Introduction

The Tutti Frutti Pumice sequence is the result of one of the seven most significant Plinian eruptions of the Popocatépetl volcano (located 30 km W-NW of the Pelagatos volcano), dated using 14C on ash and charcoal materials, yielding an age of 14.1 ka BP (∼17 ka cal BP) (Sosa-Ceballos et al. Reference Sosa-Ceballos, Gardner, Siebe and Macías2012).

Furthermore, a radiometric age was obtained using 14C on charred material from soil mixed with fragments of Pelagatos eruptive flow (reworked) of 25.2 ± 0.1 ka BP (Agustín-Flores et al. Reference Agustín-Flores, Siebe and Guilbaud2011). As the Tutti Frutti Pumice and the paleosol are found above and below the volcanic deposit, respectively, it is assumed that the maximum age of the volcano is 14.1 ka BP, with a minimum of 2.5 ± 0.1 ka BP (Guilbaud et al. Reference Guilbaud, Siebe and Agustín-Flores2009).

This same technique has been employed in dating other monogenetic volcanoes in the SCVF, such as Xitle (1.7 ± 0.1 ka BP), Tláloc (6.2 ± 0.9 ka BP), Cuauhtzin (2.8 ± 0.1 ka BP), Hijo del Cuauhtzin (20.9 ± 0.3 ka BP), Teuhtli (older than 14.00 ka BP), Ocusacayo (21.7 ± 0.2 ka BP), among others, using organic samples, particularly from paleosol charcoal, as well as blocks and volcanic ash deposits (Siebe et al. Reference Siebe, Rodríguez-Lara, Schaaf and Abrams2004, Reference Siebe, Arana-Salinas and Abrams2005).

Only thirteen out of over two hundred volcanic cones in the SCVF have been dated with acceptable precision. These records show that the recurrence interval for monogenetic eruptions in the central part of the SCVF and near Mexico City is <2500 years. When considering the entire SCVF, the recurrence interval is <1700 years. It is crucial to increase the number of datings as this allows for a comprehensive understanding of the volcanic behavior in the area for risk prevention purposes (Siebe et al. Reference Siebe, Rodríguez-Lara, Schaaf and Abrams2004).

The geochronology of volcanoes using 14C requires organic materials typically not found in volcanic products. Therefore, confirming eruption ages necessitates other radioisotopes, such as 10Be. 10Be is a cosmogenic isotope with a half-life of 1.389 ± 0.014 Ma. 10Be is formed due to cosmic ray interactions with the Earth’s atmosphere, leading to spallation and the production of thermal neutrons capable of transmuting oxygen and nitrogen nuclei (meteoric 10Be). Additionally, it is produced by the transmutation of oxygen or silicon nuclei on the Earth’s surface (“in situ” 10Be). In inorganic mineral networks exposed to cosmic rays, the so-called in situ 10Be is generated due to exposure to subatomic particles also resulting from cosmic ray spallation (Berggren et al. Reference Berggren, Beer, Possnert, Aldahan, Kubik, Christl, Johnsen, Abreu and Vinther2009; Graly et al. Reference Graly, Reusser and Bierman2011; Bierman et al. Reference Bierman, Bender, Christ, Corbett, Halsted, Portenga and Schmidt2020).

In situ 10Be is predominantly measured in quartz (SiO2) for several reasons: it is a common mineral in terrestrial materials; its chemical composition is simple, making the nuclide production rates independent of mineral composition; it is resistant to weathering, and its covalent lattice does not react or exchange ions with the surroundings (Bierman et al. Reference Bierman, Bender, Christ, Corbett, Halsted, Portenga and Schmidt2020).

The measurement of 10Be through accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) was first proposed and carried out between 1977 and 1978 (Raisbeck et al. Reference Raisbeck, Yiou, Fruneau, Lieuvin and Loiseaux1978). This analytical technique is highly sensitive (up to one part in 10–15). It employs negative ions, multiple acceleration stages, and filters to separate ions of similar mass, ultimately measuring the isotopic ratio in a sample (Scognamiglio et al. Reference Scognamiglio, Chamizo, López-Gutiérrez, Müller, Padilla, Santos, López-Lora, Vivo-Vilches and García-León2016).

The use of AMS allows the elimination of molecular and atomic isobaric interferences, owing to the high energy of the particles that enable the use of nuclear-type detection systems. Another significant advantage is the minimal amount (micrograms) of the analyte required for measurement (Padilla Domínguez Reference Padilla Domínguez2015; Scognamiglio et al. Reference Scognamiglio, Chamizo, López-Gutiérrez, Müller, Padilla, Santos, López-Lora, Vivo-Vilches and García-León2016).

The 10Be has been widely employed for dating the surface exposure of rocks and sediments, estimating erosion, weathering rates, and determining the deposition or burial of sediments. Its use has transformed geomorphology and Quaternary geology, enabling the dating of landforms and measuring denudation rates on soil formation timescales (Granger et al. Reference Granger, Lifton and Willenbring2013).

The in situ 10Be content in quartz is valuable for the geochronology of rocks and landforms that were created or first exposed rapidly (e.g., lava flows, glacial moraines, landslides, glacier-polished bedrock, or river terraces) and have been continuously exposed to incident cosmic rays at the Earth’s surface. The only requirements for its use are that the topography to be dated corresponds to an event of erosion, deposition, or eruptive activity; the surface has been preserved intact with little or no erosion, and the exposure age of the surface is less than several half-lives of 10Be (Goehring et al. Reference Goehring, Brook, Linge, Raisbeck and Yiou2008; Granger et al. Reference Granger, Lifton and Willenbring2013).

The half-life of 10Be allows for the analysis of samples from environments spanning the entire Quaternary (Balco et al. Reference Balco, Briner, Finkel, Rayburn, Ridge and Schaefer2009; Heineke et al. Reference Heineke, Niedermann, Hetzel and Akyl2016; Jouzel et al. Reference Jouzel, Raisbeck, Benoist, Yiou, Lorius, Raynaud, Petit, Barkov, Korotkevitch and Kotlyakov1989; Young et al. Reference Young, Schaefer, Briner and Goehring2013). Dating Pliocene samples is also possible but becomes challenging for the early Pliocene setting when 10Be approaches saturation (Novello et al. n.d., Reference Novello, Lebatard, Moussa, Barboni, Sylvestre, Bourlès, Paillès, Buchet, Decarreau, Duringer, Ghienne, Maley, Mazur, Roquin, Schuster and Vignaud2015; Šujan et al. Reference Šujan, Braucher, Kováč, Bourlès, Rybár, Guillou and Hudáčková2016). A review by Granger (Granger et al. Reference Granger, Lifton and Willenbring2013) indicates that 10Be SLHL (sea-level high-latitude) models arbitrarily referenced to a sea-level location and at a high latitude (>60°) exhibit production rate ranging between 3.7 and 4.3 g–1 yr–1.

The production of 10Be in quartz in the upper 50 cm of the lithosphere primarily occurs through transmutation reactions of O and Si by cosmic rays incident on the Earth’s surface. The olivine ((Mg,Fe)2SiO4) has been used as an alternative to quartz because, in addition to Mg, Fe, and Al, it also contains O and Si in its crystal lattice (Leland 2001; Nishiizumi Reference Nishiizumi1989). The simple chemical composition of olivine allowed us to derive composition-dependent isotopic production rates from calibrations conducted on quartz (Nishiizumi et al. Reference Nishiizumi, Klein, Middleton and Craig1990). A recent study by Carracedo (Carracedo et al. Reference Carracedo, Rodés and Stuart2019) has precisely developed the process for extracting and measuring 10Be from olivine.

Methodology

Samples

Pelagatos volcano consists of basaltic andesites containing a matrix of olivine, clinopyroxene, and orthopyroxene, with plagioclase microlites, oxides, and glass. According to Guilbaud et al. (Reference Guilbaud, Siebe and Agustín-Flores2009), the abundance of olivine in the Pelagatos volcano rocks is about 10 % (volume) with mainly euhedral and anhedral structures.

Five rock samples from the Pelagatos volcano, weighing approximately 1–1.5 kg, were randomly collected. These samples exhibited low weathering signals and, most importantly, clear olivine presence (two from flow 1 and three from flow 2) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Lava flows of the two eruptive events of Pelagatos Volcano, according to Guilbaud (Guilbaud et al. Reference Guilbaud, Siebe and Agustín-Flores2009), and identification of the sampling points of the analyzed rocks.

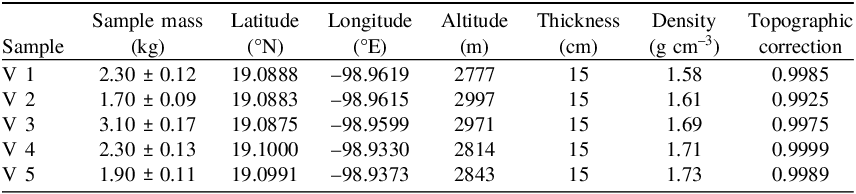

Each sample’s latitude, altitude, thickness, and density were recorded (Table 1). The rock samples were crushed using a hydraulic press and sieved at the Grinding Laboratory of the Institute of Geophysics, UNAM. For olivine crystal extraction, the sieved fraction of 80–100 μm from each sample was passed through a Frantz LFC-2 magnetic separator at the Mineral Separation Laboratory of the Institute of Geophysics, UNAM, with a 15° frontal angle and a current variation of 0.01–0.05 A.

Table 1. Information on the Pelagatos Volcano rock sampling points

Elemental characterization of olivine was conducted using X-ray diffraction (XRD) and scanning electron microscopy with energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDS) to assess the efficiency of olivine extraction in samples with and without mineral extraction. This characterization was also aimed at obtaining the proportions of Mg, Fe, Si and O in the mineral crystals. Chemical treatment of the samples took place at the Cosmogenic Isotope Laboratory of the Institute of Physics, UNAM.

Approximately 1 g of olivine was taken from each sample (plus two blanks), following the procedure proposed by Carracedo et al. (Reference Carracedo, Rodés and Stuart2019), Nishiizumi (Reference Nishiizumi1989), and Nishiizumi et al. (Reference Nishiizumi, Klein, Fink, Middleton, Kubic, Sharma and Arnold1990). Each olivine sample underwent a meteoric 10Be removal process in an ultrasonic bath using HF at 40% and HCl 1M. This step was repeated several times until mass losses exceeded 30%. Purified samples from the meteoric fraction was traced with 9Be carrier (Be4O(C2H3O2)6) standard, 1000 mg L–1 in 2% HNO3 from Merck and underwent an open-system digestion process with 1 mL of HF at 40% and 5 mL of HNO3 at 70%, both Supra Pure quality.

Dissolved samples were transferred to a separation funnel, to which 2 mL of EDTA solution (10%), 2.5 g of NaCl, and 1 mL of acetylacetone (5%) (Tabushi Reference Tabushi1958) were added. The pH was adjusted to 7–8 and diluted with 50 mL of water. Subsequently, beryllium acetylacetonate was re-extracted by adding 10 + 5 + 5 mL of CCl4 and keeping it stirring. The aqueous phases separated from the three washes of each sample were dried. The precipitates were recovered with 3 mL of HCL 9M. They underwent ion exchange for the isolation and purification of Be using ion exchange resins (Dowex AG1-X8 and Dowex 50W-X8 100–200 mesh, respectively), following the Padilla procedure (Padilla et al. Reference Padilla, López-Gutiérrez, Sampath, Boski, Nieto and García-León2018). The purified Be fractions were precipitated at pH = 10 as Be(OH)2 by adding ammonia, followed by centrifugation at 4000 rpm for 10 min. The precipitates were lyophilized for 24 hr, then calcined at 850°C for 3 hr to obtain BeO; after that, they were mixed with 4 mg of Nb from Alfa Aesar. This mixture was pressed into aluminum cathodes for measurement using the AMS equipment.

AMS analysis

The samples were measured in the 1 MV AMS system at the National Laboratory of Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (LEMA) as described by Solís (Solís et al. Reference Solís, Chávez-Lomelí, Ortiz, Huerta, Andrade and Barrios2014). The negative ion beam is produced in a Cs ion source and injected into a magnetic filter where ions are mass-analyzed and separated in the low-energy zone. These ions are accelerated in a 1 MV Tandetron accelerator using Ar gas for the stripping process. The masses of the species from the accelerator were analyzed in a second magnetic filter, and their energy was measured in an electrostatic analyzer (ESA) in the high-energy zone. In this same zone, 10Be is separated from its stable isobar, 10B, using a 75 nm thick silicon nitride membrane (Calvo et al. Reference Calvo, Santos, López-Gutiérrez, Padilla, García-León, Heinemeier, Schnabel and Scognamiglio2015; Scognamiglio Reference Scognamiglio2017).

The measurement of 10Be was carried out in the +1-charge state after the accelerator. The 10B isobar was separated using a silicon nitride degrader foil with thicknesses of 75 nm placed behind the high energy sector magnet. The complete description of the system tuning is detailed by (De Los Rios et al. Reference De Los Rios, Méndez-Garcia, Padilla, Solis, Chávez, Huerta and Acosta2018). The average currents obtained in the measurements in the high-energy zone were around 1 μA. The measured 10Be/9Be isotopic ratios were normalized to the 07KNSTD standard, with a nominal ratio of 2.71 × 10−11 (Nishiizumi et al. Reference Nishiizumi, Imamura, Caffee, Southon, Finkel and McAninch2007).

Exposure age calculation

The exposure ages of 10Be were calculated using the online exposure age calculator formerly known as the CRONUS-Earth v3 exposure age calculator (Exposure age calculator v3: calculate ages (washington.edu)), which employs cosmogenic nuclide production rates determined at various primary calibration sites for quartz (Balco et al. Reference Balco, Stone, Lifton and Dunai2008; Lal Reference Lal1991; Stone Reference Stone2000). The calculations are based on the “St” time-independent scale (Stone Reference Stone2000) in combination with the ERA40 atmospheric model and the global default SLHL spallation production rate of 10Be inferred from the ICE-D production rate database. Shielding factors were calculated using the Topographic Shielding Calculator v1.0 provided by the CRONUS-Earth Project (Borchers et al. Reference Borchers, Marrero, Balco, Caffee, Goehring, Lifton, Nishiizumi, Phillips, Schaefer and Stone2016). Considering the good conservation status of the sampled surfaces, no erosion corrections were applied. Likewise, given that there have been no snowfall events in the area in recent years, it is assumed that snowfall infliction on production rates is negligible. Topographic correction takes into account the shielding of cosmic rays by the surrounding terrain, which means a reduction in the production of 10Be. This is important because it can overestimate exposure ages

The correction for olivine mineral was adjusted based on its composition using Equation 1, based on the theoretical model of Reedy-Arnold (Masarik et al. Reference Masarik, Kim and Reedy2007; Nishiizumi et al. Reference Nishiizumi, Klein, Middleton and Craig1990).

Where, O, Mg, Si and Fe concentrations are given in percent, and Pquartz values were estimated based on measured 10Be concentrations and scaled according to latitude and elevation for each sample (Table 4), using the scaling factors of Lal (Reference Lal1991)/Stone (Reference Stone2000) and following the scheme implemented by Balco et al. Reference Balco, Stone, Lifton and Dunai2008).

To quantify the relative difference in production between olivine and quartz, we define a scaling factor R as the ratio of production rates (Eq. 2).

Rearranging this expression allows us to estimate the 10Be production rate in olivine directly from the known quartz production rate (Eq. 3).

This relation is essential for correcting quartz-based exposure age models to account for the specific elemental composition of olivine. The correction assumes similar contributions from muogenic and spallogenic components, and while minor differences may remain due to muon interactions, the approximation is considered sufficiently accurate for surface exposure dating.

Results

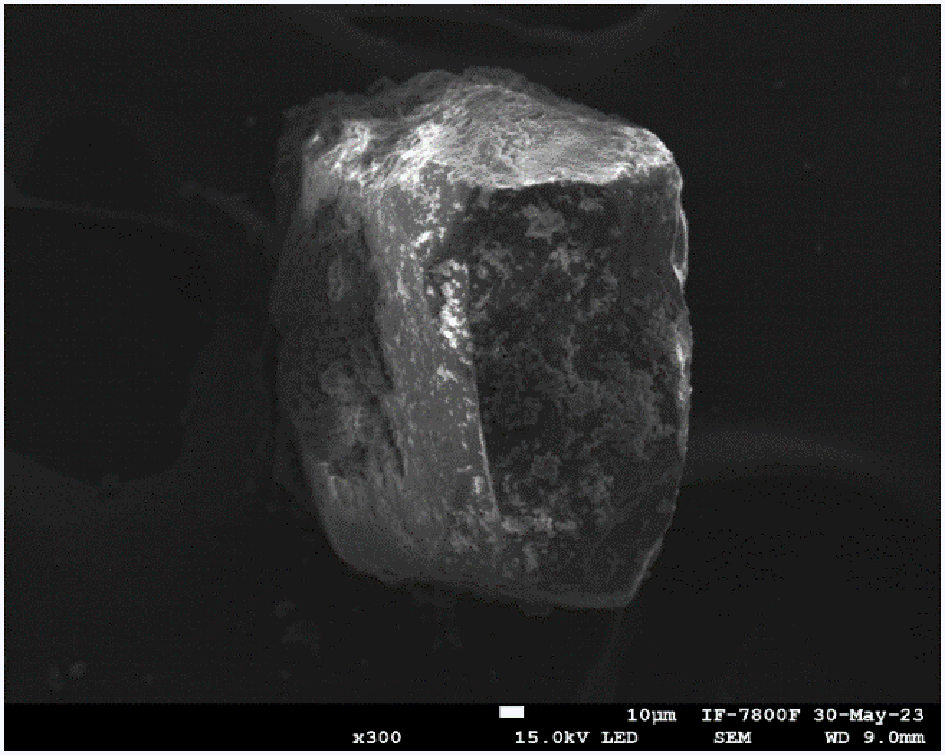

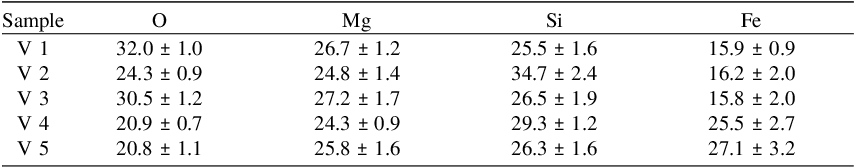

Scanning electron microscopy and X-ray diffraction analyses provided favorable results regarding the characteristic composition of olivine crystals, confirming the high purity of the mineral in all samples and validating the success of the physical separation process. Scanning Electron Microscopy images exhibited the characteristic shape of an olivine crystal with its c-axis in the vertical position (Figure 2). Elemental analysis confirmed that the chemical composition (%) corresponds to the typical olivine composition (Table 2).

Figure 2. SEM image of an olivine crystal

Table 2. SEM-EDS elemental composition results

X-ray diffraction confirmed the olivine composition. Figure 3 compares two samples before and after chemical processing. Although the presence of only olivine post-processing indicates effective removal of other phases, we cannot entirely exclude minor losses of olivine during acid leaching. The final mineralogical composition corresponds to forsterite, as confirmed by its high magnesium content.

Figure 3. XRD pattern for sample V2* before chemical cleaning (V2*) and (V4+) after chemical cleaning.

10 Be Concentrations

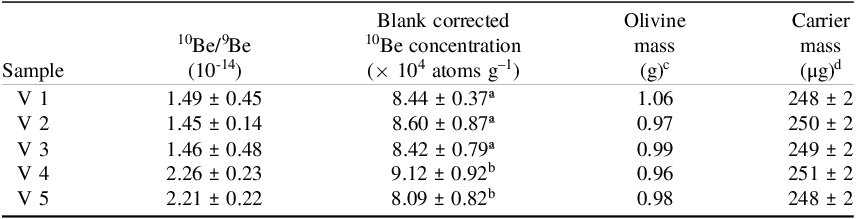

The ratios of 10Be/9Be and concentrations of 10Be in olivine samples from Pelagatos volcano rocks are shown in Table 3. The 10Be/9Be ratios of the samples were normalized to the standard with a value of 2.71 × 10–11 and then corrected by subtracting the blank value. The uncertainties in the measured 10Be/9Be ratios correspond to the analytical errors reported by the AMS system, which include counting statistics and normalization to the standard. In contrast, uncertainties in the blank corrected 10Be concentrations were obtained by error propagation, taking into account the uncertainties in the 10Be/9Be ratio, the amount of 9Be carrier added, the sample mass, and the chemical blank. All uncertainties are reported at the 1σ level.

Table 3. Analytical data of 10Be in olivine rocks from Pelagatos volcano

a Corrected concentrations based on background10Be/9Be ratio of (9.50 ± 4.47) ×10−15 (9Be carrier mass = 250 µg).

b Corrected concentrations based on background10Be/9Be ratio of (1.73 ± 0.55) × 10−14 (9Be carrier mass = 250 µg).

c Masses were measured using a RADWAG AS 220.X2 analytical balance with a readability of ±0.1 mg. This value is taken as the uncertainty for all individual measurements.

d Beryllium-9 carrier concentration = 1000 ± 10 ppm.

The 10Be/9Be ratios of the samples were approximately twice that of the chemical blank (Table 3), suggesting that a larger quantity of olivine may be necessary in future studies to ensure a more significant recovery of the extracted 10Be, thereby reducing uncertainties in these ratios, which ranged from 10 to 30%. The average concentration of 10Be in Pelagatos volcano rocks was 8.65 ± 0.75 × 104 atoms g–1.

Exposure ages

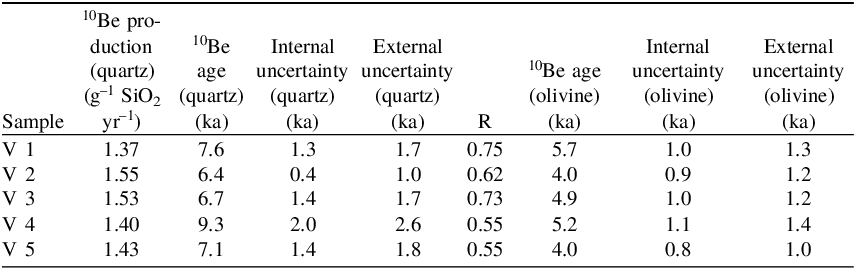

Table 4 presents the exposure ages based on the selected parameters for 10Be production used in the CRONUS EARTH exposure age calculator, without correction factors and with internal uncertainties (1σ representing only analytical errors) and external uncertainties (including those arising from 10Be production rates). Internal uncertainty is suitable for comparing samples with similar production conditions, whereas external uncertainty should be used when comparing with independent dating methods (Alcalá-Reygosa et al. Reference Alcalá-Reygosa, Arce, Schimmelpfennig, Salinas, Rodríguez, Léanni, Aumaître, Bourlès and Keddadouche2018). Thus, a noticeable difference is observed between the previously reported ages and those in this analysis, where the average exposure age in quartz is 7.4 ± 0.9 ka, representing 50% of the age calculated with 14C.

Table 4. Exposure ages of rocks from Pelagatos volcano using CRONUS EARTH, considering the concentration of 10Be produced in quartz (quartz) and correcting for the corresponding quotient in olivine (olivine)

Upon correction with the corresponding ratio in the production of quartz and olivine, this ratio is found to range between 55 and 75%, and the corrected ages in olivine range between 3.9 ± 0.1 and 5.7 ± 1.4 ka, with an average age of 4.7 ± 0.8 ka. They indicate a difference of approximately 9.4 ka less than the dates observed in the tutti-frutti pumice of 14.1 ka (∼17 ka cal. BP) (Guilbaud et al. Reference Guilbaud, Siebe and Agustín-Flores2009; Sosa-Ceballos et al. Reference Sosa-Ceballos, Gardner, Siebe and Macías2012), and over 2.2 ka from the reported upper paleosol age following the eruption with 2.5 ± 0.1 ka (Guilbaud et al. Reference Guilbaud, Siebe and Agustín-Flores2009).

Exposure ages in volcanic flow 1 ranged from 3.9 ± 0.8 ka to 5.2 ± 1.1 ka, showing a difference of 1.2 ka between them with an average age of 4.6 ± 0.9 ka.

Regarding volcanic flow 2, exposure ages were found to range between 4.0 ± 1.2 ka and 5.7 ± 1.0 ka, with a mean of 4.9 ± 0.9 ka.

Analytical uncertainties of the order of 20% are due to the relatively young ages and small amounts of olivine used for the analysis, resulting in low measured 10Be/9Be isotope ratios that barely double the value of the chemical blank (Table 3).

These uncertainties could be reduced by extracting 10Be from a larger amount of olivine.

Within the uncertainties, the exposure ages of 10Be in olivine from the Pelagatos volcano are not significantly different.

Discussion

The average exposure ages for each lava flow indicate that the flows associated with the formation of the Pelagatos volcano (Figure 1) occurred between 4.0 ± 0.8 ka and 5.2 ± 1.1 ka for the earlier phase (flow 1) and between 4.0 ± 0.9 ka and 5.7 ± 1.0 ka for the later phase (flow 2). Regardless of the flow from which the samples were taken, the arithmetic mean exposure ages of 10Be were found to be statistically indistinguishable, with an average exposure age of 4.6 ± 0.9 ka for flow 1 and 4.9 ± 1.0 ka for flow 2, respectively. These results suggest that the corresponding effusive eruptive emissions occurred relatively quickly.

This activity is situated in the Upper Pleistocene, indicating a relatively recent period of activity consistent with most eruptions recorded in the SCVF (between the Late Pleistocene and Holocene) (Agustín-Flores et al. Reference Agustín-Flores, Siebe and Guilbaud2011) with at least eleven monogenetic volcanoes younger than ∼10 ka (Alcalá-Reygosa et al. Reference Alcalá-Reygosa, Arce, Schimmelpfennig, Salinas, Rodríguez, Léanni, Aumaître, Bourlès and Keddadouche2018).

This coincides with the findings of Agustín-Flores et al. (Reference Agustín-Flores, Siebe and Guilbaud2011), who propose a short interval between eruptive phases, estimated between 6 days and 16 months. This hypothesis is based on the low volume of material expelled in both flows, approximately 0.04 km3. Additionally, the similarities observed in the exposure ages of the rocks from flows 1 and 2 suggest that samples from both sites have been subjected to similar weathering effects. This implies comparable erosion rates and a minimal contribution of meteoric 10Be, which reinforces the idea of a compact and consecutive eruptive sequence for both flows.

The results on the exposure age of the five rocks analyzed in this study indicate that the age was not affected by the residence time of magma near the surface. Although the magmatic processes that triggered the explosive eruptive phase of Pelagatos volcano occurred at shallow depths between 1 and 4.6 km, Roberge et al. (Reference Roberge, Guilbaud, Mercer and Reyes-Luna2015) conclude that the contribution of these processes to the measured age is negligible for those distances.

Additionally, the presence of a layer of material ejected during the Tutti Frutti plinean eruption limits the estimated maximum age of the volcano. Sosa-Ceballos et al. (Reference Sosa-Ceballos, Gardner, Siebe and Macías2012) propose that this layer has a maximum 14C age between 1.3 ± 0.3 ka and 1.5 ± 0.1 ka BP. However, these estimates do not consider radiocarbon calibrated ages of 17.4 ± 0.2 ka 14C BP for an organic charcoal sample in a pyroclastic flow, and 17.6 ± 0.5 ka cal BP for an organic horizon in a paleosol, found in the same eruptive materials. According to Agustín-Flores et al. (Reference Agustín-Flores, Siebe and Guilbaud2011), these variations in ages could be due to post-depositional contamination processes by organic compounds leached during water infiltration into underlying deposits, or to errors in the estimates derived from samples taken from long-lived tree species.

These findings underline the importance of using alternative dating methods like the one proposed in this study to determine more accurately and reliably the average exposure age of the Pelagatos volcano, estimated at 4.7 ± 0.8 ka.

This average exposure age is significant for the SCVF, which has seen the formation of at least 14 monogenetic volcanoes (five basaltic and nine andesitic-dacitic) over the last 25 ka. Given that the analyzed material (basaltic andesite) contains minimal quartz, the presence of olivine phenocrysts indicates a more efficient extraction process that requires less material compared to the use of quartz xenocrysts used in other studies (e.g., Alcalá-Reygosa et al. Reference Alcalá-Reygosa, Arce, Schimmelpfennig, Salinas, Rodríguez, Léanni, Aumaître, Bourlès and Keddadouche2018). Furthermore, the use of 10Be in olivine has been proven effective for dating very early exposure ages, even up to 3.9 ± 0.8 ka, as reported by Heineke et al. (Reference Heineke, Niedermann, Hetzel and Akyl2016).

This information is particularly relevant in a region with an eruptive recurrence interval between 2.5 ± 0.1 ka and 14.1 ± 0.2 ka, which could significantly contribute to the knowledge needed for risk prevention associated with lava flows and ash fall, both in this area and in other densely populated regions (Alcalá-Reygosa et al. Reference Alcalá-Reygosa, Arce, Schimmelpfennig, Salinas, Rodríguez, Léanni, Aumaître, Bourlès and Keddadouche2018; Siebe et al. Reference Siebe, Arana-Salinas and Abrams2005).

Conclusions

This study marks the first determination of exposure ages for rocks from the Pelagatos volcano using 10Be concentrations in olivine. We recorded mean 10Be ages of 4.6 ± 0.9 ka and 4.9 ± 0.1 ka (1σ) for flow 1 and flow 2, respectively.

Considering the associated uncertainties, the average exposure age of the volcano is expected to be 4.5 ± 2 ka. To minimize the inherent uncertainties in 10Be extraction, future studies should consider analyzing a larger number of olivine crystals. Despite uncertainties exceeding 20%, the results consistently demonstrate the utility of 10Be in olivine for accurately dating volcanic rocks.

The innovative methodology employed here enables the direct dating of basic to intermediate igneous rocks from the Pelagatos volcano, overcoming challenges posed by the absence of suitable accessory minerals typically required for precise geochronological analyses. Utilizing olivine to establish exposure ages represents a significant breakthrough in geological research, offering a more direct dating method compared to the conventional reliance on indirectly dated eruption layers, which provide only a range of when the event could have occurred.

The application of the 10Be dating technique to olivine allows for the precise dating of basaltic eruptions. Nonetheless, it is recommended to validate these findings with alternative radiometric methods, such as 3He measurements, in subsequent studies.

Additionally, this method can be applied to other volcanic systems in the region, greatly enhancing our ability to refine and update the geochronological framework for volcanic activity in similar environments. This advancement is essential for complementing the volcanic history and improving the accuracy of eruption timelines previously dated by other methods.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Mr. Sergio Martínez and Mr. Antonio Morales Espino, physicists Arcadio Huerta and Roberto Hernández Reyes, Engineer Teodoro Hernández Treviño, and doctors Samuel Tehuacanero Cuapa and Óscar Ovalle Encinia for their technical support. This research was financially supported by the Dirección General de Asuntos del Personal Académico (DGAPA) of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), through the LEMA 2023 project and the PAPIIT grant IN112023. Additional support was provided by the Consejo Nacional de Humanidades, Ciencias y Tecnologías (CONAHCYT) under grant LNC-2023-58, which is gratefully acknowledged. Finally, we would like to thank Guillermina Moreno Moreno and Lic. América Cortés Valtierra for their assistance in obtaining bibliographic materials.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.