Issues in national politics in 2014

For the past six years, economic crisis has remained a dominant issue, and during 2014 countries continued to struggle with the impact of austerity, unemployment and budget deficits. Europe also faced political tensions on its borders to the south, stemming from the Syrian civil war and the ongoing threat from ISIS, and the emergence of a major new conflict arose closer to home in the Ukraine. Immigration also continued to be a major issue, and contributed to growing support for radical right and EU-sceptic parties in the European Parliamentary elections in May. On the domestic front, political scandals and corruption remained at the fore, and some states experienced strengthened calls for regional independence.

Economy

The economy remained much the same as in 2013, with some countries showing signs of renewed growth, while others, particularly in the eurozone, remained sluggish. This motivated the European Central Bank to introduce new stimulus measures, including a negative interest rate to encourage banks to lend and to ignite its member economies. While the focus was particularly on the struggling economies of Greece and Spain, the German Bundesbank equally showed little sign of optimism, as it halved its forecast for Germany's gross domestic product (GDP) growth in 2015 to 1 per cent. Another major economy – Japan – also struggled to recover, although the Liberal Democratic Party was re-elected in early parliamentary elections, an approval of the Prime Minister's ‘Abenomics’ policies.

On a positive front, some of the European economies that had borne the worst impact of the recession experienced signs of recovery, as Portugal followed Ireland's path of the previous year by graduating from the bail-out mechanism of the International Monetary Fund-European Commission-European Central Bank ‘troika’, and returning to relative fiscal sovereignty. However, the collapse of a major Portuguese bank and the ongoing crisis in Greece demonstrated that these green shoots still had relatively shallow roots. Greece, in particular, continued to dominate front-page headlines as its government struggled to deal with policies of austerity, and to convince the global markets of its ability to manage its own debts.

International crises

The collapse of the domestic government in the Ukraine, the fleeing of its president and the subsequent absorption of the Crimean region by Russia had a considerable impact on European security policies, especially for countries in Central and Eastern Europe. The imposition of sanctions on Russia by the European Union exposed divisions within some of these countries, with some fearing the repercussions on their own economy and security. Finland, which shares a border with Russia, did not support economic sanctions, while some parties in the Baltic states also echoed disapproval. This included Harmony, the main opposition party in Latvia, which lost some domestic support as the result of its ambiguous stance toward Russia. Ambiguity towards Russia was also evident in Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Cyprus (which has a considerable Russian expatriate population). In the countries sharing a border with Ukraine and Russia there was renewed emphasis on security policy, marked by an increase in defence budgets and an increase in the presence of NATO troops. Pressure proved particularly high in Estonia, where evidence suggests that Russian forces crossed the border to kidnap an Estonian officer only days after United States President Barack Obama visited the country to reassure it of NATO's protection. The direct impact of the conflict spread to the west of the European continent with the shooting down of a Malaysian Airlines flight carrying 200 Dutch citizens. This incident had particular resonance in Poland, where the crash in Russia in 2010 of a government plane that killed the Polish president and many other high-ranking officials remained a source of tension between the two countries.

From the south, European governments faced a threat from the emergent Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS), which attracted Islamic radicals from America and Europe and prompted a renewed campaign of air strikes by the Western allies. The issue of Muslim extremism spilled over into high-profile incidents of terrorism in Australia, Belgium and Canada, including an isolated, but jarring shooting incident in the Canadian parliament building.

Related in part to the ongoing crisis in Syria, immigration remained one of the key issues of the year, fueling support for some European Parliament election campaigns in May. In Germany, a new movement of ‘Patriotic Europeans Against the Islamisation of the West’ (PEGIDA) campaigned for more restrictive immigration rules, particularly for Muslims, though the counter-PEGIDA protests attracted larger crowds. The immigration crisis was most keenly felt in the Mediterranean countries of Greece, Malta and Italy as they struggled to deal with the thousands of refugees arriving by boat from North Africa.

Separatism

One of the biggest political events of 2014, or perhaps one of the potentially big stories had it passed, was the referendum on Scottish independence in the United Kingdom. Unlike past defeats on this question, the failure of the referendum did not seem to quell the issue, and support for the Scottish Nationalist Party continued to grow. Although the Westminster government promised more devolution, the effort seemed as likely to whet the appetite of pro-independence Scots as to reduce the demands for independence. Separatists in other countries, in particular Belgium and Spain, watched the outcome of the Scottish vote with keen interest. A referendum in Catalonia received almost twice the level of support for secession as in Scotland, though the unsanctioned nature of the vote meant that those who opposed the separation could express their preference simply by staying home. In Belgium, the New Flemish Alliance entered government as the largest party following federal elections in May, and the country undertook major constitutional reforms to devolve some powers to the Senate and to give some additional autonomy to Brussels and German-speaking regions. The separatist trend was not universal in 2014, as in Canada support for the Bloc Québécois at state assembly elections in Quebec was at its lowest level in over 40 years. Attempts to ameliorate separatism and achieve reunification also continued in Cyprus, but peace negotiations failed to achieve a breakthrough.

Domestic politics

Political scandals, as with any other year it seems, remained a newsworthy issue across PDY countries. Many of these scandals involved corruption. In Ireland, corruption in the police force resulted in the resignation of the Minister for Justice, the Police Commissioner and the Secretary General of the Justice Department. In Luxembourg, the ‘Luxleaks’ scandal eventually resulted in an end to the country's practice of banking secrecy, amidst much arm-twisting from the European Commission. Former prime ministers were arrested in Portugal and Romania, with the latter sentenced to a prison term for bribery and blackmail, along with a raft of other politicians in the country. There were protests against corruption in Hungary after government officials, including the head of the tax regime, were banned from entering the United States. In Slovenia, a former prime minister previously found guilty of corruption re-entered politics, and government ministers were forced to resign in Slovakia following allegations of corrupt activities.

These actions were not confined to Central and Eastern Europe, as a government minister resigned in Spain in a scandal involving regional governments, party treasurers and slush funds, and King Juan Carlos abdicated in the middle of an investigation into corruption in his family. In France, the head of the leading opposition party resigned in a funding scandal while former President Nicolas Sarkozy, who is pondering another run for the office, faced police investigation and France's incumbent President, François Hollande, faced scandal of a more personal sort when details of his affair with a journalist became public. Across the Atlantic, one of the most high-profile incidents of the year involved Toronto's lord mayor, Rob Ford. Seeking re-election, a police investigation into allegations of substance abuse led to his taking a leave of absence to enter a drug rehabilitation clinic and eventually withdrawing from the campaign.

Cultural values also played a noteworthy role in domestic politics in 2014, especially gay marriage. The United States Supreme Court refused to overturn lower court rulings that permitted gay marriage in five additional states, Britain held its first gay weddings and same-sex marriage was legalised in Estonia – the first former Soviet republic to follow this path. Catholic and conservative Malta not only made same-sex marriage legal in all but name, but also gave same-sex couples full adoption rights, which was not the case in some other countries legalising same-sex marriage. In Luxembourg – another country with concerted Christian opposition to such policies – the new government not only implemented same-sex marriage, but also enacted legislation decriminalising abortion and simplifying its legal framework. Efforts by the same government to replace religious teaching in its school system became the source of considerable protest.

The European Parliamentary elections

In May 2014, the eighth direct elections to the European Parliament took place in all 28 Member States, but with little focus on European Union issues and ultimately a further decline in public participation. The most spectacular outcome was the strong performances of a few radical right, anti-immigration and EU-sceptical parties, but such successes were not uniform across the continent and pro-EU parties maintained a clear majority.

Election campaign

As many country reports indicate, the election campaigns in the 28 Member States were, with a few exceptions, dull and sometimes overshadowed by other elections or events. In Lithuania, public attention focused far more closely on the second round of the presidential elections taking place on the same day, and across the Baltic the debate was dominated by the crisis in Ukraine rather than European Union issues. In Denmark and Cyprus and a wide range of other countries, voters focused on domestic scandals. In a few countries, some EU-related issues did dominate campaigns, though as in Portugal and the United Kingdom, these were frequently focused not on EU policy making, but on the more fundamental question of whether to remain in the EU in the first place.

European party groups themselves tried to raise the stakes in the elections by identifying specific candidates for the Presidency of the European Commission. The campaigns in individual countries focused mostly on domestic issues and in general they did not stir up much interest among voters. Turnout dropped for the seventh consecutive election to an all-time low of 42.6 per cent, though the drop from 2009 was a relatively small 0.4 percentage points. Although turnout increased in seven countries, and remained approximately the same in seven others, it showed a clear decrease in 14 of the union's 28 countries – most severely so in Latvia, where turnout went down by 23 percentage points. The lowest turnouts are still found in Central and Eastern Europe: Slovakia leads the list with an astonishingly low 13.1 per cent, followed by the Czech Republic with 18.2 per cent and another six countries from that region below 35 per cent. In fact, all countries in the region except Lithuania (with its simultaneous presidential election) had turnout rates below the EU average, and the average for the postcommunist countries overall dropped by nearly 5 percentage points, far faster than Europe as a whole.

Election results

The most conspicuous outcome of the elections was the strong performances of several EU-sceptical, anti-immigration parties. In both France and the United Kingdom, parties that had been marginalised by the electoral system in their national parliaments emerged with the largest EP delegations. France's Front National (FN) won close to 25 per cent of the votes and 24 seats, almost twice as much as the Left List, which included the incumbent Socialist Party. The anti-EU UK Independence Party (UKIP) narrowly beat both Labour and the Conservatives, winning almost 27 per cent of the votes and 24 seats. In Denmark, the Danish People's Party (DF) won the election with close to 27 per cent of the votes and four of the 13 Danish seats. It should be noted, however, that these three parties, although similar in some respects, all belong to different party groups: the FN did not join in any group in 2014; UKIP paired with Italy's 5 Star Movement in Europe and several smaller parties to sustain the Europe Freedom and Democracy group under the new name ‘Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy’ (EFDD); and DF opted to join Britain's Conservatives, Poland's Law and Justice and the new Alternative for Germany in the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR).

As Table 1 shows, the two groups most sceptical of the EU (i.e., ECR and EFDD) gained ground, as did the parties without formal attachments (i.e., the Non Inscrits) whose total increased by 19 seats to 52. Although diverse, this latter category is weighted toward the far right, including neo-Nazi or fascist parties such as Golden Dawn and Jobbik in Hungary. The Sweden Democrats, the Austrian Freedom Party and Golden Dawn all gained seats compared to the previous elections and, due to the lack of electoral threshold, Germany's extremist National Democratic Party managed to win one seat with only 1 per cent of votes. The growth in support for the far right was not uniform, however, and in several countries EU-critical and/or extremist parties lost support, while some also lost parliamentary representation, such as the Alliance for the Future of Austria, Ataka in Bulgaria, the British National Party, the Greater Romanian Party and the Slovak National Party.

Table 2. Number of parties in cabinet, type of cabinet and gender and average age of cabinet members

Notes: Figures for cabinets measured on 31 December 2014 or, for cabinets ending during 2014, on the cabinet's final day in office.

Cabinet type: SPMA = single-party majority; SPMI = single-party minority; MWC = minimum winning coalition; MC = minority coalition; OC = oversized coalition; NP = nonpartisan. Cabinet type reflects the status of the government on 31 December 2014 or on the final day of the cabinet in office (except in those cases where defections are themselves the cause the end of the cabinet, in which case the figure reflects the type immediately before the event causing change of government). Significant changes of cabinet type are specified in footnotes.

Figures for parliaments measured on 31 December 2014 or, for parliaments facing election during 2014, on the most recent data point before the election (usually 1 January 2014; see individual country reports for full details).

Milanović I began as an oversized coalition (see the Croatia country report for more details) but parliamentary defections reduced it to a minority coalition by the end of the year.

Anastasiades I began as a minimum winning coalition, but departure of the Democratic Party resulted in a minority coalition, though with Cyprus’ presidential form of government, the coalition status is not solely determinative of government formation.

Although the Rusnok I government in the Czech Republic was nominally nonpartisan, one member retained his party membership in the Christian Democratic Union and others maintained close but non-official ties to the Social Democratic Party.

Stubb I began as an oversized coalition but departure of the Green League resulted in a minimum winning coalition.

Formal support from six independents gave Straujuma I many characteristics of an oversized coalition

Butkevicius I began as an oversized coalition but departure of Electoral Action of Poles in Lithuania resulted in a minimum winning coalition.

Ponta II maintained an oversized coalition until 26 February 2014 when departure of the National Liberal Party pushed it briefly into minority coalition status pending a reconfiguration of the government as Ponta III two weeks later with a minimum winning coalition.

The presidential system of the United States does not fit easily into categories used in the Yearbook. The Obama II government included one member of the opposition Republican Party.

Minimum winning coalitions began 2014 as the modal form of government with 46% of all cases and ended also as the majority form in 54% of all cases.

Table 3. Cumulative index of political events

Notes

a For a cumulative index of the period 1991–2001, see Katz and Koole (Reference Katz and Koole2002: 890–895). For a cumulative index of the period 2003–2012, see Bågenholm et al. (Reference Bågenholm, Deegan-Krause and Weeks2013: 14–19).

b Unless otherwise specified, listings for ‘Institutional change’ relate to the inclusion of this formal category or a similar category within the country chapter. In some cases authors list significant institutional changes within other categories and mark these cases with appropriate footnotes.

c Listed in the cumulative index in Caramani et al (Reference Caramani, Deegan-Krause and Murray2012: 3: 23) as ‘Institutional change’ but listed changes are not included under a separate formal heading within the country chapter.

d Not mentioned in the cumulative index in Caramani et al (Reference Caramani, Deegan-Krause and Murray2012: 3: 23).

e Not mentioned in the cumulative index in Biezen and Katz (Reference Van Biezen and Katz2004, Reference Van Biezen and Katz2005, Reference Van Biezen and Katz2006).

f Caramani et al. (Reference Caramani, Deegan-Krause and Murray2012: 3: 23) lists minor changes linked to cabinet formation (Di Rupo I, 6 December 2011) after the very long ‘transition’ cabinet (Leterme II).

g Major institutional changes agreed on in 2011 but not implemented until 2012.

h First included in the PDY in 2007.

i First included in the PDY in 2013, but a record of elections and governments is provided for previous years.

j The two rounds of the Croatian presidential elections spanned 2009–2010.

k Not listed in 2013 PDY table.

l Institutional change listed under alternative heading (including ‘Constitutional amendment’, ‘Constitutional reform’, ‘Institutional reform’ and ‘Reform programme’).

m Not mentioned in the cumulative index in Bale and Biezen (Reference Bale and van Biezen2008).

n Listed in Caramani et al (Reference Caramani, Deegan-Krause and Murray2012: 3:23) because country chapter includes heading for ‘Institutional change” related to changes that did not gain formal approval during the period in question.

o Not mentioned in the cumulative index in Biezen and Katz (Reference Van Biezen and Katz2006).

p Caramani et al (Reference Caramani, Deegan-Krause and Murray2012: 3:23) inadvertently locates its reference to 2011 ‘Institutional changes’ in the category for ‘Upper house changes’.

q Caramani et al (Reference Caramani, Deegan-Krause and Murray2012: 3:23) refers to minor changes occurring outside the normal cycle of upper house changes.

r Previous editions of the PDY inadvertently list Switzerland's upper house elections in 2010 rather than the correct date of 2007.

s Switzerland's Federal Council includes seven members elected for four-year terms but not simultaneously. Dates listed here correspond to years in which new federal councillors took office.

The mainstream EU-friendly party groups (i.e., the European People's Party (EPP), Socialists and Democrats (S&D), and the Alliance for Liberal Democrats of Europe (ALDE)), on the other hand, all lost seats. The EPP's seat share decreased by more than 6 percentage points and the smaller ALDE by nearly 2 percentage points. However, EPP remained the largest group with almost 30 per cent of the seats, and together the three groups still control 63 per cent of all seats. Another 7 per cent lies in the hands of the Greens, who tend to support integration and oppose EU efforts only in specific areas, and a final 7 per cent (up 2 percentage points from the previous period) is controlled by the United European Left-Nordic Green Left (GUE-NGL), whose ideological commitments make it difficult to cooperate with groups such as the ECR or the EFDD.

Women gained 276 of the 751 EP seats elected in 2014 – a share of 36.8 per cent and an increase of 1.6 percentage points, which continued the unbroken trend of increase in every EP election since the elections began in 1979. However, the overall gain between 2009 and 2014 was relatively small compared to the 4.8 percentage point increase between 2004 and 2009, and it concealed increasing regional differentiation. Among the 15 states participating in the EU from the mid-1990s, the share of women elected to the EP has increased from 30 per cent in 1999 to 34.5 per cent in 2004 to 36.9 per cent in 2009 to 40.2 per cent in 2014. In Sweden, Finland and Ireland, women took more than half of the seats in 2014. Among the ten countries that entered the Union in the early 2000s, the rates have been considerably lower, and though the share of women increased from 22.9 per cent in 2004 to 27.2 per cent in 2009 (about the same rate of increase as the other Member States), the share of women in this group actually dropped in 2014 to 26.5 per cent (and a similar drop occurred for the newer accession states of Croatia, Bulgaria and Romania). Significant increases in a few of the newer entrants (the percentage of women among Malta's MEPs increased from 0 per cent in 2009 to 67 per cent in 2014, and in Slovenia the share increased from 29 per cent to 38 per cent) were outweighed by drops in others that exceeded 15 percentage points (Bulgaria, Cyprus, Hungary and Lithuania, with one woman out of 11 MEPs – the lowest level in the EU in 2014).

As Table 1 shows, clear differences in gender representation also emerged across party group lines and roughly corresponding to left-right ideological scales. The GUE-NGL group maintained parity in the number of men and women, and the social-democratic S&D and Greens recorded only slightly lower ratios with approximately 45 per cent women. The share of women in the liberal ALDE was slightly above the overall EP average of 37 per cent, while the Christian Democratic EPP delegation included 30 per cent women and in the ECR the share was just over 20 per cent.

In many countries the shifts in voting appear to reflect a desire by voters to punish incumbent governments, and in particular the party of the prime minister. The two incumbent parties in Ireland lost a total of 28 percentage points compared to the 2011 national elections, the Popular Party in Spain lost 18 points, and the Moderate Party in Sweden lost 16 points. In France, the Socialist Party suffered its worst-ever EP election performance, winning just 14 per cent of the votes. Even though ideological tends are more difficult to spot on a country-by-country basis, there does appear to be a minor overall shift to the right in comparison to the 2009 EP elections and recent national-level elections: although the EPP group lost by far the most EP seats, the elections produced slightly greater gains by parties even further to the right. The main exception to both the anti-incumbent and rightward trends is Italy, where the ruling Democratic Party won just over 40 per cent of the votes, which is the largest share an Italian party received in any national-level election since 1958.

Considering the anti-incumbency tendency, it is perhaps not surprising that many new parties managed to win representation. The delegations of 20 EU Member States included parties new to the EP (Mudde Reference Mudde2014), with 12 of these parties having not even been elected to a prior national parliament. Although many of the new parties emerged in Central and Eastern Europe (the Czech Republic's Alliance of Dissatisfied Citizens, 16.1 per cent; Bulgaria Without Censorship, 10.7 per cent; Slovenia's I Believe, 10.5 per cent; Sustainable Development of Croatia, 9.4 per cent; Slovakia's Ordinary People, 7.5 per cent, and New Majority, 6.8 per cent), many other major new players emerged in the West (Britain's UKIP, 26.6 per cent; Italy's 5 Star Movement, 21.2 per cent; Spain's We Can, 8.0 per cent; Alternative for Germany, 7.0 per cent; Greece's The River, 6.6 per cent; Sweden's Feminist Initiative, 5.5 per cent). In fact, although the seat gains by Eurosceptic and far-right parties gained the most media attention, those gains are matched by the number of seats won by other new parties with anti-incumbent emphasis and weak or mixed ideological orientations, and this latter shift may ultimately prove to be the more consequential.

Changes in the composition of parliaments and cabinets

In sharp contrast to the European elections and to the national elections of the previous year, incumbents performed reasonably well in the relatively few national-level parliamentary elections in 2014. Only nine countries held elections and only six of these followed the pre-established electoral schedule; three others came ahead of schedule, early by 18–36 months. In four of the eight cases where parliamentary elections shaped executive selection (the United States is an exception here), voters returned incumbent (and right-of-centre) governments to office: Hungary, Latvia, Japan and New Zealand. In the other four cases, government composition changed after election, and in these cases the political direction of the shift varied widely: in Sweden, a centre-right government was followed by a Social Democrat-Green coalition; in Bulgaria, a Socialist-led coalition (and a brief caretaker government) gave way to a mostly right-of-centre coalition led by Boyko Borissov; in Belgium, one broad coalition replaced another, though the successor was marked by the absence of the Socialists and the presence of the New Flemish Alliance; in Slovenia, the Social Democrats and Pensioners parties remained in government, but the dominant player in the new coalition was a completely new party with an unclear ideological profile. The new government of the Czech Republic (resulting from elections occurring in late 2013) also included a large and amorphous new party in coalition with Social Democrats, which replaced a largely unwanted president-appointed interim government. Governments changed without elections in seven countries (Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Italy, Poland and Romania), but in each case the premiership remained in the hands of the same party. The year's presidential elections also produced change, with government-supported candidates losing all four races (though in the case of Lithuania, the winning candidate was an independent incumbent).

The overall composition of governments changed slightly during 2014. The minimum winning coalition not only retained its long-held position as the most common cabinet type, but saw its share of governments rise from a plurality (43 per cent) to a majority (54 per cent) during the course of 2014, largely at the expense of oversized cabinets, which dropped sharply (from 30 to 16 per cent). Overall, the share of governments that could count on a parliamentary majority was 81 per cent by the end of the year, down slightly from 84 per cent at the beginning of the year. The relative share of coalition-based and single-party governments stayed relatively constant, with a stable 86 per cent of governments composed of more than one party.

Figure 1 presents all of the governments in office during 2014 according to age and gender composition. An entire generation separated some of these governments from others: Japan's Abe II and III governments were the oldest with an average age of just over 60, while Estonia's Rõivas I was the youngest with an average age of just under 40. Gender distributions also differed widely – from the all-male governments of Slovakia's Fico II and Hungary's Orban III, to the female majority in Sweden's Reinfeldt II (55 per cent) – but as in the past, positions of gender parity were still the outliers rather than the norm.

Figure 1. Distribution of 2014 cabinets by gender balance in government and average age.

Regional patterns endured, but they exhibited slightly less homogeneity than in previous years, when a relatively small range of ages and gender distributions could encompass all of the countries of a region (see Bågenholm et al. Reference Bågenholm, Deegan-Krause and Weeks2013). The Nordic countries again occupied a relatively small region, with age ranges between 45 and 51 and the percentage of women between 40 per cent and 55 per cent. Meanwhile, the governments of continental Western Europe were again older and slightly less gender-balanced than their Nordic counterparts, with an age range between 51 and 57, and percentage of women between 28 and 48 per cent. The lower edge of this gender-parity and age range also included several Anglophone countries, including Ireland's Kenny I, the United States’ Obama II, Canada's Harper III and New Zealand's Key II and III governments. Governments in the eastern Mediterranean region also tended to exhibit higher average ages of between 50 and 60, but these governments were overwhelmingly male, with a percentage of women below 15 per cent. Finally, the governments of postcommunist Europe tended to be both more male and younger, under 50 years of age and a share of women ranging from as high as 40 per cent to as low as 0 per cent.

In a departure from previous years, more governments departed from these regional patterns: the Renzi I government in Italy moved far from the Mediterranean pattern with a younger and gender-balanced profile (41 per cent female, and an average age of 49) that fits within the Nordic range. The Cerar I government in Slovenia and the Kopacz I government in Poland also moved toward gender balance, which is unusual in the postcommunist region, while at the same time moving toward an older profile that put them both within the continental Western European range. Poland's Tusk II and Lithuania's Butkevicius I governments were also older than the regional norm, though they were closer to the regional norm in gender balance, and the older and more male Rusnok I (interim) in the Czech Republic and Orban II and III in Hungary located those countries in the eastern Mediterranean group (and the all-male Orban III government was an outlier even in this heavily male group). The Abbot I government in Australia also fits into the middle of the eastern Mediterranean range, and Belgium's Michel I, both younger and more male than the regional norm, approached the Eastern European range.

Gender composition in national parliaments stayed stable during 2014, with the average share of women in parliament dropping slightly, from 26.4 to 26.2 per cent. About half of this drop is the result of replacements and substitutions during parliamentary terms, but the other half resulted directly from parliamentary elections. In the eight countries in which parliamentary elections caused a reallocation of parliamentary seats during 2014 (again unique institutional factors in the United States – this time the lag between election and installation – mean that its election had no effect in 2014), the share of women decreased by an average of just over 1 percentage point. Election-related reductions in the share of women took place in five cases, including declines as high as 3.3 percentage points in Belgium and 4 percentage points in Latvia; election-related increases in women's representation came only in Japan (1.4 percentage points) and Hungary (0.1 percentage point). Subsequent changes in Hungary's 2014 election, however, raised its female representation from 9.4 to 10.1 per cent, for the first time bringing representation of women above 10 per cent in the national parliament of every EU country.

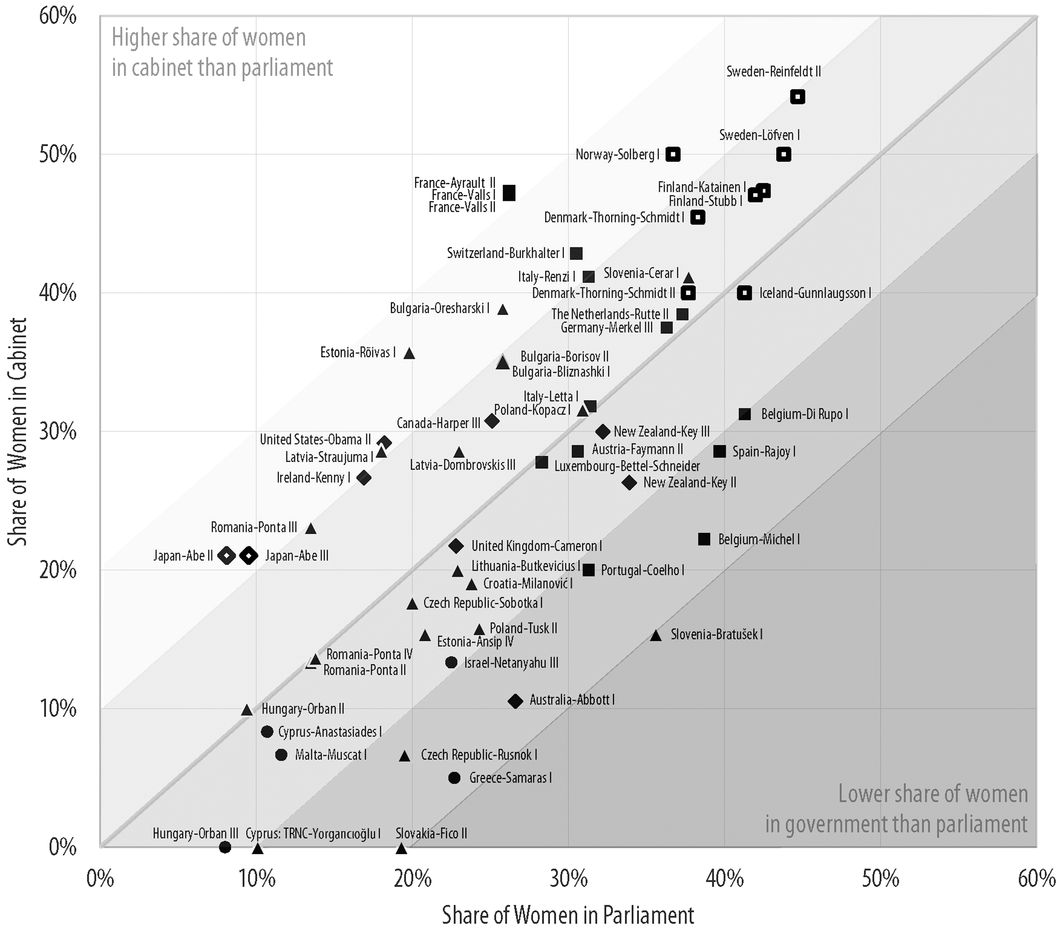

Figure 2 compares the share of women in parliament with the share in government (a comparison newly available because of additional data collection at the parliamentary level). As might be expected, the figure shows a strong correlation (r = 0.66), but there are significant outliers in both directions, with the difference in some cases exceeding 20 percentage points. At the beginning of 2014, Australia's Abbott I government exhibited the strongest deviation from the norm at 26 per cent women in parliament but only 5 per cent in the cabinet, but the addition of a second female cabinet member brought it slightly closer to the norm and into the same range as Slovakia's Fico II, Greece's Samaras I, the Czech Republic's Rusnok I, Belgium's Michel I and (at with the departure of a female cabinet member near the end of its term) Slovenia's Bratušek I. In the opposite quadrant, the three governments of France included nearly 50 per cent women despite a parliament in which women had only a 25 per cent share. Other noteworthy deviations in this direction included Estonia's Roivas I, Bulgaria's Oresharski I, Switzerland's Burkhalter I and Norway's Solberg I. The Nordic countries not only tended to have a higher level of women in parliament, but also a higher positive differential between share in government and share in parliament; Eastern Mediterranean countries exhibited the opposite pattern, with low levels of women in parliament and even lower levels of women in government.

Figure 2. Distribution of 2014 cabinets by gender balance in parliament and government.

The format of the Yearbook

The Yearbook includes 37 countries and covers the period from 1 January 2014 to 31 December 2014. As in the earlier editions, each country report is broken down into a number of sections, with an emphasis on the inclusion of comparable, systematic data. Except in rare occasions where categories do not fit country-level idiosyncrasies, each report follows a common overall framework:

-

• Introduction

-

• Election report

∘ Parliamentary elections

∘ Presidential elections

∘ European elections

∘ Subnational elections

∘ National initiatives and referendums

-

• Cabinet report

-

• Parliament report

-

• Institutional changes

-

• Issues in national politics

The absence of a heading simply indicates the lack of relevance of that particular topic in a given year. In addition to yearly updates of cabinet and parliament composition, country reports usually conclude with a section on issues in national politics, but discussions of these issues may also appear earlier in discussions of elections and cabinet formation. As part of our transition to the online interactive database of the Political Data Yearbook: Interactive (www.politicaldatayearbook.com), we have standardised data tables for elections and cabinets. In addition to new tables on party affiliation and gender among members of parliament, country reports now also include a new table on significant changes within the party system and party leadership.

Relevant data under the more ‘variable’ headings, on the other hand – that is, under those headings that are not necessarily relevant to each country – are reported for the following countries:

General elections to the lower house of parliament:

Belgium, Bulgaria, Hungary, Japan, Latvia, New Zealand, Slovenia, Sweden, United States

Elections or systematic changes to the upper house of parliament:

Austria, Belgium, Canada, France, Germany, United Kingdom, Czech Republic, United States

Presidential elections (direct elections only):

Croatia (first round; second round in 2015), Lithuania, Romania, Slovakia

Elections to the European Parliament:

All European Union Member States

New and returning cabinets:

Belgium, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Hungary, Italy, Japan, Latvia, New Zealand, Poland, Romania, Slovenia, Sweden

Results of national referenda:

Cyprus (Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus), Denmark, Lithuania, Malta, Slovenia, Switzerland

Institutional changes:

Belgium, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, The Netherlands, New Zealand, Romania, United Kingdom