Impact statement

The world is transitioning toward electric mobility faster than anticipated, but little is known about the environmental impact of electric vehicle (EV) batteries. This review describes 84 peer-reviewed studies that recognized and evaluated each part of the EV battery supply chain – from mining to end-of-life management – in order to show where the greatest impacts are and quantify these impacts. The review found that mining, processing and manufacturing are the most carbon-intensive stages of the battery life cycle, while recycling and second-life applications generate significant opportunities to reduce CO2 emissions and resource consumption.

Recent life cycle assessment research from 2020 to 2025 is compared and analyzed in this review for important data gaps, inconsistencies in methodology, and geolocation inequities, especially in the Global South, where informal recycling and lax regulation create different and significant risks. Collectively, the findings offer a holistic view that supports the development of harmonized assessment frameworks and transparent reporting standards.

The broader social impact of this study is to influence government, business and research to take action toward achieving a robust sustainability profile for EV batteries. It can shift electric mobility toward the principles of a circular economy and cleaner production, while simultaneously coordinating action globally to achieve real environmental benefit from the transition to electric mobility throughout the entire battery value chain.

Introduction

The upsurge in electric vehicles (EVs) has cemented lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) as the linchpin in the global shift to sustainable mobility. However, the swift growth of the battery industry has also raised concerns relating to the environmental sustainability of batteries’ supply chains (SCs). Because battery components are extracted, processed, transported and disposed of over multiple continents, to assess their environmental impacts, a life cycle approach must be incorporated. Each stage comes with distinct sustainability challenges, requiring a strategy that accounts for raw material extraction through to final end-of-life (EoL) disposal. Life cycle assessments (LCAs) have generated notable insights regarding the environmental performance of EV batteries. Unfortunately, there are often too many differences in methodology, system boundaries and regional data availability for meaningful comparison across studies (Picatoste et al., Reference Picatoste, Justel and Mendoza2022).

In particular, contemporary assessments tend to neglect impacts that occur in developing regions (e.g., “informal recycling”) and at the EoL scenarios where infrastructure is weak, and consequently condition impacts are underestimated (Soares et al., Reference Soares, Reis, Vieira, Hernandez-Callejo and Boloy2023). This review seeks to determine which environmental hotspots exist in the EV battery SC and assess how existing literature has evaluated these impacts. The aim of this study is to synthesize peer-reviewed scientific research published between 2008 and 2025, with particular focus on recent contributions from 2020 to 2025, to demonstrate the most significant environmental trade-offs to inform decision-makers in policy, industry and academia. This research seeks to compile and evaluate different environmental assessment methods in order to identify significant impact areas and promote more sustainable practices throughout the EV battery life cycle (Bekel and Pauliuk, Reference Bekel and Pauliuk2019).

The authors used systematic literature review best practices, utilizing the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) methodology and focusing on environmental impacts across the six primary SC stages: mining and extraction, material processing and refining, battery manufacturing, transportation and distribution, use phase and EoL. An assessment of interdisciplinary evidence provides better insight into where the greatest environmental burdens exist and how these can be potentially mitigated through improved assessment practices, regulatory considerations and technological advancements (Iloeje et al., Reference Iloeje, Xavier, Graziano, Atkins, Sun, Cresko and Supekar2022; Tang et al., Reference Tang, Tao, Wen, Bunn and Li2023).

The six SC stages described in this review were derived from synthesizing consistent stage categorizations identified in over 80 LCA studies, in addition to or influenced by accepted structures for LCA from ISO 14040. The review used the established boundaries of the environmental performance system over the life of the product in these six stages – extraction of raw materials, processing/refining, battery production, transportation/distribution, use and EoL/second life – to enhance methodical comparability and consistency in relevant industrial contexts.

Environmental hotspots are geographically concentrated, with major pressures occurring in extraction regions in South America and Central Africa, manufacturing clusters in China and South Korea and emerging EoL management in Southeast Asia.

Methodology

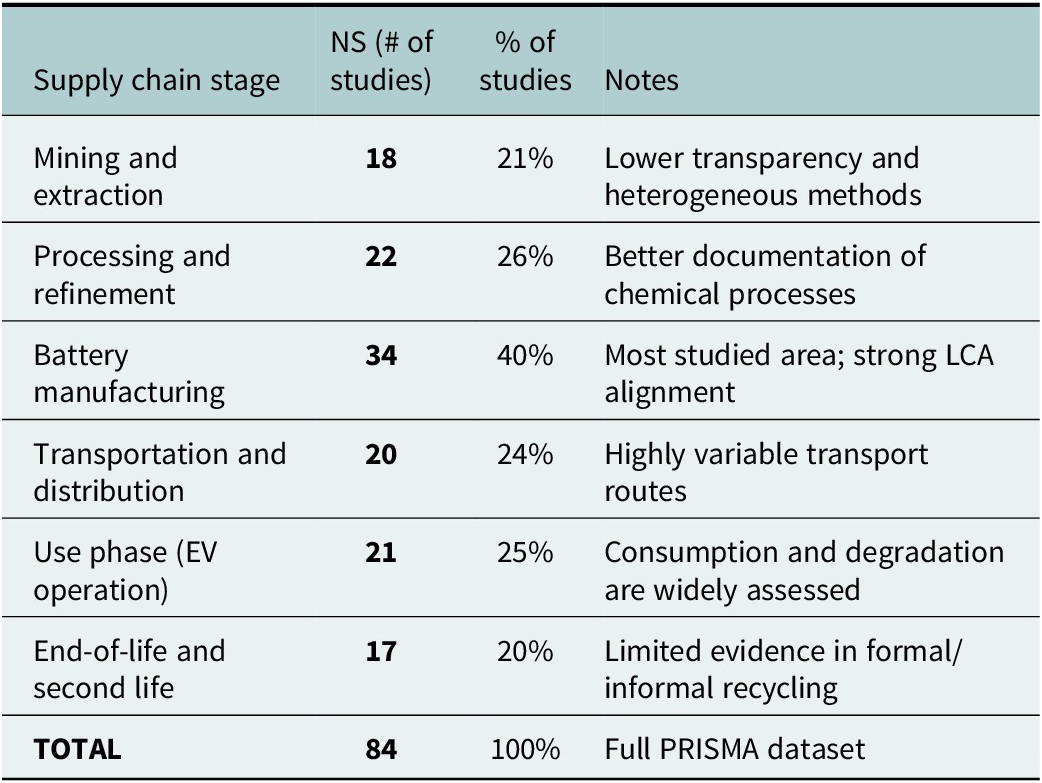

This review utilized the PRISMA guidelines, which are precise and structured approaches to conducting a literature review, while adhering to transparency and reproducibility (Figure 1). The search was performed in three academic databases: Google Scholar, Scopus and IEEE Xplore. The Boolean search strings combined the keywords “EV battery supply chain,” “life cycle assessment,” “environmental impact” and “sustainability,” to obtain the most relevant and recent academic sources. Although the review spans 2008–2025, most contributions (78%) were published between 2020 and 2025, reflecting the rapid acceleration of EV battery sustainability research in recent years.

Figure 1. PRISMA flowchart for EV battery supply chain literature review.

Starting with 120 articles, 22 duplicates were removed, resulting in 98 unique records. The records’ titles were screened for relevance to the EV battery SC, environmental or sustainability assessments, resulting in 86 articles. Next, the abstracts were evaluated, and if there was not a sufficient methodological rigor, or studies did not explicitly outline the environmental impacts, or did not include adequate life cycle considerations, as they related to EV batteries, the studies were removed. This led to a screening step with the identification of 65 articles for full-text review. During the final evaluation and review step, the further exclusion criteria of empirical or comparative studies were added, and whether the study considered one or more parts of the battery life cycle (e.g., mining, processing, manufacturing, use or EoL) were included.

Following citation tracking, backward and forward cited references led to the inclusion of 19 additional relevant studies, resulting in a final sample size of 84 peer-reviewed studies. To reinforce methodological rigor, this review had the defining scope of a “methodologically rigorous” study. Only LCA studies reporting in standard LCA frameworks, reporting specific paradigms of system boundaries and using empirical data were included. Preference given to LCA studies that explicitly communicated key assumptions – electricity grid mix, battery chemistry and product life span – with a greater preference for those that offered dynamic environmental parameters or regions.

To better align methodologies in future LCAs of EV battery SCs, this review recommends a consistent reporting framework. This framework consists of the following: (i) standardized functional units using energy delivered (e.g., per kWh over the battery’s lifetime); (ii) transparent, explicit and consistent system boundaries across the SC; (iii) emissions summarized with full disclosure of LCI sources, systems, assumptions and ranges of uncertainty; (iv) consideration of regional variability, electronic mixes and mining conditions and (v) social governance indicators, including risks of human rights violations and informal handling (especially during mining and EoL). If such aligned practices were adopted, it would enhance comparability among studies, lower instances of contradictory findings and improve the validity of research evidence to support policy, practice and industry decision-making.

The time frame from 2008 to 2025 was intentional. In 2008, the Tesler Roadster was commercially launched, the first highway-legal EV powered with LIBs to go the distance, igniting significant academic and industrial attention to the SC of EV batteries (Manzetti and Mariasiu, Reference Manzetti and Mariasiu2015; Scott and Ireland, Reference Scott and Ireland2020). This incipient turning point provided a foundation to monitor sustainability concerns from the industry’s inception. We selected the upper bound of 2025 to capture the latest trending research, not limited to the pandemic and other global disruptions of 2020 but also salient policy changes, such as the European Union (EU) Battery Regulation (2023), the EU’s Green Deal and the re-focusing of regulatory frameworks, and to analyze the recent discussions on circular economy design strategies for EV battery systems (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Huang and Lin2022; Johnson and Khosravani, Reference Johnson and Khosravani2024; Kempston et al., Reference Kempston, Coles, Dahlmann and Kirwan2025).

This process ensured that the review maintained a variety of historical context and emerging themes, and a breadth of coverage, while also being analytical in its synthesis of the environmental assessment literature in relation to EV battery SCs.

Overview of the EV battery SC

The EV battery SC is a globally linked and resource-intense system comprising many stages that face different logistical and environmental challenges. Understanding the SC in its entirety is critical in working toward more sustainable and resilient supply systems (Gebhardt et al., Reference Gebhardt, Beck, Kopyto and Spieske2022; Rajaeifar et al., Reference Rajaeifar, Ghadimi, Raugei, Wu and Heidrich2022).

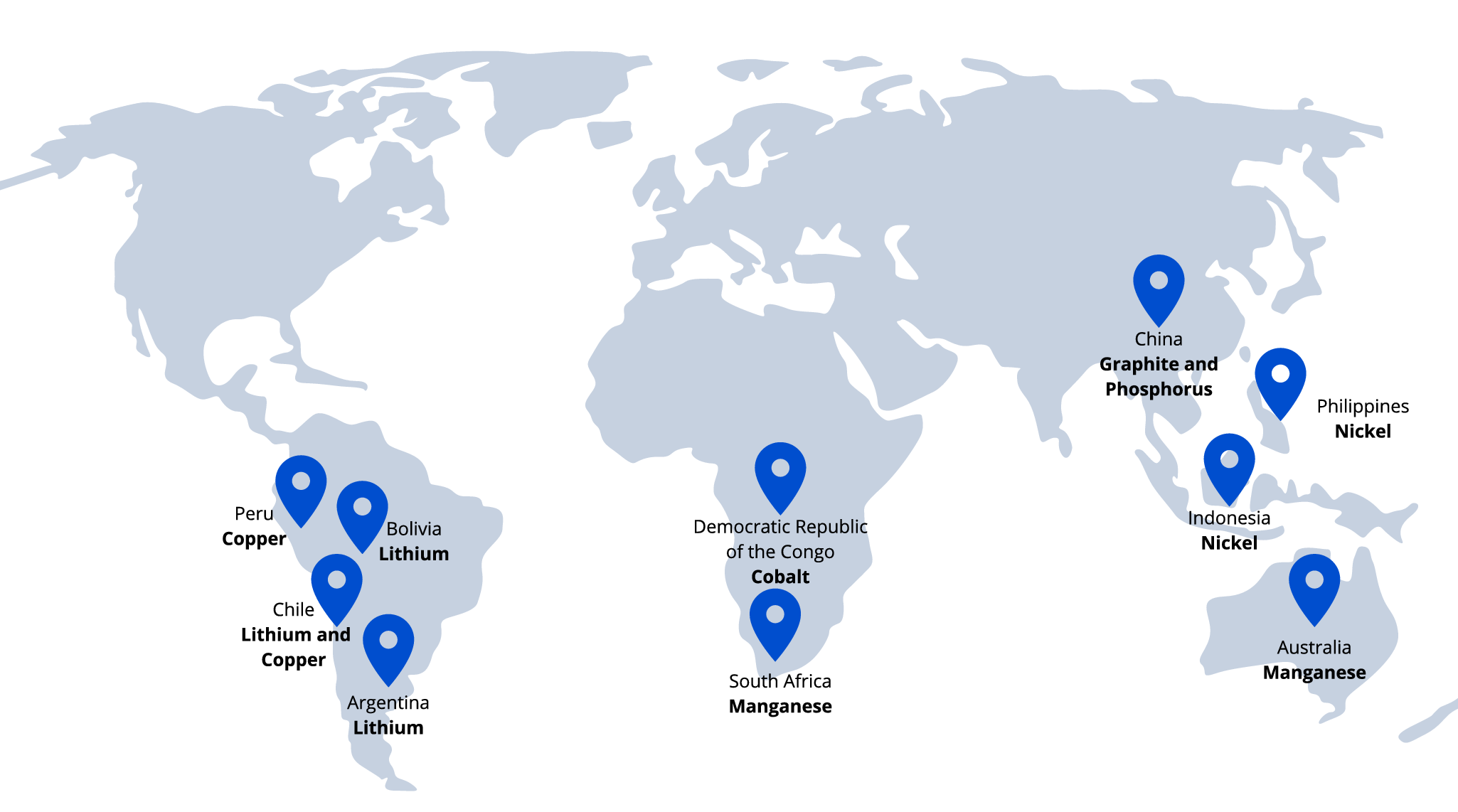

The production cycle begins with the extraction of raw materials like lithium, cobalt, nickel and graphite, which are the basis of LIB chemistry. However, other critical minerals, such as manganese, copper and phosphorus, also play essential roles in battery performance, conductivity and energy density. These materials are concentrated in specific geographic areas, and cobalt is predominantly extracted in the Democratic Republic of Congo (Kaunda, Reference Kaunda2020; Amer et al., Reference Amer, Elmojarrush, Nassar and Khaleel2025), lithium in the Lithium Triangle of South America comprising Chile, Argentina and Bolivia (Peñaherrera et al., Reference Peñaherrera, Davila, Pehlken and Koch2022; Niri et al., Reference Niri, Poelzer, Zhang, Rosenkranz, Pettersson and Ghorbani2024), nickel in Indonesia and the Philippines (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Huang and Lin2022; Amer et al., Reference Amer, Elmojarrush, Nassar and Khaleel2025), graphite and phosphoros in China (Deng et al., Reference Deng, Bae, Denlinger and Miller2020; Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Wang and Negnevitsky2022), copper in Chile and Peru (Niri et al., Reference Niri, Poelzer, Zhang, Rosenkranz, Pettersson and Ghorbani2024; Amer et al., Reference Amer, Elmojarrush, Nassar and Khaleel2025) and manganese in South Africa and Australia (Beaudet et al., Reference Beaudet, Larouche, Amouzegar, Bouchard and Zaghib2020; Amer et al., Reference Amer, Elmojarrush, Nassar and Khaleel2025).

In Figure 2a, world map highlights the countries where essential minerals used in EV batteries are mined, showing the global concentration and global distribution of mineral resources like lithium, cobalt, nickel, graphite, copper, manganese and phosphorus.

Figure 2. Global map of critical mineral sources for EV batteries: lithium (Chile, Argentina and Bolivia), cobalt (Democratic Republic of the Congo), nickel (Indonesia and Philippines), copper (Chile and Peru), manganese (South Africa and Australia) and graphite/phosphorus (China).

In the cell and battery pack manufacturing phase, cathodes, anodes, electrolytes and separators are assembled into cells, which then form modules and packs. Manufacturing is highly concentrated in China, South Korea and Japan because these locations have superior manufacturing infrastructure and economies of scale (Rajaeifar et al., Reference Rajaeifar, Ghadimi, Raugei, Wu and Heidrich2022; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Huang and Lin2022). Manufacturing contributes significantly to embedded emissions, particularly during the electrode-manufacturing and -drying steps.

After production, transportation and distribution connect all parts of the value chain, often through several international borders. Parts are shipped from mines to refineries, from refineries to cell producers and so on to vehicle manufacturers. All these logistics chains add significant emissions, especially when they use shipping by sea or air freight (Barman et al., Reference Barman, Dutta and Azzopardi2023; Busch et al., Reference Busch, Pares, Chandra, Kendall and Tal2024).

At the EoL, the management of batteries allows for sustainable solutions, including options for recycling and second-life opportunities. Although there is limited recycling infrastructure at present, particularly in developing economies, solutions with new technologies are being created to recover high-value materials. A second-life application, such as stationary energy storage for homes or grid support, can extend the serviceable life of batteries and mitigate waste (Peñaherrera et al., Reference Peñaherrera, Davila, Pehlken and Koch2022; Simons et al., Reference Simons, Singh, Hunt and Ermilio2022; Islam et al., Reference Islam, Ali, Qadir, Islam and Shahid2024).

Critical materials will continue to present a lasting threat throughout this chain. The presence of lithium, cobalt, nickel and graphite creates risk due to geographic clustering, price volatility and geopolitical issues (Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Fuchs, Karplus and Michalek2024; Das et al., Reference Das, Kleiman, Rehman, Verma and Young2024). Additionally, the sector has multiple stakeholders, including mining companies, chemical processing, cell and module manufacturing, auto manufacturers, shipping companies and recyclers, that operate on multiple continents and in different regulatory, economic and ethical environments (Agrawal et al., Reference Agrawal, Angelis, Thakur, Wiktorsson and Ravi2021; Gebhardt et al., Reference Gebhardt, Beck, Kopyto and Spieske2022).

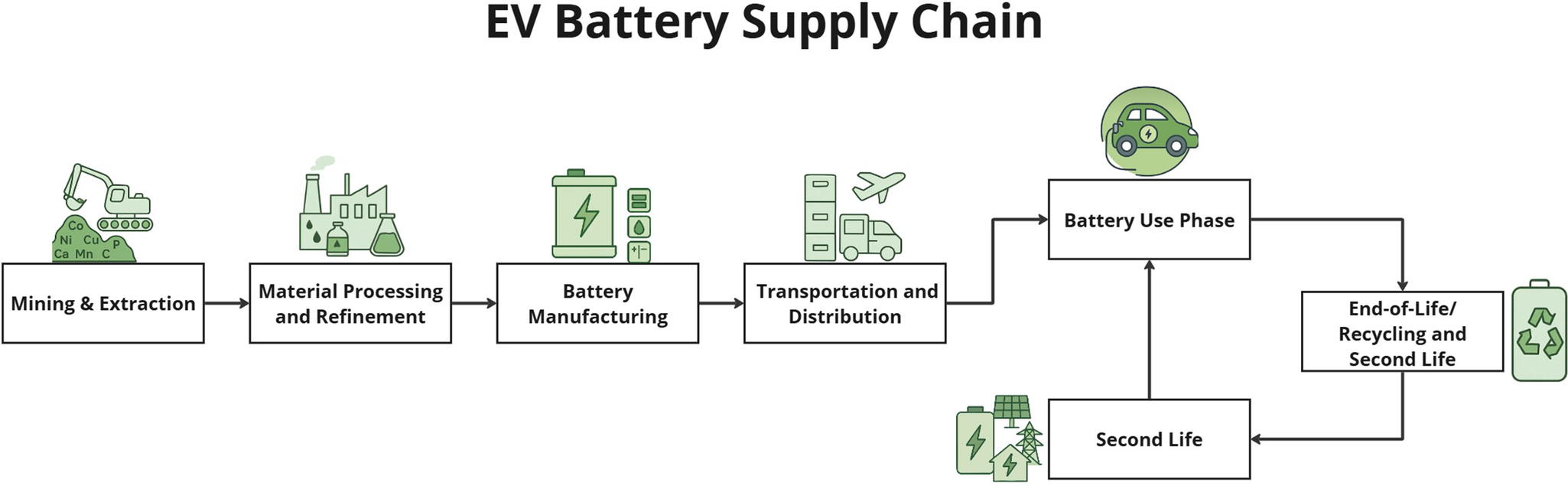

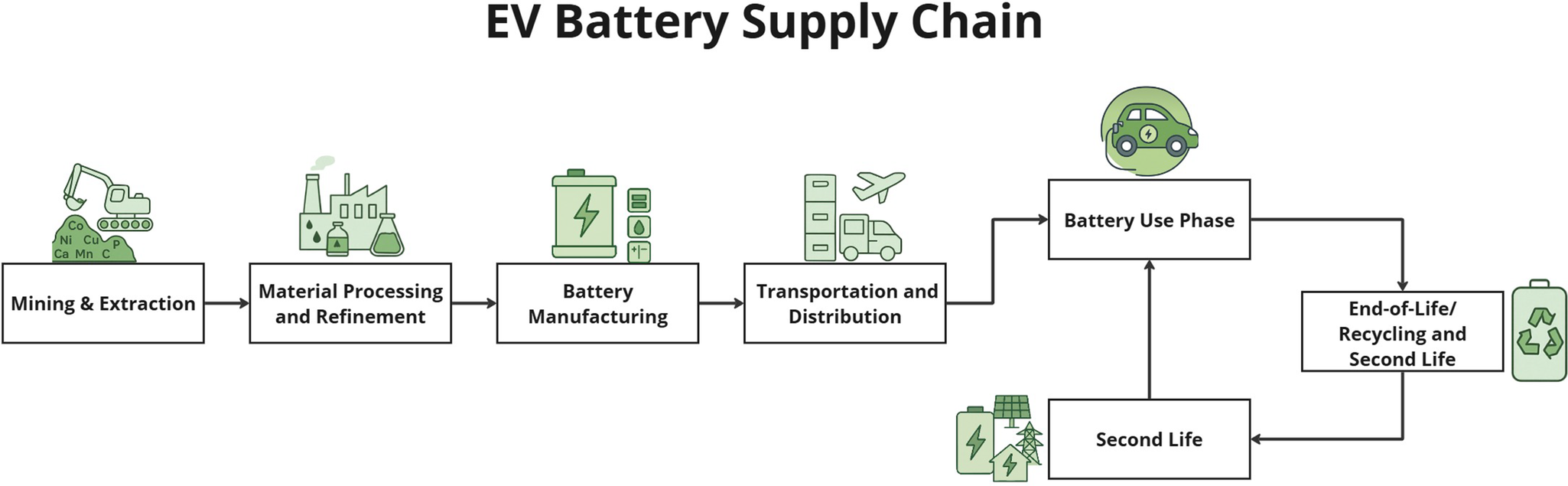

Figure 3 provides a view of the EV battery SC, optimistically framed as a circular SC. The circular SC is based on a “ground to grave” concept or SC model that incorporates every process involved in a battery’s life cycle, from the extraction of raw materials to the reuse, recycling and, ultimately, the disposal of the battery. The use of a circular SC implies working within the framework of second-life and recycling loops that recover resources rather than eliminate them, and have the potential to lessen environmental impacts, as long as this process is properly stewarded.

Figure 3. EV battery supply chain.

Understanding each of the interconnected stages and actors in the circular SC is an important first step before exploring the subsequent sections that focus in deeper detail on the associated environmental impacts, trade-offs associated with the environmental impacts and sustainability strategies.

Environmental impacts by SC stage

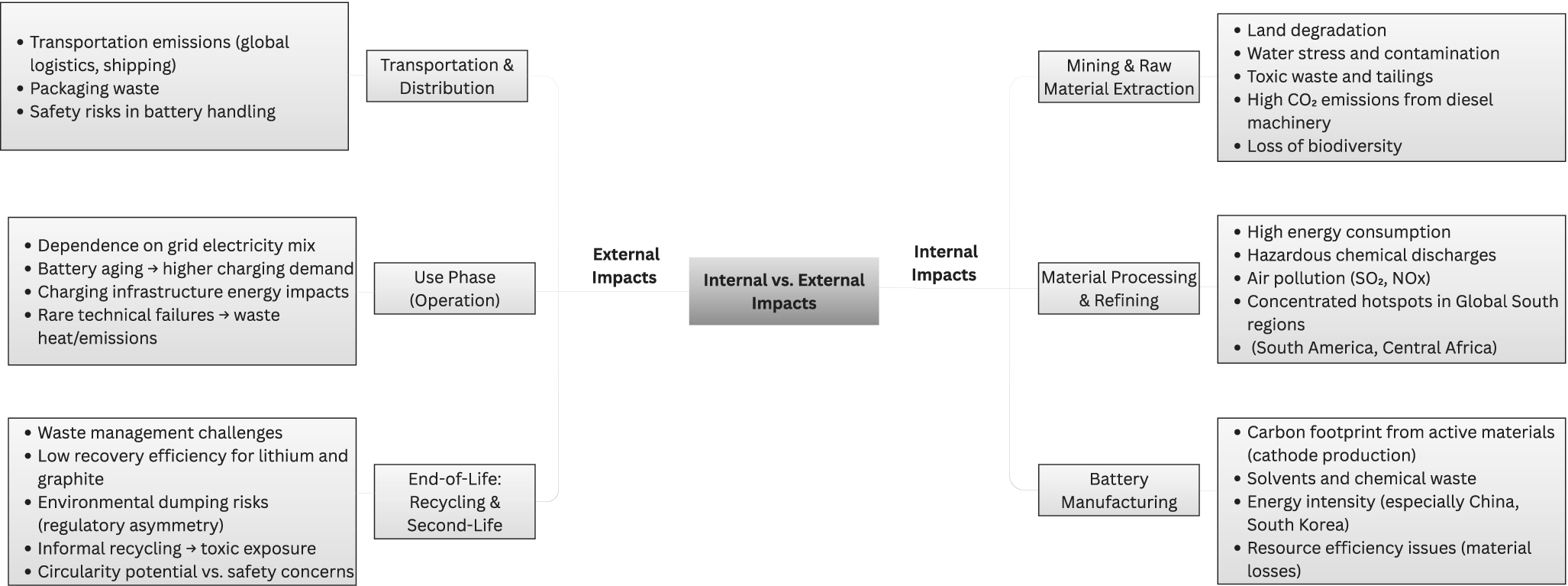

The environmental impacts of each stage of the EV battery SC – including mining, processing, manufacturing, transport, use and EoL – are extensive. In its entirety, the EV battery SC creates environmental impacts through emissions, toxic waste, water consumption and depletion of resources. These impacts are intensified where mining occurs in South America and Central Africa, where energy-intensive manufacturing is concentrated in China and South Korea and where informal EoL management is expanding in Southeast Asia.

Figure 4 indicates the various impacts as either internal (e.g., emissions associated with mining and manufacturing) or external (e.g., emissions associated with transport and the electricity source during use). It draws attention not only to the environmental burdens generated by different aspects of companies’ operational contexts, but also to the external operational context’s ancillary to companies’ direct operations.

Figure 4. Internal and external environmental impacts in the EV battery supply chain.

Both diesel machines and site disruption result in significant CO2 emissions and ecosystem degradation due to mining, particularly in regions with weak regulations and monitoring (e.g., Kaunda, Reference Kaunda2020; Lehtimäki et al., Reference Lehtimäki, Karhu, Kotilainen, Sairinen, Jokilaakso, Lassi and Huttunen-Saarivirta2024). Processing emits even more CO2, because it uses coal-derived electricity, creates hazardous waste with limited oversight and utilizes toxic reagents that emit even more pollutants (e.g., Villa-Mendoza et al., Reference Villa-Mendoza, Santoyo-Castelazo, Otero-Herrera, Vallarta-Serrano and Ramirez-Mendoza2023).

Manufacturing stages, with emphasis on electrode drying, can have high energy use, and their carbon impacts are not helping if the grid runs on fossil fuels (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Huang and Lin2022). Transport emissions add an additional external load, and global transport emissions may be disproportionately driven by moving goods intercontinentally (Busch et al., Reference Busch, Pares, Chandra, Kendall and Tal2024).

The carbon emissions of battery usage depend on the grid mix. Clean grids have little impact, but grids operating on fossil fuels can completely offset any carbon reduction benefits of EV uptake, especially with respect to battery degradation rates requiring additional resource mining (Peñaherrera et al., Reference Peñaherrera, Davila, Pehlken and Koch2022).

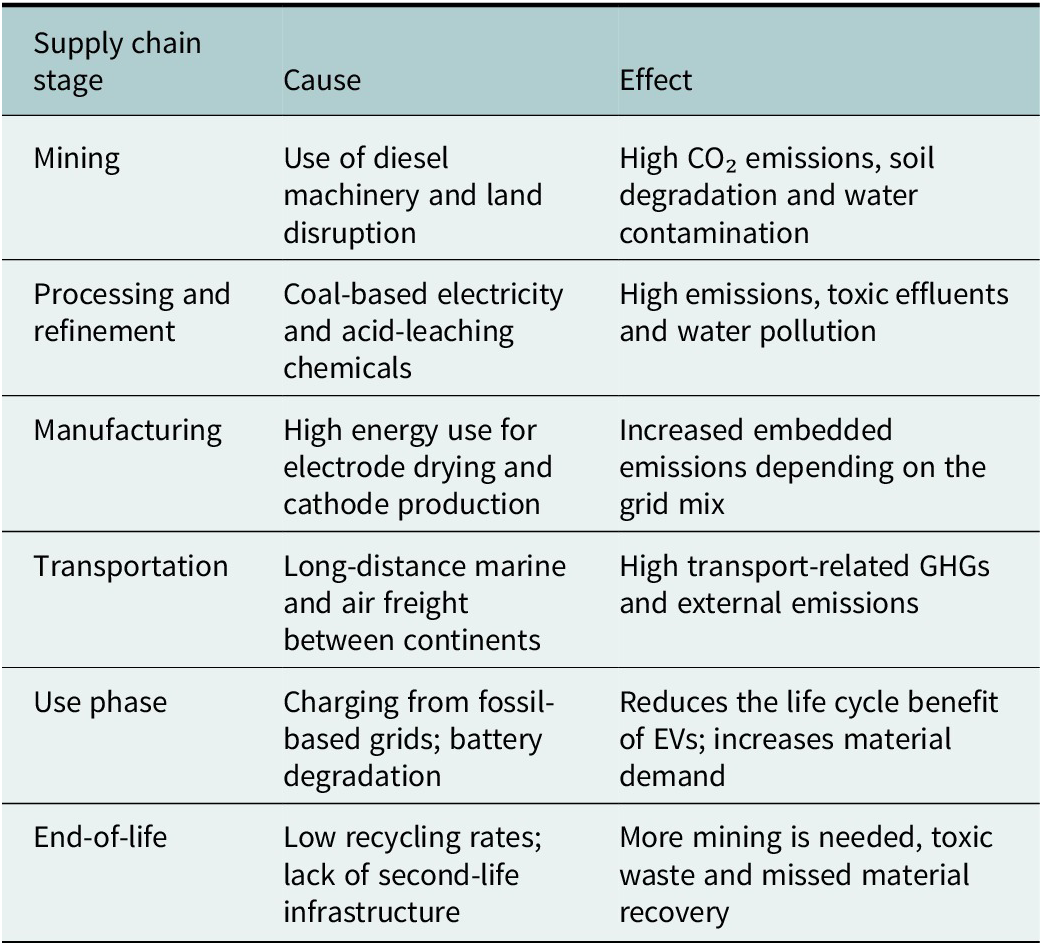

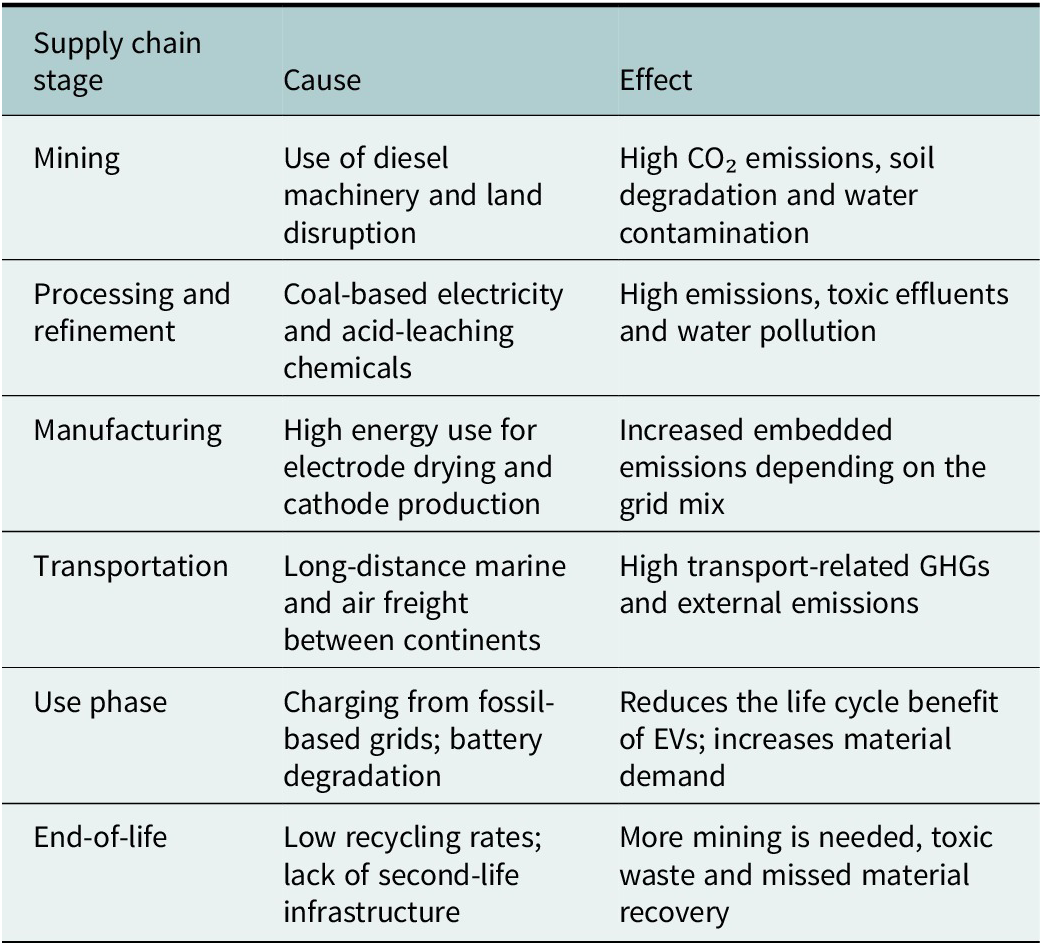

Recycling options of batteries at EoL are limited, particularly in the Global South, leading to additional waste and lost material recovery opportunities. Options for second-hand/life uses have been explored to mitigate the incidence of waste increase, but barriers of technology and regulatory frameworks remain (Islam et al., Reference Islam, Ali, Qadir, Islam and Shahid2024; Kishita et al., Reference Kishita, Boks, Proff, Uhlig, Ahmed, Pantelatos, Mennenga, Blömeke, Scheller, Amasawa and Grimmel2024). Table 1 summarizes key causes and resulting environmental effects across each stage of the EV battery SC. It highlights how specific activities contribute to broader sustainability impacts.

Table 1. Cause-and-effect analysis of environmental impacts on the EV battery SC

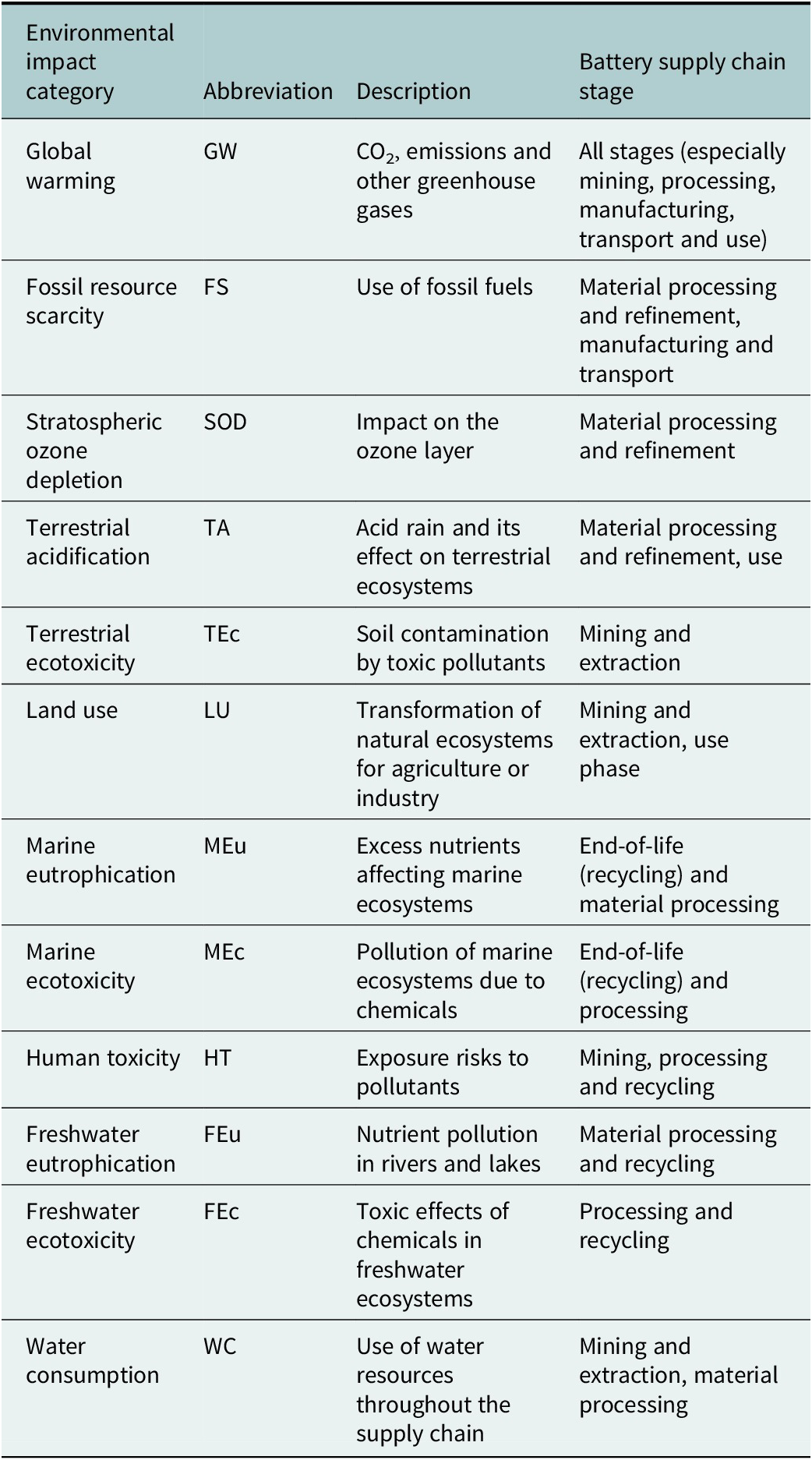

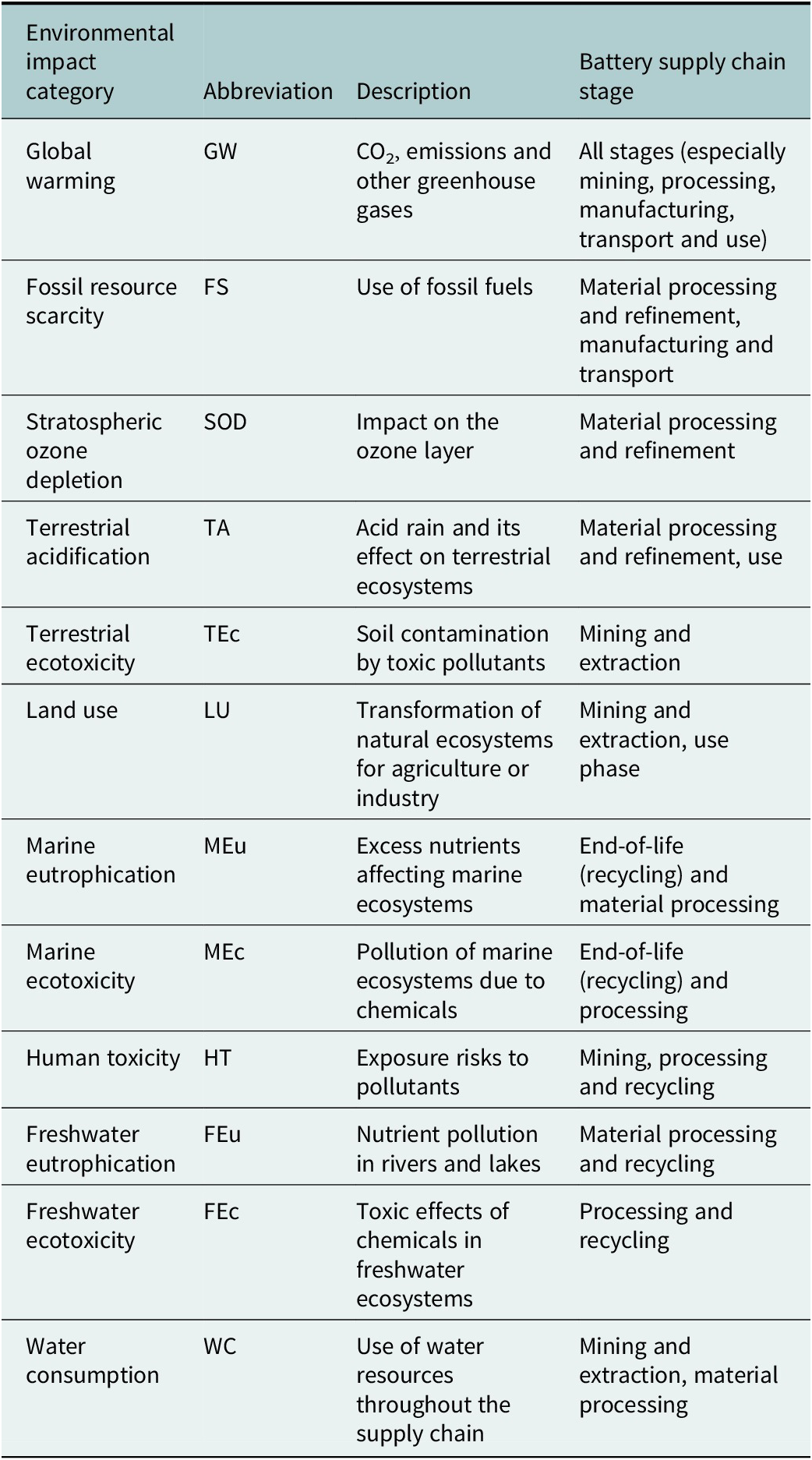

Table 2 institutionalizes some of the environmental categories that mainly encompass the individual stages (Deng et al., Reference Deng, Bae, Denlinger and Miller2020; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Liu, Qian and Bao2020a; Marcos et al., Reference Marcos, Scheller, Godina, Spengler and Carvalho2021; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Zhang and Long2021; Xia and Li, Reference Xia and Li2022; Bruni et al., Reference Bruni, Capocasale, Costantino, Musso and Perboli2023).

Table 2. Environmental impact category

Mining and extraction

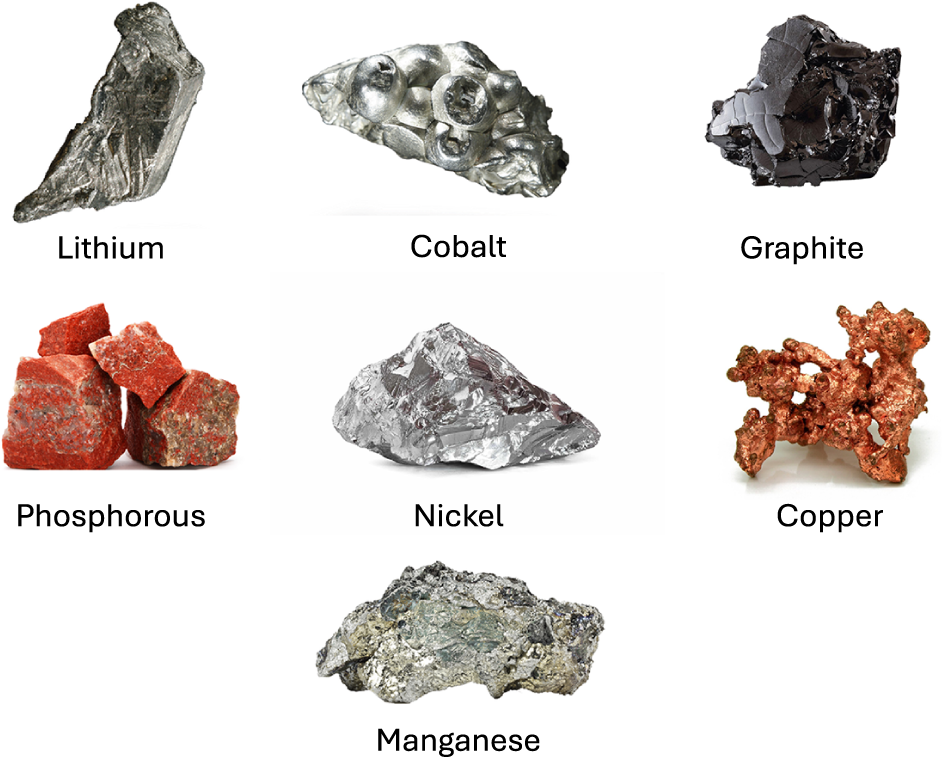

Activities to source critical raw materials, including lithium, cobalt, nickel, graphite, copper, manganese and phosphorus, result in considerable environmental impacts (Figure 5). Mining tends to lead to significant carbon emissions through the use of diesel-powered machinery, excessive water extraction to separate minerals and suppress dust and damage to soil and landscapes (Lehtimäki et al., Reference Lehtimäki, Karhu, Kotilainen, Sairinen, Jokilaakso, Lassi and Huttunen-Saarivirta2024). For example, in South America, Africa and Southeast Asia (Indonesia and the Philippines), lithium brine extraction and hard rock mining can lead to water shortages, degradation of local aquifers and displacement of communities (Kaunda, Reference Kaunda2020). Our concerns about the ethical sourcing of critical raw materials are heightened in countries where governance is weak, and where comprehensive agricultural or environmental standards may not be applied (Peñaherrera et al., Reference Peñaherrera, Davila, Pehlken and Koch2022).

Figure 5. Raw mining materials.

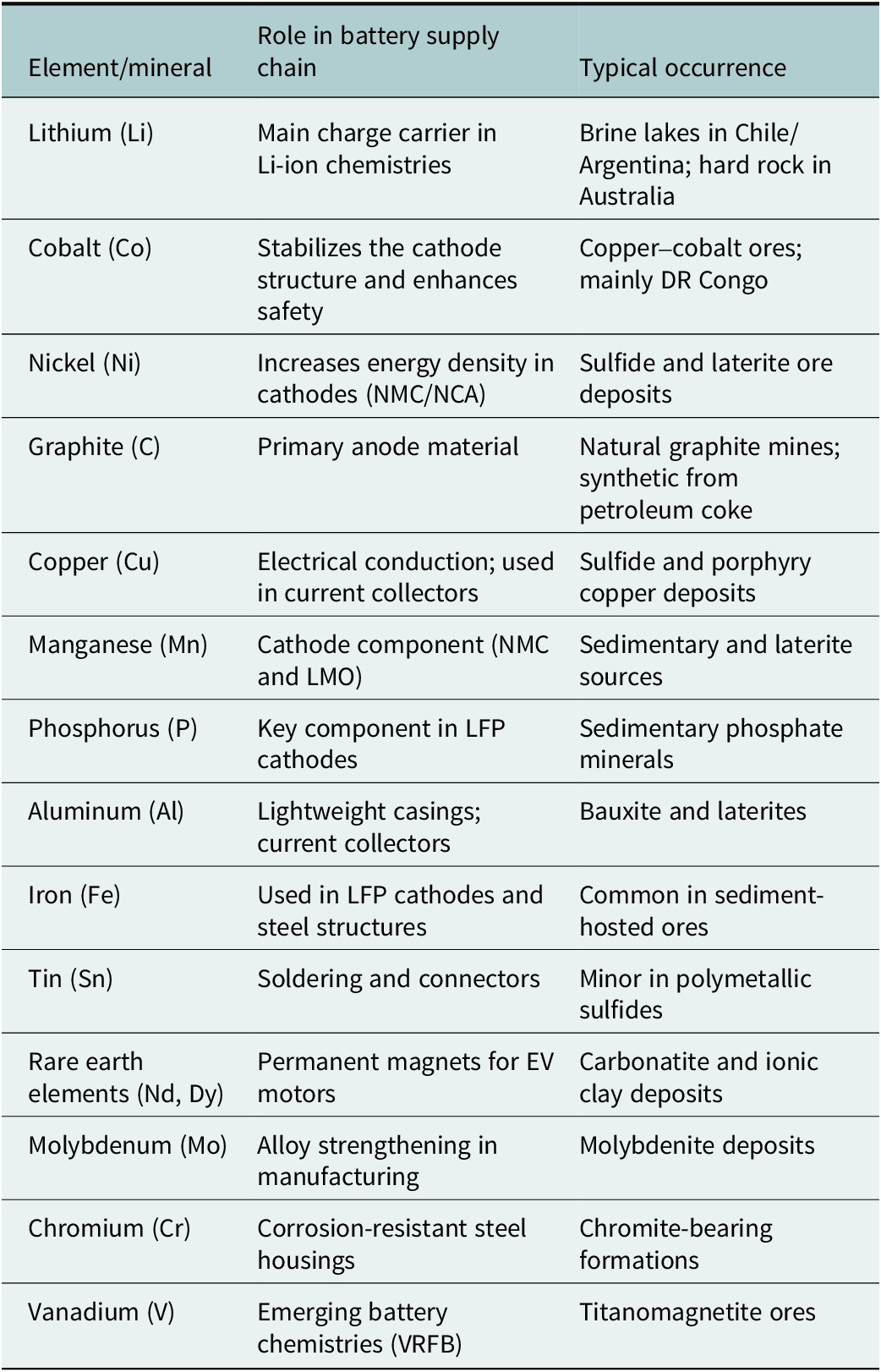

The main raw materials mined for EV battery production are lithium, cobalt, nickel, manganese, copper, graphite and phosphorus shown in Figure 5. These materials are generally the foundation for most current battery chemistries, specifically LIB chemistries, such as nickel-manganese-cobalt (NMC), nickel-cobalt-aluminum (NCA) and lithium-iron-phosphate (LFP). Each of these materials is associated with specific environmental issues – such as carbon dioxide emissions from the machinery used to extract them, high water usage in lithium brine extraction and toxic tailings produced from mining nickel and cobalt.

In addition to the critical materials mentioned above, there are many trace and co-mined materials that are present during the extraction and refining component of the battery SC. These secondary or companion materials are usually not present in high enough concentrations to warrant recovery and recycling. However, by being extracted and not recycled, they cause significant environmental harm, degradation, waste and inefficient use of resources.

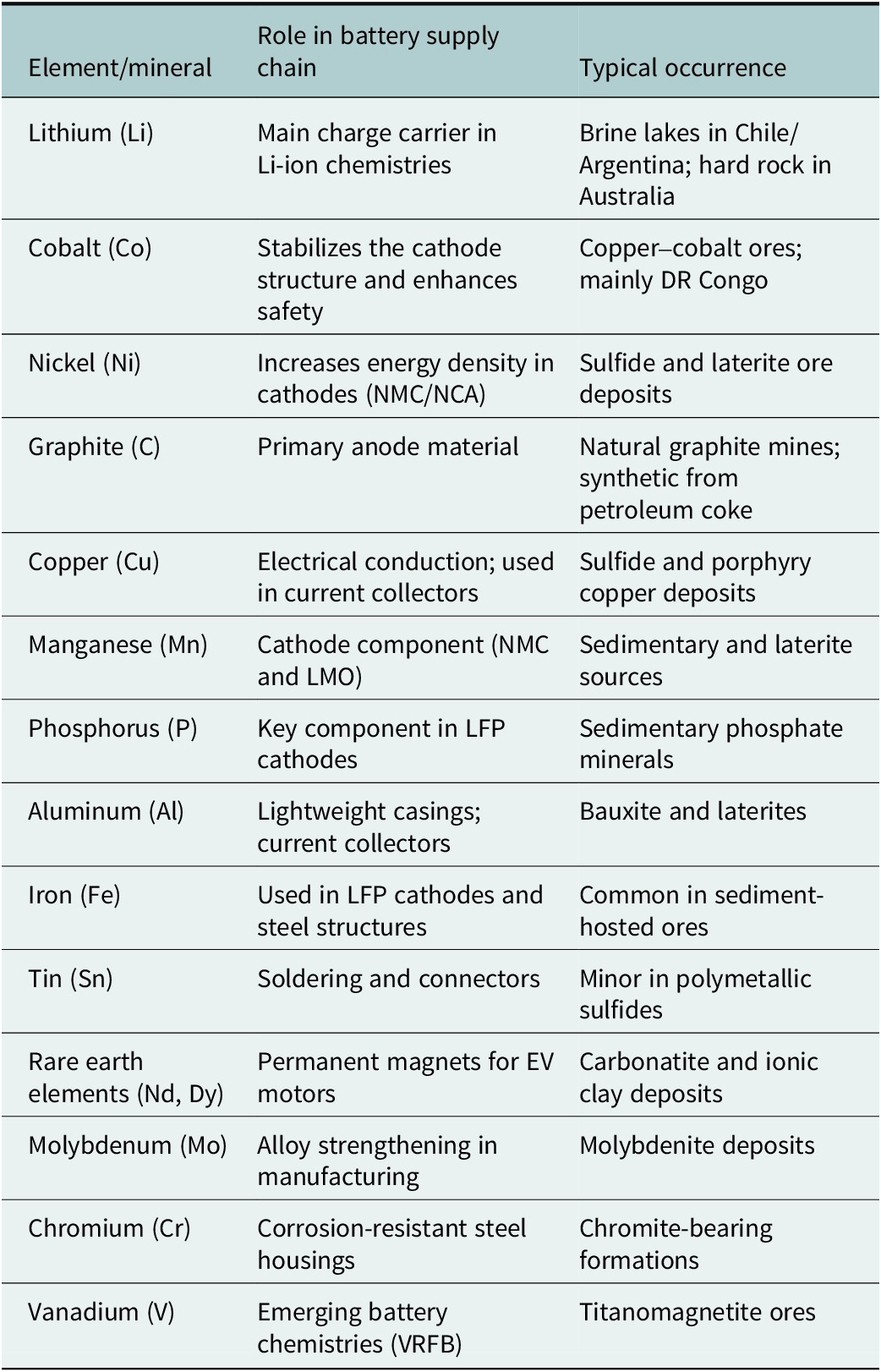

A more extensive list of these additional materials is presented in Table 3 – for example, aluminum, tin, vanadium, rare earth elements (such as neodymium and dysprosium), iron and molybdenum, which are often present in either battery-related ores or alloys used to manufacture batteries.

Table 3. Elements involved in EV battery raw material extraction

Material processing and refinement

The processing and refining phase can be a highly energy-demanding process and, thus, contributes a large proportion of life cycle emissions associated with LIBs. Refinement processes typically involve very high temperatures and chemical treatments (often using fossil fuels), which carry large carbon footprints (Aichberger and Jungmeier, Reference Aichberger and Jungmeier2020). For example, sulfuric acid, hydrochloric acid and solvents are commonly used for refining lithium and cobalt pollution, which produces hazardous effluent flows and solid wastes that are difficult to manage (Villa-Mendoza et al., Reference Villa-Mendoza, Santoyo-Castelazo, Otero-Herrera, Vallarta-Serrano and Ramirez-Mendoza2023). Lax regulations surrounding toxic waste release in countries such as China and subsequent locations that refine materials can exacerbate local emissions (Das et al., Reference Das, Kleiman, Rehman, Verma and Young2024).

Battery manufacturing

Battery cell and module production is an environmental hotspot in and of itself. Electrode drying and coating processes are high-energy users, especially for facilities connected to coal-based grids. For example, the production of cathodes alone can comprise as much as 40% of the energy used in battery production (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Huang and Lin2022). In addition to being generally more energy intensive, battery chemistry affects environmental performance – specifically, LFP provides less energy density but has lower toxicity and supply limitations than NMC variations (Barman et al., Reference Barman, Dutta and Azzopardi2023). The continuing acceptance of LFP in Chinese markets is an indicator of a transition toward safer and more sustainable chemistries.

Transportation and distribution

Due to the globalized nature of the battery SC, components often travel long distances, thereby accumulating significant transportation-based carbon emissions. For example, marine and air freight for ores, refined materials and battery packs emit significant tons of CO2, with intercontinental trade routes emitting even more (Busch et al., Reference Busch, Pares, Chandra, Kendall and Tal2024). Additionally, if there were temperature-controlled shipping for those battery components, there would be more energy usage. SC is long and fragmented among various parts of the world (e.g., mining in Africa, processing in China and assembly in Europe or North America), and the longer logistics add emissions (Rajaeifar et al., Reference Rajaeifar, Ghadimi, Raugei, Wu and Heidrich2022).

Use phase

While EVs produce no tailpipe emissions while operating, the clear environmental advantages over a gasoline or diesel engine come with a caveat: the magnitude of these advantages is defined by the carbon intensity of the electricity used to charge the vehicle. Between fossil-heavy grids, like parts of Asia or Eastern Europe, the life cycle emissions of EVs may be considerable (Llamas-Orozco et al., Reference Llamas-Orozco, Meng, Walker, Abdul-Manan, MacLean, Posen and McKechnie2023). Moreover, battery degradation impacts both performance and environmental efficiency. Short-lived batteries create further throughput for materials, increasing total embedded emissions per kilometer driven (Peñaherrera et al., Reference Peñaherrera, Davila, Pehlken and Koch2022).

EoL: Recycling and second life

EoL strategies provide a key opportunity to close material loops and reduce upstream impacts. Currently, there are mechanical, pyrometallurgical and hydrometallurgical processes for LIB recycling, although the efficiency and environmental impact of these methods vary significantly. Hydrometallurgy is a relatively efficient process for recovering materials; however, it entails a more onerous level of chemical management (Islam et al., Reference Islam, Ali, Qadir, Islam and Shahid2024). Alternatively, second-life application of batteries – directly repurposing EV batteries for stationary storage – has the potential to substantially prolong the useful life of materials and reduce overall demand for virgin materials (Simons et al., Reference Simons, Singh, Hunt and Ermilio2022). However, unfavorable factors, such as inconsistent battery health, lack of standardization and lack of clarity in regulatory frameworks, continue to be significant impediments to its adoption (Kishita et al., Reference Kishita, Boks, Proff, Uhlig, Ahmed, Pantelatos, Mennenga, Blömeke, Scheller, Amasawa and Grimmel2024). While the global EV industry is increasingly scaling, addressing these consequences for the environment at all stages of the SC is a necessary step toward true sustainability in electrification. The next section examines comparative findings across methodologies and geographies to clarify additional areas for improvement.

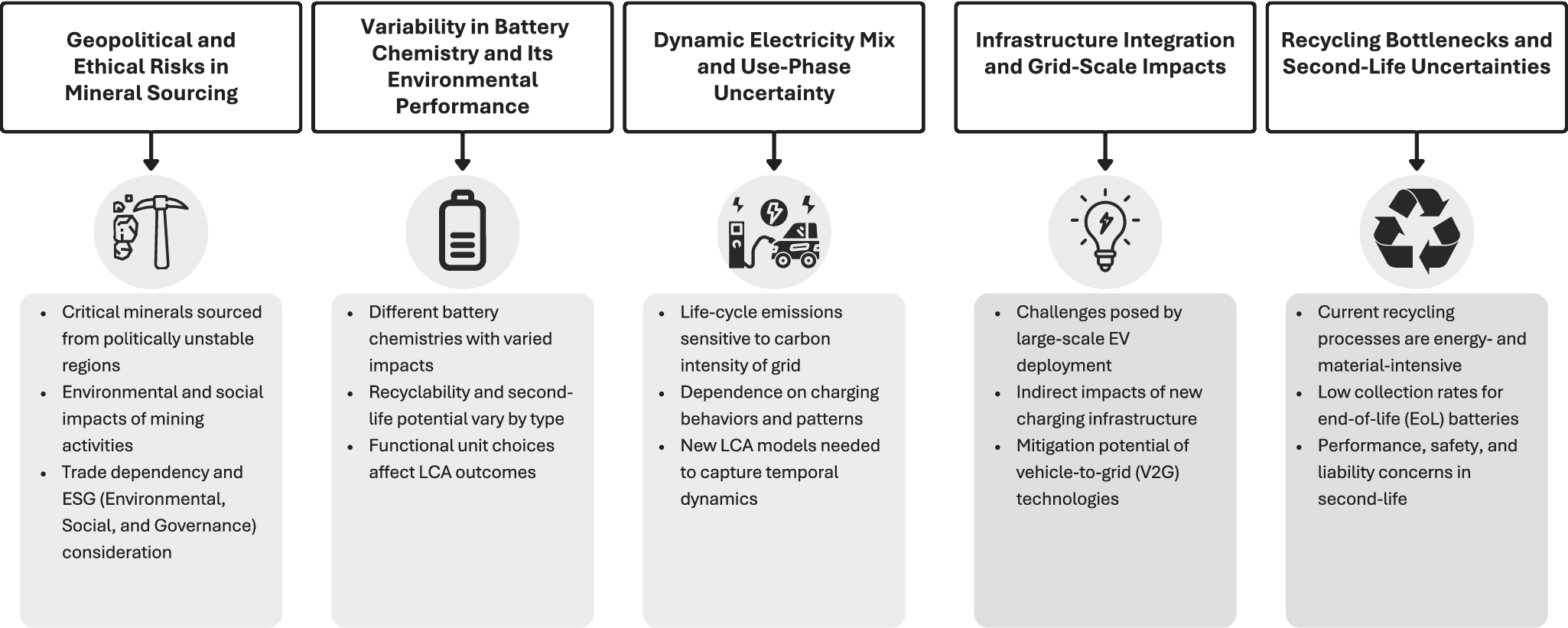

Systemic challenges in the EV battery SC: Insights from recent LCA literature

As EV uptake increases, systemic challenges in the battery SCs have become more apparent. LCA literature reveals that the sustainability of EVs is connected to use-phase emissions, sourcing of materials, the conditions under which products are produced, how things can be adopted and adapted to support infrastructure and services and eventual disposal. This section pulls together key points from recent LCA studies to draw attention to five systemic barriers that inhibit the sustainable development of EV battery SCs. Figure 6 illustrates the key systemic barriers identified across recent LCA studies, highlighting five interconnected dimensions that influence the environmental performance of EV battery SCs. These points expose some of the systemic complexities that are often masked in simplified environmental comparisons of EVs to internal combustion engine vehicles (ICEVs).

Figure 6. Life cycle assessment insights into key barriers of EV battery supply chains.

Geopolitical and ethical risks in mineral sourcing

One of the most frequently referenced issues in the EV battery life cycle is the source of impactful minerals often referred to as critical minerals (lithium, cobalt and nickel), since they are extracted in a manner that brings up environmental, social and governance (ESG) problems. For example, cobalt mining in the Democratic Republic of the Congo is responsible for over 70% of global supply that appears regularly to coincide with artisanal mining and human rights abuses (Egbue and Long, Reference Egbue and Long2012; Scott and Ireland, Reference Scott and Ireland2020). The Lithium Triangle (Chile, Argentina and Bolivia) of lithium extraction is coupled with water extraction, resulting in adverse effects on the ecosystem in arid contexts (Temporelli et al., Reference Temporelli, Carvalho and Girardi2020; Peñaherrera et al., Reference Peñaherrera, Davila, Pehlken and Koch2022).

From a life cycle analysis perspective, the characteristics of mineral sourcing stages of the life cycle analysis needed to identify the sources of raw materials suggest they lead to disproportionate, additive, environmental burdens, especially in terms of water use and overall energy intensity (Zackrisson et al., Reference Zackrisson, Avellán and Orlenius2010; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Hu, Yu, Huang and Wang2021). These sourcing-related issues are exacerbated by trade dependencies as well as geopolitical tensions with countries exhibiting nonstable governance (Manzetti and Mariasiu, Reference Manzetti and Mariasiu2015). As a result, upstream environmental assessments should have integrated ESG indicators to better denote the systemic fragility of mineral SCs (Nordelöf et al., Reference Nordelöf, Messagie, Tillman, Ljunggren Söderman and Van Mierlo2014).

Variability in battery chemistry and its environmental performance

Battery technologies have dramatically differing environmental characteristics. Selecting battery chemistry can produce different LCAs, which compare LFP, NMC and NCA battery chemistries. It is reasonable to expect that they will vary as a result of differences between whatever is mined and subsequent emissions, toxicity potential and resource depletion (Matheys et al., Reference Matheys, Timmermans, Van Mierlo, Meyer and Van den Bossche2009; Majeau-Bettez et al., Reference Majeau-Bettez, Hawkins and Strømman2011). NMC batteries apparently have the highest energy density among the three, but extractive and related processes often produce the highest environmental impacts.

The environmental performance associated with battery chemistries has consequences for recyclability and second life in batteries. Cox et al. (Reference Cox, Mutel, Bauer, Mendoza Beltran and Van Vuuren2018) discuss the evolution of technology and how that creates uncertainty in long-term environmental estimates. As considered by Wu et al. (Reference Wu, Hu, Yu, Huang and Wang2021) difference in selection of functional unit (e.g., per-km driven vs. per battery pack) will have a great impact on LCA, indicating a need to standardize and define batteries in comparative analyses. In addition, LFP batteries may have less toxicity than NMC and NCA batteries and, therefore, some measure of greater safety in terms of the environmental health profile. Although as energy densities decrease, the footprint per kWh stored could increase due to more material demand.

Dynamic electricity mix and use-phase uncertainty

The environmental impacts of EVs are highly sensitive to the carbon intensity of the electricity grid, which varies widely in different regions. In countries like India, where coal is the most dominant form of energy, EVs can equal or even exceed the life cycle emission rates of ICEVs (Bhosale and Mastud, Reference Bhosale and Mastud2023). On the other hand, in high renewable penetration contexts, like Norway or Canada, the life cycle Green House Gas (GHG) reductions of EVs are considerable (Rangaraju et al., Reference Rangaraju, De Vroey, Messagie, Mertens and Van Mierlo2015). Without a doubt, the benefits presented here depend strongly on charging patterns, a time-of-use component and demand side management programs (Putrus et al., Reference Putrus, Suwanapingkarl, Johnston, Bentley and Narayana2009; Koj et al., Reference Koj, Wulf, Linssen, Schreiber and Zapp2018). LCA models that do not account for these temporal components will likely result in a poor representation of emissions. Dynamic LCA models need to be incorporated to properly account for grid variability with respect to how and when charging will take place (Bekel and Pauliuk, Reference Bekel and Pauliuk2019).

Infrastructure integration and grid-scale impacts

Widespread deployment of EV vehicles presents significant challenges for existing power infrastructure, including load management, transformer overload situations and voltage stability (Garcia-Valle and Lopes, Reference Garcia-Valle and Lopes2012). Vehicle-to-grid technologies may offer some mitigation, but they are not widely deployed. LCA studies often fail to capture the indirect environmental impacts of infrastructure adaptation requirements to support large fleets of EVs (Putrus et al., Reference Putrus, Suwanapingkarl, Johnston, Bentley and Narayana2009; Hawkins et al., Reference Hawkins, Gausen and Strømman2012).

The transition from ICEVs to EVs also means many new charging stations will need to be built, which have significant embodied carbon requirements. Infrastructure emissions (when included) can eliminate some of the climate benefits expected with the uptake of EVs, particularly where there are high initial emissions per kWh (Ahmadi et al., Reference Ahmadi, Yip, Fowler, Young and Fraser2014).

Recycling bottlenecks and second-life uncertainties

While battery recycling is part of circular economy approaches, the current recycling facilities available are energy-inefficient, and the yield is limited. For instance, pyrometallurgy can recover nickel and cobalt but regularly loses lithium and graphite (Golroudbary et al., Reference Golroudbary, Calisaya-Azpilcueta and Kraslawski2019. The collection rates for EoL batteries are still low due to logistics and regulations (Ahmadi et al., Reference Ahmadi, Yip, Fowler, Young and Fraser2014). Second-life applications such as stationary storage are promising, but with them come other issues like performance degradation, safety and liability (Manzetti and Mariasiu, Reference Manzetti and Mariasiu2015). It will not be possible to conduct a reasonably accurate LCA from second-life applications without an established method to handle the second-life use case, as variables for performance, safety and liability cannot be established in the mass cases from recycling with EoL batteries. Temporelli et al. (Reference Temporelli, Carvalho and Girardi2020) argues that it is important to evaluate (LCA) circularity pathways, which allows for a more realistic evaluation of long-term environmental impacts.

Informal recycling methods, which are mainly manual and unregulated, can emit up to 10 times the per ton of loaded pollutants than formal recycling facilities, resulting in disproportionately high environmental and health burdens in disadvantaged areas (Soares et al., Reference Soares, Reis, Vieira, Hernandez-Callejo and Boloy2023).

In addition, financial limits are one of the major barriers to scaling sustainable recycling routes in the EV battery SCs. Hydrometallurgical methods and pyrometallurgical processes are recycling technologies that necessitate high-cost processing equipment, energy demand and stringent hazardous waste management procedures (Cox et al., Reference Cox, Mutel, Bauer, Mendoza Beltran and Van Vuuren2018). In addition to those existing economic pressures, secondary material markets are frequently unstable – where the prices of recovered metals (like lithium, cobalt and nickel) are critical for profitability and can significantly drive investment risk (Bekel and Pauliuk, Reference Bekel and Pauliuk2019). Without reliable revenue streams and robust policy signals, the private sector will not expand recovery infrastructure, which slows progress to a fully circular battery system despite increasing prioritization of material security and responsible management for materials at EoL (Temporelli et al., Reference Temporelli, Carvalho and Girardi2020; Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Li and Zhang2023).

Critical evaluation of data reliability and comparability across SC stages

Even with increasing attention being given to the EV battery SC from academic and industrial perspectives, the availability and comparability of environmental data are drastically different depending on the life cycle stage. The mining and extraction stage is still considered one of the most uncertain, data-rich and disputed life cycle stages, particularly in low- and middle-income nations lacking formal operations and regulatory frameworks, as well as limited capacity to monitor. There are case studies referencing the Lithium Triangle in Chile, Argentina and Bolivia, or studies examining diversifying cobalt extraction in Central Africa, primarily estimating evidence or using old reports, none of which detail specific methodologies to quantify impact.

If we move on to the refining and manufacturing stages, researchers can draw on relatively richer datasets, particularly in places like China, South Korea and the EU, where the industrial processes are much better documented. However, inconsistency with the functional units used – per cell, per kWh or per vehicle – limits comparability. Furthermore, there are uncertainties and variability between studies around assumptions on grid mix or percent of electricity loaded, what is manufacturing efficiency and how emissions were allocated between manufacturing SC components.

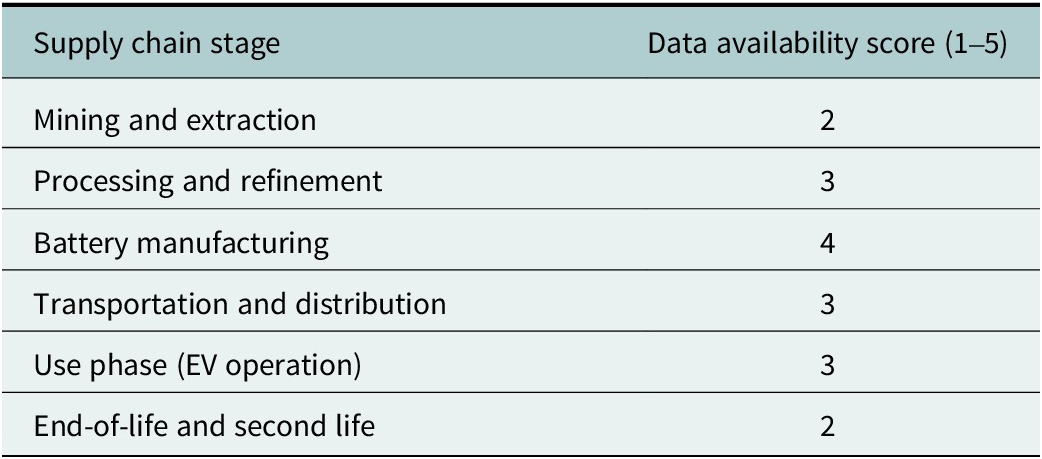

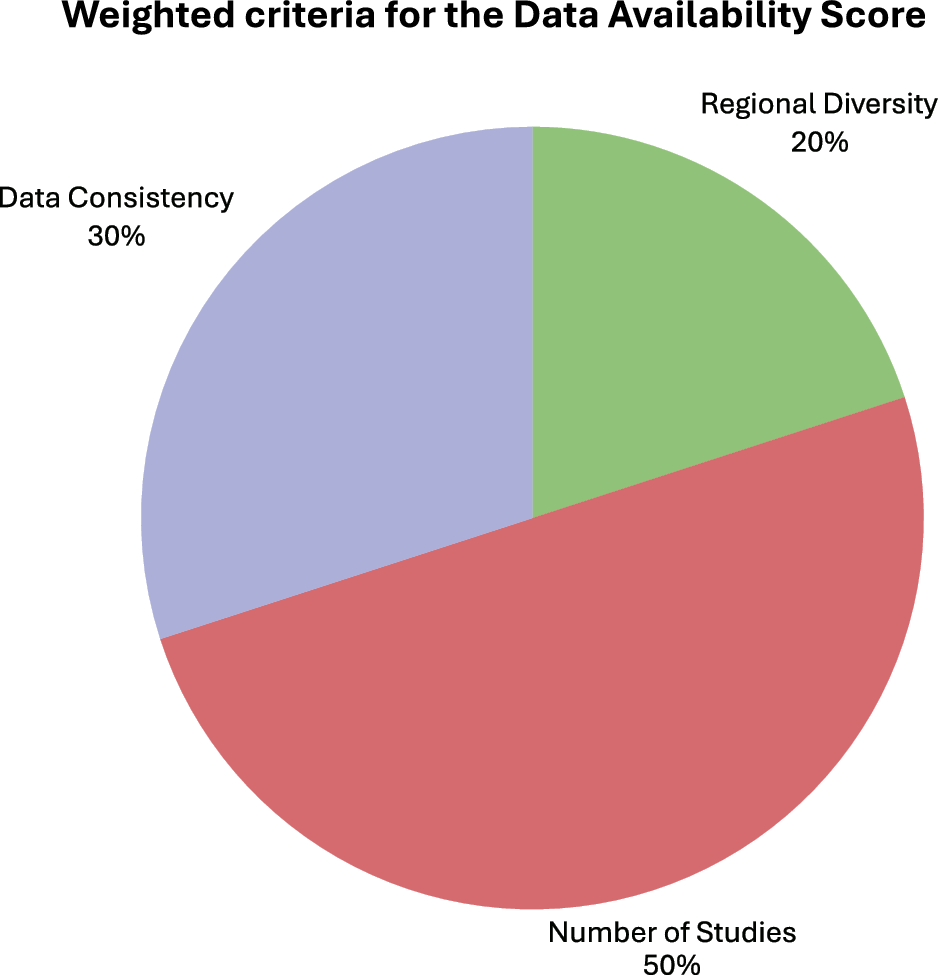

To evaluate the strength and reliability of the environmental evidence at each SC stage, a data availability score (1–5) was developed based on three key data quality dimensions typically used in meta-assessments of LCA studies: Number of studies (NS), data consistency (DC) and regional diversity (RD). Weights of 50%–30%–20% were assigned to these criteria to reflect their relative influence on evidence robustness. NS (50%) received the highest weight as it represents the volume of scientific evidence supporting each stage. DC (30%) assesses alignment in methodological parameters (e.g., functional units, system boundaries and transparency of inventory), which influences comparability. RD (20%) indicates geographical representativeness; although crucial for global SCs, it is reduced due to limited reporting from the Global South.

This weighting framework follows established practices in LCA data-quality assessment consistent with ISO 14040/14044, which recommend declaring criteria, their weighting and aggregation methods to ensure transparency and reproducibility. The stage-level score was calculated using the following weighted average model:

where:

NS = Number of studies available for the stage

DC = Methodological consistency rating

RD = Regional diversity rating

(All three criteria range from 1 = low to 5 = high).

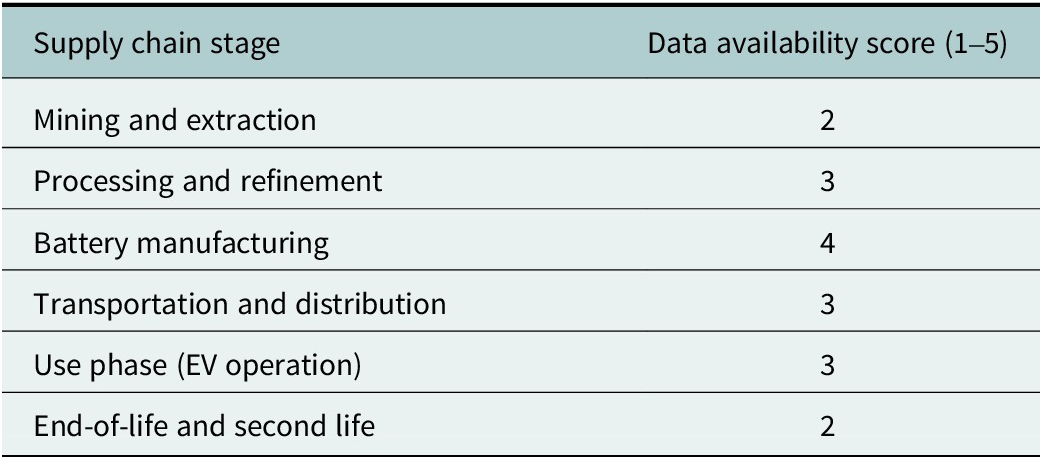

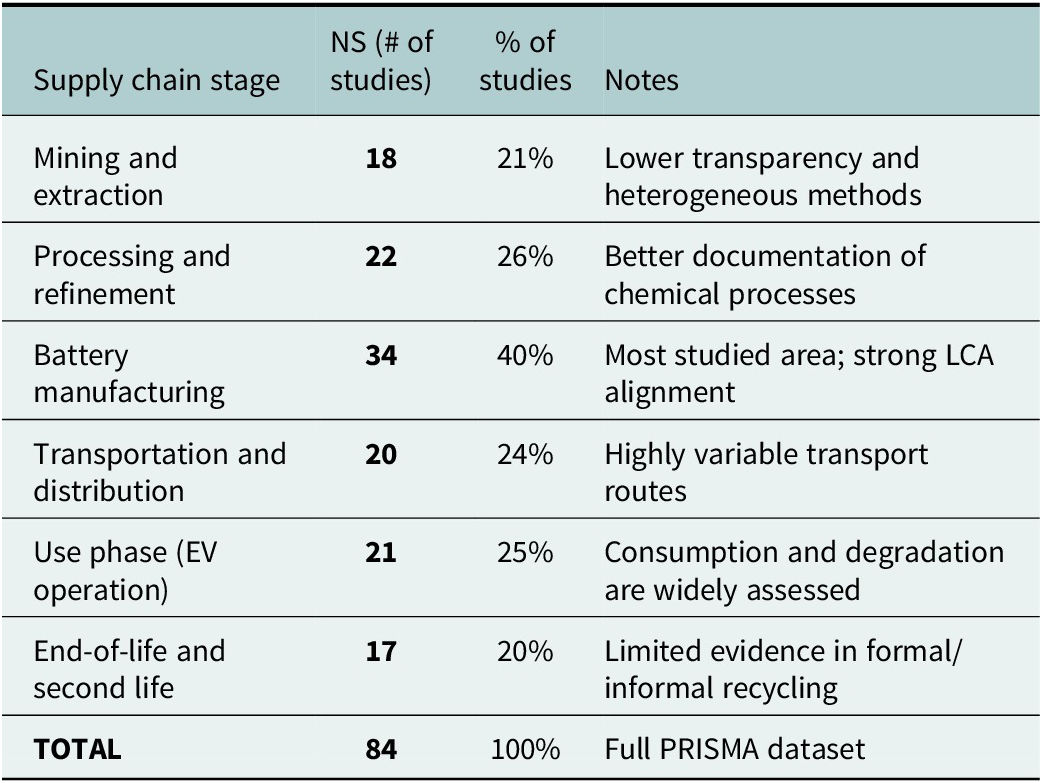

A PRISMA-based (Figure 1) review of 84 peer-reviewed studies was used to extract and categorize evidence according to the 6 SC stages. Table 4 reports the NS values, which sum to the total corpus (84 studies) and form the quantitative basis for the 50% weighting in Equation 1.

Table 4. Number of studies (NS) by EV battery supply chain stage

Methodological consistency (DC) and regional diversity (RD) were assessed using qualitative scoring rubrics based on system boundary alignment, functional unit comparability, inventory transparency and geographic coverage across the literature. The combined weighted results were rounded to the nearest integer to obtain the final data availability score.

Results using the equation:

-

1. Mining and extraction: NS = 2, DC = 2, RD = 2 → score = 2 (few studies; heterogeneous methods; limited geographic coverage)

-

2. Processing and refinement: NS = 3, DC = 3, RD = 2 → score = 3

-

3. Battery manufacturing: NS = 5, DC = 4, RD = 3 → score = 4 (most studied stage with strong methodological alignment)

-

4. Transportation and distribution: NS = 3, DC = 2, RD = 3 → score = 3

-

5. Use phase (EV operation): NS = 3, DC = 3, RD = 3 → score = 3

-

6. End-of-life and second life: NS = 2, DC = 2, RD = 2 → score = 2 (critical gaps in recycling and circular recovery)

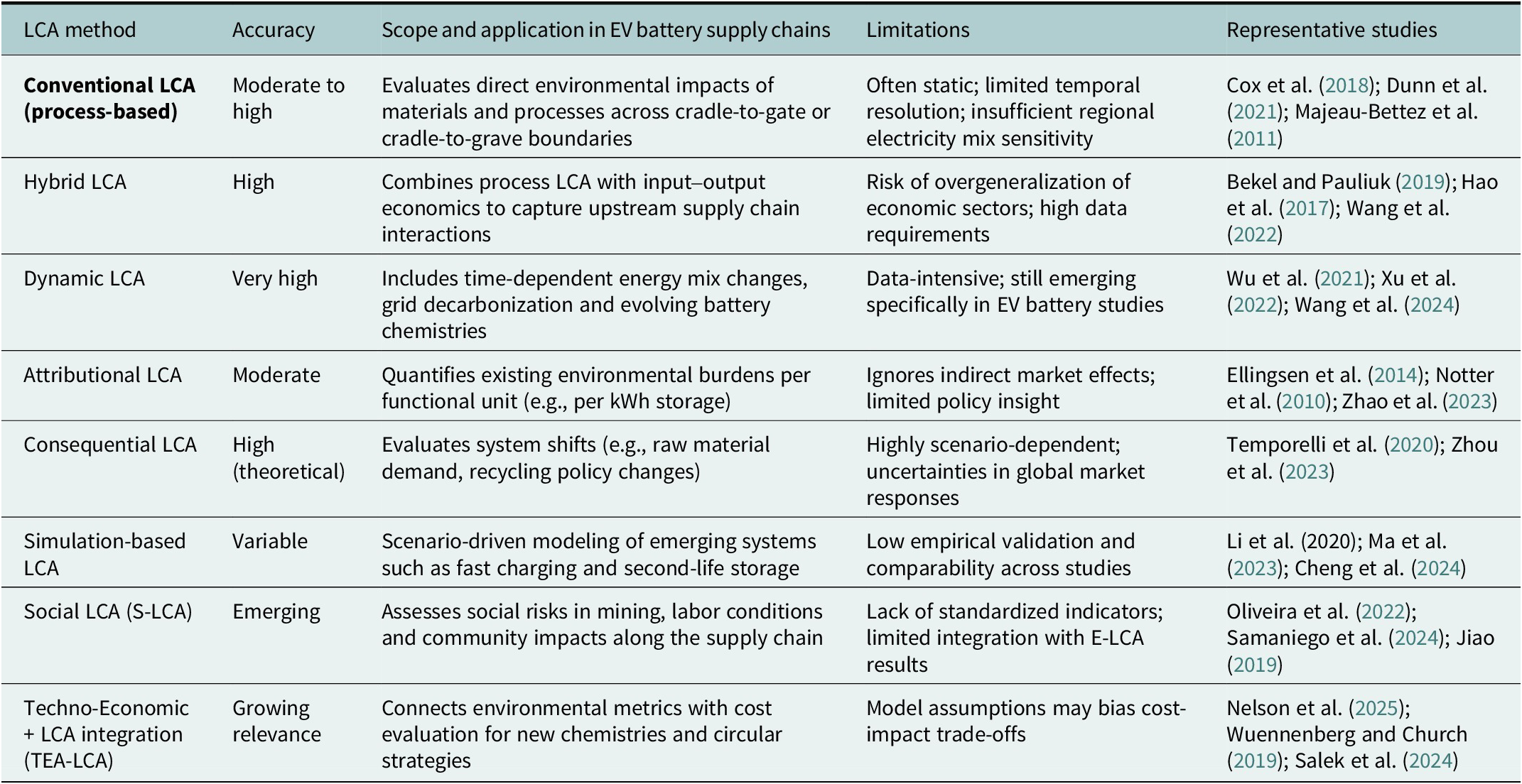

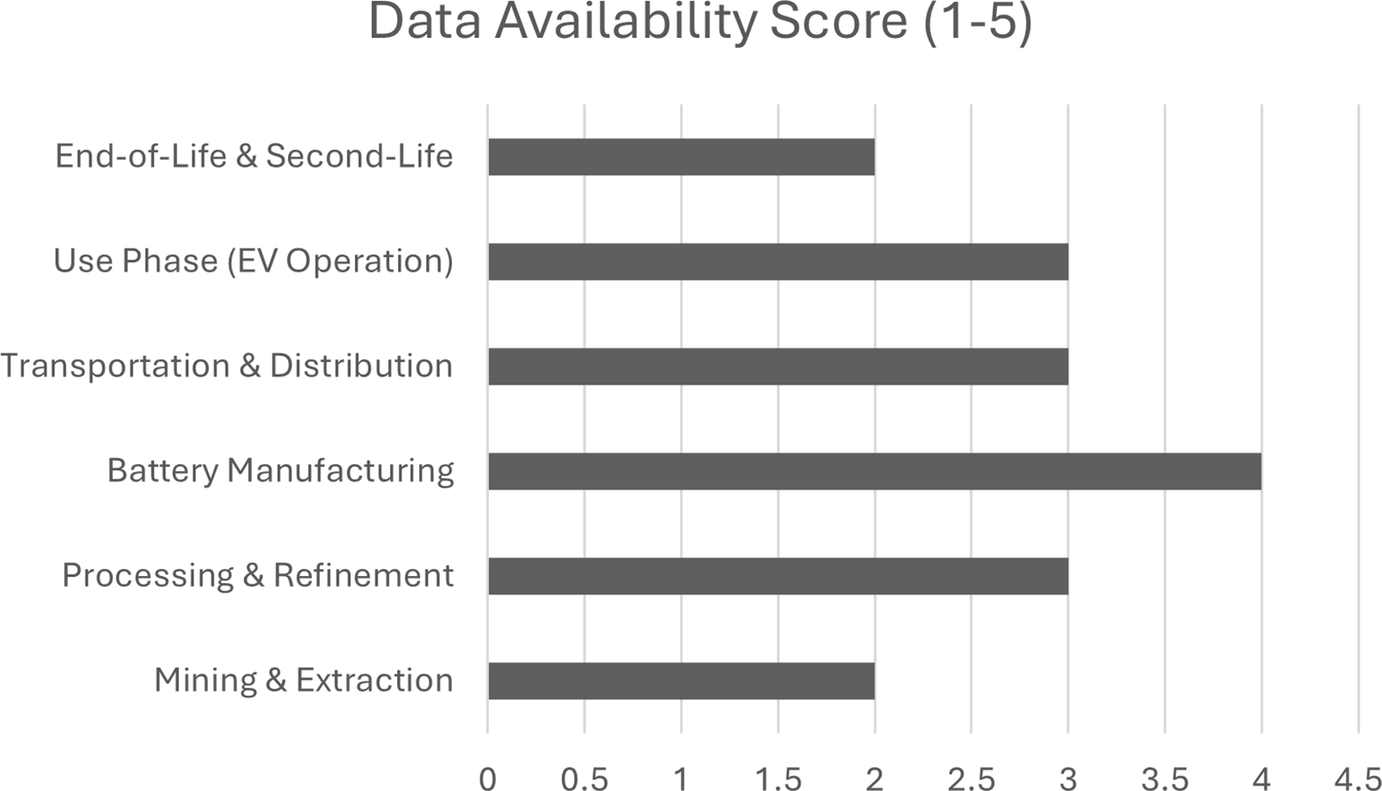

The resulting scores are presented in Table 5, showing that battery manufacturing has the highest data availability, while mining and extraction and EoL/second life show the lowest levels of accessible and comparable data.

Table 5. Data availability score (1–5) across EV battery supply chain stages

The weighting scheme is illustrated in Figure 7, and the resulting stage-wise availability levels are visually represented in Figure 8, which facilitates a direct comparison across the six stages.

Figure 7. Weighted criteria for the data availability score.

Figure 8. Data availability across the EV battery supply chain stages.

The results in Figure 8 highlight a consistent trend: Data constraints are most pronounced at the beginning and end of the SC, particularly in mining practices and recycling pathways. These evidence gaps may limit the accuracy of environmental assessments and pose challenges for advancing circular strategies and responsible SC decision-making.

Comparability across SC stages

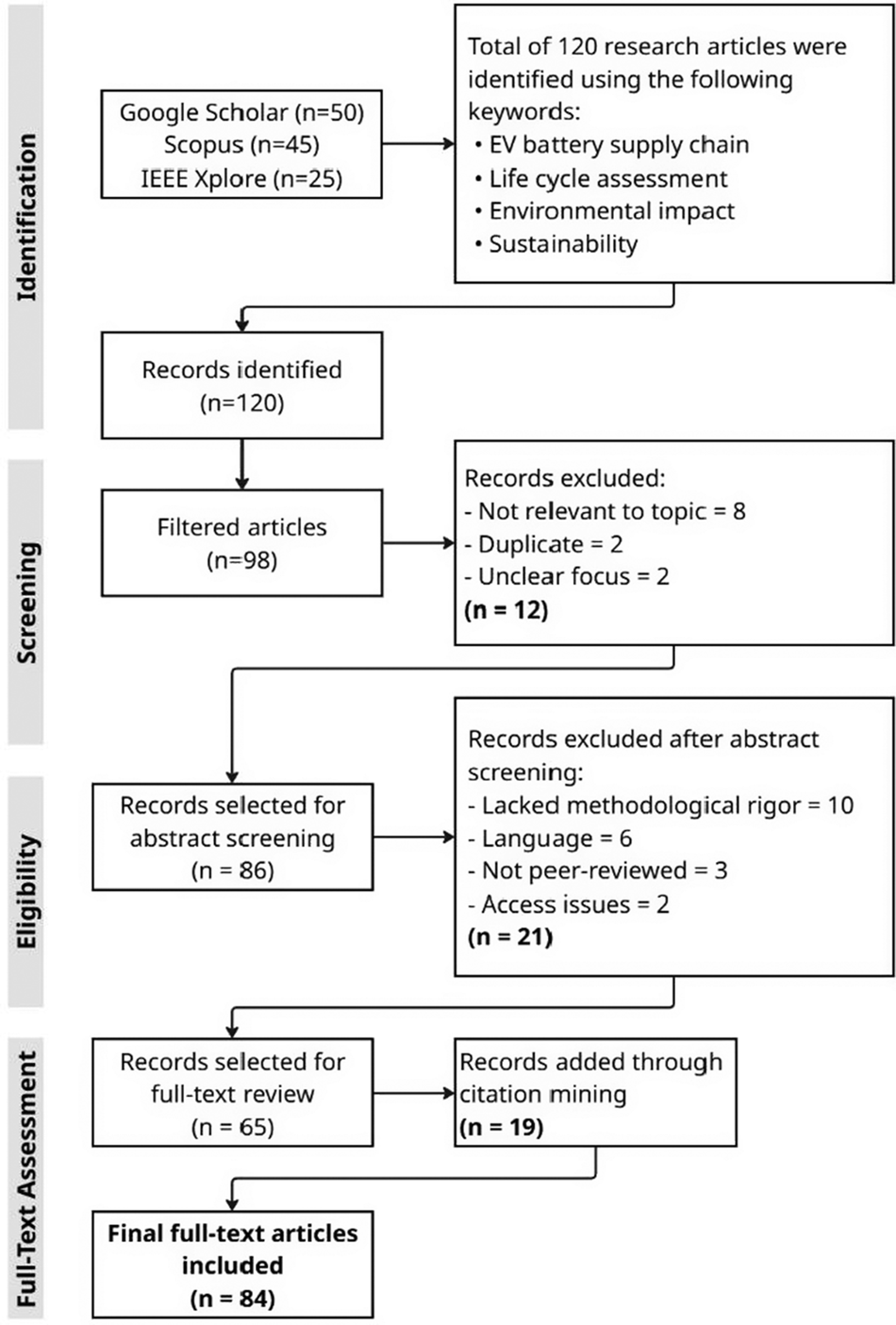

There are significant variations among environmental assessments of EV battery SCs due to differences in frameworks and methodologies. LCA is the predominant methodology, but there may be significant cultural differences in scope and system boundaries, as one researcher might use a cradle-to-gate LCA while another uses the cradle-to-grave approach (Aichberger and Jungmeier, Reference Aichberger and Jungmeier2020). A hybrid approach that combines LCA with input–output analysis or other simulations may arguably have an advantage by identifying the economic and geopolitical variables (Kumar et al., Reference Kumar, Singh, Paul and Sinha2021; Llamas-Orozco et al., Reference Llamas-Orozco, Meng, Walker, Abdul-Manan, MacLean, Posen and McKechnie2023).

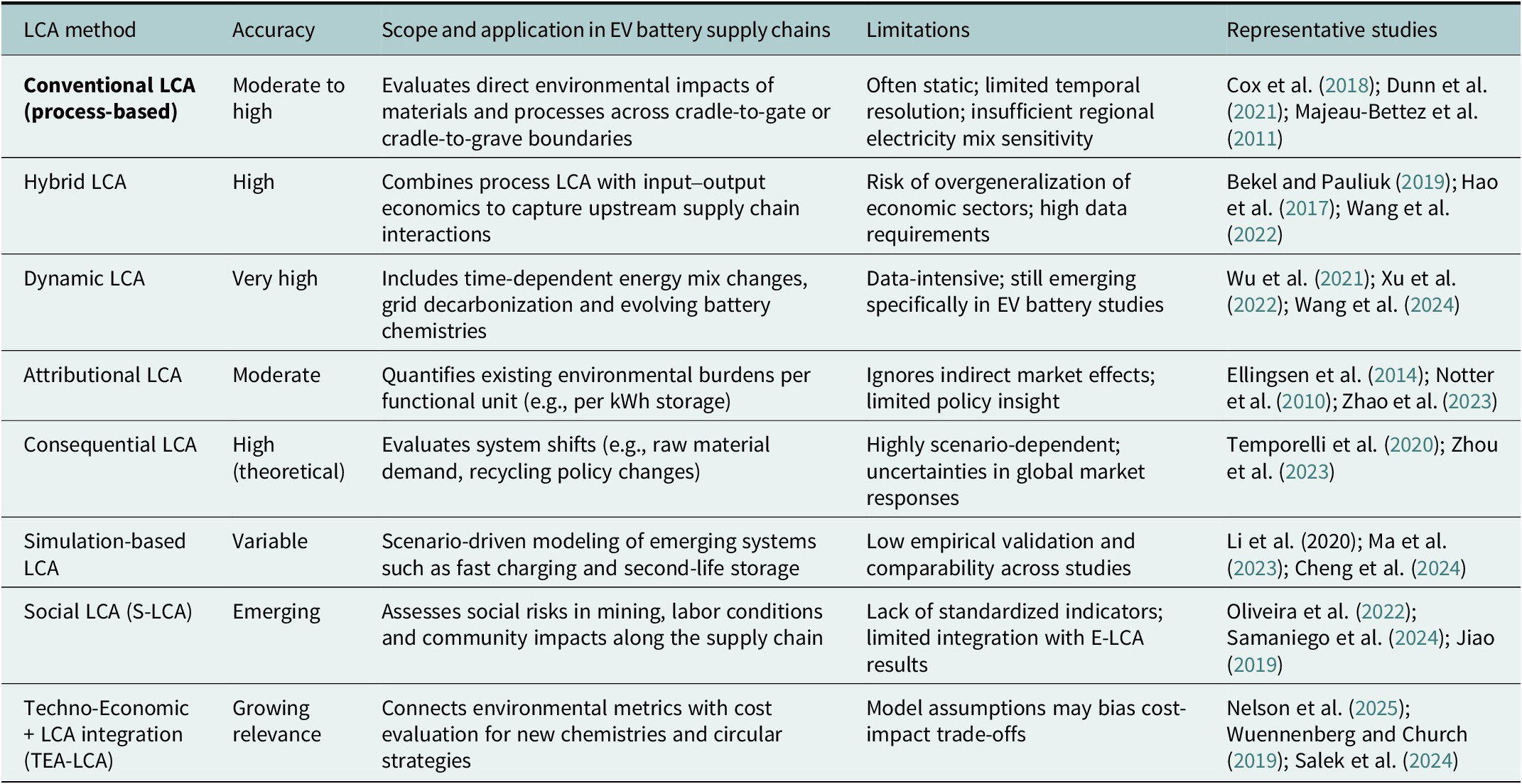

Table 6 contains a structured side-by-side comparison of the most commonly used LCA methods applied to green the environmental assessment of EV battery SCs. Each method is assessed with respect to three key criteria: accuracy, scope and limitations. Accuracy refers to whether the method represents environmental impacts realistically; scope describes how comprehensive the life cycle is in scope and system detail and limitations highlight common limitations, such as data needs, assumptions and reproducibility. This comparative summary illustrates distinctions among methodologies in the literature and aids researchers in selecting LCA methods that meet their sustainability goals across data contexts.

Table 6. Comparative overview of LCA and related methods in EV battery supply chains

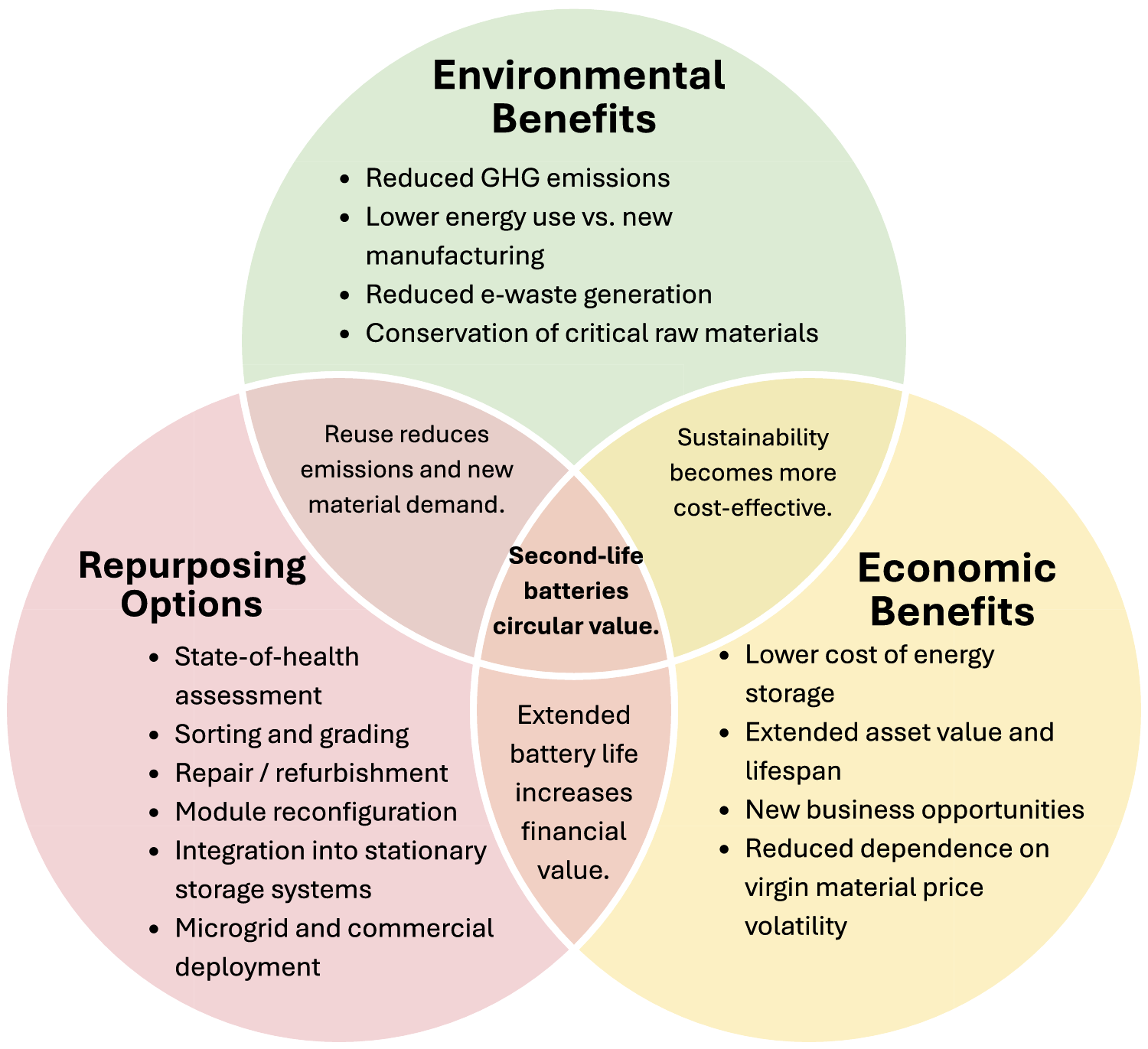

Second-life batteries: Linking repurposing strategies to environmental impact

As illustrated in Figure 9, the Venn diagram conveys the message that particular strategies related to the repurposing of EV batteries can provide a multitude of environmental benefits. Each connection demonstrates how a particular practice has a direct relationship with sustainability or environmental impacts across the life cycle from production to site-specific usage.

Figure 9. Venn diagram of second-life EV battery repurposing and environmental benefits.

Battery health assessment → lengthening battery life

Through the diagnostics and grading of batteries, the state-of-health (SoH) can be assessed to identify whether a battery is fit for use in secondary applications, and this would subsequently extend its functional life and delay disposal/recycling options, as identified by Casals et al. (Reference Casals, García, Aguesse and Iturrondobeitia2017). Identifying the SoH of the battery will also push back the demand for new batteries and limit the amount of batteries that are unnecessarily scrapped while still functioning (Ioakimidis et al., Reference Ioakimidis, Murillo-Marrodán, Bagheri, Thomas and Genikomsakis2019).

Proper grading avoids discarding viable batteries → decrease in toxic waste from premature recycling

Disposal of batteries that are still reusable amounts to unneeded toxic emissions and the loss of potential materials. With grading and selection, batteries that would have otherwise entered a waste stream can be redirected to minimize toxic outputs from recycling them prematurely (Hendrickson et al., Reference Hendrickson, Kavvada, Shah, Sathre and Scown2015; Gu et al., Reference Gu, Ieromonachou, Zhou and Tseng2018).

Identifying and repurposing viable batteries → reduction of e-waste

As part of filtering out usable units within EoL systems, sorting and selection processes are important. Reusing discharged batteries in second-life applications helps keep them out of the high volume of e-waste globally (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Liu, Qian and Bao2020a; da Silva et al., Reference da Silva, Lohmer, Rohla and Angelis2023).

Refurbishing avoids new manufacturing → reduced energy use from new battery production

Reconditioning and refurbishing used batteries can dramatically lower the energy intensity often associated with the production of new ones. Research demonstrates that battery manufacturing is one of the most energy-hungry processes in EV production chains (Notter et al., Reference Notter, Gauch, Widmer, Wager, Stamp, Zah and Althaus2010; Zhao and Baker, Reference Zhao and Baker2022).

Reconfigured modules in stationary systems → support for renewable energy storage

Reconfigured battery modules for stationary storage allow for integration into renewable energy systems, such as solar microgrids. This facilitates load balancing and backup storage in distributed generation systems (Onat et al., Reference Onat, Aboushaqrah and Kucukvar2019; Omrani and Jannesari, Reference Omrani and Jannesari2019).

Reusing batteries in stationary systems → lower material demand for new batteries

Using previously used batteries in less-demanding situations – such as in commercial and residential buildings – has an effect in reducing the original imaginary material consumption of virgin raw materials such as lithium and cobalt (Olivetti et al., Reference Olivetti, Ceder, Gaustad and Fu2017; Sarkar et al., Reference Sarkar, Sarkar and Bharadwaj2018). This accommodates a circular economy by encouraging less reliance on mining.

Storing renewable energy in microgrids → CO₂ emissions reduction

The second-life application of EV battery can also accompany renewable energy storage in microgrids to help reduce reliance on fossil fuels for backup power. This increased application helps keep batteries in use for longer periods while also reducing CO₂ emissions by promoting cleaner energy systems (Onat et al., Reference Onat, Aboushaqrah and Kucukvar2019; Zhao and Baker, Reference Zhao and Baker2022).

Extending battery life through second use → conservation of critical raw materials

Second-use applications prolong battery life, potentially reducing the frequency and intensity of raw material extraction. This is significant in light of risks associated with geopolitical and supply factors related to metals, such as cobalt, nickel and lithium (Gemechu et al., Reference Gemechu, Sonnemann and Young2017; Olivetti et al., Reference Olivetti, Ceder, Gaustad and Fu2017).

Challenges and opportunities in greening the battery SC

With the adoption of EVs increasing, greening the battery SC has become more pressing. Advances have occurred along technological fronts, policies and partnerships and business initiatives. However, challenges persist related to collection and recycling systems, second-life uses, digital traceability and policy and regulatory frameworks.

Solid-state and sodium-ion batteries are emerging as promising lower-impact alternatives that reduce dependence on cobalt and nickel while improving safety and long-term performance (Zhao and Baker, Reference Zhao and Baker2022).

Battery recycling technical approaches have advanced in the areas of hydrometallurgy, pyrometallurgy and direct recycling. The best recovery rate and the lowest energy intensity (Beaudet et al., Reference Beaudet, Larouche, Amouzegar, Bouchard and Zaghib2020) are associated with hydrometallurgy; yet scaling up remains the bottleneck in some provinces, especially in regions without formal, provincial recycling systems (Iloeje et al., Reference Iloeje, Xavier, Graziano, Atkins, Sun, Cresko and Supekar2022). The lack of standardized commodity collection systems and limited economic incentive structures continued to limit widespread deployment.

Second-life applications in grid storage or backup systems are becoming more and more common in examples of projects such as Tesla’s Megapacks and the repurposing of Nissan LEAF in Europe, which are showing the environmental and economic benefits of reuse. However, some of the problems are still present: the condition of health can vary, the SoH data are inconsistent and a protocol for how to determine if the battery is suitable for second-life use is not standardized (Casals et al., Reference Casals, García, Aguesse and Iturrondobeitia2017; Ioakimidis et al., Reference Ioakimidis, Murillo-Marrodán, Bagheri, Thomas and Genikomsakis2019). These issues lead to inaccurate LCAs and limit safe deployment (Hendrickson et al., Reference Hendrickson, Kavvada, Shah, Sathre and Scown2015; Gu et al., Reference Gu, Ieromonachou, Zhou and Tseng2018). In addition, liability, safety and regulation issues limit the rate of second-life use (Manzetti and Mariasiu, Reference Manzetti and Mariasiu2015; Temporelli et al., Reference Temporelli, Carvalho and Girardi2020).

Digital tracking technologies are developing to facilitate reuse and transparency. An example are battery passports. Battery passports leverage either blockchain technologies and the Internet of Things (IoT) or other technologies, such as the EU Battery Passport Initiative. They aim to provide traceability of life cycle data, ensure compliance and help in second-life decision-making (Bedi et al., Reference Bedi, Bhavana, Ramprabhakar, Anand, Meena and Didi2024; Tavana et al., Reference Tavana, Sohrabi, Rezaei, Sorooshian and Mina2024). Currently, these technologies have the potential to enable real-time tracking of battery deterioration as well as to harmonize regulations across jurisdictions. However, they will face serious challenges, including cybersecurity risks, data privacy risks and a lack of standardized interoperability requirements.

In the policy world, countries like those in the EU have put in place design-for-recycling policy with targets for material recovery, like within the EU Battery Regulation (2023), and increasingly, other sustainable mandates, like those in the EU, obligate others in the world to follow. However, the situation remains dire for many developing countries with less infrastructure, governance and equitable access to circular economy (Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Wang and Negnevitsky2022; Niri et al., Reference Niri, Poelzer, Zhang, Rosenkranz, Pettersson and Ghorbani2024).

The EU Battery Regulation (2023) can serve as a scalable blueprint for emerging economies, with traceability requirements and Extended Producer Responsibility policies adapted to regional infrastructure readiness and institutional capacity.

Regulatory differences among global markets contribute to the movement of recycling and disposal burdens across borders, a phenomenon commonly referred to as “environmental dumping.” Low-regulation countries become de facto destinations for hazardous waste streams and degraded secondary materials from battery-saturated economies because of less rigorous enforcement of regulations and inadequate infrastructure to enable circularity. This disparity presents a legitimate threat to equitable global objectives and adds significant governance complexities in seeking transparent and responsible EV battery SCs.

To aid future research and implementations, assessments need to focus on using both real-time high-quality environmental data and creating multi-criteria sustainability indicators that meet the principles of the circular economy (Afroozi et al., Reference Afroozi, Gramifar, Hazratifar, Keshvari and Razavian2025). Aspects that need to be included are modular battery design, reverse logistics with respect to second life deployment (Casals et al., Reference Casals, García, Aguesse and Iturrondobeitia2017; Gupta, Reference Gupta2023) and the mitigation of data gaps in low- and middle-income areas. Furthermore, future research can also examine decentralized production paths that could help with reducing transport emissions and stress-testing potential weaknesses in the face of geopolitical and logistical dilemmas (Bruni et al., Reference Bruni, Capocasale, Costantino, Musso and Perboli2023). A partnership between industry, academia and governments is necessary for standardization and scalability, with transparency, to enable a low-impact, circular EV battery SC.

Conclusion

This assessment has synthesized current literature on the environmental assessment of EV battery SCs, as well as identified major impacts, knowledge deficits and trade-offs between different life cycle stages. The extraction, processing and manufacturing stages remain highly impactful due to the energy required and chemicals used to manufacture batteries, whereas the use and EoL stages are highly dependent on regional electricity mixes and nascent recovery systems – particularly in the Global South. A major finding of this study is that there is methodological inconsistency between studies in terms of system boundaries, functional units and data quality. The inconsistency highlights the need for more standard geospatially representative datasets and improved reporting.

To move toward a sustainable future, stakeholders must act in concert by coordinating across academia, industry and policy. From the perspective of academia, research should focus on the development of regionally specific, high-resolution, local LCA datasets, especially in low- and middle-income countries where environmental impacts have been inadequately examined. Simulation-based models, such as system dynamics, may help identify the feedback loops that facilitate closed-loop SCs and identify long-term environmental trade-offs (Alamerew and Brissaud, Reference Alamerew and Brissaud2020; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wang and Yang2020). From an industry perspective, companies must champion modular/exitable, recyclable battery chemistries leading to optimal reuse, repair and recovery of materials. Second-life strategies will require new reverse logistics networks, SoH monitoring protocols and the compatibility of mixed chemistries. These initiatives will lessen the impact on virgin materials demand and lessen the environmental impacts involved in new battery manufacture, especially when involved in closed-loop recycling processes based on clean energy (Sato and Nakata, Reference Sato and Nakata2019).

Policies must prioritize the enforcement of battery passports and ESG reporting standards; collaborative regulations that reinforce circularity laws must also be endorsed, such as the EU Battery Regulation (2023). Technical innovation in digital traceability (e.g., with blockchain and IoT) could provide the foundation for life cycle tracking, transparency and regulatory compliance, but must also be made robust to address cybersecurity, tamper-proof and be built on compatible standards.

Beyond immediate concerns are issues that require scaling nationally and globally by 2030 – the need for expanded deployment of second-life applications for systems for stationary storage, global reverse logistics infrastructure and full integration of digital tracking technologies throughout SCs. These are transformative processes that must coalesce to make batteries, and their associated life cycles, greener, stronger and resilient. This review has reiterated the difficulty with managing choices with trade-offs inherent in battery design and SC systems. The trade-offs between energy density and recyclability, and between high-performance and environmental safety, reaffirm the assertion that honorable sustainable decision-making is provided when stakeholders engage holistically and collectively, drawing upon full life cycle input.

In the immediate term, advancement hinges on harmonization of reported environmental data across regions, enhanced product carbon footprint tracking systems and filling crucial data gaps in underrepresented areas. In the long term, the reality of a sustainable and fair EV battery value chain will depend upon synchronized scaling of formal recycling and second-life practices, increased regulatory harmonization of global markets and stronger multilateral cooperation to discourage disproportionate environmental burdens and the externalization of waste to at-risk areas.

Recommendations for future studies

It is important to consider predictive modeling methods that will capture the changing dynamics of the global EV fleets, such as battery chemistries and efficiency of collection on a regional level (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Rysiecki, Gong and Shi2020b). Reverse logistics frameworks require adjustments to handle the flows of second-life batteries more effectively (Casals et al., Reference Casals, García, Aguesse and Iturrondobeitia2017; Gupta, Reference Gupta2023), and researchers must further investigate their role in the context of distributed energy systems, including rural or off-grid applications (Simons et al., Reference Simons, Singh, Hunt and Ermilio2022).

Future studies should focus on improving environmental impact assessments at all points of the battery SC, as well as improving LCA methods with good quality smart data and high resolution (especially for mining, processing and battery production, where emissions and resource use are highest). In addition, researchers should consider the environmental trade-offs for different battery chemistries, looking for scalable alternatives with smaller ecological footprints.

There should be a goal to refine SC design to reduce transportation emissions released into the atmosphere. Possible study options could include regionalizing production, or incorporating regenerative energy sources into manufacturing. Industrial symbiosis approaches – for example, utilizing byproducts or common infrastructure across facilities – can create emission reductions and increase efficiency through SCs (Mathur et al., Reference Mathur, Deng, Singh, Yih and Sutherland2019; Bedi et al., Reference Bedi, Bhavana, Ramprabhakar, Anand, Meena and Didi2024; Short et al., Reference Short, Rehman, Cui, Al-Greer, Savage, Emandi and Burn2024).

Improving EoL processes by employing more efficient and less chemical-intensive recycling technologies will be critical for reducing negative upstream environmental impacts. The application of advanced traceability tools (blockchain and/or IoT platforms) will help with real-time tracking of emissions and resource flows, thereby increasing transparency and accountability over time. Ultimately, it will be critical to facilitate action from national, local, manufacturers and university partnerships to produce a circular, low-impact battery value chain that aligns with immediate and long-term environmental challenges (Ren et al., year; Soufi et al., Reference Soufi, Mesbahi and Samet2023, Kaur et al., Reference Kaur, Manna and Singh2025; Gupta, Reference Gupta2023). Decentralized production systems that distribute production capacity regionally will have the chance to cut emissions and also increase SC resilience, especially to respond to transportation bottlenecks and geopolitical instability (Bruni et al., Reference Bruni, Capocasale, Costantino, Musso and Perboli2023).

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/etr.2025.10008.

Data availability statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article as all data are derived from publicly available peer-reviewed literature.

Author contribution

A.S.A.-A. conducted the systematic literature review, data analysis and manuscript drafting. G.K. and S.K. provided supervision, conceptual guidance and critical revisions of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version.

Financial support

This research was supported by Mitacs Canada through the Accelerate program and by the Faculty of Engineering and Applied Science at the University of Regina.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Ethics statement

Not applicable, as this study does not involve human participants or animal subjects.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work, the author(s) used ChatGPT to improve the writing quality. After using this tool/service, the author(s) reviewed and edited the content as needed and take(s) full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Comments

July 16, 2025

Dear

Editors

Cambridge Prisms: Energy Transitions

Sir

Enclosed is the paper, entitled “From Mine to Motor: A Literature Review on Environmental Assessments of Electric Vehicle Battery Supply Chains”. Please accept it as a candidate for the Cambridge Prisms: Energy Transitions.

This review article provides a comprehensive review of 84 peer-reviewed papers for the years 2008 through to 2025, of which 78% were published from 2020 to 2025, indicating the rapidly developing field. Following the PRISMA method, the review has identified significant environmental hotspot and trade-off issues across six phases of the battery supply chain, as well as inconsistencies regarding methodology, such as functional units of measurement, and missing data in relation to the Global South. New contributions include a comparison of the life cycle assessment (LCA) approaches, using new data from 2023-2025, and the inclusion of a global context beyond the Western ones that have typically dominated empirical research.

This review highlights ignored areas such as informal recycling of batteries, unfair regulations across borders, and it provides recommendations, which are relevant to policymakers, industry and academia, to improve transparency in supply chain, better compliance with environmental, social and governance (ESG) requirements, and sustainability initiatives.

Finally, this paper is an original unpublished work of ours and it has not been submitted to any other journal for reviews and the contents of this manuscript have not been copyrighted or published previously and are not now under consideration for publication elsewhere. The contents of this manuscript will not be copyrighted, submitted, or published elsewhere, while acceptance by the Cambridge Prisms: Energy Transitions is under consideration.

Regards,

Golam Kabir, Ph.D., P.Eng.

Professor and Program Chair

Sustainable and Resilient System Analytics (SRSA) Group

Industrial Systems Engineering, Faculty of Engineering and Applied Science

University of Regina

ED 432, 3737 Wascana Pkwy, Regina, SK, Canada, S4S 0A2

E-mail: golam.kabir@uregina.ca; golamkabirraju@gmail.com;

Phone: 1-306-585-5271; 1-250-862-0733

http://uregina.ca/~gkj627/