1. Introduction

Transient radio emission is a signature of some of the most energetic and interesting events in our Universe: from stellar explosions (Weiler et al. Reference Weiler, Panagia, Montes and Sramek2002) and compact object mergers (Hallinan et al. Reference Hallinan2017) to tidal disruption and accretion around supermassive black holes (Zauderer et al. Reference Zauderer2011). These dynamic events happen in extreme physical conditions and hence let us test fundamental physics such as mechanisms for magnetic field generation, particle acceleration, the strong-field gravity regime (Kramer et al. Reference Kramer2021) and the cosmological star formation history (Tanvir et al. Reference Tanvir2009; Chandra et al. Reference Chandra2010). They also act as probes of the interplanetary (Jokipii Reference Jokipii1973), interstellar (Rickett Reference Rickett1990) and intergalactic media (Zhou et al. Reference Zhou, Li, Wang, Fan and Wei2014), giving us insight into the structure and composition of the Universe on all scales.

Transient events have played an important role in astronomy since its early days. For example, there are numerous records of ‘guest stars’ by Chinese astronomers in the first century of the Common Era (Stephenson & Green Reference Stephenson and Green2002), some of which were later established to be historical supernovae. In Europe, Tycho Brahe’s detailed observations of SN 1572 were an important step forward in challenging the Aristotelian/Ptolemaic paradigm of the ‘unchanging heavens’ (Hinse et al. Reference Hinse, Dorch, Occhionero and Holck2023). In the present era, targeted monitoring and surveys of optical transients have led to major discoveries: perhaps most notably the discovery of the accelerating expansion of the Universe through observations of distant supernovae (Riess et al. Reference Riess1998; Perlmutter et al. Reference Perlmutter1999), which won the 2011 Nobel Prize for Physics. Most recently, the detection of a gravitational wave transient, a binary black hole merger (Abbott et al. Reference Abbott2016), led to the 2017 Nobel Prize for Physics and opened up the field of multi-messenger transients (Abbott et al. Reference Abbott2017b ).

In contrast to optical and X-ray wavebands, the dynamic radio sky had been relatively unexplored (beyond targeted observations). The notable exception to this was pulsars, the discovery (Hewish et al. Reference Hewish, Bell, Pilkington, Scott and Collins1968) and study (Hulse & Taylor Reference Hulse and Taylor1975) of which have led to two Nobel Prizes, in 1974 and 1993 respectively. Looking beyond pulsars, the general lack of large-scale time domain studies at radio frequencies (until recent times – see Section 4.3) has been largely due to observational limitations: widefield, sensitive surveys with multiple epochs were difficult and time consuming to conduct.

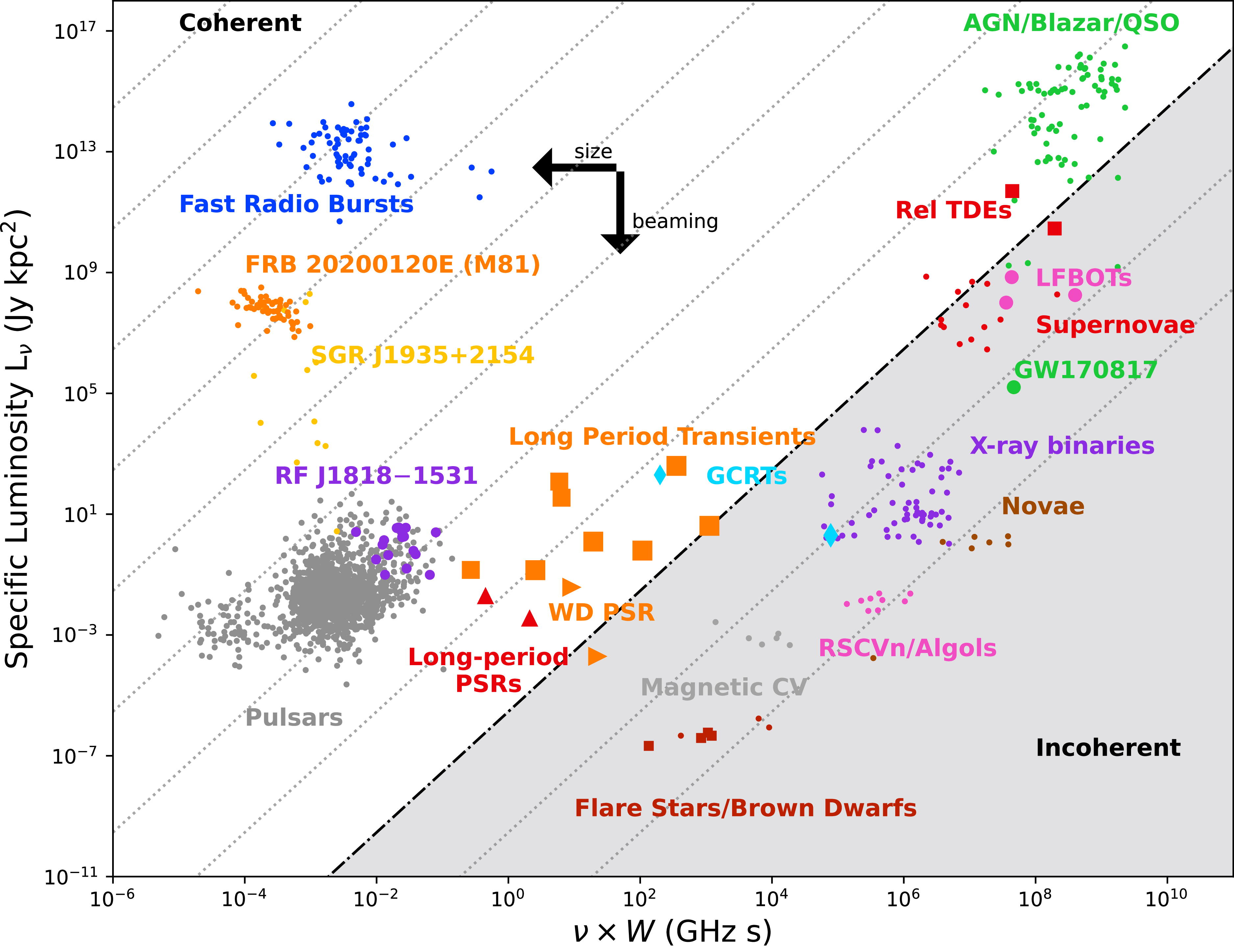

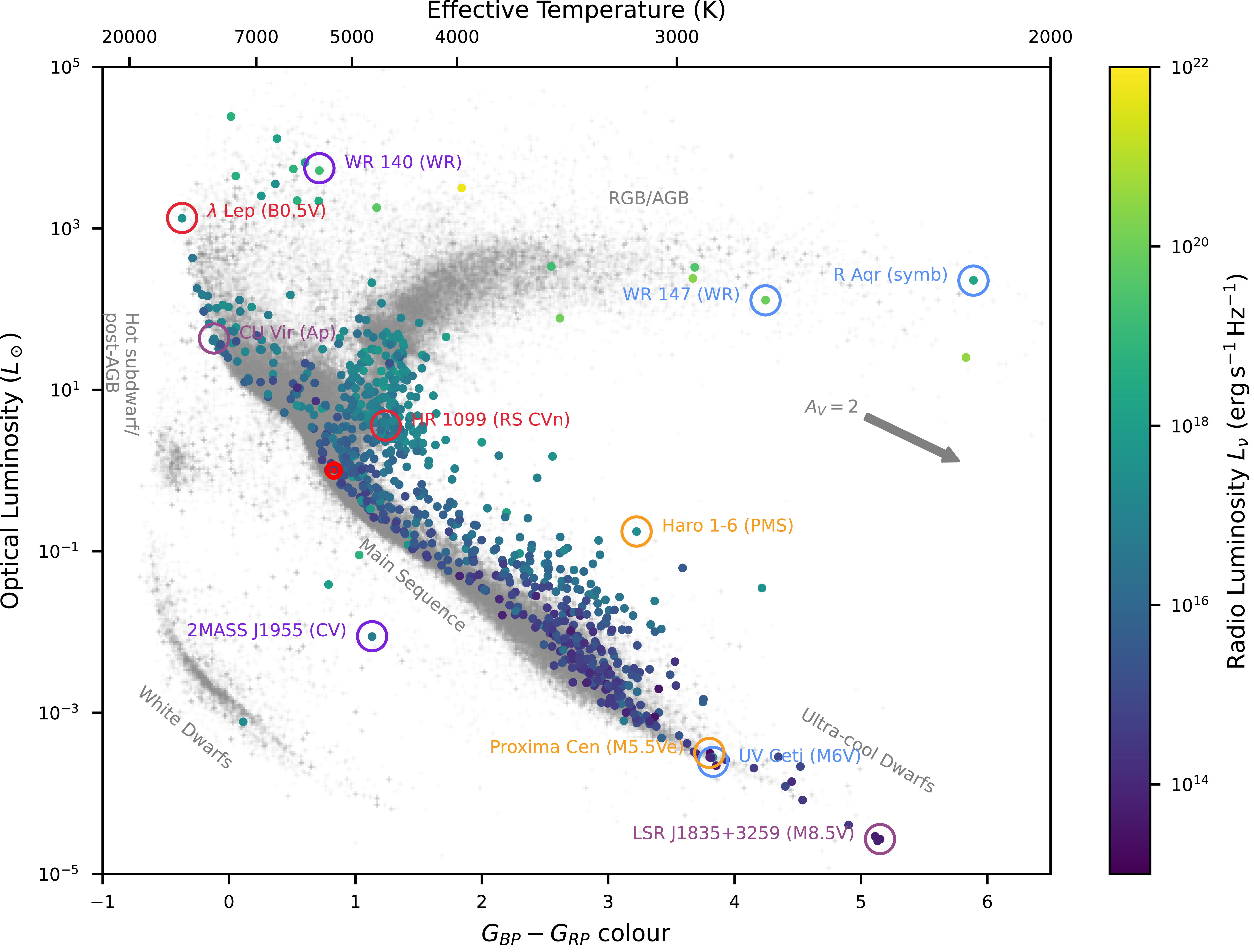

Figure 1. Transient phase space showing radio luminosity versus the product of timescale and observing frequency for different transient source classes, following Cordes et al. (Reference Cordes, Lazio and McLaughlin2004). Note that the luminosity assumes sources are beamed into only 1 sr and no relativistic beaming, which may or may not be appropriate for individual objects, while the timescales are just the observed variability timescales and ignore more constraining limits such as the finite sizes of e.g. stellar sources. For sources with relativistic beaming the true brightness temperature could be significantly lower (e.g. Readhead Reference Readhead1994), while for some stellar sources the true brightness temperature could be significantly higher, as suggested by the arrows. The diagonal lines show contours of brightness temperature, with coherent emitters having

![]() $T_B\gt10^{12}\,$

K. Adapted from Pietka et al. (Reference Pietka, Fender and Keane2015) and Nimmo et al. (Reference Nimmo2022), with select sources added: the binary neutron star merger GW170817 (Mooley et al. Reference Mooley2018c); LFBOTs (Ho et al. Reference Ho2019; Coppejans et al. Reference Coppejans2020; Ho et al. Reference Ho2020); relativistic TDEs (Mimica et al. Reference Mimica, Giannios, Metzger and Aloy2015; Andreoni et al. Reference Andreoni2022); flare stars/brown dwarfs (Hallinan et al. Reference Hallinan2007; Rose et al. Reference Rose2023; Route & Wolszczan Reference Route and Wolszczan2016; Zic et al. Reference Zic2019); long-period radio pulsars (Caleb et al. Reference Caleb2022; Wang et al. Reference Wang2025d); Galactic Centre radio transients (Hyman et al. Reference Hyman, Lazio, Kassim, Ray, Markwardt and Yusef-Zadeh2005; Wang et al. Reference Wang2021b

); white dwarf pulsars (Pelisoli et al. Reference Pelisoli2023; de Ruiter et al. Reference de Ruiter2025) and long-period transients (Wang et al. Reference Wang2025c

; Lee et al. Reference Lee2025; Wang et al. Reference Wang2021b

; Caleb et al. Reference Caleb2024; Hurley-Walker et al. Reference Hurley-Walker2024, Reference Hurley-Walker2023, Reference Hurley-Walker2022b

; Dong et al. Reference Dong2025b

). In particular we highlight the range of sources from Table 2 that are filling out the centre of this space, straddling the coherent/incoherent divide: long-period radio pulsars are upward-pointing triangles, GCRTs are diamonds, pulsing white dwarf binaries are right-pointing triangles, and long period transients (LPTs) are squares.

$T_B\gt10^{12}\,$

K. Adapted from Pietka et al. (Reference Pietka, Fender and Keane2015) and Nimmo et al. (Reference Nimmo2022), with select sources added: the binary neutron star merger GW170817 (Mooley et al. Reference Mooley2018c); LFBOTs (Ho et al. Reference Ho2019; Coppejans et al. Reference Coppejans2020; Ho et al. Reference Ho2020); relativistic TDEs (Mimica et al. Reference Mimica, Giannios, Metzger and Aloy2015; Andreoni et al. Reference Andreoni2022); flare stars/brown dwarfs (Hallinan et al. Reference Hallinan2007; Rose et al. Reference Rose2023; Route & Wolszczan Reference Route and Wolszczan2016; Zic et al. Reference Zic2019); long-period radio pulsars (Caleb et al. Reference Caleb2022; Wang et al. Reference Wang2025d); Galactic Centre radio transients (Hyman et al. Reference Hyman, Lazio, Kassim, Ray, Markwardt and Yusef-Zadeh2005; Wang et al. Reference Wang2021b

); white dwarf pulsars (Pelisoli et al. Reference Pelisoli2023; de Ruiter et al. Reference de Ruiter2025) and long-period transients (Wang et al. Reference Wang2025c

; Lee et al. Reference Lee2025; Wang et al. Reference Wang2021b

; Caleb et al. Reference Caleb2024; Hurley-Walker et al. Reference Hurley-Walker2024, Reference Hurley-Walker2023, Reference Hurley-Walker2022b

; Dong et al. Reference Dong2025b

). In particular we highlight the range of sources from Table 2 that are filling out the centre of this space, straddling the coherent/incoherent divide: long-period radio pulsars are upward-pointing triangles, GCRTs are diamonds, pulsing white dwarf binaries are right-pointing triangles, and long period transients (LPTs) are squares.

We now know the radio sky is variable on all timescales, from nanoseconds (Hankins et al. Reference Hankins, Kern, Weatherall and Eilek2003) through to months and years (Chandra & Frail Reference Chandra and Frail2012; Zauderer et al. Reference Zauderer, Berger, Margutti, Pooley, Sari, Soderberg, Brunthaler and Bietenholz2013). The past decade has seen many advances in our understanding of radio transients, from the detection of radio emission from a binary neutron star merger (Hallinan et al. Reference Hallinan2017), to the real-time detection of an extreme scattering event (Bannister et al. Reference Bannister, Stevens, Tuntsov, Walker, Johnston, Reynolds and Bignall2016) and the discovery of a new class of long period transients (Hurley-Walker et al. Reference Hurley-Walker2022b ). This review is being written as we prepare for the wave of discoveries that will come in the era of the SKA Observatory (SKAO; Dewdney et al. Reference Dewdney2022), which is expected to begin science verification observations in 2027 and 2029 for the SKA-Low and SKA-Mid telescopes, respectively.Footnote a

1.1. The context for this review

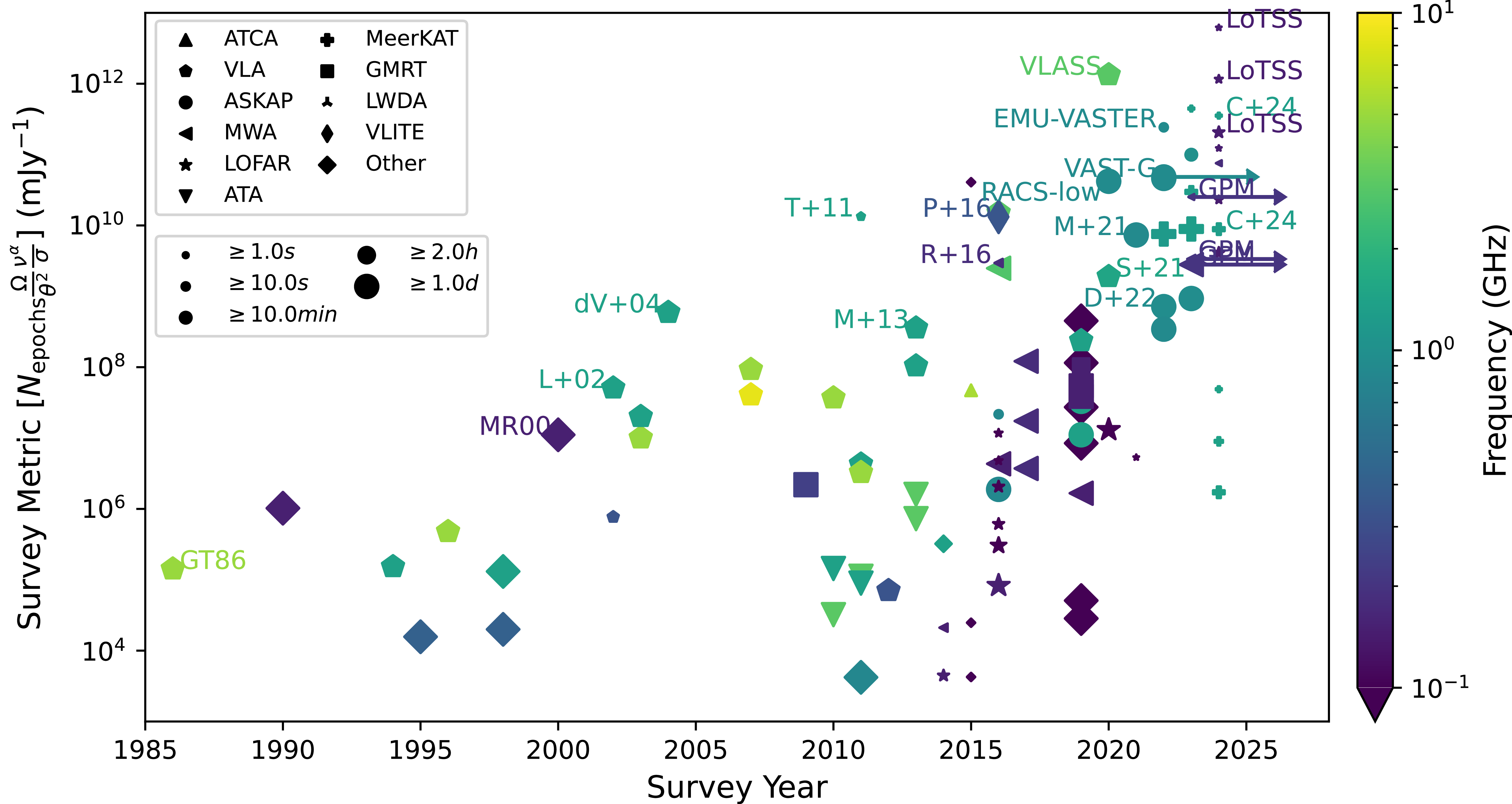

There have been a number of reviews of radio transient surveys, mostly written in anticipation of the advent of the ‘next-generation’ radio telescopes that would enable large-scale time-domain imaging surveys on the path to the SKAO. The first of these is Cordes et al. (Reference Cordes, Lazio and McLaughlin2004) who defined a phase space for the exploration of radio transients (we show an updated version of it in Figure 1), and proposed a metric for the optimisation of radio transients surveys (we discuss and expand on this in Section 4.1), as well as discussing some of the key science cases for the SKAO. When Fender & Bell (Reference Fender and Bell2011) reviewed the field, they considered the time domain radio sky was still relatively unexplored. They highlighted the great potential of the major surveys about to commence on MeerKAT (Jonas et al. Reference Jonas2016), the Australian SKA Pathfinder (ASKAP; Hotan et al. Reference Hotan2021), and other SKAO pathfinder and precursor telescopes, with a particular emphasis on the Low-Frequency Array (LOFAR; van Haarlem et al. Reference van Haarlem2013). However, their predictions were based primarily on the transient rates reported by Bower et al. (Reference Bower, Saul, Bloom, Bolatto, Filippenko, Foley and Perley2007), most of which were later shown to be spurious (Frail et al. Reference Frail, Kulkarni, Ofek, Bower and Nakar2012, see Section 4.3.4).

The next review paper was the product of the ‘Advancing Astrophysics with the Square Kilometre Array’ meeting in Italy in 2014 (Braun et al. Reference Braun, Bourke, Green, Keane and Wagg2015). Fender et al. (Reference Fender, Stewart, Macquart, Donnarumma, Murphy, Deller, Paragi and Chatterjee2015a ) discuss the advantages of radio observations for understanding transient objects and present updated limits on radio transient rates from the untargeted transient surveys available at the time; these rates and limits were crude, owing to the lack of robust large-scale samples and reliable real-time identification of transients. Although not formally a review paper, Mooley et al. (Reference Mooley2016) presents the most comprehensive recent compilation of radio transient surveys and detection rates. The online tableFootnote b has been updated to 2025, and hence serves as a very useful summary of work in this area. We draw on this in our review of the history of radio transient surveys presented in Section 4.3.

Just over twenty years on from Cordes et al. (Reference Cordes, Lazio and McLaughlin2004) there are several major radio transient surveys well underway, with the capability to detect significant numbers of transient sources across the full range of their stated scientific goals. The SKAO will be operational within

![]() $\sim5\textrm{--}8$

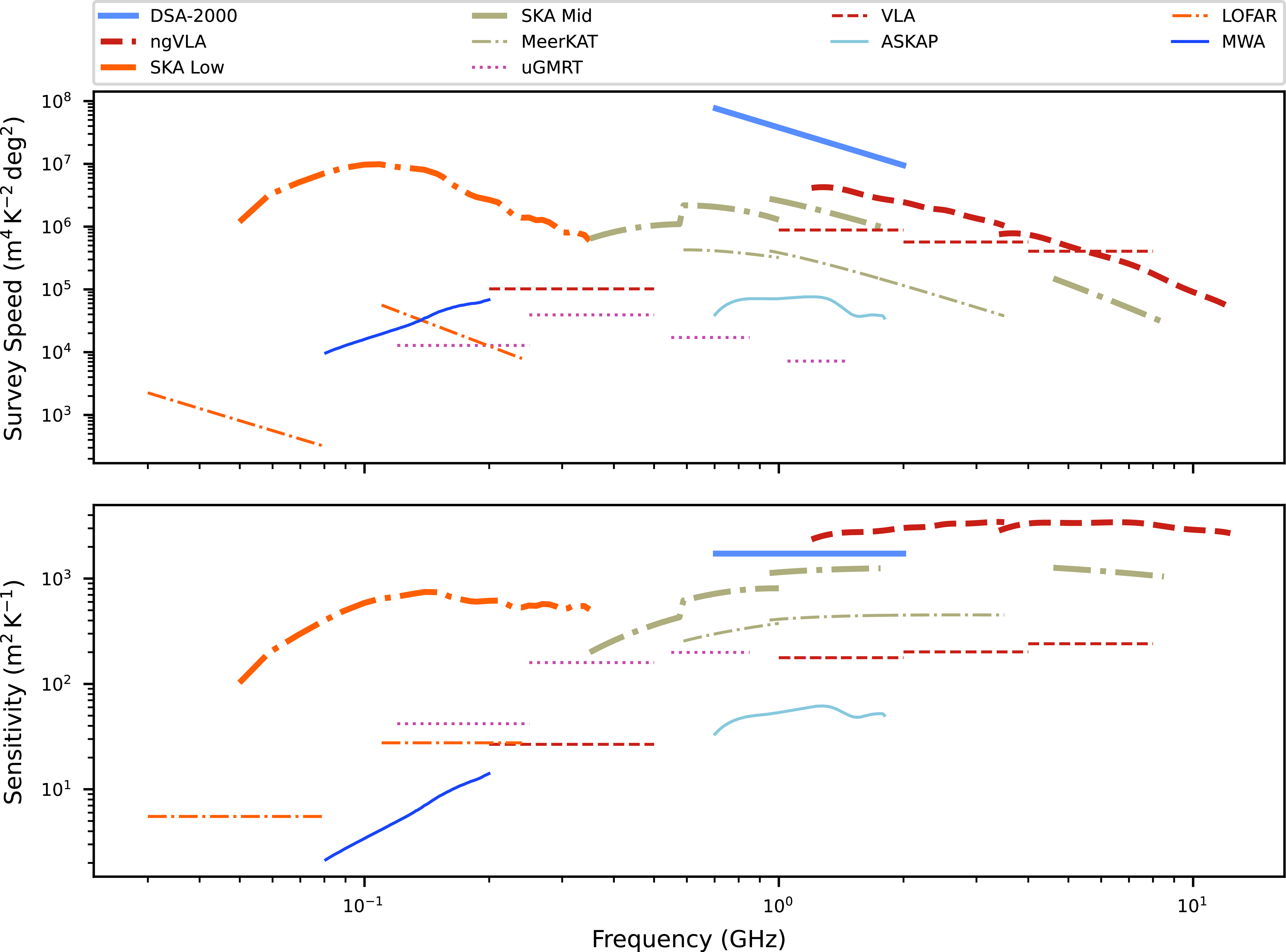

yr, and planning is underway for other future instruments including the next-generation Very Large Array (ngVLA; Murphy Reference Murphy2018) and Deep Synoptic Array (DSA-2000; Hallinan et al. Reference Hallinan2019). Hence, it is timely to do a comprehensive review of this area. We hope it will be useful as a milestone in capturing the state of the field as we enter an era of transformational surveys.

$\sim5\textrm{--}8$

yr, and planning is underway for other future instruments including the next-generation Very Large Array (ngVLA; Murphy Reference Murphy2018) and Deep Synoptic Array (DSA-2000; Hallinan et al. Reference Hallinan2019). Hence, it is timely to do a comprehensive review of this area. We hope it will be useful as a milestone in capturing the state of the field as we enter an era of transformational surveys.

The structure of the paper is as follows. In the rest of this section we outline the scope of the review and define some key terminology. In Section 2, we discuss the key emission mechanisms that cause radio variability and in Section 3 we describe each of the main classes of radio transients. In Section 4, we discuss the motivation for untargeted surveys, and present a history of radio transient surveys. In Section 5, we discuss the main detection methods and approaches for radio transients. In Section 6, we discuss the metrics used to measure variability, and how we characterise the time variable sky. In Section 7, we discuss SKAO-era telescopes and how we can incorporate what we have learned from previous work. Finally, in Section 8, we present the future outlook for the field of radio transients.

1.2. The scope of this review

In this review we will focus on results from interferometers in a synthesis imaging mode (i.e. not single dish or coherent beamforming, although we do discuss those separately), often referred to as ‘image domain’ or ‘slow’ transientsFootnote

c

or similar (also see Section 1.3). Early observations of slow transients using single-dish telescopes (e.g. Spangler, Shawhan, & Rankin Reference Spangler, Shawhan and Rankin1974a

), made detections that were difficult to verify and distinguish from interference (Davis et al. Reference Davis, Lovell, Palmer and Spencer1978). Most recent studies use interferometric imaging at frequencies

![]() $\lt30\,$

GHz, although very large single-dish telescopes can offer advantages (e.g. Route & Wolszczan Reference Route and Wolszczan2013; Route Reference Route2019). At higher frequencies bolometric imaging arrays are the best option for millimetre surveys (Whitehorn et al. Reference Whitehorn2016; Naess et al. Reference Naess2021).

$\lt30\,$

GHz, although very large single-dish telescopes can offer advantages (e.g. Route & Wolszczan Reference Route and Wolszczan2013; Route Reference Route2019). At higher frequencies bolometric imaging arrays are the best option for millimetre surveys (Whitehorn et al. Reference Whitehorn2016; Naess et al. Reference Naess2021).

For both scientific and technical reasons, this review focuses on astronomical phenomena that show variability at radio wavelengths on timescales of seconds to years. We will discuss the physical processes that cause this variability and summarise the main classes of objects that are detected as variable radio sources. We will also cover radio transients surveys, detection methods and population rates.

To define a clear scope for the paper, we will not discuss the following topics:

-

• Solar, heliospheric, and ionospheric science: The Sun is the brightest radio source in the sky, and was first detected in the early days of radio astronomy (Hey Reference Hey1946). The proximity of the Sun to Earth means we are able to study its radio variability in great detail. Solar radio astronomy typically uses different observational approaches and techniques from the radio transients community. In fact, almost all continuum imaging observations (whether targeted, or untargeted surveys) deliberately avoid the Sun due to the impact on data quality. The main exceptions to this are recent programs that use interplanetary scintillation (IPS) caused by the solar wind (discovered by Clarke Reference Clarke1964, and reported by Hewish, Scott, & Wills Reference Hewish, Scott and Wills1964), for example Morgan et al. (Reference Morgan2018), to both study the solar wind and to select the most compact extragalactic sources (e.g. Chhetri et al. Reference Chhetri, Ekers, Morgan, Macquart and Franzen2018). Likewise, ionospheric variability is both interesting in its own right (e.g. Loi et al. Reference Loi2015a ) and due to its impact on studying radio variability at low frequencies (e.g. Loi et al. Reference Loi2015b ). However, for both scientific and methodological reasons we will not include solar, heliospheric and ionospheric radio astronomy in this review. For a review of this research area in the context of the SKAO, see Nindos et al. (Reference Nindos, Kontar and Oberoi2019).

-

• Solar System objects: the planets in our own Solar System are detectable at radio wavelengths. The five magnetised planets (Earth, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune) all show auroral radio emission (Zarka Reference Zarka1998) and emission from their radiation belts (Mauk & Fox Reference Mauk and Fox2010). The non-magnetised planets show radio emission from thermal heating of the planet by incident solar radiation (Kellermann Reference Kellermann1966). Many radio studies of solar system planets have been done with both ground-based telescopes and spacecraft (e.g. the Voyager 1 and 2 missions; Warwick et al. Reference Warwick1979). Because of their rapid movement across the sky, it is common to detect Solar System planets (in particular Jupiter) in widefield radio imaging surveys (e.g. Table 2; Lenc et al. Reference Lenc, Murphy, Lynch, Kaplan and Zhang2018). Lessons learned from our solar system apply directly to exoplanetary systems (e.g., Kao et al. Reference Kao, Mioduszewski, Villadsen and Shkolnik2023 reported the first detection of radiation belts around an ultracool dwarf star). However, planets (and the Moon) are typically excluded in the process of searching for Galactic and extragalactic transients and we will not cover them in this review.

-

• Asteroids and meteors: When an asteroid (or material from an asteroid) enters the Earth’s atmosphere it vaporises, and can be seen as a streak of light across the sky. These large meteors are often called ‘fireballs’, and there are regular monitoring programs to detect them, such as the NASA All-sky Fireball NetworkFootnote d , due to their potential impact on orbiting spacecraft (e.g. Cooke & Moser Reference Cooke, Moser, Rudawska, Rendtel, Powell, Lunsford, Verbeeck and Knofel2012). Very low frequency (10–88 MHz) observations with the Long Wavelength Array (Taylor et al. Reference Taylor2012) established a correlation between low frequency transients and fireball trails, suggesting that the trails radiate at low radio frequencies (Obenberger et al. Reference Obenberger2014; Varghese et al. Reference Varghese, Dowell, Obenberger, Taylor, Anderson and Hallinan2024). In addition, meteor trails are known to reflect low frequency radio transmissions (e.g. Helmboldt et al. Reference Helmboldt, Ellingson, Hartman, Lazio, Taylor, Wilson and Wolfe2014). This makes asteroids a foreground source of radio transient bursts that need to be considered at low frequencies. However, since our focus is on Galactic and extragalactic transients we will not discuss them further in this review.

-

• Searches for extraterrestrial intelligence: SETI has been an active area of research in radio astronomy since the early 1960s. Searching for extraterrestrial communications or other technosignatures requires many of the same approaches as searching for astronomical transients, and the history of SETI is interwoven with the history of radio transients. In some cases SETI projects have piggybacked on astronomy observations, or searched existing archival data. In other cases they have involved dedicated programs. Substantial funding for radio telescopes and instrumentation has also come from SETI-motivated philanthropy, for example the Allen Telescope Array (ATA; Welch et al. Reference Welch2009) and Breakthrough Listen (Worden et al. Reference Worden2017). However, since the focus of this review is variable astronomical phenomena, we will not discuss SETI further. For reviews of SETI research, see Tarter (Reference Tarter2001) and Ekers et al. (Reference Ekers, Culler, Billingham and Scheffer2002). For a more recent discussion of approaches to detecting technosignatures, see Wright et al. (Reference Wright, Haqq-Misra, Frank, Kopparapu, Lingam and Sheikh2022).

-

• Radio frequency interference: RFI is an ever-present challenge for radio transient detection. Avoiding RFI was perhaps the most important factor in determining the scientific quality of sites for the SKAO telescopes (Schilizzi et al. Reference Schilizzi, Ekers, Dewdney and Crosby2024). Often appearing as extreme bursts of emission localised in frequency or time, RFI can mimic the astronomical signals we are trying to detect. This has resulted in false detections, such as the so-called ‘perytons,’ which were later identified as RFI from microwaves ovens (Petroff et al. Reference Petroff2015). At longer timescales, RFI generally has less impact on transient detection as it is averaged out in the process of synthesis imaging. However, it can still have a significant impact on image quality. Reflection of low frequency radio signals off satellites in low Earth orbits can create transient objects in images, and is an increasing problem (Prabu et al. Reference Prabu, Hancock, Zhang and Tingay2020). A very recent discovery is that of nanosecond electrostatic discharges from satellites (James et al. Reference James2025). In this review we will only touch on RFI in the context of its impact on transient detection approaches, in Section 5. For an overview of RFI mitigation methods see Fridman & Baan (Reference Fridman and Baan2001) and Offringa et al. (Reference Offringa, de Bruyn, Biehl, Zaroubi, Bernardi and Pandey2010). Lourenço et al. (Reference Lourenço2024) and Sihlangu et al. (Reference Sihlangu, Oozeer and Bassett2022) provide recent analyses of the RFI environment on the ASKAP and MeerKAT sites, respectively.

-

• Fast radio bursts: FRBs are astronomical radio flashes with durations of milliseconds (Lorimer et al. Reference Lorimer, Bailes, McLaughlin, Narkevic and Crawford2007). Their physical origin is as-yet unknown, although there are likely to be multiple classes of objects that cause FRBs (Pleunis et al. Reference Pleunis2021). While they are extremely interesting, and may be related to other types of radio transients (e.g., Bochenek et al. Reference Bochenek, Ravi, Belov, Hallinan, Kocz, Kulkarni and McKenna2020b ; Law, Connor, & Aggarwal Reference Law, Connor and Aggarwal2022), fast radio bursts themselves are beyond the scope of this review. This is partly for technical reasons (FRBs are most often discovered with different instrumentation and survey methods than the slower transients below, for instance using single dish telescopes or interferometric voltage beams) and partly for practical reasons (the huge amount of new science on FRBs and rapid developments necessitate their own reviews). For these reasons we point the reader to recent reviews such as Cordes & Chatterjee (Reference Cordes and Chatterjee2019), Petroff et al. (Reference Petroff, Hessels and Lorimer2022), or Zhang (Reference Zhang2023).

A final note: in the sections discussing survey strategy and the history of radio transients surveys, our focus will be on widefield imaging surveys. Hence we will not discuss, for example, large targeted monitoring programs such as those for interstellar scintillation (Lovell et al. Reference Lovell, Jauncey, Bignall, Kedziora-Chudczer, Macquart, Rickett and Tzioumis2003), follow-up of sources detected in other wavebands, for example gamma-ray bursts (GRBs; Frail et al. Reference Frail, Kulkarni, Berger and Wieringa2003) and large triggered follow-up programs (e.g. Staley et al. Reference Staley2013). When discussing what we know about different variable source classes, we will of course incorporate all sources of information.

1.3. Some notes on terminology

As the field of radio transients has evolved over the past few decades, there have been several important terms that are either (a) specific to this research area; (b) have been used in different ways in the community; or (c) have seen their usage evolve over this period. To avoid confusion we discuss and define them here.

-

• ‘Fast’ and ‘slow’ transients: these terms are generally used to mean variability on timescales faster than and slower than the telescope correlator integration time. Fast transient searches need to use data at a pre-correlator stage, and for most radio telescopes this is of the order of seconds. For example, the ASKAP integration time is 10 s (Hotan et al. Reference Hotan2021) and MeerKAT is 2–8 s (Jonas et al. Reference Jonas2016). For the VLA the default integration times for each configuration are between 2–5 s.Footnote e Due to the completely different data processing and analysis approaches (for example dedispersion is usually required in fast transient searches) it makes sense to consider these two domains separately. As a result, most of the major survey projects on SKAO pathfinder and precursor telescopes have split along these lines. For example, on ASKAP, the Commensal Real-time ASKAP Fast Transients Survey (CRAFT; Macquart et al. Reference Macquart2010) focuses on fast transients (also see Wang et al. Reference Wang2025b ) and the Variables and Slow Transients (VAST; Murphy et al. Reference Murphy2013) survey focuses on slow transients. Likewise on MeerKAT, the Transients and Pulsars with MeerKAT (TRAPUM; Stappers & Kramer Reference Stappers, Kramer, Taylor, Camilo, Leeuw and Moodley2016) project focused on fast transients and the ThunderKAT project (Fender et al. Reference Fender2016) focused on slow transients. Conveniently, the behaviour of most astrophysical phenomena also fall into one of these two regimes (see Figure 1), although some such as pulsars can show variability on both millisecond timescales and much slower timescales of minutes to hours, and new discoveries (e.g. Section 3.9) are further blurring the lines. This review will focus on slow transients.

-

• Transients and variables: as the era of large-scale imaging surveys started, there was considerable debate about how the terms ‘transient’ versus ‘variable’ should be used. When considering the underlying astronomical objects themselves, it is possible to make a distinction between persistent objects that show variable behaviour (e.g. flaring stars) and explosive events that appear, then fade and ultimately disappear (e.g. gamma-ray bursts). However, observationally this distinction is less clear, since the time morphology of a particular dynamic event is highly dependent on the sensitivity limit and time sampling of the observations. For example, radio bursts from a star that has quiescent emission below the sensitivity limit of the image will appear as transient events. Hence in this review, as in much of the literature, we use the terms transient and highly variable, relatively interchangeably (see, for example, comments in Section 5 of Mooley et al. Reference Mooley2016).

-

• Commensal and piggyback observations: The term ‘piggyback’ refers to the situation in which observations that are taken for a particular scientific purpose can be used for a different purpose, without affecting the original observing schedule and specifications. In radio astronomy, this strategy has been extensively used by SETI; for example the SERENDIP project in which data collected by all science projects on Arecibo was analysed independently for narrowband radio signals (Werthimer et al. Reference Werthimer2001). The word ‘commensal’ has its origins in biology. The Oxford Concise Medical Dictionary defines it as: ‘an organism that lives in close association with another of a different species without either harming or benefiting it’. It was introduced into the radio astronomy literature in the context of the plans for the Allen Telescope Array, to imply a more active form of piggybacking in which both parties had some influence over the observational strategy (DeBoer Reference DeBoer2006). The usage of commensal became more widespread in the literature after 2010, in the context of a number of new radio surveys being designed (e.g. Macquart et al. Reference Macquart2010; Wayth et al. Reference Wayth, Brisken, Deller, Majid, Thompson, Tingay and Wagstaff2011). In the current literature commensal and piggyback observations are often used interchangeably. Note that readers outside this area of research can be confused by this technical meaning.

-

• ‘Blind’ and untargeted surveys: The terms blind and untargeted are used interchangeably in the literature, to refer to a survey that has been designed without targeting specific objects, and with as few prior assumptions as possible. We prefer the term untargeted survey as it is more accurate and more inclusive.

2. Radio emission mechanisms and causes of variability

Astronomical objects that emit radio waves (from nearby planets and stars, to distant galaxies and active galactic nuclei; e.g. Kellermann & Verschuur Reference Kellermann and Verschuur1988) have a wide variety of emission types. In this section we focus on those types that produce transient and variable radio emission, either intrinsically, or as a result of propagation through an inhomogeneous ionised medium or other external causes. In general the emission will come from plasma where the particles (primarily electrons) are in local thermodynamic equilibrium (Condon & Ransom Reference Condon and Ransom2016), leading to thermal emission, or are not in equilibrium, leading to non-thermal emission (note, though, that some authors restrict thermal emission to only blackbody or thermal bremsstrahlung radiation). In most cases the sources of radio emission considered here arise from non-thermal plasmas.

For all of these objects we can consider the brightness temperature of the emission (Rybicki & Lightman Reference Rybicki and Lightman1985; Condon & Ransom Reference Condon and Ransom2016), which is the temperature of a hypothetical optically-thick thermal plasma that would emit at the same intensity. Note that this definition can be used even when the assumptions (like thermal emission) are not valid, as it is still a useful quantity for comparison. The brightness temperature is defined as:

where

![]() $I_\nu$

is the specific intensity (measured in

$I_\nu$

is the specific intensity (measured in

![]() $\mathrm{erg\,s}^{-1}\,\mathrm{cm}^{-2}\,\mathrm{Hz}^{-1}$

$\mathrm{erg\,s}^{-1}\,\mathrm{cm}^{-2}\,\mathrm{Hz}^{-1}$

![]() $\mathrm{sr}^{-1}$

or equivalent), the frequency is

$\mathrm{sr}^{-1}$

or equivalent), the frequency is

![]() $\nu$

,

$\nu$

,

![]() $k_B$

is Boltzmann’s constant, and c is the speed of light. For a source with flux density

$k_B$

is Boltzmann’s constant, and c is the speed of light. For a source with flux density

![]() $S_\nu$

and solid angle

$S_\nu$

and solid angle

![]() $\Omega$

, we have

$\Omega$

, we have

![]() $I_\nu=S_\nu/\Omega$

. Note that this form assumes radiation is in the Rayleigh-Jeans limit, with

$I_\nu=S_\nu/\Omega$

. Note that this form assumes radiation is in the Rayleigh-Jeans limit, with

![]() $h\nu \ll k_B T$

, even if that is not actually true. For non-thermal sources the brightness temperature,

$h\nu \ll k_B T$

, even if that is not actually true. For non-thermal sources the brightness temperature,

![]() $T_B$

, is different from the actual electron temperature

$T_B$

, is different from the actual electron temperature

![]() $T_e$

, and typically

$T_e$

, and typically

![]() $T_B \gg T_e$

.

$T_B \gg T_e$

.

We should also distinguish between incoherent and coherent emission (Melrose Reference Melrose2017). Most radiation sources are incoherent, such that each electron radiates independently and the total emission is found by summing over a distribution of electrons. For an incoherent source,

![]() $T_B$

is limited by two mechanisms:

$T_B$

is limited by two mechanisms:

![]() $k_B T_B$

should be less than the energy of the emitting electrons, and

$k_B T_B$

should be less than the energy of the emitting electrons, and

![]() $T_B$

should be

$T_B$

should be

![]() $\lt 10^{12}\,$

K because above this point radiation by inverse Compton scattering will increase significantly, leading to rapid energy loss and cooling back down to

$\lt 10^{12}\,$

K because above this point radiation by inverse Compton scattering will increase significantly, leading to rapid energy loss and cooling back down to

![]() $10^{12}\,$

K (Kellermann & Pauliny-Toth Reference Kellermann and Pauliny-Toth1969). Note that the upper limit on

$10^{12}\,$

K (Kellermann & Pauliny-Toth Reference Kellermann and Pauliny-Toth1969). Note that the upper limit on

![]() $T_b$

could be even lower if set by equipartion between magnetic and particle energies (Readhead Reference Readhead1994). In general it can be difficult to directly measure or constrain

$T_b$

could be even lower if set by equipartion between magnetic and particle energies (Readhead Reference Readhead1994). In general it can be difficult to directly measure or constrain

![]() $T_B$

. However, sources that vary on a timescale

$T_B$

. However, sources that vary on a timescale

![]() $\tau$

, have their angular size limited to

$\tau$

, have their angular size limited to

![]() $\theta \lt c\tau/d$

at a distance d, which limits the solid angle to

$\theta \lt c\tau/d$

at a distance d, which limits the solid angle to

![]() $\Omega \lt (c\tau/d)^2$

. This then implies for the brightness temperature (e.g. Readhead Reference Readhead1994; Cordes et al. Reference Cordes, Lazio and McLaughlin2004; Miller-Jones et al. Reference Miller-Jones, Gallo, Rupen, Mioduszewski, Brisken, Fender, Jonker and Maccarone2008; Bell et al. Reference Bell2019):

$\Omega \lt (c\tau/d)^2$

. This then implies for the brightness temperature (e.g. Readhead Reference Readhead1994; Cordes et al. Reference Cordes, Lazio and McLaughlin2004; Miller-Jones et al. Reference Miller-Jones, Gallo, Rupen, Mioduszewski, Brisken, Fender, Jonker and Maccarone2008; Bell et al. Reference Bell2019):

with flux density

![]() $S_\nu$

, ignoring relativistic beaming or cosmological effects. While the latter can be easily estimated for a source with a known redshift, relativistic beaming is an important contributor to sources having apparent brightness temperatures much higher than their intrinsic values (Readhead Reference Readhead1994): depending on the speed of the relativistic motion and the geometry, the luminosity can be boosted by the Doppler factor to some power (depending on the intrinsic spectrum) which can be 10 or more, with the inferred brightness temperature from variability boosted by the Doppler factor cubed since the timescale is also modified (Readhead Reference Readhead1994; Lähteenmäki & Valtaoja Reference Lähteenmäki and Valtaoja1999), so the overall boost can exceed a factor of 1000.

$S_\nu$

, ignoring relativistic beaming or cosmological effects. While the latter can be easily estimated for a source with a known redshift, relativistic beaming is an important contributor to sources having apparent brightness temperatures much higher than their intrinsic values (Readhead Reference Readhead1994): depending on the speed of the relativistic motion and the geometry, the luminosity can be boosted by the Doppler factor to some power (depending on the intrinsic spectrum) which can be 10 or more, with the inferred brightness temperature from variability boosted by the Doppler factor cubed since the timescale is also modified (Readhead Reference Readhead1994; Lähteenmäki & Valtaoja Reference Lähteenmäki and Valtaoja1999), so the overall boost can exceed a factor of 1000.

When beaming is not a factor, or when corrections have been done, the intrinsic (excluding variability caused by propagation, discussed in Section 2.5.1) brightness temperature can then be estimated. For brighter sources (large

![]() $S_\nu$

) and faster variability (small

$S_\nu$

) and faster variability (small

![]() $\tau$

), sources can have

$\tau$

), sources can have

![]() $T_B \gt10^{12}\,$

K, sometimes by many orders of magnitude, requiring an alternate mechanism for the emission (Cordes et al. Reference Cordes, Lazio and McLaughlin2004). These coherent mechanisms, where the contributions of individual particles can add up in-phase, relate to plasma instabilities or ‘collective plasma radiation processes’ (Melrose Reference Melrose1991, Reference Melrose2017), where the emission from N particles is

$T_B \gt10^{12}\,$

K, sometimes by many orders of magnitude, requiring an alternate mechanism for the emission (Cordes et al. Reference Cordes, Lazio and McLaughlin2004). These coherent mechanisms, where the contributions of individual particles can add up in-phase, relate to plasma instabilities or ‘collective plasma radiation processes’ (Melrose Reference Melrose1991, Reference Melrose2017), where the emission from N particles is

![]() $\propto N^2$

rather than

$\propto N^2$

rather than

![]() $\propto N$

for incoherent emission. A full description of these mechanisms is beyond the scope of this review, and we point the reader to helpful reviews such as Melrose (Reference Melrose2017). In this review we will discuss each briefly and associate the mechanisms with the sources where they operate.

$\propto N$

for incoherent emission. A full description of these mechanisms is beyond the scope of this review, and we point the reader to helpful reviews such as Melrose (Reference Melrose2017). In this review we will discuss each briefly and associate the mechanisms with the sources where they operate.

2.1. Synchrotron emission

The majority of the extragalactic radio sources that are bright enough for us to observe, are either active galactic nuclei (AGN, both ‘radio-loud’ and ‘radio-quiet’; Kellermann et al. Reference Kellermann, Sramek, Schmidt, Shaffer and Green1989) or star-forming galaxies, with the former dominating at higher flux densities (Condon, Cotton, & Broderick Reference Condon, Cotton and Broderick2002; Matthews et al. Reference Matthews, Condon, Cotton and Mauch2021). For AGN the emission is primarily via synchrotron radiation (Rybicki & Lightman Reference Rybicki and Lightman1985), a (typically) non-thermal, incoherent process, from a combination of their cores/nuclei and jets (Fanaroff & Riley Reference Fanaroff and Riley1974) produced by accretion onto central supermassive black holes (Blandford, Meier, & Readhead Reference Blandford, Meier and Readhead2019). For star-forming galaxies the emission is a combination of synchrotron emission from supernova remnants (SNRs) and diffuse gas as well as thermal emission from H II regions (Helou, Soifer, & Rowan-Robinson Reference Helou, Soifer and Rowan-Robinson1985; Chevalier Reference Chevalier1982). Since sources like SNRs and H II regions are usually too extended to show variability we will not consider them further, although in some cases young SNRs can show secular evolution (e.g. Sukumar & Allen Reference Sukumar and Allen1989), and their study can connect back to supernovae (Milisavljevic & Fesen Reference Milisavljevic, Fesen, Alsabti and Murdin2017).

Synchrotron emission is the result of relativistic electrons spiralling around magnetic field lines (Rybicki & Lightman Reference Rybicki and Lightman1985; Condon & Ransom Reference Condon and Ransom2016). The emission from a single electron depends on its energy, the magnetic field strength, and the angle between the electron’s motion and the magnetic field, with a spectrum peaking near the critical frequency which is the gyrofrequency (depending on the magnetic field strength) modified by the electron’s Lorentz factor. But for a power-law distribution of electron energies, the summed emission results in a power-law with spectral index

![]() $\alpha$

, defined as:

$\alpha$

, defined as:

depending on the underlying distribution of the electrons (note that some authors define the spectral index with the opposite sign,

![]() $S_\nu \propto \nu^{-\alpha}$

, and care must be taken to correctly interpret values).

$S_\nu \propto \nu^{-\alpha}$

, and care must be taken to correctly interpret values).

Most synchrotron sources have a steep spectrum (

![]() $\alpha\lt0$

) with

$\alpha\lt0$

) with

![]() $\alpha\approx -0.7$

(Sabater et al. Reference Sabater2019; Franzen et al. Reference Franzen2021, and indeed most non-thermal sources have negative spectral indices in general). At lower frequencies, the brightness temperature approaches the effective temperature of the relativistic electrons and this emission is modified by synchrotron self-absorption, which causes the steep spectrum to turn over into one with

$\alpha\approx -0.7$

(Sabater et al. Reference Sabater2019; Franzen et al. Reference Franzen2021, and indeed most non-thermal sources have negative spectral indices in general). At lower frequencies, the brightness temperature approaches the effective temperature of the relativistic electrons and this emission is modified by synchrotron self-absorption, which causes the steep spectrum to turn over into one with

![]() $\alpha \approx 2.5$

.

$\alpha \approx 2.5$

.

Synchrotron radiation is ubiquitous in radio astronomy, and most sources are steady emitters. However, there are two physical scenarios that can lead to transient or variable emission: changes in accretion rate and jet launching in accreting compact objects on different mass scales; and explosions interacting with the surrounding medium.

2.1.1. Accretion and jet ejection

The process of disk accretion and jet ejection is ubiquitous across astrophysics (e.g. de Gouveia Dal Pino Reference de Gouveia Dal Pino2005), and where compact objects are involved those jets are typically relativistic (e.g. Bromberg et al. Reference Bromberg, Nakar, Piran and Sari2011b ) with similar characteristics that depend primarily on the accretor mass, accretion rate, and ejection velocity. In the context of radio transients, we focus on relativistic jets from AGN and X-ray binaries (XRBs), which we discuss below.

AGN dominate the radio sky at flux densities above a few millijanskys (at centimetre wavelengths), and most show little variability (Hovatta et al. Reference Hovatta, Tornikoski, Lainela, Lehto, Valtaoja, Torniainen, Aller and Aller2007; Hodge et al. Reference Hodge, Becker, White and Richards2013; Stewart et al. Reference Stewart2016; Mooley et al. Reference Mooley2016; Bell et al. Reference Bell2019; Murphy et al. Reference Murphy2021), although fluctuations of a few to few tens of percent are not uncommon (e.g. Falcke et al. Reference Falcke, Lehár, Barvainis, Nagar, Wilson, Peterson and Pogge2001; Mundell et al. Reference Mundell, Ferruit, Nagar and Wilson2009) and variations are both more significant and faster at higher radio frequencies (e.g. Ackermann et al. Reference Ackermann2011; Hovatta et al. Reference Hovatta, Tornikoski, Lainela, Lehto, Valtaoja, Torniainen, Aller and Aller2007), especially for sub-classes of AGN such as blazars (Max-Moerbeck Reference Max-Moerbeck2014; Richards et al. Reference Richards2011a ).

Aside from extrinsic causes (see Section 2.5.1) most of these changes are thought to be due to modest changes in the jets (e.g. Nyland et al. Reference Nyland2020), such as the propagation of shocks along the jets (Marscher & Gear Reference Marscher and Gear1985; Hughes, Aller, & Aller Reference Hughes, Aller and Aller1989, disk instabilities (Czerny et al. Reference Czerny, Siemiginowska and Janiuk2009; Janiuk & Czerny Reference Janiuk and Czerny2011), or changes in accretion power (Koay et al. Reference Koay, Vestergaard, Bignall, Reynolds and Peterson2016; Wołowska et al. 2017). These effects can be magnified by the jet orientation, with jets directed close to the line of sight having larger variability on shorter timescales due to relativistic effects (Lister Reference Lister2001): changes in orientation can therefore dominate any intrinsic changes in their effects on variability.

However, a subset of these sources show higher variability (e.g. Barvainis et al. Reference Barvainis, Lehár, Birkinshaw, Falcke and Blundell2005). This may be due to large-scale changes in the jet orientation from accretion instabilities or interaction within a binary super massive black hole (Palenzuela, Lehner, & Liebling Reference Palenzuela, Lehner and Liebling2010; An et al. Reference An, Baan, Wang, Wang and Hong2013), or large-scale changes in the jet power from changes in the accretion flow (Mooley et al. Reference Mooley2016; Nyland et al. Reference Nyland2020). These sources apparently transition from radio-quiet (often undetectable) to radio-loud (although the distinction may not be so simple, e.g. Kellermann et al. Reference Kellermann, Condon, Kimball and Perley2016), with the radio luminosity apparently increasing by more than an order of magnitude over several decades, potentially as a result of newly-launched jets.

Such changes in the jet behaviour can be replicated on much smaller scales (both physical and mass) through accreting X-ray binaries hosting neutron stars or black holes (Fender, Belloni, & Gallo Reference Fender, Belloni and Gallo2004a ; Fender et al. Reference Fender, Stirling, Spencer, Brown, Pooley, Muxlow and Miller-Jones2006; Fender Reference Fender2016). Here, small-scale changes in the jet power during the hard state correspond to normal AGN variability, while significant launching of superluminal jet components in the transition between hard and soft states correspond to the radio-quiet to radio-loud transitions of AGN.

2.1.2. Explosions and shocks

In contrast to the scenarios above, where accretion leads to jets that can vary as the accretion rate or direction varies, the radio emission from transient events such as classical novae (Chomiuk, Metzger, & Shen Reference Chomiuk, Metzger and Shen2021a ; Chomiuk et al. Reference Chomiuk2021b ), supernovae (Weiler et al. Reference Weiler, Panagia, Montes and Sramek2002), long and short gamma-ray bursts (Piran Reference Piran2004; Berger Reference Berger2014), magnetars (Frail, Kulkarni, & Bloom Reference Frail, Kulkarni and Bloom1999a ), neutron star mergers (Hallinan et al. Reference Hallinan2017), tidal disruption events (Levan et al. Reference Levan2011; Bloom et al. Reference Bloom2011) and similar phenomena lead more naturally to variable radio emission. These sorts of explosions/ejections have been among the most anticipated targets for large-area radio surveys (e.g. Metzger, Williams, & Berger Reference Metzger, Williams and Berger2015b ). Note that even though some of these sources, like gamma-ray bursts, may be powered by very short-lived relativistic jets, we discuss them separately from Section 2.1.1 as the jets themselves are not seen at radio wavelengths, but only their impact on the surrounding medium.

The basic scenario here is where an explosion leads to a rapid ejection of material. This outflow can be Newtonian or relativistic, and it can be collimated or spherical. Eventually the ejecta will impact the surrounding medium (typically circumstellar or interstellar material) leading to shock waves that amplify any magnetic fields present and accelerate electrons to relativistic energies, leading to synchrotron emission (Chevalier Reference Chevalier1982). This so-called ‘afterglow’ model is present in many variants in many different physical scenarios, where the mass, velocity, and angular profile of the ejecta and the radial profile of the surrounding medium can all change (Sari, Piran, & Narayan Reference Sari, Piran and Narayan1998; Chevalier & Li Reference Chevalier and Li2000; Chandra & Frail Reference Chandra and Frail2012; Mooley et al. Reference Mooley2018a ,Reference Mooleyc; Troja et al. Reference Troja2018; Lazzati et al. Reference Lazzati, Perna, Morsony, Lopez-Camara, Cantiello, Ciolfi, Giacomazzo and Workman2018).

Normally, for very energetic events like gamma-ray bursts the ejecta are observed to be ultrarelativsistic and jetted (Rhoads Reference Rhoads1997; Mészáros & Rees Reference Mészáros and Rees1997), such that the initial afterglow emission is beamed into a solid angle of

![]() $\sim 1/\Gamma^2$

(where

$\sim 1/\Gamma^2$

(where

![]() $\Gamma$

is the bulk Lorentz factor) centred on the jet axis, which is also where the

$\Gamma$

is the bulk Lorentz factor) centred on the jet axis, which is also where the

![]() $\gamma$

-rays themselves are visible. At later times the Lorentz factor will decrease so the solid angle will increase, leading to increasing visibility of the late-time afterglow emission. Eventually, when

$\gamma$

-rays themselves are visible. At later times the Lorentz factor will decrease so the solid angle will increase, leading to increasing visibility of the late-time afterglow emission. Eventually, when

![]() $1/\Gamma$

approaches the intrinsic jet size the entire jet will be visible. This tends to happen at the same time as the jet material will begin to expand sideways (Sari, Piran, & Halpern Reference Sari, Piran and Halpern1999). Together these lead to an achromatic ‘jet break’ in the lightcurve (Sari et al. Reference Sari, Piran and Halpern1999; Rhoads Reference Rhoads1999). Measurement of jet breaks can then be used to infer the jet size and hence intrinsic energetics of collimated explosions (Frail et al. Reference Frail2001).

$1/\Gamma$

approaches the intrinsic jet size the entire jet will be visible. This tends to happen at the same time as the jet material will begin to expand sideways (Sari, Piran, & Halpern Reference Sari, Piran and Halpern1999). Together these lead to an achromatic ‘jet break’ in the lightcurve (Sari et al. Reference Sari, Piran and Halpern1999; Rhoads Reference Rhoads1999). Measurement of jet breaks can then be used to infer the jet size and hence intrinsic energetics of collimated explosions (Frail et al. Reference Frail2001).

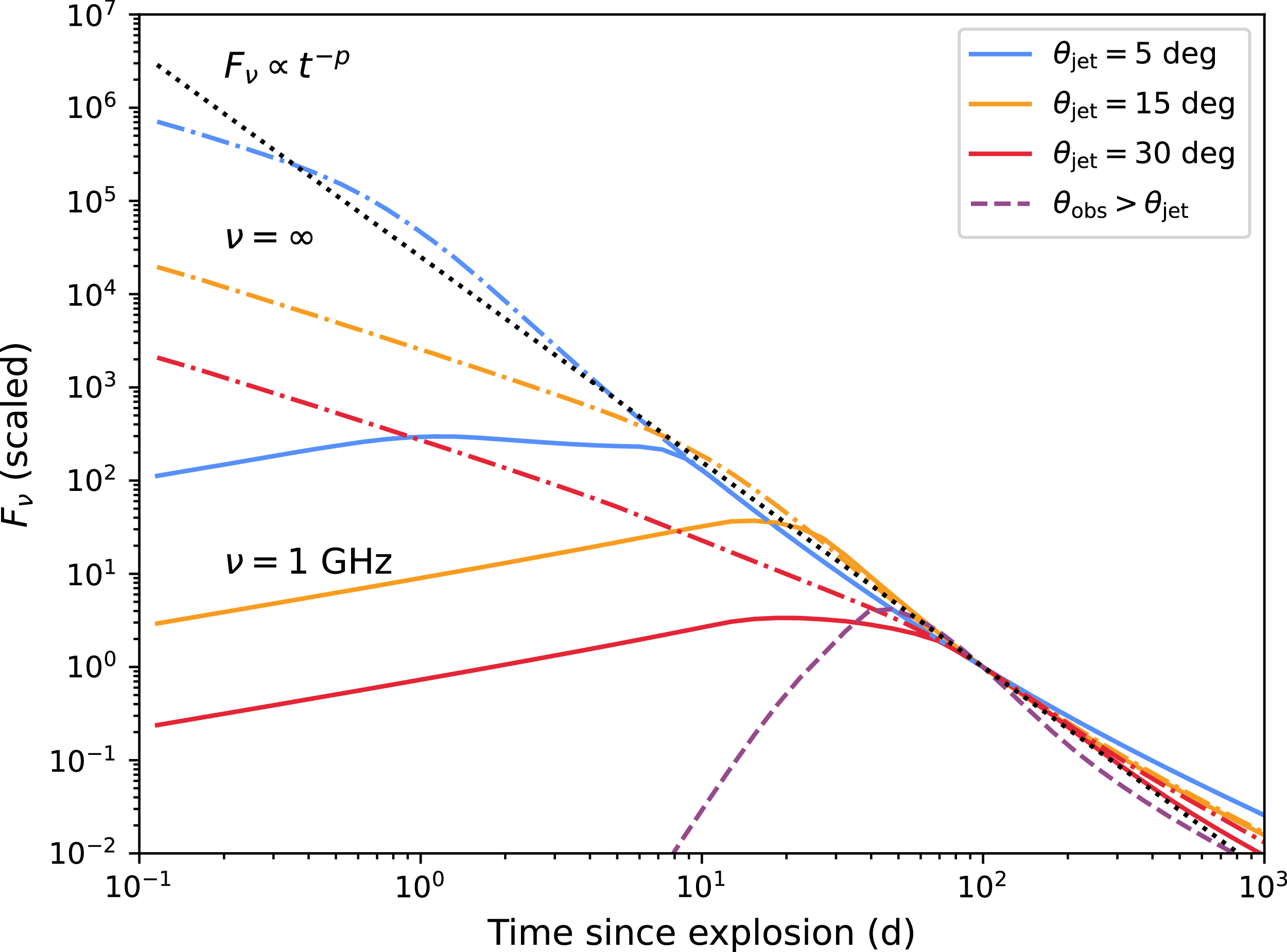

This also gives rise to the concept of an ‘orphan afterglow’, where only the late-time radio emission is visible from our line of sight (Rhoads Reference Rhoads2003; Ghirlanda et al. Reference Ghirlanda2014). Such an event would have a steeper and shorter rise than an on-axis GRB, but merge onto the same power-law in the decline (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Model GRB lightcurves, computed using Ryan et al. (Reference Ryan, van Eerten, Piro and Troja2020) and inspired by Piran (Reference Piran2004). These models use the simplest possible model for a relativistic jet. The top dash-dotted curves are for infinite frequency (ignoring any effects of self-absorption), while the lower solid curves are for a frequency of 1 GHz. All curves are normalised at 10 d. For both frequencies, we show jet opening angles of

![]() $\theta_\mathrm{jet}=5\deg$

(blue),

$\theta_\mathrm{jet}=5\deg$

(blue),

![]() $15\deg$

(orange), and

$15\deg$

(orange), and

![]() $30\deg$

(green) with an on-axis observer (

$30\deg$

(green) with an on-axis observer (

![]() $\theta_\mathrm{obs}=0$

). The infinite frequency models show jet breaks when the jet has decelerated to a bulk Lorentz factor of

$\theta_\mathrm{obs}=0$

). The infinite frequency models show jet breaks when the jet has decelerated to a bulk Lorentz factor of

![]() $1/\theta_\mathrm{jet}$

, after which they have a similar power-law behaviour with

$1/\theta_\mathrm{jet}$

, after which they have a similar power-law behaviour with

![]() $F_\nu \propto \nu^{-p}$

(black dotted line), where p is the power-law index of the electron distribution. We also show a jet seen by an off-axis observer, potentially an ‘orphan afterglow’, since the observer would miss any high-energy emission (red dashed curve). This has similar late-time behaviour but is much fainter at early times.

$F_\nu \propto \nu^{-p}$

(black dotted line), where p is the power-law index of the electron distribution. We also show a jet seen by an off-axis observer, potentially an ‘orphan afterglow’, since the observer would miss any high-energy emission (red dashed curve). This has similar late-time behaviour but is much fainter at early times.

The general behaviour for all of these afterglows is a series of power-law increases and declines (Sari et al. Reference Sari, Piran and Narayan1998), where the increase reflects the expanding shock front as well as the changing level of self-absorption. This increase happens first at higher frequencies because the self-absorption is less significant there. Eventually the entire afterglow becomes optically thin, at which point it transitions into a decline phase as the ejecta expand and slow down. During this phase a standard non-thermal steep spectrum is present (Weiler et al. Reference Weiler, Panagia, Montes and Sramek2002). This is illustrated in Figure 2, which shows lightcurves with and without the effect of self-absorption. If absorption is not an issue, the peak on-axis flux density is expected to occur when the shock has swept up a mass comparable to its own material and starts to decelerate, and it will scale with the energy of the explosion (Nakar & Piran Reference Nakar and Piran2011; Metzger et al. Reference Metzger, Williams and Berger2015b

). The time until the peak will scale with the energy of the explosion to the

![]() $\frac{1}{3}$

power (neglecting cosmological effects).

$\frac{1}{3}$

power (neglecting cosmological effects).

We can also see in Figure 2 the lightcurve from a potential orphan afterglow. One clear difficulty with all of these lightcurves is that they have the same late-time behaviour, so without a lucky early detection or robust limits on prompt high-energy emission (complicated when the explosion time is also weakly constrained), many different phenomena can be fit with the same data.

2.2. Free-free emission

A small fraction of variable sources emit primarily via free-free (or bremsstrahlung) emission (Condon & Ransom Reference Condon and Ransom2016; Osterbrock & Ferland Reference Osterbrock and Ferland2006), typically in a thermal plasma. This is produced by electrons accelerated electrostatically around ions. At higher frequencies the emission typically has

![]() $\alpha\approx -0.1$

(Condon & Ransom Reference Condon and Ransom2016; Chomiuk et al. Reference Chomiuk2021b

), which then turns over into an opaque source with

$\alpha\approx -0.1$

(Condon & Ransom Reference Condon and Ransom2016; Chomiuk et al. Reference Chomiuk2021b

), which then turns over into an opaque source with

![]() $\alpha \approx 2$

once it becomes self-absorbed at lower frequencies.

$\alpha \approx 2$

once it becomes self-absorbed at lower frequencies.

The primary sources of variable free-free emission are classical novae (CNe; Chomiuk et al. Reference Chomiuk, Metzger and Shen2021a ,Reference Chomiuk b ), where a thermonuclear explosion on an accreting white dwarf has expelled material into the interstellar medium. These are frequently detected through optical and infrared time-domain surveysFootnote f although their emission spans the electromagnetic spectrum. At radio wavelengths, the traditional emission from CNe is free-free emission from a slowly expanding sphere of ionised ejecta (Hjellming et al. Reference Hjellming, Wade, Vandenberg and Newell1979; Seaquist & Palimaka Reference Seaquist and Palimaka1977), which evolves over timescales of weeks–years as the emission first increases due to decreasing self-absorption and then declines due to decreasing density (since emission is proportional to the square of the electron density). While more complex sources are now observed to have non-thermal synchrotron emission from interactions between the ejecta and the surrounding medium (Krauss et al. Reference Krauss2011; Weston et al. Reference Weston2016a ,Reference Weston b ; Finzell et al. Reference Finzell2018, and see Section 2.1.2), even the thermal emission itself can be more complex both spatially and temporally (Nelson et al. Reference Nelson2014; Chomiuk et al. Reference Chomiuk2014; Chomiuk et al. Reference Chomiuk2021b ).

2.3. Stellar emission: Gyrosynchrotron, plasma, and electron cyclotron maser emission

In a number of stellar systems, especially for cooler, later-type stars we can detect gyrosynchrotron emission, which is an incoherent, (usually) non-thermal process related to synchrotron emission (Dulk Reference Dulk1985; Güdel Reference Güdel2002). Here, however, the electrons are only mildly relativistic. This leads to broad-band emission that has significant (but not 100%) circular polarisation at higher frequencies, where it is optically thin. At lower frequencies we see a typical optically-thick spectral index of

![]() $\alpha=+2.5$

and a steep spectrum on the higher frequency side, with the power-law index depending on the underlying distribution of electron energies.

$\alpha=+2.5$

and a steep spectrum on the higher frequency side, with the power-law index depending on the underlying distribution of electron energies.

In contrast, plasma emission is a coherent process (Melrose Reference Melrose2017) observed in stellar flares (Güdel Reference Güdel2002; Bastian Reference Bastian1990), converting plasma turbulence into radiation via non-linear plasma processes. It can account for brightness temperatures up to

![]() $10^{18}\,$

K, with emission at the fundamental or harmonic of the plasma frequency (determined by the local electron density), typically at lower radio frequencies (

$10^{18}\,$

K, with emission at the fundamental or harmonic of the plasma frequency (determined by the local electron density), typically at lower radio frequencies (

![]() $\lesssim 1\,$

GHz): at higher frequencies the emission suffers from free-free absorption.

$\lesssim 1\,$

GHz): at higher frequencies the emission suffers from free-free absorption.

Finally, electron cyclotron maser emission (ECME) is also a coherent process observed in stellar flares (Dulk Reference Dulk1985; Güdel Reference Güdel2002). Instead of the plasma frequency, the emission is at the fundamental or (low) harmonic of the cyclotron frequency (determined by the local magnetic field). ECME dominates over plasma emission in diffuse highly-magnetised plasma such that the plasma frequency is much less than the cyclotron frequency (Treumann Reference Treumann2006), so measurement of frequency structure or cutoffs can be used to constrain the magnetic field strength. It can result in brightness temperatures up to

![]() $10^{20}\,$

K and circular polarisation of up to 100%. The emission can also be elliptically polarised, with a combination of linear and circular polarisation. This is typically only seen in pulsars (Melrose Reference Melrose2017) and planets (Zarka Reference Zarka1998), although it has been seen in a small number of late-type stars (Spangler, Rankin, & Shawhan Reference Spangler, Rankin and Shawhan1974b

; Lynch et al. Reference Lynch, Lenc, Kaplan, Murphy and Anderson2017; Villadsen & Hallinan Reference Villadsen and Hallinan2019).

$10^{20}\,$

K and circular polarisation of up to 100%. The emission can also be elliptically polarised, with a combination of linear and circular polarisation. This is typically only seen in pulsars (Melrose Reference Melrose2017) and planets (Zarka Reference Zarka1998), although it has been seen in a small number of late-type stars (Spangler, Rankin, & Shawhan Reference Spangler, Rankin and Shawhan1974b

; Lynch et al. Reference Lynch, Lenc, Kaplan, Murphy and Anderson2017; Villadsen & Hallinan Reference Villadsen and Hallinan2019).

2.4. Pulsar-related variability

Pulsar radio emission as seen from Earth is inherently variable, with regular modulation on the timescale of the rotational period (although see Basu, Athreya, & Mitra Reference Basu, Athreya and Mitra2011). Despite decades of study the pulsar emission mechanism still eludes detailed understanding (Melrose Reference Melrose2017; Lorimer & Kramer Reference Lorimer and Kramer2012; Philippov & Kramer Reference Philippov and Kramer2022), but it can achieve extremely high brightness temperatures of above

![]() $10^{20}\,$

K. Typically the emission has a steep spectral index (

$10^{20}\,$

K. Typically the emission has a steep spectral index (

![]() $\alpha\approx -1.5$

; Bates, Lorimer, & Verbiest Reference Bates, Lorimer and Verbiest2013; Jankowski et al. Reference Jankowski, van Straten, Keane, Bailes, Barr, Johnston and Kerr2018; Anumarlapudi et al. Reference Anumarlapudi2023; Karastergiou et al. Reference Karastergiou, Johnston, Posselt, Oswald, Kramer and Weltevrede2024), although some highly-magnetised pulsars known as magnetars can have much flatter spectra (Camilo et al. Reference Camilo, Ransom, Halpern, Reynolds, Helfand, Zimmerman and Sarkissian2006). It can be highly polarised – both linear and circular – with rotations of the linear position angle and sign changes of the circular polarisation occurring during the pulse.

$\alpha\approx -1.5$

; Bates, Lorimer, & Verbiest Reference Bates, Lorimer and Verbiest2013; Jankowski et al. Reference Jankowski, van Straten, Keane, Bailes, Barr, Johnston and Kerr2018; Anumarlapudi et al. Reference Anumarlapudi2023; Karastergiou et al. Reference Karastergiou, Johnston, Posselt, Oswald, Kramer and Weltevrede2024), although some highly-magnetised pulsars known as magnetars can have much flatter spectra (Camilo et al. Reference Camilo, Ransom, Halpern, Reynolds, Helfand, Zimmerman and Sarkissian2006). It can be highly polarised – both linear and circular – with rotations of the linear position angle and sign changes of the circular polarisation occurring during the pulse.

However, these properties do not explain why pulsars (especially millisecond pulsars) can be identified in traditional image domain transient and variable searches. The rotational modulation, on timescales of 1 ms to 10’s of seconds, is typically far too fast to appear as a variable source for an imaging survey (although this is now changing with short timescale imaging – see Sections 3.9 and 5.4). In addition to extrinsic modulations that can be very significant for pulsars (Section 2.5.1), there are a number of intrinsic mechanisms that can lead to variability on longer timescales. These range from ‘nulling’ (Backer Reference Backer1970), where the pulsar turns off for tens to hundreds of pulses, to intermittency (Kramer et al. Reference Kramer, Lyne, O’Brien, Jordan and Lorimer2006), where the pulsar turns off for days to months, to eclipses where the pulses or even the continuum emission disappear for part of a binary orbit (timescales of minutes to hours; Fruchter, Stinebring, & Taylor Reference Fruchter, Stinebring and Taylor1988; Broderick et al. Reference Broderick2016; Polzin et al. Reference Polzin, Breton, Bhattacharyya, Scholte, Sobey and Stappers2020). It is also possible that rather than distinct variable sub-classes, there may be a continuum of variability across the population (Lower et al. Reference Lower2025; Keith et al. Reference Keith2024) with ties between the rotational, pulse profile, and flux density variations that can be seen broadly with sufficient precision. Like the underlying emission mechanism, the theoretical basis for these changes is also not well understood.

Finally, for magnetars (Kaspi & Beloborodov Reference Kaspi and Beloborodov2017), presumed reconfiguration of their magnetic fields during bursts or giant flares can lead to the sudden appearance of pulsed radio emission (Camilo et al. Reference Camilo, Ransom, Halpern, Reynolds, Helfand, Zimmerman and Sarkissian2006), in addition to the ejection of relativistic plasma leading to synchrotron afterglows discussed in Section 2.1.2. This pulsed emission can have different spectral properties to typical pulsars, and fades on timescales of months.

2.5. Extrinsic variability

2.5.1. Diffractive and refractive scintillation

When the radio waves from a source propagate through an inhomogeneous ionised medium, the waves can bend and diffract to form spatial variations in the wavefront. If the observer is moving relative to the wavefront, this can result in temporal variability known as scintillation (Rickett Reference Rickett1990; Narayan Reference Narayan1992). Such scintillation has been observed coming from the heliosphere and interplanetary medium (IPS; Hewish et al. Reference Hewish, Scott and Wills1964) as well as the interstellar medium (interstellar scintillation or ISS; Scheuer Reference Scheuer1968; Rickett Reference Rickett1969). Interstellar scintillation is only detectable for the most compact radio sources, such as compact cores of AGN (Lovell et al. Reference Lovell, Jauncey, Bignall, Kedziora-Chudczer, Macquart, Rickett and Tzioumis2003), distance relativistic explosions (Goodman Reference Goodman1997; Frail et al. Reference Frail, Kulkarni, Nicastro, Feroci and Taylor1997), or pulsars and fast radio bursts. Moreover, scintillation can have a range of properties depending on the source size and observing frequency.

Relevant for scintillation is the Fresnel scale,

![]() $r_\mathrm{F} \equiv \sqrt{\frac{\lambda d}{2\pi}}$

, for a source at distance d observed at wavelength

$r_\mathrm{F} \equiv \sqrt{\frac{\lambda d}{2\pi}}$

, for a source at distance d observed at wavelength

![]() $\lambda$

. Also relevant is the diffraction scale

$\lambda$

. Also relevant is the diffraction scale

![]() $r_\mathrm{d}$

over which the phase variance is 1 rad. The ratio of these then defines the scintillation strength,

$r_\mathrm{d}$

over which the phase variance is 1 rad. The ratio of these then defines the scintillation strength,

![]() $ r_\mathrm{F}/r_\mathrm{d}$

. At higher frequencies and for closer sources the scintillation is typically in the ‘weak’ regime (

$ r_\mathrm{F}/r_\mathrm{d}$

. At higher frequencies and for closer sources the scintillation is typically in the ‘weak’ regime (

![]() $r_\mathrm{F}/r_\mathrm{ d} \ll 1$

), with small (

$r_\mathrm{F}/r_\mathrm{ d} \ll 1$

), with small (

![]() $\ll 1$

) rms phase perturbations on the Fresnel scale (Rickett Reference Rickett1990; Cordes & Lazio Reference Cordes and Lazio1991; Narayan Reference Narayan1992; Hancock et al. Reference Hancock, Charlton, Macquart and Hurley-Walker2019), leading to fractional variability

$\ll 1$

) rms phase perturbations on the Fresnel scale (Rickett Reference Rickett1990; Cordes & Lazio Reference Cordes and Lazio1991; Narayan Reference Narayan1992; Hancock et al. Reference Hancock, Charlton, Macquart and Hurley-Walker2019), leading to fractional variability

![]() $\ll 1$

.

$\ll 1$

.

More interesting is the ‘strong’ regime (

![]() $r_\mathrm{F}/r_\mathrm{d} \gg 1$

), where the phase fluctuations over the Fresnel scale are large. In this regime we can observe both diffractive (Scheuer Reference Scheuer1968) and refractive (Sieber Reference Sieber1982; Rickett, Coles, & Bourgois Reference Rickett, Coles and Bourgois1984) effects.

$r_\mathrm{F}/r_\mathrm{d} \gg 1$

), where the phase fluctuations over the Fresnel scale are large. In this regime we can observe both diffractive (Scheuer Reference Scheuer1968) and refractive (Sieber Reference Sieber1982; Rickett, Coles, & Bourgois Reference Rickett, Coles and Bourgois1984) effects.

Diffractive scintillation results from multipath propagation (Goodman et al. Reference Goodman, Romani, Blandford and Narayan1987) from many independent patches which can add constructively or destructively, leading to large intensity fluctuations in a frequency-dependent manner. The patches each scatter radiation into an angle

![]() $\theta_\mathrm{r}=r_\mathrm{r}/d$

, with the refractive scale

$\theta_\mathrm{r}=r_\mathrm{r}/d$

, with the refractive scale

![]() $r_\mathrm{ r}\equiv r_\mathrm{F}^2/r_\mathrm{d}$

. This phenomenon requires very small sources, with angular sizes

$r_\mathrm{ r}\equiv r_\mathrm{F}^2/r_\mathrm{d}$

. This phenomenon requires very small sources, with angular sizes

![]() $\theta_\mathrm{d}\equiv r_\mathrm{d}/d \ll \theta_\mathrm{ r}$

, and so is usually limited to pulsars, although compact relativistic explosions like GRBs can also scintillate diffractively in their early phases (Goodman Reference Goodman1997). For diffractive scintillation, the timescale and bandwidth both increase with observing frequency, and the modulation can saturate at

$\theta_\mathrm{d}\equiv r_\mathrm{d}/d \ll \theta_\mathrm{ r}$

, and so is usually limited to pulsars, although compact relativistic explosions like GRBs can also scintillate diffractively in their early phases (Goodman Reference Goodman1997). For diffractive scintillation, the timescale and bandwidth both increase with observing frequency, and the modulation can saturate at

![]() $\sim 100$

% although it can also appear to be lower when averaging over multiple ‘scintles’ (time-frequency maxima).

$\sim 100$

% although it can also appear to be lower when averaging over multiple ‘scintles’ (time-frequency maxima).

Refractive scintillation, on the other hand, is due to large scale focusing and defocusing over scales

![]() $r_\mathrm{r}$

, and where the sources need to be compact compared to

$r_\mathrm{r}$

, and where the sources need to be compact compared to

![]() $\theta_\mathrm{r}$

. Refractive scintillation corresponds to lower modulation over longer timescales and wider bandwidths.

$\theta_\mathrm{r}$

. Refractive scintillation corresponds to lower modulation over longer timescales and wider bandwidths.

2.5.2. Extreme scattering events

Beyond the stochastic variations caused by the turbulent interstellar medium discussed above, systematic monitoring of compact extragalactic radio sources discovered discrete high-amplitude changes in source brightness with a characteristic shape, called ‘extreme scattering events’ (ESEs; Fiedler et al. Reference Fiedler, Dennison, Johnston and Hewish1987). Subsequently also seen in Galactic pulsars (Cognard et al. Reference Cognard, Bourgois, Lestrade, Biraud, Aubry, Darchy and Drouhin1993), ESEs are believed to be due to coherent lensing structures within the interstellar medium (ISM) (Fiedler et al. Reference Fiedler, Dennison, Johnston, Waltman and Simon1994). However, significant questions remain regarding the natures of those structures that seem much denser and with higher pressure than the average ISM (Clegg et al. Reference Clegg, Fey and Lazio1998). Whether the structures are one dimensional (filaments), two dimensional (sheets), or three dimensional is still debated (Romani, Blandford, & Cordes Reference Romani, Blandford and Cordes1987; Pen & King Reference Pen and King2012; Henriksen & Widrow Reference Henriksen and Widrow1995; Walker & Wardle Reference Walker and Wardle1998), as the models need to reproduce the temporal and frequency structure of ESEs (Walker Reference Walker, Haverkorn and Goss2007; Vedantham Reference Vedantham and Murphy2018).

There is considerable work ongoing to improve real-time detection of ESEs (Bannister et al. Reference Bannister, Stevens, Tuntsov, Walker, Johnston, Reynolds and Bignall2016), which would lead to better observations of their environments. At the same time there are studies of the models of the structures that cause ESEs (Jow, Pen, & Baker Reference Jow, Pen and Baker2024; Dong, Petropoulou, & Giannios Reference Dong, Petropoulou and Giannios2018; Rogers & Er Reference Rogers and Er2019), as well as attempts to identify the underlying causes of the ISM inhomogeneities (Walker et al. Reference Walker, Tuntsov, Bignall, Reynolds, Bannister, Johnston, Stevens and Ravi2017).

2.5.3. Gravitational lensing

Separate from variability induced by scintillation, extragalactic radio sources may exhibit variability induced by gravitational lensing along the line of sight. This has been predicted to appear in several ways. Radio sources that already showed multiple lensed images could have substructure lensed by small compact objects (typical masses

![]() $\sim M_\odot$

) within the lensing galaxy (Gopal-Krishna & Subramanian 1991; Koopmans & de Bruyn Reference Koopmans and de Bruyn2000; Biggs Reference Biggs2023), showing correlated but not identical variations between the separate images on timescales of days. However, this can be hard to distinguish from scintillation (Koopmans et al. Reference Koopmans2003; Biggs Reference Biggs2021) – indeed there have been many reports of microlensing in the radio that have been difficult to verify (Koopmans & de Bruyn Reference Koopmans and de Bruyn2000; Vernardos et al. Reference Vernardos2024). While gravitational lensing should be achromatic, and hence show different behaviour from scintillation, the varying size of the radio emission region – assumed to be a knot of synchrotron-emitting material within a Doppler-boosted relativistic jet – with frequency can cause apparent frequency dependence.

$\sim M_\odot$

) within the lensing galaxy (Gopal-Krishna & Subramanian 1991; Koopmans & de Bruyn Reference Koopmans and de Bruyn2000; Biggs Reference Biggs2023), showing correlated but not identical variations between the separate images on timescales of days. However, this can be hard to distinguish from scintillation (Koopmans et al. Reference Koopmans2003; Biggs Reference Biggs2021) – indeed there have been many reports of microlensing in the radio that have been difficult to verify (Koopmans & de Bruyn Reference Koopmans and de Bruyn2000; Vernardos et al. Reference Vernardos2024). While gravitational lensing should be achromatic, and hence show different behaviour from scintillation, the varying size of the radio emission region – assumed to be a knot of synchrotron-emitting material within a Doppler-boosted relativistic jet – with frequency can cause apparent frequency dependence.

A related phenomenon could be seen with larger lensing masses. In this case (Vedantham et al. Reference Vedantham2017; Peirson et al. Reference Peirson2022) the lens masses would be

![]() $10^{3-6}\,{\rm M}_\odot$

, causing achromatic variability on timescales of months–years in the lightcurve of a single source (the lensed images are not separable). This would be similar to lensing observed from high-energy blazars in

$10^{3-6}\,{\rm M}_\odot$

, causing achromatic variability on timescales of months–years in the lightcurve of a single source (the lensed images are not separable). This would be similar to lensing observed from high-energy blazars in

![]() $\gamma$

-rays (e.g. Barnacka, Glicenstein, & Moudden Reference Barnacka, Glicenstein and Moudden2011), although the details of the lensed sources are likely different (Spingola et al. Reference Spingola2016).

$\gamma$

-rays (e.g. Barnacka, Glicenstein, & Moudden Reference Barnacka, Glicenstein and Moudden2011), although the details of the lensed sources are likely different (Spingola et al. Reference Spingola2016).

3. Classes of radio transients

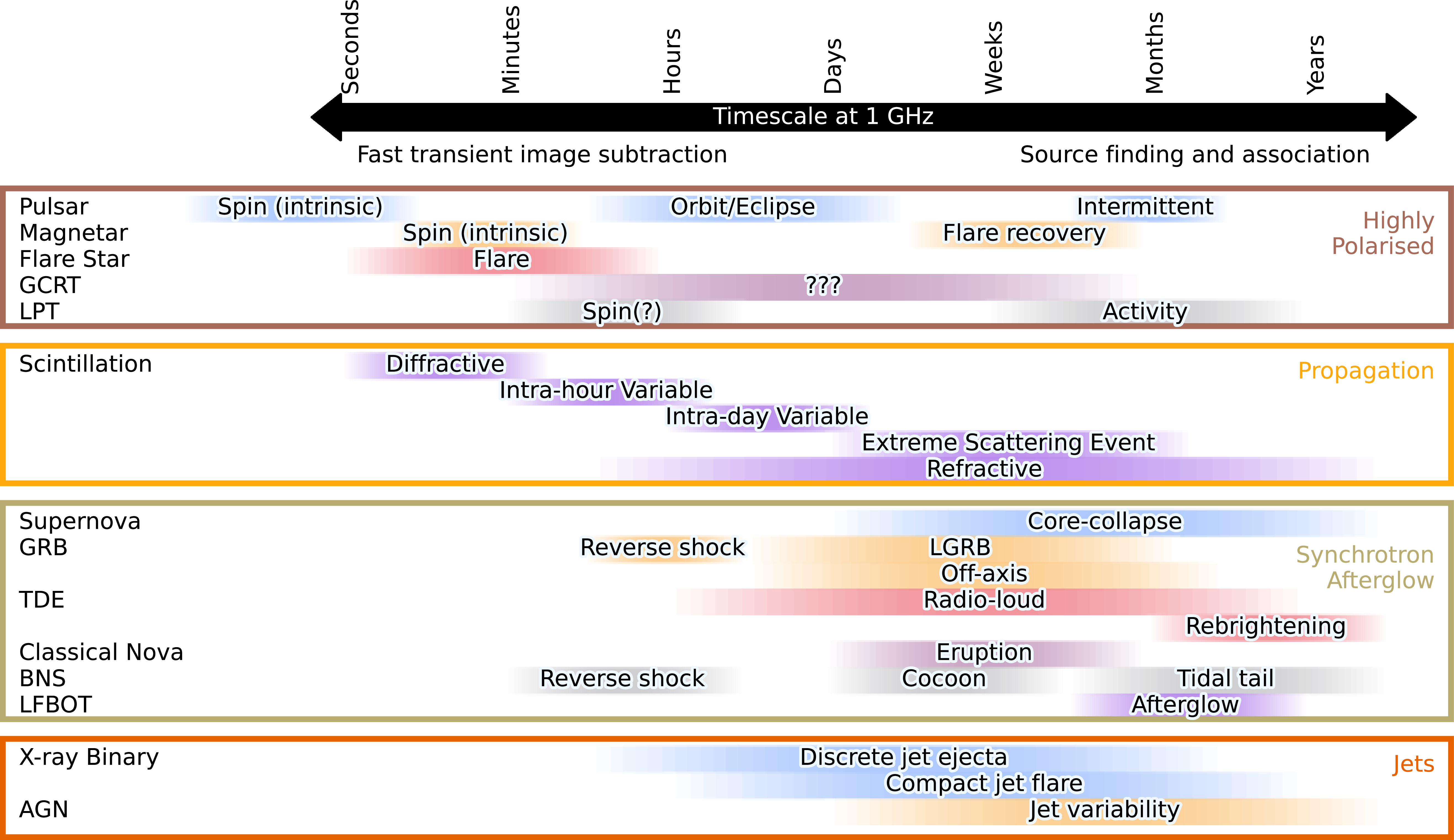

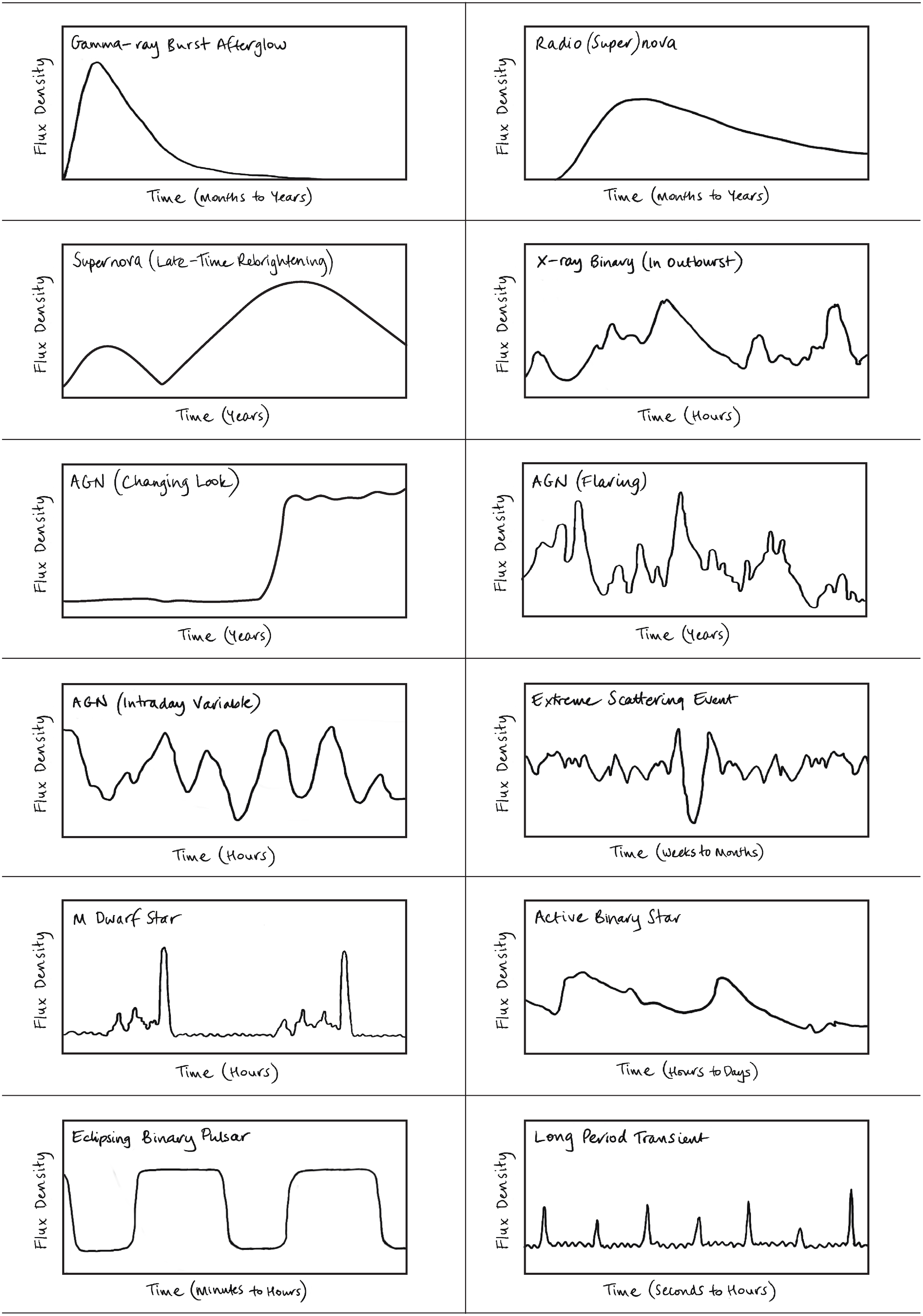

Now we have presented the main physical mechanisms that cause radio variability, in this section we discuss each of the main classes of radio transient and variable objects. Our focus is on intrinsic variability (propagation effects were covered in Section 2.5) and what we can learn from radio observations. We also make the case for why radio transient surveys are important, in addition to targeted observations of individual objects. Since there is a limit to the amount of detail we can go into in this paper, where possible we point the reader to relevant review papers. The following subsections are roughly ordered from highly energetic extragalactic objects, through to stars, binaries with compact objects, and Galactic transients. We summarise the different variability timescales for the different classes of transients in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Plot showing the relevant timescales of different classes of radio transients. Approximate limits of variability timescales are shown for different sources and different mechanisms. We also separate the highly-polarised largely coherent transients in the top box from the synchrotron afterglows (Section 2.1.2) in the third box. We roughly delineate the timescales for traditional transient searches that find sources individually in each epoch and associate them across epochs (

![]() $\gtrsim\,$

hours, e.g. Swinbank et al. Reference Swinbank2015; Rowlinson et al. Reference Rowlinson2019; Pintaldi et al. Reference Pintaldi, Stewart, O’Brien, Kaplan and Murphy2022) and those that use image-subtraction or related techniques to find shorter-timescale variability at a reduced computational cost (

$\gtrsim\,$

hours, e.g. Swinbank et al. Reference Swinbank2015; Rowlinson et al. Reference Rowlinson2019; Pintaldi et al. Reference Pintaldi, Stewart, O’Brien, Kaplan and Murphy2022) and those that use image-subtraction or related techniques to find shorter-timescale variability at a reduced computational cost (

![]() $\lesssim\,$

hours, e.g. Wang et al. Reference Wang2023; Fijma et al. Reference Fijma2024; Smirnov et al. Reference Smirnov2025a

).

$\lesssim\,$

hours, e.g. Wang et al. Reference Wang2023; Fijma et al. Reference Fijma2024; Smirnov et al. Reference Smirnov2025a

).

3.1. Gamma-ray bursts

Detecting radio afterglows from gamma-ray bursts (GRBs), unbiased by higher frequency detections, was a major motivation for widefield radio transient surveys (as discussed in Section 4.1). Because of their particular importance in this context, we give a brief background to radio observations of GRBs, before summarising our current understanding of their physics.

3.1.1. Radio detection of gamma-ray bursts