Introduction

In most European countries, voluntary rates have risen considerably over time (Dekker & Broek, Reference Dekker and Broek2006). As a form of social participation, volunteering opens up opportunities for social interaction and can have a positive impact on self-rated and functional health as well as affective and cognitive wellbeing (Li & Ferraro, Reference Li and Ferraro2005; Morrow-Howell et al., Reference Morrow-Howell, Hong and Tang2009) Furthermore, voluntary engagement is essential for democracy and contributes to societal cohesion by promoting civic participation (e.g., Roth, Reference Roth2020; Verba et al., Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995). Volunteering often involves demonstrating solidarity with other people, and it is able to flexibly react to new developments and societal shocks such as the COVID-19 pandemic or the Russian invasion of Ukraine. During these events, many people were willing to help people who were most vulnerable to the pandemic or were fleeing the war (e.g., Mayer et al., Reference Mayer, Lietz, Dollmann, Siegel and Köhler2022; Spear et al., Reference Spear, Erdi, Parker and Anastasiadis2020).

At the same time, as volunteer rates have continued to rise, the number of volunteers committed to regular, time-consuming volunteering has tended to decline. The trends towards decreasing time investments in voluntary activities found for the United States (Andersen et al., Reference Andersen, Curtis and Grabb2006) have more recently also been shown for Denmark and Germany (Qvist et al., Reference Qvist, Henriksen and Fridberg2018; Kelle et al., Reference Kelle, Kausmann, Arriagada, Simonson, Kelle, Kausmann and Tesch-Römer2022a). Though the demand for volunteer labour is not infinite, it has been shown that regular volunteering with a high degree of time commitment is crucial (Alscher et al., Reference Alscher, Droß, Priller and Schmeißer2013; Handy & Srinivasan, Reference Handy and Srinivasan2005). The scarcity of volunteers' time resources in many organisations can result in the discontinuation of services and tasks, to the extent that it poses a threat to the existence of these organisations (Priemer et al., Reference Priemer, Bischoff, Hohendanner, Krebstakies, Rump, Schmitt and Krimmer2019).

Studies have sought possible explanations for the trend towards decreasing volunteers’ time contributions. Two explanations have been put forward most often: socio-economic and family life changes (Andersen et al., Reference Andersen, Curtis and Grabb2006; Rotolo & Wilson, Reference Rotolo and Wilson2004; Taniguchi, Reference Taniguchi2012; van Ingen & Dekker, Reference van Ingen and Dekker2010), and changing individual voluntary behaviour (Hustinx, Reference Hustinx2010; Hustinx & Lammertyn, Reference Hustinx and Lammertyn2003; Qvist et al., Reference Qvist, Henriksen and Fridberg2018). Firstly, the integrative effects of work and parenting on volunteer participation, discussed for their potential to create new connections, also come with time-restrictive consequences (Oesterle et al., Reference Oesterle, Johnson and Mortimer2004). Research has demonstrated that, although these activities enhance the likelihood of volunteer participation, they are likely to decrease the time invested in voluntary activities (van Ingen & Dekker, Reference van Ingen and Dekker2010). The challenge of balancing different aspects of life may have intensified, with studies noting an increased time investment in areas such as work and family life (van der Lippe et al., Reference van der Lippe, Jager and Kops2006). Furthermore, the ongoing shift from traditional male breadwinner/female carer arrangements to arrangements where both partners are gainfully employed necessitates a reorganisation of labour and family responsibilities (Trappe et al., Reference Trappe, Pollmann-Schult and Schmitt2015; van der Lippe, Reference van der Lippe2007). Secondly, voluntary behaviour has evolved over time (van Ingen, Reference van Ingen2008). Existing empirical evidence shows that there is a shift away from organisation-based volunteering and that it is linked to a reduced willingness to take on obligatory roles and functions (Clifford, Reference Clifford2020; Qvist et al., Reference Qvist, Henriksen and Fridberg2018). However, these are the very functions that traditionally encompass a high time commitment. Furthermore, voluntary behaviour may change along different paths for men and women, as women tend to engage in less organisation-bound settings to a greater extent than men due to barriers to accessing volunteer roles within formal associations and organisations (Southby et al., Reference Southby, South and Bagnall2019).

There has been little research on the association between the determinants of voluntary activity with regard to work-family life changes and voluntary behaviour. Previous studies have often treated the determinants of voluntary activity as given, disregarding how these determinants have gained or lost importance over the years (e.g., Andersen et al., Reference Andersen, Curtis and Grabb2006; Şaka, Reference Şaka2018). Moreover, many previous studies were not able to account for factors directly related to people’s voluntary behaviour (e.g., the form or scope of volunteering) due to the lack of data (Clifford, Reference Clifford2020; Jacobsen et al., Reference Jacobsen, Schieferdecker, Gerstorf, Hutter and Specht2022). To overcome these shortcomings, we use cross-sectional data from the German Survey on Volunteering (Deutscher Freiwilligensurvey–FWS). Unlike other datasets, the FWS includes information on the time spent on voluntary activities, in-depth information on voluntary tasks (e.g., the form of voluntary organisation or the function of volunteering), and information on working hours and children living in the household. Furthermore, the data was collected at five different time points (1999, 2004, 2009, 2014 and 2019) covering a period of 20 years.

The key research question of this study is: How do work-family life changes and changes in individual voluntary behaviour determine volunteers’ time contributions in the time period 1999 to 2019? Additionally, as men and women’s time in employment, family and voluntary behaviour tend to differ substantially from each other, we estimate separate models for men and women and ask: What are the gender-specific differences in how work-family changes and changes in individual voluntary behaviour determine volunteers’ time contributions in the time period 1999 to 2019?

Germany is an interesting case for studying how and why volunteers’ time contribution has changed over time. On the one hand, studies using data from the Socio-economic panel (SOEP) or German ageing survey (DEAS) have suggested a considerable increase in voluntary rates over time (Burkhardt & Schupp, Reference Burkhardt and Schupp2019; Simonson et al., Reference Simonson, Kelle, Kausmann, Tesch-Römer, Simonson, Kelle, Kausmann and Tesch-Römer2022a). Similarly, research based on the FWS indicates a notable rise in the voluntary rate from 30.9 percent in 1999 to 39.7 percent in 2019 (Simonson et al., Reference Simonson, Kelle, Kausmann, Tesch-Römer, Simonson, Kelle, Kausmann and Tesch-Römer2022a). On the other hand, a tendency towards decreased volunteers’ time contribution is evident over the last two decades (e.g., Burkhardt et al., Reference Burkhardt, Priller, Zimmer and Bundesamt2017; Henning et al., Reference Henning, Arriagada and Karnick2023). These shifts may be connected to changes in the spheres of individual voluntary behaviour and work-family life over recent years. Germany, with its historically strong emphasis on associations and organisations (Lancee & Radl, Reference Lancee and Radl2014), has experienced a diminishing importance of formal, hierarchically organised volunteering. Thus, while the opportunities to volunteer have expanded, the ways in which people volunteer are undergoing changes. Furthermore, Germany is often characterised as a familialistic regime, with extensive social regulations supporting the primary caregiver or secondary earner role (Aisenbrey & Fasang, Reference Aisenbrey and Fasang2017; Strauss, Reference Strauss2008). Similar to the gender-specific time constraints faced in the labour market, these regulations also impact gender-specific volunteer engagement (Erlinghagen et al., Reference Erlinghagen, Saka and Steffentorweihen2016). However, recent legislation promoting gender equality in the division of labour may alter the gendered nature of volunteering.

Definition of Volunteering

In our study, voluntary engagement encompasses activities that are performed voluntarily, in a community-oriented manner, take place in the public sphere, and are not aimed at material gain. This definition of volunteering aligns with the definition of civic engagement developed by the Enquete Commission “The Future of Civic Engagement” in 2002 (Deutscher Bundestag, 2002). In line with this definition, we further distinguish between two types of volunteering: formal, organisation-based volunteering and more informally, individually organised volunteering. Formal, organisation-based volunteering refers to voluntary activities within clubs or associations, trade unions, churches or religious associations, public or municipal institutions, or foundations, which typically involve long-term, membership-based commitments and hierarchical structures. More informally, individually organised volunteering refers to voluntary activities in less formalised settings such as self-help groups, initiatives, projects or self-organised groups that are typically more project-oriented, do not follow fixed rules and are less hierarchical in structure (Alscher et al., Reference Alscher, Priller and Burkhardt2021; Rehberg, Reference Rehberg2005).

It is important to note that while the definition of ‘formal volunteering’ is often studied in a similar manner, there is considerable variation in how ‘informal volunteering’ is perceived in the literature. In many studies, informal volunteering has been characterised as “unstructured giving of one’s time to friends, neighbours, or the community” (Dean, Reference Dean2022: 527), including locally based pro-social activities such as childcare for non-family children, grocery shopping for neighbours, or supporting adults outside the family (e.g., Einolf et al., Reference Smith, Stebbins, Grotz, Grotz, Einolf, Prouteau and Nezhina2016; Greenspan & Walk, Reference Greenspan and Walk2024). Other studies, however, have classified such activities as ‘informal help/support’, therefore not considering them as a form of volunteering (e.g., Choi et al., Reference Choi, Stewart and Dewey2013; Hank & Stuck, Reference Hank and Stuck2008; van Tienoven et al., Reference van Tienoven, Craig, Glorieux and Minnen2022). In our study, alongside formal volunteering, we focus on a relatively new and emerging form of individually organised volunteering in Germany that takes place in less formalised settings. Since one of the goals of this study is to address the shift from traditionally organised volunteering to more project-based and less regulated forms of volunteering, person-to-person unstructured helping activities are outside the scope of our research.

Conceptual Framework

Changes in Work and Family Life

As time resources are limited, it is plausible to assume that time spent in one sphere might influence the time capacities that can be invested in other life spheres. Thus, time spent in work or family care might affect the voluntary behaviour of individuals (Lancee & Radl, Reference Lancee and Radl2014). Following this train of thought, the role-overload theory predicts that individuals confronted with too many demands on their time will experience stress or conflict that can limit the time spent on voluntary activities (Mutchler et al., Reference Mutchler, Burr and Caro2003). Conversely, the loss of one of these roles (when retiring or when children get older) may lead to more extensive volunteering (Markham & Bonjean, Reference Markham and Bonjean1996; Oesterle et al., Reference Oesterle, Johnson and Mortimer2004). However, the ‘more-is-more’ phenomenon noted by Robinson & Godbey, (Reference Robinson and Godbey1997) suggests that volunteer activities might be complementary rather than substitutive to other roles. Some empirical research indicates that people engaged in paid or family work are also likely to show high levels of voluntary activity (Burr et al., Reference Burr, Choi, Mutchler and Caro2005; Hank & Stuck, Reference Hank and Stuck2008).

The way that involvement in different life spheres affects time contributions to volunteering might change over time. Empirical evidence shows that demands in the life spheres of work and family have increased over time (Panova et al., Reference Panova, Sulak, Bujard, Wolf and Office2017; van der Lippe, Reference van der Lippe2007). The shift to dual-earner households—and the associated increasing need to juggle paid and unpaid work—is compounded by more demanding job expectations and parenting standards (Jacobsen & Gerson, Reference Jacobsen and Gerson2004; Moen, Reference Moen2003). As the challenge of finding volunteers for long-term and time-consuming activities meets the tendencies of people to put in more hours at work and struggle to balance family and employment, we expect that:

H1

There is an overall decrease over time in the time contributions that people put into their voluntary activities.

Furthermore, we expect to find crucial work and family life changes for the German context in our observation period of 1999 to 2019, since this period was marked by numerous social and political developments. Regarding paid employment, many women entered the labour market in this time period or increasingly continued to work after a transition to motherhood (Kelle et al., Reference Kelle, Romeu Gordo and Simonson2022b). The increase in female labour force participation rates was primarily due to the expansion of part-time employment, partially enhanced by the Part-time and Fixed-term employment act (TzBfG) in 2001. As a result, employment rates have risen significantly since 1999, particularly among women, increasing from 57 percent in 1999 to 73 percent in 2019 (Statistisches Bundesamt, 2023). Overtime work has also increased among men and women (Anger, Reference Anger2006). The higher levels of gainful employment were shown to be linked to additional opportunities for engaging in voluntary activities (Strauss, Reference Strauss2008). However, previous research has shown that intensive work hours are negatively associated with time spent in other life domains (McGarvey et al., Reference McGarvey, Jochum, Davies, Dobbs and Hornung2019), in line with the roll-overload perspective. Accordingly, we hypothesise that:

H2a

Hours spent in employment are increasingly negatively associated with time contributions to voluntary activities over time.

H2b

This association becomes more pronounced for women than for men.

Furthermore, there have been considerable changes in child and family care policies in recent decades. Legislation in 2005 and 2006 promoted the expansion of day care with the aim of creating more childcare places for children under the age of three. In 2013, a legal entitlement to a childcare place was introduced for children from the age of one. In fact, the childcare rate for children under three has risen considerably since than (BMFSFJ, 2020; Federal Statistical Office, 2020). At the same time, fathers have been shown to be involved in childcare to a greater extent than previously, especially in the first years of the child's life (Bünning, Reference Bünning2016; Tamm, Reference Tamm2019). However, women are still more intensively involved in childcare than men, particularly when children are small (Kelle et al., Reference Hustinx and Lammertyn2022b). Empirical studies show that while the presence of pre-school children is associated with lower levels of volunteering, the presence of older children is linked to higher levels of volunteering (van Ingen & Dekker, Reference van Ingen and Dekker2010). Therefore, even though women still do the majority of child rearing, fathers have been more involved in family responsibilities in recent years and institutional support has been expanded. Given all that, we hypothesise that:

H3a

Overall, the presence of a pre-school child in a household becomes less negatively associated with time investments in voluntary activities.

H3b

But more so for women than for men.

Changes in Voluntary Behaviour

To analyse how people’s changing voluntary behaviours correlate with time investments in volunteering, we follow the theoretical approach suggested by Hustinx & Lammertyn, (Reference Hustinx and Lammertyn2003) who argue that modernisation and individualisation have changed the ‘style’ of volunteering. The process of modernisation and individualisation is interconnected with changing life courses towards more discontinuity and flexibility. In terms of volunteering behaviour, Hustinx & Lammertyn, (Reference Hustinx and Lammertyn2003) describe the biographical shifts by referring to ‘collective’ and ‘reflective’ styles of volunteering: Collective volunteering is embedded in collective or traditional patterns of behaviour and is defined by collective goals, commitment and organisational attachment; reflective volunteering is seen as an individualised form of volunteering which is more sporadic in nature, with weaker organisational attachment and commitment. With increasing biographical uncertainties, the authors argue that there is a shift from a collective to reflective style of volunteering. Thus, both styles of volunteering still coexist while the base of collective volunteering is weakening.

Given the more individualised and discontinuous life courses, volunteering as a ‘biographically embedded’ activity is hypothesised to change in nature and become less committal and time intensive (Hustinx, Reference Hustinx2010; Hustinx & Lammertyn, Reference Hustinx and Lammertyn2003). While literature suggests a correlation between organisation-based volunteering and volunteering in individually organised settings, with individuals engaged in one more likely to participate in the other (Cnaan & Handy, Reference Cnaan and Handy2005; Neufeind et al., Reference Neufeind, Güntert and Wehner2015), research also indicates a shift towards greater involvement in individually organised volunteering, often at the expense of formal arrangements (Karnick et al., Reference Karnick, Simonson, Hagen, Simonson, Kelle, Kausmann and Tesch-Römer2022; Qvist et al., Reference Qvist, Henriksen and Fridberg2018). Consequently, instead of traditional voluntary activities that last for years, such as voluntary board activities in a sports club, people engage to ever higher extents in voluntary activities that take place episodically, are carried out for a short period of time, take place in an self-organised setting, involve a smaller time commitment or are carried out purely digitally (Chambré, Reference Chambré2020; Ihm, Reference Ihm2017; Neufeind et al., Reference Neufeind, Güntert and Wehner2015; Rehberg, Reference Rehberg2005). This is not only a way of dealing with limited time resources, but also of organising leisure time and reconciling volunteering with other leisure activities (McGarvey et al., Reference McGarvey, Jochum, Davies, Dobbs and Hornung2019).

Up to now, there has been little research on how changes to voluntary behaviour are linked to the time spent volunteering. Previous studies have shown evidence that weakening organisational attachment goes along with declines in time investments in volunteering (Clifford, Reference Clifford2020; Qvist et al., Reference Qvist, Henriksen and Fridberg2018). It is argued that individuals may be less committed to traditionally time-consuming voluntary activities, such as board positions, with an increasing gap in volunteer time contributions between volunteers in manager and non-manager positions. Likewise, the shift in involvement from long-term, regular and intensive to short-term, irregular and incidental may play a role in decreasing time investments in volunteering over time. To account for these changes, we consider the indicators ‘individually organised or organisation-based volunteering’ and ‘with or without volunteer management position’ and analyse how time spent volunteering changes with respect to these indicators.

For Germany, both a shift towards more volunteering in individually organised settings and a decline in take ups of management positions are observed (Karnick et al., Reference Karnick, Simonson, Hagen, Simonson, Kelle, Kausmann and Tesch-Römer2022). However, the nexus between these developments and the time people invest in their voluntary activities has not been examined. Following the rationale of Hustinx & Lammertyn, (Reference Hustinx and Lammertyn2003), it may be expected that as volunteers’ organisational attachment is declining, people tend to devote ever less time to their voluntary activities. This may be particularly true for women, who have faced gender-specific barriers to accessing formal volunteer roles (Southby et al., Reference Southby, South and Bagnall2019), drawing them towards engaging in the expanding individually organised voluntary sector (Karnick et al., Reference Karnick, Simonson, Hagen, Simonson, Kelle, Kausmann and Tesch-Römer2022). Therefore, if this is true that weakening organisational attachment is associated with decreased volunteer time contributions, this link should be even more pronounced among women than among men. Given all that, we hypothesise that:

H4a

Volunteers’ weakening organisational attachment is increasingly negatively associated with time contributions to voluntary activities.

H4b

But more so for women than for men.

Data and Method

Data

The telephone survey of the German Survey on Volunteering (FWS) has been conducted five times at five-year intervals (1999, 2004, 2009, 2014 and 2019). This survey represents a cross-section of the resident population in Germany aged 14 and older. The dataset includes individuals who engage in volunteering as well as those who do not. Comparisons with population data from Microcensus suggest that the waves can be used as representative cross-sections of the German population (for more details on the data see Hameister et al., (Reference Hameister, Kelle, Kausmann, Karnick, Arriagada and Simonson2023). The analysis sample only includes people who volunteer. People of retirement age and those still undergoing school education are excluded from the sample. The 2004 survey wave is not part of the analyses as no information on the time spent on voluntary activities was collected this year. In total, the sample size is n = 21,751 (women: n = 11,273; men: n = 10,478). For the individual survey waves, the numbers of cases are as follows: 1999: n = 3231; 2009: n = 4403; 2014: n = 7308 and 2019: n = 6809.

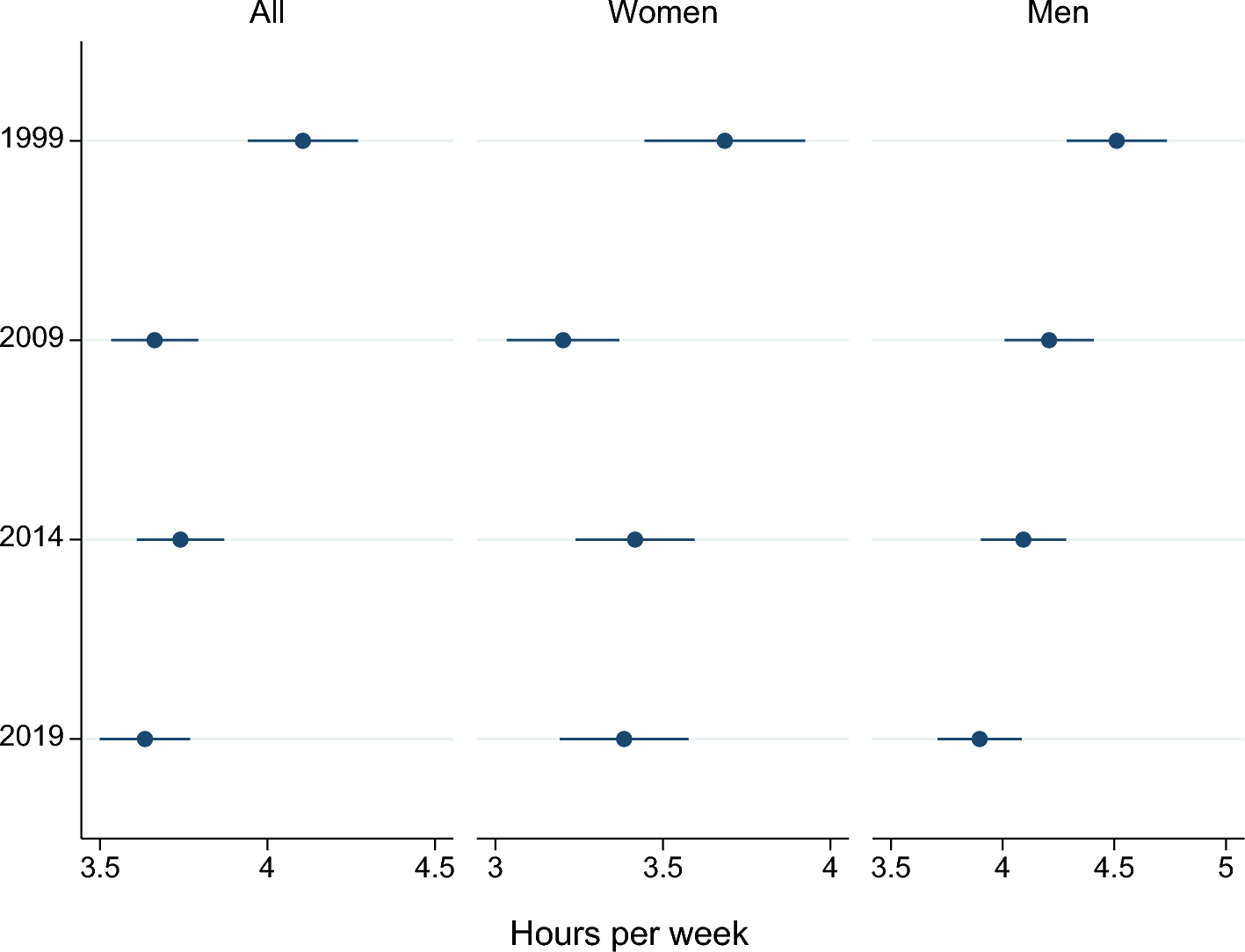

Fig. 1 Description of time contributions in weekly hours to voluntary activity in 1999, 2009, 2014 and 2019; predictive margins with 95%Cis.

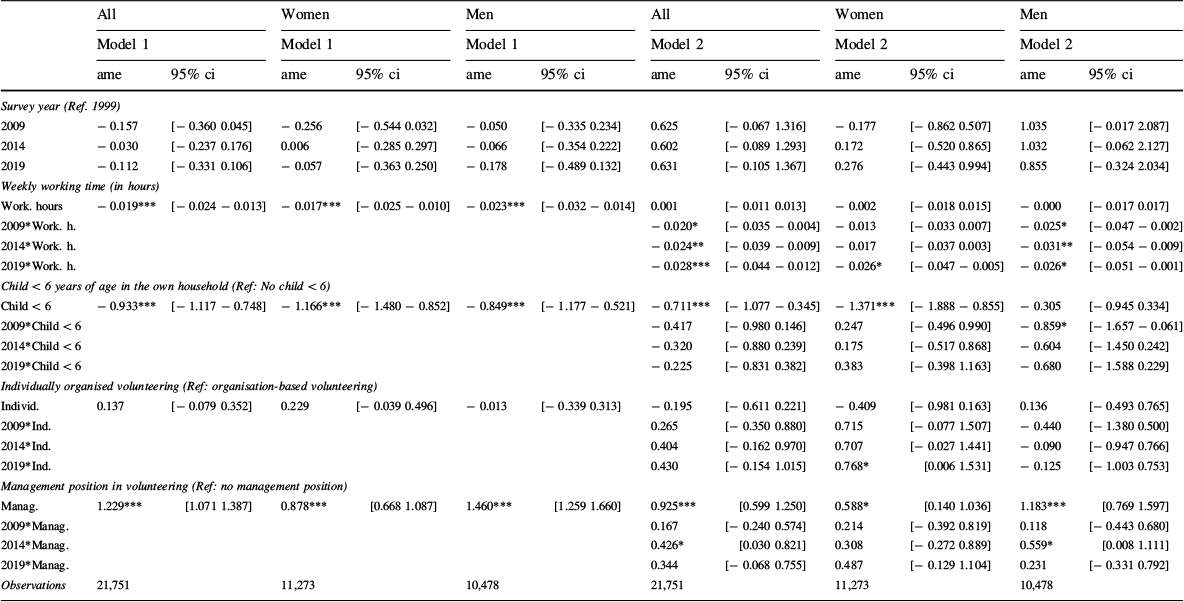

Table 1 Determinants of time spent in volunteering over historical time (Poisson, robust standard errors).

All |

Women |

Men |

All |

Women |

Men |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Model 1 |

Model 1 |

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 2 |

Model 2 |

|||||||

ame |

95% ci |

ame |

95% ci |

ame |

95% ci |

ame |

95% ci |

ame |

95% ci |

ame |

95% ci |

|

Survey year (Ref. 1999) |

||||||||||||

2009 |

− 0.157 |

[− 0.360 0.045] |

− 0.256 |

[− 0.544 0.032] |

− 0.050 |

[− 0.335 0.234] |

0.625 |

[− 0.067 1.316] |

− 0.177 |

[− 0.862 0.507] |

1.035 |

[− 0.017 2.087] |

2014 |

− 0.030 |

[− 0.237 0.176] |

0.006 |

[− 0.285 0.297] |

− 0.066 |

[− 0.354 0.222] |

0.602 |

[− 0.089 1.293] |

0.172 |

[− 0.520 0.865] |

1.032 |

[− 0.062 2.127] |

2019 |

− 0.112 |

[− 0.331 0.106] |

− 0.057 |

[− 0.363 0.250] |

− 0.178 |

[− 0.489 0.132] |

0.631 |

[− 0.105 1.367] |

0.276 |

[− 0.443 0.994] |

0.855 |

[− 0.324 2.034] |

Weekly working time (in hours) |

||||||||||||

Work. hours |

− 0.019*** |

[− 0.024 − 0.013] |

− 0.017*** |

[− 0.025 − 0.010] |

− 0.023*** |

[− 0.032 − 0.014] |

0.001 |

[− 0.011 0.013] |

− 0.002 |

[− 0.018 0.015] |

− 0.000 |

[− 0.017 0.017] |

2009*Work. h. |

− 0.020* |

[− 0.035 − 0.004] |

− 0.013 |

[− 0.033 0.007] |

− 0.025* |

[− 0.047 − 0.002] |

||||||

2014*Work. h. |

− 0.024** |

[− 0.039 − 0.009] |

− 0.017 |

[− 0.037 0.003] |

− 0.031** |

[− 0.054 − 0.009] |

||||||

2019*Work. h. |

− 0.028*** |

[− 0.044 − 0.012] |

− 0.026* |

[− 0.047 − 0.005] |

− 0.026* |

[− 0.051 − 0.001] |

||||||

Child < 6 years of age in the own household (Ref: No child < 6) |

||||||||||||

Child < 6 |

− 0.933*** |

[− 1.117 − 0.748] |

− 1.166*** |

[− 1.480 − 0.852] |

− 0.849*** |

[− 1.177 − 0.521] |

− 0.711*** |

[− 1.077 − 0.345] |

− 1.371*** |

[− 1.888 − 0.855] |

− 0.305 |

[− 0.945 0.334] |

2009*Child < 6 |

− 0.417 |

[− 0.980 0.146] |

0.247 |

[− 0.496 0.990] |

− 0.859* |

[− 1.657 − 0.061] |

||||||

2014*Child < 6 |

− 0.320 |

[− 0.880 0.239] |

0.175 |

[− 0.517 0.868] |

− 0.604 |

[− 1.450 0.242] |

||||||

2019*Child < 6 |

− 0.225 |

[− 0.831 0.382] |

0.383 |

[− 0.398 1.163] |

− 0.680 |

[− 1.588 0.229] |

||||||

Individually organised volunteering (Ref: organisation-based volunteering) |

||||||||||||

Individ. |

0.137 |

[− 0.079 0.352] |

0.229 |

[− 0.039 0.496] |

− 0.013 |

[− 0.339 0.313] |

− 0.195 |

[− 0.611 0.221] |

− 0.409 |

[− 0.981 0.163] |

0.136 |

[− 0.493 0.765] |

2009*Ind. |

0.265 |

[− 0.350 0.880] |

0.715 |

[− 0.077 1.507] |

− 0.440 |

[− 1.380 0.500] |

||||||

2014*Ind. |

0.404 |

[− 0.162 0.970] |

0.707 |

[− 0.027 1.441] |

− 0.090 |

[− 0.947 0.766] |

||||||

2019*Ind. |

0.430 |

[− 0.154 1.015] |

0.768* |

[0.006 1.531] |

− 0.125 |

[− 1.003 0.753] |

||||||

Management position in volunteering (Ref: no management position) |

||||||||||||

Manag. |

1.229*** |

[1.071 1.387] |

0.878*** |

[0.668 1.087] |

1.460*** |

[1.259 1.660] |

0.925*** |

[0.599 1.250] |

0.588* |

[0.140 1.036] |

1.183*** |

[0.769 1.597] |

2009*Manag. |

0.167 |

[− 0.240 0.574] |

0.214 |

[− 0.392 0.819] |

0.118 |

[− 0.443 0.680] |

||||||

2014*Manag. |

0.426* |

[0.030 0.821] |

0.308 |

[− 0.272 0.889] |

0.559* |

[0.008 1.111] |

||||||

2019*Manag. |

0.344 |

[− 0.068 0.755] |

0.487 |

[− 0.129 1.104] |

0.231 |

[− 0.331 0.792] |

||||||

Observations |

21,751 |

11,273 |

10,478 |

21,751 |

11,273 |

10,478 |

||||||

Models 2 are also controlled for age, age squared, region, level of education, presence of social support and spatial mobility. Models 2 for the whole sample are also controlled for gender and gender*wave. To consider persons with missing values on single explaining variables, we include categories with missing values in the analysis but do not interpret them substantively

+ p < 0.1, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

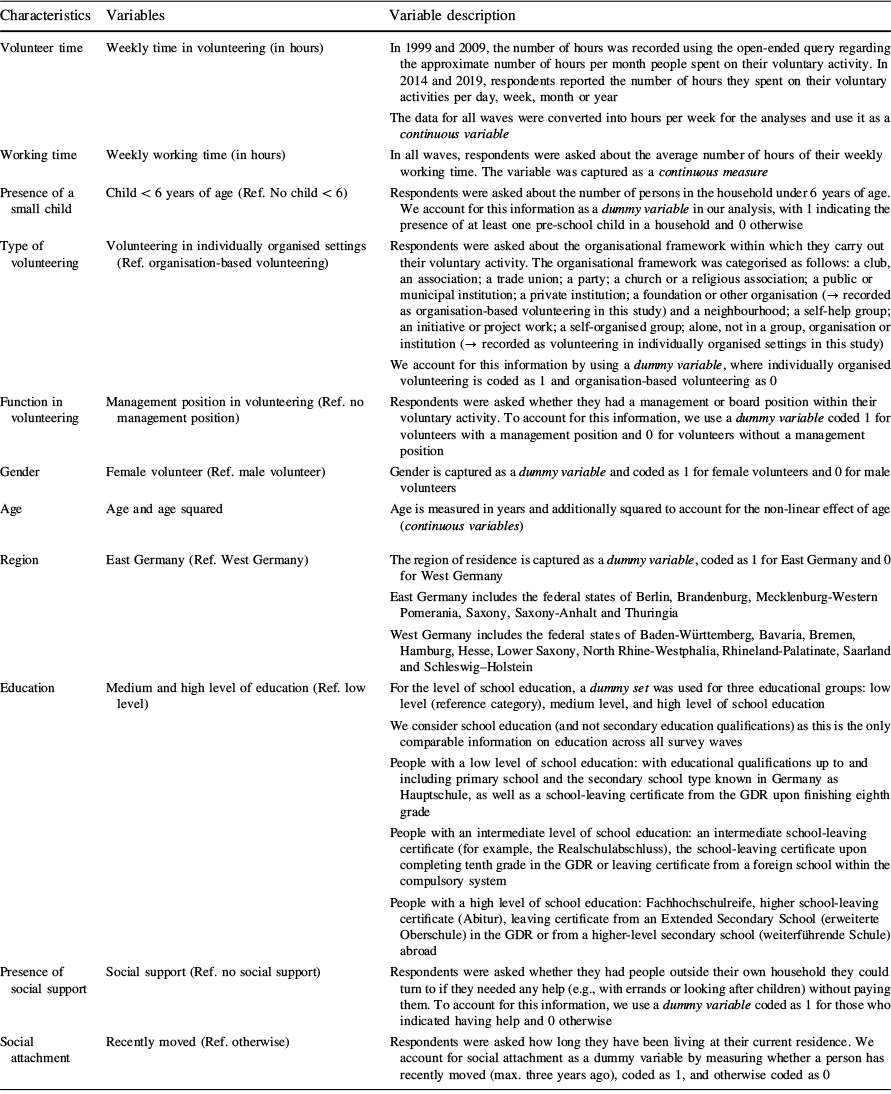

Variables

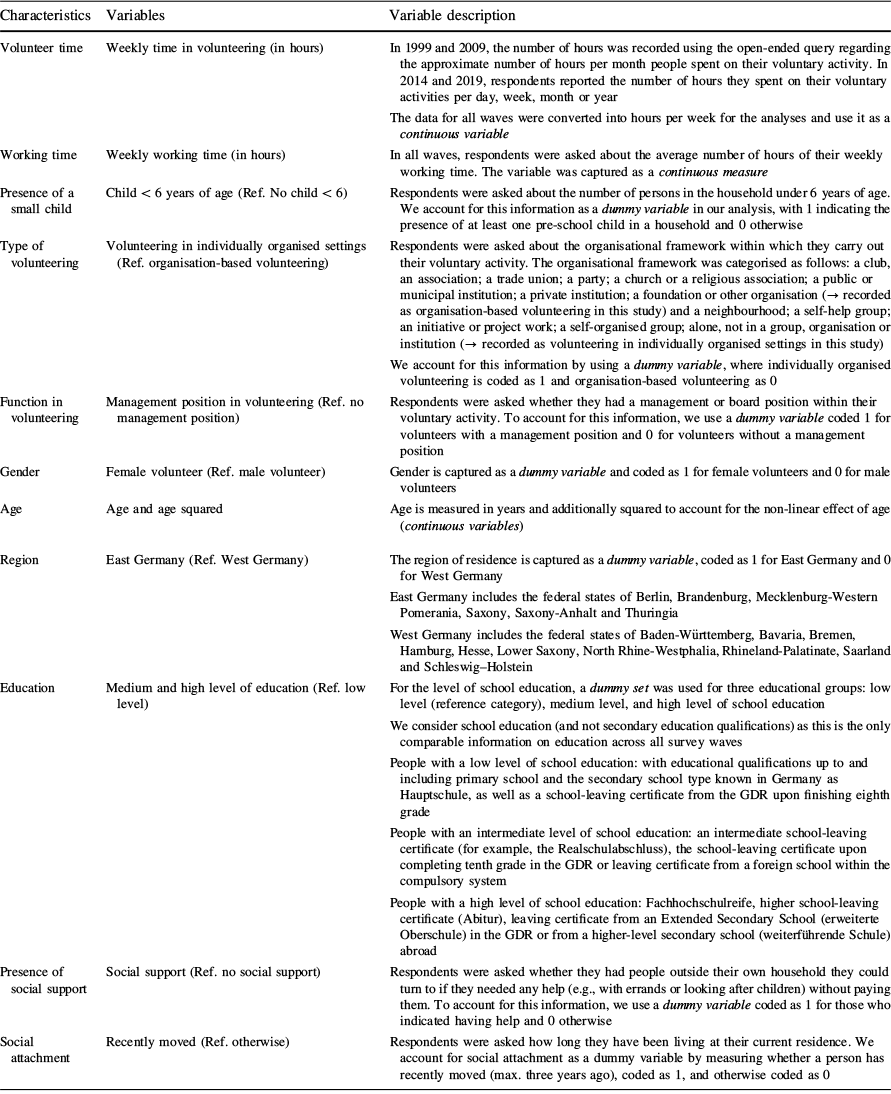

The dependent variable is the weekly time (in hours) spent on a voluntary activity. In each survey wave, respondents were asked whether they were actively involved in 14 different areas (e.g., sport and exercise, social or health area), and if the response was yes, they were asked whether they participated in voluntary activities in these areas. Respondents who indicated that they volunteered were asked about the number of hours they contributed to their most time-consuming voluntary activity. This and all further variables are described in detail in Table 2 in the appendix.

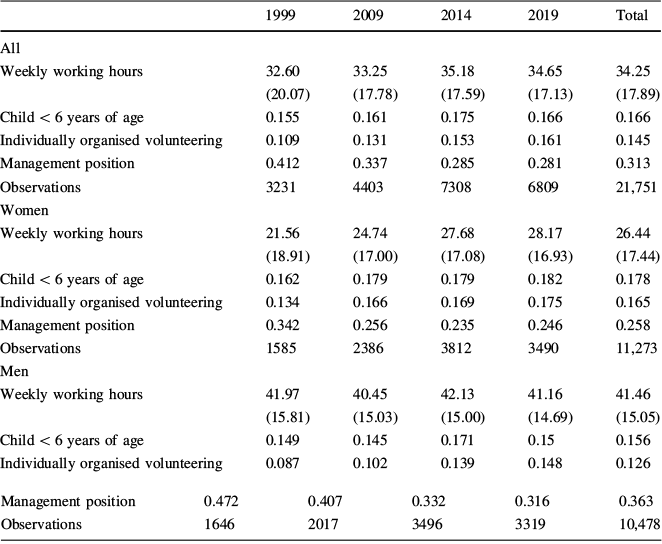

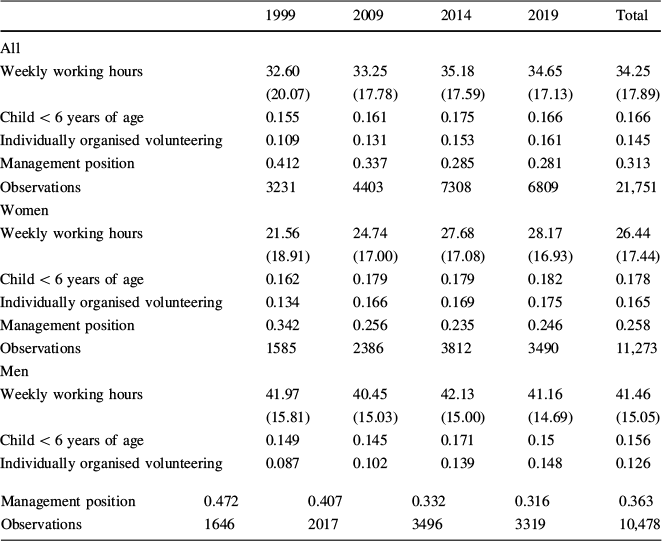

We include a number of covariates in the analyses. We measure the weekly time spent in paid work (in hours) as a continuous variable. Moreover, we consider the information on at least one pre-school child (under the age of 6) living in the household as a dummy variable. Furthermore, a dummy variable is included in the analyses to indicate whether a voluntary activity took place in an individually organised or organisation-based setting. Another dummy variable indicates whether this voluntary activity was carried out with or without holding a management position. In Table 3 in the appendix, the descriptive statistics of all covariates are presented by survey waves for the whole sample and by gender.

We consider additional (control) variables previously shown to influence volunteers’ time contributions (for more details on the operationalisation see Table 2 in the appendix). We consider age and age squared, adjusting for the known trend of high volunteer time contributions in mid- and early old age, decreasing afterwards (van Ingen & Dekker, Reference van Ingen and Dekker2010). Region of residence is adjusted for, recognising the historically different opportunity structures for volunteering in East and West Germany (Kausmann et al., Reference Kausmann, Burkhardt, Rump, Kelle, Simonson, Tesch-Römer and Krimmer2019). Education level is taken into account, with lower-educated individuals being less likely to volunteer; however, if they do volunteer, their volunteering tends to be even more time-intensive compared to those with intermediate or high education levels (van Ingen & Dekker, Reference van Ingen and Dekker2010; Kelle et al., Reference van Ingen and Dekker2022a). Social support is considered, as more social connections increase the likelihood of volunteering, but too many may limit time for voluntary activities (Taniguchi, Reference Taniguchi2012; van Ingen & Dekker, Reference van Ingen and Dekker2010). Spatial mobility is included, acknowledging that recent movers may have weaker connections, potentially investing fewer hours in voluntary activities (van Ingen & Dekker, Reference van Ingen and Dekker2010).

Analytical strategy

To predict volunteer time contributions, we run Poisson regressions with robust standard errors. We use Poisson regression models because the observations of the dependent variable “volunteer hours” are heavily skewed to the right: most volunteers contribute only a modest number of hours to their activity, while a small group of volunteers contribute many hours. This type of distribution is different from a normal distribution; the counts tend to cluster close to the lower real limit of zero, leading to a high positive skew, a mean that is significantly bigger than the median, and a variance that is disproportionally larger than the mean (Beck & Tolnay, Reference Beck and Tolnay1995). Therefore, we use maximum likelihood prediction techniques for the estimation of our models, with a modified Poisson distribution in the error term. To relax the assumption of the model that variance equals mean, we use a Huber/White/sandwich estimator when specifying the variance–covariance matrix of the estimates (for more information on the method, see Gould, (Reference Gould2011). For our estimations, we use Stata 17.

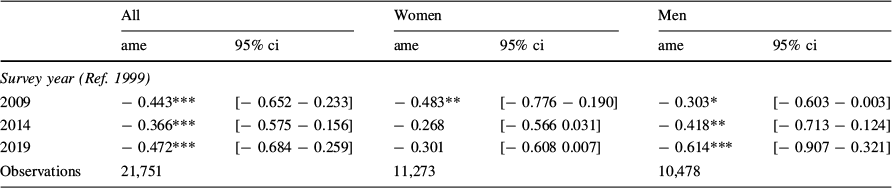

In the first step, we run Poisson regressions that only include the survey year, so we can test whether there is an overall decrease in the time efforts people put into their voluntary activities over time to test H1 (see Fig. 1 and Table 4 in the appendix). In the second step, we run models (Table 1, Models 1) that include all covariates as well as control variables, and also models (Table 1, Models 2) that additionally include interaction terms between covariates and waves (1999, 2009, 2014 and 2019), so we can test H2–H4 on whether and how the influence of the key determinants and correlates on volunteer time contributions has changed over time. When presenting the regression results, we report average marginal effects (AME), giving the average predicted change in weekly hours spent on voluntary activities, with the corresponding independent variable changed by one unit and all other variables held constant. The regression allows us to discuss the effects in a statistical sense. However, since our results were derived from cross-sectional data, we cannot identify effects in the strict sense of causality. We additionally present information on confidence intervals (CI) and statistical significance.

Results

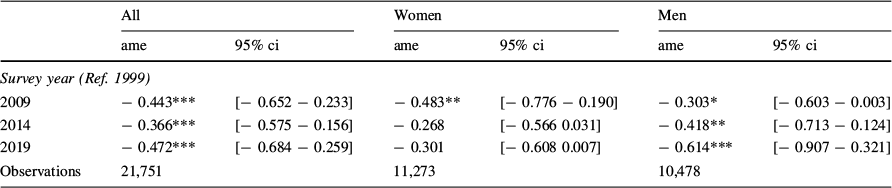

Figure 1 provides information about the time contributions to voluntary activity in 1999, 2009, 2014, and 2019, presenting predictive margins with 95% confidence intervals. This figure was retrieved from the Poisson regression detailed in Table 4 in the appendix, including only the survey year indicator. For the whole sample, it is evident that in 1999, volunteers tended to contribute over 4 h per week, dedicating more time to their voluntary activity than in the subsequent years. In 2009, 2014, and 2019, volunteer time contribution decreased to about 3.5 h per week, indicating a consistent pattern for these years.

The trends in volunteer time contribution show differences between men and women. Specifically, for women, a significant difference is noticeable only between 1999 and 2009. While female volunteers tended to contribute over 3.5 h to their voluntary activity in 1999, by 2009, time contributions had decreased to about 3 h per week. However, time contributions in 2014 and 2019 did not significantly differ from those in 1999, suggesting that there was only a temporary decrease in 2009. For male volunteers, there seems to be a gradual trend towards lower time contributions, decreasing from 4.5 to under 4 h per week over the observed time span. However, also for men, only the difference between 1999 and the subsequent years is statistically significant, not between 2009, 2014, and 2019.

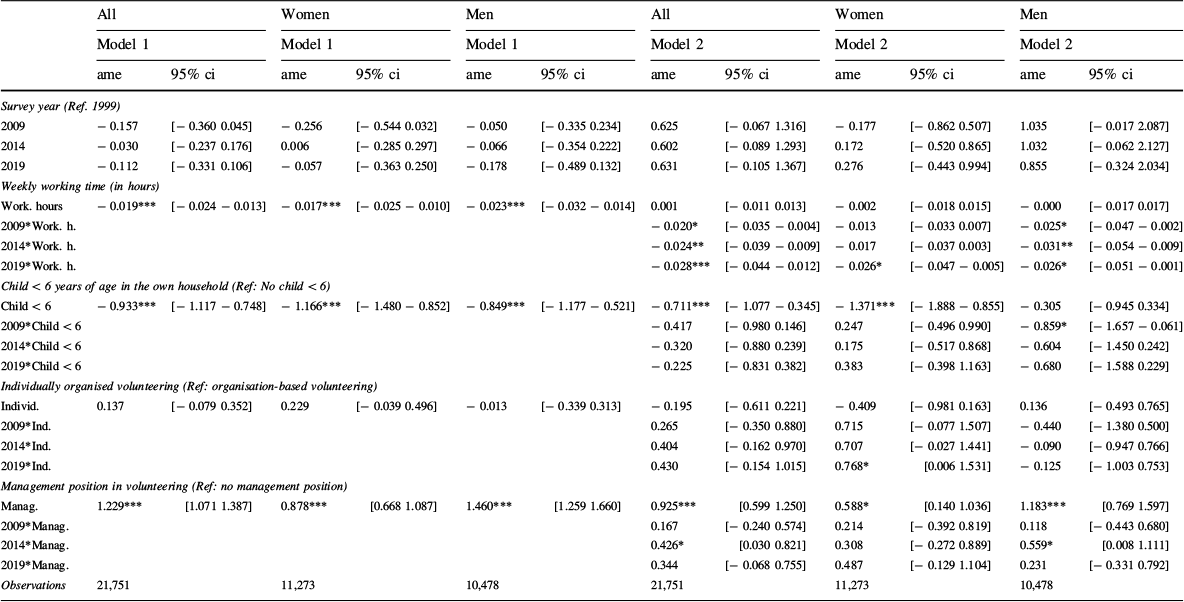

Table 1 shows regression results for men and women together (Model 1, All), and also separately for men and women. Model 1 is adjusted for the covariates weekly working time, presence of a pre-school child in the household, volunteering in an individually organised settings and holding a volunteer management position, along with control variables. In this model, there are no statistically significant differences in volunteer time contribution across the years. This indicates that the considered determinants and covariates are significant factors in explaining the differences observed in Fig. 1.

In the comprehensive analyses encompassing both men and women, we observe that longer working hours (AME: − 0.019; 95%CI: [− 0.024 − 0.013]) and having a pre-school child in the household (AME: − 0.933; 95%CI: [− 1.117 − 0.748]) are negatively associated with volunteer weekly hours (see Model 1). Furthermore, holding a management position is linked to higher time contributions to voluntary activity (AME: 1.229; 95%CI: [1.071 1.387]), while there is no statistically significant difference in terms of whether volunteers engage in individually organised or organisation-based settings. These patterns persist in the analyses conducted separately for men and women (Model 1, Women, Men). Seemingly unrelated estimations were applied to compare the sizes of the average marginal effects between men and women (results not shown here, but discussed in the text). While no gender-specific difference was found in how weekly working hours are associated with volunteer hours (women: AME: − 0.017; 95%CI: [− 0.025 − 0.010]; men: AME: − 0.023; 95%CI: [− 0.032 − 0.014]), there are statistically significant differences in how the presence of a pre-school child in the household and holding a management position are liked to volunteer time contributions. Having a pre-school child is more negatively associated with volunteer hours for women than for men (women: AME: − 1.166; 95%CI: [− 1.480 − 0.852]; men: AME: − 0.849; 95%CI: [− 1.177 − 0.521]). Conversely, holding a management position is liked to higher time contributions to voluntary activity for men than for women (women: AME: 0.878; 95%CI: [0.668 1.087]; men: AME: 1.460; 95%CI: [1.259 1.660]).

Model 2 additionally incorporates interaction terms between the covariates and the survey waves, enabling us to explore the associations at baseline in 1999 (main effects) and how they evolved over time (interaction terms). In the combined sample, the link between working time and volunteer hours is initially not statistically significant (AME: − 0.001; 95%CI: [-0.011 0.013]), but tends to become more negative over time. However, the AME in 2009 (AME: − 0.020; 95%CI: [− 0.035 0.004]), 2014 (AME: − 0.024; 95%CI: [− 0.039 − 0.009]), and 2019 (AME: − 0.028; 95%CI: [− 0.044 − 0.012]) are not statistically different from each other. While a similar pattern is observed for men, women only show a negative association between working and volunteer hours in 2019 compared to 1999. The effect sizes related to working time are comparable between men and women. Moreover, the presence of pre-school children in the household is initially associated with a negative impact on volunteer hours in the combined sample (AME: − 0.711; 95%CI: [− 1.077 − 0.345]) and also specifically for women (AME: − 1.371; 95%CI: [− 1.888 − 0.855]). However, this negative association remained stable over the years. For men, there is no initial negative association between having a pre-school child and volunteer hours (AME: − 0.305; 95%CI: [− 0.945 0.334]). However, there is a negative association in 2009 (AME: − 0.859; 95%CI: [− 1.657 − 0.061]), with no consistent trend detected in the following years. The negative association between having a pre-school child and volunteer hours is more pronounced for women than for men at baseline. However, the negative association in 2009 for men is also statistically different from that of women.

Moreover, in the overall model, we do not observe a link between the form of volunteering (individually organised vs. organisation-based) and volunteer hours across any time point. While this finding holds for male volunteers, female volunteers show a positive association between engagement in individually organised settings and volunteer hours only in 2019 (AME: 0.768; 95%CI: [0.006 1.531]), but not in any of the previous years. Furthermore, in the overall sample (AME: 0.925; 95%CI: [0.599 1.250]) as well as for men and women separately there is initially a positive association between holding a management position and volunteer hours and this difference is statistically significant between men and women (women: AME: 0.588; 95%CI: [0.140 1.036]; men: AME: 1.183; 95%CI: [0.769 1.597]). For women, this positive correlation remains consistent over time. However, for men, there appears to be an increase in volunteer hours among those in management positions in 2014 compared to 1999 (AME: 0.559; 95%CI: [0.008 1.111]); however, this association is not present in 2019 Table 1.

Summary and Discussion

This study examined changes in voluntary time contributions over time and in gender comparison. Analysing data from the German Survey on Volunteering from 1999 to 2019, we explored the associations between volunteer hours and work-family life changes and changing voluntary behaviour for working-age volunteers.

Our findings suggest a decrease in volunteer hours over time, cautioning that the decline is mainly between 1999 and 2009. Hence, H1 is only partially accepted. At the first glance, somewhat distinct patterns emerge for men and women, with women showing no consistent decline and men seemingly exhibiting a decreasing average in volunteer hours with each survey year. However, the decline in volunteer hours by men is also only statistically significant between 1999 and 2009 and not thereafter. Future research will show whether men's volunteer hours will exhibit further declines over time or whether changes will occur in response to societal factors, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. The striking finding of a decrease in volunteer time contributions only between 1999 and 2009, and not thereafter, could be attributed to the challenging labour market conditions in Germany during the 2000s. In 2005, the country experienced a high unemployment rate of 13 percent, which gradually declined thereafter (Bundesagentur für Arbeit & Statistik, 2024). In Germany, unemployment has been significantly associated with reduced investments in voluntary activities (Strauss, Reference Strauss2008). Additionally, there may have been an impact of the financial crisis in 2008 on volunteer time investments. Although no study directly addresses this, evidence suggests that unemployment levels did not rise due to the crisis in Germany, and both employment and volunteer levels did not experience a decline (Bosch, Reference Bosch2011).

To better understand trends in volunteer time contributions, we explored the connection between changes in work-family life and evolving individual voluntary behaviour with volunteer hours. Considering these factors eliminated the negative trend towards fewer volunteer hours observed in the bivariate analyses, signifying their significance in explaining changes in volunteer time contributions. However, it is crucial to acknowledge that there are other important factors related to volunteer time contributions, such as family caregiving or leisure time, which we could not include in the analysis due to data limitations. A recent study in Germany found that time investments in volunteering compete more with work-family conflict than with other activities like relaxing, sports, or meeting friends (Wallrodt & Thieme, Reference Wallrodt and Thieme2023). The authors attribute this to the complementary nature of these activities, suggesting that leisure activities can often be integrated into voluntary activities, such as sports-related volunteering. Similarly, another study, focusing on women, indicated that volunteering did not appear to compete with leisure activities like socialising or media usage (Burkhardt et al., Reference Burkhardt, Priller, Zimmer and Bundesamt2017).

Examining work-family life factors, the association between longer working hours and shorter volunteer hours was found supporting H2a and indicating that individuals facing high demands on their time may experience constraints on their voluntary activities, consistent with the role-overload theory. The association between working and volunteer hours emerged over time not only for men but also for women, as expected with the significant increase in female employment since the 1990s (Wanger, Reference Wanger, Möller and Walwei2017). However, contrary to the expectation specified in H2b, the intensification of this association did not differ significantly between women and men over time. The examination of the relationship between having a pre-school child at home and volunteer hours led to the rejection of H3a, as this association did not consistently change over time. While women consistently exhibited a negative association between having a pre-school child and volunteer hours, the tendency for a negative association over the years was inconsistent for men, leading to the rejection of H3b. These findings indicate that the negative impact of having a pre-school child on volunteer hours was more consistent for women than for men over time. However, the finding that not only women but also men with small children have experienced negative consequences for volunteer hours over time calls for more studies examining how this association unfolds in the future.

Contrary to the expectations derived from the theoretical perspective proposed by Hustinx & Lammertyn, (Reference Hustinx and Lammertyn2003), which suggests that the shift from the 'collective' to the 'reflective' style of volunteering might be linked to a less committal and time-intensive nature of volunteering, we did not find any evidence that individually organised and less hierarchical volunteering is increasingly negatively linked to volunteer hours. Additionally, there is no consistent evidence that volunteer managers compensate for the overall decline in volunteer time by increasing their contributions. Thus, we reject the notion that volunteers' diminishing organisational attachment is increasingly negatively associated with time contributions, leading to the rejection of H4a. Additionally, we reject H4b, suggesting that weakening organisational attachment is more noticeable for women than for men, as women even exhibited higher time investments in volunteering in individually organised settings over time. The findings of our study align with the notion that new, less formal volunteering would replace traditional forms without reducing volunteer time (e.g., Wuthnow, Reference Wuthnow1998). However, they contradict Qvist et al. (Reference Qvist, Henriksen and Fridberg2018) study, which proposed that diminishing organisational attachment can indeed negatively impact time contributions. The discrepancy may arise from using different measures; we focus on the institutional setting of volunteering (organisation-based volunteering vs. volunteering in individually organised settings), while Qvist et al., (Reference Qvist, Henriksen and Fridberg2018) use “member-based” and “non-member-based” volunteering. Furthermore, the results may reflect nation-specific differences, as the analyses of Qvist et al., (Reference Qvist, Henriksen and Fridberg2018) are based on data for Denmark, while our analyses are for the German context. If this is the case, it is interesting to note that while both studies identify a similar trend toward a weakening organisational attachment, the consequences for volunteer time contributions are different. Further insights into these dynamics would benefit from additional cross-national studies, delving into country-specific distinctions.

Our study contributes to the literature by providing a dynamic view of worktime and family and voluntary behaviour characteristics on volunteer hours over 20 years. We use the only dataset available for the German context that is suitable for these analyses. However, our analyses are subject to some limitations. The most important is the cross-sectional design, which cannot sufficiently account for unobserved heterogeneity and does not allow for the establishment of causal links between the observed characteristics and volunteer time contributions. Furthermore, the data has not always been comparably gathered over the survey years. This has led to limitations such as missing information on volunteer hours in 2004 or missing consideration of factors such as family caregiving or marital status that might influence individual voluntary commitment. Moreover, as our research interest is in the shifts in volunteers' time contributions, we focused on the sample of volunteers. However, the decision to volunteer, including committing to a specific number of hours, involves a two-step process: deciding to volunteer and determining time contributions. This introduces a potential limitation to our analysis, as changes in the second step may be contingent on shifts in the composition of the first step. Notably, existing literature highlights persistent patterns in the composition of volunteering in Germany, marked by enduring social closure and inequalities over time (Simonson et al.,Reference Strauss2022b ; Strauss, Reference Strauss2008).

Conclusion

As volunteer time contributions become more intertwined with work-family conflict over time, it becomes increasingly vital for organisations to focus on ensuring compatibility between work and family responsibilities and volunteering. By addressing work-family conflict, organisations can effectively reduce the opportunity costs and barriers for volunteers. Embracing an even more inclusive approach, encompassing groups currently underrepresented in volunteering, may further encourage voluntary time investments.

The ongoing transition from organisation-based to more individually organised volunteering does not appear to be linked to reduced volunteer time contributions; in fact, it may present new opportunities. Organisations could explore concepts commonly used in individually organised voluntary settings, such as project-based, short-term, and shared managerial positions. This is particularly important due to the increasing difficulty of balancing extended work hours with time-demanding volunteer activities and has the potential to attract diverse groups who are currently not involved in volunteering, fostering gender equality within the voluntary sector.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. The paper is based on survey study funded by the Federal Ministry for Family Affairs, Senior Citizens, Women and Youth under Grant Agreement N.3917405FWS.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

Authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Human or Animal Consent

The accompanying manuscript does not include studies on humans or animals.

Appendix

See Appendix Tables 2, 3 and 4.

Table 2 Description and operationalisation of variables

Characteristics |

Variables |

Variable description |

|---|---|---|

Volunteer time |

Weekly time in volunteering (in hours) |

In 1999 and 2009, the number of hours was recorded using the open-ended query regarding the approximate number of hours per month people spent on their voluntary activity. In 2014 and 2019, respondents reported the number of hours they spent on their voluntary activities per day, week, month or year |

The data for all waves were converted into hours per week for the analyses and use it as a continuous variable |

||

Working time |

Weekly working time (in hours) |

In all waves, respondents were asked about the average number of hours of their weekly working time. The variable was captured as a continuous measure |

Presence of a small child |

Child < 6 years of age (Ref. No child < 6) |

Respondents were asked about the number of persons in the household under 6 years of age. We account for this information as a dummy variable in our analysis, with 1 indicating the presence of at least one pre-school child in a household and 0 otherwise |

Type of volunteering |

Volunteering in individually organised settings (Ref. organisation-based volunteering) |

Respondents were asked about the organisational framework within which they carry out their voluntary activity. The organisational framework was categorised as follows: a club, an association; a trade union; a party; a church or a religious association; a public or municipal institution; a private institution; a foundation or other organisation (→ recorded as organisation-based volunteering in this study) and a neighbourhood; a self-help group; an initiative or project work; a self-organised group; alone, not in a group, organisation or institution (→ recorded as volunteering in individually organised settings in this study) |

We account for this information by using a dummy variable, where individually organised volunteering is coded as 1 and organisation-based volunteering as 0 |

||

Function in volunteering |

Management position in volunteering (Ref. no management position) |

Respondents were asked whether they had a management or board position within their voluntary activity. To account for this information, we use a dummy variable coded 1 for volunteers with a management position and 0 for volunteers without a management position |

Gender |

Female volunteer (Ref. male volunteer) |

Gender is captured as a dummy variable and coded as 1 for female volunteers and 0 for male volunteers |

Age |

Age and age squared |

Age is measured in years and additionally squared to account for the non-linear effect of age (continuous variables) |

Region |

East Germany (Ref. West Germany) |

The region of residence is captured as a dummy variable, coded as 1 for East Germany and 0 for West Germany |

East Germany includes the federal states of Berlin, Brandenburg, Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt and Thuringia |

||

West Germany includes the federal states of Baden-Württemberg, Bavaria, Bremen, Hamburg, Hesse, Lower Saxony, North Rhine-Westphalia, Rhineland-Palatinate, Saarland and Schleswig–Holstein |

||

Education |

Medium and high level of education (Ref. low level) |

For the level of school education, a dummy set was used for three educational groups: low level (reference category), medium level, and high level of school education |

We consider school education (and not secondary education qualifications) as this is the only comparable information on education across all survey waves |

||

People with a low level of school education: with educational qualifications up to and including primary school and the secondary school type known in Germany as Hauptschule, as well as a school-leaving certificate from the GDR upon finishing eighth grade |

||

People with an intermediate level of school education: an intermediate school-leaving certificate (for example, the Realschulabschluss), the school-leaving certificate upon completing tenth grade in the GDR or leaving certificate from a foreign school within the compulsory system |

||

People with a high level of school education: Fachhochschulreife, higher school-leaving certificate (Abitur), leaving certificate from an Extended Secondary School (erweiterte Oberschule) in the GDR or from a higher-level secondary school (weiterführende Schule) abroad |

||

Presence of social support |

Social support (Ref. no social support) |

Respondents were asked whether they had people outside their own household they could turn to if they needed any help (e.g., with errands or looking after children) without paying them. To account for this information, we use a dummy variable coded as 1 for those who indicated having help and 0 otherwise |

Social attachment |

Recently moved (Ref. otherwise) |

Respondents were asked how long they have been living at their current residence. We account for social attachment as a dummy variable by measuring whether a person has recently moved (max. three years ago), coded as 1, and otherwise coded as 0 |

Table 3 Descriptive statistics of independent and control variables by survey waves for the whole sample and by gender, in hours (standard deviations in parentheses)/proportions.

1999 |

2009 |

2014 |

2019 |

Total |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

All |

|||||

Weekly working hours |

32.60 |

33.25 |

35.18 |

34.65 |

34.25 |

(20.07) |

(17.78) |

(17.59) |

(17.13) |

(17.89) |

|

Child < 6 years of age |

0.155 |

0.161 |

0.175 |

0.166 |

0.166 |

Individually organised volunteering |

0.109 |

0.131 |

0.153 |

0.161 |

0.145 |

Management position |

0.412 |

0.337 |

0.285 |

0.281 |

0.313 |

Observations |

3231 |

4403 |

7308 |

6809 |

21,751 |

Women |

|||||

Weekly working hours |

21.56 |

24.74 |

27.68 |

28.17 |

26.44 |

(18.91) |

(17.00) |

(17.08) |

(16.93) |

(17.44) |

|

Child < 6 years of age |

0.162 |

0.179 |

0.179 |

0.182 |

0.178 |

Individually organised volunteering |

0.134 |

0.166 |

0.169 |

0.175 |

0.165 |

Management position |

0.342 |

0.256 |

0.235 |

0.246 |

0.258 |

Observations |

1585 |

2386 |

3812 |

3490 |

11,273 |

Men |

|||||

Weekly working hours |

41.97 |

40.45 |

42.13 |

41.16 |

41.46 |

(15.81) |

(15.03) |

(15.00) |

(14.69) |

(15.05) |

|

Child < 6 years of age |

0.149 |

0.145 |

0.171 |

0.15 |

0.156 |

Individually organised volunteering |

0.087 |

0.102 |

0.139 |

0.148 |

0.126 |

Management position |

0.472 |

0.407 |

0.332 |

0.316 |

0.363 |

Observations |

1646 |

2017 |

3496 |

3319 |

10,478 |

Some variables contain missing values. Weekly working time: 0.83 percent; child < 6 years of age: 0.26 percent; individually organised volunteering: 1.33 percent; management position: 0.86 percent

Table 4 Determinants of time spent in volunteering over historical time, basic models (Poisson, robust errors).

All |

Women |

Men |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

ame |

95% ci |

ame |

95% ci |

ame |

95% ci |

|

Survey year (Ref. 1999) |

||||||

2009 |

− 0.443*** |

[− 0.652 − 0.233] |

− 0.483** |

[− 0.776 − 0.190] |

− 0.303* |

[− 0.603 − 0.003] |

2014 |

− 0.366*** |

[− 0.575 − 0.156] |

− 0.268 |

[− 0.566 0.031] |

− 0.418** |

[− 0.713 − 0.124] |

2019 |

− 0.472*** |

[− 0.684 − 0.259] |

− 0.301 |

[− 0.608 0.007] |

− 0.614*** |

[− 0.907 − 0.321] |

Observations |

21,751 |

11,273 |

10,478 |

|||

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001