Introduction

The term “Women of Color” is ubiquitousFootnote 1. Commonly used as a descriptor for all nonwhite women, the term has seen a notable increase in usage and academic study in recent years (Sanbonmatsu, Greene, and Matos Reference Sanbonmatsu, Greene and Matos2025; Carey and Lizotte Reference Carey and Mary-Kate2023; Fujiwara and Roshanravan Reference Fujiwara and Roshanravan2018; Matos, Greene, and Sanbonmatsu Reference Matos, Greene and Sanbonmatsu2020; Reference Matos, Greene and Sanbonmatsu2021). Yet, it is not fully known if Women of Color (WoC) is a coalitional identity that shapes political attitudes, a race-neutral label used to describe a group of nonwhite women, or both. I argue that the term operates as a descriptive label and an identity. As a descriptor, WoC functions similarly to a racial or pan-ethnic label applied to nonwhite women based on visible traits or perceived ethnoracial heritage, such as skin tone, language, or surname. This categorization is often treated as objective and neutral, applied without necessarily considering an individual’s sense of identity or lived experiences. In both media and academic discourse, nonwhite women are often labeled as WoC, even if they do not identify with the term or feel a sense of group belonging. However, when adopted as an identity—the focus of this study—WoC can carry greater political and social significance. Unlike descriptive labels, identity is subjective and dynamic, shaped by self-perception, lived experiences, and sociopolitical context. For many women, the term WoC is deeply connected to racial justice, feminism, and resistance to the interlocking systems of oppression that nonwhite women face. Scholars have found that individuals actively adopt both WoC and PoC identities (Sanbonmatsu, Greene, and Matos Reference Sanbonmatsu, Greene and Matos2025; Matos, Greene, and Sanbonmatsu Reference Matos, Greene and Sanbonmatsu2021; Greene, Matos, and Sanbonmatsu Reference Greene, Matos and Sanbonmatsu2022; Starr and Freeland Reference Starr and Freeland2024; Lee and Sheng Reference Lee and Sheng2024; Pérez Reference Pérez2021). Many Black and Latina women identify as a WoC, and when embraced as an identity, it is politically meaningful (Matos, Greene, and Sanbonmatsu Reference Matos, Greene and Sanbonmatsu2021). In addition to Black and Latina women, Asian and other racially marginalized women also experience discrimination rooted in their intersecting identities (Collins Reference Collins, Baca Zinn and Dill1994; Harris and Ordona, Reference Harris, Ordoña and Anzaldúa1990; Masuoka and Junn Reference Masuoka and Junn2013; Zinn and Dill Reference Zinn and Dill1994). These shared experiences create the potential for cross-racial coalitions, which may reinforce WoC identity and intersectional WoC-linked fate.

Given that Asian American womenFootnote 2 face racialized gender oppression similar to other nonwhite women, I ask: Do Asian American women identify as WoC? More importantly, do those who adopt this collective identity share political attitudes with other WoC? The Asian American community is very diverse, encompassing over 20 ethnic and national origin groups with distinct cultures and religions. Their varied migration histories were shaped in large part by U.S. immigration laws, which were exclusionary until recent decades. Asian Americans also differ significantly by class and physical appearance. Despite perceptions of economic success and educational attainment, Asian Americans are often viewed as “perpetual foreigners,” unassimilable to American culture (Kim Reference Kim1999; Volpp Reference Volpp2005). This perceived success has helped fuel the “model minority” stereotype, which obscures internal diversity, downplays systemic racism, and weakens solidarity with other communities of color (Okamoto Reference Okamoto2014; Kim Reference Kim2004; Fujiwara and Roshanravan Reference Fujiwara and Roshanravan2018). I hypothesize that Asian women will adopt a WoC identity and feel a sense of linked fate with WoC, contributing to shared political attitudes on race-gendered issues.

While there is significant scholarship on WoC, much of it exists outside of political science. Within the discipline, this body of work is relatively new and steadily growing. For decades, gender studies scholars have included Asian women in the WoC discourse (Castañeda Reference Castañeda1992; Mohanty, Reference Mohanty1991; Fujiwara and Roshanravan Reference Fujiwara and Roshanravan2018; Yamada Reference Yamada, Moraga and Anzaldúa2021). A term that originated during the second wave of the women’s movement, WoC was considered to be a political constituency, an alliance rooted in shared struggles rather than exclusively shared racial heritage (Mohanty, Reference Mohanty1991). Due to the label’s connection to women’s rights, racial justice, and other progressive movements (Starr and Freeland Reference Starr and Freeland2024), it cannot be assumed that all women from historically marginalized ethnoracial backgrounds identify as WoC. Thus, a self-identification approach is imperative.

I utilize the 2020 Collaborative Multiracial Post-Election Survey (CMPS) data (Frasure et al. Reference Frasure, Wong, Barreto and Vargas2021) and employ an interdisciplinary and intersectional framework to expand WoC scholarship to include Asian women. Because WoC is a coalitional identity, I compare the attitudes of Asian women to those of Latinas and Black women to examine how WoC identity relates to views on two highly salient and contentious intersectional issues: undocumented immigration and the #MeToo movement. These issues were strategically selected because they directly affect many nonwhite women and often prompt differing responses shaped by one’s ethnoracial and gender identity. For nonwhite women in the United States, both undocumented immigration and the #MeToo movement are deeply intersectional, and attitudes toward them are likely influenced by their lived experiences and positionality (Espiritu Reference Espiritu2008).

I find that a majority of Asian women identify as WoC, and this identity carries political significance. Personal experiences with discrimination and empathy for other marginalized groups play an important role in shaping this coalitional identity for Asians. Compared to other groups, Asian women identify as WoC at much higher rates than Latinas but lower than Black women. Across all three groups, women who adopt the WoC identity report stronger levels of WoC-linked fate than those who do not. However, when attitudes are analyzed by ethnoracial group, the relationship between WoC identity and political attitudes is more limited. WoC-linked fate emerges as a strong and consistent factor, positively associated with both undocumented immigration and the #MeToo movement across all groups. Still, WoC identity remains an important part of this process. As Dawson (Reference Dawson1994) argues in the context of Black linked fate, group consciousness often follows the adoption of shared group identity. Similarly, identifying as a WoC may help lay the groundwork for developing a sense of WoC-linked fate with other women.

Women of Color: Origin, Politics, and Identity

Black feminists began using “Women of Color” in the late 1970s as a political designation to advance the lives of all marginalized women (Combahee River Collective Reference Eisenstein1978; Wade Reference Wade2011). Building on the original term “Person/People of Color” (PoC), which originally referred to individuals of Black and mixed-racial heritage, WoC underscores the interlocking systems of race-gendered oppression that shape non-white women’s experiences (Collins Reference Collins1990; Starr Reference Starr2023; Starr and Freeland Reference Starr and Freeland2024).

The term gained wider visibility during the 1981 National Women’s Studies Association conference, where feminist scholars introduced it to name a “sisterhood that nonwhite women share” and to build a foundation for political solidarity (Sandoval and Anzaldúa Reference Sandoval and Anzaldúa1990). At that time, it was also used interchangeably with the now-outdated term “third world women,” a sociopolitical designation for women of “African, Caribbean, Asian, and Latin American descent, and native peoples of the U.S.” (Mohanty Reference Mohanty1991; Castañeda Reference Castañeda1992). WoC was embraced as an identity grounded in shared experiences of race-gendered discrimination among women from underrepresented ethnoracial groups and signified a sense of belonging, representation, and solidarity in the fight against sexism, racism, and other intersecting forms of oppression (Mohanty Reference Mohanty1991; Sandoval and Anzaldúa Reference Sandoval and Anzaldúa1990; Yamada Reference Yamada, Moraga and Anzaldúa2021; Fujiwara and Roshanravan Reference Fujiwara and Roshanravan2018).

Today, embracing this identity can continue to foster cross-racial solidarity (Collins Reference Collins, Baca Zinn and Dill1994), expressed through empathy for women across racial lines or a sense of linked fate with other WoC. As Lowe (Reference Lowe1991) argues, recognizing internal differences within communities of color creates opportunities to build solidarity with other groups whose unity is shaped by distinct forms of oppression. These “valences of oppression” can serve as bridges uniting historically disadvantaged communities, reinforcing WoC as a coalitional identity. Although this study cannot capture if the contemporary understanding of WoC reflects its feminist origins, feminist theories remain central to my expectations regarding gendered cross-racial solidarity and WoC-linked fate.

Alternatively, women may not feel a sense of solidarity across racial lines due to perceived cultural differences and unequal experiences with discrimination. These divisions can hinder cross-racial solidarity and weaken political cohesion. While women are often treated as a unified political group, research shows that race remains a major dividing line, particularly between white and nonwhite women (Junn and Masuoka, Reference Junn and Masuoka2024; Klar, Reference Klar2018; Huddy, Cassese, and Lizotte, Reference Huddy, Cassese, Lizotte and Whitaker2008) even on gender-related issues (Hansen and Dolan, Reference Hansen and Dolan2023). bell hooks (Reference Hooks1984) argues that “women are divided by sexist attitudes, racism, class privilege, and a host of other prejudices.” Racial discrimination does not affect all women equally, often benefiting some at the expense of others. This dynamic can foster internalized racism or cross-racial hostility, which fuels ingroup division, rather than targeting the oppressive forces that perpetuate the inequality. Harris and Ordoña (Reference Harris, Ordoña and Anzaldúa1990) argue that shared experiences of racism and sexism may not be sufficient to unite nonwhite women. Cross-cutting issues and intersecting social identities, such as class and partisanship, can weaken solidarity (Huddy, Cassese, and Lizotte Reference Huddy, Cassese, Lizotte and Whitaker2008), potentially leading some women to reject the WoC identity and feel little to no sense of WoC-linked fate.

Pérez (Reference Pérez2021) advances the understanding of PoC as an identity rather than solely a descriptive label, using attitudinal measures to capture its significance. While this work contributes important insights to identity politics it does not explore how gender and race/ethnicity work together to influence the “of color” identity, specifically WoC identification.

Matos, Greene, and Sanbonmatsu (Reference Matos, Greene and Sanbonmatsu2021) conducted the first study to assess the political utility of WoC identity, focusing on WoC self-identification, and found that 92% of Black women and 64% of Latinas identify as WoC. They also found that this collective identity emerged as an integral part of individuals’ identity portfolios, shaping their political attitudes. A follow-up analysis, using CMPS data, revealed significantly lower WoC identification rates among Latinas (36%), while rates for Black women remained consistent at 91%, and Asian women emerged at 58% (Greene, Matos, and Sanbonmatsu Reference Greene, Matos and Sanbonmatsu2022).

It is important to note that acknowledging a coalitional identity such as WoC does not negate the distinct racial, panethnic, or national identities of Black, Latina, and Asian women. Rather, it recognizes the systemic barriers and injustices they collectively face. Identities “of color” function as additive and contextual layers, rather than replacements. Pérez (Reference Pérez2021) argues racial, ethnic, and panethnic identities are subsumed within the broader PoC framework.

Asian Americans: History, Diversity, and Racialization

Asian American communities are often treated as a monolithic group, yet they encompass diverse national origins, distinct languages, religions, colonial legacies, and migration histories (Espiritu Reference Espiritu1992; Lien, Conway, and Wong, Reference Lien, Conway and Wong2004; Okamoto Reference Okamoto2014; Ocampo Reference Ocampo2016). These differences also extend to class and phenotype, which may shape how individuals are perceived and racialized in the United States.

Some East Asian groups, such as Chinese and Japanese, have a long-established presence in the United States, with many tracing their roots back several generations. These communities have historically faced exclusion and racial exploitation, including legal barriers to citizenship upheld by the US Supreme Court (Okamoto Reference Okamoto2014; Espiritu Reference Espiritu2008; Lien, Conway, and Wong, Reference Lien, Conway and Wong2004; Haney López Reference López Haney1996). The Page Act of 1875, the first federal immigration law to restrict entry based on race and gender, specifically targeting Chinese women, illustrates how deeply racism and sexism were intertwined and embedded in the country’s earlier immigration policy (Mohanty Reference Mohanty1991; Volpp Reference Volpp2005).

In contrast, South Asians, such as Indians or Pakistanis, immigrated more recently, often through employment-based visa programs that favored applicants with advanced degrees. Many arrived following the 1965 Immigration and Naturalization Act, which prioritized skilled labor and family reunification (Mishra Reference Mishra2016; Zhou and Lee Reference Zhou and Lee2017; Junn Reference Junn2007). Post-1965 Filipino migration, shaped by US colonial ties, included more highly educated and middle-class migrants compared to earlier waves (Ocampo Reference Ocampo2016). Meanwhile, other Southeast Asians, such as Cambodians or Vietnamese, arrived as refugees with limited resources and faced significant structural barriers (ⓞng and Meyer Reference ⓞng and Meyer2008).

Asian American communities also exhibit significant religious diversity. Some South Asians have strong ties to Hinduism or Islam (Naber Reference Naber2012; Mishra Reference Mishra2016), while Filipino Americans are predominantly Catholic due to Spanish colonialism (Ocampo Reference Ocampo2016). About one in five Asians identify as Buddhist, and 34% as Christian, with 10% identifying as born-again or Evangelical. In contrast, more than half of Chinese and nearly half of Japanese are religiously unaffiliated (Mohamed and Rotolo Reference Mohamed and Rotolo2023). For many, religion serves as a source of identity and cultural connection that can shape their political attitudes. Wong (Reference Wong2018), for example, finds that while Evangelicals generally hold conservative views, Asian Evangelicals diverge sharply from their white counterparts on issues such as immigration and the Black Lives Matter movement, with whites reporting more than twice the level of opposition.

Religion can also be a source of discrimination. For instance, hijab-wearing Asian Muslim women face unique forms of bias shaped by their nonwhiteness, gender, and visible religious affiliation, with the hijab serving as an external marker of difference (Dana et al. Reference Dana, Lajevardi, Oskooii and Walker2019; Sediqe Reference Sediqe2023). These experiences can foster a coalition between Asian women and other nonwhite women, resulting in a WoC identity.

Despite their diversity, Asian Americans share a collective history of exclusion, exploitation, and racial discrimination (Ngai Reference Ngai2014; Espiritu Reference Espiritu1992, Reference Espiritu2008; Volpp Reference Volpp2005). Said’s concept of Orientalism provides a framework for understanding how Asian Americans have been constructed as perpetual outsiders (Said Reference Said2014). In the United States, this racialization as “the other,” combined with geopolitical events or moments of crisis, helps explain why certain Asian subgroups face heightened discrimination at particular moments. The portrayal of Asian Americans as “yellow peril” or threatening outsiders was deliberately propagated in the late 19th century and continues to persist (Junn Reference Junn2007). White Americans used this narrative and other “controlling images” to justify exclusionary policies, casting Chinese and Japanese immigrants as culturally inferior, incompatible with American republican ideals, and as an economic threat due to their perceived association as cheap laborers (Espiritu Reference Espiritu2008; Volpp Reference Volpp2005; Matthews Reference Matthews1964). During World War II, Japanese Americans were racially profiled and forcibly incarcerated, with over 120,000 placed in internment camps under Executive Order 9066 (National Archives and Administration Records 1942).

The post-1965 influx of highly resourced Asian immigrants contributed to the rise of the “model minority” myth, which obscures the structural disadvantages faced by less affluent Asian subgroups. This trope portrays Asians as hardworking, model citizens who achieve the “American Dream” through educational attainment and income, often in contrast to other underrepresented and marginalized groups (Mishra Reference Mishra2016; Wong et al. Reference Wong, Lai, Nagasawa and Lin1998; Zhou and Lee Reference Zhou and Lee2017). This stereotype gained traction during the Civil Rights Movement and was used to create division between nonwhite groups. Asian Americans were often contrasted with Black Americans, who were stereotyped as less successful and more prone to social dysfunction (Kim Reference Kim2004). This narrative reinforced white supremacy and anti-Black racism by suggesting that systemic inequality could be overcome through individual effort (Fujiwara and Roshanravan Reference Fujiwara and Roshanravan2018; Lien Reference Lien2001; Wong et al. Reference Wong, Lai, Nagasawa and Lin1998). Ultimately, it obscures structural barriers, promotes a false narrative of universal success, and erases the diversity of experiences within Asian American communities. (Mishra Reference Mishra2016; Espiritu Reference Espiritu1992; Lien Reference Lien2001; Lowe Reference Lowe1991).

In the aftermath of 9/11, South Asians, particularly Muslims and Sikhs, faced heightened surveillance and racial profiling (Cainkar Reference Cainkar2002; Mishra Reference Mishra2016). Anti-Muslim sentiment increased again in 2016, fueled by Trump’s rhetoric and his administration’s attempt to implement a Muslim ban (Calfano, Lajevardi, and Michelson Reference Calfano, Lajevardi and Michelson2017). More recently, during the COVID-19 pandemic, anti-Asian sentiment and violence increased, with Chinese and other East Asians scapegoated for the virus (Kelley Reference Kelley2020; Hua and Junn Reference Hua and Junn2020; Lee and Ramakrishnan Reference Lee and Ramakrishnan2022). These examples illustrate that the racialization of Asian Americans is neither static nor uniform but shaped by shifting geopolitical conditions and domestic political narratives. They also reflect the paradoxical and conflicted relationship the United States has with Asian Americans.

Asian American communities have long been affected by the United States’ racial hierarchy. This hierarchy, rooted in the ideology of white supremacy, systematically privileges whiteness across legal, social, and political domains (Masuoka and Junn Reference Masuoka and Junn2013; Bonilla-Silva Reference Bonilla-Silva2004; Haney López Reference López Haney1996; Omi and Winant Reference Omi and Winant1994). Dominant racial discourse historically centered on a Black-white binary overlooking the racialization of Asian Americans until Kim (Reference Kim1999) introduced a theory of racial triangulation. This theory illustrates how Asian Americans occupy a precarious position, viewed as socially superior to Blacks but inferior to whites, while also perceived as outsiders/foreigners relative to both. Kim’s theory aligns with Espiritu’s (Reference Espiritu2008) argument that race-gendered immigration policies, along with labor market dynamics, have historically positioned Asian Americans in a subordinate role within U.S. society. Building on Kim’s theory of racial triangulation, Masuoka and Junn (Reference Masuoka and Junn2013) conceptualize a racial prism that reflects the hierarchical positioning of the largest ethnoracial groups in the United States: white, Black, Asian, and Latino. In their framework, whites remain at the top. Asians are positioned below whites due to their perceived socioeconomic success yet continue to be racialized as perpetual foreigners. Latinos fall below Asians due to factors such as immigration status and class and Black Americans remain at the bottom, reflecting the enduring legacy of systemic anti-Black racism.

Hypotheses

Building on existing interdisciplinary scholarship, this study examines whether Asian women identify as WoC and how that identity informs their political attitudes. Through a comparative analysis of Asian, Latina, and Black women, I provide a nuanced understanding of this coalitional identity and its association with attitudes towards undocumented immigrants and the #MeToo movement. The following section outlines the specific hypotheses guiding this analysis, grounded in prior research on identity formation, linked fate, and intersectional political behavior.

A growing body of research finds that experiences with discrimination shape collective identity formation. Masuoka (Reference Masuoka2006) finds that racial discrimination strengthens panethnic identity among Asian Americans, while Golash-Boza (Reference Golash-Boza2006) and Schildkraut (Reference Schildkraut2005) find similar effects for Latinos. Oskooii (Reference Oskooii2016, Reference Oskooii2018) demonstrates that perceived societal or political discrimination increases in-group identification. For Asian American women, who often face intersectional race-gendered marginalization, these experiences may heighten identification with coalitional identities, such as WoC. Even in the absence of direct experience, beliefs about the persistence of gender discrimination and empathy toward other marginalized groups may further reinforce the adoption of this identity.

H1a: Asian women who report greater personal experiences with discrimination will be more likely to identify as WoC.

The term WoC and similar “of color” identifiers are especially salient within the United States. These terms frequently appear in headlines surrounding election outcomes, representation, and the political behavior of racially diverse women (Deliso Reference Deliso2021). Because WoC is rooted in U.S.-based, English-language contexts, it may be less familiar to foreign-born Asian women, particularly those who immigrated as adults or were socialized in predominately non-English-speaking environments. In contrast, U.S.-born Asian women are more likely to be raised in multicultural, multiracial contexts where panethnic and coalitional identities like WoC are more visible and politically relevant.

H1b: U.S.-born Asian women will be more likely to identify as WoC compared to foreign-born Asian women.

College campuses often support “student of color” organizations to promote the inclusion, representation, and well-being of nonwhite students, which could familiarize them with “of color” terminology. Higher education also increases opportunities to engage with peers from diverse ethnoracial backgrounds, develop awareness of historical and contemporary social movements, and encounter political discourse around race and gender. Starr and Freeland (Reference Starr and Freeland2024) find that younger and highly educated Asian Americans are more likely to identify as PoC. Given these theoretical expectations and recent findings, my next two hypotheses are:

H1c: Younger Asian women will be more likely to identify as WoC than older Asian women.

H1d: Higher-educated Asian women will be more likely to identify as WoC than less-educated Asian women.

Intersectionality: WoC Identity and WoC-Linked Fate

Intersectionality is a widely used theoretical framework and methodological approach for understanding how identities, such as race/ethnicity, gender, sexuality, class, and religion, shape experiences with marginalization (Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1989; Collins Reference Collins, Baca Zinn and Dill1994; Hancock Reference Hancock2007). It also allows scholars to examine how multiple identities influence political attitudes. Nonwhite women navigate both racial and gender discrimination, whereas white women, despite experiencing sexism, still benefit from racial privilege. Accordingly, their societal position is described as “second in sex, but first in race” (Junn Reference Junn2017; Frasure-Yokley Reference Frasure-Yokley2018). These intersecting identities can foster group consciousness and invoke a sense of WoC-linked fate (Campi and Junn Reference Campi and Junn2019; Carey and Lizotte Reference Carey and Mary-Kate2023).

Group consciousness refers to an in-group identity politicized by a shared understanding of the group’s social position and a belief that collective action is the best method to advance the group’s interests (McClain et al. Reference McClain, Johnson Carew, Walton and Watts2009). Based on this concept, Dawson (Reference Dawson1994) introduced the Black utility heuristic, or linked fate, to explain the persistence of Black political unity despite class differences. Linked fate is the belief that one’s personal well-being is directly connected to the outcome of one’s racial group.

While Dawson’s concept of linked fate has been tested among other racial and panethnic groups, scholars have found that it tends to be situational and not as persistent as it is with Black Americans (Le, Arora, and Stout Reference Le, Arora and Stout2020; Junn and Masuoka Reference Junn and Masuoka2008; Sanchez and Masuoka Reference Sanchez and Masuoka2010; Sanchez and Vargas Reference Sanchez and Vargas2016; Gay, Hochschild, and White Reference Gay, Hochschild and White2016). In addition to group-based linked fate, other research examines whether nonwhite groups perceive any cross-racial political commonality and find that when it exists, it is often rooted in shared experiences of discrimination (Lu, Reference Lu2020; Craig and Richeson, Reference Craig and Richeson2012; Sanchez Reference Sanchez2008).

For nonwhite women, who face double marginalization (Simien Reference Simien2005), group consciousness may take the form of intersectional or WoC-linked fate (Gershon et al. Reference Gershon, Montoya, Bejarano and Brown2019). Carey and Lizotte (Reference Carey and Mary-Kate2023) show that WoC-linked fate influences the policy preferences of Black, Latina, and Asian American/Pacific Islander women, though they classify all respondents from these groups as WoC for the purposes of their analysis. In contrast, given the politicized and historical roots of this coalitional identity, I follow the approach used by Matos, Greene, and Sanbonmatsu (Reference Matos, Greene and Sanbonmatsu2021) in using the self-identification measure for WoC. Building on Dawson’s framework, I argue that WoC-linked fate begins first with identifying as a Woman of Color. This identification provides the foundation for recognizing shared race-gendered experiences and promotes solidarity. WoC-linked fate reflects a shared understanding of what it means to be a woman from a marginalized racial group in the United States and, more importantly, the recognition that what happens to other nonwhite women can directly affect one’s own life.

To better understand the positioning of Asian women within the WoC collective, a comparative approach is necessary. I compare levels of WoC identity (WoC ID) among Asian, Black, and Latina women. Given the historical origins of WoC and recent scholarship, Black women are expected to report the highest levels of WoC identity (Matos, Greene, and Sanbonmatsu Reference Matos, Greene and Sanbonmatsu2021; Greene, Matos, and Sanbonmatsu Reference Greene, Matos and Sanbonmatsu2022; Pérez Reference Pérez2021; Starr and Freeland Reference Starr and Freeland2024). In contrast, both Asian and Latina women are expected to report lower levels of WoC identification than Black women. This expectation aligns with Masuoka and Junn’s (Reference Masuoka and Junn2013) racial prism model, which positions Asians and Latinos at similar levels within the U.S. racial hierarchy. Because both groups occupy an amibiguous position—neither fully included nor fully excluded from dominant racial boundaries—their levels of WoC identification are expected to be comparable. Based on these theoretical expectations and findings, my next hypothesis is:

H2: Asian women will be less likely to identify as WoC compared to Black women but at a relatively equal level with Latinas.

The first political attitude I examine is support for undocumented immigrants, which is primarily an ethnoracial issue but carries important gendered implications (Mohanty Reference Mohanty1991; Hondagnue-Sotelo Reference Hondagnue-Sotelo2003; Pessar Reference Pessar2003). Asian, Black, and Latina women experience race- and gender-based discrimination in distinct ways (Harris and Ordoña Reference Harris, Ordoña and Anzaldúa1990), and based on these experiences and their social positioning, they may form differing opinions on immigration related issues. While each group faces certain challenges, these experiences may foster a sense of cross-group empathy.

For example, Asians and Latinas/os are often perceived as “immigrant groups” due to their closer ties to recent immigration and naturalization processes, unlike Black Americans, who have a longer-standing history in the United States and are overwhelmingly U.S.-born. Both Asians and Latinas/os are subjected to the “perpetual foreigner” stereotype (Kim Reference Kim1999; Volpp Reference Volpp2005). However, their experiences differ. Many Asian immigrants enter through legal channels, with pathways to citizenship (Junn Reference Junn2007; Zhou and Lee Reference Zhou and Lee2017), unlike many Latinas/os, whose migration is often perceived as “illegal” due to higher rates of undocumented entry (Millet and Pavilon Reference Millet and Pavilon2022; Moslimani and Noé-Bustamante Reference Moslimani and Noé-Bustamante2023). These differing migration patterns likely influence women’s attitudes towards those without documentation.

In addition, gender shapes views on immigration (Corral Reference Corral2023; Lavariega Monforti Reference Monforti2017; Bejarano, Manzano, and Montoya Reference Bejarano, Manzano and Montoya2011; Bedolla, Monforti, and Pantoja Reference Bedolla, Monforti and Pantoja2006). Women, particularly Latinas, are less likely than men to support restrictive immigration policies, including increased surveillance of immigrants and police involvement in the enforcement of immigration laws (Corral Reference Corral2023). Based on these theoretical expectations and findings, my next hypothesis is:

H3a: Self-identified WoC will feel more warmly towards undocumented immigrants compared to women who do not identify as a WoC.

The second issue I examine is related to gender-based exploitation and advocacy: the #MeToo movement, which is primarily a gender-related issue but has ethnoracial implications. According to the CDC, sexual violence overwhelmingly impacts women, particularly nonwhite women, as they are at greatest risk for sexual violence in the United States (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2004). The movement was founded by activist Tarana Burke, a Black woman, to raise awareness of the widespread yet often underreported and overlooked epidemic of sexual harassment and assault experienced by women and girls (Me Too Movement 2025). This movement initially developed within community-based work and later gained international visibility through its spread on social media platforms (i.e., Twitter, Facebook), launching almost concurrently with the 2017 Women’s March (Radu Reference Radu2017). What began as an awareness campaign grew into a broader call for accountability and a resource for survivors. The movement’s focus is to support those most vulnerable: Black women and girls and communities of color. Given the salience of this movement and its relevance to racially diverse women, my final hypothesis is:

H3b: Self-identified WoC will feel more warmly towards the #MeToo movement compared to women who do not identify as WoC.

Methods and Data

The 2020 CMPS data allows for an intersectional analysis by gender and ethnoracial identity, with relevant measures of WoC identity and WoC-linked fate, along with political attitudes and demographic variables. The analysis includes 1,950 Asian, 1,774 Latina, and 2,469 Black women.

I begin by focusing on Asian women and present descriptive statistics, followed by multivariate regression models that assess which factors predict adopting a WoC identity. The analysis includes three discrimination-related measures: (1) Discrimination Experience—a composite index capturing personal experiences with discrimination, the salience of those experiences, and their perceived impact. Respondents were coded as 1 if they (a) reported experiencing discrimination, (b) attributed it to a relevant identity, and (c) reported that these discriminatory experiences had interfered with their life. All others were coded as 0; (2) Discrimination Beliefs—captures respondents’ beliefs about ongoing gender discrimination in society; and (3) Empathy—reflects solidarity with and concern for other marginalized groups.

Control variables include age, education, income, nativity, ethnicity, partisanship, ideology, skin tone, and region. Skin tone was measured using a 1–10 visual scale, where 1 represents the lightest and 10 the darkest skin color, and was recoded into three categories: Light (1–3), Medium (4–6), and Dark (7–10). Ethnicity was measured using the Asian ethnicity instrument, which included 15 national-origin subgroups plus “Other.” To ensure accurate modeling and adequate sample size, respondents identifying as Pacific Islander (n = 1) and Iranian (n = 2) were excluded. To preserve valuable Southeast Asian representation, I combined Thai (n = 23), Cambodian (n = 17), Hmong (n = 9), and Lao (n = 4) into a single, though still small, “Other Southeast Asian” category. The “Other” category was also excluded from the analysis due to its lack of specificity, which limits its usefulness for assessing the role ethnicity plays in adopting a WoC identity. The analysis therefore includes Chinese, Indian, Filipino, Korean, Japanese, Vietnamese, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Taiwanese, and other SE Asian.

Next, I compare attitudes across groups and assess how the WoC identity relates to support for undocumented immigrants and the #MeToo movement. These attitudes are measured using feeling thermometers ranging from 0 (cold) to 100 (warm). WoC Identity (WoC ID) serves as the primary independent variable in the linear regression models that control for the aforementioned covariates. I estimate models for the pooled sample as well as separately for each ethnoracial group.

Additional models examining racial-linked fate, gendered linked fate, and their interaction (race-gender linked fate) were estimated as robustness checks to assess whether these forms of group consciousness behave similarly to WoC-linked fate. None of these models yielded statistically significant results, and because they do not alter the substantive interpretation of the findings, they are not presented.

Results: Asian Women WoC

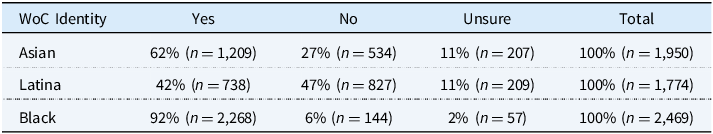

When asked, “Do you think of yourself as a woman of color?”, an overwhelming majority responded “Yes.” As shown in Table 1, 62% of Asian women identified as WoC. The proportion is consistent with recent findings on Asian WoC identification (58%; Greene, Matos, and Sanbonmatsu Reference Greene, Matos and Sanbonmatsu2022), as well as estimates for Asian PoC at 61% (Starr and Freeland Reference Starr and Freeland2024) and 63% (Lee and Sheng Reference Lee and Sheng2024). For the remainder of the analyses, I collapsed the “No” and “Unsure” responses into a single category (“Non-WoC ID”) since an “unsure” response does not indicate identification as WoC.

Table 1. Percentage of woman of color identity by ethnoracial group

Source: 2020 Comparative Multiracial Post-Election Survey, UCLA.

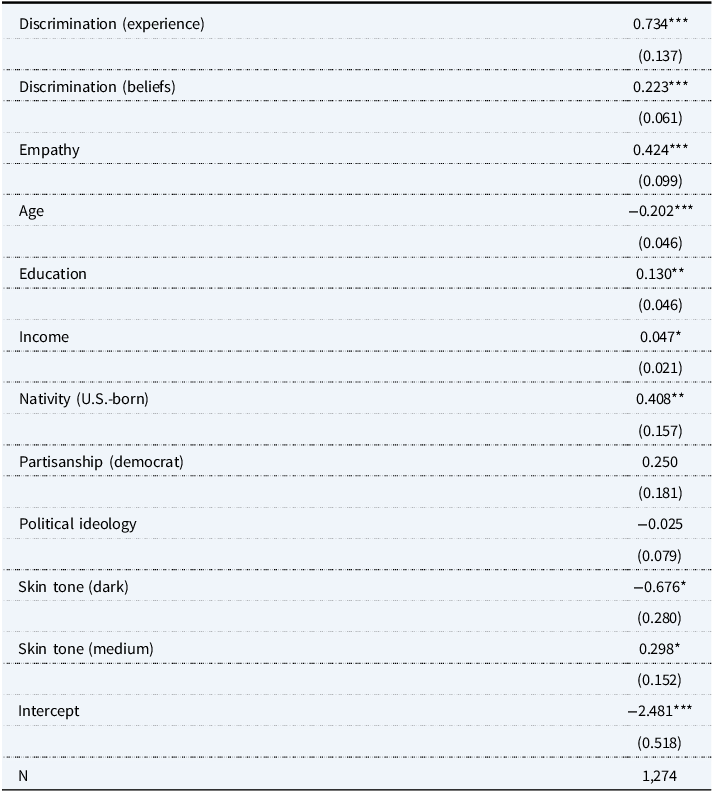

Personal experiences with discrimination emerge as one of the strongest factors shaping WoC identification among Asian women. As shown in Table 2, women who reported being personally discriminated against, as captured by the Discrimination Experience composite index, were more likely to adopt a WoC identity. This measure reflects not only direct experiences with discrimination but also whether respondents attributed those experiences to their racial or gender identity and felt that discrimination interfered with their lives. In addition to lived experiences, attitudinal measures also matter. Women who believe gender discrimination remains a societal problem and those who expressed greater empathy toward other marginalized groups are also more likely to identify as WoC.

Table 2. Woman of color identity (Asian Women)

Source: 2020 Comparative Multiracial Post-Election Survey, UCLA.

Note: The dependent variable in the logistic regression model is WoC identity (coded 0 = no,1 = yes).

Standard errors in parentheses. Survey sampling weights were incorporated into the analysis.

* p ≤.05, **p ≤ .01, ***p ≤ .001.

Turning to the demographic variables, several patterns emerge that shed light on how factors such as nativity, education, and income relate to the adoption of this identity (Table 2). As hypothesized (H1b), nativity is an important factor, with U.S.-born women more likely to identify as WoC than their foreign-born counterparts. Age also shapes WoC identity formation, supporting H1c, with younger Asian women more likely to identify as WoC. Descriptively, nearly half (49%) of Asian women who identify as WoC are under 40, compared to 35% between ages 40 and 59, and just 16% over 60 years old. Consistent with H1d, higher levels of education are associated with WoC identification. This relationship remains even when controlling for income, which is also positively associated with WoC identity.

Although the regression model does not reveal a statistically significant relationship between partisanship or ideology and the WoC identity, the descriptive data show a clear partisan divide. Among Asian women, those who identify as WoC are not only more likely to identify as Democrats (62%) and less likely to identify as Republicans (11%), but they are also more likely to hold liberal political views. Nearly half (48%) of WoC-identifying Asian women report being liberal, while only 14% identify as conservative.

Given the emphasis on “color” in “Women of Color” and the established role of phenotypical features in shaping racialized experiences, skin tone was included as a variable to assess whether visible markers of racial difference influence the adoption of WoC identity. This consideration is especially relevant for Asian women, a highly diverse group encompassing a wide range of ethnicities and phenotypes. While East Asian women are often associated with lighter skin tones, many South and Southeast Asian women may have darker complexions. As shown in Table 2, women with medium skin tones are more likely than those with light skin tones to identify as WoC, whereas women with darker complexions are significantly less likely to do so. Descriptively, WoC identification is highest among Asian women with medium (64%) and light (62%) skin tones, while nearly half (48%) of Asian women with darker complexions do not identify as WoC (Appendix Figure 1).

Lastly, to determine whether ethnicity influences WoC identity, given the considerable diversity among Asian women in the United States, I examined variation across subgroups. Ethnicity did not yield statistically significant differences for most groups (Appendix Table A1). The only exception is the “Other SE Asian” category, which shows a positive and statistically significant association (b = 1.560, p < 0.01). This finding should be interpreted with caution, however, given the small sample size of this combined subgroup (n = 53), representing only 2.7% of the Asian women in the sample. Descriptively, WoC identification rates range from 55 to 79% across ethnic groups (Appendix Figure 2).

Additional variables, including geographic region, were tested but were not statistically significant; full results are reported in Appendix Table A1.

Results: Comparative Analysis of Asian, Latina, and Black Women

I conducted a comparative analysis of Asian, Latina, and Black women for two reasons. First, it situates Asian women within the broader landscape of WoC identity politics, which has predominantly focused on Black and Latina women. Second, because WoC is a collective identity, comparing these groups reveals both intra-group variation and differences between women who identify as WoC and those who do not.

WoC Identity and WoC-Linked Fate

Consistent with my expectations, Asian women were less likely than Black women to identify as women of color, at rates of 62% and 92%, respectively. However, the proportion of Latinas adopting this identity (42%) was lower than anticipated (Table 1).

To assess how identifying as a WoC influences WoC-linked fate, I used the survey question: “How much do you think what happens to women of color here in the U.S. will have something to do with what happens in YOUR life?”. Responses ranged from 1 (Nothing) to 5 (A huge amount). For the analysis, I collapsed these into three categories: 1 = Little/Nothing, 2 = Something, and 3 = A Lot/Huge Amount. This measure also allows comparison between WoC and non-WoC identifiers.

Descriptively, a strong sense of WoC-linked fate is reported by 83% of Asian women, 79% of Latinas, and 85% of Black women who identify as WoC (Appendix Table A2). In contrast, Non-WoC identifiers exhibit significantly lower levels of linked fate, with only 38 to 47% reporting little to no WoC-linked fate.

Feelings towards Undocumented Immigrants

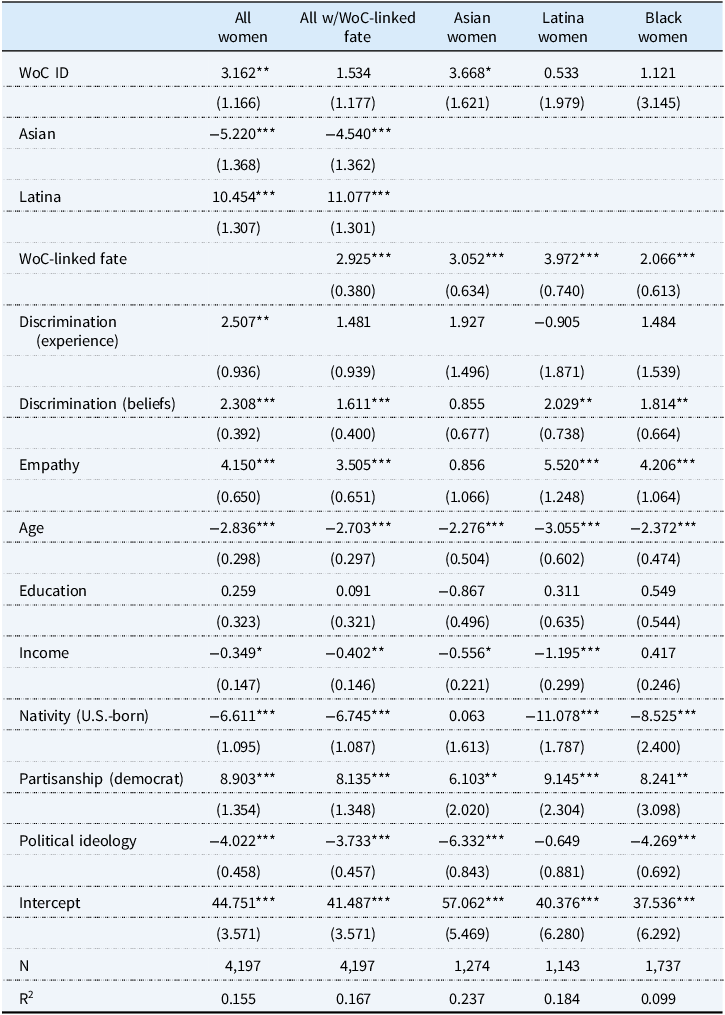

I ran a series of multivariate analyses to examine the relationship between WoC identification and support for undocumented individuals, using the feeling thermometer as the outcome measure. WoC ID is the primary independent variable, with models controlling for nativity, partisanship, discrimination, and other demographic factors. Results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Support for undocumented immigrants

Source: 2020 Comparative Multiracial Post-Election Survey, UCLA.

Note: The dependent variable in the linear regression model is feeling towards Undocumented Immigrants. Feelings towards this group are coded on a scale from 0–100, from “very cold” to “very warm”.

Standard errors in parentheses. Survey sampling weights were incorporated into the analysis.

* p ≤.05, **p ≤ .01, ***p ≤ .001.

As shown in Column 1 (pooled model), identifying as a WoC is positively associated with warmer feelings toward people without legal status, partially supporting my hypothesis (H3a). However, when disaggregated by ethnoracial group (Columns 3–5), the relationship remains positive for all three groups but statistically significant only among Asian women. In contrast, WoC-linked fate shows a strong and significant association with support for undocumented individuals in the pooled sample and across all three groups (Columns 2–5).

To better understand this pattern, I included the three discrimination-related variables in the model. Surprisingly, personal experiences with discrimination do not influence support for those in the United States without documentation for any group. However, beliefs about societal gender-based discrimination and empathy for other marginalized communities are positively associated with support across all three groups, although these relationships reach statistical significance only for Latina and Black women.

Demographic factors also shape attitudes toward undocumented immigrants. Age is a consistent and significant predictor across all models, with older women less likely to support unauthorized immigrants than their younger counterparts. In contrast, education does not appear to be related to support for individuals without legal status in either the pooled model or the group-specific models. Income, however, shows variation across groups. Among Asian women and Latinas, higher income is significantly associated with lower support for undocumented individuals. For Black women, the relationship is in the opposite direction, though not statistically significant (Columns 3–5).

Partisanship and ideology are strongly associated with support for people without legal status. As anticipated, identifying as a Democrat and holding more liberal views (indicated by negative coefficients in Table 3) are linked to warmer feelings towards individuals who came to the United States without documentation. This pattern generally holds across disaggregated models and aligns with recent research (Sanbonmatsu, Greene, and Matos Reference Sanbonmatsu, Greene and Matos2025). Among Latinas (Column 4), liberal ideology is positively associated with support but does not reach statistical significance. The direction of the effect remains consistent, suggesting ideology still plays a role, even if the relationship is weaker.

Finally, nativity also influences support for undocumented individuals. In the pooled model (Columns 1 and 2), U.S.-born women express significantly less support for this group compared to foreign-born women. In the disaggregated models, this pattern holds for Latina and Black women but not for Asian women, among whom nativity shows no significant effect.

Feelings towards the #MeToo Movement

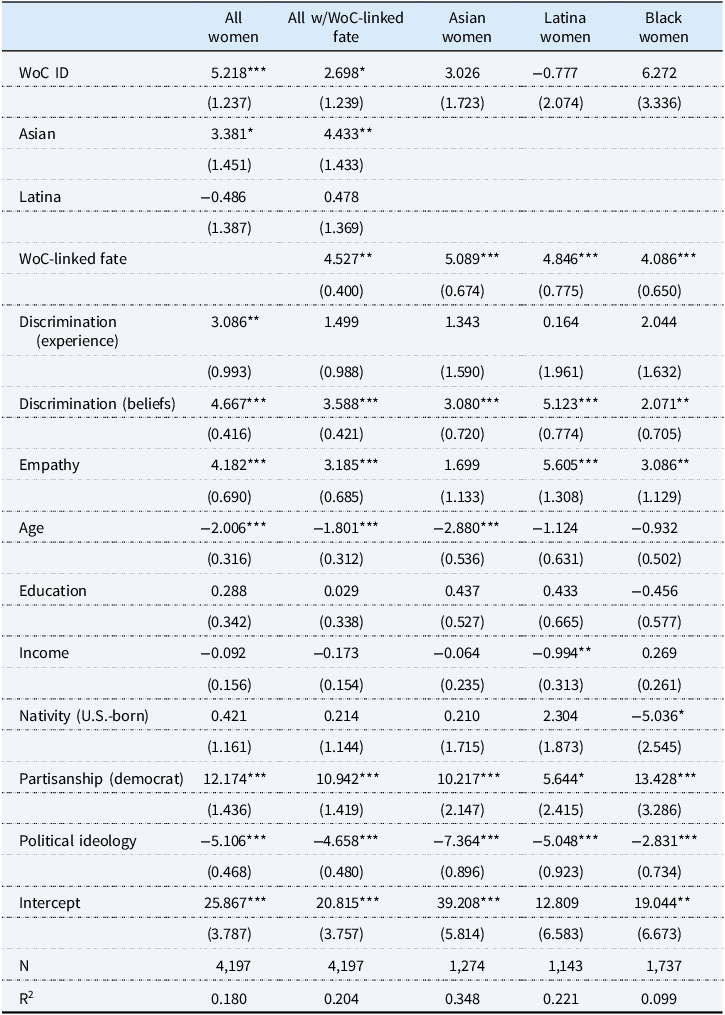

To assess support for the #MeToo movement, I ran a series of multivariate regression models using the feeling thermometer as the dependent variable and a binary measure of WoC identity (WoC ID) as the main independent variable. All models include the same control variables used previously. Results are shown in Table 4.

Table 4. Support for #MeToo movement

Source: 2020 Comparative Multiracial Post-Election Survey, UCLA.

Note: The dependent variable in the linear regression model is feeling towards the #MeToo Movement. Feelings towards this group are coded on a scale from 0 to 100, from “very cold” to “very warm.”

Standard errors in parentheses. Survey sampling weights were incorporated into the analysis.

* p ≤.05, **p ≤ .01, ***p ≤ .001.

WoC identification is associated with warmer feelings toward the movement in the pooled model, although this relationship does not hold across the group-specific models; it is consistent with recent research on WoC identity and liberal attitudes (Sanbonmatsu, Greene, and Matos Reference Sanbonmatsu, Greene and Matos2025). In contrast, WoC-linked fate shows a strong and statistically significant association with support for #MeToo in both the pooled sample (Column 2) and across all three groups (Columns 3–5).

Next, I examined the relationship between the three discrimination-related variables and attitudes toward #MeToo. As with earlier models, there is no evidence that experiencing discrimination is associated with support for #MeToo in any group. However, believing that gender-based discrimination remains a societal problem is positively associated with support for the movement. Empathy toward other underrepresented communities shows mixed effects; although it is positive for all groups, the relationship reaches statistical significance for only Latina and Black women.

Demographic factors also show mixed effects. In terms of age, older women are less supportive of the movement than younger women. This relationship holds in the pooled models and across all three groups, although it does not reach statistical significance for Latinas and Black women. Education is not significantly related to support in any model. As shown in Table 4, income effects vary across ethnoracial groups. Income is not significantly associated with support for #MeToo among Asian or Black women, though the direction of the relationship differs. In contrast, income is significantly and negatively associated with support among Latinas, suggesting that higher-income Latinas express lower levels of support for #MeToo.

Political orientation is strongly associated with attitudes toward #MeToo. As expected, across all models, identifying as a Democrat and holding more liberal ideological views are consistently linked to more favorable attitudes of the #MeToo movement.

Lastly, the relationship between nativity and support for the #MeToo movement varies across groups. Among Asian and Latina women, nativity is positively associated with support but is not statistically significant. For Black women, however, U.S.-born respondents express significantly less support for #MeToo than their foreign-born counterparts.

Discussion

A majority of Asian American women in the sample (62%) identify as WoC, and this identity is politically meaningful. Those who adopt this identity also report a stronger sense of WoC-linked fate compared to those who do not. One of the most significant findings is the role discrimination plays in shaping this identity. Personal experiences of identity-based discrimination (as measured by the Discrimination Experience index), beliefs about societal gender-based discrimination, and having empathy for other marginalized groups are all positively and significantly associated with identifying as WoC. Taken together, these findings suggest that WoC identity among Asian women is not only shaped by personal experiences of discrimination but also by beliefs about structural inequality and solidarity with other marginalized communities.

In addition to discrimination-related factors, several demographic characteristics are related to WoC identification among Asian women. Consistent with my hypotheses, nativity, age, and education all influence the formation of the WoC identity. Specifically, being U.S.-born, younger, and having a college education are all positively associated with adopting this identity. These patterns suggest that exposure to U.S.-based racial discourse—particularly through educational settings and media—may heighten the salience of the term “woman of color.” Higher levels of education may also create more opportunities for interaction with interracial peers and engagement with race- or gender-based social movements, further reinforcing identification with the WoC identity. Ethnicity, however, showed no statistically significant effect on the WoC identity. Descriptively, the majority of Asian women across ethnic groups identified as a WoC, with rates ranging from 55 to 79%. Skin tone also did not consistently shape WoC identity formation. While Asian women with medium skin tones were slightly more likely to adopt the identity than those with lighter skin, women with darker complexions were significantly less likely to do so. These findings suggest that for Asian women, the “of color” component of WoC identity may signal nonwhite racial status and shared marginalization rather than skin tone.

Lastly, while partisanship and ideology did not show a statistically significant relationship with WoC identity in the regression models, the descriptive data reveal meaningful patterns. WoC-identifying Asian women are more likely to be Democrats and hold liberal views and less likely to be Republican or conservative. These patterns suggest a broader alignment between WoC identity and progressive political orientation, consistent with research linking PoC identification to liberal views (Starr and Freeland Reference Starr and Freeland2024). This alignment also reflects the term’s origins as a coalitional identity grounded in progressive movements.

To better understand how Asian women position themselves within WoC politics, I compared their attitudes to those of Latina and Black women on two salient race-gendered issues: undocumented immigration and the #MeToo movement.

Starting with WoC identification, Asian women (62%) identify at lower rates than Black women (92%) but at significantly higher rates than Latinas (42%). This pattern aligns with recent research on PoC and WoC identity development, which finds that Latinas identify with “of color” identities at lower rates than Black Americans (Pérez Reference Pérez2021; Starr and Freeland Reference Starr and Freeland2024; Lee and Sheng Reference Lee and Sheng2024; Greene, Matos, and Sanbonmatsu Reference Greene, Matos and Sanbonmatsu2022). Notably, the 20-point gap between Asian and Latina women underscores important variation in how historically marginalized groups engage with this collective identity.

The timing of the 2020 CMPS may help contextualize these findings. The survey was conducted during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, a period marked by rising anti-Asian racism, xenophobia, and violence. This heightened racialization may have increased Asian women’s awareness of their marginalized status and strengthened identification with this coalitional identity. Starr and Freeland (Reference Starr and Freeland2024) similarly suggest that pandemic-era racial targeting likely contributed to higher rates of PoC identification among Asian Americans compared to Latinos during this time.

While the timing of the 2020 survey may help explain higher rates of WoC identification among Asian women, it does not fully account for the lower rates among Latinas. This disparity likely reflects deeper structural and sociopolitical dynamics. Although Latinas also face race-gendered discrimination, these issues may have been less salient during the survey period. Additionally, experience with discrimination can vary across national-origin groups depending on physical appearance. Many Latinas have European ancestry and physical traits that allow them to be perceived as white (even if they do not identify as such), which may reduce exposure to overt racial discrimination compared to Asian or Black women (Golash-Boza Reference Golash-Boza2006). In contrast, Asians and Blacks often have more visibly distinct features that can be racialized at first sight (Junn and Masuoka Reference Junn and Masuoka2008).

Across all three groups, WoC-linked fate tends to correspond with WoC identification, with the vast majority of Asian, Latina, and Black women who identify as WoC reporting a strong sense of intersectional linked fate. While not a prerequisite, this pattern follows the logic of Black linked fate, in which group consciousness is activated only after one adopts a shared group identity (Dawson Reference Dawson1994). Importantly, WoC-linked fate is conceptually distinct from both racial and gender-linked fate. Additional models testing racial-linked fate (within each ethnoracial group), gender-linked fate, and their interaction (race-gendered linked fate) were estimated but did not yield statistically significant results and are therefore not presented.

To understand the broader implications of these findings, it is important to consider how WoC identity and WoC-linked fate shape political attitudes toward undocumented immigration and the #MeToo movement. In the pooled sample, identifying as a WOC is positively associated with support for both undocumented individuals and the #MeToo movement. However, when disaggregated by ethnoracial group, this relationship holds only for Asian women in the case of immigration and is not statistically significant for any group with respect to #MeToo.

In contrast, WoC-linked fate shows a strong and significant relationship across all three groups for both outcomes. These findings suggest that a sense of shared fate with other women is more politically salient than adopting the WoC identity itself. Rather than identity alone, it is WoC-linked fate that appears most politically salient. Some women may feel this connection and the belief that the experiences and outcomes of other women of color are intertwined with their own even if they do not explicitly identify as WoC. Overall, this pattern aligns with recent scholarship on WoC-linked fate suggesting that shared experiences of race-gendered marginalization foster political unity on certain issues (Campi and Junn Reference Campi and Junn2019; Carey and Lizotte Reference Carey and Mary-Kate2023).

The role of discrimination in shaping support for undocumented individuals and the #MeToo movement presents a mixed pattern. Personal experiences of discrimination were not significantly associated with support for either issue across any group, a somewhat unexpected result, given the strong role this variable had on predicting WoC identity among Asian women. In contrast, perceiving gender-based discrimination as a societal problem was positively related to support for both issues. For attitudes towards the #MeToo movement, the relationship between gender discrimination beliefs aligns with the movement’s emphasis on gender-based injustice. Similarly, empathy toward other disadvantaged communities was positively related with support, though it reached statistical significance only for Black and Latina women. The absence of a significant relationship among Asian women does not suggest a lack of empathy but may reflect differences in how these feelings are activated or translated into policy attitudes. Overall, these findings suggest the presence of a WoC sisterhood, reflected in the positive relationship between empathy and beliefs about gender-based discrimination and support for both issues, as measured by the feeling thermometers.

Certain demographic factors also influenced attitudes toward both issues. Older women were generally less supportive of both undocumented immigrants and the #MeToo movement, a pattern consistent across groups. This may reflect broader trends in political behavior research, which suggests that when political attitudes shift, they tend to become more conservative with age (Peterson, Smith, and Hibbing Reference Peterson, Smith and Hibbing2020). Education, by contrast, showed no meaningful relationship to either issue.

Income trended in the same direction across all three groups for both issues. Among Asian women and Latinas, higher income was associated with colder feelings towards undocumented immigrants. A similar pattern appears for the #MeToo movement, with support declining as income rises, although the relationship is statistically significant only for Latinas. In contrast, the trend is reversed for Black women for both issues, though these associations are not statistically significant. These patterns may reflect how rising income reduces perceived vulnerability to systemic inequality. They also echo prior research suggesting that class can complicate solidarity among WoC, with economic privilege shaping political attitudes even among those who share other marginalized identities (hooks Reference Hooks1984; Huddy, Cassese, and Lizotte Reference Huddy, Cassese, Lizotte and Whitaker2008).

The patterns related to partisanship and ideology are expected given prior research. Women who identified as Democrats and who held liberal views were more likely to support both undocumented immigrants and the MeToo movement. This finding aligns with existing work that shows Democratic women tend to be more supportive of #MeToo (Hansen and Dolan Reference Hansen and Dolan2023) and that Democrats generally favor a path to legal status for undocumented immigrants (Daniller Reference Daniller2019). The timing of the #MeToo movement also provides important context. The movement gained momentum after the release of the Access Hollywood tape, where Donald Trump made demeaning and sexually predatory remarks about women. His election intensified public outrage and helped spark the nationwide 2017 Women’s March, which protested against sexual misconduct and advocated for women’s rights.

These findings also reflect how WoC identity aligns with liberal views (Sanbonmatsu, Greene, and Matos Reference Sanbonmatsu, Greene and Matos2025) and stand in sharp contrast to the responses found in conservative media, particularly in the context of sexual misconduct allegations against Trump. For example, Fox News political commentator Monica Crowley dismissed the 2016 allegations against him as a politically coordinated hoax (Media Matters for America 2016). While other outlets, such as Vanity Fair, have critiqued Fox News for its selective coverage, reporting that the network largely ignored multiple allegations against Trump while covering a single allegation against Joe Biden over 300 times (Ecarma Reference Ecarma2020).

Lastly, nativity shapes attitudes toward undocumented immigrants, though its influence varies and is less evident when it comes to the #MeToo movement. Among all groups except Asian women, U.S.-born respondents were generally less supportive of those without legal status. This pattern is most pronounced among Latinas, where the gap between foreign- and U.S.-born is the widest. This is somewhat surprising, given that Latinas, regardless of nativity, are often thought to maintain strong ties to immigrant communities. However, because only 42% of Latinas in the sample identified as WoC, an identity associated with greater recognition of shared marginalization, the model captures the attitudes of both identifiers and non-identifiers. This distinction helps explain the substantial gap observed between U.S.-born and foreign-born Latinas, as many U.S.-born Latinas do not adopt a women of color identity.

U.S.-born Black women also express lower support for undocumented immigrants, a pattern that may be less surprising given that immigration has not played as central a role in the lives of Black Americans as it has for many Asian and Latina/o communities (Junn Reference Junn2007; Bedolla Reference Bedolla2014).

For #MeToo, nativity does not appear to shape attitudes for Asian women or Latinas. Among Black women, U.S.-born respondents expressed less support for the movement. However, this finding should be interpreted with caution, as 93% of Black women in the sample were U.S.-born, leaving relatively few foreign-born respondents, which limits the strength of this comparison.

Conclusion

This study makes several key contributions to the growing literature on “of color” identities. Using an intersectional framework and self-identification approach, it offers a nuanced understanding of how Asian, Latina, and Black women engage with coalitional identities. First, it expands WoC identity politics by incorporating Asian women, showing that a majority identify as WoC. It also contributes to identity formation research by showing that personal experiences of discrimination, perceptions of structural gender inequality, and empathy toward other historically disenfranchised groups all play meaningful roles in the development of WoC identity.

This study also explores how WoC identity and WoC-linked fate influence political attitudes toward undocumented immigrants and the #MeToo movement. Using a comparative approach, it shows how these forms of intersectional group consciousness operate across Asian, Latina, and Black women. In doing so, it contributes to the growing scholarship on WoC-linked fate by highlighting how shared experiences of race-gendered marginalization can foster political unity across ethnoracial lines.

While “women of color” serves as an inclusive, neutral descriptor for nonwhite women, this study challenges the assumption that all Asian, Latina, or Black women personally embrace it as an identity. The findings reveal substantial variation in adoption rates, ranging from 42% among Latinas to 92% among Black women, underscoring that this label does not resonate equally across groups. Future research should explore why some women do not adopt this identity and how they feel about being categorized under this umbrella label, especially if they are intentionally opting out. For some, the identity’s association with progressive politics may be a deterrent; for others, “of color” may implicitly signal Blackness, creating uncertainty about whether the term applies to them. Given the limitations of survey-based research, future studies could employ a mixed-methods approach, such as open-ended responses or in-depth interviews, to explore individual motivations behind identification.

Future research should also investigate whether other historically marginalized women identify as WoC and how their experiences of discrimination influence that identification. Middle Eastern and North African (MENA) women, for example, represent a racially and religiously diverse group, with many identifying as Muslim. Their intersecting racial, gender, and religious identities often expose them to distinct forms of discrimination. As with Black and Asian women, who are frequently ‘racialized at first sight’ (Junn and Masuoka Reference Junn and Masuoka2008), the hijab can serve as a visible marker of difference for Muslim women, often subjecting them to more overt discrimination than their male counterparts (Dana et al. Reference Dana, Lajevardi, Oskooii and Walker2019; Sediqe Reference Sediqe2023). Additionally, sociopolitical conditions can increase the salience of WoC identity. For instance, increased immigration enforcement or racial targeting may make this identity more resonant for groups such as Latinas, MENA women, or Muslim women. Future research could track these shifts over time to examine how political context shapes engagement with the Women of Color identity.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/rep.2025.10051.

Acknowledgements

I thank Jane Junn and Christian Dyogi Phillips for their guidance on earlier drafts of this paper, as well as the editors of the Journal of Race, Ethnicity, and Politics, and the anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful feedback. I am also grateful for the comments I received when presenting an earlier version of this paper at the 2024 Western Political Science Association (WPSA) Annual Meeting. Any remaining errors are my own.