It depends doesn’t it? Everyone’s got their own idea of punk … punk is to any person what they think.1

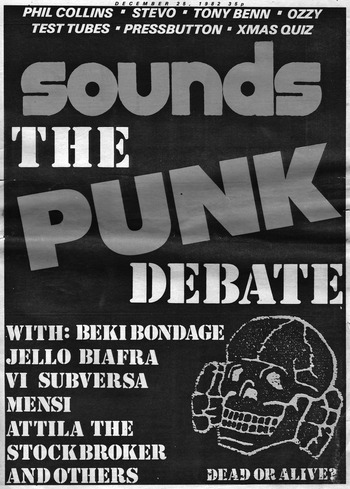

In December 1982, the music weekly Sounds convened a ‘punk debate’ to discuss an article published just a few days before by its features editor Garry Bushell (see Figure 1.1). The subject was a recurrent one, one that flickered in and out of media discourse from 1977 onwards: Was punk alive or, as Bushell now suggested in deliberately provocative fashion, dead?2

Figure 1.1 ‘The Punk Debate’, Sounds, 25 December 1982.

Ostensibly, British punk appeared to be in relatively rude health as 1982 drew to a close. December’s independent charts were dominated by punk or punk-informed bands, with Crass, the Anti-Nowhere League, GBH, Violators, Theatre of Hate, Sex Gang Children and Southern Death Cult all in the top twenty. Among the albums, Factory and Rough Trade LPs jostled for position with the likes of the Abrasive Wheels, Blitz, Poison Girls, Dead Kennedys and The Damned.3 Once again, John Peel’s ‘all-time festive 50’ for 1982 was topped by ‘Anarchy in the UK’ and featured nothing released prior to late 1976. His listeners’ chart for songs issued only in 1982 covered the gamut of punk and post-punk styles, topped by New Order but including Action Pact, The Clash, The Cure, The Jam, Josef K, Killing Joke and Siouxsie and the Banshees.4 Street fashion and even national chart acts retained elements of punk style or attitude across their varied forms. Earlier in the year, too, Crass had proven punk’s ability to retain a subversive intent, spearheading a vocal protest against the Falklands War that provoked questions in parliament and threats of prosecution.5 Bushell, however, sensed punk’s impact was on the wane, going so far as to ask: ‘Does anyone know what punk means anymore?’6

His argument was relatively straightforward: where punk once offered a challenge, ‘at most to the way society is, at least to the jaded musical establishment’, it had now descended into ritual, imitation and narrow-mindedness. ‘A movement which once stood proudly and profoundly against uniformity is … just another uniform’, he insisted. Stylistically, the punk ‘look’ had become formulaic (studs, spikes and leather jackets). In musical terms, thrash or wilful experimentation had replaced songs with a point and purpose. Ideologically, punk had sub-divided into what Bushell described as the hippie-inflected libertarianism of Crass-style bands; the art-for-art’s sake impasse of ‘musical radicalism’ (post-punk); and the blunted ‘street socialism’ of an Oi! scene deformed by a mixture of middle-class prejudice, media misrepresentation and far-right encroachment. Punk’s spirit remained, Bushell contended, but punk itself – as a music and a culture – had become conservative and introspective. ‘If you’re going to change anything you’ve got to look beyond what you’re doing, beyond music. Because music ain’t never going to change anything.’7

Bushell’s polemic proved contentious. Readers wrote in to reassert punk’s continued relevance, pointing to the prescience of various punk bands and punk lyrics; to the local scenes and squats that incubated creativity; to the excitement generated by what Alistair Livingston of the influential Kill Your Pet Puppy fanzine felt was punk’s basic rationale: ‘to create our own lives out of the chaos’.8 The debate itself brought together writers and members of various bands to discuss the problems facing punk in 1982, meaning factionalism, media faddism, commercialisation and a fatalism embodied in the nuclear mushroom cloud that decorated many a record sleeve and the discarded glue-bag that littered too many a gig. Not surprisingly, all thought punk remained an important cultural force (even as they recognised punk’s distance from the cultural mainstream). As interesting, however, were the attempts to answer Bushell’s secondary question: What did punk actually mean?9

For Tom McCourt, bassist with archetypal Oi! band the 4-Skins, punk meant people thinking for themselves; it was neither fashion nor anything the media said it was. John Baine, otherwise known as the punk-poet Attila the Stockbroker, agreed. He understood punk as a medium through which people could communicate their own ideas. For Vice Squad’s Beki Bondage (Rebecca Bond), punk was about being individual and thinking for yourself. And although the Angelic Upstarts’ Mensi (Thomas Mensforth) felt punk should be working class, it was more generally recognised to cut across such social barriers. Poison Girls’ Vi Subversa (Frances Sokolov) described punk as ‘a reaction to power … it’s a reaction of the powerless … We’re expressing something and we’re using music as a medium. But if it stays within there, then we’re going to become either ignored or just so much fodder and so much product … Punk is about life; punk [is] about taking my life for myself.’10

Such broad definition recognised punk’s potential diversity while also reasserting an underlying commitment to engage with, comment on and critique issues relevant to everyday life. The problem, it seemed, was that punk’s initial shock had been absorbed by the music industry and its challenge formalised via a combination of media caricature and the emergence of various subscenes competing to claim ownership of punk’s original intent. To define punk was to emasculate it. But if punk was about ‘changing things’, as Conflict’s Colin Jerwood maintained, then the question still remained as to the extent and focus of its protest.11

Of course, punk had always been open to interpretation. Having emerged to disrupt the cultural equilibrium of the mid 1970s, it did not thereby provide the basis for a coherent or unified movement, be it political or otherwise.12 From the outset, punk’s symbolism, negation and iconoclasm ensured that competing attempts were made to explain or direct its apparent disaffection. First in the music press and then in the tabloids and political periodicals, punk was framed by a politicised discourse that sought to make sense of its emergence and subsequent trajectory.13 Simultaneously, those drawn to – or inspired by – punk picked through the debris left in the Sex Pistols’ wake to find their own means of expression. That these sometimes clashed or appeared contradictory should not be surprising. It was, after all, the tension between punk’s urge to destroy and eagerness to create that allowed its influence to reverberate so far and so wide.

Press Darlings

Punk, to some extent, was a construct of the music press. Certainly, punk’s British variant was first recognised and then interpreted by journalists writing for the three principal music weeklies: Melody Maker, NME and Sounds. By 1974–75, the NME had already focused its attention on a clutch of bands congregated in New York’s Bowery district whose aesthetic drew from the sleazy urbanity of the New York Dolls and Velvet Underground to distil rock’s template and, more importantly, reclaim rock ‘n’ roll for the street-level clubs that once nurtured it.14 Bands such as the Patti Smith Group, Blondie, The Heartbreakers, Television, Suicide and the Ramones all played stripped-back versions of rock ‘n’ roll that found a home under the label ‘punk’ codified by Legs McNeil and John Holmstrom in their magazine of the same name from January 1976. Having existed as an adjective for some time in the music press lexicon of the 1970s, punk finally became a noun.15

Back in Britain, the impulses that informed New York punk (denoted by Savage as urbanism, romantic nihilism, musical simplicity and a kind of teenage sensibility) were sought and eventually applied to the nascent scene forming around the Sex Pistols.16 A dry run of sorts had previously been attempted in 1974, with the NME noting how UK A&R (artists and repertoire) departments were searching for ‘punk rock’ bands. The feature centred on the likes of Heavy Metal Kids and The Sensational Alex Harvey Band, groups that aestheticised and dramatised the delinquent kicks of back-street ‘aggro’.17 None wholly convinced, and the article recognised the ‘nebulousness of the genre and lack of any truly understandable working definition’, thereby paving the way for the Sex Pistols to pose a genuine threat that warranted comparison to the attitude and atmosphere emanating from the US. The Pistols’ first live review, by the NME’s Neil Spencer, referred to their playing ‘60s-styled white punk rock’, while McLaren’s brief sojourn as the New York Dolls’ mentor in early 1975 appeared to make the link explicit.18 The influence of the Dolls, alongside the primal rock ‘n’ roll noise of The Stooges, proved integral to punk’s early sound and attitude. Simultaneously, however, interpretations of British punk soon tended to be viewed through a socioeconomic and cultural lens that distinguished the Sex Pistols from their US counterparts. Punk in the UK, ostensibly at least, contained political connotations absent in America.

The influence of Britain’s music press in the 1970s and early 1980s is difficult to overstate. Between them, Melody Maker, NME and Sounds helped shape the contours of British popular culture, constructing narratives and interpretations of popular music history that maintain today. From the later 1960s, the music press became a vehicle for writers keen not just to report on the comings and goings of chart-toppers and the hit parade, but to inject a cultural and political significance into popular music that took it beyond the realms of commerce and entertainment.19 The NME, in particular, gained a reputation as a taste-setter in the early-to-mid 1970s, becoming a gauge for emergent cultural shifts and a gateway to the subterranean worlds of the post-hippie counterculture and rock ‘n’ roll. Journalists such as Nick Kent and Charles Shaar Murray had honed their craft in the underground press before moving to the NME, from where they seemed to live out – as well as report back on and mythologise – the seedy-glamour of rock bohemianism.20

In terms of readership, the three principal music papers boasted sales of 209,782 (Melody Maker), 198,615 (NME) and 164,299 (Sounds) in 1974.21 Between 1976 and 1980, the NME’s readership rose to a peak of 230,939, while its combined sales with Sounds, Melody Maker and Record Mirror were more than 600,000.22 Neither the mainstream press nor television provided much space for popular music at this time; the music featured on Radio 1 and programmes such as Top of the Pops was circumscribed to say the least. Likewise, the musical content of popular pre-and-early teen magazines such as Jackie or Look-in – along with the flurry of short-lived pop-poster mags that thrived in the early 1970s – concentrated primarily on the relatively narrow remit of a designated ‘teenybop’ audience: glam’s fading glitter dissolving into photo-shoots of The Osmonds and Bay City Rollers. As a result, each copy of Melody Maker, NME and Sounds tended to be shared between those seeking edgier or more critical fare, meaning the readership of the music papers far outstripped the number who bought them.23 By 1979, the National Readership Survey estimated that more than three million people read the weekly music press.24 The impact of punk, moreover, meant both a resurgence in readership (following a mid-1970s slump) and a notable change in style and tone. New writers – many of whom began with their own punk-inspired fanzines – emerged to reflect on and charter punk’s cultural offensive. Most famously, the NME advertised in July 1976 for ‘hip young gunslingers’ to revitalise its staff list, thereby enabling Julie Burchill, Tony Parsons and, ultimately, Paul Morley, Paul Du Noyer, Ian Cranna and Ian Penman to usher in a new generation of music writers. Not dissimilarly, Sounds enlisted Jon Savage (Jon Sage), Jane Suck (Jane Jackman) and Sandy Robertson as its principal punk reporters in 1977, before Garry Bushell joined in 1978 to focus the paper’s attention on the street cultures that flowered around punk. Consequently, Sounds’ readership rose steadily through to 1982, briefly overtaking the NME and, in punk terms, becoming the primary record of its development among the high-street weeklies. Melody Maker, meanwhile, provided space for Caroline Coon to track punk’s emergence before recruiting Savage, Vivien Goldman, Mary Harron and Simon Frith in the later 1970s. Although the 1980s brought cultural, technological and political challenges that effectively neutered the weeklies’ influence, the music press continued to provide a medium through which culture and politics were fused and disseminated. It was, for many, the place where meaning and interpretation of popular music were sought and discovered.

The first writers to engage seriously with the Sex Pistols were Caroline Coon and Jonh Ingham. Though they wrote for rival papers (Melody Maker and Sounds respectively), both were quick to recognise the band’s significance and produce a series of articles that did much to shape the parameters of how British punk was initially understood. Where Ingham emphasised the Sex Pistols’ difference, Coon applied a sociologically honed eye to assert the band’s relevance both to popular music and British society in the context of the mid-1970s. Thus, Ingham’s April 1976 piece on the Pistols focused on style and antagonisms. ‘Flared jeans were out. Leather helped. All black was better. Folks in their late twenties, chopped and channelled teenagers … People sick of nostalgia. People wanting forward motion. People wanting rock and roll that is relevant to 1976’. The music’s energy and power was celebrated; its lack of virtuosity transformed into a virtue; the aura of violence noted. Most importantly, Ingham gave space to Rotten’s decimation of pop’s recent history: hippies, pub rock and even the contemporary New York scene were dismissed as a ‘waste of time’.25 Later, Ingham wrote of ‘boundaries being drawn by the Pistols’, boundaries he defined in more detail in an October issue of Sounds billed as a ‘punk rock special’: youth, an irreverence for rock’s pantheon, a predominantly working-class background, a commitment to doing rather than consuming, a rejection of ’70s style (flares, long hair, platform shoes). Punk was pitted against the music industry and the ‘old farts’ who dominated it.26 ‘The great ignorant public don’t know why we’re in a band’, Rotten is quoted as saying: ‘It’s because we’re bored with all the old crap. Like every decent human being should be’.27

Coon’s interpretation of punk pushed towards more explicit associations. In particular, she made much of the Sex Pistols’ working-class background, using it, first, to explain their evident disaffection and, second, to distinguish punk from a rock ‘aristocracy’ made up of ageing millionaires no longer connected to their audience. ‘It was natural’, she suggested, ‘that if a group of deprived London street kids got together and formed a band, it would be political’.28 In cultural terms, this placed the young punks in opposition to the likes of Mick Jagger – who Coon dismissed as ‘elitist, the aristocracy’s court jester, royalty’s toy’ [a reference to his friendship with Princess Margaret] – and the ‘multi-national corporations’ of Led Zeppelin, Elton John and The Who. In contrast to bands such as Pink Floyd, Soft Machine, Yes, Genesis, Jethro Tull and Queen, who comprised ‘middle-class, affluent or university academics’ playing ‘progressive rock’ dependent on musical dexterity, Coon presented punk as a return to street-level music that the ‘average teenager’ could relate to and make themselves.29

Class formed the basis of punk’s ire, Coon suggested. Her early interviews with the Pistols, The Clash and The Damned centred on broken homes, criminal convictions and failed education.30 She probed for political comment and opinion, relating punk’s antipathy towards contemporary rock ‘n’ roll to the ‘increasing economic severity’ of the mid-1970s. Punks ‘reflected and expressed the essence of the society they experienced every day’, Coon argued. Theirs was the ‘violence of frustration’; a rejection of ‘romantic escapism’. ‘In 1967 the maxim was peace and love. In 1976 it is War and Hate’.31

As this suggests, Coon and Ingham did much to define punk as a distinctive cultural form. They helped denote its musical characteristics and drew various bands under its label to provide a sense of coherence.32 Not only did they highlight punk’s irreverence to rock’s established canon, but they also linked such iconoclasm to a sartorial rejection of all things hippie that exposed a generational rupture and placed attention on punk’s audience as much as on the bands.33 Most significantly, perhaps, they invested punk with political connotations that tied cultural disaffection to the socioeconomic context from which it emerged. In other words, punk was presented as a creative outlet for a generation coming of age in a period of crisis.

As we shall see, such analysis did indeed reflect attitudes expressed by many of those caught in the Sex Pistols’ wake. More to the point, the various elements brought together to give form to British punk remained in flux and open to interpretation. Almost from the outset, a debate ensued as to punk’s significance and intent. For the NME’s ‘young gunslingers’, punk’s relevance was all too clear. Punk was ‘reality rock ‘n’ roll’, Julie Burchill insisted, akin to ‘being on the terraces’ with an audience comprising ‘working-class kids with the guts to say “No” to being office, factory and dole fodder’.34 For Parsons, punk meant ‘amphetamine-stimulated high energy seventies street music, gut-level dole queue rock ‘n’ roll, fast flash, vicious music played by kids for kids’.35

Crucially, Burchill and Parsons appeared to capture punk’s spirit in written form. Where Coon’s punk sympathies revealed roots that stretched back to the sixties counterculture, Burchill and Parsons were seventeen and twenty-two respectively when they joined the NME.36 Both, along with Sounds’ Jane Suck and Jon Savage’s early writings, offered breathless prose that read as punk felt; they lashed out at non-believers and revelled in punk’s impudence. Burchill, in particular, embraced punk for its clearing a space for new voices (young working-class voices) to enter pop and the media; the music was all but immaterial. Parsons was more earnest, seizing on punk’s social commentary and urbanity to politicise its relevance in the face of the media storm and municipal bans that followed the Grundy incident. Famously, too, Burchill and Parsons embodied punk’s cultural shift by barricading their own space in the NME offices, building a ‘bunker’ from which to do (sometimes physical) battle with the hippies and boring old farts who maintained the rest of the paper.37

Over time, as punk proliferated, so Burchill and Parsons’ demands hardened. Those who seemed intent to ride punk’s bandwagon were summarily dismissed.38 Political rhetoric and signifiers were assessed and judged against a self-defined street-savvy socialism built on class awareness and anti-racism. In particular, those flirting with swastikas or fascism were taken to task.39 The ‘battle of Lewisham’, in which anti-fascists clashed with far-right National Front (NF) marchers on 13 August 1977, became bound to Burchill and Parsons’ vision of punk activism.40 ‘The honeymoon’s over’, Parsons wrote in October, the ‘naïve euphoria of 1976 has subsided enough for everyone to turn on the light, straighten the hem of their plastic bin-liner and work up the bottle for imperative re-evaluation judgements’.41 Inevitably, such high expectations led to disappointment. By the end of 1977, both Burchill and Parsons despaired of what they saw as the dilution of the Sex Pistols’ genuine rage and the co-option of punk’s early challenge by the media, music and clothing industries. Rock ‘n’ roll was dead, they concluded, with punk but another illusion of rebellion transformed into commodity.42

For others, punk’s politics and form should never have been so rigidly defined. Before joining Sounds in the spring of 1977, Jon Savage used his London’s Outrage fanzine to celebrate punk’s ability to reflect Britain’s social and psychological faultlines, going so far as to predict the development of a ‘peculiarly English kind of fascism’ – ‘mean and pinched’ – with Margaret Thatcher as the ‘Mother Sadist’.43 Punk, Savage suggested, was a mode of critique rather than a definite answer or solution. It confronted, challenged and gave vent to a disaffection that was resonant but politically ambiguous. Once punk’s shock and provocation had gained space and attention, moreover, so Savage moved to chart its continued evolution. Not only did he predict that the mainstream would fill with punk clones and nouveau pop flirtations with the ‘new wave’, but he also held fast to punk’s potential to engage. ‘Fresh energy’ would be provided by the ‘regional centres’, he contended, while new sounds and influences would be sourced to map Britain’s ‘mass nervous breakdown’ as ‘crisis’ gave way to post-industrial (and post-imperial) stasis.44

In effect, Savage pointed towards what he called ‘post-punk projections’: a ‘New Musick’ built on textures (‘harsh urban scrapings/controlled white noise/massively accented drumming’) that challenged preconceived notions of punk but reflected the sense of anxiety that would usher in the 1980s. On relocating to Manchester in 1979, he pursued punk’s aesthetic through scrutiny of bands such as Joy Division, Wire, Throbbing Gristle and Cabaret Voltaire, focusing on those he felt best chronicled their time and complemented punk’s urge to question and experiment.45

Savage was not alone in exploring punk’s impetus beyond the confines of London and rock ‘n’ roll. Integral to the culture’s vitality was the emergence of local scenes that either reinforced or reimagined punk’s template. In particular, punk’s do-it-yourself (DIY) ethos and the expansion of independent record labels ensured the music press enlisted regional correspondents to report back on places where, throughout the late 1970s and early 1980s, punk continued to inspire. The most notable of these was Paul Morley, who kept the NME informed about Manchester before moving to London and cultivating his own theories of pop’s cultural significance.46

Morley’s early communiqués from the North West made much of punk’s serving as a pivotal moment. Before the Sex Pistols played the city’s Lesser Free Trade Hall in the summer of 1976, he reported, Manchester had not existed as a ‘rock ‘n’ roll town’: ‘it had no identity, no common spirit or motive’. Thereafter, bands began to form, venues opened, fanzines developed and a recognisable community emerged to ‘attack’ the ‘insipidity’ of 1970s rock. From such a premise, Morley located punk’s importance in its opening up ‘all the freedoms that can be imagined’.47 In other words, punk facilitated new ideas, vocabularies and sounds to reinvigorate popular music at both a regional and national level.

Initially at least, Morley embraced a range of punk styles. Though he favoured its more cerebral exponents (Buzzcocks, Magazine, The Prefects, Subway Sect, Joy Division), he recognised punk’s urge to protest, writing favourable reviews of proto-Oi! bands such as Sham 69 and Angelic Upstarts.48 Far from bemoaning the death of rock ‘n’ roll, Morley celebrated its rebirth. There must be choice, he argued in early 1979, as he surveyed a burgeoning underground of punk-inspired bands ready to maintain the challenge to radio playlists and the music industry.49

Simultaneously, Morley began to warn against those who subscribed to a definitive punk sound or aesthetic. He disavowed any attempt to politically align punk. Punk’s politics lay in its practice, he argued, in its ability to pleasure, surprise, transgress, inspire, question and imagine. The sloganeering of the Tom Robinson Band or blunt social realism of The Jam served only to stifle its potential.50 Nor did he have time for those he felt offered style over substance. A band such as Bauhaus, for example, who dramatised punk’s foreboding in gothic imagery, were described as performing ‘rehearsed melodrama’ that revealed them to be little more than ‘bullshitters in a fine art shop’.51 Most importantly, he recognised punk as a catalyst for pop’s perennial renewal. Just as his prose became evermore baroque and infused with hints of postmodern theory, so he eventually renounced rock in favour of music that sought to redraw the boundaries of pop by avoiding cliché and embracing technology. By the 1980s, he dismissed those clinging to punk as being trapped in a kind of ‘folky traditionalism’, preferring instead to champion groups that at once celebrated and critiqued pop’s pretensions and possibilities.52

If Savage and Morley saw punk’s challenging the conventions of cultural form as crucial to its impact, then others found greater purpose in its reclaiming rock ‘n’ roll as a vehicle for rebellion. On joining Sounds in 1978, Garry Bushell reasserted the notion of punk as working-class protest, focusing on bands such as Sham 69, The Ruts, Angelic Upstarts and Cockney Rejects to define an authenticated version of punk mythology. That is, a working-class culture made by and for the kids from the council estates and football terraces that Burchill, Parsons and Sniffin’ Glue’s Mark Perry envisioned back in 1976–77.53

Bushell’s take on punk was inherently political. As a young member of the International Socialists (Socialist Workers Party [SWP] from 1977) he had been quick to recognise punk as a cultural response to the socioeconomic travails of the mid-1970s.54 Not only did he urge his comrades to take punk seriously in the pages of Socialist Worker, but he actively supported Rock Against Racism (RAR) and contributed to its fanzine, Temporary Hoarding. Punk reflected the anger of a generation that had graduated from school only to serve its time on street corners and the dole, he argued. It was the SWP’s job to channel such revolt ‘into a real revolutionary movement’.55 Though he had left the party by the turn of the decade, Bushell retained what he termed a ‘street socialist’ outlook that prioritised collective action rooted in the working class itself. This, in turn, would shape his conception of Oi! as ‘a loose alliance of volatile young talents, skins, punks, tearaways, hooligans, rebels with or without causes united by their class, their spirit, their honesty and their love of furious rock ‘n’ roll’.56

From 1980 to 1983, Bushell was punk’s most visible champion in the music press. While record industry and media attention turned to the styles and sounds that supposedly superseded punk, Bushell continued to cover those who proudly bore the label into the 1980s. ‘The anarchy beat stayed on the streets’, he argued in a survey of punk circa 1981, ‘growing, changing, transmutating, diversifying, the bands staying true to their roots or getting forgotten, and finally resurging now stronger than ever’. Punk meant thinking for yourself, freedom of speech and finding room to move. It was not about art school pretension but ‘energy and teen rebellion – even when it’s only rebellion against the boredom’.57 Bushell retained a critical perspective. He chastised those who appeared absorbed into the music establishment (including The Clash by 1979) or prioritised musical experimentation (Magazine, Public Image Ltd). He condemned bands that chose to circumnavigate rather than engage with either the music industry or society more generally.58 By conceiving Oi! as a distinct cultural form, he sought to tie punk into a broader stylistic and class-based lineage that ran through teds, mods and skinheads onto punk and 2-Tone.59

Punk, then, was both constructed and deconstructed within the music press. Indeed, those who most convincingly defined punk and provided it with a sense of purpose were often moved to mourn its failings once expectations ceased to be met. By as early as mid-1977, ‘punk rock’ had been reduced to a basic sound, what the NME labelled ‘ramalamadolequeue’, ensuring that many bands and journalists looked to move beyond the parameters of speedy three-chord rock ‘n’ roll. Those who retained a recognisably punk style were increasingly criticised for succumbing to cliché or negating its original spirit of challenge and change.

Nevertheless, the shadow of 1976–77 remained cast over much of what followed into the 1980s. The cultural spaces cleared by punk were understood by most in the music press to have enabled the innovations of ‘post-punk’ and ‘new pop’. Punk informed the aesthetic and the socialist discourse that underpinned RAR and continued to inspire bands such as the Redskins, bIG fLAME and Test Dept – none of whom played archetypal ‘punk rock’. Punk was also recognised as the stimulus for the independent labels that flowered from 1977 and the social-realist edge that fused punk with ska to create 2-Tone.60 Even those who charted journeys into post-punk’s more esoteric corners noted a connection to the breakthroughs of 1976–77. So, for example, writers such as Richard Cabut, Steve Keaton and Mick Mercer plotted punk’s transgressive undercurrent towards a ‘positive punk’ that foresaw and fed into goth.61 Not dissimilarly, Chris Bohn and Dave Henderson followed Throbbing Gristle’s industrial lead through the new musick into a brutalised hinterland that connected transglobal artists revelling in the abject and extreme.62 For those reading the music papers, such narratives and debate helped make sense of the sounds and cultures that unfolded from 1976, informing their understanding of popular music and providing them with templates and opinions to actively embrace or react against.

The Sun Says (So It Must Be True)

If the music press provided multiple interpretations of punk’s emergence and development, then the wider media tended towards a more reductionist reading.63 Punk became the latest in a long line of youthful ‘folk devils’ that were defined culturally but simultaneously presented as indicative of some deeper malaise.64 Much of the reporting that followed the Sex Pistols’ appearance on Today was fanciful: the epitome of a fabricated ‘moral panic’ designed to sell copy rather than provide insight on a distinct youth culture.65 Even so, the version of punk captured in the media glare contributed towards both the evolution of the culture and the ways in which it was more broadly understood. First, the mainstream media’s recoil from punk became part of its appeal, a sign of punk’s impact and proof of the media fallacies that helped fuel its critique. Second, media exposure gave greater form and substance to punk’s cultural identity. Though press and television reports often caricatured and distorted punk’s early stirrings, they also fed back into the culture to fashion its myths and codify its signifiers.66 Third, media coverage enabled access to those beyond the remit of the music papers or early punk milieu. In so doing, it served to raise punk above the level of a subculture. Finally, as Bill Osgerby has noted, the media discourse that enveloped punk contributed to the dramatisation of a wider sense of crisis that characterised Britain in the mid-to-late 1970s.67 Beneath the mock outrage of the tabloids lay insecurities and socioeconomic tensions for which punk provided a ready outlet.

Initially at least, the mainstream media’s take on punk swung between intrigue and incredulity. Early exposés in the tabloids concentrated on punk style; a ‘crazy … shock-cult’ defined by chains, rips and colour. So, for example, The Sun featured ‘Suzie’ (later Siouxsie Sioux) and Steve Havoc (later Severin) in torn and see-through clothes to explain the ‘craziest pop cult of them all’, while the Sunday People pictured a young punk – Mark Taylor from Newport, who along with his friends Steve Harrington (Steve Strange) and Chris Sullivan had been quick to pick up and adopt new styles glimpsed on trips to London and Ilford’s Lacy Lady – replete with nose chain. The report read: ‘If you thought you’d seen it all, dig this latest line in crazy gear. As you can see, one end of that chain is actually through his nose, the other through his ear … It’s the face of a Punk Rocker, Britain’s latest pop trend. And there’s more to the whole bizarre look than this. Like vividly dyed hair, oozes of make-up, ballet tights and ripped plastic or leather T-shirts. And that’s for fellas. The girls are even more way out. They wear razor blades for earrings as well’.68 Though passing reference was made to punk’s being born of economic recession and reaction against rock’s excesses, the emphasis was on punk as fashion.

Not surprisingly, perhaps, more in-depth enquiry came from the broadsheets and features such as those on the BBC’s Nationwide and LWT’s Weekend Show (both 1976). These took their cue from Coon, Ingham and Parsons’ early writings, picking up on the Sex Pistols’ cultural offensive against the pop ‘establishment’ and what McLaren defined as their attempt to ‘transform what is basically a very boring life’. Punk, McLaren insisted on Nationwide, was about ‘kids’ reclaiming rock music, ‘making music from the streets … born out of a frustration to get something across that is of their own’.69 From such analysis, the trope of ‘dole queue rock’ briefly embedded itself in the media lexicon.70

Ultimately, it was the Sex Pistols’ appearance on Today that fixed the press’ conception of punk. Attention thereafter focused on punk’s anti-social mannerisms – the swearing, the spitting and the violence. Already, punk’s association with the COUM Transmissions exhibition Prostitution, held at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in October 1976, had presaged the furore that engulfed the Sex Pistols. The exhibition, which effectively launched Throbbing Gristle’s mission to subvert popular music, also featured the punk band Chelsea (playing as LSD) and art works that comprised Cosey Fanni Tutti’s (Christine Newby) explorations in pornography and sculptures adorned with used tampons.71 The media took the draw, reigniting debate on the use of public money to fund the arts and feeding concern as to the extent to which such a ‘celebration of evil’ could undermine Britain’s supposed moral values.72 Notably, however, the much-repeated quote of the Tory MP Nicholas Fairbairn, that ‘these people are the wreckers of civilization’, was juxtaposed in the Daily Mail next to pictures of Siouxsie Sioux, Steve Severin and Debbie Wilson, all of whom had attended the event’s opening ‘party’.73

The media response to the Grundy incident would eclipse all this of course. As expletives and bodily functions became headline staples, so punk’s challenge was distilled into crude caricature: the ‘foul mouthed yob’ with coloured hair and safety pins who, by the 1980s, had become a light entertainment cliché.74 More immediately, punk appeared to tap into a perennial fear of disaffected youth that found renewed expression in a period of recession and growing unemployment.75 If the Sunday People’s verdict on punk was that ‘it is sick. It is dangerous. It is sinister’, then the Daily Mirror felt punk was ‘tailor-made for youngsters who feel they have only a punk future … a brave new generation of talent and purpose is turning sour before our very eyes’.76 In effect, any substance contained within punk’s critique was buried beneath media narratives designed to stoke age-old concerns or confirm predetermined opinion. Punk was caught in a media freeze-frame, primed and ready to decorate tabloid tales of street-fighting, glue-sniffing or obscenity for years to come. In media terms, punk was but a signpost for delinquency and decay.77

Bloody Revolutions

Politics formed but a subtext of the media’s understanding of punk. Intermittently, concern that punk harboured a fascist germ found its way into a tabloid exposé. The Evening News’ John Blake seemed keen on this angle for a while in 1977, belatedly picking up on punk’s use of the swastika to hint at links to the NF.78 The controversies surrounding Oi! in the early 1980s also related to broader media interest in the far-right’s attempts to recruit young skinheads. Having been conceived as an amalgam of punk, skinhead and terrace culture, Oi! became headline fodder once a gig featuring 4-Skins, The Business and The Last Resort at the Hambrough Tavern in Southall on 3 July 1981 was attacked by local Asian youths objecting to the arrival of a large skinhead contingent in an area with a history of racial conflict. Thereafter, the tabloids (and the NME) conflated Oi! with skinheads and racism, a reductionist reading that was nevertheless fuelled by the fact Nicky Crane, a member of the British Movement (BM), was featured on the cover of 1981’s Strength Thru Oi! compilation.79 Even so, Simon Barker made it onto Grundy’s Today programme wearing a Nazi armband without undue fuss in 1976, and the uproar that greeted the Sex Pistols’ commentary on 1977’s jubilee celebrations, ‘God Save the Queen’, focused less on its perceptive critique of Britain’s ‘mad parade’ and more on its reinforcing the Pistols’ yobbish credentials. ‘Punish the punks’, the straplines admonished, as the lyrics were misquoted and attention shifted to the beatings meted out on Rotten, Cook and Jamie Reid in the aftermath.80

For those of an overtly political bent, however, punk’s arrival had definite implications. Its oppositional stance – not to mention its display of political signifiers – contained an obvious appeal to both the left and the right.81 In many ways, punk rekindled the debates of the 1960s and early 1970s as to the meaning of specific (youth) cultural forms and their use as a medium for social and political change. The Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) had, between 1973 and 1975, engaged in a protracted discussion on just such a subject, exploring the extent to which youth cultures were simply the commercialised products of capital or, as the party’s Martin Jacques argued, a formative site of class struggle relevant to prevailing material conditions.82 Paul Bradshaw, the editor of the party youth section’s newspaper (Challenge), actually predicted in mid-1976 that ‘new forms of culture, especially through music, [will] develop and give expression to the problems facing youth’ in a period of rising unemployment and social tension.83 For at least some young communists, songs such as ‘Anarchy in the UK’ and The Clash’s ‘Career Opportunities’ delivered just that. The Young Communist League (YCL) even sent the Sex Pistols an ‘open letter’ in 1977, suggesting a consolidation of punk and communist forces.84

Others on the left were equally alert to punk’s political potential. In the SWP, Roger Huddle joined with Bushell to argue that punk was an expression of youthful (working-class) discontent that needed to be directed into the socialist movement.85 Letters to Militant, Challenge and Socialist Worker debated punk’s progressive and reactionary tendencies; articles wrestled with the relationship between punk, politics and culture.86 Even the Workers’ Revolutionary Party (WRP) overcame its early reading of punk as inherently fascist to include favourable coverage in Young Socialist from mid-1978.87 Though dissenting voices remained, some leftist publications adopted punk graphics in the late 1970s and provided space to interview the more politically committed bands, poets and artists.88 To attend a political festival or benefit at this time was to catch sight of X-Ray Spex, The Ruts, Crisis, Gang of Four, The Pop Group, The Fall and others all too ready to lend support to a cause or, it must be said, take advantage of the opportunity to play live.89 Without doubt, Red Saunders and those who formed RAR saw punk’s inclusion as integral to its success, ensuring that punk bands performed at the carnivals arranged in conjunction with the Anti-Nazi League (ANL) between 1978 and 1981 and at countless gigs organised by local RAR clubs throughout the late 1970s.90 These, as well as high-profile rallies such as that held by the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) in Trafalgar Square in October 1980, helped align punk’s protest to distinct political positions.91

Not surprisingly, perhaps, punk’s champions on the left were relatively young. Some, including Jacques, Huddle and David Widgery, had cut their political teeth in the 1960s and viewed punk within a broader tradition of youthful protest. Others, such as Bushell or Temporary Hoarding’s Lucy Whitman (also known as Lucy Toothpaste), were politicised over the 1970s and recognised in punk a spirit and an approach that complemented (and soundtracked) their own sense of revolt. More searching analysis was occasionally offered. Dave Laing, who in 1976 addressed the CPGB’s Art and Leisure Committee on ‘trends in rock music’, drew from Walter Benjamin to explain how punk’s ‘shock effect’ opened up contested cultural spaces of ideological struggle.92 But the left’s relevance to constructing punk’s meaning or purpose really came with its providing connections between youthful discontent and prevailing sociopolitical issues – be it anti-racism, feminism, unemployment or nuclear disarmament. If, by the 1980s, the theories of Theodor Adorno were more readily applied to explain punk’s failure to overturn the music industry or instigate socialist revolution, then the early enthusiasms that fed into RAR, CND and unemployed demonstrations continued to lend political gravitas to bands, scenes and the records released in the wake of 1976.93

On the right, meanwhile, there were also activists keen to forge links between politics and youth. Though the aged leaderships of the NF and BM were repulsed by popular music in all its forms, seeing it as a ‘manifestation of the jungle’, younger members began to combine their interest in fashion and fascism.94 Not only did an anonymous contributor to the BM’s British Patriot claim to recognise in punk signs of a general rightward shift in rock music, but a cabal of young BM and NF members formed an increasingly visible and assertive contingent among London’s punk audience from 1977.95 This, initially, led to tensions on the far right. According to Gary Hitchcock, ‘a few of us’ were expelled from the BM for being ‘degenerate for going to gigs’.96 But the left’s success in student recruitment and initiatives such as RAR helped prompt the establishment of a Young National Front (YNF) in 1977 and encourage the BM’s cultivation of a skinhead vanguard thereafter.97

The far right’s claims for punk varied. At an organisational level, its engagement formed part of a wider drive for youthful members. In London, Joe Pearce headed the YNF and edited its Bulldog magazine. As a teenager in the mid-to-late 1970s, Pearce appreciated the importance of youth culture to his potential recruits and tailored Bulldog accordingly, focusing on football, music and promoting YNF discos.98 Not dissimilarly, Eddy Morrison used his position as an NF regional organiser to provide the foundations for Rock Against Communism (RAC).99 In the BM, the drive to recruit working-class youth offered a violent political outlet for a mainly skinhead milieu that included Hitchcock, Glen Bennett, the Morgan brothers and Nicky Crane.100

As this suggests, the far right’s adoption of youth cultural motifs reflected its younger members’ coming of age in a period when pop music and subcultural style were established parts of everyday life. Like their rivals on the left, they also accepted popular music and youth culture as a politically charged means of expression. Morrison was a David Bowie fan who endeavoured to find Aryan – or at least European – roots for pop music.101 Pearce, whose brother Stevo ran a ‘futurist disco’ and a punk-informed label (Some Bizarre), focused on street-level youth cultural styles: ‘Punks, Mods, Skins and Teds – All Unite to Fight the Reds!’102 To this end, affinities were sought between nationalist politics and everything from the mod and skinhead revivals of the 1970s to new romantics and football hooligans. Even 2-Tone bands were coveted, though this more than anything revealed the contradictions inherent in a racial interpretation of either popular music or youth culture more generally.103 In relation to punk, the emergence of Oi! was belatedly seized upon as ‘music of the ghetto. Its energy expresses the frustrations of white youths. Its lyrics describe the reality of life on the dole … It is the music of white rebellion’.104

It was, however, through active intervention – stage invasions, sieg heils and co-ordinated violence – that the far right sought to colonise the cultural and physical spaces opened up by punk. Bands were claimed for the nationalist cause irrespective of whether they wanted such attention or not. Gig venues became sites of political confrontation to be fought for and won. Once a band rejected the far right’s overtures, they became a target for reprisal. Most notoriously, Sham 69’s ‘farewell to London’ gig at the Rainbow Theatre in July 1979 was violently broken up by the BM, though less renowned instances were commonplace before and after. Three years on and the YNF attacked a Bad Manners gig at the same venue, warning that ‘our attitude is that bands who are not our friends are our enemies, and will be treated as such … remember what happened to Sham 69’.105

Ultimately, the tenuous relationship between racist politics and existing youth cultures necessitated that the far right form its own variant. This was concentrated around RAC and Skrewdriver, a Lancastrian punk band whose singer, Ian Stuart, first moved to London in 1977 and became involved with the NF. With most punk, Oi! and 2-Tone bands refusing to endorse a fascist following, so Skrewdriver claimed to speak the language of the white working class and set in train what became a transglobal network of ‘white power’ bands that later gathered under the auspices of Blood & Honour.106 The music, initially at least, was crude punk rock, with lyrics that were overtly racist and ultra-nationalist targeted at an audience drawn primarily from a section of the skinhead subculture that fused class and racial identity into a distinctive style.107

The ways by which organised politics informed punk’s cultural development will be explored in due course. The key point here is that both the left and right sought to assign political meaning to punk and provide opportunity for music, youth culture and politics to coalesce. This was never wholly successful; punk and its associated cultural forms remained too amorphous and diverse to forge a coherent politics. But by projecting onto punk ideological intent or potential, activists from the left and right helped delineate the music and youth cultures that emerged from 1976 as sites of political engagement. This, in turn, was further facilitated by a music press that was receptive to ideas of a politicised youth culture wherein music – in terms of both its form and content – mattered beyond the realm of personal taste.108 In the heightened political climate of the late 1970s and early 1980s, punk was utilised to revive the notion of popular music as a vehicle for protest and youth culture as a signal of revolt.

All the Young Punks …

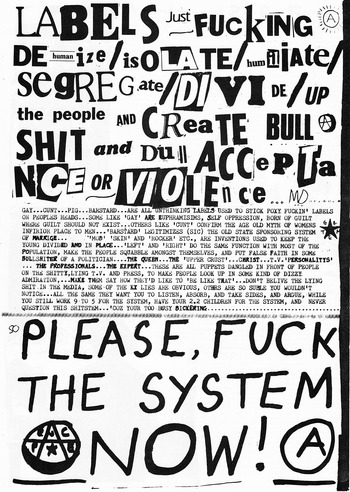

When Johnny Rotten was asked in 1976 if he was happy being known as a ‘punk’, his reply was curt: ‘No, the press give us it. It’s their problem, not ours. We never called ourselves punk’.109 As this implies, there was initially some resistance to a label that had already been used to describe American garage bands from the 1960s and their more recent descendants in New York. ‘New wave’ was preferred by some, even amongst the Sex Pistols’ inner circle, but it lacked the perfunctory offensiveness of a word that contained criminal and sexually subversive etymological roots.110 For Tony Parsons, the term punk was ‘too old, too American, too inaccurate’; it failed to do justice to what he regarded as a genuine upsurge of young British bands who reflected their time and place. ‘Kids rock [sic]’, he suggested, was a more accurate descriptor – if one be needed at all.111 Not dissimilarly, Paul Morley had touted ‘S’ rock, as in ‘surge’, to define the Sex Pistols’ ‘controlled chaotic punk muzak’, while Jonh Ingham made a belated pitch for ‘(?) rock’.112 Nevertheless, the fact that Caroline Coon’s early pieces defined the Sex Pistols as ‘punk’, and the fact that it allowed older journalists to locate the emergent new wave in a recognisable rock ‘n’ roll lineage, meant the term prevailed.113 Although antipathy remained, primarily in recognition of the way such media-devised labels served to ‘dehumanise/ isolate/ humiliate/ segregate/ divide up [and] create bullshit and dull acceptance’ (Toxic Grafity), ‘punk’ was adopted by the mainstream press and, crucially, by Mark Perry, Jon Savage, Tony D (Drayton), Steve Burke, Paul Bowers and others who helped catalogue the embryonic culture at a grass-roots level.114 The impact made by the Ramones, too, should not be underestimated with regard to defining a punk sound and forging affinities with the already branded US scene.115

Beyond the name, of course, the ways and means by which punk was interpreted continued to vary. Punk’s impact was often visceral: it was fun, fast and exciting. Though who and what was (or was not) punk may have formed the basis of perennial schoolyard/college/pub debates, precise definition or prescribed meaning counted little to many of those prompted to form a band, dress up, buy a record or go to a gig in the wake of discovering the Sex Pistols.116 To flick through fanzines or to read the letters published in the music press is to reveal the nebulous ways by which punk was understood and acted upon. For the enthused, punk revitalised popular music – lending credence to the idea that its primary effect was to reassert rock ‘n’ roll’s initial impetus and recover youth culture’s snottily subversive gene.117 Likewise, the oft-cited incentive born of punk’s disregard for musical proficiency (anyone can do it) was not always recognised to contain the implicit political or sociological connotations that it undoubtedly did. Despite certain tropes being easily mouthed – anarchy, boredom, bondage, city, hate, fascism, liar, nowhere, sick, suburbia – The Damned’s insistence that ‘I don’t need politics to make me dance’ rang true for many a self-defined punk rocker.118

Certainly, there was always a degree of disjuncture between the music press’ desire to define musical genres and a youthful embrace of the numerous bands and styles that evolved from 1976. Punk-inspired fanzines, for example, regularly covered anything and everything deemed to exist as an alternative to a perceived mainstream.119 If punk informed the soundtrack of someone’s youth, then its meaning – or resonance – transcended the intellectual conceits of the music press.

For others, punk’s importance ran deeper. At a local level, the fanzines produced from 1976 soon progressed from celebrating fledgling punk bands (and their precedents) to personalised critiques of the music industry and society in general. ’Zines such as Lucy Toothpaste’s Jolt proffered feminist assessments of punk’s early stirrings, while ruminations on the wearing of Nazi symbols found their way into Ripped & Torn before it transformed into the more overtly anarchistic Kill Your Pet Puppy.120 Vague, which began as a fairly conventional fanzine from Wiltshire, eventually developed through in-depth analyses of punk’s sociocultural relevance to expanded essays on situationist practice and the Red Army Faction.121 Rapid Eye Movement, too, morphed from a punk ’zine into a book-length compendium exploring what its founder, Simon Dwyer, called ‘occulture’.122 In so doing, punk served to establish links to currents of political and cultural dissent someway beyond the typical preserve of pop music.

This was undoubtedly the case with regard to the samizdat publications that fused anarchism and punk in the early 1980s. The contents of Anathema, Enigma, Fack, New Crimes, Pigs for Slaughter, Scum, Toxic Graffitti [sic]123 and countless others mixed limited music coverage with political tracts directed against the various organisational and intellectual props of ‘the system’. Collages, poems and essays became essential weapons in the punk arsenal, complementing the words and imagery of bands whose politics were unpicked and assessed in critical fashion. As a result, fanzines formed an integral part of the subterranean networks that connected punk collectives, labels and venues across the UK (and beyond) into the 1980s.

Nor did those who formed bands necessarily limit their understanding of punk to music. From Rotten and The Clash’s insistence that pop should be relevant to its time and place, so punk may in part be measured by its ability to reflect and critique. Quite what this entailed was again open to interpretation. At one end of the spectrum, humour lent itself to irreverence and a wilful puerility designed to offend and titillate in equal measure.124 At the other, a sense of engagement could be defined in terms of social reportage or political activism. For those with a keen eye on the motivations of McLaren and Westwood, punk emerged as an exercise in creative destruction; an aesthetic provocation that translated into lives lived ‘heroically’ amidst the ruins of the twentieth century.125 In between, punk cultivated a DIY ethos committed to opening up channels of independent production that strove either to reimagine the boundaries of popular music or reset them against all that was deemed to have become clichéd and impotent. Rotten, when pushed, retained a more open-ended definition : ‘You can’t put it [punk] into words. It’s a feeling. It’s basically a lot of hooligans doing it the way they want and getting what they want’.126

In many ways, therefore, people could find what they needed in punk. For Sham 69’s Jimmy Pursey, punk was ‘a kid in Glasgow, Liverpool, London, Southampton, who lives in a little grimy industrial estate, wears an old anorak, dirty jeans, pumps, goes out at night, has a game of football on the green, throws a couple of bricks through a window for a bit of cheek, a kick. He likes the things he likes; no fucking about … they’re the kids that THIS was supposed to get over to’.127 Others picked up on punk’s challenge to musical convention, both in terms of sound and lyrical content. Bands such as Scritti Politti and The Pop Group appreciated punk’s innovation and ‘bona fide political fervour’, but sought to extend its relatively limited palette via continued experimentation.128 In other words, they understood punk as a temporal moment that provided the impetus and the processes by which to enable access to new cultural forms and production. Penny Rimbaud (Jeremy Ratter), meanwhile, seized on punk’s anarchic symbolism to conceive a more overtly activist strand of protest linked back to the 1960s counterculture. Rimbaud, who co-founded Crass with Steve Ignorant (Steve Williams) in 1977, recognised punk as ‘an all-out attack on the whole system’.129

As should be clear, punk could infer many things. The debate that rumbled across the letter-pages throughout the short life-span of Punk Lives magazine (1982–83) flitted between those bemoaning the inclusion of certain bands not deemed to be punk and discussion as to the culture’s meaning. But despite sometimes serious division, such as between the anarchist punks inspired by Crass and the more class-orientated punks and skinheads who related to Oi!, what tended to bind the various interpretations together was a sense of difference or opposition to perceived sociocultural norms.130 Most of those involved in or inspired by punk saw it as having either opened up or provided an alternative cultural space through which to operate, escape to or exist in. Punk served as a medium for agency; it stirred people to act. It could, moreover, be used in different ways. Punk could be enjoyed purely for the music, the style and the excuse to play in a band or go to a gig. Simultaneously, British punk’s template – as sketched by the Sex Pistols, The Clash and developed by others thereafter – meant it harboured more serious intent. It provoked, questioned and lent empowerment to those who aligned to it.131 This could mean voicing an opinion or registering a protest; it could also be read in purely cultural terms, as a reaction to prevailing music or stylistic trends. At its most committed, punk pertained to a politicised youth culture that, in the words of Conflict, ‘meant and still means an alternative to all the shit tradition that gets thrown at us. A way of saying No to all the false morals that oppress us. It was and still is the only serious threat to the status quo of the music business. Punk is about making your own rules and doing your own thing.’132

Figure 1.2 Toxic Grafity, 5, 1980.