1. Introduction

Any model attempting to describe the housing market must include two essential features: search and matching frictions and entry of both buyers and sellers. Search frictions are necessary to capture that it takes time for buyers to find a suitable house and for sellers to find a buyer, i.e. that search is a costly and time-consuming process. The large fluctuations in time to sell, the co-movement between houses for sale and time-to-sell, and the large dispersion in prices even after controlling for housing observables (Kotova and Zhang, Reference Kotova and Zhang2020) are all clear indications of the presence of search frictions in the housing market. Less known is the fact that entry of both buyers and sellers is essential to account for the key stylized facts in the housing market: prices are positively correlated with sales and vacancies (i.e. houses for sale), but negatively correlated with time-to-sell. In other words, when house prices are high many houses are listed for sale, there is a high volume of sale transactions, and houses sell fast. As Gabrovski and Ortego-Marti (Reference Gabrovski and Ortego-Marti2019) and Gabrovski and Ortego-Marti (Reference Gabrovski and Ortego-Marti2024) show, these stylized facts imply that the Beveridge Curve (i.e. the correlation between buyers and vacancies) in the housing market is upward sloping.Footnote 1 Search models of the housing market without an endogenous entry of both buyers and sellers generate a counterfactual downward-sloping Beveridge Curve and are unable to match the sign of the correlations between prices, sales, time-to-sell and vacancies (Gabrovski and Ortego-Marti, Reference Gabrovski and Ortego-Marti2019).

These two essential characteristics of the housing market, search and matching frictions and the endogenous entry of buyers, lead to two externalities. The first externality encapsulates both congestion and market thickness externalities that arise in markets with search frictions (Hosios, Reference Hosios1990; Pissarides, Reference Pissarides2000). When a seller posts a vacancy, she does not internalize that by doing so she is making it harder for other sellers to find a buyer (congestion externality) while making it easier for buyers to find a home (thick market externality).Footnote 2 Absent the endogenous entry of buyers, the efficient allocation is restored if the Hosios-Mortensen-Pissarides (HMP) condition holds, i.e. if the bargaining power of buyers equals the elasticity of the matching rate. Under this condition, the congestion and thick market externalities fully offset each other. However, the equilibrium is not efficient even under the HMP condition because the endogenous entry of buyers leads to an additional participation externality.

This paper studies efficiency in the housing market in the presence of both congestion and participation externalities. In addition, using empirical evidence on the housing market we ask the following question: how far is the housing market from the optimal allocation? To answer these questions, we develop a search and matching model of the housing market with an endogenous entry of both buyers and sellers similar to Gabrovski and Ortego-Marti (Reference Gabrovski and Ortego-Marti2019), in which entry is driven by rising search costs as more buyers enter the market. The additional participation externality arises because buyers do not internalize that by entering the market they raise other buyers’ costs.

We begin by characterizing the decentralized equilibrium. We then study the social planner’s problem and find the optimal allocation. A comparison of both allocations reveals that the decentralized equilibrium is inefficient even if the HMP condition holds, because the planner lacks a tool with which to regulate the entry of buyers. Intuitively, in the decentralized economy households only evaluate if, given their utility of owning a home, it is worthwhile to enter the market. They do not, however, internalize their effect on other buyers’ search costs. By contrast, the planner internalizes the effect that an additional buyer has on other buyers’ costs.Footnote 3

We calibrate the model to the U.S. economy to assess how far the decentralized equilibrium is from the efficient allocation. Given that the housing market is inefficient, a natural follow up question is whether housing market policies can restore efficiency. This exercise gives us an alternative method to gauge the size of the externalities. We consider four housing policies: (i) taxes on new construction; (ii) taxes on profits from housing sales; (iii) transfer fees to the buyer; (iv) property taxes. We study these policies because they affect the entry decision of buyers and sellers and how the trade surplus is split. We find that the optimal vacancy rate and time-to-sell are about half their values in the decentralized economy, and the optimal number of vacancies about

![]() $80\%$

of its counterpart in the decentralized economy. By contrast, the optimal number of buyers and homeowners are both above the value in the decentralized economy. Intuitively, the planner finds it optimal to increase homeownership. However, she chooses not to achieve this through a faster matching rate for buyers because new home construction is costly. Instead, the planner decreases the number of available housing units for sale and raises the number of buyers. This ensures high homeownership rates while keeping houses for sale low. We then turn to whether policies can implement the planner’s allocation. Since the model features two externalities, two policy tools are required to restore efficiency. We show that a combination of taxes on profits from housing sales and a subsidy to housing construction can implement the constrained-efficient allocation. To provide an alternative measure of the size of the two externalities, we calculate the quantitative magnitude of the policies required to restore efficiency.

$80\%$

of its counterpart in the decentralized economy. By contrast, the optimal number of buyers and homeowners are both above the value in the decentralized economy. Intuitively, the planner finds it optimal to increase homeownership. However, she chooses not to achieve this through a faster matching rate for buyers because new home construction is costly. Instead, the planner decreases the number of available housing units for sale and raises the number of buyers. This ensures high homeownership rates while keeping houses for sale low. We then turn to whether policies can implement the planner’s allocation. Since the model features two externalities, two policy tools are required to restore efficiency. We show that a combination of taxes on profits from housing sales and a subsidy to housing construction can implement the constrained-efficient allocation. To provide an alternative measure of the size of the two externalities, we calculate the quantitative magnitude of the policies required to restore efficiency.

Related literature. Since the seminal work in Arnott (Reference Arnott1989) and Wheaton (Reference Wheaton1990), the literature has extensively used search and matching models à la Diamond-Mortensen-Pissarides to study the housing market. This large literature includes Albrecht et al. (Reference Albrecht, Anderson, Smith and Vroman2007), Anenberg (Reference Anenberg2016), Arefeva (Reference Arefeva2025), Arefeva et al. (Reference Arefeva, Guo, Han and Ortego-Marti2025), Burnside et al. (Reference Burnside, Eichenbaum and Rebelo2016), Diaz and Jerez (Reference Diaz and Jerez2013), Gabrovski et al. (Reference Gabrovski, Kumar and Ortego-Marti2024), Gabrovski and Ortego-Marti (Reference Gabrovski and Ortego-Marti2019, Reference Gabrovski and Ortego-Marti2021a, Reference Gabrovski and Ortego-Marti2025), Garriga and Hedlund (Reference Garriga and Hedlund2020), Genesove and Han (Reference Genesove and Han2012), Guren (Reference Guren2018); Guren and McQuade (Reference Guren and McQuade2020), Han et al. (Reference Han, Ngai and Sheedy2025), Head et al. (Reference Head, Lloyd-Ellis and Sun2014, Reference Head, Lloyd-Ellis and Sun2016), Hedlund (Reference Hedlund2016) Kotova and Zhang (Reference Kotova and Zhang2020), Krainer (Reference Krainer2001), Ngai and Tenreyro (Reference Ngai and Tenreyro2014), Ngai and Sheedy (Reference Ngai and Sheedy2020, Reference Ngai and Sheedy2024), Novy-Marx (Reference Novy-Marx2009), Piazzesi and Schneider (Reference Piazzesi and Schneider2009), Piazzesi et al. (Reference Piazzesi, Schneider and Stroebel2020), Smith (Reference Smith2020) and Smith et al. (Reference Smith, Xie and Fang2022). Han and Strange (Reference Han and Strange2015) provide an extensive review of this literature. Compared to these papers, we study efficiency in the housing market in a framework with search frictions and an endogenous entry of buyers and sellers mechanism that delivers the observed positive correlation between buyers and vacancies, i.e. an upward-sloping Beveridge Curve. In addition, we characterize the congestion and participation externalities in the housing market and quantify how far the observed equilibrium is from the optimal allocation.

To a lesser extent, our paper is also related to papers that study efficiency in labor markets with search frictions and compositional effects that arise from labor force participation (Albrecht et al. Reference Albrecht, Navarro and Vroman2010; Griffy and Masters, Reference Griffy and Masters2022; Julien and Mangin, Reference Julien and Mangin2017; Masters, Reference Masters2015). Although in search models with labor market participation the Beveridge Curve is downward-sloping and consistent with the labor market stylized facts, empirically the Beveridge Curve in the housing market is upward-sloping (Gabrovski and Ortego-Marti, Reference Gabrovski and Ortego-Marti2019, Reference Gabrovski and Ortego-Marti2024). Relative to the above papers in the labor literature, we study efficiency in a framework with a different entry mechanism that is consistent with an upward-sloping Beveridge Curve in the housing market.Footnote 4

2. The housing market with endogenous buyer entry

This section studies efficiency with an endogenous entry mechanism similar to Gabrovski and Ortego-Marti (Reference Gabrovski and Ortego-Marti2019) in which buyers’ search costs increase as more buyers enter the market. We begin with a description of the decentralized economy. The main ingredients of the model are: there are search and matching frictions, which capture that it takes time for buyers to find a house and for sellers to find a buyer for their listed property, there is free entry of both buyers and sellers, and prices are determined by bargaining.

Next, we derive the efficient allocation. The planner faces two externalities. First, search frictions give rise to the usual congestion and thick market externalities. When sellers list a house for sale, they do not internalize that by posting a house for sale they increase buyers’ chances of finding a home (thick market externality). At the same time, they also make it more difficult for other sellers to find a buyer (congestion externality). To simplify the exposition, we refer to both thick market and congestion externalities as congestion externalities. The second externality arises because buyers do not internalize that by entering the market they raise search costs for other buyers. We denote this externality a participation externality. As we show in this section, because of this additional externality, the HMP condition does not restore efficiency. Intuitively, the social planner needs an additional tool to first fix the entry of buyers to its efficient level.

2.1 Environment

Time is continuous. Agents are risk-neutral, infinitely lived and discount the future at a rate

![]() $r$

. There are three types of agents: households, developers and realtors. Households either own a home, search for a house (i.e. they are buyers), or choose not to participate in the market. Developers may enter the housing market and build a new home at a cost

$r$

. There are three types of agents: households, developers and realtors. Households either own a home, search for a house (i.e. they are buyers), or choose not to participate in the market. Developers may enter the housing market and build a new home at a cost

![]() $k$

if not enough existing houses are listed for sale by households through separations. Upon building a house, developers post a vacancy and search for buyers. Houses are identical, regardless of whether they are old or newly built. To capture depreciation in a tractable way, houses are destroyed at an exogenous rate

$k$

if not enough existing houses are listed for sale by households through separations. Upon building a house, developers post a vacancy and search for buyers. Houses are identical, regardless of whether they are old or newly built. To capture depreciation in a tractable way, houses are destroyed at an exogenous rate

![]() $\delta$

.

$\delta$

.

It takes time for buyers to find a house and for sellers to sell their home. We capture these search frictions in the housing market by assuming a matching function

![]() $M(b,v)$

, where

$M(b,v)$

, where

![]() $b$

is the measure of buyers and

$b$

is the measure of buyers and

![]() $v$

the measure of vacancies or houses for sale—we use both terms interchangeably. The matching function satisfies the usual properties: it is increasing in each of its terms, concave and displays constant returns to scale. Let

$v$

the measure of vacancies or houses for sale—we use both terms interchangeably. The matching function satisfies the usual properties: it is increasing in each of its terms, concave and displays constant returns to scale. Let

![]() $\theta \equiv b/v$

denote the housing market tightness. The matching function implies that buyers find homes at a rate

$\theta \equiv b/v$

denote the housing market tightness. The matching function implies that buyers find homes at a rate

![]() $m(\theta ) \equiv M(b,v)/b=M(1,\theta ^{-1})$

and that sellers find buyers at a rate

$m(\theta ) \equiv M(b,v)/b=M(1,\theta ^{-1})$

and that sellers find buyers at a rate

![]() $\theta m(\theta ) = M(b,v)/v=M(\theta ,1)$

. As market tightness increases, the home-finding rate for buyers

$\theta m(\theta ) = M(b,v)/v=M(\theta ,1)$

. As market tightness increases, the home-finding rate for buyers

![]() $m(\theta )$

decreases and the finding rate for sellers

$m(\theta )$

decreases and the finding rate for sellers

![]() $\theta m(\theta )$

increases. Intuitively, an increase in market tightness implies that vacancies are relatively more scarce, so it becomes harder for buyers to find a house, but easier for a seller to find a buyer. In addition to these flows, some homeowners become separated from their house at an exogenous rate

$\theta m(\theta )$

increases. Intuitively, an increase in market tightness implies that vacancies are relatively more scarce, so it becomes harder for buyers to find a house, but easier for a seller to find a buyer. In addition to these flows, some homeowners become separated from their house at an exogenous rate

![]() $s$

. This separation shock captures that the household may need to relocate because of their job, need to move to a different type of home or area, and so on. Once a separation shock occurs, households list their house for sale.

$s$

. This separation shock captures that the household may need to relocate because of their job, need to move to a different type of home or area, and so on. Once a separation shock occurs, households list their house for sale.

There is free entry of both buyers and sellers. Given free entry of buyers, households keep entering the market until the value of becoming a buyer equals zero, the value of their outside option.Footnote 5 Similarly, free entry of sellers implies that sellers enter the market until the value of a vacancy equals the construction cost

![]() $k$

, regardless of whether the house is newly built or existing (all houses are identical). As is common in markets with search frictions, there are rents from matching. We assume that prices are determined by Nash Bargaining (Nash and John, Reference Nash and John1950; Rubinstein, Reference Rubinstein1982), where

$k$

, regardless of whether the house is newly built or existing (all houses are identical). As is common in markets with search frictions, there are rents from matching. We assume that prices are determined by Nash Bargaining (Nash and John, Reference Nash and John1950; Rubinstein, Reference Rubinstein1982), where

![]() $\beta$

denotes the seller’s bargaining strength.Footnote 6 Once a buyer and a seller are matched, the buyer pays the price

$\beta$

denotes the seller’s bargaining strength.Footnote 6 Once a buyer and a seller are matched, the buyer pays the price

![]() $p$

to the seller and begins enjoying a utility flow

$p$

to the seller and begins enjoying a utility flow

![]() $\varepsilon$

from owning a house.

$\varepsilon$

from owning a house.

Households must secure the services of a realtor to start searching for a house. Searching for houses is costly for the realtor. Her cost of servicing

![]() $b$

buyers is given by

$b$

buyers is given by

![]() $\bar {c} b^{\gamma +1}/(\gamma +1)$

, which is consistent with many findings in the real estate literature (Sirmans and Turnbull, Reference Sirmans and Turnbull1997). In exchange for her services, the realtor charges a fee

$\bar {c} b^{\gamma +1}/(\gamma +1)$

, which is consistent with many findings in the real estate literature (Sirmans and Turnbull, Reference Sirmans and Turnbull1997). In exchange for her services, the realtor charges a fee

![]() $c^B$

, so her revenue is

$c^B$

, so her revenue is

![]() $b c^B$

. Assuming a competitive market, the realtor’s problem is to maximize her net present value of profits,

$b c^B$

. Assuming a competitive market, the realtor’s problem is to maximize her net present value of profits,

![]() $\int _t^{\infty }e^{-r(v-t)}[b(v) c^B(v) - \bar {c} b(v)^{\gamma +1}/(\gamma +1)]dv$

, with respect to

$\int _t^{\infty }e^{-r(v-t)}[b(v) c^B(v) - \bar {c} b(v)^{\gamma +1}/(\gamma +1)]dv$

, with respect to

![]() $b(v)$

, the measure of buyers she provides the service to. Absent shocks, the realtor’s problem of maximizing the net present value of all future profits reduces to a static problem of maximizing profits per unit of time. Thus, profit maximization implies that the fee is given by

$b(v)$

, the measure of buyers she provides the service to. Absent shocks, the realtor’s problem of maximizing the net present value of all future profits reduces to a static problem of maximizing profits per unit of time. Thus, profit maximization implies that the fee is given by

![]() $c^B(b)=\bar {c} b^{\gamma }$

, which is increasing in the number of buyers.Footnote 7 Intuitively,

$c^B(b)=\bar {c} b^{\gamma }$

, which is increasing in the number of buyers.Footnote 7 Intuitively,

![]() $c^B(b)$

captures search costs such as arranging and scheduling viewings, driving to view houses or locating properties that match buyers’ preferences. In reality, buyers incur some of these costs themselves, but to simplify the exposition we assume that the realtor bears all the costs and then charges a fee

$c^B(b)$

captures search costs such as arranging and scheduling viewings, driving to view houses or locating properties that match buyers’ preferences. In reality, buyers incur some of these costs themselves, but to simplify the exposition we assume that the realtor bears all the costs and then charges a fee

![]() $c^B(b)$

. Assuming instead that buyers incur all costs themselves, and that costs are increasing in the number of buyers due to congestion, gives the exact same results. This endogenous entry mechanism generates an upward-sloping Beveridge Curve, and accounts for the housing market stylized facts qualitatively and quantitatively (Gabrovski and Ortego-Marti, Reference Gabrovski and Ortego-Marti2019). Finally, sellers incur search flow cost

$c^B(b)$

. Assuming instead that buyers incur all costs themselves, and that costs are increasing in the number of buyers due to congestion, gives the exact same results. This endogenous entry mechanism generates an upward-sloping Beveridge Curve, and accounts for the housing market stylized facts qualitatively and quantitatively (Gabrovski and Ortego-Marti, Reference Gabrovski and Ortego-Marti2019). Finally, sellers incur search flow cost

![]() $c^S$

until they find a buyer.Footnote 8

$c^S$

until they find a buyer.Footnote 8

2.2 Decentralized equilibrium

Let

![]() $H$

,

$H$

,

![]() $B$

and

$B$

and

![]() $V$

denote the value functions of a homeowner, a buyer and a vacancy. They satisfy the Bellman equations

$V$

denote the value functions of a homeowner, a buyer and a vacancy. They satisfy the Bellman equations

Intuitively, buyers can choose whether to enter the housing market. When they search for a house, they incur flow costs

![]() $c^B(b)$

. At a rate

$c^B(b)$

. At a rate

![]() $m(\theta )$

, they find a house, pay the house price

$m(\theta )$

, they find a house, pay the house price

![]() $p$

and become a homeowner, which carries a net gain

$p$

and become a homeowner, which carries a net gain

![]() $H-B-p$

. A homeowner derives a utility

$H-B-p$

. A homeowner derives a utility

![]() $\varepsilon$

from owning a house. At a rate

$\varepsilon$

from owning a house. At a rate

![]() $s$

a separation shock occurs, and the household lists her house for sale, which has a value

$s$

a separation shock occurs, and the household lists her house for sale, which has a value

![]() $V$

, and decides whether to become a buyer. At a rate

$V$

, and decides whether to become a buyer. At a rate

![]() $\delta$

the house is destroyed, which implies a net loss of

$\delta$

the house is destroyed, which implies a net loss of

![]() $H-B$

. Similarly, the seller’s Bellman equation is given by

$H-B$

. Similarly, the seller’s Bellman equation is given by

Sellers incur flow costs

![]() $c^S$

while they search. At a rate

$c^S$

while they search. At a rate

![]() $\theta m(\theta )$

, they meet a buyer and enjoy net capital gains

$\theta m(\theta )$

, they meet a buyer and enjoy net capital gains

![]() $p-V$

. The vacancy is also subject to a destruction shock at a rate

$p-V$

. The vacancy is also subject to a destruction shock at a rate

![]() $\delta$

.

$\delta$

.

Because of the frictional nature of the housing market, a match between a buyer and seller generates a positive surplus. We assume that the two parties split this surplus according to Nash Bargaining. Let

![]() $S^B \equiv H-B-p$

and

$S^B \equiv H-B-p$

and

![]() $S^S \equiv p-V$

denote the surpluses of the buyer and seller, and let

$S^S \equiv p-V$

denote the surpluses of the buyer and seller, and let

![]() $S \equiv S^B+S^S$

denote the total surplus. Prices solve the following Nash Bargaining problem

$S \equiv S^B+S^S$

denote the total surplus. Prices solve the following Nash Bargaining problem

The first order condition to the above problem yields

![]() $(1-\beta ) S^S= \beta S^B$

. In particular, the above sharing rule implies that the buyer extracts a fraction

$(1-\beta ) S^S= \beta S^B$

. In particular, the above sharing rule implies that the buyer extracts a fraction

![]() $1-\beta$

of the surplus and the seller a fraction

$1-\beta$

of the surplus and the seller a fraction

![]() $\beta$

, i.e.

$\beta$

, i.e.

![]() $S^B = (1-\beta ) S$

and

$S^B = (1-\beta ) S$

and

![]() $S^S=\beta S$

. As a consequence both the buyer and seller agree on when the trade is beneficial, i.e.

$S^S=\beta S$

. As a consequence both the buyer and seller agree on when the trade is beneficial, i.e.

![]() $S^B \geq 0$

if and only if

$S^B \geq 0$

if and only if

![]() $S^S \geq 0$

, and if and only if

$S^S \geq 0$

, and if and only if

![]() $S\geq 0$

.

$S\geq 0$

.

Free entry implies that sellers enter the market until the value of a vacancy covers the construction costs

![]() $k$

, i.e.

$k$

, i.e.

![]() $V=k$

. On the buyer’s side, households participate in the market until the value of being a buyer

$V=k$

. On the buyer’s side, households participate in the market until the value of being a buyer

![]() $B$

equals the value of their outside option, which we normalize to 0, i.e.

$B$

equals the value of their outside option, which we normalize to 0, i.e.

![]() $B=0$

. Combining the Bellman equations for the buyer and seller (1) and (2) with the free entry condition for sellers implies

$B=0$

. Combining the Bellman equations for the buyer and seller (1) and (2) with the free entry condition for sellers implies

Combining the above surpluses with the Nash bargaining rule gives the equilibrium price (PP) condition

Intuitively, due to Nash Bargaining sellers are compensated for their outside option,

![]() $k$

, and receive a share

$k$

, and receive a share

![]() $\beta$

of the surplus.Footnote 9

$\beta$

of the surplus.Footnote 9

Free entry of sellers, together with the Bellman equation for a vacancy (3) gives the Housing Entry (HE) condition

The left hand-side of the above equation captures the seller’s expected cost from searching for a buyer: the search cost

![]() $c^S$

and the user cost

$c^S$

and the user cost

![]() $(r+\delta )k$

for the expected duration of the vacancy

$(r+\delta )k$

for the expected duration of the vacancy

![]() $1/(\theta m(\theta ))$

. The right-hand side corresponds to the seller’s surplus. The HE condition reflects that developers keep entering the market until the profits from selling the house are just enough to cover the expected cost of finding a buyer. Thus the (HE) condition governs entry of sellers in equilibrium.

$1/(\theta m(\theta ))$

. The right-hand side corresponds to the seller’s surplus. The HE condition reflects that developers keep entering the market until the profits from selling the house are just enough to cover the expected cost of finding a buyer. Thus the (HE) condition governs entry of sellers in equilibrium.

Free entry of buyers gives the Buyer’s Entry (BE) condition

Intuitively, buyers keep entering the market until the marginal buyer’s expected cost of finding a home equals the buyer’s surplus of being a homeowner, which equals the present discounted value of the return

![]() $\varepsilon$

net of the user cost

$\varepsilon$

net of the user cost

![]() $(r+\delta )k$

, using the effective discount

$(r+\delta )k$

, using the effective discount

![]() $r+s+\delta$

.

$r+s+\delta$

.

The PP and HE conditions determine the equilibrium market tightness

![]() $\theta$

. Given the equilibrium

$\theta$

. Given the equilibrium

![]() $\theta$

, the BE condition yields the equilibrium measure of buyers

$\theta$

, the BE condition yields the equilibrium measure of buyers

![]() $b$

. It is straightforward to verify that the equilibrium exists and is unique. This environment yields an upward-sloping Beveridge Curve, which corresponds to the BE curve. Intuitively, as more sellers enter the market, buyers find it more desirable to enter because they can find houses more quickly. Hence, buyers and vacancies are positively correlated and the BE curve is upward-sloping.

$b$

. It is straightforward to verify that the equilibrium exists and is unique. This environment yields an upward-sloping Beveridge Curve, which corresponds to the BE curve. Intuitively, as more sellers enter the market, buyers find it more desirable to enter because they can find houses more quickly. Hence, buyers and vacancies are positively correlated and the BE curve is upward-sloping.

The equilibrium is depicted graphically in figures 1a, b. Figure 1a depicts the HE condition and the price relationship PP given by (7) and (8). The HE condition captures that as house prices increase it becomes more profitable to post a vacancy. This leads to more entry of sellers and a lower market tightness. The PP condition comes from Nash Bargaining between buyers and sellers. The equilibrium price

![]() $p^{\ast }$

and market tightness

$p^{\ast }$

and market tightness

![]() $\theta ^{\ast }$

are given by the intersection of both curves. The equilibrium market tightness

$\theta ^{\ast }$

are given by the intersection of both curves. The equilibrium market tightness

![]() $\theta ^{\ast }$

in figure 1a describes a straight line in the vacancies-buyers space in figure 1b, which we denote as the HE condition. The BE curve in figure 1b corresponds to the BE condition (9). The BE curve captures that as the ratio of vacancies to buyers increases buyers find houses faster, which leads to an increase in the entry of buyers.

$\theta ^{\ast }$

in figure 1a describes a straight line in the vacancies-buyers space in figure 1b, which we denote as the HE condition. The BE curve in figure 1b corresponds to the BE condition (9). The BE curve captures that as the ratio of vacancies to buyers increases buyers find houses faster, which leads to an increase in the entry of buyers.

Figure 1. Equilibrium in the housing market.

2.3 The social planner’s allocation

The social planner faces two externalities. In addition to the usual congestion externality in markets with search frictions, the decentralized equilibrium is inefficient because buyers do not internalize the effect their entry has on other buyers’ search costs. We refer to this additional externality as the participation externality. Let

![]() $\tilde {h}$

and

$\tilde {h}$

and

![]() $c$

denote the number of homeowners and construction (the number of newly built houses). The planner’s problem is given by

$c$

denote the number of homeowners and construction (the number of newly built houses). The planner’s problem is given by

subject to

Setting up the Hamiltonian and using the first order conditions gives the following solution for the planner’ allocation at steady state

where

![]() $\alpha \equiv - m'(\theta )\theta /m(\theta )$

denotes the elasticity of the matching rate. The appendix provides the derivations and shows that the above conditions are necessary and sufficient. Equations (13) and (14) are the counterpart of the equilibrium conditions (8) and (9) in the decentralized economy. Comparing the decentralized allocation with the optimal one shows that the HMP condition does not restore efficiency. More specifically, restoring efficiency in the decentralized equilibrium requires

$\alpha \equiv - m'(\theta )\theta /m(\theta )$

denotes the elasticity of the matching rate. The appendix provides the derivations and shows that the above conditions are necessary and sufficient. Equations (13) and (14) are the counterpart of the equilibrium conditions (8) and (9) in the decentralized economy. Comparing the decentralized allocation with the optimal one shows that the HMP condition does not restore efficiency. More specifically, restoring efficiency in the decentralized equilibrium requires

The first condition

![]() $\beta =\alpha$

corresponds to the standard HMP condition. If HMP holds, the decentralized equilibrium is efficient if and only if

$\beta =\alpha$

corresponds to the standard HMP condition. If HMP holds, the decentralized equilibrium is efficient if and only if

![]() $\gamma =0$

, i.e. there is no entry of buyers. As soon as there is free entry of buyers, the equilibrium is inefficient because the endogenous entry of buyers generates a participation externality.Footnote 10 Intuitively, when there is no buyer entry the only externality is the congestion externality, which can be internalized if the two parties share the surplus in the appropriate fractions, i.e. the seller receives a share

$\gamma =0$

, i.e. there is no entry of buyers. As soon as there is free entry of buyers, the equilibrium is inefficient because the endogenous entry of buyers generates a participation externality.Footnote 10 Intuitively, when there is no buyer entry the only externality is the congestion externality, which can be internalized if the two parties share the surplus in the appropriate fractions, i.e. the seller receives a share

![]() $\alpha$

and the buyer receives the rest. With endogenous entry of buyers, however, the participation externality manifests itself through increased search costs for buyers. As a result, the planner finds it optimal to disincentivize entry by giving buyers only a share

$\alpha$

and the buyer receives the rest. With endogenous entry of buyers, however, the participation externality manifests itself through increased search costs for buyers. As a result, the planner finds it optimal to disincentivize entry by giving buyers only a share

![]() $(1-\alpha )/(1+\gamma )$

of the surplus and leaving the remaining

$(1-\alpha )/(1+\gamma )$

of the surplus and leaving the remaining

![]() $\gamma (1-\alpha )/(1+\gamma )$

fraction of the surplus “on the table.” Thus, at least two housing market policies are required to eliminate the two externalities and restore efficiency: one policy to set the fraction of surplus that is left “on the table” (i.e. eliminate the participation externality), and one to set the sharing rule for the remainder of the surplus (i.e. eliminate the congestion externality).Footnote 11

$\gamma (1-\alpha )/(1+\gamma )$

fraction of the surplus “on the table.” Thus, at least two housing market policies are required to eliminate the two externalities and restore efficiency: one policy to set the fraction of surplus that is left “on the table” (i.e. eliminate the participation externality), and one to set the sharing rule for the remainder of the surplus (i.e. eliminate the congestion externality).Footnote 11

3. Quantifying inefficiency in the housing market

In this section we quantify the inefficiency in the housing market implied by the congestion and participation externalities. In other words, we ask: how far is the decentralized equilibrium from the efficient allocation? To this end, we calibrate a version of our model which includes housing market policies. Consequently, we can study what policies implement the socially efficient allocation in the decentralized economy. Upon calibrating the model to the U.S. housing market, we measure the distance between the decentralized equilibrium allocation and the planner’s efficient allocation in terms of liquidity, for which we use three measures: time-to-sell, the vacancy rate, and the listing rate. In a second exercise, we examine the housing policies required to restore efficiency.

3.1 The model with housing policies

We consider four policies. First, homeowners pay property taxes

![]() $\tau _p$

on their home. Second, buyers pay taxes

$\tau _p$

on their home. Second, buyers pay taxes

![]() $\tau _b$

when they purchase a house. Third, sellers pay a tax

$\tau _b$

when they purchase a house. Third, sellers pay a tax

![]() $\tau _s$

upon selling the house, which we assume applies to the capital gains

$\tau _s$

upon selling the house, which we assume applies to the capital gains

![]() $p-V$

. Finally, construction may be taxed or subsidized at a rate

$p-V$

. Finally, construction may be taxed or subsidized at a rate

![]() $\tau _k$

, where

$\tau _k$

, where

![]() $\tau _k \gt 0$

corresponds to a tax on construction and

$\tau _k \gt 0$

corresponds to a tax on construction and

![]() $\tau _k \lt 0$

to a subsidy. The Bellman equations are given by

$\tau _k \lt 0$

to a subsidy. The Bellman equations are given by

The intuition for the above Bellman equations is similar to the intuition for (1)–(3). House prices are determined in a similar way by Nash Bargaining, except that the surplus

![]() $S$

is now given by

$S$

is now given by

![]() $S=H-B-(1+\tau _b)p + (1-\tau _s)\left (p-V\right )$

, where

$S=H-B-(1+\tau _b)p + (1-\tau _s)\left (p-V\right )$

, where

![]() $S^B=H-B-(1+\tau _b)p$

is the buyer surplus and

$S^B=H-B-(1+\tau _b)p$

is the buyer surplus and

![]() $S^S=(1-\tau _s)\left (p-V\right )$

is the seller’s surplus. Nash Bargaining implies the following first order conditions:

$S^S=(1-\tau _s)\left (p-V\right )$

is the seller’s surplus. Nash Bargaining implies the following first order conditions:

![]() $S^S= \tilde {\beta }S$

and

$S^S= \tilde {\beta }S$

and

![]() $S^B= (1-\tilde {\beta })S$

, where

$S^B= (1-\tilde {\beta })S$

, where

![]() $\tilde {\beta }\equiv \beta (1-\tau _s)/[\beta (1-\tau _s) +(1-\beta )(1+\tilde {\tau }_b)]$

and

$\tilde {\beta }\equiv \beta (1-\tau _s)/[\beta (1-\tau _s) +(1-\beta )(1+\tilde {\tau }_b)]$

and

![]() $\tilde {\tau }_b\equiv \tau _b + \tau _p/(r+s+\delta )$

.Footnote 12

$\tilde {\tau }_b\equiv \tau _b + \tau _p/(r+s+\delta )$

.Footnote 12

Following the same steps as in section 2.2, we find the following equilibrium conditions

which correspond to the PP, HE and BE conditions without policies (7), (8) and (9). We use these conditions to calibrate the model and derive the optimal policies in our numerical exercise below.Footnote 13

3.2 Calibration

Following Gabrovski and Ortego-Marti (Reference Gabrovski and Ortego-Marti2021a), let

![]() $r=0.012$

to match an annual discount factor of

$r=0.012$

to match an annual discount factor of

![]() $0.953$

. We set

$0.953$

. We set

![]() $\delta =0.004$

to match an annual housing depreciation rate of

$\delta =0.004$

to match an annual housing depreciation rate of

![]() $1.6\%$

(Van Nieuwerburgh and Weill, Reference Van Nieuwerburgh and Weill2010). The matching function is assumed to be Cobb-Douglas with

$1.6\%$

(Van Nieuwerburgh and Weill, Reference Van Nieuwerburgh and Weill2010). The matching function is assumed to be Cobb-Douglas with

![]() $m(\theta ) = \mu \theta ^{-\alpha }$

. The elasticity of the matching function

$m(\theta ) = \mu \theta ^{-\alpha }$

. The elasticity of the matching function

![]() $\alpha$

is equal to

$\alpha$

is equal to

![]() $0.16$

, following the empirical evidence in Genesove and Han (Reference Genesove and Han2012). The flow utility of owning a house

$0.16$

, following the empirical evidence in Genesove and Han (Reference Genesove and Han2012). The flow utility of owning a house

![]() $\varepsilon$

is normalized to

$\varepsilon$

is normalized to

![]() $10.883$

. This implies a steady state price of

$10.883$

. This implies a steady state price of

![]() $491.2$

, which is the average empirically observed price (in thousands of dollars) in Kotova and Zhang (Reference Kotova and Zhang2020). We set a profit tax rate for sellers of

$491.2$

, which is the average empirically observed price (in thousands of dollars) in Kotova and Zhang (Reference Kotova and Zhang2020). We set a profit tax rate for sellers of

![]() $3.65\%$

, which corresponds to the average effective tax rate for the Real Estate Developer firms for the years 2014-2019 as reported by Aswath Damodaran.Footnote 14 The Tax Foundation in its “Facts and Figures 2018” reports an effective annual property tax rate for the United States of

$3.65\%$

, which corresponds to the average effective tax rate for the Real Estate Developer firms for the years 2014-2019 as reported by Aswath Damodaran.Footnote 14 The Tax Foundation in its “Facts and Figures 2018” reports an effective annual property tax rate for the United States of

![]() $1.13\%$

. The median real estate transfer tax rate reported by the National Association of Realtors is

$1.13\%$

. The median real estate transfer tax rate reported by the National Association of Realtors is

![]() $0.16\%$

. Following Gabrovski and Ortego-Marti (Reference Gabrovski and Ortego-Marti2019), we assume that

$0.16\%$

. Following Gabrovski and Ortego-Marti (Reference Gabrovski and Ortego-Marti2019), we assume that

![]() $c^B(b) = \bar {c}b^\gamma$

. We normalize

$c^B(b) = \bar {c}b^\gamma$

. We normalize

![]() $\bar {c}=1$

, which yields

$\bar {c}=1$

, which yields

![]() $b = 96.29$

.

$b = 96.29$

.

To obtain the rest of the model parameters we target six moments from the data. The time-to-sell is set to

![]() $1.76$

quarters which is the average of the Median Number of Months on Sales Market reported by the U.S. Bureau of Census for the period of 1987:1–2017:4. We also set the time-to-buy to be equal to the time to sell following Gabrovski and Ortego-Marti (Reference Gabrovski and Ortego-Marti2019, Reference Gabrovski and Ortego-Marti2021a) based on the evidence in Genesove and Han (Reference Genesove and Han2012). These two targets yield

$1.76$

quarters which is the average of the Median Number of Months on Sales Market reported by the U.S. Bureau of Census for the period of 1987:1–2017:4. We also set the time-to-buy to be equal to the time to sell following Gabrovski and Ortego-Marti (Reference Gabrovski and Ortego-Marti2019, Reference Gabrovski and Ortego-Marti2021a) based on the evidence in Genesove and Han (Reference Genesove and Han2012). These two targets yield

![]() $\mu =0.5682$

,

$\mu =0.5682$

,

![]() $k=451.98$

. Ngai and Sheedy (Reference Ngai and Sheedy2020) calculate a listing rate, given by the number of new listings on the market divided by the stock of owner-occupied houses not already for sale, equal to

$k=451.98$

. Ngai and Sheedy (Reference Ngai and Sheedy2020) calculate a listing rate, given by the number of new listings on the market divided by the stock of owner-occupied houses not already for sale, equal to

![]() $1.667\%$

. This target implies a separation rate

$1.667\%$

. This target implies a separation rate

![]() $s=0.0126$

. To calibrate

$s=0.0126$

. To calibrate

![]() $c^S$

, we target expected costs for the seller equal to

$c^S$

, we target expected costs for the seller equal to

![]() $5.1\%$

of the average house price, following Ghent (Reference Ghent2012). Following the same reference we also target an average cost for the buyer of

$5.1\%$

of the average house price, following Ghent (Reference Ghent2012). Following the same reference we also target an average cost for the buyer of

![]() $8\%$

. These two moments yield

$8\%$

. These two moments yield

![]() $c^S = 14.233$

and

$c^S = 14.233$

and

![]() $\beta = 0.5234$

. Lastly, to calibrate

$\beta = 0.5234$

. Lastly, to calibrate

![]() $\gamma$

we use monthly data on vacancies and sales from the New Residential Sales Release reported by the U.S. Bureau of Census for the period January 1963–December 2019.Footnote 15 Given that in our model sales

$\gamma$

we use monthly data on vacancies and sales from the New Residential Sales Release reported by the U.S. Bureau of Census for the period January 1963–December 2019.Footnote 15 Given that in our model sales

![]() $=b m(\theta )$

, the information on sales and vacancies allows us to back out a series for the number of buyers using

$=b m(\theta )$

, the information on sales and vacancies allows us to back out a series for the number of buyers using

![]() $b = v [\text{sales}/(\mu v)]^{1/(1-\alpha )}$

. Next, we regress the cyclical component of the series for buyers on the cyclical component of the series for vacancies and a constant to arrive at an elasticity of

$b = v [\text{sales}/(\mu v)]^{1/(1-\alpha )}$

. Next, we regress the cyclical component of the series for buyers on the cyclical component of the series for vacancies and a constant to arrive at an elasticity of

![]() $0.19$

.Footnote 16 Plugging this estimate into equation (14) in Gabrovski and Ortego-Marti (Reference Gabrovski and Ortego-Marti2019) results in

$0.19$

.Footnote 16 Plugging this estimate into equation (14) in Gabrovski and Ortego-Marti (Reference Gabrovski and Ortego-Marti2019) results in

![]() $\gamma =0.68$

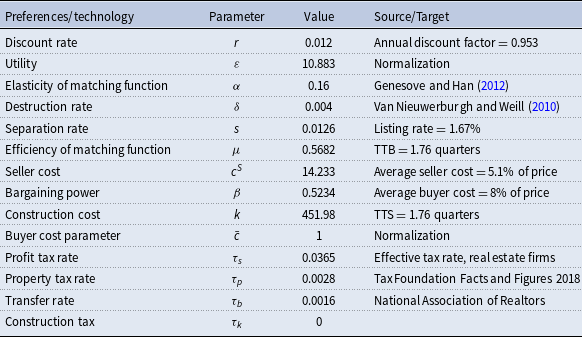

. Table 1 summarizes the calibration.

$\gamma =0.68$

. Table 1 summarizes the calibration.

Table 1. Baseline model: calibration

3.3 Results

Our calibrated model matches the housing market data well. In particular, vacancy and construction rates, which are not targeted in the calibration, are close to their empirical counterparts. These moments are of particular relevance in our context: the vacancy rate captures liquidity in the housing market, whereas the construction rate captures the importance of the entry channel, which is at the core of our paper. In the model, the vacancy rate is measured as the ratio of vacancies to the total stock of homes and equals

![]() $2.83\%$

in the steady state. In the data, the vacancy rate is

$2.83\%$

in the steady state. In the data, the vacancy rate is

![]() $1.9\%$

and is measured as the average of the Homeowner Vacancy Rate reported by the United States Census Bureau for the period 1987:1–2017:4. The model also does a relatively good job at matching the construction rate. In the model, this construction rate is measured by the number of homes built divided by the total housing stock, and is equal to

$1.9\%$

and is measured as the average of the Homeowner Vacancy Rate reported by the United States Census Bureau for the period 1987:1–2017:4. The model also does a relatively good job at matching the construction rate. In the model, this construction rate is measured by the number of homes built divided by the total housing stock, and is equal to

![]() $0.4\%$

. In the data, the average of this ratio for the period 1987:1–2017:4 is

$0.4\%$

. In the data, the average of this ratio for the period 1987:1–2017:4 is

![]() $0.27\%$

.Footnote 17

$0.27\%$

.Footnote 17

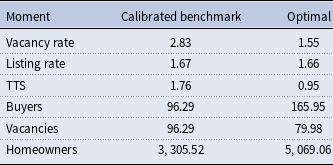

We gauge the distance of the decentralized equilibrium to the planner’s social optimum by focusing on three important measures of liquidity in the housing market: the vacancy rate, the listing rate, and the time-to-sell. The values of these liquidity measures at the steady state equilibrium and at the planner’s optimum are summarized in Table 2. In general, the planner finds it optimal to reduce the relative amount of vacancies in the market and to have houses match with buyers faster. Intuitively, this is due to the congestion externality. In equilibrium sellers extract too much of the surplus which induces an inefficient over-entry into the market. This leads to higher than optimal expected search and construction costs for sellers.

Table 2. Baseline model: moments

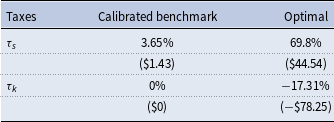

Finally, we quantify the size of the housing policies required to restore efficiency. Table 3 reports the optimal tax rates implied by the model and the dollar amount of these policies, in thousands of dollars. The efficient allocation requires fewer houses for sale and more buyers than the decentralized equilibrium. This can be achieved through a combination of taxes on sellers and a subsidy to housing construction.Footnote 18 From the HE condition (20), a lower

![]() $\tau _k$

and a higher

$\tau _k$

and a higher

![]() $\tau _s$

both raise the market tightness, which lowers time-to-sell. From the BE condition, the combination of a lower market tightness, a lower

$\tau _s$

both raise the market tightness, which lowers time-to-sell. From the BE condition, the combination of a lower market tightness, a lower

![]() $\tau _k$

and a higher

$\tau _k$

and a higher

![]() $\tau _s$

raises the measure of buyers. Quantitatively, raising the profit tax from

$\tau _s$

raises the measure of buyers. Quantitatively, raising the profit tax from

![]() $3.65$

to

$3.65$

to

![]() $69.8\%$

and subsidizing construction at a rate

$69.8\%$

and subsidizing construction at a rate

![]() $17.31\%$

brings the housing market to its efficient level. In dollar amounts, these policies correspond to $44,540 and $78,250 respectively. To put the dollar amount in perspective, our calibration is such that house prices are

$17.31\%$

brings the housing market to its efficient level. In dollar amounts, these policies correspond to $44,540 and $78,250 respectively. To put the dollar amount in perspective, our calibration is such that house prices are

![]() $\$491,000$

on average, as in the data.

$\$491,000$

on average, as in the data.

Table 3. Baseline model: optimal policies

4. Conclusion

This paper studies efficiency in the housing market with search frictions and endogenous entry of both buyers and sellers. These two features are fundamental to account for the stylized facts of the housing market, in particular to generate a positive correlation between buyers and vacancies, i.e. an upward sloping Beveridge Curve. We show that in this environment two externalities arise: congestion and participation externalities. We characterize the efficient allocation and show that the decentralized equilibrium is inefficient even when the HMP condition holds. In particular, the decentralized economy features inefficiently low levels of homeownership and inefficiently high vacancy rate and time-to-sell. Finally, this paper studies housing market policies and how they can restore efficiency in the housing market.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Editor William Barnett, an anonymous Associate Editor, two anonymous referees, Elliot Anenberg, Richard Arnott, Jan Brueckner, Ed Coulson, Michael Devereux, Gilles Duranton, Jang-Ting Guo, Lu Han, Aaron Hedlund, Nir Jaimovich, Ioannis Kospentaris, Pablo Kurlat, Romain Rancière, Guillaume Rocheteau, Stephen Ross, Isaac Sorkin, Carl Walsh, Liang Wang, Pierre-Olivier Weill and seminar participants at the 15th North-American Meeting of the Urban Economics Association (World Bank, DC), the Midwest Macroeconomics Conference Spring 2022, the University of Hawaii Manoa, the University of California Irvine, the University of California Santa Cruz and Virginia Commonwealth University for their helpful comments and suggestions. This paper was previously circulated under the title “Efficiency in the Housing Market with Search Frictions”.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S1365100525100692.