, particularly on the eastern side, are very faint. We measure approximate flux densities of 2.8 mJy (radio core), 2.4 mJy (E), 3.8 mJy (W), and 9.0 mJy (total). The radio core is at

![]() $\alpha,\delta$

(J2000) =

$\alpha,\delta$

(J2000) =

![]() $00^\textrm{h}\,58^\textrm{ m}\,35.74^\textrm{s}$

, –26

$00^\textrm{h}\,58^\textrm{ m}\,35.74^\textrm{s}$

, –26

![]() $^\circ$

25′ 21.65″ and has a peak flux of 2.2 mJy beam

$^\circ$

25′ 21.65″ and has a peak flux of 2.2 mJy beam

![]() $^{-1}$

.

$^{-1}$

.

ASKAP J0059–2352 is an FR II-type GRG candidate with radio lobes extending 8.0 arcmin (see Figure 15). The association remains uncertain due to the lack of connecting jets and the presence of other bright sources near the putative lobes. Approximately midway between the latter is the potential host galaxy, WISEA J005954.72–235254.7 (DES J005954.75–235253.9), with

![]() $z_{\mathrm{phot}}$

=

$z_{\mathrm{phot}}$

=

![]() $0.735 \pm 0.041$

(Zhou et al. Reference Zhou2021), which is our highest redshift in Table 1. The radio core is very faint compared to the bright, compact radio lobes (see Figure 23). Based on the redshift above, we estimate LLS = 3.49 Mpc, which makes it the second largest GRG in our sample. Both lobes contain hotspots with radio emission extending towards the core and neither has optical/IR counterparts. They are also detected in NVSS and TGSS with spectral index values of around

$0.735 \pm 0.041$

(Zhou et al. Reference Zhou2021), which is our highest redshift in Table 1. The radio core is very faint compared to the bright, compact radio lobes (see Figure 23). Based on the redshift above, we estimate LLS = 3.49 Mpc, which makes it the second largest GRG in our sample. Both lobes contain hotspots with radio emission extending towards the core and neither has optical/IR counterparts. They are also detected in NVSS and TGSS with spectral index values of around

![]() $-0.6$

and

$-0.6$

and

![]() $-0.3$

for the eastern and western lobes, respectively (de Gasperin et al. Reference de Gasperin, Intema and Frail2018).

$-0.3$

for the eastern and western lobes, respectively (de Gasperin et al. Reference de Gasperin, Intema and Frail2018).

Alternately, Figure 15 may show at least two double-lobed radio galaxies, one either associated with a radio-loud quasar WISEA J010003.49–235328.5 at

![]() $z_{\mathrm{phot}}$

= 0.14 or the galaxy WISEA J010014.11–235513.3 at

$z_{\mathrm{phot}}$

= 0.14 or the galaxy WISEA J010014.11–235513.3 at

![]() $z_{\mathrm{phot}}$

= 0.21 and the other with the early-type galaxy WISEA J005939.33–235123.8 at

$z_{\mathrm{phot}}$

= 0.21 and the other with the early-type galaxy WISEA J005939.33–235123.8 at

![]() $z_{\mathrm{phot}}$

= 0.26. In that case, the RGs have LAS = 3.2 arcmin (LLS = 474 kpc) and 1.0 arcmin (LLS = 240 kpc), respectively.

$z_{\mathrm{phot}}$

= 0.26. In that case, the RGs have LAS = 3.2 arcmin (LLS = 474 kpc) and 1.0 arcmin (LLS = 240 kpc), respectively.

ASKAP J0100–2125 is an FR I-type GRG with host galaxy WISEA J010039.00–212533.5 (

![]() $z_{\mathrm{phot}}$

= 0.193) and LAS = 6.34 arcmin (see Figure 16). Faint bi-polar jets connect to diffuse radio lobes, both bending by

$z_{\mathrm{phot}}$

= 0.193) and LAS = 6.34 arcmin (see Figure 16). Faint bi-polar jets connect to diffuse radio lobes, both bending by

![]() $\gt$

90

$\gt$

90

![]() $^\circ$

northwards. We derive LLS = 1.21 Mpc. The bright radio core is also detected in VLASS. The ASKAP coverage for this position is currently limited to one field (SB13570;

$^\circ$

northwards. We derive LLS = 1.21 Mpc. The bright radio core is also detected in VLASS. The ASKAP coverage for this position is currently limited to one field (SB13570;

![]() $\sim$

10 h, see Figure 1).

$\sim$

10 h, see Figure 1).

Figure 12. ASKAP J0055–2231 (FR I-type GRG). – Top: ASKAP 944 MHz radio continuum map; the contour levels are 0.04, 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, 1.2, 2.1, 5.0, 10.0 and 20.0 mJy beam

![]() $^{-1}$

. – Bottom: ASKAP radio contours overlaid onto a DSS2 R-band image. The host galaxy is WISEA J005548.98–223116.9 (

$^{-1}$

. – Bottom: ASKAP radio contours overlaid onto a DSS2 R-band image. The host galaxy is WISEA J005548.98–223116.9 (

![]() $z_{\mathrm{spec}}$

= 0.11437). The ASKAP resolution of 13 arcsec is shown in the bottom left corner.

$z_{\mathrm{spec}}$

= 0.11437). The ASKAP resolution of 13 arcsec is shown in the bottom left corner.

ASKAP J0102–2154 is a complex radio structure extending N–S over 6.4 arcmin (see Figure 17). The radio emission comes from the foreground Abell 133 galaxy cluster (

![]() $z = 0.0556$

, Struble & Rood Reference Struble and Rood1999), a radio relic identified by Slee et al. (Reference Slee, Roy, Murgia, Andernach and Ehle2001) just north of and associated with the cluster, and a background GRG with host 2MASX J01024529–2154137 (

$z = 0.0556$

, Struble & Rood Reference Struble and Rood1999), a radio relic identified by Slee et al. (Reference Slee, Roy, Murgia, Andernach and Ehle2001) just north of and associated with the cluster, and a background GRG with host 2MASX J01024529–2154137 (

![]() $z_{\mathrm{spec}}$

= 0.2930, Owen, Ledlow, & Keel Reference Owen, Ledlow and Keel1995) and LLS = 1.68 Mpc. For a detailed multi-wavelength study of the area see Randall et al. (Reference Randall2010), who expand on the radio and X-ray analysis of the northern component by Slee et al. (Reference Slee, Roy, Murgia, Andernach and Ehle2001). The source is also part of the EMU pilot study of galaxy clusters by Duchesne et al. (Reference Duchesne2024). The ASKAP coverage for this position is currently limited to one field (SB13570;

$z_{\mathrm{spec}}$

= 0.2930, Owen, Ledlow, & Keel Reference Owen, Ledlow and Keel1995) and LLS = 1.68 Mpc. For a detailed multi-wavelength study of the area see Randall et al. (Reference Randall2010), who expand on the radio and X-ray analysis of the northern component by Slee et al. (Reference Slee, Roy, Murgia, Andernach and Ehle2001). The source is also part of the EMU pilot study of galaxy clusters by Duchesne et al. (Reference Duchesne2024). The ASKAP coverage for this position is currently limited to one field (SB13570;

![]() $\sim$

10 h, see Figure 1).

$\sim$

10 h, see Figure 1).

Figure 13. ASKAP J0057–2428 (FR II-type GRG). – Left: ASKAP 944 MHz radio continuum map; the contour levels are 0.03, 0.1, 0.25, 0.5 and 1 mJy beam

![]() $^{-1}$

. – Right: ASKAP contours overlaid onto a DSS2 R-band image. The GRG host galaxy is WISEA J005736.30–242814.9 (

$^{-1}$

. – Right: ASKAP contours overlaid onto a DSS2 R-band image. The GRG host galaxy is WISEA J005736.30–242814.9 (

![]() $z_{\mathrm{phot}}$

= 0.238). The ASKAP resolution of 13 arcsec is shown in the bottom left corner.

$z_{\mathrm{phot}}$

= 0.238). The ASKAP resolution of 13 arcsec is shown in the bottom left corner.

Figure 14. ASKAP J0058–2625 (FR I/II-type GRG). – Top: ASKAP 944 MHz radio continuum map; the contour levels are 0.03, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 8 mJy beam

![]() $^{-1}$

. – Bottom: ASKAP radio contours overlaid onto a DSS2 R-band image. The GRG host galaxy is WISEA J005835.74–262521.3 (

$^{-1}$

. – Bottom: ASKAP radio contours overlaid onto a DSS2 R-band image. The GRG host galaxy is WISEA J005835.74–262521.3 (

![]() $z_{\mathrm{spec}}$

= 0.1134). The ASKAP resolution of 13 arcsec is shown in the bottom left corner.

$z_{\mathrm{spec}}$

= 0.1134). The ASKAP resolution of 13 arcsec is shown in the bottom left corner.

The GRG’s northern lobe, which is partially located behind the merging cD galaxy (ESO 541-G013,

![]() $z = 0.057$

), appears to be connected to the host galaxy by a narrow jet-like structure. Another radio jet emerges from the host to the south, twisting and connecting to the southern radio lobe which has a peculiar, not previously seen double ring/shell morphology with a cluster galaxy (WISEA J010245.32–215729.4, (

$z = 0.057$

), appears to be connected to the host galaxy by a narrow jet-like structure. Another radio jet emerges from the host to the south, twisting and connecting to the southern radio lobe which has a peculiar, not previously seen double ring/shell morphology with a cluster galaxy (WISEA J010245.32–215729.4, (

![]() $z_{\mathrm{spec}}$

= 0.056492, Smith et al. Reference Smith2004) embedded. Overall, the GRG looks like a giant ‘Twister’, somewhat resembling Hercules A (3C 348), 3C 353 and IC 4296. The ring-like structures inside the southern radio lobe are possibly annular shocks (vortex rings) expanding within the jet’s backflow (Saxton, Bicknell, & Sutherland Reference Saxton, Bicknell and Sutherland2002; Kataoka et al. Reference Kataoka2008; Condon et al. Reference Condon2021).

$z_{\mathrm{spec}}$

= 0.056492, Smith et al. Reference Smith2004) embedded. Overall, the GRG looks like a giant ‘Twister’, somewhat resembling Hercules A (3C 348), 3C 353 and IC 4296. The ring-like structures inside the southern radio lobe are possibly annular shocks (vortex rings) expanding within the jet’s backflow (Saxton, Bicknell, & Sutherland Reference Saxton, Bicknell and Sutherland2002; Kataoka et al. Reference Kataoka2008; Condon et al. Reference Condon2021).

At the position of the host, 2MASX J01024529–2154137 (WISEA J010245.22–215414.3), the DES optical images reveal a close galaxy pair, separated by only 1.3 arcsec (5.7 kpc). Furthermore, extended, banana-shaped (lensed?) VLASS 3 GHz emission in the core area (

![]() $PA \sim 40$

deg) lies just offset from the galaxy pair and is misaligned with the N–S structure of the large radio structure.

$PA \sim 40$

deg) lies just offset from the galaxy pair and is misaligned with the N–S structure of the large radio structure.

ASKAP J0107–2347 appears to be a re-started GRG with LAS = 13.8 arcmin (see Figure 18). Its host galaxy is WISEA J010721.14–234734.1 (2MASX J01072137–2347346, DES J010721.39–234734.0) with

![]() $z_{\mathrm{phot}}$

=

$z_{\mathrm{phot}}$

=

![]() $0.312 \pm 0.024$

(Zhou et al. Reference Zhou2021). We derive LLS = 3.79 Mpc, which makes it the largest GRG in our sample. This GRG can also be classified as a DDRG, where the outer lobes are relic lobes. The ASKAP coverage for this position is currently limited to one field (SB13570;

$0.312 \pm 0.024$

(Zhou et al. Reference Zhou2021). We derive LLS = 3.79 Mpc, which makes it the largest GRG in our sample. This GRG can also be classified as a DDRG, where the outer lobes are relic lobes. The ASKAP coverage for this position is currently limited to one field (SB13570;

![]() $\sim$

10 h, see Figure 1). We measure the following flux densities: 5.0 mJy (core), 25.0 mJy (inner N lobe), 7.0 mJy (inner S lobe), 21.3 mJy (outer N lobe), 30.7 mJy (outer S lobe), and 89 mJy (total). The radio core is at

$\sim$

10 h, see Figure 1). We measure the following flux densities: 5.0 mJy (core), 25.0 mJy (inner N lobe), 7.0 mJy (inner S lobe), 21.3 mJy (outer N lobe), 30.7 mJy (outer S lobe), and 89 mJy (total). The radio core is at

![]() $\alpha,\delta$

(J2000) = 01:07:21.375, –23:47:34.33 with a peak flux of 4.3 mJy beam

$\alpha,\delta$

(J2000) = 01:07:21.375, –23:47:34.33 with a peak flux of 4.3 mJy beam

![]() $^{-1}$

. The full extent of the GRG is also faintly detected in NVSS. We measure an integrated NVSS 1.4 GHz flux density of 28.0 mJy for the inner lobes (including the core) and 47.5 mJy over the whole GRG area detected by ASKAP, suggesting a steep spectral index for the outer radio lobes unless significant extended emission was resolved out in NVSS. Comparing the integrated ASKAP and NVSS fluxes, we obtain approximate spectral indices of around –1 (inner lobes), –2 (outer lobes), and –1.6 (total). The VLASS 3 GHz image shows a core of

$^{-1}$