1 Introduction

A common task when administering and evaluating tests is to identify behaviors or responses that are atypical and may require special attention to ensure the integrity of the test (Bulut et al., Reference Bulut, Gorgun and He2024; Cizek & Wollack, Reference Cizek and Wollack2016; He et al., Reference He, Meadows and Black2022; Kingston & Clark, Reference Kingston and Clark2014; Wongvorachan, Reference Wongvorachan2023). For example, in writing tests, some responses might need closer inspection to establish if they were plagiarized (Foltýnek et al., Reference Foltýnek, Meuschke and Gipp2019; Gomaa & Fahmy, Reference Gomaa and Fahmy2013) or, more recently, AI-generated (Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Hao, Fauss and Li2024; Yan et al., Reference Yan, Fauss, Hao and Cui2023). In language tests, test takers might be reading off scripts or repeating after a hidden souffleur instead of speaking freely (Evanini & Wang, Reference Evanini and Wang2014; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Evanini, Bruno and Mulholland2016, Reference Wang, Evanini, Mulholland, Qian and Bruno2019). Similar tasks also occur outside a fraud detection context. For example, one might want to identify test takers that did not properly engage with the items (Booth et al., Reference Booth, Bosch and D’Mello2023; Cocea & Weibelzahl, Reference Cocea and Weibelzahl2010), that should have been provided with certain accommodations (Kettler, Reference Kettler2012; Sireci et al., Reference Sireci, Scarpati and Li2005), or are not using the provided equipment as intended (Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Jamieson, Eignor and Kirsch1998).

In many such scenarios, the respective test takers or responses are first flagged by automated systems. For example, given the large amount of potential source material, initial plagiarism checks are almost exclusively done via automated systems (Jiffriya et al., Reference Jiffriya, Jahan and Ragel2021). However, especially in high-stakes testing, relying on automated flags alone is risky because of inevitable false positives. Therefore, once a test taker has been flagged by an automated system, their case is typically reviewed in more detail before a final decision is made. The subject of this article is the design of an automated system that flags test takers for review and learns from their outcomes. Since in a testing context such reviews are typically carried out by one or more human experts, we refer to this scenario as human-in-the-loop anomaly detection. However, the proposed procedure is, in principle, agnostic to how the reviews are conducted.

Before going into more detail, it is useful to fix some terms. In what follows, we refer to the group of test takers that we seek to identify as critical group. All test takers that are not members of the critical group are referred to as the reference group. Moreover, we refer to test takers that are identified by the automated system as flagged or selected for review. If the review outcome is positive, that is, the test taker is indeed found to be a member of the critical group, we refer to the corresponding flag as a detection or true positive. If the review outcome is negative, that is, the test taker is found not to be a member of the critical group, we refer to the flag as a false alarm or false positive. The rule by which test takers are selected for review is referred to as a flagging or selection policy. Finally, depending on the context, we will say that a test taker is selected for review or that a response is selected for review. For the purpose of this article, this difference is insubstantial.

We assume that a test is administered periodically over time. The flagging procedure we aim to design is assumed to work as follows: for each test taker in the current administration, the automated system is provided with a set of features that were extracted from their response and/or behavior. The system processes these features and outputs a binary flagging decision. The goal is to find a policy that maximizes the number of test takers correctly identified as needing special attention (true positives), while keeping the number of required reviews per test administration at a manageable level. The latter is important since, depending on what it entails, an expert review can require a significant amount of resources. The features based on which the flagging decision is made are not subject to this optimization, but are assumed to be given. We refer to this problem as the flagging problem. It will be defined more formally in Section 2.

Although the methods proposed in this article potentially cover a wide range of applications, we envision them to be most useful in settings where the outcomes of multiple detectors or classifiers need to be fused (Varshney, Reference Varshney2012). For example, returning to the task of plagiarism detection, instead of relying on a single checker, multiple checkers might be run on a submitted response, each of them returning a value that quantifies how likely the response was plagiarized. A decision whether or not to flag the response then needs to be made by fusing the results of the individual checkers into a single, binary outcome.

In order to position this article in the context of existing research, it is useful to discuss some of the characteristics and requirements of the system we seek to design:

-

• We do not assume the existence of a (large) training data set. This assumption is somewhat pessimistic, but often realistic. For example, when new item types are introduced or new ways of cheating emerge, little to no data will be available to train detectors.

-

• We assume that a test taker’s group membership can be established via an expert review. However, typically only a fraction of test takers will undergo a review, thus rendering the flagging problem a semi-supervised learning problem (Van Engelen & Hoos, Reference Van Engelen and Hoos2020).

-

• In contrast to many semi-supervised learning problems, we do not assume the subset of labeled data points to be given in advance. Instead, the selection policy itself determines which data points are reviewed and labeled; in a sense, the system can and must select its own training data—a concept commonly found in active learning (Felder & Brent, Reference Felder and Brent2009).

-

• We consider data fusion the main use case of the system we seek to design. Hence, it should be able to handle “reasonably high-dimensional” feature spaces, say, on the order of tens or hundreds of features, but is not necessarily expected to process very large feature vectors commonly used in supervised machine learning (Caruana et al., Reference Caruana, Karampatziakis and Yessenalina2008).

-

• We seek to avoid strong assumptions on the number of test takers or the number of reviews conducted. That is, the system should neither require a minimum sample size, nor should compute or memory requirements limit its application to small-scale tests.

-

• In order to learn and track the feature distributions of interest, the system should be adaptive and operate in a continuous feedback loop. That is, the outcomes of expert reviews are fed back into the system, which then uses this feedback to update its parameters and in turn improve the accuracy of its selection policy.

-

• Especially in a high-stakes testing context, it is crucial that important metrics of the automated selection system, such as its false positive and false negative rate, can be evaluated or at least estimated. In the scenario considered here, this is not straightforward since only selected test takers (positives) are reviewed. Hence, metrics, such as the false negative rate, cannot be evaluated empirically. This limits the applicability of commonly used classifiers whose outputs can be interpreted as probabilities, but are not based on probabilistic models (Bielza & Larrañaga, Reference Bielza and Larrañaga2020).

In light of these requirements, we propose a Bayesian approach to the flagging problem. In particular, as will be shown in the course of the article, a Bayesian approach allows for a unified treatment of labeled and unlabeled data points, and in turn enables a seamless implementation of a feedback loop. Moreover, prior distributions make it possible to incorporate qualitative prior knowledge in cases where little or no training data is available. As more samples are collected, this prior knowledge is gradually overwritten by evidence learned from the data. A disadvantage of the Bayesian approach is that both the inference step, that is, the update of the posterior distribution, and the optimal selection policy are too complex to be implemented in practice. We address this problem by, first, using a variational approximation of the posterior distribution, and, second, proposing three heuristic selection policies corresponding to different exploration/exploitation trade-offs.

Naturally, Bayesian approaches have been used in the context of test integrity before (see, for example, Lu et al., Reference Lu, Wang and Shi2023; Marianti et al., Reference Marianti, Fox, Avetisyan, Veldkamp and Tijmstra2014; Van der Linden & Guo, Reference Van der Linden and Guo2008; van der Linden & Lewis, Reference van der Linden and Lewis2015; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Zhang and Lu2022 to name just a few). Moreover, some Bayesian methods have been proposed for general semi-supervised learning problems (Adams & Ghahramani, Reference Adams and Ghahramani2009; Bruce, Reference Bruce2001; Rottmann et al., Reference Rottmann, Kahl and Gottschalk2018). However, the specific scenario considered in this article, learning sequentially from self-selected subsets of batched data, is non-standard and non-trivial. To the best of our knowledge, it has not been investigated in detail before, and methods in the literature did not meet all of the requirements listed above.

Finally, we would like to highlight that, although they were motivated by a test integrity scenario, both the problem formulation and the inference and flagging procedures presented in this article are generic and extend beyond this specific application. In principle, the proposed methods apply whenever noisy measurements are used to select individuals or objects for expert inspection. This is the case, for example, in industrial quality control, where sensor data is used to monitor and flag defective products for manual inspection (Mitra, Reference Mitra2016), in condition-based maintenance, where predictive models are used to determine when machinery needs servicing based on wear and usage data (Prajapati et al., Reference Prajapati, Bechtel and Ganesan2012), and in cybersecurity, where anomalous network activity might be flagged for further review by security experts (Ahmed et al., Reference Ahmed, Mahmood and Hu2016).

The remainder of the article is organized as follows: In Section 2, we introduce our notation and discuss the problem formulation and the underlying assumptions in a more formal manner. The corresponding optimal selection policy is presented and discussed in Section 3. In Section 4, a variational approximation of the true posterior distribution is presented and three heuristic selection policies are proposed that are informed by properties of the optimal policy and correspond to different exploration/exploitation trade-offs. Two theoretical performance bounds are stated in Section 5. In Section 6, numerical examples are given that demonstrate the proposed procedure and compare its performance to that of off-the-shelf algorithms. Section 7 concludes the article and provides a brief outlook on open questions and possible extensions.

2 Problem formulation and assumptions

In this section, we introduce our notation, state our assumptions, discuss the underlying information flow, and give a formal definition of the flagging problem.

2.1 Notation

Random variables are denoted by uppercase letters, X, and their realizations by the corresponding lowercase letters, x. Analogously, uppercase letters, P, denote probability distributions and the corresponding lowercase letters, p, denote probability density functions (PDFs). Occasionally, subscripts are used to indicate a distribution or density of a certain random variable, say,

![]() $P_X$

and

$P_X$

and

![]() $p_X$

. We use

$p_X$

. We use

![]() $Q_X$

and

$Q_X$

and

![]() $q_X$

to indicate that the corresponding distribution or density is closely related but not identical to

$q_X$

to indicate that the corresponding distribution or density is closely related but not identical to

![]() $P_X$

or

$P_X$

or

![]() $p_X$

, respectively. For example,

$p_X$

, respectively. For example,

![]() $q_X$

might be an approximation or unnormalized version of

$q_X$

might be an approximation or unnormalized version of

![]() $p_X$

. The expected value of a random variable is written as

$p_X$

. The expected value of a random variable is written as

![]() $E[X]$

. Again, a subscript is used to explicitly indicate the random variable, say,

$E[X]$

. Again, a subscript is used to explicitly indicate the random variable, say,

![]() $E_X[c + X]$

. Equality in distribution is denoted by

$E_X[c + X]$

. Equality in distribution is denoted by

![]() $\stackrel {d}{=}$

. Unless stated otherwise, collections of variables, such as vectors and matrices, are indicated by bold font. We write

$\stackrel {d}{=}$

. Unless stated otherwise, collections of variables, such as vectors and matrices, are indicated by bold font. We write

![]() $\mathcal {A}^n$

to denote the n-fold Cartesian product of a set

$\mathcal {A}^n$

to denote the n-fold Cartesian product of a set

![]() $\mathcal {A}$

with itself. The n-dimensional probability simplex is denoted by

$\mathcal {A}$

with itself. The n-dimensional probability simplex is denoted by

![]() $\Delta ^n$

. The set of Boolean vectors of length N whose elements sum to K is denoted by

$\Delta ^n$

. The set of Boolean vectors of length N whose elements sum to K is denoted by

![]() $\mathcal {S}_K^N$

. The set of all positive semi-definite matrices of size M is denoted by

$\mathcal {S}_K^N$

. The set of all positive semi-definite matrices of size M is denoted by

![]() $\mathbb {S}_+^M$

. We further define the elliptope of correlation matrices as

$\mathbb {S}_+^M$

. We further define the elliptope of correlation matrices as ![]() , and the projection of a matrix

, and the projection of a matrix

![]() $\boldsymbol {\Sigma } \in \mathbb {S}_+^M$

on

$\boldsymbol {\Sigma } \in \mathbb {S}_+^M$

on

![]() $\mathcal {E}_M$

as

$\mathcal {E}_M$

as ![]() . Here,

. Here,

![]() $\boldsymbol {I}_M$

denotes the identity matrix of size M and

$\boldsymbol {I}_M$

denotes the identity matrix of size M and

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {diag}}(\boldsymbol {X})$

denotes the diagonal matrix with the same main diagonal elements as

$\operatorname {\mathrm {diag}}(\boldsymbol {X})$

denotes the diagonal matrix with the same main diagonal elements as

![]() $\boldsymbol {X}$

. Additional symbols and notations will be defined when they occur in the text.

$\boldsymbol {X}$

. Additional symbols and notations will be defined when they occur in the text.

We assume that a test is administered periodically at time instances

![]() $t = 1, 2,\ldots , T$

. Each administration is assumed to have

$t = 1, 2,\ldots , T$

. Each administration is assumed to have

![]() $N \geq 1$

test takers.Footnote

1

An unknown share of test takers is assumed to belong to the critical group whose members we seek to flag. In order to formalize the flagging problem, we introduce the following random variables:

$N \geq 1$

test takers.Footnote

1

An unknown share of test takers is assumed to belong to the critical group whose members we seek to flag. In order to formalize the flagging problem, we introduce the following random variables:

-

•

$R \in [0, 1]$

denotes the rate of critical group members, that is, the probability that a randomly selected test taker is a member of the critical group. R is assumed to be a latent variable.

$R \in [0, 1]$

denotes the rate of critical group members, that is, the probability that a randomly selected test taker is a member of the critical group. R is assumed to be a latent variable. -

•

$C_{t,n} \in \{0, 1\}$

indicates whether the nth test taker in the tth administration is a member of the critical group (

$C_{t,n} \in \{0, 1\}$

indicates whether the nth test taker in the tth administration is a member of the critical group (

$C_{t,n} = 1$

) or not (

$C_{t,n} = 1$

) or not (

$C_{t,n} = 0$

).

$C_{t,n} = 0$

).

$C_{t,n}$

is assumed to be a latent variable.

$C_{t,n}$

is assumed to be a latent variable. -

•

$\boldsymbol {X}_{t,n} \in \mathbb {R}^M$

,

$\boldsymbol {X}_{t,n} \in \mathbb {R}^M$

,

$M \geq 1$

, denotes the vector of features associated with the nth test taker in the tth administration.

$M \geq 1$

, denotes the vector of features associated with the nth test taker in the tth administration.

$X_{t,n}$

is assumed to be observable and provided by a given mechanism.

$X_{t,n}$

is assumed to be observable and provided by a given mechanism. -

•

$S_{t,n} \in \{0, 1\}$

indicates whether the nth test taker in the tth administration was selected for review (

$S_{t,n} \in \{0, 1\}$

indicates whether the nth test taker in the tth administration was selected for review (

$S_{t,n} = 1$

) or not (

$S_{t,n} = 1$

) or not (

$S_{t,n} = 0$

).

$S_{t,n} = 0$

).

$S_{t,n}$

is set according to the chosen selection policy.

$S_{t,n}$

is set according to the chosen selection policy. -

•

$D_{t,n} \in \{0, 1\}$

denotes whether the nth test taker of the tth administration was detected as being a member of the critical group (

$D_{t,n} \in \{0, 1\}$

denotes whether the nth test taker of the tth administration was detected as being a member of the critical group (

$D_{t,n} = 1$

) or not (

$D_{t,n} = 1$

) or not (

$D_{t,n} = 0$

).

$D_{t,n} = 0$

).

$D_{t,n}$

is the outcome of an expert review and can be observed.

$D_{t,n}$

is the outcome of an expert review and can be observed.

For the sake of a more compact notation, variables corresponding to the same administration are also written as column vectors:

Analogously, horizontal stacks of vectors of the first t administrations are written as

2.2 Information flow

Before going into more details of the model underlying the random variables defined in the previous section, it is useful to highlight how the available information evolves over time. Before the administration at time instant

![]() $t+1$

, the available data consist of the features of all previous test takers,

$t+1$

, the available data consist of the features of all previous test takers,

![]() $\boldsymbol {X}_{1:t}$

, the subset of test takers selected for review,

$\boldsymbol {X}_{1:t}$

, the subset of test takers selected for review,

![]() $\boldsymbol {S}_{1:t}$

, and the outcomes of these reviews,

$\boldsymbol {S}_{1:t}$

, and the outcomes of these reviews,

![]() $\boldsymbol {D}_{1:t}$

. We denote the

$\boldsymbol {D}_{1:t}$

. We denote the

![]() $\sigma $

-algebra of events generated by these random variables by

$\sigma $

-algebra of events generated by these random variables by

After the administration at time instant

![]() $t+1$

is completed and all responses are processed, the extracted features,

$t+1$

is completed and all responses are processed, the extracted features,

![]() $\boldsymbol {X}_{t+1}$

, become available. We denote this refined

$\boldsymbol {X}_{t+1}$

, become available. We denote this refined

![]() $\sigma $

-algebra by

$\sigma $

-algebra by

Note that the decision about which test takers to select for review should take

![]() $\boldsymbol {X}_{t+1}$

into account, hence, it can use all information available in

$\boldsymbol {X}_{t+1}$

into account, hence, it can use all information available in

![]() $\mathcal {F}^{\prime }_t$

, not just

$\mathcal {F}^{\prime }_t$

, not just

![]() $\mathcal {F}_t$

. Finally, the selected responses,

$\mathcal {F}_t$

. Finally, the selected responses,

![]() $\boldsymbol {S}_{t+1}$

, and the outcomes of the corresponding reviews,

$\boldsymbol {S}_{t+1}$

, and the outcomes of the corresponding reviews,

![]() $\boldsymbol {D}_{t+1}$

, are observed. This refines the

$\boldsymbol {D}_{t+1}$

, are observed. This refines the

![]() $\sigma $

-algebra to

$\sigma $

-algebra to

![]() $\mathcal {F}_{t+1}$

and completes the cycle. Note that

$\mathcal {F}_{t+1}$

and completes the cycle. Note that

![]() $\mathcal {F}_t \subset \mathcal {F}^{\prime }_t \subset \mathcal {F}_{t+1}$

for all

$\mathcal {F}_t \subset \mathcal {F}^{\prime }_t \subset \mathcal {F}_{t+1}$

for all

![]() $t = 1, \ldots , T-1$

.

$t = 1, \ldots , T-1$

.

2.3 Assumptions

Throughout the article, we make the following assumptions:

-

1. All group membership indicators,

$C_{t,n}$

, are independent and identically distributed Bernoulli random variables with success probability R so that

$C_{t,n}$

, are independent and identically distributed Bernoulli random variables with success probability R so that

$P(C_{t,n} = 1 \,|\, R = r) = r$

.

$P(C_{t,n} = 1 \,|\, R = r) = r$

. -

2. All feature vectors,

$\boldsymbol {X}_{t,n}$

, are independent and identically distributed conditioned on the group membership indicator

$\boldsymbol {X}_{t,n}$

, are independent and identically distributed conditioned on the group membership indicator

$C_{t,n}$

. That is, there exist two random vectors,

$C_{t,n}$

. That is, there exist two random vectors,

$\boldsymbol {X}_0$

and

$\boldsymbol {X}_0$

and

$\boldsymbol {X}_1$

, such that

$\boldsymbol {X}_1$

, such that

$\boldsymbol {X}_{t,n} | (C_{t,n} = 0) \stackrel {d}{=} \boldsymbol {X}_0$

and

$\boldsymbol {X}_{t,n} | (C_{t,n} = 0) \stackrel {d}{=} \boldsymbol {X}_0$

and

$\boldsymbol {X}_{t,n} | (C_{t,n} = 1) \stackrel {d}{=} \boldsymbol {X}_1$

for all t and n. The distributions of

$\boldsymbol {X}_{t,n} | (C_{t,n} = 1) \stackrel {d}{=} \boldsymbol {X}_1$

for all t and n. The distributions of

$\boldsymbol {X}_0$

and

$\boldsymbol {X}_0$

and

$\boldsymbol {X}_1$

are denoted by

$\boldsymbol {X}_1$

are denoted by

$P_0$

and

$P_0$

and

$P_1$

, respectively.

$P_1$

, respectively. -

3.

$P_0$

and

$P_0$

and

$P_1$

are assumed to be members of two, not necessarily identical, parametric families of distributions. That is, there exist two (vector) parameters in suitably defined spaces,

$P_1$

are assumed to be members of two, not necessarily identical, parametric families of distributions. That is, there exist two (vector) parameters in suitably defined spaces,

$\theta _0 \in \mathcal {T}_0$

and

$\theta _0 \in \mathcal {T}_0$

and

$\theta _1 \in \mathcal {T}_1$

, such that(3)

$\theta _1 \in \mathcal {T}_1$

, such that(3) $$ \begin{align} \begin{aligned} P_0 = P( \bullet \,|\, \theta_0),\\ P_1 = P( \bullet \,|\, \theta_1). \end{aligned} \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \begin{aligned} P_0 = P( \bullet \,|\, \theta_0),\\ P_1 = P( \bullet \,|\, \theta_1). \end{aligned} \end{align} $$

-

4. The selection process is modeled as follows: After each administration,

$K \leq N$

test takers are selected for review. The corresponding selection policy is a function

$K \leq N$

test takers are selected for review. The corresponding selection policy is a function

$\xi _t \colon \mathcal {S}^N \to \Delta ^N$

that assigns a probability to every possible selection vector. Each

$\xi _t \colon \mathcal {S}^N \to \Delta ^N$

that assigns a probability to every possible selection vector. Each

$\xi _t$

is assumed to be

$\xi _t$

is assumed to be

$\mathcal {F}^{\prime }_{t-1}$

-measurable, that is, the selection policy can depend only on events whose occurrence can be established based on knowledge of

$\mathcal {F}^{\prime }_{t-1}$

-measurable, that is, the selection policy can depend only on events whose occurrence can be established based on knowledge of

$\boldsymbol {X}_{1:t}$

,

$\boldsymbol {X}_{1:t}$

,

$\boldsymbol {S}_{1:t-1}$

, and

$\boldsymbol {S}_{1:t-1}$

, and

$\boldsymbol {D}_{1:t-1}$

. Note that this implies that

$\boldsymbol {D}_{1:t-1}$

. Note that this implies that

$\boldsymbol {S}_t$

and

$\boldsymbol {S}_t$

and

$\boldsymbol {C}_t$

are conditionally independent since(4)where the second equality holds since

$\boldsymbol {C}_t$

are conditionally independent since(4)where the second equality holds since $$ \begin{align} P(\boldsymbol{S}_t = \boldsymbol{s}, \boldsymbol{C}_t = \boldsymbol{c} \,|\, \mathcal{F}^{\prime}_{t-1}) &= P(\boldsymbol{S}_t = \boldsymbol{s} \,|\, \mathcal{F}^{\prime}_{t-1}) \, P(\boldsymbol{C}_t = \boldsymbol{c} \,|\, \boldsymbol{S}_t = \boldsymbol{s}, \mathcal{F}^{\prime}_{t-1}) \notag \\ &= \xi_t(\boldsymbol{s}) \, P(\boldsymbol{C}_t = \boldsymbol{c} \,|\, \mathcal{F}^{\prime}_{t-1}), \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} P(\boldsymbol{S}_t = \boldsymbol{s}, \boldsymbol{C}_t = \boldsymbol{c} \,|\, \mathcal{F}^{\prime}_{t-1}) &= P(\boldsymbol{S}_t = \boldsymbol{s} \,|\, \mathcal{F}^{\prime}_{t-1}) \, P(\boldsymbol{C}_t = \boldsymbol{c} \,|\, \boldsymbol{S}_t = \boldsymbol{s}, \mathcal{F}^{\prime}_{t-1}) \notag \\ &= \xi_t(\boldsymbol{s}) \, P(\boldsymbol{C}_t = \boldsymbol{c} \,|\, \mathcal{F}^{\prime}_{t-1}), \end{align} $$

$\boldsymbol {S}_t$

can only provide information that is already contained in

$\boldsymbol {S}_t$

can only provide information that is already contained in

$\mathcal {F}^{\prime }_{t-1}$

.

$\mathcal {F}^{\prime }_{t-1}$

.

-

5. The review process is modeled as follows: All flagged test takers are reviewed and the review resolves any ambiguity about the test taker’s group membership. Test takers that did not get flagged are automatically assumed to be members of the reference group. Unflagged members of the critical group remain undetected. This means

(5)or, using Hadamard’s element-wise vector product notation, $$ \begin{align} D_{t,n} = \begin{cases} 1, & S_{t,n} = 1, C_{t,n} = 1\\ 0, & \text{otherwise} \end{cases} \end{align} $$

(6)

$$ \begin{align} D_{t,n} = \begin{cases} 1, & S_{t,n} = 1, C_{t,n} = 1\\ 0, & \text{otherwise} \end{cases} \end{align} $$

(6) $$ \begin{align} \boldsymbol{D}_t = \boldsymbol{S}_t \odot \boldsymbol{C}_t. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \boldsymbol{D}_t = \boldsymbol{S}_t \odot \boldsymbol{C}_t. \end{align} $$

Assumptions 1 and 2 are made to simplify the mathematical analysis and to keep the model general. Possible relaxations, such as allowing dependencies between test takers (and possibly re-takers), or considering sub-populations with different feature distributions or rates of critical group members, will significantly complicate the analysis and likely depend on what behavior or phenomenon underpins the definition of the critical group. A brief outlook on possible research avenues in this direction will be given in Section 7.

Assumption 3 enables us to formulate the flagging problem in a standard Bayesian setting. An extension to a non-parametric formulation is beyond the scope of the article.

Assumption 4 is common in sequential decision making and ensures that the policy does not use information that is not available at the time the selection decision needs to be made.

Assumption 5 is likely the most controversial, and it will not always hold in practice. However, at least in the context of test security, various standards and criteria have been established according to which an expert or a panel of experts can evaluate the evidence and arrive at a well-justified decision whether or not a certain response or behavior constitutes cheating. Alternatively, one can define the critical group as those test takers who an expert considers “sufficiently curious” to be reviewed in detail, irrespective of the outcome of the review. This criterion is less sharp, but can be more applicable in practice. In general, we assume that some, potentially expensive and time-consuming, process exists that assigns “true positive” and “false positive” labels to the selected cases. The proposed procedure is agnostic to the exact meaning of these labels and the process used to assign them.

2.4 Problem formulation

As mentioned before, we adopt a Bayesian perspective in this article. That is, we assume that unknown quantities are themselves random variables, and that the joint distribution of all random variables, latent and observable, is known. We denote this joint distribution by P, so that

where

![]() $\boldsymbol {X}_{1:T}, \boldsymbol {C}_{1:T}, \boldsymbol {S}_{1:T}, \boldsymbol {D}_{1:T}$

, and R are defined in Section 2.1, and

$\boldsymbol {X}_{1:T}, \boldsymbol {C}_{1:T}, \boldsymbol {S}_{1:T}, \boldsymbol {D}_{1:T}$

, and R are defined in Section 2.1, and

![]() $\Theta _0$

and

$\Theta _0$

and

![]() $\Theta _1$

denote the parameters of the conditional feature distributions in (3).

$\Theta _1$

denote the parameters of the conditional feature distributions in (3).

Our aim is to design a selection policy,

![]() $\boldsymbol {\xi }_{1:T}$

, that maximizes the expected number of detected members of the critical group, while limiting the number of expert reviews per test administration to at most

$\boldsymbol {\xi }_{1:T}$

, that maximizes the expected number of detected members of the critical group, while limiting the number of expert reviews per test administration to at most

![]() $K \leq N$

. This leads to the following optimization problem:

$K \leq N$

. This leads to the following optimization problem:

$$ \begin{align} \max_{\boldsymbol{\xi}_{1:T}} \; E\left[ \sum_{t=1}^T \sum_{n = 1}^N D_{t,n} \right] \quad \text{s.\ t.} \quad \sum_{n = 1}^N S_{t,n} \leq K, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \max_{\boldsymbol{\xi}_{1:T}} \; E\left[ \sum_{t=1}^T \sum_{n = 1}^N D_{t,n} \right] \quad \text{s.\ t.} \quad \sum_{n = 1}^N S_{t,n} \leq K, \end{align} $$

where the constraint needs to hold almost surely for all

![]() $t = 1, \ldots , T$

.

$t = 1, \ldots , T$

.

Clearly, (8) is by no means the only way of formalizing the flagging problem. For example, one could relax the constraint to hold in expectation, constrain the false or true positive rate instead of the absolute number of reviews, or, in a more traditional Bayesian formulation, define costs of reviews, detections, false alarms, and so on. Nevertheless, we believe that the problem formulation in (8) strikes a good balance between transparency, tractability, and applicability. In particular, the question of how to set K, that is, the number of reviews one is willing to afford, is well-defined and can be understood and discussed without deeper technical knowledge. By contrast, choosing Bayesian costs is typically less straightforward and can lead to confusion about what these cost should and should not reflect. Moreover, we believe that the optimal and approximate selection policies presented in this article provide a blueprint that can be adapted to variations of the problem in (8) in a relatively straightforward manner.

3 Optimal selection policy

This section states and discusses the selection policy that solves the problem in (8). While typically too complex for practical use, it offers conceptual insights and can guide the design of approximate or heuristic policies.

Theorem 1. Let

![]() $\big ( r_t \big )_{0 \leq t \leq T}$

and

$\big ( r_t \big )_{0 \leq t \leq T}$

and

![]() $\big ( \rho _t \big )_{0 \leq t \leq T}$

with

$\big ( \rho _t \big )_{0 \leq t \leq T}$

with

![]() $r_t \colon \mathcal {X}^{(t+1)N} \times \{0, 1\}^{tN} \times \{0, 1\}^{tN} \to \mathbb {R}_+$

and

$r_t \colon \mathcal {X}^{(t+1)N} \times \{0, 1\}^{tN} \times \{0, 1\}^{tN} \to \mathbb {R}_+$

and

![]() $\rho _t \colon \mathcal {X}^{tN} \times \{0, 1\}^{tN} \times \{0, 1\}^{tN} \to \mathbb {R}_+$

be two sequences of functions that are defined recursively via

$\rho _t \colon \mathcal {X}^{tN} \times \{0, 1\}^{tN} \times \{0, 1\}^{tN} \to \mathbb {R}_+$

be two sequences of functions that are defined recursively via

and

with recursion base

![]() $\rho _T(\boldsymbol {x}_{1:T}, \boldsymbol {s}_{1:T}, \boldsymbol {d}_{1:T}) = 0$

. Let

$\rho _T(\boldsymbol {x}_{1:T}, \boldsymbol {s}_{1:T}, \boldsymbol {d}_{1:T}) = 0$

. Let

![]() $\mathcal {S}_t^* \subset \mathcal {S}_K^N$

be the set of selection vectors that attain the maximum on the right-hand side of (9). Every selection policy whose probability is concentrated on the sets

$\mathcal {S}_t^* \subset \mathcal {S}_K^N$

be the set of selection vectors that attain the maximum on the right-hand side of (9). Every selection policy whose probability is concentrated on the sets

![]() $\mathcal {S}_1^*, \ldots , \mathcal {S}_T^*$

, that is,

$\mathcal {S}_1^*, \ldots , \mathcal {S}_T^*$

, that is,

for all

![]() $t = 1, \ldots , T$

is optimal in the sense of (8).

$t = 1, \ldots , T$

is optimal in the sense of (8).

Theorem 1 is proven in Appendix A. The functions

![]() $r_t$

and

$r_t$

and

![]() $\rho _t$

represent two types of expected rewards. Specifically,

$\rho _t$

represent two types of expected rewards. Specifically,

![]() $r_t$

denotes the expected number of critical group members that will be flagged in the remaining

$r_t$

denotes the expected number of critical group members that will be flagged in the remaining

![]() $T-t$

test administrations, given the data from all previous administrations and the feature vectors of the next one. The function

$T-t$

test administrations, given the data from all previous administrations and the feature vectors of the next one. The function

![]() $\rho _t$

is then obtained by marginalizing

$\rho _t$

is then obtained by marginalizing

![]() $r_t$

over the feature vectors of the next administration with respect to their current posterior predictive distribution. In what follows, we will occasionally refer to

$r_t$

over the feature vectors of the next administration with respect to their current posterior predictive distribution. In what follows, we will occasionally refer to

![]() $\rho _t$

as a look-ahead step or function.

$\rho _t$

as a look-ahead step or function.

The optimal selection policy will be discussed in more detail shortly. Before doing so, it is instructive to investigate how the underlying probability distributions evolve as more data become available and how the conditional expectations in (9) and (10) can be calculated.

3.1 Posterior update

As more tests are administered and more reviews are conducted, more information is gathered that needs to be incorporated into the underlying Bayesian model. In this section, we detail the corresponding updates and provide expressions for the respective distributions. Of particular interest is the joint posterior distribution of

![]() $\Theta _0$

,

$\Theta _0$

,

![]() $\Theta _1$

, and R since the latter are assumed to persist between test administrations. That is,

$\Theta _1$

, and R since the latter are assumed to persist between test administrations. That is,

![]() $\Theta _0$

,

$\Theta _0$

,

![]() $\Theta _1$

, and R can be learned from the data, while the uncertainty about the group indicators,

$\Theta _1$

, and R can be learned from the data, while the uncertainty about the group indicators,

![]() $\boldsymbol {C}_t$

, will not be resolved completely in general.

$\boldsymbol {C}_t$

, will not be resolved completely in general.

Assume that the administration at time instant

![]() $t-1$

was completed, and let the corresponding conditional PDF of the persistent random variables be denoted by

$t-1$

was completed, and let the corresponding conditional PDF of the persistent random variables be denoted by

![]() $p(r, \theta _0, \theta _1 \,|\, \mathcal {F}_{t-1})$

. Now, consider the joint distribution of

$p(r, \theta _0, \theta _1 \,|\, \mathcal {F}_{t-1})$

. Now, consider the joint distribution of

![]() $\boldsymbol {X}_t$

and

$\boldsymbol {X}_t$

and

![]() $\boldsymbol {C}_t$

conditioned on the model parameters:

$\boldsymbol {C}_t$

conditioned on the model parameters:

$$ \begin{align} &= \prod_{n=1}^N \left[ r \, p(x_n \,|\, \theta_{1}) \right]^{c_n} \left[ (1 - r) \, p(x_n \,|\, \theta_{0}) \right]^{1 - c_n}\end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} &= \prod_{n=1}^N \left[ r \, p(x_n \,|\, \theta_{1}) \right]^{c_n} \left[ (1 - r) \, p(x_n \,|\, \theta_{0}) \right]^{1 - c_n}\end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} &= r^{\lVert \boldsymbol{c} \rVert_1} (1-r)^{N - \lVert \boldsymbol{c} \rVert_1} \, \prod_{n=1}^N p(x_n \,|\, \theta_{1})^{c_n} p(x_n \,|\, \theta_{0})^{1 - c_n}. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} &= r^{\lVert \boldsymbol{c} \rVert_1} (1-r)^{N - \lVert \boldsymbol{c} \rVert_1} \, \prod_{n=1}^N p(x_n \,|\, \theta_{1})^{c_n} p(x_n \,|\, \theta_{0})^{1 - c_n}. \end{align} $$

Since conditioning on the model parameters renders the distribution independent of the specific administration, we dropped the time index in the notation. By marginalizing out the unknown group membership, we obtain the feature distribution for a given set of model parameters:

$$ \begin{align} &= \sum_{\boldsymbol{c} \in \mathcal{S}^N} r^{\lVert \boldsymbol{c} \rVert_1} (1-r)^{N - \lVert \boldsymbol{c} \rVert_1} \, \prod_{n=1}^N p(x_n \,|\, \theta_{1})^{c_n} p(x_n \,|\, \theta_{0})^{1 - c_n}. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} &= \sum_{\boldsymbol{c} \in \mathcal{S}^N} r^{\lVert \boldsymbol{c} \rVert_1} (1-r)^{N - \lVert \boldsymbol{c} \rVert_1} \, \prod_{n=1}^N p(x_n \,|\, \theta_{1})^{c_n} p(x_n \,|\, \theta_{0})^{1 - c_n}. \end{align} $$

Averaging over the unknown model parameters yields the posterior predictive distribution of the features at time instant t:

where the expected value is taken with respect to the current model posterior,

![]() $p(r, \theta _0, \theta _1 \,|\, \mathcal {F}_{t-1})$

. Note that the posterior predictive in (18) is needed for the look-ahead step in (10).

$p(r, \theta _0, \theta _1 \,|\, \mathcal {F}_{t-1})$

. Note that the posterior predictive in (18) is needed for the look-ahead step in (10).

Now, assume that the test administration at time instant t was completed and that

![]() $\boldsymbol {X}_t = \boldsymbol {x}_t$

was observed. In order to determine the optimal selection policy in (9), we require the posterior distribution of the group memberships,

$\boldsymbol {X}_t = \boldsymbol {x}_t$

was observed. In order to determine the optimal selection policy in (9), we require the posterior distribution of the group memberships,

![]() $\boldsymbol {C}_t$

, conditioned on all previous observations. According to Bayes’ rule, this distribution is given by

$\boldsymbol {C}_t$

, conditioned on all previous observations. According to Bayes’ rule, this distribution is given by

$$ \begin{align} p(\boldsymbol{c}_t \,|\, \mathcal{F}_{t-1}') = \frac{p(\boldsymbol{x}_t, \boldsymbol{c}_t \,|\, \mathcal{F}_{t-1})}{p(\boldsymbol{x}_t \,|\, \mathcal{F}_{t-1})} = \frac{E\big[ p(\boldsymbol{c}_t, \boldsymbol{x}_t \,|\, R, \Theta_0, \Theta_1) \,|\, \mathcal{F}_{t-1}\big]}{E\big[ p(\boldsymbol{x}_t \,|\, R, \Theta_0, \Theta_1) \,|\, \mathcal{F}_{t-1}\big]}, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} p(\boldsymbol{c}_t \,|\, \mathcal{F}_{t-1}') = \frac{p(\boldsymbol{x}_t, \boldsymbol{c}_t \,|\, \mathcal{F}_{t-1})}{p(\boldsymbol{x}_t \,|\, \mathcal{F}_{t-1})} = \frac{E\big[ p(\boldsymbol{c}_t, \boldsymbol{x}_t \,|\, R, \Theta_0, \Theta_1) \,|\, \mathcal{F}_{t-1}\big]}{E\big[ p(\boldsymbol{x}_t \,|\, R, \Theta_0, \Theta_1) \,|\, \mathcal{F}_{t-1}\big]}, \end{align} $$

where, again, all expected values are taken with respect to

![]() $p(r, \theta _0, \theta _1 \,|\, \mathcal {F}_{t-1})$

.

$p(r, \theta _0, \theta _1 \,|\, \mathcal {F}_{t-1})$

.

Given (19), the optimal selection vector can, in principle, be determined by finding the maximum in (9), and the corresponding test takers can be reviewed. In our model, this corresponds to observing

![]() $\boldsymbol {S}_t = \boldsymbol {s}_t$

and

$\boldsymbol {S}_t = \boldsymbol {s}_t$

and

![]() $\boldsymbol {D}_t = \boldsymbol {d}_t$

. This new information leads to the model update

$\boldsymbol {D}_t = \boldsymbol {d}_t$

. This new information leads to the model update

The likelihood in the numerator of (20) is given by

where we used Iverson bracket notation as a shorthand for the indicator function, meaning that the summands on the right-hand side of (23) are zero unless

![]() $\boldsymbol {d}_t = \boldsymbol {s}_t \odot \boldsymbol {c}_t$

holds. Now, define

$\boldsymbol {d}_t = \boldsymbol {s}_t \odot \boldsymbol {c}_t$

holds. Now, define

where ![]() . Note that

. Note that

![]() $q(\boldsymbol {x}, \boldsymbol {s}, \boldsymbol {d} \,|\, r, \theta _1, \theta _1)$

in (24) and

$q(\boldsymbol {x}, \boldsymbol {s}, \boldsymbol {d} \,|\, r, \theta _1, \theta _1)$

in (24) and

![]() $p(\boldsymbol {x} \,|\, r, \theta _1, \theta _1)$

in (17) are closely related. While the latter is obtained by summing over all possible group memberships, the former is obtained by summing only over those that are compatible with the observed review outcomes. This implies that (24) needs to be normalized to be a valid PDF. The final posterior update is then given by

$p(\boldsymbol {x} \,|\, r, \theta _1, \theta _1)$

in (17) are closely related. While the latter is obtained by summing over all possible group memberships, the former is obtained by summing only over those that are compatible with the observed review outcomes. This implies that (24) needs to be normalized to be a valid PDF. The final posterior update is then given by

$$ \begin{align} p(r, \theta_0, \theta_1 \,|\, \mathcal{F}_t) = \frac{q(\boldsymbol{x}_t, \boldsymbol{s}_t, \boldsymbol{d}_t \,|\, r, \theta_0, \theta_1)}{E\big[ q(\boldsymbol{x}_t, \boldsymbol{s}_t, \boldsymbol{d}_t \,|\, R, \Theta_0, \Theta_1) \,|\, \mathcal{F}_{t-1} \big]} \, p(r, \theta_0, \theta_1 \,|\, \mathcal{F}_{t-1}). \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} p(r, \theta_0, \theta_1 \,|\, \mathcal{F}_t) = \frac{q(\boldsymbol{x}_t, \boldsymbol{s}_t, \boldsymbol{d}_t \,|\, r, \theta_0, \theta_1)}{E\big[ q(\boldsymbol{x}_t, \boldsymbol{s}_t, \boldsymbol{d}_t \,|\, R, \Theta_0, \Theta_1) \,|\, \mathcal{F}_{t-1} \big]} \, p(r, \theta_0, \theta_1 \,|\, \mathcal{F}_{t-1}). \end{align} $$

The factor

![]() $\xi _t(\boldsymbol {s}_t)$

in (23) is

$\xi _t(\boldsymbol {s}_t)$

in (23) is

![]() $\mathcal {F}_{t-1}$

-measurable and cancels out in the normalization. The update steps now repeat with

$\mathcal {F}_{t-1}$

-measurable and cancels out in the normalization. The update steps now repeat with

![]() $t \leftarrow t+1$

(see Figure 1 for a graphical illustration of the process).

$t \leftarrow t+1$

(see Figure 1 for a graphical illustration of the process).

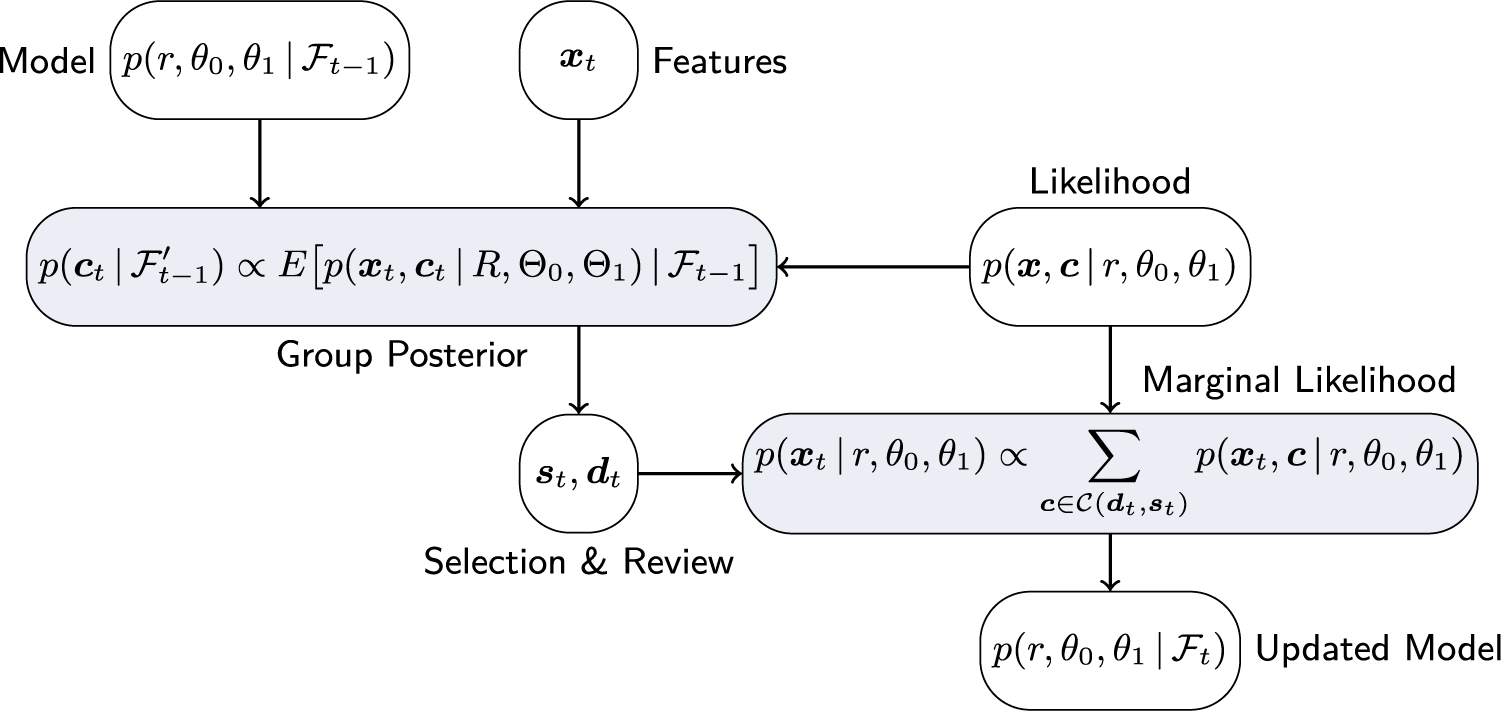

Figure 1 Graphical illustration of information flow and posterior update of the Bayesian model.

3.2 Discussion

In this section, we briefly discuss the general structure and some properties of the optimal selection policy stated in Theorem 1. This discussion will also provide qualitative insights that can inform the design of approximate procedures.

By inspection, the optimal selection policy in (9) maximizes the expected value of a sum of two terms,

![]() $\boldsymbol {s}^\intercal \boldsymbol {C}_t$

and

$\boldsymbol {s}^\intercal \boldsymbol {C}_t$

and

![]() $\rho _t$

. The first term corresponds to the number of critical group members detected in the current administration; the second term corresponds to the expected number of critical group members detected in all future administrations. This trade-off between immediate and future rewards is typical for sequential decision-making procedures. However, there are a few aspects that are non-standard:

$\rho _t$

. The first term corresponds to the number of critical group members detected in the current administration; the second term corresponds to the expected number of critical group members detected in all future administrations. This trade-off between immediate and future rewards is typical for sequential decision-making procedures. However, there are a few aspects that are non-standard:

-

• In general, the optimal policy at time t depends on all data observed so far and requires averaging over all future data. This results in extremely high complexity, even for small T and N, making strictly optimal policies virtually impossible to compute in practice.

-

• In line with the information evolving in two steps, compare Section 2.2, the calculation of the expected reward in Theorem 1 is split into two parts. First, in (9), the review outcomes are predicted based on the observed features,

$\boldsymbol {X}_t$

. Then, in (10), the features themselves are predicted based on the data from previous administrations. These two expectations correspond to two different sources of uncertainty: feature vectors need to be estimated to predict future rewards, but can in principle be observed. In contrast, the group memberships need to be estimated because they are unobservable to begin with.

$\boldsymbol {X}_t$

. Then, in (10), the features themselves are predicted based on the data from previous administrations. These two expectations correspond to two different sources of uncertainty: feature vectors need to be estimated to predict future rewards, but can in principle be observed. In contrast, the group memberships need to be estimated because they are unobservable to begin with. -

• The optimization over the selection vector,

$\boldsymbol {s}$

, is “sandwiched” between the two expected values discussed in the previous bullet point. It happens inside the expectation over the feature vectors, which are available at the time the selection is made, but outside the expectation over the unknown group memberships.

$\boldsymbol {s}$

, is “sandwiched” between the two expected values discussed in the previous bullet point. It happens inside the expectation over the feature vectors, which are available at the time the selection is made, but outside the expectation over the unknown group memberships. -

• There always exists a deterministic optimal selection policy. This follows directly from the fact that in (A.13) a function that is linear in the optimization variable,

$\xi _t$

, is maximized over a probability simplex. Therefore, at least one vertex attains the maximum, and any vertex of a probability simplex corresponds to a single point mass on the respective outcome.

$\xi _t$

, is maximized over a probability simplex. Therefore, at least one vertex attains the maximum, and any vertex of a probability simplex corresponds to a single point mass on the respective outcome. -

• The update of the posterior distribution detailed in Section 3.1 depends on the selection, but not on the selection policy. This is the case since the selected test takers only enter via the marginalization in (24). The latter requires knowledge of the selection,

$\boldsymbol {s}$

, but is independent of how this selection was made.

$\boldsymbol {s}$

, but is independent of how this selection was made. -

• In principle, it is not necessary to track

$\boldsymbol {S}_t$

and

$\boldsymbol {S}_t$

and

$\boldsymbol {D}_t$

separately. Both can be combined into a single vector that indicates if the respective test taker is known to be a member of the critical group, of the reference group, or if their group membership is unknown. We decided to go with the slightly lengthier notation since we believe it to be conceptually simpler.

$\boldsymbol {D}_t$

separately. Both can be combined into a single vector that indicates if the respective test taker is known to be a member of the critical group, of the reference group, or if their group membership is unknown. We decided to go with the slightly lengthier notation since we believe it to be conceptually simpler.

This concludes the discussion of the optimal selection policy. Based on the insights gained, we now turn to the design of approximate selection policies that are practical to implement.

4 Approximate methods

For the reasons discussed above, implementing the optimal selection policy is prohibitively complex, even for small N and T. In this section, we present heuristic policies that are significantly simpler yet sufficiently flexible and powerful to be useful in practice.

As discussed in Section 3.2, the update of the posterior distribution is independent of the selection policy. Therefore, we treat the two separately: first, we propose a variational approximation of the posterior distribution, and, second, we discuss three selection policies that can be used in conjunction with the approximate posterior update.

4.1 Approximate posterior update

The approximation method proposed in this section is essentially an expectation maximization (EM) algorithm (Dempster et al., Reference Dempster, Laird and Rubin2018). However, it also incorporates ideas from the mixture-based extended auto-regressive model, see (Šmídl & Quinn, Reference Šmídl and Quinn2006, Chapter 8), and basic copula theory (Jaworski et al., Reference Jaworski, Durante, Hardle and Rychlik2010). First, each element of the feature vector,

![]() $\boldsymbol {X}$

, is assumed to follow a distribution from the exponential family. That is,

$\boldsymbol {X}$

, is assumed to follow a distribution from the exponential family. That is,

with natural parameters

![]() $\eta _m \in \mathcal {T}_m$

, base measure

$\eta _m \in \mathcal {T}_m$

, base measure

![]() $h_m$

, sufficient statistic

$h_m$

, sufficient statistic

![]() $T_m$

, log-partition

$T_m$

, log-partition

![]() $A_m$

and

$A_m$

and

![]() $m = 1, \ldots , M$

. Correlations between the elements of

$m = 1, \ldots , M$

. Correlations between the elements of

![]() $\boldsymbol {X}$

are modeled via a Gaussian copula. To this end, we define the random vector

$\boldsymbol {X}$

are modeled via a Gaussian copula. To this end, we define the random vector

![]() $\boldsymbol {Z} \in \mathbb {R}^M$

as

$\boldsymbol {Z} \in \mathbb {R}^M$

as

where

![]() $F_{\boldsymbol {\eta }_m}$

denotes the cumulative distribution function (CDF) of

$F_{\boldsymbol {\eta }_m}$

denotes the cumulative distribution function (CDF) of

![]() $P_{X_m}$

, and

$P_{X_m}$

, and

![]() $\Phi $

denotes the CDF of the standard normal distribution. The random vector

$\Phi $

denotes the CDF of the standard normal distribution. The random vector

![]() $\boldsymbol {Z}$

is then modeled as normally distributed with mean zero and covariance

$\boldsymbol {Z}$

is then modeled as normally distributed with mean zero and covariance

![]() $\boldsymbol {\Sigma }$

, that is,

$\boldsymbol {\Sigma }$

, that is,

![]() $\boldsymbol {Z} \sim \mathcal {N}(\boldsymbol {0}, \boldsymbol {\Sigma })$

. It can be shown that (26) and (27) define a class of distributions with PDFs

$\boldsymbol {Z} \sim \mathcal {N}(\boldsymbol {0}, \boldsymbol {\Sigma })$

. It can be shown that (26) and (27) define a class of distributions with PDFs

$$ \begin{align} p_{\boldsymbol{X}}(\boldsymbol{x} \,|\, \theta) = p_{\boldsymbol{X}}(\boldsymbol{x} \,|\, \boldsymbol{\eta}, \boldsymbol{\Sigma}) = p_{\boldsymbol{Z}}(\boldsymbol{z} \,|\, \boldsymbol{\Sigma}) \, \prod_{m=1}^M g(x_m \,|\, \eta_m). \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} p_{\boldsymbol{X}}(\boldsymbol{x} \,|\, \theta) = p_{\boldsymbol{X}}(\boldsymbol{x} \,|\, \boldsymbol{\eta}, \boldsymbol{\Sigma}) = p_{\boldsymbol{Z}}(\boldsymbol{z} \,|\, \boldsymbol{\Sigma}) \, \prod_{m=1}^M g(x_m \,|\, \eta_m). \end{align} $$

Here,

![]() $\boldsymbol {z}$

is calculated from

$\boldsymbol {z}$

is calculated from

![]() $\boldsymbol {x}$

according to (27),

$\boldsymbol {x}$

according to (27),

![]() $p_{\boldsymbol {Z}}( \bullet \,|\, \boldsymbol {\Sigma })$

denotes the PDF of a zero-mean multivariate normal distribution with covariance matrix

$p_{\boldsymbol {Z}}( \bullet \,|\, \boldsymbol {\Sigma })$

denotes the PDF of a zero-mean multivariate normal distribution with covariance matrix

![]() $\boldsymbol {\Sigma }$

, and we defined

$\boldsymbol {\Sigma }$

, and we defined

where

![]() $\operatorname {\mathrm {erfc}}$

denotes the complementary error function.

$\operatorname {\mathrm {erfc}}$

denotes the complementary error function.

The model in (28) is assumed to hold under both hypotheses, that is, for test takers in the critical group and in the reference group. The corresponding parameters and functions are denoted by an additional subscript

![]() $i \in \{0,1\}$

, for example,

$i \in \{0,1\}$

, for example,

![]() $\eta _{i,m}$

. Note that the exponential families of distributions do not need to be of the same type under both hypotheses.

$\eta _{i,m}$

. Note that the exponential families of distributions do not need to be of the same type under both hypotheses.

A priori, we assume the free parameters to be independent and distributed according to

where Beta denotes the beta distribution,

![]() $\mathcal {W}^{-1}$

denotes the inverse Wishart distribution, and

$\mathcal {W}^{-1}$

denotes the inverse Wishart distribution, and

![]() $\Pi _m$

denotes the conjugate prior of the exponential family distribution corresponding to the density in (26). This distribution exists and its density is of the form

$\Pi _m$

denotes the conjugate prior of the exponential family distribution corresponding to the density in (26). This distribution exists and its density is of the form

The parameters

![]() $\nu _0$

and

$\nu _0$

and

![]() $\nu _1$

, which represent the effective number of observed samples under each hypothesis, are shared across all priors. Allowing for different initial effective sample sizes,

$\nu _1$

, which represent the effective number of observed samples under each hypothesis, are shared across all priors. Allowing for different initial effective sample sizes,

![]() $\nu _0^{(0)}$

and

$\nu _0^{(0)}$

and

![]() $\nu _1^{(0)}$

, is straightforward. We do not introduce this modification here, as it would significantly complicate the notation. In practice, however, it can be the case that, for example, one has more prior knowledge about the cheating rate distribution than the feature distribution.

$\nu _1^{(0)}$

, is straightforward. We do not introduce this modification here, as it would significantly complicate the notation. In practice, however, it can be the case that, for example, one has more prior knowledge about the cheating rate distribution than the feature distribution.

While not guaranteed to accurately reflect the true prior knowledge in general, we consider the conjugate priors in (30)–(32) a useful and robust choice in practice—mainly for two reasons: First, as will become clear later in this section, conjugate priors significantly reduce computational complexity and eliminate the need for Monte Carlo sampling or numerical optimization in the inference step. Second, they are arguably a good fit for the problem at hand. Since the flagging procedure is assumed to run periodically, a natural prior for the parameters at time t is simply the posterior from the previous time instant,

![]() $t-1$

. In this chain, later priors are more accurate, as they incorporate more information. This effect is captured by the conjugate priors, which, by construction, remain of the same type after each administration, but increase their effective sample size, reflecting the larger set of training data. In the absence of training data, the least informative prior is obtained by setting the effective sample size to its minimum feasible value.

$t-1$

. In this chain, later priors are more accurate, as they incorporate more information. This effect is captured by the conjugate priors, which, by construction, remain of the same type after each administration, but increase their effective sample size, reflecting the larger set of training data. In the absence of training data, the least informative prior is obtained by setting the effective sample size to its minimum feasible value.

Based on the model specified above, we propose the following approximate posterior update. At time instant t, the approximate posterior distributions of R,

![]() $\boldsymbol {\Sigma }_i$

, and

$\boldsymbol {\Sigma }_i$

, and

![]() $H_{m,i}$

are given by

$H_{m,i}$

are given by

The distribution parameters on the right-hand side,

![]() $\chi _{i,m}^{(t)}$

,

$\chi _{i,m}^{(t)}$

,

![]() $\boldsymbol {\Psi }_t^{(t)}$

, and

$\boldsymbol {\Psi }_t^{(t)}$

, and

![]() $\nu _i^{(t)}$

, are obtained from their previous values,

$\nu _i^{(t)}$

, are obtained from their previous values,

![]() $\chi _{i,m}^{(t-1)}$

,

$\chi _{i,m}^{(t-1)}$

,

![]() $\boldsymbol {\Psi }_t^{(t-1)}$

, and

$\boldsymbol {\Psi }_t^{(t-1)}$

, and

![]() $\nu _i^{(t-1)}$

, by solving the following system of equations:

$\nu _i^{(t-1)}$

, by solving the following system of equations:

$$ \begin{align} q_{C_{t,n}}(1) &= s_{t,n} d_{t,n} + (1 - s_{t,n}) \frac{\nu_{1}^{(t)} \, p_{\boldsymbol{X}}\Big(\boldsymbol{x}_{t,n} \,|\, \hat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_1^{(t)}, \mathcal{P}_{\mathcal{E}}\big( \boldsymbol{\Psi}_1^{(t)}\big) \Big)}{\sum_{j=0}^1 \nu_{j}^{(t)} \, p_{\boldsymbol{X}}\Big(\boldsymbol{x}_{t,n} \,|\, \hat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_j^{(t)}, \mathcal{P}_{\mathcal{E}}\big( \boldsymbol{\Psi}_j^{(t)}\big) \Big)}, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} q_{C_{t,n}}(1) &= s_{t,n} d_{t,n} + (1 - s_{t,n}) \frac{\nu_{1}^{(t)} \, p_{\boldsymbol{X}}\Big(\boldsymbol{x}_{t,n} \,|\, \hat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_1^{(t)}, \mathcal{P}_{\mathcal{E}}\big( \boldsymbol{\Psi}_1^{(t)}\big) \Big)}{\sum_{j=0}^1 \nu_{j}^{(t)} \, p_{\boldsymbol{X}}\Big(\boldsymbol{x}_{t,n} \,|\, \hat{\boldsymbol{\eta}}_j^{(t)}, \mathcal{P}_{\mathcal{E}}\big( \boldsymbol{\Psi}_j^{(t)}\big) \Big)}, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \nu_i^{(t)} &= \nu_i^{(t-1)} + \sum_{n=1}^N q_{C_{t,n}}(i), \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \nu_i^{(t)} &= \nu_i^{(t-1)} + \sum_{n=1}^N q_{C_{t,n}}(i), \end{align} $$

where

![]() $i \in \{0,1\}$

and

$i \in \{0,1\}$

and

![]() $\boldsymbol {z}_{i,t,n} = \Phi ^{-1}\big ( F_{\hat {\boldsymbol {\eta }}_i^{(t)}}(\boldsymbol {x}_{t,n} ) \big )$

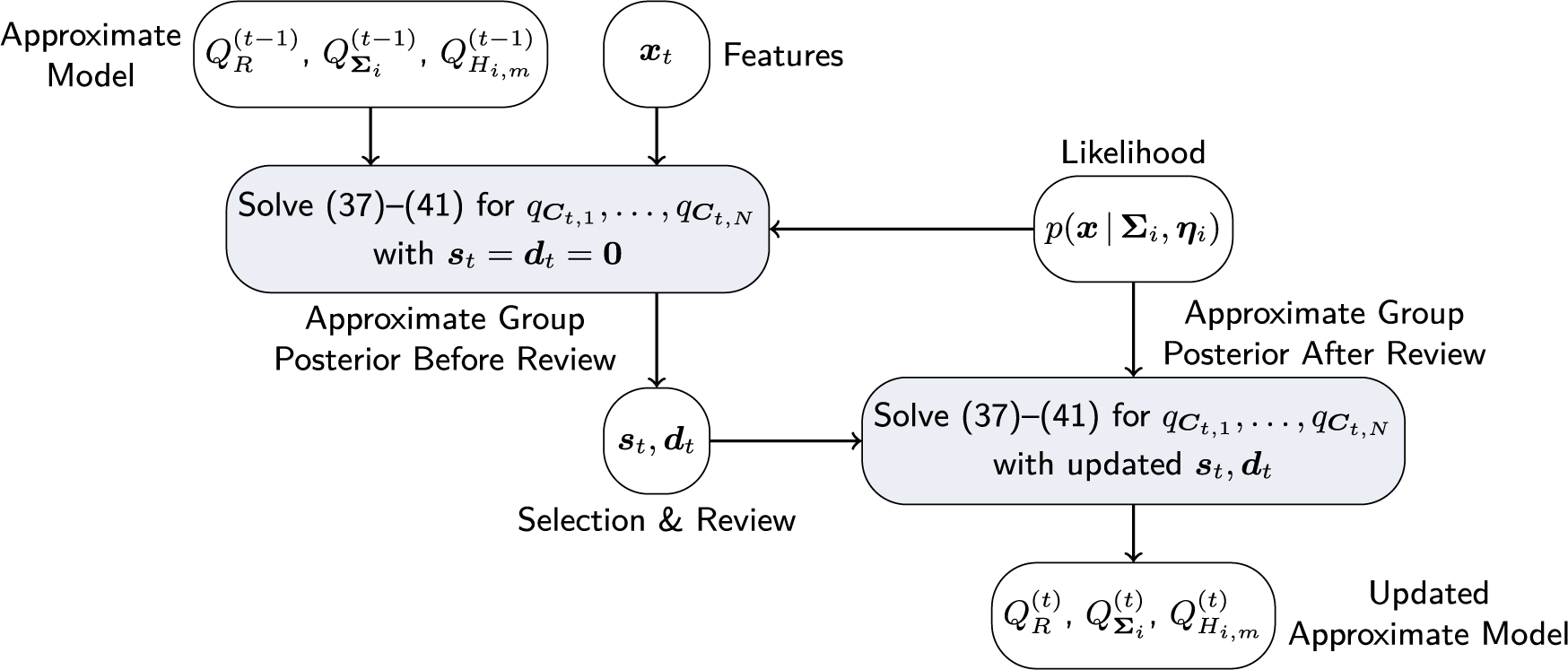

. The proposed approximate posterior update for a given selection policy is summarized in Algorithm 1, a graphical illustration in analogy to Figure 1 is shown in Figure 2.

$\boldsymbol {z}_{i,t,n} = \Phi ^{-1}\big ( F_{\hat {\boldsymbol {\eta }}_i^{(t)}}(\boldsymbol {x}_{t,n} ) \big )$

. The proposed approximate posterior update for a given selection policy is summarized in Algorithm 1, a graphical illustration in analogy to Figure 1 is shown in Figure 2.

Note that the posterior update in Algorithm 1 is run twice—once before the test takers are selected and once after the reviews are completed. The purpose of the first update is to obtain the approximate posterior distributions of the group indicator variables,

![]() $q_{C_{t,n}}$

. The selection policies discussed in the next section are all based on these distributions. The purpose of the second update is to refine the estimates of

$q_{C_{t,n}}$

. The selection policies discussed in the next section are all based on these distributions. The purpose of the second update is to refine the estimates of

![]() $\nu _i^{(t)}$

,

$\nu _i^{(t)}$

,

![]() $\chi _i^{(t)}$

, and

$\chi _i^{(t)}$

, and

![]() $\boldsymbol {\Psi }_i^{(t)}$

by incorporating the outcomes of the reviews. The difference between the first and second runs is reflected in (37), where the probability that the nth test taker of the tth administration is a member of the critical group is estimated from the observed features in case the test taker has not been reviewed (

$\boldsymbol {\Psi }_i^{(t)}$

by incorporating the outcomes of the reviews. The difference between the first and second runs is reflected in (37), where the probability that the nth test taker of the tth administration is a member of the critical group is estimated from the observed features in case the test taker has not been reviewed (

![]() $s_{t,n} = 0$

), or is set to the true label,

$s_{t,n} = 0$

), or is set to the true label,

![]() $d_{t,n}$

, if the review outcome is known (

$d_{t,n}$

, if the review outcome is known (

![]() $s_{t,n} = 1$

).

$s_{t,n} = 1$

).

The idea underlying the update equations in (37)–(41) is to start with the priors in (30)–(32) and approximate the posterior distributions via a mean-field variational approximation (Blei et al., Reference Blei, Kucukelbir and McAuliffe2017; Šmídl & Quinn, Reference Šmídl and Quinn2006). By construction, this approximation yields posterior distributions that are of the same type as the priors, and whose parameters are determined implicitly by a system of equations. However, this system is still hard to solve since it involves expectations taken with respect to the current posterior distribution. In order to simplify the evaluation of the latter, we use maximum a posteriori probability (MAP) estimates as an approximation of the expected values. More precisely, to evaluate the posterior group membership probabilities in (37), we calculate MAP estimates of the marginal parameters in (38). Once the marginal parameters are fixed, the observations,

![]() $\boldsymbol {x}_{t,n}$

, can be mapped to the “Gaussian domain,”

$\boldsymbol {x}_{t,n}$

, can be mapped to the “Gaussian domain,”

![]() $\boldsymbol {z}_{t,n}$

, via (27). The latter can then be used to update the covariance posterior in (39). The effective sample sizes and the parameters of the posterior distributions of the marginal parameters are updated according to (40) and (41). Of course, since all updates are coupled, they cannot simply be performed in sequence, but need to be solved jointly. We will further elaborate on this aspect later in this section.

$\boldsymbol {z}_{t,n}$

, via (27). The latter can then be used to update the covariance posterior in (39). The effective sample sizes and the parameters of the posterior distributions of the marginal parameters are updated according to (40) and (41). Of course, since all updates are coupled, they cannot simply be performed in sequence, but need to be solved jointly. We will further elaborate on this aspect later in this section.

Finally, note that in the model updates (39)–(41), the posterior group probabilities are used as weights, that is, the observation

![]() $x_{t,n}$

contributes to the model of the critical group with weight

$x_{t,n}$

contributes to the model of the critical group with weight

![]() $q_{C_{n,t}}(1)$

and to the model of the reference group with weight

$q_{C_{n,t}}(1)$

and to the model of the reference group with weight

![]() $q_{C_{n,t}}(0) = 1 - q_{C_{n,t}}(1)$

. This observation will later be used in the derivation of heuristic selection policies.

$q_{C_{n,t}}(0) = 1 - q_{C_{n,t}}(1)$

. This observation will later be used in the derivation of heuristic selection policies.

Before concluding this section, we briefly discuss some implementation aspects of Algorithm 1:

-

• There are various ways of solving the equation system in (37)–(41) in practice. A natural approach is to iterate over the updates until all parameters and probabilities have converged. Alternatively, one can use standard numerical solvers. In this case, it is useful to consider only

$q_{C_{t,n}}(1)$

,

$q_{C_{t,n}}(1)$

,

${n = 1, \ldots , N}$

, as free variables since all other variables are fixed once all

${n = 1, \ldots , N}$

, as free variables since all other variables are fixed once all

$q_{C_{t,n}}(1)$

are given. Note that this means that the equation system is of size N in the first update step of Algorithm 1 and of size

$q_{C_{t,n}}(1)$

are given. Note that this means that the equation system is of size N in the first update step of Algorithm 1 and of size

$N - K$

in the second.

$N - K$

in the second. -

• Depending on the choice of the marginal distributions, the optimization problems in (38) may not have a closed-form solution. However, even if (38) needs to be solved numerically, the underlying distributions are univariate so the number of parameters is typically small. Moreover, for given

$\chi _{i,m}$

and

$\chi _{i,m}$

and

$\nu _{i,m}$

, the

$\nu _{i,m}$

, the

$2 M$

problems in (38) can be solved in parallel.

$2 M$

problems in (38) can be solved in parallel. -

• In (37), the covariance matrix of the feature distribution is projected on the elliptope of correlation matrices. This projection is not strictly necessary. However, in our experiments, it leads to an improved performance. This is likely the case because the true

$\boldsymbol {\Sigma }$

has unit diagonal elements if the model in (26) holds exactly. However, in practice, replacing the projection in (37) with the maximum likelihood estimate,

$\boldsymbol {\Sigma }$

has unit diagonal elements if the model in (26) holds exactly. However, in practice, replacing the projection in (37) with the maximum likelihood estimate,

$\frac {\boldsymbol {\Psi }_i}{\nu _i + M + 1}$

might improve the performance in some cases.

$\frac {\boldsymbol {\Psi }_i}{\nu _i + M + 1}$

might improve the performance in some cases. -

• In practice,

$\theta _0$

,

$\theta _0$

,

$\theta _1$

, and r do not necessarily remain constant for all

$\theta _1$

, and r do not necessarily remain constant for all

$t = 1, \ldots , T$

. While initially the Bayesian model can and will adapt to variations, the more samples are observed, the higher its “inertia” becomes. In order to counteract this effect, past observations can be down-weighted in the posterior update. For example, an exponential decay can be introduced by making the substitutions

$t = 1, \ldots , T$

. While initially the Bayesian model can and will adapt to variations, the more samples are observed, the higher its “inertia” becomes. In order to counteract this effect, past observations can be down-weighted in the posterior update. For example, an exponential decay can be introduced by making the substitutions

$\nu _i^{(t-1)} \leftarrow \omega \nu _i^{(t-1)}$

,

$\nu _i^{(t-1)} \leftarrow \omega \nu _i^{(t-1)}$

,

$\chi _i^{(t-1)} \leftarrow \omega \chi _i^{(t-1)}$

, and

$\chi _i^{(t-1)} \leftarrow \omega \chi _i^{(t-1)}$

, and

$\boldsymbol {\Psi }_i^{(t-1)} \leftarrow \omega \boldsymbol {\Psi }_i^{(t-1)}$

in (39)–(41), where

$\boldsymbol {\Psi }_i^{(t-1)} \leftarrow \omega \boldsymbol {\Psi }_i^{(t-1)}$

in (39)–(41), where

${0 < \omega < 1}$

is a weight that balances adaptivity and steady-state performance—compare (Šmídl & Quinn, Reference Šmídl and Quinn2006, Section 8.6).

${0 < \omega < 1}$

is a weight that balances adaptivity and steady-state performance—compare (Šmídl & Quinn, Reference Šmídl and Quinn2006, Section 8.6).

4.2 Approximate selection policies

The algorithm proposed in the previous section offers a mechanism to track the posterior distributions of the model parameters for a given selection policy. However, it does not answer the question of how to choose a selection policy in the first place. This question will be addressed in this section.

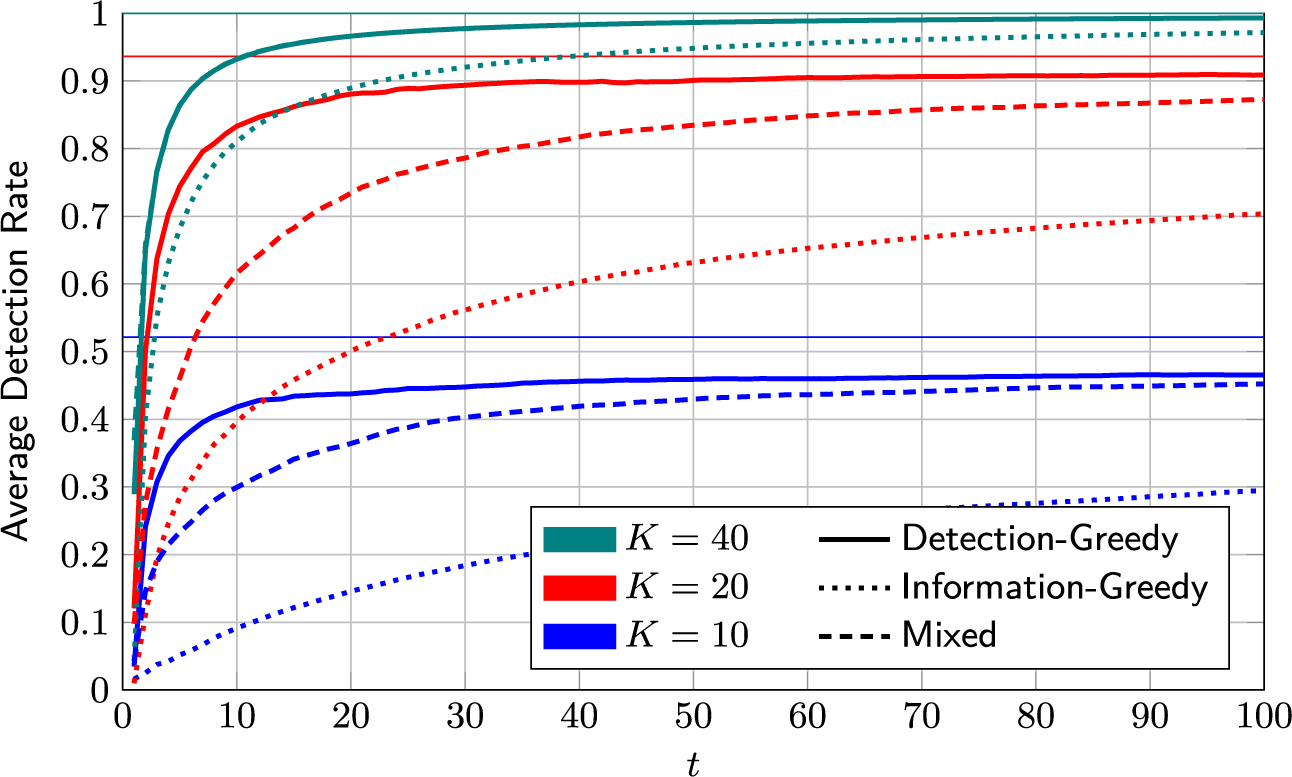

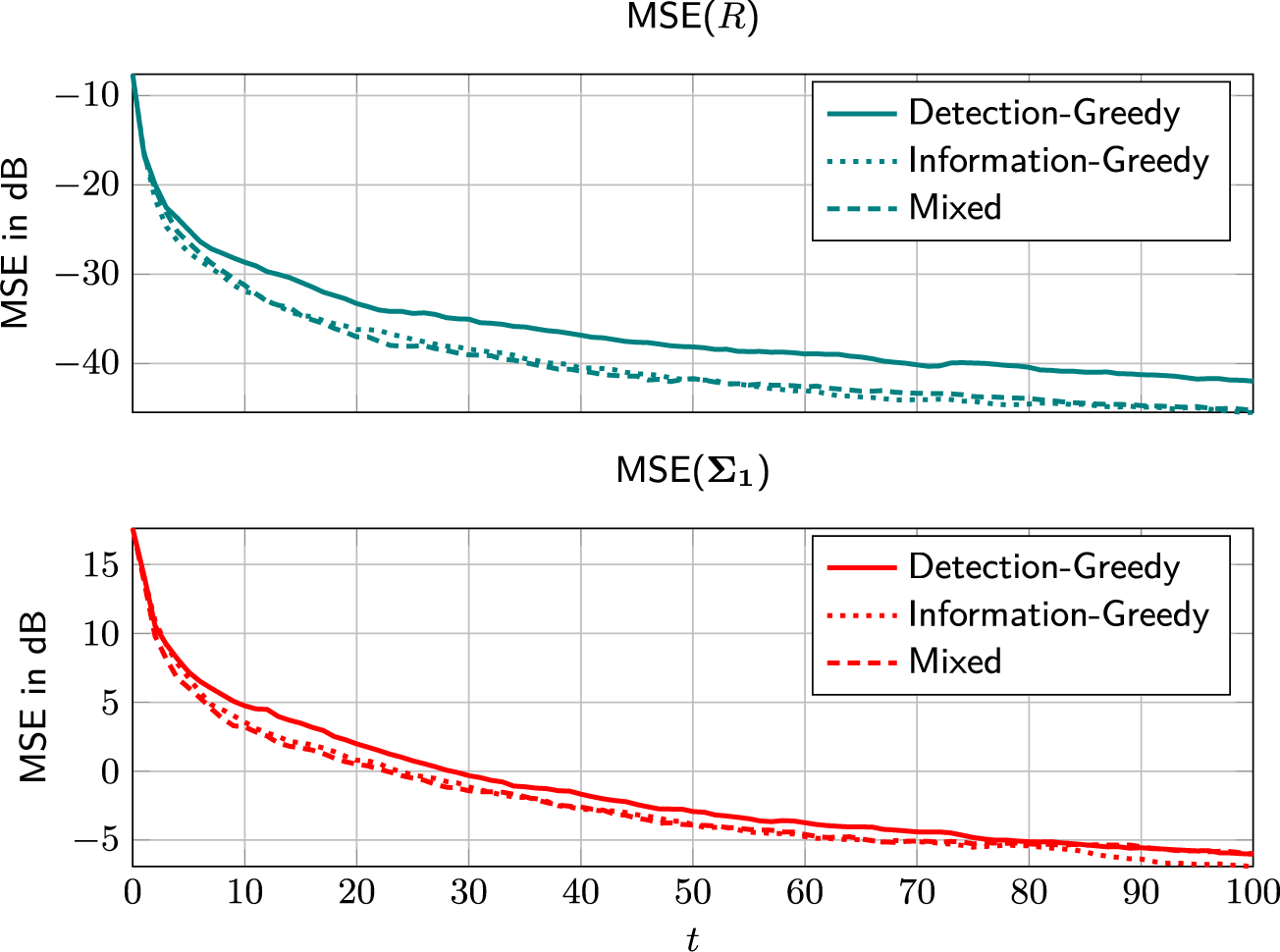

We propose three selection policies: A detection-greedy policy, an information-greedy policy, and a mixed policy that balances the information-greedy and detection-greedy approaches depending on the estimated accuracy of the current model.

4.2.1 Detection-greedy selection policy

Consider the optimal selection policy defined by the optimization problem (9). Adopting a greedy approach and ignoring the expected future rewards, this problem simplifies to

$$ \begin{align} &= \max_{\boldsymbol{s} \in \mathcal{S}_K^N} \; \sum_{n=1}^N s_{t,n} P(C_{t,n} = 1 \,|\, \mathcal{F}_{t-1}'). \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} &= \max_{\boldsymbol{s} \in \mathcal{S}_K^N} \; \sum_{n=1}^N s_{t,n} P(C_{t,n} = 1 \,|\, \mathcal{F}_{t-1}'). \end{align} $$

That is, the optimal greedy selection policy is to select the K test takers with the highest posterior probability of being members of the critical group.

Although the detection-greedy policy is much simpler than the optimal one, evaluating

![]() ${P(C_{t,N} = 1 \,|\, \mathcal {F}_{t-1}')}$

will still be too complex in most practical cases. Therefore, the heuristic policy suggested here is to select test takers based on the approximate probability

${P(C_{t,N} = 1 \,|\, \mathcal {F}_{t-1}')}$

will still be too complex in most practical cases. Therefore, the heuristic policy suggested here is to select test takers based on the approximate probability

![]() $q_{C_{t,n}}(1)$

. This leads to the following selection policy:

$q_{C_{t,n}}(1)$

. This leads to the following selection policy:

Selection Policy 1 (Detection-Greedy).

At time instant t, the detection-greedy selection policy,

![]() $\xi _t^\dagger $

, is defined as

$\xi _t^\dagger $

, is defined as

where

with

![]() $q_{C_{t,n}}(1)$

defined in (38). In words,

$q_{C_{t,n}}(1)$

defined in (38). In words,

![]() $\xi _t^\dagger $

flags the K test takers that are most likely to be members of the critical group according to the approximate posterior probability

$\xi _t^\dagger $

flags the K test takers that are most likely to be members of the critical group according to the approximate posterior probability

![]() $q_{C_{t,n}}(1)$

.

$q_{C_{t,n}}(1)$

.

The detection-greedy policy is a natural choice, and, as the numerical examples in Section 6 will demonstrate, works well in many cases. However, by design, it does not take into account the benefits of potential model improvements that could be achieved by reviewing particularly informative cases. The second policy aims to identify the latter.

4.2.2 Information-greedy selection policy

The idea underlying this selection policy is not to review the cases that are most likely to lead to detections, but to review the cases that provide the most information. In terms of the optimal selection policy in (9), this roughly corresponds to maximizing only the expected reward term,

![]() $\rho _t$

, and ignoring the immediate reward

$\rho _t$

, and ignoring the immediate reward

![]() $\boldsymbol {s}^\intercal \boldsymbol {C}_t$

. In this sense, the information-greedy policy complements the detection-greedy policy. However, as was the case for the latter, directly maximizing

$\boldsymbol {s}^\intercal \boldsymbol {C}_t$

. In this sense, the information-greedy policy complements the detection-greedy policy. However, as was the case for the latter, directly maximizing

![]() $\rho _t$

is computationally infeasible. We propose the following heuristic:

$\rho _t$

is computationally infeasible. We propose the following heuristic:

Selection Policy 2 (Information-Greedy).

At time instant t, the information-greedy selection policy,

![]() $\xi _t^\ddagger $

, is defined as

$\xi _t^\ddagger $

, is defined as

where

![]() $H_b$

denotes the binary entropy function, and

$H_b$

denotes the binary entropy function, and

![]() $q_{C_{t,n}}(1)$

is defined in (37). In words,

$q_{C_{t,n}}(1)$

is defined in (37). In words,

![]() $\xi _t^\ddagger $

flags the K test takers whose approximate posterior group-membership distribution admits the highest entropy.

$\xi _t^\ddagger $

flags the K test takers whose approximate posterior group-membership distribution admits the highest entropy.

The rationale for the information-greedy selection policy is that resolving cases with the highest ambiguity has the greatest effect on model updates. More specifically, in (39)–(41), observed samples contribute to the parameter updates of the posterior distributions with weights

![]() $q_{C_{t,n}}$

. Reviewing cases that are highly likely to belong to a certain group has little effect on these weights. For example, reviewing a case with

$q_{C_{t,n}}$

. Reviewing cases that are highly likely to belong to a certain group has little effect on these weights. For example, reviewing a case with

![]() $q_{C_{t,n}}(1) = 0.99$

will most likely result in a detection, changing the weight from

$q_{C_{t,n}}(1) = 0.99$

will most likely result in a detection, changing the weight from

![]() $0.99$

to

$0.99$

to

![]() $1.0$

. This small change has a negligible impact on the model. In contrast, reviewing cases with high entropy, that is,

$1.0$

. This small change has a negligible impact on the model. In contrast, reviewing cases with high entropy, that is,

![]() $q_{C_{t,n}}(1) \approx 0.5$

, has a strong impact: Without review, the sample contributes equally to both models, reducing separability. With review, it contributes exclusively to the correct model, increasing separability.

$q_{C_{t,n}}(1) \approx 0.5$

, has a strong impact: Without review, the sample contributes equally to both models, reducing separability. With review, it contributes exclusively to the correct model, increasing separability.

On its own, the information-greedy policy is of limited use, as it does not explicitly aim to maximize the number of detections.Footnote 2 However, it serves as a useful building block for an adaptive policy that balances model fit and detection rate (DR). Such a policy is proposed next.

4.2.3 Mixed selection policy

The detection-greedy selection policy is a good choice when the learned model is close enough to the true one to produce sufficiently reliable predictions. However, the information-greedy selection policy might be useful to reduce the time and samples needed to reach this point. The idea underlying the proposed mixed policy is to track the model fit and balance the two policies accordingly. However, quantifying model fit is not straightforward. As discussed before, the optimal measure in (9) is too complex to evaluate in practice. Possible proxy measures include, for example, the variance or entropy of the posterior distribution. However, translating the latter into a useful exploration/exploitation trade-off is a non-trivial problem itself.

The heuristic proposed here is to use the detector calibration as a measure of the model accuracy. The underlying idea is the following: If the learned model is a good fit, the resulting (approximate) posterior probabilities will be reasonably accurate. That is, assuming that the posterior probabilities of the K selected test takers being critical group members are

![]() $q_1, \ldots , q_K$

, the number of critical group members detected in the review process should be close to the sum of these probabilities. More precisely, it should hold that

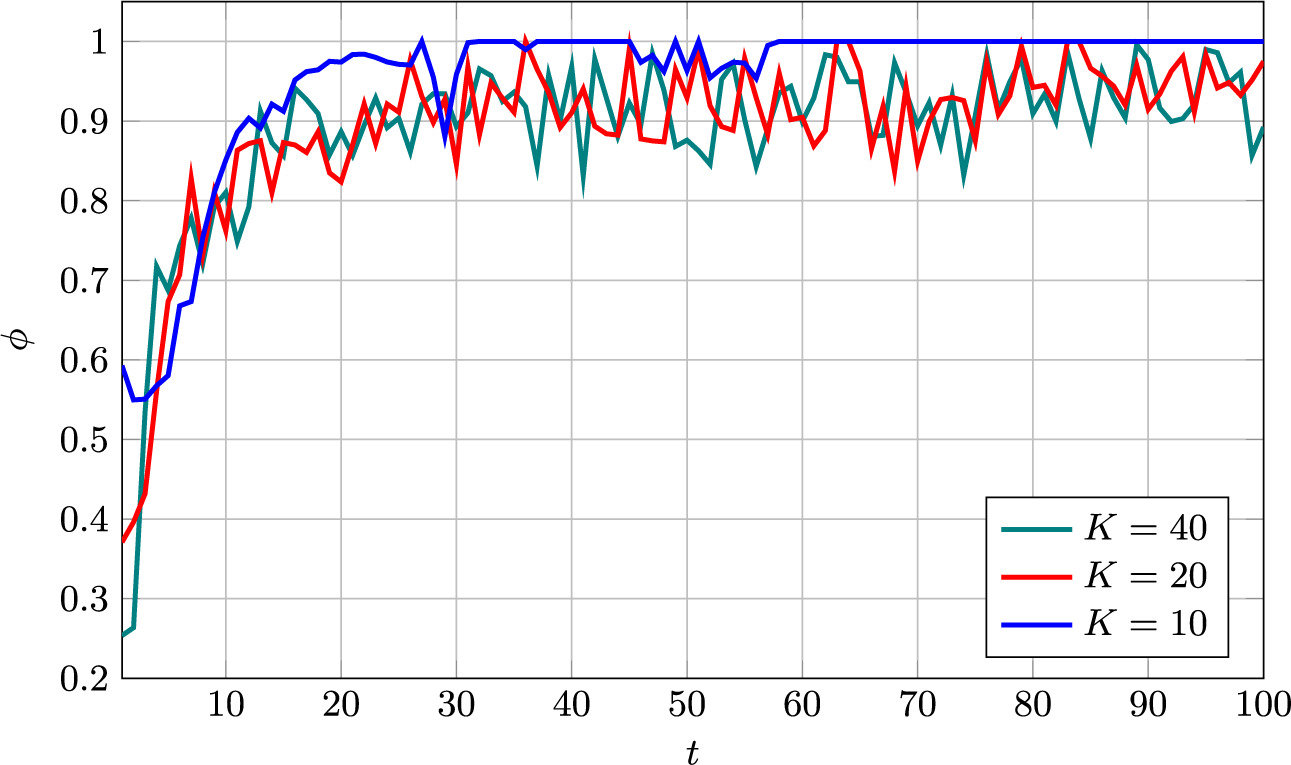

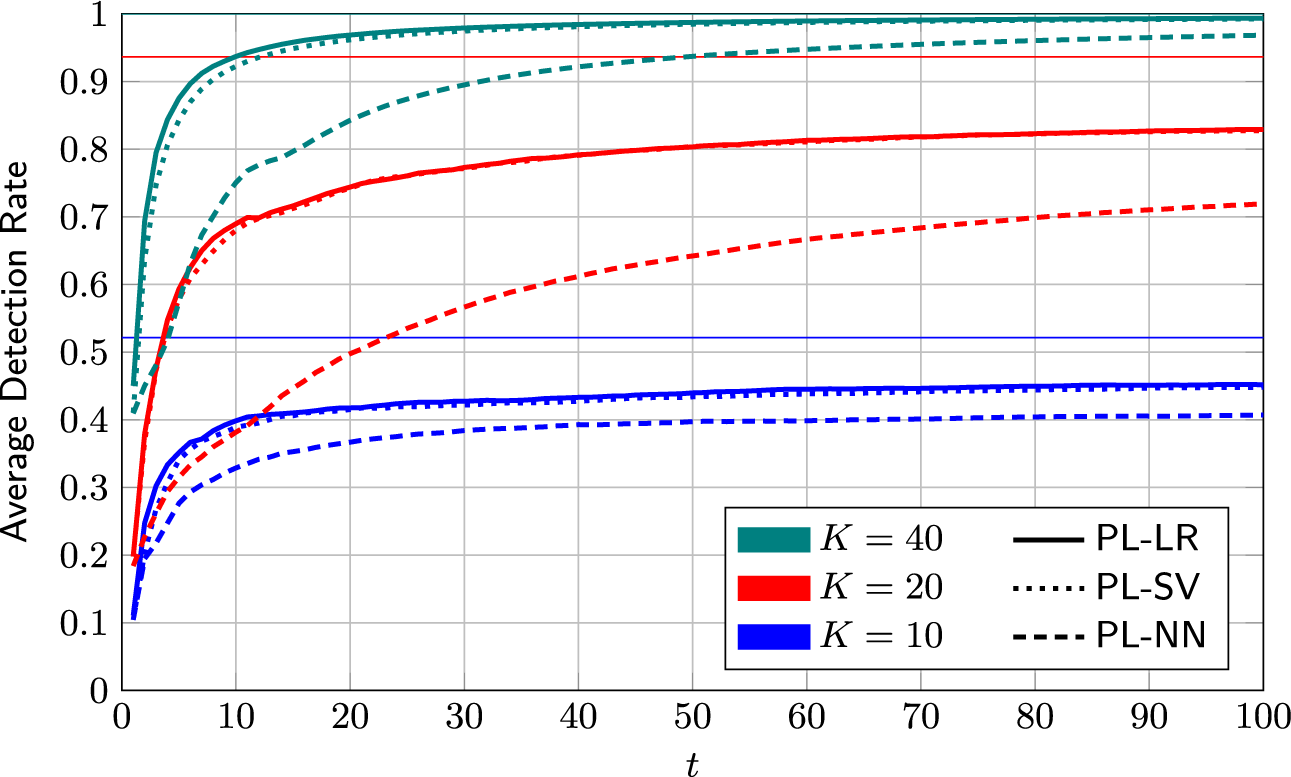

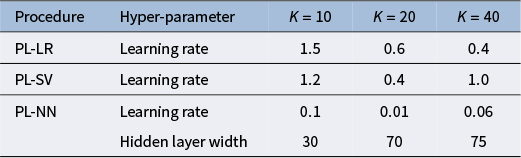

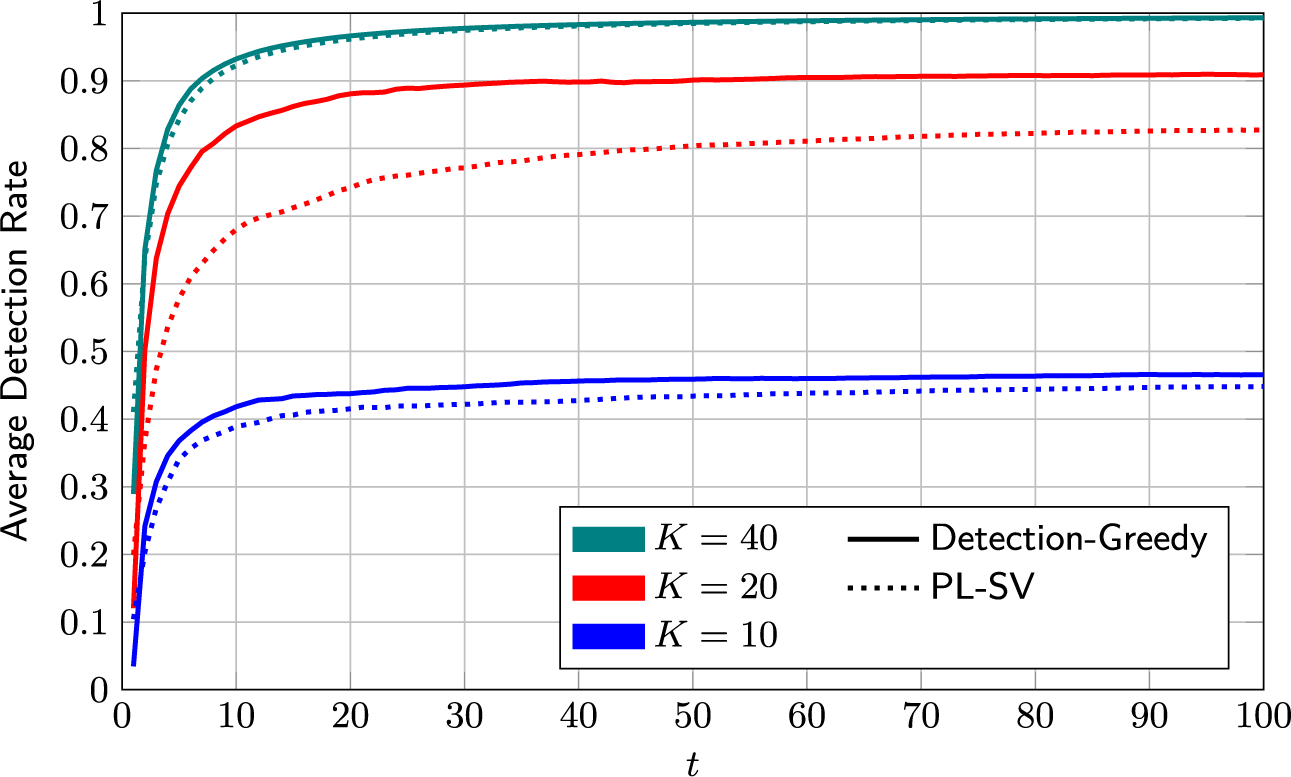

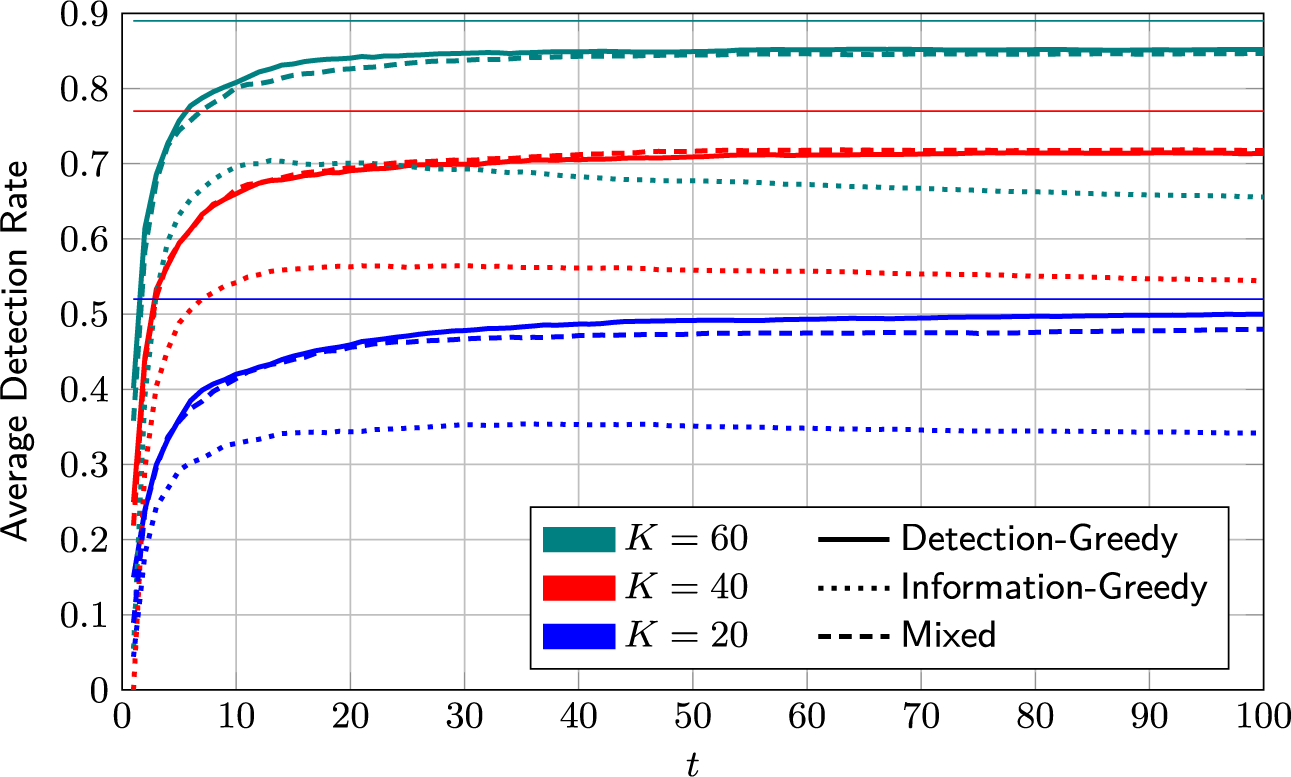

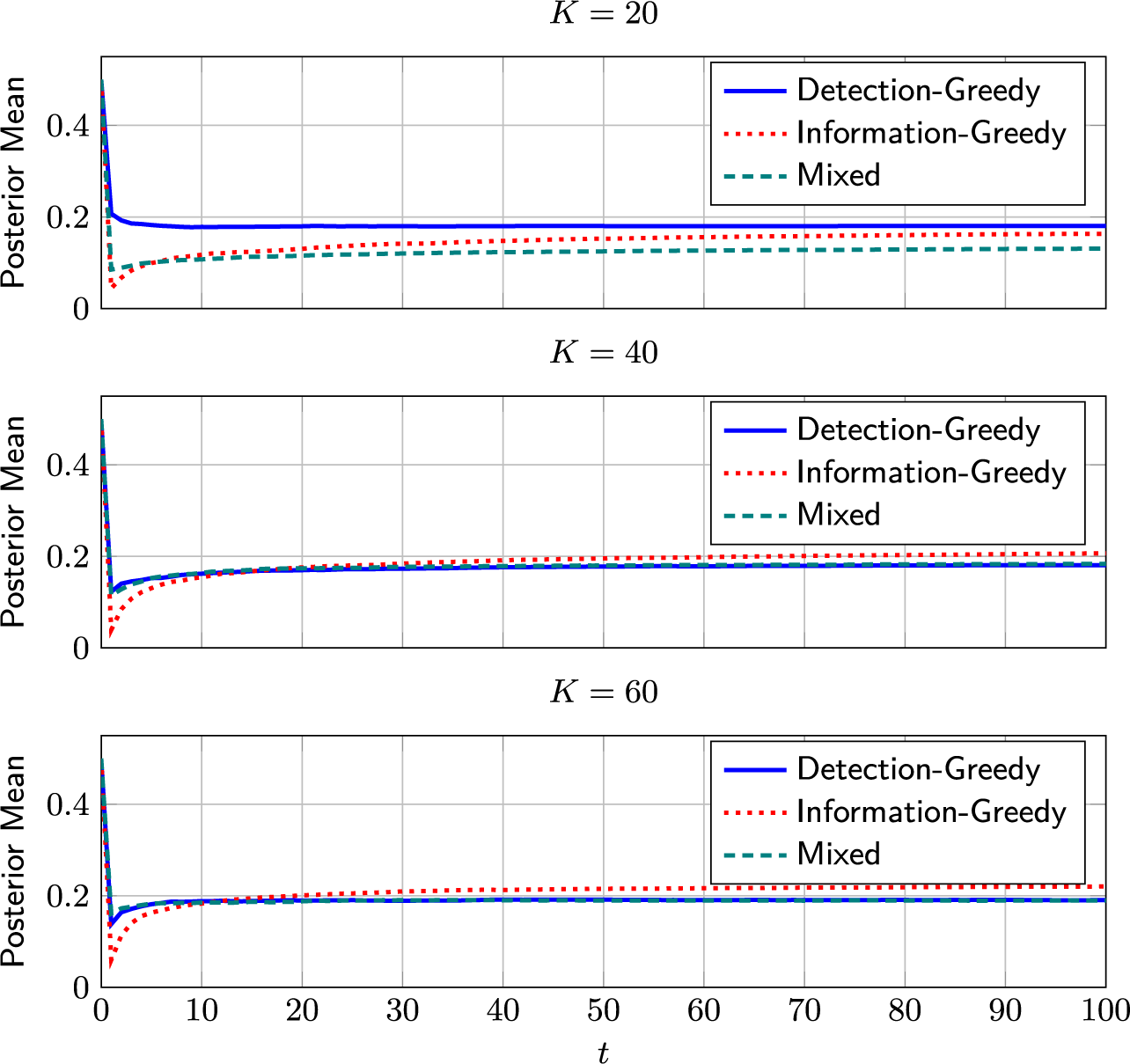

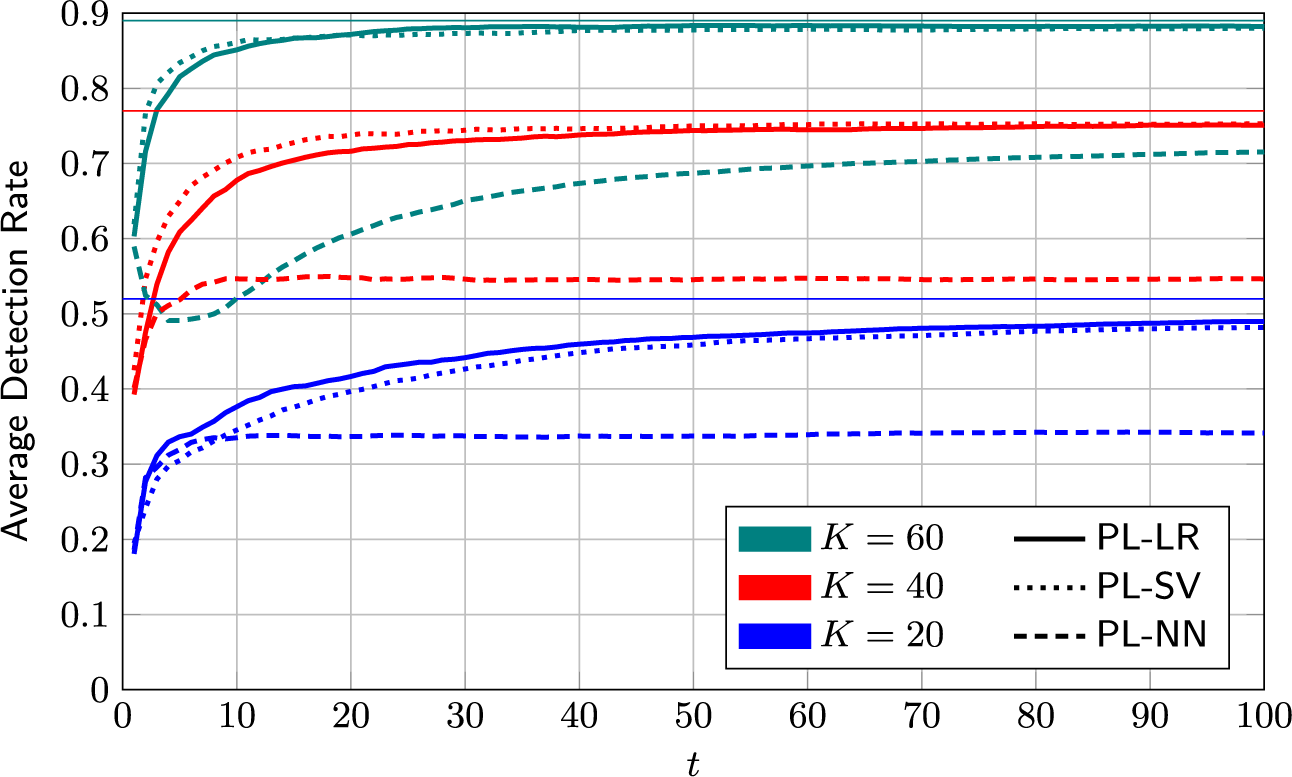

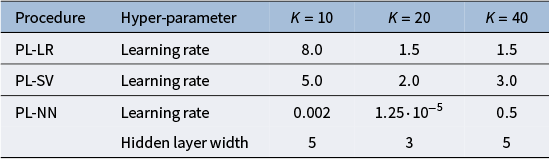

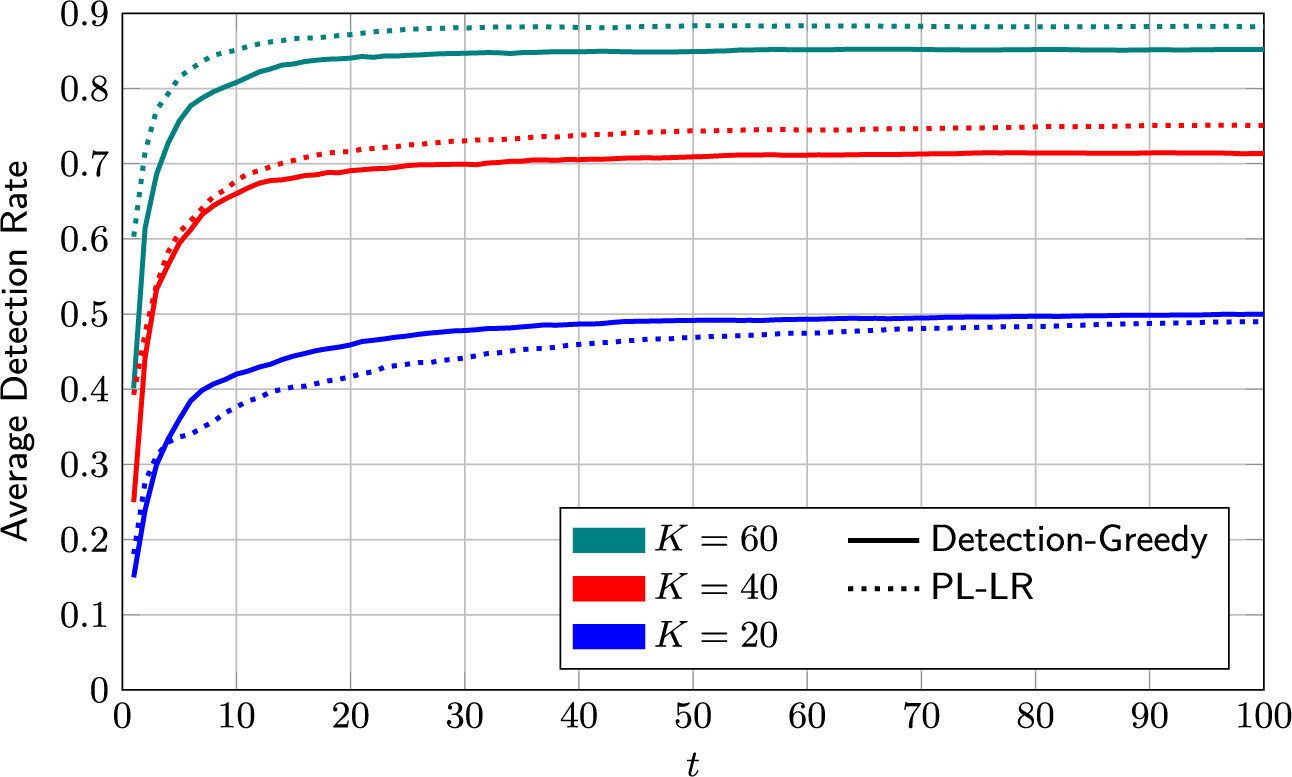

$q_1, \ldots , q_K$