Introduction

A large number of empirical studies (see for overviews Naurin et al. Reference Naurin, Royed and Thomson2019a; Thomson et al. Reference Thomson, Royed, Naurin, Artés, Costello, Ennser-Jedenastik, Ferguson, Kostadinova, Moury, Pétry and Praprotnik2017) have found that politicians take the promises they make to voters seriously. Nevertheless, with a few notable, recent exceptions (Born et al. Reference Born, Van Eck and Johannesson2018; Corazzini et al. Reference Corazzini, Kube, Maréchal and Nicolò2014; Elinder et al. Reference Elinder, Jordahl and Poutvaara2015; Matthieβ, Reference Matthieβ2020; Naurin et al. Reference Naurin, Soroka and Markwat2019b), the fulfilment of election pledges is still rarely used as a yardstick in academic work to track perceptions of government performance. Consequently, despite the central role allocated to election pledges and their fulfilment by classic work on representative democracy, little is known about the way in which voters hold their governments accountable based on the extent to which these governments fulfil or break their election pledges.

The most important recent finding in this literature is that the reward–punishment mechanism proposed in classical theoretical contributions on this topic (e.g. Downs Reference Downs1957; Fiorina Reference Fiorina1981; Ferejohn Reference Ferejohn1986) may take a more complex form in political reality. Indeed, Naurin et al. (Reference Naurin, Soroka and Markwat2019b) found that while voters punish pledge-breaking parties as anticipated, voters may also punish pledge-fulfilling parties for fulfilling pledges of policy action they disagree with. This means that rewards and punishments for pledge performance are conditional, at the very least, upon pledge content.

Additionally, common sense dictates that these rewards and punishments are also dependent on the context of pledges. There can be eased circumstances for voters to accept broken election pledges from their governments—a similar notion to the reasoning behind the concept of ‘benchmarking’ in the wider retrospective voting literature (e.g. Arel-Bundock et al. Reference Arel-Bundock, Blais and Dassonneville2019; see Healy and Malhotra Reference Healy and Malhotra2013). In times of recession and budget cuts, for instance, governments may be less pressed to deliver the policy output they pledged earlier, and parties in coalition and/or minority governments may find greater understanding among voters for alienating pledged policy action, than parties in single-party and/or majority governments.

Thus, at least in theory, the expectations of voters that election pledges will be fulfilled may matter a great deal to the way in which voters use fulfilled and broken pledges to hold governments accountable. From the previous research, it is known that similar prior expectations are a vital element of understanding evaluations of consumer products and services in marketing research, as well as public goods and services in public administration research (see for an overview Morgeson Reference Morgeson2013). With a few notable exceptions (Jenkins-Smith et al. Reference Jenkins-Smith, Silva and Waterman2005; Kimball and Patterson Reference Kimball and Patterson1997; Malhotra and Margalit Reference Malhotra and Margalit2014; Seyd Reference Seyd2015; Waterman et al. Reference Waterman, Jenkins-Smith and Silva1999; Reference Waterman, Jenkins-Smith and Silva2014), however, the role of prior performance expectations in voters’ evaluations of government performance remains largely understudied.

The contribution of this study is in this context threefold. Firstly, the study formulates a theoretical framework for the role of performance expectations in the evaluations of fulfilled and broken election pledges—based on the findings pertaining to similar mechanisms in other academic disciplines. Secondly, the study describes the design of an experimental manipulation that significantly raises and lowers the expectations of voters of the fulfilment of the election pledges they are confronted with. And finally, the study empirically tests the formulated theoretical framework to determine to what extent voter evaluations of pledge fulfilment are dependent on the prior fulfilment expectations of the voters.Footnote 1 Conclusions are drawn about the extent to which the psychology of evaluating pledge fulfilment indeed resembles that of evaluating consumer goods/services, and public goods/services—or whether evaluating election pledges is part of a wider, more complex political reality with a distinct set of underlying explanations.

Expectations of pledge fulfilment

This section first provides a brief elaboration on expectations about pledge fulfilment in general, before formulating the central hypothesis of this study on the role of these expectations in voter evaluations of pledge fulfilment. Similar to Malhotra and Margalit (Reference Malhotra and Margalit2014) and Seyd (Reference Seyd2015), a political adaptation of the expectation–disconfirmation theory (ECT) is presented, hypothesizing that broken pledges have the strongest effect on voters if fulfilment expectations are high and that fulfilled pledges increase voter approval of government the most if these expectations are low. In other words, the central premise is that the highest rewards for fulfilled pledges are found when expectations are outperformed, and the most severe punishments for broken pledges are found when high expectations are disconfirmed.

The study of performance expectations often distinguishes between normative and anticipatory expectations. Normative expectations refer to the notion of how something should or is supposed to perform—usually stemming from some ideal (e.g. Seyd Reference Seyd2016) or norm that the performance can be measured against. For election pledges, this would entail the opinions of voters on whether political parties generally should fulfil their pledges, or not. Anticipatory expectations, on the other hand, refer to the perceived probability of a satisfactory performance, i.e. how something will or is anticipated to perform.

The focus here is on anticipatory pledge fulfilment expectations, referring to the perceived likelihood that a pledge will be fulfilled by its maker, the political party in question. There can be a number of causes of variance in such fulfilment expectations among voters. A related study (Markwat Reference Markwat, Andersson, Ohlsson, Oscarsson and Oskarson2017) found that anticipatory pledge fulfilment expectations vary from individual to individual, from pledge to pledge, and by the party that made them. Lindgren (2017) found that the wording of election pledges matters to voters’ expectations of their fulfilment, while Kolpinskaya et al. (Reference Kolpinskaya, Katz, Banducci, Stevens and Coan2020) found that the magnitude of electoral victories can impact voters’ performance expectations in general. Moreover, voters may be cynical about the credibility of politics in general, voters may have more confidence in one party than in others, (economic) circumstances may spark more cynicism/optimism regarding certain pledges, some pledges may be perceived to be easier/more difficult to fulfil, etc. What matters for this study, is what happens when the fulfilment expectations have already formed—i.e. what the effects are of (in)congruence between a voter’s fulfilment expectations, and the eventual political performance.

Despite the focus on anticipatory expectations, note that at least to a certain degree, the proposed mechanism that broken pledges lead to electoral punishments itself hinges upon an assessment of normative expectations. Indeed, the underlying assumption is that irrespective of content or context, voters want political parties to fulfil their pledges (see Schedler Reference Schedler1998). That this assumption is not always supported in practice is illustrated by the findings of Naurin et al. (Reference Naurin, Soroka and Markwat2019b), which show that certain voters may not want certain pledges fulfilled, not wanting the promised policy action to be taken. In addition, observational data collected for a related project (Markwat Reference Markwat, Andersson, Ohlsson, Oscarsson and Oskarson2017) showed that because different voters desire different types of representation (politicians as trustees vs. delegates, e.g. Fox and Shotts Reference Fox and Shotts2009)—while most voters asserting all pledges should be fulfilled, a substantial minority thinks politicians should decide which pledges they choose to fulfil. That said, generally voters appear to view broken election pledges as poor performance (see also Schedler Reference Schedler1998). Therewith, knowledge of how voters’ expectations of election pledge fulfilment on the one hand, and actual (lack of) fulfilment on the other can contribute to the general understanding of how voters hold political leaders to account.

Expectation confirmation theory

The level of congruence between voter expectations and political performance is where the expectation confirmation theory (ECT) comes in and could make an important contribution to electoral research. Introduced by Richard L. Oliver in the late 1970s to marketing research,Footnote 2, the basic mechanism of the expectation confirmation theory (ECT) has an elegant simplicity. In essence, it poses that a consumer’s evaluation of a product (and its supplier) is derived from subtracting the expected experience by the consumer, from the actual experience (Oliver Reference Oliver1977; Reference Oliver1980). This means that if a product performs well, low prior expectations render the perception of the experience more positive than high expectations. Similarly, if performance is poor, low prior expectations will cushion the blow—whereas high expectations lead to disappointment. Thus, a product outperforming expectation leads to the most positive evaluations, and a product failing to meet expectations leads to the most negative evaluations.

In the years following its introduction, this straightforward mechanism proved effective to explain consumer attitudes to commercial products and services, and their suppliers, in a number of studies (e.g. Cadotte et al. Reference Cadotte, Woodruff and Jenkins1987; Swan and Combs Reference Swan and Combs1976; Tse and Wilton Reference Tse and Wilton1988). Later, the common sense principles of the ECT were shown to extend beyond marketing research. Indeed, the interaction between expectations and performance proved applicable to evaluations of public goods and services as well, as shown in several public administration studiesFootnote 3 (e.g. Chandek and Porter Reference Chandek and Porter1998; James Reference James2009; see for an overview Morgeson Reference Morgeson2013). Among many other things, the ECT proved helpful in explaining evaluations of police services (Chandek and Porter Reference Chandek and Porter1998), garbage collection services, local government services (James Reference James2009), and federal government services (Morgeson Reference Morgeson2013).

Despite its successes and accepted usage in marketing, psychology, and even public administration, the ECT has found only seldom application in political science research. There are a few notable exceptions—two of which are highly relevant here. First, Malhotra and Margalit (Reference Malhotra and Margalit2014) designed a series of experiments to study the influence of disconfirmed performance expectations set by incumbents on voters’ evaluations of government policy outcomes. They concluded that disconfirmed expectations do cause more pronounced evaluations, but only if the government can be reasonably assumed to have had a certain level of authority over the policy outcome involved. Second, the work of Seyd (Reference Seyd2015, Reference Seyd2016) considered the effects of disconfirmed performance expectations on voters’ trust in government and political disappointment. The findings did not support a pivotal role for expectations in evaluations of government performance. It was concluded that if governments want to avoid electoral punishment they should perform better, instead of trying to lower voters’ expectations.

Thus, on the one hand, several studies found evidence of the importance of the ECT to the formation of political attitudes (Jenkins-Smith et al. Reference Jenkins-Smith, Silva and Waterman2005; Kimball and Patterson Reference Kimball and Patterson1997; Waterman et al. Reference Waterman, Jenkins-Smith and Silva1999, Reference Waterman, Jenkins-Smith and Silva2014). However, on the other hand, the findings of Seyd (Reference Seyd2015, Reference Seyd2016)Footnote 4 underline that it is not at all certain that the common sense principle of expectation disconfirmation applies to the relation between election pledge fulfilment and government performance evaluations. Moreover, it is unclear to what degree government performance evaluations based on the fulfilment or breaking of election pledges are comparable to evaluations of private goods and services, or even public goods and services. A substantial number of authors have, from various angles, addressed the question to which degree concepts from the disciplines of economics and marketing are applicable to political science questions. There seems to be a general consensus that marketing principles can be of assistance in understanding political phenomena (e.g. Durmaz and Direkçi Reference Durmaz and Direkçi2015; Schweidel and Bendle Reference Schweidel and Bendle2019); however, it is unclear to what degree this extends beyond the most comparable concepts such as personal branding and political marketing used in election campaigns. It is encouraging that other political scientists (e.g. Bøggild Reference Bøggild2020; Seyd Reference Seyd2015) have been able to identify elements in theories of political behaviour that justify applying ECT reasoning to the behaviour of voters. Also, it could be argued that election pledges present a rather clear-cut agreement between voters and political parties—if we get voted in, we will do this—and are in that particular sense perhaps less complex than certain other political concepts. However, it is also hard to envision that the evaluation of fulfilled and broken election pledges is as clear-cut as that of a good tasting can of beans or as a garbage truck that fails to show up on time. Therefore, it is important to acknowledge and consider the possibility that the ECT mechanism that appears so straightforward when considered in the context of the provision of services and products, is less applicable, or at least in a less obvious manner, to political behaviour, than it is in other contexts. In other words, this study provides insight into the specific psychology underlying responses of voters with higher and lower expectations to broken and fulfilled election pledges, using insights from other disciplines (in the form of the ECT) to assess to what degree political science can learn from others about the psychology behind performance evaluations and accountability processes, or whether political processes can only be explained by theoretical models that thoroughly reflect the unique complexity of political reality.

Hypotheses

In summary, the theoretical underpinnings of this study are as follows. Political parties make promises to their electorate regarding the actions they will or will not take once they are elected into office (election pledges). Some of these pledges will, and some will not be fulfilled. Borrowing from the retrospective voting literature (see Healy and Malhotra Reference Healy and Malhotra2013) and similar to Naurin et al. (Reference Naurin, Soroka and Markwat2019b), a reward-punishment hypothesis is proposed that asserts that voter approval of a government party decreases when this party breaks pledges (punishment), and that it increases when a party fulfils pledges (reward).Footnote 5 Based partly on insights from ECT work from various disciplines, and partly on common sense, the hypothesis is that rewards and punishments for fulfilled and broken election pledges are conditional upon the fulfilment expectations that a voter may have. Concretely, the presumption is that voters with high expectations of pledge fulfilment more likely show disappointment toward a government party that breaks its election pledges. In turn, this should lead to them expressing a lower approval of this party—i.e. administer more severe political punishment. Vice versa, low expectation voters should be more positively surprised by a party fulfilling its election pledges. This in turn should lead them to express higher levels of approval of this party—i.e. administer higher political reward.

The hypothesesFootnote 6 are as follows (see also Table 1):

Table 1 Summary of theoretical framework and hypotheses

H1

Approval of a government party that fulfils an election pledge increases more among voters with low fulfilment expectations than among voters with high fulfilment expectations (positive disconfirmation/outperformance hypothesis).

H2

Approval of a government party that breaks an election pledge decreases more among voters with high fulfilment expectations than among voters with low fulfilment expectations (negative disconfirmation/underperformance hypothesis).

Experimental design

This study tested its hypotheses in a survey experiment totalling 2465 respondents, conducted in wave 28 (December 2017) of the Citizen Panel of the Laboratory of Opinion Research (LORE) at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden. The net subsample size of the non-probability sample was 4082 with an AAPOR-RR5 of 58% and a net participation rate (NPR) of 60%. The sample was pre-stratified on age, sex, and education level (see Martinsson et al. Reference Martinsson, Andreasson, Markstedt and Lindgren2018). LORE is an organisation within the University of Gothenburg, devoted to conducting data collection through web questionnaires. Collection of data in collaboration with LORE is performed through a number of web panels, of which the Citizen Panel is the largest with more than 60,000 active respondents in Sweden.Footnote 7

The design of the experiment was pre-registered with EGAP in November 2017 under registration number [20171127AB]. See Section B of the supplementary materials for the full experiment text. The experiment was carried out in two steps. The first step, respectively, raised or lowered the respondents’ pledge fulfilment expectations, or not (control group). The second step, respectively, confirmed or disconfirmed the respondents’ manipulated fulfilment expectations, or not (control group). Thus, in total there were four treatment conditions, based on the hypotheses of this study (see Table 1), and a control group. All respondents were randomly assigned to any of these five experimental groups.Footnote 8

First, for all respondents, a pre-measure of the focal dependent variable (evaluation of the Social Democrats’ performance in government) was recorded through a survey instrument that separately measured the respondents’ opinion about the performance of both government parties (Social Democrats and Green Party), and the opposition parties (Alliance parties; Sweden Democrats; Left Party). Then, 40% of the respondents (groups 1&2; 988 respondents) received a treatment intended to raise their pledge fulfilment expectations, containing the following (correct) information: “Research shows that past Swedish governments in which the Social Democrats have participated have actually fulfilled the vast majority of their election promises.” Another 40% (groups 3&4; 967 respondents) received a treatment intended to lower their fulfilment expectations, containing the (also correct) information that: “Research shows that minority coalitions such as the current Swedish government (containing the Social Democrats) have difficulties fulfilling their election promises.” The remaining 20% in the control group received a null treatment utilising the same important key words: ‘research’, ‘promises’, and ‘Social Democrats’. They received information that: “Research on parties’ election promises is conducted in Sweden, for example on the extent to which the Social Democrats fulfil their promises.”

Immediately after these treatments, as a manipulation check, all respondents were asked: “How likely is it in your opinion that the Social Democrats will fulfil most of their election promises during the current government term?”—where 1 is “very unlikely” and 5 is “very likely”. This manipulation check was included to assess the efficacy of the expectation treatments designed for this experiment. It was also one of two measures taken to ascertain that the recorded effects were indeed caused by the manipulation of voter expectations. The other was that the expectations and pledge treatments were presented separately, in sequence. For fulfilment expectations, no pre-measure was included, as that would have primed the respondents on fulfilment expectations prior to them receiving the expectation manipulations. Due to the absence of an expectations pre-measure, the analysis of the manipulation check is between-subject, not within-subject.

In the third step, 40% of the respondents (groups 1&3; 977 respondents) were randomly assigned to a treatment informing them of election pledge fulfilment by the Social Democrats, with three examples of fulfilled pledges. This treatment was formulated as follows: “The Social Democrats have already fulfilled many of the promises they made before the 2014 election. They have for example improved unemployment benefits, improved railway maintenance, and reserved a third month of parental leave for each parent.”

The other 40% (groups 2&4; 978 respondents) were randomly assigned to a treatment informing the respondents of the Social Democrats’ breaking of election pledges, also including three examples. This treatment was formulated as follows: “The Social Democrats have already broken several of the promises they made before the 2014 election. They have for example not improved health care benefits, nationalised railway maintenance, nor created 32 000 trainee jobs for youngsters in the welfare sector.”

The remaining 20% in the control group received a null treatment text containing the same key words, but merely mentioning the making of election pledges by the Social Democrats, also with three examples. No mention was made of the pledges’ fulfilment status,Footnote 9 which was undecided at the time for all three examples. The null treatment was formulated as follows: “The Social Democrats have made a number of promises before the 2014 election. For example, they promised to make pre-school for six-year olds mandatory, to increase the number of female professors, and to give municipalities the right to veto the establishment of new private schools.”

Now, for group 1, the raised fulfilment expectations should have been positively confirmed; for group 2, negatively disconfirmed; for group 3, the lowered expectations positively disconfirmed, and for group 4, negatively confirmed. Immediately after the fulfilment treatments, all respondents received the central dependent variable question: “How well do you think that the Social Democrats have performed in government?”—where 1 is “very poorly” and 7 is “very well”. This evaluation of Social Democrat government performanceFootnote 10 is a repetition of the pre-measurement. The hypothesised confirmation and disconfirmation effects were measured on the difference between these two pre- and post-treatment evaluations.

To increase the external validity of the experiment, all information in all treatments was obtained from actual politics at the time of design. Concretely, this means that actual election pledges made by the Social Democrats prior to the Swedish parliamentary elections of 2014, and their actual fulfilment status at the time of the experiment (fulfilled, broken, or undecided—and thus not mentioned), were used. It is important to be aware that results of the experiment were obtained in one country, Sweden, and that this may have implications for the generalisability of the results. That said, Sweden has been one of the countries in which relatively many studies of election pledges have been conducted (e.g. Lindgren Reference Lindgren2022; Naurin et al. Reference Naurin, Soroka and Markwat2019b)—and of which it is known that comparable results were obtained there to studies conducted in other, comparable contexts (see for an overview Naurin et al. Reference Naurin, Royed and Thomson2019a). In addition, the topic of this study pertains to a quite universal psychological mechanism (see also, e.g. Mullinix et al. Reference Mullinix, Leeper, Druckman and Freese2015) that, given its wide application across academic disciplines, and national contexts, should be applicable in most contexts.

The choice to work with factual information from real-life politics came at a cost of the experiment’s internal validity. Using real-world election pledges, pledge content cannot be kept stable across conditions. Indeed, the same pledges cannot be both broken and fulfilled. To counteract this, sets of three fulfilled and three broken example pledges were identified, with varying saliency, and from different policy areas, and used as examples. The use of multiple pledges as examples instead of one also decreased the risk of an undue influence on the experimental effects posed by an incongruence between the (dis)confirmation of manipulated general expectations—about all pledges—with specific performance information—about one pledge.

Vice versa, a choice that benefited the experiment’s internal validity came at a cost of its external validity. All respondents evaluated the same government party, at the same time, in the same country. However, if effects can be established in respondents by merely providing them with different (though correct) performance information about the same government—it would be reasonable to assume that the effects should be even greater in magnitude if there would be actual variation in the overall pledge fulfilment of the government under evaluation, for example if the respondents would evaluate concurrent government parties in different countries or different time periods (see also Markwat Reference Markwat2021; compare Thomson and Brandenburg Reference Thomson and Brandenburg2019). See Section B of the supplementary materials for all exact treatment formulations; for the research results underlying the treatments, see Naurin (Reference Naurin2014); Thomson et al. (Reference Thomson, Royed, Naurin, Artés, Costello, Ennser-Jedenastik, Ferguson, Kostadinova, Moury, Pétry and Praprotnik2017).

Results

Efficacy of expectations manipulation

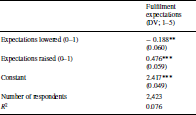

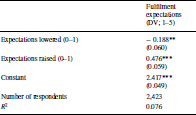

The experimental manipulations managed to effectively raise and lower respondents’ fulfilment expectations of election pledges. This is important to establish because of the focus on confirmation and disconfirmation of manipulated voter expectations of pledge fulfilment in this study. To that end, Table 2 presents the results of an OLS regression analysis conducted to compare how expectations were affected in the different treatment conditions. These results show that respondents in the “expectations lowered” condition expressed on average almost 0.2 (8%) lower fulfilment expectations in the manipulation check than respondents in the control group, who in turn expressed on average almost 0.5 (20%) lower fulfilment expectations than respondents in the “expectations raised” condition. The mean fulfilment expectations reported by the control group were 2.42, with 20% reporting high and 58% low expectations, respectively. This is in line with the earlier use of this instrument (Markwat Reference Markwat, Andersson, Ohlsson, Oscarsson and Oskarson2017), implying that the designed null treatment did not alter expectations, as intended. The mean expectations reported by respondents in the expectation raising condition were 2.89, (35% high; 39% low). Mean expectations for expectation lowering were 2.23 (13% high; 65% low). Since no pre-measure was available for fulfilment expectations, it is unknown for individual respondents whether their expectations were manipulated or not. Therefore, all results are on an intention-to-treat (ITT) basis.

Table 2 OLS regression coefficients manipulation check expectations

Standard errors in parentheses. *; **; *** = p < 0.05; 0.01; 0.001

As was found in earlier accounts (Markwat Reference Markwat, Andersson, Ohlsson, Oscarsson and Oskarson2017), respondents’ party preferences have a strong, direct effect on their fulfilment expectations, but it does not seem to affect the manipulation of these expectations. In other words, Social Democrat voters across conditions report considerably higher fulfilment expectations (3.50) in response to the manipulation check than do voters for all other parties (2.32)—but Social Democrat voters in the expectation raising condition also report significantly higher expectations (3.88) than those in the expectation lowering condition (3.13). That also applies to the other voters in the expectation raising and lowering conditions (2.65 versus 2.03, respectively). The comparable mean differences between the expectation raising and lowering conditions observed for Social Democrat (0.55) and other voters (0.62) indicate that partisanship did not significantly interact with the expectations treatments used in this study. Similar results were obtained for self-reported left–right ideology, and political interest of the respondents. Replication of the main experimental results with analyses using not the treatment condition, but the respondents’ reported fulfilment expectations as independent variable, did not yield meaningfully different results—indicating that priming and social desirability effects are not a plausible explanation of the found confirmation effects. All these results come from OLS regression analyses. Sections C and D of the supplementary materials report on analyses of the degree to which the party preference and self-reported ideology of the individual respondents affect their change in Social Democrat approval for the different treatment conditions.

Expectation disconfirmation effects

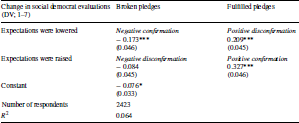

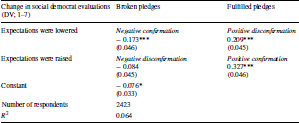

Table 3 presents the main experimental results. The contents represent OLS regression analyses of the average change in respondents’ evaluations of Social Democrat performance, and the recorded effects of the positive and negative confirmation and disconfirmation treatments on this change. All these results are on an ITT basis.

Table 3 Confirmation and disconfirmation effects on evaluations of Social Democrat performance in government (OLS regression coefficients)

Reference category is the control group (respondents in this group only received two neutral null treatments instead of the treatments designed to raise/lower expectations, and confirm/disconfirm expectations that respondents in the other groups received). The conducted analysis is an Ordinary Least Squares regression analysis with treatment group as categorical independent variable. Standard errors in parentheses. *; **; *** = p < 0.05; 0.01; 0.001

Contrary to the hypotheses of this study, the strongest average effects are observed for both confirmation conditions. If the hypotheses of this study would have held up empirically, the coefficients presented in Table 3 should have been most sizable in magnitude for the disconfirmation conditions. Indeed, it was hypothesised that (H1) approval of the Social Democrats fulfilling pledges would increase more among the group with lowered fulfilment expectations (positive disconfirmation), than among the group with raised fulfilment expectations (positive confirmation) and that (H2) approval of the Social Democrats breaking pledges would decrease more among the group with raised fulfilment expectations (negative disconfirmation), than among the group with lowered fulfilment expectations (negative confirmation). For both hypotheses, the found coefficients point in the exact opposite direction. The average increase in Social Democrat approval found for the group with raised expectations and fulfilled pledges (positive confirmation) is more than 50% higher at 0.33 than for the group with lowered expectations (positive disconfirmation) at 0.21. Similarly, the average decrease in Social Democrat approval found for the group with lowered expectations and broken pledges (negative confirmation) is more than double that found for the group with raised expectations (negative disconfirmation) at − 0.17 versus − 0.08, respectively.

Approval in the control group decreased by 0.08, on average. In the positive confirmation and disconfirmation conditions, the evaluations of 31% and 23% of the respondents improved, respectively. In the negative confirmation and disconfirmation conditions, the evaluations of 33% and 25% of the respondents decreased, respectively.

Thus, as evidenced by the fact that the average within-subject effect recorded in the negative confirmation condition is considerably stronger than the (non-significant) effect for the negative disconfirmation condition, and the effect recorded for the positive confirmation condition is considerably stronger than that recorded for the positive disconfirmation condition,Footnote 11 the hypotheses of this study do not hold. Instead, the found results are exactly opposite of those hypothesised. The vast majority (58–64%) of all the groups did not alter their evaluations. Furthermore, as can be seen in sections C and D of the supplementary materials, potential interactions with partisanship and self-reported ideology did not impose significantly on the effects of the experimental treatments.

Discussion

This study formulated a theoretical framework for the role of performance expectations in the evaluations of fulfilled and broken election pledges, and set out to put this framework to an empirical test. First, by designing experimental treatments to alter voters’ expectations of election pledge fulfilment. Second, by empirically assessing to what extent the effects of broken and fulfilled election pledges on voters’ evaluations of government performance are dependent on these manipulated fulfilment expectations. The study manipulated voter expectations of election pledge fulfilment, and the extent to which this proved possible with minimal stimuli is quite considerable if taking into account the perception that voters’ attitudes are more or less immovable—the dominant paradigm for example in the literature on motivated reasoning (e.g. Leeper and Slothuus Reference Leeper and Slothuus2014).

In line with basic theoretical expectations of the relationship between pledge fulfilment and accountability processes (see, e.g. the literature review of Naurin et al. Reference Naurin, Soroka and Markwat2019b) the found results indicated that overall, voters confronted with pledge fulfilment provided more positive evaluations of government performance, while (to a somewhat lesser extent) respondents confronted with information about broken election pledges provided more negative evaluations of government performance. However, the found disconfirmation results disproved the hypotheses of this study. The findings underlined stronger confirmation than disconfirmation effects, both for the positive and for the negative conditions. In other words, voters appear to provide higher approval for a government party fulfilling its pledges as expected, than for a government party that outperforms expectations. Similarly, they administer stronger punishment for a government party breaking pledges as expected, than for a government party underperforming on its promises. This suggests the presence of a confirmation, rather than a disconfirmation bias.

Various reasons can be thought of to explain why Malhotra and Margalit (Reference Malhotra and Margalit2014) did find expectation disconfirmation effects, and Seyd (Reference Seyd2015) and this study did not. First of all, the context, type of expectations, and focal dependent variables vary across these three studies. Like in the analysis of observational data by Seyd (Reference Seyd2015), in this experimental study the respondents had to connect the expectation to its confirmation themselves—they were not told explicitly their expectations were confirmed or disconfirmed. In addition, Malhotra and Margalit (Reference Malhotra and Margalit2014) used fictional scenarios, whereas this study and that of Seyd (Reference Seyd2015) had a real-world nature. It is possible that the disconfirmation effects prescribed by the ECT can be found for non-existing politics, but not in the real world which is burdened by voters’ biases and prior beliefs, which also affect the context in which expectations are formed and processed (Markwat Reference Markwat, Andersson, Ohlsson, Oscarsson and Oskarson2017). Another possibility is that the psychological mechanism proposed by the ECT plays a role only when politicians themselves are the source of the (manipulated) expectations, as they can be held responsible and accountable for creating these expectations in vain—as suggested by Malhotra and Margalit (Reference Malhotra and Margalit2014). That said, few would claim that leaders are not the ones ultimately responsible for creating the expectation that the policy they promised to implement will in fact be implemented, as well as for in fact attempting to implement that policy. Moreover, a recent large international study conducted by Matthieβ (Reference Matthieβ2020) also provided no support for clarity of responsibility effects in the evaluation of pledge performance.

Arguably the most plausible explanation for the found effects is that the relation between election pledge fulfilment and evaluations of government performance is subject to a confirmation bias, rather than the hypothesised disconfirmation bias well-documented in the literature on evaluations of private and public goods and services. The conclusion, then, would be that attitudes about pledge fulfilment and government performance are formed in a way that is more similar to the way in which other political attitudes are formed—for which a confirmation bias has been rather well-established (see for an overview Knobloch-Westerwick Reference Knobloch-Westerwick2015).

A confirmation bias entails that voters respond more strongly to information that aligns with their existing beliefs—here induced by the expectations manipulations. Indeed, for the set-up of this study, this would imply that voters are less inclined to accept and respond to messages of poor and good performance if these messages contradict their prior expectations of this performance. This directly opposes what the ECT would suggest—and the experimental results support this way of reasoning. Indeed, respondents with raised expectations responded more mildly to broken pledges than those with lowered expectations and those with lowered expectations responded more hesitantly to fulfilled pledges than those with raised expectations. While it is the task of future research to establish the specifics of this confirmation bias and its extension beyond this case, its presence can help to explain why the treatment designed to raise expectations was considerably more successful than that designed to lower expectations in this study. Indeed, it is well established that voters generally have a low esteem of the extent to which political parties (try to) fulfil their election pledges (Naurin Reference Naurin2011). In combination with the negativity bias often found present in media reports on politics, as well as in voters themselves (Naurin et al. Reference Naurin, Soroka and Markwat2019b; Thomson Reference Thomson2011; see for an overview Soroka Reference Soroka2014), a confirmation bias could provide at least a partial explanation of why voter perceptions of pledge fulfilment remain so negative, even if most political parties across the globe have been shown to take their promises very seriously (Naurin et al. Reference Naurin, Royed and Thomson2019a; Thomson et al. Reference Thomson, Royed, Naurin, Artés, Costello, Ennser-Jedenastik, Ferguson, Kostadinova, Moury, Pétry and Praprotnik2017).

In any case, the implications of these findings for research on election pledge fulfilment are that fulfilment expectations—which widely vary between individuals, pledges, and parties that made them (Markwat Reference Markwat, Andersson, Ohlsson, Oscarsson and Oskarson2017)—can be manipulated and that voters can administer both rewards and punishments to government parties for fulfilling and breaking the promises they made to the electorate. However, while parties may have the possibility to raise and lower the expectations about their performance, it seems unlikely that they will benefit from lowering expectations to gain more approval from the voters.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Gothenburg.