1. Introduction

There is mixed public and private ownership of healthcare facilities in nearly all healthcare systems (Montagu Reference Montagu2021). Private healthcare providers are ‘individuals and organizations that are neither owned nor directly controlled by governments’ (WHO 2021). The opposite holds for public healthcare providers, which governments own or directly control. Private healthcare providers can be further subcategorised according to their financial objectives as for-profit (FP) or not-for-profit (NFP), with FP healthcare providers primarily driven by financial returns to shareholders, while NFP providers are motivated by reinvesting surplus revenues to improve quality of care (Horwitz Reference Horwitz2005).

Economists have emphasised the relationship between healthcare provider ownership status and dimensions of health system performance, such as efficiency, accessibility, and quality of care, relies upon the incentives, motivations, and information asymmetries of different agents and principals involved in healthcare (Moscelli Reference Moscelli2018; Brekke et al. Reference Brekke, Siciliani and Rune Straume2011). Assuming that private healthcare providers are motivated more by financial gains compared to public healthcare providers, they may engage in behaviours such as cream-skimming or quality skimping to maximise profits (Ellis Reference Ellis1998). These incentives may also be stronger in FP than NFP healthcare providers, although the literature to date does not consistently distinguish between FP and NFP status among providers.

Empirical evidence examining the relationship between healthcare provider ownership status and performance has been mixed. Herrera et al. (Reference Herrera, Rada, Kuhn-Barrientos and Barrios2014) was a previous umbrella review that summarised evidence on the relationship between healthcare provider ownership status and quality of care in high-income countries (HICs) and low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) from nine systematic reviews (Herrera et al. Reference Herrera, Rada, Kuhn-Barrientos and Barrios2014). They noted that private FP providers tended to have worse outcomes than their private NFP counterparts, but emphasised that limited comparisons between public and private (either FP or NFP) healthcare providers existed. Focusing specifically on HICs, the evidence base has developed further. Kruse et al. (Reference Kruse, Stadhouders, Adang, Groenewoud and Jeurissen2018) focused exclusively on evidence from European countries. They found that patients with higher socioeconomic backgrounds have better access to private hospital provision. Still, the evidence on the quality of care was too diverse to make a conclusive statement (Kruse et al. Reference Kruse, Stadhouders, Adang, Groenewoud and Jeurissen2018). Borsa et al. (Reference Borsa, Bejarano, Ellen and Dov Bruch2023) evaluated trends in private equity ownership and found evidence predominantly from the United States (US), which suggested that private equity ownership was associated with increased costs and mixed to harmful impacts on healthcare quality (Borsa et al. Reference Borsa, Bejarano, Ellen and Dov Bruch2023). Recently, Goodair and Reeves (Reference Goodair and Reeves2024) focused on the effect of healthcare privatisation on the quality of care. They found evidence that a change in ownership status from public to private for healthcare facilities in the US, South Korea, Croatia, and Germany was associated with increased profits and mixed impacts on quality (Goodair and Reeves Reference Goodair and Reeves2024). Moreover, they also found evidence from England suggesting that aggregate increases in publicly funded care in private healthcare facilities at the regional level were associated with worse patient health outcomes. Considering the significant development of the evidence-base on healthcare provider ownership and performance over the last decade, there is a need to collate recent evidence on this relationship to inform policy and future research on healthcare provision and financing.

We aim to provide a comprehensive assessment of evidence on the relationship between healthcare provider ownership and measures of health system performance in HICs. We focus specifically on HICs as the health system arrangements and relationship between public and private healthcare sectors vary significantly between HICs and LMICs. Moreover, analysing both within a single review would be challenging due to the breadth of evidence generated in both HICs and LMICs, and presenting results together could obscure context-specific patterns and reduce the validity of cross-country comparisons.

2. Methods

We chose to conduct an umbrella review because numerous systematic reviews on health system performance and provider ownership already exist, and this approach allows us to synthesise the large body of evidence previously collected and assessed across multiple reviews and meta-analyses (Belbasis et al. Reference Belbasis, Bellou and Ioannidis2022). We followed the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) guidelines for umbrella reviews in the design and execution of the review (Aromataris et al. Reference Aromataris, Fernandez, Godfrey, Holly, Khalil and Tungpunkom2015), and the PRISMA guidelines for reporting purposes (Page et al. Reference Page, Moher and Bossuyt2021). Our study protocol was pre-registered on PROSPERO prior to commencing the review process (CRD42024608140) (Anderson, Wimmer, et al. Reference Anderson, Wimmer and Friebel2024).

2.1. Eligibility criteria

We included any systematic review that captured studies examining the performance of healthcare providers based upon ownership status in HICs (defined according to the Fiscal Year 2026 World Bank classification, (World Bank 2025)). Ownership status is typically categorised as public or private, and NFP or FP if classified as private. Review types included systematic reviews, systematised reviews, integrative reviews, realist reviews, umbrella reviews, meta-ethnography reviews, meta-analyses, mixed-methods reviews, critical reviews, and state-of-the-art reviews. Performance was conceptualised according to the following dimensions: health outcomes, patient safety, patient satisfaction, accessibility, efficiency, workforce outcomes, and financial performance.

We excluded scoping or narrative reviews, any reviews focusing on LMICs, and non-English language reviews. Existing umbrella reviews with overlapping scope were reviewed, and relevant reviews were extracted for inclusion if not identified elsewhere. We made no restrictions based on the healthcare systems sector, and therefore, we included studies focusing on primary, secondary, mental health, and long-term care settings. We also made no exclusion based on types of studies (i.e. quantitative or qualitative) included within identified reviews.

2.2. Search strategy and data selection process

We adapted our search strategy from Herrera et al. (Reference Herrera, Rada, Kuhn-Barrientos and Barrios2014), applied to Medline, EMBASE, and EconLit to identify reviews published until 29 October 2024 (see Appendix 1 for search strategy). We limited our search strategy to three databases, as it has been shown that searching at least two databases improves coverage and recall and decreases the risk of missing eligible studies when conducting reviews (Ewald et al. Reference Ewald, Klerings and Wagner2022).

Two reviewers (MA, SW) independently screened all records based on their titles and abstracts to identify relevant reviews assessed against eligibility criteria. Any disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer (RF). After retrieving the full-text articles for all potentially eligible reviews, each full-text review was screened for eligibility by both reviewers (MA, SW). Consensus of disagreements was resolved by the third reviewer (RF).

We reviewed the reference list of all identified articles for additional reviews not captured by our search strategy. Additionally, we conducted a grey literature search on Google Scholar, reviewing the first 300 results as recommended by (Haddaway et al. Reference Haddaway, Collins, Coughlin and Kirk2015). Records retrieved from databases were organised and managed using Rayyan Systems (Ouzzani et al. Reference Ouzzani, Hammady, Fedorowicz and Elmagarmid2016).

Two primary reviewers (MA, SW) conducted a quality assessment using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) systematic review checklist (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, n.d.). Then they discussed to reach a consensus on the quality of each review. All questions within the CASP checklist were included, except for ‘Are the benefits worth the harms and costs?’, which was deemed irrelevant to our umbrella review. This tool was specifically designed to assess a range of dimensions of quality in systematic reviews, including whether the review addresses a clearly focused question, includes all relevant studies, and assesses the potential bias of included studies. Once quality assessment was complete, reviews classified as low quality were excluded from further analysis. Reviews were categorised as low quality if the response to either of the first two questions was negative: Did the review address a clearly focused question? Did the authors look for the right type of papers? We also excluded studies if the answers to more than three other questions were negative. Reviews were categorised as high quality if there were either one or no negative responses to questions included in the quality assessment. Reviews were categorised as moderate quality if they did not meet high- or low-quality criteria.

A potential limitation of umbrella reviews is that some primary studies may be included in multiple systematic reviews, inflating the weight of evidence and biasing conclusions. To quantify the degree of overlap in primary studies across systematic reviews within an umbrella review, we estimated the corrected covered area (CCA) using a citation matrix of all identified studies and inclusion within each individual systematic review (Hennessy and Johnson Reference Hennessy and Johnson2020). Following guidance in Pieper et al (Reference Pieper, Antoine, Mathes, Neugebauer and Eikermann2014), the following thresholds were used to quantify the extent of overlap (Pieper et al. Reference Pieper, Antoine, Mathes, Neugebauer and Eikermann2014): slight overlap: 0% to 5%; moderate overlap: 6% to 10%; high overlap: 11% to 15%; and very high overlap: greater than 15%.

2.3. Data extraction and thematic analysis

Two reviewers independently extracted data for each literature review using a pre-determined data extraction table. Information included the focus of the review; dimensions of health system performance examined (i.e. health outcomes, patient safety, patient satisfaction, accessibility, efficiency, workforce outcomes, financial performance); number of types of studies; publication dates of included studies; countries and sectors analysed (i.e. hospital care, primary care, long-term care); and main findings. Health system performance dimensions were based on intermediate and final goals contained within the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies health system performance assessment framework (Papanicolas et al. Reference Papanicolas, Rajan, Karanikolos, Soucat and Figueras2022). Thematic narrative synthesis was conducted according to different dimensions of health system performance (Table 1). Where possible, we narratively compared and contrasted findings from different reviews that had a similar focus, contextual background, or objective. We opted not to undertake a meta-analysis or integrate findings statistically due to the heterogeneity of findings.

Table 1. Dimensions of health system performance and metrics examined

3. Results

Our search strategy identified 1,862 reviews after de-duplication. Following abstract, title, and full-text screening, we identified 31 reviews focused on the relationship between healthcare provider ownership status and health system performance (Figure 1). One additional review was identified through grey literature searches (Fletcher et al. Reference Fletcher, Eddama and Anderson2024).

Figure 1. PRISMA flowchart diagram.

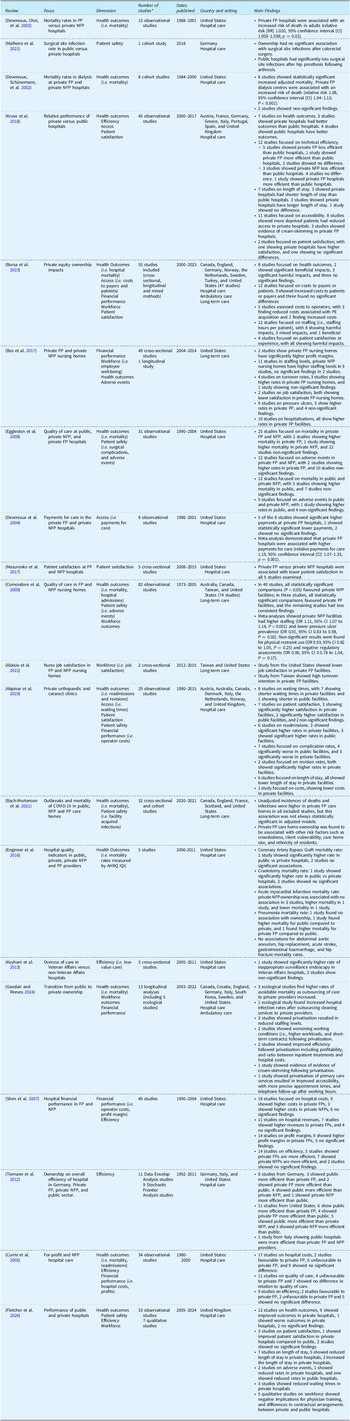

The quality of identified reviews varied considerably (Appendix 2). Ten reviews were classified as low-quality and therefore removed from subsequent analyses. Eleven reviews were classified as medium quality, and 9 were classified as high quality. Two existing umbrella reviews were excluded after cross-referencing to ensure they contained no additional literature reviews not identified within our search strategy (Herrera et al. Reference Herrera, Rada, Kuhn-Barrientos and Barrios2014; Bambra et al. Reference Bambra, Garthwaite and Hunter2014). Common quality concerns raised among low-quality reviews included no quality assessment of identified studies (8 reviews), unclear inclusion criteria or search strategies (6 reviews), and unclear research questions (3 reviews). In total, 20 reviews were synthesised thematically according to different health system dimensions (Table 2). This included 14 reviews focused on hospital care (Kruse et al. Reference Kruse, Stadhouders, Adang, Groenewoud and Jeurissen2018; Fletcher et al. Reference Fletcher, Eddama and Anderson2024; Currie et al. Reference Currie, Donaldson and Lu2003; Tiemann et al. Reference Tiemann, Schreyögg and Busse2012; Shen et al. Reference Shen, Eggleston, Lau and Schmid2007; Keyhani et al. Reference Keyhani, Falk, Howell, Bishop and Korenstein2013; Engineer et al. Reference Engineer, Winters and Weston2016; Akpinar et al. Reference Akpinar, Kirwin, Tjosvold, Chojecki and Round2023; Mazurenko et al. Reference Mazurenko, Collum, Ferdinand and Menachemi2017; Devereaux, Schünemann, et al. Reference Devereaux, Schünemann and Ravindran2002; Eggleston et al. Reference Eggleston, Shen, Lau, Schmid and Chan2008; Devereaux, Choi, et al. Reference Devereaux, Choi and Lacchetti2002; Malheiro et al. Reference Malheiro, Peleteiro and Correia2021; Devereaux et al. Reference Devereaux, Heels-Ansdell and Lacchetti2004), and 4 reviews focused on long-term care (Bach-Mortensen et al. Reference Bach-Mortensen, Verboom, Movsisyan and Degli Esposti2021; Aloisio et al. Reference Aloisio, Coughlin and Squires2021; Comondore et al. Reference Comondore, Devereaux and Zhou2009; Bos et al. Reference Bos, Boselie and Trappenburg2017). Two reviews incorporated evidence from mixed settings, with inclusion criteria not restricted to specific sectors (Borsa et al. Reference Borsa, Bejarano, Ellen and Dov Bruch2023; Goodair and Reeves Reference Goodair and Reeves2024).

Table 2. Main results

Note: Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Inpatient Quality Indicators (IQI). For-profit (FP). Not-for-profit (NFP). *This refers to number of studies relevant to relationship between ownership and performance of healthcare providers within the identified review.

In total, 543 studies were extracted across the 20 systematic reviews (Appendix 3). 474 studies were uniquely included, and 621 total study inclusions existed across the systematic reviews. This meant the percentage overlap was 12.71% (69/543), and the CCA was 0.76%. Therefore, the extent of overlap was classified as minor, and we excluded no systematic reviews from our thematic narrative analysis.

3.1. Health outcomes

Devereaux, Choi, et al. (Reference Devereaux, Choi and Lacchetti2002) and Devereaux, Schünemann, et al. (Reference Devereaux, Schünemann and Ravindran2002b) undertook a meta-analysis of studies from the US on private FP and NFP hospitals (Devereaux, Choi, et al. Reference Devereaux, Choi and Lacchetti2002), and dialysis centres (Devereaux, Schünemann, et al. Reference Devereaux, Schünemann and Ravindran2002) with both studies showing a higher mortality rate in FP hospitals. Currie et al. (Reference Currie, Donaldson and Lu2003), focused on a subset of studies from Devereaux, Choi, et al. (Reference Devereaux, Choi and Lacchetti2002) and found conflicting evidence on mortality rates in private FP and NFP private hospitals, and emphasised that the location of FP private hospitals may be driving differences in mortality rates rather than ownership status (Currie et al. Reference Currie, Donaldson and Lu2003). Eggleston et al. (Reference Eggleston, Shen, Lau, Schmid and Chan2008) undertook a meta-regression of 31 studies focused on comparing mortality rates in private FP compared to NFP hospitals in the US, and public and private NFP hospitals (Eggleston et al. Reference Eggleston, Shen, Lau, Schmid and Chan2008). However, pooled estimates of ownership effects showed no consistent relationship with mortality rates when using different data sources or analysis time frames. Engineer et al. (Reference Engineer, Winters and Weston2016) focused on hospital mortality rates for certain conditions defined by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Inpatient Quality Indicators (IQI). They found no consistent relationship with ownership status when comparing public and private FP hospitals, and public and private NFP hospitals (Engineer et al. Reference Engineer, Winters and Weston2016). Although several studies included within Engineer et al. (Reference Engineer, Winters and Weston2016) used hospital-level data without adjustment for patient-level differences in case-mix. Borsa et al. (Reference Borsa, Bejarano, Ellen and Dov Bruch2023) focused on the impact of private equity ownership and found mixed effects on hospital mortality, unplanned admissions, and fertility outcomes (Borsa et al. Reference Borsa, Bejarano, Ellen and Dov Bruch2023). Kruse et al. (Reference Kruse, Stadhouders, Adang, Groenewoud and Jeurissen2018) summarised evidence on ownership status and hospital performance in Europe (Kruse et al. Reference Kruse, Stadhouders, Adang, Groenewoud and Jeurissen2018), finding reduced mortality in public versus private FP hospitals in studies from France (Gobillon and Milcent Reference Gobillon and Milcent2016), and reduced mortality in private hospitals versus public hospitals in Germany (Tiemann and Schreyögg Reference Tiemann and Schreyögg2009) and Italy (Moscone et al. Reference Moscone, Tosetti and Vittadini2012). The same study also found evidence of increased readmissions in private compared to public hospitals in France (Gusmano et al. Reference Gusmano, Rodwin, Weisz, Cottenet and Quantin2015), and reduced readmissions in private compared to public hospitals in Italy (Moscone et al. Reference Moscone, Tosetti and Vittadini2012; Berta et al. Reference Berta, Seghieri and Vittadini2013). Akpinar et al. (Reference Akpinar, Kirwin, Tjosvold, Chojecki and Round2023) focused on evidence from orthopaedic care and cataract surgery and found mixed evidence on readmission rates between private and public hospitals (Akpinar et al. Reference Akpinar, Kirwin, Tjosvold, Chojecki and Round2023). Notably, two studies focused on revision rates for orthopaedic surgery and found higher revision rates in private hospitals in Australia (Harris et al. Reference Harris, Cuthbert, Lorimer, de Steiger, Lewis and Graves2019), and the Netherlands (Tulp et al. Reference Tulp, Kruse, Stadhouders and Jeurissen2020). Fletcher et al. (Reference Fletcher, Eddama and Anderson2024) reviewed evidence from the United Kingdom and found twelve studies focused on hospital mortality and readmission rates (Fletcher et al. Reference Fletcher, Eddama and Anderson2024). Nine studies consistently showed better health outcomes in private hospitals, one study found increased readmission rates in private hospitals (Bannister et al. Reference Bannister, Ahmed, Bannister, Bray, Dillon and Eastaugh-Waring2010), and two studies found no significant differences when using instrumental variable approaches to adjust for unobservable differences in case-mix (Moscelli et al. Reference Moscelli2018; Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Friebel, Maynou, Kyriopoulos, McGuire and Mossialos2024).

Comondore et al. (Reference Comondore, Devereaux and Zhou2009) focused on FP and NFP nursing homes. They identified four studies on mortality rates, one finding higher rates in FP nursing homes, and three with non-significant findings (Comondore et al. Reference Comondore, Devereaux and Zhou2009). Three studies focused on hospital admission rates, one finding higher rates in FP hospitals and two with non-significant findings (Comondore et al. Reference Comondore, Devereaux and Zhou2009). Bach-Mortensen et al. (Reference Bach-Mortensen, Verboom, Movsisyan and Degli Esposti2021) focused on COVID-19 mortality and found that unadjusted incidences of deaths were higher in FP care homes in all included studies. Still, this association was not always statistically significant in adjusted models (Bach-Mortensen et al. Reference Bach-Mortensen, Verboom, Movsisyan and Degli Esposti2021).

3.2. Patient safety

Eggleston et al. (Reference Eggleston, Shen, Lau, Schmid and Chan2008) examined the association between hospital ownership status and adverse events, including medication errors and surgical complications (Eggleston et al. Reference Eggleston, Shen, Lau, Schmid and Chan2008). Meta-analysis of pooled estimates showed no consistent findings between private FP and NFP hospitals and public and private NFP hospitals. Malheiro et al. (Reference Malheiro, Peleteiro and Correia2021) focused on hospital-level determinants of surgical site infections (SSIs) (Malheiro et al. Reference Malheiro, Peleteiro and Correia2021). They identified one study from Germany that showed public hospitals have significantly lower rates of SSI after hip surgery than private hospitals (Schröder et al. Reference Schröder, Behnke, Geffers and Gastmeier2018). However, the same study showed no significant findings when analysing SSI following colorectal surgery. Akpinar et al. (Reference Akpinar, Kirwin, Tjosvold, Chojecki and Round2023) focused on surgical complication rates in orthopaedic and cataract surgery, with mixed findings between public and private hospitals (Akpinar et al. Reference Akpinar, Kirwin, Tjosvold, Chojecki and Round2023). Fletcher et al. (Reference Fletcher, Eddama and Anderson2024) identified two studies that examined adverse events in public and private hospitals (Fletcher et al. Reference Fletcher, Eddama and Anderson2024); one found lower rates in private hospitals (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Friebel, Maynou, Kyriopoulos, McGuire and Mossialos2024), and the other found higher rates in private hospitals (Bannister et al. Reference Bannister, Ahmed, Bannister, Bray, Dillon and Eastaugh-Waring2010).

Comondore et al. (Reference Comondore, Devereaux and Zhou2009) undertook a meta-analysis showing significantly lower pressure ulcer prevalence in NFP versus FP nursing homes (Comondore et al. Reference Comondore, Devereaux and Zhou2009), although non-significant findings were found for physical restraint use and negative regulatory assessments. Bach-Mortensen et al. (Reference Bach-Mortensen, Verboom, Movsisyan and Degli Esposti2021) found higher unadjusted COVID-19 infections in private FP versus NFP nursing homes. Still, they emphasised that private FP care home ownership was also associated with other risk factors such as crowdedness, client vulnerability, care home size, and ethnicity of residents (Bach-Mortensen et al. Reference Bach-Mortensen, Verboom, Movsisyan and Degli Esposti2021).

3.3. Patient experience

Mazurenko et al. (Reference Mazurenko, Collum, Ferdinand and Menachemi2017) examined hospital determinants of patient satisfaction measured using the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS). They identified five studies focused on hospital ownership, showing lower patient satisfaction in private FP versus NFP hospitals (Mazurenko et al. Reference Mazurenko, Collum, Ferdinand and Menachemi2017). Borsa et al. (Reference Borsa, Bejarano, Ellen and Dov Bruch2023) examined the impacts of private equity ownership on patient satisfaction or experience measures and found that four studies showed significant adverse consequences (Borsa et al. Reference Borsa, Bejarano, Ellen and Dov Bruch2023). Kruse et al. (Reference Kruse, Stadhouders, Adang, Groenewoud and Jeurissen2018) identified two studies on patient satisfaction from the United Kingdom, with one study showing higher patient satisfaction rates in private versus public hospitals (Owusu-Frimpong et al. Reference Owusu-Frimpong, Nwankwo and Dason2010), and the other showed no significant relationship (Pérotin et al. Reference Pérotin, Zamora, Reeves, Bartlett and Allen2013). Akpinar et al. (Reference Akpinar, Kirwin, Tjosvold, Chojecki and Round2023) examined patient satisfaction for orthopaedic care and cataract surgery (Akpinar et al. Reference Akpinar, Kirwin, Tjosvold, Chojecki and Round2023), and found three studies showing higher patient satisfaction in private hospitals in the Netherlands (Kruse et al. Reference Kruse, Groenewoud, Atsma, van der Galiën, Adang and Jeurissen2019), Australia (Pager and McCluskey Reference Pager and McCluskey2004), and Denmark (Andersen and Jakobsen Reference Andersen and Jakobsen2011), two studies with higher patient satisfaction in public facilities in Australia (Adie et al. Reference Adie, Dao, Harris, Naylor and Mittal2012; Naylor et al. Reference Naylor, Descallar and Grootemaat2016), and two studies from the United Kingdom with non-significant findings (Perotin et al. Reference Pérotin, Zamora, Reeves, Bartlett and Allen2013; Browne et al. Reference Browne, Jamieson, Lewsey, van der Meulen, Copley and Black2008).

3.4. Accessibility

Kruse et al. (Reference Kruse, Stadhouders, Adang, Groenewoud and Jeurissen2018) found consistent evidence that private hospitals provide access to more affluent patients in eight studies and engage in cream-skimming to provide care to less complex patients in three studies (Kruse et al. Reference Kruse, Stadhouders, Adang, Groenewoud and Jeurissen2018). Goodair and Reeves (Reference Goodair and Reeves2024) used longitudinal data to assess the impact of ownership status. They found evidence to suggest that private hospitals engaged in cream-skimming following conversion, taking on more profitable Medicaid patients (Goodair and Reeves Reference Goodair and Reeves2024). Akpinar et al. (Reference Akpinar, Kirwin, Tjosvold, Chojecki and Round2023) examined waiting times for orthopaedic and cataract surgery. They found eight studies, seven showing short waiting times in private hospitals and one showing shorter waiting times in public hospitals (Akpinar et al. Reference Akpinar, Kirwin, Tjosvold, Chojecki and Round2023). Fletcher et al. (Reference Fletcher, Eddama and Anderson2024) examined evidence from the United Kingdom (Fletcher et al. Reference Fletcher, Eddama and Anderson2024) and found three studies showing reduced waiting times in private versus public hospitals (Marques et al. Reference Marques, Noble, Blom and Hollingworth2014; Kelly and Stoye Reference Kelly and Stoye2020; Beckert and Kelly Reference Beckert and Kelly2021). Goodair and Reeves (2004) identified one study from Croatia that showed that the privatisation of primary care services resulted in improved accessibility, with more precise appointment times, and telephone follow-up after working hours (Hebrang et al. Reference Hebrang, Henigsberg and Erdeljic2003).

Devereaux et al. (Reference Devereaux, Heels-Ansdell and Lacchetti2004) examined the relationship between hospital ownership status and payments for care, and a meta-analysis showed private FP versus NFP hospitals had higher payments (Devereaux et al. Reference Devereaux, Heels-Ansdell and Lacchetti2004). Borsa et al. (Reference Borsa, Bejarano, Ellen and Dov Bruch2023) examined whether private equity ownership was associated with higher costs for patients or payers, with nine out of 12 studies showing higher costs for patients or payers related to private equity ownership and no significant findings in the remaining studies (Borsa et al. Reference Borsa, Bejarano, Ellen and Dov Bruch2023). In most cases, the studies identified in Devereaux et al. (Reference Devereaux, Heels-Ansdell and Lacchetti2004) and Borsa et al. (Reference Borsa, Bejarano, Ellen and Dov Bruch2023) reported no disaggregate findings according to payments by patients or payers.

3.5. Efficiency

Several reviews measured technical efficiency using data envelopment analysis (DEA) and Stochastic Frontier Analysis (SFA). Shen et al. (Reference Shen, Eggleston, Lau and Schmid2007) identified 14 studies from the US and undertook a meta-regression to establish the relationship between hospital ownership and technical efficiency, which showed no consistent findings (Shen et al. Reference Shen, Eggleston, Lau and Schmid2007). Currie et al. (Reference Currie, Donaldson and Lu2003) included many of the same studies and also found no consistent findings related to technical efficiency between private FP and NFP hospitals in the US (Currie et al. Reference Currie, Donaldson and Lu2003). Tiemann et al. (Reference Tiemann, Schreyögg and Busse2012) also found an inconsistent relationship between hospital ownership status and technical efficiency in the US and Germany (Tiemann et al. Reference Tiemann, Schreyögg and Busse2012). The same review also found one study from Italy, which showed public hospitals were more efficient than private FP and NFP providers (Daidone and D’Amico Reference Daidone and D’Amico2009). Kruse et al. (Reference Kruse, Stadhouders, Adang, Groenewoud and Jeurissen2018) identified twelve studies focused on technical efficiency and hospital ownership status from Europe, comparing either private FP hospitals with public hospitals or private NFP hospitals with public hospitals (Kruse et al. Reference Kruse, Stadhouders, Adang, Groenewoud and Jeurissen2018). These studies either found that private FP and NFP hospitals were less efficient than public hospitals or no significant differences, with the exception of one study from Germany showing private FP hospitals are more efficient than public hospitals (also identified in Goodair and Reeves (Reference Goodair and Reeves2024)) (Tiemann and Schreyögg Reference Tiemann and Schreyögg2012), and one study from Austria finding private NFP hospitals are more efficient than public hospitals (Czypionka et al. Reference Czypionka, Kraus, Mayer and Röhrling2014).

Other measures of efficiency used within reviews include hospital length of stay and the use of low-value services. Kruse et al. (Reference Kruse, Stadhouders, Adang, Groenewoud and Jeurissen2018) found seven European studies focused on length of stay, with inconsistent findings between ownership status and length of stay (Kruse et al. Reference Kruse, Stadhouders, Adang, Groenewoud and Jeurissen2018). Akpinar et al. (Reference Akpinar, Kirwin, Tjosvold, Chojecki and Round2023) identified six studies focused on orthopaedic and cataract surgery that all showed that the length of stay was shorter in private versus public hospitals (Akpinar et al. Reference Akpinar, Kirwin, Tjosvold, Chojecki and Round2023). Fletcher et al. (Reference Fletcher, Eddama and Anderson2024) found seven studies from the United Kingdom (Fletcher et al. Reference Fletcher, Eddama and Anderson2024), consistently showing that length of stay was lower in private versus public providers, except for one study that used an instrumental variable to account for unobserved differences in case-mix and found private hospitals had longer length of stay (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Friebel, Maynou, Kyriopoulos, McGuire and Mossialos2024; Friebel et al. Reference Friebel, Fistein, Maynou and Anderson2022). Keyhani et al. (Reference Keyhani, Falk, Howell, Bishop and Korenstein2013) examined overuse of services in public (i.e. Veteran Administration (VA) hospitals) and private hospitals in the US, and found one study showing significantly higher rates of inappropriate surveillance endoscopy in VA hospitals, and two studies with non-significant findings (Keyhani et al. Reference Keyhani, Falk, Howell, Bishop and Korenstein2013). Fletcher et al. (Reference Fletcher, Eddama and Anderson2024) also included two studies on low-value care, one showing private hospitals reduced low-value services at a lower rate than public hospitals following implementation of a national disinvestment initiative (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Molloy, Maynou, Kyriopoulos, McGuire and Mossialos2023), and one showing private hospitals increased provision of privately funded low-value services following withdrawal of publicly funded care (Anderson Reference Anderson2023).

3.6. Workforce outcomes

Goodair and Reeves (Reference Goodair and Reeves2024) identified four studies that examined workforce implications following the privatisation of hospitals, with three studies showing decreased staffing levels, and one study showing employment conditions declined with more short-term contracts, higher workload, and more unequal pay between physicians and other workers (Goodair and Reeves Reference Goodair and Reeves2024). Borsa et al. (Reference Borsa, Bejarano, Ellen and Dov Bruch2023) examined the impact of private equity ownership on staffing levels, such as the number of full-time equivalent staffing numbers per patient treated, and identified 12 studies, eight of which showed harmful impacts, three had mixed impacts, and one showed beneficial impacts (Borsa et al. Reference Borsa, Bejarano, Ellen and Dov Bruch2023). Fletcher et al. (Reference Fletcher, Eddama and Anderson2024) synthesised findings from five qualitative studies on the workforce implications of private provision of publicly funded care in the United Kingdom (Fletcher et al. Reference Fletcher, Eddama and Anderson2024), which emphasised potential negative consequences for physician training, misalignment of governance arrangements between public and private hospitals, and differences in contracting arrangement (such as the use of temporary contracts in private hospitals).

Comondore et al. (Reference Comondore, Devereaux and Zhou2009) provide a meta-analysis showing private NFP nursing homes were associated with higher staffing levels (Comondore et al. Reference Comondore, Devereaux and Zhou2009). Bos et al. (Reference Bos, Boselie and Trappenburg2017) examined several workforce outcomes in private FP and NFP nursing homes (Bos et al. Reference Bos, Boselie and Trappenburg2017). FP ownership was consistently associated with lower staffing levels in nine out of 11 studies, higher turnover rates in three out of four, and reduced job satisfaction in two. The remaining studies showed non-significant findings. Aloisio et al. (Reference Aloisio, Coughlin and Squires2021) identified two studies focused on private FP and NFP nursing homes, with reduced job satisfaction in private FP nursing homes in the US (Choi et al. Reference Choi, Flynn and Aiken2012), and higher turnover intention in private FP nursing homes in Taiwan (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Brown, Bowers and Chang2015).

3.7. Financial performance

Shen et al. (Reference Shen, Eggleston, Lau and Schmid2007) examined differences in financial performance between private FP and NFP hospitals in the US. They undertook a meta-regression of 40 studies focused on hospital costs, revenues, and profit margins (Shen et al. Reference Shen, Eggleston, Lau and Schmid2007). Results varied based on whether studies adjusted for a limited or broad range of confounding factors, applied log transformation to highly skewed expenditure data, and the sample size of studies. There was conflicting evidence on hospital costs, whereas the meta-regression favoured private FP hospitals when examining hospital revenues and profit margins. Currie et al. (Reference Currie, Donaldson and Lu2003) also found mixed evidence on ownership status and hospital costs (Currie et al. Reference Currie, Donaldson and Lu2003). Borsa et al. (Reference Borsa, Bejarano, Ellen and Dov Bruch2023) identified five studies that examined the impact of private equity ownership on operator costs, with three studies finding reduced operator costs associated with private equity acquisition and two studies finding increased costs (Borsa et al. Reference Borsa, Bejarano, Ellen and Dov Bruch2023). Akpinar et al. (Reference Akpinar, Kirwin, Tjosvold, Chojecki and Round2023) identified one study focused on operator costs in private and public cataract surgery providers in the Netherlands, showing lower costs in private providers (Kruse et al. Reference Kruse, Groenewoud, Atsma, van der Galiën, Adang and Jeurissen2019). There was limited evidence of the implications of the ownership status of nursing homes and financial performance. Bos et al. (Reference Bos, Boselie and Trappenburg2017) identified two studies demonstrating that private FP nursing homes had significantly higher profit margins (Bos et al. Reference Bos, Boselie and Trappenburg2017).

4. Discussion

Ownership in healthcare systems across HICs differs widely, often including a mix of public and private, FP and NFP models. The implications on healthcare system performance are unclear, restricting policymakers’ ability to effectively regulate healthcare models to enhance the quality of patient care and reduce costs. Evidence from our umbrella review shows that the relationship between hospital ownership and health outcomes was inconsistent, and varied depending on data source, health system context, and period analysed. In contrast, there was consistent evidence of higher mortality rates in private FP nursing homes than in private NFP nursing homes. There were mixed findings related to hospital ownership and patient safety indicators; however, the prevalence of certain adverse events was higher in private FP nursing homes than in private NFP counterparts. We found consistent evidence that hospital ownership was associated with worse patient satisfaction in the US, particularly with private equity ownership or acquisition. The evidence from Europe and Australia on hospital ownership and patient satisfaction was mixed.

Evidence existed on multiple dimensions of accessibility for hospital care but not for nursing homes, with private hospitals serving wealthier patients than public hospitals, and engaging in ‘cream-skimming’ to favour less complex and costly cases. Private hospitals also appeared to have shorter waiting times and charge higher payments for care to patients and payers. There was inconsistent evidence between hospital ownership and technical efficiency, although several reviews identified evidence that length of stay was generally shorter in private hospitals when compared to public hospitals, likely related to differences in patient case-mix. There was also limited evidence that the provision of low-value care was more prevalent in private rather than public hospitals. However, this literature often did not distinguish between FP private and NFP private ownership.

Privatisation and private equity ownership were associated with reduced staffing levels, higher workload, and lower job satisfaction. There was evidence that private FP nursing homes generally had lower staffing levels, higher turnover rates, and reduced job satisfaction than NFP providers. Private FP hospitals generally had higher revenues and profit margins, though evidence on hospital costs was mixed. Private equity ownership also had mixed effects on operator costs, which sometimes increased or reduced following private equity acquisition. There was limited evidence on nursing home ownership and financial performance, with existing studies, indicating that private FP nursing homes have higher profit margins.

4.1. Comparison with existing literature

We identified two previous umbrella reviews focused on the relationship between healthcare ownership and performance measures. Herrera et al. (Reference Herrera, Rada, Kuhn-Barrientos and Barrios2014) reviewed the performance of private FP, private NFP, and public healthcare providers. They identified nine systematic reviews (Herrera et al. Reference Herrera, Rada, Kuhn-Barrientos and Barrios2014), and six focused on HICs with evidence predominantly from the US (Shen et al. Reference Shen, Eggleston, Lau and Schmid2007; Devereaux, Schünemann, et al. Reference Devereaux, Schünemann and Ravindran2002; Eggleston et al. Reference Eggleston, Shen, Lau, Schmid and Chan2008; Devereaux, Choi, et al. Reference Devereaux, Choi and Lacchetti2002; Devereaux et al. Reference Devereaux, Heels-Ansdell and Lacchetti2004; Comondore et al. Reference Comondore, Devereaux and Zhou2009). The review concluded that private FP providers tended to have worse outcomes than their NFP counterparts, but emphasised that limited comparisons between public and private healthcare providers existed. Bambra et al. (Reference Bambra, Garthwaite and Hunter2014) examined how the organisation and financing of healthcare impacted equity of access (Bambra et al. Reference Bambra, Garthwaite and Hunter2014), and identified a review, rated as low-quality, which focused on how private hospital ownership impacts access to care (Braithwaite et al. Reference Braithwaite, Travaglia and Corbett2011). This review described evidence indicating that the emergence of FP providers in the US contributed to reduced access to care for the poor and uninsured (Braithwaite et al. Reference Braithwaite, Travaglia and Corbett2011).

Our umbrella review demonstrates that the evidence base has expanded considerably over the last ten years, with 20 reviews identified compared to six identified within Herrera et al. (Reference Herrera, Rada, Kuhn-Barrientos and Barrios2014). While most evidence in our review remained from the US, we found considerable evidence from Europe (including the United Kingdom, Germany, Italy, France, and the Netherlands), and Australia, suggesting that mixed public and private provision is of increasing interest to academics and funders in countries outside the US. Unsurprisingly, the evidence base on healthcare ownership and performance from countries outside the US was more heterogeneous, reflecting differences in health system organisation and financing arrangements.

4.2. Strengths and limitations

Our review provides a comprehensive synthesis of broad evidence from diverse sources to provide a concise overview of the implications of healthcare ownership across multiple dimensions of performance. However, there are several limitations to acknowledge when interpreting the findings. First, by adopting an umbrella review approach of existing reviews rather than analysing findings and quality of individual articles, we limited the scope of our work. We may have incorporated existing bias and restrictions inherent to previously published syntheses. However, we followed best practice by adopting the JBI guidelines for umbrella reviews to promote consistency and ensure the quality of our findings. Second, our review may have discounted more recently published evidence on this topic drawn from individual studies published beyond the search periods of identified systematic reviews. However, this is an unavoidable limitation inherent to any umbrella review as there is a time lag between when primary studies are published, when they are synthesised in systematic reviews, and when these systematic reviews are included in umbrella reviews. Third, we summarised findings from a broad range of systematic reviews and meta-analyses, and differences in methodologies, populations, and outcomes across studies may introduce inconsistencies and reduce comparability. We addressed this concern by adopting a comprehensive and transparent data extraction process and comparing and contrasting findings based upon sector, health system contexts, and performance measures analysed. Fourth, we excluded 10 reviews from data extraction and synthesis as they were rated low quality, though they may have provided additional insights. However, their scope and remit overlapped with many retained reviews, likely limiting the impact of their inclusion on our overall findings. Fifth, although many Eastern European countries are classified as HICs by the World Bank, we found no systematic reviews analysing these settings, which may limit the geographical representativeness of our findings. Sixth, differences in reimbursement mechanisms between public and private hospitals were not explicitly addressed in the included reviews. As payment systems may vary across and within countries, incentives for length of stay and efficiency may differ irrespective of ownership status. This may partly explain the heterogeneity of findings. Finally, there was overlap between systematic reviews included within our narrative synthesis. However, the extent of overlap was quantified as low using the CCA and not considered necessary to exclude any systematic review (Pieper et al. Reference Pieper, Antoine, Mathes, Neugebauer and Eikermann2014).

4.3. Policy implications and directions for future research

While healthcare ownership and performance evidence were mixed for several measures, consistent relationships existed in specific contexts or sectors. These include higher mortality rates and adverse events in private FP than private NFP nursing homes (Bach-Mortensen et al. Reference Bach-Mortensen, Verboom, Movsisyan and Degli Esposti2021; Comondore et al. Reference Comondore, Devereaux and Zhou2009), lower patient satisfaction in private FP than private NFP hospitals in the US (Borsa et al. Reference Borsa, Bejarano, Ellen and Dov Bruch2023; Mazurenko et al. Reference Mazurenko, Collum, Ferdinand and Menachemi2017), evidence of selecting less costly and complex patients (i.e. cream-skimming) in private hospitals (Kruse et al. Reference Kruse, Stadhouders, Adang, Groenewoud and Jeurissen2018; Akpinar et al. Reference Akpinar, Kirwin, Tjosvold, Chojecki and Round2023), higher payments for care in private FP than in private NFP hospitals in the US (Borsa et al. Reference Borsa, Bejarano, Ellen and Dov Bruch2023; Devereaux et al. Reference Devereaux, Heels-Ansdell and Lacchetti2004), and worse workforce outcomes in private FP than private NFP hospitals (Borsa et al. Reference Borsa, Bejarano, Ellen and Dov Bruch2023; Goodair and Reeves Reference Goodair and Reeves2024), and nursing homes (Aloisio et al. Reference Aloisio, Coughlin and Squires2021; Comondore et al. Reference Comondore, Devereaux and Zhou2009; Bos et al. Reference Bos, Boselie and Trappenburg2017). To mitigate the possible negative implications of private FP providers, in comparison with public providers, policymakers, and regulators ought to adopt standardised measures that aim to ensure equity, quality, and accountability, while still allowing private providers to contribute to service delivery. These include measures that increase transparency, such as mandatory reporting of outcomes (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Cherla, Wharton and Mossialos2020), audits, and inspections, financial regulations such as risk-adjusted payment mechanisms to address cream-skimming, particularly when private providers serve publicly funded patients (Ellis and McGuire Reference Ellis and McGuire1990), or more intrusive measures such as profit caps or higher payments for public providers (Mason 2010). Similarly, to address workforce-related concerns, regulators may consider introducing and enforcing measures such as minimum staffing ratios, training requirements, and parity clauses, particularly for private providers funded through public contracts.

There were noticeable gaps in our literature, including evidence related to ambulatory care and mental health settings. We identified limited evidence about ambulatory care, including one study on ambulatory care in Croatia (Hebrang et al. Reference Hebrang, Henigsberg and Erdeljic2003), and one on ambulatory surgical clinics (Bruch et al. Reference Bruch, Nair-Desai, John Orav and Tsai2022). However, an increasing trend of private equity acquisitions of ambulatory care clinics in Germany, Ireland, the United Kingdom, Sweden, and the Netherlands has been described, which has not been subject to robust evaluation (Rechel et al. Reference Rechel, Tille and Groenewegen2023; Tille Reference Tille2023). There are also several countries with mixed public and private provision of mental health services (Younès et al. Reference Younès, Hardy-Bayle, Falissard, Kovess, Chaillet and Gasquet2005; Bjørngaard et al. Reference Bjørngaard, Garratt, Gråwe, Bjertnaes and Ruud2008; Leslie and Rosenheck Reference Leslie and Rosenheck2000), and while we identified one review focused on mental health settings, this was rated as low-quality (Rosenau and Linder Reference Rosenau and Linder2003). Therefore, there is a need for a high-quality synthesis of evidence related to potential comparative differences in quality of care and performance in this sector based on ownership status. More broadly, classification of private providers as FP or NFP was inconsistent within the evidence identified in our umbrella review. As the motivations and impact of incentives have been shown to vary significantly between private FP and NFP providers in many healthcare contexts (Herrera et al. Reference Herrera, Rada, Kuhn-Barrientos and Barrios2014; Borsa et al. Reference Borsa, Bejarano, Ellen and Dov Bruch2023; Kruse et al. Reference Kruse, Groenewoud, Atsma, van der Galiën, Adang and Jeurissen2019), it is important this distinction is consistently made when examining the implications of ownership models for health system performance.

5. Conclusion

This review provides a comprehensive synthesis of evidence related to the relationship between healthcare provider ownership and health system performance in HICs. While mixed evidence existed for several performance dimensions, we found more consistent evidence that private FP provision of healthcare negatively impacts patient outcomes, accessibility, and workforce. However, the variation in findings among other performance dimensions emphasises the need for a robust and effective regulatory system that examines the comparative performance of private FP, private NFP, and public healthcare providers.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1744133125100315.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to two anonymous referees for their helpful comments and suggestions on earlier drafts of the paper. We are also grateful to Associate Professor Rocco Friebel and Professor Iris Wallenburg for co-editing this special issue on privatisation in healthcare. Finally, we thank Professor Michael Sparer, Professor Lawrence Brown, and Associate Professor Miriam Laugesen for convening a meeting on privatisation in healthcare at Columbia University, where this paper and others in the special issue were presented and discussed.

Financial support

Dr M Anderson is funded by the National Institute of Health and Care Research (NIHR) as a Clinical Lecturer. Professor M Sutton is an NIHR senior investigator. Cornelia Henschke holds research grants that are unrelated to the topic of this study and received no specific funding for this work. Dr Rocco Friebel is a 2025-2026 Harkness Fellow based at Columbia University and Brown University, supported by the Commonwealth Fund. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NIHR, the Department of Health and Social Care, the REAL Supply Research Unit, or the Commonwealth Fund.

Competing interests

The authors declare no relevant conflicts of interest.