Introduction

June 25, 1982, was a disappointing day for many. The Senate in Illinois failed to approve the proposed Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) to the US Constitution. Despite personal appeals from President Carter, all-night vigils organized by the National Organization for Women (NOW), protests attracting multiple thousands to the Illinois State Capitol, and even a hunger strike organized by Catholics Act for ERA, the Senate by a vote of 31 in favor to 27 opposed, failed to approve the ERA for the fourth time. As in the House, a simple majority was insufficient: the support of three-fifths of senators was required for amendments to be approved, and opponents of the ERA had successfully blocked efforts to lower the threshold. After the Senate killed the amendment for the last time, some activists had an unprecedented tactic in mind. After the vote, nine members of the Champaign-based Grass Roots Group of Second Class Citizens stood in the gallery and chanted, “Senators, remember: we vote in November!” The members then proceeded to scrawl messages on the floor of the Capitol Rotunda using pig blood, including “[Governor] Thompson Remember.” The activists were then arrested and charged with criminal damage to state property. The arrests ended a series of protest events, including one where members of the group had chained themselves together in the capitol.

Despite all the rancor that the ERA votes attracted, there were significant lobby efforts outside of public view. After the ERA was proposed by Congress in 1972, organizations lobbied state legislators directly. Dozens of traditionalist organizations registered lobbyists in the states (Conover and Gray Reference Conover and Gray1983). Their lobby efforts often involved giving legislators personal gifts such as baked goods. Indeed, the pro-amendment coalition ERAmerica and its “stopper” opponents favored traditional lobby tactics largely outside of public view. In contrast, some organizations, especially the newly formed NOW, preferred protests since the tactic allowed the organizations to advocate for the ERA and also attract publicity (Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge1986). Although protest efforts received publicity, hundreds of individuals registered to lobby legislators regarding the amendment.

A significant number of scholars have examined mobilization surrounding the ERA, but important questions remain unanswered. It remains unknown how lobby efforts regarding the amendment varied over time and state, and whether the lobby efforts were effective in changing legislators’ votes. Much of the scholarly literature focuses on the nature of the mobilization itself. There are studies of how various organizations relied on different tactics, and studies of how the efforts of organizations were influenced by the presence of legislator allies (see Soule and Olzak Reference Soule and Olzak2004), but there are no statistical tests for whether organizations were successful in shifting legislators’ votes. So far, the only tests regarding mobilization effectiveness are those conducted by Soule and Olzak (Reference Soule and Olzak2004), who examined correlations between different kinds of mobilization (i.e., not lobby efforts) and states’ speed of approval.

Despite there being few tests for mobilization effectiveness, mobilization is a common explanation for the failure of the ERA. The amendment’s outcome has been attributed to various groups, including Phyllis Schlafly’s Eagle Forum and conservative women, and insurance companies, among others. According to Critchlow and Stachecki (Reference Critchlow and Stachecki2008, 165), for example, “If Schlafly had not entered into the fray, the ERA would have been ratified.” According to Smeal and Steinem (Reference Smeal and Steinem2020), however, “Phyllis Schlafly and her followers were credited with stopping the ERA, rather than the insurance industry and other economic interests that stood to lose billions if the ERA passed… Quite the contrary….” Given the benefit of hindsight, which groups today might we blame for the ERA’s failure? Are other factors, such as public opinion, instead responsible for the amendment’s demise? In this study, I measure the effectiveness only of lobby efforts. I do not measure the effectiveness of other mobilization tactics, such as the sponsorship of advertisements and newsletters.

Examining legislative votes on the ERA provides an opportunity for scholars to detect influence. When Congress proposed the amendment, it gave state legislatures seven years to consider the proposal. Legislators were unable to amend the text of the ERA, although some approved of modified versions of the amendment. The amendment thereby provides an opportunity to detect influence since legislators in all states considered the same proposal, but with different numbers of lobbyists present at different times. To detect influence, I examine the lobby activities of numerous organizations said to have advocated for or against the amendment, and the presumed effects of those efforts on legislators’ votes (see Boles Reference Boles1979; Conover and Gray Reference Conover and Gray1983). The lobby efforts are identified using lists of registered lobbyists spanning 374 legislative sessions that occurred between 1969 and 1982. First, I examine differences in lobby efforts across time and states to determine if mobilization occurred in specific states and sessions, as suggested by nearly all accounts (e.g., Boles Reference Boles1979; Conover and Gray Reference Conover and Gray1983; Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge1986). I then turn to legislators’ votes on the ERA and analyze a data set composed of 6,952 votes cast on the amendment by state legislators between 1973 (when opposition first mobilized) and 1982. The votes are gathered from legislative journals and newspapers and used to determine if particular lobbyists’ effects were confined to single political parties, as suggested for other forms of mobilizations (Soule and Olzak Reference Soule and Olzak2004). The results suggest that numbers of explicitly pro- and anti-ERA lobbyists who registered were correlated with ERA votes among Republican but not Democratic legislators in expected directions, and that numbers of women’s group lobbyists or insurance lobbyists were not correlated with votes among any legislators. To help determine who stopped the ERA, these findings are used to estimate probabilities that various legislators would have voted for or against the ERA had no lobbyists appeared.

This study is the first to examine lobbying on the ERA across both time and states, and the first to seek to measure the effects of lobbyists on the state ratification decisions regarding an amendment to the national constitution. Only one other study (e.g., Conover and Gray Reference Conover and Gray1983) examines registered lobby efforts regarding the ERA, and the analyses in that study examine efforts from a single year and do not attempt to detect influence. As well, only one other study (e.g., Hill Reference Hill1983) examines trends in legislators’ votes on the ERA, and the analyses there examine only a subset of votes. By contrast, this study presents a comprehensive examination of lobbying on the ERA and, importantly, attempts to detect influence over roll call votes by detecting correlations. In other words, this study advances scholars’ understanding in multiple ways of who may have stopped the ERA, and provides new empirical evidence to ongoing debates over who was responsible for the failure of the amendment.

The findings have implications for politics today. The ERA is not completely dead. Congress formally proposed the amendment and sent it to the state legislatures for ratification on March 22, 1972. Approval from 38 states was required for the amendment to become ratified, and Congress initially granted the states seven years to reach this threshold. An additional three years were granted by Congress for ratification, but the ERA was not approved by the requisite number of legislatures. Within the past decade, however, four states have taken action on the amendment: legislatures in Virginia, Illinois, and Nevada all ratified the amendment between 2017 and 2020. Moreover, North Dakota’s legislature rescinded its prior ratification in 2021.Footnote 1 In total, the amendment has now been ratified by the requisite number of state legislatures, and Congress could, by majority vote, lift the 1982 deadline and instruct the Archivist of the United States to recognize recent ratifications. In March 2021, the House voted to lift the deadline. Given that additional states may choose to ratify or rescind, or that Congress may take action on the amendment, the findings suggest that lobbyists may have some ability to influence contemporary outcomes regarding the amendment. Moreover, numerous state constitutions have their own equal-rights provisions, and voters consider adopting such provisions for additional constitutions on occasion, most recently in Nevada in 2022 (see Migdon Reference Migdon2022). Lobbyists may have some influence over such amendment processes as well. Indeed, “coalitions are now working to pass state-level ERAs” (Smeal and Steinem Reference Smeal and Steinem2020).

Trends in amendment lobbying

Most amendments of the national constitution were considered and approved in state legislatures, where lobbyists regularly work. Among the 27 existing amendments, Congress sent all but one to state legislators for approval.Footnote 2 Scholars have sought to identify interests that affected the decisions of state legislators regarding proposed amendments. For example, Baack and Ray (Reference Baack and Ray1985) and Barney and Flesher (Reference Barney and Flesher2008) found that states with more veterans and agricultural interests approved of the proposed income-tax amendment sooner than other states. Urban and Catholic interests may have helped encourage the repeal of the prohibition amendment (Dinan and Heckelman Reference Dinan and Heckelman2014), and organized Catholic and farming interests may have undermined the proposed Child Labor Amendment (Greene Reference Greene1988). None of these studies directly observed lobbying related to the proposed amendments. Rather, the studies employed proxy variables for mobilization.

Research produced by political scientists and others suggests several trends that might be observed among lobby efforts related to the ERA or even other proposed amendments. Perhaps most obviously, organized interests are said to have targeted states in which their efforts could have presumably had some effect. Since legislators could vote on the ERA multiple times prior to approving but not retract their decisions to ratify, organized interests would have directed their efforts toward states that had not yet approved of the ERA, but with some distinctions. Brasher, Lowery, and Gray (Reference Brasher, Lowery and Gray1999) present evidence that more interests lobby state legislators when there is some chance of policy change. In other words, there is little reason to lobby when the stakes are low. Moreover, according to Denzau and Munger (Reference Denzau and Munger1986), there is little reason for a group to lobby if legislators are likely to support the group’s cause in any case, including due to favorable public opinion. This suggests that, where public support for the ERA was strong, there was little reason to lobby. Indeed, 30 states approved of it within one year of its formal proposal by Congress. There likely was little mobilization regarding the ERA in these states. Over time, however, public approval of the ERA gradually declined (Soule and Olzak Reference Soule and Olzak2004). This suggests that advocates and detractors may have focused their efforts on remaining states, particularly those where legislative outcomes were unclear.

Historical accounts suggest that legislators in some states, indeed, were lobbied more often than legislators elsewhere. By the spring of 1977, or after Indiana’s legislators had approved of the ERA, the national coalition ERAmerica identified several states as being most likely to ratify: Florida, Illinois, Missouri, Nevada, North Carolina, and Oklahoma (Dinges Reference Dinges1977). Illinois proved to be a particular hotbed for ERA activism (see Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge1986, 165–77), and legislators in Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, North Carolina, and Virginia all experienced intensive lobby efforts (Baker Reference Baker2015; Boles Reference Boles1979, 72–82; Carver Reference Carver1981; Matthews and De Hart Reference Matthews and De Hart1990; White Reference White1989; Young Reference Young2007). Not all of the states that failed to approve of the ERA were targeted equally. No or few accounts suggest that legislators in Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, or Utah were likely to approve, and no accounts accordingly suggest that legislators in those states experienced large numbers of lobby efforts.

There is historical evidence that different organizations engaged in lobbying to different degrees, but the accounts of such lobby efforts do not imply hypotheses that may be tested easily. Lobbying was not the only tactic that organizations relied upon for advocating for or against the ERA, but it was a prominent tactic. After Congress proposed the amendment in 1972, an “ERA Action Committee” composed of delegates from NOW, the National Woman’s Party, Common Cause, League of Women Voters (LWV), and National Federation of Business and Professional Women’s Clubs (BPW) formed to coordinate state advocacy efforts. By June 1973, the committee had assigned roles to the member organizations: NOW would use outside pressure tactics, the Party would seek to elect pro-ERA candidates to state legislatures, Common Cause would distribute issue papers, and the League would train lobbyists. Although “not much coordination occurred” (see Berry Reference Berry1986, 66–67), these roles reflected the historical strengths of the organizations and may have shaped subsequent mobilization efforts. NOW and the National Women’s Political Caucus (NWPC) were new and aimed to recruit members. These new organizations spurred members to take direct action on the ERA (Conover and Gray Reference Conover and Gray1983; Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge1986), which brought greater attention to the new organizations. Long-standing women’s groups (e.g., LWV and American Association of University Women [AAUW]) were more comfortable with traditional lobby tactics, given the size of their existing membership bases, and also endorsed the ERA more slowly (Boles Reference Boles1979, 48–50). Organizations associated with Schlafly and the New Right did not rely exclusively on lobbying but also organized protests and sit-ins (Conover and Gray Reference Conover and Gray1983, 90). Groups of the New Right pioneered political action committees and direct-mail fundraising (91). Although these accounts provide rich detail into the efforts of the various organizations, there are unclear implications regarding which organizations relied on lobbying more than others.

To determine just how much lobbying pertained to the ERA and if some states saw more lobby efforts than others, lobbyist registration records were collected from archives in all states for 374 legislative sessions (i.e., sessions with existing records) that occurred between 1969 and 1982. The records identify the organizations that lobbied legislators and the number of lobbyists they employed during each session. Based on other studies that identify pro- and anti-amendment groups (e.g., Boles Reference Boles1979; Conover and Gray Reference Conover and Gray1983), numbers of lobbyists that registered to advocate for or against the ERA explicitly during each session were calculated, as well as numbers of lobbyists who represented women’s organizations that took stances for the ERA but who may not have lobbied legislators specifically regarding the amendment. Forty-five states required lobbyists to register with state authorities by the time Congress proposed the ERA in 1972. The five states that did not require lobbyists to register by that year were Idaho, Hawaii, Nevada, Utah, and West Virginia; however, all these states adopted registration statutes by 1975. The registration records produced by lobbyists provide insight into the scale and locations of lobbying on the ERA. Lists of registered lobbyists and clients, or registration records, were collected from archives and libraries in all states where records were available or from newspaper articles that published lists of registered lobbyists. Some lists from 1973 and 1975 are from Reitman and Bettelheim (Reference Reitman and Bettelheim1973) or Marquis Academic Media (1975), respectively. In total, the lists span 374 legislative sessions that occurred between 1969 and 1982 in all states, but with unequal coverage across states. Whereas lists were found for every session that occurred during the period for 12 states, no lists were found for Hawaii.Footnote 3

Lists of registered lobbyists are useful for two reasons. First, the lists indicate which individuals were authorized to represent which client organizations during each legislative session. Second, the lists provide a glimpse into the individuals and interests active during sessions on an unprecedented scale. As noted previously, one other study examines registered lobby efforts related to the ERA, but the study examines lobbyists active during 1975 (see Conover and Gray Reference Conover and Gray1983, 176). There are some drawbacks to using the lists. The lists include only individuals who personally solicited legislators. Therefore, the lists do not include individuals who organized protests or testified before committees but who did not meet individually with legislators, such as Phyllis Schlafly herself. Registration criteria also differed across states somewhat, with a small number of states requiring only paid agents to register. The lists continue to provide useful information, however, since lobby laws changed rarely in the states and the effects of such criteria may be parsed statistically.

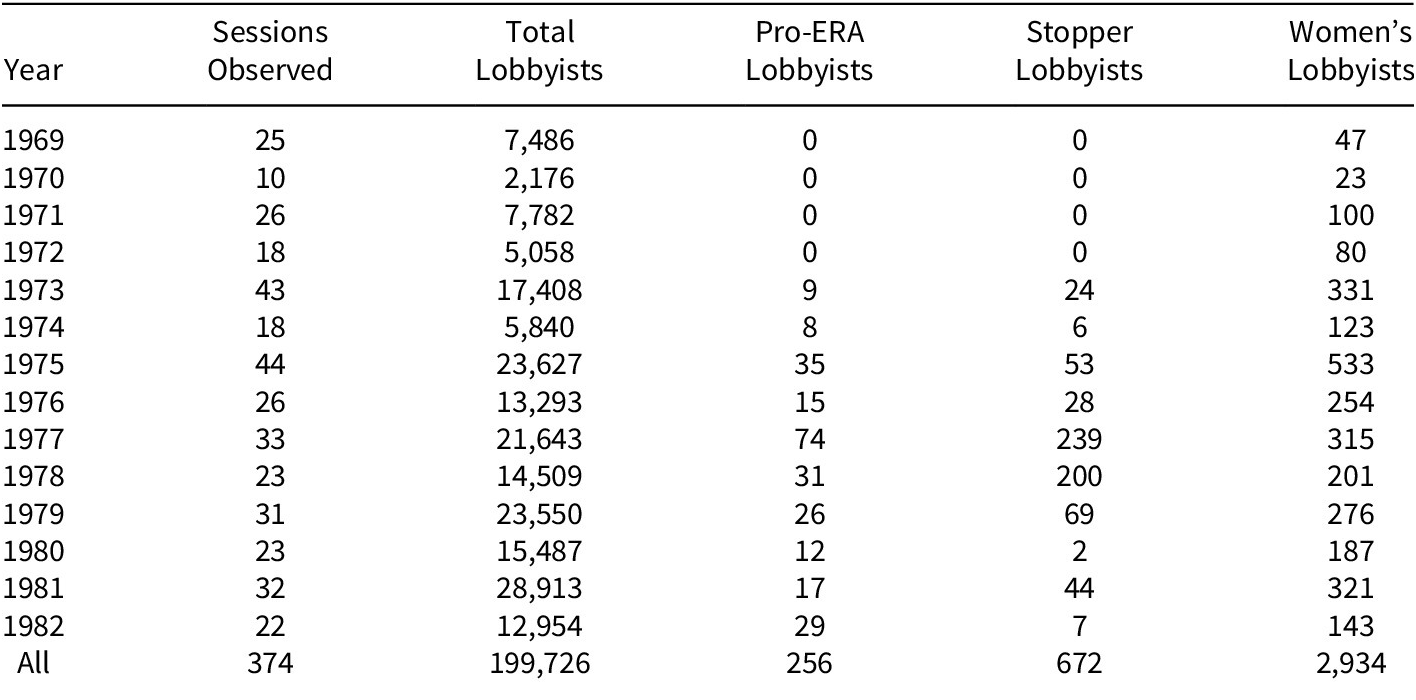

To demonstrate the scale of ERA lobbying, Table 1 reports the total number of lobby contracts or efforts that appeared in registration records for each year between 1969 and 1982. Contracts are combinations of individual lobbyists and individual clients. As shown in Table 1, numerous advocates registered to lobby. Since individuals could register as representing causes instead of organizations (and indeed numerous individuals registered regarding the ERA but did not provide organization names), contracts capture the total scale of lobbying in a capitol regarding an issue (see Strickland Reference Strickland2019). As shown in Table 1, for guidance, lobbyist lists from 25 sessions were located for 1969. In that year, a total of 7,488 lobby contracts were registered. Among those, zero were related explicitly to the ERA. This should be expected, given that Congress did not propose the ERA until 1972. In 1973, lobbyists active on the amendment began to appear. In that year, there were nine explicitly pro-ERA lobbyists and 24 anti-ERA lobbyists in the states. Such contracts consist of those that mention the ERA as a cause, include the ERA within the organization’s name, or are related to an organization formed exclusively for the purpose of ratifying or defeating the ERA, as listed by Boles (Reference Boles1979, 200–2) or Conover and Gray (Reference Conover and Gray1983). Examples of organizations that focused primarily on the amendment include ERAmerica, Happiness of Womanhood, STOP ERA (later Eagle Forum), and Women Who Want to be Women, among others. The lobbyists for these organizations were active in addition to the 316 representatives of various women’s organizations who may have lobbied legislators regarding the ERA in 1973: the AAUW, BPW, LWV, NOW, and NWPC, among others. During the 374 sessions for which lobbyist lists could be located, a total of 928 explicitly ERA-related lobby efforts were registered, or roughly 0.46% of all lobby efforts registered.

Table 1. Lobby contracts by year

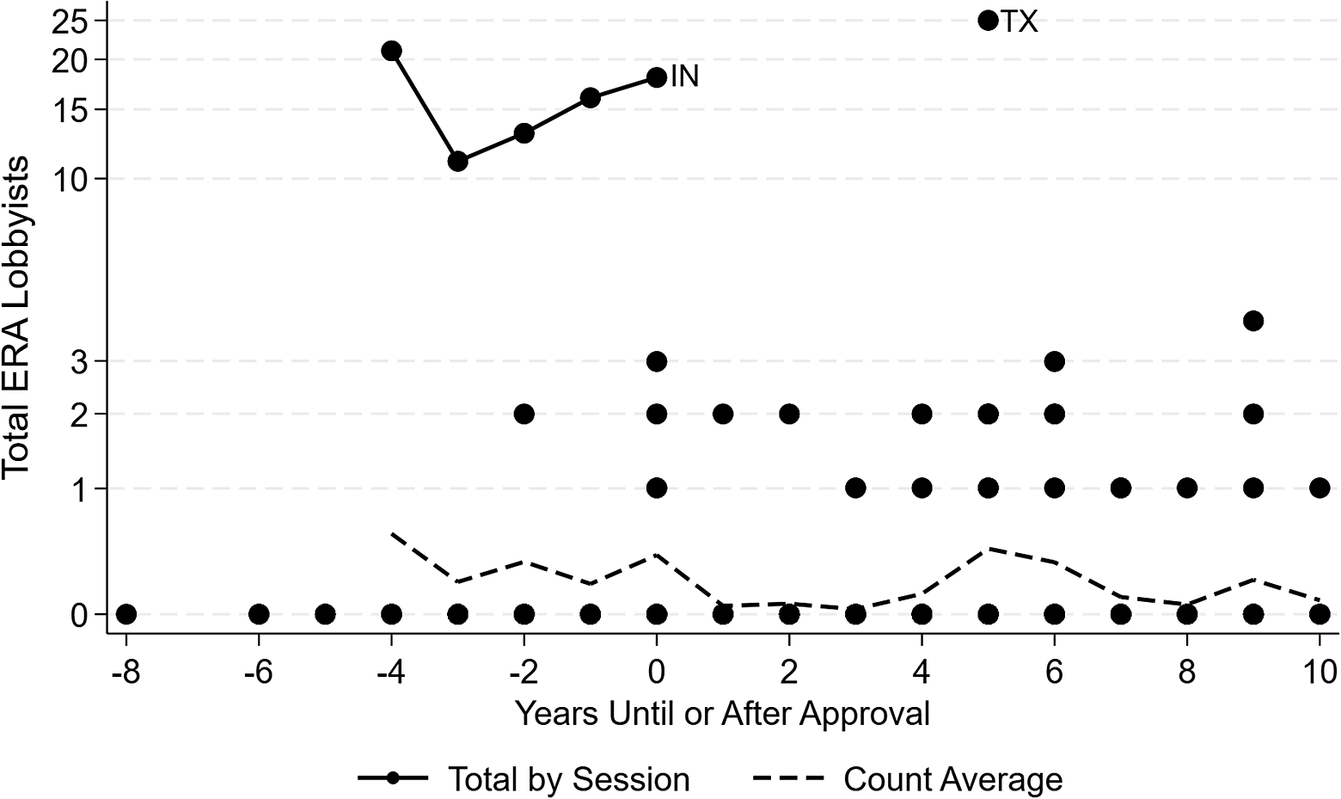

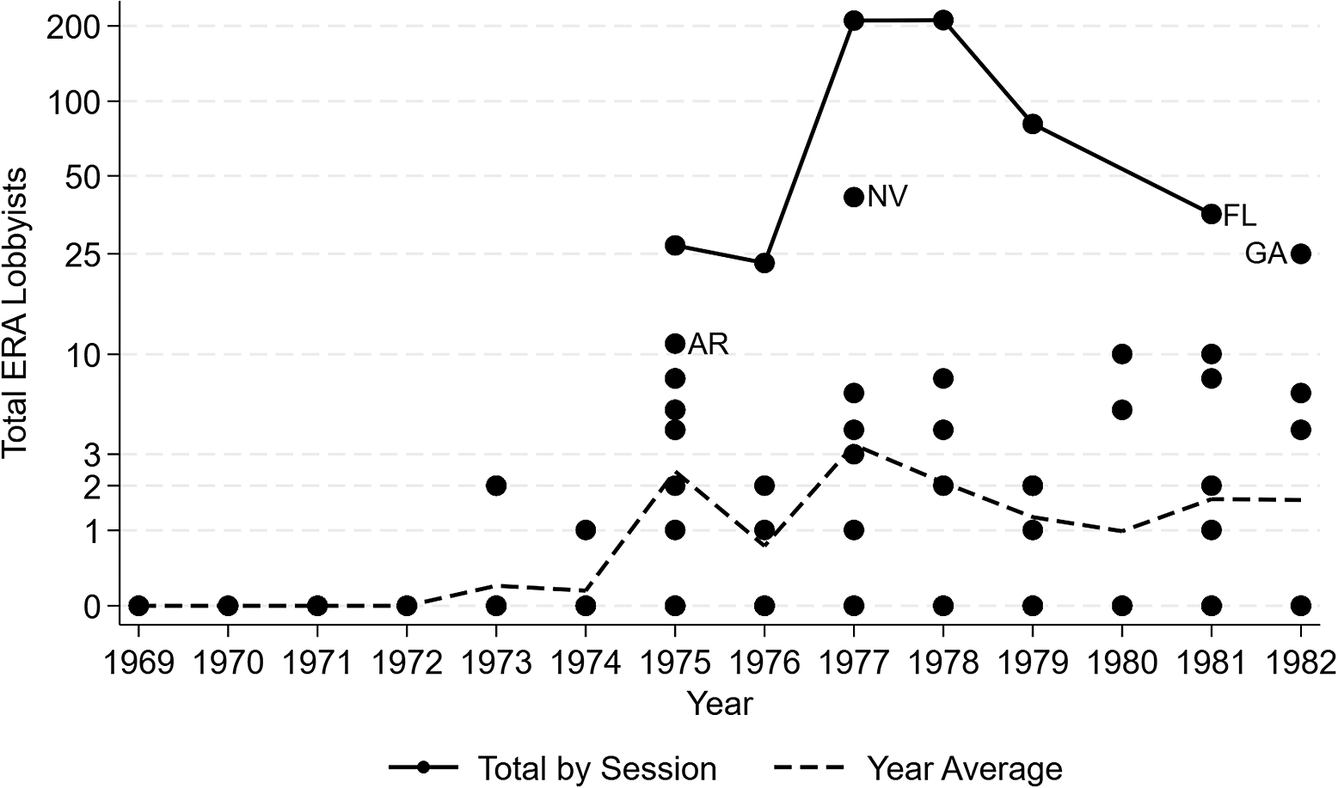

To determine if ERA lobbyists focused on particular states, Figures 1 and 2 present scatterplots of total ERA lobby efforts (i.e., pro- and anti-amendment) per session across time. Note that the vertical axes are not scaled linearly. Figure 1 presents lobby efforts by year in states that approved of the amendment at some point before 1983. Each dot represents a single observed legislative session (although dots from different states overlap), and the dashed line provides the average number of lobby efforts for each year among the sessions observed. Sessions are ordered according to the number of sessions before or after the session in which legislators approved of the ERA. As shown in Figure 1, there were few lobby efforts in states that approved of the amendment, with the exceptions of Indiana and Texas. Indiana was the last state to approve of the ERA before 1982, doing so in 1977 after a protracted lobby battle lasting five years. After that, practically no ERA lobbyists appeared in the state. In Texas, numerous members of Women Who Want to Be Women, an anti-ERA group, registered as lobbyists in 1977. The legislature had considered a rescission resolution two years earlier. The other states in which ERA lobbyists appeared after ratification include Kansas, Minnesota, Montana, and West Virginia, but lobbyist numbers never exceeded four. In contrast, from the second figure, it is evident that non-ratifying states saw the bulk of ERA lobby efforts. In accordance with Mansbridge (Reference Mansbridge, Snow, della Porta, Klandermans and McAdam2013, 421) and others, lobbying on the ERA did not begin in earnest until 1973. Some states are outliers. During two sessions in Florida, more than 200 individuals registered to lobby for or against the amendment. Lobby efforts spiked in Arkansas in 1975, Nevada in 1977, and Georgia in 1982. Despite Illinois presumably being a battleground, fewer than 10 individuals registered in that state each year.

Figure 1. Lobby efforts across ratifying states.

Figure 2. Lobby efforts across non-ratifying states.

Expectations for influence

The previous section demonstrated that hundreds of individuals registered to lobby state legislators regarding the ERA and that their numbers were concentrated in particular states and sessions, but it remains unknown if the various lobbyists’ efforts had any effects on state legislators’ votes. In examining voting trends on the amendment, I propose that the effects of various factors, including lobby efforts, were contingent on the partisanship of legislators. Partisanship itself may have had direct effects on ERA votes by state legislators due to the stances of the parties. Between its initial introduction in Congress in 1923 and its failure in 1983, the parties and organized interests that supported or opposed the amendment shifted. The Republican Party platforms endorsed the ERA between 1940 and 1980, while the Democratic Party platforms endorsed the ERA in 1944 and after the early 1970s (Freeman Reference Freeman2000). Support for the amendment was largely bipartisan when it was formally proposed by Congress in 1972, but the Democratic Party warmed to the amendment further as support among Republicans faded. Importantly, partisanship may have interacted with other factors, particularly lobbying, to determine legislator votes. Soule and Olzak (Reference Soule and Olzak2004) argue that “…policy outcomes are likely to be the result of a number of contingent and interactive forces over and above the main effects of [social] movements” and other factors. They attribute the success of movements regarding the ERA to the political-opportunity structure in each state, and, in particular, the presence of co-partisan allies in legislatures. Such success may be due to movement activists providing information to allies (Burstein and Linton Reference Burstein and Linton2002). Indeed, Soule and Olzak (Reference Soule and Olzak2004) find evidence that the efforts of the AAUW and anti-ERA groups were more effective in legislatures with more Democrats or Republicans, respectively.Footnote 4

Importantly, although hundreds of individuals registered to lobby for or against the ERA explicitly, insurance interests are said to have opposed the amendment on the grounds that it would prevent insurance companies from charging men and women different premiums (Critchlow and Stachecki Reference Critchlow and Stachecki2008). Smeal and Steinem (Reference Smeal and Steinem2020) argue explicitly that insurance lobbyists successfully undermined the ERA in state legislatures: “[h]ealth insurance interests alone stood to lose billions if the ERA forced it [sic] to stop charging women more for less coverage, and since that industry was largely state-regulated, it had lobbyists in every state capital.” Further, “…Schlafly was only window dressing. The anti-ERA fix was already in…. Phyllis Schlafly and her antifeminist homemakers had been brought in to cover for legislators who were voting against the ERA anyway.” Smeal and Steinem also argue that corporate interests opposed the ERA in general since it would have required them to pay men and women equally for the same work. Hence, in addition to the efforts of pro- and anti-amendment activists, the lobby efforts sponsored by the insurance industry might have had some effect on legislators’ votes.

The amendment may have created a context ripe for counteractive lobbying, and that such lobbying, if it occurred, has the potential to obscure correlations between lobby efforts and votes cast by ostensible legislator allies. Ainsworth (Reference Ainsworth1997) suggests that counteractive lobbying, or when competing advocates seek to influence the votes of the same legislators, may occur when issues are “contentious and openly debated, [thereby] reducing the opportunities for legislative bargaining and log-rolling,” when outcomes are binary or involve stark legislative choices, and when issues do not recur (526). As an example, Ainsworth (Reference Ainsworth1997) and Austen-Smith and Wright (Reference Austen-Smith and Wright1994) claim that such lobbying occurred during the confirmation battle over Robert Bork. Decisions regarding the ERA did not enable legislators to bargain with one another easily (as with tax policy) or spur lobbyists to focus only on their ostensible allies, but the amendment was a recurring issue in some states. If advocates and detractors of the ERA solicited the same legislators frequently, then correlations between their lobby efforts and co-partisan legislators’ votes should be less discernible statistically.

The personal traits of individual legislators might have mattered for their support for the ERA. Hill (Reference Hill1983) theorized that partisan affiliations may have had weaker predictive power over the votes of women legislators on the ERA than over the votes of men legislators. Hill suspected that women legislators demonstrated weaker attachment to party cues on issues, such that votes cast by women legislators on the ERA would reflect partisan cues less strongly than votes cast by men. Moreover, legislators’ racial or ethnic backgrounds might have determined votes. Legislators from populations traditionally excluded from politics might have been more inclined to support the ERA due to generalized support for civil rights, but such a difference might also have been due to constituency effects (see Wohlenberg Reference Wohlenberg1980). Surveys reveal that African-American voters were more supportive of the ERA in the 1970s than others (see Burris Reference Burris1983; Huber, Rexroat, and Spitze Reference Huber, Rexroat and Spitze1978), so legislators representing those voters might have been more supportive of the ERA as well. Moreover, the link between party and ERA votes may have been weakened somewhat by race or ethnicity, given that non-white Republican legislators supported the ERA due to generalized support for civil liberties or constituency effects. No existing studies determine if partisanship and race have interactive effects on ERA votes.

Finally, levels of public support may have mattered for votes on the ERA. If state legislators seek to be reelected, and if votes on the ERA were salient or highly publicized, then such votes should have presumably been correlated with public opinion on the ERA in legislators’ districts. There is significant evidence that legislators seek reelection (Erikson, Wright, and McIver Reference Erikson, Wright and McIver1993; Mayhew Reference Mayhew1974). With regard to salience, roll call votes on the ERA were often published in newspapers, so legislators had some incentives to vote according to their constituents’ preferences. Public support for the amendment differed over time, particularly across parties; therefore, the effect of public opinion itself may have varied across parties. Recall that support for the ERA was largely bipartisan when Congress formally proposed it in 1972. Over time, support declined (Soule and Olzak Reference Soule and Olzak2004), and Critchlow and Stachecki (Reference Critchlow and Stachecki2008) attribute this decline, in particular, to the publicity efforts of Phyllis Schlafly. Schlafly was adept at sowing doubt regarding the effects of the ERA. During televised interviews, she argued that the amendment’s ratification would force Congress to require women to sign up for the draft and lead to universal unisex bathrooms. By the late 1970s, Democrats and Republicans had very different views of the ERA: 62% of Democrats and 42% of Republicans favored the ERA (Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge1986, 215). Unfortunately, district-level statistics regarding ERA support are unavailable, but if legislators reflected the majority parties of their districts, then Democratic legislators might have continued to support the amendment despite broader declines in public support as Republican legislators came to vote increasingly in line with public support in general (which was brought down over time by declines in support among Republicans specifically).

Hence, I propose that partisanship did not temper the effectiveness of lobby efforts exclusively but also may have affected the links between ERA votes and legislators’ personal traits and public support for the ERA. Legislators in all states were members of the national Democratic and Republican Parties, and support for the ERA shifted throughout the 1970s within the traditional bases of support for the parties. The platforms of the parties came to reflect the preferences of their supporters regarding the amendment. As a result, the effects of lobbyists, traits, and public support for the ERA were all contingent on the partisanship of legislators.

Data

A data set consisting of roll call votes by state legislators on the ERA that occurred between 1973 and 1982 was constructed. The data set was restricted to those years since the ERA was immensely popular when it was proposed by Congress, and, from Table 1, lobbyists did not mobilize in earnest until a year later. Only after Congress proposed the ERA did Phyllis Schlafly organize STOP ERA and the amendment began to attract the attention of various lobbyists. It was not until July of 1972 that the “national campaign against ERA” began “when Schlafly called… [her] Illinois supporters to a one-day meeting at the O’Hare Airport Inn” (Critchlow Reference Critchlow2005, 219). Schlafly founded STOP ERA in September. The organization was renamed the Eagle Forum in 1975, and “[b]y the late 1970s, Schlafly was leading all the anti-ERA campaigns in the 15 unratified states” (Conover and Gray Reference Conover and Gray1983, 74). Moreover, the sample of votes is limited since roll call votes that occurred in 1972 were largely supportive of the amendment, so there is also limited variation in votes from that year. A few legislative chambers (e.g., the senates in Massachusetts, Michigan, and Oklahoma) even employed unrecorded voice votes to register their approval.

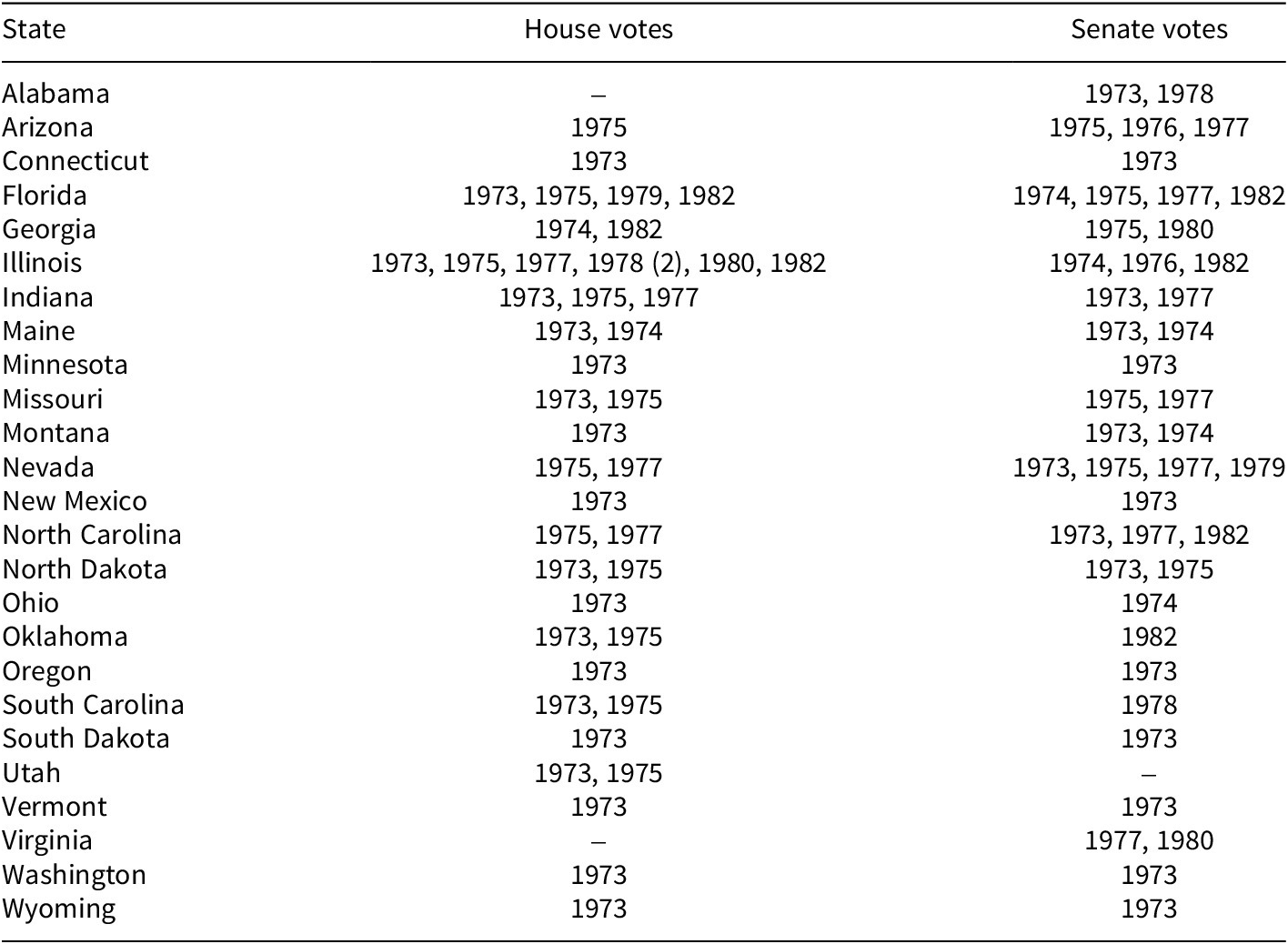

Table 2 lists the roll call votes in the data set. The roll calls were found in an issue brief by Gladstone (Reference Gladstone1980) and various other sources, including newspaper articles. There were a total of 87 roll calls comprised of 6,952 individual votes, including pairs in which legislators were absent but nonetheless indicated how they would have voted on the ERA. Legislators’ votes themselves were compiled from legislative journals and newspaper clippings. Only 25 states are listed since the others approved of the ERA prior to 1973. In the table, votes in lower chambers are separated from those in upper chambers. For example, representatives in Alabama never voted on the ERA, whereas senators voted on and rejected the amendment twice: in 1973 and 1978. Only in Illinois did two votes ever occur during a single session. The table does not include roll calls to rescind prior ratification decisions, present the ERA to voters, or on modified versions of the ERA.Footnote 5 The roll calls listed in Table 2 also do not include committee actions.

Table 2. ERA roll call votes, 1973–1982

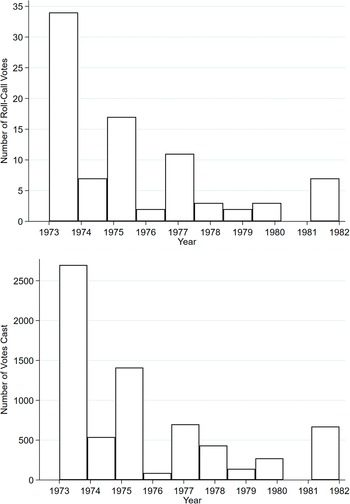

Figure 3 presents histograms showing when ERA roll call votes occurred and the numbers of individual votes cast by legislators during each year. As shown in Figure 3, the bulk of votes were cast in 1973 or 1975. The bumps for odd-numbered years are due to state legislatures not convening during even-numbered years. No votes were cast in 1981. Although roll call votes decreased in frequency over time, there was a final burst of activity in 1982 when seven legislative chambers considered the ERA one last time, including the two in Illinois. The data set is the largest such set of roll call votes on the ERA compiled to date. In comparison, Hill (Reference Hill1983) examined only 37 roll call votes in which majorities in the parties disagreed.

Figure 3. ERA votes over time, 1973–1982.

Lobby statistics that are aggregated at the level of states were appended to the data set. Lobbyist lists were located for 80 of the 87 sessions in which ERA votes occurred, which include 6,682 or 96.1% of the 6,952 votes that were cast.Footnote 6 The first statistic consists of totals of pro-ERA lobbyists or only those who advocated for the amendment explicitly, including lobbyists for ERAmerica and various state-based coalitions, among others. The second statistic consists of anti-ERA lobbyists or stoppers, including those associated with Happiness of Womanhood, STOP ERA (later Eagle Forum), and Women Who Want to Be Women, among other organizations. To test the hypothesis of Smeal and Steinem (Reference Smeal and Steinem2020), the data set includes totals of insurance lobbyists, including all lobbyists for health, life, and property insurance companies, including the Farm Bureau. I control for the total number of lobby efforts during every session.

The partisanship and personal traits of legislators were identified and included in the data set. Partisan affiliations were collected from Klarner et al. (Reference Klarner, Berry, Carsey, Jewell, Niemi, Powell and Snyder2013), who compiled a data set of historical election returns in the states. In Minnesota, where legislators did not campaign as Democrats or Republicans prior to 1973, legislators were classified based on their caucuses (see Masket Reference Masket2016). Women legislators were identified using a comprehensive directory of women state legislators (i.e., Cox Reference Cox1995). The ethnic or racial backgrounds of legislators in the data set were collected from Klarner (Reference Klarner2021).

To detect the effects of public opinion, public approval ratings of the ERA for the states were collected from Soule and Olzak (Reference Soule and Olzak2004). I thank Sarah Soule for providing the public opinion data. In the words of Soule and King (Reference Soule and King2006, 1885), the “data come from Gallup polls conducted in 1974, 1975, 1976, 1978, 1980, 1981, and 1982… which were obtained from the Roper Center for Public Opinion Research.” Such data are available only for years prior to a state’s decision to ratify, so the closest available measures in states that ratified were used where needed.

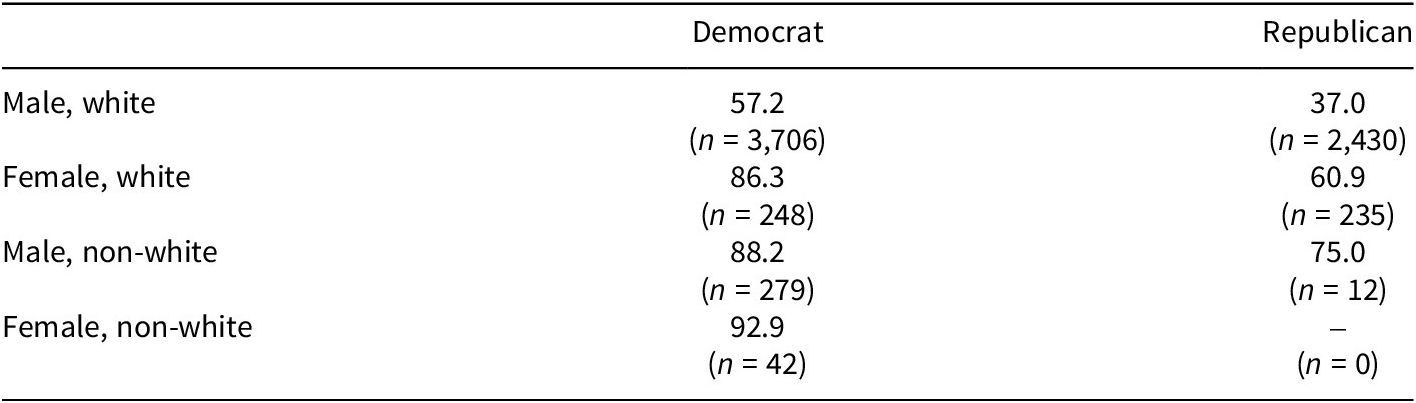

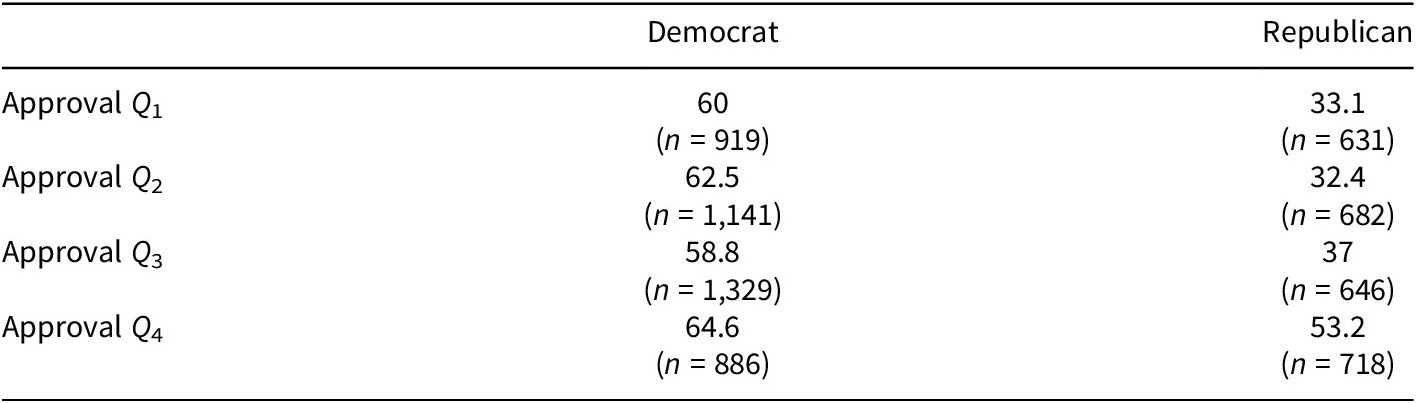

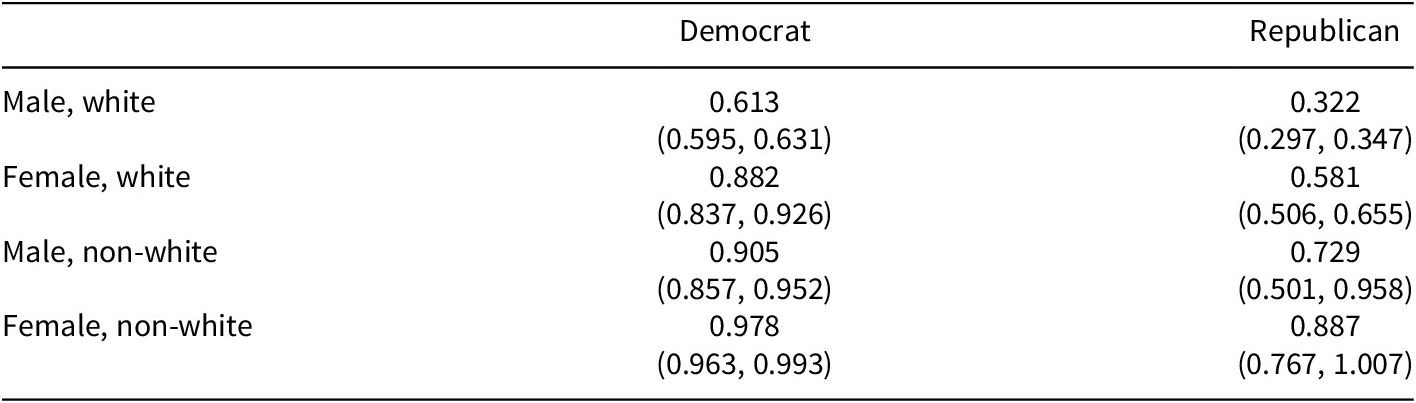

Prior to conducting any statistical tests for influence, various descriptive statistics regarding the propensity to vote for the ERA among various groups of legislators based on party, gender, race, and public opinion are presented. Table 3 presents the percentages of legislators in each group who voted in favor of the ERA (as opposed to voting against it, abstaining, or being absent). The columns parse legislators by party, whereas the rows parse legislators by combinations of gender and race. Each cell indicates the percentage voting in favor of the ERA and the number of observations within each category. As shown in Table 3, for example, roughly 37% of the votes cast by Republicans who were white men were cast in favor of the ERA. There were 2,430 votes cast by such legislators in the data set. This percentage contrasts with that for Democratic women who were non-white. Nearly 93% of the votes cast by these legislators were cast in favor of the amendment. The data set includes no Republican women who were non-white. Similarly, Table 4 reports the percentages of votes cast in favor of the ERA by party and different quartiles of public support for the amendment, with the first quartile, including the observations with the lowest levels of support. Support among Democrats was high, at least compared to support among Republicans, for all four quartiles of public opinion. Even in the lowest quartile, 60% of Democrats voted for the ERA. This amount shifted slightly to 64.6% in the fourth quartile. Republican support increased from 33.1% to 53.2% across the quartiles.Footnote 7

Table 3. Percent votes for ERA by party and traits

Table 4. Percent votes for ERA by party and approval

The numbers presented in Tables 3 and 4 consist of votes and not unique legislators. Numerous legislators cast multiple votes since they served over multiple sessions. Among the 6,952 votes cast, there were 4,392 unique legislators. A majority of legislators (2,735 or 62.3%) saw only one roll call while in office. A small number (143 or 3.3%) of legislators served so long in the Illinois House that they had five, six, or seven opportunities to vote for the ERA. Among legislators who had two or more opportunities to vote for the amendment, 256 or 15.4% changed their stance at some point. Of those, 150 legislators voted for the ERA before voting against it or abstaining, and 106 shifted the other way.

Tests for influence

To determine if lobbyists and other factors were correlated with votes, a series of logistic regression models were estimated in which the dependent variable for each model is a binary indicator for whether a legislator voted in favor of the ERA. Given that fewer than 3% of legislators abstained or did not cast ERA votes at all, and for the sake of simplicity, a binary outcome variable (i.e., “yes” vote or otherwise) and logistic regressions were used rather than multinomial logistic regressions. Given the central role of the party in my expectations, three models are estimated: a model for Democrats, a model for Republicans, and a combined model. In the combined model, various interactive terms that test for whether the differences in coefficient values between Democrats and Republicans are statistically different from zero are included. Each model includes state and year effects. The state effects capture the effects of time-invariant factors unique to each state that are not included explicitly in the models, and the year effects capture national averages in legislators’ overall propensity to vote for the ERA for each year. The standard errors are clustered by session and chamber since some legislators may have changed their votes in response to the votes of other legislators. As an example, factional conflicts among Democratic lawmakers in Illinois led to the demise of the ERA in that state (see Critchlow and Stachecki Reference Critchlow and Stachecki2008). For interpreting the results presented in Table 5, note that legislators change from year to year. The coefficients for legislator-level variables (e.g., party, gender, and race) reflect overall differences across groups of legislators in propensities to vote for the ERA. The coefficients are not based on changes in votes within individual legislators or even among groups of legislators over time.

Table 5. Predicting legislators’ votes for ERA, 1973–1982

Note. State and year effects were included in all models but not reported. Clustered errors are reported in parentheses.

* p < 0.1.

** p < 0.05.

*** p < 0.01 on two-tailed tests.

As shown in the models, different factors were correlated with votes from Democrats and Republicans. Among Democratic legislators, no lobby efforts were correlated with votes. Rather, women and non-white legislators were more likely to vote than men and white legislators, respectively. Democratic legislators voted more often for the ERA as state-level public support was lower. For Republicans, lobby efforts mattered. Votes by Republicans were correlated positively with pro-ERA efforts and negatively with stopper efforts. As with Democrats, women and non-white legislators were more likely to vote for the amendment than other Republicans. The first model has slightly more explanatory power than the second. The results presented in Model 3 confirm the results from the first two models. The results are largely the same, and the coefficients for various interactive terms indicate that the differences in coefficient values for Democrats and Republicans (for the direct effects) are themselves statistically different from zero. Specifically, members of the parties reacted differently to explicitly pro- and anti-amendment lobby efforts, gender, and levels of public opinion. The difference between white and non-white voting for the ERA was similar across both parties, even if Democrats (Republicans) were generally more (less) likely to vote for the amendment.

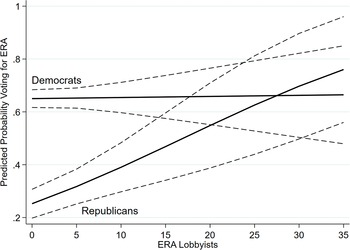

Pro- and anti-ERA lobbyists had somewhat countervailing effects on party differences in voting. Whereas pro-amendment lobbyists helped to narrow the partisan gap in ERA voting, stoppers widened the gap. According to Model 3, for every additional ERA lobbyist who appeared, the odds of Republicans voting for the ERA relative to all other legislators increased by 5% on average, ceteris paribus. For each stopper lobbyist, the odds of Republicans voting for the ERA decreased by 1.7%. Note that these are changes in odds ratios and not relative risks. Figures 4 and 5 present the predicted probabilities that white, male legislators in different parties voted for the ERA for different numbers of amendment advocates and stoppers. All other variables are held at their means, except for public support, which is held at 50%. The probabilities are calculated based on the results of Model 3. As shown in Figures 4 and 5, ERA lobbyists narrowed the partisan divide in amendment voting, whereas stoppers widened it, and the effects of both groups of lobbyists were confined to Republicans. There is no evidence presented that insurance lobbyists affected ERA votes.

Figure 4. Predicted probabilities of voting for ERA by party and ERA lobbyists.

Figure 5. Predicted probabilities of voting for ERA by party and stoppers.

Given the binary measures of legislator traits, Table 6 presents the predicted probabilities of legislators in different groups to have voted for the ERA, along with 95% confidence intervals, based on Model 3. The probabilities are generated when all other variables are held at their mean values. As expected, these probabilities mirror the actual averages presented earlier, but the confidence intervals for some estimates are quite large due to small subsamples.

Table 6. Predicted probabilities of voting for ERA by party and traits

Figure 6 presents the predicted probabilities of white, male Democrats and Republicans voting for the ERA under different levels of public support and when all other variables are held at their means. The negative (positive) correlation between Democratic (Republican) votes and public opinion is evident. As mentioned, these correlations may be due to legislators representing majority parties from their districts and shifts in opinions on the ERA among Republicans.

Figure 6. Predicted probabilities voting for ERA by party and opinion.

The results presented in Model 3 cannot be used easily to determine if Schlafly “actually changed any votes,” as Smeal and Steinem (Reference Smeal and Steinem2020) deny, or if “Schlafly… [had] not entered into the fray, the ERA would have been ratified,” as suggested by Critchlow and Stachecki (Reference Critchlow and Stachecki2008, 165), because of statistical imprecision; however, they provide some predictive utility. Note that the logistic regressions estimated in Table 5 all predict at least 66% of ERA votes, or assign probabilities of voting for (against) the ERA greater (less) than 50% to legislators who actually did vote for (against) the amendment. Based on Model 3, in a counterfactual scenario in which no stoppers appeared in any states, the predicted probabilities of legislators voting for the ERA do not change for 78.96% of legislators. This is likely because most legislators were Democrats who were unaffected by any lobbyists and zero or few stoppers appeared in most states. For only 61 votes, all in Florida but during different years, did the predicted probabilities of legislators voting “yes” increase from under 50% to above that threshold. Most of those votes were cast against the ERA, whereas 18 were in favor. This suggests that stoppers might have persuaded or pressured 43 legislators to vote against the amendment. In a counterfactual scenario in which no pro-ERA lobbyists appeared, the predicted probabilities of legislators voting for the ERA do not change for 50.28% of legislators. This may be due to these lobbyists being more effective than stoppers (when one compares coefficients in Model 3) and having appeared in more states than stoppers. Nevertheless, the number of legislators who had a 50% chance or greater of voting for the ERA and whose predicted probabilities decreased below that threshold is only 32. These legislators all served in Georgia, Illinois, or Nevada, and 10 voted against the amendment. Hence, pro-ERA lobbyists may have persuaded or pressured 22 legislators to vote for the amendment.Footnote 8 Therefore, lobbyists likely had small effects on votes, if any, and did not change outcomes in the states. Reaching this conclusion requires us to assume that legislators would not have changed their votes based on how other legislators voted, including legislators in other states.

Robustness checks

The 6,952 votes in the sample were cast by 4,392 unique legislators since many legislators voted on the ERA multiple times. Although fewer than 16% of legislators who cast multiple votes changed their stance at some point, models in which only the initial votes of legislators are examined were estimated. The results from these models are each based on single votes from unique legislators such that no individual legislator’s multiple votes skew the estimates. The estimates for these models are reported in Table 7. The trends reported in the table largely mirror those reported earlier in Table 5 but are somewhat less discernible statistically. I continue to find that Democrats were largely unaffected by the efforts of lobbyists, while Republicans responded somewhat to stopper efforts. Differences in slopes are still not equal to zero, as expected. Gender and race mattered for legislators’ initial votes, just as in Table 5, but one of the most noticeable changes across the two tables is the estimated effect size for public opinion on Democrats’ votes. Whereas there is a negative and statistically discernible relationship between opinion and Democrats’ votes in Table 5, the relationship disappears in Table 7. The correlation between opinion and Republican votes also becomes weaker. Since legislators cast subsequent votes during later years in most cases (i.e., only one session ever featured more than one roll call), the findings regarding lobby efforts and public opinion suggest that Democrats continued to vote for the ERA despite declines in public support for the amendment, Republicans began to shift against the amendment as opinion changed, and lobbyists’ influence grew over time as Republican legislators began to reconsider their support for the ERA.

Table 7. Predicting legislators’ first votes for ERA, 1973–1982

Note. State and year effects were included in all models but not reported. Clustered errors are reported in parentheses.

* p < 0.1.

** p < 0.05.

*** p < 0.01 on two-tailed tests.

In Table 8, correlations between lobby efforts and votes among legislators separated by region are examined. Differences between non-Southern and Southern states are examined since legislators who served in office in the South, particularly Democrats, are commonly found to differ from their non-Southern counterparts in terms of ideology. In particular, such legislators were found to be more conservative than Democrats not from the South (Shor and McCarty Reference Shor and McCarty2011; Reference Shor and McCarty2022). The first three models reported in the table examine legislators from non-Southern states. As with the models presented earlier, logistic coefficients are estimated, and errors are clustered by session. Regarding lobby efforts, trends among non-Southern Republicans conform best to my expectations: No efforts are correlated with votes among non-Southern Democrats, but lobbyists, including insurance lobby efforts, are correlated with the votes of non-Southern Republicans. As shown in the additional models in the table (which examine votes only in Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Virginia), such trends are absent or reversed among Southern legislators. Regarding traits, gender mattered for votes among all four groups of legislators, although differences in slopes are not discernible across parties. Also, only non-Southern Republicans voted in accordance with public opinion (see Table 8).Footnote 9

Table 8. Predicting legislators’ votes for ERA by region, 1973–1982

Note. State and year effects were included in all models but not reported. Clustered errors are reported in parentheses.

* p < 0.1.

** p < 0.05.

*** p < 0.01 on two-tailed tests.

Discussion

This study presented evidence that lobby efforts related to the ERA affected some votes cast by Republican legislators but ultimately did not cause the failure of the amendment. By compiling a data set consisting of 6,951 roll call votes and lobby efforts covering more than 96% of those votes, a series of regression equations in which the dependent variable was the vote cast on the ERA by each legislator were estimated. There was consistent evidence across 12 equations that pro- and anti-amendment lobbyists affected the votes of Republicans. The regressions revealed more consistent evidence, as well, that legislators who were women or non-white were more likely to vote for the ERA regardless of party, and that Republican legislators began to vote against the amendment as public support for it faded. This study is the first to estimate the effects of lobby efforts and personal traits on the ERA votes of state legislators, or even on the votes of legislators for any proposed amendment to the national constitution.

The findings have implications for constitutional reforms other than the proposed ERA. I encourage others to consider how state-based interests may have affected the design of the national constitution. It may be the case that organized interests affected the votes of legislators on other proposed amendments, and therefore possibly affected the content of the constitution. As mentioned earlier, no other study examines the effects of interests on legislators’ roll call votes regarding proposed amendments. The methods used in this study may easily be applied to roll calls on other amendments, particularly those proposed during and since the Progressive Era, when states adopted lobby registration laws. Some of the amendments that were ratified present a paradox: By approving some amendments, particularly those related to the income tax, popular election of senators, and various voting rights, the state legislatures empowered the national government (see Gerber and Kollman Reference Gerber and Kollman2004). The efforts of organized interests, including tactics involving pressure and persuasion, might help explain why state legislators supported amendments that centralized power in the national government and ostensibly reduced their own powers. Moreover, organized interests may have pressured legislators to vote against some amendments that were not ratified, such as the Child Labor and District of Columbia Voting Rights Amendments. It remains to be determined if organized interests actually affected the content of the national constitution via lobbyists, but this study presented evidence that lobby efforts at least made no difference regarding the proposed ERA. Rather, the amendment might have been ratified had there been more Democrats, women, and non-white people serving in the state legislatures.

What might the findings suggest about today’s debates over the ERA? Recall that legislators in three states have approved of the amendment, and legislators in one state have rescinded a prior approval since 2017. Recall also that various state constitutions feature their own versions of the ERA. The findings suggest that voting trends on the amendment became more closely associated with party in the 1970s as Republican support faltered. Based on these findings, voting trends on the amendment may have become more closely aligned with party over time. It is unsurprising that the three legislatures that recently endorsed the ERA were controlled by Democrats, whereas the one that rescinded its approval was controlled by Republicans. It is unclear if lobbyists could achieve the same levels of influence today as in the 1970s. Rather, the shift in the Republican Party was brought about because of, or provided an opportunity for, stoppers.

There remain limitations to the present study. For one, this study examined only the effects of lobby efforts. Yet, organizations engaged in efforts other than lobbying. Conover and Gray (Reference Conover and Gray1983) discovered political-action committees related to the ERA, and Soule and Olzak (Reference Soule and Olzak2004) counted numbers of newsletters released by state chapters of the NOW. As the first paragraph of this study suggests, groups organized various other efforts on occasion: vigils, protests, and hunger strikes. There is no comprehensive data set of mobilization efforts related to the ERA, so it remains unknown if lobby efforts were correlated with some other kinds of tactics, and therefore if the correlation between partisan voting and lobbying is spurious. The best insight existing data sets provide is that pro-amendment lobby efforts were not correlated with NOW newsletters, as shown in the Supplementary Material. A possible extension of this study includes a comprehensive documentation of various mobilization efforts besides lobbying. Since Schlafly and other stoppers may have relied on tactics other than lobbying, I cannot disprove that had “Schlafly had not entered into the fray, the ERA would have been ratified” (as suggested by Critchlow and Stachecki Reference Critchlow and Stachecki2008, 165). The other tactics might have made a difference, as Soule and Olzak (Reference Soule and Olzak2004) suggest.

Another limitation of the study’s design is that it is impossible to determine if pro- and anti-ERA lobbyists truly affected legislators’ votes since they may have lobbied legislators selectively. For instance, the lobbyists may have appeared more often in states where partisan gaps were greatest since they perceived more opportunities for influence in those states. To an extent, the other explanatory variables help capture legislators’ general likelihoods of voting for the amendment, and therefore may capture lobbyists’ perceptions of legislators’ levels of support, but the single-equation models presented in this study do not account for the possibility of targeted lobbying (see Smith Reference Smith1995). Indeed, Smeal and Steinem (Reference Smeal and Steinem2020) suggest that lobbying occurred selectively when they claim that “Schlafly and her antifeminist homemakers [were] brought in [as] cover for legislators who were voting against the ERA anyway.” It may be worthwhile to identify an instrument for lobby efforts, such as other kinds of mobilization efforts, to account for the possibility that efforts were targeted.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/spq.2025.10006.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Bruce Ruan for invaluable research assistance and three anonymous peer reviewers.

Data availability statement

Replication materials are available on SPPQ Dataverse at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/7TRRDO.

Financial support

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Competing interests

The authors declared no potential competing interests with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author biography

James Strickland is an Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science at Florida State University. He received his Ph.D. from the University of Michigan in 2019.