7.1 Introduction

Ireland stands out as a critical case study for exploring the dynamics of policy triage, offering compelling evidence within our broader theoretical framework. Among the six countries studied, Ireland exhibits the most significant within-case variation, making it an intriguing subject for testing our theoretical arguments. Variation is especially pronounced among central-level actors, where the differences in the frequency and intensity of policy triage activities are starkly evident. This distinct contrast provides a rich context for understanding the factors that contribute to or mitigate against the need for policy triage.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Pensions Authority (PA) exemplify agencies that effectively navigate policy implementation with minimal recourse to triage. Their status as independent agencies affords them protection from excessive workload surges, underpinned by a robust commitment to overload mitigation. This stands in sharp contrast to the National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS), which epitomizes the opposite end of the spectrum. Hindered by a lack of mechanisms to prevent blame-shifting, scarce opportunities for resource mobilization, and a low compensatory commitment, the NPWS is compelled to engage frequently in severe triage to manage its workload.

The Department of Social Protection (DSP) occupies an intermediate position, experiencing contained and infrequent triage activities. While the DSP is somewhat shielded from uncompensated workload allocation and blame-shifting, it faces challenges in mobilizing additional resources, and its commitment to overload compensation does not match the levels observed in the EPA and PA.

Furthermore, the distinction between actors at the local and central levels highlights the unique challenges faced by local authorities. The administrative and geographical separation from central-level formulators facilitates blame-shifting toward local implementers for policy failures, simultaneously constraining their ability to secure additional resources. Moreover, the inherent complexity of being multifunctional organizations dilutes policy ownership and impedes the cultivation of a strong esprit de corps among local authorities.

Ireland’s experience thus encapsulates the entire spectrum of policy triage, from minimal to frequent and severe instances, and underscores the explanatory potential of our causal mechanisms in determining the degree of triage activities. The findings affirm our theoretical proposition that low levels of triage are predominantly a function of reduced vulnerability to overload and heightened compensatory commitment, while high levels of triage, as seen in the NPWS, result from a combination of high vulnerability and low compensatory capacity. The DSP and local authorities represent intermediate cases, offering nuanced insights into the conditions that mitigate or exacerbate the propensity for policy triage.

In this chapter, we delve deeper into the patterns and variations in policy implementation in Ireland, shedding light on the complex interplay of factors that shape policy implementation and triage in practice. We begin with an overview of Ireland’s implementation arrangements in the environmental and social sector and give a detailed account on the extent of policy triage for different implementation bodies. Based on this assessment, the following sections focus on the explanation of varying triage patterns across different agencies and governmental levels (Section 7.2). First, we scrutinize why the two independent agencies responsible for environmental policy and pension policy on the central level engage in little to no triage (Section 7.3). In a second step, we focus on the DSP and the NPWS as two central-level agencies whose patterns of policy triage deviate remarkably from the low levels observed at the EPA and the PA (Section 7.4). Third, we turn to the local level and investigate how the central-local divide affects policy triage in the Irish City and County Councils (Section 7.5). We conclude with a summary of the triage situation in Ireland and a discussion of the theoretical implications resulting from our analysis (Section 7.6).

7.2 Structural Overview: Environmental and Social Policy Implementation in Ireland

The Irish administrative system is characterized by institutional continuity, with its development revealing rather stable general patterns (MacCarthaigh et al., Reference MacCarthaigh, Biggins and Hardiman2023). Ireland maintains the Anglo-Saxon state and administrative traditions, where policy is formulated at the national level and implemented by central agencies and local authorities for the most part (O’Malley & MacCarthaigh, Reference Hardiman, MacCarthaigh, Eymeri-Douzans and Pierre2011). Generally, the Irish civil service operates in a context of low levels of politicization and stable governments (Hardiman & MacCarthaigh, Reference Hardiman, MacCarthaigh, Eymeri-Douzans and Pierre2011). These stable features of the administrative system partially contrast with more dynamic developments at the political level, however. Recently the once-stable two-party system with either Fianna Fáil or Fine Gael leading two- or three-party coalition governments has come under pressure by the emergence of the left-wing Sinn Féin and the Green Party. To avoid a left-wing government, Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael joined forces for the first time in 2020 and formed a majority government with the Green Party. The latter was able to punch above its weight (or votes) due to its role as kingmaker and consequently pushed for a greener government agenda.

The implementation structure is coined by a distinct divide between the local and the central level. Over time, the local government has surrendered numerous functions and competencies to the central level (Forde, Reference Forde2005). As a result of the 2008 financial crisis and following reforms to the public sector, supervision of local administrations has been centralized. Formed in 2011, the Department of Public Expenditure and Reform took over the responsibility for public spending from the Department of Finance. The newly formed department is not only the deciding actor with regard to the public sector’s budgetary affairs but also human resource management. In addition, local authorities are overseen by the Department of Housing, Local Government, and Heritage. Consequently, resource arrangements in the environmental and the social sectors are fairly homogeneous.

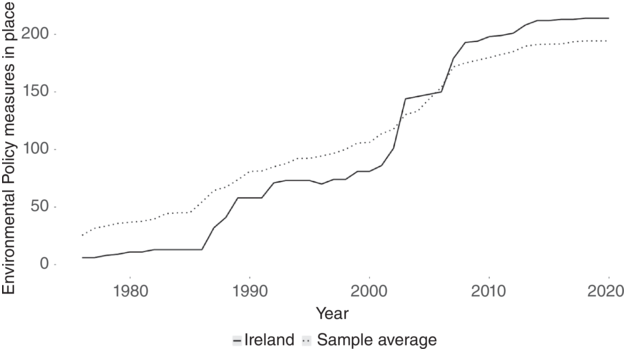

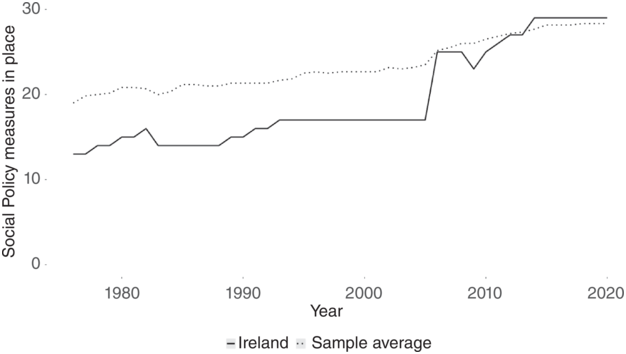

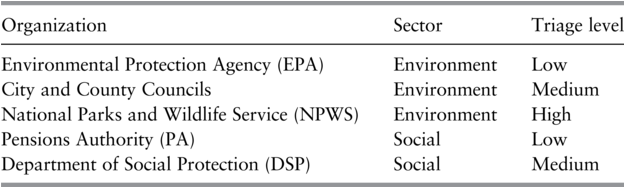

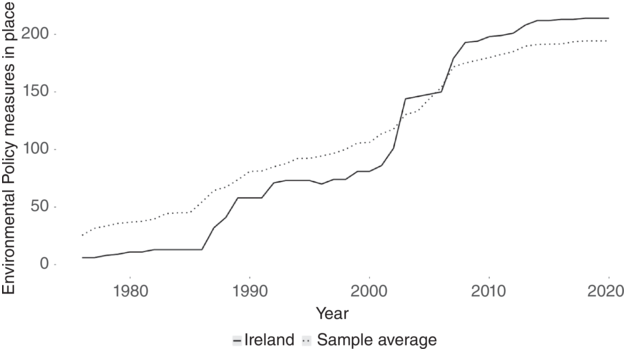

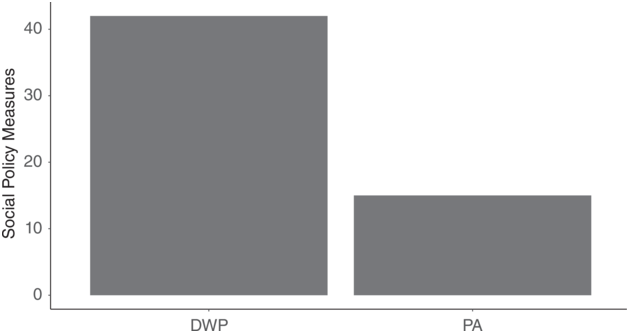

Regarding the two policy areas under study, this broader context in which implementation bodies are operating coincides with pronounced patterns of policy growth. For environmental policy, Ireland reveals a more dynamic growth pattern compared to the average pattern of the six countries under study from the early 2000s (see Figure 7.1). Turning to social policy, the country remained below the sample average for most of the time until the mid-2000s. As a result of the financial crisis in 2008, the dismantling of several measures took place. However, following its recovery from the fallout of the financial crisis, Ireland surpassed the sample average of social policy measures in place for the first time in 2012 (see Figure 7.2).

Figure 7.1 Environmental policy measures in Ireland.

Figure 7.2 Social policy measures in Ireland.

7.2.1 Competence and Burden Allocation in Environmental Policy

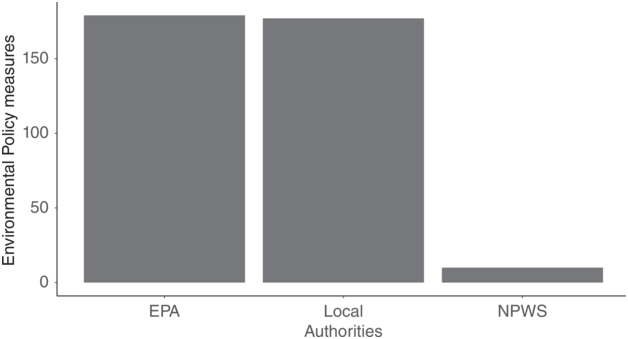

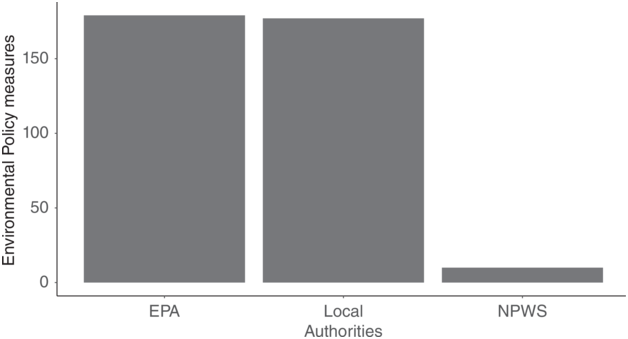

The environmental policy landscape in Ireland is dominated by three key actors: the EPA, the local City and County Councils, and the NPWS. While the latter is primarily responsible specifically for the field of nature conservation, the EPA and local authorities have broader responsibilities. Figure 7.3 displays the share of tasks within the Irish environmental portfolio implemented by the three organizations. The large part of policy measures falls within the mandate of the EPA and the local authorities. The share of the NPWS is comparatively small; however, this is centrally due to the fact that our conceptualization of environmental policy is rather narrow, chiefly encompassing air, water, and nature conservation. This pointed focus inadvertently minimizes the apparent scope of the NPWS’s responsibilities, which extend beyond these areas. The organization is tasked with implementing a broader array of policies that fall outside our framework, including various licensing schemes related to hunting and the import and export of wildlife and plant life, for example.

Figure 7.3 Environmental policy measures per organization.

The EPA, to begin with, is Ireland’s central environmental agency. Before the organization entered service in 1993, environmental policy in Ireland was almost exclusively implemented by local authorities. Yet, with the increasing number and complexity of environmental legislation, City and County Councils became more and more overburdened. Due to disparity in local capacities, implementation realities on the ground varied broadly as certain authorities would engage heavily in selective implementation while others were able to compensate for policy growth (Scannell, Reference Scannell1995). Regulated entities – industry and agriculture for the most part – “suffered from having to deal with unexpected and unpredictable variance from one region to another” (Shipan, Reference Shipan2006: 11). However, implementation was not only hindered by a lack of enforcement capacity but also by a conflict of interest as local authorities were often major polluters themselves while also acting as regulators (Coyle, Reference Coyle1994; Taylor & Murphy, Reference Taylor, Murphy and Taylor2002). Pollution by local authorities, originating in community-run wastewater treatment plants, for example, was outside the scope of the regulatory framework, essentially allowing them to circumvent standards they were enforcing themselves (Cahill, Reference Cahill2010; see also European Commission, 2007). Overall, public trust in local authorities’ ability to protect the environment was rather low. To remedy the situation, the newly elected Fianna Fáil–Progressive Democrats coalition started putting plans together for the creation of an independent environmental regulator based on a broad consensus among policymakers across parties, industry, and environmentalists (Shipan, Reference Shipan2006).

With the Environmental Protection Agency Bill introduced in 1992 – and in line with diagnoses on the “rise of the regulatory state” in Europe (Levi-Faur et al., Reference Levi-Faur, Kariv-Teitelbaum and Medzini2021; Majone, Reference Majone1994, Reference Majone1996; see also Thatcher, Reference Thatcher2002) – the EPA entered service in 1993. Initially, its core mandate included the licensing of all significant industrial activities, reporting on drinking water quality, urban wastewater treatment, and landfill management; the operation of national air and water monitoring programs as well as monitoring duties regarding the performance of statutory environmental protection functions by local authorities and environmental monitoring activities of public authorities (Lynott, Reference Lynott2013; OECD, 2020b). In addition to its regulatory role, the agency was also tasked with the promotion and coordination of environmental research as well as the provisions of advice to the central government and local authorities; the EPA was also to serve as a liaison with the European level (Shipan, Reference Shipan2006). In subsequent years, the agency was allocated more and more responsibilities. It was designated Ireland’s “Competent Authority” for several European Union (EU) directives, making it the central actor for licensing and enforcement of policies relating to waste, water, and emissions trading schemes. The statutory functions assigned to the EPA grew from 5 in 1993 to about 135 in 2012 (Lynott, Reference Lynott2013: 2), which is a marked increase in workload but also shows the agency’s growing relevance in Irish environmental policy implementation.

A distinct characteristic of the EPA is that its independence was one of the core founding principles. Policymakers across party lines agreed to equip the prospective environmental regulator with significant autonomy:

The independence of the agency is guaranteed by a number of important elements. First, the executive board is selected by an independent committee. The agency will also have an effective and expert staff and the freedom to act of its own volition. It will have sole and direct responsibility for licensing a wide range of activities and, lastly, it will be an offence under this Act to lobby any member of the board or employee of the agency with the intention of influencing improperly a matter to be decided by the agency (Seanad Éireann, Volume 127, 23 January, 1991; Environmental Protection Agency Bill, 1990: Second Stage (resumed) as cited in Shipan, Reference Shipan2006: 16).

Providing the EPA with such high levels of autonomy was particularly surprising for two reasons. First, the EPA only was Ireland’s third independent agency (after the Central Bank and the Commission for Electricity Regulation); second, a government department formally responsible for this policy area already existed and could have easily facilitated an implementing branch, as was the case for nature conservation or social policy. Nonetheless, policymakers decided to create an arm’s-length body. The reasoning covered three central aspects: shifting responsibility away from policymakers, showing credible environmental commitment, and generating and providing expertise on environmental issues (Shipan, Reference Shipan2006). Ultimately, these considerations also helped the organization to become the strong and credible advocate it is at present. Sufficient organizational slack and resources in combinations with high levels of expertise enabled the EPA to develop its profile as a respected regulator and overarching authority in Irish environmental matters and beyond.

Aside from the EPA, the thirty-one Irish City and County Councils are responsible for the implementation of a wide range of measures stemming from the European and national level – despite centralization of environmental policy that culminated in the creation of the EPA. The environmental mandate of local government covers a range of low-risk, low-impact tasks, including municipal waste, water supply, and wastewater collection and treatment (OECD, 2021c). In 2021, the more than 500 staff members of local authorities issued 16,400 licenses, permits, and certificates, undertook 205,100 environmental inspections, and engaged in 20,880 enforcement actions. Furthermore, they dealt with 80,800 complaints and initiated 630 prosecutions (EPA, 2023: 26). Staff distribution across tasks focuses on waste, where 68 percent of the workforce is engaged in, followed by water (24 percent), air, noise, and other areas (8 percent) (EPA, 2023: 4).

Lastly, the NPWS is Ireland’s central agency for nature and biodiversity. It was established in 2003 following the dissolution of Dúchas, which held responsibility in this area since 1995. The NPWS has a fairly broad mandate: It oversees six national parks, seventy-four nature reserves, and other state-owned land; the implementation of EU biodiversity and conservation programs as well as the coordination of the National Biodiversity Action Plans. Furthermore, the NPWS is tasked with scientific research, a range of regulatory and licensing functions such as hunting or import and export of wild animals, as well as the investigation and prosecution of wildlife crimes. Lastly, its mandate also comprises the administration of grant schemes in the area of conservation, biodiversity, and control of invasive species (Kearney, Reference Kearney2022).

The scope and responsibilities of the NPWS widened massively since its creation. Centrally, “increasing obligations under EU law, a succession of adverse findings against Ireland by the European Court of Justice, Government and public expectations, the impact of unprecedented development activity on biodiversity/natural heritage and a growing land management responsibility” (Kearney, Reference Kearney2022: 14) has caused the organization to struggle as resources were not allocated at the same pace. Regarding its status and position within the Irish public administration, the NPWS presents a bit of an odd case: “as a constituent ‘Division’ of its ‘home’ department, it is neither an agency nor an independent body” (Department of Housing, 2021: 34), or as an interviewee put it, “it’s always been a bit schizophrenic, in its place within a government department. People have taken different views of whether or not it’s a separate organization” (p. 14). While the organization has a relatively modest annual budget of 12.5 million euro (2021), this does not include resources for its staff of 354 full-time employees, which are provided by its parent department (Kretsch, Reference Kretsch2021: 4). Consequently, the use of potential slack resources would always require coordination with the NPWS’s principal.

7.2.2 Competence and Burden Allocation in the Social Sector

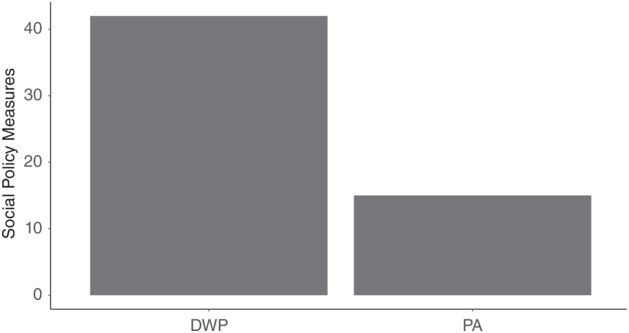

In contrast to the environmental sector, competences in the Irish social sector are more centralized. The lion’s share of policies under study (pension, unemployment, and child benefits) is implemented by the DSP see figure 7.4. In addition, the PA oversees and regulates Ireland’s vast landscape of pension funds and programs.

Figure 7.4 Social policy measures per organization.

Among the Irish implementation organizations scrutinized, the DSP stands out since it combines the position of a policy formulator and implementer within one organization. With a staff size of about 6,500, the organization is one of the largest in the Irish public sector and administers the greatest share of government spending via its programs (IRE10). The DSP largely provides its services via a network of 126 INTREO Centers spread across the country. In 2012, the DSP incorporated the Community Welfare Services and the Training and Employment Authority (Foras Áiseanna Saothair; FAS), taking on another 1,700 staff members. Essentially, this reform centralized almost all of Ireland’s welfare policy implementation capacity on the national level, thereby relieving local actors of their duty (MacCarthaigh, Reference MacCarthaigh2017).

Ireland’s pension regulator, the PA, is an independent agency set up under the Pensions Act 1990. Its mandate encompasses the regulation as well as supervisors of the operation of occupational pension schemes, personal retirement savings accounts (PRSAs), and trust Retirement Annuity Contracts (RACs). Overall, the PA regulates more than 75,000 occupational pension funds, which collectively have nearly half a million active members (Devine et al., Reference Devine, Mulleady and Nevin2021). This significant responsibility means that Ireland hosts over 90 percent of all pension funds throughout the Euro area, highlighting the extensive fragmentation of Ireland’s occupational pension system compared to other member states, some of which manage as few as eight pension funds in total.

The agency’s core mandate is the protection of the interests of pension scheme members and beneficiaries. In addition, the agency also ensures Pension Funds’ compliance with the relevant legislation and codes of practice. Lastly, the organization also promotes awareness and fosters understanding of the Irish pension scheme by reaching out to the public. More precisely, the agency’s task includes the registration of pension schemes and their trustees and monitoring compliance with registration requirements. Tasks taken very seriously by members of the PA are inspections as well as investigations into pension schemes and their trustees in order to ensure compliance with the relevant legislation and codes of practice (IRE05). The provision of guidance and information to pension scheme member trustees and employers on their rights and obligations under pensions law constitutes another aspect of the agency’s portfolio. Lastly, in its role as regulator, the PA also is responsible for the approval of PRSAs and RACs and the supervision of their operation to ensure that they are being managed in the best interests of their members.

7.2.3 Puzzling Variation of Policy Triage

In the following section, we delve deeper into the varying levels of policy triage prevalent in the Irish implementation landscape (for an overview, see Table 7.1). First, we start with a comparison of the EPA and the PA. Both walk on the bright side of (administrative) life as attested by their very low levels of triage activity. Centrally, we observe that both agencies have a high degree of immunity toward being overloaded while at the same time being able to compensate for additional tasks quite well.

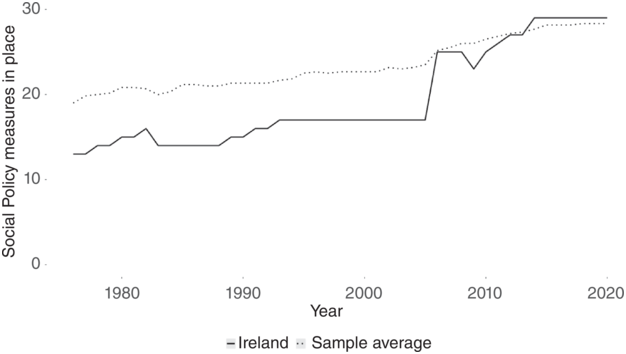

| Organization | Sector | Triage level |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) | Environment | Low |

| City and County Councils | Environment | Medium |

| National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) | Environment | High |

| Pensions Authority (PA) | Social | Low |

| Department of Social Protection (DSP) | Social | Medium |

Transitioning to a more shadowed perspective, the DSP finds itself navigating through murkier waters, facing moderate levels of triage prompted by its increased susceptibility to overload and a comparatively muted ability to buffer these pressures. Having a somewhat similar status but further into the shadows lies the NPWS. Positioned on the darker side of the spectrum, the NPWS is ensnared in frequent policy triage, burdened by its significant vulnerability to workload pressures and a conspicuously scant ability to muster compensatory resources.

Lastly, we turn to the local level at the far end of the rainbow to where blame can easily be shifted. We show that mobilizing resources is in fact limited as the central level essentially rules over the pot of gold with an iron fist. At the same time, compensating for overload is rather limited due to low levels of policy ownership and a weak organizational esprit de corps.

7.3 A Look on the Bright Side of (Administrative) Life: The Environmental Protection Agency and the Pensions Authority

Out of the implementing organizations scrutinized in Ireland, the independent agencies located at the central level – EPA and PA – display the least signs of policy triage. Both organizations face a comparatively low risk of being overburdened while at the same time having a powerful arsenal of mechanisms in place that can compensate for potential overload. Initially, this observation might come as a surprise as the literature generally suggests that formulators are less lenient on independent organizations (T. Bach et al., Reference Bach, Van Thiel, Hammerschmid and Steiner2017; Moynihan, Reference Moynihan2012). In fact, the case of the English Environment Agency described in Chapter 6 shows that independent organizations can easily be used to unload policy growth. In theory, PA and EPA thus should serve as an ideal target for uncompensated accumulation due to limited accountability on the formulating level and a high level of organizational autonomy. Consequently, we would expect Irish independent agencies to be more affected by overload than incorporated organizations such as the DSP or the NPWS.

Empirically, however, we will show in the following section that quite the opposite is the case. The status of the independent agency allows the organizations to interact with the formulators at eye level compared to the other organizations whose relationships are structured more hierarchically (McGauran et al., Reference McGauran, Verhoest and Humphreys2005). Both PA and EPA are routinely consulted about prospective policies, for example, which culminates in a “fairly well marked out ability to influence and to design and to develop [pension] policy” (IRE05). When it comes to the causal mechanisms subsumed under the header of overload vulnerability – blame-shifting potential and the ability to mobilize resources externally – both organizations operate under rather favorable conditions due to their independent status.

7.3.1 Keep the Good Times Rolling: Low Levels of Policy Triage at the EPA and PA

Despite being confronted with an “increasing level of regulations and responsibilities” (IRE01), the EPA shows few signs of overload-induced triage. In other organizations, such a development of growing burden load might be conceived negatively, whereas EPA staffers generally perceive it as validation of previous efforts: “It’s really positive that as an organization, we are increasingly being given more tasks. It’s a reflection of you’re doing existing jobs good” (IRE03). This notion already hints more broadly at the general mindset prevalent among EPA staff members and one of the reasons for the organization’s distinct ability to compensate for overload. Interviewees acknowledged that when tasks are added to the organizational workload, certain efforts are scaled back or outsourced. Yet, this usually applies to low-risk tasks such as community outreach or sample collection rather than statutory tasks, as the EPA is driven by a risk-based approach toward enforcement (IRE02; EPA, 2019). This becomes apparent when dealing with new policies allocated to the organization’s implementation load. Essentially, the prioritization of one task over another, regardless of whether it is old or new, is benchmarked against the environmental risk involved in doing so: “If we get a new important piece of work, we will look at what we do. And if that new work is more important than the existing work, we will reallocate. So we will move resources, if needs be to deal with that new important area” (IRE01).

The main reason for the organization to fall behind in certain tasks is not the non-provision of additional capacities but rather the lag between task allocation and burden allocation. In other words, it takes some time before the agency gets what it needs to implement policies. As one interviewee noted, there is usually a lag of two to three years, which can be exhausting and stressful (IRE01). However, even under these circumstances, staff composition and motivation allow the organization to retain most of its implementation duties and, consequently, is forced to triage only rarely (IRE03). All interviewees noted that overload is generally well contained; therefore, there are little to no implementation deficits, let alone failures, beyond the fact that some actors occasionally have to wait longer for permits (IRE02; IRE04; IRE06).

Moreover, when additional tasks are added to the organizational workload, “there’s always an excitement and an energy around building new systems to respond […] and they [the staff] do embrace the challenge” (IRE02). Low levels of policy triage within the EPA have also been attested by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). In a recent review, the agency was described as meeting its objectives without resorting to major triage decisions during the implementation process (OECD, 2020b: 14). In summary, the EPA is coping quite well despite legislation having “exponentially increased” (IRE03).

Much like the EPA, the PA relies on policy triage only infrequently and instances of triage are of low severity. Nonetheless, instances of overburdening within the organization can occur, particularly when faced with the introduction of substantial new legislation. Interviewees highlighted two significant events that recently contributed to increased workloads. Firstly, the implementation of the EU’s IORP II Directive in 2019 resulted in a notable surge in tasks (IRE09). This directive prescribed a major overhaul, modernizing the operational standards for institutions for occupational retirement provision (IORP), such as pension funds. It introduced several key changes, including new regulations for cross-border operations and the transfer of pension schemes between member states, a standardized pension benefit statement, alongside new investment rules and enhanced requirements for information access. Although these measures are directly aimed at occupational pension providers, the PA bears the responsibility for overseeing and ensuring compliance with these new mandates.

The directive also brought about modifications to the supervisory functions of the PA, transitioning the organization from a reactive, ex post regulatory stance to a proactive, ex ante supervision model. This shift mandates the agency to preemptively identify potential violations of the Pensions Act, rather than addressing them post occurrence. Although these alterations did not significantly expand the number of new policies within the Irish social policy portfolio, they necessitated substantial adjustments to the organization’s operational procedures. As one interviewee noted, “instead of seeing what’s gone wrong, I’ll have to anticipate what might go wrong. So there’s a very, very steep curve. […] now we have to get involved with the trustees of schemes to look at what are the future risks?” (IRE05). This shift to a forward-looking regulatory approach has been described as “the biggest change in pensions regulation for a generation” (IRE05), a development that affected Ireland more than other countries, as much of the pension system is organized via IORPs. As one interviewee noted, “we have more of them [IORPs] than anybody else does in Europe” (IRE08; see also Devine et al., Reference Devine, Mulleady and Nevin2021).

In addition to the accumulation of workload caused by the EU, Ireland is simultaneously embarking on comprehensive reforms of its entire pension system, aiming to streamline the existing framework. The goal is to simplify existing legislation as the current “system wasn’t necessarily designed from pensions legislation up, it kind of came from tax legislation” (IRE08). To this end, an interdepartmental group, chaired by the Department of Finance and involving the PA, Revenue commissioners, and the DSP was established. When discussing the future impact of these reforms compared to the workload from EU directives, an interviewee highlighted the significant organizational shift required by the EU’s IORP II directive. However, they also emphasized the critical importance of the national reform process, particularly from a policy standpoint, as it entails a significant overhaul of the countries’ key pension legislation (IRE08). This dual focus illustrates the complex balancing act faced by Ireland’s pension regulators, navigating between EU mandates, ambitious national reform objectives, and its core mandate.

Overall, it became apparent in all the interviews that those two changes were the most extensive the organization ever went through, being described as “generational” (IRE05). At the same time, however, staffers emphasized that despite those massive increases in workload, the organization is still very much concerned not to lose track of its core mandate:

With that European directive it had to be all hands on deck. That’s what it had to be. You have to decide then how much resource you’re going to give to that; and then what are the tasks that absolutely need to keep going no matter what? So obviously, our primary role as regulators [is] to look after the members’ interests, we need to make sure that money isn’t being stolen from pension funds, that people are being given what they’re entitled to be given. That’s the most important thing.

Regarding the frequency of triage behavior and its escalation due to the workload increase from IORP II and national reforms, an interviewee observed that such practices are infrequent, typically occurring at the unit level rather than organization wide. “It’s not often. That’s more likely to be done at a unit level generally. It’s only when we’re under extreme pressure that it’s done at an organizational level,” the interviewee pointed out (IRE08). This response suggests that while policy triage does happen occasionally, it is reserved for periods of intense pressure and is not a standard procedure across the organization. At the same time, if triage behavior occurs, it is of low severity, as the organizations so far showed no instances of neglecting any of its core tasks since its creation in 1990.

7.3.2 Dancing in the Moonlight: Abundant Capacities and Negligible Overload in Independent Agencies

In the following sections, we turn to analyze the causal mechanisms we theorized earlier as mitigating overload within the context of the two independent agencies. Although both organizations demonstrate a low susceptibility to overload and possess significant compensatory capacity, our empirical investigation reveals nuanced variations in the determining factors.

Formalized Relationships Limit Blame-Shifting to Independent Agencies

Firstly, the potential for blame-shifting is limited when the relationship between agency and policy formulator is structured within a stringent formal framework (de Ruiter, Reference de Ruiter2019; Zink et al., Reference Zink, Knill and Steinebach2024). In Ireland, this arrangement is formalized annually through what is known as a performance delivery agreement. Such documents outline the specific outcomes and tasks the agency must achieve within a set timeframe (IRE02). For instance, the EPA’s agreement might specify precise targets for inspections, setting clear expectations at the start of the year that are later benchmarked against the actual number of site visits conducted. In addition, the principles of the relationship between state bodies on the one hand and the Oireachtas (parliament), minister, and parent department are formalized via the Code of Practice for the Governance of State Bodies more generally (Department of Public Expenditure and Reform, 2016; IRE07).

As we have theorized earlier, the institutional arrangements governing the implementation process significantly shape the potential for formulators to shift blame toward implementers (see also Bache et al., Reference Bache, Bartle, Flinders and Marsden2015). In Ireland, the formalization of performance expectations through individual performance agreements and the Code of Practice serves a dual purpose: On one hand, it instills a level of accountability on both sides, ensuring that there is a clear understanding between agencies and formulators on any objectives that reach beyond the statutory duties as well as the level of resources and support formulators are to provide (IRE07). On the other hand, it equips agencies with a mechanism to shield themselves from unjustified blame (Mccarthy & Yearley, Reference Mccarthy and Yearley1995). By having predefined objectives and metrics for success, agencies can objectively demonstrate their achievements and counter any unwarranted criticisms regarding their performance (IRE02). This system of formal agreements thus not only enhances transparency and accountability within the regulatory framework but also reinforces the autonomy of these agencies while limiting policymakers’ potential to transfer blame.

One key difference between the PA and the EPA, however, lies in the scope and visibility of their mandates, which inherently should influence their vulnerability to blame-shifting dynamics (Hinterleitner, Reference Hinterleitner2020). The PA operates with a narrowly focused, highly technical mandate centered on pension regulation. This specialization places the pension regulators deep within the “engine room” of social policy implementation, conducting their work largely away from the limelight of public scrutiny (IRE05). Contrastingly, the EPA’s engagement with environmental policy encompasses a broader spectrum, making it more susceptible to public and political dynamics. Its responsibilities cover a vast range of environmental issues, from pollution control to the safeguarding of natural resources, thrusting it into a prominent position among government agencies (IRE04). The broad and impactful nature of environmental issues means that the EPA frequently finds itself at the intersection of public concerns, policy debates, and industry interests (IRE01). When environmental crises or controversies arise, the agency’s prominent standing and broad mandate offer a larger surface for political and public blame, unlike the PA, whose technical and focused role shields it somewhat from similar dynamics (Bache et al., Reference Bache, Bartle, Flinders and Marsden2015; Hinterleitner, Reference Hinterleitner2018). This distinction underscores why, in theory, the EPA should be more vulnerable to blame-shifting compared to the PA, given its central role in addressing highly visible and often politically charged issues. However, empirically, it should be noted that we have not observed any severe occurrences of blame-shifting in either case – which might also be a consequence of the agencies’ strong voice in mobilizing external resources to which we will now turn.

Political Influence and a Strong Voice Help to Mobilize External Resources

The PA and the EPA are usually able to mobilize additional resources when additional tasks are added to their workload, as both implementers share high levels of political influence as well as a strong voice. Centrally, the relationships between the agencies and their respective parent departments are coined by trust and respect (IRE03; IRE06). Staff working on the formulating and implementing sides tend to know each other on a personal level. As one representative of the PA put it, “you can walk around Central Dublin and bump into the people you need to talk to over coffee fairly easily” (IRE05). This access to policy formulators is echoed by an EPA member, who pointed out the advantage of personal connections: “it is a big help if you can actually connect with the person [in the department]. It’s easier to pick up the phone for someone you know” (IRE04; Rees et al., Reference Rees, Quinn and Connaughton2013). Overall, the EPA’s parent department is rather approachable regarding additional resources: “They’ve generally been relatively supportive about some of the arguments that we’ve put forward for some extra staff, […] more funding to use a consultant to get you over a short-term issue” (IRE03; IRE02).

In a similar vein, the PA’s principals actively rely on the agency to come forward when it requires additional resources: “our parent department would expect us to guide them on resources that we need to meet additional requirements […] because we’re the ones to know what it’s going to take to do it” (IRE08). This sentiment was echoed across the organization: “We tend to get a good audience from central government when we’re looking for additional resources” (IRE05). In addition, the organization rakes in quite a large part of its operational budget on its own: “the fees that we charge regulated entities essentially pay for our operation” (IRE05). Following recent allocation of additional tasks, the PA announced in their annual report that “the more detailed supervision mandated by the IORP II Directive and other obligations for data collection will increase the work needed and therefore […] an increase in Authority fees for schemes in 2021 will be unavoidable” (Pensions Authority, 2019: 2), highlighting their ability to mobilize resources independently.

Despite the overall positive framework for resource mobilization, interviewees from the EPA acknowledged that securing additional staff has become more challenging in the wake of the austerity measures introduced after the financial crisis in 2008 (IRE02; IRE06). This change reflects the broader constraints faced by Irish public administrations in times of fiscal tightening. Still, both organizations cater to policies that currently enjoy a high priority on the government’s agenda and thus receive significant political attention. For one, several EU infringement cases against Ireland have led to an increase in investment in the EPA’s administrative resources, a development that has prevailed since the Green Party became part of the government (IRE03; Laffan & O’Mahony, Reference Laffan and O’Mahony2008). Similarly, the delayed transposition of the IORP II Directive into Irish law, coupled with the subsequent pressure for rapid implementation, led to the PA receiving approval for additional staffing in late 2019. Thus, when considering the broader administrative landscape in Ireland, both the EPA and the PA are relatively well-positioned. Compared to implementers such as the NPWS or local authorities, the independent agencies are in a “comfort zone” regarding staffing and budgeting.

Two Organizations Committed to Overcoming Resource Constraints

The organizational cultures of both the EPA and the PA are marked by a strong sense of policy ownership among staff and a robust esprit de corps. These attributes are critical to the agencies’ operational ethos, driving efficiency, and effectiveness as integral components of their internal operations. This culture is operationalized through strategic resource management, such as proactive workforce planning where unit heads regularly assess and document their projected needs, ensuring that organizational resources are optimally allocated (IRE03).

Agility and flexibility are cornerstone principles in the human resource management strategies of both agencies. The EPA, for example, emphasizes the importance of adaptability among its staff, with expectations clearly set that roles can and will change in response to shifting priorities (IRE02). This dynamism is supported by a commitment to staff development. The organization allocates 3 to 4 percent of the annual budget to training programs. Training serves dual purposes within the agency. First, it addresses the professional development needs of scientists as they transition into leadership roles, recognizing that advanced management skills are essential for such positions. “A lot of our senior management people might have all come from scientific backgrounds. But you’ll notice if you look across all the senior management people in the agency, they’ve all done MBAs” (IRE02). Additionally, the EPA views training as a crucial strategy for staff retention, offering personal development opportunities to employees even when promotions are not possible. This approach is aimed at rewarding high-performing individuals by enabling them to develop new skills and competencies, thereby fostering a sense of personal growth. Within the EPA, this is seen as the primary strategy to “reward high functioning people as you cannot promote everyone. [But you can] allow them to develop skills and competencies. So it’s a very successful way – through Maslow’s theory [of motivation] – to maintain cohesion and commitment” (IRE02; see also OECD, 2020b).

Similarly, the PA practices internal mobility, allowing staff to temporarily shift roles within the organization. This mobility aids in broadening their understanding of the agency’s diverse functions and creates a supportive, interdependent work environment where resources can be shared as needed, ensuring resilience against potential overload (IRE05). Knowledge transfer is actively encouraged, enhancing the collective intelligence of the workforce across different professional domains and seniority levels (IRE08).

Both the EPA and the PA are characterized by a strong sense of unity and dedication toward achieving their respective policy objectives, underpinned by a robust esprit de corps among staff. The EPA is particularly noted for its leadership’s ability to foster a shared vision, creating an environment where staff feel connected to the agency’s broader goals (IRE26). This sense of purpose is further reinforced by the high level of expertise within the team, with individuals drawn to the challenge of collaboratively pushing forward new policies (IRE02). Ingrained in the organization’s DNA is “a sense of ownership over [its] objectives and policy goals” (IRE01), indicating a deep-rooted commitment to environmental stewardship among its staff.

The PA, meanwhile, benefits from its relatively small size and the close-knit nature of its team. The agency’s central location in Dublin facilitates regular interaction among staff, fostering a collegial atmosphere. The PA’s stable staff turnover rates contribute to a continuity of knowledge and experience within the organization, enhancing its effectiveness (IRE07). Communication within the PA is structured to highlight the agency’s impacts and successes, with positive outcomes regularly shared across the organization. This approach is aimed at reinforcing staff morale and demonstrating the tangible differences made by the PA’s efforts, thereby motivating the team by showing how their work helps “improve outcomes for members” (IRE05). In both agencies, these cultural attributes play a crucial role in not only shaping their internal dynamics but also in driving their success in advancing policy objectives and coping with potential overload.

In conclusion, the combination of their independent status and the strength of their organizational culture plays a crucial role in enabling both agencies to sidestep potential implementation failures. The formalized accountability mechanisms between the agencies and their overseeing bodies effectively delineate responsibilities, thereby minimizing the potential for blame-shifting from policymakers. This clarity in accountability, combined with the high-priority nature of the policies they implement, endows the two organizations with considerable political influence and a compelling voice in policymaking, which in turn enables them to easily mobilize resources externally.

The EPA and the PA both place a strong emphasis on cultivating a cohesive organizational culture. They actively promote an esprit de corps among their staff and encourage a deep-seated sense of ownership and commitment toward their organizational objectives. This internal dynamic not only strengthens team unity and motivation but also aligns individual efforts with the agencies’ broader goals.

In sum, low levels of policy triage in these agencies, therefore, is not only a product of their limited exposure to political blame-shifting and opportunities for mobilizing external resources but also a result of their deliberate efforts to maintain a motivated and closely knit workforce dedicated to advancing their respective policy agendas and avoiding implementation deficits.

7.4 Out of the Blue and Into the Black: The DSP and the NPWS

Section 7.3 suggested that one of the key factors explaining why the PA and EPA both engage in comparatively little policy triage chiefly is linked to their status of independent agencies on the central level. However, this contrasts sharply with the DSP’s implementing arm and the NPWS, despite their somewhat similar integration within their respective government departments. Their experiences with policy triage diverge significantly from the other organizations on the central level but also from each other.

For the DSP, triage, while present, is relatively controlled. This moderation can be attributed to the DSP’s limited vulnerability to overload, coupled with a degree of compensatory competence that allows the organization to manage and mitigate potential pressures. The DSP is thus able to navigate the demands of policy implementation without resorting extensively to triage, maintaining a level of operational stability that aligns more closely with the experiences of the PA and EPA. In stark contrast, the NPWS finds itself grappling with significant challenges that exacerbate its vulnerability to policy overload and strain its compensatory capacity. This unfortunate confluence of factors renders policy triage not just a temporary strategy but cements it as a fundamental aspect of the NPWS’s operational approach. The organization’s struggle across key areas – blame avoidance, mobilizing resources externally, and compensating for overload – highlights a profound operational divergence from both implementers on the central and local level. In the following sections, we delve deeper into the variation of causal mechanism leading to such marked differences in the outcome.

7.4.1 Policy Triage at the DSP and the NPWS: From Medium to High

The DSP, which caters to most Irish social policies, shows signs of triage when confronted with sudden, punctuated increases of workload. In such situations, certain services are being delayed and clients must wait longer for decisions (IRE11). During the interview period, the DSP was undergoing a significant transformation with the introduction of a new operational model that consolidated its regional structure from seven independently staffed regions into just four. This restructuring placed considerable strain on the organization, disrupting its established ways of working due to the “pace of change, implementing change, working with new teams” (IRE10). These changes occasionally resulted in service delays and longer wait times for client decisions even pre-pandemic as staff members focused on the implementation of the reforms.

The COVID-19 pandemic further exacerbated pressures on the DSP, as it did on social protection systems worldwide. The pandemic’s sudden onset required the organization to swiftly implement emergency relief measures, including the Pandemic Unemployment Payment (PUP), which was rolled out with remarkable speed: “We had a weekend to sort out the PUP payments. […] Then we worked weekends, we worked bank holiday” (IRE10). The dramatic increase in workload triggered by the introduction of new policies during the COVID-19 pandemic, while simultaneously managing ongoing responsibilities, was starkly illustrated by an interviewee’s experience:

I went from dealing with 100 customers a day to 700 overnight when that pandemic hit. So, you totally had to change the whole operations. But you’re still dealing with the same amount of work. We still had the same amount of people on the live register. […] We still had to get the payments out. We still had to provide all the information. Basically all the systems we had in place still had to stay, but we had to adapt to this new crisis and bring in a new system. We couldn’t plan for it. We had no timeframe. Normally you’d get a timeframe to implement something.

In addition to the short timeframe for implementation and the massive workload, the integration of the PUP into the DSP’s operations also presented significant challenges, primarily due to a fundamental misalignment with the department’s existing policy and operational framework. The nature of the PUP policy, characterized by lump sum payments, starkly contrasted with the DSP’s standard approach to benefits, which typically involves detailed client assessments and the provision of customized support measures. One staff member responsible for the implementation of the policy suggested that the PUP might have been more appropriately managed by the revenue commissioners, given its deviation from the DSP’s conventional processes (IRE11).

Setting aside the unique circumstances brought on by the pandemic, the DSP experiences a form of policy triage that occurs on a seasonal basis. This is particularly evident with programs such as the Back to Education Program, an unemployment measure that sees a significant influx of applications from June to November. During this peak period, the DSP resorts to a mode of triage that could be described as organizational horse trading to manage the workload effectively. An interviewee explained this process: “What I do is I rob Peter to pay Paul […] when we get over a certain level of applications, I will take staff from other areas to shore up that particular team […] It’s not a great way of doing it. But you know, you kind of use what you have” (IRE10). Doing so however, consequently leads to implementation backlog in other areas.

Lastly, a feature of policy accumulation (Adam et al., Reference Adam, Hurka, Knill and Steinebach2019) or policy layering (Mettler, Reference Mettler2016) can also be observed for the DSP’s implementation portfolio. Several policies that are outdated or are no longer essential to the organization’s core mission stay in place due to the vote-seeking behavior of the formulating level: “Politicians will not want to decrease payments; they will not want to stop a certain thing because that means they won’t be voted for” (IRE11). Although none of the interviewees explicitly identified this tendency as a cause driving policy triage, it undoubtedly contributes additional pressures to the organization.

In summary, the DSP, due to its role as central implementer of social policy in Ireland, finds itself navigating a complex and extensive policy portfolio, marked by occasional recourse to triage strategies. Compared to independent agencies at the central level, the DSP employs triage more frequently, though it does reach neither the frequency nor the severity observed within the NPWS. Triage within the DSP tends to be episodic, emerging primarily during extraordinary increases of workload such as the introduction of new policies brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic, extensive reforms, or during seasonal peaks in demand for certain programs.

The most common consequence of triage within the DSP is extended waiting times for client decisions. This indicates that while the organization does face periods of strain, the impact on service delivery, though noticeable, does not generally result in implementation failures but rather in delays (IRE17). In response to workload surges, the DSP’s strategy focuses on prioritizing tasks that are central to its mission, ensuring that the most critical functions are maintained without losing sight of the needs of their clientele. In regular times, however, “the department as a whole usually works and stuff is done. So everything is implemented” (IRE17).

In conclusion, the variation in policy triage within the Irish social sector is less pronounced compared to that observed among environmental policy implementers. The PA closely parallels the situation of the EPA, exhibiting few to no noticeable instances of organizational policy triage. On the other hand, the DSP shows a pattern of more regular triage occurrences, though both the severity and frequency are relatively limited.

The NPWS, in contrast, is an outlier compared to the other three central level agencies (EPA, PA, and DSP); it is the only organization scrutinized that shows critical levels of policy triage (IRE28). The organization is forced to triage severely and frequently due to “unplanned visitation of additional workloads without resources” (Kearney, Reference Kearney2022: 12) – uncompensated policy accumulation, in other words – which resulted in failure to implement its existing tasks and obligations. At the same time – and because of the financial crisis – the organization had to endure huge cuts to both staff and budget. Between 2008 and 2011, the NPWS’s budget was decreased by 70 percent. The level of budget allocation introduced in the wake of the financial crisis effectively persisted until 2020, essentially rendering the agency unable to cater to large parts of its implementation tasks due to a lack of resources. Only as recent as 2021–2022 did funding reapproach the precrisis level of 2008 while workload grew well beyond the levels of 2008 in the meantime. An internal analysis in 2021 concluded that the organization urgently needed an additional 87 staff members, an increase of 21 percent from its current number of 400 (Kearney, Reference Kearney2022: 16). Overall, the organization has been under-resourced for years, which has resulted in staff being rather pessimistic when asked about the implementation process: “There’s so much to do. There’s so much to do and we’re all left to do a little bit” (IRE28).

On par with our interview findings, a recent review by ecologist Jane Stout and former EPA director Micheál Ó Cinnéide concluded that the NPWS “cannot meet current obligations, let alone plan for and respond to future challenges and legislation” (Stout & Ó Cinnéide, Reference Stout and Ó Cinnéide2021: i). In other words, the organization is not even able to triage crisis preparedness in favor of current tasks. One staffer noted that ensuring diligent implementation on the ground is “problematic” as the organization lacks the staff members required to perform those tasks (IRE28).

As a result of those implementation gaps, Ireland potentially faces an escalation of EU infringement cases for its failure to meet the obligations put forward in the Nature Directives – policies the NPWS centrally oversees (Kearney, Reference Kearney2022: 12). In particular, the Wildlife Crime Unit is described as nonfunctional, rendering Ireland unable to prosecute offenses in this area. Regarding concrete implementation measures, monitoring, licensing, and the provision of scientific advice, tasks are severely neglected (Kearney, Reference Kearney2022; Stout & Ó Cinnéide, Reference Stout and Ó Cinnéide2021). An example that has been featured in the media recently is the organization’s inability to adequately enforce legislation protecting Ireland’s peatlands despite being hailed as a “low hanging fruit of emission reductions” (Sargent, Reference Sargent2022). As a result, about 500,000 tons of peat were being exported without permission in 2021, according to a government estimate.Footnote 1

At the same time, the Licensing, Legislation and Statutory Consultation Directorate “has been subjected to a tsunami of work arising from large volume of applications for advice, assessment and input from across other public bodies in relation to ecology” (Kearney, Reference Kearney2022: 33), accumulating massive backlogs in this area. Similarly, the NPWS severely lags behind the development and modernization of legislation regarding the Wildlife Acts and the Birds and Habitats Regulations as existing capacities are already absorbed in day-to-day implementation (Stout & Ó Cinnéide, Reference Stout and Ó Cinnéide2021). Yet, doing so would actually decrease complexity and, consequently, workload, as interviewees disclosed in a report by the Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage:

The 2011 Birds & Habitats Regulations are in need of overview and updating – they are very convoluted, complex regulations and, in many cases, they don’t actually properly transpose the Nature directives – it’s very difficult to understand and unduly complex, it was done in a hurry. We need to review and revise the primary legislation i.e. Wildlife Act and European Communities (Birds and Natural Habitats) Regulations. Presently, the Act and Regulations are not fit for purpose and pose serious challenges to staff in relation to the protection of nature conservation e.g. there exists serious limitations in relation to the protection of biodiversity in general, wildlife licensing and consent procedures for works within designated sites.

Thus, in summary, the NPWS is affected immensely by overburdening not only in a few selected units or in certain instances but also constantly, across the entire organization. The central cause forcing the organization to engage regularly in severe policy triage measures has been identified by our interviews and multiple government reports as uncompensated allocation of evermore complex and at times conflicting tasks. In line with our theoretical argument, the case of the NPWS thus shows how policy accumulation that is not accompanied by resource increases significantly impacts the implementation performance of an entire policy (sub-)sector.

The Irish environmental sector consequently presents compelling evidence of policy triage patterns, illustrating a wide spectrum of responses within the sector itself. On one end, the EPA exhibits minimal, if any, signs of policy triage, indicating an equilibrium between resources and tasks. On the other, the NPWS is a clear example of an organization deeply entrenched in policy triage due to overburdening. Between these two extremes lie the City and County administrations, which demonstrate elevated levels of triage activity, yet not nearly as critical as the NPWS. Interestingly, the variation in policy triage is not solely a result of being situated at different governmental levels. The case of the NPWS starkly demonstrates that centralization does not provide an organization with immunity against the risk of overburdening.

7.4.2 Out of the Spotlights: Two Types of Struggle to Deal with Overload

Although the DSP and the NPWS both share a similar status, being incorporated into a government department, they deviate significantly when it comes to overload vulnerability and compensation. In the following sections, we dissect how different combinations of the causal mechanisms we theorized earlier yield different triage outcomes for the two organizations.

Blame-Shifting: Two Contrasting Scenarios

The dynamic between blame-shifting attempts and task assignment within independent agencies operates on a distinct logic compared to the DSP. In the cases of the EPA and the PA, the agencies are shielded from blame-shifting through clear delineation of tasks and responsibilities. The DSP, in contrast, integrates policy formulation and implementation within the same organization, providing safeguards against excessive blame attribution. In other words, the formulating level thus is directly accountable for potential implementation delays or even failure.

However, a significant portion of the organization’s budget is managed by the Department of Expenditure and Reform and the Prime Minister’s Office, alongside funds from social security system contributions (Hardiman & MacCarthaigh, Reference Hardiman and MacCarthaigh2017). This arrangement places overarching financial control outside the DSP, specifically within the realms of the Department of Public Expenditure and Reform and the Department of Finance, which exert stringent oversight over budget allocations across the Irish public sector. Thus, while the DSP itself must come up with certain parts of the administrative budget for IT infrastructure, for example, overall budgetary control is not located with the actors that actually formulate social policy (IRE11).

The challenges faced by the DSP pale in comparison to the severe difficulties encountered by the NPWS. Unlike the DSP, where the formulating level holds a degree of accountability, albeit in a suboptimal framework, the NPWS has languished without robust support or adequate resource allocation from its formulating level. This neglect is partly due to the absence of effective accountability mechanisms, allowing the formulating level to evade responsibility while leaving the NPWS exposed to operational and resource challenges. The organization’s political unfavorability has led to a reluctance to support the NPWS, rendering it an organizational “foster child” the formulators did not “want to engage with” (IRE28). As a result, the organization frequently shuffled between parent departments – a phenomenon MacCarthaigh and colleagues term “slicing and dicing” of departmental portfolios (MacCarthaigh et al., Reference MacCarthaigh, Biggins and Hardiman2023: 19). Since its establishment in 1991, the NPWS has changed departments six times, which contributed to a pervasive sense of instability within the organization. Centrally, it facilitated a situation where policymakers can conveniently sidestep accountability, leading to significant issues as highlighted by a government report: “lack of ownership, lack of understanding of the organization’s role and a lack of desire to take on the challenges faced by the organization [by the formulating level]” (Department of Housing, 2021: 9).

Such systemic neglect is starkly illustrated by a policy introduced to compensate turf-cutting, where the NPWS was burdened with financial responsibilities without the provision of necessary funds:

When the derogation on turf-cutting ended, Minister Deenihan decided we were going to compensate everybody, that was a government decision, it was agreed at government, but they didn’t give us any money. So, the money that was our Program funding had to go to the Turf Compensation fund. It’s moved on, we’ve paid over €30 million in compensation for the cessation of Turf cutting and Relocation schemes.

In summary, the NPWS exemplifies a scenario where the mechanisms we theorized as limiting blame-shifting are notably missing. This absence also has a profound effect on the organization’s capacity to mobilize external resources, a topic we will delve into in the following section. Meanwhile, the DSP faces fewer instances of blame-shifting, yet it too grapples with challenges stemming from suboptimal accountability structures.

Mobilizing Resources Externally: Structural Aspects Determine Opportunities

The economic downturn significantly impacted the resources available to public sector organizations in Ireland, with the NPWS experiencing more severe effects than most. The 2008 financial crisis led to a drastic 70 percent cut in the NPWS’s budget, resulting in significant implementation failures. As noted, “the pace went down a lot, because resources were not there. They could not implement the policies” (IRE28). This reduction in capacity was exacerbated by the NPWS’s lack of a unified leadership and visibility, diminishing its ability to effectively advocate for additional resources.

Without a singular director or CEO, the agency is “managed by four principal officers as four distinct Directorates/Sections, each containing four to five units, reporting to the Assistant Secretary General [of the Department]” (Stout & Ó Cinnéide, Reference Stout and Ó Cinnéide2021: 25). This fragmented leadership dilutes the NPWS’s organizational voice, making it challenging to communicate effectively with its principal and other stakeholders. A general absence of external communication has been attested by both an interviewee within the organization and external evaluators, noting that consultation efforts often go unrecognized and non-responded to, with regional managers’ requests and business cases being ignored (IRE22; Kearney, Reference Kearney2022).

Additionally, the NPWS’s internal fragmentation hinders the formulation of a cohesive stance on resource needs, with different units often unaware of their colleagues’ tasks and progress. This lack of communication extends to senior management, where little effective dialogue occurs. At the operational level, the situation is even more dire, with street-level bureaucrats reporting to multiple principals and basic support demands, such as for “a working photocopier, phones, internet access or livery,” going unmet (Kearney, Reference Kearney2022: 17). This systemic fragmentation and communication breakdown severely limits the NPWS’s capacity to advocate for and secure the necessary resources to fulfill its mandate effectively.

While funding for the NPWS has returned to precrisis levels, this improvement was not achieved through the organization’s own efforts at resource mobilization. Instead, it came as a direct consequence of external pressure: Policymakers increased the budget only after several infringement cases were brought against Ireland by the EU (Zink et al., Reference Zink, Knill and Steinebach2024: 15). This scenario highlights the reactive nature of funding restoration, driven by the need to address legal challenges from the EU rather than proactive support or recognition of the NPWS’s resource needs by domestic policymakers.

While the DSP is in a comparatively better position than the NPWS in terms of resources, it still faces significant challenges in mobilizing additional resources, especially when compared to independent agencies at the central level. The DSP’s efforts to expand resources are often hindered by the centralized control over funding and staffing levels, as explained by a DSP interviewee: “Our Department of Reform and Finance are doing the funding of the civil service. And they determine how many staff you can have. Look [additional] staff – can’t get them, it’s just not happening” (IRE10). This situation is exacerbated by a noted lack of recognition “at a higher level, I’d say probably at ministerial level – that we do need extra staff” (IRE10).

The process of filling vacant positions further complicates the DSP’s operational capacity. As positions become vacant due to retirement or internal movement, it “can take up to six or eight months to get an officer [..] replaced” (IRE10). Coupled with the six months required for staff training, this often results in a year-long gap before a case officer is fully replaced. Unless reforms of the hiring and workforce planning are not implemented, this is prone to become a larger problem for the DSP in the future as the age of the average staff member is around fifty and “a lot of people are going to be exiting now in the next 10 years” (IRE10).

One strategy of external resource mobilization directly informed by the difficulties to recruit additional permanent staff is to outsource certain tasks. Work that is technically within the DSP’s purview but considered peripheral to its central functions regularly is transferred to external contractors. This allows DSP caseworkers to concentrate on more critical tasks, such as conducting in-person meetings with clients, deemed “substantive work” (IRE10). However, the DSP’s capacity to outsource is constrained by two factors. Firstly, the extensive involvement of private entities in carrying out core DSP functions risks drawing scrutiny and opposition from trade unions, which may advocate for these tasks to be managed by permanent DSP staff instead. Secondly, the sensitive nature of personal client data introduces stringent limitations on information sharing, even among public bodies. This concern for data privacy and security restricts the extent to which certain tasks can be outsourced, particularly those involving confidential client information (IRE11).

Still, the DSP has experienced some recent improvements in terms of accessing overtime pay and equipment, facilitated by the heightened prioritization of social policies during the COVID-19 crisis. This change reflects a shift in the government’s responsiveness to the DSP’s needs, with one interviewee observing, “now that we’re in a crisis, I’m going to seem to be able to get what I want” (IRE11). The crisis has not only elevated the visibility of the DSP but also its political influence, with increased consultations between the formulating level and frontline DSP staff leading to more informed and responsive policymaking (IRE11).

Varying Commitment Toward Overload Compensation

Lastly, the commitment to compensate for overload is determined by the level of ownership over policies and the respective organizational culture. The DSP exhibits a profound commitment to compensate for workload pressures, a quality deeply embedded in its organizational culture and the sense of ownership its staff hold toward their duties. Across the DSP, there exists a robust esprit de corps and a shared dedication to the mission of assisting clients through challenging times, regardless of the specific policies in question. This dedication is driven by a collective commitment to service and support, as reflected in one interviewee’s assertion that “in social protection, we have to get it right” (IRE11). This ethos was particularly evident during the rapid rollout of the PUP, where the sudden surge in workload was met with a unified, organization-wide response. An interviewee recounted the initial shock and subsequent rallying effort, noting, “there were all these new payments brought in that had to be implemented really quickly. […] Initially, it was quite shocking. But, you know, that’s what you have to do when people are waiting for money to pay bills and feed their kids” (IRE17).

The organizational structure of the DSP proved adaptable in the face of crisis, with high-level management personnel stepping in to assist with ground-level operations, embodying an “all-hands-on-deck” approach (IRE11). This flexibility within the hierarchy facilitated a swift and effective response to the unprecedented demands posed by the pandemic. Moreover, the dedication of line managers and their willingness to extend themselves beyond typical work hours underscore the DSP’s culture of resilience and determination. When faced with the challenge of insufficient time to complete tasks, one interviewee encapsulated this ethos by stating they “just make it happen […] even if it means I have to work 60 hours a week. I’ll do it and get it done” (IRE10).

Thus, in summary, the strong culture of ownership and esprit de corps, coupled with a commitment to go above and beyond to meet client needs, underscores the DSP’s organizational strength in navigating periods of intense demand. Ultimately, the organizational commitment can be seen as the key factor explaining why the organization has not engaged more frequently and severely in triage activity so far.

The NPWS presents a stark contrast to the DSP and other organizations that have successfully cultivated a strong sense of policy ownership and esprit de corps among their staff. Despite individual members possessing a deep commitment to the goals of nature conservation and preservation, the NPWS struggles to unify these personal commitments into a collective organizational identity (IRE28; Department of Housing, 2021). This failure stems from several organizational shortcomings.

Firstly, communication within the NPWS is notably deficient, leading to feelings of disconnection and powerlessness among staff members. A survey highlighted that individuals and teams within the organization often feel isolated due to inadequate communication across the organization:

Communications are poor on many levels: Not enough internal communication or sharing of work plans and priorities and this applies within small units, and at every level, right up to organization-wide. There simply is no culture of communicating and working together. We have no newsletter, no conference, no method whatsoever of communicating across NPWS.

The geographical dispersion of the NPWS, with thirty-two office locations spread across nineteen of Ireland’s twenty-six counties, further exacerbates this sense of disconnection, complicating efforts to foster a unified organizational culture (Department of Housing, 2021: 8). Secondly, the lack of well-defined, dependable processes within the NPWS has left its staff without a uniform framework to direct their efforts. This deficiency is a direct consequence of the organization’s fragmented structure, which has led to unclear roles and responsibilities among its members: “staff cannot be provided a wide ranging job description and no prioritization of tasks to cherry pick or allow circumstance dictate what the job becomes” (Department of Housing, 2021: 10). Such ambiguity fosters a work culture characterized by the avoidance of accountability, succinctly captured by the sentiment, “It’s not my area – so it has to be yours attitude” (Department of Housing, 2021: 34). Consequently, there often is no clear path guiding the implementation of various tasks, which is compounded by the absence of senior leadership to provide direction and support (IRE28). Lastly, the organization’s approach to human resource management contributes to internal dissatisfaction. The recruitment of staff members who are often overqualified for their positions, combined with limited prospects for career advancement and the absence of a dedicated human resources department for support, results in widespread frustration among the workforce (Department of Housing, 2021).

These factors collectively impede the NPWS’s ability to foster a strong esprit de corps or to establish a sense of policy ownership that transcends individual commitments. The organizational challenges facing the NPWS undermine its capacity to effectively marshal its resources and personnel toward its conservation mission, highlighting the critical importance of robust communication, clear organizational structures, strategic leadership, and effective human resource management in building a cohesive and motivated workforce.

To conclude, the NPWS and the DSP present contrasting cases despite sharing a similar formal status within the government structure, the nature of their relationships with their respective principals – and consequently their operational dynamics – differs markedly. For the NPWS, the implementation landscape allows for greater latitude in blame-shifting from formulators to implementers. This is facilitated by a relatively weak connection with their principals, which, in turn, restricts the NPWS’s ability to mobilize resources externally. Compounded by low levels of policy ownership and a fragmented organizational culture, these factors significantly hinder the NPWS’s efforts to mitigate overload effectively. In contrast, the DSP operates under a different paradigm. Although mobilizing additional resources externally poses challenges, the organization demonstrates a robust commitment to addressing overload, underpinned by a strong sense of policy ownership and a cohesive “esprit de corps” among its staff. This organizational solidarity and dedication to their mission enable the DSP to engage more proactively and effectively in overload mitigation strategies.

7.5 At the Far End of the Rainbow: Local Authorities

As a result of the creation of the EPA, local environmental implementers received significantly less attention. While a large part of their implementation load was transferred to the newly created agency, the local City and County Council retained a number of tasks but were also affected by policy accumulation, particularly related to local implementation of low-risk, low-impact policies. The EPA’s increasingly prominent role cast a cloud on local implementers’ visibility and perceived relevance (IRE16).

7.5.1 Regular Triage on the Local Level