1. Introduction

Does the political influence over the court system facilitate or delay the onset of armed conflict? What is the relationship between criminal and civil prosecutions on the risk of armed conflict? Studies show that states use courts to control individual action before, during, and after armed conflict (International Crisis Group 2009; Latif et al., Reference Latif, Rehman and Khan2012; Bakiner, Reference Bakiner2014; Loyle and Binningsbø, Reference Loyle and Binningsbø2018). Throughout the armed conflict, regular and special courts have been frequently used to shore up state legitimacy, eliminate armed political opposition, and maintain political order. Outside of the armed conflict context, political elites in authoritarian regimes use the judiciary for social control and political gains (Ginsburg and Moustafa, Reference Ginsburg and Moustafa2008).

The judiciary has essential roles in ensuring state capacity and good governance. When fighting civil wars or insurgencies, the state uses the judiciary to prosecute political oppositions who could potentially be rebel leaders. However, how the state utilizes the judiciary and its relationship with armed conflict remains puzzling. Kalyvas (Reference Kalyvas2006: 394) recognizes judicial repertoire as an important information source in understanding the local context of violence. In a broader debate involving the issues of governance, state capacity, and civil war, the rule of law comes up, which suggests the significance of the court or an impartial judiciary (Hendrix, Reference Hendrix2010). Yet, the studies of Stanley (Reference Stanley2010) and Wood (Reference Wood2003) on the El Salvadoran Civil War suggest that the state and its local collaborators influence the court. Stanley (Reference Stanley2010) suggests that the Salvadoran state used criminal and civil courts to convict political oppositions. In her study of the same Civil War, Wood (Reference Wood2003: 221) finds a significantly higher number of campesinos who perceive that ‘the courts almost never grant fair trials’. These studies suggest that states influence and utilize courts to serve their needs, but a systematic study of their relationship with the onset of armed conflict does not exist.

Similar to Weber (Reference Weber, Gerth and Wright Mills1946), I conceptualize state legitimacy as a process by which civilians believe the state has the right to use coercive authority. I define state capacity as the bureaucratic and institutional infrastructures the state mobilizes to exercise its coercive authority. I conceptualize the state’s use of the judiciary within a broader context of state capacity and how the courts can serve the influence of local elites whom the state co-opts and collaborates with to maintain political order. This article develops a theoretical framework for explaining the state’s mobilization of the courts as a targeted and not overtly violent response strategy for deterring political opposition and securing civilian compliance with its authority. I then link the direct and indirect involvement of the state in this process to criminal and civil cases and hypothesize that the deviation from the national average explains subnational variation in the onset of conflict. In analyses of original data for all 75 district-level courts in Nepal between 1991 and 2006, this article finds that an increase in criminal cases compared to the national average increases the time to the onset of the armed conflict. In contrast, an increase in civil cases compared to the national average decreases the time to the onset of the armed conflict. The article articulates two possible mechanisms that explain these findings. First, the state can use the court to directly prosecute and repress potential political opposition through criminal cases, which can significantly disrupt their ability to mobilize for collective action, either peaceful or violent, at the local level. This will create doubts among civilian supporters about the ability of their leaders to deliver public goods through active participation in the movement. Second, local elites who support and collaborate with the state can use the court to prosecute potential civilian opposition by filing civil cases, further intensifying local discontent and exacerbating underlying grievances against the state and local elites collaborating with the state. Local elites could also target their rivals in this process.

This article contributes to academic discussions on state capacity, repression, and the onset of armed conflict. By providing explanations of how the direct and indirect involvement of the state in the court links to criminal and civil prosecutions, this article examines how the variation in subnational-level civil and criminal court cases increases or decreases the subnational-level risk of the onset of armed conflict. As such, the theory brings the significance of the courts into the discussion of conflict processes, thereby directly contributing to the broader literature on the causes of civil war or the onset of civil war. Second, this article contributes to the growing interest in the subnational-level study of armed conflict (Do and Iyer, Reference Do and Iyer2010; Joshi and Mason, Reference Joshi and Mason2010; Rustad et al., Reference Rustad, Buhaug, Falch and Gates2011; Mukherjee, Reference Mukherjee2018). The article’s use of subnational-level court cases also contributes to expanding the notion of state capacity in comparative politics and armed conflict research (Luna and Soifer, Reference Luna and Soifer2017; Mukherjee, Reference Mukherjee2018). Finally, this study contributes to the discussion on repression and mobilization (Mason and Krane, Reference Mason and Krane1989; Gurr, Reference Gurr2000; Mason, Reference Mason2004) and how repression causes civil war (Young, Reference Young2013).

In terms of the structure of this article, the next section provides an overview of civil war onset literature as a way of developing a theoretical framework of civilian compliance. It discusses the direct involvement of the state in repressing political opposition and the indirect involvement of the state’s collaboration with local elites to generate civilian compliance. The discussion suggests that direct involvement increases the cost of rebellion while minimizing the risk of the onset of conflict and indirect involvement lowers the cost of rebellion while increasing the risk of the onset of conflict. The second section provides a brief historical context of the judiciary in Nepal within the framework of a weak state, political influence, and the use of the court to deter political opposition. Further, the theoretical framework is used to derive testable hypotheses in the context of the Maoist conflict in Nepal. The argument specific to the state’s direct involvement is tied to the use of criminal cases, and the state’s indirect involvement is tied to the use of civil cases. The research design section discusses the original subnational-level court data collected through archival research in Nepal, with additional data for other relevant variables. In the penultimate section, the results of different survival model specifications are discussed. Lastly, the conclusion section discusses the implications of the findings as well as future research avenues.

In terms of case selection, Nepal is an ideal case for this research for two reasons. First, as the democratic peace thesis would suggest (Hegre et al., Reference Hegre, Ellingsen, Gates and Gleditsch2001), Nepal’s transition to multiparty democracy in 1990 should have avoided armed conflict. Second, the democratic transition was supposed to promote good governance as civilians could vote with a secret ballot and choose a government responsive to their needs. Instead, Nepal’s main political party, particularly the ruling Nepali Congress Party, forged an alliance with local elites who played an instrumental role in the survival of the authoritarian Panchyat Regime to secure votes and civilian support in democracy (Khadka, Reference Khadka1993). This nexus allowed the continuous influence of local elites at the local level. Nepal’s case is also preferred because court and conflict data are available at the subnational level.

2. Motivation and theoretical framework

I begin the theoretical framework with four key terms used in this article: the state, political opposition, local elites/leaders, and civilians. I define the term ‘state’ similar to the Weberian concept of the state that holds coercive authority (Weber, Reference Weber, Gerth and Wright Mills1946). As such, the term is used loosely to refer to the ruling parties that hold control over the coercive authority. Similar to Tilly’s polity model (Tilly, Reference Tilly1977), I use ‘political opposition’ to refer to the aspiring political movements and parties outside the ruling coalition dominating the state. Political oppositions oppose the state and demand reform so the marginalized population can legitimately claim access to state power and resources. Similar to Tilly’s polity model (Tilly, Reference Tilly1977), while there might be a lot of political opposition to the state, only a few might become a rebel movement. The term ‘local elites’ refers to social, political, and economic elites (Scott, Reference Scott1972a) who are either part of the ruling parties, the opposition parties, or movements. I use the term ‘civilians’ to refer to those not in a position of social, political, and economic influence and therefore are the target of the state and armed movements (Kalyvas, Reference Kalyvas2006; Staniland, Reference Staniland2012). While local elites are arguably civilians, unlike civilians, local elites hold either social, political, or economic influence to support or oppose the state authority and generate civilian compliance at the local level.

Dominant theories of civil war and insurgency suggest structural conditions and country-level characteristics to increase a country’s susceptibility to armed conflict. Studies suggest that states at risk of armed conflict or the onset of civil war have a dependence on natural resources, weak institutional capacity, high rates of poverty, weak economic growth, high levels of population pressure, exclusion of ethnic minorities from power sharing, and irregular and frequent leadership change (Fearon and Laitin, Reference Fearon and Laitin2003; Gleditsch and Ruggeri Reference Gleditsch and Ruggeri2010). In all overarching conceptual framings, such as greed vs. grievances, weak vs. strong state, or democracy vs. anocracy, the cause of civil war seems to lie within the characteristics of weak states that tend to be more prone to violence as they respond to political dissent with repression (Young, Reference Young2013).

In country-level analyses, the distribution of civil war throughout the country is assumed to be uniform, yet there are variations in the subnational-level risk of armed conflict (Rustad et al., Reference Rustad, Buhaug, Falch and Gates2011). Most civil wars start in the peripheries, such as in the remote western part of Nepal, the remote Andes in the cases of Peru and Colombia, and remote regions of Jharkhand in the case of India. With respect to India, for example, studies suggest mining in tribal communities (Hoelscher et al., Reference Hoelscher, Miklian and Vadlamannati2012), land inequality, forest and scheduled and tribal communities (Gomes, Reference Gomes2015), and indirect colonial rule that preserved the structural condition for ethnic grievances, and state weakness facilitated the emergence of the Maoist conflict (Mukherjee, Reference Mukherjee2018). While these studies bring some nuance to the causal processes, subnational-level state capacity remains a more salient cause.

The aspect of state capacity is evident in explaining the onset of insurgent violence in Colombia, as studies find insurgent violence in municipalities with a weak state presence (Holmes et al., Reference Holmes, Piñeres and Curtin2007). Similarly, the explanation of the Maoist conflict in Nepal alludes to uneven development, poverty, land inequality, lack of political participation, and geography as causes for its onset (Murshed and Gates, Reference Murshed and Gates2005; Do and Iyer, Reference Do and Iyer2010; Joshi and Mason, Reference Joshi and Mason2011).

In country-level and subnational-level explanations of the onset of civil war, the weak state argument converges to a degree. The subnational study of Mukherjee (Reference Mukherjee2018) suggests the significance of direct and indirect state rule in generating strong and weak state institutions within a country by explaining how weak institutions lead to armed conflict. Within the weak state argument, Young (Reference Young2013: 519) suggests that while the state’s use of repression minimizes the costs of generating compliance, it can still lead to armed conflict.

In this article, I seek to expand the explanation of the direct and indirect involvement of the state at the subnational level in generating legitimacy or compliance among civilians and how this affects variation at the subnational-level onset of armed conflict. In particular, I show how direct and indirect state involvement affects the risk of the onset of armed conflict at the subnational level. Figure 1 provides an overview of theoretical arguments.

Figure 1. Approaches to generate legitimacy and civilian compliance.

In my theoretical framework (Figure 1), I concur with the impact of regime transition on institutional fluidity and the propensity of the state to use repression to generate civilian compliance (Gleditsch and Ruggeri, Reference Gleditsch and Ruggeri2010; Young, Reference Young2013). I also concur with the argument that the state is inherently repressive for its control over coercive power (Weber, Reference Weber, Gerth and Wright Mills1946) but further argue that the state is adaptive in figuring out different mechanisms to generate civilian compliance (Weiss, Reference Weiss1998). In this regard, the state can flexibly mobilize resources and institutions and target specific locales to generate civilian compliance. For this purpose, the state can be involved directly in generating civilian compliance or by mobilizing local elites collaborating with the state and having social, political, and economic leverage in a given locale. From the principal-agent theoretical perspective, the principal, in this case, the state, can use and has been using local elites to carry out the tasks delegated to them by the central state (Waterman and Meier, Reference Waterman and Meier1998). However, information asymmetry exists between central state authorities and local elites (Miller, Reference Miller2005). The state may hold more information about local elites, but local elites hold more information about civilians and their political support. Further, not all local elites collaborate with the state, as some will challenge the state’s legitimacy. Moreover, the state may not know all the latent political threats before the onset of the conflict. Similarly, local elites might not share all the information about the threat with the state for safety reasons. As a result, part of the civilian compliance generation process may involve repressing local elites and civilians.

The state’s choice to get involved directly in generating civilian compliance with the state and its legitimacy or to delegate the task to local elites depends on information and the availability of the sanctions necessary to generate compliance. I argue that the state would prefer to be involved directly in repressing local elites of political oppositions or movements for four reasons. First, the state has sufficient information about these elites and leaders. Second, implementing sanctions against a selected few is more manageable for the state than repressing their entire known and suspected support base. Third, because of their influence in mobilizing civilians, targeting local elites is the most effective strategy to reduce popular collective action against the state. Finally, involving local elites who support the state in this process would be counterproductive, as these elites may not have the capacity to impose sanctions against their own peers. Carefully targeted repression might work in generating civilian compliance with the state or reducing support for the opposition (see Lichbach and Gurr, Reference Lichbach and Gurr1981; Mason and Krane, Reference Mason and Krane1989).

On the other hand, the state can delegate the task of civilian compliance to local elites collaborating with the state. Local elites hold more information about civilians and, therefore, can target larger groups. For resources and access to the state, local elites can tailor specific sanctions against civilians to garner compliance, similar to landlords in patron–client relationships (Scott, Reference Scott1972a; Popkin, Reference Popkin1979; Mason, Reference Mason1986). However, when the state utilizes local elites to generate civilian compliance, repression can become widespread as civilians can try to free themselves from their dependency. Therefore, it is reasonable to expect shared grievances and radicalization among peasants and civilians against the local elites due to the socially constructed nature of the threat. This creates conditions for oppositional mobilization, and opposition leaders may find that the cost of organizing supporters against the local elites is reduced (see Lichbach and Gurr, Reference Lichbach and Gurr1981; Mason and Krane, Reference Mason and Krane1989; Young, Reference Young2013; Shesterinina, Reference Shesterinina2016).

In my theoretical framework, the state gets directly involved by targeting local elites and leaders who oppose the state. By sanctioning these individuals, the state effectively raises the cost of leading and organizing an opposition movement and removes the threat from current and future opposition leaders (also see Lichbach, Reference Lichbach1998). The context of indirect state involvement through local elites collaborating with the state differs from this direct sanction approach in several ways. First, the cost of organizing against the local elite is significantly lower for the targeted civilians compared to the state. Second, the sanctions used might be ineffective. While these local elites have the backing of the state, they might not be able to access these resources at a critical moment should the sanctions fail. Finally, and most importantly, the repression by local elites to generate civilian compliance can potentially exacerbate the already tenuous hierarchical relationship in the context of the local political economy, encouraging many civilians to organize against local elites. When many civilians are affected by repression, it can easily escalate into organized dissent (also see Mason and Krane, Reference Mason and Krane1989; Young, Reference Young2013).

As such, the theoretical framework suggests a reduced risk of the onset of armed conflict when the state is directly involved and targets a few local elites and leaders opposing the state. On the other hand, when local elites are mobilized to target civilians more broadly to generate compliance, it aggravates the already tenuous relationship between the state and its people and gives civilians a purpose for organizing against local elites and their patrons – the state. In the following section, I use this framework to explain how the courts were used to generate compliance directly by the state through criminal cases and by local elites through civil cases in Nepal. I then derive empirically testable hypotheses. As a prelude to applying the theoretical framework, the next section provides an overview of the nexus between the judiciary, the political transition of 1990 in Nepal, and the court system.

3. Nepal: a brief history of judiciary and political control

Before contextualizing the theoretical framework developed above and deriving testable hypotheses, a brief historical overview of the judiciary in Nepal can help clarify the role the courts play as a political instrument of civilian control and compliance. This overview describes the process of the judicial system’s institutionalization that gave enormous political influence and control to ruling elites and their local collaborators, which is now in the form of ruling political parties. The discussion shows the relationship between local elites and the court, such as how much power local elites have over the court, and whether the court is a major tool for the state and local elites to achieve their goals.

Nepal’s current form of the judicial system can be traced back to the Muluki Ain (Penal Code) of 1854, promulgated by the first Rana prime minister, Janga Bahadur Rana, after his visits to Britain and France in 1850–51. The Muluki Ain of 1854 was the first written Code of Nepal that successfully established the ruling elite’s control over the state and the people by institutionalizing the Hindu religion-based property rights, caste system, and other practices. For the next 100 years, the ruling elites and their local allies used this Penal Code to maintain control over civilians.

For the first time in Nepal, the judiciary was established as a body of the executive in 1951 with the creation of Pradhan Nyayalaya (Apex Court). In 1956, the Supreme Court Act was promulgated and transformed the Apex Court into the Supreme Court. The Judicial Administration Act of 1962 established the first judiciary system with the High Court, District Court, and State Court under the Supreme Court. The court system has since undergone some organizational restructuring as provided in the 1959, 1962, and 1990 constitutions (Joshi and Katuwal, Reference Joshi and Katuwal2014). During the Panchyat regime, as established by the 1962 constitution, the King was an absolute monarch, and it was the King’s prerogative to appoint a chief justice. The Judicial Service Commission had members appointed by the King, including the Chief Justice, who made appointments of judges at lower-level courts. While the King was said not to interfere in the day-to-day operation of the courts, the ruling elites and their local collaborators had significant sway in filing cases in the courts and setting punishments.

After establishing the Panchyat regime, the king announced a new Muluki Ain in 1963, replacing its 1854 predecessor. As such, this new Muluki Ain reflected the changing social, political, and economic contexts in Nepal. It also created the legal tools necessary for the king to regain control over civilians. The new code was the main reference document for the courts in deciding cases that maintained the ruling class’s control at the local level, which was the way the ruling elites and kings governed the country in the past. Nevertheless, bringing cases to court was not straightforward and was not accessible to most villagers and peasants who depended on local elites, typically landlords, for their livelihoods. Further, for many of these individuals, it was not prudent to go to court to file a case, as they primarily relied on local elites to resolve any disputes. Furthermore, any displeasure of local elites would bring extreme economic hardship to civilians because the local political economy was controlled by local elites (see Whelpton, Reference Whelpton1991; Reference Whelpton2005; Joshi and Mason, Reference Joshi and Mason2007). As such, local elites with ties to the ruling elites had significant roles in resolving cases locally, bringing cases to the courts, and producing evidence once cases were put to trial. Therefore, local elites with ties to the state prosecuted those who disagreed with them, and consequently, those who opposed the King’s direct rule were prosecuted and imprisoned (Whelpton, Reference Whelpton2005: 102–112). Until 1990, political parties were banned, and many political leaders who opposed the King’s direct rule sought shelter in India to avoid prosecution and imprisonment.

4. The democratic transition of 1990 and the onset of the Maoist conflict in 1996

In 1990, those banned political parties coordinated and organized a popular movement against the King’s direct rule, succeeding in establishing a multiparty democracy (Khadka, Reference Khadka1993; Whelpton, Reference Whelpton2005). The successful people’s movement of 1990 transformed the absolute monarchy into a constitutional monarchy, and a multiparty democratic constitution was promulgated in 1991. Unfortunately, Nepal’s democratic transition did not transform the political economy (Khadka Reference Khadka1993; Joshi and Mason, Reference Joshi and Mason2010). While the new constitution curtailed the King’s political influence, political parties, mostly the ruling Nepali Congress party, welcomed many landlords and local elites from the previous regime as their local collaborators and supporters (Khadka, Reference Khadka1993; Lawoti Reference Lawoti2005; Whelpton, Reference Whelpton2005; Joshi and Mason, Reference Joshi and Mason2007). The outcome was that 90% of the 205 seats in the first parliament elected in 1991 were controlled by landed elites (Khadka, Reference Khadka1993: 52). With the democratic transition in 1990, the nature of the social, political, and economic influence of landed elites therefore did not change for most people in Nepal. Local political dominance and civilian compliance became confrontational among political parties based on those in political power and their ideological orientations. The Informal Sector Service Center (INSEC), a non-governmental human rights organization, in its first annual human rights report published two years after the democratic transition, notes the confluence of the nexus between the state and local elites:

Human rights have been mainly violated by the so-called influential and elite people in villages, by the wealthy in towns, and the law enforcing agencies. In many cases, only the state may not be a violator. However, the violators in rural areas gain support from the local state units. (INSEC 1992: 287)

What is important to note here is that the newfound political rights and freedom for civilians under the new constitution were inconsistent with the prevailing political economy. Theoretically, people were free to vote the way they wanted, but in practice, they would fear to do so as they were dependent on local elites for their subsistence (Joshi and Mason, Reference Joshi and Mason2007). Such was the case in clientelist political dependency (Scott, Reference Scott1972a, Reference Scott1977; Paige, Reference Paige1978; Popkin, Reference Popkin1979). After Nepal’s democratic transition in 1990, local elites and patrons joined the dominant political party, ran for local and national offices, and found a way to maintain their influence (Khadka, Reference Khadka1993; Joshi and Mason, Reference Joshi and Mason2007).

Among peasants and civilians, the sense of fear of exclusion and marginalization from local elites might have been moderated to a degree as rival political parties and their elite supporters provided some protection. However, such protection was not enough as the dominant party and its allies had support from the state, which they used against their competitors. Therefore, while the informal compliance mechanism secured through patron–client relations might have weakened to a degree due to the political transition in 1990, it also encouraged local elites to instead use the formal process of the courts to deter political opposition. For the dominant party’s leaders and local elite allies, filing cases in court against their opponents and their support bases was not difficult, given their influence in local state units. Further, the ruling party had dominance in appointing judges based on the new constitution. Therefore, rival parties challenging the parties of the landed elites were left with few choices other than to withdraw from politics or shift to dissident forms of collective action (as opposed to election politics), eventually including insurgent violence. The Maoist party, which had participated in the democratic process since 1990, withdrew from electoral politics in 1996 and called for armed conflict against the state. Before the onset of the conflict in 1996, one of the 40-point demands of the Maoist party was to have the judiciary under the people’s control (United People’s Front Nepal 1996). Another demand was specific to the court cases:

14. Everyone arrested extra-judicially for political reasons or revenge in Rukum, Rolpa, Jajarkot, Gorkha, Kabhrc, Sindhupalchowk. Sindhuli, Dhanusa, Ramechhap, and so on, should be immediately released. All false cases should be immediately withdrawn. (United People’s Front Nepal 1996)

The local support for rebellion was slowly growing to various degrees across the country well before the actual onset of the conflict in 1996. Notwithstanding the possibility that local elites collaborating with the state have incentives not to provide information to the state or eliminate their rivals, their political influence over the court provided elites and leaders from the dominant parties with a formal mechanism to prosecute political oppositions and secure civilian compliance. Below, I explain how the types of court cases relate to the onset of the conflict based on the theoretical framework discussed earlier.

5. The court cases and the onset of armed conflict in Nepal

With respect to deterring political opposition and securing civilian compliance, the theoretical framework presented earlier suggests the significance of direct and indirect involvement of the state through local landed elites co-opting with the state. It also suggests the significance of using political influence, access to administration and resources against the political opposition and civilians, and the court process as effective strategies for weakening and deterring political opposition and securing civilian compliance with the authority. Because the court process involves the due process of law, the argument is not that the court was the cause of the onset of armed conflict but rather that the use of the courts by state and local elites representing the state facilitated the onset of armed conflict by repressing political opposition and movements. In Nepal, court cases are filed under two categories: criminal and civil cases. Who is to be implicated in which type of case is a strategic decision as it involves significant economic, political, and social implications for all involved. Below, I explain how these implications differ and how they could increase or decrease the risk of the subnational onset of the Maoist conflict.

Criminal cases: Criminal cases include offences against the state, crimes against a person, and other statutory crimes as defined in the law. In criminal cases, one of the parties is the state, which serves as the prosecutor. For the broader societal impact of criminal cases, the form of criminal prosecution is targeted, and the objective is deterrence. Human rights research has found that prosecution for human rights abuses proved to be an effective deterrence to improve compliance with human rights norms and practices (Mennecke, Reference Mennecke2007; Appel, Reference Appel2018). In criminology research, criminal prosecution is found to have a significant deterrence effect on crime rates (Klepper and Nagin, Reference Klepper and Nagin1989). According to Klepper and Nagin, criminal prosecution works because of its ‘extreme adverse impact’ on the lives of the defendant (Reference Klepper and Nagin1989: 742). In Nepal, political leaders and influential elites from the opposition were frequently targeted after the democratic transition in 1990. The objective was to deter selected political opposition actors who were locally visible. Consider these two examples from the district of Rukum, which was the district most highly affected during the Maoist insurgency in Nepal, as evidence of the influence of the state and the dominant political elites in criminally prosecuting political opposition:

Bir Bahadur of Hukam VDC was collecting royalty from villages for hunting, land revenue, and festival taxes even after the political change in 1990. On November 22, 1992, local people revolted against this feudal system and staged a protest rally. Suddenly the procession was fired at from the house of Bir Bahadur Buda. But the local administration, instead of accusing Bir Bahadur, filed a case against Om Prasad Gharti, a member of the district development committee, and 27 others under the Public Offense Act. Pradhan Pancha during the past regime [Panchyat regime], Bir Bahadur Buda has now been in the ruling party [Nepali Congress Party]. The local people and employees charge that his affiliation to the ruling party is the reason for such behaviour. (INSEC 1992: 230) [lightly edited for clarity]

On April 25, 1992, upon the arrival of Prime Minister Girija Prasad Koirala in the district headquarters of Musikot, a protest rally commenced, which was led by a local member of parliament. In response, the local administration and the ruling party arrested 27 civilians and political workers. Shyam Bahadur Bohara and Puma Gharti, two such political workers, were charged of violating the Public Offence Act. (INSEC, 1992: 229) [lightly edited for clarity]

The state inflicts higher social and political costs on these opposition leaders by implicating them in criminal cases, which should, theoretically, motivate these leaders to organize an armed movement against the state (Young, Reference Young2013; Brathwaite, Reference Brathwaite2014). Yet, criminal prosecution is targeted to deter a selected few in a given locality and, therefore, is not widespread. Further, such prosecution inflicts serious material costs, such as time and resources to fight the case, on the targeted individuals and limits their social and political influence within the community, specifically considering their social status. Recuperating these costs and regaining local civilian support takes time, given the public nature of the targeting, which restricts the ability of local leaders to organize armed conflict. Therefore, the effect of criminal prosecution of the opposition is similar to the targeting of criminal gangs and leaders of insurgent groups, as in the short term, it serves to weaken the intended opposition (Jordan, Reference Jordan2009; Phillips, Reference Phillips2015). In other words, it reduces the short-term risk of armed conflict onset by disabling the capacity of opposition leaders or organizations to mobilize civilian support for their cause. Therefore, I hypothesize that:

H1: A district with a high increase in criminal cases compared to the change in the national average has a reduced risk of armed conflict onset.

Civil cases: In civil cases, the state is not directly involved. It involves civilians both as plaintiffs who bring the case to the court and as defendants who defend the allegations. In a clientelist political economy, the local elites and leaders are the protectors of their clients, resolve any conflicts involving them informally, and defend them in courts (Scott, Reference Scott1972a, Reference Scott1972b). With the advent of competitive electoral politics, theoretically, such dependency would erode to the level that peasants or clients gain some bargaining leverage with their patrons or local elites, as they have the freedom to go to other patrons for their needs if their current arrangement is no longer sufficient. Therefore, the transition to electoral politics in Nepal is rather tumultuous for both the civilians and local elites. Civilians and peasants would like to exercise their newfound leverage, but they are still dependent on their patrons since they still owe them. Under such circumstances, it is reasonable to expect that patrons would attempt to recover their loans or material support by filing civil cases against their clients in court.

The political transition can be equally difficult for local elites and patrons as well. To remain influential in their communities, they need access to political leaders in various hierarchical ranks, to the state’s local administration, and to financial resources. In exchange for these, the local elites can deliver civilian compliance in the form of votes to the dominant party in elections (Scott, Reference Scott1972a: 110; Joshi and Mason, Reference Joshi and Mason2007). In a competitive electoral environment, resource commitments to individual peasants and civilians are costly for local elites or leaders. The cost-effective way of maintaining dominance and compliance over peasants and civilians is by occasionally filing civil cases against them in courts, which makes the threat credible. Filing cases can be a fairly easy process for local elites for two reasons. First, peasants and civilians have indebtedness or obligations towards the patrons, as discussed above, which can be used as a cause for filing cases. Second, the support from the politically dominant parties and their connections to the state’s local administration, including both the police force and the court system, serve to make the filing process simpler and allow for cases based on false evidence to be put to trial. In Nepal, local elites and leaders representing the dominant party used their political power to implicate civilians in false cases for political revenge (INSEC, 1992: 143). Fighting a case in court is a helpless situation for peasants and civilians, as the following narratives from the district of Kanchanpur suggest:

While practicing law there are a tradition and legal obligation to practice it on the basis of evidence available. But clever people are able to provide evidence. They are well-versed even at hiding the evidences that let them in difficulties but straight, helpless and weak people do not know how to produce evidence. (INSEC, 1992: 273)

When Nepal transitioned to democracy in 1990, the literacy rate was as low as 33%, and most peasants and civilians in many districts did not know how to read or write. Therefore, most civilians would not even know the case they were contesting. Coupled with a well-established opponent and a lack of resources, defending a court case was thus a distant possibility for most civilians. Given the nature of the subsistence political economy and the disruption in patron–client relationships due to the transition to the electoral political process, it is reasonable to expect an increase in civil cases involving peasants in post-1990 Nepal. I argue that peasants and civilians trying to come out of patronage or economic dependency thus found themselves further marginalized and deprived, as they had to defend themselves against powerful elites in court. The causes of rebellion are related to consistent repression, grievance, and marginalization (e.g. Gurr, Reference Gurr1971; Young, Reference Young2013), all of which persisted in post-1990 Nepal. As the prosecution of civilians and peasants in civil cases became widespread, the cost of mobilizing and organizing against local elites and state collaborators declined. In other words, the peasants and civilians had no other solution to redress their underlying grievances against the local elites and state collaborators except to organize and join a rebellion against them. Therefore:

H2: A district with a high increase in civil cases compared to the change in the national average has an increased risk of the onset of armed conflict.

6. Research design: data and dependent and independent variables

To test the hypotheses outlined above from the theoretical framework, this research utilizes district-level data between 1991 and 2006 for all 75 districts in Nepal. The unit of analysis is a district year. The observation period starts several years ahead of the Maoist party’s stated incompatibility and the onset of the conflict in February 1996 for two reasons. First, the Maoist party was politically active and contested the first democratic elections in 1991. Second, the dominant political parties that came into power after 1990 used their new control over the state and local collaborators to repress political oppositions and their civilian support bases (Khadka, Reference Khadka1993; Lawoti, Reference Lawoti2005; Whelpton, Reference Whelpton2005; Joshi and Mason, Reference Joshi and Mason2007, Reference Joshi and Mason2010). As such, it is desirable to account for the criminal and civilian prosecution dynamics immediately after the political transition in 1990.

The dependent variable in this analysis is the district-level onset of the Maoist conflict. The ‘onset’ is operationalized in terms of conflict-related deaths and is coded when a district reaches 25 conflict-related deaths as identified in the individual-level victim dataset (Joshi and Pyakurel, Reference Joshi and Pyakurel2015). This rule to code the conflict onset at the district level differs from the Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP) rule to code the onset of armed conflict in three ways (Wallensteen and Axell, Reference Wallensteen and Axell1993). First, the UCDP data uses 25 battle-related death thresholds, which are different from all conflict-related deaths used in this article. Second, the UCDP data codes the onset when the battle deaths reach 25 annually in a given country. For this analysis, reaching 25 conflict-related deaths to code the onset of the conflict at the district level is desirable. This is because the dominant strategy used by the state and the Maoist groups was selective targeting. The state selected local opposition political leaders, and the Maoist rebels targeted local elites. Therefore, the entire conflict produced more deaths through targeted violence than combat fighting (Joshi and Pyakurel, Reference Joshi and Pyakurel2015). Third, the analysis conducted in this article is the subnational-level variation, which is different from the country-level focus in the UCDP data. The descriptive statistics and correlation matrix are presented in Appendix Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

To test Hypotheses 1 and 2, information is used on criminal and civil cases filed at the lowest level of courts, Nepal’s district-level court. As previously explained, in criminal cases but not civil cases, one of the conflict parties is the state. This information is retrieved from annual reports of the Supreme Court of Nepal through archival research, which was conducted in Nepal. Reports between 1991 and 2006 are used to compile this information (Supreme Court of Nepal, 1991–2006). Figure 2 displays the annual country-level cases between 1991 and 2006. As shown in the figure, both the criminal and civil cases registered at the district-level courts increased after 1990. The criminal cases declined to the 1991 level in 2001. The civil cases also declined that year but increased sharply again in 2002. This is because the parliament was dissolved under the pretext of a state of emergency to fight the Maoist conflict, suggesting local elites were making efforts to regain local legitimacy and control by prosecuting civilians. Panel b in the figure provides an overview of the national-level percentage change in criminal and civil cases.

Figure 2. Number and annual changes in civil and criminal cases.

A variable, change in criminal cases, is used to test Hypothesis 1. To derive this variable from the annual report, the district-level annual percent change is first calculated. This variable is then subtracted from the national-level percent change, which is the sum of all criminal cases registered in all district courts for a given year [change = (YoY district % change – YoY national % change)]. The same approach is used to derive a variable, change in civil cases, which is used to test Hypothesis 2.

I use this approach for generating the explanatory variables for theoretical and methodological reasons. Theoretically, this approach helps identify the district the state is targeting to establish its authority and civilian compliance. Nepal’s armed conflict is explained in terms of horizontal and vertical inequalities, and similar data-generating approaches were used in earlier studies to explain the level of violence in the Maoist conflict in Nepal and relative socio-political grievances (Murshed and Gates, Reference Murshed and Gates2005; Joshi and Mason, Reference Joshi and Mason2010). All districts are different from each other in terms of socio-economic indicators, including population, which could influence year-over-year changes in court cases. Methodologically, this approach helps to normalize the data, as presented in Figure 2b. Further, district-level changes do not provide much information on their own but hold valuable information when compared with the national-level trend. The way the data was configured allows comparisons across district-level changes with the national-level changes, helping identify districts deviating from the national average. Such deviation could signal the use of the court by the state, the ruling coalition, or its local collaborators to prosecute the local political opposition figures and civilians.

The availability of the court data for civil and criminal cases allows proposed hypotheses testing. However, it is important to acknowledge the limitations of the data used in the analyses because the data is not disaggregated for different types of civil and criminal cases. For example, it is ideal to have district-level data on civil cases, specifically identifying land disputes and credit lending cases involving local elites. Similarly, for criminal cases, it is desirable to have data on criminal prosecutions involving political protests or cases of a political nature. The annual reports from the Supreme Courts do not provide such detailed information. The reports provide some aggregate data at the level of development regions before the onset of the Maoist conflict in 1996. The aggregate data shows high civil cases involving land and lending-related issues (around 41% of total cases) and high criminal prosecutions under the miscellaneous category (around 14% of total cases) in the district courts of the central development region. The Midwestern region, where the conflict started, had around 31% land and lending-related cases and only about 9% criminal cases under the miscellaneous category. As such, in the Midwestern region, civilian grievances were reasonably high against local elites, but the state did not target local opposition at a higher rate. Therefore, it can be inferred that the Maoist rebel movement easily mobilized upon civilian grievances against local elites and the state in the Midwestern region.

One of the consistent findings related to district-level variation in the levels of violence in Nepal’s Maoist conflict relates to social, political, and economic grievances (Murshed and Gates, Reference Murshed and Gates2005; Do and Iyer, Reference Do and Iyer2010; Joshi and Mason, Reference Joshi and Mason2011). In empirical analyses, I control for such grievances by using literacy rate gap and life expectancy gap variables with data from the 1991 and 2001 population censuses (CBS Nepal, 1991, 2003). The 1991 census data is used until 2000, and the 2001 census data is used until 2006, the last observation year in the data. The analyses also use a variable road density gap with the 1998 data from the United Nations Development Program – Nepal, as roads are critical economic infrastructure connecting various communities in the districts and their connections to regional-level economic centres and markets and whose density suggests the level of economic prosperity (UNDP Nepal, 1998).Footnote 1 The analysis also includes a variable political participation gap as a measure of opportunity for civilians to express their political preferences. This variable is a district-level percentage gap in electoral turnout and is created by subtracting the percentage of national voter turnout data from the 1991, 1994, and 1999 parliamentary elections. The 1991 election data is used until 1993, the 1994 election data is used until 1998, and the 1999 election data is used until 2006. These data come from the Election Commission of Nepal (1991; 1994; Election Commission of Nepal, 1999).

The analysis includes a population variable consistent with the argument about population pressure and armed conflict (Urdal, Reference Urdal2008). The population variable captures district-level population estimates, and the data comes from annual reports by the Department of Health Services, 2006). People might have fled the district for fear of targeted violence by both the state and the Maoist group (Adhikari, Reference Adhikari2013). Therefore, the analysis includes a variable absent population with the 2001 national census data (CBS Nepal, 2003). The analysis uses this data for earlier years.Footnote 2 Both variables are normalized by taking a natural log. Because people from upper castes predominantly dominated state institutions, the participation of ethnic and lower-caste people in the Maoist conflict was high (UNDP Nepal, 1998; Lawoti Reference Lawoti2005; Joshi and Mason, Reference Joshi and Mason2010). Therefore, this analysis includes a caste and ethnic fractionalization variable with the 2001 census data. This data comes from Joshi and Mason (Reference Joshi and Mason2010).

One of the key findings related to the onset of civil war relates to rough terrain or geography (Fearon and Laitin, Reference Fearon and Laitin2003). Therefore, the analysis controls the geography of Nepal by using the Hill region and Mountain region variables with the Terai region as a reference category. The Terai region is plain land in the southern part of Nepal. Each of these variables takes a value of ‘1’ if the districts fall in each of these regions, otherwise ‘0’. The analysis also controls for a possible spatial diffusion by controlling for regional variation. As such, five development regions of Nepal – the Eastern region, Central region, Western region, Midwestern region, and Far Western region – are used as controls. Variables for each region take a value of ‘1’ for the district falling in each region, otherwise ‘0’. The reference category is the Midwestern region, where the Maoist conflict started.

7. Empirical analyses and findings

In this study, the dependent variable is the district-level onset of the Maoist conflict, which is observed when the district reaches 25 conflict-related deaths. Survival analysis is used to explain the onset event. This method analyses the time until an event occurs by reaching a 25-death threshold. A district that reaches the 25-death threshold is coded as a failure and removed from the risk sets. Districts that never reach that threshold by 2006 are right-censored. The patterns of the event failure are presented in the Kaplan–Meier figure (Appendix Figure 1). Over 52% of the 75 districts experienced armed conflict onset by 2002, or the 11th year after the districts entered the dataset. By 2005, or the 14th year, when the parties ceased fighting and started negotiations, 71 out of 75 districts experienced the onset of armed conflict.

The theoretical argument developed in this article suggests that the risk of conflict onset increases with an increase in district-level civil cases and decreases with an increase in criminal cases. Because various factors influence the level of violence, not all districts might experience the onset of conflict at the same risk. As such, the hazard rate of conflict onset can be low in the early phases and then increase and subside after some time. The primary focus of this research is not the shape of the baseline hazard function but rather the relationship of independent variables to the dependent variable – the subnational-level onset of the conflict. Therefore, a semi-parametric or parametric model fits the data and is better than logit or probit models (Efron, Reference Efron1988; Box-Steffensmeier and Jones, Reference Box-Steffensmeier and Jones2004).

Five models are estimated using semi-parametric or parametric model specifications. After estimating these models, the Akaike information criterion (AIC) and Bayesian information criterion (BIC) are estimated. Appendix Table 3 compares AIC and BIC values for these model specifications. The estimated AIC and BIC values are the lowest for the Weibull specification in four out of six models compared to a semi-parametric Cox proportional hazard and parametric log normal, log logistic, and exponential models. For the log logistic model, the estimated AIC and BIC values are almost identical in Model 1 and slightly lower in Model 2 than those of the Weibull model. Nevertheless, the estimated parameter (p) in Weibull models is greater than 1 and is statistically significant across all models. This suggests a monotonically rising hazard of event failure over time and is consistent with the reason for selecting the Weibull model specification. As a robustness test, empirical analysis is also performed using the logit and probit model specifications with the dependent variable event failure.

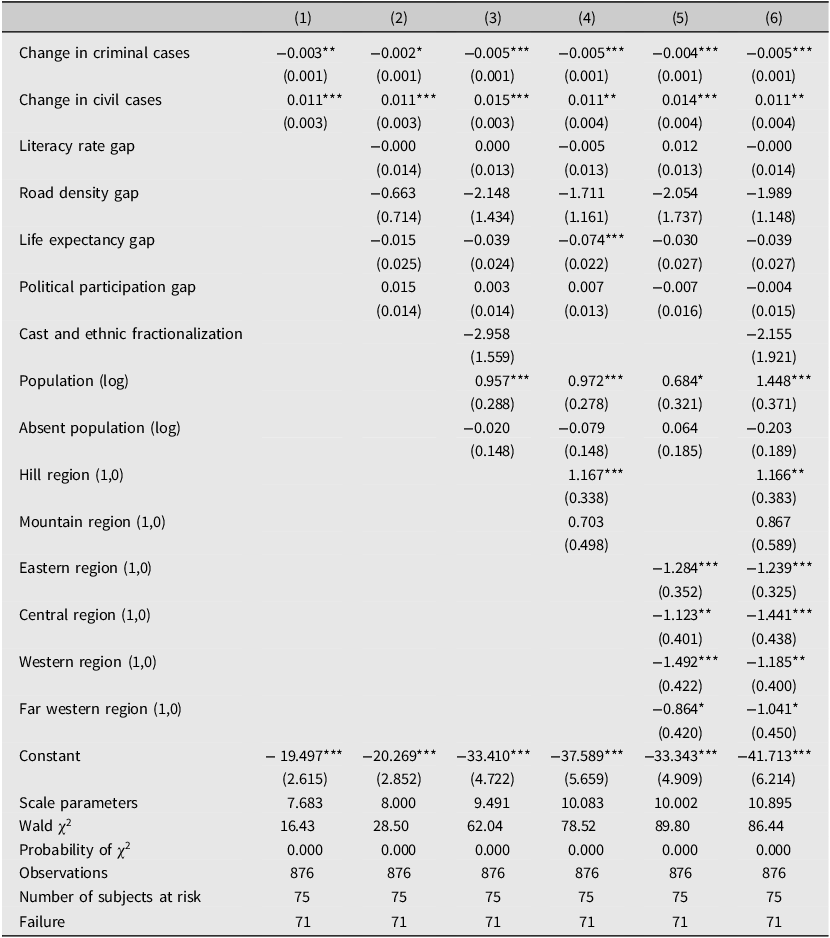

A series of Weibull models was estimated to test the proposed hypotheses and is presented in Table 1. The first set of models includes variables specific to two hypotheses: change in criminal cases and change in civil cases. Model 2 builds on it and adds variables that best capture the economic and political factors. In Model 3, variables for population-specific characteristics are added. Model 4 drops caste and ethnic fractionalization variables and adds control for geography, and Model 5 replaces these with region-specific development variables. Model 6 is the final model with all the control variables.

Table 1. District-level risk of armed conflict onset

Models are based on Weibull distribution specification, and coefficients are reported. Robust standard errors in parentheses. Two-tailed tests. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Hypothesis 1 Suggests that the districts where the state is prosecuting more individuals in criminal cases than the national average have a lower risk of the onset of armed conflict. The estimated coefficient for change in criminal cases is consistently negative across all models and statistically significant with at least a 0.01 level of confidence (Table 1). The estimated coefficient for the change in criminal cases is −0.005 (p < 0.001, Model 6). As such, the effect is equal to 0.995 =

![]() $\{ {exp[\, {\hat{\!\beta} }]}\} = \exp [ { - 0.005}]$

in terms of hazard ratio. The estimated hazard ratio is less than one. This provides evidence that a conflict onset at a district level decreases as the survival time increases by 0.50% = (100 x (1-exp(−0.005))) for every 1% change in criminal cases compared to the national average (p < 0.001).

$\{ {exp[\, {\hat{\!\beta} }]}\} = \exp [ { - 0.005}]$

in terms of hazard ratio. The estimated hazard ratio is less than one. This provides evidence that a conflict onset at a district level decreases as the survival time increases by 0.50% = (100 x (1-exp(−0.005))) for every 1% change in criminal cases compared to the national average (p < 0.001).

Hypothesis 2 Suggests that districts with more civilian prosecution than the national average have an increased risk of the onset of armed conflict. Local elites can prosecute civilians to maintain political dominance and generate compliance. This persistent dominance intensifies shared grievances among peasants and civilians against the state, potentially leading to armed conflict. The estimated coefficient for change in the civil cases variable in Table 1 is positive and statistically significant across all models with at least a 99% confidence level. The estimated coefficient for the change in civil cases is 0.011 (p < 0.01, Model 6). In terms of the hazard ratio, this coefficient translates into 1.011 =

![]() $\{ {exp[ \,{\hat{\!\beta} } ]} \} = \exp [ {0.011} ]$

. The estimated hazard ratio is more than one, which suggests an increase in the risk of conflict onset; this suggests that a district-level risk of conflict onset increases by 10.61% = (100 x (1-exp((0.011*)))) for every 1% positive change in civil cases compared to the national average (p < 0.01).

$\{ {exp[ \,{\hat{\!\beta} } ]} \} = \exp [ {0.011} ]$

. The estimated hazard ratio is more than one, which suggests an increase in the risk of conflict onset; this suggests that a district-level risk of conflict onset increases by 10.61% = (100 x (1-exp((0.011*)))) for every 1% positive change in civil cases compared to the national average (p < 0.01).

The effect of change in criminal and civil cases compared to the national average is presented in Figure 3. Figure 3a presents the effect of change in criminal cases, and Figure 3b presents the effect of change in civil cases, one standard deviation above or below the mean value. As shown in these figures, in general, criminal prosecution effectively deters the onset of armed conflict. While the estimated survival curves for one standard deviation change from the mean value in both directions appear small, districts with an increase in such cases compared to the national average are less likely to see the onset of conflict. The effects are positive for civil cases. As shown in Figure 3b, a decline in the change in civil cases increases the survival time to the events compared to an increase in civil cases compared to the national average. The figures show that survival lines for the criminal cases start sloping downwards around nine years after entering the dataset, or around 1999, which is four years after the official start of the Maoist conflict in 1996. For civil cases, this pattern starts about two years early in 1997 or within a couple of years of the onset of the Maoist conflict.

Figure 3. Criminal and civil cases and the onset of armed conflict.

Among control variables used in empirical analysis, the population (log) variable is consistently positive and significant across all models (p < 0.001, Model 6). Among variables covering the geographical variations, the Hill region variable is positive and significant both in Model 4 and Model 6 compared to the Terai region. This finding confirms the role of rough terrain in providing a structural opportunity for the onset of armed conflict. All the control variables specific to the development regions – Eastern region, Central region, Western region, and Far Western region – are negative and statistically significant (p < 0.05) compared to the Midwestern region. As discussed earlier, the Midwestern region is where the Maoist conflict started and confirms the conflict’s expected spatial diffusion. Throughout the models, the variable life expectancy gap is negative but significant only in Model 4 (p < 0.001). In empirical analyses performed, the literacy rate gap, road density gap, political participation gap, absent population, caste and ethnic fractionalization, and mountain region variables are not significant.

All the models presented in Table 1 are tested for joint significance, where the coefficients are equal to zero. The p-value of the Wald tests is well below the 0.01 significance level (Appendix Table 4). The significance tests are performed individually for the main explanatory variables, change in criminal cases and change in civil cases. They are also below the 0.05 significance level (Appendix Table 4). Further, the empirical analyses are examined for the possibility of endogeneity bias, which is determined as less likely to influence the findings reported in the article.Footnote 3

8. Further tests

To substantiate the findings from the Weibull analysis, I did cross-sectional time-series probit and logit analyses, as the dependent variable, the district-level onset of the conflict, is a binary variable.Footnote 4 Models 4–7 in Table 1 are replicated and presented in Appendix Table 6. In this table, Models 7–9 are logit models, and Models 10–12 are probit models. All the variables that were consistently significant across all models in Table 1 are also significant across all models presented in these models. The absent population variable was not significant in the Weibull models in Table 1 but is consistently significant in all models. This variable is negative both in logit and probit models, suggesting a district with significantly more absent people has reduced odds of conflict onset. This finding is consistent with the anthropological narratives that people left districts for fear of prosecution and indoctrination before the Maoist group and the state forces clashed with each other (Onesto, Reference Onesto2005). Among control variables, the Mountain region is positive and significant in Model 7, which is different from the Weibull models presented in Table 1. Nevertheless, this variable is not significant in Model 9 nor the probit models (Models 10 and 12). Variables capturing five different development regions are not significant both in the logit and probit models. These findings are different from the findings presented in Table 1. The road density gap variable is significant in Model 7 (logit) and Models 10 and 12 (probit). All the findings reported in Appendix Table 6 are substantiated in joint significance tests that the estimated coefficients are equal to zero (null hypothesis). The null hypothesis is rejected in Wald tests (Appendix Table 7).

In Figure 4, the prediction of the onset of armed conflict is visualized for both the change in criminal and civil case variables as compared to the national average. This figure is generated based on Model 9 in Appendix Table 6. The figure shows the prediction of civil war onset, which increases as the gap in civil cases increases. On the other hand, as the gap in criminal cases increases, the onset of civil war decreases. While 71 out of 75 districts experienced onsets of armed conflict, the findings substantiate the divergent effects of direct and indirect ways the state can prosecute political opposition and the effectiveness of such strategies in containing the onset of armed conflict at the subnational level.

Figure 4. Change in criminal and civil cases and prediction of armed conflict onset.

9. Alternative explanations

The empirical analysis indicates that the state’s direct involvement through criminal cases is related to a decreased risk and indirect involvement through civil cases relates to an increased risk of armed conflict onset at the subnational level. However, the strengths of the state and rebel groups vary across localities, and there may be alternative explanations for the observed relationship. First, bringing criminal cases against political opposition in each district could signal state capacity. Logically, this should discourage rebel leaders from organizing a rebellion in that district. The empirical analysis might pick up those districts where the state was already strong. Second, and similarly, it could be difficult for the state to mobilize local elites on its behalf in those communities in those districts where rebels have stronger community ties. It is easier for the rebels to organize a rebellion against the state in those districts. Finally, after the initiation of the conflict in 1996, the decline in overall civil cases is likely because of the decreased ability of everyday people to use the district court. This decline could also relate to the use of the People’s Court, especially after the establishment of the People’s Government and People’s Court (Joshi, Reference Joshi2024). The Maoist group established a 35-member central-level people’s government on 23 November 2003, but the people’s government and people’s courts were already in place in a few districts (Shneiderman and Turin, Reference Shneiderman, Turin, Hutt and Bloomington2004).

10. Conclusion

This research builds on the previous study of the onset of armed conflict by developing a theoretical framework of how the state’s effort to, directly and indirectly, control the political opposition and civilian population through a court system can increase or decrease the risk of the onset of armed conflict. This framework is used to derive hypotheses, which were tested with the district-level year-over-year change in criminal and civil cases compared to the national average. Consistent with theoretical expectations, the risk of conflict onset was low in a district with a greater increase in criminal cases compared to the change in the national average. In contrast, the increase in civil cases increased the risk of conflict onset. In the empirical analyses, the underlying political and economic grievances measured in terms of literacy, life expectancy, and political participation had no substantial relationship with the onset of armed conflict.

One of the issues involving the subnational-level analysis of one country is the issue of generalizability of the findings or external validity (King et al., Reference King, Keohane and Verba1994; Findley et al., Reference Findley, Kikuta and Denly2021). The use of the court system to repress political opposition can happen anywhere (see Ginsburg and Moustafa, Reference Ginsburg and Moustafa2008), and therefore, the case of Nepal can be a common phenomenon. As such, future research can explore the validity of the theoretical argument in other cases beyond Nepal.

The findings in this research can be useful for designing early warning systems. Because states’ direct and indirect involvement in deterring political opposition and increasing civilian compliance to prosecute political opposition and gain legitimacy can be detected from subnational-level court data, national and international level human rights agencies can use this information to restrain the state from such practices and provide alternative approaches to gaining state legitimacy. Therefore, this advocacy can minimize the incidence of the onset of armed conflict or, in case such efforts fail, can also be useful in containing the spread of armed conflict and the level of violence. The findings can also provide helpful information to the civil war negotiation process on issues related to prisoner release, amnesty, and judiciary reform. These topics are tied to how the state and its local collaborators misuse the court. These are frequently negotiated provisions in civil war comprehensive peace agreements (Joshi and Darby, Reference Joshi and Darby2013).

The availability of subnational-level court data can also be useful to explore new research questions at the intersection of subnational-level violence and state legitimacy. Empirical research on service provisions suggests how violence depresses the delivery of public health services and school enrolments (Østby et al., Reference Østby, Shemyakina, Tollefsen, Urdal and Verpoorten2021), but how violence depresses the institutional legitimacy at the subnational level has never been explored. The use of court data can provide important insights into how armed conflict undermines or bolsters state legitimacy at the subnational level during and after the armed conflict. During the armed conflict, demand for legal remedies for damage and loss can be high when civilians are targeted and when the level of violence is high. Under such circumstances, if state legitimacy is there, there should be an increase in court cases. The court-level data can also be useful for exploring questions related to the regaining of institutional legitimacy in the post-conflict phase. It is also possible that the communities exposed to a high level of violence lack trust in state institutions. Therefore, it might take time for the state institutions to regain their legitimacy in such communities. These remain relevant research questions and possible ways this line of research can advance from here.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1468109925100194.

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge the travel and research grant support from the University of Notre Dame’s Research Office, Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies, and Liu Institute for Asia and Asian Studies. Grace Connors and Grace Sullivan provided excellent research assistant support. I am thankful for constructive comments and suggestions from Susan L. Ostermann, Keough School of Global Affairs at the University of Notre Dame; T David Mason, University of North Texas; Mehmet Gurses, University of Central Florida; and Sally Sarif, University of British Columbia. During the archival research process in Nepal between 2014 and 2021, I received tremendous help from many friends and government officials in Nepal. I remain grateful for their support.

Madhav Joshi is a Research Professor and Associate Director of the Peace Accords Matrix project at the Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies at the University of Notre Dame’s Keough School of Global Affairs. He is a faculty fellow at the Keough School’s Liu Institute for Asia and Asian Studies and the Pulte Institute for Global Development. His research focuses on comparative peace processes, peace agreement design and implementation, and the Maoist insurgency in Nepal. He has published on these topics in ranking political science and international relations journals. In collaboration with Catholic Relief Services-Philippines, he leads the Peace Accords Matrix–Mindanao technical accompaniment support to the Joint Normalization Committee in verifying the implementation of the Normalization Annex in the 2014 Comprehensive Agreement on the Bangsamoro. He is one of the principal investigators in the Kroc Institute’s mandate specific to verifying the implementation of the 2016 peace agreement between the Colombian government and the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia – Ejército del Pueblo (FARC - EP).