The title of this book, The Power of Peasant Consumers, might be seen as surprising to some. Arguably, individual consumers seem insignificant in any given economy as compared to more clearly powerful agents, like large companies, public institutions, and other more visible entities. ‘Consumers’ is a term that includes a wide range of people, from old women to young boys, from the humble to the well-off, each of them with their own incomes and preferences. Yet consumers all together, both in capitalist and pre-industrial societies, have been the basis of any market-based economic system, and consumption its very end. In the interplay between supply and demand, consumers’ decisions and acts prove fundamental for economic growth and development. But, more particularly, the reader might find it shocking that the ‘consumers’ referred to in the title as having power are medieval peasants. This would be understandable. Far too often this social group has been regarded as subject to permanent material stagnation and austerity. It might seem hard at first glance to imagine them concerned with something beyond the search for subsistence, with issues like comfort or luxury. However, our view and understanding of medieval peasants have been modified significantly in the last decade. The long-held general view of the peasantry as a passive social group has been abandoned for a more positive narrative that stresses peasant agency in economic, social, and even political terms.Footnote 1 A better assessment of rural material culture has accompanied this historiographical shift, leading to a more optimistic view of the materiality of the countryside developing in the last two centuries of the Middle Ages.Footnote 2

This book is intended as a contribution to this shift. It is a work about the relation between people and objects; namely, it is about peasants and the utensils they used to store, cook, and eat food between the thirteenth and the fifteenth centuries in the historical kingdom of Valencia (modern east of Spain). First and foremost, though, this is a book about change, in which material culture is studied not only as a topic of interest itself. Food-related possessions will be used as an example to illuminate how peasants acquired these objects, how they used them, and, even, what they meant to them in the course of the late medieval period. The fundamental purpose of this study is thus to contribute to a better understanding of pre-industrial consumption, assessing the contribution of peasants to the constitution of a consumer economy in the late medieval period. In line with the more positive view that characterises current historiography, this book argues that medieval peasants experienced a notable improvement in their material culture, with fundamental socio-economic implications. It will be shown, ultimately, that many features of modern consumer societies are rooted in the later Middle Ages and, more importantly, that rural societies were a constitutive agent of this historical process. In the last centuries of the medieval period, peasants became, effectively, powerful consumers. Their actions not only changed their material culture irreversibly: they underpinned the general development of a leading Mediterranean economy.

Three Concepts in One: Material Culture, Consumption, Living Standards

This is a work of economic and social history widely understood, whose arguments are built upon various interpretative paradigms. Economic theory, sociology, anthropology, art history, archaeology, and, of course, historical analysis, have provided conceptual and methodological tools for the exploration of unique medieval written documents, which are at the heart of this research. All in all, this study deals with three major, interdisciplinary, and interrelated concepts: consumption, material culture, and living standards.

Consumption is an ancient matter that exceeds the scope of history as a discipline. Concerns about the way people acquire goods and thus their implications for the whole of society and economy can be tracked as far back as ancient Greece or even earlier.Footnote 3 As a modern field of enquiry, it was born alongside industrialisation and capitalism. The earliest references emerge in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century works by David Hume, Adam Smith, David Ricardo, and Karl Marx. These are just some of the many outstanding writers who addressed ‘consumption’ – and/or its harmful counterpart, ‘consumerism’ – as a distinctive feature of contemporary Western Europe. Their subsequent influence on the many disciplines within social sciences has resulted in scholars approaching consumption from different and often divergent angles. What motivates individuals to purchase certain goods and services over others is conceived in radically different ways among economists, sociologists, anthropologists, and philosophers. For some, consumption is in line with social status, hierarchy, and inequality. For others, it is about representation, identity, and symbolic communication.Footnote 4

Consumption as an instrument of social power is profoundly inspired by Marxist thought. This view was particularly prominent in the social sciences until the 1970s. Well-known concepts such as Thorstein Veblen’s ‘conspicuous consumption’ and Pierre Bourdieu’s ideas of ‘habitus’ and ‘distinction‘ were largely inspired by it. For them, consumption patterns fixed individuals within social groups and reproduced inequality, as a means of cultural capital. Theodor Adorno, Max Horkheimer, and Herbert Marcuse were inspired by this view too, particularly in their critical view of society being led by ‘mass consumption’, ‘consumer culture’, and ‘consumerism’. Advertising and the media were manipulative tools that urged society to satisfy false needs, encouraging conformism and the acceptance of the bourgeois lifestyle among the working class. Since the 1970s, though, anthropologists such as Mary Douglas and Baron Isherwood argued for a more positive conception. Consumers were not manipulated, gullible beings but active ones whose actions made sense within a complex system of cultural meanings. Purchasing ordinary objects is far from a senseless, trivial action but a symbolic communication ritual that creates identity and underpins social relationships. Terms such as ‘material culture’, ‘information systems’, and ‘subcultures’ made their way thus into consumption studies, in correspondence with the ‘cultural turn’ in the social sciences.Footnote 5 Economists have been concerned with consumption ever since the discipline has existed as such but tend to address consumers as tied to markets, determined by incomes and prices and, therefore, by purchasing power. Shifts in tastes and preferences are acknowledged to be important but not as decisive as the imperatives of economic forces.Footnote 6

The social sciences have thus not waited for historians to explore consumption. Yet the concerns of these scholars and disciplines are fundamentally about its driving forces, leaving but little attention to it as a process of historical change. How consumption patterns developed in the past and what the relevance of these changes were for the whole of society and the economy are somewhat underplayed issues within this scholarship. A major exception was Werner Sombart’s Luxus und Kapitalismus, a book from the 1920s that argued for an intensification of the search for distinction during the seventeenth century.Footnote 7 But overall, it is fair to say that the historical profession has had to struggle on its own with an essential question: When did we become ‘consumers’? Where was the turning point in history that led to the consumer society in which we live today? Were the societies that lived long before industrialisation and capitalism also ‘consumers’?

Medieval historians have begun more recently to wonder about consumption. Of course, medievalists have felt interest in people’s material culture since before medieval history existed even as a well-defined scientific discipline. Archivists and antiquaries from a number of European countries were interested in these topics as far back as the nineteenth century, as they were among the first scholars to focus on objects. Yet the first time that possessions became more closely involved in the core matter of economic and social history was between the 1960s and 1980s. There were probably four especially influential traditions of scholarship on the topic within that period. The most prominent was that of the second generation of French scholars linked to the journal Annales. Their interest in making a histoire totale included a comprehensive approach to population, family, diet, housing, material culture, and mentalities, as seen in colossal works such as that by Fernand Braudel.Footnote 8 His focus on ‘the structures of the everyday’ and on ‘men and things’, as stated at the beginning of volume one of Civilisation Matérielle, Économie et Capitalisme, inspired medieval Italian and French scholars to a large extent. It was during the 1980s that the well-known book on the fifteenth-century Tuscan peasantry by Maria Serena Mazzi and Sergio Raveggi was published, and Richard Goldthwaite developed his work on luxury and art consumption in the Renaissance. Meanwhile, Georges Duby devoted one volume of a Histoire de la Vie Privée to the Middle Ages.Footnote 9

A particular preoccupation with the issue of living standards stood out in British historiography, forming a second large tradition of scholarship. Since the 1960s, English medievalists became strongly committed to a history of the living conditions of the underprivileged members of society, like peasants, workers, women, and minorities.Footnote 10 The issue of living standards was inspired partly from outside the borders of medieval history, in the debate about the social impact of industrialisation upon the working class.Footnote 11 Contrary to the French and Italian scholarship, material culture was not a particularly prominent aspect in these studies, at least no more than others such as real wages. Regardless, it is in this context that Christopher Dyer wrote Standards of Living in the Later Middle Ages, combining evidence on household expenses, diet, architecture, and material culture for a wide range of social ranks: nobles, artisans, clerics, peasants, and so forth.Footnote 12 The book provided a wider image of the relevance of consumers in an English economy marked by a rising degree of commercialisation.Footnote 13

Meanwhile, in Spain, historians of the Crown of Aragon devoted particular attention to a history of domestic and everyday life. They used a distinctive combination of diverse material, artistic, and written sources, with a view to describing domestic practices of ordinary people. This can be considered a third relevant tradition of studies. Most of these developed during the 1980s, with work by Teresa Maria Vinyoles in Catalonia, which would underpin later work by Flocel Sabaté, as well as Maria Barceló’s on Mallorca.Footnote 14 Valencian historians first felt an interest in objects as part of a wider preoccupation in what one might call a ‘social history of consumption’, essentially concerned with the rural population. Domestic possessions were addressed as a means of demonstrating the internal stratification of the peasantry as a social group. Work by Antoni Furió and Ferran Garcia-Oliver challenged thus the long-held view of ‘lords and peasants’ as monolithic and opposed blocs.Footnote 15

Those decades also witnessed the emergence of medieval archaeology, which can be considered a fourth key body of scholarship. This developed in different countries as encouraged by the proliferation of excavations, in correspondence with the expansion of towns from the 1960s. Very soon specialised journals were launched, particularly during the 1970s – for example, Archéologie Médiévale (1971), Archeologia Medievale (1974), and Medieval Ceramics (1977) – thanks to the accumulation of material, particularly ceramics. It was Italian scholars who made particular claims for the importance of employing this archaeological evidence. Having been taken as an instrument of chronological classification or, as much, as a means of exploring production and technology, they argued for its use as a means of studying consumption patterns.Footnote 16

All that work suggested a shift in consumers’ attitudes during the late Middle Ages in many European regions, aiming ultimately towards an improvement of material conditions. Building materials became solid and long-lasting, while the interior space was split into complex and more specialised rooms. Ornamental objects and furnishings proliferated, while new materials made their way into dressing, kitchen equipment, and tableware. The process was thought to have occurred among a good cross-section of medieval society, including craftsmen and peasants. The proliferation of sumptuary laws, which attempted to stop the lower ranks of society from reproducing the consumption patterns of elites, suggested that a process of social emulation could have taken place in this period.Footnote 17 The way medieval society could enhance its own possessions was mostly suggested by Dyer, relying on estimates on real wages developed by Henry Phelps-Brown and Sheila Hopkins. These arguments were initially founded on an increase in purchasing power, following the milestone of the Black Death (1348). Its demographic shock provoked labour scarcity in combination with deflation, ultimately leading to an upswing in real wages – the ‘Golden Age of the English Labourer’ proposed by Thorold Rogers.Footnote 18 The magnitude and social representativeness of changes in real wages, living standards, material culture, and the notion of the ‘Golden Age of labour’, in England and elsewhere, is currently in a process of refinement and revision that opens new lines for research, with which this book intersects. This will be explained in depth in the next section.

‘Consumer Revolutions’ in Pre-industrial Europe: Rise and Fall of a Historiographical Concept

The Middle Ages were not the only historical period of material improvement before the Industrial Revolution. Work on consumption proliferated significantly in the 1980s and 1990s among early modern historians. This was mostly triggered by Neil McKendrick’s work and the proposed idea of a ‘consumer revolution’ in eighteenth-century England.Footnote 19 Few historiographical concepts have motivated so much research and work. This notion was claimed as the necessary pre-condition for the rising demand that underpinned the Industrial Revolution. Demand and consumption were not unexplored matters, but their historical economic relevance had mostly and traditionally been subordinated to that of supply. Phenomena such as economic growth and economic development were mostly explained by productive aspects. The Industrial Revolution, which implied the increase in the productivity of factors, had been studied as a technological, supply-driven phenomenon.Footnote 20 According to McKendrick, though, eighteenth-century English society enjoyed higher disposable incomes due to the decline of food prices and a rise in the wages of labour. Ordinary people could purchase goods whose prices were traditionally prohibitive and hitherto confined to the homes of the rich. Being imitated by everyone, elites began to acquire consumer novelties so as to distinguish themselves from the bulk of society. This continuous interplay between imitation and distinction was fuelled by new values. Frugality was not ethically desirable anymore, despite having been a moral insistence on the part of Christian ethics. Abundance and opulence could be perceived as socially acceptable and economically beneficial principles, in correspondence with new ideas of individualism rooted in romanticism.Footnote 21

What made McKendrick’s work so popular was the central role it gave to consumption in economic history. His proposals were revelatory for many, as can be seen in the extent of the research – and criticism – they subsequently stimulated. A wave of scholars turned to early modern sources during the 1980s and 1990s to explore the validity of the pillars of the eighteenth-century consumer revolution. It was then that probate inventories, a source that European historians had long been familiar with, came to the forefront of economic history in the search for a rise in household consumption.Footnote 22 By exploring extensive samples of them, Carole Shammas and Lorna Weatherill began to see the origins of rising consumption well before the eighteenth century, finding a rise in people’s possessions from the late sixteenth century.Footnote 23 Other historians stressed that this occurred in a process of general decline in real wages, which should in theory have invalidated any potential rise in material wealth. It was then that Jan de Vries proposed his Industrious Revolution for the first time, a theory accounting for new allocations of work and time within the household that led to increases in disposable income.Footnote 24 Meanwhile, anthropologists stressed the idea of social emulation as simplistic, for it neglected the complexity of values that were thought to have developed in the period and stimulated the process.Footnote 25

The ‘consumer revolution’ was becoming complex in its causes, character, and timing. It was not easy to understand as a ‘revolutionary’ process, with a clear-cut beginning, climax, and end. It seemed that a silent, progressive improvement in material culture had been taking place long before the Industrial Revolution. It also became apparent that it had been a process that took place in other areas of Europe and the world, also in those that did not end up producing an Industrial Revolution. New evidence emerged in the 1990s from early modern inventories that suggested similar images of improving material culture in early modern France, Germany, the Netherlands, and Spain, with work by Daniel Roche, Anton Schuurman, Paolo Malanima, Belén Moreno, Fernando Carlos Ramos, and others.Footnote 26 This scholarship tended paradoxically not to consider the findings of medieval historians, and some work even downplayed the potential medieval origins of this process. Occasional references seemed to be prejudiced against considering medieval ordinary people as consumers, leading to claims that they owned ‘remarkably few possessions’, while referring to the period as the ‘medieval void’.Footnote 27 Still, in some relatively recent books, it is possible to read that ‘it is true that some form of “consumer revolution” has been variously located from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries but not in the medieval period’.Footnote 28 The fifteenth century is at least making its way into some major monographs on the field.Footnote 29 It seems that, as noted by Maryanne Kowaleski, the Middle Ages tend to be regarded as an undifferentiated period in which people were ‘users’, not ‘consumers’, and operated in a world of unchanging material poverty where objects were ‘things’ and not ‘commodities’.Footnote 30

In sum, and despite the claims of some scholars, the late medieval period also witnessed a multiplication of goods that preceded that of the early modern period, a phenomenon that still gains little attention among historical analyses on pre-industrial consumption. Therefore: Was there a long consumer revolution or two separate ones? The doctoral research on which this book is based argued that both processes could have been connected or been the same and, effectively, we should hypothesise a long, progressive process of secular material improvement, with origins in the late medieval period.Footnote 31 English historiography of recent years has also moved towards this notion, suggesting a more ‘evolutionary’ increase in consumption developing across both historical epochs.Footnote 32 The claims for further ‘revolutions’ and the assessment of the validity and implications of the concept, as originally posed by the generation of McKendrick, seem now left aside. The conceptual discussions around the ‘consumer revolution’ appear now to have run out of energy, leaving space for wider views on medieval materiality, connecting the various aspects of domestic life with more ambitious and cross-cutting debates on economic but also cultural aspects.Footnote 33

This book does not argue for the existence of a further consumer revolution during the later Middle Ages. Rather, it seeks to shed light on a set of fundamental issues that remain unsolved but are key to understanding the importance of consumption for the late medieval economy. The first group of questions are about its geographical scope: Where did consumption grow in late medieval Europe? How far did material changes in the south of the continent mirrored those of the north? Were there contrasting regional experiences or was there a common process of material improvement? A second set of questions are about the character of changes in consumer behaviour: Was consumption always in the ascendance during the later Middle Ages? Was it an exponential, uninterrupted process? How great was the increase? Did all objects experience an increase in consumption? If it was a socially widespread process, as seems to have been the case, did all social ranks participate equally? Finally, the most ambitious issues are those concerning the causes and effects: How did medieval society manage to increase consumption and why did they do it? What was the impact of changes in consumer behaviour on the late medieval economy?

The Material Culture of Peasant Food

This work sheds light on these questions by exploring objects that were employed to store, cook, or serve food, owned by Valencian peasants. The objects that fulfilled these conditions are considered here the material culture of food. Consequently, the concept includes amphorae, cutlery, and platters but leaves aside napkins, chairs, and tablecloths. It is important to stress this is not a book on food consumption but on the goods that were involved in such an essential, inescapable activity. Changes in the diets of ordinary people existed in the late medieval period, in Iberia, and everywhere else and help explain why some goods proliferated. As part of the general enhancement in living standards, the traditional centrality of cereals was progressively complemented by a higher contribution of proteins, both meat and fish.Footnote 34 This must have had repercussions on which dishes were cooked and how they were eaten and, as this work will explain, the proliferation of certain specialised wares was probably stimulated by shifts in diet. Yet it would be problematic to attribute the proliferation of some objects only to the introduction of new foodstuffs within the household, since the objects in question had a variety of purposes.

It is a major contention of this work that the material culture of food represents a convenient indicator of changes in living standards. Everyone had to possess objects to fulfil these purposes. Employing a term of household economics, they were all linked by sharing a common ‘utility’ – and that was eating.Footnote 35 This need could be satisfied with a set of several objects, which included various materials and sizes, and were possessed in different quantities. These ranged from robust, resistant metal objects, such as copper pans and iron cauldrons, to fragile earthen plates and glass bottles. The value of these items could also be extremely variable. Wooden spoons, for instance, were affordable products that could hardly have been out of reach for anyone – in fact, some medieval sources, as we will see, refer to them as ‘bargains’. A large clay amphora, conversely, could have been worth more than a donkey. These goods were thus essential, socially wide-spread possessions, which could be in turn sensitive to their owners’ wealth and status. As such, they have great potential in illuminating consumption patterns and how these manifested across different social ranks.

In the homes of ordinary people, like peasants and craftsmen, goods involved in storage, cooking, and serving food accounted for most of material reality. In actual fact, this role was filled by such goods alongside clothing, another set of goods that would well deserve its own book. Pre-industrial societies had thus a much simpler repertoire of material possessions than modern ones, and that provoked the fact that most everyday items related to those two basic needs: food and protection from the elements. A concern with hygiene could exist in medieval housing, but it did not generate significant specialised items. Toilets did not have a presence within the private space – though public latrines seem to have existed in public areas of some medieval towns – and appliances such as washing machines, dish washers, and dryers became widespread in ordinary households only during the second half of the twentieth century. The indispensable electric devices of today’s dwellings, from televisions to tablets, were of course unimaginable. Most leisure activities occurred outside the house, in taverns and in public spaces, and not in isolation within a domestic space. Without electric lighting, most homes were largely dependent on natural sunlight, a fireplace, or chimney, with only a few candles being needed. Addressing the material culture of food means thus to study a great deal of medieval materiality.

It is no coincidence then that these goods have been acknowledged as part of key changes in pre-industrial material culture. During the late Middle Ages, there seemed to have been a proliferation of pewter and earthenware items. Glazed ceramics also made their way into medieval homes, more importantly in the south of the continent, where production centres had a longer tradition of large-scale activity and exportation.Footnote 36 Some have argued for the existence of a new ‘drinking culture’, as seen with new earthen jugs and mugs that have been related in England to a rise in ale consumption.Footnote 37 Spoons might also have become more widespread.Footnote 38 Early modern changes have been far more studied. Characteristic large, metal cooking utensils, such as medieval cauldrons, were replaced by flat-bottom wares. Saucepans, for instance, became popular from the seventeenth century, which could be placed on charcoal hobs, ultimately leading to the disappearance of chimneys as a structure for cooking hot meals in urban houses.Footnote 39 Tableware also developed its style, with the appearance of chinaware and its imitations, such as seventeenth-century Dutch delftware and eighteenth-century English creamware. This applied to a new repertoire of shapes, particularly small items like little spoons, sugar bowls, teapots, and mugs, linked to the rising fashion for tea, coffee, and chocolate drinking.Footnote 40 Cutlery also improved, with the fork finally reaching non-elite houses, although it was still a rarity as late as the eighteenth century.Footnote 41 Changes in storage containers’ consumption are a far lesser known aspect that this work addresses. The reason for including storage items is that they can explain changes in other goods’ typologies. Flagons were very popular in the Middle Ages in Valencia, to the extent that they might have hampered the expansion of cups. In certain periods of this study, earthenware was a rarity in cooking and table service items, but it was not among storage containers. Medieval people from Valencia stored most of their grain, wine, and oil within large earthen amphorae, which makes one wonder why they did not invest more in other clay-made products. These are just some of the many examples that prove how interrelated all these objects were, as well as the need to include storage containers within the range of objects under exploration.

This book goes further in its specificity, focusing on the material culture of food particularly of peasants. It should be taken thus as a work on rural history. This is a major need since novelties in consumption have been traditionally attributed to towns and especially to the larger urban centres. After all, they were where new goods first arrived, where markets were recurrently held, and where the wealthier ranks of society held their residence. McKendrick, Roche, and Braudel thought about changes in early modern consumption as driven by large capitals, such as London and Paris. All change in the countryside has been perceived, in fact, as the result of the influence of towns. Braudel thought of them as ‘electric transformers’ of the countryside, a world whose material culture was largely defined by austerity, tradition, and reluctance to follow fashion and innovation.Footnote 42 As mentioned earlier, though, there is a great deal of evidence showing that peasants were also part of the general proliferation of goods. Exploring their consumption patterns implies studying a social group that composed most of medieval society but is paradoxically much harder to explore than others.

Peasants from a Kingdom in Its Segle d’Or (Golden Century)

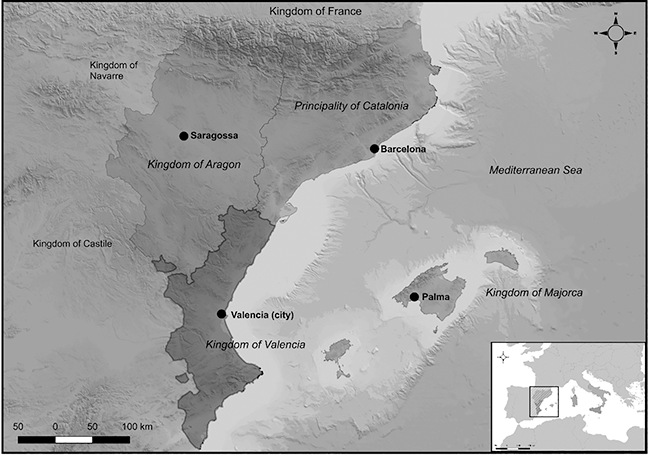

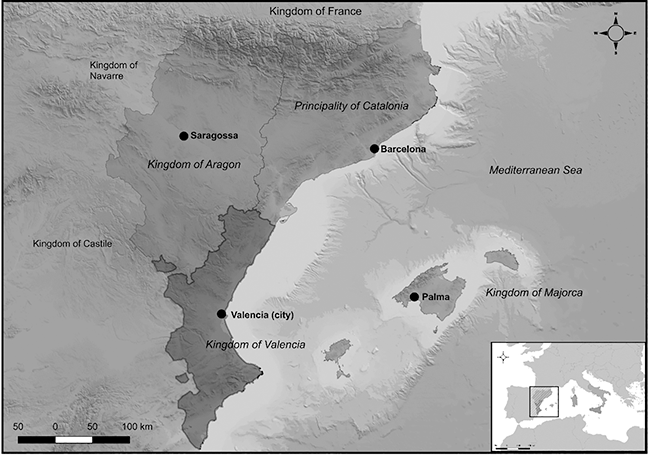

The objects that will be explored belonged to the peasants of a Mediterranean realm: the kingdom of Valencia. This was a political formation that, alongside the principality of Catalonia, the kingdom of Aragon, and the kingdom of Mallorca, was part of the Crown of Aragon, a confederation of realms that represented an economic and political entity of major relevance in Mediterranean Europe during the late Middle Ages. These realms were independent from each other but had common kings and interests, as seen with the existence of shared rights and privileges particularly for trade. Valencia as a kingdom was particularly distinctive for its rapid economic development during the late Middle Ages. Having been created after the destruction of prior Islamic political formations (the taifa or Islamic realm of Balansiya) in 1238 by James I, it soon represented a competitor with Catalonia in the leadership of the confederation during the fourteenth century. It was during the fifteenth, though, when the kingdom reached its Segle d’Or (‘Golden Century’), a concept that stresses the economic, political, and cultural achievements of the epoch. In 1510, the realm possessed 55,700 hearths, that is, some 278,500 inhabitants out of the one million of the Crown of Aragon, while the city of Valencia became the most populated city of Iberia with a population of 9,900 hearths (49,500 dwellers).Footnote 43

Map 1 The Crown of Aragon and the kingdom of Valencia in the fifteenth century

A newly created political entity at the periphery of Christendom became a burgeoning economy in barely two hundred years. Valencian historiography has been prolific in exploring this process, demonstrating that this prosperity can be seen in all aspects of the economy. The agriculture of the kingdom was highly intensive and market-oriented, based to a large extent on irrigational infrastructures that had partly been inherited from the Muslims and expanded by the Christians.Footnote 44 Wheat, vineyards, olive trees, and other traditional Mediterranean crops were grown in combination with commercial ones, such as sugar, saffron, mulberry trees, and textile fibres.Footnote 45 In fact, clothing was the kingdom’s most outstanding industry, based on wool production in the fourteenth century and on silk in the fifteenth. Ceramic industries were also remarkable.Footnote 46 The demand for all these products was both local and foreign, for the kingdom owed much of its economic success to its strategic geographical location, in connecting the exchange networks of inner Iberia with the sea, and thus, the Mediterranean and the Atlantic trade. The city of Valencia was an outstanding port on the route of Venetian and Genoese ships to the north of Europe, which stimulated a flourishing credit and financial culture that not only fuelled its economic growth but also represented a resource that allowed Valencian society to participate actively in the market as consumers.Footnote 47

How far were levels of demand in the kingdom consequently in ascendance? Did household consumption experience a corresponding rise in the context of this flourishing economy? Did the Valencian society benefit materially from the economic upturn of the realm? It cannot be said that Valencian historians have ignored these issues. Juan Vicente García Marsilla has been particularly prolific in showing that diet and some material possessions improved among urban ranks such as merchants and craftsmen, as well as among the nobility. Clothing consumption, meanwhile, seems to show a diversification of fibres, colours, and styles in people’s houses, while new garments such as doublets proliferated. There were innovations also in art consumption. Affordable, small paintings and sculptures were not rarities in the homes of town dwellers, and these seem to reflect a rising taste for non-religious, pagan themes particularly towards the end of the fifteenth century, coinciding with the cultural relevance of the Renaissance. Altogether, his work has led to an enquiry into the issue of fashion and the cultural basis of medieval taste.Footnote 48 Peasants must have certainly been part of this process, since Antoni Furió, Ferran Garcia-Oliver, and Frederic Aparisi have reached similar conclusions studying the possessions of rural society from a number of angles.Footnote 49 These changes were not exclusive to the Crown of Aragon, as seen in work by Jordi Bolòs, Imma Sànchez-Boira, Pere Benito, Carlos Laliena, and Mario Lafuente. Some of these aspects were already pointed out in earlier work on everyday life by Teresa Maria Vinyoles in Catalonia and Maria Barceló and Jaume Sastre in Mallorca.Footnote 50 All these studies are different in their methods and aims. Some undertake a qualitative approach and enquire into the everyday practices of medieval people, while others are more deeply involved in economic history questions. Regardless, they all support the impression that the realms of the Crown of Aragon experienced better material conditions during the late Middle Ages.

Valencian historiography has succeeded in demonstrating the active role of peasants. The commercial agriculture of the realm cannot be solely attributed, as in other European cases, to the entrepreneurship of lords or townspeople but first and foremost to agriculturalists. This was partly supported by the prominence of small land holdings belonging to the tenurial category of enfiteusi, which largely predominated over lease-holding and sharecropping. This implied a virtually absolute ability to exercise decision-making about the land, on what to grow, how to do it, and what to do with the produce. This tenure was the result of the conquest of the land from the Muslims, having been created with a view to urge new migrants to firmly become established in a frontier territory. The ‘youth’ of the kingdom also fostered opportunities for social mobility, from which Valencian peasants profited. This can be seen in the constant migration of young men and women from the countryside to the city of Valencia to become craftsmen and servants, as well as in some of them reaching the status of notaries or other members of the urban elite.Footnote 51

It is important to stress that Valencian peasants were not a monolithic social group. Medieval documents call these individuals llauradors in Catalan (laborator or agricultor in Latin), but the term covered different sorts of agricultural workers, ranging from affluent farmers to agricultural wage-earners.Footnote 52 Valencian llauradors encompassed diverse socio-economic realities, all of which shared the condition of an involvement with agricultural work. The term ‘peasant’ is used in this book, therefore, for historiographical convention, alongside other terms like ‘agricultural worker’ and ‘villagers’. The latter term is used to denote individuals living in villages.

Not all the peasants explored here lived in villages or small populations. The kingdom was a densely urbanised area, in fact, one of the most urbanised in the continent, and that was due to the existence of an extended network of medium-size population centres, each of some 1,000 inhabitants, that structured the country from north to south.Footnote 53 Some of the places that the peasants explored here came from were in fact viles (‘towns’) of the kingdom, such as Alcoi or Vilafranca. Most of their population, though, was involved in agriculture, and some historians qualify them as rural communities.Footnote 54 Even so, peasants (llauradors) could still exist inside the walls of the city of Valencia itself, having their holdings outside them.Footnote 55

Sources

The development of a strong local historiography on the economy of the kingdom makes Valencian peasants ideal as a case study of a Mediterranean society during the final medieval centuries. The abundance of written sources with which to explore peasant objects, including food-related items, is also a notable aspect encouraging their analysis as consumers. The most important documents, which are the basis of this book, are probate inventories, that is, lists of possessions of a deceased person, present in the records of public notaries. These officials had an important presence in Western Mediterranean regions, which was part of a common written and legal culture that dates back to the Roman period. People from all social backgrounds turned to notaries to record all sorts of economic activities and private law matters. Notarial records are large volumes, which cover normally the span of one year of notarial practice. In their pages, a wide range of documents is present, such as debt registries, sale contracts, wills, and inventories.Footnote 56 These are preserved as far back as the thirteenth century in Valencia and other parts of the Crown of Aragon, as well as in Occitania, Provence, Sicily, Tuscany, and other Italian regions. Their abundance here represents a major contrast with England, the Netherlands, Germany, most of France, Castile, and Portugal, where these particular lists of goods are rarely available for the period before 1500.Footnote 57

Yet why were Valencian inventories produced? We currently have a quite clear image of the reasons for their making based on the constitutional law of the kingdom (Furs), as well as from the many lists of goods that explicitly mention the cause for their writing. Most inventories present in notarial registries record goods that formed an inheritance. Ordering inventories was a right every heir had when he or she was about to inherit possessions from a deceased individual. Inheritances could be accepted cum inventarium beneficium, that is, with an inventory of all possessions having been written. If heirs wished to take up this right, they were required to do so when the testament was published by the notary.Footnote 58 This was a way for heirs to check the potential burden of the debts incurred by the deceased in life. This is why inventories record life (violaris) or perpetual annuities (censals) and other debts.Footnote 59 Therefore, an important reason for the making of inventories in Valencia was protection from debt. With the inventory having been written, heirs could decide whether it was worth their while to accept the inheritance or to reject it. The Furs and some of these lists of goods suggest that accepting possessions ‘with the benefit of inventory’ could also mean that the heirs agreed to take on the debts of the deceased only up to the value of the inherited assets and goods.Footnote 60 How such a process operated in practice is unclear and we have not found evidence on how it worked.

In other circumstances, inventories were compulsorily ordered. If heirs were under the age of minority they needed a tutor – who would look after them – and a guardian (curador) – the person responsible for the administration of their goods. Both roles were normally assumed by the same person, who was at the same time tutor and guardian, and had been designated already in the last will.Footnote 61 Testators, most commonly parents of small children, appointed them as heirs and chose a relative as tutor, such as an aunt, grandparent, or the surviving spouse. Valencian Furs established that all tutors needed to thoroughly report their management of the minor’s patrimony. This had to be put on paper, in notebooks that would be handed in to the court of justice where minors lived, in a maximum period of three years from the end of the management of the inheritance by the tutor (tutorship).Footnote 62 This process could only start after the writing of an initial inventory of all the minors’ possessions, without which the tutorship could not legally commence.Footnote 63

The aim of inventories resulting from tutorships was to protect minors from ambiguities in the administration of their patrimony on the part of their tutors. It is for this reason that the Furs considered the situation of minors without elected tutors named in the last will of the deceased. When this occurred, local courts of justice assigned a tutor, who was also required to order an inventory. This was called ‘granted tutorship’ (tutela dativa).Footnote 64 Regardless, tutors could still want to assess with the benefit of an inventory (cum inventarium beneficium) whether it was worth taking on the management of these inheritances, just as heirs could do. Joan Mateu was appointed as guardian of Pasqualeta, the daughter of a dweller of Vilafranca, by the local court of justice. Joan accepted the charge and the inheritance with the benefit of an inventory, ‘stating that the aforementioned minor should give creditors just as much as could be satisfied with the inherited goods’.Footnote 65

The Furs stated other circumstances that required the writing of inventories. If the heir designated by a last will died before the distribution of goods, then the inheritance went to a ‘substitute heir’, a person who was sometimes appointed again in the last will itself, who was also required to order an inventory.Footnote 66 Finally, the constitutional law of the kingdom was also concerned with intestate individuals. Dying without a testament was not per se a situation that forced the deceased’s relatives to order an inventory. In this situation, people followed the conventional succession law, distributing the possessions equally among every descendent. However, if an individual died intestate and no one claimed his/her possessions, these had to be kept for up to two years until someone appeared as the rightful heir. If this did not occur, all goods were inventoried and sold in public auction, with the proceeds going to pious purposes.Footnote 67

The circumstances stated by the law of the kingdom are important but should not be overestimated. Considering inventories from a normative, legal viewpoint shows the relevance of these documents for public institutions. As with wills and other legal instruments related to the succession right, inventories accomplished a fundamental public function in providing juridical security to the transmission of inheritances, which was essential for the reproduction of the wealth and economy of the kingdom. Yet we should stress that family needs were the very basis for their making. Inventories fulfilled, first and foremost, a private, domestic function in being a legal security to which all members of medieval society could turn. Many inventories’ introductory clauses simply indicate they are made to ‘avoid all fraud and trickery’ concerning the goods, either in Latin – ‘cum ob doli maculam evitandam’ – or in Catalan – ‘per esquivar tota frau e engany’ – without further reason being mentioned. Therefore, several inventories could have been ordered just to prevent potential family disputes that complicated a process that should have proceeded ‘naturally’ in accordance with succession and inheritance law.Footnote 68 The transmission of the estate to its subsequent owner could be unclear or simply unacceptable for relatives and other people related to the deceased, regardless of whether a testament had been written or not. Many situations could thus lead to ordering an inventory, many of which can be deduced from the documents themselves. Some of them, for instance, state that the deceased died intestate.Footnote 69 In other cases, relatives were apparently unsure about whether the deceased had left any testament and ordered an inventory to prevent a potential dispute before taking possessions. According to the inventory of goods of Lluís Crespí, a resident of Valencia who passed away at the beginning of the fifteenth century, his sons ordered the document because ‘it is unclear whether the aforesaid Lluís died with a testament or intestate’.Footnote 70 The cause of the ordering of these specific inventories did not have, in principle, a clear place in the kingdom’s law. It was the probative character of inventories that attracted families who wished to avoid potential disputes. In fact, if the inheritance transmission was clear and the new owner was unquestionable, there was no motive to order these documents. This is why many wills stated inventories were unnecessary. Sanxo Favara appointed his wife as his heir in his testament ‘without her having to order an inventory nor any document nor account of the goods to anyone’.Footnote 71

This leads us to consider the procedure of inventory production. These lists of goods were the last point of a process that started with the death of the owner. If the deceased had left a written testament before a notary, its content had to be made public to the relatives within three days after the death. Once there was knowledge of the inheritance at their disposal, heirs were offered a period of three months during which they could request a notary to write an inventory detailing all the goods and properties of the testator. It is unclear whether there was a fixed period of time in the kingdom of Valencia to finish the inventory. It is known that in Catalonia inventories had to start to be written within a month after the death and be finished by two months after it.Footnote 72 If the heirs wanted an inventory, they needed to attend the office of a notary and order it. For notaries, this implied a physical visit to the house of the deceased to write down his/her possessions. Notaries from large cities like Valencia were willing to attend residences in surrounding rural areas, within distances that could be covered in one day’s journey or less. This entailed additional costs that were paid by the client, as can be inferred from a note on a margin of a notarial record of Bartomeu Matoses. Next to the entry of the testament of a peasant from Alboraia, a village next to the capital, the notary wrote that he was still owed six sous ‘for the journey to Alboraia and the stay of half a day’.Footnote 73 Some notaries’ clientele was largely made up of peasants. The customers of Jaume Vinader were mostly craftsmen and peasants from the city of Valencia, as well as villagers from the southern areas of the hinterland of the capital. Most of the inventories in Bartomeu Matoses’s notarial records, meanwhile, were essentially villagers from the northern areas of the city.

Once in the house of the deceased, the notary would begin the listing. Traditionally, it has been thought that notaries moved around the house room by room, writing down every object seen. In fact, if one examines the vast tradition of local works that transcribe some inventories in the south of Europe, there will be found a number of works that describe inventories using very visual terms, considering them ‘pictures’ and ‘stills’ of material reality, as well as ‘mirrors’ to the domestic world. Yet notaries were never alone with the goods, and they did not attempt to write down all objects but only those of the deceased. Since they had no way to know which ones these were, he relied on the information provided by the deceased’s relatives, whose presence during the writing of inventories was required by the kingdom’s law.Footnote 74 At a physical level, notaries wrote down such objects and possessions on small pieces of paper in the house of the deceased. These rough, unelaborated lists were copied in notarial records fully developed, with accustomed formulaic clauses, and disposed of afterwards, although they sometimes appeared folded as fly leaves alongside the inventory entry.

As part of the regular notarial practice, the inventory was copied down on the day that it was taken. This means inventories are included in these records among the many other legal documents notaries certified. Even so, these professionals could still compile inventories in a separate, specific volume. In Catalonia, inventories were eventually collected in libri inventariorum et encantorum (‘books of inventories and auction records’). Although it was more the exception than the norm, in Valencia there existed other compiling practices, particularly, that of collecting inventories with last wills and codicils, in libri testamentorum, also called protocolli testamentorum, inventariorum et codicillorum.Footnote 75 Another possibility was concentrating inventories in books of notals. Notals were the registries that in theory were definitive and gave legal validity to those acts present in basic notarial records (called protocols), although in practice notaries did not copy the entries from protocols in notals in most cases in the late medieval period. Accumulating inventories in notals can be seen in an exceptional example relating to Domingo Joan, in which more than eighty inventories are preserved alongside last wills, marriage contracts, and other documents.Footnote 76 Other protocols include only formulaic preambles of inventories without their content, with notes and indications to find the full list in notals.Footnote 77 Another remarkable case is a protocol of 1369, written by notary Arnau Dalós, which again contains dozens of inventories. This is probably due to the fact Dalós was also ‘scribe of the courts of all villages of Benifassà’, a region in the very north of the kingdom. This volume contains what seem to be copies of inventories that resulted from tutorship, which were copied here en masse as a decision of the notary.Footnote 78 But these cases are rare. Studying Valencian probate inventories thus inescapably involves searching for them across notarial records, flipping pages until a significant number of them has been collected.

The identification of the deceased’s possessions continued after inventories were written. Their final clauses state that if further possessions belonging to the deceased were identified after the inventory was written, these should be notified to the notary and added to the inventory. This led some of these lists of goods to include addenda at the end, with further objects and estates written down about which relatives did not have knowledge when the inventory was first made. In other cases, these addenda took the form of a new document, being included as an entry in a different day of the notarial record. A typical example is the addendum of the widow of Joan Sarriga, a wool-carder (paraire) from Valencia, which was written because ‘I have now learned that other goods belonging to my husband have appeared’. This took place three months after the writing of the first inventory. Most of the new goods included were high intrinsic value objects that were in pawn in other hands, like jewels and items made of silver.Footnote 79 This shows the active role relatives had in ensuring the completion of inventories, even a long time after their writing.

The utility of these documents for medieval society – and for current historians – therefore, lies in the fact that they provide an exhaustive and comprehensive recording of all the possessions of the deceased. Valencian inventories list furnishings, working tools, clothing (dress, bedlinen), jewels, lighting, and, of course, storage, cooking, and table service items. The objects included cover a range of materials, like gold, silver, iron, copper, tin, stone, glass, wood, and earthenware. Materials like clay and wood are commonly recorded, with a variety of qualities that lead us to think that low-value objects were not ignored. In fact, the descriptive thoroughness of Valencian inventories shows that many objects were very deteriorated in the moment they were recorded, being described as ‘broken’, ‘rotten’, or ‘old’. Some foodstuffs appear as well, like wine, olive oil, cheese, garlic, onions, bacon, and grain in stock. Perishable food does not appear, so fresh meat, fish, and vegetables are not mentioned. Water does not appear either, for it was not an economic good in the epoch and thus it could not be purchased, traded, or inherited. Working and farm animals do appear systematically, such as donkeys, horses, pigs, and poultry, often with a statement of their gender and age. Houses, lands, workshops, and other real estate are recorded, as well as annuities, legal documents, and books present in dwellings, whose content is often summarised by the notary. They also include possessions of the deceased in other residences, lent or in pawn, as well as objects that had been sold immediately before the death of the deceased, which were written down to make clear they were part of the inheritance.

These inventories depict thus a vast range of materials and types of possessions of many qualities. There is no reason to believe, in consequence, that these sources might be omitting particular objects or materials systematically. The only relevant aspect that led to a detectable omission of objects was the ownership of goods. In this sense, inventories could neglect possessions that were not legally part of the deceased’s property, like goods in the house that had been borrowed from someone else. Inventories of deceased males record what seem to be dowry goods of their living wives, since they were stated to be ‘of the wife’. The reason for this is that goods that were part of women‘s dowries were legally considered to be owned by the husband while he lived.Footnote 80 Now, this implies that when a woman with a living husband died, her inventory recorded mostly her dowry goods. This explains the partiality of the inventories of many deceased females, which record only liquid money, clothing, or plots of land. Meanwhile, some marriages were not based on the dowry system but on ‘community of goods’ (germania). This model implied that all goods were common between the couple and that these had to be divided equally between the surviving partner and the descendants after the death of one of the spouses. When inventories were ordered in the context of this marriage model, all goods seem to have been recorded irrespectively of the spouse who had passed away.Footnote 81

For the same reason, inventories would neglect the goods that had been legally bequeathed to particular individuals before the death of their owner. Since such goods were legally displaced out of the bulk of the inheritance, notaries had no reason to record them in the inventory. When writing the inventory of Joana, the daughter and heir of a peasant called Joan d’Iprés, notary Jaume Vinader only listed real estate, ‘for movable goods are of the aforementioned Francesca [i.e. the widow] due to a special bequest, as stated in his last will’.Footnote 82 A few more examples show similar cases for the same reason. Notary Bernat Gil neglected intentionally the goods in the ‘chamber’ of the husband of a woman called Mirona.Footnote 83 In the inventory of Pere Guillem Català, a resident of Gandia, it can be read that the wife’s clothes had been bequeathed to her in his last will, so that they had been separated and put inside a chest not to create confusion.Footnote 84 Sometimes notaries were so precise that they did not omit these goods but recorded them and stated they were not part of the inheritance, which means we can be sure that they remained in the house and study them. In the inventory of Esteve Mediona, a notary of the city of Valencia, there is a record of ‘one silver goblet, golden inside, which the aforesaid deceased bequeathed to his aforementioned wife in his last will’.Footnote 85

A second large group of documents on which this book relies are the records of sales of objects in public auctions. These sales were called almonedes in Valencia and were held in large towns as well as in some villages, being the most visible component of an active second-hand market. Crucially, Valencian medieval inventories do not include an appraisal or valuation of the goods in question, so that the subsequent transactions of such goods in this market provide us with the sale prices – and therefore market value – of inventoried items. These auctions were ordered by relatives of the deceased to obtain cash to pay inherited debts or pious expenses. These almonedes can be found in notarial records themselves, often following a corresponding inventory. Other auctions were ordered by judicial authorities when selling goods previously seized for debtors. These can be found not in the records of notaries but in those of local judicial magistrates (justícies). Valencian sources, precisely, are not only exceptional for the huge number of extant notarial records but also for the judicial sources, which are preserved in large quantities from the thirteenth century. These sales, whether of the goods of the deceased or of debtors, thus provide excellent opportunities to explore the prices of food-related objects, which can be used for several purposes for studying their consumption.

It is not the case that Valencian inventories and auctions have remained unexplored in the darkness of archives for centuries. These are well-known sources of which scholars have long been aware and with which they are accustomed to working. Philologists and archivists were the first to study these documents in the Crown of Aragon, doing so from the 1910s. Their work mostly involved transcriptions of individual specimens, frequently with an interest in the language and vocabulary of the period.Footnote 86 Inventories have been employed ever since then for a wide range of purposes, but it was not until the 1980s, once the historiography of the Crown of Aragon firmly developed, that they started to be used to support the investigation of questions in social and economic history. Valencian inventories, particularly, became extensively referred to in the 1980s and 1990s in work on rural history.Footnote 87 The use of these sources, in sum, has been predominantly qualitative and based on small collections or individual specimens. The angle adopted in this book, conversely, is to rely on a very large sample that can be used not only in qualitative terms but also quantitatively.

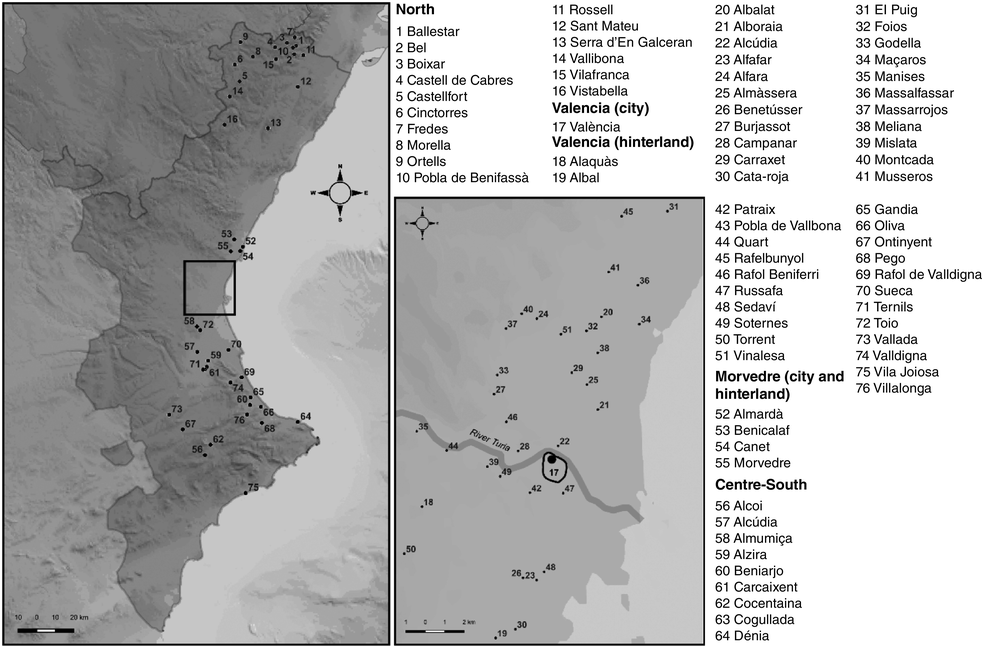

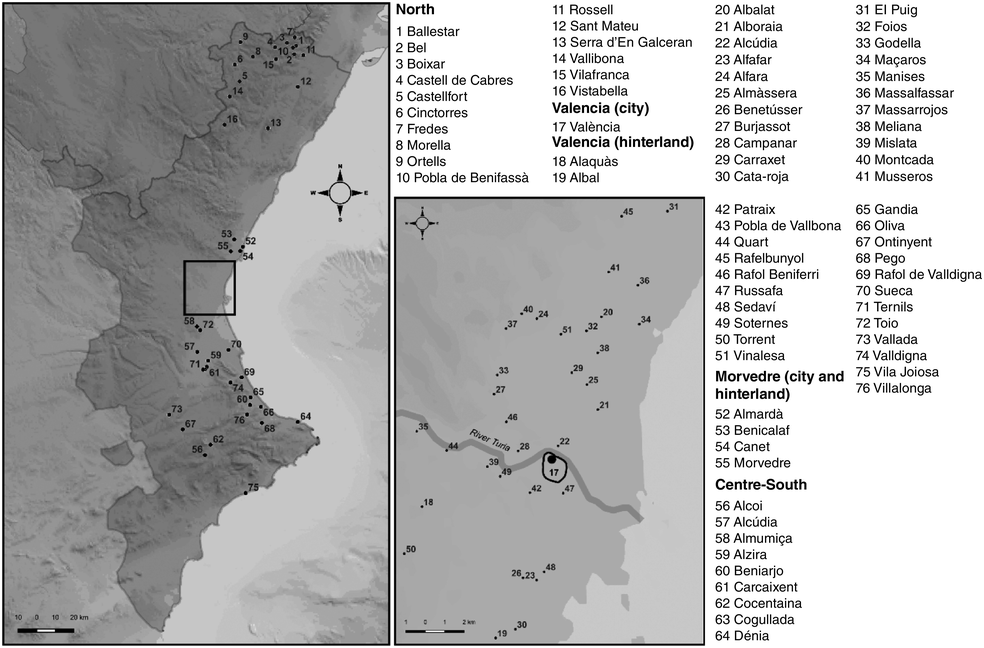

The exploration of 819 notarial records as well as dozens of judicial records has led to a selection of 600 probate inventories and 300 documents with objects’ prices, being mostly auction records. These documents were written between 1283 and 1462. The selected timespan provides thus a unique chance to explore food-related possessions in a chronology that covers most of the late medieval history of the kingdom in a key period of material transformation. This period witnessed the arrival of the Black Death and its recurrences, as well as moments of warfare. It was also during these years that the economic and political splendour of the kingdom of Valencia was evident; its so-called Golden Century (Segle d’Or), a term that refers to the fifteenth century. Since the focus of this book is on material change, the chronological end of the survey has been placed in the 1460s, for inventories of the second half of that century suggest a similar material culture to that evident at the close of this book’s chronology.Footnote 88 The deceased examined had their residence in seventy-six different places across the kingdom, coming from varied areas: the city of Valencia and its hinterland, historically called the horta (‘orchard’); the city of Morvedre (modern day Sagunt) and its hinterland, near to the city of Valencia itself; the central/southern shires (l’Alcoià, la Ribera del Xúquer, la Safor); and northern areas, in the historical border with the kingdom of Aragon and the principality of Catalonia (Els Ports de Morella and La Tenença de Benifassà). These documents come from the major notarial archives of the city of Valencia (APCCV, ARV, AMV), as well as from other archives inside and outside the region (AMA, AMAlz, AMO, AMS, AHN, AHNM, and AHEM). Some unpublished Catalan inventories from Barcelona (AHPB) and Perpignan (ADPO) – modern France but part of Catalonia until the seventeenth century – have also been studied for comparative purposes. The composition of these selections of inventories and auctions will be examined in depth later in this book, in chapters or sections immediately prior to their quantitative analysis. At this point, it is important to stress these locations provide inventories from diverse areas, with a variety of populations and levels of urbanisation.

Out of the 600 inventories only 77 contain explicit references to ‘peasants’ (llauradors, bracers, pastors, or similar terms) in the documents. To these cases we add 255 individuals whose occupation was not specified in their inventories but were residents of villages and small populations with a strong involvement in agriculture. Altogether this makes a sample of 332 peasant inventories. The remainder of the 600 relate to non-peasant individuals, such as merchants, craftsmen, and others. These prove useful for comparisons in many parts of this book. Many food-related objects described in peasant inventories will necessarily be contrasted with those of other social groups to ascertain their uses. In other cases, the differences between rural and urban consumers help in understanding the extent and relevance of changes in peasant material culture. The 300 documents with prices studied, meanwhile, contain the possessions of individuals from all kinds of occupations, peasants or not, which prove of utility in providing the value of many objects possessed by people living in the countryside. It must be noted, regardless, that in nearly all cases we are dealing with deceased Christians. Despite the strong presence of Muslims and Jews in Iberian Chistian kingdoms, including the Valencian realm, it has been not possible to find substantial inventories recording their possessions.Footnote 89 Writing a material culture of them is an important future task for historians, who are most likely to be successful if using judicial inventories, where seizures of individuals of those religions appear.

Map 2 Provenance of the inventories under study

A final aspect to note on the sources employed in this book is that they are essentially textual ones. Food-related objects have an important presence in the material and visual record, but we are not relying here on original archaeological or iconographic material. Rather, this work will study written evidence, and it will try to cross-reference our findings with those of these other disciplines.

Book Outline and Argument

This book is divided into four parts. The chapters of Part I, ‘Material Culture’, are concerned with the everyday practices around food in the peasant home. Part I deals firstly with peasant dwellings in medieval Valencia and the place that cooking and dining occupied in peasant lifestyle. The rest of the chapters deal with the three large typologies of food-related items (storing, cooking, table service). The descriptive potential of inventories and auctions as to the visual appearance of the objects, that is, their size, shape, colour, and decoration, is explored in these chapters in combination with archaeological, iconographical, and literary evidence. The material culture of food depicted by Valencian inventories will show that peasants were preoccupied with far more than subsistence, as they also had an interest in issues like flavour and decorum, and therefore, in enjoyment. These chapters, then, are synchronic and qualitative, defining the culture of food of the peasantry, representing a necessary basis for the remainder of the chapters of the book, which are mostly chronological and deal directly with the issue of change.

The chapters of Part II, ‘Consumption’, are concerned with shifting consumption patterns of food-related objects. This part opens with a chapter that undertakes an in-depth analysis of the sample of inventories under exploration to assess their validity for quantitative use in the light of recent scholarship on this field. This chapter will also explain the method of measuring consumption through the sample of inventories. The other chapters show the dynamics of peasant consumption, with their chronology and dimensions at the level of the kingdom. This is done by studying all goods clustered by their basic typologies as well as by their material. This precise definition of consumption dynamics will allow comparisons with other European experiences hitherto studied, stressing local singularities as well as important connecting points. A chapter will also be dedicated to exploring regional differences in consumption in the kingdom, as well as a further one to comparing differences in consumption between town and countryside and between male and female deceased. In these chapters, changes in consumption will be also contextualised alongside changes in production. This will provide a wider picture of the economic activities and industries of the moment and will help discussion of the role of supply in changes in consumption patterns.

Once a process of material change is identified and measured in Part II, the purpose of Part III, ‘Living Standards’, is to provide an economic explanation of its causes. The first chapter is dedicated to the issue of peasant incomes, showing long-term changes in Valencian real wages in the light of the most recent scholarship. The relevance of other income sources for peasant families, like land and animal ownership, will also be considered. Subsequent chapters of this part turn to the prices of food-related objects, particularly in public auctions. After analysing the sample of documents for this purpose, the value of these items are explored and trends in relative prices established. This will help in assessing how far changes in nominal prices explain shifts in consumption, as well as establishing estimates on household expenditure over time. All in all, it is suggested that a context of rising peasant incomes and agrarian innovation underpinned growing consumption. This part closes with a chapter discussing the relationship between wealth inequality and peasant consumption, assessing how far material changes applied to all the peasantry or just to some strata. This is made by calculating Gini coefficients of possessed items, as well as by dividing peasants into two groups based on the possession of working animals (i.e. oxen, horses, and donkeys).

Finally, Part IV, ‘The Logic of Peasant Consumption’, reflects on what shaped peasant tastes and preferences and how they changed over time. A non-economic, cultural approach is adopted, in which the material aspirations of the peasantry are considered. We turn here to spatial information on the location of objects on display in peasant dwellings, to hints provided by their aesthetic, to contemporary moral and narrative literature and to sumptuary laws. All in all, these chapters assess the relevance of the meanings and agency of objects, as perceived by visitors to houses and by members of the household. Part IV argues that peasants became more attached to their possessions and that that itself was a driving force that created further demand. Their lust for goods fostered the economy but at the same time challenged the principles of medieval society. Fashion and emulation became new sociological realities in which peasants participated. Elites reacted through sumptuary laws, trying to limit ordinary people’s conspicuous manners and by developing a theology against wealth, profit, and imitative consumer attitudes.

All in all, the argument of this book is that the materiality of food improved significantly among Valencian peasants, which mirrored a general improvement in the material culture of the society of the moment. Late medieval consumption was driven by an entangled interplay of economic and cultural aspects, which cannot be understood separately. The case of Valencian peasants and its comparison with other European historical experiences stress local, original material developments and singularities about which much can be learned. We observe how a Mediterranean, Iberian society could afford to live with more possessions and to produce genuine, new material cultures. This was a process that, in turn, fostered the development of local economies.