1 Introduction

First passage percolation (FPP) is a natural way to understand geodesics in random metric spaces. Starting from some initial vertex at time

![]() $0$

, the process spreads through the underlying graph so that the transmission time between any two vertices

$0$

, the process spreads through the underlying graph so that the transmission time between any two vertices

![]() $x,y$

is the minimum sum of edge transmission times over all paths between x and y. In classical FPP, edge transmission times are independent and identically distributed random variables. In the recent paper [Reference Komjáthy, Lapinskas and Lengler55] we introduced one-dependent FPP, where edge transmission times depend on the edge’s direct surroundings in the underlying graph. There, we determined the phase transition for explosion (i.e., reaching infinitely many vertices in finite time). In this paper we study the sub-explosive regime, when explosion does not occur. We show that the process exhibits rich behaviour with several growth phases and nonsmooth phase transitions between them. This holds across a large class of scale-free spatial random graph models (namely Scale-Free Percolation (SFP), Hyperbolic Random Graphs (HypRG), and infinite and finite Geometric Inhomogeneous Random Graphs (GIRG) [Reference Deijfen, van der Hofstad and Hooghiemstra26, Reference Bringmann, Keusch and Lengler17, Reference Krioukov, Papadopoulos, Kitsak, Vahdat and Boguná58]), and across all Markovian and non-Markovian transmission time distributions with reasonable limiting behaviour at zero.

$x,y$

is the minimum sum of edge transmission times over all paths between x and y. In classical FPP, edge transmission times are independent and identically distributed random variables. In the recent paper [Reference Komjáthy, Lapinskas and Lengler55] we introduced one-dependent FPP, where edge transmission times depend on the edge’s direct surroundings in the underlying graph. There, we determined the phase transition for explosion (i.e., reaching infinitely many vertices in finite time). In this paper we study the sub-explosive regime, when explosion does not occur. We show that the process exhibits rich behaviour with several growth phases and nonsmooth phase transitions between them. This holds across a large class of scale-free spatial random graph models (namely Scale-Free Percolation (SFP), Hyperbolic Random Graphs (HypRG), and infinite and finite Geometric Inhomogeneous Random Graphs (GIRG) [Reference Deijfen, van der Hofstad and Hooghiemstra26, Reference Bringmann, Keusch and Lengler17, Reference Krioukov, Papadopoulos, Kitsak, Vahdat and Boguná58]), and across all Markovian and non-Markovian transmission time distributions with reasonable limiting behaviour at zero.

In SFP, the vertex set is formed by the d-dimensional lattice

![]() $\mathbb {Z}^d$

. Each vertex u is then equipped with an independent and identically distributed random vertex-weight

$\mathbb {Z}^d$

. Each vertex u is then equipped with an independent and identically distributed random vertex-weight

![]() $W_u\ge 1$

. Given the weighted vertex set, the edges are drawn conditionally independently. The probability of an edge between vertices

$W_u\ge 1$

. Given the weighted vertex set, the edges are drawn conditionally independently. The probability of an edge between vertices

![]() $u, v$

with weights

$u, v$

with weights

![]() $W_u, W_v$

decreases with the Euclidean distance

$W_u, W_v$

decreases with the Euclidean distance

![]() $|u-v|$

and increases with the vertex-weights, and is between constant factors of

$|u-v|$

and increases with the vertex-weights, and is between constant factors of

![]() $\min (1, W_u W_v/|u-v|^d)^\alpha $

, see Definition 1.3 below for full detail. The parameter

$\min (1, W_u W_v/|u-v|^d)^\alpha $

, see Definition 1.3 below for full detail. The parameter

![]() $\alpha $

is often called the long-range parameter, since the model with all vertex-weights set to

$\alpha $

is often called the long-range parameter, since the model with all vertex-weights set to

![]() $1$

recovers the classical long-range percolation model [Reference Schulman72]. Instead of unit vertex-weights, here we shall rather assume that the vertex-weight distribution W follows a regularly varying tail, that is, for some

$1$

recovers the classical long-range percolation model [Reference Schulman72]. Instead of unit vertex-weights, here we shall rather assume that the vertex-weight distribution W follows a regularly varying tail, that is, for some

![]() $\tau \in (2,3)$

that is called the power-law exponent we assume

$\tau \in (2,3)$

that is called the power-law exponent we assume

The heavy-tailed decay of W creates degree-inhomogeneity in the model: the vertex weight

![]() $W_v$

of v is (up to constant factors) equal to the expected degree of v, and the degree of a high-weight vertex is concentrated around its expectation [Reference Deijfen, van der Hofstad and Hooghiemstra26, Proposition 2.3]. The parameters

$W_v$

of v is (up to constant factors) equal to the expected degree of v, and the degree of a high-weight vertex is concentrated around its expectation [Reference Deijfen, van der Hofstad and Hooghiemstra26, Proposition 2.3]. The parameters

![]() $\tau , \alpha $

play different roles in governing inhomogeneities in the models: while

$\tau , \alpha $

play different roles in governing inhomogeneities in the models: while

![]() $\tau $

governs the degree distribution, a smaller

$\tau $

governs the degree distribution, a smaller

![]() $\alpha $

causes a heavier tail on the edge-length distribution, with

$\alpha $

causes a heavier tail on the edge-length distribution, with

![]() $\alpha>1$

needed for a.s. finite degrees [Reference Deijfen, van der Hofstad and Hooghiemstra26]. The model GIRG follows the same construction by replacing the location of vertices by a unit-intensity Poisson point process (PPP) on

$\alpha>1$

needed for a.s. finite degrees [Reference Deijfen, van der Hofstad and Hooghiemstra26]. The model GIRG follows the same construction by replacing the location of vertices by a unit-intensity Poisson point process (PPP) on

![]() $\mathbb {R}^d$

. For the overview of the results, the reader may ignore this difference.

$\mathbb {R}^d$

. For the overview of the results, the reader may ignore this difference.

Universality classes of transmission times. In one-dependent first passage percolation, we set the transmission time through the edge

![]() $e=xy$

between vertices

$e=xy$

between vertices

![]() $x,y$

as the product of an independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) random factor

$x,y$

as the product of an independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) random factor

![]() $L_{xy}$

and a factor depending on the weights of vertices:

$L_{xy}$

and a factor depending on the weights of vertices:

Definition 1.1 (1-dependent first passage percolation (1-FPP)).

Consider a graph

![]() $G = (\mathcal {V}, \mathcal {E})$

where each vertex

$G = (\mathcal {V}, \mathcal {E})$

where each vertex

![]() $v\in \mathcal {V}$

has an associated vertex-weight

$v\in \mathcal {V}$

has an associated vertex-weight

![]() $W_v$

. For every edge

$W_v$

. For every edge

![]() $xy\in \mathcal {E}$

, draw an i.i.d. copy

$xy\in \mathcal {E}$

, draw an i.i.d. copy

![]() $L_{xy}$

of a random variable L, and set the (transmission) cost of an edge

$L_{xy}$

of a random variable L, and set the (transmission) cost of an edge

![]() $xy$

as

$xy$

as

for a fixed parameter

![]() $\mu>0$

called the penalty strength. The costs define a cost distance

$\mu>0$

called the penalty strength. The costs define a cost distance

![]() $d_{\mathcal {C}}(x,y)$

between any two vertices x and y, which is the minimal total cost of any path between x and y (see Section 1.4.1). We call

$d_{\mathcal {C}}(x,y)$

between any two vertices x and y, which is the minimal total cost of any path between x and y (see Section 1.4.1). We call

![]() $d_{\mathcal {C}}$

the 1-dependent first passage percolation.

$d_{\mathcal {C}}$

the 1-dependent first passage percolation.

We usually assume that the cumulative distribution function (cdf)

![]() $F_L:[0,\infty )\rightarrow [0,1]$

of L satisfies the following assumption (with exceptions of this assumption explicitly mentioned):

$F_L:[0,\infty )\rightarrow [0,1]$

of L satisfies the following assumption (with exceptions of this assumption explicitly mentioned):

Assumption 1.2. There exist constants

![]() $t_0,\,c_1,\,c_2,\,\beta>0$

such that

$t_0,\,c_1,\,c_2,\,\beta>0$

such that

Without much effort, one can relax Assumption 1.2 to

![]() $\lim _{x\to 0} \log F_L(x)/\log x=\beta $

, that is, regularly varying behaviour of

$\lim _{x\to 0} \log F_L(x)/\log x=\beta $

, that is, regularly varying behaviour of

![]() $F_L$

near

$F_L$

near

![]() $0$

. We work with (1.3) for the sake of readability. Table 1 provides an overview of the various parameters of the model.

$0$

. We work with (1.3) for the sake of readability. Table 1 provides an overview of the various parameters of the model.

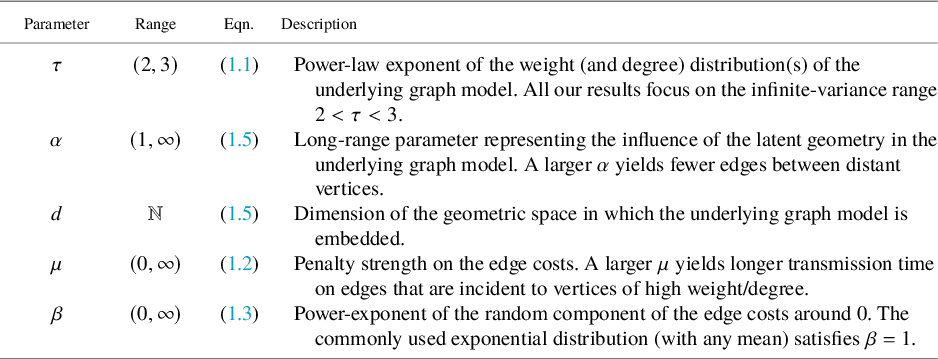

Table 1 Summary and brief description of the main parameters of the model.

The cost distance

![]() $d_{\mathcal {C}}(x,y)$

corresponds to the transmission time between two vertices

$d_{\mathcal {C}}(x,y)$

corresponds to the transmission time between two vertices

![]() $x,y$

. In SFP, we use the same vertex weights

$x,y$

. In SFP, we use the same vertex weights

![]() $W_x,W_y$

to generate the edge between

$W_x,W_y$

to generate the edge between

![]() $x,y$

as well as to define the edge-cost

$x,y$

as well as to define the edge-cost

![]() $\mathcal {C}(xy)$

. This leads to the cost of the edge to depend essentially on the expected degrees of the two involved verticesFootnote

1

, however, it also leads to three layers of randomness. On the first layer, the vertex set has random vertex-weights; on the second layer, edges are drawn randomly using the randomness in the first layer, and finally, on the third layer, edge-costs depend on the presence of edges, on the vertex-weights, and on an extra source of randomness captured in

$\mathcal {C}(xy)$

. This leads to the cost of the edge to depend essentially on the expected degrees of the two involved verticesFootnote

1

, however, it also leads to three layers of randomness. On the first layer, the vertex set has random vertex-weights; on the second layer, edges are drawn randomly using the randomness in the first layer, and finally, on the third layer, edge-costs depend on the presence of edges, on the vertex-weights, and on an extra source of randomness captured in

![]() $L_{xy}$

.

$L_{xy}$

.

When

![]() $\mu \in (0,1)$

, a high-degree vertex still causes more new infections per unit time than a low-degree vertex, but this effect is sublinear in the degree. As

$\mu \in (0,1)$

, a high-degree vertex still causes more new infections per unit time than a low-degree vertex, but this effect is sublinear in the degree. As

![]() $\mu $

increases and/or the parameters of the underlying graph change, we prove that the following four different phases occur for the transmission time between the vertex at

$\mu $

increases and/or the parameters of the underlying graph change, we prove that the following four different phases occur for the transmission time between the vertex at

![]() $0$

and a far away vertex x, see Table 2 for the thresholds between the different phases:

$0$

and a far away vertex x, see Table 2 for the thresholds between the different phases:

-

(i)

$d_{\mathcal {C}}(0,x)$

converges to a limiting distribution that is independent of the Euclidean distance

$d_{\mathcal {C}}(0,x)$

converges to a limiting distribution that is independent of the Euclidean distance

$|x|$

(explosive phase);

$|x|$

(explosive phase);

This was the main result of [Reference Komjáthy, Lapinskas and Lengler55]. The main result of this paper is to characterise the other phases:

-

(ii)

$d_{\mathcal {C}}(0,x)$

grows at most polylogarithmically in the Euclidean distance

$d_{\mathcal {C}}(0,x)$

grows at most polylogarithmically in the Euclidean distance

$|x|$

, without being explosive;

$|x|$

, without being explosive; -

(iii)

$d_{\mathcal {C}}(0,x)$

grows polynomially in

$d_{\mathcal {C}}(0,x)$

grows polynomially in

$|x|$

, with exponent

$|x|$

, with exponent

$0<\eta _0 < 1$

;

$0<\eta _0 < 1$

; -

(iv)

$d_{\mathcal {C}}(0,x)$

grows linearly in

$d_{\mathcal {C}}(0,x)$

grows linearly in

$|x|$

, that is, with exponent

$|x|$

, that is, with exponent

$\eta _0=1$

.

$\eta _0=1$

.

These phases are highly robust in the parameters, they are not restricted to phase boundaries in either

![]() $\mu $

or the other model parameters. Moreover, all four phases can occur on a single underlying graph by changing the penalty exponent

$\mu $

or the other model parameters. Moreover, all four phases can occur on a single underlying graph by changing the penalty exponent

![]() $\mu $

only; universally across distributions of

$\mu $

only; universally across distributions of

![]() $L_{xy}$

with regularly varying behaviour at

$L_{xy}$

with regularly varying behaviour at

![]() $0$

, see Figure 1 for a visualisation. This rich behaviour arises despite the doubly logarithmic graph distances in the underlying spatial graph models. By contrast, in other models the behaviour of transmission times in classical FPP is less rich, see Section 1.1 for the discussion.

$0$

, see Figure 1 for a visualisation. This rich behaviour arises despite the doubly logarithmic graph distances in the underlying spatial graph models. By contrast, in other models the behaviour of transmission times in classical FPP is less rich, see Section 1.1 for the discussion.

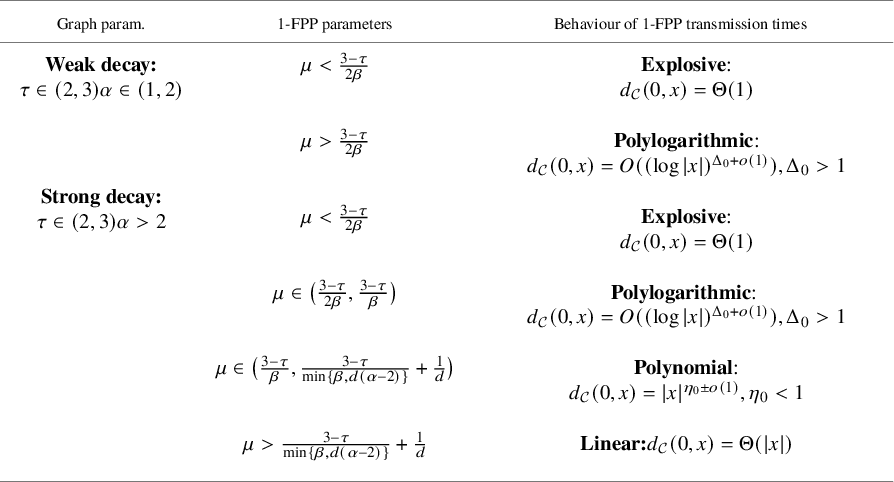

Table 2 Summary of our main results. In 1-FPP, edge transmission times are

![]() $L_{xy} (W_xW_y)^\mu $

where

$L_{xy} (W_xW_y)^\mu $

where

![]() $W_x, W_y$

are constant multiples of the expected degrees of the vertices

$W_x, W_y$

are constant multiples of the expected degrees of the vertices

![]() $x,y$

, and

$x,y$

, and

![]() $L_{xy}$

is i.i.d. with distribution function that varies regularly near

$L_{xy}$

is i.i.d. with distribution function that varies regularly near

![]() $0$

with exponent

$0$

with exponent

![]() $\beta \in (0,\infty ]$

. The degree distribution follows a power law with exponent

$\beta \in (0,\infty ]$

. The degree distribution follows a power law with exponent

![]() $\tau \in (2,3)$

: graph distances are doubly logarithmic in the underlying graph. The transmission time

$\tau \in (2,3)$

: graph distances are doubly logarithmic in the underlying graph. The transmission time

![]() $d_{\mathcal {C}}(0,x)$

between

$d_{\mathcal {C}}(0,x)$

between

![]() $0$

and a far away vertex x sweeps through four different phases as the penalty exponent

$0$

and a far away vertex x sweeps through four different phases as the penalty exponent

![]() $\mu $

increases. For long-range parameter

$\mu $

increases. For long-range parameter

![]() $\alpha \in (1,2)$

, long edges between low-degree vertices maintain polylogarithmic transmission times (similar to long-range percolation), so increasing

$\alpha \in (1,2)$

, long edges between low-degree vertices maintain polylogarithmic transmission times (similar to long-range percolation), so increasing

![]() $\mu $

stops explosion but it has no further effect. When

$\mu $

stops explosion but it has no further effect. When

![]() $\alpha>2$

, these edges are sparser and a larger

$\alpha>2$

, these edges are sparser and a larger

![]() $\mu $

slows down 1-FPP, to polynomial but sublinear transmission times in an interval of length at least

$\mu $

slows down 1-FPP, to polynomial but sublinear transmission times in an interval of length at least

![]() $1/d$

for

$1/d$

for

![]() $\mu $

. Then, all long edges have polynomial transmission times in the distance they bridge. For even higher penalty exponent

$\mu $

. Then, all long edges have polynomial transmission times in the distance they bridge. For even higher penalty exponent

![]() $\mu $

the behaviour becomes similar to FPP on the grid

$\mu $

the behaviour becomes similar to FPP on the grid

![]() $\mathbb {Z}^d$

. We give the growth exponents

$\mathbb {Z}^d$

. We give the growth exponents

![]() $\Delta _0$

and

$\Delta _0$

and

![]() $\eta _0$

explicitly in (1.9) and (1.10).

$\eta _0$

explicitly in (1.9) and (1.10).

Figure 1 Heatmaps for the four different universality classes. The vertices are sorted by their transmission times from the origin (centre vertex). The colours represent this ordering: yellow infected first, then orange, then purple. All four plots are generated on the same underlying graph (with parameters

![]() $\tau =2.3$

and

$\tau =2.3$

and

![]() $\alpha =5$

, and edge connection probabilities

$\alpha =5$

, and edge connection probabilities

![]() $p(u,v)=(w_u w_v / (\mathbb {E}[W]\|u-v\|^2))^5 \wedge 1$

), where the vertices are placed on a

$p(u,v)=(w_u w_v / (\mathbb {E}[W]\|u-v\|^2))^5 \wedge 1$

), where the vertices are placed on a

![]() $750 \times 750$

grid in the 2-dimensional torus. The random factors

$750 \times 750$

grid in the 2-dimensional torus. The random factors

![]() $L_{xy}$

associated to each edge are also identical in all four plots, and follow an exponential distribution (i.e.,

$L_{xy}$

associated to each edge are also identical in all four plots, and follow an exponential distribution (i.e.,

![]() $\beta =1$

). The only varying parameter is the penalty exponent

$\beta =1$

). The only varying parameter is the penalty exponent

![]() $\mu $

, taking values (i)

$\mu $

, taking values (i)

![]() $\mu =0$

for the explosive regime, (ii)

$\mu =0$

for the explosive regime, (ii)

![]() $\mu =0.5$

for the the polylogarithmic regime, (iii)

$\mu =0.5$

for the the polylogarithmic regime, (iii)

![]() $\mu =1$

for the polynomial regime (iv)

$\mu =1$

for the polynomial regime (iv)

![]() $\mu =2$

for the linear regime. In the linear regime, the late points are – typically – high degree vertices carrying high penalisation. We thank Zylan Benjert for generating the simulations and the pictures.

$\mu =2$

for the linear regime. In the linear regime, the late points are – typically – high degree vertices carrying high penalisation. We thank Zylan Benjert for generating the simulations and the pictures.

Precise behaviour in the four phases. In this paper we prove the upper bounds on transmission times in the sub-explosive regime (phase (i) was previous work [Reference Komjáthy, Lapinskas and Lengler55]). In phase (ii), we show that the transmission time is at most

![]() $(\log |x|)^{\Delta _0 + o(1)}$

with an explicit

$(\log |x|)^{\Delta _0 + o(1)}$

with an explicit

![]() $\Delta _0>1$

which we conjecture to be tight. In phases (iii) and (iv), we show that the transmission time is precisely

$\Delta _0>1$

which we conjecture to be tight. In phases (iii) and (iv), we show that the transmission time is precisely

![]() $|x|^{\eta _0 \pm o(1)}$

, where we give

$|x|^{\eta _0 \pm o(1)}$

, where we give

![]() $\eta _0<1$

explicitly for phase (iii) and

$\eta _0<1$

explicitly for phase (iii) and

![]() $\eta _0 =1$

for phase (iv). The companion paper [Reference Komjáthy, Lapinskas, Lengler and Schaller56] contains the matching lower bounds for phases (iii)-(iv) as well as some additional results for phase (iv). We develop new techniques that allow us to treat upper bounds for all three sub-explosive phases simultaneously, which we expect to be of independent interest.

$\eta _0 =1$

for phase (iv). The companion paper [Reference Komjáthy, Lapinskas, Lengler and Schaller56] contains the matching lower bounds for phases (iii)-(iv) as well as some additional results for phase (iv). We develop new techniques that allow us to treat upper bounds for all three sub-explosive phases simultaneously, which we expect to be of independent interest.

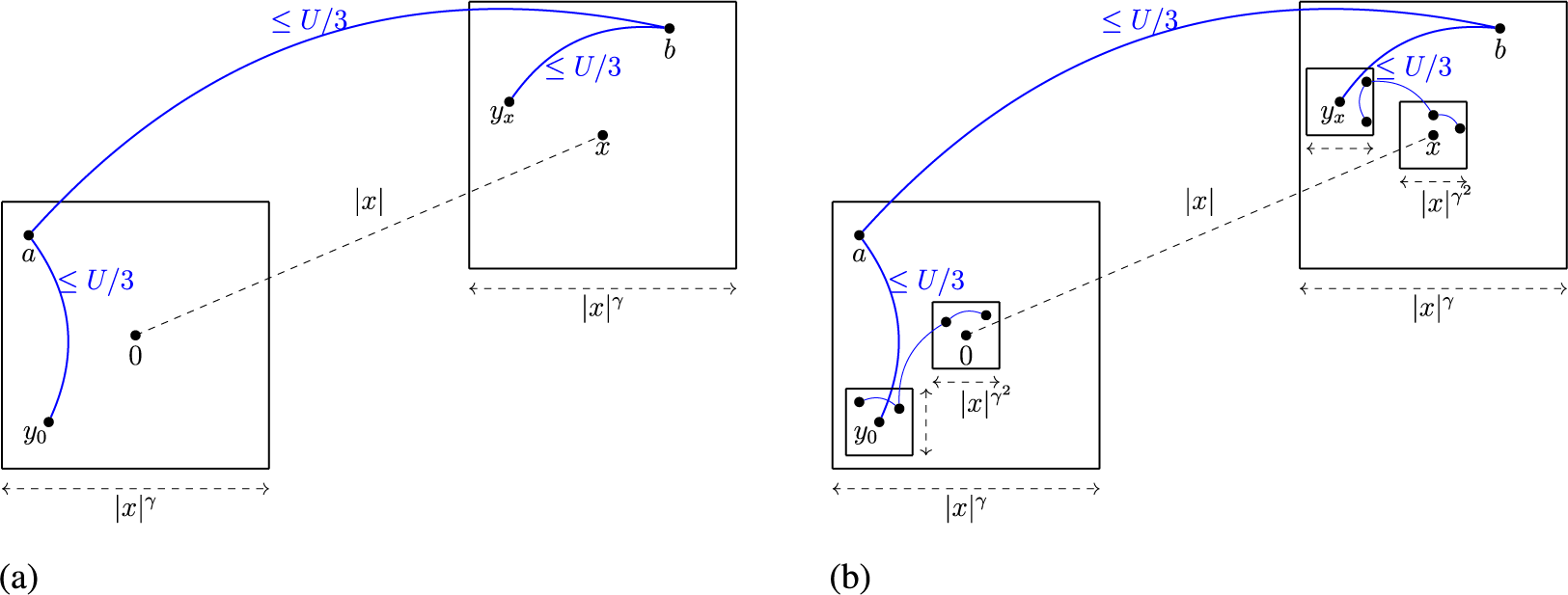

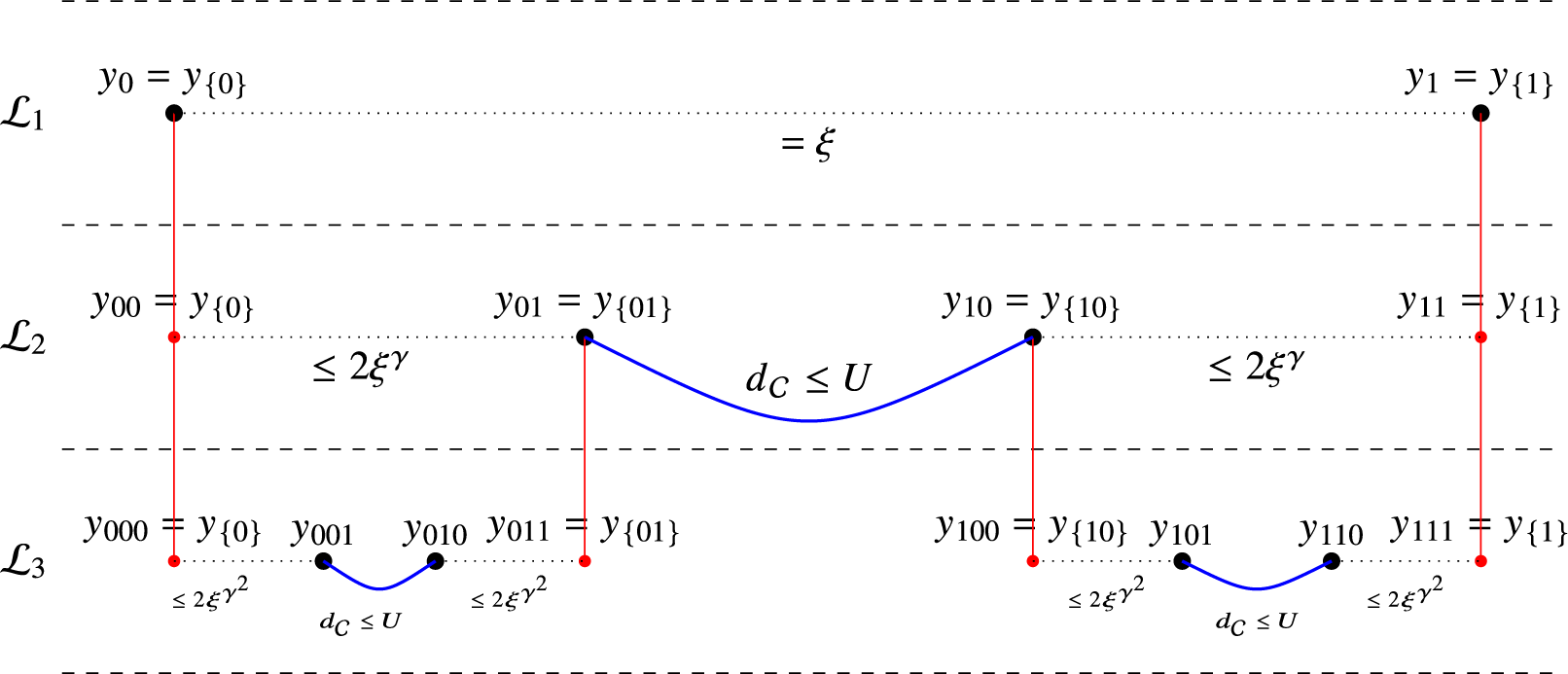

Figure 2 The budget travel plan with 3-edge bridging-paths: (a) first and (b) second iteration.

Motivation of the process from applications. One-dependent processes in general, and one-dependent FPP in particular, allow for more realistic modelling of real phenomena. In social networks, actual contacts and infections do not scale linearly with the degree [Reference Feldman and Janssen31, Reference Kroy59, Reference Wang, Xiong, Wang, Cai, Wu, Wang and Chen76, Reference Ke, Zitzmann, Ho, Ribeiro and Perelson54]. 1-FPP type penalisation has frequently been used to model the sublinear impact of superspreaders [Reference Giuraniuc, Hatchett, Indekeu, Leone, Castillo, Van Schaeybroeck and Vanderzande37, Reference Karsai, Juhász and Iglói53, Reference Miritello, Moro, Lara, Martínez-López, Belchamber, Roberts and Dunbar65, Reference Pu, Li and Yang69, Reference Yang, Zhou, Xie, Lai and Wang77, Reference Baxter and Timár6], and in other contexts [Reference Bonaventura, Nicosia and Latora16, Reference Ding and Li30, Reference Lee, Yook and Kim62, Reference Zlatić, Gabrielli and Caldarelli78, Reference Andrade, Andrade and Herrmann3, Reference Hooyberghs, Van Schaeybroeck, Moreira, Andrade, Herrmann and Indekeu49]. Consistent with our model, all these applications assume a polynomial dependence with exponent in the range

![]() $\mu \in (0,1)$

, where a high-degree vertex may cause more new infections per time than a low-degree vertex, but this effect is sublinear in the degree.

$\mu \in (0,1)$

, where a high-degree vertex may cause more new infections per time than a low-degree vertex, but this effect is sublinear in the degree.

While our paper is theoretical, we do believe that a model with a rich phase space can have practical implications. In the spread of physical epidemics, while some diseases spread at an exponential rate, others spread at a polynomial rate, dominated by the local geometry. Examples of the latter include HIV/AIDS, Ebola, and foot-and-mouth disease, see the survey [Reference Chowell, Bansal, Sattenspiel and Viboud21] on polynomial epidemic growth. Classical epidemic models can typically only model either exponential or polynomial growth, not both. Arguably,

![]() $1$

-FPP provides a natural explanation, since in

$1$

-FPP provides a natural explanation, since in

![]() $1$

-FPP the transition can be driven by changes only to the transmission dynamics, not to the underlying network.

$1$

-FPP the transition can be driven by changes only to the transmission dynamics, not to the underlying network.

New methodology: moving to quenched vertex-set to replace FKG-inequality. In this paper we develop a general technique – nets combined with multiround exposure – that replaces the FKG-inequality [Reference Fortuin, Kasteleyn and Ginibre32] in problems concerning vertex and/or edge-weighted graph models where this inequality does not hold. Let us explain why the FKG-inequality fails in the context of 1-FPP. Typically, for upper bounds one constructs paths connecting

![]() $0$

and x by revealing vertices and/or edges of the graph sequentially, which destroys the independence of edges. For graph distances in long-range percolation, the FKG-inequality resolves this problem [Reference Biskup11], but it already needs adjustments once vertex-weights are present [Reference Gracar, Lüchtrath and Mönch41]. In 1-FPP, the existence of a long edge is positively correlated to its endpoints having large vertex weights, which is negatively correlated to its other outgoing edges having short transmission times. Hence, having chosen a long edge with low-cost, we lose probabilistic control over how to choose the next low-cost edge on the path connecting

$0$

and x by revealing vertices and/or edges of the graph sequentially, which destroys the independence of edges. For graph distances in long-range percolation, the FKG-inequality resolves this problem [Reference Biskup11], but it already needs adjustments once vertex-weights are present [Reference Gracar, Lüchtrath and Mönch41]. In 1-FPP, the existence of a long edge is positively correlated to its endpoints having large vertex weights, which is negatively correlated to its other outgoing edges having short transmission times. Hence, having chosen a long edge with low-cost, we lose probabilistic control over how to choose the next low-cost edge on the path connecting

![]() $0$

and x. To overcome this issue, we move to the (weighted-vertex) quenched setting where we reveal the realisation of the whole weighted vertex set – say

$0$

and x. To overcome this issue, we move to the (weighted-vertex) quenched setting where we reveal the realisation of the whole weighted vertex set – say

![]() $(\mathcal {V}, \mathcal {W})=(V, w_V)$

– and thus events concerning only edges become independent. We show that in a large box centred at the origin of

$(\mathcal {V}, \mathcal {W})=(V, w_V)$

– and thus events concerning only edges become independent. We show that in a large box centred at the origin of

![]() $\mathbb {R}^d$

, the proportion of realisations with behaviour ‘close to what is expected’ tends to

$\mathbb {R}^d$

, the proportion of realisations with behaviour ‘close to what is expected’ tends to

![]() $1$

with the box-size. More precisely, we require that locally around a constant proportion of the vertices and uniformly across multiple scales of vertex-weights, the number of points in the weighted vertex set is close to its expectation. For this we select a subset of the vertices that we call a net realising this property. A net

$1$

with the box-size. More precisely, we require that locally around a constant proportion of the vertices and uniformly across multiple scales of vertex-weights, the number of points in the weighted vertex set is close to its expectation. For this we select a subset of the vertices that we call a net realising this property. A net

![]() $\mathcal {N}$

is thus a subset of the weighted vertex set, such that for every not-too-small radius r, every ‘reasonable’ weight w, and every selected vertex

$\mathcal {N}$

is thus a subset of the weighted vertex set, such that for every not-too-small radius r, every ‘reasonable’ weight w, and every selected vertex

![]() $v\in \mathcal {N}$

, the net has constant density in

$v\in \mathcal {N}$

, the net has constant density in

![]() $B_r(v)\times [w, 2w]$

, shorthand for vertices of weight in

$B_r(v)\times [w, 2w]$

, shorthand for vertices of weight in

![]() $[w,2w]$

within Euclidean distance r of v:

$[w,2w]$

within Euclidean distance r of v:

$$ \begin{align} \frac{|\mathcal{N}\cap B_r(v)\times[w, 2w]|}{\mathbb{E}\big[|\mathcal{V} \cap B_r(v)\times [w,2w]|\mid v\in \mathcal{V}\big]} \in \Big(\frac{1}{16}, 16\Big), \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \frac{|\mathcal{N}\cap B_r(v)\times[w, 2w]|}{\mathbb{E}\big[|\mathcal{V} \cap B_r(v)\times [w,2w]|\mid v\in \mathcal{V}\big]} \in \Big(\frac{1}{16}, 16\Big), \end{align} $$

where the expectation is taken over the randomness in the weights and location of verticesFootnote

2

. We prove via a multiscale analysis that as the box-size tends to infinity, asymptotically almost every realisation of the weighted vertex set contains a net

![]() $\mathcal N$

with total density at least

$\mathcal N$

with total density at least

![]() $1/4$

.

$1/4$

.

When we move to the quenched setting we only reveal the realisation of the weighted vertex set, but not the edges of the graph. In realisations containing a net, with a carefully chosen multiround exposure process we can define a coupling of the edges and their costs which lets us replace the FKG inequality needed for the construction of a low-cost path between

![]() $0 $

and x, see Section 3 for more details. We believe that this method is also useful for many other graph models, so we explain it streamlined now.

$0 $

and x, see Section 3 for more details. We believe that this method is also useful for many other graph models, so we explain it streamlined now.

Budget travel plan with 3-edge bridge-paths. Switching to the quenched setting allows to prove the upper bounds in all subexponential phases (ii)–(iv) all-at-once. Our construction of a connecting path overcomes the following problem: A long edge with a short transmission time typically occurs on typical high-degree vertices and thus all other outgoing edges from the same vertices have too long transmission times. The main idea resembles a ‘budget travel plan’: when someone travels with a low budget, one takes the cheapest mode of transport to the airport within a

![]() $100$

km radius that offers the cheapest flight landing within a

$100$

km radius that offers the cheapest flight landing within a

![]() $100$

km radius of the destination, then takes the cheapest transport to the destination city.

$100$

km radius of the destination, then takes the cheapest transport to the destination city.

Formally, we put balls of radius

![]() $|x|^\gamma $

for some

$|x|^\gamma $

for some

![]() $\gamma \in (0,1)$

around

$\gamma \in (0,1)$

around

![]() $0$

and around x, and we find a cheap

$0$

and around x, and we find a cheap

![]() $3$

-edge path (‘bridge’)

$3$

-edge path (‘bridge’)

![]() $\pi _1 = y_0aby_x$

between these two balls using only vertices in the net. The net guarantees enough vertices in each vertex-weight range of interest. We find atypical high-weight vertices

$\pi _1 = y_0aby_x$

between these two balls using only vertices in the net. The net guarantees enough vertices in each vertex-weight range of interest. We find atypical high-weight vertices

![]() $a,b$

that are connected by an atypically cheap edge, that simultaneously have an atypically cheap edge to low-weight vertices

$a,b$

that are connected by an atypically cheap edge, that simultaneously have an atypically cheap edge to low-weight vertices

![]() $y_0, y_x$

, respectively. (Here we use the common terminology of fast transmission corresponding to ‘cheap’ cost.) Then we have replaced the task of connecting

$y_0, y_x$

, respectively. (Here we use the common terminology of fast transmission corresponding to ‘cheap’ cost.) Then we have replaced the task of connecting

![]() $0$

and x by the two tasks of connecting

$0$

and x by the two tasks of connecting

![]() $0$

with

$0$

with

![]() $y_0$

and x with

$y_0$

and x with

![]() $y_x$

, where the new ‘gaps’

$y_x$

, where the new ‘gaps’

![]() $|0-y_0|$

and

$|0-y_0|$

and

![]() $|x-y_x|$

are much smaller than

$|x-y_x|$

are much smaller than

![]() $|x|$

. The multiround exposure and the net on the fixed vertex set together guarantee that we can iterate this process without running out vertices in the relevant weight-ranges, and without accumulated correlations in the presence of edges along the iteration (e.g., out of

$|x|$

. The multiround exposure and the net on the fixed vertex set together guarantee that we can iterate this process without running out vertices in the relevant weight-ranges, and without accumulated correlations in the presence of edges along the iteration (e.g., out of

![]() $y_0, y_x$

). Iteration yields a set of multiscale bridge-paths, which we call after Biskup a hierarchy [Reference Biskup11]. The construction in [Reference Biskup11] also uses recursion, with one-edge bridges instead of three-edge bridges, and yields polylogarithmic graph distances in long-range percolation. The techniques in [Reference Biskup11] would not work for 1-FPP because we need to balance distances vs costs vs the penalisation on high-weight vertices in very different regimes, and at the same time deal with edge-costs dependencies. Those can only be dealt with in the quenched setting.

$y_0, y_x$

). Iteration yields a set of multiscale bridge-paths, which we call after Biskup a hierarchy [Reference Biskup11]. The construction in [Reference Biskup11] also uses recursion, with one-edge bridges instead of three-edge bridges, and yields polylogarithmic graph distances in long-range percolation. The techniques in [Reference Biskup11] would not work for 1-FPP because we need to balance distances vs costs vs the penalisation on high-weight vertices in very different regimes, and at the same time deal with edge-costs dependencies. Those can only be dealt with in the quenched setting.

The cost (transmission time) of the bridge-paths

![]() $\pi $

in 1-FPP are either polynomial in the distance they bridge or constant. When the cost is polynomial – with optimal exponent

$\pi $

in 1-FPP are either polynomial in the distance they bridge or constant. When the cost is polynomial – with optimal exponent

![]() $\eta _0$

– we are in the polynomial phase. The cost of the first bridge

$\eta _0$

– we are in the polynomial phase. The cost of the first bridge

![]() $\pi _1$

then dominates the cost of the whole path, and we only carry out a constant number of iterations (irrespective of

$\pi _1$

then dominates the cost of the whole path, and we only carry out a constant number of iterations (irrespective of

![]() $|x|$

). When bridge-paths with constant cost exist, we are in the polylogarithmic phase. Then, the cost of all bridges together is negligible compared to the cost of the polylogarithmic number of gaps that remain after the last iteration. Here, we iterate until we can connect the remaining gaps via essentially constant cost paths. Connecting the gaps is a nontrivial task itself since the graphs do not contain ‘nearest-neighbour’ edges. Solutions for filling gaps in [Reference Biskup11] do not work in our setting due to the presence of vertex weights. Instead, we connect the gaps with ‘weight-increasing paths’ that crucially use that the underlying graphs are scale-free. We give a more detailed discussion about the hierarchical construction at the beginning of Section 5 and back-of-the-envelope calculations about how to obtain the precise growth exponents in phases (ii) and (iii) at the beginning of Section 5.1 with proof sketches below Corollaries 5.2 and 5.3.

$|x|$

). When bridge-paths with constant cost exist, we are in the polylogarithmic phase. Then, the cost of all bridges together is negligible compared to the cost of the polylogarithmic number of gaps that remain after the last iteration. Here, we iterate until we can connect the remaining gaps via essentially constant cost paths. Connecting the gaps is a nontrivial task itself since the graphs do not contain ‘nearest-neighbour’ edges. Solutions for filling gaps in [Reference Biskup11] do not work in our setting due to the presence of vertex weights. Instead, we connect the gaps with ‘weight-increasing paths’ that crucially use that the underlying graphs are scale-free. We give a more detailed discussion about the hierarchical construction at the beginning of Section 5 and back-of-the-envelope calculations about how to obtain the precise growth exponents in phases (ii) and (iii) at the beginning of Section 5.1 with proof sketches below Corollaries 5.2 and 5.3.

Robustness of our techniques. The technique of nets combined with multiround edge-exposure is robust, and will be applicable elsewhere, for questions concerning first passage percolation, robustness to percolation (random deletion of edges), graph distances, SIR-type and other epidemic processes, rumour spreading, etc. on a larger class of vertex-weighted graphs; including random geometric graphs, Boolean models with random radii, the age-dependent and the weight-dependent random connection model (mimicking spatial preferential attachment), scale-free Gilbert graph, and the models used here [Reference Aiello, Bonato, Cooper, Janssen and Prałat2, Reference Cooper, Frieze and Prałat23, Reference Gracar, Grauer, Lüchtrath and Mörters38, Reference Gracar, Grauer and Mörters39, Reference Gracar, Heydenreich, Mönch and Mörters40, Reference Gracar, Lüchtrath and Mönch41, Reference Gracar, Lüchtrath and Mörters42, Reference Hirsch47, Reference Jacob and Mörters50], and can also be extended to dynamical versions of the above graph models on fixed vertex sets.

Two papers, two techniques and optimality. The ‘budget travel plan’ together with the renormalisation group argument in [Reference Komjáthy, Lapinskas, Lengler and Schaller56] reveals that the strategy of polynomial paths is essentially optimal: in this phase, all long edges have polynomial transmission time in the distance they bridge. Our techniques for the lower bounds are entirely different and deserve their own exposition, hence we present them in the companion paper [Reference Komjáthy, Lapinskas, Lengler and Schaller56].

1.1 Related work: phases of FPP in other models.

The phase diagrams of transmission times in classical FPP are less rich. In particular, the strict polynomial phase is absent or restricted only to phase transition boundaries. Indeed, on sparse nonspatial graph models with finite-variance degrees, both Markovian and non-Markovian classical FPP universally show Malthusian (exponential) growth [Reference Bhamidi, van der Hofstad and Hooghiemstra9]. Transmission times between two uniformly chosen vertices are then logarithmic in the graph size. Sparse spatial graphs with finite-variance degrees (e.g., percolation, long-range percolation, random geometric graphs etc.) are typically restricted to linear graph distances/transmission times in the absence of long edges [Reference Antal and Pisztora4, Reference Penrose68, Reference Cox and Durrett25], or to polylogarithmic distances in the presence of long edges [Reference Biskup11, Reference Biskup and Lin12, Reference Hao and Heydenreich46]. In both spatial and nonspatial graph models with infinite-variance degrees, classical FPP typically either explodes or exhibits a smooth transition between explosion and doubly logarithmic transmission times (which match the graph distances) [Reference Adriaans and Komjáthy1, Reference Jorritsma and Komjáthy51, Reference van der Hofstad and Komjáthy75]; in particular, there is no analogue of phases (ii)–(iv). For one-dependent FPP on nonspatial graphs there are strong indications that the process either explodes [Reference Slangen73], with the same criterion for explosion as for spatial graphs in [Reference Komjáthy, Lapinskas and Lengler55], or becomes Malthusian [Reference Fransson34], the latter implying logarithmic transmission times between two uniformly chosen vertices by the universality in [Reference Bhamidi, van der Hofstad and Hooghiemstra9], so only two phases can occur. The only graph model to exhibit a transition from a fast-growing phase to a slow-growing phase is long-range percolation, where the polynomial phase is restricted to the phase boundary in the long-range parameter

![]() $\alpha =2$

[Reference Bäumler5]. Even in degenerate models (where the underlying graph is complete), long-range first passage percolation [Reference Chatterjee and Dey20] is the only other model where a similarly rich set of phases is known to occur. Thus one-dependent FPP is the first process that displays a full interpolation between the four phases on a single nondegenerate graph model. Moreover, the phase boundaries for one-dependent FPP depend nontrivially on the main model parameters: the degree power-law exponent

$\alpha =2$

[Reference Bäumler5]. Even in degenerate models (where the underlying graph is complete), long-range first passage percolation [Reference Chatterjee and Dey20] is the only other model where a similarly rich set of phases is known to occur. Thus one-dependent FPP is the first process that displays a full interpolation between the four phases on a single nondegenerate graph model. Moreover, the phase boundaries for one-dependent FPP depend nontrivially on the main model parameters: the degree power-law exponent

![]() $\tau $

, the parameter

$\tau $

, the parameter

![]() $\alpha $

controlling the prevalence of long-range edges, and the behaviour of

$\alpha $

controlling the prevalence of long-range edges, and the behaviour of

![]() $L_{xy}$

near

$L_{xy}$

near

![]() $0$

characterised by

$0$

characterised by

![]() $\beta $

, see Table 2 for our results, Table 3 for phases of growth in other models, and Section 1.4 for more details on related work.

$\beta $

, see Table 2 for our results, Table 3 for phases of growth in other models, and Section 1.4 for more details on related work.

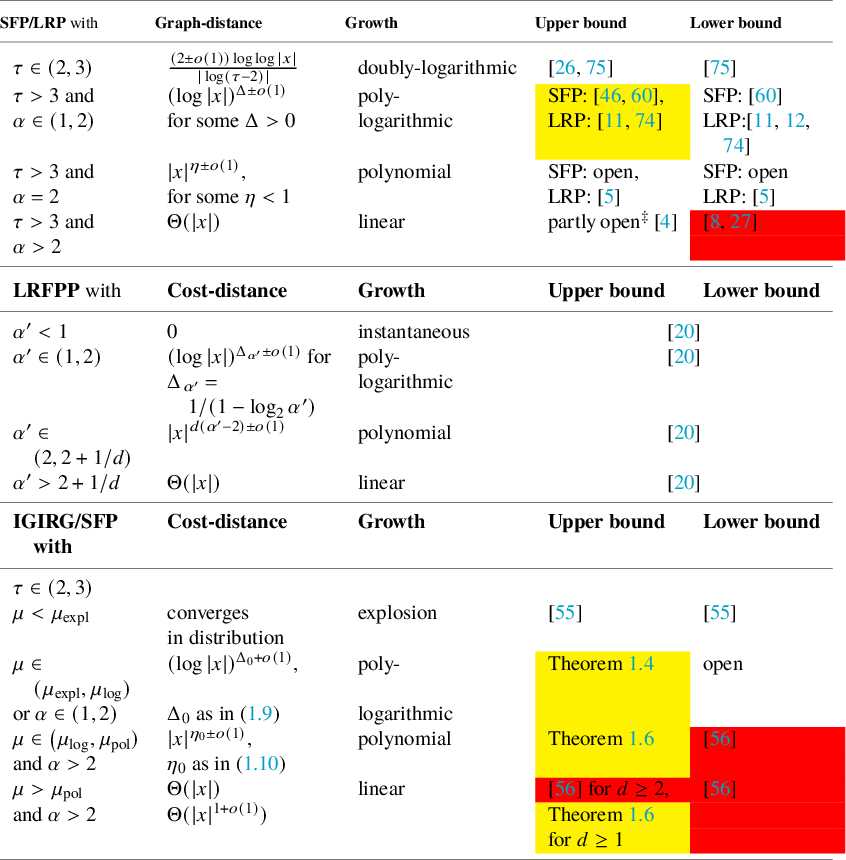

Table 3 Known results about the universality classes of graph-distances on long-range percolation LRP, scale-free percolation SFP, long-range first-passage percolation LRFPP and infinite geometric inhomogeneous random graphs IGIRG. The results highlighted in yellow color follow (also) from techniques in this paper.

![]() $^\ddagger $

An upper bound is only known for high enough edge-density or all nearest-neighbour edges present.

$^\ddagger $

An upper bound is only known for high enough edge-density or all nearest-neighbour edges present.

1.2 Graph Models

We consider simple and undirected graphs with vertex set

![]() $\mathcal {V} \subseteq \mathbb {R}^d$

. We use standard graph notation along with other common terminology, see Section 1.4.1. We consider three random graph models: Scale-Free Percolation (SFP), Infinite Geometric Inhomogeneous Random Graphs (IGIRG)Footnote

3

, and (finite) Geometric Inhomogeneous Random Graphs (GIRG). The latter model contains Hyperbolic Random Graphs (HypRG) as special case, so our results extend to HypRG, see the paragraph below Theorem 1.11. The main difference between SFP and IGIRG is the vertex set

$\mathcal {V} \subseteq \mathbb {R}^d$

. We use standard graph notation along with other common terminology, see Section 1.4.1. We consider three random graph models: Scale-Free Percolation (SFP), Infinite Geometric Inhomogeneous Random Graphs (IGIRG)Footnote

3

, and (finite) Geometric Inhomogeneous Random Graphs (GIRG). The latter model contains Hyperbolic Random Graphs (HypRG) as special case, so our results extend to HypRG, see the paragraph below Theorem 1.11. The main difference between SFP and IGIRG is the vertex set

![]() $\mathcal {V}$

. For SFP, we use

$\mathcal {V}$

. For SFP, we use

![]() $\mathcal {V} := \mathbb Z^d$

, with

$\mathcal {V} := \mathbb Z^d$

, with

![]() $d \in \mathbb {N}$

. For IGIRG, a unit-intensity Poisson point process on

$d \in \mathbb {N}$

. For IGIRG, a unit-intensity Poisson point process on

![]() $\mathbb R^d$

forms

$\mathbb R^d$

forms

![]() $\mathcal {V}$

.

$\mathcal {V}$

.

Definition 1.3 (SFP, IGIRG, GIRG).

Let

![]() $d\in \mathbb {N}$

,

$d\in \mathbb {N}$

,

![]() $\tau>2$

,

$\tau>2$

,

![]() $\alpha \in (1,\infty )$

, and

$\alpha \in (1,\infty )$

, and

![]() $\overline {c}>\underline {c}>0$

. Let

$\overline {c}>\underline {c}>0$

. Let

![]() $\ell :[1,\infty )\rightarrow (0,\infty )$

be function that varies slowly at infinity (see Section 1.4.1), and let

$\ell :[1,\infty )\rightarrow (0,\infty )$

be function that varies slowly at infinity (see Section 1.4.1), and let

![]() $h:\mathbb {R}^d\times [1,\infty )\times [1,\infty )\rightarrow [0,1]$

be a function satisfying

$h:\mathbb {R}^d\times [1,\infty )\times [1,\infty )\rightarrow [0,1]$

be a function satisfying

$$ \begin{align} \underline{c}\cdot\min\left\{1, \dfrac{w_1w_2}{|x|^d}\right\}^{\alpha} \le h(x,w_1,w_2)\le \overline{c}\cdot\min\left\{1, \dfrac{w_1w_2}{|x|^d}\right\}^{\alpha}. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \underline{c}\cdot\min\left\{1, \dfrac{w_1w_2}{|x|^d}\right\}^{\alpha} \le h(x,w_1,w_2)\le \overline{c}\cdot\min\left\{1, \dfrac{w_1w_2}{|x|^d}\right\}^{\alpha}. \end{align} $$

The vertex set and vertex-weights: For SFP, set

![]() $\mathcal {V} := \mathbb Z^d$

, for IGIRG, let

$\mathcal {V} := \mathbb Z^d$

, for IGIRG, let

![]() $\mathcal {V}$

be given by a Poisson point process on

$\mathcal {V}$

be given by a Poisson point process on

![]() $\mathbb R^d$

of intensity one.Footnote

4

For each

$\mathbb R^d$

of intensity one.Footnote

4

For each

![]() $v\in \mathcal {V}$

, we draw a weight

$v\in \mathcal {V}$

, we draw a weight

![]() $W_v$

independently from a probability distribution on

$W_v$

independently from a probability distribution on

![]() $[1, \infty )$

satisfying

$[1, \infty )$

satisfying

We denote

![]() $\widetilde {\mathcal {V}}(G):=(\mathcal {V}, \mathcal {W})$

the vertex set

$\widetilde {\mathcal {V}}(G):=(\mathcal {V}, \mathcal {W})$

the vertex set

![]() $\mathcal {V}$

together with the random weight vector

$\mathcal {V}$

together with the random weight vector

![]() $\mathcal {W}_{\mathcal {V}}:=(W_v)_{v\in \mathcal {V}}$

, and

$\mathcal {W}_{\mathcal {V}}:=(W_v)_{v\in \mathcal {V}}$

, and

![]() $(V,w_V):=(V, (w_v)_{v\in V})$

a realisation of

$(V,w_V):=(V, (w_v)_{v\in V})$

a realisation of

![]() $\widetilde {\mathcal {V}}:=\widetilde {\mathcal {V}}(G)$

, where

$\widetilde {\mathcal {V}}:=\widetilde {\mathcal {V}}(G)$

, where

![]() $\tilde {v}:=(v, w_v)$

stands for a single weighted vertex.

$\tilde {v}:=(v, w_v)$

stands for a single weighted vertex.

The edge set: Conditioned on

![]() $\widetilde {\mathcal {V}}=(V, w_V)$

, consider all unordered pairs

$\widetilde {\mathcal {V}}=(V, w_V)$

, consider all unordered pairs

![]() $\mathcal {V}^{\scriptscriptstyle {(2)}}$

of

$\mathcal {V}^{\scriptscriptstyle {(2)}}$

of

![]() $\mathcal {V}$

. Then every pair

$\mathcal {V}$

. Then every pair

![]() $xy\in \mathcal {V}^{\scriptscriptstyle {(2)}}$

is present in

$xy\in \mathcal {V}^{\scriptscriptstyle {(2)}}$

is present in

![]() $\mathcal {E}(G)$

independently with probability

$\mathcal {E}(G)$

independently with probability

![]() $h(x-y,w_x,w_y)$

.

$h(x-y,w_x,w_y)$

.

Finally, a GIRG

![]() $G_n$

is obtained as the induced subgraph

$G_n$

is obtained as the induced subgraph

![]() $G[Q_n]$

of an IGIRG G by the set of vertices in the cube

$G[Q_n]$

of an IGIRG G by the set of vertices in the cube

![]() $Q_n$

of volume n centred at

$Q_n$

of volume n centred at

![]() $0$

. We call h the connection probability, d the dimension,

$0$

. We call h the connection probability, d the dimension,

![]() $\tau $

the power-law exponent, and

$\tau $

the power-law exponent, and

![]() $\alpha $

the long-range parameter.

$\alpha $

the long-range parameter.

The above definition essentially merges the Euclidean space and the vertex-weight space by considering vertices with weights as points in

![]() $\mathbb {R}^d \times [1, \infty )$

, that is, we think of each vertex as a pair

$\mathbb {R}^d \times [1, \infty )$

, that is, we think of each vertex as a pair

![]() $\tilde v=(v, w_v)$

, where

$\tilde v=(v, w_v)$

, where

![]() $v\in \mathbb {R}^d$

is its spatial location and

$v\in \mathbb {R}^d$

is its spatial location and

![]() $w_v$

is its weight. While SFP is a somewhat simpler model due to the deterministic location of vertices, GIRGs gained significant attention in both applications and theoretical studies [Reference Bläsius and Fischbeck13, Reference Bläsius, Friedrich, Katzmann, Meyer, Penschuck and Weyand14, Reference Hofstad, van der Hoorn and Maitra48, Reference Michielan, Litvak and Stegehuis63, Reference Michielan and Stegehuis64, Reference Ódor, Czifra, Komjáthy, Lovász and Karsai67], and are part of a larger class of marked random connection models [Reference Caicedo and Dickson19, Reference Gracar, Lüchtrath and Mörters42, Reference Gracar, Heydenreich, Mönch and Mörters40]. Definition 1.3 leads to a slightly less general model than those, for example, in [Reference Bringmann, Keusch and Lengler17] and [Reference Komjáthy, Lapinskas and Lengler55]. The original definition in [Reference Bringmann, Keusch and Lengler17] had a different scaling of the geometric space vs connection probabilities and (also) considered the torus topology on the unit cube, identifying ‘left’ and ‘right’ boundaries. However, the resulting finite graphs are identical in distribution after rescaling, and the torus topology vs Euclidean topology does not make a difference for the results below on cost-distances, see [Reference Komjáthy, Lapinskas and Lengler55] for a comparison. We discuss extensions to

$w_v$

is its weight. While SFP is a somewhat simpler model due to the deterministic location of vertices, GIRGs gained significant attention in both applications and theoretical studies [Reference Bläsius and Fischbeck13, Reference Bläsius, Friedrich, Katzmann, Meyer, Penschuck and Weyand14, Reference Hofstad, van der Hoorn and Maitra48, Reference Michielan, Litvak and Stegehuis63, Reference Michielan and Stegehuis64, Reference Ódor, Czifra, Komjáthy, Lovász and Karsai67], and are part of a larger class of marked random connection models [Reference Caicedo and Dickson19, Reference Gracar, Lüchtrath and Mörters42, Reference Gracar, Heydenreich, Mönch and Mörters40]. Definition 1.3 leads to a slightly less general model than those, for example, in [Reference Bringmann, Keusch and Lengler17] and [Reference Komjáthy, Lapinskas and Lengler55]. The original definition in [Reference Bringmann, Keusch and Lengler17] had a different scaling of the geometric space vs connection probabilities and (also) considered the torus topology on the unit cube, identifying ‘left’ and ‘right’ boundaries. However, the resulting finite graphs are identical in distribution after rescaling, and the torus topology vs Euclidean topology does not make a difference for the results below on cost-distances, see [Reference Komjáthy, Lapinskas and Lengler55] for a comparison. We discuss extensions to

![]() $\alpha = \infty $

and

$\alpha = \infty $

and

![]() $\beta = \infty $

separately in Section 1.3.1. We call the set of parameters

$\beta = \infty $

separately in Section 1.3.1. We call the set of parameters

![]() ${\texttt {par}} := \{d, \tau , \alpha , \mu , \beta , \underline {c}, \overline {c}, c_1, c_2, t_0\}$

the model parameters. We say that a variable is large (or small) relative to a collection of other variables when it is bounded below (or above) by some finite positive function of those variables and the model parameters. We restrict to

${\texttt {par}} := \{d, \tau , \alpha , \mu , \beta , \underline {c}, \overline {c}, c_1, c_2, t_0\}$

the model parameters. We say that a variable is large (or small) relative to a collection of other variables when it is bounded below (or above) by some finite positive function of those variables and the model parameters. We restrict to

![]() $\tau \in (2,3)$

, (explicitly stated in the theorems), which ensures that there is a unique infinite component (or linear-sized ‘giant’ component for finite GIRG)Footnote

5

and that graph distances between vertices

$\tau \in (2,3)$

, (explicitly stated in the theorems), which ensures that there is a unique infinite component (or linear-sized ‘giant’ component for finite GIRG)Footnote

5

and that graph distances between vertices

![]() $x,y$

in the infinite/giant component grow like

$x,y$

in the infinite/giant component grow like

![]() $d_G(x,y) \sim 2\log \log |x-y|/|\log (\tau -2)|$

in all three models [Reference Komjáthy and Lodewijks57, Reference Bringmann, Keusch and Lengler18, Reference Deijfen, van der Hofstad and Hooghiemstra26, Reference van der Hofstad and Komjáthy75]. We consider

$d_G(x,y) \sim 2\log \log |x-y|/|\log (\tau -2)|$

in all three models [Reference Komjáthy and Lodewijks57, Reference Bringmann, Keusch and Lengler18, Reference Deijfen, van der Hofstad and Hooghiemstra26, Reference van der Hofstad and Komjáthy75]. We consider

![]() $\mu $

as the easiest parameter to change: increasing

$\mu $

as the easiest parameter to change: increasing

![]() $\mu $

means gradually slowing down the spreading process around high-degree vertices, which corresponds to adjusting behaviour of individuals with high number of contacts. Hence, we will phrase our results from this perspective. Figure 3 shows two phase diagrams: one where

$\mu $

means gradually slowing down the spreading process around high-degree vertices, which corresponds to adjusting behaviour of individuals with high number of contacts. Hence, we will phrase our results from this perspective. Figure 3 shows two phase diagrams: one where

![]() $\mu $

is fixed and

$\mu $

is fixed and

![]() $\tau , \alpha $

vary; another where

$\tau , \alpha $

vary; another where

![]() $\tau $

is fixed and

$\tau $

is fixed and

![]() $\mu ,\alpha $

vary.

$\mu ,\alpha $

vary.

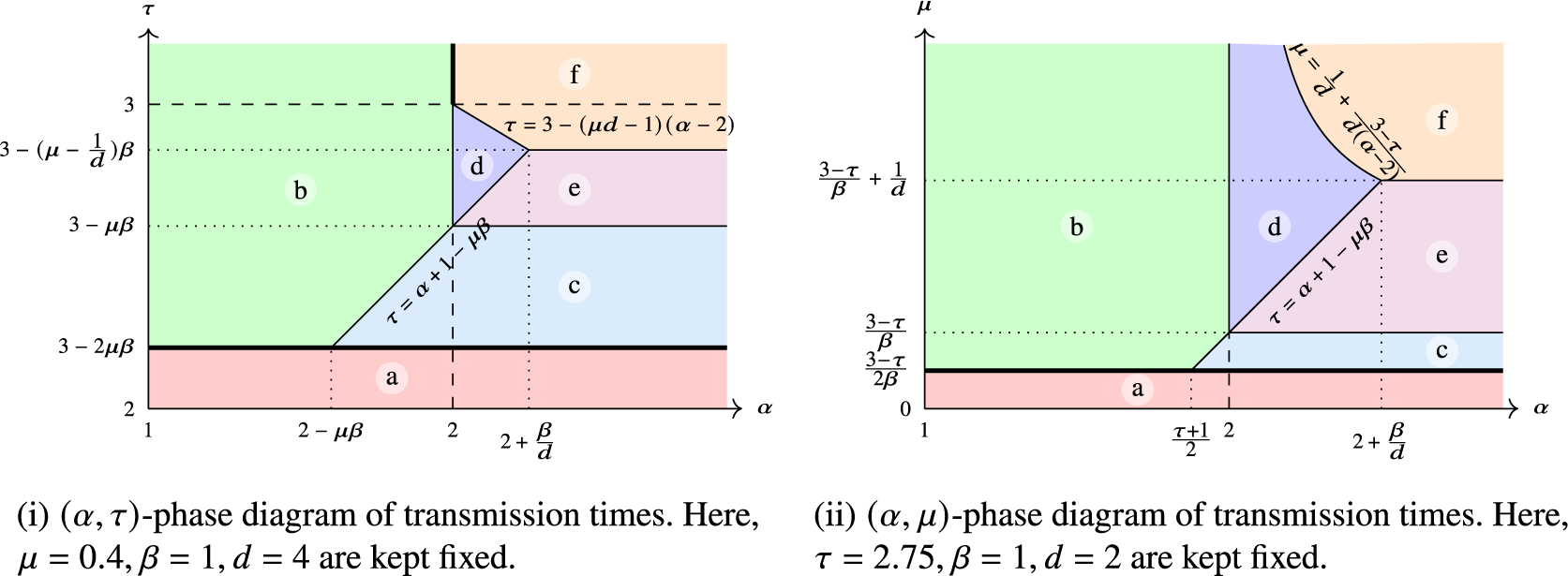

Figure 3 Phase diagrams of transmission times in one-dependent first passage percolation. On both diagrams, parameter choices falling in area (a) yield explosive spread. Parameter choices in areas (b) and (c) yield polylogarithmic transmission times

![]() $d_{\mathcal C}(0,x)\le (\log \|x\|)^{\Delta _0+o(1)}$

, where

$d_{\mathcal C}(0,x)\le (\log \|x\|)^{\Delta _0+o(1)}$

, where

![]() $\Delta _0=\Delta _\alpha = 1/(1-\log _2\alpha )$

on (b) and

$\Delta _0=\Delta _\alpha = 1/(1-\log _2\alpha )$

on (b) and

![]() $\Delta _0=\Delta _\beta =1/(1-\log _2(\tau -1-\mu \beta ))$

on (c). Parameter choices in areas (d), (e) and (f) yield polynomial transmission times,

$\Delta _0=\Delta _\beta =1/(1-\log _2(\tau -1-\mu \beta ))$

on (c). Parameter choices in areas (d), (e) and (f) yield polynomial transmission times,

![]() $d_{\mathcal C}(0,x)= \|x\|^{\eta _0\pm o(1)}$

, where

$d_{\mathcal C}(0,x)= \|x\|^{\eta _0\pm o(1)}$

, where

![]() $\eta _0=\eta _\beta =d(\mu -(3-\tau )/\beta )$

on (d)

$\eta _0=\eta _\beta =d(\mu -(3-\tau )/\beta )$

on (d)

![]() $\eta _0=\eta _\alpha =d\mu (\alpha -2)/(\alpha -(\tau -1))$

on (e), and

$\eta _0=\eta _\alpha =d\mu (\alpha -2)/(\alpha -(\tau -1))$

on (e), and

![]() $\eta _0=1$

on (f). The bold lines indicate discontinuous phase transitions, while the other transitions are smooth.

$\eta _0=1$

on (f). The bold lines indicate discontinuous phase transitions, while the other transitions are smooth.

1.3 Results

In this paper, we focus on the sub-explosive parameter regime

since for

![]() $\mu < \mu _{\mathrm {expl}}$

we have shown in previous work [Reference Komjáthy, Lapinskas and Lengler55] that the model is explosive: the cost-distance of two vertices

$\mu < \mu _{\mathrm {expl}}$

we have shown in previous work [Reference Komjáthy, Lapinskas and Lengler55] that the model is explosive: the cost-distance of two vertices

![]() $x,y$

converges in distribution to an almost surely finite variable as

$x,y$

converges in distribution to an almost surely finite variable as

![]() $|x-y| \to \infty $

, conditioned on x and y being in the infinite component.Footnote

6

In other words, (1.7) restricts us to the nonexplosive phase. The following two quantities define the boundaries of the new phases:

$|x-y| \to \infty $

, conditioned on x and y being in the infinite component.Footnote

6

In other words, (1.7) restricts us to the nonexplosive phase. The following two quantities define the boundaries of the new phases:

where we defineFootnote

7

![]() $\mu _{\mathrm {pol},\alpha }=\mu _{\mathrm {pol}, \alpha }(d, \tau , \alpha ):=\tfrac {1}{d}+\tfrac {3-\tau }{d(\alpha -2)}=\tfrac {\alpha -(\tau -1)}{d(\alpha -2)}$

and

$\mu _{\mathrm {pol},\alpha }=\mu _{\mathrm {pol}, \alpha }(d, \tau , \alpha ):=\tfrac {1}{d}+\tfrac {3-\tau }{d(\alpha -2)}=\tfrac {\alpha -(\tau -1)}{d(\alpha -2)}$

and

![]() $\mu _{\mathrm {pol}, \beta }=\mu _{\mathrm {pol}, \beta }(d, \tau , \beta ):=\tfrac {1}{d}+\tfrac {3-\tau }{\beta }$

. We also define two growth exponents. If

$\mu _{\mathrm {pol}, \beta }=\mu _{\mathrm {pol}, \beta }(d, \tau , \beta ):=\tfrac {1}{d}+\tfrac {3-\tau }{\beta }$

. We also define two growth exponents. If

![]() $\alpha \in (1,2)$

or

$\alpha \in (1,2)$

or

![]() $\mu \in (\mu _{\mathrm {expl}}, \mu _{\log })$

, we define

$\mu \in (\mu _{\mathrm {expl}}, \mu _{\log })$

, we define

with

![]() $\Delta _\alpha =\Delta _\alpha (\alpha ):=1/(1-\log _2\alpha )$

and

$\Delta _\alpha =\Delta _\alpha (\alpha ):=1/(1-\log _2\alpha )$

and

![]() $\Delta _\beta =\Delta _\beta (\tau , \mu , \beta )=1/(1-\log _2(\tau -1+\mu \beta ))$

.

$\Delta _\beta =\Delta _\beta (\tau , \mu , \beta )=1/(1-\log _2(\tau -1+\mu \beta ))$

.

![]() $\Delta _0>1$

follows since when

$\Delta _0>1$

follows since when

![]() $\alpha \in (1,2)$

then

$\alpha \in (1,2)$

then

![]() $\Delta _\alpha>1$

, while when

$\Delta _\alpha>1$

, while when

![]() $\mu \in ( \mu _{\mathrm {expl}}, \mu _{\log })$

then

$\mu \in ( \mu _{\mathrm {expl}}, \mu _{\log })$

then

![]() $\tau -1+\mu \beta>\tfrac {\tau +1}{2} >1$

and also

$\tau -1+\mu \beta>\tfrac {\tau +1}{2} >1$

and also

![]() $\tau -1+\mu \beta <2$

, so

$\tau -1+\mu \beta <2$

, so

![]() $\log _2(\tau -1+\mu \beta )$

is positive but less than

$\log _2(\tau -1+\mu \beta )$

is positive but less than

![]() $1$

. If both

$1$

. If both

![]() $\alpha>2$

and

$\alpha>2$

and

![]() $\mu> \mu _{\log }$

, we define

$\mu> \mu _{\log }$

, we define

$$ \begin{align} \eta_0 := \eta_0(\alpha,\beta,\mu,\tau) := \begin{cases} 1 & \text{ if } \mu>\mu_{\mathrm{pol}},\\ \min\left\{d(\mu-\mu_{\log}), \mu/\mu_{\mathrm{pol},\alpha}\right\} & \text{ if } \mu\le\mu_{\mathrm{pol}}, \end{cases} \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \eta_0 := \eta_0(\alpha,\beta,\mu,\tau) := \begin{cases} 1 & \text{ if } \mu>\mu_{\mathrm{pol}},\\ \min\left\{d(\mu-\mu_{\log}), \mu/\mu_{\mathrm{pol},\alpha}\right\} & \text{ if } \mu\le\mu_{\mathrm{pol}}, \end{cases} \end{align} $$

and note that

![]() $\eta _0>0$

for all

$\eta _0>0$

for all

![]() $\mu>\mu _{\log }$

, and

$\mu>\mu _{\log }$

, and

![]() $\eta _0<1$

exactly when

$\eta _0<1$

exactly when

![]() $\mu < \mu _{\mathrm {pol}}$

by (1.8). We often write

$\mu < \mu _{\mathrm {pol}}$

by (1.8). We often write

$$ \begin{align} \begin{aligned} \eta_\beta&=\eta_\beta(d, \tau, \mu, \beta):=d(\mu-\mu_{\log})=d(\mu-(3-\tau)/\beta),\\ \eta_\alpha&=\eta_\alpha(d, \tau, \mu, \alpha):=\mu/\mu_{\mathrm{pol},\alpha} = \frac{\mu d(\alpha-2)}{\alpha-(\tau-1)}. \end{aligned} \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \begin{aligned} \eta_\beta&=\eta_\beta(d, \tau, \mu, \beta):=d(\mu-\mu_{\log})=d(\mu-(3-\tau)/\beta),\\ \eta_\alpha&=\eta_\alpha(d, \tau, \mu, \alpha):=\mu/\mu_{\mathrm{pol},\alpha} = \frac{\mu d(\alpha-2)}{\alpha-(\tau-1)}. \end{aligned} \end{align} $$

The formulas can be naturally extended by taking limits and hold also when

![]() $\alpha = \infty $

or

$\alpha = \infty $

or

![]() $\beta =\infty $

, which we elaborate in Section 1.3.1 below.

$\beta =\infty $

, which we elaborate in Section 1.3.1 below.

We first formulate the main results for the infinite models IGIRG and SFP. We write

![]() $0\leftrightarrow x$

for the event that there is at least one path of edges in the graph between vertices

$0\leftrightarrow x$

for the event that there is at least one path of edges in the graph between vertices

![]() $0,x$

. Whenever

$0,x$

. Whenever

![]() $\tau \in (2,3)$

, these models have a unique infinite connected component with constant density, hence the event

$\tau \in (2,3)$

, these models have a unique infinite connected component with constant density, hence the event

![]() $0\leftrightarrow x$

occurs with (uniformly) positive probability given that

$0\leftrightarrow x$

occurs with (uniformly) positive probability given that

![]() $0,x$

are part of the vertex set [Reference Bringmann, Keusch and Lengler18, Reference Deijfen, van der Hofstad and Hooghiemstra26, Reference Komjáthy, Lapinskas and Lengler55, Reference Fountoulakis and Müller33]. For SFP, the vertex set is deterministic and thus

$0,x$

are part of the vertex set [Reference Bringmann, Keusch and Lengler18, Reference Deijfen, van der Hofstad and Hooghiemstra26, Reference Komjáthy, Lapinskas and Lengler55, Reference Fountoulakis and Müller33]. For SFP, the vertex set is deterministic and thus

![]() $0,x\in \mathcal {V}$

holds under the assumption that

$0,x\in \mathcal {V}$

holds under the assumption that

![]() $x\in \mathbb {Z}^d$

. For IGIRG, we need to condition on

$x\in \mathbb {Z}^d$

. For IGIRG, we need to condition on

![]() $0,x\in \mathcal {V}$

. Formally, this is achieved by switching to the Palm measure of the Poisson point process. The Palm measure of a Poisson point process is again a unit intensity PPP on

$0,x\in \mathcal {V}$

. Formally, this is achieved by switching to the Palm measure of the Poisson point process. The Palm measure of a Poisson point process is again a unit intensity PPP on

![]() $\mathbb {R}^d$

with the vertices

$\mathbb {R}^d$

with the vertices

![]() $0,x$

added to the vertex set, and with all vertex-weights, edges, and edge-costs still drawn by the Equations (1.6), (1.5) and (1.2) respectively, see also the book [Reference Last and Penrose61]. Later in Remark 1.9 we will also give a conditional version of the following theorem given the weighted vertex set.

$0,x$

added to the vertex set, and with all vertex-weights, edges, and edge-costs still drawn by the Equations (1.6), (1.5) and (1.2) respectively, see also the book [Reference Last and Penrose61]. Later in Remark 1.9 we will also give a conditional version of the following theorem given the weighted vertex set.

Theorem 1.4. Consider

![]() $1$

-FPP in Definition 1.1 on the graphs IGIRG or SFP of Definition 1.3 satisfying the assumptions given in (1.6)–(1.3) with

$1$

-FPP in Definition 1.1 on the graphs IGIRG or SFP of Definition 1.3 satisfying the assumptions given in (1.6)–(1.3) with

![]() $\tau \in (2,3), \alpha>1, d\ge 1, \mu >0$

. Assume either

$\tau \in (2,3), \alpha>1, d\ge 1, \mu >0$

. Assume either

![]() $\alpha \in (1,2)$

or

$\alpha \in (1,2)$

or

![]() $\mu \in (\mu _{\mathrm {expl}},\mu _{\log })$

or both hold. For SFP, assume

$\mu \in (\mu _{\mathrm {expl}},\mu _{\log })$

or both hold. For SFP, assume

![]() $x\in \mathbb {Z}^d$

. Then for any

$x\in \mathbb {Z}^d$

. Then for any

![]() $\varepsilon>0$

,

$\varepsilon>0$

,

For IGIRG, due to the conditioning

![]() $0,x\in \mathcal {V}$

,

$0,x\in \mathcal {V}$

,

![]() $\mathbb {P}$

is the Palm version of the annealed probability measure taken over edges, edge-costs, vertex-weights and -locations.

$\mathbb {P}$

is the Palm version of the annealed probability measure taken over edges, edge-costs, vertex-weights and -locations.

The result of Theorem 1.4 is also valid when

![]() $\mu < \mu _{\mathrm {expl}}$

, however, then the model is explosive [Reference Komjáthy, Lapinskas and Lengler55, Theorem 1.1], and the bound is not sharp. With the restriction

$\mu < \mu _{\mathrm {expl}}$

, however, then the model is explosive [Reference Komjáthy, Lapinskas and Lengler55, Theorem 1.1], and the bound is not sharp. With the restriction

![]() $\mu>\mu _{\mathrm {expl}}$

, we conjecture that Theorem 1.4 is actually sharp, that is, that a corresponding lower bound with exponent

$\mu>\mu _{\mathrm {expl}}$

, we conjecture that Theorem 1.4 is actually sharp, that is, that a corresponding lower bound with exponent

![]() $\Delta _0 - \varepsilon $

also holds. The exponent

$\Delta _0 - \varepsilon $

also holds. The exponent

![]() $\Delta _0>1$

intuitively corresponds to stretched exponential ball-growth, where the number of vertices in cost-distance at most r scales as

$\Delta _0>1$

intuitively corresponds to stretched exponential ball-growth, where the number of vertices in cost-distance at most r scales as

![]() $\exp (r^{1/\Delta _0})$

. Trapman in [Reference Trapman74] showed that strictly exponential ball growth, that is,

$\exp (r^{1/\Delta _0})$

. Trapman in [Reference Trapman74] showed that strictly exponential ball growth, that is,

![]() $\Delta _0=1$

, is possible for long-range percolation when

$\Delta _0=1$

, is possible for long-range percolation when

![]() $\alpha =1$

under additional constraints. This is consistent with our formula for

$\alpha =1$

under additional constraints. This is consistent with our formula for

![]() $\Delta _0$

, since

$\Delta _0$

, since

![]() $\Delta _0 \to 1$

as

$\Delta _0 \to 1$

as

![]() $\alpha \to 1$

. Related is the work [Reference Lakis, Lengler, Petrova and Schiller60] that treats polylogarithmic graph distances and classical FPP transmission times in the same model class but in a different parameter regime (finite variance degrees, that is,

$\alpha \to 1$

. Related is the work [Reference Lakis, Lengler, Petrova and Schiller60] that treats polylogarithmic graph distances and classical FPP transmission times in the same model class but in a different parameter regime (finite variance degrees, that is,

![]() $\tau>3$

), however the proof techniques do not extend to infinite variance degree underlying graphs and/or to 1-FPP. We leave the lower bound in this phase for future work.

$\tau>3$

), however the proof techniques do not extend to infinite variance degree underlying graphs and/or to 1-FPP. We leave the lower bound in this phase for future work.

Remark 1.8.

Structure of near-optimal paths in the polylog phase. The proof reveals two different types of paths with polylogarithmic cost-distances present in the graph. When

![]() $\alpha <2$

, randomly occurring long edges on low-weight vertices cause the existence of paths of cost at most

$\alpha <2$

, randomly occurring long edges on low-weight vertices cause the existence of paths of cost at most

![]() $(\log |x|)^{\Delta _\alpha +o(1)}$

with

$(\log |x|)^{\Delta _\alpha +o(1)}$

with

![]() $\Delta _\alpha =1/(1-\log _2(\alpha ))$

. The closest long edge of order

$\Delta _\alpha =1/(1-\log _2(\alpha ))$

. The closest long edge of order

![]() $|x|$

lands at distance

$|x|$

lands at distance

![]() $|x|^{\alpha /2}$

from

$|x|^{\alpha /2}$

from

![]() $0$

and x respectively, resulting in a polylog exponent of

$0$

and x respectively, resulting in a polylog exponent of

![]() $\Delta _\alpha $

after iterating. When

$\Delta _\alpha $

after iterating. When

![]() $\mu <\mu _{\log }$

, there are also paths using a cheap yet long edge (of order

$\mu <\mu _{\log }$

, there are also paths using a cheap yet long edge (of order

![]() $|x|$

) between two high-weight vertices (weight roughly

$|x|$

) between two high-weight vertices (weight roughly

![]() $|x|^{d/2}$

) that lie within distance

$|x|^{d/2}$

) that lie within distance

![]() $|x|^{(\tau -1+\mu \beta )/2+o(1)}$

from

$|x|^{(\tau -1+\mu \beta )/2+o(1)}$

from

![]() $0$

and x respectively, and these cause the existence of paths of cost at most

$0$

and x respectively, and these cause the existence of paths of cost at most

![]() $(\log |x|)^{\Delta _\beta +o(1)}$

with

$(\log |x|)^{\Delta _\beta +o(1)}$

with

![]() $\Delta _\beta =1/(1-\log _2(\tau -1+\mu \beta ))$

.

$\Delta _\beta =1/(1-\log _2(\tau -1+\mu \beta ))$

.

![]() $\Delta _\beta $

is the outcome of an optimisation: we minimise the distance between the high-weight vertices to

$\Delta _\beta $

is the outcome of an optimisation: we minimise the distance between the high-weight vertices to

![]() $0$

and x, while maintaining that an edge with constant cost exists between them. The minimal distance possible is of order

$0$

and x, while maintaining that an edge with constant cost exists between them. The minimal distance possible is of order

![]() $|x|^{(\tau -1+ \mu \beta )/2+o(1)}$

: the tail exponent

$|x|^{(\tau -1+ \mu \beta )/2+o(1)}$

: the tail exponent

![]() $\tau -1$

of the weight distribution (1.6), and

$\tau -1$

of the weight distribution (1.6), and

![]() $\mu \beta $

, the penalty exponent in (1.2) times the behaviour of the cdf of L in (1.3) both play a role.

$\mu \beta $

, the penalty exponent in (1.2) times the behaviour of the cdf of L in (1.3) both play a role.

When we increase

![]() $\mu $

above

$\mu $

above

![]() $\mu _{\log }$

and

$\mu _{\log }$

and

![]() $\alpha $

above

$\alpha $

above

![]() $2$

, we enter a new universality class and cost distances become polynomial:

$2$

, we enter a new universality class and cost distances become polynomial:

Theorem 1.6. Consider

![]() $1$

-FPP in Definition 1.1 on the graphs IGIRG or SFP of Definition 1.3 satisfying the assumptions given in (1.6)–(1.3) with

$1$

-FPP in Definition 1.1 on the graphs IGIRG or SFP of Definition 1.3 satisfying the assumptions given in (1.6)–(1.3) with

![]() $\tau \in (2,3),d\ge 1$

. When

$\tau \in (2,3),d\ge 1$

. When

![]() $\alpha>2$

and

$\alpha>2$

and

![]() $\mu> \mu _{\log }$

both hold, then for any

$\mu> \mu _{\log }$

both hold, then for any

![]() $\varepsilon>0$

,

$\varepsilon>0$

,

Here

![]() $\mathbb {P}$

is the annealed probability measure taken over edges, edge-costs, vertex-weights and -locations.

$\mathbb {P}$

is the annealed probability measure taken over edges, edge-costs, vertex-weights and -locations.

In the accompanying [Reference Komjáthy, Lapinskas, Lengler and Schaller56] we prove the corresponding lower bound, which implies:

Corollary 1.7 (Polynomial Regime).

Consider

![]() $1$

-FPP in Definition 1.1 on the graphs IGIRG or SFP satisfying the assumptions given in (1.6)–(1.3) with

$1$

-FPP in Definition 1.1 on the graphs IGIRG or SFP satisfying the assumptions given in (1.6)–(1.3) with

![]() $\tau \in (2,3), d\ge 1$

. When

$\tau \in (2,3), d\ge 1$

. When

![]() $\alpha>2$

and

$\alpha>2$

and

![]() $\mu> \mu _{\mathrm {log}}$

both hold, then for any

$\mu> \mu _{\mathrm {log}}$

both hold, then for any

![]() $\varepsilon>0$

,

$\varepsilon>0$

,

Corollary 1.7 together with Theorem 1.4 implies that the phase transition is proper at

![]() $\mu _{\log }$

and at

$\mu _{\log }$

and at

![]() $\alpha =2$

: distances increase from at most polylogarithmic to polynomial. Moreover, when

$\alpha =2$

: distances increase from at most polylogarithmic to polynomial. Moreover, when

![]() $\mu> \mu _{\mathrm {pol}}$

, (i.e.,

$\mu> \mu _{\mathrm {pol}}$

, (i.e.,

![]() $\min (\eta _\alpha , \eta _\beta )>1$

), and the dimension

$\min (\eta _\alpha , \eta _\beta )>1$

), and the dimension

![]() $d\ge 2 $

, in [Reference Komjáthy, Lapinskas, Lengler and Schaller56] we also prove strictly linear cost-distances with both upper and lower bounds. This, together with Theorem 1.6, implies that there is another phase transition at

$d\ge 2 $

, in [Reference Komjáthy, Lapinskas, Lengler and Schaller56] we also prove strictly linear cost-distances with both upper and lower bounds. This, together with Theorem 1.6, implies that there is another phase transition at

![]() $\mu _{\mathrm {pol}}$

, from sublinear (

$\mu _{\mathrm {pol}}$

, from sublinear (

![]() $\eta _0 < 1$

) to linear (

$\eta _0 < 1$

) to linear (

![]() $\eta _0=1$

) cost-distances. See Table 2 for a summary. We find it remarkable that 1-FPP shows polynomial distances with exponent strictly less than one in a spread-out parameter regime

$\eta _0=1$

) cost-distances. See Table 2 for a summary. We find it remarkable that 1-FPP shows polynomial distances with exponent strictly less than one in a spread-out parameter regime

![]() $\mu \in (\mu _{\log }, \mu _{\mathrm {pol}})$

. This implies polynomial ball-growth faster than the dimension for 1-FPP, which is rare in spatial models, see Section 1.4.

$\mu \in (\mu _{\log }, \mu _{\mathrm {pol}})$

. This implies polynomial ball-growth faster than the dimension for 1-FPP, which is rare in spatial models, see Section 1.4.

Remark 1.6.

Structure of near-optimal paths in the polynomial phase. The proof reveals two different types of paths with polynomial cost-distances present in the graph. When

![]() $\mu \le \mu _{\mathrm {pol},\alpha }$

, there are a few very long edges (of order

$\mu \le \mu _{\mathrm {pol},\alpha }$

, there are a few very long edges (of order

![]() $|x|$

) with endpoints polynomially near

$|x|$

) with endpoints polynomially near

![]() $0$

and x, emanating from vertices with weight

$0$

and x, emanating from vertices with weight

![]() $|x|^{1/(2\mu _{\mathrm {pol}, \alpha })}$

, and these results in paths with cost at most

$|x|^{1/(2\mu _{\mathrm {pol}, \alpha })}$

, and these results in paths with cost at most

![]() $|x|^{\eta _\alpha +o(1)}$

(when (1.10) evaluates to

$|x|^{\eta _\alpha +o(1)}$

(when (1.10) evaluates to

![]() $\mu /\mu _{\mathrm {pol},\alpha }$

). Since there are only few such edges, the optimisation effect of choosing the one with smallest cost is negligible and

$\mu /\mu _{\mathrm {pol},\alpha }$

). Since there are only few such edges, the optimisation effect of choosing the one with smallest cost is negligible and

![]() $\beta $

does not enter the formula. Further, when

$\beta $

does not enter the formula. Further, when

![]() $\mu \le \mu _{\mathrm {pol},\beta }$

, there are many long edges (of order

$\mu \le \mu _{\mathrm {pol},\beta }$

, there are many long edges (of order

![]() $|x|$

) with respective endpoints polynomially near