Introduction

Antarctic plants grow at the boundary layer where surface water interacts with the atmosphere. In the Antarctic Peninsula, decadal warming between the 1950s and 1990s (Turner et al. Reference Turner, Colwell, Marshall, Lachlan-Cope, Carleton and Jones2005) had a strong level of control over the spatial extent of vascular plants (Fowbert & Smith Reference Fowbert and Smith1994, Parnikoza et al. Reference Parnikoza, Convey, Dykyy, Trokhymets, Milinevsky and Tyschenko2009, Cannone et al. Reference Cannone, Guglielmin, Convey, Worland and Favero Longo2016). The warming trend shifted to seasonal cooling in the late 1990s (Carrasco Reference Carrasco2013, Turner et al. Reference Turner, Lu, White, King, Phillips and Hosking2016, Oliva et al. Reference Oliva, Navarro, Hrbáček, Hernández, Nývlt and Pereira2017), followed by a return to warming since the mid-2010s (Carrasco et al. Reference Carrasco, Bozkurt and Cordero2021) and further expansion of vascular plants (Cannone et al. Reference Cannone, Malfasi, Favero-Longo, Convey and Guglielmin2022). Less is known about long-term variability and trends in atmospheric moisture, which is transported to the Antarctic Peninsula by meridional circulation and transient cyclones (Naakka et al. Reference Naakka, Nygård and Vihma2021). Since 1850, annual snow accumulation has doubled in West Antarctica, and twenty-first-century snow accumulation amounts have been unprecedented in the context of the past 300 years (Thomas et al. Reference Thomas, Marshall and McConnell2008, Thomas et al. Reference Thomas, Hosking, Tuckwell, Warren and Ludlow2015, González-Herrero et al. Reference González-Herrero, Navarro, Pertierra, Oliva, Dadic, Peck and Lehning2024). In the Antarctic Peninsula, observational data show that the number of days with precipitation increased during the warming trend (~5–12 days per decade during the period 1960–1999; Turner et al. Reference Turner, Colwell, Marshall, Lachlan-Cope, Carleton and Jones2005, Kirchgäßner Reference Kirchgäßner2011), then decreased during the cooling trend (~35 days between 1998 and 2015; Vignon et al. Reference Vignon, Roussel, Gorodetskaya, Genthon and Berne2021). Recent warming has also led to an increase in rainfall relative to snowfall (Kirchgäßner Reference Kirchgäßner2011), which may alter the seasonality and distribution of meltwater available for plants to use (Lee et al. Reference Lee, Waterman, Shaw, Bergstrom, Lynch, Wall and Robinson2022). Water availability has the potential to limit future plant productivity and expansion (Convey et al. Reference Convey, Chown, Clarke, Barnes, Bokhorst and Cummings2014). Although studies of the rate of greening in recent decades show modest change, vegetation is predicted to colonize and expand into new ice-free areas in the Antarctic Peninsula (Cannone et al. Reference Cannone, Malfasi, Favero-Longo, Convey and Guglielmin2022, Roland et al. Reference Roland, Bartlett, Charman, Anderson, Hodgson and Amesbury2024, Colesie et al. Reference Colesie, Gray, Walshaw, Bokhorst, Kerby and Jawak2025).

Stable isotope values in waters and plants are sensitive indicators of hydroclimate conditions (Helliker & Griffiths Reference Helliker and Griffiths2007, Kahmen et al. Reference Kahmen, Sachse, Arndt, Tu, Farrington, Vitousek and Dawson2011, Rundel et al. Reference Rundel, Ehleringer and Nagy2012, Tuthorn et al. Reference Tuthorn, Zech, Ruppenthal, Oelmann, Kahmen and del Valle2015, Dee et al. Reference Dee, Bailey, Conroy, Atwood, Stevenson, Nusbaumer and Noone2023) and provide a signature of the biological and chemical processes in the environment (Fry Reference Fry2006). Isotopes are versions of an element that differ in number of neutrons, resulting in differences in their masses. Due to these differences, the heavy and light stable isotopes have different kinetic properties under different biophysical settings (Bigeleisen & Mayer Reference Bigeleisen and Mayer1947, Urey Reference Urey1947). For example, the light stable isotope of oxygen (16O) has weaker bonds and moves faster than the heavier stable isotope of oxygen (18O), and isotopically light water tends to evaporate more readily under the same environmental conditions. The stable isotopic composition in meteoric waters and plants can be used to track the source of water a plant uses for photosynthesis (Ehleringer & Dawson Reference Ehleringer and Dawson1992). Tracking source waters is possible in part because the global relationship between oxygen and hydrogen stable isotope ratios of precipitation varies with temperature, rainfall amount, elevation and distance to the coast (Dansgaard Reference Dansgaard1953, Craig Reference Craig1961, Bowen Reference Bowen2010). Site-specific fractionation processes (i.e. evaporation) also affect the isotopic composition of precipitation and surface waters (Rozanski et al. Reference Rozanski, Araguás-Araguás and Gonfiantini1993, Sprenger et al. Reference Sprenger, Leistert, Gimbel and Weiler2016, Putman et al. Reference Putman, Bowen and Strong2021). As a result, regional-to-local hydroclimate determines the isotopic composition of plant-available water, which eventually becomes imprinted in plant tissues.

In the Antarctic Peninsula, poikilohydric mosses are the primary contributors to the formation of aerobic peat deposits referred to as ‘moss banks’ (Fenton & Smith Reference Fenton and Smith1982). This study focuses on the primary bank-forming mosses Chorisodontium aciphyllum and Polytrichum strictum. Their large structure and physiology promote water retention (e.g. thick multicellular leaves and the three-dimensional structure of Polytrichum). Smaller species and shallower, looser carpets probably dry out faster, such as the vegetation that dominates non-moss-bank communities in the Antarctic Peninsula (Convey et al. Reference Convey, Chown, Clarke, Barnes, Bokhorst and Cummings2014) as well as in East Antarctica (Robinson et al. Reference Robinson, Wasley, Popp and Lovelock2000, Reference Robinson, King, Bramley-Alves, Waterman, Ashcroft and Wasley2018).

Moss banks have been used to reconstruct changes in temperature, water availability and water sources over the past 5000 years in the Antarctic Peninsula (Björck et al. Reference Björck, Malmer, Hjort, Sandgren, Ingólfsson and Wallén1991, Royles et al. Reference Royles, Ogée, Wingate, Hodgson, Convey and Griffiths2012, Amesbury et al. Reference Amesbury, Roland, Royles, Hodgson, Convey, Griffiths and Charman2017, Stelling et al. Reference Stelling, Yu, Loisel and Beilman2018) and over the last century in East Antarctica (Clarke et al. Reference Clarke, Robinson, Hua, Ayre and Fink2012, Robinson et al. Reference Robinson, King, Bramley-Alves, Waterman, Ashcroft and Wasley2018). Oxygen stable isotopes (δ18O) of moss α-cellulose in moss-bank peat are regarded as palaeoclimate proxies because of their sensitivity to environmental change such as warming temperatures, source waters used in photosynthesis and surface wetness conditions (Royles et al. Reference Royles, Sime, Hodgson, Convey and Griffiths2013, Royles et al. Reference Royles, Amesbury, Roland, Jones, Convey and Griffiths2016, Yu et al. Reference Yu, Beilman and Loisel2016, Stelling & Yu Reference Stelling and Yu2019). Values of δ18O in Antarctic moss waters correlate with a latitudinal gradient in precipitation, but local factors such as wind exposure, geography and species may further affect source water signals (Gimingham & Smith Reference Gimingham and Smith1971, Royles et al. Reference Royles, Sime, Hodgson, Convey and Griffiths2013, Reference Royles, Amesbury, Roland, Jones, Convey and Griffiths2016). Topography modulates surface irradiance across slope and aspect and can influence the availability of water via evaporation, as well as the δ18O values of waters (Lachniet et al. Reference Lachniet, Moy, Riesselman, Stephen and Lorrey2021) and vegetation (Quadri et al. Reference Quadri, Silva and Zavaleta2021). A previous field survey of moss waters collected over two seasons found a similar isotopic range within sites as between sites spanning 600 km of latitude (Royles et al. Reference Royles, Amesbury, Roland, Jones, Convey and Griffiths2016). These authors suggest that this similarity was driven by evaporative enrichment from slope aspect and wind exposure, but this has not been explicitly demonstrated.

This study aims to evaluate the effects of evaporative conditions and topographic setting on the oxygen isotope composition of moss waters and cellulose across multiple sites during a single short season. We also aim to directly evaluate whether topography of contrasting slope aspects results in significantly different isotopic environments. Determining the influence of non-climatic variables on the isotopic values of poikilohydric mosses (which are unable to regulate water content and readily equilibrate with environmental conditions) would allow better anticipation of plant responses to the changing Antarctic environment, as well as the interpretation of palaeoclimate proxies.

Methodology

We sampled with ship support from the RV Laurence M. Gould (LMG; cruise no. LMG20-02) over 3 weeks from 16 February 2020 to 20 March 2020 at 14 study sites: Coppermine and Edwards peninsulas on Robert Island, Byers Peninsula on Livingston Island, Cierva Cove, Moss Island, Apendice Island, Charles Point, Pi Island, Tau Island, Island 395 near Cape Monaco on Anvers Island, Norsel Point on Amsler Island, Litchfield Island, Cape Rasmussen, Cape Tuxen, Berthelot Island and Cape Perez (Fig. 1a). These sites span 400 km from 62.4°S to 65.4°S along the western Antarctic Peninsula region at 4–237 m elevation above sea level (Table S1).

Figure 1. a. Field sites and locations mentioned in the Antarctic Peninsula and the RV Laurence M. Gould (LMG) sea-path. b. δ18O and δ2H (‰; Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water (VSMOW)) isotope values in Antarctic moss leaf tissue water for two species (Polytrichum strictum and Chorisodontium aciphyllum), surface waters and snow collected in February–March 2020 in the South Shetland Islands (SSI) and Antarctic Peninsula (AP). Regression lines for P. strictum and C. aciphyllum show evaporative enrichment relative to local surface waters and snow. δ18Omw (green bars) are plotted along with δ18O of water and snow (blue bars) as a histogram. The local meteoric water line (LMWL) is constructed from isotopes in precipitation from Vernadsky Station from 1964 to 2021. Data last accessed 2 January 2024 from Global Network of Isotopes in Precipitation (https://nucleus.iaea.org/wiser). Map data from the Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research, Antarctic Digital Database, 2024.

Environmental water collections

Environmental water samples (n = 37) of standing water and snow were collected opportunistically at 14 sites. The δ18O and δ2H stable isotope values of water samples were measured at the University of Utah Stable Isotope Ratio Facility for Environmental Research lab (SIRFER; Salt Lake City, UT, USA) and the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa using a laser water isotope analyser (Picarro L2130-i Analyzer). Internal quality assurance and quality control working standards (PLRM-1, PLRM-2 and SLRM) were calibrated against International Atomic Energy Agency international standards Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water (VSMOW) and had an analytical precision typically better than 0.3‰ and 2.2‰ for δ18O and δ2H, respectively. δ18O and δ2H isotopic analyses of waters were analysed in triplicate and reported with respect to VSMOW.

Moss field collection and moss waters

We targeted collections of Polytrichum strictum Menzies ex Brid. and Chorisodontium aciphyllum (Hook.f. & Wilson) Broth., two dominant species that also form moss banks in the Antarctic Peninsula region. The top 1 cm of the moss surfaces were collected from patches of continuous vegetation, placed in 12 ml Exetainer vials (Labco, Lampeter, UK) and frozen until analysis. Recent moss growth rates of up to 4.1 mm per year have been reported (Amesbury et al. Reference Amesbury, Roland, Royles, Hodgson, Convey, Griffiths and Charman2017), thus 1 cm surface samples represent a multi-year integrated signal of 1–3 years of photosynthesis. Moss tissue waters were extracted for δ18O and δ2H stable isotope analysis via cryogenic extraction at the SIRFER laboratory at the University of Utah. Extracted water samples were then analysed in the same way as the environmental water samples. We used an internal control of the LMG laboratory waters to evaluate whether sample waters were compromised during sample freezing (-80°C) and shipping. The δ18O and δ2H stable isotope analyses of three test samples indicated that evaporative enrichment of samples did not occur during transit (Table S2). We also internally evaluated the δ18Omw results by testing associations between δ18Omw and the day of the year when the sample was collected as a proxy for the total amount of time elapsed for evaporation during the growing season.

Moss cellulose extraction and isotope analyses

Using ~200 moss leaves per sample for extraction and purification of α-cellulose, we followed an adapted version of the procedure by Loader et al. (Reference Loader, Robertson, Barker, Switsur and Waterhouse1997). As indicators of purity of the α-cellulose, we visually inspected and performed an analysis of nitrogen content (percentages were below detectability) and carbon content (40.9–45.7%). As an internal quality control, we used samples of pure α-cellulose (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) throughout all procedural steps. The δ18O of α-cellulose for the internal quality control samples varied by 0.1‰. δ18O stable isotope ratios of α-cellulose samples were measured at the University of Wyoming Stable Isotope Facility (UWSIF). Oxygen was analysed using a thermal conversion elemental analyser (TCEA) coupled to a Thermo Delta V isotope ratio mass spectrometer (IRMS); δ18O values are expressed relative to VSMOW (Craig Reference Craig1961, Gonfiantini Reference Gonfiantini1978). Values were normalized to the VSMOW scale using UWSIF-USFS 43, IAEA 601 (benzoic acid), IAEA 602 (benzoic acid) and 312-UWSIF-cellulose (acceptable range of 30.0–31.4‰) quality control standard reference materials for oxygen isotopic composition. Analytical precision was ± 0.3‰ for δ18O based on repeated analysis of internal standards. Samples loaded into silver capsules had weights of ~0.18–0.25 mg.

Temperature and relative humidity observations

During our sampling campaign, the LMG measured meteorological variables along a latitudinal sea-path spanning three degrees of latitude. Temperature and relative humidity measurements were made over the duration of sample collection using a Rotronic HygroClip HC2A-S3 (Rotronic AG, Bassersdorf, Switzerland) calibrated on 13 June 2018. Observations used to quantify the average daytime temperature and relative humidity prior to sample collection were selected using a hybrid time and geographical-location approach. For the start time of each sampling day, we used daytime observations of temperature and relative humidity that coincide with pyranometer observations that were > 20 W/m2 (LI-COR model LI-200SA pyranometer). Observations were collected over ~4.5–12 h within a range of 0.9–18.5 km from moss sampling sites (Figs S1 & S2 & Table S3). The end time for the daytime observations was the time of sample collection. Daily average values for temperature and relative humidity were calculated from 1 min observations. We evaluated the relationship between daytime relative humidity and moss water stable isotopes (Carleton & Dunham Reference Carleton and Dunham2003, Price et al. Reference Price, Edwards, Yi and Whittington2009, Wu et al. Reference Wu, Kutzbach, Jager, Wille and Wilmking2010). The dataset from the LMG cruise LMG20-02 (cruise DOI:10.7284/908802) is available from the Antarctic Data Repository (https://www.rvdata.us/search/cruise/LMG2002).

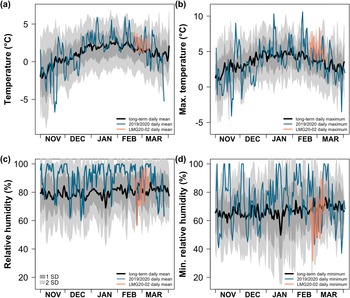

To put the 2020 field season into context and validate measurements made along the sea-path, we compared the ship observations with 2 min observations of temperature and relative humidity made from 1 November 2002 to 31 March 2017 at Gamage Point (Station #100) on Palmer Station (PalMOS AWS), representing a stationary, terrestrial record. This period includes some of the warmest years in the long-term observations at multiple Antarctic Peninsula stations (Turner et al. 2020). Observations after March 2017 were not included in the climatology because of a change in station location and the retiring of equipment. We removed erroneous 1 min observations of temperature and relative humidity based on anomalous departures in the data and an evaluation of surrounding timepoints. We calculated a long-term mean and standard deviation for each day of the year during the growing season months of November–March (2002–2017 PalMOS, measured at 8 m elevation). We used observations from a nearby station (Palmer Station Automated Weather Data System (PAWS); ~40-m elevation) to calculate the daily mean for our field campaign season of 1 November 2019–31 March 2020 (Fig. 2) at Palmer Station. The datasets from Palmer Station can be retrieved from https://amrdcdata.ssec.wisc.edu/dataset?q=Palmer+Station.

Figure 2. Temperature and relative humidity observations from Palmer Station and the RV Laurence M. Gould. The long-term data span November 2002–March 2017 from the automated weather station on Gamage Point, Anvers Island (2002–2017, PalMOS). Daily a. mean temperature, b. maximum temperature, c. mean relative humidity and d. minimum relative humidity are shown for the long-term dataset and the 2019–2020 November–March season. The November 2019–March 2020 data are from the Palmer Station Automated Weather Data System (PAWS).

Topographic variables

We explored the topographic aspect and slope at each moss sample location as proxies for irradiance and wind exposure. For each moss sample we estimated the topographic aspect and slope using the 2 m spatial resolution Reference Elevation Model of Antarctica Explorer (Howat et al. Reference Howat, Porter, Noh, Husby, Khuvis, Danish and Morin2022; https://rema.apps.pgc.umn.edu/) from the Polar Geospatial Center. Because aspect values are circular, they were converted to linear variables of north-exposedness (cosine of aspect) and west-exposedness (-sin of aspect) for analysis.

Statistical analysis

We tested for normality using a Shapiro-Wilk test (P < 0.05 was considered non-normal). Not all variables met the assumption of normality, and for consistency we used a Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (ρ) for all correlations in base R (R Core Team 2023).

Results

During sample collection days (calendar day of the year: 52–70), the LMG mean daily air temperature ranged from 1.2°C to 3.9°C (mean = 1.9°C ± 0.7°C; Fig. 2a). Using Palmer Station observations, the daily maximum air temperature during the 2019–2020 November–March season (PAWS) exceeded two standard deviations of the long-term daily maximum temperature (2002–2017 PalMOS) on 4 different days prior to sample collection days (Fig. 2b). The LMG daily mean relative humidity ranged from 50% to 100% (mean = 81% ± 14%; Fig. 2c), and the daily minimum relative humidity ranged from 37% to 100% (Figs 2d & S1). During the same time frame, the Palmer Station daily mean relative humidity ranged from 57% to 100% (mean = 89% ± 13%; Fig. 2c), and the daily minimum relative humidity ranged from 43% to 100% (Fig. 2d). The LMG and Palmer Station daily mean relative humidity data were significantly positively correlated (n = 19, ρ = 0.670, P = 0.002), as were the daily minimum relative humidity data (n = 19, ρ = 0.611, P = 0.005).

The δ18O values of environmental water samples ranged from −12.1‰ to −5.2‰ (mean = −9.4‰ ± 1.8‰; Table S2), whereas the δ18O values of moss tissue waters (hereafter, δ18Omw) ranged from −10.6‰ to 0.6‰ (Table S1), indicating enrichment relative to environmental waters. This δ18Omw enrichment was not a function of the total amount of time elapsed for evaporation during the growing season (ρ = −0.160, P = 0.325; Fig. S3a). The δ18Omw values diverged from both the surface water line in this study and from the Vernadsky Station local meteoric water line (Fig. 1b), showing substantial evaporative enrichment.

We found significant negative correlations between δ18Omw and mean relative humidity when considering both species together (n = 40, ρ = −0.525, P < 0.001) and individually (P. strictum: n = 24, ρ = −0.578, P = 0.003; C. aciphyllum: n = 16, ρ = −0.509, P = 0.044; Fig. 3a). We found no significant correlations between δ18Omw and mean air temperature when considering species together (ρ = −0.076, P = 0.640) or individually (P. strictum, ρ = −0.073, P = 0.734; C. aciphyllum, ρ = −0.237, P = 0.376).

Figure 3. a. Correlation between moss water stable oxygen isotope values (δ18Omw) and daytime relative humidity prior to collection of the two species Polytrichum strictum (pol) and Chorisodontium aciphyllum (cho) in the South Shetland Islands (SSI) and Antarctic Peninsula (AP). b. Significant positive correlation between δ18Omw and δ18Oc and c. positive correlation between δ18Oc and topographic aspect (north-exposedness, cosine of aspect). VSMOW = Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water.

Across all sites and species, measurements of oxygen stable isotope values in moss cellulose (hereafter, δ18Oc) ranged from 24.5‰ to 30.9‰ (mean = 28.0‰ ± 1.62‰). We found significant positive correlations between δ18Oc and δ18Omw when considering both species together (ρ = 0.397, P = 0.011) and individually (P. strictum, ρ = 0.533, P = 0.007; C. aciphyllum, ρ = 0.528, P = 0.126). The enrichment factor ε(18Oc-mw) is the difference between δ18Oc and δ18Omw and ranged from 25.2‰ to 38.6‰.

Regarding topography, across the sampling sites we found negative correlations between δ18Omw and topographic slope (0° (flat)–33°) when considering both species (ρ = −0.319, P = 0.045) but not individually (Fig. S3c). We found no significant correlations between δ18Oc and slope (Fig. S3f). We found a positive correlation between δ18Omw and north-exposedness when considering both species together (+1 is north and −1 is south; ρ = 0.569, P < 0.001) and individually (P. strictum, ρ = 0.441, P = 0.031; C. aciphyllum, ρ = 0.730, P = 0.001; Fig. S3d). We found no significant correlations between δ18Omw and west-exposedness (Fig. S3b). Similarly to δ18Omw, δ18Oc and north-exposedness were positively correlated when considering both species (ρ = 0.579, P < 0.001) and individually (P. strictum, ρ = 0.631, P < 0.001; C. aciphyllum, ρ = 0.555, P = 0.026; Fig. 3c). We found no significant correlations between δ18Oc and west-exposedness (Fig. S3e).

Despite a latitudinal range of three degrees (62.4–65.4°S) and 400 km, we found no correlations between latitude and δ18Omw when considering both species together (ρ = 0.166, P = 0.306,) or individually (P. strictum, ρ = 0.146, P = 0.497; C. aciphyllum, ρ = 0.198, P = 0.462). Similarly, we found no correlations between latitude and δ18Oc when considering both species together (ρ = 0.216, P = 0.180) or individually (P. strictum, ρ = −0.003, P = 0.990; C. aciphyllum, ρ = 0.455, P = 0.077).

Discussion

Evaporative conditions during the 2019–2020 summer in the Antarctic Peninsula exerted a strong influence on the isotopic composition of moss waters (Fig. 1b). Maximum temperatures were significantly higher and minimum relative humidity was lower during the sampling period compared to the long-term average (2002–2017; Fig. 2). The correlation between relative humidity and δ18Omw (Fig. 3a) supports previous work showing that relative humidity is an important controlling factor of δ18Omw enrichment, but in higher plants with stomata (Helliker & Griffiths Reference Helliker and Griffiths2007, Kahmen et al. Reference Kahmen, Sachse, Arndt, Tu, Farrington, Vitousek and Dawson2011). We interpret this relationship as a demonstration that the broader atmospheric conditions establish the temperature and moisture gradients that are further affected by local factors such as topography at finer scales. Thus, leaf surface conditions should also be influenced by the local atmospheric state.

The positive correlation between δ18Omw and δ18Oc (Fig. 3b) suggests that evaporative conditions can have an imprint on moss stable isotope composition. Although the conditions in the Antarctic Peninsula are typically cool, cloudy and maritime, observed moss surface temperatures can be as warm as ~30°C (Perera-Castro et al. Reference Perera-Castro, Waterman, Turnbull, Ashcroft, McKinley and Watling2020). Royles et al. (Reference Royles, Amesbury, Roland, Jones, Convey and Griffiths2016) suggested a modest evaporative enrichment in δ18Omw (moss water slope of 6.7) compared to δ18O in surface waters (slope of 7.3) collected during two summers in 2012 and 2013 in the Antarctic Peninsula. Our data reveal substantially greater enrichment (moss water slopes of ~4.0 and ~3.4 when excluding South Shetland Islands (SSI) samples) relative to snow (slope of 8.5) and standing water (slope of 7.9) during the summer of 2020, as well as the Vernadsky local meteoric water line (slope of 6.7; Fig. 1b) and other long-term monitoring at Rothera (slope of 7.2) and Halley (slope of 7.9) stations in Antarctica (Putman et al. Reference Putman, Fiorella, Bowen and Cai2019). Our ε(18Oc-mw) range was narrower than the range of values reported by Royles et al. (Reference Royles, Amesbury, Roland, Jones, Convey and Griffiths2016), and our mean of 32‰ ± 3‰ indicates enrichment based on the theoretical cellulose enrichment factor of 27‰ ± 3‰ (Barbour Reference Barbour2007, Sternberg & Ellsworth Reference Sternberg and Ellsworth2011).

The relationship between aspect (north-exposedness) and δ18Omw and δ18Oc reflects differences in shortwave irradiance on equatorward-facing slopes (north) vs poleward-facing slopes (south). More enriched δ18Omw and δ18Oc occur on north-facing aspects and more depleted δ18Omw and δ18Oc occur on south-facing aspects, which tend to be cooler and more humid (Boyko Reference Boyko1947, Quadri et al. Reference Quadri, Silva and Zavaleta2021). Previous findings show that microclimate drives different evaporation rates in mosses (Heijmans et al. Reference Heijmans, Arp and Chapin2004). In addition, mosses growing on contrasting aspects may have different source waters (Royles et al. Reference Royles, Amesbury, Roland, Jones, Convey and Griffiths2016). For example, meltwater from snowpack, which persists longer during the melt season on poleward-facing slopes, is more depleted than summer precipitation (Fig. 1b). It has also been hypothesized that differences in meltwater isotopes in snowpack on contrasting aspects can be affected by differences in ablation and resulting fractionation (Dietermann & Weiler Reference Dietermann and Weiler2013). Mosses growing on equatorward-facing slopes are subject to greater irradiance, leaf water loss and evaporative enrichment and are assumed to use more enriched summer precipitation as a source of water. In contrast, depleted δ18Omw and δ18Oc are found on poleward-facing slopes (south), where source water input throughout the summer probably comes from more depleted sources of water such as snowmelt runoff from snowpack.

Additionally, the relationship between δ18Omw and slope inclination suggests that more evaporatively enriched δ18Omw occur on lower-angle slopes and more depleted δ18Omw occur on steeper-angle slopes (Fig. S3c,f). This pattern may reflect sample proximity to isotopically depleted snowmelt source waters on steeper slopes, where snowpack accumulates and persists through the summer season (depending on slope aspect). One potential reason for the depleted δ18Omw values on steeper slopes is the differences in soil moisture and temperature based on differences in irradiance between flat and steep surfaces, in which the latter receive a greater intensity of energy at the surface (irradiance) than lower-angled slopes.

We found no relationship between elevation and δ18Oc (r = −0.201, P = 0.598), unlike other studies over wider elevation gradients in which δ18Oc decrease with elevation, but only for some plant species (Ménot-Combes et al. Reference Ménot-Combes, Burns and Leuenberger2002).

The isotopic composition of δ18Omw represents a snapshot in time of recent evaporative conditions, and the δ18Omw of SSI samples seemed to be affected by recent and direct meteoric water input (Fig. 1b). The isotopic composition of δ18Oc constitutes an integrated signal reflecting the microclimate growing conditions over time as modulated by topographic aspect and slope. The δ18Oc values in our study probably represent a multi-year integrated signal of the evaporative conditions rather than a more instantaneous reflection of the environmental conditions during the day of sampling, as with δ18Omw. The positive correlation between δ18Oc and δ18Omw suggests that the relative humidity (evaporative conditions) imprints on cellulose but is also affected by topographically mediated microclimate. This imprint is a useful tool for studying sub-fossil moss cellulose and reconstructing the past ecology and climate conditions of the Antarctic Peninsula. By quantifying the relationship between moss leaf water and cellulose with environmental conditions, we provide a better understanding of the role the atmospheric conditions, as well as the confounding role of topographic context and the importance of site selection for palaeoecological and palaeoclimate studies using moss banks.

Conclusion

High evaporative environmental conditions lead to humidity-dependent evaporative effects on the δ18O of moss waters and α-cellulose. Furthermore, microclimate associated with topography is an important and predictable determinant of hydroecology and the oxygen isotope ratios of moss waters and α-cellulose. These findings highlight the use of stable isotope values in α-cellulose for ecological studies investigating water availability and net primary productivity in ice-free terrestrial ecosystems and palaeoclimate studies.

Supplementary material

Three tables and three figures are in the supplementary document at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954102025100485.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the assistance of Danielle B. Jones, Robert K. Booth, Derek J. Ford, Cara Ferrier and the crew of the RV Laurence M. Gould.

Financial support

This work is funded by US National Science Foundation (NSF) awards NSF-2012247 to DVG and NSF-1745082 to DWB.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the Supplementary Material and are referenced in the main text.

Author contributions

All work on this project, including design, data collection and analysis and manuscript writing, was conducted by DVG and DWB.