Introduction

The physiological state of livestock and poultry is affected by a variety of factors, such as high temperature, low sanitary conditions, disease stimulation, etc. These factors are prone to trigger the oxidative stress response of the organism, which has an impact on the health status and production performance of livestock and poultry (Mishra and Jha Reference Mishra and Jha2019). Gut health and function play a key role in poultry production. The gut microbiota consists mainly of bacteria, fungi and protozoa (Gabriel et al. Reference Gabriel, Lessire and Mallet2006). When oxidative stress occurs in poultry, it triggers an inflammatory response that disrupts the intestinal barrier and micro-ecological balance (Elokil et al. Reference Elokil, Li and Chen2024; Kikusato and Toyomizu Reference Kikusato and Toyomizu2023).

Akkermansia muciniphila (AKK) is an oval-shaped gram-negative bacterium that is recognized as a “next-generation probiotic” (Chelakkot et al. Reference Chelakkot, Choi and Kim2018; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Wu and Qu2019). AKK primarily uses human intestinal mucus as its source of carbon and nitrogen (Aggarwal et al. Reference Aggarwal, Sunder and Verma2022). Some studies have shown that AKK regulates the intestinal barrier by modulating the tight junction (TJ) proteins Claudin-3 and Occludin (Chelakkot et al. Reference Chelakkot, Choi and Kim2018; Plovier et al. Reference Plovier, Everard and Druart2017). Ottman et al. (Reference Ottman, Reunanen and Meijerink2017) found that AKK treatment increased the transepithelial cellular resistance of human clonal colon cancer cells (Caco-2 cells) in in vitro studies, as evidenced by enhanced intestinal epithelial barrier function (Ottman et al. Reference Ottman, Reunanen and Meijerink2017). Studies have shown that AKK is associated with human health, and its metabolite propionic acid, which demonstrates immunomodulatory effects in the body (Lukovac et al. Reference Lukovac, Belzer and Pellis2014). A study by Plovier et al. (Reference Plovier, Everard and Druart2017) found that AKK, even after pasteurization and inactivation, retained the ability to reduce insulin resistance and improve dyslipidemia. Furthermore, research demonstrates that AKK alleviates lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced intestinal dysfunction through restoration of gut microbiota homeostasis and modulation of immune responses (Hu et al. Reference Hu, Zhou and Lin2025).

Current research on AKK has primarily focused on humans and murine models, with limited exploration of its effects in livestock and poultry. In this study, we utilized LPS to establish a stress model in broilers, investigating how different preparations of AKK (AKK broth culture, viable AKK suspension and inactivated AKK suspension) modulate gut microbiome composition and jejunum health post-stress. This work aims to provide a scientific foundation for leveraging AKK in poultry production and stress mitigation strategies.

Materials and methods

Preparation of AKK

AKK (ATCC BAA-835) was anaerobically cultured in mucin-containing broth medium (1% porcine gastric mucin, 0.5% tryptone, 0.2% yeast extract, pH 6.8) at 37°C for 72 hours and harvested at late-log phase (OD600 ≈ 0.8–1.0). For the preparation of a viable AKK suspension, the AKK broth culture was centrifuged at 8,000× g for 10 min at 4°C to pellet bacterial cells. The supernatant was discarded, and the bacterial pellet was washed twice with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4). Finally, the cells were resuspended in PBS to a final concentration of 1 × 108 colony-forming units (CFU)/mL. For the heat-inactivated AKK suspension, the AKK pellet was resuspended in PBS and subjected to heat inactivation at 80°C for 30 min. The viability and inactivation of AKK cells were verified by culturing the treated suspension on agar plates.

Animal experimental design

One hundred one-day-old healthy male Lingnan yellow-feathered broilers were randomly divided into five groups. Each group had four replicates with five chickens per replicate. Control group (gavage of 1 mL PBS and intraperitoneal injection of an equal amount of saline); LPS group (gavage of 1 mL PBS and intraperitoneal injection of 0.5 mg/kg BW LPS); AKK group (gavage of 1 mL 108 CFU/mL AKK with culture medium and intraperitoneal injection of 0.5 mg/kg BW LPS); Active group (gavage of 1 mL 108 CFU/mL viable AKK suspension and intraperitoneal injection of 0.5 mg/kg BW LPS); Inactive group (gavage of 1 mL 108 CFU/mL heat-inactivated AKK suspension and intraperitoneal injection of 0.5 mg/kg BW LPS). Oral gavage with different AKK preparations was administered on days 7, 9, 11, 13, 15 and 17, while intraperitoneal injections were performed on days 17, 19 and 21. LPS from Escherichia coli O55:B5 (Product No. L2880, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was used to induce the stress model. Throughout the study, broiler chicks were housed under controlled environmental conditions with ad libitum access to water and a corn-soybean meal-based basal diet (Table 1). The coop temperature was maintained at 32°C–33°C during the first week, and gradually decreased to 24°C by the end of the third week. Throughout the experimental period, all birds remained clinically healthy, and no mortality was recorded. Feed intake and body weight were monitored to evaluate growth performance, including average daily gain (ADG), average daily feed intake (ADFI) and feed conversion ratio. On day 22, following a 12-hour fasting period, one bird per replicate (n = 4) was randomly selected and humanely euthanized by cervical dislocation. Cecal digesta and jejunal mucosa samples were collected for downstream analysis.

Table 1. The ingredients and nutrient composition of the basal diet

Note: (1) Premix provided per kilogram of the diet: vitamin A 12,000 IU; vitamin D3 3000 IU; vitamin E 10 IU; vitamin K3 2 mg; vitamin B1 1 mg; vitamin B2 3 mg; vitamin B6 2 mg; vitamin B12 0.01 mg; niacin 20 mg; pantothenic acid 4 mg; folic acid 0.54 mg; biotin 0.05 mg; Fe 100 mg; Cu 20 mg; Mn 100 mg; Zn 80 mg; I 3 mg; Se 0.5 mg. (2) Antioxidant: The antioxidants used in the premix are Butylated Hydroxytoluene (BHT) and Tert-butylhydroquinone (TBHQ).

16S rDNA analysis of the gut microbiota

Genomic DNA was extracted from the contents of the cecum using the cetyltrimethylammonium bromide method (Trojánek et al. Reference Trojánek, Kovarík and Spanová2018). Then the purity and concentration of DNA were detected by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. The appropriate amount of sample DNA was put into a centrifuge tube and diluted to 1 ng/μL with sterile water. After DNA extraction, the V3–V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified with primers 341 F (5’-CCTAYGGGRBGCASCAG-3’) and 806 R (5’-GGACTACNNGGGGTATCTAAT-3’). The PCR products were mixed in equal amounts according to the concentration, and the PCR products were detected by agarose gel electrophoresis with 2% agarose after sufficient mixing. The products were recovered using the Universal DNA Purification and Recovery Kit (TianGen) for the target bands. The library was constructed, and the constructed library was quantified by Qubit and Q-PCR. After the library was qualified, NovaSeq6000 was used to perform PE250 on-line sequencing to obtain the raw data. Then the raw data were spliced and filtered to obtain clean data. Based on the valid data, DADA2 was used for noise reduction to obtain the final ASVs (Li et al. Reference Li, Shao and Zhou2020).

The obtained ASVs were subjected to species annotation, Alpha diversity analysis and Beta diversity analysis using QIIME2 software. A Venn diagram of ASVs was created using R (Version 3.5.3; Venn Diagram package). Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) analyses were calculated and plotted by the ade4 package and ggplot2 package in R software (version 4.0.3). Linear discriminant analysis (LEfSe) effect size was performed using LEfSe software with a default linear discriminant analysis (LDA) score threshold of 2.0 (Segata et al. Reference Segata, Izard and Waldron2011). Finally, the microbial community was analyzed for functional prediction using PICRUSt 2 software (Douglas et al. Reference Douglas, Maffei and Zaneveld2020).

RNA extraction and transcriptome sequencing

Total RNA was extracted from the jejunal mucosa with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and then accurately examined for RNA integrity using an Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer. The mRNAs with polyA tails were enriched by Oligo magnetic beads, and then the obtained mRNAs were randomly interrupted with divalent cations in NEB Fragmentation Buffer, and the libraries were constructed according to the NEB common library construction method (Parkhomchuk et al. Reference Parkhomchuk, Borodina and Amstislavskiy2009). The different libraries were subjected to Illumina sequencing to obtain raw data. The raw data were then filtered to obtain clean data, and the paired-end clean reads were compared to the reference genome using HISAT2 v2.0.5. The FPKM for each gene was then calculated based on the length of the gene, and the number of reads mapped to that gene was calculated using featureCounts (1.5.0-p3). Differential expression analysis between the two comparison combinations was performed using DESeq2 software (1.20.0), and the resulting P-values were adjusted to control for false discovery rates using the method of Benjamini and Hochberg. Genes with |log2(FoldChange)| ≥ 1 and adjusted P-values ≤0.05 were assigned as differentially expressed. KEGG analysis and GO enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were achieved by clusterProfiler (3.8.1) software.

Statistical analysis

The experimental data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (SPSS 27.0). The following statistical model was used: Yijk = μ + Ti + εij, where Yijk = measured response, μ = overall mean, Ti = fixed effect of treatment (i = 1 to 5) and εij = residuals. Duncan’s method was employed for multiple comparisons upon significance. Significance was declared at P ≤ 0.05.

Results

Determination of growth performance

LPS significantly decreased the final weight and ADG of broilers (P < 0.05; Table 2). There was no significant difference in ADFI among the five groups. Notably, the addition of AKK broth culture completely counteracted the LPS-induced growth depression. There were no significant differences in final body weight and ADG between the AKK group and the Control group.

Table 2. Effect of Akkermansia muciniphila on the growth performance of lipopolysaccharide-challenged yellow-feathered broilers

Note: Control: gavage with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and intraperitoneal injection of saline; LPS: gavage with PBS and administered intraperitoneally with lipopolysaccharide (LPS); AKK: gavage with Akkermansia muciniphila in culture medium and administered intraperitoneally with LPS; Active: gavage with live Akkermansia muciniphila resuspended in PBS and administered intraperitoneally with LPS; Inactive: gavage with inactivated Akkermansia muciniphila resuspended in PBS and administered intraperitoneally with LPS; SEM: standard error of mean;

a,b,c Means in the same row with different superscript letters differ significantly (P < 0.05).

Similarity analysis and alpha diversity analysis

After data filtering, quality control and chimeric sequence removal, valid data were obtained (Table 3). The number of valid data bases of all samples ranged from 23, 634, 939 to 41, 431, 813 nt, and the average length ranged from 409.76 to 417.18 nt. While the GC, Q20 and Q30 were above 50%, 98% and 90%, respectively.

Table 3. Statistical information of obtained effective tags during data processing for 16S rDNA sequencing

Note: Base (nt): is the number of effective tags; Avglen (nt): refers to the average length of effective tags; Q20 (%) and Q30 (%): refer to the percentage of total effective tags for bases with mass values greater than or equal to 20 and 30, respectively; GC (%): indicates the content of GC bases in effective tags.

A total of 1,403 amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) were identified from 20 samples (Fig. 1). Among these, 278 ASVs were shared by all groups, while unique ASV counts were observed in the Control (151), LPS (199), AKK (165), Active (190) and Inactive (149) groups, respectively. There was no significant difference in chao1, dominance, goods_coverage, observed_features, pielou_e, shannon and simpson indices among the five groups (Table 4).

Figure 1. Venn diagram of shared ASVs in five groups.

Table 4. Effect of Akkermansia muciniphila on alpha diversity indices of gut microbiota in lipopolysaccharide-challenged yellow-feathered broiler chickens

Note: Control: gavage with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and intraperitoneal injection of saline; LPS: gavage with PBS and administered intraperitoneally with lipopolysaccharide (LPS); AKK: gavage with Akkermansia muciniphila in culture medium and administered intraperitoneally with LPS; Active: gavage with live Akkermansia muciniphila resuspended in PBS and administered intraperitoneally with LPS; Inactive: gavage with inactivated Akkermansia muciniphila resuspended in PBS and administered intraperitoneally with LPS; SEM: standard error of mean.

Table 5. Effect of Akkermansia muciniphila on the composition of the gut microbiota of lipopolysaccharide-challenged yellow-feathered broilers at phylum level

Note: Control: gavage with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and intraperitoneal injection of saline; LPS: gavage with PBS and administered intraperitoneally with lipopolysaccharide (LPS); AKK: gavage with Akkermansia muciniphila in culture medium and administered intraperitoneally with LPS; Active: gavage with live Akkermansia muciniphila resuspended in PBS and administered intraperitoneally with LPS; Inactive: gavage with inactivated Akkermansia muciniphila resuspended in PBS and administered intraperitoneally with LPS; SEM: standard error of mean;

a,b,c Means in the same row with different superscript letters differ significantly (P < 0.05).

The results of PCoA analysis revealed that the first and second principal components accounted for 28.73% and 13.52% of the total variance, respectively (Fig. 2). No significant separation was observed between samples from different groups. Anosim similarity analysis indicated that the between-group difference for Control-LPS was significantly greater than the within-group difference (R-value > 0, P-value < 0.05). For other group comparisons (excluding AKK-inactive group), while the between-group differences were nominally greater than within-group differences, these results did not reach statistical significance (R-value > 0, P-value > 0.05).

Figure 2. Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) of the gut microbiota in different groups.

Analysis of gut microbial composition

Firmicutes, Bacteroidota and Verrucomicrobiota were the dominant phyla (Table 5) while Firmicutes in the Control group was significantly more abundant than the AKK, Active and Inactive groups (P < 0.05). At the genus level, Bacteroides, Alistipes and Akkermansia were identified as dominant genera. The abundance of Alistipes in the Active group was significantly lower than in the AKK and Inactive groups (P < 0.05). Similarly, Streptococcus was also comparatively lower in the AKK group, Active group and Inactive groups. In contrast, Akkermansia and Bacteroides exhibited higher relative abundances in the AKK-gavaged group, with Akkermansia reaching its peak abundance in the Active group (Table 6).

Table 6. Effect of Akkermansia muciniphila on the composition of the gut microbiota of lipopolysaccharide-challenged yellow-feathered broilers at genus level

Note: Control: gavage with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and intraperitoneal injection of saline; LPS: gavage with PBS and administered intraperitoneally with lipopolysaccharide (LPS); AKK: gavage with Akkermansia muciniphila in culture medium and administered intraperitoneally with LPS; Active: gavage with live Akkermansia muciniphila resuspended in PBS and administered intraperitoneally with LPS; Inactive: gavage with inactivated Akkermansia muciniphila resuspended in PBS and administered intraperitoneally with LPS; SEM: standard error of mean;

a,b,c Means in the same row with different superscript letters differ significantly (P < 0.05).

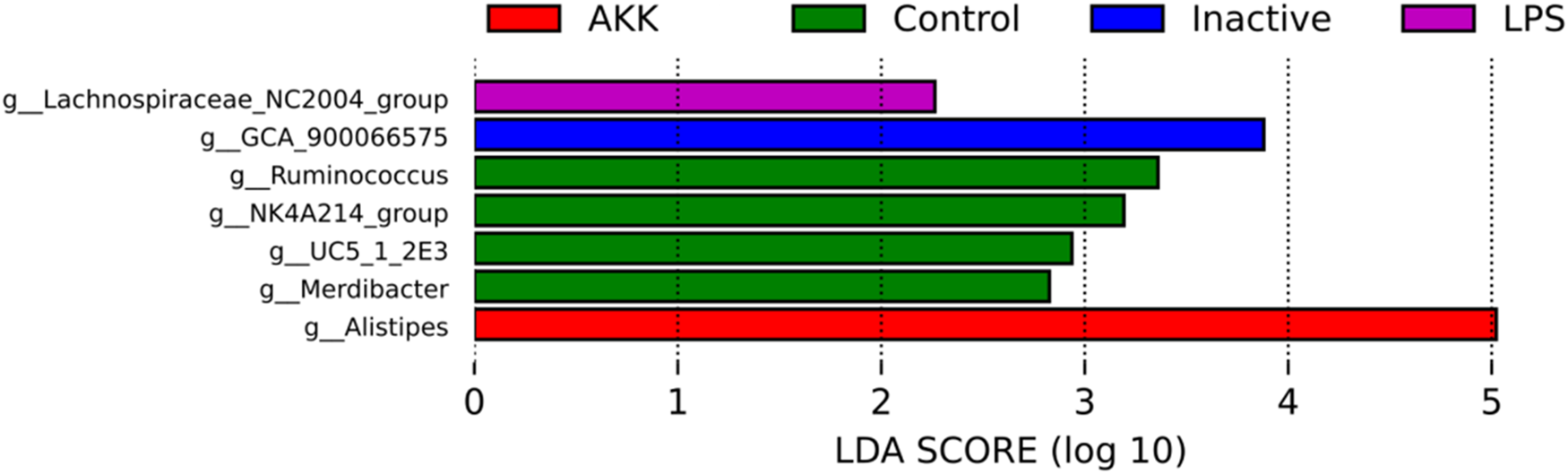

Enriched biomarker taxa were identified at the genus level using LefSe analysis (LDA > 2.0). A total of seven biomarker-bacterial genera were identified in the Control, LPS, AKK and Inactive groups. Among them, Lachnospiraceae_NC2004_group was enriched in LPS group, GCA_900066575 was enriched in Inactive group, Ruminococcus, NK4A214_group, UCS_1_2E3 and Merdibacter were enriched in Control group, Alistipes was enriched in the AKK group (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Histogram of linear discriminant analysis distribution of genus level, using default parameters (LDA >2).

RNA sequence data summary and correlation analysis

A total of 927,366,014 raw reads were obtained from 20 samples. More than 98% of the bases had quality values greater than 20, and more than 97% of the bases had quality values greater than 30 (Table 7). The sequencing data can meet the standard of subsequent sequencing. Correlation analysis was performed between the samples, and the R2 between each group of samples was more than 0.8 (Fig. 4A). Principal component analysis of gene expression values across all samples revealed limited group separation, with the first two principal components (PC1: 27.04%, PC2: 11.35%) collectively explaining 38.39% of the total variance (Fig. 4B). The ordination plot showed no distinct clustering among the five experimental groups.

Figure 4. Quantitative analysis of gene expression in different groups. (A) Heat map of correlation between samples. (B) Plot of results of principal component analysis.

Table 7. Transcriptome sequencing data quality summary

Note: raw_reads: number of reads in raw data; raw_bases: number of bases in raw data (raw base = raw reads × 150 bp); clean_reads: number of reads in raw data after filtering; clean_bases: number of bases in raw data after filtering; Q20: percentage of total bases for bases with Phred value greater than 20; Q30: percentage of total bases for bases with Phred value greater than 30; GC_pct: percentage of four bases in clean reads for G and C.

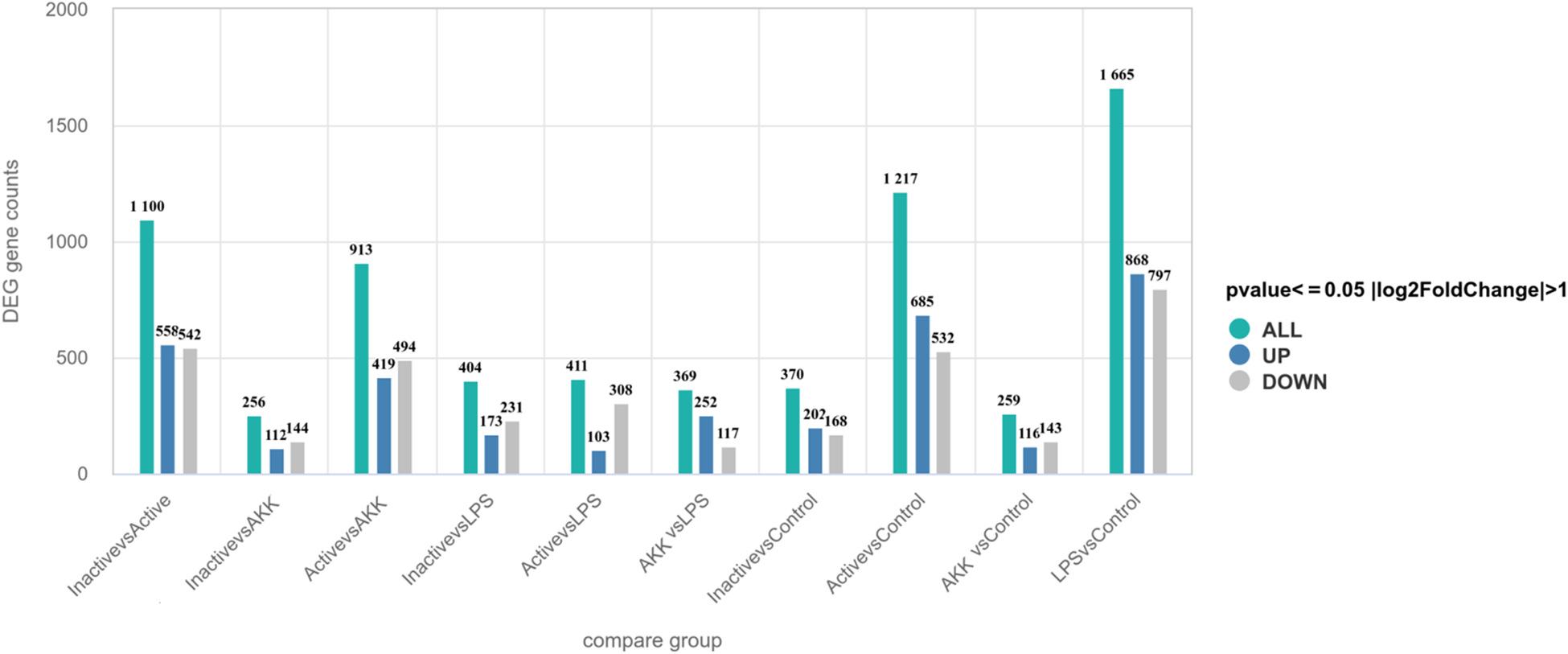

Differential expression analysis

In this study, DEGs were identified using thresholds of |log2(FoldChange)| ≥ 1 and adjusted P-value ≤0.05 (Fig. 5). Differential gene expression analysis revealed distinct patterns across group comparisons. The LPS vs Control group exhibited 259 DEGs (116 upregulated, 143 downregulated), while the AKK vs LPS comparison showed 369 DEGs (252 upregulated, 117 downregulated). The Active vs LPS group had 256 DEGs (112 upregulated, 144 downregulated), whereas the Inactive vs LPS group displayed the highest number of DEGs (1,100; 558 upregulated, 542 downregulated).

Figure 5. Statistical chart of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in the differential comparison combinations.

The expression of the Occludin gene in the Inactive group was significantly lower than that in the other four groups (P < 0.05). While no significant differences were detected in Claudin-1, Claudin-2, or Claudin-3 expression across groups, the Inactive group exhibited consistently lower expression levels of these TJ proteins compared to the other four groups (Table 8).

Table 8. Expression of tight junction protein genes in the jejunum

Note: Control: gavage with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and intraperitoneal injection of saline; LPS: gavage with PBS and administered intraperitoneally with lipopolysaccharide (LPS); AKK: gavage with Akkermansia muciniphila in culture medium and administered intraperitoneally with LPS; Active: gavage with live Akkermansia muciniphila resuspended in PBS and administered intraperitoneally with LPS; Inactive: gavage with inactivated Akkermansia muciniphila resuspended in PBS and administered intraperitoneally with LPS; SEM: standard error of mean;

a,b Means within a row with different superscripts are statistically significantly different (P < 0.05).

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis was performed on the DEGs for each pairwise comparison. The top ten significantly enriched pathways (P < 0.05) from the LPS vs Control, AKK vs LPS, Active vs LPS and Inactive vs LPS comparisons were identified and are summarized in Table 9. The RIG-I-like receptor signaling pathway was downregulated in the LPS vs Control comparison. The NOD-like receptor signaling pathway and RIG-I-like receptor signaling pathway exhibited significant enrichment (P < 0.05) in the AKK vs LPS comparison. Nine pathways were significantly enriched in the Active vs LPS comparison, all of which were downregulated except retinol metabolism. In the Inactive vs LPS comparison, all pathways exhibited downregulation except ribosome, oxidative phosphorylation and cardiac muscle contraction pathways.

Table 9. Analysis of the top ten Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment in the four groups

Note: Control: gavage with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and intraperitoneal injection of saline; LPS: gavage with PBS and administered intraperitoneally with lipopolysaccharide (LPS); AKK: gavage with Akkermansia muciniphila in culture medium and administered intraperitoneally with LPS; Active: gavage with live Akkermansia muciniphila resuspended in PBS and administered intraperitoneally with LPS; Inactive: gavage with inactivated Akkermansia muciniphila resuspended in PBS and administered intraperitoneally with LPS; SEM: standard error of mean.

Gene Ontology function enrichment analysis

Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis categorized results into three ontological domains: biological process (BP), cellular composition and molecular function. The top ten significantly enriched terms from each domain were selected for visualization, with results displayed in Fig. 6. GO enrichment analysis across the four comparisons revealed significant enrichment in terms related to exogenous substance metabolism, energy metabolism, viral defense responses, cellular structure, signal regulation and enzyme activity. In the LPS vs Control comparison, GO enrichment analysis indicated a broad upregulation across most BPs. In contrast, only three terms showed significant downregulation, including actomyosin structure organization, regulation of lipid metabolic process and positive regulation of catabolic process. GO enrichment analysis of the AKK vs LPS comparison indicated a broad functional upregulation, suggesting a strong restorative effect. The significantly upregulated terms were primarily clustered into key biological functions, including viral defense responses (defense response to virus), metabolic processes (phosphate-containing compound metabolic process, phosphorus metabolic process), regulation of cell communication and nucleotide binding activities (guanyl nucleotide binding, guanyl ribonucleotide binding, GTP binding), along with growth factor receptor binding. Compared to the LPS group, the Active group exhibited a transcriptomic signature indicative of reduced cellular stress. This was primarily characterized by a significant downregulation of pathways involved in detoxifying foreign compounds (xenobiotic metabolic process) and a broad suppression of oxidoreductase activities. Compared to the LPS group, the Inactive group exhibited a significant upregulation in the entire protein synthesis machinery, including terms related to ribosomes. Concurrently, pathways for energy production were strongly reactivated (oxidative phosphorylation; respiratory electron transport chain). This was complemented by an enhanced metabolism of nucleotides and energy carriers like ATP. Furthermore, a specific class of oxidoreductase activity, acting on NAD(P)H, was also upregulated, indicating a restoration of cellular metabolic and redox homeostasis.

Discussion

AKK, considered as a next-generation probiotic, is thought to strengthen the gut barrier and reduce inflammatory responses (Shen et al. Reference Shen, Tong and Sud2016). Oral administration of AKK increased jejunal core bacterial abundance and inhibited lipid absorption in the proximal jejunum (Ma et al. Reference Ma, Zhou and Su2025). AKK enhances intestinal barrier integrity through the production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) (Zhang and Wang Reference Zhang and Wang2023). Previous studies have shown that LPS has a negative effect on broiler growth performance (Song et al. Reference Song, Chen and Ai2025; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Gong and Li2023). In the present study, the final weight and ADG of the animals were significantly lower than those of the Control group, confirming the successful induction of stress model through LPS challenge. The protective effect on growth appeared to be unique to the AKK broth culture. While the AKK group’s final weight was comparable to the Control group, the other LPS-challenged groups treated with AKK preparations (Active and Inactive) did not fully recover their growth. This suggests that the full therapeutic benefit requires a synergistic effect between the live AKK bacteria and the metabolites present in its culture medium, rather than being attributable to a single component or the bacteria’s known weight-regulating functions alone (Cani and de Vos Reference Cani and de Vos2017). In our study, the results of alpha diversity showed that the gut microbial composition was similar among the five groups, and there was no significant difference in their richness, diversity and evenness. The abundance of Firmicutes was lower in the groups with AKK administration (AKK, Active and Inactive) than in the Control group. While studies have demonstrated increased Firmicutes abundance in obese mice (Ley et al. Reference Ley, Bäckhed and Turnbaugh2005), research indicates that AKK may counteract obesity development (Everard et al. Reference Everard, Belzer and Geurts2013). Alistipes suppresses inflammation and ameliorates inflammatory bowel disease, with these effects mediated primarily by the production of SCFAs (Lin et al. Reference Lin, Xu and Lan2025). Both genus-level microbial composition analysis and LefSe results revealed significant enrichment of Alistipes in the AKK group, whereas its abundance was markedly reduced in the Active group. The AKK intervention may alleviate LPS-induced stress by promoting Alistipes proliferation and enhancing the synthesis of SCFAs (e.g., butyrate), thereby suppressing intestinal inflammation through SCFA-mediated mechanisms. Furthermore, microbial composition analysis demonstrated a significant enrichment of Bacteroides and a marked reduction in Streptococcus abundance in the AKK-gavaged group compared to Controls. Bacteroides promotes gut microbial homeostasis (Buzun et al. Reference Buzun, Hsu and Sejane2024). Whereas elevated Streptococcus abundance is associated with severe atrophic gastritis (Iino et al. Reference Iino, Shimoyama and Chinda2019). The observed enrichment of Bacteroides and depletion of Streptococcus in the AKK-gavaged group collectively demonstrate AKK’s ability to stabilize gut microbiota.

The intestinal epithelium serves as a dynamic physical and functional barrier, primarily mediated by adherens junctions (e.g., Cadherins) and TJs (e.g., Claudins, Occludin and JAM proteins) (Groschwitz and Hogan Reference Groschwitz and Hogan2009). LPS induces intestinal barrier dysfunction by enhancing TJ permeability through a TLR4-dependent signaling pathway, thereby compromising epithelial integrity (Guo et al. Reference Guo, Nighot and Al-Sadi2015). AKK was reported to modulate the intestinal barrier by enhancing the expression of TJ proteins Claudin-3 and Occludin (Chelakkot et al. Reference Chelakkot, Choi and Kim2018). In our study, there was no significant difference in the expression of Claudin-1, Claudin-2 and Claudin-3 among the five groups, but the Inactive group had the lowest relative content. Also, the Occludin in the Inactive group was significantly lower than in the other four groups. This indicates that the intestinal barrier function of the jejunum in the Inactive group was weaker than in the other four groups.

KEGG pathway analysis revealed differential regulation of PPAR signaling genes under LPS stimulation, with PLIN1 identified as a significantly upregulated component and APOA1 as a key downregulated factor compared to untreated controls. Studies have shown that APOA1 may exert its anti-inflammatory effects primarily by modulating the function of immune cells (Tao et al. Reference Tao, Tao and Wang2024). Its constituent high-density lipoproteins can block the activation of liver inflammation by LPS (Han et al. Reference Han, Onufer and Huang2021). PLIN1 may mediate wound inflammatory injury through the NF-κB signaling pathway (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Cao and Shang2024). RIG-I-like signaling pathway is known to enhance antiviral immunity by coordinating type I interferon responses (Kato et al. Reference Kato, Oh and Fujita2017); its downregulation in the LPS-treated group correlated with exacerbated jejunal inflammation. This suggests that LPS disrupts intestinal immune homeostasis by impairing RIG-I-mediated containment of both viral sensing and inflammatory cascades. Compared to the LPS group, the AKK group demonstrated significant upregulation of two immune-related pathways-the NOD-like receptor signaling pathway and RIG-I-like receptor signaling pathway, with TMEM173 as a shared upregulated gene in both pathways. Transmembrane Protein 173 (TMEM173) plays a critical role in mediating innate immune response to viral and bacterial infections (Okabe et al. Reference Okabe, Sano and Nagata2009). Furthermore, recent studies indicate that the NOD-like receptor signaling pathway is functional in adaptive immune cells and contributes to adaptive immunity (Zhou et al. Reference Zhou, Yu and Zhang2023). Consistent with these findings, our results demonstrated enhanced immune activation in the jejunum of the AKK group compared to the LPS group, as evidenced by the upregulation of TMEM173 and associated pathways. Compared to the LPS group, the Active group exhibited downregulation in drug metabolism, glutathione metabolism and PPAR signaling pathway, while retinol metabolism was significantly upregulated. Drug metabolism involves the biochemical modification of drugs, primarily mediated by cytochrome P450 (Zhao et al. Reference Zhao, Ma and Li2021). Glutathione, a pivotal antioxidant maintaining intracellular redox balance, also participates in trained immunity induction through its metabolic regulation (Ferreira et al. Reference Ferreira, Koeken and Matzaraki2021). PPAR signaling pathway is a key regulator of anti-inflammatory responses through transcriptional suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokines (Ricote and Glass Reference Ricote and Glass2007). These combined results, despite enhanced retinol metabolism, likely contributed to the reduced anti-inflammatory capacity in the Active group. Compared to the LPS group, the ribosome-related pathways and oxidative phosphorylation were significantly enriched and upregulated in the Inactive group. Zhang et al. (Reference Zhang, Wu and Qu2019) reported that genes upregulated in colon adenomas were significantly associated with ribosomal, oxidative phosphorylation-related pathways (Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Wu and Qu2019). The coordinated upregulation of these energy-intensive pathways potentially reflects compensatory mechanisms against LPS-induced cellular stress.

Figure 6. Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes (DEGs). The four comparison groups are: (A) LPS vs Control; (B) AKK vs LPS; (C) Active vs LPS; and (D) Inactive vs LPS. The analysis covers three categories: biological process (BP), cellular component (CC), and molecular function (MF).

GO enrichment analysis revealed a significant upregulation of the defense response to virus pathway in the AKK group compared to the LPS group. Combined with the KEGG results, this indicated that gavage of live AKK bacteria along with their culture medium alleviates LPS-induced intestinal stress by enhancing antiviral defense and modulating innate immune responses. However, the Active group showed downregulation in cellular response to xenobiotic stimulus and oxidoreductase function. Integrating these findings with the observed suppression of PPAR signaling and glutathione metabolism, our data suggested that gavage of live AKK bacteria without culture medium has limited anti-inflammatory capacity, potentially due to compromised detoxification capacity and redox balance. Oxidative phosphorylation, a structural constituent of the ribosome and oxidoreductase activity were upregulated in the Inactive group compared to the LPS group. Mitochondrial ribosomes are essential for translating oxidative phosphorylation components, while tumor cells exhibit hyperactive ribosome biogenesis to meet their biosynthetic demands (Pecoraro et al. Reference Pecoraro, Pagano and Russo2021). Combined with prior findings, these data suggested that the Inactive group exhibited compromised resistance to LPS-induced inflammation and displayed metabolic signatures suggestive of oncogenic predisposition.

While studies report that AKK reduces LPS-induced intestinal stress (Hu et al. Reference Hu, Zhou and Lin2025), our findings revealed that AKK, with its culture medium, enhanced intestinal immunity more effectively than AKK alone. This disparity may be related to bioactive components in the culture medium, such as SCFAs and extracellular vesicles. It has been shown that AKK produces SCFAs by degrading mucins (Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Li and Cheng2019), and SCFAs play a role in intestinal immunity and anti-inflammation (Sam et al. Reference Sam, Ling and Yew2021). Both SCFAs and extracellular vesicles can improve gut barrier function via Occludin-AMPK signaling (Chelakkot et al. Reference Chelakkot, Choi and Kim2018; Voltolini et al. Reference Voltolini, Battersby and Etherington2012). Further studies are needed to clarify the exact mechanisms.

Nevertheless, some limitations of this study should be considered. Our investigation utilized a single strain of AKK (ATCC BAA-835), and the observed benefits may not be entirely generalizable, as the functional properties of probiotics can be highly strain-specific. Future comparative studies using multiple strains would be valuable. Additionally, the acute LPS challenge model, while effective for inducing an inflammatory response, represents a simplified simulation of the complex, multifactorial gut health challenges found in commercial poultry production. Therefore, the protective effects of AKK warrant further validation in more diverse and commercially relevant stress or disease models. These limitations provide a clear direction for future research to build upon our foundational findings.

Conclusions

In this study, we investigated the effects of different preparations of AKK on LPS-induced intestinal stress in broilers through gut microbiome and jejunal transcriptome analysis. All three groups stabilized gut microbiota in broilers under LPS challenge, especially the AKK with its culture medium group. Oral administration of live AKK with its culture medium effectively alleviated LPS-induced jejunal stress by enhancing antiviral defense pathways, whereas live AKK without culture medium exhibited weaker anti-inflammatory effects. In contrast, heat-inactivated AKK without medium failed to mitigate jejunal stress, underscoring the importance of bacterial viability and culture medium components for therapeutic efficacy.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study (Reference No. PRJNA1194789, PRJNA1202580) can be found at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/1194789, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/1202580.

Author Contributions

R.Z. drafted the manuscript. J.T., Y.J. and L.O. conducted the study and collected samples. C.L. and Z.Z. analyzed the samples and performed data analysis. X.F. reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing Financial Interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Ethical Standards

This experimental protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee and conducted under the supervision of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Foshan University (#FOSU202421002, Foshan, China).