Introduction

To relinquish a mine site at the cessation of mining proponents need to rehabilitate the site to a standard that the State is willing to (or allow a third party to) accept responsibility for future liability (ICMM 2025; Maybee et al. Reference Maybee, Boggs, Stevens and Scrase2024). Third-party involvement in repurposing projects can reduce proponent costs, mitigate the use of care and maintenance of the site as a stop-gap measure and contribute to rehabilitation and the transitioning the region to a post-mining economy. This article contributes to answering the question ‘what is good mine closure’ (Littleboy et al. Reference Littleboy, Marais and Baumgartl2024) by exploring alternative principles and regulation relating to post-mining land use (‘PMLU’) specifically tenure arrangements that facilitate repurposing projects as a PMLU (Littleboy et al. Reference Littleboy, Marais and Baumgartl2024; Maybee et al. Reference Maybee, Boggs, Stevens and Scrase2024). The rights to the underlying land tenure are key to facilitating PMLU because the responsibility for site liability is usually attached to the land, but a third party proposing a PMLU will need security of tenure. The importance of engaging First Nation custodians as partners in PMLU projects is well recognised (Measham et al. Reference Measham, Walker, Haslam McKenzie, Kirby, Williams, D’Urso, Littleboy, Samper, Rey, Maybee, Brereton and Boggs2024; Bond and Kelly Reference Bond and Kelly2021; UNDRIP). For ease of discussion ‘third-party’ in relation to third-party entrepreneurs seeking to engage in repurposing projects includes First Nation custodians.

Examples of successful repurposing are few, and many sites that may be suitable for repurposing projects languish under care and maintenance, a status that is viewed as a regulatory loophole to avoid the expense and problems associated with rehabilitation (Pepper et al. Reference Pepper, Hughe and Haigh2021; Measham et al. Reference Measham, Walker, Haslam McKenzie, Kirby, Williams, D’Urso, Littleboy, Samper, Rey, Maybee, Brereton and Boggs2024). On this point Pepper et al. (Reference Pepper, Hughe and Haigh2021), note that the State could and should take a more pro-active role to require or facilitate the transition from care and maintenance to PMLU.

The Western Australian (‘WA’) government has taken a pro-active role by introducing of the diversification lease specifically to provide a tenure option that facilitates PMLU. Third-party engagement in repurposing projects can reduce costs for monitoring, maintenance and rehabilitation for the mining company, and contributes to transitioning the region to a post-mining economy. If the diversification lease proves to be an alternative tenure option that can provide First Nation engagement, third-party repurposing projects and address the issue of liability for residual risks (Maybee et al. Reference Maybee, Boggs, Stevens and Scrase2024), it will be instrumental in PMLU planning that facilitates the path to relinquishment and the transition of post-mining economies and environments.

For the purposes of this article Australia and in particular WA is discussed because first, WA mining areas are mostly subject to First Nation land rights, in comparison the Eastern States of Australia where First Nation rights on mined land are often extinguished by the grant of the underlying tenure. In comparison, WA mining developments are commonly on tenure subject to the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (‘NT Act’). Secondly, the WA government has introduced a new type of tenure, the diversification lease that is specifically designed to facilitate repurposing of mine sites by third parties and recognise First Nation rights (Buti Reference Buti2021).

To explore the potential issues the diversification lease tenure is designed to mitigate the author employed a doctrinal methodology by reviewing the current literature, the legislative provisions and related extrinsic materials. While further research is needed to evaluate the efficacy of the diversification lease in practice, on a doctrinal analysis this innovative tenure option has the potential to alleviate issues related to residual risk and facilitate third-party engagement in PMLU projects.

What is tenure?

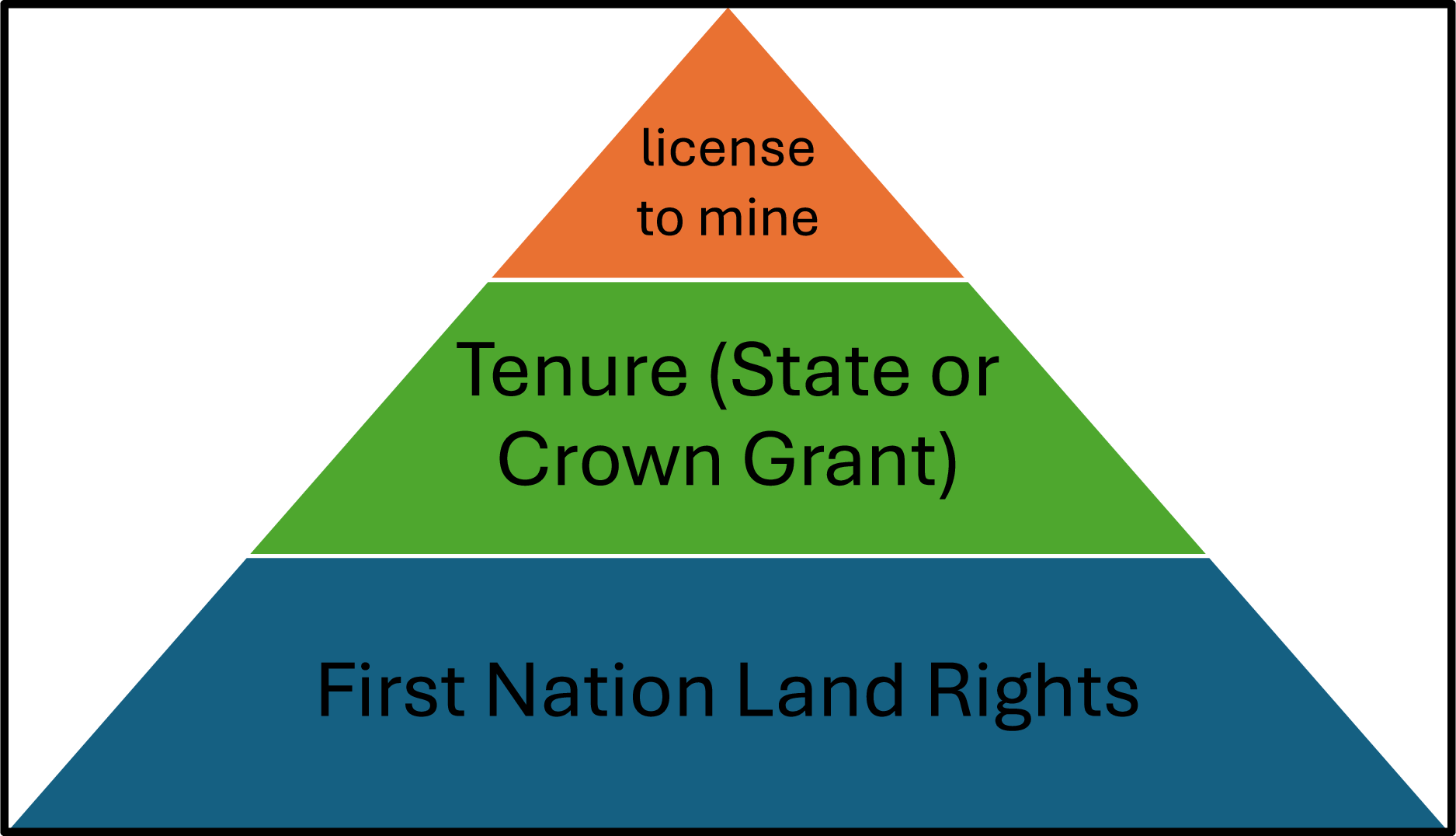

The term tenure refers to all grants of land from the national or State government (in common law countries referred to as Crown grants, from here on ‘State grants’). The rights and restrictions depend on the tenure type. Mining jurisdictions commonly allow mining by providing a licence or permission to remove the resource that applies to the underlying tenure (Figure 1). The mining proponent may, but does not necessarily, hold the underlying tenure, which may belong to the State or a third-party. The tenure may also be subject to rights of First Nation peoples (as is common in Australia and Canada). The issues related to resolving or transferring the attendant liability for risk on the underlying tenure, or restoring the tenure to its pre-mining landform (Maybee et al. Reference Maybee, Boggs, Stevens and Scrase2024; Sanchez and Morrison Reference Sanchez and Morrison-Saunders2025), means that there are very few examples of successful relinquishment globally (IISD 2023; ICMM 2025).

Figure 1. Mining rights, underlying tenure and First Nation rights.

Commonly only the State has absolute ownership of land. State land grants will vary from unconditional to conditional grants. For the purposes of this discussion, I have adopted the common Australian terminology for tenure types. A grant of fee simple tenure is the closest private property grant to absolute ownership. The fee simple tenure is distinguished from other conditional grants because there is no time limit or fixed purpose and there are no restrictions on alienation (inheritance, sale and purchase). In contrast, grants of leases in Australia are conditional grants that are limited by time and sometimes use. In international jurisdictions this type of lease tenure may be referred to as conditional land grants. The last type of tenure is Crown or State land, that is land that is not subject to a State grant of fee simple or lease and is owned by the State (from hereon, ‘State Land’). In most jurisdictions land grants including fee simple type grants do not confer a right to minerals or other natural resources that remain the property of the State.

In general, a mining licence provides the right to remove the minerals that belong to the State from the underlying tenure (Brown Reference Brown2022; DOJPCOa). A mining licence co-exists with the underlying land tenure, and at the cessation of mining the rights of the underlying tenure holder are restored (IISD 2023). Therefore, the default position is that the land will be restored to allow the tenure holder to exercise the underlying tenure’s purpose or rights (Hamblin et al. Reference Hamblin, Gardner and Haigh2022; DMIRS 2023). The purpose of the underlying tenure may restrict the land use and thus may preclude a PMLU that repurposes the site.

In WA mining developments are commonly on leases or State Land subject to NT Act, not fee simple tenure that extinguishes NT Act rights. In comparison, in the Eastern States of Australia First Nation rights to land in mining regions are often extinguished by fee simple State grants.

In Australia, current examples of repurposing projects exist when the mine site is mostly on a fee simple tenure because the mining proponent has purchased the fee simple and can then sell the fee simple (which can include the liability for risk) to a third party for repurposing (SDIP 2018). However, examples of successful repurposing are few. Many sites under care and maintenance that may be suitable for repurposing projects can be inhibited by the underlying tenure restrictions and attendant responsibility for liability.

First nation land rights

The importance of First Nation rights, participation and partnership, and free, prior, informed consent, in the mining and PMLU context is well recognised (Thierry et al. Reference Thierry, Theriault, Keeling, Bouard and Taylor2024; Bond and Kelly Reference Bond and Kelly2021; UNDRIP). However, the late legal recognition of First Nation land rights in Australia can limit recognition and thus participation in PMLU. The pre-existing rights of the First Nation Australians were not recognised until 1992 in the landmark Australian High Court case of Mabo v Queensland (No 2) (‘Mabo’) (ANTaR 2022). The principles of Mabo were embodied in the NT Act.

In Australia mining and land tenure are managed and regulated by the States as part of a federated system of government. The Australian Commonwealth Constitution provides that Commonwealth Laws prevail over all State legislation (FRLb). Consequently, the NT Act prevails over all State mining and land laws. The Commonwealth Constitution does not confer jurisdiction for land tenure or minerals that jurisdiction remains with the States (see section 51) (FLRa). Therefore, the NT Act could not provide for grants of State lands (see section 223) (FLRb).

The engagement of the NT Act and the attendant rights of First Nation Australians in the mining context will depend on the time of the mining development commenced. In general, developments post 1994 (the commencement date of the NT Act) will be ‘future acts’ that engage the NT Act provisions (see sections 24AA, 24IC) (FLRb). A future act will require the proponent to negotiate with the rights holders and enter into an Indigenous Land Use Agreement (‘ILUA’) which can include a Mine Participation Agreement (‘MPA’). Similar agreements (Impact and Benefit Agreements) exist in Canada’s mining industry (Thierry et al. Reference Thierry, Theriault, Keeling, Bouard and Taylor2024). However, there is a lack of clarity about how these instruments support and facilitate First Nation engagement in the post-mining context, particularly when mines are left in care and maintenance – there is a real risk that un-remediated and unusable land becomes the responsibility of First Nation custodians (Bond and Kelly Reference Bond and Kelly2021; Thierry et al. Reference Thierry, Theriault, Keeling, Bouard and Taylor2024).

Further, exacerbating this risk in Australia is the cessation of mining on land that is not subject to an ILUA or MPA. Until 2014, it was assumed that mining rights prior to 1994 even though operating on non-exclusive tenure (such as leases, or State land) that had permanently altered the landscape, for example by creating mine-voids, had extinguished Native Title rights. However, the High Court determined that pre-1994 mining rights although exempted from the NT Act while operating, did not extinguish Native Title rights it merely suspended them, even when the land was significantly disturbed by pits and infrastructure (HCA 2014). In other words, when the mining operation ceases, and the land reverts to the State or underlying tenure holder the suspended Native Title rights will resurface with full force. These mined lands will not have the protection of an ILUA or MPA so the risk to First Nations custodians, identified by Bond and Kelly (Reference Bond and Kelly2021), is even greater.

Tenure arrangements by the States to recognise First Nation rights and facilitate First Nation inclusion are not straightforward, and do not always reflect the values of the rights holders. The diversification lease tenure may provide alternative options for First Nation’s peoples to engage and exercise rights in the PMLU context. The diversification lease does not disturb Native Title rights and requires the approval under the NT Act before the DPLH will consider granting the lease (DPLH 2023).

Western Australian land tenure options

In 2023, WA the parliament amended the Land Administration 1997 (WA) (‘Land Act’) (DOJPCOb) to include a diversification lease tenure designed to resolve the issues of land use restrictions. The diversification lease has two key features. The tenure is not exclusive, so it co-exists with other rights such as mining licences, and rights under the NT Act. Further, it does not restrict land uses and can excise any portion of the existing tenure. The diversification lease could potentially transform PMLU by providing an alternative tenure option for repurposing projects that engage third-party entrepreneurs.

This section explains the Land Act provisions in relation to mining and the distinctions between the diversification lease and other tenure options. Mining is deemed the dominant land use because the Land Act is subject to the rights conferred under the Mining Act 1978 (WA) (‘Mining Act 1978’) (DOJPCOa).

Prior to the 2023 amendments, the lease titles available under the Land Act were pastoral leases, general leases (DPLH 2021) and section 83 leases for the purpose of advancing the interests of First Nations’ peoples (DOJPCOb). The diversification lease incorporates aspects of the pastoral and general leases. The diversification lease is distinct from pastoral and general leases because it allows for diverse uses (like a general lease) and is non-exclusive (like a pastoral lease), so can facilitate repurposing projects on State land or pastoral leases (Buti Reference Buti2021).

First Nation custodians may receive some degree of perpetual rights pursuant to a State reserve that holds land in the public interest under the Land Act Part IV. Once created the care and control of the reserve can be conferred by a section 46 management order on the First Nation prescribed body corporate. First Nation custodians have negotiated this type of reserve tenure arrangement that allows for perpetuity rather than section 83 leases of a fixed duration. For example, The Land Administration (South West Native Title Settlement) Act 2016 (WA) provided this type of tenure as part of the Southwest Native Title Settlement (SWALC). However, this tenure arrangement (even when the management body can potentially grant leases or licences) does not address residual risks associated with mine sites because it requires the relinquishment.

Under section 79, general lease tenure is designed for small scale intensive uses (DOJPCOb). The grant allows for exclusive occupation rights, the Minister decides the duration of the lease and conditions can include an option to purchase the land in fee simple (freehold tenure) (DPLH 2021). The exclusive nature of the general lease interferes with Native Title rights and precludes the co-existence of mining licences.

Section 93 pastoral leases are not exclusive – the tenure co-exists with mining licences and NT Act rights (DOJPCOb). However, the use is restricted to the grazing of stock and associated agriculture such as growing feed. Under sections 91, 119 – 122A, the lessee may apply for a permit for additional land uses such as tourism or a non-pastoral agriculture (DOJPCOb), but non-pastoral agriculture must still be ‘reasonably’ related to the pastoral use, and a tourism activity must be pastoral based tourism (DPLH 2021). For example, WA has many pastoral leases that are used for carbon sequestration or farming, however, to comply with the Land Act, the lease must still prioritise grazing, so these projects need to run some livestock even though the primary purpose is carbon farming (Hansard 2023). The diversification lease tenure would prevent the need for the artifice of grazing stock principally to satisfy the legislative requirements.

The reason for the introduction of a new diversification lease tenure, rather than a revision and amendment of the pastoral lease use provisions, is that the latter action would have engaged the NT Act future act provisions at a State level (Hansard 2023). That is, a State wide ILUA requiring the consent of all Native Title holders and claimants would be necessary. A diversification lease grant is subject to the NT Act, but rights can be negotiated on a case-by-case basis, prior to the approval of a lease application (Hansard 2023).

Residual and unforeseen risks

Relinquishment is a key goal of mining proponents, however, releasing the mining proponent from future liability is a significant hurdle in the current framework (ICMM 2025; Hamblin et al. Reference Hamblin, Gardner and Haigh2022; Maybee et al. Reference Maybee, Boggs, Stevens and Scrase2024). In WA, a mine site can be legally abandoned by forfeiture, licence surrender or expiration, the mining proponent will not be necessarily be released from liability for the site because liability can be imposed by environmental protection and contaminated sites legislation (Brown Reference Brown2022; Hamblin et al. Reference Hamblin, Gardner and Haigh2022), or the Mining Act 1978 s 116B. In addition, proponents with sites that cannot be rehabilitated to the pre-mining land use may designate the site as in care and maintenance (Measham et al. Reference Measham, Walker, Haslam McKenzie, Kirby, Williams, D’Urso, Littleboy, Samper, Rey, Maybee, Brereton and Boggs2024; Pepper et al. Reference Pepper, Hughe and Haigh2021). In WA, care and maintenance is managed under the Work Health and Safety Regulations (WA) regulation 675UH.

In general, on relinquishment, the underlying tenure holder will assume responsibility for future liability. The State, the mining proponent, or a third party may hold the underlying tenure. For example, acid mine drainage (‘AMD’) can be an issue for mine-voids, and management and rehabilitation of AMD can be particularly problematic for voids created before AMD management became customary practice (Brown Reference Brown2022). The State authorities are reticent to accept responsibility or approve proposals that transfer tenure to a third party (Beer et al. Reference Beer, Haslam-McKenzie, Weller, Davies, Cote, Ziemsk, Holmes and Keenan2022). Consequently, relinquishment standards are rarely achieved (ICMM 2025; Measham et al. Reference Measham, Walker, Haslam McKenzie, Kirby, Williams, D’Urso, Littleboy, Samper, Rey, Maybee, Brereton and Boggs2024).

So, can the diversification lease provide for greater integration of repurposing projects as a PMLU and contribute to the relinquishment process?

The diversification lease tenure option has the potential to facilitate third-party repurposing projects that contribute to rehabilitation but not necessarily relieve the mining proponent from liability. Projects that repurpose mine-sites are not a ‘quick-fix’ and should be considered transitions that contribute to the proponents’ relinquishment in the long-term. The proponent, the tenure holder and the third party will need to consider division or partition of liability (Maybee et al. Reference Maybee, Boggs, Stevens and Scrase2024). For example, the proponent miner will not wish to be liable for a third-party project that inadvertently exacerbates the existing rehabilitation issue or creates new risks. Similarly, the third party should not be liable for risks created by the mining project.

Mining cessation: care and maintenance or PMLU?

A mine may be subject to mine closure planning under the State’s mining legislation or conditions imposed by Environmental protection legislation, or other Acts regulating aspects such as site contamination (Brown Reference Brown2022; Hamblin et al. Reference Hamblin, Gardner and Haigh2022).

Open pit mining creates high impact site disturbance so achieving relinquishment by returning the site to suit the purpose of its underlying tenure such as pastoral (the default position) can be impossible. Rehabilitation of older mines that commenced and ceased mining without closure planning can present expensive problems, which may result in the proponent placing the mine site into care and maintenance as a stop-gap measure (Hamblin et al. Reference Hamblin, Gardner and Haigh2022; Measham et al. Reference Measham, Walker, Haslam McKenzie, Kirby, Williams, D’Urso, Littleboy, Samper, Rey, Maybee, Brereton and Boggs2024; Pepper et al. Reference Pepper, Hughe and Haigh2021). This ensures the safety of the site but does not progress the site rehabilitation and thus the goal of relinquishment.

At the cessation of mining the rehabilitation or repurposing of the site can be avoided by placing the site in care and maintenance (Measham et al. Reference Measham, Walker, Haslam McKenzie, Kirby, Williams, D’Urso, Littleboy, Samper, Rey, Maybee, Brereton and Boggs2024). The care and maintenance option is viewed as a regulatory gap in Australian jurisdictions because there is no trigger mechanism to enforce the transition from care and maintenance to rehabilitation (Pepper et al. Reference Pepper, Hughe and Haigh2021). However, there are also examples of the mining proponent, First Nation custodians, third-parties and stakeholders, seeking to engage with repurposing projects and the underlying tenure is the obstacle that needs to be overcome to progress the project (Beer et al. Reference Beer, Haslam-McKenzie, Weller, Davies, Cote, Ziemsk, Holmes and Keenan2022).

The WA Iluka Resources Ltd (‘Iluka’) mine site is a potential candidate for a successful diversification lease application. The Department of Biodiversity, Conservations and Attractions (WA) (‘DBCA’) holds the underlying tenure of the State land portion of the site (Beer et al. Reference Beer, Haslam-McKenzie, Weller, Davies, Cote, Ziemsk, Holmes and Keenan2022). The site mine-voids successfully transitioned into a wetland, however, the site has ongoing rehabilitation requirements, such as AMD monitoring and remediation. FAWNA Incorporated (Inc) (‘FAWNA’), a not-for-profit wildlife rescue organisation, is seeking tenure over 300 hectares of the site to establish a wildlife hospital and biodiversity park (the Kaatijinup Biodiversity Park (‘KBP’)) (Hamblin et al. Reference Hamblin, Gardner and Haigh2022). The Shire of Capel is keen for the project to progress, and the Wardandi peoples, the First Nation custodians of the site, have an interest in the conservation and the management of the KBP (Beer et al. Reference Beer, Haslam-McKenzie, Weller, Davies, Cote, Ziemsk, Holmes and Keenan2022).

The DBCA is reluctant to transfer tenure to FAWNA without certainty that the rehabilitation measures are sustainable in the long-term because of the liability issues (Hamblin et al. Reference Hamblin, Gardner and Haigh2022). Iluka has proposed a ‘progressive land-use transition’ (Hamblin et al. Reference Hamblin, Gardner and Haigh2022). Iluka would remain responsible for achieving rehabilitation over the long term while allowing FAWNA the beneficial use and management (Hamblin et al. Reference Hamblin, Gardner and Haigh2022). The DBCA would consider an arrangement that guarantees Iluka’s obligations endure while the FAWNA implements the project as part of the site’s rehabilitation process (Beer et al. Reference Beer, Haslam-McKenzie, Weller, Davies, Cote, Ziemsk, Holmes and Keenan2022). If this arrangement could be achieved, it would turn the site into an asset instead of a liability (Hamblin et al. Reference Hamblin, Gardner and Haigh2022), relieve Iluka of immediate management, but not impose liability on the DBCA or FAWNA, thus addressing the risk and liability issue (Maybee et al. Reference Maybee, Boggs, Stevens and Scrase2024).

The diversification lease may provide the tenure solution to achieve this outcome because the tenure is not exclusive – therefore, does not require relinquishment prior to the change in tenure, and allows the diversified use and excision of the proposed site. A successful diversification lease tenure model for the KBP could pave the way for future repurposing projects.

Conclusion

While further research is required to assess the practical efficacy of the diversification lease in the PMLU context, on paper the diversification lease tenure addresses the limitations of the existing tenure options because it allows for excision of a specific site, multiple purposes, multiple sub-lessees and is non-exclusive (Hansard 2023). The non-exclusive nature of lease does not affect First Nation rights and allows for the continuation of the mining rights and obligations while allowing a third-party to engage in PMLU. In short, the tenure can provide for earlier transitions to PMLU and alternative economies as part of a mine closure plan, because it can be granted prior to relinquishment, or provide an option that allows for the partitioning of residual risk by excising a portion of the site (Maybee et al. Reference Maybee, Boggs, Stevens and Scrase2024). This tenure arrangement may not only facilitate individual projects on isolated sites but also regional plans for areas of higher density mining that require cumulative impact management, such as the Pilbara Energy Transition (PET 2025). Future research should compare alternative tenure arrangements in Australian and international jurisdictions and consider whether this type of tenure would encourage engagement with PMLU alternatives and mitigate the use of long-term care and maintenance to avoid rehabilitation obligations. Once the facility of this tenure is explored in practice it may well provide part of the solution to facilitate repurposing projects in Australian and international jurisdictions by making third-party repurposing a realistic and attractive alternative to care and maintenance.

Data availability statement

Data availability is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Acknowledgements

The research for this paper was supported by the University of Western Australia research sabbatical program.

Author contributions

Dr Natalie Brown is the sole author of this paper.

Financial support

This paper was not funded

Competing interests

The author declares there is not conflict of interest

Ethics statement

Ethics approval and consent are not relevant to this article type

Comments

No accompanying comment.