Introduction

The onset of the Covid‐19 pandemic and the ensuing race for vaccines has highlighted an important collective action problem. While multilateral cooperation in vaccine distribution is the most promising strategy to end the pandemic globally,Footnote 1 wealthy nations also face powerful (short‐term) incentives to act unilaterally instead. ‘Vaccine nationalism’ – an approach that relies on direct advance contracts with vaccine manufacturers and prioritizes vaccinating the national population over a global vaccine rollout – may provide governments in high‐income countries (HICs) with electoral benefits if it minimizes domestic deaths and enables a faster relaxation of unpopular Covid‐19 restrictions. Faced with these competing incentives, HICs have generally valued the gains from unilateralism more than the (long‐term) benefits of multilateralism and prioritized the full protection of the national community over international solidarity. Although most HICs expressed their support for COVAX, the main multilateral institution for global vaccination cooperation during Covid‐19Footnote 2 and pledged financial contributions as well as donations of vaccines, they have pursued largely a unilateral strategy and tried to secure early supplies of the most promising vaccines for their own population. As a result, by late October 2021, HICs had received over 16 times more Covid‐19 vaccines per person than low‐income countries (LICs). In LICs, less than 3 per cent of the population had received at least one dose, compared with three quarters in HICs (Mancini et al., Reference Mancini, Bruce‐Lockhart and Schipani2021; see also Mathieu et al., Reference Mathieu, Ritchie, Ortiz‐Ospina, Roser, Hasell, Appel, Giattino and Rodés‐Guirao2021). The United Kingdom in particular has been lagging behind other G7 countries (except for Japan) in its commitment to share surplus vaccines with LICs. Moreover, by late October 2021, it had only distributed a third of these modest pledges for the year (Wintour, Reference Wintour2021).

While there has been much attention to, and criticism of, the general preference for unilateralism among the governments of HICs, there is a gap in the literature about the preferences of the public. We know very little about public attitudes towards multilateral vaccine cooperation. Yet, research has long demonstrated that public opinion can affect (foreign) policy more broadly (see, e.g., Page & Shapiro, Reference Page and Shapiro1983; Pevehouse, Reference Pevehouse2020, pp. 195–197; Risse‐Kappen, Reference Risse‐Kappen1991) and more recent scholarship has emphasized the crucial role of public opinion and domestic politicization in contemporary challenges to multilateral cooperation (Bearce & Jolliff Scott, Reference Bearce and Jolliff Scott2019; Copelovitch & Pevehouse, Reference Copelovitch and Pevehouse2019; Copelovitch et al., Reference Copelovitch, Hobolt and Walter2020; De Vries et al., Reference De Vries, Hobolt and Walter2021; Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Lenz and Marks2019; Pevehouse, Reference Pevehouse2020; Zürn, Reference Zürn2004, Reference Zürn2014).Footnote 3 Public opinion matters because governments anticipate which policies would be acceptable to the public (Baum & Potter, Reference Baum and Potter2008; Pevehouse, Reference Pevehouse2020, p. 197).Footnote 4 It is, therefore, important to ascertain whether public opinion in HICs is an obstacle to more far‐reaching multilateral cooperation on vaccination, or whether it is in fact more supportive than current government policies and conducive to achieving greater cooperation. Even more important from a policy perspective is the question of whether public support can be swayed by cues from political entrepreneurs. Can an information campaign increase public support for a multilateral approach, and, conversely, do appeals to vaccine nationalism decrease it? Research shows that information cues influence public opinion on international cooperation, yet it is unclear whether all cues are equally effective in a crisis situation, such as a global pandemic. There are good reasons to believe that how the public reacts to cues during a crisis is different from normal times, but the framing literature has not explored this question sufficiently. Our paper fills this gap by offering a theoretical framework that shows how framing works in times of crisis, and in doing so, sheds light on the prospects of public support for multilateralism in a global health crisis.

Drawing on the broader framing literature and insights from social psychology on in‐group/out‐group dynamics and decision‐making in crisis situations, we hypothesize that frames in public discourse that emphasize the gains from vaccine nationalism have a stronger effect than those that emphasize the benefits of international cooperation. The tendency to prioritize their own group, combined with crisis‐induced short‐termism, makes individuals more susceptible to the vaccine nationalism frame. While this effect should be evident across the board, there are good reasons to believe that it can be further amplified for certain groups. Building on research on public opinion towards international institutions and on motivated reasoning, we argue that individuals with a nationalist identity should be more susceptible to the vaccine nationalism frame than those with a cosmopolitan identity.

To test this framework, we conducted a survey experiment on a representative sample of 4,144 respondents in the United Kingdom in late September 2020. Our data suggest that public support for multilateral cooperation through COVAX is high but vulnerable. In line with our hypotheses, a frame that emphasizes vaccine nationalism reduces support for multilateral cooperation. Simultaneously, an international cooperation frame has no effect. The stronger effect of the vaccine nationalism frame is further demonstrated by the decrease in support for COVAX when respondents are provided with both frames concurrently. We also find that the negative effect of the vaccine nationalism frame on support for COVAX is amplified by respondents’ ‘Brexit identities’, which tap into broader worldviews, similar to a divide between nationalism and cosmopolitanism. ‘Leavers’ are significantly more susceptible to the vaccine nationalism frame than ‘Remainers’, and this division is a more important moderator of the frames than standard variables, such as political party preferences, placement on the Left–Right scale, age and education.

How framing works in crisis situations: Theory and hypotheses

Our theoretical framework consists of two parts. The first part considers the effect of frames in the public discourse on public opinion. We argue that frames matter, but that in crisis situations a certain type of frame matters more than others: a vaccine nationalism frame has a greater effect than a frame advocating international cooperation because short‐term thinking and in‐group allegiance trump long‐term considerations and out‐group solidarity. The second part of the framework considers how political identities moderate the effect of frames. We argue that motivated reasoning leads individuals with a nationalist identity to be particularly receptive to the effects of a vaccine nationalism frame.

Framing effects

Research has shown that citizens’ attitudes on a range of issues or policies are affected by the way in which the media or political actors frame their communication on those issues (Chong & Druckman, Reference Chong and Druckman2007; Gross, Reference Gross2008). Different mechanisms have been proposed as an explanation of this effect. Information in a frame may stimulate learning and consequently change an individual's opinion or, alternatively, a frame may increase the weight of specific considerations, making them more consequential (Haynes et al., Reference Haynes, Merolla and Ramakrishnan2016).

There are good reasons to believe that the effects of framing are likely to be particularly pronounced in situations where people are experiencing a novel threat, such as a pandemic. Levels of anxiety and distress tend to increase in those situations, and research has shown that ‘anxious individuals seek out more information, process this information more carefully, and rely less on heuristics’ (Wagner & Morisi, Reference Wagner and Morisi2019, p. 10). As such, they are more open to persuasion (Marcus et al., Reference Marcus, Sullivan, Theiss‐Morse and Stevens2005; Valentino et al., Reference Valentino, Hutchings, Banks and Davis2008).Footnote 5 Moreover, framing effects should be especially evident with respect to issues where public opinion tends to be ambivalent, rather than clearly either hostile or supportive. Such ambivalence prevails precisely in the case of attitudes towards international cooperation. Research shows that although the public has become less supportive of international institutions in recent decades (Bearce & Jollif Scott, Reference Bearce and Jolliff Scott2019; De Vries et al., Reference De Vries, Hobolt and Walter2021), public opinion is not generally hostile to international cooperation but ambivalent. This ambivalence means that there is an ‘increased openness of citizens to taking cues from political elites (or mass media) for forming opinions about international cooperation, and the actions of political entrepreneurs and the media play an important role in how the public thinks about the trade‐offs related to international cooperation’ (De Vries et al., Reference De Vries, Hobolt and Walter2021, p. 313; see also Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2009, p. 13).

The general framing literature would lead us to expect that cues in public discourse emphasizing the benefits of international vaccine cooperation increase support for COVAX, while a ‘vaccine nationalism’ frame decreases it. However, it is the effect of the latter frame that is particularly relevant for our theory, since we do not expect that all frames are equally effective in a crisis situation. Frames that are compatible with the well‐established regularities in human behaviour are likely to be more effective. Two strands of literature in social psychology offer insights into the likely effectiveness of different types of frames.

The first is the literature on in‐group/out‐group dynamics. In‐group bias – a tendency to favour the in‐group over the out‐group in terms of the allocation of resources or rewards – has been demonstrated in empirical research covering a range of different issues. This characteristic of human behaviour persists even in situations that involve others’ suffering. While humans are generally motivated to help each other and alleviate others’ suffering, when the target is an out‐group member, emphatic responses are not as frequent and tend to be more fragile (Cikara et al., Reference Cikara, Bruneau and Saxe2011). People tend to be less likely to help those in need when the victim is distant in space or belongs to a different racial, social or political group (Batson & Ahmad, Reference Batson and Ahmad2009). In‐group bias is expected to be reinforced by crisis situations (Wamsler et al., Reference Wamsler, Freitag, Erhardt and Filsinger2023). Following this reasoning, one should expect that more influential or effective frames are those that emphasize a response to a pandemic whereby alleviation of potential suffering for citizens is prioritized over international cooperation and transnational solidarity.

The second strand of literature that sheds further light on the issue of the effectiveness of frames is focused on decision‐making in crisis situations. Although humans are capable of planning ahead, we tend to favour short‐term payoffs over long‐term awards. Research using functional magnetic resonance imaging on subjects who were asked to consider delayed reward problems indicates that the possibility of immediate reward activates parts of the brain that are influenced by neural systems associated with emotion. Preferences for short‐term rewards thus reflect situations in which the emotion‐related parts of the brain win out over the calculating or abstract‐reasoning parts (McClure et al., Reference McClure, Laibson, Lowenstein and Cohen2004). What is the relevance of this for understanding behaviour and policy preferences during a pandemic? There are good reasons to believe that logical reasoning may not be a strong enough motivator for behaviour and decision‐making during a pandemic. Anxiety and fear tend to be the most prominent emotions, and these emotions shape risk perceptions sometimes more than factual information (Van Bavel et al., Reference Van Bavel, Baicker and Willer2020). Under such conditions, many individuals tend to make pessimistic judgements about the future, which strengthens preferences for risk‐averse choices (Lerner & Keltner, Reference Lerner and Keltner2001) that tend to be associated with short‐term policy solutions. When applied to our case, this literature would suggest that frames which emphasize vaccine nationalism (as a quicker solution to the direct threat to a person's life) would likely have stronger effects than frames that underline the benefits of international cooperation in vaccine distribution, which arise primarily in the long term.

This differential effect of the frames should not only matter for individual frames in isolation but also when they directly compete with each other. Since individuals in real‐life situations may encounter both arguments, we also analyse the effect of exposure to both frames concurrently. While this is in line with the recommendations in the framing literature (Chong & Druckman, Reference Chong and Druckman2007), there is no consensus about the effect of such competing frames (see also Zvobgo, Reference Zvobgo2019, p. 1069). Sniderman and Thériault (Reference Sniderman, Thériault, Sniderman and Saris2004) suggest that exposure to competing frames neutralizes any framing effects. By contrast, Chong and Druckman (Reference Chong and Druckman2007) suggest that exposure to competing frames has an attenuating effect: respondents’ attitudes differ from those in the control group and they take an intermediate position between the positions taken by respondents exposed to either of the two frames in isolation. Since we expect the vaccine nationalism frame to have a stronger effect than the international cooperation frame, we can formulate specific expectations about the effects of competing frames. Concurrent frames should not cancel each other out. Instead, their combined effect should be to reduce support for multilateralism. We therefore formulate the following hypotheses about the effects of frames:

Hypothesis 1a: The vaccine nationalism frame has a negative effect on support for COVAX.

Hypothesis 1b: The international cooperation frame has a positive effect on support for COVAX.

Hypothesis 1c: The effect of the vaccine nationalism frame is stronger than the effect of the international cooperation frame. By extension, concurrent exposure to both frames has a negative effect on support for COVAX.

Moderating effects

While the first part of our theoretical framework concerns how different frames affect support for COVAX, the second part of our framework suggests that this effect may be modified by respondents’ political identity. In other words, political identity may not only be a predictor of attitudes towards multilateral cooperation, but framing effects may be stronger or weaker, depending on differences in identity. This is so because individuals typically engage in motivated reasoning, which means that they are more likely to accept information that is consistent with their prior views (Kunda, Reference Kunda1990).

Research suggests that political identity shapes public opinion towards international institutions. Individuals who have an exclusive conception of national identity are less supportive of international cooperation (Bayram, Reference Bayram2017; Ghassim et al., Reference Ghassim, Koenig‐Archibugi and Cabrera2022; Hobolt et al., Reference Hobolt, Van der Brug, De Vreese, Boomgaarden and Hinrichsen2011; Hobolt & de Vries, Reference Hobolt and de Vries2016; Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2005; Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Lenz and Marks2019; McLaren, Reference McLaren2006; van der Brug et al., Reference van der Brug, Popa, Hobolt and Schmitt2021; Zvobgo, Reference Zvobgo2019). Studies of foreign aid, an area of international cooperation that shares some characteristics with the issue of a global vaccine rollout, also suggest that identity plays a role in donor publics' preferences (Bayram & Holmes, Reference Bayram and Holmes2020, p. 827, 839; Paxton & Knack, Reference Paxton and Knack2012, p. 182).

To examine the moderating effect of political identities on frames empirically, we focus on ‘Brexit identities’ as the most salient political identity in the United Kingdom. Research suggests that Brexit identities have become more prevalent than partisan identities in British politics (Curtice, Reference Curtice2018; Hobolt et al., Reference Hobolt, Leeper and Tilley2021; Sobolewska & Ford, Reference Sobolewska and Ford2020). Brexit identities reflect whether individuals think of themselves as a ‘Leaver’ or ‘Remainer’ regarding the United Kingdom's membership in the European Union (EU). Identification as a Leaver or Remainer goes much deeper than an individual's voting preference in the Brexit referendum. Instead, they represent differences in broader worldviews that position individuals on one side of a cleavage relating to identity politics. Brexit identities reflect ‘affective polarization based on an opinion‐based in‐group identification’ and shape individuals’ worldviews as they entail an ‘evaluative bias in perceptions of the world’ (Hobolt et al., Reference Hobolt, Leeper and Tilley2021, pp. 1476–1477).

Substantively, Brexit identities reflect underlying political divides ‘between social liberals with weak national identities’ and ‘social conservatives with stronger national identities’ that were mobilized in the referendum (Hobolt et al., Reference Hobolt, Leeper and Tilley2021, p. 1484). Apart from age and education, the strength of national identity is a key predictor of a Leave identity (Hobolt et al., Reference Hobolt, Leeper and Tilley2021, p. 1484). In this sense, Brexit identities also relate to the rise of the cultural dimension in politics across Europe and North America (Hobolt et al., Reference Hobolt, Leeper and Tilley2021, p. 1484) and to a broader cleavage that is reshaping public attitudes towards international cooperation (de Wilde et al., Reference De Wilde, Langsæther and Özdemir2022, pp. 6–7; Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2018, p. 125; Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Lenz and Marks2019, p. 737). This cleavage has been variously described as a ‘transnational cleavage’ (Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2018), a divide between integration and demarcation (Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2006), cosmopolitanism and communitarianism (de Wilde et al., Reference De Wilde, Koopmans, Merkel, Strijbis and Zürn2019) or green, alternative, libertarian versus traditional, authoritarian, nationalist attitudes (Dassonneville et al., Reference Dassonneville, Hooghe and Marks2023; Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Marks and Wilson2002). Although these different conceptualizations of the cleavage in identity politics are not identical, there is a significant overlap (see also de Wilde et al., Reference De Wilde, Langsæther and Özdemir2022, pp. 1–2; Ghassim et al., Reference Ghassim, Koenig‐Archibugi and Cabrera2022, pp. 3–4; Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2018, p. 123). For our purposes, the key shared insight regarding attitudes towards multilateralism is that they concur that such public preferences are shaped by the extent to which individuals hold exclusive national and communitarian identities, as opposed to broader internationalist and cosmopolitan identities.

To the extent that a Leave identity is associated with nationalism and communitarianism, we expect Leavers to be less supportive of multilateral vaccine cooperation than Remainers. These underlying differences determine the strength of the framing effects for the respective groups because motivated reasoning makes individuals more likely to pay attention to and accept information that reinforces their political views (Hart & Nisbet, Reference Hart and Nisbet2011; Strickland et al., Reference Strickland, Taber and Lodge2011). Leavers’ antagonism to constraints on national sovereignty means that a Leave identity should amplify the negative effect of the vaccine nationalism frame.Footnote 6 We can then formulate the following hypothesis with regard to the role of identity in moderating framing effects:

Hypothesis 2: Brexit identities moderate the effect of vaccine frames. The negative effect of the vaccine nationalism frame on support for COVAX should be stronger for Leavers than Remainers.

Party‐political preferences are, of course, an alternative proxy of political identity that may be influential. For example, Milner and Tingley (Reference Milner and Tingley2013, p. 333) suggest that public attitudes towards international aid are shaped by ‘political ideology in the form of the … partisan divide.’ However, as there has been no noticeable difference in cues from political parties in the United Kingdom about international vaccine cooperation, general Left–Right differences or the affinity to particular mainstream parties are unlikely to be a more important moderator of the effect of our frames.

Although our theory focuses on Brexit identities as the key mediating factor, we do not exclude that explanations focused on utility maximization may also matter, and we assess them empirically. With regard to vaccine cooperation, age and education appear most relevant in this respect. Age is a key determining factor for health risks in the Covid‐19 pandemic, but how age affects support for COVAX is ultimately an empirical question. While the health risk increases with age, it is not clear if the effect on support for COVAX should be linear. On the one hand, those over 50 are generally at a higher risk of health complications. On the other hand, since COVAX provides vaccines for 20 per cent of the population in all countries, in the United Kingdom those over 65 would likely to be covered. Support for COVAX then depends on how accurately individuals calculate their risk under the respective strategies. If respondents simply use age as an indicator of risk, support for COVAX should be lower for those over 50. If individuals correctly calculate their likely inclusion in the high‐risk group under COVAX, then in the United Kingdom, the age group 50–65 should be least supportive of COVAX as a multilateral approach would delay their vaccination compared to a unilateral approach.

Differences in education levels are associated with popular support for international organizations in general since they determine whether respondents perceive globalization as beneficial to them (Bearce & Jolliff Scott, Reference Bearce and Jolliff Scott2019). Education might then also shape attitudes towards COVAX specifically. Since a key economic benefit of global access to vaccines is the acceleration of a global economic recovery, these benefits may be more clearly perceived by those with higher education who tend to be more aware that economic conditions in one country are likely to have spillover effects on other countries. Highly educated individuals should therefore be less susceptible to the effects of the vaccine nationalism frame.

The survey experiment

To evaluate our hypotheses, we conducted an online survey experiment on 4,144 respondents in the United Kingdom in September 2020. The experiment was embedded in DeltaPoll's Omnibus survey.Footnote 7 The sample is representative of the national population based on age, region, gender, education, political interest and vote in the last election and the 2016 referendum on EU membership. The experiment included three treatment groups and a control group. The first two treatment groups were presented with one of the two opposing frames – capturing vaccine nationalism or international cooperation, respectively. To examine the effects of equal exposure to the competing frames, the third treatment group received both frames.

All four groups were first provided with the following general background information on COVAX:

The World Health Organization (along with other organisations) has set up a Covid‐19 vaccine facility, known as COVAX, and invited countries to invest in its portfolio of potential vaccines. The aim of COVAX is to avoid a situation in which only a few countries are able to access global supplies of vaccines and to ensure access for the people most at risk in all countries.

Countries are encouraged to purchase vaccines through the COVAX facility rather than through direct advance contracts with manufacturers. The payments by richer countries will cover vaccines for their own country, while donor funding will subsidise vaccines for poorer countries.

In a first phase, vaccines will be allocated to all participating countries to cover at‐risk groups in each country (roughly 20% of the population). In a second phase, allocation of vaccines will prioritise those countries at greater risk from the spread of Covid‐19.

This general information was needed because, at the time of our experiment, COVAX did not feature extensively in the media and political elites’ discourse. Our wording of the frames below presents general benefits of vaccine nationalism and international cooperation, respectively.Footnote 8 It is, however, worth noting that actual arguments presented by key actors closely resemble those captured by our frames. The absence of a highly visible public debate at the time of the experiment is helpful as it minimizes the risk of considerable prior exposure to similar frames that may affect our results. The wording of the two competing frames is reproduced below:

Vaccine nationalism frame

Some argue that the UK government should prioritise direct advance contracts with selected manufacturers over COVAX. Direct contracts would ensure that the UK swiftly obtains enough vaccines not just for its high‐risk groups, but for everyone in the country who might want to get vaccinated. The UK should first secure vaccines for everyone in the country, and then help to finance access to vaccines for high‐risk groups in other countries.

International cooperation frame

Some argue that the UK government should prioritise COVAX over direct advance contracts with selected manufacturers. Investment in COVAX would reduce the risk of backing unsuccessful vaccine candidates, and it would help restore the UK economy by reducing the disruption of trade and travel. The UK should first help to secure vaccines for high‐risk groups globally, and then seek to obtain vaccines for the rest of its population.

The third treatment group received both frames (the order in which the two frames were received by this group was random). The groups, therefore, differ only in the framing information that they were exposed to. Our dependent variable is whether respondents favour the United Kingdom's participation in COVAX over a unilateral approach. Specifically, we asked the following question:

Which strategy do you think should the United Kingdom prioritise?

1. The UK should prioritise investment in the COVAX facility.

2. The UK should prioritise direct advanced contracts with selected manufacturers.

3. I do not think that focusing on vaccination is the right strategy.

4. Don't know.

As outlined above, we expect Brexit identities to moderate the effects of our frames. Therefore, prior to the treatment, we asked respondents an additional question about these identities. The wording replicates the question asked in the NatCen and British Social Attitudes surveys (Curtice, Reference Curtice2018; Curtice et al., Reference Curtice, Clery, Perry, Phillips and Rahim2019):

Thinking about Britain's relationship with the European Union, do you think of yourself as a ‘Remainer’, a ‘Leaver’, or do you not think of yourself in that way?

Results and discussion

Prior to any treatment, we note an overall strong support among the respondents for COVAX. In the control group, 51.5 per cent of the respondents believe that COVAX should be prioritized, while 29 per cent prefer a unilateral strategy of direct contracts with manufacturers. 6.3 per cent are against any vaccination strategy and 13.1 per cent responded ‘don't know’. This relatively high support for multilateral vaccine cooperation is likely due to the fact that the survey was fielded before any vaccine was approved (the first vaccine was approved in the United Kingdom in December 2020).Footnote 9 The willingness to redistribute resources tends to be stronger when those resources are hypothetical. Moreover, the timing of our survey coincided with high public disapproval of the United Kingdom government's handling of the pandemic (at around 50 per cent). Low public trust in the government's ability to implement a unilateral strategy effectively may have increased the appeal of multilateralism.Footnote 10

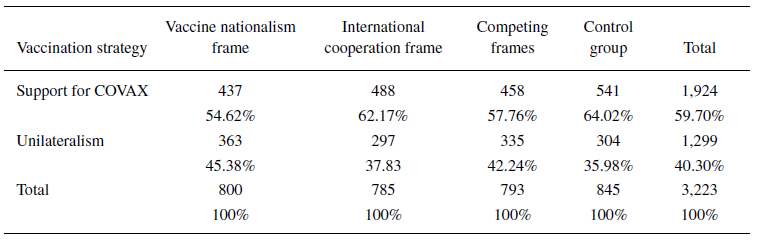

Table 1 shows the frequency distribution for all experimental groups in our sample once we drop the ‘don't know’ and those who believe that focusing on vaccination is not the appropriate strategy.Footnote 11 With support for COVAX being the lowest in the vaccine nationalism treatment group, these descriptive data provide preliminary support for Hypothesis 1a, which expects the vaccine nationalism frame to undermine support for multilateralism. Contrary to Hypothesis 1b, it appears that the international cooperation frame is unlikely to have an effect as support for COVAX in this group is not very different from the control group, although at this stage it is unclear if this difference is statistically significant. Information containing the competing frames appears to reduce support for COVAX, but less so than the vaccine nationalism frame, offering preliminary support for Hypothesis 1c. In what follows, we examine in more detail whether the differences identified in Table 1 are significant and in doing so assess more precisely our hypotheses.

Table 1. Frequency, column percentages

We regressed our dependent variable on a categorical indicator of a respondent's treatment group. The control group is specified as the reference category. As the dependent variable is a dummy variable capturing whether a respondent supports COVAX or not, we use logistic models with post‐stratification weights and rely on marginal effects to provide an intuitive interpretation of the predictions of these models. Given the experimental protocol and the fact that our samples are weighted to be representative, spurious correlation is unlikely to be a problem. The balance tests (online Appendix Table A2) confirm that the groups are similar in terms of key socio‐demographic and political variables.Footnote 12 We, therefore, follow the advice by Mutz (Reference Mutz2011, Ch. 7) to keep the models simple and not to include control variables. However, the results presented below hold when standard controls are included (online Appendix Table A1).

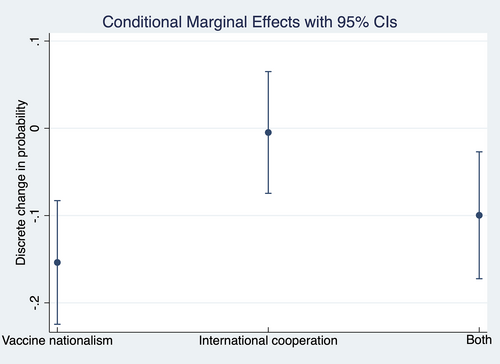

The baseline model shows that both the vaccine nationalism frame and the concurrent frames treatment reduce support for COVAX (p < 0.001 and p < 0.01, respectively), while the effect of the international cooperation frame is not significantly different from the control group (p = 0.893). The difference between the coefficients of vaccine nationalism and international cooperation is statistically significant (p < 0.01), thus further lending support to Hypothesis 1c. Figure 1 displays the marginal effects, which capture the difference in the probability of supporting COVAX between the treatments and the control group. In line with Hypothesis 1a, the vaccine nationalism frame reduces support for COVAX by more than 15 percentage points (p < 0.001). At the same time, the international cooperation frame has no significant effect (p = 0.893), with the likelihood of support for COVAX in this group roughly comparable to the control group. The combined frames treatment also reduces support for COVAX, as expected by Hypothesis 1c. Support among the respondents who received this treatment is almost 10 percentage points lower than in the control group (p < 0.05).Footnote 13 On the whole, these findings lend support to our expectation about the ability of frames to activate in‐group bias and the preference for short‐term solutions in crisis situations.

Figure 1. The impact of the frames on support for COVAX, marginal effects. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

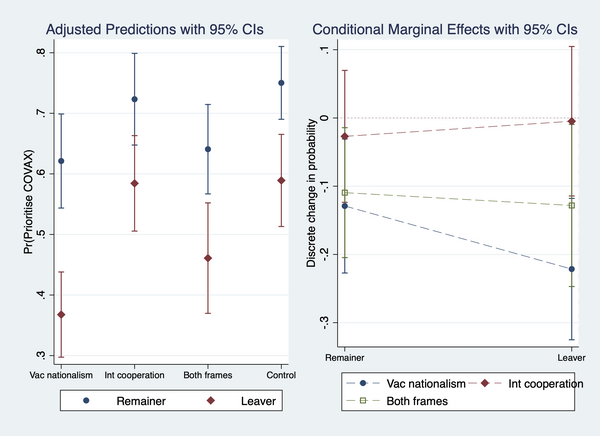

Next, we turn to the model that examines the conditional effects of Brexit identities. This model includes the interaction term between the Brexit identities and the experimental groups.Footnote 14 While the interaction term is not significant in log odds (online Appendix Table A1), it is in terms of differences in probabilities. This is not unusual in non‐linear models (Karaca‐Mandic et al., Reference Karaca‐Mandic, Norton and Dowd2012). As Ai and Norton (Reference Ai and Norton2003) explain, the cross‐partial effect may be different from zero even if the coefficient of interaction equals zero and any interaction should be evaluated through marginal effects. Figure 2 shows the predicted probabilities and marginal effects of the framing treatments for each Brexit identity. Our expectation, as outlined in Hypothesis 2, is that a Leave identity amplifies the negative effect of the vaccine nationalism frame on support for multilateralism.

Figure 2. Predicted probabilities and marginal effects of support for COVAX conditional on Brexit identities. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

The results support this expectation. The first panel in Figure 2 shows that while the vaccine nationalism frame reduces support for COVAX overall, the drop in support for Leavers (in comparison to the control group) is particularly pronounced. The predicted probability of Leavers supporting COVAX when exposed to the vaccine nationalism frame is only 0.37, compared to 0.62 for Remainers, a 25 percentage point difference. The difference between Remainers and Leavers is also evident in the group that received the competing frames, but here the difference is lower and equals 18 percentage points, roughly comparable to the difference we find in the control group (17 per cent).

The second panel with the marginal effects shows more clearly both the size and the statistical significance of the effect of the framing treatments for each Brexit identity. The interaction effect is the difference in the marginal effect of the treatment on the likelihood of supporting COVAX between Leavers and Remainers. Moving from the control group to the vaccine nationalism group reduces the probability of support for COVAX by 22.1 percentage points for Leavers (p < 0.001) and only 12.9 percentage points for Remainers (p < 0.01). This confirms the logic of motivated reasoning, as congruent information has a stronger effect: Remainers are evidently much less affected than Leavers by the frame that emphasizes benefits of unilateralism. The interaction between Brexit identity and the combined frames treatment is also significant, but the difference in the marginal effects for Leavers and Remainers (12.8 and 10.9 percentage points, respectively, p < 0.05) is considerably smaller. The marginal effects of the international cooperation frame are not statistically different from the control group for either Leavers or Remainers.

Taken together, these findings confirm our hypotheses about the varied effects of the different frames. The vaccine nationalism frame has the strongest impact and this impact is further amplified for Leavers. This effect is also evident, albeit to a lesser extent, in the combined frames treatment, where the vaccine nationalism frame evidently trumps the international cooperation frame. Still, the absence of any positive effect of the international cooperation frame alone deserves an explanation. While our theory provides reasons for the dominance of the vaccine nationalism frame, the lack of the effect of the international cooperation frame that we observe may be partly due to a ‘ceiling effect’. The control group, as discussed above, already exhibits strong support for COVAX, particularly among Remainers, which reduces the scope for a further increase. Arguably, differences in the strength of the frames may also explain the lack of the positive effect of the international cooperation frame. However, there is no reason to believe that this frame is intrinsically weaker than the vaccine nationalism frame with regard to the arguments it entails. Indeed, one could argue that the long‐term benefits of multilateralism outweigh the short‐term benefits of unilateralism. Also, multilateralism does not imply that health threats to the national community are ignored, but that they are targeted in a more selective manner.Footnote 15

Further analysis (online Appendix Figure A1) confirms that Brexit identities are a more relevant moderator of the frames than other political identities. With regard to party identities, the difference in the marginal effects of the vaccine nationalism treatment between the supporters of the two main parties is negligible – a drop of 12.4 versus 12.7 percentage points for supporters of the Conservatives and Labour, respectively.Footnote 16 Similarly, with regard to the Left–Right scale,Footnote 17 the difference in marginal effects of the vaccine nationalism treatment between those supporting the parties on the opposite sides of the spectrum is only 3.2 percentage points.

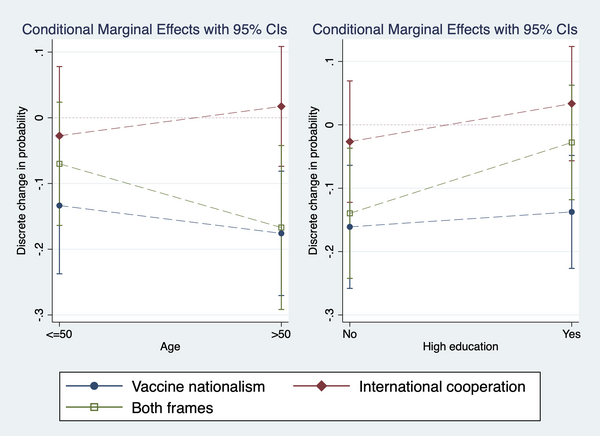

Finally, we consider the moderating effect of age and education as alternative explanations. Figure 3 shows that only the marginal effects of the vaccine nationalism treatment are statistically significant for all age and education groups. While the drop in support for COVAX is somewhat larger for those over 50, the difference is only 4.2 percentage points. Similarly, the marginal effect of the vaccine nationalism frame for those without a university degree is slightly larger than for those with a degree, but the difference is only 2.4 percentage points. This suggests that age and education are less important moderators of our frames than Brexit identities.Footnote 18

Figure 3. Marginal effects of support for COVAX conditional on age and education. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

However, it is possible that education and age influence the outcomes in a more complex way. Both are predictors of the Brexit identities (Hobolt et al., Reference Hobolt, Leeper and Tilley2021, p. 1484) and are associated with the communitarian–cosmopolitan divide (Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2018, pp. 115–116; Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2006). Thus, these variables may conflate self‐interest considerations and issues of cultural identity. To address this concern, we test two separate models. The first one includes, simultaneously, the interactions between the treatment on the one hand and Brexit identity and education on the other. The second model follows the same strategy for assessing the effects of age, while also capturing more precisely risk profiles of different age groups. Specifically, we distinguish between those less at risk of serious complications from Covid‐19 (<50), those having a higher risk, but unlikely to obtain early vaccines through the COVAX scheme (50–65), and those at a high risk, but likely to have an early access through either COVAX or unilateralism. The results of these models confirm the earlier results (online Appendix Figure A2). Brexit identity seems a more important moderator of the treatment effects than either age or education. The difference in marginal effects for the vaccine nationalism treatment between those with and without a degree is only 1.7 percentage points, while the difference between Leavers and Remainers is almost 10 percentage points. The second model shows no evidence that the effect of the vaccine nationalism frame is the largest for the 50–65‐year‐old group, who objectively should be most concerned that COVAX would prevent them from accessing vaccines early. The marginal effect for this group is not statistically significant (p = 0.180). This suggests that this age group does not accurately calculate that the cost of multilateralism would be the highest for them. Instead, the negative effects of the vaccine nationalism frame on support for COVAX seem to increase with age, with the biggest loss of support evident among those over 65. The marginal effect of this group is 4.8 percentage points lower than for those under 50. At the same time, Brexit identity remains relevant; the difference in marginal effects between Leavers and Remainers is 9.3 percentage points.

Robustness

We test for the robustness of our results in several ways. First, the survey questions were designed to minimize careless answers. The order of all answer options was randomized. Furthermore, to prevent inattentive responses and ensure engagement with the material, the survey built in a minimum amount of time required to properly read the information prompts. Respondents were not allowed to click and move to the next screen in less than 20 seconds. Respondents who took excessively long to answer the questions were automatically excluded. These measures were taken as response times serve as a reasonable proxy of satisficing behaviour (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Curran, Keeney, Poposki and DeShon2012; Malhotra, Reference Malhotra2008).

Second, to measure respondents’ attention more accurately, we asked a screener question immediately prior to the information prompts. As Berinsky et al. (Reference Berinsky, Margolis and Sances2014, p. 741) argue ‘because attention is a prerequisite for receiving the treatment in most survey experiments, screeners effectively reveal who receives the treatment and who does not.’ Our screener question appears to ask about salient issues facing the country but instructs respondents to type unrelated text (see the online Appendix). We then dropped the respondents who failed this test and reproduced our results on the reduced sample.Footnote 19 The results (online Appendix Tables A4 and A5) confirm the general findings presented above, albeit the marginal effect for Remainers in the treatment group that received both information prompts is not significant at the conventional levels. Not surprisingly, the effects of the treatments are somewhat stronger: the marginal effects in the baseline model show that the unilateralism treatment decreases support for international cooperation by 17.7 percentage points, compared to 15.4 percentage points in the original analysis. However, we follow advice by Berinsky et al. (Reference Berinsky, Margolis and Sances2014) not to restrict our analysis to only those who pass the screener test, as screener pass rates tend to correlate with politically relevant characteristics, such as education, race, age and gender.

Finally, we use a more demanding manipulation check immediately after the dependent variable question, which aims to assess respondents’ comprehension of the treatments. Respondents were asked to identify the argument(s) they saw in the information that was provided (see the online Appendix). Heeding the warning from methodologists that manipulation checks may affect responses regardless of whether they are placed before or after the dependent variable question,Footnote 20 we do not treat this as a definitive test, but rather as an addition to the other robustness measures. Given that the comprehension test is more demanding than the screener question, we removed only those respondents who chose a clearly incorrect answer, while retaining those who were unsure or were only partially correct. The general findings are not appreciably different from the ones presented above, while the effects of the treatments are considerably stronger (online Appendix Tables A6 and A7). The results are robust to retaining only those who offered a fully correct answer.

Conclusions

The governments of HICs, and the United Kingdom in particular, have done little to support a global rollout of Covid‐19 vaccines through multilateral cooperation. Contributions to COVAX have been a minor and complementary aspect of government strategies that have been predominantly characterized by vaccine nationalism. This response has been criticized both for displaying insufficient international solidarity with poorer countries that are less able to obtain vaccines for their populations and for its short‐sightedness in delaying the recovery of the global economy and facilitating the emergence of new variants.

Yet little attention has been paid to what the public thinks about a global vaccine rollout. Does the public support multilateral cooperation through COVAX or is public opinion a constraint on a more far‐sighted and solidaristic approach to global vaccinations? Specifically, we asked if public support can be swayed, both negatively and positively, by cues in public discourse. We also analysed whether respondents’ political identities amplify or reduce the effect of such cues.

Our paper provides evidence that the public in the United Kingdom is far more favourable to a multilateral approach to vaccination than the government. In our survey, a majority of respondents prefer the United Kingdom to prioritize participation in COVAX over direct contracts with manufacturers. Although this support should be good news for proponents of multilateralism, other findings of our survey experiment are more alarming. We show that while there is not much scope for frames in public discourse to increase public support for COVAX, there is considerable scope to decrease it.

We confirm our hypothesis that exposure to a frame emphasizing vaccine nationalism decreases respondents’ support for COVAX. At the same time, exposure to the frame presenting arguments in favour of a multilateral approach has no significant effect. The negative effect of the vaccine nationalism frame also occurs when respondents are concurrently exposed to both frames. We explain this finding with reference to the crisis situation and the national emergency that the Covid‐19 pandemic represents. As the vaccine nationalism frame emphasizes the risk for the national community, it activates for respondents the sense of a crisis in which they find themselves. Drawing on social psychology, we suggest that in such a situation, respondents are more likely to make risk‐averse choices associated with short‐term solutions. In addition, the vaccine nationalism frame triggers an in‐group/out‐group dynamic that makes respondents more likely to favour a strategy that prioritizes the protection of the lives of members of the national in‐group over geographically more distant out‐groups.

If information about the long‐term benefits of COVAX is unlikely to increase public support, does this mean that pro‐COVAX campaigns to foster public support are a waste of resources, and that attempts to change government policy through public opinion pressure are doomed? This pessimistic interpretation may be premature. Our findings indicate that public campaigns by Gavi, the WHO, or other advocacy groups can still play a role. Even if information about the benefits of international cooperation does not increase support for it significantly, such information may act as a buffer to the vaccine nationalism discourse. Our findings suggest that treatment with competing frames may have an attenuating effect. While exposure to the vaccine nationalism frame is always likely to decrease support for multilateralism, this effect may be reduced if respondents are also exposed to the international cooperation frame. Thus, public campaigns aimed at increasing support for multilateralism in vaccine distribution may not be futile. While they are unlikely to mobilize additional support among the public (which is already favourably disposed towards multilateralism), such campaigns may dampen the detrimental effect of nationalist discourses that advocate prioritizing full vaccination of the national population over equitable access to vaccines for the most vulnerable globally.

At the same time, our findings also suggest that respondents are more receptive to some information cues than to others, depending on their political identities. In the United Kingdom, Brexit identities are strong predictors of support for COVAX and amplify the effect of frames: Leavers are more susceptible to the negative effect of a vaccine nationalism frame than Remainers.Footnote 21

Although our survey covered the United Kingdom only, our findings about framing effects in a crisis should apply more broadly. Since short‐termism and in‐group bias reflect established regularities in human behaviour in times of crisis, cues promoting unilateralism should be expected to be more effective than appeals for multilateralism in national emergencies elsewhere. The argument about Brexit identities may be more specific to the United Kingdom. The strong polarization in identity politics may make the United Kingdom a most likely case for identity as an amplifier of public cues about international cooperation. However, such polarization is certainly not unique to the United Kingdom. Other advanced democracies have also experienced sharp increases in polarization (Gidron et al., Reference Gidron, Adams and Horne2019; Reiljan, Reference Reiljan2020) and in the salience of a cleavage between cosmopolitanism and communitarianism (de Wilde et al., Reference De Wilde, Koopmans, Merkel, Strijbis and Zürn2019; Hobolt et al., Reference Hobolt, Leeper and Tilley2021, p. 1484; Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2006). Hence, while our argument about the negative effect of nationalist frames should be applicable more generally, the amplifying effect of political identity should be particularly evident in countries that exhibit high levels of polarization that centres on the division between cosmopolitanism and communitarianism. Finally, as discussed earlier, the government's crisis management may be specific to the United Kingdom case. However, the more general point is then that low public approval of government crisis management may increase the likelihood of support for multilateral solutions to a crisis.

While the paper's findings draw on public opinion during an earlier stage of the Covid‐19 pandemic and governments have since made their choices on vaccination strategies, the policy implications remain relevant beyond this period. Governments will be forced to confront again the question of a multilateral or unilateral approach to vaccine development and vaccination. First, even as the current pandemic subsides, new variants can continue to emerge. Variants that are resistant to current vaccines may require the development and distribution of new vaccines. Second, medical experts and commentators have warned that the world may face future pandemics far worse than Covid‐19 with much higher rates of fatalities or severe diseases (Barnes, Reference Barnes2022; Gregory & Elgot, Reference Gregory and Elgot2021; Kuchler, Reference Kuchler2022). Finally, at a special session of the WHO World Health Assembly in December 2021, the WHO member states agreed to start negotiations on a new global pandemic preparedness treaty, which could include legally binding rules to improve equitable global access to vaccines (Jack, Reference Jack2021; Thirty‐two Ministers of Health, 2021; Wenham et al., Reference Wenham, Eccleston‐Turner and Voss2022). In the United States, nationalist‐populist contestation of a potential pandemic treaty has already started (see e.g., Carlson, Reference Carlson2022). Maintaining or obtaining public support will be a key consideration for international institutions, advocacy groups and governments in HICs as they confront these ongoing and future global health challenges.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge funding for the survey experiment from the LSE's International Relations Department. For extremely helpful comments and suggestions, we would like to thank the three reviewers for EJPR, as well as Charlie Carter, Anna Getmansky, Mathias Koenig‐Archibugi, Karen Smith, and participants at the LSE International Relations Department's workshop on International Institutions, Law, and Ethics, and at the Society for the Advancement of Socio‐Economics 2021 conference.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article: